Abstract

SSc is a systemic autoimmune disease of unknown etiology characterized by frequently progressive cutaneous and internal organ fibrosis causing severe disability, organ failure and high mortality. A remarkable feature of SSc is the extension of the fibrotic alterations to nonaffected tissues. The mechanisms involved in the extension of fibrosis have remained elusive. We propose that this process is mediated by exosome microvesicles released from SSc-affected cells that induce an activated profibrotic phenotype in normal or nonaffected cells. Exosomes are secreted microvesicles involved in an intercellular communication system. Exosomes can transfer their macromolecular content to distant target cells and induce paracrine effects in the recipient cells, changing their molecular pathways and gene expression. Confirmation of this hypothesis may identify the molecular mechanisms responsible for extension of the SSc fibrotic process from affected cells to nonaffected cells and may allow the development of novel therapeutic approaches for the disease.

Keywords: SSc, fibrosis, exosomes, paracrine, myofibroblasts, endothelial cells, cellular phenotype

Rheumatology key messages.

Fibrosis in SSc is characterized by its extension from affected to normal tissues.

The mechanisms involved in the extension of the fibrotic process have not been elucidated.

Exosome microvesicles released from affected SSc cells may mediate extension of fibrosis through paracrine mechanisms.

Introduction

SSc is a systemic autoimmune disease of unknown etiology characterized by a frequently progressive fibrotic process that affects the skin, the microvasculature and numerous internal organs, including the lungs, heart and kidneys [1–5]. The fibrotic involvement of skin is the most common and specific manifestation of the disease and may be extensive and frequently progressive, particularly in the dcSSc clinical subset of the disease [6]. Cutaneous fibrosis in SSc often causes severe clinical alterations and disability [7–11], and the extent of skin fibrotic involvement and its rate of progression have been shown to be accurate predictors of SSc-related mortality and internal organ involvement [10]. The SSc fibrotic process can also affect multiple internal organs [1–5]. Pulmonary and cardiac involvement in SSc is frequently progressive, leading to organ failure and a high rate of mortality [12–14].

A remarkable feature of SSc is the extension of the fibrotic alterations from affected tissues to normal or nonaffected tissues resulting in the progression of cutaneous fibrosis or in the development of new fibrotic organ involvement. Although the extension of the fibrotic process is a crucial event in SSc pathogenesis and is a determinant of the clinical outcome and prognosis of the disease, the mechanisms involved have remained elusive. In a previous study we examined the effects of exosomes isolated from the serum of SSc patients on the gene expression patterns of cultured normal dermal fibroblasts and found that the SSc exosomes induced a remarkable stimulation of a profibrotic phenotype in the normal cells [15]. Based on these results, we suggested that the extension of the fibrotic process to normal cells in SSc may be mediated by exosomes released from SSc affected cells. We further suggested that these effects may involve paracrine mechanisms that induce the phenotypic conversion of normal fibroblasts into activated myofibroblasts [15]. Although we did not examine the effects of SSc serum exosomes on other cells, it is likely that a similar mechanism may also activate other target cells, such as endothelial cells and adipocytes, resulting in their conversion into activated myofibroblasts, the cells ultimately responsible for tissue fibrosis [16]. This hypothesis is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1. The most relevant published scientific evidence supporting this hypothesis will be briefly reviewed in the following sections.

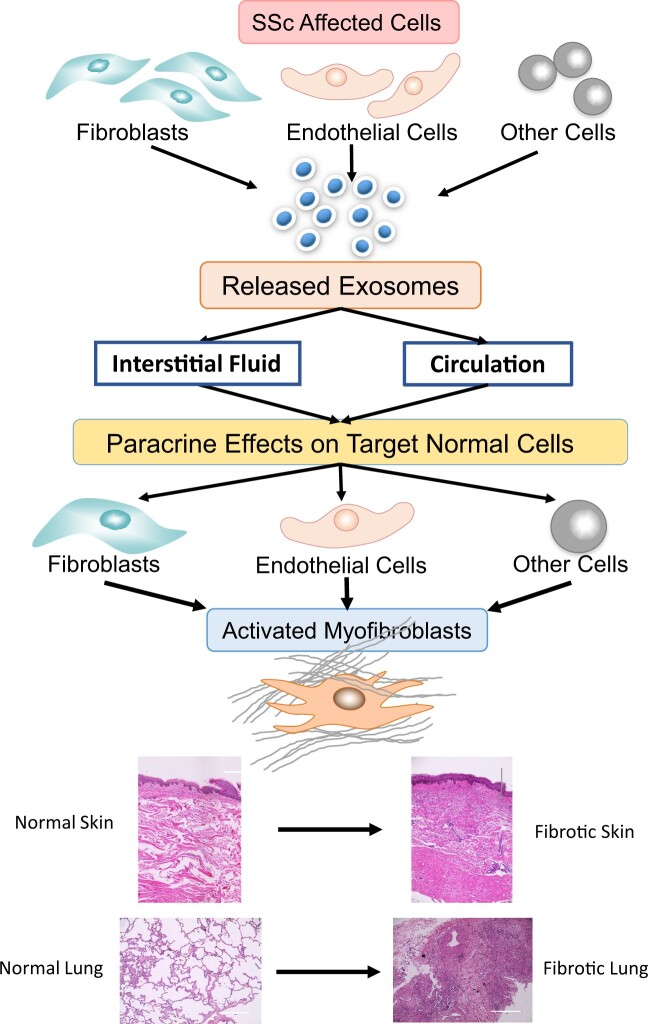

Fig. 1.

Hypothetical role of exosome-mediated paracrine effects in the extension of tissue fibrosis and in SSc

Exosomes released from affected SSc cells reach normal target cells through the interstitial fluid or the circulation and become internalized by the target cells. The exosomes release their macromolecular cargo that induces the paracrine conversion of the target cells into activated myofibroblasts. Activated myofibroblasts cause the deposition of fibrotic tissue, as illustrated for skin and lungs.

Definition of exosomes

The hypothesis proposed here suggests that exosomes released from affected SSc cells play a crucial role in the extension of SSc fibrotic alterations to normal or nonaffected tissues. The term ‘exosome’ has been utilized in the scientific literature to describe several distinct molecular entities [17–24], therefore it is necessary to clarify and specify what are the molecular structures termed exosomes that are suggested to be involved in the proposed hypothesis. The marked controversy resulting from the use of the same nomenclature to describe clearly distinct molecular entities with vastly diverse and distinct functions has been extensively discussed [25–27]. Currently it is generally accepted that the term ‘exosome’ should be utilized to refer to a specific and distinct subtype of membrane-surrounded microvesicles released from cells into the extracellular space and that may reach the circulation. We will refer to these microvesicles as exosomes throughout this article.

Exosomes are produced essentially by all cells and are characterized by specific morphological, biochemical/molecular and functional features, as discussed extensively in numerous reviews [28–33]. Exosomes are distinguished from other extracellular vesicles (EVs) based on their size (30–150 nm), their unique biogenesis and their content of specific macromolecular components that include mRNAs, miRNAs, proteins, cytokines and growth factors, lipids and even some DNA fragments [34–43]. Although the macromolecular content of exosomes reflects the functional and pathologic status of the cells of origin [44, 45], it must be emphasized that there is molecular selectivity, with some molecules being preferentially and selectively loaded into the exosomes. Despite the substantial functional relevance of this process, there is very little knowledge about the mechanisms involved in the selective loading of cellular macromolecules into exosomes. It is generally accepted, however, that the assessment of exosome content, particularly of proteins and miRNAs, has the potential to provide insights into the pathogenesis of various diseases as well as valuable diagnostic biomarkers [46–48].

Biogenesis of exosomes

The biogenesis of exosomes is highly complex and involves numerous cell membrane and intracellular steps [49–52]. Briefly, this process is initiated by the invagination of plasma membrane vesicles known as endosomes. Endosomes are internalized and following their internalization they coalesce, resulting in the formation of multivesicular bodies (MVBs). The MVBs contain numerous lipid bilayer–surrounded intracellular microvesicles that are then loaded with specific macromolecular components including mRNA, miRNA, DNA, proteins and lipid molecules [53, 54]. The MVBs may either be shuttled to lysosomal degradation or fuse back with the plasma membrane and are then released as microvesicles into the pericellular space, as diagrammatically illustrated in Fig. 2. Some of the released microvesicles can then be referred to as exosomes, depending on their size and other characteristics that differentiate them from other secreted EVs and from apoptotic bodies [29, 32, 33, 37]. Multiple proteins and lipids participate in the complex and highly regulated process of exosome microvesicle biogenesis [55–62]. Following the assembly and macromolecular loading, the exosomes are ready for their release into the extracellular/pericellular space. Numerous proteins, various glycans and some specific lipid-modifying enzymes are involved in the complex pathways of exosome release [63–66]. It must be emphasized, however, that this is a gross simplification of a highly complex sequence of molecular events that has not been fully elucidated and that will require extensive further investigation before reaching a full understanding of its intricacies, particularly in relation to the regulation of microvesicle macromolecular content and exosome release into the extracellular space. Of substantial relevance has been the demonstration that the exosome cargo represents specific sets of macromolecules and it is likely that the specific macromolecule levels and composition depend on the cells of exosome origin and, most importantly, that they may vary according to the functional or pathologic status of the cells of their origin [44, 45].

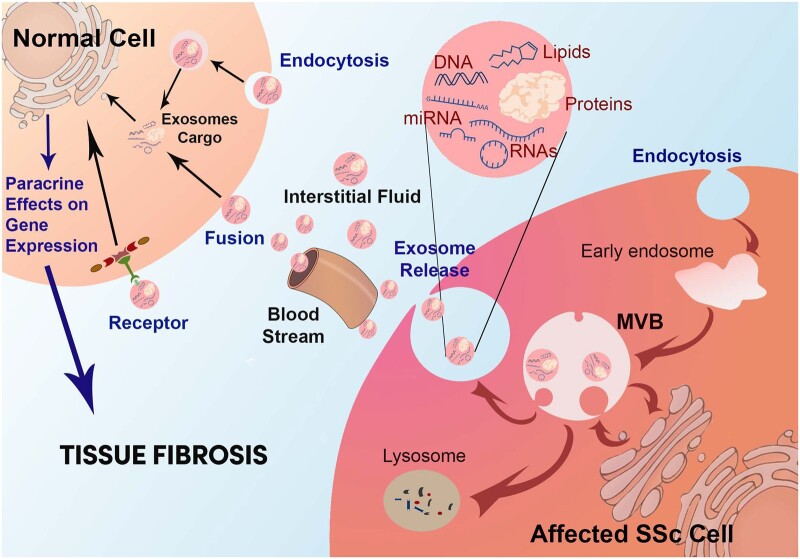

Fig. 2.

Exosome profibrotic paracrine effects on target cells

Exosome microvesicles are generated by intracellular budding of early endosomes followed by loading of multiple macromolecules generating MVBs. MVBs fuse with the plasma membrane for exosome release. Alternatively, MVBs may fuse with lysosomes and undergo degradation. Following their release, exosomes reach distant target cells through the interstitial fluid or the circulation, bind to the normal target cells, become internalized and release their macromolecular cargo. The exosome macromolecules induce potent molecular and biological effects in the target cells through paracrine mechanisms, resulting in tissue fibrosis.

Exosomes as mediators of intercellular communications

An early study of Raposo et al. [23] provided strong evidence to indicate that exosomes may be an important mechanism of intercellular communication. These data suggest that exosomes are capable of establishing intercellular communications and that this mechanism may play a role in the process of antigen presentation in vivo. These pioneering studies have been extended to a variety of cells and tissues and currently it is generally accepted that exosomes are one of the most important mechanisms for intercellular communication [67–80].

Once the exosomes reach their target cell, they can bind to the target cell surface, undergo internalization and release their macromolecular content, resulting in modification of molecular pathways and gene expression of the target cells [81–85]. Extensive investigation has indicated that the exosome uptake by target cells is multifactorial and mediated by distinct pathways, including ligand–receptor interactions, receptor-mediated endocytosis, micropinocytosis and lipid raft–mediated internalization. Furthermore, it has been shown that this process may involve various proteins, most importantly scavenger receptors and heat shock proteins [86–88]. It has also been suggested that the process of exosome uptake can be highly regulated and that certain classes of exosomes may contain specific targeting molecules on their surface, leading to some degree of selectivity towards recipient target cells and tissues [89].

Following exosome internalization, the exosome macromolecular contents become released inside the target cells and then they are able to interact with specific gene promoters or other molecular pathways, inducing profound modifications of relevant cellular processes in the target cells that may result in a change of the target cell original phenotype. The mechanisms by which the exosome bioactive cargo macromolecules impact the molecular and gene expression programs of target cells are highly complex and may depend on the particular macromolecular cargo involved as well as on the specific genetic elements and molecular pathways that may become modified. However, it is generally accepted that the most relevant macromolecules contained within exosomes capable of inducing these phenotypic changes in the target cells are miRNAs and proteins. The potential mechanisms involved in the modulation of cellular functions by the internalized exosome macromolecules may include epigenetic reprogramming of target cells induced by exosome-contained miRNA or functional RNA or post-translational modifications of target cell molecules mediated by exosome cargo proteins and lipids. Other potential mechanisms causing molecular changes in the target cells induced by the exosomes may include transfer of activated receptors or direct binding of exosome surface ligands to target cell surface receptors [74, 89].

Role of exosomes in the extension of the SSc fibrotic process

One of the remarkable clinicopathological manifestations of SSc is the extension and progression of the fibrotic process to normal or nonaffected tissues and organs [1–5]. The intimate molecular mechanisms responsible for this SSc pathogenetic event have not been fully elucidated despite its crucial importance for the treatment and clinical outcome of the disease. However, extensive studies have indicated that the cellular elements responsible for the initiation and progression of tissue fibrosis in SSc are a unique class of mesenchymal cells known as myofibroblasts [90–96].

Myofibroblasts originate from multiple sources [91, 92] and are the effector cells responsible for SSc fibrosis. In SSc, the plasticity of fibroblasts in normal or nonaffected tissues enables them to become converted into activated myofibroblasts following stimulation with specific molecular mediators. Activated myofibroblasts are characterized by intracellular accumulation of stress fibers, expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and increased production and secretion of profibrotic extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. They also display increased contractility and enhanced mechanical interaction with the ECM. The persistent stimulation from exosomes released from affected cells leads to the activation of biosynthetically quiescent cells to metabolically active fibrosis-inducing cells or myofibroblasts with distinct transcriptomic profiles and functions. The origins of the exosome-activated myofibroblasts are multiple and may include the activation of quiescent tissue fibroblasts or the phenotypic conversion of nonfibroblastic cells, including endothelial cells through endothelial–mesenchymal transition, also known as EndoMT, or adipocytes through adipocyte–myofibroblast transition [16, 97–100]. Furthermore, it is possible that exosomes may also activate bone marrow–derived fibrocytes present in the normal tissues [101]. However, there are no studies that have examined the effects of exosomes on fibrocytes.

Paracrine effects of exosomal macromolecules on target normal or nonaffected cells

Although there is extensive evidence supporting the involvement of exosomes in the development of tissue fibrotic responses and their role in various fibrotic diseases [102–104], the detailed mechanisms have not been fully elucidated. Here we review evidence supporting a truly novel mechanism to explain the progression of the fibrotic process in SSc from affected cells to normal cells mediated by exosomes and suggest that the specific exosomal macromolecular content may induce paracrine effects that may play a causal role in the induction and establishment of a profibrotic phenotype in target cells, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The target cells may include normal quiescent fibroblasts, endothelial cells, adipocytes and perhaps other important cell types contained within adjacent or distant normal or nonaffected tissues. The target cells may also include some diseased/affected cells and result in a self-powered activation or stimulation circle.

There are very few studies that have examined directly the molecular effects of exosomes isolated from the serum of SSc patients on the patterns of gene expression, protein production and other phenotypic characteristics of target cells. One of the earliest studies that examined the direct effects of SSc serum exosomes on the gene expression patterns of target fibroblasts evaluated the effects of exosome-containing culture media and exosome-depleted media on cultured normal dermal fibroblasts [105]. The exosome preparations were obtained from cultured normal and SSc dermal fibroblasts. The expression of mRNA levels of COL1A1 and COL1A2 were quantitatively assessed and the results showed that these transcripts were significantly induced by the exosome-containing media derived from SSc fibroblasts compared with SSc exosome-depleted media from the same cells. In contrast, the exosomes isolated from normal fibroblasts were not able to induce an elevation of these transcript levels [105].

A similar study analyzed exosomes isolated from the serum of patients with limited or diffuse SSc and tested their ability to induce a profibrotic phenotype in normal human dermal fibroblasts in vitro [15]. The results showed that exosomes isolated from the serum of SSc patients induced a profibrotic phenotype on cultured normal dermal fibroblasts. Furthermore, the induction of the expression of genes encoding profibrotic proteins was substantially greater with exosome samples isolated from patients with diffuse SSc compared with exosomes from patients with limited SSc [15]. The main focus of this study was to identify potential miRNAs contained within exosomes that may be involved in the induction of the fibrotic phenotype. The experimental design was based on previous experimental evidence indicative of a crucial role of miRNAs in the regulation of the fibrotic process in SSc [106]. Given the remarkable regulatory effects of miRNAs on the expression of a large number of relevant genes, it is expected that the exploration of exosomal miRNA contribution to the paracrine phenotypic conversion of normal fibroblasts and endothelial cells into activated myofibroblasts will allow the identification of potential therapeutic targets for the fibrotic process in SSc.

Although it has been shown that several miRNAs play important roles in SSc pathogenesis, displaying either profibrotic or antifibrotic effects on gene expression and inducing important changes in the expression of fibrosis-related genes [106–109], the potential paracrine effects leading to the activation of profibrotic pathways in relevant cells from adjacent normal or nonaffected tissues or even at distant organs has not been previously examined. In our previous study [15], several miRNAs implicated in the stimulation of profibrotic target genes or inhibition of antifibrotic genes were significantly increased in exosomes isolated from SSc serum compared with exosomes isolated from normal subjects. In particular, several profibrotic miRNAs were increased and some antifibrotic miRNAs were decreased in exosomes isolated from SSc patient serum. These results were consistent with previous publications in the literature that described changes in the expression levels of several miRNAs in the serum SSc patients [109–111]. Table 1 shows a list of potential profibrotic and antifibrotic exosomal miRNAs that may play a role in the development or progression of the fibrotic process in SSc.

Table 1.

miRNAs present in exosomes isolated from SSc patients serum that may play a role in SSc fibrosis

| miRNA | Potential role in SSc |

|---|---|

| let-7a | Antifibrotic |

| let-7g | Profibrotic |

| miR-17 | Not clear |

| miR-21 | Profibrotic |

| miR-29a | Antifibrotic |

| miR-92a | Not clear |

| miR-125b | Antifibrotic |

| miR-140 | Antifibrotic |

| miR-150 | Not clear |

| miR-155 | Profibrotic |

| miR-196a | Antifibrotic |

Effects of exosomes on the phenotype and gene expression of target endothelial cells

Despite the great relevance of the potential role of endothelial cell alterations to SSc pathogenesis, there are very few studies that have examined the effects of exosomes and exosomal content on the phenotype of endothelial cells. One of the few published studies examined exosomes isolated from plasma and from supernatants of cultured peripheral blood mononuclear cells or neutrophils from patients with dcSSc and performed a detailed analysis of their effects on normal human umbilical endothelial cells [112]. The isolated exosomes were extensively characterized, including their identification by transmission electron microscopy. Proliferation, migration and scratch assays were performed to examine in vitro the exosome effects on various functional and molecular gene expression parameters of the endothelial cells. The results showed that plasma and neutrophil exosomes isolated from SSc patients caused suppression of cellular proliferation and in vitro motility and scratch wound healing of cultured endothelial cells. These studies also showed that the transwell migration of the cultured normal endothelial cells was substantially reduced by SSc neutrophil exosomes. Notably, these effects were substantially more pronounced with the SSc exosome samples compared with the exosomes isolated from normal control individuals. The results indicated that SSc exosomes isolated from both plasma and neutrophils can suppress the proliferation and the motility and migration of normal endothelial cells [112].

Molecular mechanisms involved in exosome paracrine effects

Although the full spectrum and the precise molecules responsible for the phenotypic change of normal target cells to activated myofibroblasts induced by the exosomes released from SSc-affected cells have not been identified, it is highly likely this may include miRNAs, other forms of noncoding RNAs and multiple proteins, growth factors such as TGF-β and cytokines such as some of the interleukins. Similar effects have been described in a study that examined exosome and exosomal miRNAs isolated from pathologic muscle-derived fibroblasts on the phenotype of normal fibroblasts [113]. Also, there is recent interest in similar mechanisms modulating vascular and immunologic components of SSc pathogenesis by miRNAs [114]. Although the focus of these latter studies was on miRNAs, recent studies have examined the effects of other exosome macromolecules, and it has been shown that potent molecular effects may be caused by specific proteins carried by or contained within exosomes. For example, it has been recently described that Wnt proteins are carried on the surface of exosomes and can induce Wnt signaling activity in the target cells [115]. Regarding the molecular mechanisms involved in the remarkable effects of exosome macromolecules on the phenotype of various target cells, it is likely that most of them are mediated by epigenetic regulatory mechanisms as discussed recently [116–118], however, this is a highly complex issue and extensive investigation will be required to fully clarify the molecular events involved.

Role of exosomal miRNAs in the extension of SSc tissue fibrosis to normal or nonaffected tissues

There are no studies that have examined directly the role of exosomal miRNA or other exosome cargo macromolecules on the extension of the fibrotic process in SSc. Here we have proposed the hypothesis that exosomes released from affected SSc cells may reach distant normal target cells and, following their contact and fusion with these cells, may discharge their macromolecular content and exert potent paracrine effects in the target cells. The most likely exosome cargo macromolecules inducing these effects are miRNAs, growth factors, cytokines and other proteins. The profound molecular alterations induced by the exosome macromolecular cargo result in a change in the phenotype of the target cells that include normal fibroblasts, endothelial cells, adipocytes and other potential target cells, turning them into activated myofibroblasts. Identification of the precise exosome macromolecules involved in the induction of paracrine phenotypic conversion of normal cells to profibrotic cells and confirmation of such a novel molecular mechanism proposed in the hypothesis may provide previously unidentified molecular pathways involved in SSc pathogenesis and, more importantly, may allow the development of therapeutic approaches that may prevent or reverse the extension of the SSc fibrotic process and improve patient prognosis and survival.

Conclusion

One remarkable feature of the pathogenesis of SSc is the extension of the fibrotic process from affected cells to normal or nonaffected cells. This is a crucial event during the development and progression of SSc and it is a determinant of the clinical outcome and prognosis of the disease. Despite its clinical significance, the mechanisms responsible for the extension of the fibrotic process in SSc have not been fully identified. Here we suggest that the extension of the fibrotic process to normal and nonaffected cells in SSc may be mediated by exosomes released from SSc-affected cells. Exosomes are 30–150 nm microvesicles released from all cells into the extracellular space that can be transported through the circulation to reach and bind distant target cells. Exosomes contain numerous macromolecules including miRNAs, proteins, cytokines and growth factors. Following binding to the target cells, the exosomes become internalized and release their macromolecular content inside the target cells. The potential target cells may include fibroblasts, endothelial cells, adipocytes and other cells. The hypothesis further suggests that specific macromolecular components of the exosome cargo induce potent molecular and gene expression effects on the target cells that result in their phenotypic conversion into activated myofibroblasts, the cells ultimately responsible for the fibrotic process in SSc. It is also possible that the target cells may include already affected SSc cells. This possibility may result in the establishment of a self-activating circle that further enhances the severity of the fibrotic process.

Experimental confirmation of the proposed hypothesis and identification of the precise exosome macromolecules involved in the generation of activated myofibroblasts may provide unique therapeutic targets for preventing or reversing the extension of the SSc fibrotic process and thus improving the overall prognosis and survival of SSc patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Megan Chambers and Alana Pagano for their assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. S.P-V. was responsible for preparation and design of the figures. S.P-V. and S.A.J. were responsible for drafting or revision of the manuscript and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/ National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant AR071644 (to S.A.J.). The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct or reporting of this study.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Sergio A Jimenez, Jefferson Institute of Molecular Medicine and The Scleroderma Center, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Sonsoles Piera-Velazquez, Jefferson Institute of Molecular Medicine and The Scleroderma Center, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1. Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T.. Scleroderma. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1989–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allanore Y, Simms R, Distler O. et al. Systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2015;1:15002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Denton CP, Khanna D.. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017;390:1685–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Asano Y. Systemic sclerosis. J Dermatol 2018;45:128–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Varga J, Abraham D.. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest 2007;117:557–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J. et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clements PJ, Medsger TA Jr, Feghali CA.. Cutaneous involvement in systemic sclerosis. In: Clements PJ, Furst DE, eds. Systemic sclerosis. 2nd edn.Philadelphia, PA, USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2004:129–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herrick AL, Assassi S, Denton CP.. Skin involvement in early diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis: an unmet clinical need. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2022;18:276–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krieg T, Takehara K.. Skin disease: a cardinal feature of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;48:iii14–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Domsic RT, Rodriguez-Reyna T, Lucas M, Fertig N, Medsger TA Jr.. Skin thickness progression rate: a predictor of mortality and early internal organ involvement in diffuse scleroderma. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:104–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumánovics G, Péntek M, Bae S. et al. Assessment of skin involvement in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56(Suppl 5):v53–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nikpour M, Baron M.. Mortality in systemic sclerosis: lessons learned from population-based and observational cohort studies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014;26:131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rubio-Rivas M, Royo C, Simeón CP, Corbella X, Fonollosa V.. Mortality and survival in systemic sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014;44:208–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jaafar S, Lescoat A, Huang S. et al. Clinical characteristics, visceral involvement, and mortality in at-risk or early diffuse systemic sclerosis: a longitudinal analysis of an observational prospective multicenter US cohort. Arthritis Res Ther 2021;23:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wermuth PJ, Piera-Velazquez S, Jimenez SA.. Exosomes isolated from serum of systemic sclerosis patients display alterations in their content of profibrotic and antifibrotic microRNA and induce a profibrotic phenotype in cultured normal dermal fibroblasts. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017;35:21–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ. et al. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol 2007;170:1807–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fox AS, Duggleby WF, Gelbart WM, Yoon SB.. DNA-induced transformation in Drosophila: evidence for transmission without integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1970;67:1834–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pan BT, Johnstone RM.. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: selective externalization of the receptor. Cell 1983;33:967–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pan BT, Teng K, Wu C, Adam M, Johnstone RM.. Electron microscopic evidence for externalization of the transferrin receptor in vesicular form in sheep reticulocytes. J Cell Biol 1985;101:942–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammond JR, Orr L, Turbide C.. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J Biol Chem 1987;262:9412–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johnstone RM, Mathew A, Mason AB, Teng K.. Exosome formation during maturation of mammalian and avian reticulocytes: evidence that exosome release is a major route for externalization of obsolete membrane proteins. J Cell Physiol 1991;147:27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harding C, Heuser J, Stahl P.. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J Cell Biol 1983;97:329–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raposo G, Nijman HW, Stoorvogel W. et al. B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J Exp Med 1996;183:1161–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mitchell P, Petfalski E, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Tollervey D.. The exosome: a conserved eukaryotic RNA processing complex containing multiple 3′–>5′ exoribonucleases. Cell 1997;91:457–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raposo G, Stoorvogel W.. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol 2013;200:373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Witwer KW, Thery C.. Extracellular vesicles or exosomes? On primacy, precision, and popularity influencing a choice of nomenclature. J Extracell Vesicles 2019;8:1648167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wermuth PJ, Jimenez SA.. Molecular characteristics and functional differences of anti-PM/Scl autoantibodies and two other distinct and unique supramolecular structures known as “EXOSOMES”. Autoimmun Rev 2020;19:102644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S.. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol 2002;2:569–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. György B, Szabó TG, Pásztói M. et al. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci 2011;68:2667–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vlassov AV, Magdaleno S, Setterquist R, Conrad R.. Exosomes: current knowledge of their composition, biological functions, and diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Biochem Biophys Acta 2012;1820:940–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hessvik NP, Llorente A.. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018;75:193–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stahl PD, Raposo G.. Exosomes and extracellular vesicles: the path forward. Essays Biochem 2018;62:119–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kalluri R, LeBleu VS.. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020;367:eaau6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pant S, Hilton H, Burczynski ME.. The multifaceted exosome: biogenesis, role in normal and aberrant cellular function, and frontiers for pharmacological and biomarker opportunities. Biochem Pharmacol 2012;83:1484–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kosaka N, Yoshioka Y, Hagiwara K. et al. Trash or treasure: extracellular microRNAs and cell-to-cell communication. Front Genet 2013;4:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gusachenko ON, Zenkova MA, Vlassov VV.. Nucleic acids in exosomes: disease markers and intercellular communication molecules. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2013;78:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C.. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2014;30:255–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang J, Li S, Li L. et al. Exosome and exosomal microRNA: trafficking, sorting, and function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 2015;13:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raposo G, Stahl PD.. Extracellular vesicles: a new communication paradigm? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019;20:509–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL. et al. Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell 2019;177:428–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Elzanowska J, Semira C, Costa-Silva B.. DNA in extracellular vesicles: biological and clinical aspects. Mol Oncol 2021;15:1701–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gurunathan S, Kang MH, Kim JH.. A comprehensive review on factors influences biogenesis, functions, therapeutic and clinical implications of exosomes. Int J Nanomedicine 2021;16:1281–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Simpson RJ, Lim JW, Moritz RL, Mathivanan S.. Exosomes: proteomic insights and diagnostic potential. Expert Rev Proteomics 2009;6:267–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. De Jong OG, Verhaar MC, Chen Y. et al. Cellular stress conditions are reflected in the protein and RNA content of endothelial cell-derived exosomes. J Extracell Vesicles 2012;1:18396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Willms E, Johansson HJ, Mäger I. et al. Cells release subpopulations of exosomes with distinct molecular and biological properties. Sci Rep 2016;6:22519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Turchinovich A, Drapkina O, Tonevitsky A.. Transcriptome of extracellular vesicles: state-of-the-art. Front Immunol 2019;10:202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li M, Zeringer E, Barta T. et al. Analysis of the RNA content of the exosomes derived from blood serum and urine and its potential as biomarkers. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2014;369:20130502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang J, Yue BL, Huang YZ. et al. Exosomal RNAs: novel potential biomarkers for diseases—a review. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kowal J, Tkach M, Théry C.. Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2014;29:116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liu H, Tang WH.. Exosomes: biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci 2019;9:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pegtel DM, Gould SJ.. Exosomes. Annu Rev Biochem 2019;88:487–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gurung S, Perocheau D, Touramanidou L, Baruteau J.. The exosome journey: from biogenesis to uptake and intracellular signalling. Cell Commun Signal 2021;19:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Denzer K, Kleijmeer MJ, Heijnen HF, Stoorvogel W, Geuze HJ.. Exosome: from internal vesicle of the multivesicular body to intercellular signaling device. J Cell Sci 2000;113:3365–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Février B, Raposo G.. Exosomes: endosomal-derived vesicles shipping extracellular messages. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2004;16:415–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S. et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol 2010;12:19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Blanc L, Vidal M.. New insights into the function of Rab GTPases in the context of exosomal secretion. Small GTPases 2018;9:95–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hyenne V, Apaydin A, Rodriguez D. et al. RAL-1 controls multivesicular body biogenesis and exosome secretion. J Cell Biol 2015;211:27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Henne WM, Buchkovich NJ, Emr SD.. The ESCRT pathway. Dev Cell 2011;21:77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Colombo M, Moita C, van Niel G. et al. Analysis of ESCRT functions in exosome biogenesis, composition and secretion highlights the heterogeneity of extracellular vesicles. J Cell Sci 2013;126:5553–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Christ L, Raiborg C, Wenzel EM, Campsteijn C, Stenmark H.. Cellular functions and molecular mechanisms of the ESCRT membrane-scission machinery. Trends Biochem Sci 2017;42:42–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vietri M, Radulovic M, Stenmark H.. The many functions of ESCRTs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020;21:25–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Andreu Z, Yáñez-Mó M.. Tetraspanins in extracellular vesicle formation and function. Front Immunol 2014;5:442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ghossoub R, Lembo F, Rubio A. et al. Syntenin-ALIX exosome biogenesis and budding into multivesicular bodies are controlled by ARF6 and PLD2. Nat Commun 2014;5:3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Larios J, Mercier V, Roux A, Gruenberg J.. ALIX- and ESCRT-III-dependent sorting of tetraspanins to exosomes. J Cell Biol 2020;219:e201904113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Baietti MF, Zhang Z, Mortier E. et al. Syndecan-syntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat Cell Biol 2012;14:677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liang Y, Eng WS, Colquhoun DR. et al. Complex N-linked glycans serve as a determinant for exosome/microvesicle cargo recruitment. J Biol Chem 2014;289:32526–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Valadi K, Ekström A, Bossios M. et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol 2007;9:654–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Yoshioka Y. et al. Secretory mechanisms and intercellular transfer of microRNAs in living cells. J Biol Chem 2010;285:17442–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Simons M, Raposo G.. Exosomes – vesicular carriers for intercellular communication. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2009;21:575–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Théry C, Ostrowski M, Segura E.. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9:581–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ.. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics 2010;73:1907–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yuana Y, Sturk A, Nieuwland R.. Extracellular vesicles as an emerging mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Biochem Pharmacol 2012;83:1484–94.22230477 [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ludwig AK, Giebel B.. Exosomes: small vesicles participating in intercellular communication. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2012;44:11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Christianson HC, Svensson KJ, Belting M.. Exosome and microvesicle mediated phene transfer in mammalian cells. Semin Cancer Biol 2014;28:31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Turturici G, Tinnirello R, Sconzo G, Geraci F.. Extracellular membrane vesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication: advantages and disadvantages. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2014;306:C621–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lo Cicero A, Stahl PD, Raposo G.. Extracellular vesicles shuffling intercellular messages: for good or for bad. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2015;35:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kourembanas S. Exosomes: vehicles of intercellular signaling, biomarkers, and vectors of cell therapy. Annu Rev Physiol 2015;77:13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Tkach M, Théry C.. Communication by extracellular vesicles: where we are and where we need to go. Cell 2016;164:1226–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Théry C.. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol 2019;21:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Camussi G, Deregibus MC, Bruno S, Cantaluppi V, Biancone L.. Exosomes/microvesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Kidney Int 2010;78:838–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Tian T, Zhu YL, Hu FH. et al. Dynamics of exosome internalization and trafficking. J Cell Physiol 2013;228:1487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. McKelvey KJ, Powell KL, Ashton AW, Morris JM, McCracken SA.. Exosomes: mechanisms of uptake. J Circ Biomark 2015;4:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Prada I, Meldolesi J.. Binding and fusion of extracellular vesicles to the plasma membrane of their cell targets. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cai J, Han Y, Ren H. et al. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of donor genomic DNA to recipient cells is a novel mechanism for genetic influence between cells. J Mol Cell Biol 2013;5:227–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Mulcahy LA, Pink RC, Carter DR.. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J Extracell Vesicles 2014;3:24641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kanno S, Hirano S, Sakamoto T. et al. Scavenger receptor MARCO contributes to cellular internalization of exosomes by dynamin-dependent endocytosis and micropinocytosis. Sci Rep 2020;10:21795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Svensson KJ, Christianson HC, Wittrup A. et al. Exosome uptake depends on ERK1/2-heat shock protein 27 signaling and lipid Raft-mediated endocytosis negatively regulated by caveolin-1. J Biol Chem 2013;288:17713–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tian T, Zhu YL, Zhou YY, Liang GF. et al. Exosome uptake through clathrin-mediated endocytosis and macropinocytosis and mediating miR-21 delivery. J Biol Chem 2014;289:22258–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Murphy DE, de Jong OG, Brouwer M. et al. Extracellular vesicle-based therapeutics: natural versus engineered targeting and trafficking. Exp Mol Med 2019;51:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Beon M, Harley RA, Wessels A, Silver RM, Ludwicka-Bradley A.. Myofibroblast induction and microvascular alteration in scleroderma lung fibrosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2004;22:733–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. McAnulty RJ. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts: their source, function and role in disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007;39:666–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Abraham DJ, Eckes B, Rajkumar V, Krieg T.. New developments in fibroblast and myofibroblast biology: implications for fibrosis and scleroderma. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2007;9:136–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Gilbane AJ, Denton CP, Holmes AM.. Scleroderma pathogenesis: a pivotal role for fibroblasts as effector cells. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Stern EP, Denton CP.. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2015;41:367–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Pattanaik D, Brown M, Postlethwaite BC, Postlethwaite AE.. Pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Front Immunol 2015;6:272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. van Caam A, Vonk M, van den Hoogen F, van Lent P, van der Kraan P.. Unraveling SSc pathophysiology; the myofibroblast . Front Immunol 2018;9:2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Postlethwaite AE, Shigemitsu H, Kanangat S.. Cellular origins of fibroblasts: possible implications for organ fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004;16:733–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Marangoni RG, Korman B, Varga J.. Adipocytic progenitor cells give rise to pathogenic myofibroblasts: adipocyte-to-mesenchymal transition and its emerging role in fibrosis in multiple organs. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2020;22:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Brezovec N, Burja B, Lakota K.. Adipose tissue and adipose secretome in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2021;33:505–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Piera-Velazquez S, Li Z, Jimenez SA.. Role of endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) in the pathogenesis of fibrotic disorders. Am J Pathol 2011;179:1074–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Chesney J, Bucala R.. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: mesenchymal precursor cells and the pathogenesis of fibrosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2000;2:501–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Li M, Jiang M, Meng J, Tao L.. Exosomes: carriers of pro-fibrotic signals and therapeutic targets in fibrosis. Curr Pharm Des 2019;25:4496–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Qin XJ, Zhang JX, Wang RL.. Exosomes as mediators and biomarkers in fibrosis. Biomark Med 2020;14:697–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Brigstock DR. Extracellular vesicles in organ fibrosis: mechanisms, therapies, and diagnostics. Cells 2021;10:1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Nakamura K, Jinnin M, Harada M. et al. Altered expression of CD63 and exosomes in scleroderma dermal fibroblasts. J Dermatol Sci 2016;84:30–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Li H, Yang R, Fan X. et al. MicroRNA array analysis of microRNAs related to systemic scleroderma. Rheumatol Int 2012;32:307–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Henry TW, Mendoza FA, Jimenez SA.. Role of microRNA in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis tissue fibrosis and vasculopathy. Autoimmun Rev 2019;18:102396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Li L, Zuo X, Liu D, Luo H, Zhu H.. The profiles of miRNAs and lncRNAs in peripheral blood neutrophils exosomes of diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis. J Dermatol Sci 2020;98:88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Zhu H, Li Y, Qu S. et al. MicroRNA expression abnormalities in limited cutaneous scleroderma and diffuse cutaneous scleroderma. J Clin Immunol 2012;32:514–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Babalola O, Mamalis A, Lev-Tov H, Jagdeo J.. The role of microRNAs in skin fibrosis. Arch Dermatol Res 2013;305:763–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Zhu H, Luo H, Zuo X.. MicroRNAs: their involvement in fibrosis pathogenesis and use as diagnostic biomarkers in scleroderma. Exp Mol Med 2013;45:e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Li L, Zuo X, Xiao Y. et al. Neutrophil-derived exosome from systemic sclerosis inhibits the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2020;526:334–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Zanotti S, Gibertini S, Blasevich F. et al. Exosomes and exosomal miRNAs from muscle-derived fibroblasts promote skeletal muscle fibrosis. Matrix Biol 2018;74:77–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Colletti M, Galardi A, De Santis M. et al. Exosomes in systemic sclerosis: messengers between immune, vascular and fibrotic components? Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Gross JC, Chaudhary V, Bartscherer K, Boutros M.. Active Wnt proteins are secreted on exosomes. Nat Cell Biol 2012;14:1036–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ramahi A, Altorok N, Kahaleh B.. Epigenetics and systemic sclerosis: an answer to disease onset and evolution? Eur J Rheumatol 2020;7:147–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Tsou P-S, Varga J, O’Reilly S.. Advances in epigenetics in systemic sclerosis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nature Rev Rheumatol 2021;17:596–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Camussi G, Deregibus MC, Bruno S. et al. Exosome/microvesicle-mediated epigenetic reprogramming of cells. Am J Cancer Res 2011;1:98–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). All data relevant to the study are included in the article.