Abstract

PCR assays with primers targeted to the genes encoding 16S rRNA were developed for detection of dairy propionibacteria. Propionibacterium thoenii specific oligonucleotide PT3 was selected after partial resequencing. Tests allowed the detection of less than 10 cells per reaction from milk and cheese and 102 cells per reaction from forage and soil.

Dairy or “classical” propionibacteria have great technological importance for Swiss-type cheeses, where they are responsible for “holes” and flavor formation. Strains belonging to the four Propionibacterium species P. freudenreichii, P. jensenii, P. acidipropionici, and P. thoenii, are frequently present in raw milk, in numbers varying between 10 and 104 CFU/ml (20), as a consequence of environmental contamination. A prevalence of the species P. freudenreichii and P. jensenii has been observed in milk and derived products after isolation in plates (1, 14, 15, 18, 19). Propionibacteria can also cause defects in cheeses, mainly anomalous blowing (2, 11), and pigmented P. thoenii and P. jensenii strains cause the “brown spot” of cheese paste (7). To reduce economic losses in dairy productions, the propionibacterium content of raw milk should be better controlled, limiting their diffusion in the dairy environment. Few reports exist regarding the isolation of propionibacteria from substrates like feed or soil coming into contact with raw milk (5, 17, 21). An explanation could be the major inhibiting effects exerted in plates by the typical microflora of such substrates towards propionibacteria. Growth media currently used for propionibacterium isolation are not sufficiently selective, and moreover, typical propionibacterium colonies appear after at least 6 days (20). PCR-based specific assays are a valuable alternative to plating methods, being far more rapid, more specific, and unhindered by the presence of non-target microorganisms. Dasen et al. (6) have developed a multiplex PCR assay using a genus-specific primer, targeted to the genes encoding the 16S rRNA, together with two universal primers (6). Specific DNA fragments, differing slightly in size, were amplified from both dairy and cutaneous species of Propionibacterium. The present study regards the selection of a different primer set for each dairy species and PCR detection of propionibacteria from various substrates without previous isolation.

The following type (T) and reference strains plus propionibacterium isolates were used in all the specificity tests: P. freudenreichii subsp. freudenreichii NCFB 564T, P. freudenreichii subsp. shermanii NCFB 853T, 35 P. freudenreichii isolates (19), P. jensenii NCFB 572, NCFB 565, NCFB 571, 15 P. jensenii isolates (19), P. acidipropionici NCFB 563T, NCFB 570, four P. acidipropionici isolates (19), P. thoenii NCFB 568T, NCFB 569, two P. thoenii isolates (19), Propionibacterium acnes LMG 16711T, Bifidobacterium animalis LMG 10508T, Bifidobacterium longum LMG 13197T, Enterococcus faecalis LMG 7937T, Enterococcus faecium LMG 11423T, Escherichia coli LMG 2092T, Lactobacillus brevis LMG 7944T, Lactobacillus zeae ATCC 393, Lactobacillus coryneformis DSM 20001T, Lactobacillus curvatus LMG 12006, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus LMG 6901T, Lactobacillus fructivorans LMG 9201T, Lactobacillus gasseri NCFB 2233T, Lactobacillus helveticus ATCC 10797T, Lactobacillus hilgardii LMG 6895T, Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 14917T, Lactobacillus pontis ATCC 14187T, Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 20016T, Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis LMG 6890T, Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. dextranicum LMG 6908T, Kocuria varians 55, Pediococcus acidilactici LMG 11384T, and Streptococcus thermophilus LMG 6896T.

Dairy propionibacteria were cultured in sodium lactate (SL) broth (9) in jars for anaerobiosis using the Anaerocult A system (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 30°C for 48 to 72 h. Lactic acid bacteria were grown at 30 or 37°C in anaerobiosis in MRS broth (Oxoid, Basingtoke, United Kingdom) for 24 to 72 h. The other bacteria were grown at 37°C for 24 to 72 h in brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid); P. acnes and bifidobacteria were incubated by anaerobiosis. Propionibacterium counts in samples were carried out on SL agar.

Genomic DNA was purified from 1 ml of bacterial culture in late exponential growth phase as previously described (19).

Samples of milk, cheese, forage, and soil used to determine the detection limits had been checked by plate count for absence of dairy propionibacteria and stored frozen until use. Each solid material was homogenized in 1:1 (wt/vol) sterile 1/4-strength Ringer solution. Aliquots of suspensions were artificially inoculated with propionibacterium pure cultures in numbers ranging between 108 and 1 cell/ml.

Prior to nucleic acid extraction, inoculated cheese, soil, and forage suspensions of 1:1 (wt/vol) in 1/4 strength sterile Ringer solution (Oxoid) were filtered under vacuum through 17- to 25-μm-pore-size filter paper (Forlab Carlo Erba, Milan, Italy). One milliliter of filtered suspension or milk was centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 10 min. For forage and soil samples of unknown Propionibacterium content, 50 ml of suspension was centrifuged as described above. The pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of lysis solution (0.1 M NaOH and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate). After chloroform extraction, nucleic acids were precipitated with 2 volumes of absolute ethanol and washed once with 70% ethanol. In the nucleic acid extraction from forage and soil, 10% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was added to the 70% ethanol in the final washing step (22). Nucleic acids were finally vacuum dried and dissolved in 20 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer.

Oligonucleotides reported in Table 1 were designed by comparison of the 16S rDNA sequences available in the EMBL database for dairy and non-dairy propionibacteria (P. acidipropionici X53221, P. freudenreichii X53217, P. jensenii X53219, P. thoenii X53220, P. acnes X53218, Propionibacterium cyclohexanicum D82046, Propionibacterium propionicus X53216) (3, 4), some taxonomically related species (Mycobacterium komossense X55591, Eubacterium combesii L34614, Corynebacterium xerosis X84446, Arthrobacter globiformis X80739, Micrococcus luteus M38242, Actinomyces israelii X53228, Brevibacterium linens X76566) and microorganisms commonly found in milk and dairy products (L. helveticus X61141, L. delbrueckii X52654, L. casei M23928, L. brevis X61134, S. thermophilus X68418). Sequence alignment was carried out with the ClustalX software (EMBL, Heidelberg, Germany).

TABLE 1.

Alignment of the 16S rDNA regions corresponding to E. coli nucleotide positions 435 to 478 for dairy propionibacteria

| Species | Sequenceb |

|---|---|

| P. freudenreichii | CTTTCATCCATGACGAAGCG--------------------CAAGT |

| PF | |

| P. acidipropionici | CTTTCACCAGGGACGAAGGCATT---------CTTTTAGGGTGTT |

| PA | |

| P. jensenii | CTTTCNCCAGGGACGAAGTG------------CCTNTCGGGGTGT |

| PJ | |

| P. thoenii | CTTTCACCAGGGACGAAGGG------------CCTATCGGGGTAT |

| PT1 | |

| P. thoeniia | CTTTCACCAGGGACAAAAGG------------CCTTTCGGGGTTT |

| PT3 |

New sequence determined for P. thoenii NCFB 568T.

Species-specific primers selected are underlined.

The amplification programs of genus-specific, species-specific, and seminested PCR (10) consisted of denaturation at 94°C for 4 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing for 15 s at temperatures varying with the upstream primer used, and extension at 72°C for 1 min followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The 20-μl reaction mixture contained 100 μM each dNTP, 0.5 μM each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2 μl of 10× reaction buffer, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), and 1 μl of DNA sample. Seminested or double-step PCR was applied to the 1:10 dilutions of the specific PCR mixtures. PCR products were electrophoresed at 100 V on 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel stained with 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide in 0.5× TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0])/ml.

A PCR product amplified from the 16S rDNA of P. thoenii NCFB 568T (DSM 20276T) was partially sequenced by the ABI Prism Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing System (Perkin-Elmer Co., Norwalk, Conn.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Six combinations of genus-specific oligonucleotides selected by 16S rDNA sequence comparison were tested in amplification experiments using purified DNA from all the type and reference strains reported above. Primer pair PB1-PB2 (Table 2) proved specific for dairy propionibacteria and P. acnes, providing only one product of the expected size (610 bp). Amplification reactions were carried out with annealing temperatures and time that did not affect product yield. The number of cycles was set to 40, as this determined an increase in product yield from diluted DNA of propionibacteria without appearance of additional PCR products.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in PCR identification-detection assays for dairy propionibacteria

| Label | Sequence | Corresponding E. coli positions | Target species | Annealing temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB1 | 5′-AGTGGCGAAGGCGGTTCTCTGGA-3′ | 720–742 | Dairy propionibacteria and P. acnes | 70 |

| PB2 | 5′-TGGGGTCGAGTTGCAGACCCCAAT-3′ | 1305–1328 | Dairy propionibacteria and P. acnes | 70 |

| PF | 5′-CTTTCATCCATGACGAAGCGCAAG-3′ | 435–478 | P. freudenreichii | 69 |

| PJ | 5′-GACGAAGTGCCTATCGGGGTG-3′ | 446–478 | P. jensenii | 68 |

| PA | 5′-GACGAAGGCATTCTTTTAGGGTGT-3′ | 445–478 | P. acidipropionici | 68 |

| PT2 | 5′-ATATGAGCTCCTGCTGCATNGGT-3′ | 187–210 | P. thoenii, P. acnes | 69 |

| PT3 | 5′-GGACAAAAGGCCTTTCGGGGTTT-3′ | 445–478 | P. thoenii | 70 |

Upstream primers for species-specific amplification (Tables 1 and 2) were selected within a region showing the highest variability among the species (E. coli positions 435 to 478). Using primer PB2 as the downstream oligonucleotide, amplification products of sizes 868, 867, 865, and 864 bp were expected from P. acidipropionici, P. freudenreichii, P. thoenii, and P. jensenii, respectively. Excellent specificity was obtained for P. freudenreichii, P. jensenii and P. acidipropionici. Primer PT1 (Table 1), selected for P. thoenii in the same variable region, did not allow amplification from the four P. thoenii strains tested while it permitted the amplification of a fragment of the expected size from the three reference strains of P. jensenii. Oligonucleotide PT2 (Table 2), which was potentially specific for P. thoenii, permitted the amplification of a 1,148-bp DNA fragment from P. thoenii strains and from P. acnes with equal efficiency, proving not selective.

A primer specific for P. thoenii, PT3 (Tables 1 and 2), could be designed by partially sequencing the PT2-PB2 fragment amplified from strain NCFB 568T (EMBL accession no. AJ132324).

The ability of all primer sets to amplify DNA from other strains belonging to the target species was confirmed without exception in amplifications from previously identified isolates (19).

Primer pairs PB1-PB2, PF-PB2, PJ-PB2, PA-PB2, and PT3-PB2 were used in detection assays from samples of milk, cheese, forage, and soil artificially inoculated with known numbers of propionibacteria. The short procedure described above for nucleic acid purification directly from samples provided better sensitivity compared with the DNA extraction method from pure cultures (19) and other reported procedures (8, 12).

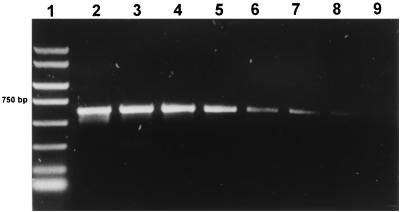

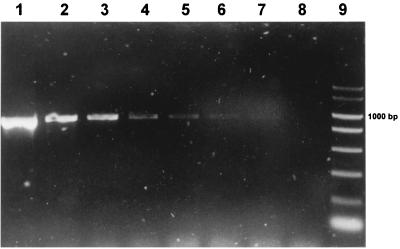

The detection limit was similar for all the specific primer sets and varied with the kind of sample. In milk and cheese, multiples of 10 cells in the PCR were detected after one amplification step. Figures 1 and 2 show examples of amplification with genus-specific primer set PB1-PB2 and with primer set PF-PB2, respectively. A seminested PCR with primers PB1-PB2 from milk and cheese permitted the detection of less than 10 cells of dairy propionibacteria in the reaction mixture. The signal was never obtained from uninoculated aliquots of the same samples used as negative controls.

FIG. 1.

Genus-specific amplification with primer set PB1-PB2 from raw milk inoculated with propionibacteria. Lanes: 1, PCR marker (Amresco, Solon, Ohio); 2, amplification from 20 ng of DNA of P. jensenii NCFB 571; 3 to 9, amplifications from initial cell numbers of 106, 105, 104, 103, 102, 10, and 1.2, respectively, of P. jensenii 2S per reaction.

FIG. 2.

Species-specific amplification with oligonucleotides PF-PB2 from serial dilutions of P. freudenreichii C21 in cheese suspension. Lanes: 1, amplification from 20 ng of DNA of P. freudenreichii subsp. freudenreichii NCFB 564T; 2 to 8, amplifications from initial cell numbers of 106, 105, 104, 103, 102, 27, and 2.6, respectively, in the PCR mixture; 9, PCR marker (Amresco).

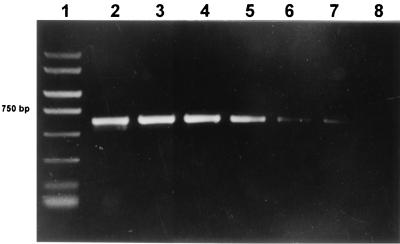

One-step amplification from forage and soil was considerably less sensitive; cell numbers lower than 105 could not be detected and addition of 10% PVP to the 70% ethanol in the final washing step was necessary to allow amplification. The addition of 400 ng of nonacetylated bovine serum albumin/ml in the PCR mixture (12) was also performed, but amplification products were not obtained. In case of PVP addition, the seminested PCR assay permitted the amplification of the 610-bp genus-specific fragment from reactions containing multiples of 102 propionibacterium cells. Figure 3 shows an example of seminested amplification on species-specific products from soil suspensions inoculated with P. acidipropionici NCFB 563T.

FIG. 3.

Seminested PCR with primers PB1-PB2 after species-specific amplification from strain P. acidipropionici NCFB 563T inoculated in soil suspension. Lanes: 1, PCR marker (Amresco, Solon, Ohio); 2, seminested amplification from 15 ng of DNA of the same strain; 3 to 8, seminested amplification from 106, 105, 104, 103, 102, and 23 cells, respectively.

The PCR assays were applied to the detection of propionibacteria from six raw milk and 14 forage samples not previously analyzed for their presence. Three samples of milk and two samples of forage were positive after single-step PB1-PB2 amplification. One more forage sample was positive after two-step amplification with the same primers. The single species could be detected by the seminested assay after species-specific PCR; in one milk sample and in two forage samples, positive to one-step PB1-PB2 amplification, none of the dairy species was present. This can be explained with amplification from P. acnes or other nondairy propionibacteria. In one PB1-PB2 PCR-positive milk sample, the presence of all four dairy species was demonstrated with the seminested assay. One more milk sample was positive for P. freudenreichii, P. jensenii, and P. acidipropionici; one more forage sample was positive for P. jensenii and P. acidipropionici.

This study has provided rapid PCR identification-detection assays for P. acnes and each dairy species of the genus Propionibacterium. Single-species detection can facilitate studies regarding the diffusion and ability to survive in different environments.

The possibility to selectively detect P. acnes with primers PT2-PB2 could allow its distinction from the other cutaneous propionibacteria, and, therefore, it should be further investigated.

Sequence comparison shows three different nucleotide positions between oligonucleotide PF and the homologous region reported for the recently proposed species Propionibacterium cyclohexanicum (13). The discriminating power of the P. freudenreichii-specific assay towards this closely related species must be experimentally evaluated.

The species-specific assays evaluated here can substitute time-consuming phenotypic identification for these slowly growing microorganisms. The preliminary individuation of samples to be further analyzed is an advantage for both practical and research applications, considering the rapidity of the whole procedure of nucleic acid extraction and amplification. The possibility to individuate milk samples containing more than 10 cells of dairy propionibacteria is useful for the choice of raw milk suitable for particular dairy productions where even initial numbers as low as 102 cells/ml are undesired (16).

For forage and soil, the sensitivity of one-step amplification is rather low and must be improved by seminested or double-step amplification. The problem can also be overcome by concentrating cells by centrifugation from larger volumes of sample suspension.

The application of PCR tests here described can give more precise indications on the seasonal variation of propionibacteria in milk and in the dairy environment.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant of the Italian Ministry of the University and Technological and Scientific Research (MURST ex 40%).

REFERENCES

- 1.Britz T J, Riedel K-H J. Propionibacterium species diversity in Leerdammer cheese. Int J Food Microbiol. 1994;22:257–267. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carcano M, Todesco R, Lodi R, Brasca M. Propionibacteria in Italian hard cheeses. Lait. 1995;75:415–425. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charfreitag O, Collins M D, Stackenbrandt E. Reclassification of Arachnia propionica as Propionibacterium propionicus comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:354–357. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charfreitag O, Stackenbrandt E. Inter- and intrageneric relationship of the genus Propionibacterium as determined by 16S rRNA sequences. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:2065–2070. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-7-2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummins C S, Johnson J L. Genus Propionibacterium. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharpe M E, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: The Williams and Wilkins Co.; 1986. pp. 1346–1353. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dasen G, Smutny J, Teuber M, Meile L. Classification and identification of propionibacteria based on ribosomal RNA genes and PCR. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:251–259. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(98)80030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Carvalho A F, Guezenec S, Gautier M, Grimont P A D. Reclassification of “Propionibacterium rubrum” as P. jensenii. Res Microbiol. 1995;146:51–58. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)80270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drake M, Small C L, Spence K D, Swanson B G. Rapid detection and identification of Lactobacillus spp. in dairy products by using the polymerase chain reaction. J Food Prot. 1996;59:1031–1036. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.10.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drinan F D, Cogan T M. Detection of propionibacteria in cheese. J Dairy Res. 1992;59:1–5. doi: 10.1017/s0022029900030259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herman L M F, De Blick J H G E, Moermans R J B. Direct detection of Listeria monocytogenes in 25 milliliters of raw milk by a two-step PCR with nested primers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:817–818. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.817-819.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hettinga D H, Reinbold G W. Split defects of Swiss cheese. II. Effects of low temperatures on metabolic activities of Propionibacterium. J Milk Food Technol. 1975;38:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreader C A. Relief of amplification inhibition in PCR with bovine serum albumin or T4 gene 32 protein. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1102–1106. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1102-1106.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kusano K, Yamada H, Niwa M, Yamasato K. Propionibacterium cyclohexanicum sp. nov., a new acid-tolerant ω-cyclohexyl fatty acid-containing Propionibacterium isolated from spoiled orange juice. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:825–831. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malik A C, Reinbold G W, Vedamuthu E R. An evaluation of the taxonomy of Propionibacterium. Can J Microbiol. 1968;14:1185–1191. doi: 10.1139/m68-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merilaeinen V, Antila M. The propionic acid bacteria in Finnish Emmental cheese. Meijerit Aikakaus. 1976;34:107–116. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pauchard J P. La fermentation secondaire dans le Gruyère. Annual report. Liebefeld-Bern, Switzerland: Federal Dairy Research Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riedel K H J, Wingfield B D, Britz T J. Identification of classical Propionibacterium species using 16S rDNA restriction fragment length polymorphism. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1998;21:419–428. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(98)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi F, Sammartino M, Torriani S. 16S-23S Ribosomal spacer polymorphism in dairy propionibacteria. Biotechnol Tech. 1997;11:159–161. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi F, Torriani S, Dellaglio F. Identification and clustering of dairy propionibacteria by RAPD-PCR and CGE-REA methods. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;85:956–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1998.tb05259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thierry A, Madec M N. Enumeration of propionibacteria in raw milk using a new selective medium. Lait. 1995;75:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaughn R H. Lactic acid fermentation of cabbage, cucumbers, olives and other products. In: Reed G, editor. Prescott and Dunn’s industrial microbiology. Saybrook, Conn: Saybrook Press; 1981. pp. 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young C C, Burghoff R L, Keim L G, Minak-Bernero V, Lute J R, Hinton S M. Polyvinylpyrrolidone-agarose gel electrophoresis purification of polymerase chain reaction-amplifiable DNA from soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1972–1974. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.6.1972-1974.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]