1. Introduction

The United States faces an ongoing drug crisis, with more than 20 million Americans living with a substance use disorder (SUD) (CBHSQ, 2017) and record-high overdose deaths in recent years (CDC, 2021). The vast majority of individuals with SUD do not receive needed treatment and financial factors, including inadequate insurance coverage of treatment, are among the barriers to treatment access (Barry, Epstein, Fiellin, Fraenkel, & Busch, 2016; SAMHSA, 2021). Connecting individuals who have SUD with effective treatment can have ripple effects on wellbeing and health within the family (Lander, Howsare, & Byrne, 2013; Winstanley & Stover, 2019; Young, Kline-Simon, Mordecai, & Weisner, 2015), necessitating the consideration of family context when evaluating the impact of insurance and financing policies on populations with SUD.

Prior work has not investigated the distribution of health care spending across members of families in which at least one member has a SUD. On one hand, spending may be concentrated in the family member with SUD, reflecting broader patterns of heightened spending among persons with SUD, although this may vary by type of SUD (Gryczynski et al., 2016); higher levels of spending among persons with SUD are attributable not just to SUD-specific treatment but to care for the comorbidities that often accompany SUD (Thorpe, Jain, & Joski, 2017). On the other hand, given that SUD is undertreated relative to other chronic conditions (Barry et al., 2016; SAMHSA, 2018), spending may be concentrated among family members without SUD but with other serious, chronic conditions. Understanding the distribution of spending within families can shed light on how policies that impact individuals with a SUD may impact the total health care spending of a family.

As the overdose crisis has accelerated in the U.S., high deductible health plans (HDHPs) have become an increasingly prevalent product on the commercial insurance market. From 2016 to 2019, the percent of private sector enrollees with family coverage enrolled in an HDHP rose from 44.4% to 53.5% (AHRQ, 2021). The rising cost of health insurance has attracted employers to HDHPs, which are generally less expensive than other plans (Arnold & Whaley, 2020; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021; Westrich & Huff, 2022). While individuals enrolled in HDHPs have lower overall health care spending (Agarwal, Mazurenko, & Menachemi, 2017; Buntin, Haviland, McDevitt, & Sood, 2011; Eisenberg, Matthew D., Du, Sen, Kennedy-Hendricks, & Barry, 2020; Rabideau, Eisenberg, Reid, & Sood, 2021; Wharam et al., 2007), these plans are associated with delayed or foregone care (Agarwal et al., 2017; Mazurenko, Buntin, & Menachemi, 2019), especially among families where at least one member has a chronic condition (Galbraith et al., 2012). This is particularly concerning in the context of treating SUD, which is best treated in a chronic condition framework that includes consistent engagement with the healthcare system (McLellan, Lewis, O’Brien, & Kleber, 2000; Schuckit, 2016). Further, among individuals who have self-identified a need for SUD treatment, costs are cited as the most prevalent barrier to treatment (SAMHSA, 2021). Recent evidence has shown that HDHPs lead to reductions in the use of SUD-related services for individuals with single coverage (Eisenberg, M. D. et al., 2022; Schilling, C. et al., 2020). Given the rise in family enrollment in HDHPs (AHRQ, 2021) and the evidence that HDHPs may affect the utilization of all family members (Buntin et al., 2011), especially in families with chronic conditions (Galbraith et al., 2012), there is a need to study the impact of HDHPs on families with a member with a SUD.

In this paper, we first summarize the characteristics of families who have a member with a SUD and provide new details on the distribution of health care spending within these family units. We then estimate the association between HDHPs and family health care spending overall, total spending for the individual with a SUD, total spending for other members of the family, and family spending on SUD-related services, specifically. Finally, we evaluate whether the impact of the HDHP varies by which member of the family has a SUD (i.e., the policyholder, spouse, young adult dependent, or child dependent).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. DATA

We conducted secondary data analysis of de-identified administrative claims and enrollment data from the OptumLabs® Data Warehouse for the years 2007 to 2017 (OptumLabs, 2021). These data included medical, behavioral health (encompassing claims for substance use disorder and mental health services), and pharmaceutical claims, and plan benefit design characteristics, including the annual family deductible level. Policyholders were linked to spouses and dependents enrolled in their plan through family identifiers. In addition, the data contained identifiers for each group of enrollees offered the same set of plans by their employer. Using this variable, we identified unique employers in the data to track changes in employer plan offerings over time. We identified exposure to HDHPs at the employer- rather than the family-level to minimize risk of bias due to family selection into HDHPs (McDevitt et al., 2014). These data have commonly been used in prior work to assess the impact of HDHPs on health care utilization and expenditures (Eisenberg, Matthew D. et al., 2020; Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2021; Schilling, Cameron J. et al., 2021).

2.2. SAMPLE SELECTION

We used a multi-stage process to identify our study sample where the unit of analysis is the “family-year,” a unique combination of family units and calendar year. The sample selection proceeded in three broad steps (Appendix A): 1) inclusion of enrolled family units, 2) identifying “treatment” and “comparison” employers providing insurance to these eligible enrollees, and 3) inclusion of families that had a member with a SUD.

First, we included enrollee-years ages 12–64 years with at least 11 months of continuous enrollment within the year in medical, behavioral health, and pharmacy coverage. We linked individuals to family members enrolled in the same plan and limited the sample to those in a family with at least two members (77.4% of person-years). Individuals were classified as policyholders, spouses, young adult dependents (age 18–26), and child dependents (age 12–17).

Second, we identified treatment and comparison groups at the employer-level providing insurance to the sample of eligible family-years from the above step. Employers with year-to-year changes in total enrollment exceeding 50% were excluded (16.6% of employer-years and 9% of person-years from the sample). This step ensured that there were no large changes in enrollment due to employees switching to plans offered under different carriers not observed in our data.

Among the remaining employers, we then identified treatment and comparison employers based on year-to-year changes in families enrolled in HDHPs within each employer over time. Consistent with previous research (Eisenberg, M. D. et al., 2022; Schilling, C. et al., 2020), we designated plans as HDHPs if they exceeded the deductible threshold set by the IRS for family plans (e.g., $2,700 in 2017, averaging $2,427 over study period) (IRS, 2018). Treatment employers were employers with at least one year with less than 5% of families enrolled in HDHPs, directly followed by at least one year with greater than 5% of family enrollment in HDHPs. Following prior work (Eisenberg, M. D. et al., 2022; Eisenberg, Matthew D., Haviland, Mehrotra, Huckfeldt, & Sood, 2017; Haviland, Eisenberg, Mehrotra, Huckfeldt, & Sood, 2016; Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2021; Schilling, Cameron J. et al., 2021), we selected a threshold of 5% to represent a meaningful proportion of all families enrolled in an HDHP, while allowing for results to be generalizable to families receiving coverage through employers with a broad range of HDHP enrollment (from 5% to 100%). It is possible, however, that employers in the control group may have offered HDHPs with no associated enrollment, in which case the HDHP offer would have no impact on utilization. Comparison employers were identified as employers with consistent 0% family enrollment in HDHPs for all years in the data.

Third, among families who receive coverage through either a treatment or comparison employer, we identified the subset of families with a member diagnosed with SUD. We identified individuals with SUD by the presence of at least one claim associated with a SUD diagnosis in any diagnostic code position, as in previous work (Barry et al., 2015; Busch, Frank, Lehman, & Greenfield, 2006). After this initial diagnosis, individuals were coded as having a SUD for all subsequent years that they appeared in the data, given the chronic nature and undertreatment of SUDs (Barry et al., 2016; McLellan et al., 2000; SAMHSA, 2018; Schuckit, 2016). SUD diagnosis codes included International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes 291, 292, 303, 304, and 305 (excluding 305.1 tobacco use disorder and 305.8 antidepressant abuse) and ICD-10-CM codes F10-F19 (excluding F17.2x tobacco use disorder). The final analytic sample included only individuals with a SUD and their family members enrolled in the same plan. Families with multiple members with a SUD were excluded to ease interpretation of analyses (11% of families with any members with an SUD).

2.3. MEASURES

The key independent variable was whether an HDHP was offered by the employer to the family each year. This indicator took a value of 1 if over 5% of family enrollees at an employer were enrolled in an HDHP in each year and 0 otherwise. To control for time invariant unobserved differences in employers and secular trends, respectively, our models included employer and year fixed effects.

We constructed all outcome measures at the family-year level. Within each family-year, we calculated total and out-of-pocket (OOP) family health care spending, total and OOP health care spending for the member with SUD, total and OOP health care spending on SUD services, and total and OOP health care spending for all other family members without a SUD. SUD-related services included those with a primary diagnosis of SUD (as defined of above) or a secondary diagnosis of SUD with a primary diagnosis for a mental health condition (ICD-9-CM codes 295–299, 300–302, 306–309, 310–314 and ICD-10-CM codes F2-F9 and F84).

We included additional family- and enrollee-year level demographic and clinical characteristics as covariates in our regression models. Demographic variables included the documented age, sex, and race/ethnicity of the policyholder (Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, or unknown), the number of family members, the role of the family member with SUD (policyholder, spouse, young adult dependent, or child dependent), household income (<$40k, >=$40k & <$75k, >=$75k and <$125k, >=$125k and <$200k, >$200k, or unknown), Census block median education (less than high school, high school, some college, Bachelor’s or more, unknown), and Census division. Additionally, we constructed 47 chronic condition indicator variables based on the Chronic Conditions Warehouse and generated binary indicators for if any member of the family had the condition and zero otherwise.(Condition categories.)

2.4. STATISTICAL ANALYSES

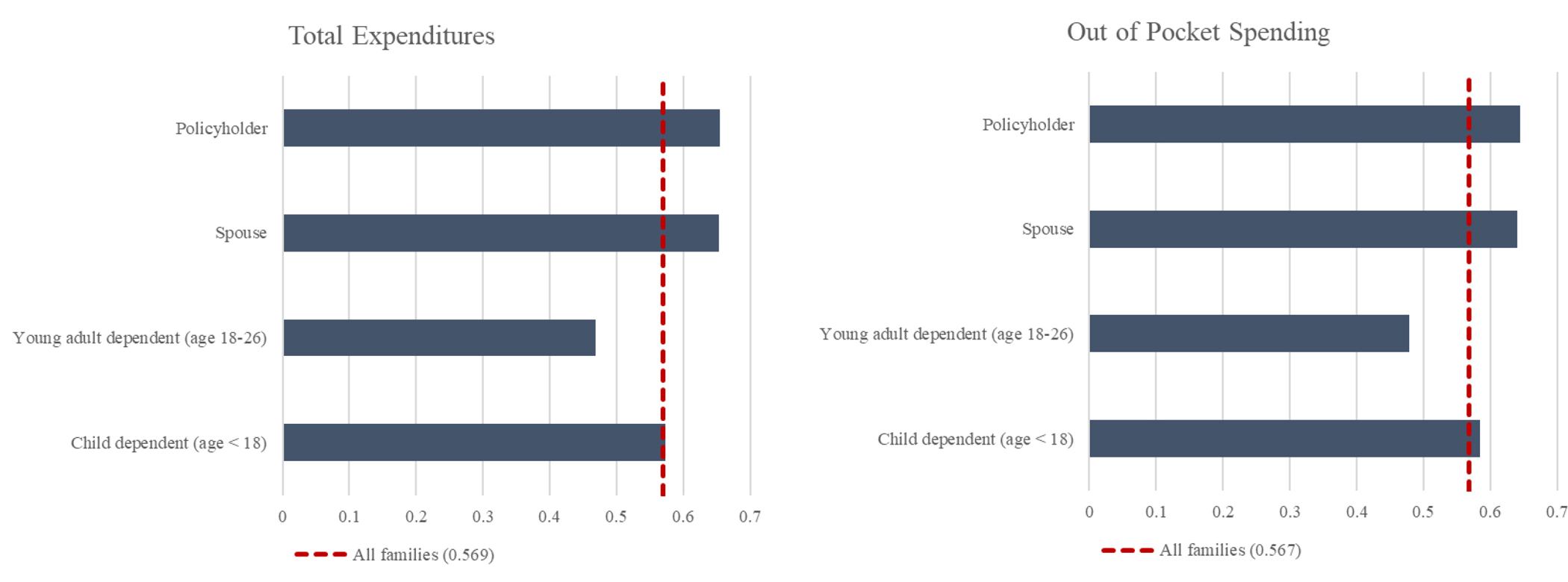

To describe the balance of covariates between families at treatment and comparison employers, we summarized continuous measures with means and standard deviations and categorical (or binary) measures with counts and percentages. For each variable, we calculated standardized mean differences to examine differences among families in our treatment and comparison groups (Table 1). We then summarized the proportion of family out-of-pocket and total health care spending on the member with a SUD and stratified this analysis based on the role of the family member with a SUD (Figure 1).

Table 1:

Unadjusted Descriptive Characteristics of Families Offered and Not Offered a High-Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) Across Family-Years, 2007–2017

| Offered an HDHP | Not offered an HDHP | Standardized mean difference (SMD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Documented age of policyholder, mean (SD) | 47.8 (8.6) | 47.1 (8.8) | 0.077 |

| Documented sex of policyholder, % | |||

| Male | 102,534 (58.6%) | 91,244 (64.1%) | 0.114 |

| Female | 72,535 (41.4%) | 51,040 (35.9%) | |

| Documented race/ethnicity of policyholder, n (%) | |||

| White | 125,684 (71.8%) | 100,632 (70.7%) | 0.024 |

| Black | 17,025 (9.7%) | 12,059 (8.5%) | 0.043 |

| Hispanic | 14,428 (8.2%) | 13,496 (9.5%) | 0.044 |

| Asian | 3,874 (2.2%) | 3,114 (2.2%) | 0.002 |

| Missing/Unknown | 14,058 (8.0%) | 12,983 (9.1%) | 0.039 |

| Number of family members, n (%) | |||

| 2 | 55,001 (31.4%) | 45,514 (32.0%) | 0.012 |

| 3 | 43,040 (24.6%) | 34,768 (24.4%) | 0.003 |

| 4 | 47,218 (27.0%) | 37,458 (26.3%) | 0.015 |

| 5 | 29,810 (17.0%) | 24,544 (17.3%) | 0.006 |

| Family member with SUD, n (%) | |||

| Policyholder | 53,401 (30.5%) | 46,730 (32.8%) | 0.050 |

| Spouse | 59,701 (34.1%) | 46,499 (32.7%) | 0.030 |

| Young adult dependent (age 18–26) | 51,715 (29.5%) | 38,739 (27.2%) | 0.051 |

| Child dependent (age < 18) | 10,252 (5.9%) | 10,316 (7.3%) | 0.056 |

|

| |||

| Family-years, N | 175,069 | 142,284 | |

Notes: Select family characteristics are shown for families with a member with a SUD at treatment and comparison employers (additional characteristics show in Appendix B). All measures were constructed from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse for the years 2007 to 2017. Standardized mean differences are calculated as the difference between the means in treatment and comparison groups divided by the pooled standard deviation, weighted by the sample size of each group.

Figure 1: Proportion of Family Total and Out-of-Pocket Spending on Member with a SUD by Family Member Role in Families of Three, 2007–2017.

Notes: Proportions of total and out-of-pocket expenditures by family member with a SUD are shown, stratified by which member of the family had a SUD. Mean proportions regardless of family role are shown in red dotted lines. All measures were constructed from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse for the years 2007 to 2017 and are pooled across families enrolled in plans offered by treatment and control employers.

To measure the relationship between the HDHP offer and health care spending, we estimated difference-in-differences models at the family-year level with fixed effects for employers and years, respectively. The relationship was therefore estimated as the average difference in the change in family health care spending among families at treatment employers before vs. after the HDHP offer compared to the change in family health care spending over time among families at comparison employers. This relationship was estimated by the coefficient on our key independent variable of whether an HDHP was offered in each year at a family’s employer (Table 2). Additionally, to evaluate if the relationship varied by which member of the family had a SUD, the key independent variable was interacted with a variable specifying if the individual in the family with a SUD was the policyholder, spouse, young adult dependent (age 18–26), or child dependent (age 12–17; Table 3).

Table 2:

Relationship between HDHP Offer and Total Family Health Care Spending

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total family health care spending | Health care spending for member with SUD | Health care spending for other members | Spending on SUD services | |

|

| ||||

| Average percentage point change in probability of any spending (95% CI) attributable to HDHP offer | ||||

| Post X Treatment | −0.014 (−0.031, 0.004) | −0.014 (−0.031, 0.003) | −0.015* (−0.031, 0.001) | −0.024*** (−0.038, −0.010) |

| Observations | 317,353 | 317,353 | 317,353 | 317,353 |

| R-squared | 0.246 | 0.111 | 0.218 | 0.143 |

| Pre-HDHP offer mean | 0.990 | 0.949 | 0.902 | 0.392 |

|

| ||||

| Average change in conditional spending (95% CI) attributable to HDHP offer | ||||

| Post X Treatment | −1,545.78*** (−2,270.86, −820.70) | −1,184.79*** (−1,844.79, −525.20) | −359.00*** (−602.32, −115.68) | 72.52 (−153.35, 298.38) |

| Observations | 313,859 | 298,740 | 287,879 | 108,431 |

| R-squared | 0.366 | 0.259 | 0.262 | 0.167 |

| Pre-HDHP offer mean | 20,226 | 13,826 | 7,655 | 3,724 |

Notes: The relationship between the family HDHP offer and the probability of any spending and spending, conditional on any spending are shown. Post X Treatment coefficients were calculated a difference-in-differences framework comparing families at treatment (HDHP offer) vs. comparison employers (no HDHP offer) with employer and year fixed effects. All models were adjusted for the documented age, sex, and race/ethnicity of the policyholder, family income and median Census block education levels, the number of family members, and the presence of chronic conditions among any family member derived from the Chronic Conditions Warehouse (CCW) methodology. Probability of any spending were modeled as linear probability models. Spending, conditional on any spending, was log-transformed and coefficient estimates were exponentiated to obtain relative spending coefficients. Pre-HDHP offer means were calculated among families at treatment employers prior to the HDHP offer. All measures were constructed from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse for the years 2007 to 2017.

Table 3:

Relationship between HDHP Offer and Total Family Health Care Spending, by Which Member has a SUD

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total family health care spending | Health care spending for member with SUD | Health care spending for other members | Family spending on SUD services | |

|

| ||||

| Average percentage point change in probability of any spending (95% CI) attributable to HDHP offer | ||||

| Post X Treatment | −0.018* (−0.037, 0.002) | −0.016 (−0.036, 0.004) | −0.016* (−0.034, 0.002) | −0.025*** (−0.040, −0.010) |

| Post X Treatment X Member with SUD (ref. = policyholder) | ||||

| Spouse | 0.005** (0.001, 0.009) | 0.006 (−0.005, 0.018) | 0.001 (−0.009, 0.012) | 0.004 (−0.007, 0.016) |

| Adult dependent | 0.006** (0.001, 0.011) | −0.004 (−0.013, 0.005) | −0.000 (−0.009, 0.009) | −0.004 (−0.017, 0.010) |

| Child dependent | 0.009* (−0.000, 0.019) | 0.015* (−0.002, 0.031) | 0.002 (−0.011, 0.015) | 0.002 (−0.020, 0.023) |

| Observations | 317,353 | 317,353 | 317,353 | 317,353 |

| R-squared | 0.246 | 0.120 | 0.237 | 0.155 |

| Pre-HDHP offer mean | 0.990 | 0.949 | 0.902 | 0.392 |

|

| ||||

| Average change in conditional spending (95% CI) attributable to HDHP offer | ||||

| Post X Treatment | −1,648.95*** (−2,862.00, −435.90) | −948.63 (−2,464.79, 567.54) | 592.16*** (−1,015.07, −169.25) | −110.20 (−457.84, 237.44) |

| Post X Treatment X Member with SUD (ref. = policyholder) | ||||

| Spouse | −508.12 (−2,046, 1,029.87) | −811.57 (−3,030.66, 1,407.52) | 518.46* (−79.08, 1,116.01) | −50.51 (−395.45, 294.43) |

| Adult dependent | 579.81 (−588.31, 1,747.94) | −388.99 (−2,216.08, 1,438.10) | 222.28 (−241.92, 686.48) | 668.20*** (211.61, 1,124.79) |

| Child dependent | 1,265.73 (−557.41, 3,088.87) | 2,001.70 (1,022.68, 5,026.08) | −121.72 (−847.47, 604.02) | 44.25 (−457.94, 546.44) |

| Observations | 313,859 | 298,740 | 287,879 | 108,431 |

| R-squared | 0.371 | 0.267 | 0.287 | 0.178 |

| Pre-HDHP offer mean | 20226 | 13826 | 7655 | 3724 |

Notes: The relationship between the family HDHP offer and the probability of any spending and spending, conditional on any spending are shown. Post X Treatment coefficients were calculated a difference-in-differences framework comparing families at treatment (HDHP offer) vs. comparison employers (no HDHP offer) with employer and year fixed effects. Post X Treatment X Member with SUD coefficients were estimated by interactions Post X Treatment with which member of the family had a SUD, with the policyholder as the reference group. All models were adjusted for the documented age, sex, and race/ethnicity of the policyholder, family income and median Census block education levels, the number of family members, and the presence of chronic conditions among any family member derived from the Chronic Conditions Warehouse (CCW) methodology. Probability of any spending were modeled as linear probability models. Spending, conditional on any spending, was log-transformed and coefficient estimates were exponentiated to obtain relative spending coefficients. Pre-HDHP offer means were calculated among families at treatment employers prior to the HDHP offer. All measures were constructed from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse for the years 2007 to 2017.

Family health care spending outcomes were modeled in two parts. First, we modeled whether a family had any health care spending using linear probability models (LPM). Then, we modeled the log-transformed health care spending conditional on having any health care spending and computed marginal effects. Marginal effects were corrected for potential bias resulting from the reverse transformation (i.e., exponentiation) of the coefficient by multiplying the exponentiated coefficient estimate by the exponentiated variance of the errors over two.(Wooldridge, 2010) Standard errors were clustered at the employer level to account for unobservable correlation in health care spending for families within each firm.

2.5. SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to address key potential limitations in our study design. To address the limitations of our difference-in-differences study design we first assessed balance in demographic and clinical characteristics between families at treatment vs. comparison employers (Table 1, Appendix B). Second, we estimated event study models to assess differences in pre-HDHP offer trends in the outcome measures and treatment heterogeneity over time (Appendix C–D). Fourth, to address concerns raised in the recent literature regarding underlying heterogeneity across treated units in the estimation of difference-in-differences models with two-way fixed effects (Callaway & Sant’Anna, 2021; Goodman-Bacon, 2021; Sun & Abraham, 2021), we separately estimated treatment effects for each group of employers by the year that they began offering an HDHP to detect differences across treatment cohorts (Appendix E). Fifth, we examined changes in family size and enrollment associated with the HDHP offer in the treatment group to detect changes that would indicate that family members are switching to other plans in response to the HDHP offer (Appendix F).

Additionally, since families with multiple members with a SUD were not included in our primary analyses, we assessed the robustness of our findings to the inclusion of families with multiple members with a SUD (Appendix G). Finally, to assess the generalizability of our descriptive analysis of the proportion of family expenditures for the member with a SUD, we analyze a broader sample that includes employers that were excluded to establish treatment and comparison groups (Appendix H).

All analyses were conducted in Stata 16 MP. This study was approved by the IRB of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

3. Results

In Table 1, we compared unadjusted family characteristics between 175,069 family-years at treatment employers and 142,284 family-years at comparison employers. The modal and median family sizes in either group were two and three, respectively. We found that families at treatment and comparison employers had similar demographic and clinical characteristics. Using a standardized mean difference of 0.1, a commonly used threshold for assessing meaningful differences between groups (Austin, 2009), we found no substantial differences between the groups, except for the documented sex of the policyholder. A smaller percentage of policyholders were male in the treatment group compared to the comparison group (58.6% vs. 64.1%). However, the prevalence of chronic conditions between the groups was similar, with no standardized mean differences exceeding 0.1 (mean = 0.01, Appendix B). In both the treatment and comparison groups, the family member with SUD was most often the spouse, young adult dependent, or child dependent (68–70% of the time).

In Figure 1, we assessed the proportion of family health care spending that was spent on the individual with a SUD for families with the median family size of three members, stratified by the role of the family member who had SUD (N = 77,808 families). A disproportionate share of family total and out-of-pocket spending was accrued by the member with a SUD (i.e., more than 33% for a family of three). Specifically, on average, 56.9% and 56.7% of family total and out-of-pocket spending, respectively, were on services utilized by the member with a SUD. The proportions varied slightly depending on the role of the family member with a SUD, from 46.8% of total health care spending in families in which the member with a SUD was a young adult child to 65.5% in families in which that member was the policyholder. We also assessed these trends within a larger sample of families that were selected from a broader set of employers that were not required to meet our criteria for treatment and comparison employers (Appendix H), finding that these trends were very similar to those found in primary study sample. Further, we assessed trends in out-of-pocket health care spending and across all family sizes (Appendix I–K).

In Table 2, we investigated the association between the HDHP offer and the probability of any family health care spending (Panel A) and the level of spending, conditional on any spending (Panel B). We found that the HDHP offer was not significantly associated with the probability of having any health care spending for the whole family, the individual with SUD, or the other members of the family, but did result in significant reductions in the probability of the member with SUD having any SUD-related spending. We found that the HDHP offer was associated with a 2.4 percentage-point reduction (95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.038 to −0.010) in the probability of having any SUD-related spending, which equates to a 6.1% reduction given a pre-period probability of 0.392. Given that 45.7% of families in the treatment group in the post-period enrolled in HDHPs, the implied association for the treated families would correspond to a 13.3% reduction in having any SUD-related expenditures.

Additionally, we found that the HDHP offer was associated with $1,546 and $1,185 reductions in family expenditures for the whole family and on the individual with SUD (95% CI: −2,272 to −821 and −1,845 to −525, respectively) and with a $359 reduction in expenditures for other members of the family (95% CI: −602 to −116) but was not associated with any changes in SUD-related expenditures, conditional on any spending. The $1,185 reduction in total expenditures for the individual with SUD represent an approximate 8.6% reduction over the pre-period mean of $13,826 in average annual expenditures, compared to an approximate 4.7% decrease in expenditures for other members of the family given the $359 reduction from a $7,655 pre-period average. We find the estimated relationships to be directionally consistent across treatment cohorts by year of the employer’s first HDHP offer (Appendix E), though these regressions are estimated with reduced treatment sample sizes resulting in fewer statistically significant estimates. We also find the estimated relationships to be of similar direction and magnitude in families with multiple members with SUD (Appendix G).

In Table 3, we evaluated whether the association between the HDHP offer and health care spending differed depending on which family member had a SUD (policyholder compared to spouse, young adult dependent, or child dependent). We found no consistent evidence that the association between the HDHP offer and health care spending differed depending on which member of the family had a SUD. The HDHP offer was associated with a slightly smaller increase (0.5 percentage point increase, 95% CI: 0.001 to 0.009) in the probability of having any total family expenditures when the member with a SUD was the spouse compared to the policyholder. We also found that the HDHP offer had a stronger association with SUD-related spending, conditional on having any SUD-related spending, in families where the member with SUD was a young adult dependent ($668 increase, 95% CI: 211 to 1,125).

4. Discussion

This study examined the distribution of family health care spending and the association between HDHPs and health care spending among families that had a member with a SUD. We found that among enrolled families, enrollees with a SUD were most often family members of the employee, as opposed to the employee themselves and that the member with a SUD, on average, contributed an outsized proportion of total family health care expenditures.

When an employer offered a family a HDHP, this was associated with a reduction in the probability of having any SUD-related expenditures and in total family expenditures. We did not find any evidence that the reductions in SUD-related expenditures were larger in families in which the member who had a SUD is a parent, as we hypothesized. Jointly, these results suggest that family HDHPs may reduce the use of any SUD-related services, with no distinction for which member it is that has a SUD (e.g., a parent making the decision or a child with less agency in the decision). These findings are consistent with the emerging literature that finds that employer HDHP offers may lead to reductions in the utilization of SUD-related services among individuals with single coverage (Eisenberg, M. D. et al., 2022; Schilling, C. et al., 2020). However, we find no evidence that spending on SUD-related services, conditional on use, was affected by the HDHP offer. It is possible that HDHPs discourage the use of SUD services for those who might initiate treatment but is less discouraging for those with more intensive use of SUD services, whose spending may exceed their deductible. Future work should seek to understand why HDHPs reduced the probability of having any SUD-related services but had no effect on SUD services conditional on having any use.

Employers continue to offer HDHPs for family coverage in an effort to reduce their health care costs. When insurers and employers contemplate switching enrollees to HDHPs, they should consider the potential impact that offering a HDHP may have on enrollees and their family members who have a SUD. This is especially important for SUDs, as opposed to other chronic conditions, because fewer than 10% of individuals with a substance use disorder reported receiving treatment in the past year (SAMHSA, 2021). Our results suggest that HDHP offers may exacerbate the undertreatment of SUDs. Insurers, employers, and policymakers could also choose to require zero cost-sharing for SUD treatment, even for HDHPs (e.g., New Mexico Senate Bill 317, “No Behavioral Health Cost Sharing”) (Hickey & Steinborn, 2021).

Our study had the following limitations. The identifying assumption of our primary regression analyses was that if families at treatment employers were never offered an HDHP, then their health care spending would have followed similar trends to families at comparison employers. Relatedly, while our study design mitigates the influence of selection bias at the family level into HDHPs, there is still the possibility of selection bias at the employer level. Though these assumptions cannot formally be tested, we conducted a series of analyses to assess their validity, including tests for balance in baseline demographics, differences in pre-treatment trends, and changes in enrollment and family size. Collectively, these tests found no major differences between families enrolled at treatment employers relative to families enrolled at comparison employers.

Second, the dataset, while largely representative of commercially insured enrollees in the US, did not necessarily include enrollees of all health plans offered by an employer. We did not observe enrollees that switched to health plans not captured in these data but remained at the same employer. To address this concern, we limited our sample to employers without major changes year-to-year in total enrollees, which mitigates against the influence of large changes in enrollment that could occur concurrently with the HDHP offer.

Third, while this study focused on HDHPs, there may be other benefit design characteristics that vary between plans in addition to deductibles, such as provider networks. Our results characterize the association between health care expenditures and the total HDHP offer.

Finally, we characterize overall spending on SUD-related services in this study, which includes spending on hospitalizations and emergency department visits, in addition to spending in ambulatory settings. Future work should seek to understand how the effects HDHPs are distributed across different SUD services in the context of families where a member has a SUD.

5. Conclusions

Family members with a SUD contributed an outsized proportion of total family health care expenditures. Offering a family HDHP was associated with a 6.1% reduction in the probability of family members with a SUD having any SUD-related expenditures and large reductions in family health care spending conditional on having any. The increased prevalence of family enrollment in HDHPs may further the existing issue of undertreatment of SUDs.

Supplementary Material

References

- Agarwal R, Mazurenko O, & Menachemi N (2017). High-deductible health plans reduce health care cost and utilization, including use of needed preventive services. Health Affairs (Millwood), 36(10), 1762–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ. (2021). Medical expenditure panel survey insurance/employer component overview. Retrieved from https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/survey_comp/Insurance.jsp

- Arnold D, & Whaley C (2020). Who pays for health care costs? the effects of health care prices on wages. (). Rochester, NY: doi:10.2139/ssrn.3657598 Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3657598 [Google Scholar]

- Austin PC (2009). Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Statistics in Medicine, 28(25), 3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Epstein AJ, Fiellin DA, Fraenkel L, & Busch SH (2016). Estimating demand for primary care-based treatment for substance and alcohol use disorders. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 111(8), 1376–1384. doi: 10.1111/add.13364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Stuart EA, Donohue JM, Greenfield SF, Kouri E, Duckworth K, . . . Huskamp HA. (2015). The early impact of the ‘alternative quality contract’ on mental health service use and spending in massachusetts. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 34(12), 2077–2085. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buntin MB, Haviland AM, McDevitt R, & Sood N (2011). Healthcare spending and preventive care in high-deductible and consumer-directed health plans. The American Journal of Managed Care, 17(3), 222–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch AB, Frank RG, Lehman AF, & Greenfield SF (2006). Schizophrenia, co-occurring substance use disorders and quality of care: The differential effect of a managed behavioral health care carve-out. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 33(3), 388–397. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0045-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway B, & Sant’Anna PHC (2021). Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 200–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CBHSQ. (2017). The CBHSQ report. (). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2790/ShortReport-2790.html

- CDC. (2021). Products - vital statistics rapid release - provisional drug overdose data. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- Condition categories. Retrieved from https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories

- Eisenberg MD, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Schilling C, Busch A, Huskamp H, Stuart E, . . . Barry CL. (2022). The impact of high-deductible health plans on service use and spending for substance use disorders. American Journal of Managed Care, Retrieved from https://www.ajmc.com/view/the-impact-of-hdhps-on-service-use-and-spending-for-substance-use-disorders

- Eisenberg MD, Du S, Sen AP, Kennedy-Hendricks A, & Barry CL (2020). Health care spending by enrollees with substance use and mental health disorders in high-deductible health plans vs traditional plans. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(8), 872–875. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg MD, Haviland AM, Mehrotra A, Huckfeldt PJ, & Sood N (2017). The long term effects of “consumer-directed” health plans on preventive care use. Journal of Health Economics, 55, 61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith AA, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Rosenthal MB, Gay C, & Lieu TA (2012). Delayed and forgone care for families with chronic conditions in high-deductible health plans. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(9), 1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1970-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman-Bacon A (2021). Difference-in-differences with variation in treatment timing. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 254–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2021.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gryczynski J, Schwartz RP, O’Grady KE, Restivo L, Mitchell SG, & Jaffe JH (2016). Understanding patterns of high-cost health care use across different substance user groups. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 35(1), 12–19. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haviland AM, Eisenberg MD, Mehrotra A, Huckfeldt PJ, & Sood N (2016). Do “consumer-directed” health plans bend the cost curve over time? Journal of Health Economics, 46, 33–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SB 317: No behavioral health cost sharing, (2021). Retrieved from https://www.nmlegis.gov/Sessions/21%20Regular/bills/senate/SB0317.pdf

- IRS. (2018). Health savings accounts and other tax-favored health plans. (). Retrieved from https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-prior/p969-2017.pdf

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (2021). 2021 employer health benefits survey. (). Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2021-employer-health-benefits-survey/

- Kennedy-Hendricks A, Schilling CJ, Busch AB, Stuart EA, Huskamp HA, Meiselbach MK, . . . Eisenberg MD. (2021). Impact of high deductible health plans on continuous buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder. Journal of General Internal Medicine, doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07094-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander L, Howsare J, & Byrne M (2013). The impact of substance use disorders on families and children: From theory to practice. Social Work in Public Health, 28(0), 194–205. doi: 10.1080/19371918.2013.759005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurenko O, Buntin MJB, & Menachemi N (2019). High-deductible health plans and prevention. Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 411–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt RD, Haviland AM, Lore R, Laudenberger L, Eisenberg M, & Sood N (2014). Risk selection into consumer-directed health plans: An analysis of family choices within large employers. Health Services Research, 49(2), 609–627. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, & Kleber HD (2000). Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. Jama, 284(13), 1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OptumLabs. (2021). OptumLabs health care collaboration & innovation. Retrieved from https://www.optumlabs.com/

- Rabideau B, Eisenberg MD, Reid R, & Sood N (2021). Effects of employer-offered high-deductible plans on low-value spending in the privately insured population. Journal of Health Economics, 76, 102424. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2021.102424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2018). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the united states: Results from the 2018 national survey on drug use and health. (). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the united states: Results from the 2020 national survey on drug use and health. (). Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf

- Schilling C, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Eisenberg MD, Busch A, Stuart E, Huskamp H, . . . Barry CL. (2020). The effects of high deductible health plans on enrollees with mental health conditions with and without co-occurring substance use disorder. Manuscript Submitted for Publication, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling CJ, Eisenberg MD, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Stuart EA, . . . Barry CL. (2021). Effects of high-deductible health plans on enrollees with mental health conditions with and without substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), , appips202000914. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA (2016). Treatment of opioid-use disorders. The New England Journal of Medicine, 375(4), 357–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1604339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, & Abraham S (2021). Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 175–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jeconom.2020.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe K, Jain S, & Joski P (2017). Prevalence and spending associated with patients who have A behavioral health disorder and other conditions. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 36(1), 124–132. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westrich K, & Huff LR (2022). Adopting good practices for high-deductible health plans can help employers build better health benefits. The American Journal of Accountable Care, 10(1) Retrieved from https://www.ajmc.com/view/adopting-good-practices-for-high-deductible-health-plans-can-help-employers-build-better-health-benefits [Google Scholar]

- Wharam JF, Landon BE, Galbraith AA, Kleinman KP, Soumerai SB, & Ross-Degnan D (2007). Emergency department use and subsequent hospitalizations among members of a high-deductible health plan. Jama, 297(10), 1093–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.10.1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley EL, & Stover AN (2019). The impact of the opioid epidemic on children and adolescents. Clinical Therapeutics, 41(9), 1655–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge JM (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Young JQ, Kline-Simon AH, Mordecai DJ, & Weisner C (2015). Prevalence of behavioral health disorders and associated chronic disease burden in a commercially insured health system: Findings of a case-control study. General Hospital Psychiatry, 37(2), 101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.