Abstract

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methylation is the most universal internal modification in eukaryotic mRNA. With elaborate functions executed by m6A writers, erasers, and readers, m6A modulation is involved in myriad physiological and pathological processes. Extensive studies have demonstrated m6A modulation in diverse tumours, with effects on tumorigenesis, metastasis, and resistance. Recent evidence has revealed an emerging role of m6A modulation in tumour immunoregulation, and divergent m6A methylation patterns have been revealed in the tumour microenvironment. To depict the regulatory role of m6A methylation in the tumour immune microenvironment (TIME) and its effect on immune evasion, this review focuses on the TIME, which is characterized by hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, acidity, and immunosuppression, and outlines the m6A-regulated TIME and immune evasion under divergent stimuli. Furthermore, m6A modulation patterns in anti-tumour immune cells are summarized.

Keywords: N6-methyladenosine (m6A), Tumour immune microenvironment, Hypoxia, Metabolic reprogramming, Acidity, Immune suppression, Immune cells, Immune evasion, Immune therapy

Background

The tumour immune microenvironment (TIME) comprises intratumour immunological components and orchestrates tumour immunity [1]. The high heterogeneity within the TIME makes immunotherapy challenging [2, 3]. Tumours exploit and reshape the TIME to avoid immune surveillance [4, 5]. Hence, harnessing the TIME to boost anti-tumour immunity has been a core strategy of immunotherapy [6, 7]. Epigenetic modification has been extensively investigated in tumours and has a pivotal role in tumour immunoediting [8–10]. The regulatory role of DNA methylation in tumour immunity has been well characterized over the past few years [11]. Recent evidence has moved forwards to the role of diverse RNA methylation mechanisms in TIME modulation and revealed their utility as promising targets in immunotherapy [12, 13].

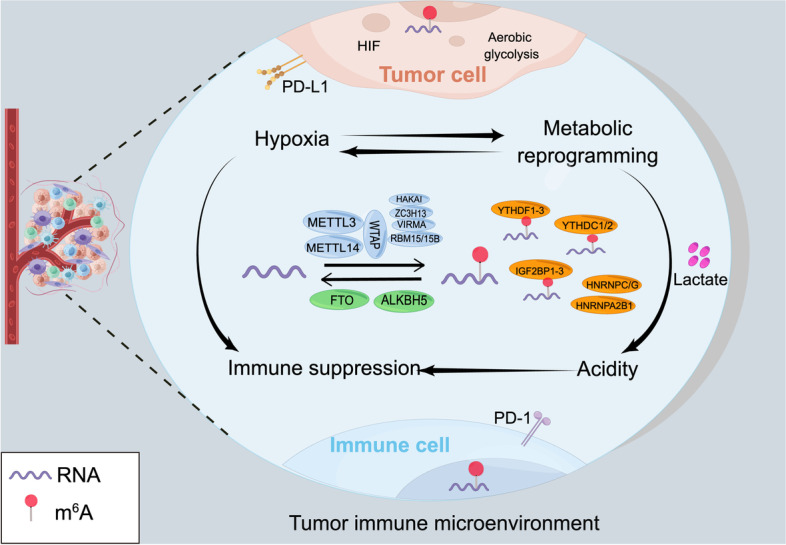

Although more than 170 types of chemical RNA modifications have been identified since the first discovery in the 1970s [14], the biological functions of RNA methylation were gradually revealed until the last decade [15, 16]. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA methylation is the most prevalent internal mRNA modification in eukaryotic cells. With the development of transcriptome-wide sequencing techniques, the role of m6A methylation in many cellular functions and disease pathologies has been well-characterized [17–19]. Recently, aberrant m6A RNA modification has been identified in various tumours [20], participating in tumorigenesis, metastasis, chemo- and radioresistance [21–23]. Growing evidence has revealed an emerging role of m6A methylation in regulating the TIME and tumour immunity [24, 25]. Previous reviews have provided a clear and systematic summary of m6A regulation in various tumours and immune cells, as well as the application of strategies related to m6A methylation in cancer prognostication and therapy [26–29]. This review outlines the regulatory role of m6A modification in the intricate TIMEs, including hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, acidity, and immune suppression, and further describes the latest research progress related to m6A modification-facilitated tumour immune evasion in diverse TIMEs. Furthermore, m6A methylation patterns in several tumour-infiltrating immune cells are summarized (Fig. 1). Finally, a few future prospects on m6A methylation are also listed in the last section. Thus, this review provides an overview of m6A-regulated tumour immune surveillance and novel insights into immunotherapy.

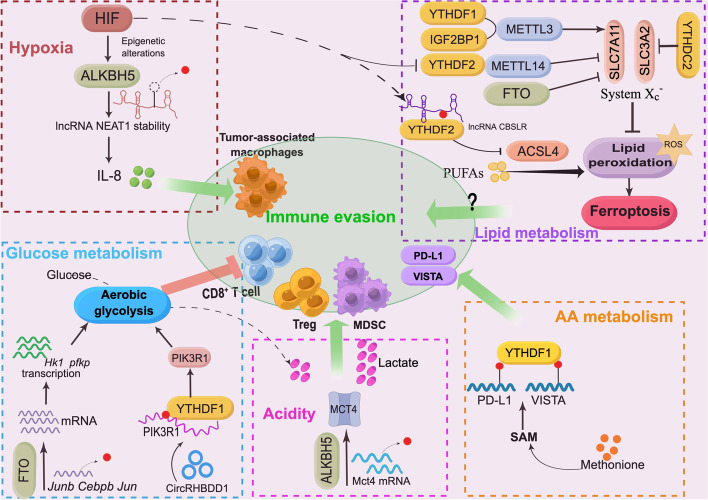

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the topic of this review. The tumour immune microenvironment (TIME) is characterized by hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, acidity, and immune suppression. There is potential crosstalk between hypoxia and metabolic reprogramming (HIF signalling can induce tumour metabolic reprogramming, and altered metabolism affects oxygen consumption in tumours). Accumulated lactate generated by high aerobic glycolysis forms an acidic TIME. Hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, and acidity promote immune suppression and lead to tumour immune evasion. This review provides an overview of m6A methylation patterns in the TIME and immune cells and the role of m6A methylation in tumour immune escape

m6A RNA modification

m6A RNA modification is a critical posttranscriptional mechanism that regulates RNA metabolism and biological functions [30]. With a dynamic and reversible process modulated by 3 types of proteins, writers, erasers, and readers, the functional effects of m6A methylation are accomplished. m6A writers install methyl groups on target RNA, while erasers remove the methyl group from RNA to maintain the reversible process. Through m6A modification, marked RNAs are specifically recognized and tethered by m6A readers. These RNA-binding proteins perform distinct functions, affecting RNA splicing, nuclear export, stability, translation, and degradation, thus regulating gene expression [31]. Aberrant m6A methylation in tumour development promotes oncogenes expression in a context-dependent manner, driving the tumour-promoting effect [32, 33]. In addition to performing the functional effects in tumour development, m6A methylation can also be altered by tumour therapy. The m6A deposition occurs at UV-induced DNA damage sites within 2 min in response to UV irradiation, facilitating the recruitment of DNA polymerase κ for DNA repair and cell survival, which indicates a crucial role of dynamic m6A RNA modification in tumour radioresistance as well as a potential target for improving radiotherapy [34].

m6A writers

m6A writers are methyltransferases responsible for the installation of methyl groups on target RNA. Canonical methyl addition is catalysed by a writer complex comprised of multifunctional subunits. Methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3) and methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) form a heterodimer as the writer complex core; the former possesses catalytic ability, while METTL14 allosterically activates METTL3 and facilitates RNA binding [35]. Additional adaptors and interactors are assembled into the writer complex. William tumour 1-associated protein (WTAP) is essential for nuclear localization of the complex core and m6A formation in mammalian cells. Two paralogous RNA binding motif proteins, RNA binding motif protein 15 (RBM15) and RBM15B, are reported to interact with METTL3 in a WTAP-dependent manner, contributing to methylation specificity. Other components, including zinc-finger CCCH domain-containing protein 13 (ZC3H13), vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA, also known as KIAA1429), and HAKAI, have been identified as WTAP interactors that are essential to m6A formation [36]. m6A methylation has sequence specificity, and METTL3/14 complex-mediated m6A methylation is preferentially enriched at RRACH (R = A or G; H = A, C, or U) motifs [37], which are widely used to identify m6A methylation.

m6A erasers

m6A erasers mediate the removal of internal m6A from RNA, facilitating reversible, dynamic m6A methylation to modulate complex processes. M6A demethylation is catalysed by 2 enzymes, fat-mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase ALKB homologue 5 (ALKBH5). FTO was the first identified demethylase and mediates the demethylation of m6A in mRNA and U6 RNA [38]. ALKBH5 has been discovered to function as an exclusive m6A regulator rather than modulating other types of RNA modifications; it demethylates specific transcripts at the 3’UTR and expedites mRNA export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Growing evidence has shown that FTO- and ALKBH5-mediated m6A demethylation is involved in various tumours [39–42], displaying biological context-dependent functions. FTO is largely enhanced in some leukaemia cells and promotes leukaemia progression through multiple signalling pathways [43, 44]. FTO also serves as an oncogene in other tumours, such as melanoma [45] and breast cancer [46]. ALKBH5 expression is induced in hypoxia and facilitates HIF-regulated biological events and diseases [47, 48].

m6A readers

m6A readers are RNA-binding proteins with distinct regulatory effects. By specifically recognizing and anchoring m6A-bearing RNAs, reader proteins affect RNA splicing, nuclear transport, stability, translation, and RNA decay [49]. The YTH domain-containing proteins, including YTHDF1-3 and YTHDC1-2, were the first identified RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), the YTH domain is responsible for specific RNA binding. The cytosolic YTHDF family possesses distinct functions. YTHDF1 promotes RNA translation through interaction with eIFs [50]. YTHDF2 is the dominant protein responsible for selective RNA decay [51]. YTHDF3 cooperates with YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 to accelerate either translation or degradation of target transcripts. YTHDF3 deletion decreased the RNA binding specificity of YTHDF1-2 [52]. This dynamic and integrated function of the DF family represents a delicate regulatory mechanism of m6A methylation. The nuclear reader YTHDC1 binds to SRSF3 to regulate RNA splicing and nuclear export [53]. YTHDC2 regulates RNA translation and stability, exerting various regulatory effects [54–56]. YTHDC2 is upregulated in several cancers but possesses a tumour-suppressive role in lung cancer [57, 58]. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP1-3) are a class of m6A binding proteins that promote the stability and expression of target genes, exhibiting oncogenic activity in tumours [59]. Additionally, cytosolic METTL3 also serves as a reader, enhancing mRNA translation through interaction with the eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIF3h [60].

m6A methylation regulates TIME reprogramming and affects immune evasion

Cancer cells reshape the TIME through multiple mechanisms, leading to rapid proliferation and escape from host immune surveillance [61, 62]. The altered TIME is characterized by increased oxygen consumption, nutrient deprivation, accumulation of metabolites, and immune dysregulation, which form an extracellular niche with hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, and immune suppression, facilitating tumour immune evasion and leading to poor efficacy of immunotherapy [63]. Recent evidence has highlighted that m6A methylation is a mechanism that is indispensable in reshaping the TIME and regulating tumour immune surveillance.

m6A methylation responds to a hypoxic TIME and favours immune evasion

Hypoxia is one of the detrimental hallmarks of solid tumours and is generated from the augmentation of oxygen consumption and abnormal vascularization in the tumour context [62, 64]. Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) are transcriptional activators and principal regulators that regulate target genes at the transcriptional and translational levels to induce tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, metastasis, and metabolic adaptation under hypoxic stress [65–67]. An increasing number of investigations have unravelled the mechanisms of HIF-driven tumour immunity and immune evasion [68–70]. HIFs hinder the type I IFN pathway and facilitate immune suppression in numerous tumours [71]. HIF-1α enhances programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression on myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), macrophages, and tumour cells, impairing T-cell activation [72]. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), HIF-1 enhances the enrichment of MDSCs [73]; additionally, HIF-2α deletion in cancer-associated fibroblasts in pancreatic cancer reduces tumour infiltration of immune-suppressive immune cells, including M2 TAMs and Tregs, restoring the efficacy of immunotherapy [74]. Recent evidence has revealed that hypoxia in brain tumours restrains the anti-tumour immunity of γδ T cells [75]. Notably, hypoxia is a variable factor that directs epigenetic alterations in tumours, and the modulation of hypoxia in the TIME is closely linked to epigenetic reprogramming [76, 77].

Recent evidence has shown that key m6A enzymes are distinctly regulated in various hypoxic cancer cells and revealed the critical role of m6A modification in hypoxia-mediated tumour progression, malignancy, and chemoresistance. Downregulated METTL3 expression in the hypoxic TIME weakens the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib by reducing YTHDF1-promoted transcriptional stability of FOXO3 [78] (Table 1). ALKBH5 and FTO exhibit distinct regulatory roles in hypoxic tumours. Increased ALKBH5 expression induced by hypoxia maintains the stem-like cell phenotype and tumorigenicity of breast cancer stem cells (BCSCs) and endometrial cancer stem-like cells (ECSCs) in the hypoxic TIME in an m6A-dependent manner [79, 80]. Decreased FTO expression induced by hypoxia facilitated colorectal cancer (CRC) metastasis by inhibiting IGF2BP3-facilitated upregulation of metastasis-associated protein 1 (MTA1) [81]. These results reveal an oncogenic role of ALKBH5 and a tumour-suppressive role of FTO in hypoxic tumours. m6A reader proteins are context-dependent effectors of m6A methylation. Indeed, numerous studies have indicated multiple regulatory effects of m6A readers in hypoxia-driven tumours. Hypoxia can reprogram the TIME through autophagy, and a recent study found that the induction of YTHDF1 expression by HIF-1α contributed to the induction of autophagy and autophagy-related HCC progression [82]. YTHDF2 upregulation by HIF-1α promotes cancer cell proliferation in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) [83] and lung squamous carcinogenesis (LUSC) [84]. Another study showed that HIF-2α-restrained YTHDF2 stimulated inflammation and impaired vascular normalization in HCC through the disruption of YTHDF2-facilitated decay of IL-11 and serpin family E member 2 (SERPINE2) mRNA [85]. Hypoxia-induced lncRNA KB-1980E6.3 recruited IGF2BP1, which further increased the stability of c-Myc mRNA, facilitating self-renewal of BCSCs and tumorigenesis [86]. IGF2BP3 knockdown in stomach cancer cells inhibited hypoxia-driven cell migration and angiogenesis by downregulating HIF-1α expression [87]. m6A methylation-modulated hypoxic tumours also dictate metabolic reprogramming, as described in the next section. These data provide solid evidence for the possibility of reversible and dynamic modulation of the m6A-regulated hypoxic tumour environment and novel insights into tumour therapy. Although there are no direct data on m6A-mediated immunoregulation, these investigations have led us to further explore the regulatory role of m6A in the hypoxic TIME and immunotherapy. Notably, the latest research links m6A methylation to a hypoxia-driven TIME phenotype in glioblastoma (GBM) and suggests that m6A methylation is involved in immune evasion. Dong and his colleagues found that ALKBH5 expression induced by hypoxia promoted the recruitment of TAMs in GBM and an immunosuppressive microenvironment in allograft tumours [88]. ALKBH5-mediated removal of m6A deposition from the lncRNA NEAT1 enhanced transcript stability and NEAT1-mediated paraspeckle assembly, which resulted in the relocation of the transcriptional repressor SFPQ from the CXCL8 promoter to paraspeckles, increasing CXCL8/IL8 expression and contributing to TAM enrichment and tumour progression. That study illustrated the mechanism by which ALKBH5 facilitates an immunosuppressive TIME in the hypoxic GBM niche, providing novel insights into m6A-guided immunotherapy (Fig. 2). In line with previous studies, these data suggest a tumour-promoting role of ALKBH5. Based on the critical role of hypoxia in immune escape, much clarification of the epigenetic reprogramming that occurs in the hypoxic TIME and its role in tumour immunity is needed.

Table 1.

m6A modulation under diverse factors in the TIME

| Factor in the TIME | m6A regulator | Cancer type | Molecular mechanism | Effect on tumours and immune surveillance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypoxia | METTL3 | HCC | HIF-METTL3-FOXO3 axis, enhancing FOXO3 mRNA stabilization by YTHDF1 | Promoting sorafenib resistance | [78] |

| ALKBH5 | BCSC | HIF-ALKBH5-NANOG axis, enhancing NANOG mRNA and protein level | Promoting cancer stem-cell like phenotype and tumorigenesis | [79] | |

| ALKBH5 | ECSC | HIF-ALKBH5-SOX2 axis, enhancing SOX2 transcription | Promoting cancer stem-cell like phenotype and tumorigenesis | [80] | |

| FTO | CRC | Repressing MTA1 mRNA stability by IGF2BP2 | Inhibiting cancer metastasis and progression | [81] | |

| YTHDF1 | HCC | Enhancing ATG2A and ATG14 translation | Enhancing autophagy and autophagy-steered HCC progression | [82] | |

| YTHDF2 | AML | AML1/ETO-HIF1α-YTHDF2 axis, decreasing total m6A level | Promoting cancer proliferation | [83] | |

| YTHDF2 | LUSC | Activating of mTOR/AKT | Promoting tumorigenesis and invasion, inducing EMT | [84] | |

| YTHDF2 | HCC | HIF-2α-YTHDF2, preventing IL-11 and SERPINE2 RNA decay | Inducing inflammation-driven malignancy and disrupting of vascular normalization | [85] | |

| IGF2BP1 | BCSC | Hypoxic lncRNA KB-1980E6.3/IGF2BP1/c-Myc axis, inducing c-Myc mRNA stability | Promotion of self-renewal and tumorigenesis | [86] | |

| IGF2BP3 | SC | Inducing of HIF1A mRNA expression | Retaining HIF-mediated cell migration and angiogenesis | [87] | |

| ALKBH5 | GBM | Enhancing lncRNA NEAT1 transcript stability | Promoting IL8 expression, leading to TAM enrichment and immunosuppressive TIME | [88] | |

| Glycolysis reprogramming | METTL3 | CC | Enhancing HK2 mRNA stability through YTHDF1 | Promoting glycolysis and tumorigenesis | [89] |

| METTL3 | CRC | METTL3/LDHA axis, enhancing LDHA transcription and translation through HIF-1 alfa and YTHDF1, respectively. | Inducing 5-FU chemoresistance | [90] | |

| METTL3 | CRC | Stabilizing transcripts of HK2 and GLUT1 through IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, respectively | Promoting tumour glycolysis and cancer progression | [91] | |

| METTL3 | CC, HCC | m6A/PDK4 axis, enhancing PDK4 translation and mRNA stability through YTHDF1/eEF-2 and IGF2BP3 | Promoting tumour glycolysis and cancer progression | [92] | |

| METTL3, ALKBH5 | LUAC | Enhancing ENO1 translation through YTHDF1 | Promoting tumour glycolysis and tumorigenesis | [93] | |

| METTL14 | HCC | METTL14-USP48-SIRT6 axis, enhancing USP48 mRNA stability | Attenuating tumour glycolysis and malignancy | [94] | |

| METTL14 | RCC | Repressing BPTF mRNA stability | Inhibiting tumour glycolysis and distal lung metastasis | [95] | |

| METTL14 | GC | Repressing LHPP expression | Promoting tumour glycolysis and cancer progression | [96] | |

| WTAP | BCSC | ERK1/2-WTAP-ENO1, increasing ENO1 mRNA stability | Promoting tumour glycolysis and cancer progression | [97] | |

| WTAP | GC | Enhancing stability of HK2 mRNA | Promoting tumour glycolysis and cancer progression | [98] | |

| KIAA1429 | CRC | Enhancing stability of HK2 mRNA | Promoting tumour glycolysis and cancer progression | [99] | |

| FTO | AML | FTO/PFKP/LDHB axis, upregulating the expression of PFKP and LDHB. | Promoting tumour aerobic glycolysis | [100] | |

| FTO | PTC | Decreasing stability of APOE mRNA by IGF2BP2 | Attenuating tumour glycolysis and cancer growth | [101] | |

| FTO | LUAC | Wnt/β-catenin/FTO/c-Myc, FTO inhibits MYC mRNA translation | Inhibiting tumour glycolysis and tumorigenesis | [102] | |

| ALKBH5 | Bca | Suppressing CK2α mRNA stability | Suppressing tumour glycolysis and cisplatin resistance | [103] | |

| IGF2BP2 | CRC | LINRIS-IGF2BP2-MYC axis, enhancing MYC mRNA stability | Promoting tumour glycolysis and cancer progression | [104] | |

| YTHDF1 | BC | YTHDF1-PKM2, upregulating PKM2 expression | Promoting tumour glycolysis, cancer growth and metastasis | [105] | |

| YTHDF3 | PC | Promoting LncRNA DICER-AS1 degradation | Promoting tumour glycolysis | [106] | |

| YTHDC1 | PDAC | YTHDC1/miR-30d/RUNX1axis, promoting miR-30d and repressing RUNX1. | Attenuating tumour glycolysis and tumorigenesis | [107] | |

| FTO | Melanoma, NSCLC | Enhancing transcripts of c-Jun, JunB, and C/EBPβ | Promoting tumour glycolysis and immune evasion | [108] | |

| YTHDF1 | HCC | CircRHBDD1/YTHDF1/PIK3R1 axis, enhancing PIK3R1 translation | Promoting tumour glycolysis and restraining PD-1 therapy | [109] | |

| Lipid metabolism reprogramming | m6A writer complex, m6A erasers | HCC | m6A methylation negatively regulates CES2 expression by YTHDC2. | m6A methylation augment increased lipid accumulation | [110] |

| METTL3 | HCC | Enhancing lncRNA LINC00958 stability | Promoting lipogenesis and tumour progression | [111] | |

| FTO | EC | Enhancing HSD17B11 expression by YTHDF1 | Promoting lipid droplets and tumour development | [112] | |

| METTL3, METTL14 | CRC | Impairing of RNA decay of DEGS2, promoting DEGS2 levels | Inducing lipid dysregulation, tumour progression | [113] | |

| METTL3 | GBM | Stimulating SLC7A11 mRNA splicing and maturation | Inhibiting ferroptosis | [114] | |

| METTL3 | HB | m6A/IGF2BP1/SLC7A11 axis, preventing SLC7A11deadenylation. | Enhancing ferroptosis resistance | [115] | |

| METTL3 | LUAC | Stabilizing SLC7A11 m6A modification | Promoting tumour growth and inhibiting ferroptosis | [116] | |

| FTO | PTC | Promoting SLC7A11 downregulation | Promoting ferroptosis | [117] | |

| METTL14 | HCC | HIF-1α/METTL14/YTHDF2/SLC7A11 axis, disrupting METTL14 mediated SLC7A11 silencing by YTHDF2 | Inhibiting ferroptosis | [118] | |

| YTHDC2 | LUAC | YTHDC2/HOXA13/SLC3A2 axis, destabilizing HOXA13 mRNA and inhibiting SLC3A2 expression | Inducing ferroptosis | [119] | |

| YTHDF2 | GC | CBSLR/YTHDF2/CBS signalling, decreasing the stability of CBS mRNA and promoting ACSL4 degradation | Inhibiting ferroptosis | [120] | |

| AA metabolism reprogramming | FTO | CRC | FTO/YTHDF2/ATF4, disrupting ATF4 RNA decay by YTHDF2 | Promoting autophagy activation and compromising antitumour effect | [121] |

| FTO | ccRCC | Enhancing SLC1A5 expression | Promoting tumour growth and survival | [122] | |

| YTHDF1 | CRC | Enhancing GLS1 synthesis. | Promoting glutamine uptake and cisplatin resistance | [123] | |

| YTHDF1 | CRC | Dietary methionine and YTHDF1 promotes m6A methylation and translation of PD-L1 and VISTA | Inhibiting antitumour immunity. | [124] | |

| Acidity | ALKBH5 | Melanoma, CRC | Enhancing Mct4 mRNA levels | Enhancing extracellular lactate content and the promoting Treg and MDSC enrichment | [125] |

| METTL3 | CRC | METTL3/m6A/JAK/STAT3 axis, METTL3 lactylation promotes JAK translation. | Promoting immunosuppression of tumour-infiltrating myeloid cells. | [126] | |

| Immune suppression | METTL3 | BCa | JNK/METTL3/PD-L1, enhancing PD-L1 mRNA stability by IGF2BP1 | Promoting tumour immune escape | [127] |

| METTL3 | BC | METTL3/IGF2BP3 axis, promoting stabilization of PD-L1 mRNA | Inhibiting immune surveillance | [128] | |

| METTL3 | NSCLC | YTHDC1/circIGF2BP3, promoting circularization of circIGF2BP3 | Facilitating PD-L1 deubiquitination and promoting immune escape | [129] | |

| METTL14 | CCA | METTL14/Siah2/PD-L1 axis, enhancing Siah2 degradation by YTHDF2 | Inhibiting PD-L1 ubiquitination and immune surveillance | [130] | |

| METTL14 | HCC | METTL14/MIR155HG/PD-L1 axis, stabilizing MIR155HG | Facilitating PD-L1 upregulation and tumour immune escape | [131] | |

| ALKBH5 | ICC | ALKBH5/PD-L1, preventing YTHDF2-mediated PD-L1 RNA decay | Sustaining PD-L1 expression and inhibiting immune surveillance | [132] | |

| ALKBH5 | HNSCC | ALKBH5/RIG-I/IFNα axis, inhibiting mRNA maturation of DDX58 that encodes RIG-1 | Inhibiting RIG-I-mediated IFNα secretion and promoting tumour progression | [133] | |

| FTO | AML | FTO/m6A/LILRB4, enhancing LILRB4 expression | Promoting cancer stem cell self-renewal and immune escape | [134] | |

| FTO | Melanoma | Preventing YTHDF2-mediated mRNA decay of PD-1, CXCR4, SOX10 | Promoting anti-PD-1 resistance | [135] | |

| FTO | OSCC | Promoting the stability and expression of PD-L1 transcripts | Promoting immune resistance and tumour progression | [136] | |

| METTL3 | CRC | m6A-BHLHE41-CXCL1/CXCR2 Axis, increasing CXCR1 transcription through m6A-promoted BHLHE41 expression. | Enhancing MDSCs migration and inhibiting CD8+T cells | [137] | |

| METTL3, YTHDF2 | GBM | Active YY1–CDK9 transcription elongation complex enhanced METTL3, YTHDF2 levels | Promoting immune suppressive TIME | [138] | |

| ALKBH5 | HCC | ALKBH5/MAP3K8 axis, enhancing MAP3K8 expression | Promoting tumour growth, metastasis and PD-L1+macrophage recruitment | [139] |

m6A N6-methyladenosine, HCC Hepatocellular carcinoma, BCSC Breast cancer stem cell, ECSCs Endometrial cancer stem cells, CRC Colorectal cancer, AML Acute mygeeloid leukaemia, LUSC Lung squamous carcinogenesis, SC Stomach cancer, GBM Glioblastoma, CC Cervical cancer, CRC Colorectal cancer, LUAC Lung adenocarcinoma, RCC Renal carcinoma, GC Gastric cancer, PTC Papillary thyroid carcinoma, BCa Bladder cancer, BC Breast cancer, PC Pancreatic cancer, PDAC Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, NSCLC Non-small cell lung carcinoma, EC Esophageal cancer, HB Hepatoblastoma, ccRCC Renal clear cell carcinoma, ICC Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, HNSCC Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, OSCC Oral squamous cell carcinoma

Fig. 2.

m6A methylation reshapes the TIME and affects tumour immune evasion under divergent factors. The predominant driving factors in the TIME include hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, and acidity. PUFAs, polyunsaturated fatty acids

m6A methylation regulates metabolic reprogramming in the TIME and immune escape

Metabolic reprogramming is a primary mechanism for tumour immune evasion [63]. In the TIME, proliferating cancer cells compete for nutrients with immune cells, and this nutrient restriction hampers the function and anti-tumour immunity of immune cells, favouring immune evasion. Additionally, metabolic alterations in glucose, lipid, and amino acid (AA) levels induce accumulations of metabolites that serve as checkpoints to regulate immune responses in multiple metabolic pathways [140]. Extensive evidence has shown that m6A modification is widely involved in metabolic reprogramming and affects tumorigenesis, metastasis, and chemoresistance.

Glucose metabolism

Glucose metabolism is the most essential energy process for tumours. Tumour cells preferentially choose glycolysis pathways over oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) for rapid growth (the Warburg effect) [141]. Metabolic alterations are also critical for immunoregulation in the TIME [142] and dictate the function of immune cells. For instance, significantly increased glycolytic metabolism with downregulation of the OXPHOS pathway is present in activated T cells, dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells, and M1 macrophages as well as neutrophils [143]. Hence, glycolytic metabolism is essential for maintaining adaptive and humoral immunity, and tumour-driven glucose restriction in the TIME dampens the function of tumour-infiltrating immune cells, leading to immune escape [144–146]. Moreover, a hypoxic TIME prompts tumour glycolytic activity and drives an immune-excluded TIME [147, 148]. Targeting glycolysis to reprogram metabolism in tumours and immune cells has been considered a promising strategy for combination therapy to improve the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockades (ICBs) [149].

Studies have shown that m6A methylation facilitates glycolytic reprogramming through modulation of the expression of multiple glycolysis-related genes and signalling pathways in various tumours. METTL3-mediated m6A modification has a positive regulatory effect on glycolysis in numerous tumours, although it acts on different pathways [89–93]. METTL14 has a distinct glycolysis-regulating effect in tumours. METTL14 impedes HCC cell glycolysis through the METTL14-USP48-SIRT6 axis [94]. METTL14 deficiency in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) promotes distal lung metastasis by enhancing glycolytic reprogramming [95]. However, a glycolysis-promoting role of METTL14 through the repression of LHPP, which inhibits cancer cell metabolism, has been reported in gastric cancer (GC) [96]. Other m6A methyltransferases, including WTAP and KIAA1429, have been found to have a glycolysis-promoting role in cancers [97–99]. The m6A demethylase FTO regulates multiple key enzymes and pathways that control aerobic glycolysis in distinct cancer cells [100–102]. ALKBH5 suppresses casein kinase 2 (CK2) α-mediated glycolysis in bladder cancer (BCa), enhancing the sensitivity of tumour cells to cisplatin [103]. The m6A reader protein IGF2BP2 (IMP2) is responsible for RNA stability and exhibits a role in facilitating tumour glycolytic reprogramming by stabilizing effectors that promote aerobic glycolysis [104]. m6A binding proteins of the YTH family modulate the Warburg effect depending on their functions. YTHDF1 plays a cancer-promoting role and enhances glycolysis by upregulating PKM2 and HK2 mRNA levels in an m6A-dependent manner [89, 105]. YTHDF3 has been reported to have a glycolysis-promoting effect in pancreatic cancer because it drives the degradation of the lncRNA DICER-AS1, which inhibits glycolytic metabolism [106]. Another study revealed that YTHDC1 stimulates the cancer suppressor miR-30d, attenuating glycolysis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [107] (Table 1). Mounting evidence indicates that glycolytic reprogramming in cancers is widely modulated by m6A modification. As such, how does m6A-driven metabolic reprogramming affect anti-tumour immunity and immunotherapy? Recent studies have provided evidence to answer this question. Xu and her colleagues discovered that tumour-derived FTO dampens CD8+T cell activation and effector function by rewiring tumour glycolysis. FTO inhibition by the small molecule Dac51 removes metabolic barriers in T cells and blocks tumour immune evasion through glycolytic reprogramming; moreover, Dac51 treatment is synergistic with anti-PD-L1 therapy [108]. Cai et al. recently discovered that the augmentation of HCC cell glycolysis by circular RHBBD1 restrained PD-1-targeted therapy through increased PIK3R1 translation induced by YTHDF1 [109]. That study revealed that targeting circRHBDD1/YTHDF1/PIK3R1 in HCC has an immune-enhancing effect (Fig. 2). These results prove that reprogramming the RNA epitranscriptome is a potential strategy for immunotherapy.

Lipid metabolism

Lipid metabolism reshapes the TIME and regulates immune responses, affecting tumour immune escape [150]. Fatty acid (FA) catabolism favours the effector function of CD8+ T cells in the TIME [151]. Fatty acid oxidation (FAO) inhibits the activation of tumour-killing T effector cells (Teffs) while promoting the proliferation of Tregs [152]. Cholesterol regulates immune function in multiple ways. A high cholesterol content in the TIME induces T-cell exhaustion and is correlated with the upregulation of immune-inhibitory molecules [153]. The inhibition of cholesterol esterification potentiates the effector function of CD8+ T cells [154]. Additionally, the increased levels of citrate and succinate resulting from the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle bolster the effector function of DCs and macrophages [155]. Tumour lipid peroxidation drives ferroptosis, and dysregulated lipid metabolism in ferroptotic cancer cells modulates tumour immunity [156]. Lipid metabolites released from ferroptotic cancer cells drive immune cells to mobilize within tumour cells. The released oxidized lipid mediators hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs) activate anti-tumour immunity by recruiting immune cells to find ferroptotic tumour cells. PEG2 derived from lipid metabolism suppresses the tumoricidal effect of NK cells, cytotoxic T cells, and conventional type 1 DCs, mediating immune evasion [157]. Immune cells also undergo ferroptosis with lipid peroxidation, affecting anti-tumour immunity.

Mounting evidence indicates that m6A-driven lipid metabolism reprogramming is associated with multiple metabolic diseases [158, 159]. Recent studies have investigated m6A methylation in tumour lipid metabolism. m6A methylation regulates lipid accumulation in HepaRG and HepG2 liver cancer cells by affecting carboxylesterase 2 (CES2) expression in a YTHDC2-dependent manner. Depletion of METTL3 and METTL14 increased CES2 expression and attenuated lipid accumulation, while knockout of FTO or ALKBH5 affected CES2 expression and lipid accumulation in a reversible manner [110]. Another study reported that METTL3 enhanced the expression of the lipogenesis-related lncRNA LINC00958 in HCC, and the latter promoted lipogenesis and tumour progression [111]. The m6A eraser FTO is a lipid metabolism-associated protein and has been proven to induce lipid droplet formation in esophageal cancer cells [112]. In addition, delta 4-desaturase sphingolipid (DEGS2) dysregulation in CRC mediated by m6A methylation induces lipid dysregulation and CRC carcinogenesis [113]. Ferroptosis-associated lipid peroxidation in tumours and immune cells modulates anti-tumour immunity and is a pivotal mechanism of immune evasion that has been investigated in recent years [160–162]. Studies have shown that m6A methylation regulates lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis through the ferroptosis defence system Xc−, comprising 2 subunits, SLC7A11 and SLC3A4, and a key enzyme of lipid metabolism, ACSL4, which induces ferroptosis in tumours. In GBM, m6A binds to NF-κB activating protein (NKAP) to stimulate SLC7A11 splicing and maturation, inhibiting cancer cell ferroptosis, and m6A methylation suppression or METTL3 deletion disrupts the ferroptosis-suppressing effect. NKAP also alters the TIME in GBM and affects lipid peroxidation in T cells [114]. That study implied the potential connection between m6A, lipid metabolism, and tumour immunity. m6A methylation-repressed tumour ferroptosis also depends on the inhibition of SLC7A11 deadenylation and enhancement of SLC7A11 stabilization [115, 116]. Notably, FTO-induced hypomethylation drives the downregulation of SLC7A11 expression, promoting tumour ferroptosis [117]. METTL14 inhibits SLC7A11 expression through YTHDF2-mediated degradation, which can be abrogated by hypoxia [118]. Additionally, YTHDC2 serves as an endogenous ferroptosis inducer due to its inhibition of SLC3A2 [119]. A systematic analysis identified that YTHDF2 interacts with the hypoxia-induced lncRNA-CBSLR to mediate the instability of CBS mRNA, decreasing ACSL4 methylation and leading to the protection of GC cells from ferroptosis and chemoresistance [120]. These data lay a solid foundation for the identification of indispensable m6A regulators in tumour immunity. Nevertheless, more convincing data are needed to identify the direct link between m6A-regulated lipid metabolic reprogramming in the TIME and immune evasion.

AA metabolism

AAs provide essential substances for cancer cell proliferation and regulation of the immune system. Aberrant metabolism of AAs affects anti-tumour immunity and facilitates tumour immune evasion [163]. Methionine is an essential AA, and dietary methionine deficiency suppresses tumour growth [164]. In the TIME, tumour cells restrict anti-tumour immunity through the disruption of methionine metabolism in T cells. It has been revealed that the augmentation of the tumour methionine transporter SLC43A2 disrupts T-cell acquisition of methionine, alters histone methylation, and decreases STAT5 expression, disrupting the cytotoxicity of T cells [165]. Additionally, increased levels of the methionine metabolites 5-methylthioadenosine (MTA) and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) promote T-cell exhaustion [166]. These published data highlight a critical role of methionine metabolism in reshaping the TIME and tumour immunity. Similarly, several AAs also regulate the plasticity of the TIME and affect tumour immune evasion in a metabolic manner. Glutamine catabolism promotes M2 macrophage activation with the epigenetic control of M2 genes [167]. Glutamine-addicted tumour cells induce IL-23 secretion by TAMs and subsequently drive Treg expansion and tumour-killing lymphocyte suppression, therefore facilitating tumour escape from immune surveillance [168]. Additionally, glutamine metabolism is closely associated with PD-L1 expression. Glutamine deprivation in tumours augments PD-L1 expression, which returns to normal after glutamine recovery [169]. Recent studies have highlighted the promising efficacy of targeting glutamine metabolism in cancer immunotherapy [170]. By using an antagonist of glutamine metabolism, researchers found that tumour glutamine restriction restrains the generation and enrichment of MDSCs in the TIME [171]. Another convincing study revealed that blockade of tumour glutamine metabolism by a glutamine metabolism inhibitor abolished the immunosuppressive TIME, alleviated hypoxia, acidosis, and nutrient deprivation, and restored anti-tumour immunity [172]. Arginine and tryptophan are indispensable for T-cell function, and their metabolism results in AA depletion and metabolite accumulation to inhibit the immune responses of T cells and facilitate tumour immune evasion [163]. In the TIME, TAMs, MDSCs, tolerogenic DCs, and Tregs restrain the arginine accessibility of T cells by expressing high levels of Arg I and arginine transporters. The nitric oxide generated by Arg consumption impairs T cell proliferation and activation. Tryptophan degradation by IDO1/TDO1 leads to Trp deficiency in T cells and thereby blocks the T-cell cycle. The major metabolite from Trp catabolism, kynurenine (Kyn), activates AHR, driving Treg differentiation and suppressing anti-tumour immunity [173]. Targeting AA metabolism in immunotherapy has been increasingly investigated at the preclinical and clinical stages in recent years, yet most studies have failed to show efficacy [174, 175]. The interplay between tumours and immune cells through metabolic regulators contributes to the heterogeneity of the TIME, and the intricate mechanisms by which metabolic players reshape the TIME and regulate tumour immune evasion need to be further clarified.

m6A methylation has been found to be a critical mechanism in AA metabolism [121]. Numerous studies have revealed a role of m6A-mediated AA metabolic reprogramming in cancer progression and chemoresistance. Glutaminolysis blockade enhanced FTO expression and disrupted YTHDF2-mediated RNA decay of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), stimulating autophagy activation and compromising anti-tumour efficacy [121]. FTO contributes to the loss of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumour suppressor in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Instead of acting in a manner dependent on the HIF-induced proangiogenic effect, FTO targets the glutamine transporter SLC1A5, modulating metabolic reprogramming and maintaining the survival of VHL-deficient tumour cells [122]. High expression of YTHDF1 in human colon tumour cells causes cisplatin resistance through the enhancement of glutaminase synthesis, and inhibition of glutaminase synergizes with the tumour-suppressing effect of cisplatin [123]. YTHDF1-driven chemoresistance provides a novel strategy to improve clinical chemotherapy. As mentioned previously, methionine metabolism has a direct link with m6A methylation; it produces SAM and provides the methyl group for methylation. Methionine regulates the TIME and mediates tumour evasion [165, 166]. Although increasing amounts of relevant data are being reported, there is limited evidence to show the role of m6A-modulated AA metabolism in the TIME and immune evasion. A recently published study revealed a novel role of m6A methylation-regulated methionine metabolic reprogramming in anti-tumour immunity and tumour immune evasion. Methionine metabolism promotes the m6A methylation of immune checkpoints, including PD-L1 and V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), enhancing their expression through YTHDF1. Dietary restriction of methionine or YTHDF1 depletion restores the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells and enhances the efficacy of PD-1 blockade [124]. This new discovery provides a novel strategy for cancer immunotherapy.

m6A methylation drives an acidic TIME and immune evasion

Lactate acid (LA) is a major metabolite in the TIME, and the augmentation of glycolytic activity in tumour cells induces the accumulation of LA, leading to an acidic TIME. LA serves as a ‘metabolic checkpoint’ that hinders the function of immune cells, triggering a hostile, immunosuppressive TIME and leading to immune evasion [176]. The high content of LA in the TIME impairs the proliferation and activation of T cells and NK cells and impedes the antigen presentation of DCs through the activated LA receptor GPR81 [177, 178]. Additionally, high LA content stimulates M2 macrophage, MDSC, and Treg infiltration [179, 180]. Recently, LA was proven to stimulate Treg expression of PD-1 in the highly glycolytic TIME and control immune responses, resulting in the disruption of PD-1 blockade, and inhibition of LA metabolism in Tregs overcame the resistance of Myc-overexpressing tumour cells to PD-1 blockade [181]. Lactate production is closely linked with m6A modification, m6A-regulated glycolysis affects the lactate content directly, and modulation of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is involved in the process. Recent studies have investigated the role of m6A in the lactate-driven TIME and immune evasion. It has been found that ALKBH5 targets the transcript of the lactate acid reporter Mct4 in tumours to elevate mRNA levels, enhancing extracellular lactate concentrations and the recruitment of Tregs and MDSCs in the TIME. ALKBH5 silencing or the use of ALKBH5 inhibitors in tumours improves immunotherapy efficacy [125], implying that ALKBH5 is a promising target for immunotherapy in melanoma, CRC, and perhaps other cancers. Interestingly, in a lactate-enriched TIME, lactylation drove METTL3 upregulation in tumour-infiltrating myeloid (TIM) cells and enhanced the immunosuppressive function of TIM cells through YTHDF1-mediated Jak1 translation and the subsequent phosphorylation of STAT3 [126]. These data reveal the interplay between epigenetic reprogramming and metabolites in the TIME, and further studies are needed to discover novel insights for the development of future immunotherapies.

m6A regulates the immunosuppressive TIME and immune evasion

A highly immunosuppressive TIME is a major feature of almost all tumours [182]. In addition to the m6A-contamniated hypoxia and acidity that induce an immunosuppressive TIME, the elevated levels of immune inhibitory molecules and the enrichment of immune suppressor cells in the TIME facilitated by m6A methylation hinder tumour-specific immune responses and assist immune evasion [183, 184]. PD-L1 is the primary negative immune regulatory molecule in tumour cells; it is also found in immune cells and has been widely targeted in immunotherapy for its ability to suppress T cells and its contribution to immune evasion [185]. Emerging evidence has revealed that m6A regulators modulate PD-L1 expression in numerous tumours, leading to an immunosuppressive TIME and immune escape. METTL3 is upregulated in many types of tumour cells. Consistent with its protumoral role, METTL3 enhances tumour PD-L1 expression based on previous studies. METTL3-mediated m6A decoration is essential for promoting tumour PD-L1 expression through IGF2BP1-enhanced RNA stability in bladder cancer, and the activation of JNK signalling augments METTL3 expression [127]. In breast cancer, the METTL3/IGF2BP3 axis inhibits immune surveillance by activating PD-L1 mRNA [128]. Additionally, the mechanisms by which METTL3 regulates PD-L1 expression and thus immune escape have also been investigated in non-small cell lung cancer. METTL3 promotes the circularization of circIGF2BP3 by YTHDC1, and the latter subsequently triggers the deubiquitination of PD-L1, elevating its level in lung cancer cells [129]. These results indicate that m6A methylation is a critical driver of PD-L1-induced immunosuppression in the TIME. As another principal component of the m6A writer complex that facilitates RNA binding, METTL14 has also been found to regulate m6A methylation-driven tumoral PD-L1 expression. The ubiquitination of PD-L1 in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is diminished by METTL14 through YTHDF2-mediated inhibition of the RING E3 ubiquitin ligase Siah2, and the deprivation of Siah2 represses T-cell expansion and toxicity by maintaining tumour PD-L1 expression [130]. Peng et al. illustrated that METTL14 facilitates LPS-induced PD-L1 expression in HCC cells, METTL14 upregulation by LPS strengthens the stability of MIR155HG and further regulates the levels of PD-L1 via the miR-223/STAT1 axis [131]. The study revealed the epigenetic mechanism by which LPS promotes PD-L1 expression and immune escape. Since m6A modification is reversible, which enables it to precisely regulate tumour processes, the regulatory effect of m6A erasers on immune inhibitory molecules has been investigated. In intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), ALKBH5 interacts with tumour PD-L1 to remove m6A deposition in the 3’UTR of PD-L1 mRNA, therefore preventing YTHDF2-mediated RNA decay and sustaining PD-L1 expression, which represses the proliferation of cytotoxic T cells [132]. That study also revealed the complicated TIME-regulating role of ALKBH5 by single-cell mass cytometry analysis. ALKBH5 enhances PD-L1 levels in monocytes/macrophages and attenuates the infiltration of MDSCs. Specimen analysis further confirmed that tumours with high levels of ALKBH5 were more sensitive to anti-PD1 therapy. Recently, a novel mechanism by which ALKBH5 drives an immune-inhibitory TIME was revealed by Jin et al. ALKBH5 overexpression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma hindered RIG-1-mediated IFNα secretion, decreasing tumour-killing immune cell infiltration in the TIME and exerting a tumour-promoting effect [133]. Furthermore, the m6A reading protein HNRNPC was identified to mediate the maturation of DDX58, which encodes RIG-1. FTO dysregulation was recently reported to affect the expression of tumour-derived immunosuppressive molecules. FTO overexpression induced by the hypomethylating agent decitabine in AML cells markedly increased the expression of the critical immune checkpoint protein LILRB4, which is 40-50 times more abundant than endogenous PD-L1 and PD-L2 in AML cell lines. FTO inhibition significantly decreased leukaemia stem cell self-renewal by abolishing the increase in LILRB4 expression and sensitized human AML cells to T-cell cytotoxicity. In vivo analysis further confirmed that targeting FTO/m6A/LILRB4 overcomes immune evasion in leukaemia [134]. In melanoma, knockdown of FTO promotes YTHDF2-mediated PD-1, CXCR4, and SOX10 mRNA decay, sensitizing melanoma cells to interferon-gamma and anti-PD-1 therapy [135]. The immune-inhibitory role of FTO has also been confirmed in oral cancer. FTO upregulation in arecoline-exposed oral cancer enhanced PD-L1 transcript levels and stability through m6A modification and MYC activity [136]. These compelling results reveal that tumours exploit m6A methylation and demethylation to promote an immunosuppressive TIME and facilitate escape from immune surveillance. An understanding of the mechanism by which m6A regulates PD-L1 expression and promotes an immunosuppressive TIME will provide novel insights to overcome the clinical challenges of immunotherapy.

Enrichment of immune-suppressing cells, including MDSCs, Tregs, and TAMs, and increases in the levels of immune inhibitory cytokines secreted by these immune cells in the TIME exert an inhibitory effect on tumour-killing immune cells, sustaining the immune-hostile TIME and promoting tumorigenesis [186]. m6A modification has been closely linked with suppression of immune infiltration in various tumours. Comprehensive analyses of public datasets have led to the characterization of tumour immune infiltration signatures based on m6A modification patterns [187], revealing a critical role of m6A methylation in reshaping the TIME and regulating immune evasion. Recent studies have convincingly confirmed that m6A potentiates theimmunosuppressive TIME and immune escape through the augmentation of immune inhibitory cells. METTL3 in CRC cells enhances the migration of MDSCs and subsequently inhibits CD8+ T cells by increasing CXCR1 transcription through m6A-induced upregulation of BHLHE41 expression. METTL3-driven immune repression can be reversed by MDSC depletion. METTL3 silencing or pharmacological inhibition improves the efficacy of PD-1 blockade [137]. Notably, m6A-regulated IFN responses in GBM reduce Treg infiltration and strengthen the efficacy of ICB by targeting transcription elongation machinery [138], revealing a novel mechanism by which m6A regulates the immune-suppressive TIME and the molecular basis of therapy resistance in GBM. The ALKBH5/MAP3K8 axis has been identified to induce PD-L1+ macrophage enrichment in HCC, promoting HCC progression and an immunosuppressive TIME [139] (Table 1).

m6A methylation is undoubtedly a modulating program that can reshape the TIME under hypoxic stress, as well as by regulating acidity and metabolic reprogramming and altering the immune infiltration of suppressive immune cells and immune checkpoint expression. As a delicate mechanism controlling the above processes in the TIME, m6A methylation is beginning to be recognized as a promising target and prognostic marker for improving immunotherapy.

The m6A methylation programme in immune cells

Immune cells are the primary agents that defend and kill tumour cells. However, impaired activation, expansion, and phenotype switching of immune cells can induce an immune-exhausted and suppressive TIME, leading to tumour evasion [188]. Evidence has shown that m6A RNA modification in immune cells is indispensable in the regulation of the homeostasis and function of multiple tumour-infiltrating immune cells, reshaping anti-tumour immunity and modulating immune evasion.

m6A methylation is required for T cell homeostasis and functions

T-cell responses are predominant in anti-tumour immunity, and most cancer immunotherapies and strategies to combat immune evasion are focused on reprogramming T cells [189]. Naïve T cells, possessing stem cell-like ability, undergo expansion and differentiate into distinct effector T cells under the effect of cytokines and associated signalling pathways in the microenvironment [190]. With neoantigen stimulation and activation signals, naïve CD4+ T cells differentiate into T helper cells to assist and regulate the immune responses of CD8+ T cells and B cell activation, while naïve CD8+ T cells differentiate into tumour-killing T cells or cytotoxic T cells (CTLs). Apoptosis occurs for most effector T cells, although a few survive and turn into memory T cells. Unstimulated naïve T cells are in a resting state and can be recycled. These processes, including the proliferation and differentiation of naïve T cells, TCR signalling, and T-cell apoptosis, are critical for T-cell homeostasis and tumour-specific adaptive immunity.

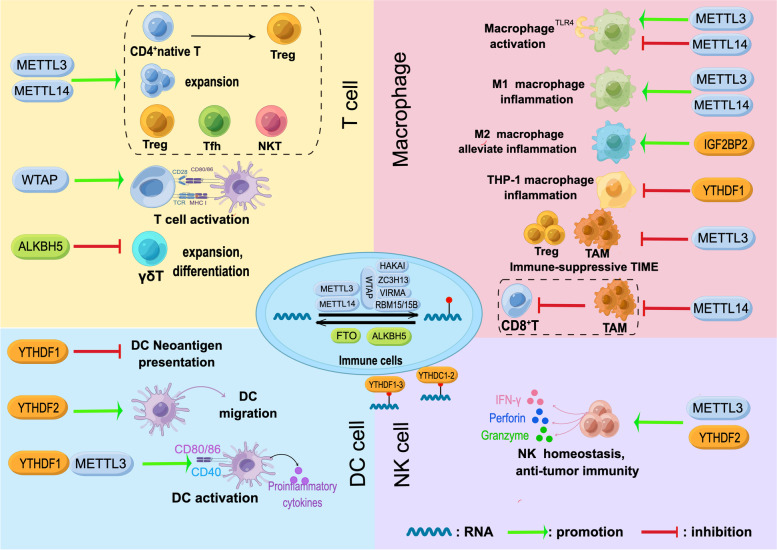

Increasing evidence has revealed an indispensable role of m6A methylation in T-cell homeostasis owing to its regulation of cellular RNA dynamics by affecting the splicing, translation, and degradation of transcripts. The specific mechanism has been investigated in various T cells. Li et al. first reported that m6A methylation is critical for the differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells in 2017. Researchers have found that m6A methylation is responsible for inducing the RNA decay of SOCS1/3 and CISH in conditional METTL3 and METTL14 knockout mice, safeguarding IL-7/STAT5-mediated T-cell expansion and differentiation [191]. Based on these findings, the team further revealed that METTL3-driven m6A methylation is required to maintain Treg suppressive function because it induces an inhibitory effect of SOCS on IL-2/STAT5 signalling [192]. A recent study demonstrated that METTL14 deficiency in T cells was associated with reduced METTL3 abundance, resulting in the failure of naïve T cells transitioning into Tregs and promotion of the Th1/Th17 phenotype [193]. WTAP-driven m6A methylation has been proven to modulate TCR signal transduction and control T-cell activation as well as survival [194]. As specialized CD4+ effector T cells, T follicular helper (Tfh) cells contribute to antitumour immunity and control PD-L1 blockade efficacy [195, 196]. Evidence has shown that METTL3-induced m6A methylation stabilizes the transcripts of predominant Tfh cell signature genes to promote cell differentiation [197]. In addition, m6A methylation also participates in VHL-enhanced early-stage Tfh cell differentiation in a glycolytic-epigenetic manner [198]. One recent study focused on the role of m6A in the development and function of unconventional T cells. METTL14 deficiency in T cells induced a distinct reduction in invariant NKT (iNKT) cell numbers due to decreased TCR rearrangement. In iNKT cells, loss of METTL14 promoted cell apoptosis, jeopardized cell maturation, and weakened the responses to IL-2/IL-15 TCR stimulation. Impaired cytokine production and TCR signalling are found in mature NKT cells after METTL14 knockdown [199]. γδT cells, another unconventional T lymphocyte, are distributed widely in mucous and provide vital immune surveillance in some tumours due to their non-MHC-restricted antigen recognition [75, 200]. A recent study discovered that deletion of the m6A demethylase ALKBH5 in lymphocytes enhances γδT-cell expansion. Mechanistically, increased m6A levels in thymocytes reduce the transcript abundance of target genes in Notch signalling, contributing to the augment of γδT cell proliferation and differentiation [201] (Fig. 3). These studies revealed that m6A methylation is a critical mechanism of dynamic regulation in T-cell development, differentiation, and antitumour immune responses.

Fig. 3.

m6A modulation in immune cells. m6A methylation regulates T-cell homeostasis, macrophage reprogramming (plasticity), and the functions of DCs and NK cells

m6A methylation modulates multiple DC immune responses

DCs are the initiators of adaptive immune responses. Unlike other antigen-presenting cells, DCs possess the strongest ability to present antigens that can activate naïve T cells [202], triggering the first anti-tumour immune responses. The dysfunction of DCs leads to immune escape and aggravates carcinogenesis [203]. DCs have been a common topic of immunotherapy in recent years [204]. Recent evidence has shown that m6A methylation regulates multiple processes in DC-steered tumour-specific immune responses. m6A modification and YTHDF1 regulate the neoantigen presentation of DCs by enhancing the levels of transcripts from lysosome proteases, which increases the expression of neoantigen-disrupting lysosomal cathepsins in DCs. This subsequently results in impaired T-cell activation. The augmentation of antigen cross-presentation and a boost of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell antitumour responses were observed by YTHDF1 depletion in DCs. In addition, YTHDF1-knockout mice exhibited improved PD-1 blockade therapy efficacy [205]. m6A modification affects DC migration to draining lymph nodes controlled by CCR7 by altering the metabolic patterns of DCs. By removing m6A from the long non-coding RNA lnc-Dpf3 in DCs, CCR7 protects lnc-Dpf3 from YTHDF2-mediated degradation, and this augmentation of lnc-Dpf3 inhibits HIF-1α-driven glycolysis and hinders DC migration [206]. The data provide novel evidence that M6A methylation regulates immune homeostasis and metabolic reprogramming. m6A methylation also promotes DC activation and maturation. METTL3-mediated methylation and YTHDF1 recognition enhance the expression of the costimulatory molecules CD40, CD80, and CD86 in DCs, as well as the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α [207] (Fig. 3). These findings highlight that m6A methylation serves as a critical mechanism regulating the immune responses and homeostasis of DCs.

m6A methylation orchestrates macrophage reprogramming (plasticity)

Macrophages play multiple roles in the host innate immune system and modulate T-cell immunity due to their high plasticity in different microenvironments [208]. Macrophages can be activated through TLR signalling, resulting in increased secretion of cytokines and elevated phagocytosis ability to eliminate infected cells. Macrophages can be switched and repolarized into the M1 and M2 phenotypes, displaying proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory effects. In the TIME, TAMs tend to sustain an immune-suppressive TIME by expressing inhibitory receptors such as PD-L1 and producing IL-10 and TGF-β, inducing T-cell exhaustion and immune escape [28]. With several studies revealing the heterogeneity of macrophages, reprogramming macrophages has been suggested as a novel strategy in immunotherapy. Recent evidence has revealed that m6A methylation orchestrates macrophage reprogramming and regulates the TIME. m6A methylation modulates dynamic macrophage activation. METTL3-driven methylation positively regulates macrophage activation by accelerating the decay of IRKAM transcripts suppressing TLR signalling [209]. METTL14 maintains the negative feedback control of TLR4/NF-κB signalling by inducing SOCS1 decay, preventing macrophage overactivation [210]. m6A methylation promotes macrophage polarization and regulates inflammation. METTL3 facilitates M1 macrophage polarization through m6A-mediated augmentation of STAT1 expression [211]. METTL14 deficiency induces M2 macrophage polarization and decreases Myd88 and IL-6 levels due to loss of m6A modification [212]. IGF2BP2 targets methylated TSC1 to induce macrophage polarization from the M1 to the M2 phenotype and alleviate inflammation [213]. YTHDF1-induced SOCS3 translation negatively controls inflammatory responses in bacteria-induced THP-1 macrophages [214]. m6A methylation regulates TAM reprogramming and immune surveillance. Specific METTL3 knockout in macrophages increases M1- and M2-like TAMs and promotes Treg enrichment into tumours, establishing an immune-suppressive TIME and limiting the efficacy of PD-1 blockade in melanoma. The loss of METTL3 impairs YTHDF1-mediated translation of SPRED2 and leads to the activation of NF-kB and STAT3 signalling through the ERK pathway, promoting M1 and M2 TAM activation and cytokine production [215]. Dong and his colleagues proved that METTL14 deletion in TAMs drives the dysfunction of CD8+ T cells. Their investigation revealed that C1q+ TAMs were specifically regulated by METTL14, and depletion of METTL14 in C1q+ TAMs promoted Ebi3 mRNA accumulation through the METTL14-YTHDF2 axis, resulting in a shift of intratumor CD8+ T cells towards a dysfunctional state [216] (Fig. 3). Regulation of m6A modification in TAMs is a novel mechanism of immune suppression and tumour immune evasion, suggesting m6A-reprogrammed macrophages as a potential target in immunotherapy. m6A methylation orchestrates macrophage reprogramming, reinforcing the critical role of epigenetic control in immune surveillance and inflammation-associated diseases.

m6A methylation sustains NK cell homeostasis and its tumoricidal effect

NK cells are a group of cytotoxic cells that play a critical role in immune surveillance [217]. Unlike T-cell activation, NK cell activation can be induced by multiple pathways independent of MHC-restricted antigens [69]. NK cells can directly recognize microbe-infected cells or cancerous cells and mediate a rapid killing effect by releasing perforins, granzyme B, and NK cell cytotoxic factors. Additionally, by producing the cytokines IFN-γ and TGF-β, NK cells can regulate adaptive immunity. Hence, harnessing NK cells is a critical strategy in cancer immunotherapy in addition to T-cell and DC cell-based therapies [218–220]. Recent evidence has revealed a regulatory role of m6A methylation in antitumour immunity and the functions of NK cells. METTL3-deficient NK cells exhibit aberrant infiltration in the TIME and disrupt NK cell homeostasis, hindering antitumour immunity [221]. YTHDF2 is essential in NK cell homeostasis, terminal maturation, and antitumour immunity [222]. YTHDF2 reduces the stability of Tardbp RNA, which contributes to IL-15-mediated NK cell proliferation and survival (Fig. 3).

Conclusions and perspectives

This review describes the m6A programme in the TIME and its modulation in immune evasion based on the primary features of the TIME, including hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, acidity, and immune suppression, and introduces m6A modulation in immune cells, highlighting that dynamic and reversible m6A methylation is a crucial mechanism reshaping the intricate TIME and regulating immune evasion. Based on extensive evidence, m6A methylation is altered under divergent stimuli, which further reshapes the TIME and regulates anti-tumour immunity. These phenomena suggest that m6A modulation is highly dependent on biological context, which was demonstrated by He et al. in 2019 [223]. In the hypoxic TIME, the enhancement or restriction of m6A regulators by HIF signalling affects tumour-derived RNA fate and subsequently triggers diverse effector functions, supporting a tumour-friendly environment. Notably, hypoxia defines a distinct tumour-regulatory role of ALKBH5 and FTO. Nutrient deprivation and acidity in the TIME also drive m6A modulation and affect immune surveillance. Methionine restriction directly results in decreased methylation of immune checkpoint transcripts for insufficient SAM, leading to the restored efficacy of immunotherapy. Lactylation of METTL3 boosts RNA binding ability and m6A methylation, enhancing immune-suppressive TIM cells. Although limited evidence has proven that m6A regulates lipid metabolism in tumour immunity, numerous clues suggest that future studies should attempt to link m6A modification, ferroptosis, and tumour immune surveillance.

m6A modulation is a precise modulation in a spatiotemporal manner [224]. m6A methylation participates in the specific stage of disease progression [225]; it also displays dynamic alterations in different stages of physiological or pathological processes. As previously discussed, YTHDF2 is essential for the terminal maturation of NK cells rather than functioning in the early stage. Comprehensive analysis revealed that the m6A modification pattern was closely related to tumour stage [226]. Hence, further research could consider illustrating the dynamic and reversible m6A modulation in different stages of tumour immune surveillance. A specific timepoint or dynamic changes in different stages should be considered to acquire unbiased and accurate results. Novel research tools, such as single-cell RNA sequencing, are preferred for application in m6A studies.

With vital roles of m6A methylation in tumours and immunoregulation, targeting m6A methylation to harness the TIME and overcome immune evasion has been a potential strategy to improve tumour therapy. However, there are also obstacles to the application of targeting m6A methylation in tumour therapy. As m6A methylation is abundant in diverse physiological and pathological processes, and m6A modulation is tissue- and/or cell-specific [227, 228]. Distinct m6A modification patterns have been demonstrated in diverse tumours, and there are unique m6A modulation patterns in tumour cells and immune cells, which exert distinct effects on immune evasion. These results suggest that specific cells or tissues may need to be targeted in m6A-based tumour therapy. Although no relevant clinical data are available yet, in vitro and in vivo attempts showed that developing small molecules that target m6A RNA modification proteins is an attractive strategy [125, 229–231]. One study provided solid data on efficacy and toxicity effects [230]. Catalytic inhibition of METTL3 by the small molecule STM2457 specifically inhibited key stem cell populations in AML and prolonged the mouse lifespan without overt toxicity to normal haematopoiesis. A target-based drug design combined with a cell-based screen is popular to develop bioactive small molecules with high selectivity for targets and sensitivity to cells. This step contains the structure optimization of the leading compounds through chemical approaches and pharmacology studies, including vigorous validation of the efficacy and toxicity in vitro and in vivo, selecting the optimum concentration of chemical agents with desired efficacy and lowest toxic effects. Additionally, nanomedicine could be further used to specifically deliver bioactive candidates to tumour cells or immune cells in the TIME [231]. The latest study introduced a nanoplatform that achieved the co-delivery of tumour-associated antigens and FTO inhibitors into tumour-infiltrating dendritic cells (DCs), promoting DC maturation and improving tumour-specific immune responses in vivo and in vitro. Targeting m6A methylation in tumour therapy are filled with challenges to overcome but bring hope for future therapy.

In conclusion, m6A methylation is an indispensable mechanism in tumour immunoregulation and immune evasion. Targeting m6A methylation is a promising strategy to overcome immune escape. We hope this review provides novel insights into m6A modulation in immunotherapy and further investigation. However, there is a limitation: our review separately introduced the m6A methylation-reshaped TIME under individual stimuli and lacked crosstalk among hypoxia, metabolic reprogramming, acidity, and immunosuppression in the TIME. Further research is expected to provide more in-depth evidence on m6A methylation-modulated diseases and therapy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Figdraw (www.figdraw.com) for expert assistance in the pattern drawing.

Abbreviations

- m6A

N6-methyladenosine

- TIME

Tumour immune microenvironment

- METTL3

Methyltransferase-like 3

- METTL14

Methyltransferase-like 14

- WTAP

William tumour 1-associated protein

- RBM15

RNA binding motif protein 15

- ZC3H13

Zinc-finger CCCH domain-containing protein 13

- VIRMA

Vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated

- TAM

Tumour-associated macrophages

- Treg

Regulatory T cell

- FTO

Fat-mass and obesity-associated protein

- ALKBH5

Alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase ALKB homologue 5

- RBPs

RNA-binding proteins

- IGF2BP

Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins

- HIFs

Hypoxia-inducible factors

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- MDSCs

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- BCSCs

Breast cancer stem cells

- ECSCs

Endometrial cancer stem-like cells

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- MTA1

Metastasis-associated protein 1

- AML

Acute myeloid leukaemia

- LUSC

Lung squamous carcinogenesis

- SERPINE2

Serpin family E member 2

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- AA

Amino acid

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- NK cells

Natural killer cells

- ICBs

Immune checkpoint blockades

- RCC

Renal cell carcinoma

- GC

Gastric cancer

- CK2

Casein kinase 2

- BCa

Bladder cancer

- FAO

Fatty acid oxidation

- Teffs

Tumour-killing T effector cells

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid

- HETEs

Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids

- CES2

Carboxylesterase 2

- DEGS2

Delta 4-desaturase sphingolipid

- NKAP

NF-κB activating protein

- MTA

Methylthioadenosine

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- Kyn

Kynurenine

- ATF4

Activating transcription factor 4

- VHL

Von Hippel–Lindau

- ccRCC

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- VISTA

V-domain Ig suppressor of T-cell activation

- LA

Lactate acid

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- TIM cells

Tumour-infiltrating myeloid cells

- CCA

Cholangiocarcinoma

- ICC

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- PUFA

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- CTLs

Cytotoxic T cells

- Tfh cells

T follicular helper cells

- iNKT cell

Invariant NKT cell

Authors’ contributions

Xiaoxue Cao wrote the manuscript. Cheng Xiao and Liqun Jia conceived the review. Qishun Geng, Danping Fan, Qiong Wang, Xing Wang, Tingting Deng participated in discussions associated with the manuscript. Mengxiao Zhang, Lu Zhao, Yi Jiao, Honglin Liu, Jing Zhou revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number: U22A20374, 82173378).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors give consent for the publication of the manuscript in Molecular Cancer.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no potential competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiaoxue Cao, Email: snow2018cxx@163.com.

Qishun Geng, Email: gqs630862@163.com.

Danping Fan, Email: zgzyfdp@126.com.

Qiong Wang, Email: 625841538@qq.com.

Xing Wang, Email: 13605600939@163.com.

Mengxiao Zhang, Email: 1758427366@qq.com.

Lu Zhao, Email: meetzhaolu@163.com.

Yi Jiao, Email: 631492342@qq.com.

Tingting Deng, Email: ttdeng1983@163.com.

Honglin Liu, Email: honglinl2003@163.com.

Jing Zhou, Email: gardenia_zhou@hotmail.com.

Liqun Jia, Email: liqun-jia@hotmail.com.

Cheng Xiao, Email: xc2002812@126.com.

References

- 1.Fu T, Dai LJ, Wu SY, Xiao Y, Ma D, Jiang YZ, Shao ZM. Spatial architecture of the immune microenvironment orchestrates tumor immunity and therapeutic response. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:98. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Song J, Zhao Z, Yang M, Chen M, Liu C, Ji J, Zhu D. Single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals tumor immune microenvironment heterogenicity and granulocytes enrichment in colorectal cancer liver metastases. Cancer Lett. 2020;470:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duan Q, Zhang H, Zheng J, Zhang L. Turning cold into hot: firing up the tumor microenvironment. Trends Cancer. 2020;6:605–618. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao Y, Ma D, Zhao S, Suo C, Shi J, Xue MZ, Ruan M, Wang H, Zhao J, Li Q, et al. Multi-omics profiling reveals distinct microenvironment characterization and suggests immune escape mechanisms of triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:5002–5014. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun YF, Wu L, Liu SP, Jiang MM, Hu B, Zhou KQ, Guo W, Xu Y, Zhong Y, Zhou XR, et al. Dissecting spatial heterogeneity and the immune-evasion mechanism of CTCs by single-cell RNA-seq in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2021;12:4091. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24386-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitt JM, Marabelle A, Eggermont A, Soria JC, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and immunotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1482–1492. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lan Y, Moustafa M, Knoll M, Xu C, Furkel J, Lazorchak A, Yeung TL, Hasheminasab SM, Jenkins MH, Meister S, et al. Simultaneous targeting of TGF-β/PD-L1 synergizes with radiotherapy by reprogramming the tumor microenvironment to overcome immune evasion. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1388–1403.e1310. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gangoso E, Southgate B, Bradley L, Rus S, Galvez-Cancino F, McGivern N, Güç E, Kapourani CA, Byron A, Ferguson KM, et al. Glioblastomas acquire myeloid-affiliated transcriptional programs via epigenetic immunoediting to elicit immune evasion. Cell. 2021;184:2454–2470.e2426. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topper MJ, Vaz M, Marrone KA, Brahmer JR, Baylin SB. The emerging role of epigenetic therapeutics in immuno-oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17:75–90. doi: 10.1038/s41571-019-0266-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez S, Tabernacki T, Kobyra J, Roberts P, Chiappinelli KB. Combining epigenetic and immune therapy to overcome cancer resistance. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;65:99–113. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung H, Kim HS, Kim JY, Sun JM, Ahn JS, Ahn MJ, Park K, Esteller M, Lee SH, Choi JK. DNA methylation loss promotes immune evasion of tumours with high mutation and copy number load. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4278. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12159-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Yao J, Bao R, Dong Y, Zhang T, Du Y, Wang G, Ni D, Xun Z, Niu X, et al. Cross-talk of four types of RNA modification writers defines tumor microenvironment and pharmacogenomic landscape in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:29. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01322-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Hao Y, Zhang X, Xu S, Pang D. Targeting RNA N(6)-methyladenosine modification: a precise weapon in overcoming tumor immune escape. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:176. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01652-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbieri I, Kouzarides T. Role of RNA modifications in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20:303–322. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Dominissini D, Rechavi G. The epitranscriptome toolbox. Cell. 2022;185:764–776. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulias K, Greer EL. Biological roles of adenine methylation in RNA. Nat Rev Genet. 2022. 10.1038/s41576-022-00534-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Dorn LE, Lasman L, Chen J, Xu X, Hund TJ, Medvedovic M, Hanna JH, van Berlo JH, Accornero F. The N(6)-Methyladenosine mRNA methylase METTL3 controls cardiac homeostasis and hypertrophy. Circulation. 2019;139:533–545. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu W, Li J, He C, Wen J, Ma H, Rong B, Diao J, Wang L, Wang J, Wu F, et al. METTL3 regulates heterochromatin in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2021;591:317–321. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramalingam H, Kashyap S, Cobo-Stark P, Flaten A, Chang CM, Hajarnis S, Hein KZ, Lika J, Warner GM, Espindola-Netto JM, et al. A methionine-Mettl3-N(6)-methyladenosine axis promotes polycystic kidney disease. Cell Metab. 2021;33:1234–1247.e1237. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen S, Zhang R, Jiang Y, Li Y, Lin L, Liu Z, Zhao Y, Shen H, Hu Z, Wei Y, Chen F. Comprehensive analyses of m6A regulators and interactive coding and non-coding RNAs across 32 cancer types. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:67. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01362-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L, Wu Y, Li Q, Liang J, He Q, Zhao L, Chen J, Cheng M, Huang Z, Ren H, et al. METTL3 promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis through BMI1 m(6)A methylation in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Ther. 2020;28:2177–2190. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu P, Fang X, Liu Y, Tang Y, Wang W, Li X, Fan Y. N6-methyladenosine modification of circCUX1 confers radioresistance of hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma through caspase1 pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:298. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03558-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Kang M, Zhang B, Meng F, Song J, Kaneko H, Shimamoto F, Tang B. m(6)A modification-mediated CBX8 induction regulates stemness and chemosensitivity of colon cancer via upregulation of LGR5. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:185. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Zhang B, Wu Q, Li B, Wang D, Wang L, Zhou YL. m(6)A regulator-mediated methylation modification patterns and tumor microenvironment infiltration characterization in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:53. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-01170-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chong W, Shang L, Liu J, Fang Z, Du F, Wu H, Liu Y, Wang Z, Chen Y, Jia S, et al. m(6)A regulator-based methylation modification patterns characterized by distinct tumor microenvironment immune profiles in colon cancer. Theranostics. 2021;11:2201–2217. doi: 10.7150/thno.52717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li M, Zha X, Wang S. The role of N6-methyladenosine mRNA in the tumor microenvironment. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021;1875:188522. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Ma S, Deng Y, Yi P, Yu J. Targeting the RNA m(6)A modification for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:76. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu Y, Wu X, Zhang J, Fang Y, Pan Y, Shu Y, Ma P. The evolving landscape of N(6)-methyladenosine modification in the tumor microenvironment. Mol Ther. 2021;29:1703–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B, Jiang J, Assaraf YG, Xiao H, Chen ZS, Huang C. Surmounting cancer drug resistance: new insights from the perspective of N(6)-methyladenosine RNA modification. Drug Resist Updat. 2020;53:100720. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2020.100720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, He C. Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18:31–42. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaccara S, Ries RJ, Jaffrey SR. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:608–624. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixit D, Prager BC, Gimple RC, Poh HX, Wang Y, Wu Q, Qiu Z, Kidwell RL, Kim LJY, Xie Q, et al. The RNA m6A reader YTHDF2 maintains oncogene expression and is a targetable dependency in glioblastoma stem cells. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:480–499. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang X, Zhang S, He C, Xue P, Zhang L, He Z, Zang L, Feng B, Sun J, Zheng M. METTL14 suppresses proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer by down-regulating oncogenic long non-coding RNA XIST. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:46. doi: 10.1186/s12943-020-1146-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]