ABSTRACT

For the first time in many years, guideline-directed drug therapies have emerged that offer substantial cardiorenal benefits, improved quality of life and longevity in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and type 2 diabetes. These treatment options include sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. However, despite compelling evidence from multiple clinical trials, their uptake has been slow in routine clinical practice, reminiscent of the historical evolution of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker use. The delay in implementation of these evidence-based therapies highlights the many challenges to optimal CKD care, including: (i) clinical inertia; (ii) low CKD awareness; (iii) suboptimal kidney disease education among patients and providers; (iv) lack of patient and community engagement; (v) multimorbidity and polypharmacy; (vi) challenges in the primary care setting; (vii) fragmented CKD care; (viii) disparities in underserved populations; (ix) lack of public policy focused on health equity; and (x) high drug prices. These barriers to optimal cardiorenal outcomes can be ameliorated by a multifaceted approach, using the Chronic Care Model framework, to include patient and provider education, patient self-management programs, shared decision making, electronic clinical decision support tools, quality improvement initiatives, clear practice guidelines, multidisciplinary and collaborative care, provider accountability, and robust health information technology. It is incumbent on the global kidney community to take on a multidimensional perspective of CKD care by addressing patient-, community-, provider-, healthcare system- and policy-level barriers.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, a number of new drug therapies have emerged that represent a paradigm shift in the treatment of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). These include sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA) and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP1-RA). In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration designated the SGLT2i, dapagliflozin, as a breakthrough therapy for the treatment of patients with CKD, with or without T2D—an unprecedented moment in the history of nephrology given that no prior breakthrough designation has been granted for a potential kidney disease therapy [1].

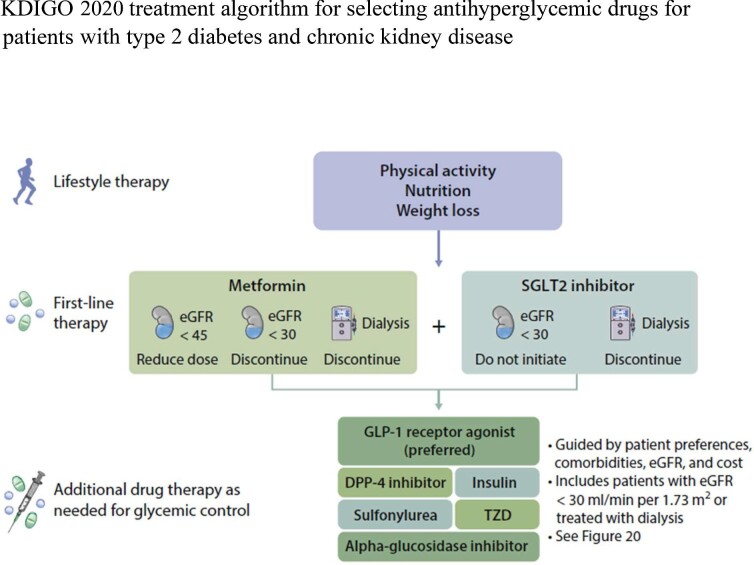

The emergence of these highly effective therapies led to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2020 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in CKD [2]. Both metformin and SGLT2i are preferred medications for patients with T2D, CKD and an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Fig. 1). For those who have not achieved individualized glycemic targets despite use of metformin and SGLT2i, or who are unable to use those medications, a long-acting GLP1-RA is recommended. Further, the American Diabetes Association recently updated its recommendation that for patients with T2D and CKD treated with maximum tolerated doses of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), addition of the MRA, finerenone, should be considered to improve cardiovascular outcomes and reduce the risk of CKD progression [3–5].

Figure 1:

KDIGO 2020 treatment algorithm for selecting antihyperglycemic drugs for patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. KDIGO, Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; DPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase-4; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; SGLT2, sodium–glucose cotransporter-2; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

However, despite compelling evidence from multiple clinical trials on the benefits of these cardiorenal therapies and recommendations by international organizations [2, 3, 6–9], uptake has been slow. Based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2017–20 [10], the overall prevalence of SGLT2i and GLP1-RA use was 5.8% and 4.4%, respectively, in adults with T2D and eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2. SGLT2i and GLP1-RA were similarly underutilized (2.8% and 3.9%, respectively) in a large US cohort of more than 300 000 patients with T2D and cardiovascular disease (CVD) during 2018 [11]. In the UK, although use of SGLT2i and GLP1-RA in adults with T2D has increased, overall adoption remained low in 2019, with slightly less use in those with CVD despite this group being likely to gain the most benefit (SGLT2i: 9.8% and 13.8%; GLP1-RA: 4.3% and 4.9%) in those with and without CVD, respectively [12].

The barriers to implementation of these newer agents mirror the historical evolution of ACEi and ARB use. A large number of candidates for renin–angiotensin–system inhibition do not receive them, at least in part because of concern about hyperkalemia and initial decrease in eGFR [13]. ACEi/ARB use in patients with CKD in the US was 40% by 2014 but seemed to have plateaued after the early 2000s [14], and initiation of ACEi/ARB therapy within the first year after CKD diagnosis in patients with T2D was only about 17% [15]. However, ACEi/ARB use appears higher in Europe and Canada. The German Chronic Kidney Disease Study investigators reported that over 80% of their cohort received either an ACEi or ARB [16], and a Canadian registry study showed that among patients with CKD and T2D, ACEi/ARB use was 76% [17]. This global variation in practice patterns may be partly related to differences in healthcare systems and delivery.

BARRIERS AND STRATEGIES IN IMPLEMENTING NEW CARDIORENAL THERAPIES FOR CKD

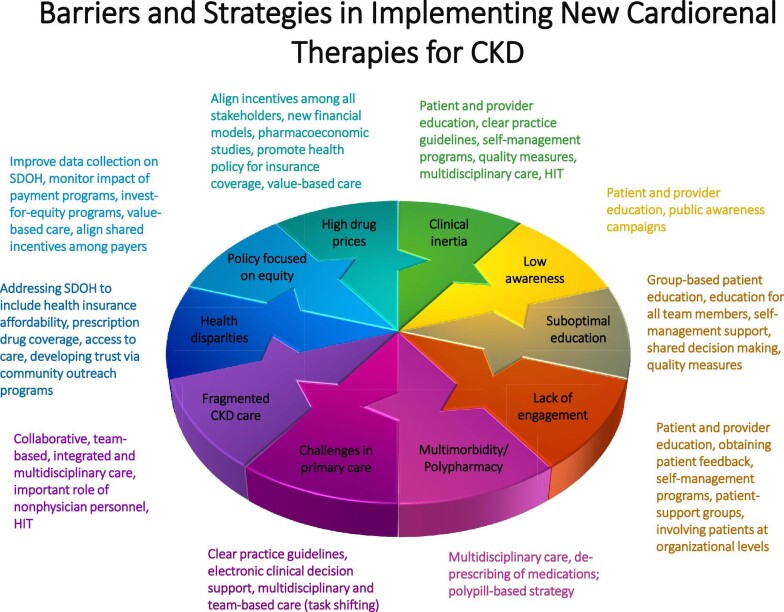

The delay in implementation of newer guideline-directed cardiorenal therapies highlights the many challenges to optimal care in patients with CKD and T2D [18, 19]. Overcoming these barriers will likely require a combination of patient-, community-, provider-, healthcare system- and public policy-level approaches (Fig. 2).

Figure 2:

Barriers and strategies in implementing new cardiorenal therapies for chronic kidney disease. HIT, health information technology; SDOH, social determinants of health.

Clinical inertia

Clinical inertia has been proposed as a key driver limiting initiation of SGLT2i, nonsteroidal MRA and GLP1-RA in eligible patients with cardiorenal risk [20, 21]. Phillips et al. [22] first highlighted this concept to indicate a “failure of health care providers to initiate or intensify therapy when indicated.” Maintaining the status quo—recognition of the problem, but failure to act—is common in management of patients with asymptomatic chronic illness. Clinical inertia related to the management of diabetes, hypertension and lipid disorders may contribute to up to 80% of cardiovascular events [23]. It is therefore a leading cause of potentially preventable adverse events, disability, death and excess medical care costs. Its causes are multidimensional [20, 22, 23]. Provider factors include: (i) clinicians overrate the quality of the care they already deliver and underestimate the number of patients in need of intensified pharmacotherapy; (ii) providers make “soft excuses” or rationalizations to avoid advancing therapy (perceptions about patient nonadherence, and fear of drug side effects despite substantial benefits outweighing risks); and (iii) lack of knowledge, experience and training with the new therapies. Patient factors include unawareness of the need to intensify therapy, denial or overly optimistic views of their health risks, and avoidance of increased expenses and side effects associated with more intensive therapy. Health system factors include limited ability to capture real-time data to monitor the quality of care and identify patients in need of more intensive care, lack of active outreach to patients in need of care and failure to implement decision support strategies. Overcoming clinical inertia requires a multipronged approach to address the patient, provider and system-level factors. These include educational programs for both patients and providers with clear practice guidelines, patient empowerment through self-management programs, development of quality measures and active feedback to providers, care delivery through multidisciplinary teams and effective use of information systems [20, 24]. These multifaceted measures would not only address the initial uptake of cardiorenal therapies but also the critical aspect of persistent medication use and long-term adherence.

Low CKD awareness

Although 15% of adults in the USA are estimated to have CKD, up to 90% do not know they have CKD, and even 40% of those with severe CKD do not know they have CKD [25]. Although the wording of the questions (e.g. “weak or failing kidneys,” “kidney problem,” “kidney disease”) may lead to widely different estimates of CKD awareness, a meta-analysis of 32 studies showed low awareness overall (19.2%), with most studies reporting <50% of individuals with CKD being aware of their condition [26]. Despite some evidence of benefits from patient awareness of CKD [27, 28], a growing number of studies have failed to demonstrate associations between baseline CKD awareness and healthy behaviors [e.g. avoidance of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)], ACEi/ARB use, blood pressure (BP) control, glycemic control, or changes in eGFR and albuminuria [29–31]. Thus, robust trial data are needed to determine whether patient awareness of the early stages of CKD promotes uptake of guideline-based therapies and improves outcomes. Awareness alone may not be sufficient to improve self-management or chronic disease management. Awareness efforts should be integrated with other interventions such as patient and healthcare provider education about CKD, as there is evidence that provider awareness of patient CKD improves BP control [32]. In addition, public awareness campaigns are important in raising CKD awareness. In March 2020, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched a nationwide kidney risk awareness campaign in collaboration with the National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology, responding to the Executive Order on the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) initiative [33]. The importance of public CKD awareness is further underscored as a national objective of the Healthy People 2030 initiative [34].

Suboptimal kidney disease education among patients and providers

The large gaps in CKD awareness highlight the need for effective education about kidney disease. Patient education is associated with improved outcomes across the CKD spectrum and is uniformly supported by international guidelines and organizations [35]. However, more research is needed to assess the impact of patient education in the earlier stages of CKD on clinical outcomes [36]. Barriers to improving patient education are well documented, including low baseline understanding of CKD health risks, low health literacy [37] and numeracy [38], and limited educational materials at a literacy level suitable for at-risk populations [39]. Although lack of time is cited by physicians as a barrier to CKD education [40], many physicians feel inadequately prepared to explain kidney disease to their patients [41]. Further, patient education is time-consuming and the kidney disease education benefit for Medicare beneficiaries in the USA has been underutilized [42].

A growing number of diverse investigators are engaged in meeting the educational needs of the communities with the greatest burden of kidney disease [43]. Strategies that have been shown to make kidney disease education more effective focus on patients with progressive disease, not on all people who meet laboratory criteria for a CKD diagnosis. Specific approaches to improve CKD education include emphasis on self-management support, shared decision making about treatment options, engagement of the entire interdisciplinary team in kidney disease education [44], group-based educational programs and incorporating performance measures related to patient education in quality improvement efforts.

Lack of patient and community engagement

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines patient engagement as “the process of building the capacity of patients, families, carers, as well as health care providers, to facilitate and support the active involvement of patients in their own care, in order to enhance safety, quality and people-centredness of health care service delivery” [45]. Patient engagement can lead to better health outcomes and improvements in quality and patient safety, and help control healthcare costs [46]. A systematic review found that patient engagement can inform patient and provider education and policies, as well as enhance service delivery and governance [47]. Factors that influence engagement are related to patients (beliefs about patient's role, health literacy), organization (hospital policies and practices) and society (local and national regulations and policies) [46]. Practical steps to improve patient engagement include educating patients and providers, obtaining feedback from patients, and involving patients at organizational levels (e.g. patient advisory committees) [45]. Meaningful engagement begins with empowering patients in daily self-care. Self-management skills involve focusing on illness needs, activating resources and the process of living with a chronic illness [48]. Diabetes self-management education programs have been shown to be efficacious and cost-effective in enhancing self-management, with improvements in patients’ knowledge, skills and motivation leading to improved biomedical, behavioral and psychosocial outcomes [49]. The KDIGO guidelines recommend that a structured self-management educational program be implemented for people with CKD and T2D, taking into consideration the local context, culture and availability of resources [2]. Thus, patient engagement strategies should be broadened to the community level through outreach efforts, recognizing the importance of social networks such as patient-support groups.

Multimorbidity and polypharmacy

Even at early stages, CKD commonly occurs in the context of multiple comorbid conditions [50] and polypharmacy, generally defined as regular use of five or more medications daily [51]. In a large population-based cohort study of Canadian adults, nephrology patients had the highest mean number of comorbidities (4.2; 95% confidence interval 4.2–4.3) and highest mean number of prescribed medications (14.2; 95% confidence interval 14.2–1.43), compared with those seen by primary care physicians and 10 other subspecialists [52]. In a recent European study, the prevalence of polypharmacy was 62%–86% in patients with Stage 1–3b CKD (with a median medication number of eight per day), with concurrent diabetes mellitus as a significant risk factor for polypharmacy [16]. In CKD, polypharmacy is associated with poor adherence, adverse drug reactions/interactions, CKD progression, morbidity and mortality [53]. Care providers should focus on multidisciplinary management with an eye toward “de-prescribing” of unnecessary or problematic medications and ensuring that medications are appropriate based on their indications and risks/benefits. Potential targets include proton pump inhibitors, some oral hypoglycemic agents, NSAIDs, benzodiazepines, gabapentin/pregabalin, diuretics, some anti-hypertensives, and potassium binders [54–56]. One study showed that 58% of all drugs could be discontinued in a cohort of community-dwelling elderly patients, without significant adverse events or deaths attributable to discontinuation, and 88% of patients reported global improvement in health [57]. Although the sample size was small (n = 70), the study findings suggest that it is feasible to safely reduce polypharmacy with the added benefit of enhanced quality of life.

SGLT2i and GLP1-RA are attractive replacements for other antidiabetic agents that do not provide the same cardiorenal benefits. SGLT2i have diuretic, antihypertensive and anti-proteinuric effects, allowing simplification of medication regimens and de-prescribing of less desirable agents [54, 58]. In addition, this may be desirable because the beneficial effects of SGLT2i on renal outcomes may be blunted in the setting of polypharmacy [59]. Initiation of new cardiorenal agents to the medication regimen should be used as an opportunity to scrutinize and possibly deprescribe or dose adjust other medications. A polypill-based strategy (fixed-dose combination of medications) warrants investigation since it has the potential to improve adherence to therapy, lower costs and enhance safety profiles [60].

Challenges in the primary care setting

The majority of patients with CKD are managed in the primary care setting. Given that the global nephrology workforce is unable to meet the demands of the increasing CKD population, primary care providers play a crucial role in early intervention to prevent or delay CKD progression. However, primary care providers face multiple challenges [61–63], including: (i) lack of provider awareness and knowledge of CKD, risk assessment and guideline-directed interventions; (ii) complex patient characteristics; (iii) CKD not considered high priority versus competing health conditions; (iv) high work volume and insufficient time; (v) inadequate collaboration and poor access to nephrologists and other subspecialists; and (vi) difficulties with the process of specialist referral and lack of clear parameters for timely referral to nephrologists. The 2017 International Society of Nephrology Global Kidney Health Atlas survey reported that non-nephrologist physician-related factors (availability, access, knowledge and attitude) are some of the leading barriers to optimal kidney disease care [64]. These barriers can be ameliorated by concise and consistent practice guidelines that are transparent in the development process, actionable and patient-centered [65], automated CKD decision support tool integrated into the electronic health records (e.g. electronic alerts, lab decision support) [66] and team-based care (e.g. task shifting from physicians to allied healthcare professionals such as nurses and pharmacists) [67, 68].

Fragmented CKD care

The integration of evidence-based therapeutics in clinical practice is impacted by the fragmentation of the US healthcare delivery system [69, 70]. Siloed care can exacerbate clinical inertia in starting SGLT2i or GLP1-RA by nephrologists and cardiologists given the added responsibilities of managing diabetes. A more collaborative, team-based and integrated care approach may result in better outcomes, with the participation of physicians and nonphysician personnel (e.g. trained nurses and dieticians, pharmacists, healthcare assistants, community healthcare workers and peer supporters) [2]. Although data are lacking in patients with early CKD and T2D, a systematic review of 11 studies on patients with Stage 3–5 CKD (41% had diabetes) revealed that multidisciplinary care slows CKD progression and decreases mortality, the risk of kidney replacement therapy (KRT), the need for emergent dialysis and healthcare costs [71]. Multidisciplinary care is predicated on close communication and active collaboration as well as defined roles and responsibilities for each member of the CKD team. Care coordination is facilitated by an interoperable health information technology system, allowing patient data to be easily accessible across providers and multiple healthcare settings (inpatient and outpatient facilities, emergency departments, pharmacies, extended and long-term care facilities) [72].

Disparities in underserved populations

Disparities in cardiorenal health remain pervasive, with a higher burden of CVD [73], cardiovascular death [74] and advanced CKD [75, 76] being greatest in the Black population. However, Black patients are less likely to receive novel therapeutics than White patients [77, 78]. A recent analysis of commercially insured US patients with T2D showed that Black race, female sex and lower household incomes were associated with lower rates of SGLT2i use overall and among those with heart failure (HF), CVD and CKD [79]. As noted by the study investigators, the observed disparities may be even greater among those with traditional Medicare or Medicaid or those without private healthcare insurance [79]. While the SGLT2i trials are limited by small sample sizes of Black patients (∼5% or less) [80–82], subgroup analyses suggest that the positive impact of SGLT2i are also present among Black subjects. Taken together, these findings highlight racial inequities in access to evidence-based therapies. Major reasons for both the low and disparate use of evidence-based care are high costs driven by variations in health insurance affordability, medication coverage, provider access and other factors, such as trust of a health system that too often demonstrates an overriding interest in profit and prioritizing affluent members of society. It is imperative to overcome barriers such as these in order to deliver high quality and affordable healthcare to all patients.

Lack of public policy focused on health equity

The WHO has outlined three principles of global action to address health injustices: (i) improve living and working conditions; (ii) ensure equitable distribution of power, money and resources; and (iii) measure health inequity and educate healthcare workers and the wider society on how inequity in the social determinants of health (SDOH) lead to disparities [83]. These principles can help create a foundation for health equity, reduce avoidable risk factors for CKD and redirect resources towards CKD prevention and early intervention [84]. In the USA, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Service has committed to make health equity the first “pillar” of its strategic vision [85]. Five strategies have been proposed to advance health equity through payment and delivery system reform: (i) improve data collection on race/ethnicity and SDOH; (ii) monitor the impact of payment programs on health equity; (iii) shift from pay-for-performance approaches to invest-for-equity programs (e.g. providing greater resources to providers in underserved communities); (iv) ensure that under-resourced patients and health systems participate in value-based payment models that could improve quality and increase affordability; and (v) align payers (Medicare, Medicaid, commercial) to provide consistent incentives for providers and experiences for patients [86]. We remain cautiously optimistic that this strategic vision can become a reality.

High drug prices

High drug cost, low reimbursement rates and the financial burden of clinical monitoring and adjustments represent an important impediment to guideline-directed cardiorenal therapy, even in wealthy nations. Out-of-pocket costs for Medicare Part D beneficiaries in 2019 were at least $1000 annually for an SGLT2i and greater than $1500 for an GLP1-RA, and may not be affordable to many older or socially disadvantaged patients [87]. Given their renal and cardiac protective properties, the upstream costs of these agents should be weighed against the high downstream costs for patients with CKD and T2D. An analysis of claims data for adults with CKD and T2D showed that the estimated 4-month CKD management costs ranged from $7725 for Stage 1 to 2 disease to $11 879 for Stage 5 (without KRT). Acute event costs for CKD complications were $31 063 for HF, $21 087 for stroke and $21 016 for myocardial infarction in the first 4 months after the incident event [88]. A microsimulation model based on data from the Canagliflozin and Renal Endpoints in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation (CREDENCE) study showed that canagliflozin improved patient outcomes while reducing net costs from the National Health System perspective in the UK [89]. A Markov model of an US patient population with CKD, T2D and HF demonstrated that dapagliflozin has the potential to reduce cardiorenal disease prevalence by 8% and direct healthcare costs by 3.6% by 2030 [90]. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies demonstrated that newer antidiabetic medications (e.g. SGLT2i, GLP1-RA) were cost effective from both payer and societal perspectives, compared with insulin, thiazolidinediones and sulfonylureas [91]. Despite these favorable cost-effectiveness data, there are currently insufficient incentives for the pharmaceutical industry to lower drug prices. Recently, the American Society of Nephrology Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative (DKD-C) Task Force has called for healthcare systems, federal agencies, payers and pharmaceutical companies to align incentives, partner in new financial models, conduct further pharmacoeconomic studies, promote health policy for insurance coverage, and collaborate on value-based care defined as health outcomes achieved per dollar spent [92], in order to increase uptake of newer cardiorenal therapies [93].

CHRONIC CARE MODEL IN CKD

The fragmentation of the US healthcare delivery system is a fundamental barrier to optimal CKD care. It leads to poor patient experiences; lack of communication and coordination resulting in medical errors, waste and duplicative services; absence of peer accountability and quality improvement infrastructure; and ultimately poor overall quality and lower value of care [69].

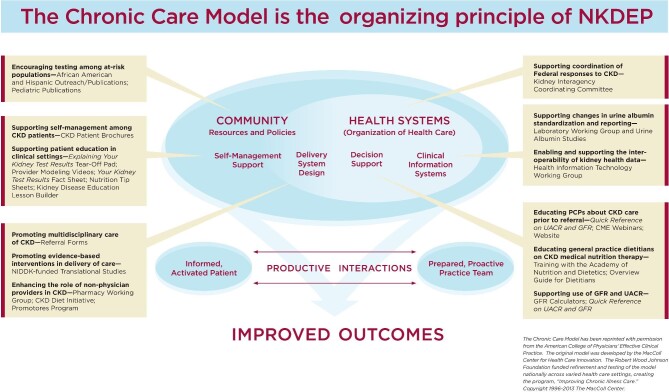

The Chronic Care Model (CCM) is an evidence-based and widely implemented framework to improve chronic illness management [94, 95]. The CCM aims to improve patient outcomes by supporting an informed, activated patient and a prepared, proactive, multidisciplinary healthcare team. It has six essential components: a proactive delivery system design, self-management support, decision support tools, functional clinical information systems, community resources and effective policy, and quality-oriented healthcare organization. In practice, this promotes systems thinking and results in a “learning health system” where data and experience are utilized to improve patient safety, quality of care and workplace environment [96]. The CCM was the guiding principle for the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)/National Kidney Disease Education Program's (NKDEP) comprehensive educational efforts to foster a population health approach to CKD [97] (Fig. 3).

Figure 3:

The Chronic Care Model as the guiding principle for the National Kidney Disease Education Program's (NKDEP) comprehensive educational efforts to foster a population health approach to chronic kidney disease (CKD). CME, continuing medical education; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; NIDDK, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; PCP, primary care provider; UACR, urine albumin-creatinine ratio.

Population-based approaches to kidney disease prevention and management, inspired by the CCM, using existing infrastructure and with limited additional cost, have been shown to be effective. For instance, American Indians served by the Indian Health Service experienced a rapid rise in the prevalence of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in the 1970s and 1980s. In response, an interdisciplinary, primary care–based approach to implementing preventive therapies was initiated which, over the next two decades, led to a 54% reduction in incidence rates of diabetes-attributed ESKD [98]. This approach was based on the consistent implementation of simple measures by all members of the primary care team, in a system built on the principles of population health. These included routine screening for kidney disease using simple blood and urine tests, establishment of simple and easy-to-implement guidelines on management and monitoring of CKD and its complications, and the development of a suite of clinical tools and educational materials for patients and providers. This approach was promoted through continuing education activities for all healthcare professionals and paraprofessionals to enable them to feel comfortable and competent to manage patients with kidney disease and educate patients about CKD and their treatment choices [97]. These simple evidence-based interventions were highly effective in improving outcomes in a high-risk population with fewer than half the per capita healthcare resources available compared with the US civilian population.

CONCLUSIONS

For the first time in many years, there is emergence of guideline-directed drug therapies that offer substantial cardiorenal benefits, improved quality of life and longevity in patients with CKD and T2D. The multiple challenges of implementing these drug treatments in daily clinical practice will require a renewed focus on increasing CKD awareness, detection and early interventions. Restructuring of the current reimbursement systems is much needed to incentivize all stakeholders, including healthcare systems and clinicians, to prioritize CKD care and reduce progression to ESKD. Furthermore, barriers to optimal CKD care can be ameliorated by a multifaceted approach, using the CCM framework and providing open access to high value care for all.

Contributor Information

Robert Nee, Nephrology Service, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA; Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Christina M Yuan, Nephrology Service, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA; Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Andrew S Narva, College of Agriculture, Urban Sustainability and Environmental Studies, University of the District of Columbia, Washington, DC, USA.

Guofen Yan, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA, USA.

Keith C Norris, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

FUNDING

G.Y. is supported in part by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant R01DK112008. K.C.N. is supported by NIH grants UL1TR000124 and P30AG021684.

DISCLAIMER

The views expressed in this review article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army/Navy/Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the United States government.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brosius FC, Cherney D, Gee POet al. Transforming the care of patients with diabetic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021;16:1590–600. 10.2215/CJN.18641120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Diabetes Work Group . KDIGO 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2020;98:S1–115. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32998798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee , Draznin B, Aroda VR, Bakris Get al.11. Chronic kidney disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022;45:S175–84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34964873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Addendum. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022;45(Suppl. 1):S144–S174. Diabetes Care 2022;45:2178–81. 10.2337/dc22-ad08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Erratum . 11. Chronic kidney disease and risk management: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022;45 (Suppl. 1:S175–S184. Diabetes Care 2022;45:758. 10.2337/dc22-er03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rangaswami J, Bhalla V, de Boer IHet al. Cardiorenal protection with the newer antidiabetic agents in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020;142:e265–86. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KKet al. 2020 Expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology solution set oversight committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:1117–45. 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas Aet al. 2019 Update to: management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2020;43:487–93. 10.2337/dci19-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger Get al. Consensus statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm - 2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract 2020;26:107–39. 10.4158/CS-2019-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Limonte CP, Hall YN, Trikudanathan Set al. Prevalence of SGLT2i and GLP1RA use among US adults with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2022;36:108204. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2022.108204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nelson AJ, O'Brien EC, Kaltenbach LAet al. Use of lipid-, blood pressure-, and glucose-lowering pharmacotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Network Open 2022;5:e2148030. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Farmer RE, Beard I, Raza SIet al. Prescribing in type 2 diabetes patients with and without cardiovascular disease history: a descriptive analysis in the UK CPRD. Clin Ther 2021;43:320–35. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tuttle KR, Cherney DZ; Diabetic Kidney Disease Task Force of the American Society of Nephrology . Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition heralds a call-to-action for diabetic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020;15:285–8. 10.2215/CJN.07730719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murphy DP, Drawz PE, Foley RN.. Trends in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker use among those with impaired kidney function in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019;30:1314–21. 10.1681/ASN.2018100971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fried LF, Petruski-Ivleva N, Folkerts Ket al. ACE inhibitor or ARB treatment among patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Am J Manag Care 2021;27:S360–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34878753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schmidt IM, Hübner S, Nadal Jet al. Patterns of medication use and the burden of polypharmacy in patients with chronic kidney disease: the German Chronic Kidney Disease study. Clin Kidney J 2019;12:663–72. 10.1093/ckj/sfz046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chu L, Fuller M, Jervis Ket al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes: the Canadian REgistry of Chronic Kidney Disease in Diabetes Outcomes (CREDO) Study. Clin Ther 2021;43:1558–73. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neumiller JJ, Alicic RZ, Tuttle KR.. Overcoming barriers to implementing new therapies for diabetic kidney disease: lessons learned. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2021;28:318–27. 10.1053/j.ackd.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee . 1. Improving care and promoting health in populations: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care 2022;45:S8–16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34964872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Andreozzi F, Candido R, Corrao Set al. Clinical inertia is the enemy of therapeutic success in the management of diabetes and its complications: a narrative literature review. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2020;12:52. 10.1186/s13098-020-00559-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schernthaner G, Shehadeh N, Ametov ASet al. Worldwide inertia to the use of cardiorenal protective glucose-lowering drugs (SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA) in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2020;19:185. 10.1186/s12933-020-01154-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CBet al. Clinical inertia. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:825–34. 10.7326/0003-4819-135-9-200111060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O'Connor PJ, Sperl-Hillen JAM, Johnson PEet al. Clinical inertia and outpatient medical errors. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ESet al. (eds). Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 2: Concepts and Methodology). Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2005. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20513/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khunti K, Jabbour S, Cos Xet al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes: barriers and solutions for improving uptake in routine clinical practice. Diabetes Obes Metab 2022;24:1187–96. 10.1111/dom.14684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2021 . https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/pdf/Chronic-Kidney-Disease-in-the-US-2021-h.pdf (27 May 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chu CD, Chen MH, McCulloch CEet al. Patient awareness of CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of patient-oriented questions and study setting. Kidney Med 2021;3:576–85.e1. 10.1016/j.xkme.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wright-Nunes JA, Luther JM, Ikizler TAet al. Patient knowledge of blood pressure target is associated with improved blood pressure control in chronic kidney disease. Patient Educ Couns 2012;88:184–8. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wright-Nunes JA, Wallston KA, Eden SKet al. Associations among perceived and objective disease knowledge and satisfaction with physician communication in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2011;80:1344–51. 10.1038/ki.2011.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tuot DS, Plantinga LC, Judd SEet al. Healthy behaviors, risk factor control and awareness of chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 2013;37:135–43. 10.1159/000346712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tummalapalli SL, Vittinghoff E, Crews DCet al. Chronic kidney disease awareness and longitudinal health outcomes: results from the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study. Am J Nephrol 2020;51:463–72. 10.1159/000507774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tuot DS, Plantinga LC, Hsu CYet al. Is awareness of chronic kidney disease associated with evidence-based guideline-concordant outcomes? Am J Nephrol 2012;35:191–7. 10.1159/000335935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ravera M, Noberasco G, Weiss Uet al. CKD awareness and blood pressure control in the primary care hypertensive population. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;57:71–77. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. US Department of Health and Human Services . Advancing American Kidney Health: 2020 Progress Report. https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/advancing-american-kidney-health-2020-progress-report (28 May 2022, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. US Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy People 2030 . Increase the proportion of adults with chronic kidney disease who know they have it – CKD-02. Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/chronic-kidney-disease/increase-proportion-adults-chronic-kidney-disease-who-know-they-have-it-ckd-02 (28 May 2022, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Narva AS, Norton JM, Boulware LE.. Educating patients about CKD: the path to self-management and patient-centered care. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:694–703. 10.2215/CJN.07680715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wright Nunes JA. Education of patients with chronic kidney disease at the interface of primary care providers and nephrologists. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2013;20:370–8. 10.1053/j.ackd.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fraser SD, Roderick PJ, Casey Met al. Prevalence and associations of limited health literacy in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:129–37. 10.1093/ndt/gfs371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Abdel-Kader K, Dew MA, Bhatnagar Met al. Numeracy skills in CKD: correlates and outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:1566–73. 10.2215/CJN.08121109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tuot DS, Davis E, Velasquez Aet al. Assessment of printed patient-educational materials for chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol 2013;38:184–94. 10.1159/000354314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Greer RC, Crews DC, Boulware LE.. Challenges perceived by primary care providers to educating patients about chronic kidney disease. J Ren Care 2012;38:174–81. 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2012.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abdel-Kader K, Greer RC, Boulware LEet al. Primary care physicians’ familiarity, beliefs, and perceived barriers to practice guidelines in non-diabetic CKD: a survey study. BMC Nephrol 2014;15:64. 10.1186/1471-2369-15-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Davis JS, Zuber K.. The nephrology interdisciplinary team: an education synergism. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2014;21:338–43. 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tuot DS, Diamantidis CJ, Corbett CFet al. The last mile: translational research to improve CKD outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;9:1802–5. 10.2215/CJN.04310514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zuber K, Davis J.. Kidney disease education: a niche for PAs and NPs. JAAPA 2013;26:42–7. 10.1097/01.JAA.0000431502.08251.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patient Engagement: Technical Series on Safer Primary Care . Geneva: World Health Organization. 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252269 (28 May 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer Met al. Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff 2013;32:223–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando Eet al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2018;13:98. 10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grey M, Schulman-Green D, Knafl Ket al. A revised self- and family management framework. Nurs Outlook 2015;63:162–70. 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chatterjee S, Davies MJ, Heller Set al. Diabetes structured self-management education programmes: a narrative review and current innovations. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:130–42. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fraser SD, Taal MW.. Multimorbidity in people with chronic kidney disease: implications for outcomes and treatment. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2016;25:465–72. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett Let al. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatrics 2017;17:230. 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Manns BJet al. Comparison of the complexity of patients seen by different medical subspecialists in a universal health care system. JAMA Network Open 2018;1:e184852. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kimura H, Tanaka K, Saito Het al. Association of polypharmacy with kidney disease progression in adults with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021;16:1797–804. 10.2215/CJN.03940321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Triantafylidis LK, Hawley CE, Perry LPet al. The role of deprescribing in older adults with chronic kidney disease. Drugs Aging 2018;35:973–84. 10.1007/s40266-018-0593-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Li J, Fagbote CO, Zhuo Met al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors for diabetic kidney disease: a primer for deprescribing. Clin Kidney J 2019;12:620–8. 10.1093/ckj/sfz100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mohottige D, Manley HJ, Hall RK. Less is more: deprescribing medications in older adults with kidney disease: a review. Kidney360 2021;2:1510–22. 10.34067/KID.0001942021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Garfinkel D, Mangin D.. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1648–54. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Giaccari A, Pontremoli R, Perrone Filardi P. SGLT-2 inhibitors for treatment of heart failure in patients with and without type 2 diabetes: a practical approach for routine clinical practice. Int J Cardiol 2022;351:66–70. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kobayashi K, Toyoda M, Hatori Net al. Polypharmacy influences the renal composite outcome in patients treated with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. Clin Transl Sci 2022;15:1050–62. 10.1111/cts.13222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Muñoz D, Uzoije P, Reynolds Cet al. Polypill for cardiovascular disease prevention in an underserved population. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1114–23. 10.1056/NEJMoa1815359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bello AK, Johnson DW.. Educating primary healthcare providers about kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022;18:133–4. 10.1038/s41581-021-00527-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shahinian VB, Saran R.. The role of primary care in the management of the chronic kidney disease population. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2010;17:246–53. 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. American Society of Nephrology Diabetic Kidney Disease Collaborative (DKD-C) . Diabetic Kidney Disease Strategy Conference: Implementing New Diabetic Kidney Disease Treatments-Time to Act. https://www.asn-online.org/dkd-c/ (29 May 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bello AK, Levin A, Tonelli Met al. Global Kidney Health Atlas: A report by the International Society of Nephrology on the current state of organization and structures for kidney care across the globe. Brussels, Belgium: International Society of Nephrology, 2017. https://www.theisn.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/GKDAtlas_2017_FinalVersion-1.pdf (29 May 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 65. van der Veer SN, Tomson CR, Jager KJet al. Bridging the gap between what is known and what we do in renal medicine: improving implementability of the European Renal Best Practice guidelines. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014;29:951–7. 10.1093/ndt/gft496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Peralta CA, Livaudais-Toman J, Stebbins Met al. Electronic decision support for management of CKD in primary care: a pragmatic randomized trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2020;76:636–44. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sperati CJ, Soman S, Agrawal Vet al. National Kidney Foundation Education Committee . Primary care physicians’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to management of chronic kidney disease: a mixed methods study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0221325. 10.1371/journal.pone.0221325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Leong SL, Teoh SL, Fun WHet al. Task shifting in primary care to tackle healthcare worker shortages: an umbrella review. Eur J Gen Pract 2021;27:198–210. 10.1080/13814788.2021.1954616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shih A, Davis K, Schoenbaum S, et al. Organizing the U.S. Health Care Delivery System for High Performance, The Commonwealth Fund, August 2008. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2008/aug/organizing-us-health-care-delivery-system-high-performance (29 May 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rangaswami J, Tuttle K, Vaduganathan M.. Cardio-Renal-Metabolic care models: toward achieving effective interdisciplinary care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2020;13:e007264. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hsu HT, Chiang YC, Lai YHet al. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2021;18:33–41. 10.1111/wvn.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Drawz PE, Archdeacon P, McDonald CJet al. CKD as a model for improving chronic disease care through electronic health records. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:1488–99. 10.2215/CJN.00940115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SEet al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;135:e146–603. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ESet al. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation 2005;111:1233–41. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. McClellan W, Warnock DG, McClure Let al. Racial differences in the prevalence of chronic kidney disease among participants in the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17:1710–5. 10.1681/ASN.2005111200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Crews DC, Charles RF, Evans MKet al. Poverty, race, and CKD in a racially and socioeconomically diverse urban population. Am J Kidney Dis 2010;55:992–1000. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Nathan AS, Geng Z, Dayoub EJet al. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic inequities in the prescription of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with venous thromboembolism in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2019;12:e005600. 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Morris AA, Testani JM, Butler J.. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in heart failure: racial differences and a potential for reducing disparities. Circulation 2021;143:2329–31. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Eberly LA, Yang L, Eneanya NDet al. Association of race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor use among patients with diabetes in the US. JAMA Network Open 2021;4:e216139. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KWet al. CANVAS program collaborative group. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017;377:644–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SEet al. DAPA-HF trial committees and investigators. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1995–2008. 10.1056/NEJMoa1911303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter Ret al. DAPA-CKD trial committees and investigators. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1436–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. CSDH . Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/equity-and-health/commission-on-social-determinants-of-health (21 June 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 84. Moosa MR, Norris KC.. Sustainable social development: tackling poverty to achieve kidney health equity. Nat Rev Nephrol 2021;17:3–4. 10.1038/s41581-020-00342-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . CMS Outlines Strategy to Advance Health Equity, Challenges Industry Leaders to Address Systemic Inequities. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-outlines-strategy-advance-health-equity-challenges-industry-leaders-address-systemic-inequities (21 June 2022, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bryan AF, Duggan CE, Tsai TC. “Advancing Health Equity Through Federal Payment and Delivery System Reforms,” To the Point (blog), Commonwealth Fund, June 15, 2022. 10.26099/emga-aj89 (21 June 2022, date last accessed). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Luo J, Feldman R, Rothenberger SDet al. Coverage, formulary restrictions, and out-of-pocket costs for sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in the Medicare Part D program. JAMA Network Open 2020;3:e2020969. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Betts KA, Song J, Faust Eet al. Medical costs for managing chronic kidney disease and related complications in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. Am J Manag Care 2021;27:S369–74. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34878754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Willis M, Nilsson A, Kellerborg Ket al. Cost-Effectiveness of canagliflozin added to standard of care for treating diabetic kidney disease (DKD) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in England: estimates using the CREDEM-DKD model. Diabetes Ther 2021;12:313–28. 10.1007/s13300-020-00968-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. McEwan P, Morgan AR, Boyce Ret al. Cardiorenal disease in the United States: future health care burden and potential impact of novel therapies. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2022;28:415–24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35016548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Hong D, Si L, Jiang Met al. Cost effectiveness of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics 2019;37:777–818. 10.1007/s40273-019-00833-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Tummalapalli SL, Mendu ML.. Value-based care and kidney disease: emergence and future opportunities. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2022;29:30–39. 10.1053/j.ackd.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Tuttle K, Wong L, St Peter Wet al. Moving from evidence to implementation of breakthrough therapies for diabetic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2022;17:1092–103. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02980322. 10.2215/CJN.02980322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K.. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 2002;288:1775–9. 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Epping-Jordan JE, Pruitt SD, Bengoa Ret al. Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care 2004;13:299–305. 10.1136/qshc.2004.010744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . About Learning Health Systems 2019. https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/about.html (11 June 2022, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Narva A. Population health for CKD and diabetes: lessons from the Indian Health Service. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;71:407–11. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Bullock A, Burrows NR, Narva ASet al. Vital signs: decrease in incidence of diabetes-related end-stage renal disease among American Indians/Alaska Natives - United States, 1996-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:26–32. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6601e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.