Abstract

5-HT7 receptor antagonism has been shown to ameliorate ketamine-induced schizophrenia-like deficits in extradimensional set-shifting using the attentional set-shifting task (ASST). However, this rodent paradigm distinguishes between several types of cognitive rigidity associated with neuropsychiatric conditions. The goal of this study was to test 5-HT7 receptor involvement in the reversal learning component of the ASST because this ability depends primarily on the orbito-frontal cortex, which shows strong 5-HT7 receptor expression. We found that impaired performance on the ASST induced by NMDA receptor blockade (MK-801, 0.2 mg/kg) in 14 rats was reversed by coadministration of the 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB-269970.The strongest effect was found on the reversal phases of ASST, whereas injection of SB-269970 alone had no effect. These results indicate that 5-HT7 receptor mechanisms may have a specific contribution to the complex cognitive deficits, increasing perseverative responding, in psychiatric diseases, including schizophrenia, depression, and anorexia nervosa, which express different forms of cognitive inflexibility.

Keywords: Serotonin 7 receptor, cognitive deficit, prefrontal cortex, NMDA blockade, schizophrenia, SB-269970

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The serotonin 7 (5-HT7) receptor is implicated in the pathogenesis and treatment of psychiatric diseases, including schizophrenia, depression, and sleep disorders. Several antipsychotics1 (most prominently lurasidone2 and amisulpride3) and antidepressants (e.g., vortioxetine4) include 5-HT7 in their rich receptor-binding profile. Clozapine, for example, has a higher affinity to 5-HT7 receptors than to D2 receptors.5 Cortical 5-HT7 receptor abnormalities were reported in human subjects with schizophrenia,6,7 and the roles of 5-HT7 mechanisms were shown in rodent models of schizophrenia.3,8–10 The latter included not only the antipsychotic-like efficacy of the selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB-269970, attenuating amphetamine and ketamine-induced hyperactivity11 and reversing prepulse inhibition deficits,12 but also its procognitive effect in acute3,13,14 and subchronic models.9,10,15 Even though data regarding the antidepressant- or antipsychotic-like effects of these compounds remain mixed (see, e.g., ref 16), there is growing research interest in studying the therapeutic potential of 5-HT7 receptor mechanisms to manage cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia and depression.

Preclinical evidence indicates that second generation antipsychotics may potentially reduce cognitive impairments according to their unique receptor-binding profiles, including the 5-HT7 receptor. Although not selective for 5-HT7 receptors, drugs with high 5-HT7 receptor affinity were tested in clinical trials and in a range of cognitive studies in rodents, including novel object recognition, spatial memory, executive function, and cognitive flexibility, pursuing lurasidone2,13,14,17,18 and amisulpride3,19,20 in schizophrenia and vortioxetine21–24 in depression. Observations indicative of these drugs’ procognitive potential keep accumulating. Importantly, it was found that their effects, on the one hand, were reversed with coadministration of the 5-HT7 receptor agonist AS1913,25,26 and, on the other hand, could be replicated by the selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB-269970.3,26

Cognitive deficits extend to a wide range of cognitive functions, including executive functions, which is one of the cognitive domains least responsive to antipsychotic drugs.10,27 Cognitive flexibility, an important component of executive functioning, has different forms impaired in schizophrenia. Amelioration of schizophrenia-relevant deficits of cognitive flexibility was tested using different rodent models. The effect of the 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB-269970 specific to reversal learning was reported in the subchronic9,10 and that of attentional set-shifting deficits in the acute3 N-methyl-d-aspartatic acid (NMDA) receptor hypofunction model. However, the two models, i.e., acute and subchronic, were tested using different behavioral paradigms. Whereas reversal learning was tested in an operant task after subchronic administration of phencyclidine (daily injections for several days), in both rats and mice, set-shifting was studied using the attentional set-shifting task (ASST) after acute administration of ketamine in rats. Although ASST allows for the identification of several types of cognitive rigidity, reversal learning did not appear to be sensitive to ketamine,3 thus hindering the examination of 5-HT7 receptor action. To resolve this apparent discrepancy, in this study, we tested the potential effect of 5-HT7 receptor blockade in ASST using the longer lasting noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801, which was shown previously to disrupt reversal learning in different spatial and nonspatial tasks under reversal conditions.28–32

The commonly used rodent ASST allows for the identification of several types of cognitive rigidity, which involve different prefrontal cortex (PFC) networks and may be affected by different receptor systems. Set-shifting and reversal learning were shown in the ASST to primarily depend on medial PFC and orbitofrontal cortex networks, respectively.33–37 Since 5-HT7 receptors show stronger orbitofrontal expression compared with medial PFC,38 we hypothesized that the 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB-269970 may avert or diminish the deficit in reversal learning induced by MK-801.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

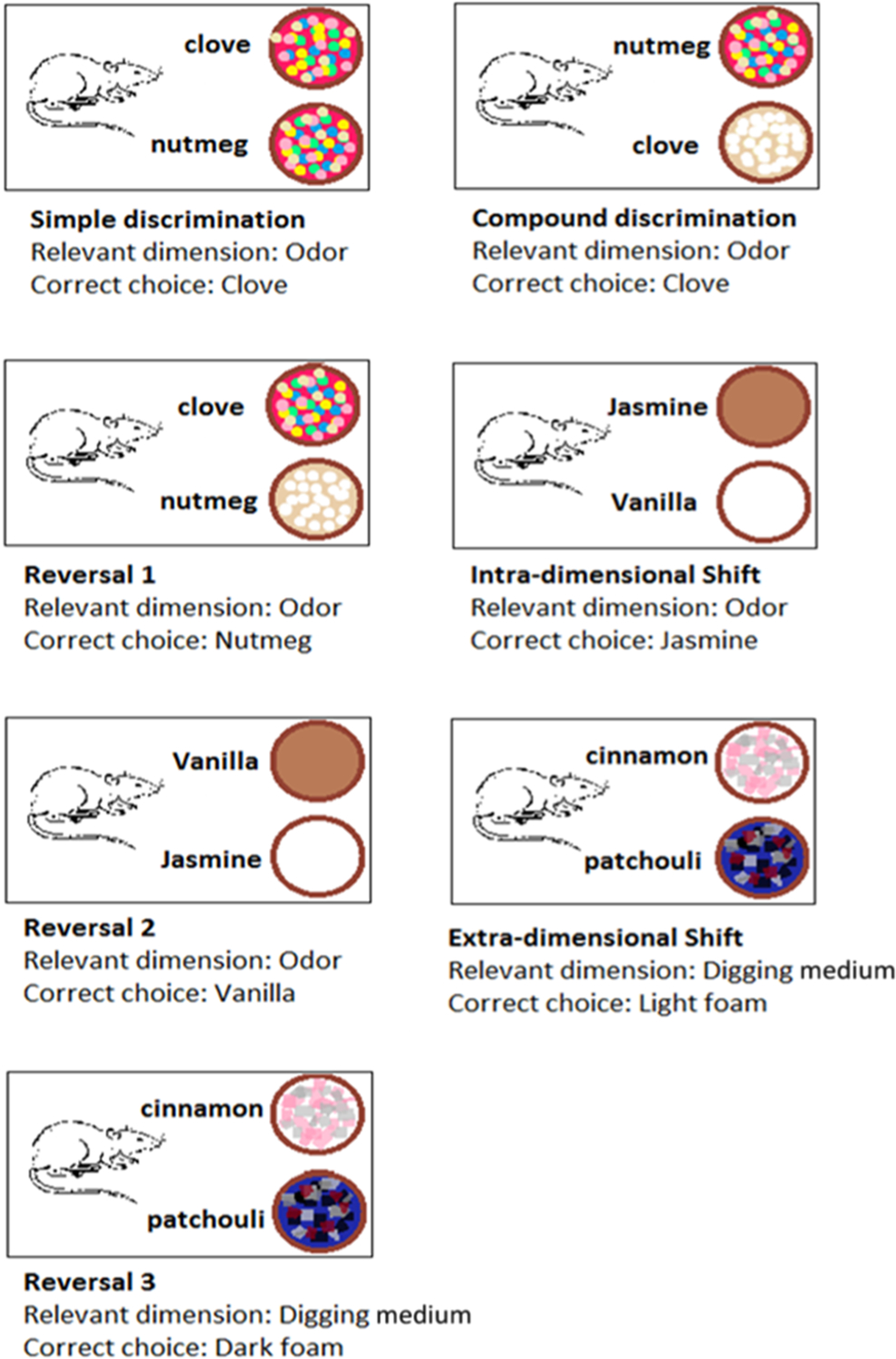

Reversal learning was tested with the widely used and standardized ASST developed by Birrell and Brown.37 In this paradigm, the rat has to go through a series of seven phases in which it has to find food in one of two pots. The pots are scented with different odors and are filled with different digging materials, under which the food is hidden. The seven phases, delivered in a sequence, one after the other, differ in terms of which odor or digging medium is set as the cue signaling the baited pot. At each stage, the rat has to learn which cue to use to find the food, and once the learning is complete (six consecutive correct trials), the task changes and the rat has to change strategy accordingly. After the initial stages of a simple (SD) and a compound discrimination (CD), in which the two dimensions are introduced, the rat’s effort is measured to make the right choice when clues change: first within the same dimension (ID) and next by switching between dimensions (ED). Each of these tests are followed by reversals (Rev1, −2, and −3 after CD, ID, and ED, respectively), in which the same clues and dimensions are used as in the previous trial, except that the +/− reward assignment is switched.

The rats were divided into two groups and tested according to one of two experimental designs. Rats in Group 1 (n = 8) were tested on ASST on three occasions (1 control and 2 drug injections), whereas Group 2 rats (n = 6) were tested six times after multiple injections (see below). This design was based on two considerations. First, control testing was necessarily performed first in all rats to generate reliable control baseline. As testing proceeded, however, the rats may have learned and improved on the task. To compensate for a potential shift in baseline performance, the test results of the control ASST (after saline injection) at the beginning of the experimental series was used in group 1, whereas in Group 2 the results of the control ASST was repeated at the end of the experiment and were used for statistical analysis. Second, as shown in prior studies,39,40 injection of MK-801 elicited continuous waking, hyperactivity, and stereotypic movements which lasted for 4–5 h. Due to behavioral impairments induced by MK-801, the rats did not take food for the first ~2 h after injection, even if food was scattered in the recording arena. Therefore, ASST started only when the rats were able to find the food, hold it, and eat it. This design was comparable to a previous study in which the ASST started 45 min after the shorter acting ketamine injection.3 Instead of ketamine, we used the more selective NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801, which has a longer effect and is thus more suitable for behavioral paradigms lasting for several hours. Acute abnormal network activity induced by MK-801 (enhanced gamma activity) was shown to last 4–5 h,39,40 i.e., covering the time of the ASST starting approximately 2 h after injection. For comparison, abnormal behavior and enhanced cortical gamma activity last less than 1 h after ketamine.

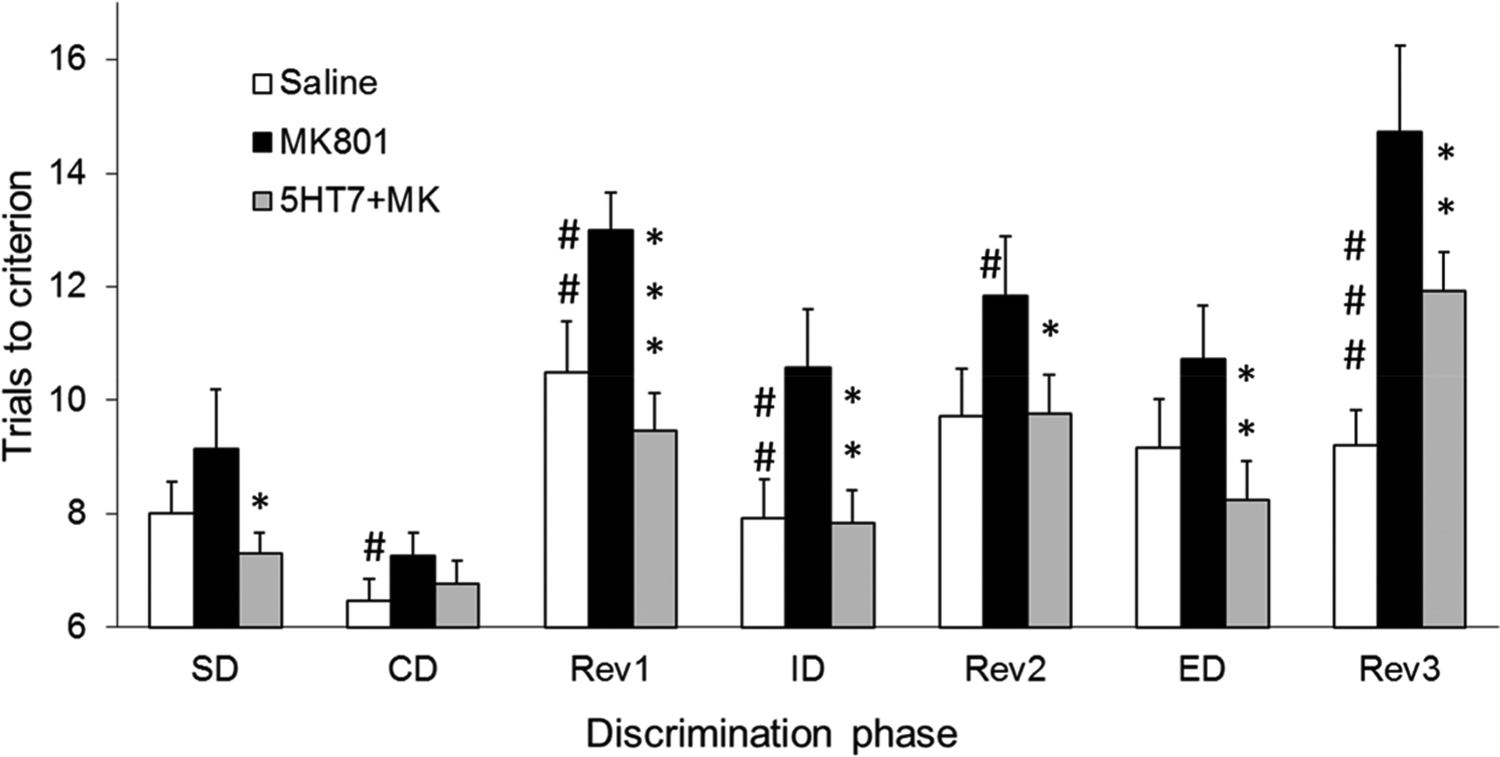

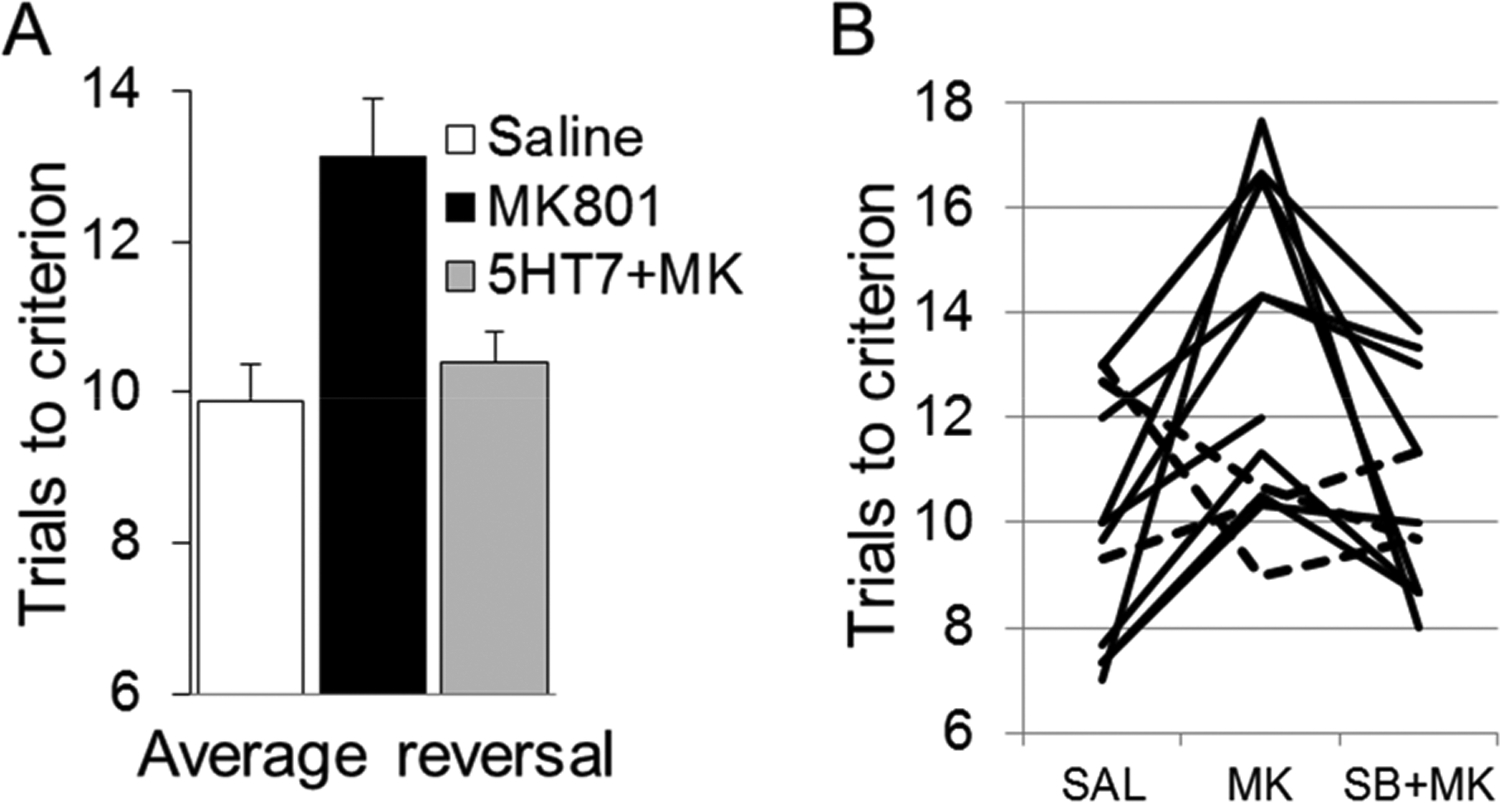

In the control ASST, the rats required more trials to learn reversals, especially Rev1 (see Methods), than for other discriminations. Additionally, the most severe impairments after NMDA receptor blockade were detected in the reversal stages. This latter effect was completely eliminated by coadministration of the 5-HT7 receptor antagonist, SB-269970 (Figure 1). Two-way ANOVA confirmed the effect of the main factors (ASST-discrimination: F(6,259) = 15.05, p = <0.0001; and drug: F(2,259) = 19.75, p = <0.0001; Groups 1 and 2 combined, n = 14) but revealed no significant interaction effect (F(12,259) = 9.51, p = 0.244). Posthoc Bonferroni comparison showed significant differences at the p = 0.05 level between control and MK-801 and between MK-801 and MK-801+SB-269970 injections but no difference between the latter and control ASST. The same results were found in two-way ANOVA after the three reversals (Rev1, −2, and −3) were combined (ASST-discrimination: F(4,259) = 20.99, p = <0.0001, drug: F(2,259) = 11.78, p = <0.0001, interaction: F(8,259) = 0.89, p = 0.529). Posthoc Bonferroni comparison also showed significant differences between MK-801 and the other two conditions. On average, trials to criterion on the reversals increased by 25% after MK-801 (13.1 ± 0.8) compared with control (9.9 ± 0.5) and MK-801+SB-269970 coadministration (10.4 ± 0.4) (Figure 2A). This pattern was consistently recorded in individual experiments (in 11 of the 14 rats; Figure 2B).

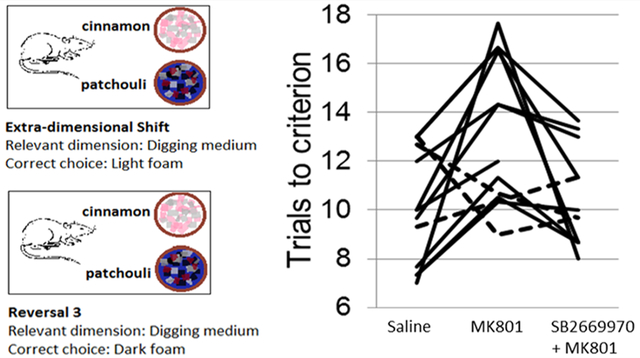

Figure 1.

Effect of the 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB-269970 on cognitive deficits induced by NMDA receptor blockade, measured using the ASST. Results represent average number of trials to reach the criterion of six consecutive correct trials, where higher means indicate more impairment (Groups 1 and 2 combined, N = 14). SB-269970 (2 mg/kg) was injected immediately before MK-801 (0.2 mg/kg) administration. ASST started about 2 h after injection when the rats could find, hold, and eat food scattered in the arena. Symbols: #p < 0.1, ##p < 0.05, ###p < 0.01 saline vs MK-801; *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 MK-801 vs SB-269970+MK-801.

Figure 2.

Amelioration of the reversal learning deficit (Rev1, −2, and −3, combined) induced by NMDA receptor blockade by SB-269970, as measured using the ASST. (A) Group averages (N = 14); (B) individual experiments (dashed lines: experiments in which the pattern differed from group). Results represent trials to reach criterion averaged over all three reversal learning phases of ASST. A higher number of trials indicates more impairment in reversal learning ability.

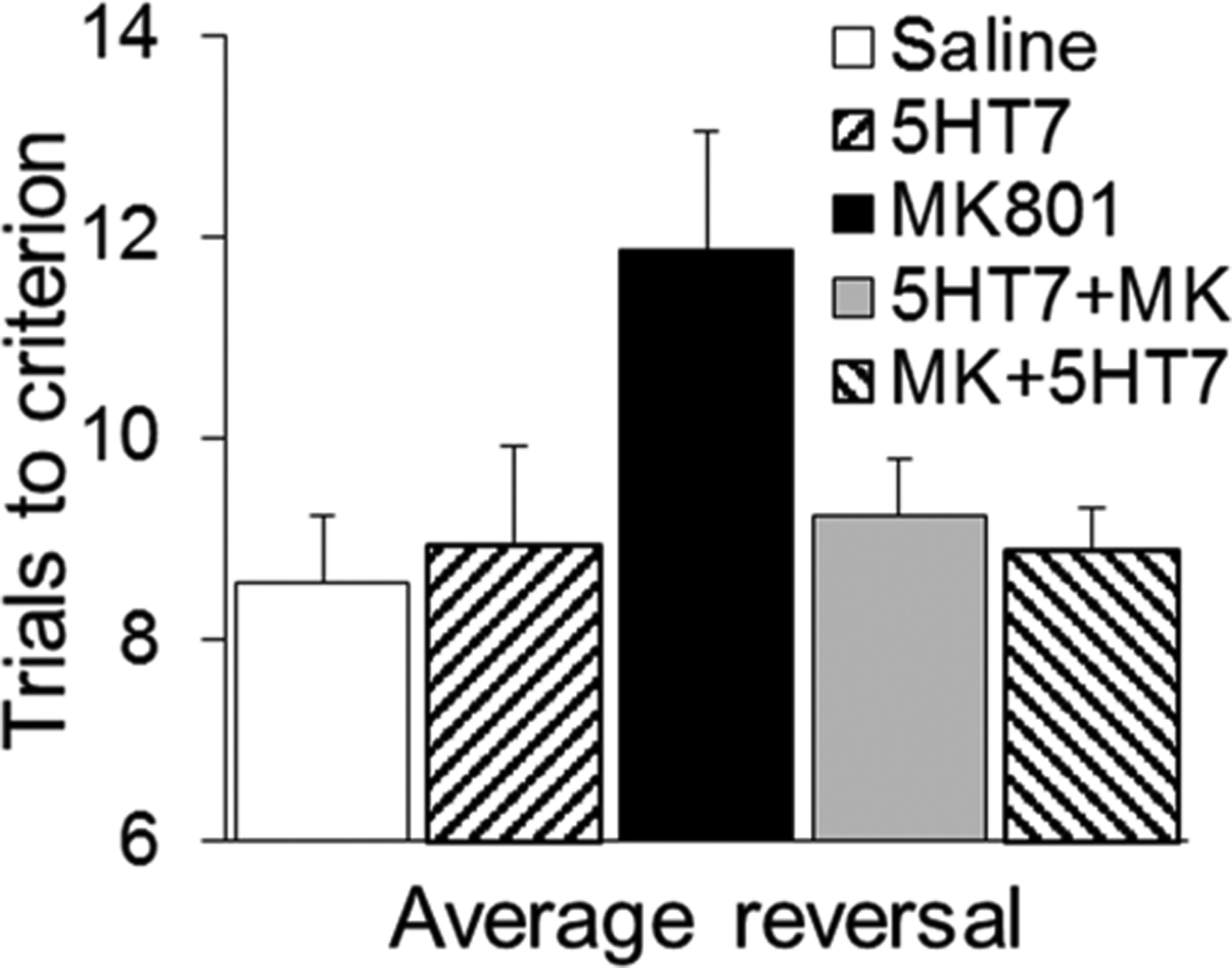

In six rats (Group 2), the protocol also included additional ASST drug trials, one testing SB-269970 alone and one in which SB-269970 was injected approximately 2 h after MK-801, i.e., immediately before starting the ASST. Two-way ANOVA showed significant differences in population means for ASST-discrimination phase (F(6,192) = 5.14, p = <0.0001) and drug injection (F(4,192) = 9.12, p = <0.0001) with no significant interaction (F(24,192) = 0.75, p = 0.79). Posthoc Bonferroni comparison revealed significant differences between performances after MK-801 injection alone vs all other conditions, but no difference between the numbers of trials to criterion in any other conditions. Reversals in this group increased after MK-801 by 38%, whereas SB-269970 alone had no effect, and its coadministration using either protocol restored performances to control levels (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reversal learning after injection of saline, SB-269970 alone (5HT7), MK-801, and a combination of the two drugs either coadministered (5HT7+MK) or injected at different time points (MK+5ht7; SB-269970 injected about 2 h after MK-801, right before the ASST). Group 2, N = 6.

Learning discrimination after an ID shift also deteriorated after MK-801 injection and the deficit was restored by SB-269970 (p < 0.05; Figure 1). For ED shift, the results showed a similar tendency, although the alterations did not reach the p = 0.05 level of significance. It should be noted, however, that the increase in average ED trials to criterion compared with ID in control ASST trials after saline injection was smaller than that in previous studies,3,37 indicating that a single ID discrimination may have been insufficient to form a strong attentional set in our sample (Figure 1). Repeated IDs, i.e., multiple presentation of the same dimension in such cases, was shown earlier to strengthen the formation of attentional set in mice,41–43 but to focus on reversal learning in this study we based our analysis of the original ASST paradigm developed for rats.37 A previous study by Nikiforuk et al.,3 which specifically focused on ID/ED performance, showed a strong, significant 5-HT7 effect on ketamine-induced impairment in this task when a strong attentional set formed in the control conditions. This was verified by a high number of ED trials relative to ID.

The present findings are in agreement with previous studies which demonstrated SB-269970 efficacy in ameliorating schizophrenia-relevant reversal learning deficits in the subchronic phencyclidine model.9,10 In this study, we showed for the first time that SB-269970 has a similar effect in the acute model of NMDA receptor blockade. SB-269970 reversed impairments of reversal learning induced by MK-801,28–32 a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist. Importantly, the effect on reversal learning was demonstrated using the traditional ASST paradigm,37 i.e., the same task in which SB-2669970 reversed ketamine-induced impairment of attentional set-shifting,3 a different form of cognitive flexibility. Impaired reversal learning has been reported in different psychiatric conditions, such as depression22 and anorexia nervosa,44,45 that are treated with compounds acting on the serotonergic system. The results indicate that 5-HT7 receptor mechanisms may have a specific contribution to the complex cognitive deficits found in a wide range of psychiatric diseases, which express different forms of cognitive inflexibility, even if direct evidence for antipsychotic-like or anxiolytic-like efficacy remains debated (cf., e.g., refs 11, 12 vs refs 16, 46).

The exact mechanisms require further investigations, which may include selective and nonselective 5-HT7 compounds and genetic studies. The interactions between NMDA and 5-HT7 receptor mechanisms are complex, organized on different levels of neural coordination. 5-HT7 antagonists may act selectively, normalizing glutamatergic transmission, and may also act on the level of neural networks. For example, SB269970 reversed working memory deficits induced by MK-801 (but not scopolamine), while it normalized MK-801-induced glutamate (but not dopamine) levels.47 On the other hand, excitatory 5-HT (2c, 3, 6, 7) receptors strongly modulate cortical network activity, including rhythmic, synchronized neuronal firing,48–53 involved in cognitive function. NMDA receptor blockade also drastically alters neural oscillations,39,40 impaired also in human schizophrenia.54,55 For compounds acting at the 5-HT7 receptor, such an effect was shown in preclinical studies56,57 and in a recent human trial, in which neural communication in theta and gamma EEG bands was affected by treatment with vortioxetine.58 This compound alleviates cognitive symptoms in animal models and in patients with depression.21–24 Yet, on another level, a key role of 5-HT7 mechanisms was recently identified in maturation of the PFC–dorsal raphe circuit, implicating 5-HT7 receptors in the detrimental emotional effects associated with SSRI exposure during early postnatal life.59

METHODS

Animals.

Fourteen male Sprague–Dawley rats were tested in the ASST. After a week of acclimatization, the rats were housed individually in separate cages. Single rat housing was required by the procedure of mild food restriction (10 g of food daily) applied for several days before the ASST. Training and testing occurred in the light phase of a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7 AM). All procedures were performed according to the NIH Guide and were approved by the BIDMC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Attentional Set-Shifting Task.

All ASST procedures closely followed those established by Birrell and Brown.37

Apparatus.

The testing arena comprised of a dark plastic box (66 × 41 × 46 cm3) in which two bowls were placed in adjacent corners. In experiments of Group 2, an additional dark wall was used to separate the two bowls. Half of the arena, holding the bowls, was covered. The lid and the dark walls were used to prevent the rats from getting distracted by the surrounding environment during testing and to reduce potential anxiety. A camera was placed above the bowls for video recording of the animals’ behavior. A plastic box (25 × 20 × 30 cm3), open to the bottom, was used to contain the rat and to separate it from the bowls in between the trials. The bowls were scented and filled with sawdust on the bottom and digging medium on top, according to Table 1. To give each bowl a specific scent, odor essence was applied to a cotton pad and put in a plastic bag together with the bowl for 24 h before the first test. The bowls were renewed with both scent and digging medium after about four ASSTs. For the pretest, conducted the day before the ASST to make sure the rat was ready for testing, almond scented black gravel versus lemon scented black gravel was used for simple discrimination and lemon scented clear glass beads versus lemon scented black gravel was used for compound discrimination. The bait was buried in the middle of the sawdust layer beneath the digging medium, only in the correct bowl. On top of both bowls, food was sprinkled in order to reduce the capability of the rat to choose the correct bowl by smelling the bait.

Table 1.

Example of the Order of Discriminations Used in the ASST of Rats in Group 1a

| phase | dimensions | exemplar combinations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| task | relevant | irrelevant | S+ | S− |

| SD | Odor | clove | nutmeg | |

| CD | odor | medium | clove + multicolor beads | nutmeg + multicolor beads |

| clove + clear beads | nutmeg + clear beads | |||

| Revl | odor | medium | nutmeg + multicolor beads | clove + multicolor beads |

| nutmeg + clear beads | clove + clear beads | |||

| ID | odor | medium | jasmine + brown paper | vanilla + brown paper |

| jasmine + white paper | vanilla + white paper | |||

| Rev2 | odor | medium | vanilla + brown paper | jasmine + brown paper |

| vanilla + white paper | jasmine + white paper | |||

| ED | medium | odor | cinnamon + light foam | cinnamon + dark foam |

| patchouli + light foam | patchouli + dark foam | |||

| Rev3 | medium | odor | cinnamon + dark foam | cinnamon + light foam |

| patchouli + dark foam | patchouli + light foam | |||

The correct pot is signified by S+ and the incorrect by S−. For each discrimination problem, the correct choice was paired with either exemplar from the irrelevant dimension. In the ID and ED phases, novel exemplars for each dimension was introduced. In Group 2, the odor and medium were switched as relevant and irrelevant dimensions (see Design).

Habituation and Training.

After habituation to the testing arena and the bowls containing the food, the rats were trained on a series of simple discriminations (SD). The aim of the training was for the rats to learn to associate a food reward with an odor or/and a digging medium. The same pair of stimuli was used for all rats during the training, and the positive and negative cues were presented randomly and equally for each rat. The stimuli used in the training were not used later in the actual test. Rats are able to learn to dig reliably in approximately 4–7 days according to the following schedule:

Days 1–2:

The arena was covered halfway by the lid with mounted camera. The rat was placed and left alone to explore the arena for about 5 min without a bowl in it. After about 5 min a bowl filled with bedding (sawdust) was placed into one corner of the arena, on the side covered with the lid. Roughly five pieces of food was placed in the center of the bowl, on top of the bedding. Only one bowl was used at this point. The goal was only to get the rat to eat the food; it was not timed. The corner, in which the bowl was placed, was randomized so that the rat would not form a side preference. Training stopped after 30 min or after the rat ate 10 pieces of food. These steps were repeated until the rat ate 10 pieces of food during one 30 min session.

Days 2–3:

After the rat completed the first phase of eating, 10 uncovered pieces of food within one 30 min session, the process of burying the food was initiated little by little. The rat was left in the arena to adjust for about 5 min. One piece of food was placed in the center of the bowl on top of the bedding with the corner randomized. Still only one bowl was used at this stage. When the rat managed to reach about four uncovered pieces, the food was gradually concealed more and more over the next trials until it was deeply buried. The goal was to get the rat to eat five uncovered pieces and five buried pieces.

Days 3–4:

The rat was left to adjust to the arena for about 5 min before training commenced. At this point, every piece of food was buried, and the corner was randomized according to the learning to dig (LTD) schedule sheet. The goal was to get the rat to eat 10 buried pieces, but still without timing.

Days 4–7:

The rat was placed in the arena for about 5 min, and after that the holding box was introduced. The rat was placed under the holding box for about 2 min while the baited bowl was placed in the randomized corner according to the LTD schedule sheet. The holding box was relatively large, almost the size of the rats’ home cage (16″ × 20″, 8.25″ H) so the animals could get used to it within the next 1 to 2 days. At this stag,e the rat had only 90 s to find and eat the food during the first four trials and only 60 s during trials five and above. This training phase was continued until the rat retrieved 10 buried pieces within the time limit in a row (consecutive). Once the rat reached the goal of finding 10 buried food pieces within the time limit in consecutive trials, it was considered ready for the exemplar phase, or the ASST pretest. The exemplar, as stated above, consisted of almond versus lemon (odor discrimination) and glass beads versus black gravel (digging medium discrimination). The exemplar phase has to be conducted the day before each ASST to make sure the rat is ready for testing. The complete ASST should not be conducted unless the rat completed the exemplar stage successfully. Exemplars follow the same rules as the ASST; six consecutive correct trials are required to pass.

ASST Testing.

The procedure was adopted by Birrell and Brown.37 Testing consisted of seven phases; details are shown in Table 1, and a schematic overview can be seen in Figure 4. The first four trials of each phase were exploratory; the rat had 90 s to complete the trial, and it could dig in the wrong bowl without ending the trial. If the rat dug in the wrong bowl first but later dug in the correct one, the trial would still be marked as a failure. During trial five and onward, the rat only had 60 s to complete and the trial would end immediately if it dug in the wrong bowl. If time ran out without the rat digging in any of the bowls, the trial would be marked as an omission. Omissions did not restart a streak of consecutive correct trials. Any noticeable displacement of digging medium with the nose or paw would be considered as digging. The rat was allowed to sniff and touch the incorrect bowls as long as no evident displacement of digging medium occurred. When six consecutive correct trials were reached, that phase of the test was complete and the rat could move on to the next one. Between each set of novel exemplars, i.e., between Rev1 and ID as well as between Rev2 and ED, the rat got a break for 5–10 min in order to maintain its interest and to let it drink water. During the break, the rat was moved back to its home cage while the new bowls were prepared.

Figure 4.

Schematic overview of the ASST procedure. Progression of discriminations from simple (SD) and compound discriminations (CD) through intra- (ID) and extradimensional (ED) shifts alternated with reversals (Rev1, −2, and −3) after different discriminations, CD, ID, and ED. The relevant dimension was odor in the first phases switched to digging material in ED and the following Rev3. The rewarded and unrewarded stimuli in the relevant dimensions were switched in reversals, compared with the immediately preceding stage.

Compounds.

MK-801 (NMDA receptor antagonist) was purchased from Tocris through R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA) and injected in a dose of 0.2 mg/kg of body weight, which was shown in prior studies to elicit schizophrenia-like symptoms in rats.39,40 SB-269970 was purchased from AbCam (Cambridge, MA, USA); the compound is a 5-HT7 receptor antagonist with a pKi of 8.3 and exhibits >50-fold selectivity against other receptors. It was injected in a dose of 2 mg/kg, i.e., in the range used in prior behavioral studies (1–3 mg/kg3,9,10). In vivo detection of 5-HT7 antagonism in rats showed that 1–30 mg/kg SB-269970 dosedependently, and almost completely, inhibited serotonin-induced hypothermia with an ED50 of 2.96 ± 0.2 mg/kg.16,60 This reaction was also shown to be missing in 5-HT7 receptor knockout mice.61

Design.

The rats were divided into two groups and tested according to one of two experimental designs. In the first group (n = 8), each rat was tested on the ASST three times under different conditions. A week after a control ASST to establish baseline with no injection, each rat was injected once with MK-801 and once with MK-801 and SB-269970 before retesting in the ASST. The order of drug injections was randomized: in four rats, MK-801 was tested before the MK+SB-269970 combination; in the four others, the order was reversed. At least 1 week was allowed between the injections. ASST after MK-801 injection started as soon as the rat could pick up, hold, and eat a piece of food, approximately 2–3 h after injection. ASST after the MK-801 and SB-269970 coadministration started with the same delay, i.e., approximately 2–3 h.

Rats in the second group (n = 6) were tested six times each, after injection of saline, MK-801, SB-269970 alone, after coadministration of MK801 and SB-269970, and after coadministration followed by a second injection of SB-269970 about 2 h later, i.e., immediately before starting the ASST. Saline injection was tested once at the beginning of the experiment and repeated at the end of the series in each rat whereas the order of the other injections was randomized. Using odor and digging medium was also randomized so either odor or medium was used as the relevant dimension during the first five stages of ASST in Group 1 and 2, respectively (Table 1).

Statistics.

ASST data were analyzed using two-way ANOVAs to assess drug effects, followed by pairwise posthoc Bonferroni comparisons using OriginPRO software. Alpha was set as p < 0.05.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH100820).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ASST

attentional set-shifting task

- SD

simple discrimination

- CD

compound discrimination

- ID

intradimensional

- ED

extradimensional

- Rev

reversal

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- 5-HT7

5-hydroxytryptamine 7

- NMDA

N-methyl- d-aspartate

- D2

dopamine 2

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00554

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Alma Hrnjadovic, Department of Psychiatry, BIDMC, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachussetts 02215, United States.

James Friedmann, Department of Psychiatry, BIDMC, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachussetts 02215, United States.

Sandra Barhebreus, Department of Psychiatry, BIDMC, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachussetts 02215, United States.

Patricia J. Allen, Department of Psychiatry, BIDMC, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachussetts 02215, United States

Bernat Kocsis, Department of Psychiatry, BIDMC, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachussetts 02215, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Meltzer HY (2017) New Trends in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. CNS Neurol. Disord.: Drug Targets 16, 900–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Okada M, Fukuyama K, and Ueda Y (2019) Lurasidone inhibits NMDA receptor antagonist-induced functional abnormality of thalamocortical glutamatergic transmission via 5-HT7 receptor blockade. Br. J. Pharmacol 176, 4002–4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Nikiforuk A, Kos T, Fijal K, Holuj M, Rafa D, and Popik P (2013) Effects of the selective 5-HT7 receptor antagonist SB-269970 and amisulpride on ketamine-induced schizophrenia-like deficits in rats. PLoS One 8, No. e66695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gonda X, Sharma SR, and Tarazi FI (2019) Vortioxetine: a novel antidepressant for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 14, 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Roth BL, Craigo SC, Choudhary MS, Uluer A, Monsma FJ Jr., Shen Y, Meltzer HY, and Sibley DR (1994) Binding of typical and atypical antipsychotic agents to 5-hydroxytryptamine-6 and 5-hydroxytryptamine-7 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 268, 1403–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).East SZ, Burnet PW, Kerwin RW, and Harrison PJ (2002) An RT-PCR study of 5-HT(6) and 5-HT(7) receptor mRNAs in the hippocampal formation and prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 57, 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Dean B, Pavey G, Thomas D, and Scarr E (2006) Cortical serotonin7, 1D and 1F receptors: effects of schizophrenia, suicide and antipsychotic drug treatment. Schizophr Res. 88, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Semenova S, Geyer MA, Sutcliffe JG, Markou A, and Hedlund PB (2008) Inactivation of the 5-HT(7) receptor partially blocks phencyclidine-induced disruption of prepulse inhibition. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).McLean SL, Woolley ML, Thomas D, and Neill JC (2009) Role of 5-HT receptor mechanisms in sub-chronic PCP-induced reversal learning deficits in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 206, 403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Rajagopal L, Massey BW, Michael E, and Meltzer HY (2016) Serotonin (5-HT)1A receptor agonism and 5-HT7 receptor antagonism ameliorate the subchronic phencyclidine-induced deficit in executive functioning in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 233, 649–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Waters KA, Stean TO, Hammond B, Virley DJ, Upton N, Kew JN, and Hussain I (2012) Effects of the selective 5-HT(7) receptor antagonist SB-269970 in animal models of psychosis and cognition. Behav. Brain Res 228, 211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Galici R, Boggs JD, Miller KL, Bonaventure P, and Atack JR (2008) Effects of SB-269970, a 5-HT7 receptor antagonist, in mouse models predictive of antipsychotic-like activity. Behav. Pharmacol 19, 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Horisawa T, Nishikawa H, Toma S, Ikeda A, Horiguchi M, Ono M, Ishiyama T, and Taiji M (2013) The role of 5-HT7 receptor antagonism in the amelioration of MK-801-induced learning and memory deficits by the novel atypical antipsychotic drug lurasidone. Behav. Brain Res 244, 66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Horisawa T, Ishibashi T, Nishikawa H, Enomoto T, Toma S, Ishiyama T, and Taiji M (2011) The effects of selective antagonists of serotonin 5-HT7 and 5-HT1A receptors on MK-801-induced impairment of learning and memory in the passive avoidance and Morris water maze tests in rats: mechanistic implications for the beneficial effects of the novel atypical antipsychotic lurasidone. Behav. Brain Res 220, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Huang M, Kwon S, Rajagopal L, He W, and Meltzer HY (2018) 5-HT1A parital agonism and 5-HT7 antagonism restore episodic memory in subchronic phencyclidine-treated mice: role of brain glutamate, dopamine, acetylcholine and GABA. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 235, 2795–2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Maxwell J, Gleason SD, Falcone J, Svensson K, Balcer OM, Li X, and Witkin JM (2019) Effects of 5-HT7 receptor antagonists on behaviors of mice that detect drugs used in the treatment of anxiety, depression, or schizophrenia. Behav. Brain Res 359, 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Enomoto T, Ishibashi T, Tokuda K, Ishiyama T, Toma S, and Ito A (2008) Lurasidone reverses MK-801-induced impairment of learning and memory in the Morris water maze and radial-arm maze tests in rats. Behav. Brain Res 186, 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Horiguchi M, Hannaway KE, Adelekun AE, Jayathilake K, and Meltzer HY (2012) Prevention of the phencyclidine-induced impairment in novel object recognition in female rats by coadministration of lurasidone or tandospirone, a 5-HT(1A) partial agonist. Neuropsychopharmacology 37, 2175–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Curran MP, and Perry CM (2001) Amisulpride: a review of its use in the management of schizophrenia. Drugs 61, 2123–2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Park JH, Hong JS, Kim SM, Min KJ, Chung US, and Han DH (2019) Effects of Amisulpride Adjunctive Therapy on Working Memory and Brain Metabolism in the Frontal Cortex of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Preliminary Positron Emission Tomography/Computerized Tomography Investigation. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci 17, 250–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Pehrson AL, Leiser SC, Gulinello M, Dale E, Li Y, Waller JA, and Sanchez C (2015) Treatment of cognitive dysfunction in major depressive disorder–a review of the preclinical evidence for efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and the multimodal-acting antidepressant vortioxetine. Eur. J. Pharmacol 753, 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Wallace A, Pehrson AL, Sanchez C, and Morilak DA (2014) Vortioxetine restores reversal learning impaired by 5-HT depletion or chronic intermittent cold stress in rats. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 17, 1695–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bennabi D, Haffen E, and Van Waes V (2019) Vortioxetine for Cognitive Enhancement in Major Depression: From Animal Models to Clinical Research. Front. Psychiatry 10, 771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Felice D, Guilloux JP, Pehrson A, Li Y, Mendez-David I, Gardier AM, Sanchez C, and David DJ (2018) Vortioxetine Improves Context Discrimination in Mice Through a Neurogenesis Independent Mechanism. Front. Pharmacol 9, 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Nikiforuk A, and Popik P (2013) Amisulpride promotes cognitive flexibility in rats: the role of 5-HT7 receptors. Behav. Brain Res 248, 136–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Horiguchi M, Huang M, and Meltzer HY (2011) The role of 5-hydroxytryptamine 7 receptors in the phencyclidine-induced novel object recognition deficit in rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 338, 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Nikiforuk A (2015) Targeting the Serotonin 5-HT7 Receptor in the Search for Treatments for CNS Disorders: Rationale and Progress to Date. CNS Drugs 29, 265–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).van der Meulen JA, Bilbija L, Joosten RN, de Bruin JP, and Feenstra MG (2003) The NMDA-receptor antagonist MK-801 selectively disrupts reversal learning in rats. NeuroReport 14, 2225–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lobellova V, Entlerova M, Svojanovska B, Hatalova H, Prokopova I, Petrasek T, Vales K, Kubik S, Fajnerova I, and Stuchlik A (2013) Two learning tasks provide evidence for disrupted behavioural flexibility in an animal model of schizophrenia-like behaviour induced by acute MK-801: a dose-response study. Behav. Brain Res 246, 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Thonnard D, Dreesen E, Callaerts-Vegh Z, and D’Hooge R (2019) NMDA receptor dependence of reversal learning and the flexible use of cognitively demanding search strategies in mice. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 90, 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Graf R, Longo JL, and Hughes ZA (2018) The location discrimination reversal task in mice is sensitive to deficits in performance caused by aging, pharmacological and other challenges. J. Psychopharmacol 32, 1027–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kumar G, Olley J, Steckler T, and Talpos J (2015) Dissociable effects of NR2A and NR2B NMDA receptor antagonism on cognitive flexibility but not pattern separation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 232, 3991–4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Bissonette GB, Powell EM, and Roesch MR (2013) Neural structures underlying set-shifting: roles of medial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex. Behav. Brain Res 250, 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).McAlonan K, and Brown VJ (2003) Orbital prefrontal cortex mediates reversal learning and not attentional set shifting in the rat. Behav. Brain Res 146, 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Ragozzino ME (2007) The contribution of the medial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and dorsomedial striatum to behavioral flexibility. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1121, 355–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Brown VJ, and Bowman EM (2002) Rodent models of prefrontal cortical function. Trends Neurosci. 25, 340–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Birrell JM, and Brown VJ (2000) Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. J. Neurosci 20, 4320–4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Canese R, Marco EM, De Pasquale F, Podo F, Laviola G, and Adriani W (2011) Differential response to specific 5-Ht(7) versus whole-serotonergic drugs in rat forebrains: a phMRI study. NeuroImage 58, 885–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Pinault D (2008) N-methyl d-aspartate receptor antagonists ketamine and MK-801 induce wake-related aberrant gamma oscillations in the rat neocortex. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 730–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kittelberger K, Hur EE, Sazegar S, Keshavan V, and Kocsis B (2012) Comparison of the effects of acute and chronic administration of ketamine on hippocampal oscillations: relevance for the NMDA receptor hypofunction model of schizophrenia. Brain Struct. Funct 217, 395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Janitzky K, Lippert MT, Engelhorn A, Tegtmeier J, Goldschmidt J, Heinze HJ, and Ohl FW (2015) Optogenetic silencing of locus coeruleus activity in mice impairs cognitive flexibility in an attentional set-shifting task. Front. Behav. Neurosci 9, 286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Bissonette GB, and Powell EM (2012) Reversal learning and attentional set-shifting in mice. Neuropharmacology 62, 1168–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Garner JP, Thogerson CM, Wurbel H, Murray JD, and Mench JA (2006) Animal neuropsychology: validation of the Intra-Dimensional Extra-Dimensional set shifting task for mice. Behav. Brain Res 173, 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Allen PJ, Jimerson DC, Kanarek RB, and Kocsis B (2017) Impaired reversal learning in an animal model of anorexia nervosa. Physiol. Behav 179, 313–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Bernardoni F, Geisler D, King JA, Javadi AH, Ritschel F, Murr J, Reiter AMF, Rossner V, Smolka MN, Kiebel S, and Ehrlich S (2018) Altered Medial Frontal Feedback Learning Signals in Anorexia Nervosa. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 235–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Balcer OM, Seager MA, Gleason SD, Li X, Rasmussen K, Maxwell JK, Nomikos G, Degroot A, and Witkin JM (2019) Evaluation of 5-HT7 receptor antagonism for the treatment of anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia through the use of receptor-deficient mice. Behav. Brain Res 360, 270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Bonaventure P, Aluisio L, Shoblock J, Boggs JD, Fraser IC, Lord B, Lovenberg TW, and Galici R (2011) Pharmacological blockade of serotonin 5-HT(7) receptor reverses working memory deficits in rats by normalizing cortical glutamate neurotransmission. PLoS One 6, No. e20210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Ly S, Pishdari B, Lok LL, Hajos M, and Kocsis B (2013) Activation of 5-HT6 receptors modulates sleep-wake activity and hippocampal theta oscillation. ACS Chem. Neurosci 4, 191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Sorman E, Wang D, Hajos M, and Kocsis B (2011) Control of hippocampal theta rhythm by serotonin: role of 5-HT2c receptors. Neuropharmacology 61, 489–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Schulz SB, Heidmann KE, Mike A, Klaft ZJ, Heinemann U, and Gerevich Z (2012) First and second generation antipsychotics influence hippocampal gamma oscillations by interactions with 5-HT3 and D3 receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol 167, 1480–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Celada P, Puig MV, and Artigas F (2013) Serotonin modulation of cortical neurons and networks. Front. Integr. Neurosci 7, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Skovgard K, Agerskov C, Kohlmeier KA, and Herrik KF (2018) The 5-HT3 receptor antagonist ondansetron potentiates the effects of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor donepezil on neuronal network oscillations in the rat dorsal hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 143, 130–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Huang Y, Yoon K, Ko H, Jiao S, Ito W, Wu JY, Yung WH, Lu B, and Morozov A (2016) 5-HT3a Receptors Modulate Hippocampal Gamma Oscillations by Regulating Synchrony of Parvalbumin-Positive Interneurons. Cereb. Cortex 26, 576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Gonzalez-Burgos G, Cho RY, and Lewis DA (2015) Alterations in cortical network oscillations and parvalbumin neurons in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 77, 1031–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Spencer KM, Niznikiewicz MA, Shenton ME, and McCarley RW (2008) Sensory-evoked gamma oscillations in chronic schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 744–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Riga MS, Sanchez C, Celada P, and Artigas F (2020) Subchronic vortioxetine (but not escitalopram) normalizes brain rhythm alterations and memory deficits induced by serotonin depletion in rats. Neuropharmacology 178, 108238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Leiser SC, Pehrson AL, Robichaud PJ, and Sanchez C (2014) Multimodal antidepressant vortioxetine increases frontal cortical oscillations unlike escitalopram and duloxetine–a quantitative EEG study in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol 171, 4255–4272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Nissen TD, Laursen B, Viardot G, l’Hostis P, Danjou P, Sluth LB, Gram M, Bastlund JF, Christensen SR, and Drewes AM (2020) Effects of Vortioxetine and Escitalopram on Electroencephalographic Recordings - A Randomized, Crossover Trial in Healthy Males. Neuroscience 424, 172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Olusakin J, Moutkine I, Dumas S, Ponimaskin E, Paizanis E, Soiza-Reilly M, and Gaspar P (2020) Implication of 5-HT7 receptor in prefrontal circuit assembly and detrimental emotional effects of SSRIs during development. Neuropsychopharmacology 45, 2267–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Hagan JJ, Price GW, Jeffrey P, Deeks NJ, Stean T, Piper D, Smith MI, Upton N, Medhurst AD, Middlemiss DN, Riley GJ, Lovell PJ, Bromidge SM, and Thomas DR (2000) Characterization of SB-269970-A, a selective 5-HT(7) receptor antagonist. Br. J. Pharmacol 130, 539–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Hedlund PB, Danielson PE, Thomas EA, Slanina K, Carson MJ, and Sutcliffe JG (2003) No hypothermic response to serotonin in 5-HT7 receptor knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 100, 1375–1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]