Abstract

Background

The upper lip area is an important component of facial aesthetics, and aging produces an increase in the vertical height of the upper lip. Different upper lip lifting techniques are described in the literature.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to assess both invasive and noninvasive upper lip lifting techniques with patient satisfaction, adverse effects, and quantitative measurements of lifting efficiency.

Methods

This study was conducted per PRISMA guidelines. MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE (OvidSP), and Cochrane Library database were searched from September 14, 2022, to October 12, 2022. Inclusion criteria were reporting on upper lip lift efficiency with quantitative measurements of the lifting degree.

Results

Out of 495 studies through the search strategy, nine articles were included in the systematic review, eight for surgical procedures and one for nonsurgical. Surgical procedures seem to have better longevity than nonsurgical techniques. Reported patient satisfaction for both surgical and nonsurgical treatments was good with no severe complaints. The quantitative measures differ between researches and may be classified into two metrics: anatomy ratio computation using photographic analysis or direct height measurement with a caliper and precise parameters utilizing a three-dimensional method.

Conclusion

In general, surgical therapies seem to have a longer-lasting lifting effect on upper lip lifts with an inevitable scar, while nonsurgical techniques are minimally invasive but temporary. There was a lack of consistency in the measurements used to assess lifting efficiency. A consistent quantitative assessment can be beneficial for both clinical decision-making and high-level evidence research.

Level of Evidence III

This journal requires that authors assign a level of evidence to each article. For a full description of these Evidence-Based Medicine ratings, please refer to the Table of Contents or the online Instructions to Authors www.springer.com/00266.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00266-023-03302-5.

Introduction

The perioral region is significant in conveying one’s age, contributing to facial attractiveness and beauty [1–5], and is gaining more interest during the COVID-19 pandemic [6]. A youthful and attractive perioral region consists of a relatively shorter upper lip with soft tissue projection [7, 8] whereas the most significant senile alterations are upper lip lengthening and shape deformities [9]. Furthermore, these aging traits might occur on the lips of younger people due to hereditary [10, 11], who may seek to change their appearance [12].

Detailed explanations of anatomy and function in connection to aging and upper lip lengthening have been frequently referenced [13–18]. The upper cutaneous lip, also known as the ergotrid, is a trapezoidal region defined by the upper vermilion border caudally, the nasal base cephalad, and the nasolabial folds bilaterally [19]. Gravity causes the upper lip to droop downward as a person ages, resulting in an increased vertical height of the lip, flatting of the philtrum, inversion of Cupid’s bow, thinning of the vermilion, and covering of the teeth [20]. Actually, the upper lip is the only anatomical landmark in the centrofacial area that sags, while all other anatomical landmarks remain in the same position [2, 21, 22]. Thus, reducing the height from the nose to the vermilion border of the upper lip can help restore a pleasant and youthful appearance [23], and the impact of lip lift may be the highest on younger-aged patients (35 years) [24].

Various techniques to lift the upper lip have been described in the literature, which may consist of injecting fillers [25] and lip lift surgical techniques [26], such as simple subnasal skin excision, subnostril skin excision, or even vermilion advancement [27, 28]. Filler materials were first used to restore lip architecture and volume loss in the 1990s [29, 30], whereas surgical interventions to lift upper lips began in the early 1970s, with a large series of cases reported ten years later [20, 31]. Different excisions and more methods with fewer scars have gained interest from then on [32]. Typically, some studies believe that injectable fillers do not produce long-term results due to a lack of permanent fillers [33] while others think fillers injected into the upper lip can produce clinical effects equivalent to surgical lip lift operations [25, 34]. However, it remains unclear whether they have the same effects, and there is a lack of precise measurement evidence.

Furthermore, a study discovered that the average decrease in philtrum length is not proportional to the quantity of tissue removed. The lift of the upper lip was greater than the amount of tissue excised [8]. Thus, a quantitative measurement to evaluate the changes to the upper lip after excision and closure is necessary. Some studies have mentioned that laser [35] and facial serum injections [36] can also shorten the upper lip, although the precise efficacy of these treatments cannot be confirmed due to the lack of quantitative evaluation. Even in research with objective measurement data, measuring procedures are not consistent [8, 29]. The lack of uniformity in outcome reporting limited the evidence level to a higher one [37], as Hassouneh et al stated that inconsistency in result reporting was a significant impediment to the development of effective systematic reviews and meta-analyses comparing multiple surgical interventions in facial plastic surgery [38]. The standardization of outcomes and outcome measurements can help to restrict incorrect outcomes, avoid reporting bias, and facilitate data pooling in meta-analyses [39].

Although Yamin et al [40] presented an overview of surgical upper lip lifting methods in a recent systematic review, this study did not analyze outcome metrics. Therefore, the aim of this study was to systematically assess both invasive and noninvasive upper lip lifting techniques documented in the literature, while also taking into account patient satisfaction, adverse effects, and, most importantly, quantitative measurements of the lifting efficiency. A quantitative measure method may help assist the surgeon in developing better preoperative designs to achieve a desirable result, such as the exact quantity of tissue removed, and monitoring the durability of the postoperative outcomes. Furthermore, quantifiable measurements allow investigators to reliably compare the results of various upper lip lifting treatments and will aid future high-level evidence summaries in the form of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was carried out in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [41]. A population, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) framework was used to guide the search strategy [42]. This study was not registered.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included when at least one surgical or nonsurgical procedure was used to lift the upper lip, or when there was a reference to the effect of upper lip lift. Studies were excluded when objective measurements of the upper lip were not mentioned or in the case of cleft lip and palate reconstruction. Studies that focused on orthodontic or maxillary procedures or post-traumatic or post-oncologic reconstructions were also excluded. Included studies were limited to the English language and full text available. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Clinical trials | Reviews |

| Comparative studies | Letters to editor |

| Case reports | No full text available |

| Full text available | Non-English languages |

| Nonsurgical technique(s) to lift the upper lip | No attention to an effect of the upper lip lift nor quantified patient satisfaction |

| Surgical technique(s) to lift the upper lip | Post-traumatic or post-oncologic reconstruction of the upper lip |

| Combination of surgical and nonsurgical technique(s) to lift the upper lip | Orthodontic or maxillary surgical procedures |

| Reference to the effect of upper lip lift in title or abstract | Reconstruction of cleft lip and palate patients (UCLP). |

| No objective measurements of the upper lip lift. |

Search Strategy

MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE (OvidSP), and Cochrane Library database were searched from September 14, 2022, to October 12, 2022. Controlled terms (MeSH) and keywords (Table 2) were combined for the search strategy using “upper lip lift” OR “subnasal lip lift” OR “philtrum shorten.”

Table 2.

Specific search terms of databases

| Database | Search term |

|---|---|

|

MEDLINE (via PubMed) |

(("upper"[All Fields] OR "uppers"[All Fields]) AND ("lip"[MeSH Terms] OR "lip"[All Fields]) AND ("lifting"[MeSH Terms] OR "lifting"[All Fields] OR "lift"[All Fields])) OR ("subnasal"[All Fields] AND ("lip"[MeSH Terms] OR "lip"[All Fields]) AND ("lifting"[MeSH Terms] OR "lifting"[All Fields] OR "lift"[All Fields])) OR (("lip"[MeSH Terms] OR "lip"[All Fields] OR "philtrum"[All Fields]) AND ("shorten"[All Fields] OR "shortened"[All Fields] OR "shortening"[All Fields] OR "shortenings"[All Fields] OR "shortens"[All Fields])) |

| EMBASE (OvidSP) |

('upper lip'/exp OR 'upper lip') AND ('lift'/exp OR lift) OR 'subnasal lip lift' OR (subnasal AND ('lip'/exp OR lip) AND ('lift'/exp OR lift)) OR 'philtrum shorten' OR (('philtrum'/exp OR philtrum) AND shorten) |

| Cochrane Library | (upper lip lift) OR (subnasal lip lift) OR (philtrum shorten) |

Data Extraction

Two of the authors performed the search independently and any disagreement was resolved by discussion. If dissimilarity occurred between the two authors, the senior author made the ultimate decisions.

Completed data collection included study characteristics, techniques, objective evaluation measurements, clinical outcomes (degree of the lift), patient satisfaction, adverse effects, and longevity of the lifting.

Summary Measures

Objective and quantitative outcome measures utilized to evaluate the lifting degree were organized and summarized.

Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

Demographics of the included patients were collected. [43]

Quality Control of Included Studies

The included studies were assessed employing the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Levels of Evidence. [44]

Results

Included Studies

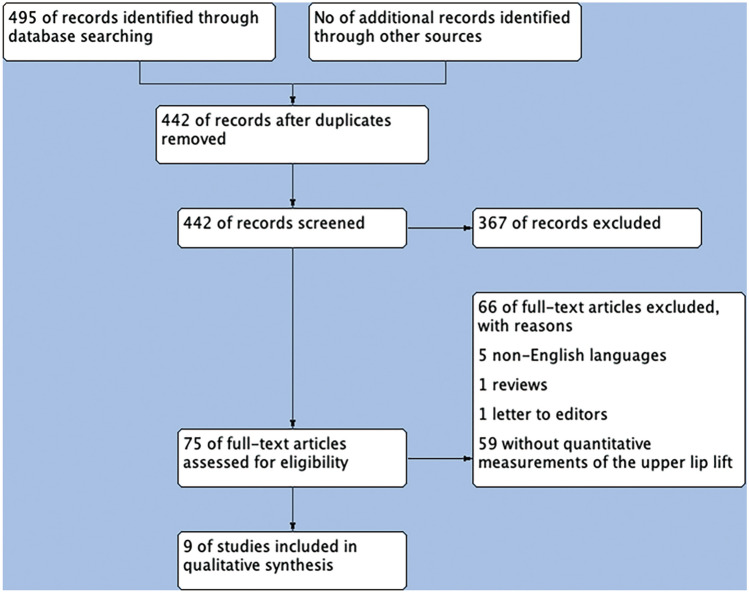

A total of 495 studies were identified through the search strategy. After the removal of duplicates, 442 citations were screened and 75 articles were selected for full-text review. Nine articles finally matched the selection criteria, reporting on upper lip lift techniques with quantitative measurements of the lifting degree. (Figure 1)

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection

Study Characteristics

In total, 780 patients were enrolled in the nine studies. [8, 12, 29, 33, 45–49] In eight studies that reported descriptive gender data, 91.07% of the patients were women(n=683), 7.33% were men(n=55) and 1.60% were transgender(n=12). [8, 12, 29, 45–49] The mean age at treatment was 46.01 years with a range of 21 to 83 years. The mean time to follow-up was 31.48 months with a range from 2 months to 10 years. Of the studies enrolled in this systematic review, eight assessed an invasive technique to lift the upper lip in 777 patients [8, 12, 29, 33, 46–49] and one study assessed a noninvasive technique in three patients [45]. All studies reported the quantitative measurements of the upper lip, and five studies described differences in ethnicity. No meta-analysis could be performed because the metrics and outcomes were too diverse.

Techniques

As for invasive techniques to lift the upper lip [40], eight studies were included that examined: (1) subnasal lip lift with (a) a subnasal bull’s horn excision [8, 29, 46, 47], (b) a subnasal wavy ellipse excision [33, 49], (c) two subnasal incisions, sparing the philtral columns and groove [12], (d) a subnasal bull’s horn excision with ‘‘T’’-shaped muscle resection [48], and (2) lip advancement with vermillion border gull wing excision [33]. Seven of the eight studies included a follow-up period of at least 12 months [12, 29, 33, 45–49]. A follow-up of 3 years or more was described in five of the eight studies [29, 33, 46, 47, 49]. Jung et al showed a high degree in all patients [12], Pan et al described a patient satisfaction rate of 96.1%(n=73) [48], and Lee et al demonstrated that 186 patients (92.1%) were satisfied with the aesthetic results according to a 5-point scale questionnaire [29]. However, patient satisfaction was not described in other studies.

As for noninvasive techniques to lift the upper lip, only one study was included in three patients by injecting botulinum toxin A in the upper lip [45]. The lift effects lasted fewer than a month. Patient satisfaction was not described in this study. Notwithstanding, the former studies were all noncontrolled and nonblinded. (Table 3) (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 3.

Overview of studies

| Reference | Type of study | Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Studies using invasive techniques | ||

| Patel et al [8] | Case series | Subnasal lift |

| Case series | Subnasal lift with separation between skin and muscle | |

| Nagy et al [42] | Retrospective | Subnasal lift |

| Marechek et al [47] | Retrospective | Subnasal lift |

| Jung et al [12] | Retrospective | Subnasal short scar lift |

| Pan et al [48] | Retrospective | Subnasal lift with orbicularis oris resection |

| Lee et al [29] | Retrospective | Subnasal lift |

| Raphael et al [49] | Retrospective | Endonasal lift |

| Holden et al [33] | Retrospective | Lip advancement |

| Retrospective | Subnasal lift | |

| Studies using noninvasive techniques | ||

| Li et al [45] | Case report | Botulinum toxin A |

Quantitative Measurements

As for approximative measurements, anatomical ratios were included in seven studies [12, 29, 33, 46–49]. The most commonly used measurement was photographic analysis using the (1) white-to-white corneal distance [46, 47] or the (2) alar-medial canthus line [12, 33] as a conversion factor to make all photographs comparable. Nagy et al [46] used the white-to-white corneal distance as a scale to measure the distance of the columella to Cupid’s bow, bilateral columella to Cupid’s peak, bilateral mid-sill to the vermillion border, bilateral lateral nasal ala to the vermillion border, and upper red lip show from Cupid’s bow to the mucosal edge of the upper lip, while Marechek et al [47] used the same scale for philtrum length, vermillion length, and alar width. Jung et al [12] calculated the distance through the midphiltrum to the vermilion border using the alar-medial canthus as a reference. Holden et al [33] recorded the same distance in the subnasal lip lift group with additional measurements from the right alar rim to the lateral vermilion border in the lip advancement group. Also, a caliper was used to measure philtrum and upper lip heights and then calculate the upper lip to lower face ratio and philtral to labial height ratio [48]. In Lee’s study, the philtrum length was measured face to face, and the ratio of the philtrum to the height of the visible upper vermilion was measured by photographs [29]. Repeal et al [49] advocated a classification system [50] to categorize patients into four types by labial and philtral height, a philtral-labial score, and dental show. However, the way how to measure was not described in the study.

As for exact measurements, 3D photographs and 3D analysis were included in two studies [8, 45]. Patel et al [8] took 3D photographs using the VECTRA H1 system, and 3D analysis was performed including vermillion height and width, philtral height, sagittal lip projection, vermillion surface area, and incisor show. Li et al [45] used the same system to capture 3D photographs with different nasolabial landmarks and eight linear distances, including philtrum width, upper lip height, cutaneous upper lip height, upper vermilion height, cupid’s bow height, right vermilion margin lateral height and left vermilion margin lateral height (Table 4).

Table 4.

Schematic representation of different techniques and quantitative measurements

| Reference | Technique | Quantitative measure method |

|---|---|---|

| Studies using invasive techniques | ||

| Patel et al [8] |

Subnasal bull’s horn excision |

3D VECTRA H1 assess the whole upper lip area |

| Nagy et al [42] |

Subnasal bull’s horn excision |

Anatomic ratio calculating by the white-to-white cornea distance |

| Marechek et al [47] |

Subnasal bull’s horn excision |

Anatomic ratio calculating by the white-to-white cornea distance |

| Jung et al [12] |

Two subnasal incisions, sparing the philtral columns and groove |

Anatomic ratio calculating by the ala-to-medial canthus distance |

| Pan et al [48] |

Two subnasal incisions, sparing the philtral columns and groove |

Philtrum and upper lip heights were measured by a caliper to calculate the philtral to labial height ratio |

| Lee et al [29] |

Subnasal bull’s horn excision |

The philtrum length was measured face to face, and the ratio of the philtrum to the height of the visible upper vermilion was measured by photographs. |

| Raphael, et al, [49] |

Subnasal wavy ellipse with endonasal advancement flaps |

Calculate the philtral-labial score without mention how to measure |

| Holden et al [33] |

Vermillion border Gull wing excision |

Anatomic ratio calculating by the ala-to-medial canthus distance |

|

Subnasal wavy ellipse excision |

Anatomic ratio calculating by the ala-to-medial canthus distance |

|

| Studies using noninvasive techniques | ||

| Li et al [45] |

A total of 4U BTA injection at the vermilion border of the upper lip |

3D VECTRA H1 assess the whole upper lip area |

Adverse Effects

No severe adverse events were described for both surgical and nonsurgical lip lifting procedures. For subnasal lip lift procedures, the most common short-term complication was minor adverse such as redness [12], swelling [12], dehiscence caused by hematoma [29] (0.64%, n=5), and asymmetric upper lip [29] (0.64%, n=5). The most common long-term complications were obvious incisions scar [12, 29, 48, 49](4.36%, n=34). Pan et al [48] described a downshift of the subnasal and increased exposure of the nostril (2.05%,n=16), increased thickness of the philtrum, and prominent vermilion tubercle (1.15%,n=9). Raphael et al [49] demonstrated a subnasal wavy ellipse with endonasal advancement flaps, thus reported adverse events associated with such as localized wound separation(0.77%,n=6), under-correction(3.21%,n=25), alar distortion(4.87%,n=38), sill widening(3.72%,n=29) and sill deformation(5.13%,n=40). For lip advancement, asymmetry of the vermilion border was observed in 0.26% (n=2) of all the patients [33]. For nonsurgical procedures, all three patients complained about slight perioral muscular palsy and mouth incompetence [45]. (Table 5)

Table 5.

Summary of complications of different techniques

| Technique | Complications | Numbers of patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Short-term complication | ||

| Subnasal lip lift | Redness and swelling of the incision | 3(0.39) |

| Dehiscence caused by hematoma | 2(0.26) | |

| Asymmetric upper lip | 5(0.64) | |

| Long-term complication | ||

| Visible scar | 34(4.36) | |

| Downshift of the subnasal and increased exposure of nostril | 16(2.05) | |

| Increased thickness of the philtrum and prominent vermilion tubercle | 9(1.15) | |

| Localized wound separation | 6(0.77) | |

| Under-correction | 25(3.21) | |

| Alar distortion | 38(4.87) | |

| Sill widening | 29(3.72) | |

| Sill deformation | 40(5.13) | |

| Upper lip advancement | Asymmetry of the vermilion border | 2(0.26) |

| Botulism toxin A injection | Slight perioral muscular palsy | 3(0.39) |

| Mouth incompetence | 3(0.39) | |

Disclosure Agreements [43]

Only one of the nine studies was provided with a disclosure agreement of support by the university (Table 6). Therefore, there was no conflict of interest.

Table 6.

A disclosure agreement of support by the manufacturer

| Reference | Financial interests or support |

|---|---|

| Studies using invasive techniques | |

| Patel et al [8] | None reported/Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article. |

| Nagy et al [42] | No funding was received for this article. |

| Marechek et al [47] | Not published |

| Jung et al [12] | The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. |

| Pan et al [48] | None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript. |

| Lee et al [29] | This article was supported by the 2014 Yeungnam University Research Grant. |

| Raphael et al [49] | The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article. |

| Holden et al [33] | None reported. |

| Studies using noninvasive techniques | |

| Li et al [45] | The authors report no conflict of interest. |

Quality Control of Included Studies [43]

Seven of the nine included studies were Level of Evidence IV studies, and two studies were Level of Evidence V studies (Table 7).

Table 7.

Quality assessment of included studies according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine Criteria

| Reference | Level of evidence |

|---|---|

| Studies using invasive techniques | |

| Patel et al [8] | Therapeutic, IV. |

| Nagy et al [42] | Therapeutic, IV. |

| Marechek et al [47] | Therapeutic, IV. |

| Jung et al [12] | Therapeutic, V. |

| Pan et al [48] | Therapeutic, IV. |

| Lee et al [29] | Therapeutic, IV. |

| Raphael et al [49] | Therapeutic, IV. |

| Holden et al [33] | Therapeutic, IV. |

| Studies using noninvasive techniques | |

| Li et al [45] | Therapeutic, V. |

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to identify both techniques and outcome measures employed within the upper lip lift literature. Both surgical and nonsurgical procedures could show a lifting effect on the subnasal lip with good patient satisfaction. Surgical procedures, with a mean follow-up length of 31.48 months (range: 2 months to 10 years), have more longevity than nonsurgical procedures, while an incision scar is inevitable. The quantitative outcome measurements vary a lot and reveal salient discrepancies across the upper lip lift literature.

It is necessary to capture the aesthetic characteristics of the perioral region. The components of the perioral aesthetic include both soft tissue and skeletal elements which include the dimensions of the philtrum and upper lip skin, the vermillion, perioral fat compartments, as well as dentition and cephalometric relationships [8]. There is experimental agreement that a greater vermilion show, a shorter philtrum, and symmetric and prominent philtral columns are more appealing [51, 52]. According to research, the philtrum to upper vermilion ratio should ideally be between 2 and 2.9, and the upper-to-lower vermilion ratio should be between 0.75 and 0.8 [50]. Despite the availability of referable aesthetic criteria, Heidekrueger et al discovered that the ideal proportions to define an attractive lip might be influenced by multiple sociocultural and demographic factors [53]. Although the desired perioral aesthetic criteria may differ across different ethnic and geographic backgrounds, it is widely acknowledged that the ratio of cutaneous skin height to upper vermilion height should be less than 3 [50]. Age-related changes to the upper lip, including soft tissue descent and deflation, lead to an extended and thin upper lip with diminished maxillary incisor show, affecting these optimum ratio [15, 17]. Consideration of these ideal ratios during the treatment planning will significantly improve lip lift outcomes [54]. Through skin excision and advancement of the soft tissue complex, the surgical procedure can effectively shorten the distance between the nasal base and the vermilion border of the upper lip, thereby improving the philtrum to upper vermilion proportions [55]. Nonsurgical procedures, such as lip fillers, generally improve the ratio of the philtrum to the vermilion by restoring volume to the lip [25].

Different surgical techniques to lift the upper lip have been summarized in the literature [56]. In general, the surgical treatment typically referred to as the lip lift operation is a method of correcting the aging upper lip that was first described by Cardosa and Sperli in 1971 and has subsequently undergone various modifications [29, 49, 57–60]. Commonly, the procedure entails the excision of a section of the upper lip with the purpose of decreasing the cutaneous top lip height and boosting the maxillary incisor display. The excision pattern is often a “bullhorn” or a “wavy ellipse”-shaped wedge resection with the scar buried in the nasal crease. There is also another option, lip advancement procedures, in which the incision is made along the vermillion border to generate a more radial vector of lift [9, 33]. The key to a good outcome in surgical methods is incision design that respects the natural anatomy, placing the tension of the lip deep to the dermis to alleviate tension off the skin incision, identifying the proper amount of lift for the patient’s anatomy, and not violating the orbicularis oris [32]. Apart from the volume contribution of the orbicularis oris muscle, the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) of the upper lip is the principal support mechanism for the skin’s youthfulness. Noticeably, the SMAS layer thins with age, making rhytids in the upper lip more visible [60]. Talei et al developed a modified cupid lift procedure that focuses on releasing the SMAS in the patient’s perioral region and provided extensive details of patient selection and upper lip excision design [60]. Despite the fact that the surgical procedure has been in use for four decades and is widely accepted [3, 20, 31], only eight articles met the inclusion criteria. The limited number of studies included was due to a lack of quantitative measurements in many of them. The reported mean follow-up period was 31.48 months, showing a satisficed longevity of the lifting effect. Anyhow, for surgical procedures, scarring is generally the patient’s main concern and has been reported in 4.36% of cases. To decrease scarring, Lee et al injected botox into the orbicularis oris muscle following precise wound closure [29], and Marechek et al used CO2 laser to blend the incision site [47]. Almost all research included in this systematic review that discussed such procedures reported excellent patient satisfaction; however, most studies failed to analyze patient satisfaction using validated questionnaires. The most common and longest-standing procedure is the subnasal lip lift with a bull’s horn excision, which is appropriate for most patients except those with a drooping lip corner [8, 29, 46, 47]. By localizing tension deep within the nasal vestibule onto relatively immobile tissue, the endonasal lip lift technique with a wavy excision can produce enhanced stability, intranasally hidden scar, and camouflage at the nasolabial junction49. Candidates are patients who have a tall philtral height with normal or short labial height (the philtral-labial score > 3) and 0-mm dental show. Noticeably, to avoid nasal sill disruption, the surgery must be performed with great precision. Lip advancement with vermillion border gull wing excision has limitations in use because the scar around the vermillion may influence anatomic function [33], while techniques utilizing two subnasal incisions are minimally invasive and may benefit younger cosmetic patients as well as Asian patients [12].

Noninvasive treatments for rejuvenating perioral tissues or lifting the upper lip include injecting fillers [25], laser [35], serums [36], or a combination of these, as aging causes not only volume loss, but also perioral wrinkles on the lip [61]. However, the former reports lacked quantitative measurements or failed to pay attention to the upper lip lifting efficiency and thus were excluded from our research. Only one study utilizing Botulinum toxin A (BTA) met the inclusion criteria [45]. The aim of applying botox to lift the upper lip is to inhibit the contraction of the orbicularis oris muscle, a circular muscle that resides around the lip. It is made up of deep and superficial fibers that serve many purposes. The deep fiber is a constrictor muscle that aids in the retention of food and fluids while eating, whereas the superficial fiber is a retractor muscle that aids in speaking and facial expressions when working with other muscles [62]. Botox can inhibit acetylcholine release at the myoneural junction, resulting in a paralyzed effect of the orbicular oris muscle. As a result, the lip gets more everted, leading to an augmented upper lip and a shortened philtrum. There are just minor short-term complaints regarding slight perioral muscular palsy and month incompetence. However, the lifting effect lasted less than a month, with no mention of patient satisfaction, and no comparison with surgical treatments could be conducted due to the diverse measure metrics and outcomes.

Quantitative measurements are significant for both clinical decision-making and future high-level evidence analysis. As for clinical choice, Patel et al used three-dimensional technique metrics to provide quantifiable results indicating the average decrease in philtral length, and the amount of tissue resected do not have a line relationship [8]. The study reported that a 2.5-mm resection reduced philtral length by 3.37 mm on average, whereas a 5-mm resection reduced philtral length by 7.25 mm on average. Since the philtrum to upper vermilion ratio, which should ideally range from 2 to 2.9 [50], is calculated by comparing the heights of the cutaneous skin and the upper vermilion, small inaccuracies in the postoperative philtrum height may cause changes in the ratio and produce results that are significantly different from the desired ratio value. Therefore, a quantitative assessment is essential for proper preoperative design as well as for determining the precise longevity of lifting efficiency. In terms of study quality, the literature on lip lifting often has a not high level of evidence (LOE), and the lack of uniformity across the studies may lead to a number of issues. Usually, a successful systematic review and meta-analysis are considered the highest LOE, while they require consistent outcome reporting to be effective [37]. The heterogeneity limits the comparison between articles and outcomes, thus limiting the clinical choice. Within the upper lip lifting literature, our systematic review identified two metrics: anatomy ratio calculation through photographic analysis or direct height measurement using a caliper, and precise parameters using a three-dimensional approach. The photographic analysis is the most practical method and particularly well-suited for retrospective studies since preoperative and postoperative photographic data for facial aesthetic surgery are typically well documented. The conversion factor to calculate the anatomy ratio of the philtrum consists of the white-to-white corneal distance [46, 47] and the alar-medial canthus distance [12, 33]. We properly recommend the former as a reference because it is more accurate since the two inner canthi are two spots with certain anatomical sites. The alar, on the other hand, is an area with a more ambiguous anatomical position, which might lead to erroneous information. Three-dimensional measuring is a more precise and comprehensive approach that can measure not only philtrum length, but also sagittal projection and the size of the overall upper vermillion surface. However, such a machine may be not available in every research team, restricting its usage and popularity in the upper lip lifting metrics.

There are some limitations to this evaluation. For starters, this search was confined to English language papers; so, relevant outcomes and outcome measures in non-English journals may have been missed. Furthermore, despite the fact that this study used a comprehensive electronic database technique, no search of the gray literature was conducted, and pertinent papers may have been overlooked accidentally. Additionally, only nine papers satisfied the inclusion criteria for this review out of the 495 articles discovered following database screening. The main reason for the small number of articles is that most of them do not employ quantitative data to evaluate lifting efficacy. Furthermore, the reported ethnic characteristics vary greatly, making it impossible to compare the aesthetic variations and surgical outcomes of upper lip lifting in different ethnic groups with certain. And because the reported ages were predominantly in senior citizens, with a mean age of 46.01 years (range: 21 to 83 years), it may not be applicable to young persons with a congenital lengthened upper lip.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have the highest level of evidence, while the quality of these studies and the outcomes they assess depend primarily on the data on which the analysis is based [37]. Nevertheless, they cannot be employed successfully in the upper lip lift literature since most research has reported non-quantitative results or diverse outcomes. As a result, the majority of published clinical research on this topic (as well as other procedures) cannot contribute to better quality evaluation and analysis. To further study the success of a surgical or nonsurgical upper lip lifting procedure, we propose that future research include quantitative measures to evaluate the upper lip lifting outcomes, which can be beneficial for both clinical decision-making and high-level evidence research.

Conclusion

This is the first research to systematically evaluate both surgical and nonsurgical upper lip lifting techniques, accounting for patient satisfaction, adverse effects, and, most critically, quantitative measurements of lifting effectiveness. Overall, surgical therapies appear to provide a higher and longer-lasting lifting influence on upper lip lift with an inevitable scar, whereas nonsurgical techniques look to be minimally invasive but conservative. The variability in the results used to assess lifting efficiency necessitates greater uniformity in quantitative measurements to support clinical decision-making and future high-level evidence analysis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No.2021JJ30034).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wollina U. Perioral rejuvenation: restoration of attractiveness in aging females by minimally invasive procedures. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1149–1155. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S48102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonnard PL, Verpaele AM, Ramaut LE, Blondeel PN. Aging of the Upper Lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:1333–1342. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felman G. Direct upper-lip lifting: a safe procedure. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1993;17:291–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00437101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bashour M. History and Current Concepts in the Analysis of Facial Attractiveness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:741–756. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000233051.61512.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzgerald R, Graivier MH, Kane M, et al. Facial aesthetic analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2010;30:25S–27S. doi: 10.1177/1090820X10373360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trinh LN, Safeek R, Herrera D, Gupta A. Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Impacted Interest in Cosmetic Facial Plastic Surgery? A Google Trends Analysis. Facial Plast Surg. 2022;38:285–292. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1740623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramaut L, Tonnard P, Verpaele A, et al. Aging of the upper lip: part i: a retrospective analysis of metric changes in soft tissue on magnetic resonance imaging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:440–446. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel AA, Schreiber JE, Gordon AR, et al. Three-Dimensional Perioral Assessment Following Subnasal Lip Lift. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42:733–739. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjac070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fanous N. Correction of Thin Lips. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:33–41. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knize DM. Lifting of the upper lip: Personal technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1836–1837. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000117662.39494.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerrissi JO, Sanchez LI. An Approach to the Senile Upper Lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1187–1191. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199311000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung J-A, Kim K-B, Park H, et al. Subnasal Lip Lifting in Aging Upper Lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143:701–709. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guyuron B, Rowe DJ, Weinfeld AB, et al. Factors contributing to the facial aging of identical twins. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1321–1331. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819c4d42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raschke GF, Rieger UM, Bader R-D, et al. Perioral aging–an anthropometric appraisal. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2014;42:e312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Penna V, Stark G-B, Eisenhardt SU, et al. The aging lip: a comparative histological analysis of age-related changes in the upper lip complex. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:624–628. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181addc06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pensler JM, Ward JW, Parry SW. The superficial musculoaponeurotic system in the upper lip: an anatomic study in cadavers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75:488–494. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198504000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mally P, Czyz CN, Wulc AE. The Role of Gravity in Periorbital and Midfacial Aging. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34:809–822. doi: 10.1177/1090820X14535077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponsky D, Guyuron B. Comprehensive surgical aesthetic enhancement and rejuvenation of the perioral region. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31:382–391. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11409009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker S, Lee MR, Thornton JF. Ergotrid flap: a local flap for cutaneous defects of the upper lateral lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:460e–464e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31822b6741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin HW. The Lip Lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77:990–994. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198606000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE, Ristow B. The youthful cheek and the deep medial fat compartment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:2107–2112. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31817123c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambros V. Observations on periorbital and midface aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1367–1376. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000279348.09156.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flowers RS, Jr, EMS, Technique for Correction of the Retracted Columella, Acute Columellar-Labial Angle, and Long Upper Lip. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999;23:243–246. doi: 10.1007/s002669900276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon AR, Schreiber JE, Tortora SC, et al (2021) Turning back the clock with lip lift: quantifying perceived age reduction using artificial intelligence. Facial Plast Surg Aesthetic Med fpsam.2020.0560. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Rho N-K, Goo BL, Youn S-J, et al. Lip lifting efficacy of hyaluronic acid filler injections: a quantitative assessment using 3-dimensional photography. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4554. doi: 10.3390/jcm11154554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waldman SR. The Subnasal Lift. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2007;15:513–516. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moragas JSM, Vercruysse HJ, Mommaerts MY. “Non-filling” procedures for lip augmentation: a systematic review of contemporary techniques and their outcomes. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2014;42:943–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Georgiou CA, Benatar M, Bardot J, et al. Morphologic variations of the philtrum and their effect in the upper lip lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:996e–997e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee DE, Hur SW, Lee JH, et al. Central Lip Lift as Aesthetic and Physiognomic Plastic Surgery: The Effect on Lower Facial Profile. Aesthet Surg J. 2015;35:698–707. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alster TS, West TB. Human-derived and new synthetic injectable materials for soft-tissue augmentation: current status and role in cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2515–3252. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200006000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rozner L, Isaacs GW. Lip lifting. Br J Plast Surg. 1981;34:481–484. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(81)90063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sturm A. Lip lift. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2022;55:835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2022.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holden PK. Long-term analysis of surgical correction of the senile upper lip. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2011;13:332. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.2011.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghannam S, Bageorgou F. The lip flip for beautification and rejuvenation of the lips. J Drugs Dermatol JDD. 2022;21:71–76. doi: 10.36849/JDD.6344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McDaniel DH, Lord J, Ash K, Newman J. Combined CO2/erbium:YAG laser resurfacing of peri-oral rhytides and side-by-side comparison with carbon dioxide laser alone. Dermatol Surg Off Publ Am Soc Dermatol Surg Al. 1999;25:285–293. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moy M, Diaz I, Lesniak E, Giancola G. Peptide-pro complex serum: investigating effects on aged skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 doi: 10.1111/jocd.14992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassan Y, Leveille CF, Gallo L, et al. Reporting outcomes and outcome measures in open rhinoplasty: a systematic review. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40:135–146. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hassouneh B, Brenner MJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis in facial plastic surgery. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2015;23:273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waltho D, Gallo L, Gallo M, et al. Outcomes and outcome measures in breast reduction mammaplasty: a systematic review. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40:383–391. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamin F, McAuliffe PB, Vasilakis V. Aesthetic surgical enhancement of the upper lip: a comprehensive literature review. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2021;45:173–180. doi: 10.1007/s00266-020-01871-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, et al. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Sluis N, Gülbitti HA, van Dongen JA, van der Lei B. Lifting the mouth corner: a systematic review of techniques, clinical outcomes, and patient satisfaction. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42:833–841. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjac077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.OCEBM Levels of Evidence Working Group. The Oxford Levels of Evidence 2. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2011.https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence

- 45.Li Y, Chong Y, Yu N, et al. The use of botulinum toxin A in upper lip augmentation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:71–74. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagy C, Bamba R, Perkins SW. Rejuvenating the Aging Upper Lip: The Longevity of the Subnasal Lip Lift Procedure. Facial Plast Surg Aesthetic Med. 2022;24:95–101. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2021.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marechek A, Perenack J, Christensen BJ. Subnasal lip lift and its effect on nasal esthetics. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;79:895–901. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2020.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan B-L. Upper lip lift with a “T”-shaped resection of the orbicularis oris muscle for Asian perioral rejuvenation: a report of 84 patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg JPRAS. 2017;70:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raphael P, Harris R, Harris SW. The endonasal lip lift: personal technique. Aesthet Surg J. 2014;34:457–468. doi: 10.1177/1090820X14524769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raphael P, Harris R, Harris SW. Analysis and classification of the upper lip aesthetic unit. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:543–551. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829accb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suryadevara AC. Update on perioral cosmetic enhancement. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;16:347–351. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e3283079cc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Penna V, Fricke A, Iblher N, et al. The attractive lip: a photomorphometric analysis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg JPRAS. 2015;68:920–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heidekrueger PI, Szpalski C, Weichman K, et al. Lip attractiveness: a cross-cultural analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37:828–836. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fallahi HR, Keyhan SO, Bohluli B, et al. Lip lift techniques in smile design. Dent Clin North Am. 2022;66:443–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2022.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salibian AA, Bluebond-Langner R. Lip Lift. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2019;27:261–266. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Júnior LCA, da Silva Cruz NT, de Vasconcelos Gurgel BC, et al (2022) Impact of subnasal lip lift on lip aesthetic: a systematic review. Oral Maxillofac Surg. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Talei B. The modified upper lip lift. Facial Plast Surg Clin N Am. 2019;27:385–398. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li YK, Ritz M. The modified bull’s horn upper lip lift. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71:1216–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramirez OM, Khan AS, Robertson KM. The upper lip lift using the “bull’s horn” approach. J Drugs Dermatol JDD. 2003;2:303–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Talei B, Pearlman SJ. CUPID Lip Lift: advanced lip design using the deep plane upper lip lift and simplified corner lift. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42:1357–1373. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjac126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paes EC, Teepen HJLJM, Koop WA, Kon M. Perioral wrinkles: histologic differences between men and women. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:467–472. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nicolau PJ. The orbicularis oris muscle: a functional approach to its repair in the cleft lip. Br J Plast Surg. 1983;36:141–153. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(83)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.