ABSTRACT

Background

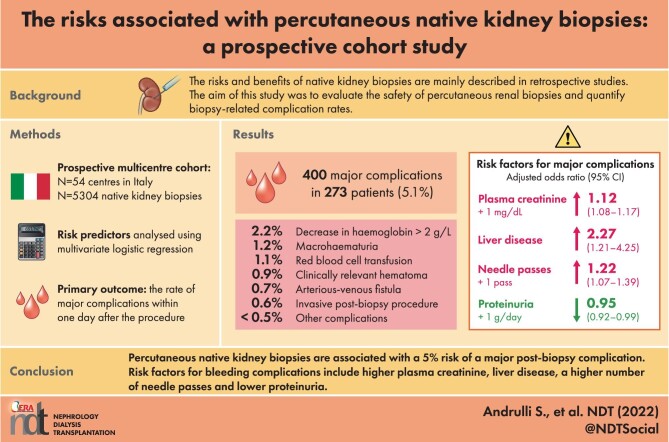

The known risks and benefits of native kidney biopsies are mainly based on the findings of retrospective studies. The aim of this multicentre prospective study was to evaluate the safety of percutaneous renal biopsies and quantify biopsy-related complication rates in Italy.

Methods

The study examined the results of native kidney biopsies performed in 54 Italian nephrology centres between 2012 and 2020. The primary outcome was the rate of major complications 1 day after the procedure, or for longer if it was necessary to evaluate the evolution of a complication. Centre and patient risk predictors were analysed using multivariate logistic regression.

Results

Analysis of 5304 biopsies of patients with a median age of 53.2 years revealed 400 major complication events in 273 patients (5.1%): the most frequent was a ≥2 g/dL decrease in haemoglobin levels (2.2%), followed by macrohaematuria (1.2%), blood transfusion (1.1%), gross haematoma (0.9%), artero-venous fistula (0.7%), invasive intervention (0.5%), pain (0.5%), symptomatic hypotension (0.3%), a rapid increase in serum creatinine levels (0.1%) and death (0.02%). The risk factors for major complications were higher plasma creatinine levels [odds ratio (OR) 1.12 for each mg/dL increase, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.08–1.17], liver disease (OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.21–4.25) and a higher number of needle passes (OR for each pass 1.22, 95% CI 1.07–1.39), whereas higher proteinuria levels (OR for each g/day increase 0.95, 95% CI 0.92–0.99) were protective.

Conclusions

This is the first multicentre prospective study showing that percutaneous native kidney biopsies are associated with a 5% risk of a major post-biopsy complication. Predictors of increased risk include higher plasma creatinine levels, liver disease and a higher number of needle passes.

Keywords: kidney biopsy, logistic regression, major complications, prospective cohort study, risk

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

KEY LEARNING POINTS.

What is already known about this subject?

Until now, the known risks and benefits of native kidney biopsies were mainly based on the findings of retrospective studies.

What this study adds?

This is the first multicentre prospective study showing that percutaneous native kidney biopsies in Italy are associated with a consistent and quantifiable 5% risk of a major post-biopsy complication. Predictors of increased risk include higher plasma creatinine levels, liver disease, low proteinuria and a higher number of needle passes.

What impact this may have on practice or policy?

The prospective estimated risk of a major post-biopsy complication may be used to improve informed consent procedures. Our findings will be of interest as they could have a very positive clinical impact on the diagnostic work-up and management of patients with a still undefined nephropathy.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 40 years, the approach to renal biopsies has evolved as a result of the use of ultrasound to examine the kidney [1] before and during the procedure (ultrasound-assisted biopsy) or to guide the biopsy needle (ultrasound-guided biopsy) and automatic core biopsies [2]. However, despite these advances, native kidney biopsies are not devoid of risks [3–6], and no large-scale multicentre study has provided prospective quantitative data concerning the risk of major complications that would allow nephrologists to give patients more precise information during informed consent procedures.

The aim of this Italian national multicentre study was to collect data concerning the results of native kidney biopsies in Italy that would allow a more accurate evaluation of the risk of major procedure-related complications. The main aim of this study was not the exact timing of major complications, but rather their occurrence in an adequate period of time, focusing on the first 24 h after renal biopsy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The invited study centres were not selected a priori or restricted to tertiary reference centres in order to ensure the collected data more closely reflected real-world clinical practice. Patient enrolment was competitive until it reached the quorum of 5000 patients required to make an accurate estimate of the risk of major complications. Data in the Italian Registry of Renal Biopsy (IRRB) [7, 8] suggested that reaching this sample size would take 5 years of active recruitment depending on the commitment of the centres.

As this was an observational study, although the reason for performing the procedure was checked, the enrolment criteria were not questioned. Consequently, all of the consecutive adult and paediatric patients undergoing a native kidney biopsy during the active recruitment period were considered eligible, and there were no a priori exclusion criteria.

All of the patients gave their written informed consent; the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bari University and implemented in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (No. NCT04948593).

Data collection

Data collection was centralized and made use of an ad hoc web-based database linked to the Italian Renal Biopsy Registry (http://www.irrb.net/). The participating centres were required to register and provide all of the data necessary to allow their correct identification, and, as this was an observational study, we collected information that was already available and typical of everyday clinical practice. No particular examinations were required. The particular nature of the study was that it allowed the prospective collection of ad hoc data with the greatest possible accuracy and standardization.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was any major post-native kidney biopsy complication 1 day after the procedure, or for longer if it was necessary to evaluate the evolution of a complication. All such complications were carefully and prospectively checked, and included clinically relevant cases of haematoma and macrohaematuria, a ≥2 g/dL decrease in haemoglobin levels after 24 h, the need for blood transfusion, the presence of a large and persistent artero-venous fistula, post-biopsy anuria, a >50% increase in serum creatinine levels in the week following the biopsy, the need for an invasive post-biopsy procedure including nephrectomy and death. A haematoma was considered clinically relevant during the data cleaning phase if its greater diameter was >5 cm, if it required longer hospitalization or a blood transfusion, or if the presence of pain indicated a need for an invasive intervention. Any haematoma with greater diameter ≤5 cm or transient gross haematuria was considered a clinically irrelevant minor complication, and so not included in the analysis. During the data collection phase, the attending physician had to fill a form, including the Boolean checks about every major complication and the open-ended text description to better define the clinical outcome. In this way, no subjective judgement could have influenced the accuracy of the main outcome since redundant information was used for data validation.

Predictive variables

Relevant covariates and factors related to the participating centres or individual patients were prospectively recorded. The information concerning each centre included the number of biopsies performed per year, whether it was a hospital for children or adults, the department in which the biopsy was performed, the place in which the core biopsied tissue was processed, the size of the needle cutting section, whether bleeding time was routinely recorded, whether renal biopsy patients were routinely hospitalized, the number of physicians in the hospital's renal biopsy team, whether there was a specific protocol for overweight patients, the prophylactic use of antibiotics and the results of routine ultrasound examinations the day after the biopsy.

The information concerning individual patients included their age and gender, comorbidities, the clinical presentation of their renal disease, the presence of renal failure, pre-biopsy haemoglobin level, platelet count, renal function, dialysis status, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), position during the biopsy, biopsied side, whether computed tomography (CT) was used to perform the biopsy, the size of the biopsied kidney, the use of anti-platelet agents, the number of needle passes, needle size, pre- and post-biopsy medical treatments, the duration of bed rest and the use of post-biopsy local ice compression.

Data were collected up to the first day after the biopsy in order to evaluate the possible occurrence of a haematoma 24 h after the procedure, or for longer if it was necessary to evaluate the evolution of a complication.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed quantitative variables were analysed using their mean values and standard deviations, and skewed quantitative variables such as the indices of central tendency and variability were analysed using their median values and the 10th and 90th percentiles. Categorical variables were analysed as absolute numbers and percentages.

Multivariate odds ratios (ORs) and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the estimated risk of any major complication associated with the prognostic factors and covariates were calculated using multivariate binary logistic regression. The backward approach was used to simplify the saturated model until finding the best compromise between simplicity (as few factors and covariates as possible) and goodness of fit (the amount of explained variance). The Pin and Pout values were respectively set at 0.1 and 0.05. Given their epidemiological or expected clinical relevance, predictors such as gender, age and the annual number of native kidney biopsies carried out at each centre were retested in the final model.

All of the analyses were made using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 23.0.

RESULTS

This study involved 160 nephrologists at 54 centres located in 17 of Italy's 20 regions (see Appendix). Enrolment lasted from 3 January 2012 to 4 August 2020, and was most active in three centres (Bari, Eboli and Bologna). Tables 1 and 2 show the main characteristics of the centres. The centres performed a median of 73 native kidney biopsies (10th and 90th percentiles 10 and 197) over a median of 3.1 years (10th and 90th percentiles 0.5 and 4.6 years); the median number of biopsies per year (25.5) was in line with the expected number. The median length of the needle cutting section was 20 mm. Anti-platelet drugs were discontinued a median of 7 days before the procedure (Table 2). The biopsies were most frequently performed in nephrology departments (74%), and the core tissue was most frequently processed by the hospitals’ pathology service (65%). Immunofluorescence tests were assured by 96% of the centres, but electronic microscopy was available in only 67%. Bleeding time was routinely recorded by 57% of the centres, and antibiotic prophylaxis was administered by 20%. One-third of the centres had a specific protocol for overweight patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 54 participating centres (categorical variables)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Department in which biopsies were carried out (Nephrology/Radiology/Other) | 74/19/7 |

| Place of core processing (Local/Pathology Service/Other) | 9/65/26 |

| Immunofluorescence | 96 |

| Electron microscopy | 67 |

| Diagnostic report (Nephrologist/Nephrologist and Pathologist/Pathologist) | 9/39/50 |

| Scheduled meetings | 67 |

| Bleeding time measured/recorded | 57 |

| Dedicated procedure for obese subjects | 32 |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis before biopsy | 20 |

| Post-biopsy ultrasound check | 91 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of participating centres (quantitative variables)

| No. | Percentiles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centres | Missing | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | |

| Number of biopsies per centre | 54 | 0 | 10.0 | 33.3 | 73.0 | 125.8 | 196.5 |

| Number of event-free biopsies per centre | 54 | 0 | 9.0 | 32.0 | 69.5 | 116.8 | 189.5 |

| Number of biopsies per centre followed by a major event | 54 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 | 13.5 |

| Event frequency per centre (%) | 54 | 0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 5.2 | 8.8 | 13.9 |

| Recruitment duration per centre (years) | 54 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 4.6 |

| Expected number of biopsies per year | 51 | 3 | 9.2 | 13.0 | 25.0 | 40.0 | 86.2 |

| Actual number of biopsies per year | 54 | 0 | 12.4 | 18.9 | 25.5 | 40.1 | 68.4 |

| Needle cutting section (mm) | 49 | 5 | 15 | 16 | 20 | 22 | 23 |

| Pre-biopsy anti-platelet drug discontinuation (days) | 53 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 10 |

| Number of physicians in renal biopsy team | 53 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

Tables 3–5 show the clinical characteristics of the 5304 enrolled patients: 332 aged <18 years and 4972 aged ≥18 years. The median age of the patients was 53.2 years (10th and 90th percentiles 22.2 and 74.2 years). Most of the patients were male (61%), and the biopsies were most frequently carried out because of urine abnormalities (43%) or nephrotic syndrome (39%). Renal failure was present in 57% of cases (chronic renal failure in 30%, isolated acute renal failure in 16% and acute renal failure in the context of chronic renal failure in 11%). Serum creatinine values ranged from normal to those typical of severe renal insufficiency (median 1.4 mg/dL; 10th and 90th percentiles 0.7 and 5.2 mg/dL); 5% of the patients were dialysed. Proteinuria levels varied from low pathological values to values compatible with nephrotic syndrome in 38.5% of cases (median 2.4 g/day; 10th and 90th percentiles 0.4 and 9.3 g/day). The median blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg; 10% of the patients had values of >150/90 mmHg and BMI values of >32.2 kg/m2. Pre-biopsy haemoglobin levels were <9.4 g/dL in 10% of the patients, thus suggesting the presence of pre-biopsy anaemia.

Table 3.

Patient and biopsy related characteristics (quantitative variables)

| No. | Percentiles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Missing | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | |

| Age (years) | 5296 | 8 | 22.2 | 38.0 | 53.2 | 66.2 | 74.2 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 5304 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 5.2 |

| Proteinuria (g/day) | 5304 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 9.3 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 5286 | 18 | 110 | 120 | 130 | 140 | 150 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 5286 | 18 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 80 | 90 |

| Body weight (kg) | 4765 | 539 | 53.4 | 62.4 | 72.0 | 83.0 | 95.0 |

| BMI | 3999 | 1305 | 20.2 | 22.6 | 25.3 | 28.4 | 32.2 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 5299 | 5 | 9.4 | 10.7 | 12.2 | 13.8 | 15.0 |

| Platelet count (× 1000) | 2705 | 2599 | 156 | 190 | 236 | 290 | 350 |

| INR | 2705 | 2599 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 1.14 |

| Bipolar kidney diameter (cm) | 4167 | 1137 | 9.7 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 11.6 | 12.1 |

| Parenchymal thickness (cm) | 3881 | 1423 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Needle gauge | 5255 | 49 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 18 |

| Biopsy passes (n) | 4929 | 375 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Biopsy cores (n) | 5116 | 188 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Glomeruli (n) | 5136 | 168 | 6 | 10 | 14 | 20 | 28 |

| Bed rest (h) | 5103 | 201 | 12 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Haematoma (greater diameter, cm) | 831 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 7.0 | |

| Haematoma (smaller diameter, cm) | 765 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.5 | |

Table 5.

Comorbidities

| % | |

|---|---|

| Arterial hypertension | 52.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14.0 |

| Rheumatic/immunological disease | 13.6 |

| Infectious disease | 3.8 |

| Lymphoproliferative disease | 6.3 |

| Liver disease | 2.3 |

| Others | 30.4 |

Table 4.

Patient and biopsy related characteristics (categorical variables)

| % | |

|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 61/39 |

| Frequency of biopsied patients on dialysis | 5 |

| Biopsy side (left/right) | 95/5 |

| Ultrasound approach (guided/assisted) | 82/16 |

| Needle gauge (14/16/18) | 16/70/14 |

| Biopsy passes (1/2/3/4+) | 17/60/18/5 |

| Type of imaging used in biopsy procedure (CT/ultrasound) | 1/99 |

The biopsy samples were almost always taken from the left side (95%). The bipolar diameter of the kidney was frequently normal (median 11 cm, 10th and 90th percentiles 9.7 and 12.1 cm), and the median parenchymal thickness was 1.6 cm (10th and 90th percentiles 1.0 and 2.0 cm). The median needle gauge was 16 G (10th and 90th percentiles 14 and 18 G). The needles were used for a median of two passes (10th and 90th percentiles 1 and 3), most frequently with the guide anchored to the probe (82%), and collected a median of 14 glomeruli for optical microscopy (10th and 90th percentiles 6 and 28). The haematomas arising after 831 biopsies (15.7%) had median greater and smaller diameters of 2.7 cm (10th and 90th percentiles 0.6 and 7.0 cm) and 1.0 cm (10th and 90th percentiles 0.3 and 3.5 cm), respectively.

As expected, the most frequent comorbidity was arterial hypertension (52.3%), followed by diabetes mellitus (14.0%), rheumatic/immunological disease (13.6%), lymphoproliferative disease (6.3%), infectious disease (3.8%) and liver disease (2.3%).

Table 6 shows the histopathological diagnoses: the most frequent was immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy (15.6%), followed by idiopathic membranous nephropathy (13%), undefined nephropathy (9.6%), focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (8.7%), minimal change disease (6.9%) and diabetic nephropathy (6.7%). A normal kidney was diagnosed in 1.8% of cases (3.3% in paediatric cases). No rebiopsies of the same patient were included in the study.

Table 6.

Histopathological diagnoses of 5304 native kidney biopsies.

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| IgA nephropathy | 826 | 15.6 |

| Membranous nephropathy | 690 | 13.0 |

| Undefined nephropathy | 507 | 9.6 |

| Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis | 460 | 8.7 |

| Minimal change disease | 367 | 6.9 |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 353 | 6.7 |

| Lupus nephritis | 333 | 6.3 |

| Hypertension and ischemic renal injury | 328 | 6.2 |

| ANCA-associated vasculitis | 305 | 5.8 |

| Tubulo-interstitial disease | 283 | 5.3 |

| Amyloidosis | 184 | 3.5 |

| Normal kidney | 93 | 1.8 |

| Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis | 83 | 1.6 |

| Myeloma cast nephropathy | 82 | 1.5 |

| Light chain deposition disease | 63 | 1.2 |

| C3 nephropathy | 63 | 1.2 |

| Henoch Schoenlein purpura | 62 | 1.2 |

| Hereditary glomerulopathies | 55 | 1.0 |

| Acute post-infection glomerulonephritis | 42 | 0.8 |

| Thrombotic micro-angiopathy | 37 | 0.7 |

| AntiGBM disease | 30 | 0.6 |

| Cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis | 20 | 0.4 |

| Immunotactoid/fibrillary nephropathy | 17 | 0.3 |

| Storage disease | 9 | 0.2 |

| Other | 7 | 0.1 |

| Inadequate material | 5 | 0.1 |

Table 7 shows biopsy-related complications. One or more major complications occurred in 273 patients (5.1%, 95% CI 4.5%–5.7%), who experienced a total of 400 major events. The most frequent was a ≥2 g/dL decrease in haemoglobin levels (2.2%), followed by macrohaematuria (1.2%), blood transfusion (1.1%), gross haematoma (0.9%), artero-venous fistula (0.7%), invasive intervention (0.5%), pain (0.5%), symptomatic hypotension (0.3%) and a rapid increase in serum creatinine levels (0.1%). The one procedure-related death (0.02%) was due to massive bleeding in the paravertebral and gluteal muscles after the post-biopsy occurrence of a large peri-renal haematoma measuring 12 × 5 cm in a male aged 67 years. He had a histopathological diagnosis of myeloma cast nephropathy, a pre-biopsy serum creatinine level of 2.5 mg/dL, and was undergoing dialysis to remove light-chain immunoglobulins. No post-biopsy nephrectomies were required.

Table 7.

Major post-biopsy events

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Decrease in haemoglobin level of ≥2 g/dL | 115 | 2.2 |

| Clinically relevant macrohaematuria | 65 | 1.2 |

| Red blood cell transfusion | 60 | 1.1 |

| Clinically relevant haematoma | 50 | 0.9 |

| Arterious-venous fistula | 37 | 0.7 |

| Invasive post-biopsy procedure | 29 | 0.5 |

| Clinically relevant colic pain | 26 | 0.5 |

| Symptomatic hypotension | 14 | 0.3 |

| Rapid, >50% increase in creatinine level in post-biopsy week | 3 | 0.1 |

| Death | 1 | 0.02 |

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 8) showed that the risk factors for at least one major complication were a high plasma creatinine level (OR 1.12 for each increase of 1 mg/dL, 95% CI 1.08–1.17; P < .001), concomitant liver disease (OR 2.27, 95% CI 1.21–4.25; P = .010) and a high number of needle passes (OR 1.22 for each additional pass, 95% CI 1.07–1.39; P = .003). High proteinuria levels (OR 0.95 for each additional 1 g/day, 95% CI 0.92–0.99; P = .009) and ultrasound-guided versus ultrasound-assisted biopsy (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.49–0.95; P = .022) were protective factors. Dialysed patients were also associated with an increased risk of major post-biopsy complications (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.42–3.36; P < .001), but this association lost its significance (OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.80–2.19; P = .268) when plasma creatinine level was included in the model. No differences were found in the rate of major complications according to the department in which biopsies were carried out (P = .253), to the pre-biopsy systolic and diastolic blood pressure values (P = .694 and 0.699, respectively) and to the haemoglobin values (OR 0.97 for each increase of 1 g/dL, 95% CI 0.91–1.05; P = .466).

Table 8.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of the predictors of the risk of experiencing at least one major post-biopsy complication

| B | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male versus female) | −0.246 | 0.134 | 3.380 | .066 | 0.782 | 0.602–1.016 |

| Age (years) | 0.004 | 0.004 | 1.391 | .238 | 1.004 | 0.997–1.012 |

| Creatinine (for each increase of 1 mg/dL) | 0.117 | 0.021 | 30.951 | <.001 | 1.124 | 1.079–1.171 |

| Proteinuria (for each increase of 1 g/day) | −0.049 | 0.019 | 6.771 | .009 | 0.952 | 0.918–0.988 |

| Biopsy passes (for each additional pass) | 0.198 | 0.067 | 8.721 | .003 | 1.219 | 1.069–1.391 |

| Ultrasound-guided versus ultrasound-assisted biopsy | −0.383 | 0.167 | 5.281 | .022 | 0.682 | 0.492–0.945 |

| Liver disease (yes versus no) | 0.821 | 0.320 | 6.594 | .010 | 2.272 | 1.214–4.252 |

| Year of biopsy (for each year after 2012) | −0.068 | 0.035 | 3.826 | .050 | 0.935 | 0.873–1.000 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | −0.002 | 0.005 | 0.155 | .694 | 0.998 | 0.988–1.008 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.149 | .699 | 1.003 | 0.987–1.019 |

Patient age at the time of biopsy was not associated with the risk of a major complication either as a continuous variable per year (OR 1.004, 95% CI 0.997–1.012; P = .238) or as a categorical variable considering the three age groups of <18 years, ≥18 but <65 years or ≥65 years (P = .828).

Males seemed to be at a slightly lower risk of post-biopsy complications than females, but the difference was not statistically significant (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.60–1.02; P = .066).

Other factors more unexpectedly not associated with the risk of biopsy complications included the annual number of biopsies performed at a centre (OR 0.999 for each additional biopsy/year, 95% CI 0.995–1.003; P = .59), bipolar kidney diameter (OR 0.91 for each additional cm, 95% CI 0.80–1.04; P = .159) and needle gauge (OR 0.958 for each additional gauge, 95% CI 0.852–1.077; P = .473), although only 30% of centres used differently sized needles depending on the patients’ characteristics. Finally, unlike some specific diagnoses such as anti-glomerular basement membrane (GBM) disease (OR 6.13, 95% CI 1.75–21.45; P = .005) or ANCA-associated vasculitis (OR 4.20, 95% CI 1.53–11.56; P = .005), the post-biopsy histological diagnoses did not seem to be associated with an increased risk of complications (P = .222).

The final model correctly distinguished patients experiencing major complications with 49.2% sensitivity, 66.6% specificity, 65.7% overall accuracy, a 7.3% positive predictive value and a 96.1% negative predictive value.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this planned, prospective study involving many nephrology centres throughout Italy over the last decade is that a native kidney biopsy is associated with a 5.1% point-estimated risk of experiencing at least one major complication, a uniquely valuable finding obtained by checking all clinically relevant events using ultrasound and colour Doppler imaging 1 day after the procedure. The study also provides data about individual complications: for example, post-biopsy red blood cell transfusions and invasive interventions were required in 1.1% and 0.5% of cases, respectively, which is similar to the rates described in some other studies [5, 6, 9] but less than those in some population-based studies [3, 4] and more than those in some registry-based studies [10]. However, the findings of the large-scale, American retrospective population-based study of >118 000 hospital admissions for native kidney biopsies by Al Turk et al. [3] cannot be entirely attributed to kidney biopsy complications as the patients often had co-morbidities (49% anaemia, 14% heart failure, 15% chronic pulmonary disease and 11% coagulopathy), the mortality rate was high (1.8%) and there was a very high incidence of red blood transfusions (26%); furthermore, the French population-based study [4] over-estimated the risks of red blood cell transfusions and death as not all of the events were attributable to kidney biopsies. The results of the meta-analysis by Poggio et al. [6] are similar to our findings, probably because the point-estimates of the American study [3] were counter-balanced by the under-estimates of major post-biopsy events typical of many small retrospective studies. Similarly, the under-reported complication rates in the retrospective registry-based study of Tondel et al. [10] (0.9% of the patients required blood transfusions and 0.2% underwent surgery or catheterization) can be explained by its retrospective registry-based design.

The second major finding of our study concerns the predictors of major events. It was expected that the annual number of biopsies performed out at a centre would affect the occurrence of complications [10], but this finding was not confirmed in our study (OR 1.002, CI 0.997–1.007; P=0.548) suggesting that the risk of complications is not higher in less experienced centres. Furthermore, unlike Doyle et al. [11], we found that the risk of major complications was not related to the gauge of the needle (P = .473), which is probably more closely associated with centre practices than patient characteristics as 70% of the centres used the same type of needle for all of their patients.

On the other hand, unlike Tondel et al. [10], we found a direct association between the number of needle passes and the risk of major complications (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.07–1.39; P = .003), with a 22% increased risk for each additional pass. This suggests that obtaining an additional research biopsy core may have a negative impact, as has been found in the ongoing prospective TRIDENT observational study [12].

High proteinuria levels were associated with a lower risk of complications (OR 0.95 for each additional 1 g/day, 95% CI 0.92–0.99; P = .009), thus increasing the benefit/risk ratio in highly proteinuric adult patients who are more likely to undergo a renal biopsy. Furthermore, in line with the suggestion of Gigante et al. [13], we speculate that the thrombophilic status of patients with nephrotic syndrome can decrease the risk of post-biopsy bleeding.

Unlike other retrospective [14] and prospective studies [15] indicating that younger patients are at greater risk of post-biopsy complications, we found no significant association with age (OR 1.004, 95% CI 0.997–1.012; P = .238). This discrepancy may be because the retrospective study [14] involved outpatients and the prospective study [15] mainly analysed more frequent minor complications (34%) rather than rarer major complications (6/471 biopsies, 1.2%), thus underlining the difficulty of comparing studies with different endpoints.

Another finding relates to renal function. In line with other studies [5, 10, 16], we found that the independent effect of renal function was highly significant (OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.08–1.17; P < .001), with the risk of complications increasing by 12% with each mg/dL increase in pre-biopsy plasma creatinine levels. Dialysed patients were also associated with an increased risk of major post-biopsy complications (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.42–3.36; P < .001), but this association lost its significance (OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.80–2.19; P = .268) when plasma creatinine level was included in the model.

The information given to patients when obtaining their informed consent to a native kidney biopsy is often inadequate because it is based on the findings of retrospective studies [17] conducted by a single centre [18, 19] and characterized by a small sample size [18] or poorly standardized primary outcomes [3, 4, 9, 15], or comes from heterogeneous populations of locally specific elective patients [20], registry data [10] or national population databases [3, 4, 9]. Even meta-analyses may be affected by the same limitations as their sources, and as they are based on aggregate data [5, 6], cannot make individual-based multivariate analyses of the role of putative predictors. It is interesting to consider the two putative predictors of needle gauge and the number of biopsy passes: Corapi et al. [5] found that 14-gauge needles were associated with higher transfusion rates than smaller 16- and 18-gauge needles (2.1% versus 0.5%; P = .009) and, although they did not infer any associated risk, their patients underwent a mean number of two passes, whereas Poggio et al. [6] found that the risk of transfusion was much higher with an 18-gauge needle than with a 16-gaude needle (16.1% versus 5.7%; P = .06) and did not draw any descriptive or inferential conclusions concerning the number of passes. In contrast, our findings indicate that the number of passes on an individual basis can affect biopsy-related complication rates.

Our mean point estimate of a 5.1% risk of a major complication is valid for the analysed biopsies as a whole, but even a multivariate approach leads to uncertainty concerning individual risk. The a priori risk is ∼5.1%, but the contribution of a posteriori data increases the estimate's positive predictive value only to 7.3%, thus indicating greater individual variability.

Although the voluntary collaboration of the participating centres may have had a negative impact on the quality of the data, we believe that the strengths of this study counterbalance this drawback properly. Indeed, it focused on a largely under-investigated subject, it has a prospective design, an adequate sample size, a virtually national coverage and a systematic search for any major post-biopsy complication while performing an analysis of the data at an individual patient level.

This is the first multicentre prospective study showing that percutaneous native kidney biopsies in Italy have been associated with a consistent, prospectively recorded and quantifiable 5.1% risk of a major post-biopsy complication over the last 10 years, and that the predictors of this risk include the level of renal function, liver disease, the number of needle passes and a low proteinuria level.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Società Italiana di Nefrologia (SIN) and the Fondazione Italiana del Rene (FIR) for their financial support in developing the website database and the linguistic revision of the manuscript. This was an independent study without any direct sponsorship, and so there was no financial conditioning that may have affected the analyses.

APPENDIX

Cities (in alphabetical order), affiliations and names of collaborative authors of the ITA-KID-BIO-Group:

| ACIREALE, Ospedale Santa Marta e Santa Venera: | Maurizio Garozzo and Giovanni Giorgio Battaglia |

| AGRIGENTO, U.O.C Nefrologia e Dialisi San Giovanni di Dio: | Antonio Granata, Giulio Distefano, Monica Insalaco and Rosario Maccarrone |

| ALBANO LAZIALE, Ospedale Regina Apostolorum: | Marco Leoni, Angelo Emanuele Catucci and Emanuela Cavallaro |

| ANCONA, Umberto I: | Carolina Finale, Valentina Nastasi, Andrea Ranghino and Domenica Taruscia |

| AOSTA, Ospedale Regionale Umberto Parini: | Massimo Manes and Andrea Molino |

| ASCOLI PICENO, Ospedale ‘C. e G. Mazzoni’: | Giuseppe Fioravanti, Cinzia Fiori and Rosaria Polci |

| ASTI, S.C. Nefrologia e Dialisi Osp. Cardinal Massaia: | Olga Randone, Nicola Giotta and Stefano Maffei |

| BARI, Ospedale Paediatrico Giovanni XXIII: | Mario Giordano, Diletta Domenica Torres, Sebastiano Nestola and Vincenza Carbone |

| BARI, Policlinico—Ist. Nefrologia: | Loreto Gesualdo, Annamaria Di Palma, Michele Rossini, Paola Suavo-Bulzis, Cosma Cortese, Umberto Venere, Domenico Roselli and Carmen Sivo |

| BOLOGNA, Policlinico S. Orsola—Malpighi: | Gaetano La Manna, Olga Baraldi, Claudia Bini and Gisella Vischini |

| BORGOMANERO, Osp. SS. Trinità: | Luisa Benozzi and Stefano Cusinato |

| BRINDISI, Ospedale A. Perrino: | Luigi Vernaglione, Brigida Di Renzo, Cosima Balestra, Palmira Schiavone, Alessio Montanaro and Concetta Giovine |

| CASTELFRANCO VENETO, Osp. S. Giacomo: | Abaterusso Cataldo and Roberta Lazzarin |

| CATANIA, Nefrologia Cannizzaro: | Antonio Granata, Giuseppe Seminara and Daniela Puliatti |

| CHIETI, Policlinico ‘SS. Annunziata’: | Mario Bonomini, Roberto Di Vito, Teresa Lombardi and Luigia Larlori |

| CIRIÈ, Ospedale Civile: | Carolina Maria Licata and Vincenza Calitri |

| COMO, S. Anna: | Marco D'Amico and Beniamina Gallelli |

| CUNEO, Osp. S. Croce: | Elisabetta Moggia |

| EBOLI, Ospedale Maria Santissima Addolorata: | Giuseppe Gigliotti, Francesca Bruno, Pierluigi D'Angiò, Michele Nigro and Vincenzo Ragone |

| FERRARA, S. Anna: | Yuri Battaglia, Alda Storari, Sergio Sartori and Paola Tombesi |

| FOGGIA, Nefrologia Universitaria: | Barbara Infante, Giulia Godeas and Giovanni Stallone |

| FORLÌ, Morgani Pierantoni: | Marco De Fabritiis and Giovanni Mosconi |

| GENOVA, IRCCS Policlinico San Martino Genova: | Francesca Viazzi and Penna Davide |

| LECCO, Ospedale A. Manzoni: | Simeone Andrulli |

| LECCO, Associazione Italiana Ricercare per Curare (AIRpC): | Simeone Andrulli, Giovanni De Vito, Salvatore David and Giovanni Valsecchi |

| LA SPEZIA, Sant'Andrea: | Davide Rolla, Valentina Corbani, Francesca Lauria, Laura Panaro and Francesca Cappadona |

| MESSINA, Policlinico-Nefrologia: | Domenico Santoro, Guido Gembillo and Antonello Salvo |

| MILANO, ASST Fatebenefratelli-Sacco, Università di Milano: | Nicoletta Landriani, Maurizio Gallieni and Gianmarco Sabiu |

| MODENA, Policlinico: | Francesco Fontana, Riccardo Magistroni, Ronni Luca Spaggiari, Francesca Testa and Gianni Cappelli |

| NAPOLI, Università della Campania—Nefrologia: | Giovambattista Capasso, Pollastro Rosa Maria and Viggiano Davide |

| NOVARA, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Maggiore della Carità: | Doriana Chiarinotti and Maria Maddalena Conte |

| NOVARA, Nephrology and Transplant Unit, ‘Maggiore della Carità’ University Hospital, Università del Piemonte Orientale: | Marco Quaglia |

| ORISTANO, S.C. Nefrologia e Dialisi Ospedale San Martino: | Corrado Murtas and Antonio Maria Pinna |

| PALERMO, Ospedale Cervello: | Angelo Ferrantelli and Maria Giovanna Vario |

| PALERMO, UO di Nefrologia Dialisi e Trapianto ARNAS Civico: | Gioacchino Li Cavoli, Luisa Bono and Antonio Amato |

| PARMA, UOC Nefrologia, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria di Parma: | Lucio Manenti, Isabella Pisani and Monia Incerti |

| PAVIA, Clinica del Lavoro: | Ciro Esposito and Luca Semeraro |

| PERUGIA, Ospedale Santa Maria della Misericordia: | Rachele Brugnano, Raffaela Sciri and Ilaria Carriero |

| PESARO, Ospedali Riuniti Marche Nord: | Marina Di Luca, Flavia Manenti, Marco Palladino, Xhensila Gabrocka and Francesca Pizzolante |

| PISA, S. Chiara-Nefrologia: | Antonio Pasquariello, Giovanna Pasquariello, Maurizio Innocenti and Matilde Masini |

| PISA, U.O. Nefrologia Dialisi e Trapianti, Osp. CISANELLO: | Domenico Giannese |

| RAVENNA, S. Maria delle Croci: | Fulvia Zanchelli, Andrea Buscaroli and Mattia Monti |

| REGGIO EMILIA, S. Maria Nuova: | Enrica Gintoli, Elisa Gnappi and Mariacristina Gregorini |

| RIMINI, Osp. Degli Infermi: | Paola De Giovanni and Angelo Rigotti |

| ROMA, Policl. Umberto I: | Rosario Cianci and Antonietta Gigante |

| ROZZANO, Istituto Clinico Humanitas: | Leonardo Spatola, Salvatore Badalamenti, Calvetta Albania, Claudio Angelini, Francesco Reggiani, Gian Luca Dall'Olio, Sara Maria Italia Achenza and Silvia Santostasi |

| S. GIOVANNI ROTONDO, Fondazione Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza IRCCS: | Filippo Aucella, Matteo Piemontese, Michele Antonio Prencipe and Angela Maria Pellegrino |

| TARANTO, SS. Annunziata: | Luigi Morrone and Arcangelo Di Maggio |

| TORINO, Osp. Mauriziano: | Cristina Marcuccio |

| TORINO, Ospedale Martini: | Roberto Boero and Giulio Cesano |

| TORINO, Regina Margherita: | Bruno Gianoglio, Francesca Mattozzi and Vitor Hugo Martins |

| TRENTO, Presidio Ospedaliero Santa Chiara: | Laura Sottini and Giuliano Brunori |

| TRIESTE, IRCCS Burlo Garofolo: | Marco Pennesi, Silvia Nider and Cristina Tumminelli |

| VERBANIA, Osp. Castelli: | Maurizio Borzumati, Maria Carmela Vella and Stefania Gioira |

| VERCELLI, S. Andrea: | Giovanna Mele, Luigia Costantini and Patrizia Colombo |

| VITERBO, Belcolle: | Sandro Feriozzi, David Micarelli, Franca Luchetta, Franco Brescia and Rossella Iacono |

Contributor Information

Simeone Andrulli, N ephrology and Dialysis, Alessandro Manzoni Hospital, Lecco, Italy; Associazione Italiana Ricercare per Curare (AIRpC), Lecco, Italy.

Michele Rossini, Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation, University of Bari, Bari, Italy.

Giuseppe Gigliotti, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Maria Santissima Addolorata Hospital, Eboli, Italy.

Gaetano La Manna, Nephrology Dialysis and Renal Transplantation Unit, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

Sandro Feriozzi, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Belcolle Hospital, Viterbo, Italy.

Filippo Aucella, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, IRCCS Ospedale Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, San Giovanni Rotondo, Italy.

Antonio Granata, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, ‘San Giovanni di Dio’ Hospital, Agrigento, Italy; Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Cannizzaro Hospital, Catania, Italy.

Elisabetta Moggia, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Ospedale S. Croce, Cuneo, Italy.

Domenico Santoro, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Università degli Studi di Messina Facoltà di Medicina e Chirurgia, Messina, Italy.

Lucio Manenti, Dipartimento di Medicina e Chirurgia, UO di Nefrologia, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Parma, Parma, Italy.

Barbara Infante, Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation Unit, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Foggia, Foggia, Italy.

Angelo Ferrantelli, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Villa Sofia Cervello United Hospitals, Palermo, Italy.

Rosario Cianci, Nephrology Unit, Umberto I Policlinico di Roma, Roma, Italy.

Mario Giordano, Nephrology Division, Giovanni XXIII Children's Hospital, Bari, Italy.

Domenico Giannese, Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria Pisana, Pisa, Italy.

Giuseppe Seminara, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Cannizzaro Hospital, Catania, Italy.

Marina Di Luca, Unit of Nephrology and Dialysis, San Salvatore Hospital, Pesaro, Italy.

Mario Bonomini, Department of Medicine, G. d'Annunzio University of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy.

Leonardo Spatola, Renal and Hemodialysis Unit, Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Rozzano, Italy.

Francesca Bruno, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Maria Santissima Addolorata Hospital, Eboli, Italy.

Olga Baraldi, Nephrology Dialysis and Renal Transplantation Unit, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

David Micarelli, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Belcolle Hospital, Viterbo, Italy.

Matteo Piemontese, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, IRCCS Ospedale Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza, San Giovanni Rotondo, Italy.

Giulio Distefano, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, ‘San Giovanni di Dio’ Hospital, Agrigento, Italy.

Francesca Mattozzi, Paediatric Nephrology Unit, Regina Margherita Children's Hospital, Torino, Italy.

Paola De Giovanni, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Ospedale degli Infermi di Rimini, Rimini, Italy.

Davide Penna, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova, Italy.

Maurizio Garozzo, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Santa Marta and Santa Venera Hospital District, Acireale, Italy.

Luigi Vernaglione, Nephrology and Dialysis, ‘M. Giannuzzi’ Hospital of Manduria, Brindisi, Italy.

Cataldo Abaterusso, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Civil Hospital of Castelfranco Veneto, Castelfranco Veneto, Italy.

Fulvia Zanchelli, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Ospedale Santa Maria delle Croci, Ravenna, Italy.

Rachele Brugnano, Renal Unit, Ospedale R. Silvestrini, Perugia, Italy.

Enrica Gintoli, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy.

Laura Sottini, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Presidio Ospedaliero Santa Chiara, Trento, Italy.

Marco Quaglia, AOU Maggiore Della Carità, Università del Piemonte Orientale Amedeo Avogadro, Novara, Italy.

Gioacchino Li Cavoli, Nephrology and Dialysis, A.R.N.A.S. Civico and Di Cristina, Palermo, Italy.

Marco De Fabritiis, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, Forlì, Italy.

Maria Maddalena Conte, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, University Hospital Maggiore della Carità, Novara, Italy.

Massimo Manes, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Umberto Parini Hospital, Aosta, Italy.

Yuri Battaglia, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Hospital-University St Anna, Ferrara, Italy.

Francesco Fontana, Nephrology and Dialysis Unit, Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria, Modena, Italy.

Loreto Gesualdo, Nephrology, Dialysis and Transplantation, Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation, University of Bari, Bari, Italy.

PATIENT CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all of the enrolled patients or their parents/legal guardians.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Simeone Andrulli designed the study, wrote the study protocol, analysed the data, and wrote the first draft of the paper. Umberto Venere and Domenico Roselli participated in data collection. Umberto Venere, Domenico Roselli and Simeone Andrulli participated in data quality control. Sandro Feriozzi, Francesca Bruno and Michele Rossini contributed to classifying the histopathological findings. All of the authors assisted in the preparation of the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hergesell O, Felten H, Andrassy Ket al. . Safety of ultrasound-guided percutaneous renal biopsy—retrospective analysis of 1,090 consecutive cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998; 13: 975–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burstein DM, Korbet SM, Schwartz MM. The use of the automatic core biopsy system in percutaneous renal biopsies: a comparative study. Am J Kidney Dis 1993; 22: 545–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Al Turk AA, Estiverne C, Agrawal PRet al. . Trends and outcomes of the use of percutaneous native kidney biopsy in the United States: 5-year data analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample. Clin Kidney J 2018; 11: 330–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halimi JM, Gatault P, Longuet Het al. . Major bleeding and risk of death after percutaneous native kidney biopsies: a french nationwide cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 15: 1587–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corapi KM, Chen JL, Balk EMet al. . Bleeding complications of native kidney biopsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2012; 60: 62–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poggio ED, McClelland RL, Blank KNet al. Kidney Precision Medicine Project . Systematic review and meta-analysis of native kidney biopsy complications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 15: 1595–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schena FP for The Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology . Survey of the Italian registry of renal biopsies. Frequency of the renal diseases for 7 consecutive years. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1997; 12: 418–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gesualdo L, Di Palma AM, Morrone LFet al. . The Italian experience of the national registry of renal biopsies. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 890–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Charu V, O'Shaughnessy MM, Chertow GMet al. . Percutaneous kidney biopsy and the utilization of blood transfusion and renal angiography among hospitalized adults. Kidney Int Rep 2019; 4: 1435–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tondel C, Vikse BE, Bostad Let al. . Safety and complications of percutaneous kidney biopsies in 715 children and 8,573 adults in Norway 1988–2010. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 7: 1591–1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doyle AJ, Gregory MC, Terreros DA.. Percutaneous native renal biopsy: comparison of a 1.2-mm spring-driven system with a traditional 2-mm hand-driven system. Am J Kidney Dis 1994; 23: 498–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hogan JJ, Owen JG, Blady SJet al. TRIDENT Study Investigators . The feasibility and safety of obtaining research kidney biopsy cores in patients with diabetes: an interim analysis of the TRIDENT Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020; 15: 1024–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gigante A, Barbano B, Sardo Let al. . Hypercoagulability and nephrotic syndrome. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 2014; 12: 512–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aaltonen S, Finne P, Honkanen E. Outpatient kidney biopsy: a single center experience and review of literature. Nephron 2020; 144: 14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manno C, Strippoli GFM, Arnesano Let al. . Predictors of bleeding complications in percutaneous ultrasound-guided renal biopsy. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 1570–1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palsson R, Short SAP, Kibbelaar ZAet al. . Bleeding complications after percutaneous native kidney biopsy: results from the Boston kidney biopsy cohort. Kidney Int Rep 2020; 5: 511–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stratta P, Canavese C, Marengo Met al. . Risk management of renal biopsy: 1387 cases over 30 years in a single centre. Eur J Clin Invest 2007; 37: 954–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roccatello D, Sciascia S, Rossi Det al. . Outpatient percutaneous native renal biopsy: safety profile in a large monocentric cohort. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e015243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Korbet SM, Volpini KC, Whittier WL. Percutaneous renal biopsy of native kidneys: a single-center experience of 1,055 biopsies. Am J Nephrol 2014; 39: 153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carrington CP, Williams A, Griffiths DFet al. . Adult day-case renal biopsy: a single-centre experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26: 1559–1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]