Abstract

While traditional and non-traditional issues of security are at the very top of the policy agenda, security studies has been subject to much criticism. These concerns have often been framed in terms of challenges to the field’s relevance. This paper seeks to further the debate on relevance in security studies. Specifically, the paper examines the field in three major dimensions of relevance: responsiveness, diversity, and intellectual pluralism. Unlike previous disciplinary investigations, which have solely focused on United States (US) security studies, this paper examines trends pertaining to relevance in security studies in the USA as well as in Europe. The paper finds some evidence of responsiveness, a slight trend toward a more equitable share of female authors, and conflicting evidence when it comes to intellectual pluralism. The paper suggests that the field appears more as a ‘broad church’ than ‘irrelevant cult’ when its output in the USA, as well as in Europe, is taken into account.

Keywords: Security studies, Critical security studies, European security studies, US security studies

Introduction

At the same time as a variety of threats to states, communities, and individuals are widely perceived to have multiplied in the form of a return of great power competition, as well as a number of non-traditional issues such as climate change and pandemics, the academic study of security has of late been subject to much criticism. Over the years, several traditional scholars have alleged that scholarship in security studies has been increasingly focused on intra-disciplinary disputes to the detriment of relevance for the world outside academia (e.g., Walt 1999, 2009; Desch 2015, 2019; Mearsheimer and Walt 2013). Michael Desch, for instance, has in a recent study chided security studies for its increasing other-worldliness and referred to the field as a “cult of the irrelevant” (Desch 2019). Critical scholars in security studies have also expressed severe misgivings about the state of the field. Laura Sjoberg, for instance, has argued that security studies has never been particularly relevant to marginalized communities, i.e., the ones who she thinks should comprise the referent object of the discipline (Sjoberg 2015, p. 396). Thus, neither traditional nor critical scholars of security seem satisfied with the state of the academic study of security.

Although previous studies have shed some light on various aspects of security studies as a scholarly field, we know little about major trends pertaining to questions of relevance across the entire subfield in the past decade. To further the scholarly debate about the relevance of the field, this paper offers two contributions. First, it proposes a broad and measurable conceptualization of relevance in security studies, understood as the potential for scholarship to inform the world outside academia. The paper argues that there are at least three significant pre-conditions for exerting such influence, here referred to as dimensions of relevance. The first dimension, responsiveness, refers to how well the discipline responds to the world in which it finds itself. The second dimension, inclusivity, refers to the field’s inclusivity of female authors, as well as the geographical distribution of authorship. The final dimension, intellectual pluralism, refers to the theoretical and methodological traditions represented in the field’s output. Second, and against the background of such a conceptualization, the paper offers a tentative assessment of how well the study of security in the USA, as well as in Europe, has fared across these dimensions of relevance.

One may no doubt imagine a number of different artifacts to include when examining trends in a particular field. However, as Ole Waever has pointed out, for scholars, an academic field “exists mostly in the journals” (Waever 1998, p. 697). In order to assess the relevance of the field of security studies, the article examines the major subfield specific journals in the USA and Europe in 2010–2020: International Security, Security Studies, and Contemporary Security Policy as well as Security Dialogue, European Security, and European Journal of International Security. The paper has limited itself to the USA and Europe since security studies as a distinct field of academic study emerged in the West and remained a home to the vast majority of journals in security studies and, more widely, International Relations (Buzan and Hansen 2009). Most of the previous literature, which empirically examines the field, draws on the datasets provided by the TRIP Project (Teaching, Research, and International Policy).1 This paper, however, draws on its own coding since the categories used by the TRIP Project are too general and adjusted to IR as a field, rather than the substantial topics within security studies. Moreover, European security studies journals are not included in the TRIP datasets.

Dimensions of relevance in security studies

In the literature examining security studies, concerns of relevance have often been at the forefront, grappling with questions of who and what the field is for. Michael Desch has recently argued that while scholars in the Cold War era attempted to produce scholarship relevant to the concerns of policy-makers, they have since then become increasingly driven by intra-disciplinary incentives. To support this claim, he shows that a decreasing number of articles in the top IR journals offer policy recommendations (Desch 2019, p. 3). At the root of the growing gap between academia and the policy world, he suggests, lies a growing professionalization of political science, which has increasingly incentivized methods-driven and model-based scholarship (Desch 2019, p. 241). To Desch, relevance has primarily to do with scholarship seeking to inform high-level discussions among policy-makers (Desch 2019, p. 5), and his understanding of relevance recalls Bruce W. Jentleson and Ely Ratner’s definition of policy-relevant scholarship as work “that advance knowledge with an explicit priority of addressing policy questions” (Jentleson and Ratner 2011, p. 8).

What makes a field relevant lies, to some extent, in the eye of the beholder (Eriksson 2014). However, several scholars have argued that a narrow definition of relevance, understood as whether scholarship directly addresses policy questions circulating among elite communities of practitioners, is inadequate (Eriksson 2014; Horowitz 2015; Oren 2015; Sjoberg 2015). When Stephen Walt referred to the field as a “cult of irrelevance,” his concerns about security studies were broader, including that academics had become less preoccupied with the broader societal relevance of their research (Walt 2009). More specifically, Laura Sjoberg has taken issue with Desch’s narrow understanding of relevance and argued that “elite American policy-makers are the wrong audience for relevance” (Sjoberg 2015, p. 396) Thus, the imagined audience of scholarship in security studies needs to be widened significantly, to include not only policy-makers but the broader strata of societies, such as, a variety of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) which make up global civil society.

Underlying the debate on relevance, lies a shared concern about the academy becoming increasingly removed from the world outside itself. In this paper, I understand relevance as the potential of scholarship to inform the world beyond the academy. On such an understanding, there are at least three pre-conditions for exerting such an influence, which are here referred to as dimensions of relevance: responsiveness, diversity of authorship, and intellectual pluralism. As we shall see, these dimensions enjoy support among scholars working within traditional and critical security studies. These dimensions are clearly not the only pre-conditions for relevance. They do, however, correspond to widespread sentiments in the discipline. Furthermore, they also lend themselves to operationalization. For the purposes of this article, they provide the framework against which the field’s relevance will be assessed. Below, these dimensions are justified and operationalized.

Responsiveness

One of the most significant questions animating the debate on relevance in security studies is whether the academic study of security sufficiently relates to the world in which it finds itself—perhaps the most essential pre-condition for a relevant field. As Desch puts it, the field should address “pressing real-world problems” instead of just chasing “disciplinary fads” (Desch 2019, p. 251). On closer inspection, there does not seem to be much disagreement on this point among scholars working within different traditions. This question was at the heart of the debate within security studies in the 1990s. Stephen Walt’s complaint against critical scholars consisted in the contention that “issues of war and peace are too important to be diverted into a prolix and self-indulgent discourse that is divorced from the real world” (Walt 1991, p. 223). Walt worried that a focus on discursive representation would turn scholarship away from the world. Somewhat similarly, the charge against traditional security studies, i.e., the study of military threats to state security, was from the very inception of its critical work, thought to be, in Ken Booth’s words, “unrealistic” and unresponsive to the concerns of ordinary people and in particular marginalized groups (Booth 1991; and see Sjoberg 2015).

So far, however, we lack systematic knowledge of what security studies as an entire field has dealt with in the last decade. Previous scholarship examining the academic study of security has tended to focus heavily on US-oriented security studies and neglected the field’s European trajectory (Maliniak et al. 2018; Hoagland et al. 2020). There is a prima facie reason to believe that externalist drivers are of great significance in accounting for the development of security studies. As Buzan and Hansen have noted, security studies “is remarkable by being founded in response to a set of (what was perceived as) very urgent real world/external issues linked to the growing threat posed by the Soviet Union” (Buzan and Hansen 2009, p. 46). And as Michael Desch has showed, US security studies emerged in close tandem with the concerns of US policy-makers in the post-WW2 era (Desch 2019). To examine this, one does not have to either adopt or reject an objectivist ontology: One may examine the relation between the discipline and the world while remaining agnostic on whether an external security agenda is real in some strong sense or socially constructed.

To examine the responsiveness of the field, the paper takes a two-pronged approach, combining induction and deduction. First, taking an inductive approach, the field’s focus in the USA and Europe during the entire time period will be mapped out. To that effect, the paper begins by examining the proportion of the field dealing with a traditional state-centric conflict agenda versus a broader agenda, going back to the original rift between the scholars who wanted to broaden the agenda following the end of the Cold War, and to those who wanted to retain a focus on state-centric military conflict. The traditional understanding of security studies is state-centric, and, in Walt’s famous definition, deals with “the threat, use, and control of military force” (1991, p. 212). The broadeners, on the other hand, wanted to include a number of different issues beyond the military and political sectors, such as environmental and economic security, which entailed that a number of actors beyond states were understood as potential security actors (Buzan and Hansen 2009). The state-centric conflict agenda is then disaggregated into scholarship which focuses on pre-conflict, conflict, and post-conflict issues. These overarching agendas are then further disaggregated into substantive topics, which have been inductively arrived at. This initial step provides a broad overview of what the field has concerned itself with in the last decade.

Second, taking a deductive approach, the paper pinpoints some of the most widely discussed issues on the policy agenda and examines the extent to which the field has responded to their emergence (Table 1). To that effect, the paper draws on and updates the classification of security studies proposed by Buzan and Hansen, who suggested that there were three major external drivers behind the evolution of security studies: great power politics, technological changes, and key events (Buzan and Hansen 2009). First, the perhaps most intuitive external driver for security studies has historically been, as Buzan and Hansen note, the changing distribution of material capabilities among the great powers (Buzan and Hansen 2009, p. 53). The implosion of the Soviet Union and the end of the bipolar world order had, no doubt, a profound effect on security studies (e.g., Lebow and Risse-Kappen 1995). The two most important shifts in great power politics in the last decade have uncontroversially to do with Russia and what is usually referred to as “the rise of China.” It is common to trace the deteriorating relations between Russia and the West, extending back to the Russo-Georgian war in 2008 and the Russian intervention in Ukraine 2014 (Black and Johns 2016). When it comes to China, by 2019, the Brookings Institution showed that in the USA, a “new bipartisan consensus has emerged around a tougher, less restrained approach for challenging China’s rise” (Bush and Hass 2019), and by 2020, the US-EU perceptions of a threatening China had largely converged, albeit with some European governments remaining more ambivalent than the USA (Bartsch et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Policy agenda

| Agenda | Great power politics | Technological development | Key events |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Russia Rise of China |

Cybertechnology AWS |

Global financial crisis Terrorism Migration Environment/Climate Health/Pandemics |

As a second set of drivers of the discipline, new technologies have shaped the field from its very inception, with a large chunk of Cold War security studies grappling with questions pertaining to nuclear deterrence (Buzan 1987). What technological trends, then, might one expect security studies to have wrestled with in the last decade, if scholarship was responsive to real-world developments? Given that the dependency of Western societies on the Internet has increased dramatically, there has been much written on cybersecurity, which has emerged as one of the most important issues among western policy-makers in the last 10 years (Singer and Friedman 2014; Tikk and Kerttunen 2020). A few high-profile incidents of cyberattacks have spurred such an interest, most notably in Estonia 2007, and 6 years later, the European Union presented its first cybersecurity strategy (European Commission 2013). A second major technological development has to do with the emergence of autonomous weapons systems (AWS) such as robots and drones, which experts have even compared to the invention of gun powder and nuclear weapons in terms of their revolutionary potential (Altmann and Sauer 2017).

Third, it is clearly difficult to separate great power politics, technological developments, and key events. Nevertheless, a paradigmatic example of a key event, which heavily impacted security studies in the 2000s, is the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the USA (Buzan and Hansen 2009, p. 268). While there is no doubt room for other issues to include too, some of the most consequential events which have been much discussed among policy-makers, as well as the broader public in Europe and also in the USA, would include the global financial crisis, terrorism, migration, the environment/climate change, and health/pandemics.2 First, the global financial crisis, which initially hit the USA in 2007–2008, later to reach Europe in the form of a debt crisis starting in 2009, is often described as the most serious financial crisis since the Great Depression. Second, terrorism has remained high on the Western policy and media agenda, with high-profile attacks in Paris (2015), Brussels (2016), Nice (2016), Manchester (2017) and Barcelona (2017). In the USA, however, major terrorist attacks have, with some notable exceptions, been rare since 9/11. Third, a crisis which fundamentally transformed European politics was the so-called migration crisis, which peaked in 2015. In the USA, migration has been on the policy agenda throughout the entire decade but without a comparable defining event. Fourth, the attention given to climate change has accelerated throughout the decade. In 2015, the so-called Paris Agreement was signed, where the signatories committed to substantially reduce carbon emissions. Finally, some of the most serious epidemics measured by death toll include the Swine flu pandemic 2009–2010; the Ebola epidemic in Western Africa 2013–2016, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic. Taken together, such a policy agenda is presented in Table 1.

Diversity

A second pre-condition for relevance in a broader understanding has to do with the inclusion of a diverse set of voices. A field heavily skewed toward male authors may suffer from bias in terms of issues selected to examine and blind us to findings we might otherwise see. While there is a substantial body of literature that examines female representation, as well as female experiences in IR (Goddard 2017), less attention has been paid to security studies in this regard (Rost Rublee et al. 2020, p. 216). Previous literature has shown that female authors are underrepresented in the two major US security studies journals, International Security and Security Studies (Hoagland et al. 2020). No previous studies, however, have examined female authorship across the entire field of security studies, whether US and European security studies might differ in this regard, and the extent to which inequities have changed over time. Finally, it should also be emphasized that female inclusion in the discipline is an objective widely shared. In addition to gender, this paper examines the geographical location of authorship. It does so in order to examine the extent to which US and European security studies attract voices and thus experiences outside of their main geographical areas, whether any or both of the communities have changed over time, and whether the field as a whole has changed over time.

Intellectual pluralism

As a third and final pre-condition for relevance, the paper examines the intellectual pluralism of the field. Going back to John Stuart Mill, intellectual pluralism is often understood as a pre-condition for a healthy public sphere. Intellectual pluralism could thus be understood as a pre-condition for a relevant field, producing scholarship that might inform diverse audiences with different priorities, identities and interests (Keating and Della Porta 2010). Moreover, competing methods and approaches are likely to have different strengths and weaknesses and be more or less applicable to various research questions. And within the IR discipline as a whole, there is, as Maliniak et al. argue, widespread support for such pluralism (Maliniak et al. 2018, p. 454). John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt, for instance, advocate for preserving “a diverse theoretical ecosystem” as an antidote to what they perceive as “simplistic hypothesis-testing” (Mearsheimer and Walt 2013, pp. 430–31). Focusing more on method than theory, Michael Desch also professes the virtues of “methodological pluralism” (Desch 2019, p.250). Critical scholarship has a long-standing tradition of championing theoretical, as well as methodological, pluralism (Jackson 2016, pp.1–25), and major interpretivist scholars have recently advocated for theoretical and methodological pluralism (Jackson 2016; Guzzini 2020).

This paper breaks intellectual pluralism down into two categories: theoretical approach and method. A synthesis of textbooks used in the USA and Europe in IR and security studies would suggest that these are the approaches, summarized in Table 2, to be found.3 As for method, articles have been coded as qualitative, quantitative, none, or other.4

Table 2.

Theoretical approaches to the study of security with paradigmatic representatives

| Approach | Traditional | Constructivist | Critical |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Rationalist Realist Classical realist (Carr, Morgenthau, Herz) Defensive structural realist (Waltz) Neoclassical realist (Rose, Schweller) Offensive structural realism (Mearsheimer) Liberal (Ikenberry, Keohane, Nye, Martin, Moravscik) |

Securitization theory (Buzan, Waever) Constructivist (Wendt) Ontological security theory (Mitzen, Steele) Sociological Practice theory (Bourdieu) New Materialist (incl. STS/ANT/Assemblage theory) (Latour, Bennett, Jasanoff) |

Critical security studies Marxist/neo-Gramscian (Cox, Linklater) Post-structuralist Agambenian Butlerian Foucauldian Lacanian Zizekian Postcolonial/decolonial (Said, Spivak, Bhabha, Quijani, Lugones, Mignolo) Gender/feminist Critical Race Theory (CRT) |

Methods and material

The following three major journals, catering to the US security studies community, are included in this study: International Security, Security Studies, and Contemporary Security Policy.5 Moreover, three European security studies journals are included: Security Dialogue, European Journal of International Security, and European Security. All six journals describe themselves as focusing on security, and what they publish is understood as falling within the realm of security studies. Further, taken together, they represent the US and European security studies communities, respectively.6 By only including journals solely devoted to security studies, the demarcation criteria for what constitutes security studies are resolved: security studies is quite simply understood as what leading security studies journals publish. By way of delineating the field, journals associated with peace and conflict studies, such as the Journal of Peace Research and Journal of Conflict Resolution, are not included since peace and conflict studies is widely considered its own scholarly field (Bright and Gledhill 2018). Moreover, journals devoted to strategic studies, such as the Journal of Strategic Studies, have been excluded on similar reasoning. One should readily acknowledge that there are overlaps between security studies and strategic studies. Richard Betts, for instance, conceptualized strategic studies as a subfield within security studies (1997). Nevertheless, strategic studies is often conceptualized as a distinct field, which deals more narrowly with strategy either at the political or military level (Baylis and Wirtz 2019).

This paper has coded all articles in the six journals between 2010 and 2020. The time frame has been chosen so as to be able to discern trends over an extended period of time. Moreover, since the time period ended relatively recently, the findings will speak to the state of the contemporary field. As previously explained, the coding has been undertaken inductively and deductively.7 The dataset from which the paper draws includes 1048 articles in total, 572 in US journals, and 476 in European journals.8 In order to further enhance uniformity and avoid bias, only stand-alone research articles have been included. Thus, all special issues, special sections symposia, response pieces, and review articles have been excluded. The coding does not rely on abstracts and keywords. Instead, all articles have been examined in their entirety to ascertain a uniform coding of the material. Finally, to strengthen the reliability of the coding, the (sole) author of this paper has read them all.

Findings

In this section, the three dimensions of relevance are examined and discussed in turn.

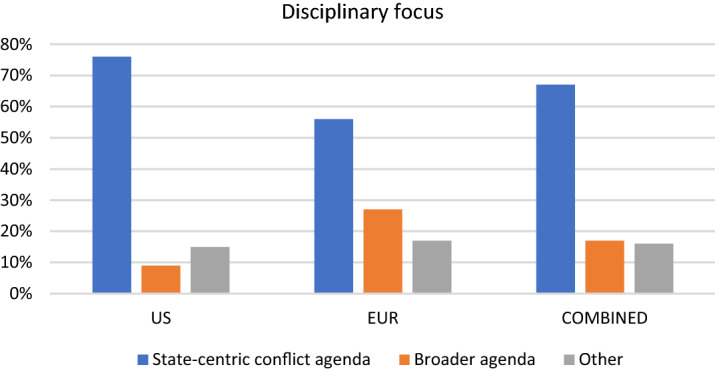

Responsiveness

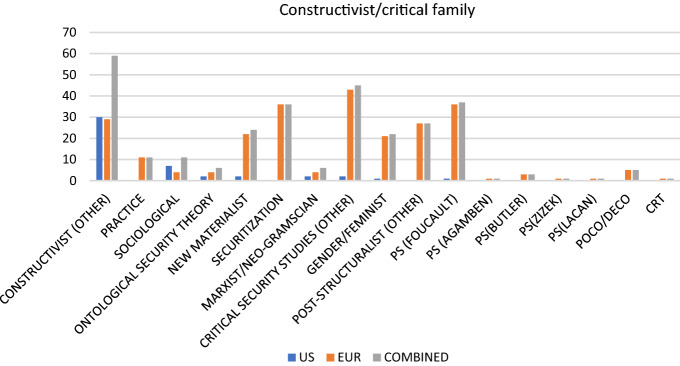

The results are presented as follows. First, and inductively, the broad contours of the field are presented. Second, and more deductively, the field’s responsiveness is examined with the aid of Table 1.To begin with the field as a whole, its output is first sorted into a traditional agenda, which focuses on pre-conflict, conflict, and post-conflict and tends to be state-centric, and a broader agenda, which goes beyond states and military conflict. Here, it is clear that a state-centric conflict agenda dominates quite strongly: 67% of the field deals with state-centric conflict and merely 17% with a broader agenda (Fig. 1). European security studies devotes considerably more attention to a broader agenda (27%) than US security studies (9%), though a majority of work within European security studies also focuses on state-centric conflict (56%).

Fig. 1.

Disciplinary focus

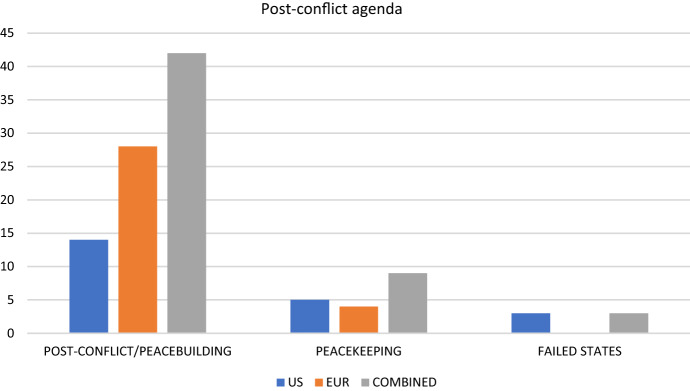

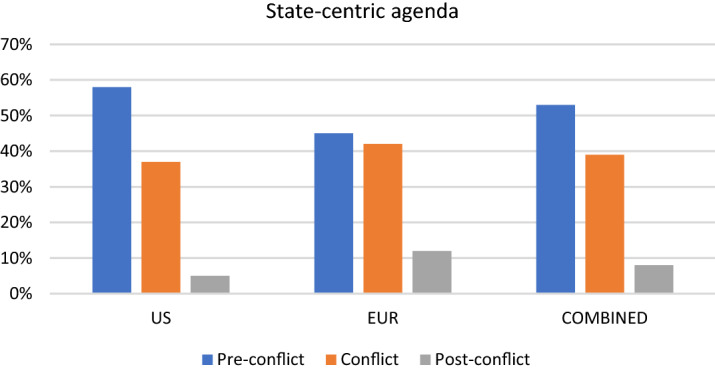

As a second step, the state-centric agenda is examined more closely (Fig. 2). To begin with, this scholarship is broken down into three phases: pre-conflict, conflict, and post-conflict. What is noteworthy is the field’s heavy emphasis on pre-conflict (53%) and conflict (39%), and its relative uninterest in post-conflict issues such as peace-building or peacekeeping (8%). European security studies takes a somewhat larger interest in post-conflict issues than US security studies (12% vs. 5%), although the difference is small. In this regard, the field arguably mirrors a policy agenda that is highly preoccupied with pre-conflict issues and, when conflict ensues, conflict itself, but relatively uninterested in what happens after a conflict has ended.

Fig. 2.

State-centric agenda

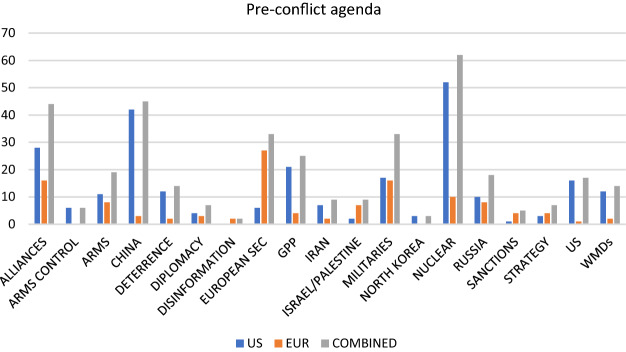

As a third step, the attention given to specific issues within the pre-conflict agenda is examined in more detail (Fig. 3). As a whole, the field’s top three issues include nuclear weapons, China, and alliances, which also coincide with the top three issues in US security studies. In European security studies, on the other hand, European security, militaries and alliances top the pre-conflict agenda. The top issue for the field, as a whole in the last decade, is familiar from Cold War security studies: nuclear weapons.

Fig. 3.

Pre-conflict agenda

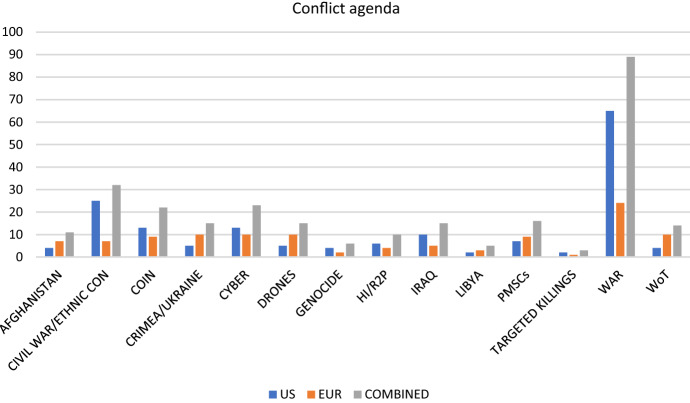

When it comes to the conflict agenda, it is harder to find any compelling trends, other than that war remains a top priority for the field (Fig. 4). When it comes to the post-conflict agenda, the field has taken an interest in peace-building, peacekeeping and failed states (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Conflict agenda

Fig. 5.

Post-conflict agenda

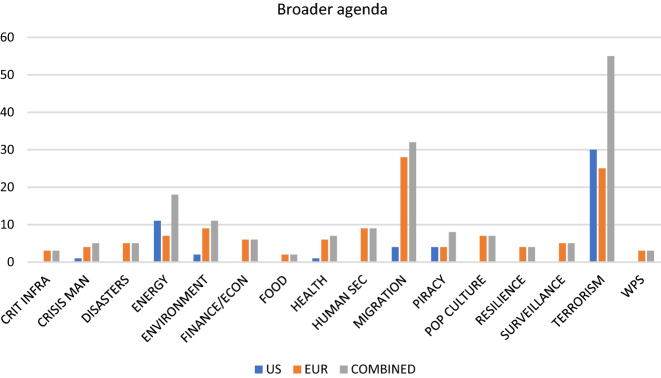

Next, the broader agenda is examined more closely (Fig. 6). Terrorism, migration, and energy security top the combined agenda. The US and the European agendas differ substantially. While terrorism tops the US agenda, migration tops the European one. And while European security studies has also taken a substantial interest in terrorism, US security studies has almost entirely neglected migration.

Fig. 6.

Broader agenda

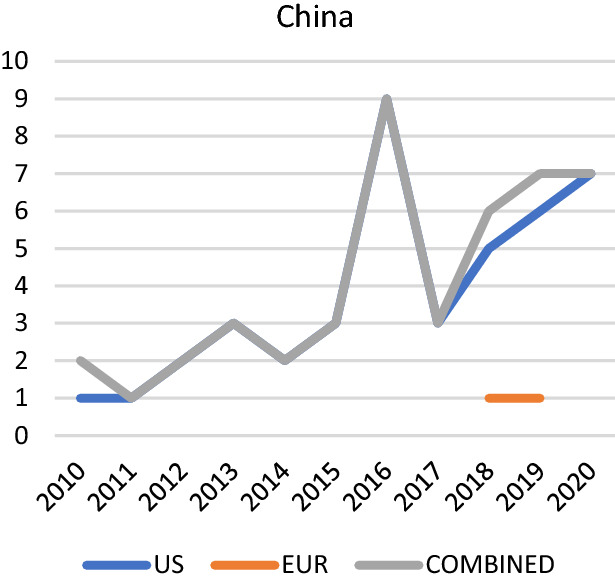

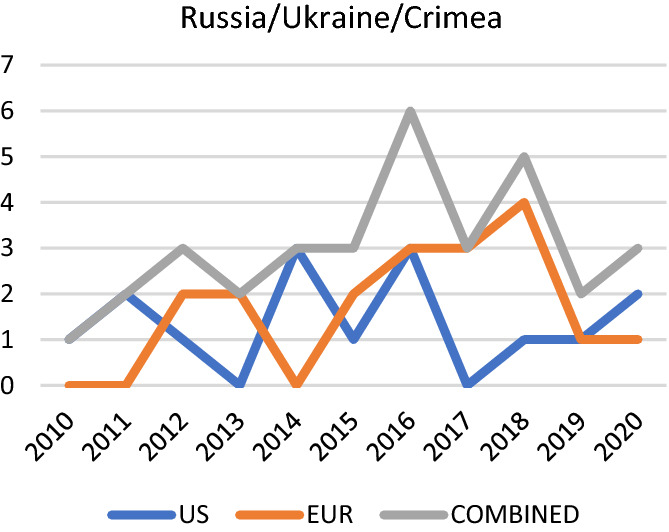

How then to examine the responsiveness of the field? To begin with, the extent to which the renewed attention to great power politics has had an impact on security studies is examined. First, US security studies has reflected an increased preoccupation with China (Fig. 7). In European security studies, however, what is often referred to as “the rise of China” has barely registered. This trend is broadly consistent with a European policy agenda, which, until recently, has been quite divided over whether to view China primarily as a security threat, or an economic partner. When it comes to Russia, there are also signs of responsiveness. Overall, security studies took a greater interest in issues pertaining to Russia, Ukraine, and Crimea after 2014, which is entirely consistent with a policy agenda (Fig. 8). What is noteworthy here is also that European security studies has taken a greater interest in Russia as compared to China, which is arguably also consistent with the policy agenda.

Fig. 7.

China

Fig. 8.

Russia/Ukraine/Crimea

Next, turning to the extent in which the scholarly agenda reflects technological developments, two issues were previously argued for as particularly important in the past decade: cybertechnology and AWS. European and US security studies have taken a roughly equal interest in cybertechnology (8% of discernible topics on a conflict agenda), whereas European security studies has taken a somewhat larger interest in AWS in the form of drones (5% of discernible topics dealing with a conflict agenda). There is no discernible trend over time for either of these issues. When it comes to technology, the most noteworthy finding is that nuclear weapons remain the number one issue on the pre-conflict agenda (17% of discernible topics on a pre-conflict agenda). However, scholarship on nuclear weapons is approximately five times more prevalent on the US security studies agenda as compared to European security studies.

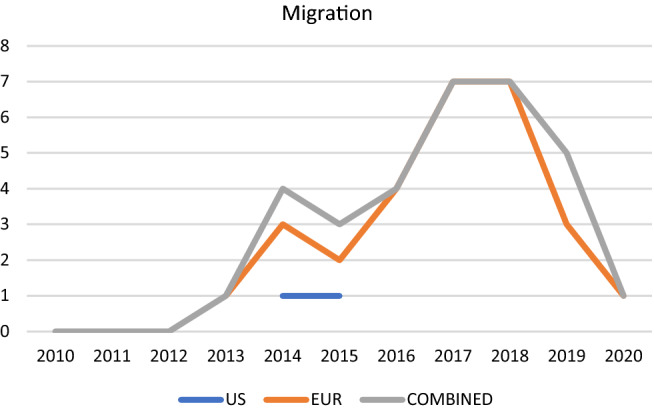

Finally, examining the extent to which the field has responded to key events, as noted above, terrorism tops the overall broader security studies agenda, but with no discernible trend over time. On the contrary, the global financial crisis, health, as well as the environment/climate change, barely register on the agenda of security studies. This is perhaps most noteworthy when it comes to climate change, which among Western policy-makers is sometimes presented as an existential threat to the survival of the planet. This finding is arguably even more surprising when it comes to European security studies, which is more receptive to a broader security agenda. However, European security studies appears to have responded to the migration crisis, which peaked in 2015 (Fig. 9). We see a clear spike in interest in migration after 2015 and a clear drop in interest in 2018. As previously noted, US security studies has almost completely ignored migration.

Fig. 9.

Migration

Diversity

Gender

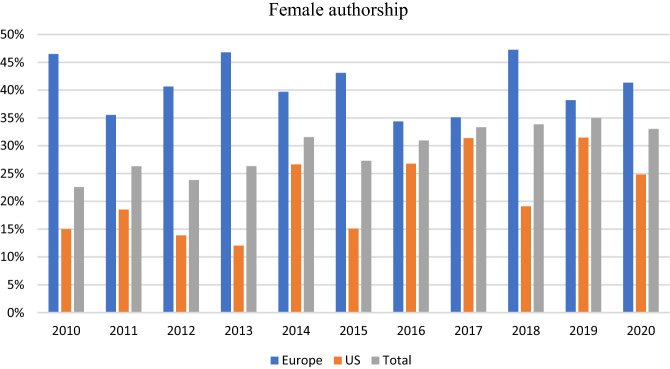

There are at least three noteworthy trends when it comes to gender diversity in security studies (Fig. 10). To begin with, the field as a whole is heavily male-dominated. The overall annual share of female authors in the last decade has varied between 23 and 34%, with a mean of 29%.9 There is, however, an overall slight trend toward a more equitable share of female authors. Second, European security studies has a substantially higher share of female authors, with a mean of 41%, than US security studies, with a mean of 21% (it has varied between 34 and 47% in Europe, and 12% and 31% in the USA). There is no discernible trend over the last decade. Third, US security studies has become slightly less male-dominated over the last decade, which also accounts for the overall trend. What is perhaps most noteworthy is the difference between European and US security studies in this regard. Whatever its reasons, European security studies has throughout the decade been more receptive to female scholars than US security studies.

Fig. 10.

Female authorship as %

Geographical distribution

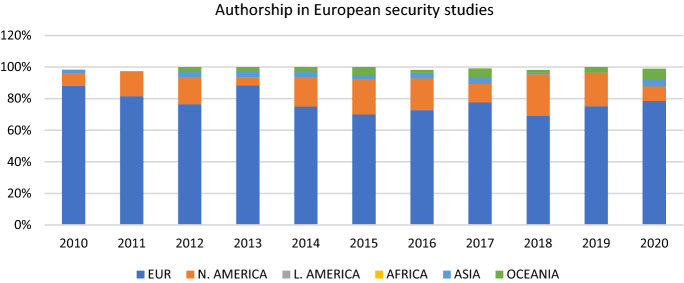

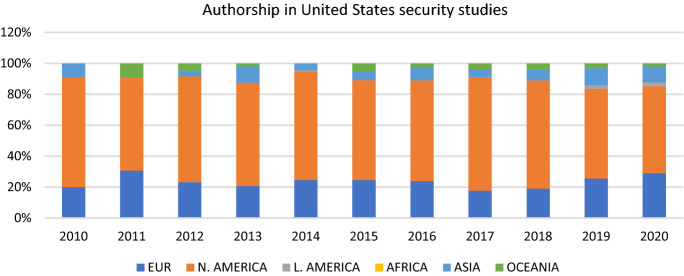

When it comes to the geographical distribution of authorship, it is of less interest to examine the discipline as a whole, since we already know that US and European scholars heavily dominate. What one may ask, however, is, first, whether European or US security studies is more open to scholars from outside Europe and the USA, and, second, whether one may detect any trends over time. When it comes to European security studies, the annual share of European authors has varied between 69 and 88%, with a mean of 78% (Fig. 11). The annual share of US-based authors in European journals has ranged between 5 and 26%, with a mean of 16%. Regarding authors based outside Europe and the USA, Oceania and Asia have had the highest share of representation, both with a mean of 3% throughout the decade. In the case of US security studies, the annual share of US-based authors has varied between 56 and 74%, with a mean of 66%, whereas the annual share of European authors has ranged between 18 and 31%, with a mean of 24% over time (Fig. 12). It thus appears that US security studies attracts a considerably higher proportion of non-US authors than European security studies. Asian-based authors, in particular, with a mean of 7%, are more often to be found in US security studies journals. However, there are no discernible trends over time either in US or European security studies in this respect.

Fig. 11.

Geographical distribution of authorship in European security studies

Fig. 12.

Geographical distribution of authorship in US security studies

Intellectual pluralism

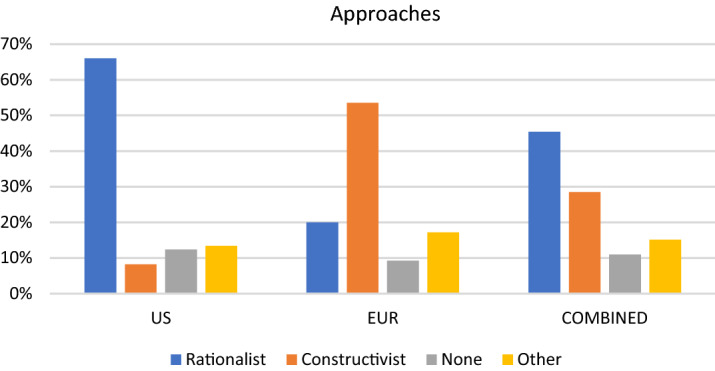

Theories

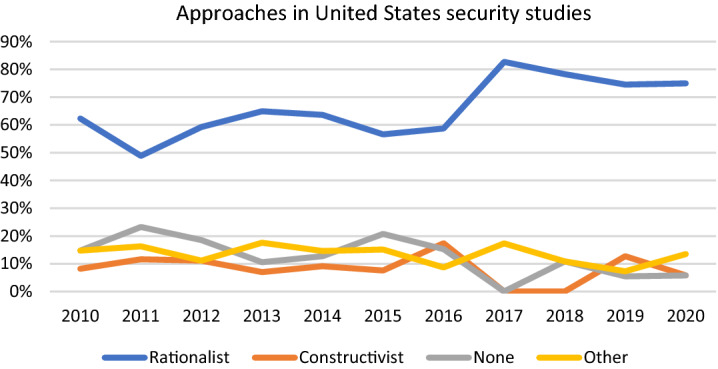

Scholarship is first divided into broad rationalist and constructivist camps, where constructivism also includes critical work (Fig. 13). As expected, rationalist work has dominated US security studies in the past decade, constituting some 66% of the total output. Constructivist/critical work makes up only some 8% of the total output in US-based journals. In European security studies, the situation is reversed, with some 54% constructivist and 20% rationalist scholarship. Overall then, a case could be made that there is greater intellectual pluralism to be found in European security studies than in its US counterpart.

Fig. 13.

Theoretical approaches

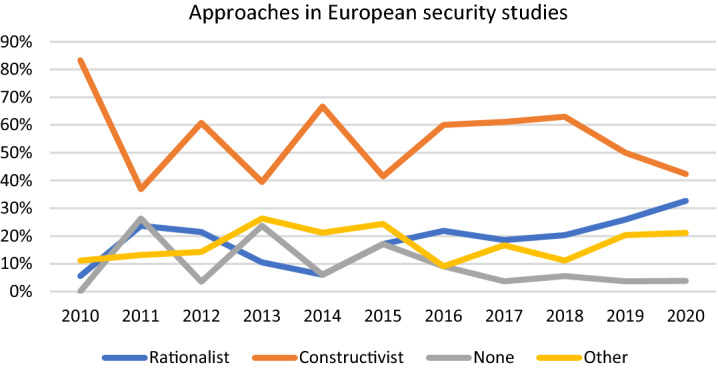

Further, it appears that European security studies is becoming increasingly theoretically diverse over time (Fig. 14), with the share of rationalist work increasing. There is no such trend in US security studies however, which, if anything, is becoming increasingly dominated by rationalist approaches (Fig. 15).

Fig. 14.

Theoretical trends in European security studies

Fig. 15.

Theoretical trends in US security studies

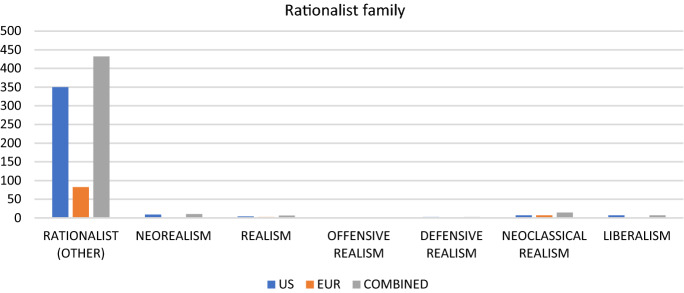

As a second step, when examining the rationalist family of approaches more closely, it becomes clear that work which explicitly uses realism is rare (Fig. 16). Instead, the vast majority of rationalist work consists of non-paradigmatic middle-range theorizing. When it comes to variants of realism, neoclassical realism is the most widely used strand of realism. In European security studies, scholarship which can be categorized as realist is virtually non-existent.

Fig. 16.

Rationalist family

Within the constructivist/critical10 family of theories, there is a greater number of discernible approaches. Among these, securitization theory, gender/feminist, and post-structural approaches have been particularly influential in European security studies, while these approaches barely register in US security studies. Among post-structuralist approaches, Foucauldian ones dominate (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17.

Constructivist/critical family

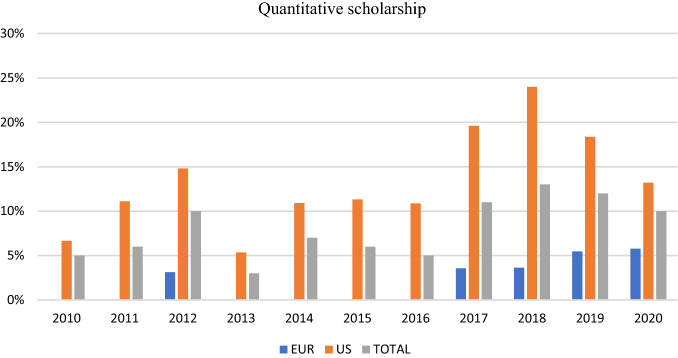

Method

When examining the second dimension of intellectual pluralism, it is evident that the field is heavily dominated by qualitative methods (Fig. 18). Overall, the percentage of quantitative articles (defined as articles which use regression analysis) in the field as a whole ranges from 3 to 13%, with a mean of 8%. When it comes to European security studies, quantitative work is rare, ranging from an annual share from 0 to 6%, with a mean of 2%. In US security studies, the percentage of quantitative work ranges from 5 to 24%, with a mean of 13%. There is a slight increase over time in scholarship which uses quantitative methods in US, as well as in European, security studies.

Fig. 18.

Quantitative scholarship

Conclusion

This paper has examined the field of security studies in the USA and Europe over the last decade against the background of widespread concerns pertaining to the field’s relevance. In face of much criticism for lacking in relevance, this paper has argued for a broader understanding of relevance, understood as the potential for scholarship to inform the world outside academia. The paper then argued that three important pre-conditions for exerting such relevance include responsiveness to external events, diversity of authorship, and intellectual pluralism. These dimensions are also broadly supported within the scholarly community. In the final analysis, the state of the field does not seem as bleak as to warrant the designation of a ‘cult of irrelevance.’ On the contrary, when security studies in the USA and security studies in Europe are taken into account, the field appears as a rather broad church.

To begin with responsiveness, evidence suggests that the discipline has responded to the world which it inhabits. US security studies has clearly responded to the increased preoccupation with China on the policy agenda, and European and US security studies took a greater interest in Russia following the Russo-Ukrainian War in 2014. The way in which the field has responded to technological developments is harder to discern, but cybersecurity and AWS have attracted some attention, although nuclear weapons remain by far the most widely studied security-related technology. Further, terrorism has remained at the top of the broader security agenda. Moreover, European security studies has clearly responded to the migration crisis in 2014, while migration has hardly been examined at all in US security studies. On the other hand, the security implications of climate change have received scant attention, which is most surprising when it comes to European security studies, which is more welcoming to a broader security agenda.

In terms of diversity, the discipline as a whole remains dominated by male scholars, with a mean of 71%. The overall trend, however, is in a slightly more equitable direction. The difference between US and European security studies is striking, with the latter showing a much more equitable share of female authors (mean = 41%) than the former (mean = 21%). This finding calls into question the prevailing perception of security studies as a highly male-dominated field, which does not seem to be the case in Europe. In terms of the geographical distribution, US security studies is decidedly more receptive to authors based in other Western and non-Western countries (mean = 66% US-based authors) than European security studies, which largely remains an intra-European affair (mean = 78% European-based authors). There are many possible reasons for this, one being that the US security studies community remains the most important to the rest of the world.

Finally, when it comes to intellectual pluralism, rationalist scholarship has dominated in the USA, while constructivist/critical scholarship has dominated in Europe over the last decade. On the whole, however, European scholarship is more intellectually diverse than US security studies, and there is a slight trend in European security studies to become even more intellectually diverse. In US security studies, there is no such trend. Perhaps the most striking finding is how little scholarship is rooted in realism even when it comes to the US security studies community, confirming the findings of previous work on the increase in non-paradigmatic scholarship (Hoagland et al. 2020). Among contending realisms, neoclassical realism is the most widely employed. On the second dimension of intellectual pluralism, European security studies appears as an intellectual monoculture, with a tiny share of quantitative scholarship (mean = 2%). US security studies, while dominated by qualitative work, is more receptive to quantitative work (mean = 13%). Over time, however, there is a small overall trend toward a higher share of quantitative work. What is noteworthy here is that the basis for the concern that Desch has articulated, namely that quantitatively oriented work has a tendency to produce methodologically driven, and thereby less policy-relevant scholarship, largely vanishes (Desch 2015). Even if Desch’s assessment about quantitatively oriented work is correct, security studies as a whole remains, with a mean of 8% quantitatively oriented work, overwhelmingly qualitative.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Tom Lundborg and Mark Rhinard for extensive and insightful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. For helpful feedback, the author is also indebted to Antoine Bousquet, Kjell Engelbrekt, Linus Hagström, Ronnie Hjort, Dan Öberg, as well as two anonymous reviewers. The usual disclaimer applies.

Stefan Borg

is Associate Professor in Political Science in the Department of Political Science and Law, Swedish Defence University. His research interests include international security, Transatlantic relations and international political theory.

Footnotes

See https://trip.wm.edu.

These issues have often been described as the most important crises in the 2010s. See for instance Rhinard (2019).

It is sometimes hard to determine whether an article implicitly uses a qualitative method, or whether no method is in fact used. In order to facilitate coding, quantitative work is here defined as work which uses regression analysis. It should, therefore, be noted that pieces that solely rely on descriptive statistics are left out.

A caveat should here be added. Contemporary Security Policy has been included as representative of the US security studies community despite the fact that it has been edited from a European university since 2017 and that a majority of the members of the editorial board are currently based outside of the USA. This, however, is a fairly recent development, and for the time period 2010–2020, CSP would arguably still best be seen as representative of US security studies.

Journal of Global Security Studies has been excluded since it would be hard to categorize it either as mainly representative of US or European security studies. The only European security studies journal which is not included is Critical Studies on Security, which, unlike the ones included, lacks an impact factor in the period examined.

When it comes to coding of the substantive issues, each article has been assigned only to one category, the one determined to be the most important for the piece as a whole.

The dataset, which also includes further description of the coding, is available online at https://fhs.academia.edu/StefanBorg.

Co-authored articles are counted as 0.5 or less depending on the number of authors.

Rationalist here denotes scholarship subscribing to an objectivist ontology and does not fall under any of the other categories.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Altmann J, Sauer F. Autonomous Weapon Systems and Strategic Stability. Survival. 2017;59(5):117–142. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2017.1375263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch B, Medeiros E, Schnell O, Shambaugh D, Stanzel V. Dealing with the Dragon. China as a Transatlantic Challenge. Washington, D.C.: George Washington University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baylis J, Wirtz J. Introduction: Strategy in the Contemporary World. In: Baylis J, Wirtz J, Gray CS, editors. Strategy in the Contemporary World An Introduction to Strategic Studies. 6. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2019. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Baylis J, Smith S, Owens P, editors. The Globalization of World Politics. Oxford: OUP; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Betts R. Should Strategic Studies Survive? World Politics. 1997;50(1):7–33. doi: 10.1017/S0043887100014702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black JL, Johns M, editors. The Return of the Cold War. Ukraine, The West and Russia. London: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Booth K. Security and Emancipation. Review of International Studies. 1991;17(4):313–326. doi: 10.1017/S0260210500112033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bright J, Gledhill J. A Divided Discipline? Mapping Peace and Conflict Studies. International Studies Perspectives. 2018;19(2):128–139. doi: 10.1093/isp/ekx009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bush R, Hass R. The China Debate is Here to Stay. Washington, D.C.: Brookings; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Buzan B. An Introduction to Strategic Studies. Military Technology and International Relations. London: The Macmillan Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Buzan B, Hansen L. The Evolution of International Security Studies. Cambridge: CUP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, editor. Contemporary Security Studies. 5. Oxford: OUP; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Desch M. Technique Trumps Relevance: The Professionalization of Political Science and the Marginalization of Security Studies. Perspectives on Politics. 2015;13(2):377–393. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714004022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desch M. Cult of the Irrelevant: The Waning Influence of Social Science on National Security. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson J. On the Policy Relevance of Grand Theory. International Studies Perspectives. 2014;15(1):94–108. doi: 10.1111/insp.12008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2013. Cyber Security Strategy of the European Union: an Open, Safe and Secure Cyberspace. European Union, 14th June 2013.

- Goddard, S. 2017. Introduction. In S. Goddard, D. Avant, M. C. Desch, W. C. Wohlforth, S. M. Lynn-Jones, eds. Policy Forum on the Gender Gap in Political Science. H-Diplo, September 22th.

- Guzzini S. Embrace IR Anxieties (or, Morgenthau’s Approach to Power, and the Challenge of Combining the Three Domains of IR Theorizing) International Studies Review. 2020;22(2):268–288. doi: 10.1093/isr/viaa013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland J, Oakes A, Parajon E, Peterson S. The Blind Men and the Elephant: Comparing the Study of International Security Across Journals. Security Studies. 2020;29(3):393–433. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2020.1761439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, M. 2015. What is Policy Relevance? War on the Rocks.

- Jackson PT. The Conduct of Inquiry in International Relations. Philosophy of science and its implications for the study of world politics. 2. London: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jentleson BW, Ratner E. Bridging the Beltway-Ivory Tower Gap. International Studies Review. 2011;13(1):6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2486.2010.00992.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keating M, Della Porta D. In Defence of Pluralism in the Social Sciences. European Political Science. 2010;9(4):111–120. doi: 10.1057/eps.2010.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lebow RN, Risse-Kappen T, editors. International Relations Theory and the End of the Cold War. New York: Columbia University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Maliniak D, Peterson S, Powers R, Tierney MJ. Is International Relations a Global Discipline? Hegemony, Insularity, and Diversity in the Field. Security Studies. 2018;27(3):448–484. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2017.1416824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mearsheimer J, Walt S. Leaving Theory Behind: Why Simplistic Hypothesis Testing is Bad for International Relations. European Journal of International Relations. 2013;19(3):427–457. doi: 10.1177/1354066113494320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oren I. How Can We Make Political Science Less Techno-Centric? Widen Rather than Narrow its Distance from the Government. Perspectives on Politics. 2015;13(2):394–395. doi: 10.1017/S153759271500016X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peoples C, Vaughan-Williams N. Critical Security Studies: An Introduction. London: Routledge; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rhinard M. The Crisisification of Policy-making in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies. 2019;57(3):616–633. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rost Rublee M, Jackson EB, Parajon E, Peterson S, Duncombe C. Do You Feel Welcome? Gendered Experiences in International Security Studies. Journal of Global Security Studies. 2020;5(1):216–226. doi: 10.1093/jogss/ogz053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singer PW, Friedman A. Cybersecurity and Cyberwar. What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford: OUP; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sjoberg L. Locating relevance in security studies. Perspectives on Politics. 2015;13(2):396–398. doi: 10.1017/S1537592715000171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tikk E, Kerttunen M, editors. Routledge Handbook of International Cybersecurity. London: Routledge; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Waever O. The Sociology of a Not So International Discipline: American and European Developments in International Relations. International Organization. 1998;52(4):687–727. doi: 10.1162/002081898550725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walt SM. The Renaissance of Security Studies. International Studies Quarterly. 1991;35(2):211–239. doi: 10.2307/2600471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walt SM. Rigor or Rigor Mortis: Rational Choice and Security Studies. International Security. 1999;23(4):5–48. doi: 10.1162/isec.23.4.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walt, S. M. 2009. The Cult of Irrelevance. Foreign Policy, 15 April.