Abstract

Seven diazotrophs that grow well under Mo-deficient, N2-fixing conditions were isolated from a variety of environments. These isolates fall in the γ subdivision of the class Proteobacteria and have genes that encode the Mo nitrogenase (nitrogenase 1) and the V nitrogenase (nitrogenase 2). Four of the isolates also harbor genes that encode the iron-only nitrogenase (nitrogenase 3).

Azotobacter vinelandii, an aerobic nitrogen-fixing soil bacterium, was the first diazotroph that was shown to have three distinct nitrogenases (4). One of these nitrogenases is the classical molybdenum (Mo)-containing nitrogenase (nitrogenase 1), while the other two are Mo-independent nitrogenases (nitrogenases 2 and 3). Nitrogenase 1 is expressed in N-free media containing Mo and has been extensively characterized (17, 22, 29). Nitrogenase 2 is a vanadium (V)-containing nitrogenase and is expressed in N-free, Mo-deficient medium containing V (9–12, 24). Nitrogenase 3 is an iron-only nitrogenase and is expressed in Mo- and V-deficient N-free medium (7).

The diazotrophs which have been shown to have Mo-independent nitrogenase systems include physiologically and phylogenetically diverse laboratory microorganisms, such as Clostridium pasteurianum (30), Rhodobacter capsulatus (25–27), Anabaena variabilis (16, 28), Rhodospirillum rubrum (8, 20), Heliobacterium gestii (18), and Azospirillum brasilense (6).

In this report we describe the isolation of nitrogen-fixing bacteria from environmental sources.

Strains DU1, TP1, WA1, and WC1 were isolated from mostly aquatic samples collected at sites located within a 25-mile radius of Raleigh, N.C. Strains SM1 and SM2 were isolated from a salt marsh located near Beaufort, N.C., and strain WB3 was isolated from a salt marsh located near Wrightsville Beach, N.C. Mo-deficient, N-free modified Burk medium (−Mo,−N BM) (2) containing 2% sucrose was used for growth and enrichment procedures. To isolate strains from aquatic sources, 8 ml of source water and 18 ml of deionized water were mixed with 0.75 ml of 40× phosphate buffer (244 mM, pH 7.2) and 3 ml of 10× Burk medium sucrose-salts (total volume, approximately 30 ml) in a 300-ml sidearm flask. To isolate an organism (strain WC1) from wood chip mulch, a spatulaful of wood chips was added to 30 ml of −Mo,−N BM. The initial enrichment cultures were incubated at 30°C with vigorous shaking for approximately 48 h or until a significant increase in turbidity was observed. One to three milliliters of each enrichment culture was transferred into 30 ml of fresh −N,−Mo BM and incubated as described above. For the second and third transfers in liquid medium, the procedure described above was repeated, except that the inoculum was diluted 100-fold (300 μl of culture was added to 30 ml of fresh medium). One hundred microliters of the third transfer culture was streaked onto −Mo,−N BM agar (containing 1.5% purified agar [BBL, Becton Dickinson]). After 2 to 4 days of incubation at 30°C, single colonies were streaked onto fresh agar medium for isolation. This procedure was repeated (usually four to six times) until each isolate appeared to be a pure culture, as judged by colony morphology and microscopic examination results.

The strains isolated from salt marshes (SM1, SM2, and WB3) grew as clumps in liquid media; therefore, all subsequent studies with these strains were performed on solid agar media. All of the strains were gram negative, catalase positive, and motile. None of the strains grew at 4°C, but they all grew at 13°C and the best growth occurred at temperatures near 30°C. Strains SM1 and SM2 grew on agar medium in the presence of 7% NaCl, whereas WB3, the only other salt marsh isolate, was able to grow in the presence of only 1% NaCl. Strains DU1, TP1, and WA1 grew in liquid Burk medium containing N at pHs ranging from 5.5 to 8.5, and strain WC1 grew at pHs ranging from 4.5 to 8.5. All of the growth parameters described above were determined under non-nitrogen-fixing conditions.

The approximate cell sizes, as determined by scanning electron microscopy, were as follows: DU1, 3.5 by 1.5 μm; TP1, 2.2 by 1.6 μm; WA1, 2.2 by 1.9 μm; WB3, 2.2 by 1.7 μm; WC1, 2.2 by 1.6 μm; SM1, 1.2 by 0.6 μm; and SM2, 1.2 by 0.6 μm. It was interesting that DU1 appeared to divide by budding, as well as by binary fission.

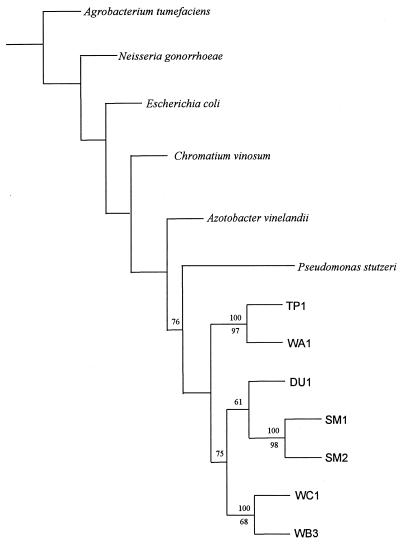

16S rRNA genes were amplified and isolated as described by Barns et al. (1) by using universal primers 515F and 1492R (19). A phylogenetic analysis of these genes indicated that all of the isolates are members of the γ subdivision of the class Proteobacteria (Fig. 1) and that they appear to be specifically related to the fluorescent pseudomonads.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic relationships between the environmental isolates and selected members of the Proteobacteria, as shown by an unrooted tree. Ten Pseudomonas strains used in the phylogenetic analysis are represented on the tree by Pseudomonas stutzeri. Bootstrap values (100 replicates) are shown at the branches for the environmental isolates; the values above the lines are DNA parsimony values, and the values below the lines are DNA maximum-likelihood values. Values less than 50% are not shown.

All of the strains grew on N-free agar medium in the presence of Mo or V and in the absence of Mo and V. Table 1 summarizes the results obtained for the four strains that grew without visible clumping in liquid media when growth was monitored with a Klett-Summerson colorimeter equipped with a no. 66 filter (red). Strains TP1 and WA1 grew diazotrophically in the presence of Mo or V or in the absence of these metals. These results suggest that isolates TP1 and WA1 utilize nitrogenase 1, 2, or 3. On the other hand, strains DU1 and WC1 grew in the presence of Mo or V but not in the absence of these metals. These results suggest that strains DU1 and WC1 have nitrogenases 1 and 2 but not nitrogenase 3. The finding that strains grew on N-free agar medium in the absence of Mo and V but not in liquid medium might be attributable to the presence of contaminating Mo or V in the purified agar. This possibility is consistent with the finding that strain CA70 (14), a mutant of A. vinelandii which lacks nitrogenase 3, grows on N-free agar medium in the absence of Mo and V but not in liquid medium having the same composition. Nitrogenase activity, as measured by acetylene reduction (3), was detected under all of the conditions which permitted diazotrophic growth and followed a pattern previously observed for A. vinelandii (4); i.e., cells grown in the presence of Mo gave significantly higher values than cells grown in the absence of Mo. The strains isolated from salt marshes (SM1, SM2, and WB3) exhibited nitrogenase activity when they were cultured on agar media in slants in the presence and absence of Mo or V, and as previously observed, the acetylene reduction values in the presence of Mo were considerably higher than the acetylene reduction values in the absence of Mo (results not shown). Nitrogenase activity was repressed by 10 mM NH4+ to different degrees for each of the three nitrogenase systems in the isolates (data not shown). An interesting difference between isolate TP1 and A. vinelandii is that TP1 did not grow in the presence of ammonium acetate at a concentration of 28 mM, the concentration ordinarily used for this nitrogen source in modified Burk medium. Preliminary results indicated that strain TP1 grows poorly or not at all in the presence of concentrations of NH4+ greater than 14 mM regardless of the accompanying anion.

TABLE 1.

Diazotrophic growth and whole-cell nitrogenase activity in liquid media

| Isolate | Addition to −Mo,−N BM | Generation time (h) | Nitrogenase activity (pmol of C2H4/Klett unit · ml−1 · 30 min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DU1 | NH4+ (10 mM) | 2.5 | —a |

| Na2MoO4 (1 μM) | 2.8 | 354 | |

| V2O5 (1 μM) | 3.6 | 34 | |

| None | ∞ | — | |

| TP1 | NH4+ (10 mM) | 2.2 | — |

| Na2MoO4 (1 μM) | 2.1 | 844 | |

| V2O5 (1 μM) | 2.8 | 116 | |

| None | 3.2 | 66 | |

| WA1 | NH4+ (10 mM) | 2.2 | — |

| Na2MoO4 (1 μM) | 2.6 | 524 | |

| V2O5 (1 μM) | 2.9 | 128 | |

| None | 3.2 | 54 | |

| WC1 | NH4+ (10 mM) | 2.0 | — |

| Na2MoO4 (1 μM) | 2.4 | 287 | |

| V2O5 (1 μM) | 2.9 | 148 | |

| None | ∞ | — |

—, the measured activity was no greater than the activity of the blank (trichloroacetic acid-treated cells).

DNA fragments containing A. vinelandii nifD (0.8-kb nifD insert of pTMR18 [5]), vnfD (1.4-kb vnfD insert of pVDSJ1 [13]), and anfD (1.08-kb anfD insert of pPJD3A2 [23]) genes coding for the α subunits of nitrogenases 1, 2, and 3, respectively, were used as hybridization probes in Southern blot analyses of EcoRI-digested genomic DNAs of the isolates. Table 2 shows the sizes of the fragments which hybridized with the nitrogenase gene probes. A. vinelandii CA and Pseudomonas fluorescens DNAs served as positive and negative controls, respectively. The DNAs of isolates SM1, SM2, TP1, and WA1 yielded hybridizing fragments for each of the nitrogenase gene probes, suggesting that these isolates have representative genes for the three known nitrogenase systems in A. vinelandii. The presence of fragments in the strain DU1, WB3, and WC1 DNAs which hybridized to the nifD and vnfD probes suggests that these strains have genes that encode nitrogenases 1 and 2. The DNAs of these three strains, however, lacked fragments that hybridized with the anfD gene probe. This observation is consistent with the inability of strains DU1 and WC1 to grow diazotrophically in liquid Mo-deficient medium lacking V, conditions which require nitrogenase 3 for diazotrophic growth (Table 1). The situation with strain WB3 is less clear since this strain does not grow well in liquid media, yet it grows and reduces acetylene on Mo-deficient agar medium in the absence of V. As mentioned above, it is possible that the purified agar contained trace amounts of Mo or V which could satisfy the requirements for nitrogenase 1 or 2.

TABLE 2.

DNA fragments in EcoRI digests of genomic DNAs hybridizing to nitrogenase gene probes on Southern blots

| Organism | Fragment size(s) (kb) with the following A. vinelandii nitrogenase gene probes:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| nifD | vnfD | anfD | |

| A. vinelandii CA | 1.4, 10.0, 14.0 | 1.0, 2.6, 7.0 | 3.5, 4.0 |

| P. fluorescens | NDa | ND | ND |

| DU1 | 1.4 | 1.8 | ND |

| SM1 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 2.4 |

| SM2 | 1.5 | 5.3 | 2.4 |

| TP1 | 1.4 | 2.1, 4.7 | 22.6 |

| WA1 | 1.4, 1.3 | 2.0, 4.7 | 2.7, 20.0 |

| WB3 | 8.0, 9.0, 23.0 | 1.7, 4.5 | ND |

| WC1 | 29.9 | 1.7, 4.6 | ND |

ND, DNA fragments hybridizing to nitrogenase gene probes were not detected.

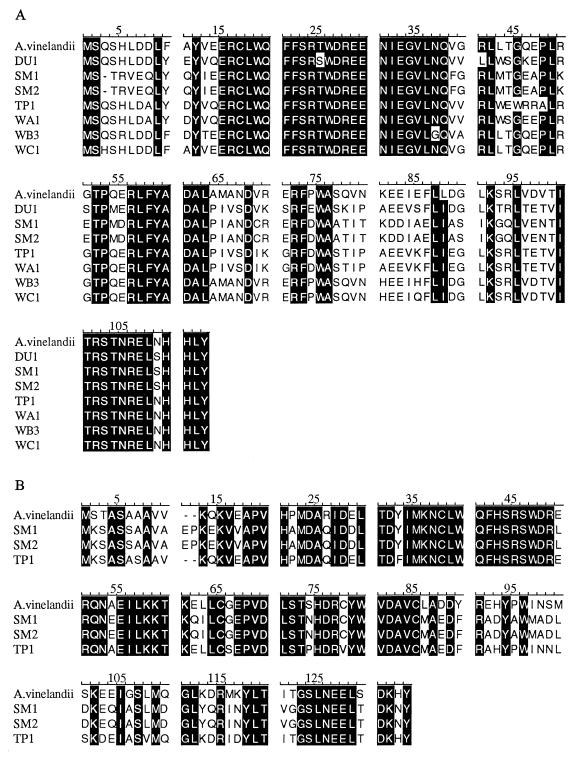

For PCR amplification of vnfG and anfG (genes which encode the δ subunits of nitrogenases 2 and 3, respectively), conserved sites in vnfD and anfD were used as the priming sites for the forward PCR primers, and conserved sites in vnfK and anfK were used as the priming sites for the reverse primers. For amplification of nifD, conserved sites in nifD were used for both the forward and reverse primers. Details concerning these primers and the PCR conditions used have been described previously (21). PCR products containing vnfG were obtained with genomic DNAs from all of the isolates, and the sizes were approximately 1.76 kb. Products (length, 0.49 kb) containing nifD were obtained from all of the isolates except strains WB3 and WC1. The only DNAs which yielded PCR products containing anfG were the DNAs of strains SM1, SM2, and TP1, and the product sizes were approximately 0.76 kb. The PCR results generally agree with the results obtained with Southern blots except that we were not able to detect nifD in strains WB3 and WC1 or anfG in WA1 when we used the PCR. The amino acid sequence data for the vnfG and anfG gene products shown in Fig. 2 indicate that there is a rather high degree of identity among these gene products in the isolates examined.

FIG. 2.

Comparisons of the amino acid sequences of VnfG (A) and AnfG (B). The amino acid sequences were deduced from the DNA sequences of PCR products and were aligned by using the Clustal-W algorithm. The sequences of A. vinelandii VnfG and AnfG were obtained from references 15 and 14, respectively.

In this study we found that N2-fixing bacteria having the ability to express Mo-independent nitrogenases can be readily isolated from environmental sources by using N-free enrichment media devoid of Mo. The ability to isolate these types of diazotrophs directly from environmental sources should expand our knowledge of diazotrophs that are able to express Mo-independent nitrogenases and should also provide information concerning the kinds of habitats in which these diazotrophs are found. The strains described in this report were isolated under highly aerobic conditions by using a medium containing sucrose as the carbon source. The use of microaerophilic and anaerobic enrichment conditions, as well as aerobic conditions, with a variety of carbon sources and medium formulations should increase our knowledge of the diverse diazotrophs that are known to be capable of using Mo-independent nitrogenases.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the nucleotide sequences of the nitrogen fixation genes are as follows: strain TP1 nifD, AF142477; strain TP1 vnfDGK, AF152908; strain TP1 anfDGK, AF152915; strain DU1 nifD, AF142478; strain DU1 vnfDGK, AF152909; strain WA1 nifD, AF152918; strain WA1 vnfDGK, AF152910; strain SM1 nifD, AF152920; strain SM1 vnfDGK, AF152911; strain SM1 anfDGK, AF152917; strain SM1 nifD, AF152919; strain SM2 vnfDGK, AF152912; strain SM1 anfDGK, AF152916; strain WB3 vnfDGK, AF152913; and strain WC1 vnfDGK, AF152914. The GenBank accession numbers for the 16S rRNA gene sequences are as follows: DU1, AF094765; WC1, AF094766; WB3, AF094767; WA1, AF094768; TP1, AF094769; SM1, AF094770; and SM2, AF094771.

Acknowledgments

We thank James Brown for help with the phylogenetic analysis and Julie Olson for advice concerning the marine isolates.

This was a cooperative study between the USDA Agricultural Research Service and the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service. This work was supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture NRI Competitive Grant 96-35305-3554.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barns S M, Fundyga R E, Jeffries M W, Pace N R. Remarkable archaeal diversity detected in a Yellowstone National Park hot spring environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1609–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop P E, Hawkins M E, Eady R R. Nitrogen fixation in molybdenum-deficient continuous culture by a strain of Azotobacter vinelandii carrying a deletion of the structural genes for nitrogenase (nifHDK) Biochem J. 1986;238:437–442. doi: 10.1042/bj2380437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bishop P E, Jarlenski D M L, Hetherington D R. Evidence for an alternative nitrogen fixation system in Azotobacter vinelandii. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7342–7346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bishop P E, Premakumar R. Alternative nitrogen fixation systems. In: Stacey G, Burris R H, Evans H J, editors. Biological nitrogen fixation. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall; 1992. pp. 736–762. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop P E, Rizzo T M, Bott K. Molecular cloning of nif DNA from Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:21–28. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.21-28.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakraborty B, Samadar K R. Evidence for the occurrence of an alternative nitrogenase system in Azospirillum brasilense. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;127:127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chisnell J R, Premakumar R, Bishop P E. Purification of a second alternative nitrogenase from a nifHDK deletion strain of Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:27–33. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.27-33.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis R, Lehman L, Petrovich R, Shah V K, Roberts G P, Ludden P W. Purification and characterization of the alternative nitrogenase from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1445–1450. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1445-1450.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eady R R, Richardson T H, Miller R W, Hawkins M, Lowe D J. The vanadium nitrogenase of Azotobacter chroococcum: purification and properties of the Fe protein. Biochem J. 1988;256:189–196. doi: 10.1042/bj2560189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eady R R, Robson R L, Richardson T H, Miller R W, Hawkins M. The vanadium nitrogenase of Azotobacter chroococcum: purification and properties of the VFe protein. Biochem J. 1987;244:197–207. doi: 10.1042/bj2440197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hales B J, Case E E, Morningstar J E, Dzeda M F, Mauterer L A. Isolation of a new vanadium-containing nitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii. Biochemistry. 1986;25:7251–7255. doi: 10.1021/bi00371a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hales B J, Langosch D J, Case E E. Isolation and characterization of a second nitrogenase Fe-protein from Azotobacter vinelandii. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15301–15306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobitz S, Bishop P E. Regulation of nitrogenase-2 in Azotobacter vinelandii by ammonium, molybdenum, and vanadium. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3884–3888. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.12.3884-3888.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joerger R D, Jacobson M R, Premakumar R, Wolfinger E D, Bishop P E. Nucleotide sequence and mutational analysis of the structural genes (anfHDGK) for the second alternative nitrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1075–1086. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.1075-1086.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joerger R D, Loveless T M, Pau R N, Mitchenall L A, Simon B H, Bishop P E. Nucleotide sequences and mutational analysis of the structural genes for nitrogenase 2 of Azotobacter vinelandii. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3400–3408. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3400-3408.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kentemich T, Danneberg G, Hundeshagen B, Bothe H. Evidence for the occurrence of the alternative, vanadium-containing nitrogenase in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;51:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J, Rees D C. Nitrogenase and biological nitrogen fixation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:389–397. doi: 10.1021/bi00168a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimble L K, Madigan M T. Evidence for an alternative nitrogenase in Heliobacterium gestii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;100:255–260. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: Wiley; 1991. pp. 115–175. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehman L J, Roberts G P. Identification of an alternative nitrogenase system in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5705–5711. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5705-5711.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loveless T M, Bishop P E. Identification of genes unique to Mo-independent nitrogenase systems in diverse diazotrophs. Can J Microbiol. 1999;45:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters J W, Fisher K, Dean D R. Nitrogenase structure and function: a biochemical-genetic perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:334–366. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Premakumar R, Jacobson M R, Loveless T M, Bishop P E. Characterization of transcripts expressed from nitrogenase-3 structural genes of Azotobacter vinelandii. Can J Microbiol. 1992;38:929–936. doi: 10.1139/m92-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robson R L, Eady R R, Richardson T H, Miller R W, Hawkins M, Postgate J R. The alternative nitrogenase of Azotobacter chroococcum is a vanadium enzyme. Nature (London) 1986;322:388–390. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider K, Gollan U, Drottboom M, Selsemeier-Voigt S, Müller A. Comparative biochemical characterization of the iron-only nitrogenase and the molybdenum nitrogenase from Rhodobacter capsulatus. Eur J Biochem. 1997;15:789–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider K, Müller A, Schramm U, Klipp W. Demonstration of a molybdenum- and vanadium-independent nitrogenase in a nifHDK-deletion mutant of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Eur J Biochem. 1991;195:653–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb15750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schüddekopf K, Hennecke S, Liese U, Kutsche M, Klipp W. Characterization of anf genes specific for the alternative nitrogenase and identification of nif genes required for both nitrogenases in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:673–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiel T. Characterization of genes for an alternative nitrogenase in the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6276–6286. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6276-6286.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yates M G. The enzymology of molybdenum dependent nitrogen fixation. In: Stacey G, Evans H J, Burris R H, editors. Biological nitrogen fixation. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1992. pp. 685–735. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zinoni F, Robson R M, Robson R L. Organization of potential alternative nitrogenase genes from Clostridium pasteurianum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1174:83–86. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(93)90096-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]