Abstract

Green H2 generation through layered materials plays a significant role among a wide variety of materials owing to their high theoretical surface area and distinctive features in (photo)catalysis. Layered titanates (LTs) are a class of these materials, but they suffer from large bandgaps and a layers’ stacked form. We first address the successful exfoliation of bulk LT to exfoliated few-layer sheets via long-term dilute HCl treatment at room temperature without any organic exfoliating agents. Then, we demonstrate a substantial photocatalytic activity enhancement through the loading of Sn single atoms on exfoliated LTs (K0.8Ti1.73Li0.27O4). Comprehensive analysis, including time-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy, revealed the modification of electronic and physical properties of the exfoliated layered titanate for better solar photocatalysis. Upon treating the exfoliated titanate in SnCl2 solution, a Sn single atom was successfully loaded on the exfoliated titanate, which was characterized by spectroscopic and microscopic techniques, including aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy. The exfoliated titanate with an optimal Sn loading exhibited a good photocatalytic H2 evolution from water containing methanol and from ammonia borane (AB) dehydrogenation, which was not only enhanced from the pristine LT, but higher than conventional TiO2-based photocatalysts like Au-loaded P25.

Keywords: Layered titanates, Hydrogen generation, Single atom Sn, Photocatalysis, Ammonia borane

Short abstract

Loading single atom Sn on protonated layered titanate revealing an enhanced photocatalytic green H2 generation through water splitting and ammonia borane dehydrogenation.

Introduction

Replacing fossil fuels with green hydrogen (H2) has been accelerated in the current decade as one of the indispensable decarbonizing alternatives to mitigate CO2 emissions and harness climate change and its further consequences.1 After photocatalytic water splitting,2 dehydrogenation of small molecules by photocatalysis has become one of the key approaches for green sustainable H2 production.3,4 The borane compounds (as a high-content H2 reservoir)5−8 are unique candidates for H2 generation through a proper (photo)catalyst. Among the (photo)catalysts, layered materials are front liners in the catalysis toward H2 production8,9 due to their large theoretical surface area10 and their game-changing chemistry (e.g., functional groups) and physics (e.g., electron–phonon interactions),11 originating from their anisotropic structures.12,13 However, layered materials are usually in 3D bulk structures and need to be exfoliated since in the pristine bulk form, the layers are stacked through weak interactions, and the interlayers are inactive.12

Layered titanates (LTs) are of the most widely investigated layered materials as photocatalysts,14−18 but scarcely show promising photocatalytic activity in H2 generation applications under solar light irradiation due to their intrinsically large bandgaps in addition to the blockade of interlayers for any mass diffusion.16,19 Therefore, exfoliating the bulk crystal structure of LTs is found an applicable method to release the surface of the layers and further modifying with methods such as heterostructuring20−23 or doping17 and single atom loading with a photoactive species to narrow the bandgap is inevitable for photocatalytic applications.

LTs consisting of TiO6-interconnected layers can be found in different chemical compositions in which there is a strong electrostatic interaction among the layers. These LTs usually accompany an alkali metal counterion and, consequently, distinctly differ in their features and activities,18 but their large bandgaps are a feature in common.15,17 However, exchanging these alkali metals with other species can generate a significant change in the physicochemical activity of LTs.24−28 Therefore, the investigations of the photocatalytic activities of cation-exchanged LTs may bring serendipity features that require to be undertaken.

The pioneering works around the exfoliation of LTs were first established by Sasaki et al. with organic ammoniums, where they reported the osmotic swelling and subsequent exfoliation.29 Since then, some efforts have been made to modify the exfoliating method, including those without organic exfoliating agents. However, the structural conversion of LTs into a more stable phase (e.g., rutile or anatase) under mild or strict conditions has been reported.30,31 Thus, the major challenge of LTs is their (simultaneous) exfoliation without crystal phase change and without using an organic agent.32 Also, in a few successful cases, LTs have been exfoliated by some organic species such as alkylammonium salts; the intercalation of such species in the interlayers of LTs33 causes exfoliation or a partial phase conversion32 and, thus, makes the LTs impure or costly.17,32,33 For this reason, the optical features, precisely the photocatalytic properties, of the exfoliated pure LTs are still underexplored.

Nowadays, loading a single atom on semiconductors plays an important role in improving photocatalytic activity.34,35 However, in the case of the LTs, single-atom loading can barely be found. One of the critical challenges in single-atom catalysis is to stabilize the chemical state of the single atom on a semiconductor through the adjacent heteroatoms. Moreover, the single-atom oxidation state alteration is another challenge that is drastically impacted by the crystal structure and chemical composition of the surface of the semiconductor.36−38

Herein, we investigate the exfoliation of LT in dilute HCl water without any organic species and the roles of Sn2+ loading on the exfoliated LT nanostructures (exf-HTO) in photocatalytic ammonia borane (AB) dehydrogenation and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) from water at room temperature. We demonstrate the single atom Sn-loaded exf-HTO (Sn/exf-HTO), in an optimal ratio, shows considerably high photocatalytic activity than conventional TiO2 photocatalysts, including P25 and Au nanoparticle-loaded P25.

Experimental Section

Materials and Characterizations

All reagents and solvents were purchased commercially and used without further purification. TiO2 (P25; 97%), SnCl2·2H2O (99.8%), K2CO3 (>99.0%), Li2CO3 (>99.0%), HCl (>37%), gold(III) chloride trihydrate (>49%), C2H5OH, and NH3BH3 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Ultrapure water (≥18.2 MΩ·cm) was used throughout the experiments. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected by using a powder X-ray diffractometer (Bruker D2 Phaser X-ray Diffractometer) with Cu Kα radiation with a 10 kV beam voltage and a 30 mA current. UV–visible spectroscopy measurements were performed using a Shimadzu UV-3600 UV–vis-NIR spectrophotometer with the reflection mode. It was converted to the absorption spectra by Kubelka–Munk transformation. Raman spectroscopy measurements were done by using Renishaw inVia Raman Microscope with the 633 nm excitation laser source. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were conducted using a Thermo K-alpha spectrometer system with Al Kα radiation (hυ = 1486.7 eV) as the excitation source. Binding energies for the XPS spectra were corrected by setting C 1s binding energy to 284.5 eV. Photoluminescence (PL) emission and lifetime measurements were performed using an Edinburgh Instruments FLS1000 spectrometer. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were recorded by a Zeiss Ultra Plus microscope with an accelerating potential of 20 kV. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained by a 200 kV aberration-corrected TEM/STEM Hitachi HF5000 equipment. Photocatalytic activity measurements were performed using an LCS-100 solar simulator with 1.0 SUN AM 1.5G output from a 100 W xenon lamp. The quantification of H2 was done by a gas chromatograph (7820A, GC-System, Agilent) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and flame ionization detector (FID).

Synthesis of KTLO

Layered potassium lithium titanate (K0.8Ti1.73Li0.27O4 named KTLO) was prepared by solid-state reaction method using TiO2, K2CO3, and Li2CO3 with the molar ratio of (4.1:6.0:0.7).39 The starting chemicals and three drops of C2H5OH were ground in an agate mortar with a pestle for 2 h, and the powder mixture was calcined in a muffle furnace at 600 °C for 20 h. After the first calcination, the mixture was cooled to room temperature. The sample was mixed for another 2 h and placed in the muffle furnace for the second calcination at 600 °C for 20 h.

Protonation and Exfoliation of KTLO

The obtained KTLO (0.5 g) from the previous step was dispersed in 0.1 M HCl solution (100 mL) and stirred at room temperature. For the protonated layered titanate (HTO), the solution was stirred for 1 day at 600 rpm and separated by centrifuge, washed three times with C2H5OH (30 mL), and dried at room temperature. For the exf-HTO, the dispersion was stirred at a lower speed (400 rpm) for 3 days, and then, the supernatant was separated by centrifugation, and a fresh solution of 0.1 M HCl (100 mL) was added to the centrifuged powder and restirred under the same conditions at room temperature for 11 days. Afterward, the dispersion was centrifuged and dried in a freeze-dryer for 24 h.

Preparation of Sn/exf-HTO

Adsorption of Sn on exf-HTO was done by adding 10 mg of exf-HTO to the different concentrations (5, 10, 15, 20, 40, 50, 60 ppm) of 20 mL SnCl2.2H2O solution in a test tube and mixing the solution in the dark for 3 h and then under the illumination of a solar simulator for 1 h. As the exfoliated layers have a negative charge (compensated with H+), cationic species can bind the layers via the electrostatic self-assembly process. The mixture was centrifuged and dried in a vacuum oven for 24 h. After the photocatalytic performance tests were done, Sn/exf-HTO was recycled via centrifugation and drying in the vacuum oven for 24 h as the resulting Sn/exf-HTO-rec sample.

Photocatalytic Activity Tests

For performing the photocatalytic H2 production reaction from ammonia borane (NH3BH3), powder samples of KTLO, HTO, exf-HTO, and Sn/exf-HTO were dispersed in 4.5 mL of distilled water in a Pyrex test tube purged with N2 for 30 min. Before sealing with a rubber septum properly, 0.5 mL of 40 mM NH3BH3 was added. For the H2 evolution reaction from water, powder samples (5 mg) were dispersed separately in 5 mL of distilled water (20%V/V methanol) in a Pyrex test tube which was sealed properly and purged with N2 for 30 min. The test tube was illuminated via the solar simulator while stirring constantly. The amount of H2 produced was measured with the gas chromatograph, directly taking injections from the headspace of the Pyrex tube using a gastight syringe.

Results and Discussion

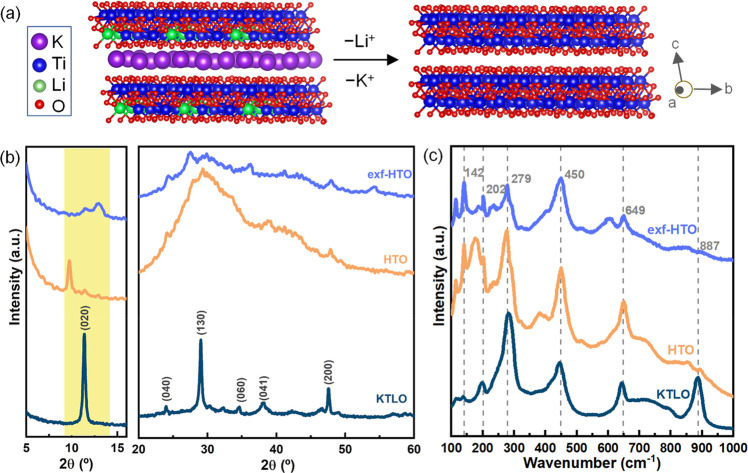

Usually, the protonation, cation exchange, and exfoliation of LTs are three crucial types of postmodifications that can be found around developing LTs for various applications. Here, we present a new facile method for the exfoliation of LTs along protonation through long-term slow agitation of LT in a dilute HCl solution into a few-layered HTO. A step further, we succeeded in loading a single atom Sn and, subsequently, a schematic procedure for the preparation of the single atom Sn-loaded exf-HTO is presented in Scheme 1 and Figure 1a.

Scheme 1. Schematics of Single Atom Sn Loading and Exfoliating KTLO into HTO.

Figure 1.

Crystal structures of KTLO and HTO from the edge view (020) plane. (a) XRD patterns (b) and Raman spectra (c) of KTLO, HTO, and exf-HTO.

We confirmed the successful synthesis of layered titanate KTLO through the XRD pattern and used it for further protonation (HTO) and exfoliation (exf-HTO). In the case of KTLO, a peak at 11.4° corresponds to the (020) plane with a d value of ∼0.8 nm, representing the interlayer space and the layer thickness (Figure 1b). A peak at 2θ = 29.1° also corresponds to the layered structure of the material, showing the (130) plane. Another characteristic peak at 47.4° corresponds to the crystalline lepidocrocite structure of layered titanate, showing the (200) plane. Once protonated, the first peak at a lower degree slightly shifts to a smaller angle (9.7° corresponds to a d value of ∼0.9 nm), showing that the interlayer space has been expanded, i.e., by intercalating water after exchanging the K+ and Li+ with H+, so that the d value undergoes a 0.1 nm expansion with respect to KTLO (Figure 1b). As confirmed before,28 the protonated LT usually exhibits broader peaks compared to the pristine KTLO. Once the exfoliation is performed, the first characteristic peak of the layered structure has slightly shifted to higher angles, with a significant decrease in the intensity compared to those for HTO and KTLO and has become broader, showing that the layers are remarkably exfoliated (Figure 1b). The peak at 29.1° after the treatment is also broadened, showing that the protonation and further exfoliation make the layers’ assembly disorder (exfoliated) with less long-range order to be detectable by XRD as a sharp peak (this justification will be proved by TEM observation in the later section). Moreover, the same peak at 29.1° has less intensity in exf-HTO than HTO, further confirming the exfoliation. A similar XRD reflection is also reported for an LT, which is exfoliated by a bulky organic amine.40

Raman spectra of the samples are shown in Figure 1c. Accordingly, the peak at 887 cm–1 indicates the distorted TiO6 with a short Ti–O bond,41 which may be more affected by the presence of K+/Li+, where after replacing it with H+, the relevant peak almost disappears. The peaks at 279, 450, and 649 cm–1 are assigned to Ti–O–Ti stretching modes of TiO6 octahedra units.40 In conclusion, by comparing the Raman spectra of KTLO with the HTO and exf-HTO, the only change that can be observed is related to the interlayer surface chemistry, emerging as a peak at 887 cm–1, while the main backbone has a similar structure.

UV–vis spectra and Tauc plots, which are used to determine light absorption properties and the bandgap of the photocatalysts, are presented in Figure 2a and b, respectively. While KTLO and HTO absorbed light with a wavelength shorter than 350 nm, the absorption property of exf-HTO reaches 400 nm. Tauc plots clearly demonstrated a change of the bandgap upon protonation and exfoliation, 3.19 eV was estimated to be the bandgap of exf-HTO while larger values, 3.52 and 3.79 eV were found for HTO and KTLO, respectively. A simple exfoliation method caused this remarkable change in the bandgap values and made this LT more sensitive to the light in the visible spectrum. The increased light absorption of the exf-HTO could be attributed to the introduction of new energy levels in the bandgap. Defects such as oxygen vacancies, titanium vacancies, and interstitials could be introduced on the surface or in the bulk during exfoliation, which could generate energy levels inside the bandgap.24

Figure 2.

UV–vis spectra recorded in a diffuse reflectance mode (a), Tauc plot from UV–vis spectra using Kubelka–Munk conversion (b), emission spectra (c), and time-resolved PL decay profile (d) of KTLO, HTO, and exf-HTO.

Exfoliation had a significant impact on the utilization of the charge carriers and their lifetime. It is seen in Figure 2c that pure KTLO and HTO exhibit a broad peak in the region of 330–400 nm, having a maxima at around 360 nm. The band edge emission and defect emission are two decay channels commonly suggested to describe the origin of the PL emission signals. Oxygen vacancy-mediated states resulting from the synthesis, protonation, and exfoliation could trap charge carriers and affect the emission profile. The PL spectra of exf-HTO show a red-shift of the peak maximum compared to that of KTLO and HTO, which can be attributed to the altered band structure, in agreement with its UV–vis absorption characteristics. Figure 2d demonstrates the fluorescence emission decays at a specific wavelength where the peak maximum is investigated to determine the lifetime of the charge carriers in samples. The recombination appears to be the slowest for the exf-HTO. The lifetimes were calculated by the deconvolution of the decay curves, and the values obtained for KTLO, HTO, and exf-HTO are 1.08, 0.94, and 1.57 ns, respectively. The increased lifetime of the charge carriers in the exf-HTOs reveals that the exfoliation-induced modifications are playing a critical role.

We demonstrated the morphology and crystal structure and thickness of the exfoliated layered titanate through several microscopic techniques, including SEM, TEM, and AFM. The observed morphologies in SEM and TEM (Figure 3a,e) images match with each other and indicate a uniform nanostructure shaping from a randomly oriented morphology of KTLO (Figure 3a). Furthermore, by measuring the thickness of the representative exf-HTO particle, ∼8 nm, which can include the stacked from ∼11 layers of LT, where the lateral size shows ∼90 nm (Figure 3h). The observed lateral size in AFM is also a close value to the obtained average lateral size value from the SEM image of exf-HTO (∼75 nm, Figure 3g, see the inset). The thickness of exf-HTO compared to the normally protonated HTO (up to 35 nm, judging from the SEM image in Figure 3b) shows that our method significantly exfoliates the titanate layers along with protonation. The HR-TEM and (HR)-HAADF-STEM images of the exf-HTO show a single crystalline structure from the lateral dimension of the layer where the obtained d value from the observed facet is 0.715 nm, assignable to the (200) plane (Figure 3i–l). The edge view of exf-HTO also indicates a d value of 0.72 nm, which can be assigned to the obtained XRD peak at 12.3°, Figure 1b. Note that, due to the low long-range order of the exfoliated layers, the crystalline structure of the titanate layers can only be observed through the HR-HAADF-STEM and HR-TEM-captured images, where the XRD pattern is seldomly revealing this crystallinity due to the limited long-range order of the layers (Figure 1b). We also captured an HRTEM image from the edge view of the exf-HTO showing the stacking of 17 layers where the layers are free of K+ (Figure 3l), in comparison with a KTLO group (Figure S1); see the presence of K+ in the HR-TEM image that is captured in the edges view of the layers.

Figure 3.

SEM images of KTLO (a), HTO (b), exf-HTO (c, d), and TEM images of KTLO (e), HTO (f), exf-HTO with a lateral width size distribution (g), AFM image of exf-HTO with a height profile (h), HR-TEM with low and high magnification (i, j), HR-HAADF-STEM with a lateral view and (200) planes according to the d value (0.193 nm) (k), and cross-sectional HRTEM of exf-HTO showing layer edges and 0.715 nm thickness (l).

XPS was used to investigate the surface composition and chemical state of photocatalysts. Ti 2p XPS spectra presented in Figure 4a exhibit peaks observed around 457 to 464 eV binding energies for Ti 2p3/2 and Ti 2p1/2, respectively. The Ti 2p3/2 peak shifted to higher binding energies from 457.9 eV (KTLO) to 458.8 eV (exf-HTO) as well as Ti 2p1/2 peak shifted from 463.7 eV (KTLO) to 464.5 eV (exf-HTO). HCl treatment results in K+ and Li+ ions at the interlayers of KTLO exchanged with H+. When protonation and, eventually, exfoliation occur, the bond distance between Ti and O gets shorter with the H+ ions presence since the electrostatic interplay between O and K+/Li+ ions is much stronger than that between O and H+ ions.14 The absence of the peaks in the high binding energy side of the spectra indicates that protonation and exfoliation treatments did not lead to the reduction of Ti. Similar shifts to high binding energies from KTLO to exf-HTO were also observed in O 1s spectra, as demonstrated in Figure 4b. O 1s spectra were deconvoluted into three peaks. The main component represents oxide ions (Ti–O–Ti), high binding energy shoulder within ∼531.1–532 eV, on the other hand, are assigned to hydroxyl groups (−OH) coordinated to the surfaces of the layers. Exfoliation treatment increases the number of −OH groups since more surface layers are susceptible to hydroxylation, and water adsorption is created (the component at the highest binding energy).

Figure 4.

Ti 2p (a), O 1s (b), and VB (c) XPS spectra of KTLO, HTO, and exf-HTO, respectively. The alignment of the band edges based on VB edges determined by XPS and bandgap energies estimated by Tauc analysis (d).

Valence band (VB) XPS spectra presented in Figure 4c could provide energy positions of the occupied energy levels. A close inspection of the band edge position reveals that the VB maximum moves down in energy upon exfoliation. This binding energy change matches with the energy shifts observed in core levels. A combination of bandgap energies estimated by Tauc analysis and VB maxima obtained in Figure 4c could be used to construct relative changes in the energy positions of KTLO, HTO, and exf-HTO. As summarized in Figure 4d, the gradual drop in the VB energy position and smaller bandgap energy significantly lowers the conduction band (CB) position.

We further explored the morphology of the exfoliated layered titanates after Sn loading and confirmed that the Sn loading process has no destructive effect on the nanostructure of the exf-HTO (see Figure 5a–c). The HR-STEM represents some light dots on the crystalline fringes of the LT, showing that the Sn species are in single-atom form and distributed on the surface. TEM-elemental mapping further confirms the thorough distribution of Sn uniformly along Ti and O on each particle (Figure 5e–g) without forming any Sn nanoparticles.

Figure 5.

SEM image (a), TEM images (b, c), electron image (d), elemental mapping of O Kα1 (e), Sn Lα1 (f), and Ti Kα1 (g) of Sn/exf-HTO.

Despite Sn single atoms being well distributed on the surface of LTs, the loading process has significantly changed the XRD pattern (Figure 6a). A broad background feature located around 30° similar to the one observed for HTO reappeared, and all the diffraction features remained buried under this background. No significant change in Raman spectral features has been observed (Figure 6b). This structural change could indicate that the long-range order has been lost upon Sn loading; however, the local structure and the coordination of the atoms remain intact. Sn single atoms not affecting vibrational features could be explained by their low loading. The reverse effect of the Sn loading is also evident in optical spectra. UV–vis spectra and respective Tauc analysis reveal band reopening, and bandgap energies shift from 3.19 to 3.41 eV (Figure 6c). Interestingly, steady-state PL intensity decreases within 400–600 nm (Figure 6d), suggesting that the recombination emission process has lost its dominance. Generally, the crystallinity and defects densities play a vital role in carrier extraction; however, the possible influence of the Sn loaded on the surface must undoubtedly be considered. Reduced PL intensity suggests that single-atom Sn layers could achieve better carrier extraction. Time-resolved PL decay measurements performed (Figure 6d) help us better understand the carrier decay behavior.42 Further decreased PL decay lifetimes from 1.57 to 0.97 ns point out that the efficiency of the charge carrier extraction could be increased by a single atom Sn layer.

Figure 6.

XRD pattern (a), Raman spectra (b), UV–vis spectra and Tauc plots (c), steady-state PL emission and time-resolved PL decay profile (d), Ti 2p-O 1s (e), Sn 3d (f), and VB (g) XPS spectra of exf-HTO and Sn/exf-HTO. The change in the alignment of the band edges is shown in (h).

Ti 2p and O 1s XPS main peak positions shifted to lower binding energies after Sn loading (Figure 6e). This binding energy shift seems to be related to the partial restacking of the layers as in the HTO structure. Sn single atoms remain on the surfaces of the layers. O 1s spectral deconvolution indicates that the peak previously assigned to H2O hydrogen bonded to surface OH groups have a lower intensity due to lowered exposed surface layers. Sn 3d XPS spectrum (Figure 6f) contains 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 spin–orbit components located at 486.4 and 494.8 eV, respectively, suggesting that Sn exists with the 2+ state on the surface.43 Comparing the Sn 3d XPS spectra of Sn4+-loaded exf-HTO with the one prepared here from Sn2+ (see Figure S2) further proves that the oxidation state of Sn in Sn/exf-HTO is remained +2. Sn with metallic character is not expected, no Sn (nano)particles were found under TEM observation, and BE of metallic Sn is not overlapping with the BE of the existing loaded Sn in Sn/exf-HTO.44 Sn loading leads to a small shift in VB maxima (Figure 6g), which re-establishes the VB and CB edge positions (Figure 6f).

Photocatalytic Tests

Here, we tested the photocatalytic activity of the Sn-loaded protonated exfoliated HTO (Sn/exf-HTO) on the HER from water under solar light illumination. We also added MeOH (20 V/V%) to water for scavenging the photogenerated holes. First, the concentration of the treating solution of Sn for loading on exf-HTO was investigated. Accordingly, we treated the exf-HTO with different concentrations of Sn and found out that when the Sn solution is 20 ppm, the photocatalytic activity is in optimal activity compared to other selected concentrations, including 10, 40, and 50 ppm. The Sn-loaded exf-HTO obtained by treating it with 20 ppm of SnCl2 solution produces ∼3.5 mmol·g–1 H2 in 30 min of the illumination while for the other concentrations, we observed lower values (Figure 7a). Loading lower than 20 ppm of Sn is expected to have lower photocatalytic activities, while for the higher concentrations (e.g., 50 ppm) it was surprising, and we investigated the reason for the decrease in photocatalytic activity by studying its structure and morphology with SEM, TEM, and HAADF-STEM, see Figure S3. According to our observation, the layers aggregate, although the Sn concentration seems higher under HAADF-STEM, which points out that the Sn is still in a single atom form but causes the aggregation of the particles and a blockade of the direct light exposure to the active surface.

Figure 7.

Solar-driven photocatalytic H2 evolution reaction from water containing methanol on Sn/exf-HTO loaded with different concentrations of Sn (a), photocatalytic activity comparison of Sn/exf-HTO (20 ppm) with other corresponding versions of LTs and the commercial TiO2 (P25) and Sn-loaded P25 (b).

We further compared the photocatalytic activity of the other titanates and a TiO2 species with Sn/exf-HTO, in which Sn/exf-HTO has higher photocatalytic activity in H2 evolution (3.56 mmol/g) under identical conditions. For proving that the exfoliation step has a significant impact on the photocatalytic H2 evolution reaction, we compared exf-HTO with its corresponding HTO and found that the exf-HTO produces ∼241 μmol g–1 more H2 than the HTO in 30 min under the identical conditions. As a reference, we also evaluated the photocatalytic activity of KTLO to show that its activity is minor (Figure 7b) compared to the Sn/exf-HTO and the protonated ones. This low activity can be due to the fact that KTLO is still bulk layered material, and its activity is considerably poorer. Furthermore, along with the photocatalytic activity enhancement originating from protonation and exfoliation of the LT, loading Sn single atoms play a significant role in the photocatalytic activity enhancement when we compare the KTLO, HTO, and exf-HTO with Sn/exf-HTO as a trajectory of postmodification (Figure 7b, see the inset). This improvement in the photocatalytic activity after Sn loading can be due to the faster charge carrier separation, as judged by the PL decay profiles comparison of Sn/exf-HTO and exf-HTO, see Figure 6d. To our surprise, the Sn/exf-HTO exhibits even a better solar-driven photocatalytic H2 evolution activity than the commercial TiO2 (P25). The Sn-loaded TiO2 (P25) under the identical preparation conditions (see Figure 7) has a minor impact in the activity. This observation shows that the Sn species loaded on TiO2 is not showing the same mechanism of charge carrier photogeneration that occurs in the exf-HTO. Comparing the photocatalytic activity of Sn/exf-HTO with the previous reports for LTs, also further proves the excellent photocatalytic activity improvement after Sn loading, see Table S1.15,45−47

We further evaluated the photocatalytic activity of the Sn/exf-HTO LT in AB dehydrogenation reaction at room temperature. AB can decompose into various forms, depending on the (photo)catalytic activity.48 However, each mole of AB usually converts to one mole of ammonium borate salt and three moles of H2 as follows:48

| 1 |

We first investigated if Sn has any photocatalytic activity impact on AB dehydrogenation. Accordingly, when the reaction is carried out in the dark, the H2 generation is minimal, while in the presence of solar light, the AB dehydrogenation completes within 10 min. We also studied the impact of Sn loading amount on photocatalytic AB dehydrogenation and likewise hydrogen evolution reaction, the 20 ppm of SnCl2-treated exf-HTO exhibited a superior photocatalytic activity compared to selected lower and higher Sn concentrations treated with exf-HTO (Figure 8a). Here, the photocatalytic activity of Sn loading on exf-HTO was compared with the Sn-loaded P25 (a commercial TiO2), unexfoliated HTO, and bare HTO (Figure 8b). In all cases, the single atom Sn/exf-HTO revealed a superior activity than other Sn-loaded and unloaded titanates and TiO2. It is also important to note that the Au/P25 also showed less activity than the Sn-loaded exf-HTO, which can be pointed as an alternative to noble metals that are believed to be promising cocatalysts for TiO2-based materials.49 Moreover, Au as a noble metal cocatalyst, also possesses plasmonic activity that can enhance further but fails to show higher photocatalytic activity than the Sn-loaded exfoliated HTO. We also studied the photocatalytic activity of the Sn/exf-HTO in the dehydrogenation of the AB through illumination of monochromatized light to see the efficiency in the target photocatalytic reaction at various wavelengths. Accordingly, the photocatalytic activity of Sn/exf-HTO in the shorter wavelengths of UV range is significantly higher, a significant decrease in the photocatalytic activity occurs as it approaches to the visible range. This observation is matching well with the UV–vis absorption spectra, see Figure S4.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Sn/exf-HTO photocatalytic activity in AB dehydrogenation reaction under illumination and dark conditions through different Sn loading amounts (a). Comparing AB dehydrogenation reaction rate of different TiO2-based photocatalysts with exf-HTO and Sn/exf-HTO (b).

The photocatalytic activity of the recovered sample from AB dehydrogenation also indicates a slight decrease (Figure S5), confirming that the photocatalyst is reusable. Sn 3d XPS spectra of the recovered Sn/exf-HTO (Figure S6) after photocatalytic AB dehydrogenation was investigated to monitor any possible reduction of Sn species since AB can sometimes reduce the metals during the reaction.50 By comparing the Sn 3d XPS spectra of pristine and recovered Sn/exf-HTO, the oxidation state of the Sn had no sensible alteration during the photocatalytic AB dehydrogenation reaction. Furthermore, the XRD pattern and Raman spectral features of the Sn/exf-HTO-rec slightly differed from the Sn/exf-HTO, showing that the HTO structure is also sustainable and stable during the reaction process (Figure S7).

Conclusion

In summary, we successfully exfoliated the layered titanate via a facile additive-free method, which provided an enhanced photocatalytic activity by narrowing the bandgap and prolonging the photogenerated electron/hole lifetime. Sn loaded on exf-HTO was found in single atom form homogeneously distributed on the surface and Sn seemed to be agglomerated when its loading was increased. A significant fraction of the enhancement of the photocatalytic activity toward hydrogen evolution and AB dehydrogenation reactions was due to the Sn single atom decoration on exf-HTOs. The oxidation state of Sn, the morphology, and the lepidocrocite structure of the exf-HTO were found to be sustainable during the photocatalytic reactions. Therefore, the single-atom Sn species can be proposed as an excellent candidate to trigger the photoactivity of the exfoliated layered titanates. At the same time, the other metals can be further explored from the perspective of the exfoliated layered titanates.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the TÜBİTAK and Horizon-2020 Marie Skłodowska Curie for providing financial support in the Co-Funded Brain Circulation Program (Project No. 120C057) framework. The authors thank the Koç University Surface Science and Technology Center (KUYTAM) for the characterization measurements, Koç University n2Star and Hiroaki Matsumoto for the TEM measurements. The authors are also thankful to Prof. Uğur Ünal and Prof. Havva Yağcı Acar for supporting this research by providing resources.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c06181.

Preparation and XPS analysis of Sn4+-loaded exf-HTO, photocatalytic activity tests, and results at specific wavelengths, and XRD patterns, Raman spectra, XPS analysis, SEM, TEM, HAADF-STEM, and photocatalytic activity results for recycled Sn-loaded exf-HTO, the comparison table of photocatalytic activity (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Luderer G.; Madeddu S.; Merfort L.; Ueckerdt F.; Pehl M.; Pietzcker R.; Rottoli M.; Schreyer F.; Bauer N.; Baumstark L.; et al. Impact of declining renewable energy costs on electrification in low-emission scenarios. Nature Energy 2022, 7 (1), 32–42. 10.1038/s41560-021-00937-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima A.; Honda K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238 (5358), 37–38. 10.1038/238037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu F.; Wang C.; Wang Q.; Martinez-Villacorta A. M.; Escobar A.; Chong H.; Wang X.; Moya S.; Salmon L.; Fouquet E.; et al. Highly selective and sharp volcano-type synergistic Ni2Pt@ZIF-8-catalyzed hydrogen evolution from ammonia borane hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (31), 10034–10042. 10.1021/jacs.8b06511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; He J.; Zhao S.; Liu Y.; Zhao Z.; Luo J.; Hu G.; Sun X.; Ding Y. Self-powered H2 production with bifunctional hydrazine as sole consumable. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9 (1), 4365. 10.1038/s41467-018-06815-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y.; Yang L.; Jiang H.; Zhang Y.; Cao D.; Wu C.; Zhang G.; Jiang J.; Song L. Boosted reactivity of ammonia borane dehydrogenation over Ni/Ni2P heterostructure. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10 (5), 1048–1054. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y.; Chen R. Semiempirical hydrogen generation model using concentrated sodium borohydride solution. Energy Fuels 2006, 20 (5), 2149–2154. 10.1021/ef050380f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Liu X. Catalytic hydrolysis of sodium borohydride for hydrogen production using Magnetic recyclable CoFe2O4-modified transition-metal nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4 (10), 11312–11320. 10.1021/acsanm.1c03067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doustkhah E.; Rostamnia S.; Tsunoji N.; Henzie J.; Takei T.; Yamauchi Y.; Ide Y. Templated synthesis of atomically-thin Ag nanocrystal catalysts in the interstitial space of a layered silicate. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54 (35), 4402–4405. 10.1039/C8CC00275D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q.; Qu Y.; Liu D.; Ng K. W.; Pan H. Two-dimensional layered materials: high-efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3 (7), 6270–6296. 10.1021/acsanm.0c01331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ai Y.; Li W.; Zhao D. 2D mesoporous materials. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2022, 9 (5), na. 10.1093/nsr/nwab108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Splendiani A.; Sun L.; Zhang Y.; Li T.; Kim J.; Chim C.-Y.; Galli G.; Wang F. Emerging photoluminescence in monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 2010, 10 (4), 1271–1275. 10.1021/nl903868w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Qian X.; Li J. Phase transitions in 2D materials. Nature Reviews Materials 2021, 6 (9), 829–846. 10.1038/s41578-021-00304-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F.; Lee C.; Hone J.; Shan J.; Heinz T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: A new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105 (13), 136805 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.136805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K.; Inaguma K.; Ogawa M.; Ha P. T.; Akiyama H.; Yamaguchi S.; Minokoshi H.; Ogasawara M.; Kato S. Lepidocrocite-type layered titanate nanoparticles as photocatalysts for H2 production. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5 (7), 9053–9062. 10.1021/acsanm.2c01353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pilarski M.; Marschall R.; Gross S.; Wark M. Layered cesium copper titanate for photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2018, 227, 349–355. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.01.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka M.; Ide Y.; Ogawa M. Temperature-dependent photocatalytic hydrogen evolution activity from water on a dye-sensitized layered titanate. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16 (8), 3520–3522. 10.1039/c3cp55213f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Wang L.; Sun C.; Yan X.; Wang X.; Chen Z.; Smith S. C.; Cheng H.-M.; Lu G. Q. Band-to-band visible-light photon excitation and photoactivity induced by homogeneous nitrogen doping in layered titanates. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21 (7), 1266–1274. 10.1021/cm802986r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo A.; Kondo T. Photoluminescent and photocatalytic properties of layered caesium titanates, Cs2TinO2n+1 (n = 2, 5, 6). J. Mater. Chem. 1997, 7 (5), 777–780. 10.1039/a606297k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ide Y.; Nakasato Y.; Ogawa M. Molecular recognitive photocatalysis driven by the selective adsorption on layered titanates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (10), 3601–3604. 10.1021/ja910591v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. W.; Ha H.-W.; Paek M.-J.; Hyun S.-H.; Baek I.-H.; Choy J.-H.; Hwang S.-J. Mesoporous iron oxide-layered titanate nanohybrids: soft-chemical synthesis, characterization, and photocatalyst application. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112 (38), 14853–14862. 10.1021/jp805488h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ide Y.; Shirae W.; Takei T.; Mani D.; Henzie J. Merging cation exchange and photocatalytic charge separation efficiency in an anatase/K2Ti4O9 nanobelt heterostructure for metal ions fixation. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57 (10), 6045–6050. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K.; Tominaka S.; Yoshihara S.; Ohara K.; Sugahara Y.; Ide Y. Room-temperature rutile TiO2 nanoparticle formation on protonated layered titanate for high-performance heterojunction creation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9 (29), 24538–24544. 10.1021/acsami.7b04051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousef A. K.; Sanad M.; Rashad M. M.; El-Sayed A.-A. Y.; Ide Y. Facile synthesis of layered titanate/rutile heterojunction photocatalysts. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2019, 92 (11), 1801–1806. 10.1246/bcsj.20190180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T.; Fjellvåg H.; Norby P. Defect chemistry of a zinc-doped lepidocrocite titanate CsxTi2–x/2Znx/2O4 (x = 0.7) and its protonic Form. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21 (15), 3503–3513. 10.1021/cm901329g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.; Reeves K. G.; Aguilar I.; Porras Gutierrez A. G.; Badot J.-C.; Durand-Vidal S.; Legein C.; Body M.; Iadecola A.; Borkiewicz O. J.; et al. Ordering of a nanoconfined water network around zinc ions induces high proton conductivity in layered titanate. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34 (9), 3967–3975. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.1c04421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ida S.; Unal U.; Izawa K.; Altuntasoglu O.; Ogata C.; Inoue T.; Shimogawa K.; Matsumoto Y. Photoluminescence spectral change in layered titanate oxide intercalated with hydrated Eu3+. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110 (47), 23881–23887. 10.1021/jp063412o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riss A.; Berger T.; Grothe H.; Bernardi J.; Diwald O.; Knözinger E. Chemical control of photoexcited states in titanate nanostructures. Nano Lett. 2007, 7 (2), 433–438. 10.1021/nl062699y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S.; Singh A.; Reeves K. G.; Badot J.-C.; Durand-Vidal S.; Legein C.; Body M.; Dubrunfaut O.; Borkiewicz O. J.; Tremblay B.; et al. Hydronium ions stabilized in a titanate-layered structure with high ionic conductivity: application to aqueous proton batteries. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32 (21), 9458–9469. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c03658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T.; Watanabe M. Osmotic swelling to exfoliation. Exceptionally high degrees of hydration of a layered titanate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120 (19), 4682–4689. 10.1021/ja974262l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mani D.; Tahawy R.; Doustkhah E.; Shanmugam M.; Arivanandhan M.; Jayavel R.; Ide Y. A rutile TiO2 nano bundle as a precursor of an efficient visible-light photocatalyst embedded with Fe2O3. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8 (19), 4423–4430. 10.1039/D1QI00565K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esmat M.; Farghali A. A.; El-Dek S. I.; Khedr M. H.; Yamauchi Y.; Bando Y.; Fukata N.; Ide Y. Conversion of a 2D lepidocrocite-type layered titanate into its 1D nanowire form with enhancement of cation exchange and photocatalytic performance. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58 (12), 7989–7996. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b00722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen P.; Ishikawa Y.; Itoh H.; Feng Q. Topotactic transformation reaction from layered titanate nanosheets into anatase nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113 (47), 20275–20280. 10.1021/jp908181e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto N.; Kuroda K.; Ogawa M. Exfoliation and film preparation of a layered titanate, Na2Ti3O7, and intercalation of pseudoisocyanine dye. J. Mater. Chem. 2004, 14 (2), 165–170. 10.1039/b308800f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B.; Gawande M. B.; Kute A. D.; Varma R. S.; Fornasiero P.; McNeice P.; Jagadeesh R. V.; Beller M.; Zbořil R. Single-Atom (Iron-Based) Catalysts: Synthesis and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121 (21), 13620–13697. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawande M. B.; Ariga K.; Yamauchi Y. Single-Atom Catalysts. Small 2021, 17 (16), 2101584. 10.1002/smll.202101584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui E.; Li H.; Zhang C.; Qiao D.; Gawande M. B.; Tung C.-H.; Wang Y. An advanced plasmonic photocatalyst containing silver(0) single atoms for selective borylation of aryl iodides. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2021, 299, 120674. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.120674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Zou Y.; Cruz D.; Savateev A.; Antonietti M.; Vilé G. Ligand–Metal Charge Transfer Induced via Adjustment of Textural Properties Controls the Performance of Single-Atom Catalysts during Photocatalytic Degradation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13 (22), 25858–25867. 10.1021/acsami.1c02243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruta V.; Sivo A.; Bonetti L.; Bajada M. A.; Vilé G. Structural Effects of Metal Single-Atom Catalysts for Enhanced Photocatalytic Degradation of Gemfibrozil. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5 (10), 14520–14528. 10.1021/acsanm.2c02859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide Y.; Ogawa M. Interlayer Modification of a Layered Titanate with Two Kinds of Organic Functional Units for Molecule-Specific Adsorption. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46 (44), 8449–8451. 10.1002/anie.200702360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T.; Nakano S.; Yamauchi S.; Watanabe M. Fabrication of titanium dioxide thin flakes and their porous aggregate. Chem. Mater. 1997, 9 (2), 602–608. 10.1021/cm9604322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y.; Balmer M. L.; Bunker B. C. Raman spectroscopic studies of silicotitanates. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104 (34), 8160–8169. 10.1021/jp0018807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godin R.; Wang Y.; Zwijnenburg M. A.; Tang J.; Durrant J. R. Time-resolved spectroscopic investigation of charge trapping in carbon nitrides photocatalysts for hydrogen generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (14), 5216–5224. 10.1021/jacs.7b01547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Zhou Y.; Bao J.; Zhang Y.; Fang J.; Zhao S.; Chen W.; Sheng X. Sn2+-doped double-shelled TiO2 hollow nanospheres with minimal Pt content for significantly enhanced solar H2 production. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6 (5), 7128–7137. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b01122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H.; Rosenfeld D. C.; Harb M.; Anjum D. H.; Hedhili M. N.; Ould-Chikh S.; Basset J.-M. Ni–M–O (M = Sn, Ti, W) Catalysts Prepared by a Dry Mixing Method for Oxidative Dehydrogenation of Ethane. ACS Catal. 2016, 6 (5), 2852–2866. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F.; Zhang G.; Guo Y.; Zhu B.; Huang W.; Zhang S. Flower-like hydrogen titanate nanosheets: preparation, characterization and their photocatalytic hydrogen production performance in the presence of Pt cocatalyst. RSC Adv. 2020, 10 (46), 27652–27661. 10.1039/D0RA03698F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soontornchaiyakul W.; Fujimura T.; Yano N.; Kataoka Y.; Sasai R. Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution over Exfoliated Rh-Doped Titanate Nanosheets. ACS Omega 2020, 5 (17), 9929–9936. 10.1021/acsomega.0c00204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang Q.; Yang S. Template Synthesis of Single-Crystal-Like Porous SrTiO3 Nanocube Assemblies and Their Enhanced Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5 (9), 3683–3690. 10.1021/am400254n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagyházi M.; Turczel G.; Anastas P. T.; Tuba R. Highly efficient ammonia borane hydrolytic dehydrogenation in neat water using phase-labeled CAAC-Ru catalysts. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8 (43), 16097–16103. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c06696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naldoni A.; Altomare M.; Zoppellaro G.; Liu N.; Kment Š.; Zbořil R.; Schmuki P. Photocatalysis with reduced TiO2: from black TiO2 to cocatalyst-free hydrogen production. ACS Catal. 2019, 9 (1), 345–364. 10.1021/acscatal.8b04068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal U.; Jagirdar B. R. Metal and alloy nanoparticles by amine-borane reduction of metal salts by solid-phase synthesis: atom economy and green process. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51 (23), 13023–13033. 10.1021/ic3021436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.