Abstract

High-throughput sequencing provides sufficient means for determining genotypes of clinically important pharmacogenes that can be used to tailor medical decisions to individual patients. However, pharmacogene genotyping, also known as star-allele calling, is a challenging problem that requires accurate copy number calling, structural variation identification, variant calling, and phasing within each pharmacogene copy present in the sample. Here we introduce Aldy 4, a fast and efficient tool for genotyping pharmacogenes that uses combinatorial optimization for accurate star-allele calling across different sequencing technologies. Aldy 4 adds support for long reads and uses a novel phasing model and improved copy number and variant calling models. We compare Aldy 4 against the current state-of-the-art star-allele callers on a large and diverse set of samples and genes sequenced by various sequencing technologies, such as whole-genome and targeted Illumina sequencing, barcoded 10x Genomics, and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) HiFi. We show that Aldy 4 is the most accurate star-allele caller with near-perfect accuracy in all evaluated contexts, and hope that Aldy remains an invaluable tool in the clinical toolbox even with the advent of long-read sequencing technologies.

The rapid development of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technologies has ushered in the era of precision medicine that aims to tailor medical decisions at the individual level (Hamburg and Collins 2010). A key component of precision medicine is pharmacogenomics, which studies the associations between the individual genotypes of clinically important genes (also known as pharmacogenes) and individual variation in drug response (Weinshilboum and Wang 2017). Although the HTS data theoretically provide sufficient means to accurately genotype any gene in a given individual, genotyping of many pharmacogenes remains challenging (Twesigomwe et al. 2020). One of the key challenges is the fact that many pharmacogenes of vital clinical importance—most notably the CYP2D6 gene, whose genotype impacts up to 25% of clinically prescribed drugs (Ingelman-Sundberg 2005)—are highly polymorphic and, furthermore, are located next to the highly similar pseudogenes owing to being located within segmental duplications (Ingelman-Sundberg 2005). Many of these pharmacogenes are also subject to various copy number and structural changes, for example, through a fusion event between a gene and its pseudogene, possibly owing to the instability of the segmental duplication region wherein they reside (Sezutsu et al. 2013). These issues need to be carefully and comprehensively accounted for before the genotyping process in order to obtain accurate results. Lastly, alleles of many pharmacogenes are not defined through a single-nucleotide variant (SNV) but through a complete gene haplotype. Thus, the exact functional impact of an allele can only be determined through phasing, or haplotyping, of the whole genic region. In the pharmacogenomics community, haplotyping is commonly known as star-allele calling (Robarge et al. 2007), owing to the fact that most of the known pharmacogenetic haplotypes are assigned a unique star-allele identifier.

Standard tools for genotyping HTS data sets, such as the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) (McKenna et al. 2010; Poplin et al. 2017), cannot be used for star-allele calling because they are unable to haplotype the whole genic regions and assign correct star-alleles. General-purpose computational phasing tools, such as HapCUT2 (Edge et al. 2017) and HapTree-X (Berger et al. 2020), are also inadequate for calling star-alleles: Either these tools are designed for phasing diploid organisms and thus cannot phase regions that underwent significant copy number changes or they cannot handle fusions and other structural variations. Furthermore, the distance between allele-defining variants is often too large, and as a result, many alleles cannot be phased with short-read sequencing data. On the other hand, statistical phasing tools, such as Beagle (Browning et al. 2021) or Eagle (Loh et al. 2016), also do not handle the presence of fusions and structural variations. Thus, most of the star-allele calling was—and still is—being performed by various custom primer-specific PCR and array assays (Numanagić et al. 2015), mostly owing to their price and speed, despite calls generated by these assays being often limited in breadth and scope (Pratt et al. 2010; Fang et al. 2014).

Several tools have been recently developed to address the challenge of accurate star-allele calling (Caspar et al. 2020). Cypiripi (Numanagić et al. 2015), the first tool specifically designed for this purpose, supported calling CYP2D6 star-alleles from Illumina WGS data. Cypiripi was followed by Aldy (Numanagić et al. 2018), Stargazer (Lee et al. 2019), Astrolabe (Twist et al. 2016), StellarPGx (Twesigomwe et al. 2021), PharmCAT (Sangkuhl et al. 2020), and Cyrius (Chen et al. 2021). These tools aggregate the data from the existing star-allele databases, such as PharmVar (Gaedigk et al. 2018), and use it to call star-alleles directly from HTS data. Some of these tools, such as Aldy and Stargazer, are also able to detect copy number changes and fusions with a high level of accuracy. However, a majority of these tools target only a small set of pharmacogenes (typically CYP2D6 and other cytochrome P450 genes) and are tuned for short-read HTS data generated by the Illumina whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and (in some cases) targeted sequencing panels such as PGRNseq (Gordon et al. 2016).

In recent years, there has been a slow but steady shift toward third-generation HTS technologies such as Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore (De Coster et al. 2021). These technologies produce significantly longer reads (typically measured in tens of kilobases) than Illumina reads (measured in tens of base pairs). Although they were initially dismissed in clinical settings owing to the high cost of sequencing and high error rates, these technologies are making a resurgence thanks to the recent improvements in terms of accuracy and cost. For example, PacBio HiFi sequencing offers up to 25-kbp-long reads with a 99.5% accuracy rate (Hon et al. 2020). Unfortunately, not many tools are able to correctly use the data generated by these technologies for calling pharmacogenomic star-alleles owing to the different assumptions and biases compared with the standard Illumina short-read data. Star-allele callers are also unable to make use of the long-range information within long reads for better phasing of allele-defining variants.

Here we present Aldy 4, the next iteration of Aldy software that addresses the aforementioned challenges. Aldy 4 completely revamps its original star-allele calling pipeline and adds support for long-read technologies such as PacBio HiFi, while extending support for short-read technologies (whole-genome and targeted capture data). Other updates also include extensive support for genotyping whole-exome (Ly et al. 2022) and VCF data. The changes include an alignment correction module that addresses various biases and errors common during the alignment of long reads to the pharmacogenomic regions. It also provides a novel star-allele calling pipeline that incorporates the long-range phasing information from long reads into the star-allele calling model. Finally, Aldy 4 brings support for 19 new pharmacogenes, provides an easy interface for adding the support for other pharmacogenes, adds an application programming interface (API) for easy incorporation of pharmacogenomic calling within the existing pipelines, and brings various other improvements to the original pipeline. As such, we envision Aldy to be a single-stop tool for calling star-alleles from diverse sequencing technology data sets, and hope that it will remain a crucial tool in the pharmacogenomics toolbox even with the advent of long-read sequencing technologies.

Results

We have compared Aldy 4.3 (with PharmVar v5.2.3) against Astrolabe v0.8.7.2 (Twist et al. 2016), StellarPGx v1.2.5 (Twesigomwe et al. 2021), Stargazer v1.0.8 (Lee et al. 2019), and Cyrius v1.1.1 (Chen et al. 2021). Aldy 4 was also compared against Aldy v3.3 (Numanagić et al. 2018), the previous version of Aldy. The comparisons were performed on a sizeable GeT-RM set of publicly available samples and genes for which genotyping panel validations were available (Pratt et al. 2010, 2016; Gaedigk et al. 2019). These samples were sequenced with three technologies: (1) a PGRNseq v.3 Illumina-based pharmacogene-targeted panel (137 samples) (Gordon et al. 2016), (2) Illumina WGS (70 samples), and (3) 10x Genomics sequencing (95 samples). In addition to these samples, Aldy 4 was also run on the set of 45 Coriell samples sequenced by a PacBio HiFi pharmacogene-targeted panel (Portik et al. 2021; Kingan et al. 2022) and validated by Scott et al. (2021). The percentage of known alleles covered by these data sets for each evaluated gene is available in Supplemental Table S1.

Aldy 4 and other tools were run on the following 19 genes: CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2A13, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2J2, CYP2S1, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7, CYP3A43, CYP4F2, DPYD, SLCO1B1, and TPMT. Although Aldy 4 also supports additional 15 genes, their evaluation was omitted because we did not have the ground truth panel data for these genes. Note that not every tool supports all these genes: As a rule of thumb, Stargazer, Aldy 3, and Aldy 4 provide the broadest support, whereas the other tools are geared toward a small subset of these genes (typically CYP genes, such as CYP2D6 and CYP2C19).

In an ideal world, we would have a “perfect” phase for each sample and would be able to evaluate each tool against such phase. Unfortunately, the available ground truth data are obtained through genotyping panels and assays designed to detect only the common major star-alleles (or core alleles, alleles defined solely by functional, or core, variants). These panels often cannot call minor star-alleles (or suballeles, alleles defined by nonfunctional variants, or subvariants, and functionally indistinguishable from the major star-alleles), as well as less common alleles. The low resolution of the available ground truth data and the differences in database specifications between the different tools necessitated a few accommodations within the evaluation process for the sake of fairness. First, we updated ground truth calls that missed the presence of less common variants and alleles. Updates were only performed if there was a consensus between the star-allele calling tools that differed from the ground truth data and if an updated call extended the validated allele definition (i.e., if the variants defining the validated allele also form a part of the consensus definition). Note that a similar approach was used by Numanagić et al. (2018). Each updated call was further manually inspected to ensure that the variants missing from the ground truth calls are indeed present and not sequencing artifacts. In rare instances, it was hard to precisely distinguish the presence of the variant, especially if the variant allele frequency (VAF) was too low (alleles with lower VAFs are sometimes caused by the sequencing or read alignment bias, especially in the presence of pseudogenes, and are typically validated through Sanger sequencing). Samples with such variants were marked as “need validation” (Table 1). For such samples, calls that either used or ignored such ambiguous variants were deemed “correct.” Second, we have followed the common strategy used in clinical studies (Ly et al. 2022) by only comparing the major (core) star-allele calls and ignoring the minor star-allele (suballele) designations. In other words, only the phasing of functional (core) variants was considered; subvariants and silent variants that do not alter the functionality of an allele were ignored (i.e., a *1A/*2B minor star-allele call was treated as a functionally equivalent *1/*2 major star-allele call). Note that major (core) star-alleles are typically distinguished by the number (e.g., *1 functionally differs from *2), whereas minor star-alleles (suballeles) are traditionally distinguished by a letter (e.g., *2A and *2B harbor different silent variants despite sharing common core variants) or by a numerical suffix in the recent PharmVar definitions (e.g., *2.001 instead of *2A).

Table 1.

Summary of the star-allele calls generated by six tools (Aldy 4, Aldy 3, StellarPGx, Stargazer, Astrolabe, and Cyrius) on 137 GeT-RM samples sequenced by three different technologies

The further complication lies in the discrepancies among the databases themselves: Different tools ship with different databases and often augment such databases with custom entries. For that reason, identical alleles with differing names were treated equally, and ambiguities were resolved in the individual tool's favor (e.g., if a tool's call could be interpreted as correct, we called it as correct; this way, we ensured that custom database entries were accounted for). The exact criteria used for allele updates and allele comparisons are listed in the Supplemental Note S1.

Where possible, the CYP2D8 region was used as the copy number neutral region; exceptions include Aldy 4 using F1 region for the PacBio data. Some tools, such as Astrolabe and Stargazer, required VCF files; where needed, VCFs were generated by BCFtools (Li et al. 2009).

All results were obtained on machines with Intel Xeon E5-2680v4 and 8260 CPUs. Each evaluated tool genotypes a single gene in a single sample within a few minutes, regardless of the sequencing technology used. However, note that Aldy 4 only needs BAM/CRAM to run; other tools often require VCF or GDF files that can take significant time to generate.

Overall, the best accuracy on short-read data sets (PGRNseq v.3, Illumina WGS, and 10x Genomics) was achieved by Aldy 4 (98.42%), followed by Aldy 3 (96.78%), StellarPGx (90.40%), Astrolabe (86.50%), Cyrius (82.63%), and Stargazer (76.47%).

PGRNseq v.3

Aldy 4, Aldy 3, Stargazer, and Astrolabe were run on 137 PGRNseq v.3 targeted sequencing (Gordon et al. 2016) samples from the GeT-RM collection. PGRNseq v.3 targets common pharmacogenes and sequences them at high depths (up to 1000× per loci).

Note that we could not get either Stargazer or Astrolabe to run on targeted sequencing data natively; thus, VCF files were provided as an input for these tools. Because of the limited nature of VCF files, these tools were unable to call copy number changes and fusions on this data set. Although Stargazer has a mode for targeted data, we were unable to get good results with it; a detailed explanation is given in the Supplemental Notebook. The comparison with StellarPGx was omitted as it does not support targeted sequencing data.

As can be seen in Table 1, Aldy 4 identifies nearly all of the alleles in all genes correctly—more than the other two tools—with a total accuracy of 98.45%. In some cases (e.g., failed cases in the genes CYP1A1 and CYP2B6), no caller was able to call correct star-alleles because the PGRNseq panel did not sequence the variant of interest (e.g., a nonexonic downstream variant rs4646903 that defines CYP1A1*2A was not covered by the panel at all).

On this data set, Aldy 4's performance is only marginally better than Aldy 3. This is expected as neither of the model updates unique to Aldy 4 applies to the high-quality PGRNseq data set with stable coverage. Minor changes are mostly owing to the differences in the variant calling (e.g., Aldy 4's incorporation of quality scores and mapping qualities).

Illumina WGS

We have run all tools on 70 Illumina HiSeq-sequenced WGS samples from the GeT-RM sample collection. These samples were sequenced with an average depth of roughly 30×. The details are also available in Table 1.

Here, Aldy 4 again calls nearly all star-alleles correctly and genotypes more samples than the competition for every considered gene. The only exception is CYP2D6, for which Cyrius genotypes two samples (NA21781) more than Aldy 4. In this case, Aldy 4 misses the nonfunctional *68 and identifies the *2 allele as *65; however, the *65 allele extends the *2 allele with a single variant (rs1065852), and it is unclear if this allele is indeed a *2 or a *65.

Aldy 4 and other tools were able to correctly call alleles defined by intronic and downstream variants across the genes on these data. Note that the main reason behind the Stargazer's lower accuracy on this data set was copy number calling: Although Stargazer often identified the star-allele correctly, it would often call them more times than needed (e.g., *1/*2 + *2 instead of *1/*2). Note that Aldy 4 only calls copy numbers and fusions on genes that are known to harbor such changes; otherwise, it assumes that two copies are present.

Note that Astrolabe used a modified CYP4F2 database whose allele nomenclature differed from the other databases. Thus, the comparison with Astrolabe on CYP4F2 was omitted for the sake of consistency. We also observed a large number of mismatches in SLCO1B1 across all tools owing to the incomplete panel validation and inconsistent database specifications used by various tools.

Finally, the improvements in the copy number model and more sensitive variant calling in Aldy 4 account for a few improved calls on more complex CYP2D6 and CYP2A6 samples.

10x Genomics

We have run all tools on 95 GeT-RM samples sequenced by a 10x Genomics WGS sequencer. The average depth of sequencing was roughly 40×. Because several important pharmacogenes reside within repeated regions of the human genome, EMA aligner (Shajii et al. 2018) with the density-based optimization mode was used for improved alignment of the 10x reads to the reference genome (hg19 at the time of alignment; the same results should be expected when aligning the data to GRCh38 as well because the gene regions of interest did not undergo major changes between the two releases). The comparison details are available in Table 1.

Although the 10x Genomics protocol uses Illumina HiSeq for sequencing, the read coverage is not as uniform as it is in an average Illumina WGS sample; 10x-specific biases also result in quite a few misaligned reads compared with the WGS data. For this reason, the overall allele calling accuracy is lower than the WGS data set; this is especially evident in Stargazer, in which the accuracy of its copy number detection module is even lower than in WGS data.

However, Aldy 4 still correctly calls the majority of alleles (with 97.11%) accuracy, especially compared with the other tools. The most challenging genes for all tools were CYP2A6 and CYP2D6. Aldy's accuracy is lower in these genes, primarily owing to the occasional copy number mismatch (owing to the coverage unevenness) and sequencing artifacts (where many misidentified variants were either an artifact or were undersequenced). Note that Aldy 4 benefited from the novel phasing module that was able to successfully use 10x Genomics barcodes to link long-distance variants together. Finally, we observe significant improvements over Aldy 3 in CYP2D6 and CYP2A6 samples on this data set owing to an improved copy number model that better handles noisy coverage and ambiguous variants (a common case in 10x Genomics samples) and is, as such, able to improve the calling accuracy up to 30% in these genes.

PacBio HiFi

Finally, Aldy 4 was run on two sets of PacBio HiFi samples sequenced by a custom targeted pharmacogenomics panel (Portik et al. 2021; Kingan et al. 2022). The first set contained 24 samples, whereas the second set was comprised of 21 samples. The coverage of these data sets varies—it can be as low as 10×—and at times exceed even 200×. Aldy's calls were compared with those of Astrolabe. Although none of the other tools support PacBio long reads natively, we were able to at least run Astrolabe in VCF mode. The validation data were obtained from Scott et al. (2021) and Pratt et al. (2016). The call details are available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of the star-allele calls generated by Aldy 4 and Astrolabe on PacBio HiFi targeted data

Star-allele calls generated by Aldy 4 agree with the ground truth in all genes except for a few CYP2D6 calls and one CYP2C9 call. Furthermore, its calls augmented and phased many ground truth calls generated by panels with limited variant coverage with additional variants observed by PacBio data (Table 2). Aldy was also able to find and phase alleles that have not been cataloged in CYP2B6, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, DPYD, and SLCO1B1. Further validation of such novel calls, as well as of the calls that were deemed ambiguous, is needed to fully confirm and understand such alleles.

When it comes to CYP2D6, Aldy 4's calls disagree with the ground truth data owing to the difference in predicted copy number. In two instances, Aldy 4 called an additional copy (i.e., *1 + *1 instead of *1, and *4 + *4 instead of *4), whereas in the other two instances, Aldy 4 did not call an existing copy (i.e., it called *2 instead of *2 + *2 and *10 instead of *10 + *10). In one instance, Aldy called *36 instead of *10 (note that these alleles are nearly identical, with the only difference being a conversion of exon 9 in *36); in the final instance Aldy did not call the nonfunctional *68 fusion allele. In all these cases, the observed coverage was noisy, and further validation is needed to ascertain the exact copy number of these samples. Let us also point out that Astrolabe's calls in genes CYP2C19 and SLCO1B1, as well as CYP2D6 in the second data set, were highly ambiguous, often containing more than 10 functionally different solutions.

Other remarks

Many tools often confuse CYP2B6*6 and CYP2B6*9 alleles that differ only in the variant rs2279343. This variant is often either undersequenced or covered by ambiguous reads that potentially originate from the neighboring CYP2B7 pseudogene and is thus hard to call with high confidence in some technologies (e.g., PGRNseq v.3). When the true call was ambiguous, both possible calls were deemed “correct.” Similar cases were also observed with CYP2A6*1 and CYP2A6*35 alleles. Further validation is needed to properly ascertain the true existence of these alleles in problematic samples.

If multiple allele calls were generated by a tool for a given sample and gene combination, the call was deemed “correct” if at least one such multicall matched the ground truth. Note that the prevalence of multiple calls was overall low: ∼1.1% for Aldy 4, 2.7% for Aldy 3, 1.9% for Stargazer, 1.9% for StellarPGx, and 15.7% for Astrolabe. Aldy 4's new phasing model was a significant factor for a low multicall rate: Although the rate was 1.6% on PGRNseq v.3 and 1.8% on WGS samples owing to the short read lengths of such samples, it decreased to 0.5% on 10x and PacBio samples that allowed better phasing. The vast majority of ambiguous calls were observed when genotyping CYP4F2 and SLCO1B1. Finally, note that Aldy 4 generated no more than three diplotypes for each ambiguous call.

Discussion

Pharmacogenomics is becoming a key component of evidence-based medicine (Relling and Evans 2015). Genes like CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 regulate a large portion of clinically prescribed drugs; other genes, such as those in the HLA or IGH gene clusters, are vital for understanding the immune response (Ford et al. 2020, 2022). As their function is dependent on their haplotype, it is of vital importance to genotype and haplotype these genes before administering medical treatment (Crews et al. 2014). HTS technologies are a natural candidate for this process, especially when considered that the currently available clinical genotyping panels are often restricted only to the most common genotypes and struggle to detect more complex structural alterations within pharmacogenes.

In this work, we have presented Aldy 4, the first tool that can accurately and consistently call star-alleles in data from various sequencing technologies, including but not limited to long-read PacBio data, Illumina short-read sequencing in all of its flavors (i.e., whole-genome, whole-exome, and targeted capture data), as well as the 10x Genomics barcoded data. Aldy 4 achieves this by using combinatorial optimization models to solve various challenges associated with calling pharmacogenetic haplotypes from sequencing data, such as copy number and structural variation detection, variant calling, and variant phasing, ultimately resulting in a star-allele decomposition of a gene of interest. We have shown the strength of Aldy 4's approach through a series of comparisons against the current state-of-the-art star-allele callers, in which Aldy 4 performed the best. We hope that Aldy 4 will be of vital importance to clinicians in tailoring prescription recommendations, thus leading to improved medical care.

There are still some open questions left that need to be answered in future work. Most importantly, the panel-validated calls improved by the star-allele callers through the use of HTS data—often containing novel alleles not previously cataloged in the existing databases—need to be validated in a wet-laboratory environment for all genes presented, as was performed recently for a selection of CYP2C genes (Gaedigk et al. 2022). More tests are also needed on larger cohorts to accurately evaluate the precision of these tools, Aldy 4 included, on rare fusions. The incorporation of other highly polymorphic pharmacogenomics regions, such as HLA or IGH, should also be considered, as Aldy (and other evaluated pharmacogenomics tools) are currently unable to handle the complexities of such regions. Finally, the complete characterization of minor star-alleles, accompanied by the careful characterization of noncoding variants, is also needed to understand the full effect of pharmacogenes on the treatment and drug dosage decisions.

Methods

The goal of Aldy is to reconstruct the exact sequence content (or haplotype) of each gene copy of a given pharmacogene from an HTS data sample and assign a star-allele to each reconstructed haplotype present in the data set. This process is subsequently referred to as star-allele calling.

To accurately call star-alleles, it is necessary to consult a database of known star-alleles that contains the exact sequence content of each pharmacogene allele. Suppose that a pharmacogene G harbors variants , where any is a single-nucleotide substitution or a small indel. Depending on their impact on the gene G, these variants are either deemed functional (core) variants or silent variants (subvariants); although core variants are typically nonsynonymous, they might also include UTR and intronic variants that affect the drug metabolism. The reference allele of G is an allele that harbors no variants at all. It is commonly known as the *1 star-allele. Notable exceptions to this rule include CYP2C19 (where CYP2C19*1 was recently renamed to CYP2C19*38) and wild-type alleles in IFNL3 and DPYD. Any other star-allele Si is defined by the subset of known variants that distinguish its sequence content from the reference *1 allele.

In some genes, such as CYP2D6, star-allele identifiers are also assigned to fusions and other pseudogene-induced structural changes that affect the pharmacogene. For this reason, the definition of star-alleles is extended to also include their structural configuration. This configuration describes whether a pharmacogene is wholly present in the genome, is deleted, or is a gene–pseudogene hybrid. The set of valid configurations is denoted as . Note that each structural configuration can induce many distinct star-alleles depending on the choice of variants from . Thus, we can formally define a star-allele Si as a tuple (gi, Ai), where and . The star-allele database is formally a collection of all known structural configurations, variants, and known star-alleles , where Si = (gi, Ai) such that and .

To call star-alleles of a given pharmacogene from the given sequencing sample, Aldy needs to perform the following steps:

analyze the aligned HTS reads in BAM/CRAM format and resolve incorrectly aligned reads,

detect structural configurations by calling copy number changes and gene–pseudogene fusions, and

use the read alignments from BAM/CRAM to call star-alleles and phase the gene.

BAM/CRAM analysis and alignment correction

Aldy begins by taking a SAM, BAM, or CRAM file (Li et al. 2009) generated by a read aligner (e.g., BWA [Li and Durbin 2009], pbbm2 [https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/pbmm2], or minimap2 [Li 2018]). It is recommended to postprocess these files with the GATK's “best practices” pipeline (the local indel realignment step is especially helpful for the subsequent variant calling) (Van der Auwera et al. 2013). Aldy extracts the relevant variants that are present in a given pharmacogene from the alignment file, as well as coverage information needed for the copy number and structural variation detection step. It also collects phasing information from long reads, barcoded fragments, and paired-end fragments where available.

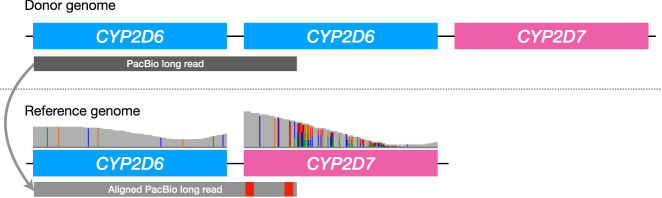

The original version of Aldy relied on the assumption that read alignments produced by the off-the-shelf aligner are mostly correct. Although this assumption holds for short paired-end Illumina reads, it breaks for long reads such as PacBio HiFi reads. For example, if a sample harbors a gene duplication and if the highly similar pseudogene is located immediately next to this gene, any long read spanning two duplicated copies of the gene will get its second half incorrectly aligned to the pseudogene because the reference genome does not contain two copies of the gene in question (Fig. 1). The correct alignment would perform a split mapping and align the second half again to the pharmacogene. These incorrect alignments are even more problematic in the presence of gene fusions: Any read that spans a gene–pseudogene fusion breakpoint will not be split-mapped but incorrectly aligned to either pharmacogene or its pseudogene.

Figure 1.

An example of an incorrect long read alignment to the reference genome and its correction. If a donor genome (above) contains two copies of CYP2D6 pharmacogene, any long read (gray rectangle) that spans both copies will get aligned to the reference genome (below) that contains only a single CYP2D6 copy. However, this read will get its second half (containing CYP2D6 sequence) incorrectly aligned to the CYP2D7 pseudogene owing to the high sequence similarity between these genes. The final result is the overabundance of coverage in the pseudogene region compared with the CYP2D6 region (an Integrative Genomics Viewer [IGV; Robinson et al. 2011] coverage plot is shown above the reference genome).

Aldy 4 corrects such alignments by splitting any long read that spans the gene–pseudogene boundary into shorter gene-level segments and aligning each segment independently. Each segment is guaranteed to span only one gene (either pharmacogene or a pseudogene) and thus avoid being misaligned in the manner described above. The size of each such segment is at most the size of the gene. Aldy 4 performs a further split-mapping of each segment that spans a potential fusion breakpoint to determine whether a read originates from a fusion event or not (a read is said to originate from a fusion event if its split-mapping alignment score is better than the original alignment score).

Unlike previous versions, Aldy 4 considers base quality scores and read mapping qualities when calling the allele-specific variants. This ensures that the low-quality variants in noisy and low-coverage samples are filtered out before the star-allele calling. Finally, Aldy 4 performs the indel-realignment step through indelpost (Hagiwara et al. 2022) to correct misalignments that often happen when aligning short reads to small indels (Li 2014).

Copy number and structural variation analysis

In a typical scenario, a sample contains two parental copies of a pharmacogene of interest for which star-alleles need to be called. This is generally true for most of the pharmacogenes of interest. However, a few major pharmacogenes do not follow this pattern and are prone to various copy number changes and structural events. The most notable example is that of the CYP2D6 gene, one of the most important pharmacogenes (Ingelman-Sundberg 2005), whose copies can undergo whole-gene deletions, duplications, and hybrid fusions (where a copy begins with the CYP2D6 sequence but switches to the pseudogene CYP2D7 sequence at a given breakpoint, or vice versa) (Kramer et al. 2009). Other prominent examples include CYP2A6, G6PD, and so on. Each copy—fusions included—yields its own star-allele. Thus, to correctly call star-alleles of such genes, it is necessary to correctly detect the total number of available gene copies as well as the configuration (i.e., structure) of each copy.

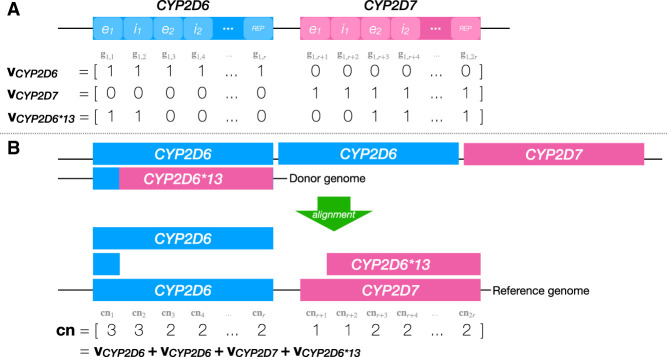

Each gene copy can be described by its structural configuration represented as a binary vector that indicates the presence or absence of genic regions in a given configuration (Fig. 2). Because each star-allele is defined by a matching structural configuration, such configurations must be found before the star-alleles can be accurately called. The size of the configuration vector depends on the number of gene segments that define various structural configurations. For example, the CYP2D6 gene is divided into r = 20 segments that correspond to its exons, introns, and flanking regions, because all structural variations are described at the level of whole exons and introns (Kramer et al. 2009). The total length of the CYP2D6 configuration vector is 2r (i.e., 40) because the vector also includes segments from the neighboring CYP2D7 pseudogene. This vector can encode any known CYP2D6 structural configuration: for example, a single CYP2D6 copy (r ones followed by r zeros), a single CYP2D7 copy (r zeros followed by r ones), CYP2D6–2D7 fusion in intron 1 (one followed by r − 1 zeros, in turn followed by a 0 and r − 1 ones), and so on. Once these vectors are established, any complex configuration within CYP2D locus can be represented as an aggregate of individual configuration vectors (for an example, see Fig. 2A). Note that valid structural configuration vectors are obtained from the corresponding allele databases and that each such vector is typically assigned a star-allele identifier (e.g., CYP2D6*13A represents a CYP2D6 fusion with the breakpoint in exon 1).

Figure 2.

A sample decomposition of aggregate coverage into individual structural configurations. (A) An example database of CYP2D6 structural configurations containing three such configurations (vCYP2D6, vCYP2D7, and vCYP2D6*13). Regions on top of the configurations that were defined (i.e., e1, i1, etc.) are shaded with lighter color. In this example, vCYP2D6 corresponds to the g1. (B) Sample decomposition of the aggregate coverage vector cn, observed after aligning the reads originating from the donor genome (above) to the reference genome (below). As can be seen, cn can be expressed as the sum of four structural configuration vectors from the database.

In a sequenced sample, we only observe the aggregate coverage vector cn that describes the number of reads covering each genomic loci of interest within the sample (the formation of this vector is described in Supplemental Note S2; an example is shown in Fig. 2B). The goal of Aldy is to find a set of configuration vectors whose sum is closest to the observed aggregate coverage, where each structural configuration can be selected only once (an assumption made for the sake of clarity; in practice, Aldy allows selecting the same configurations multiple times). As there might be many such sets, Aldy only looks for the most parsimonious solution: a solution that selects the minimal number of such vectors. This problem, previously dubbed as the copy number estimation problem (CNEP) (Numanagić et al. 2018), can be efficiently solved via integer linear programming (ILP) as follows.

Assume that a gene G is segmented into 2r regions. Let stand for the set of the available configuration vectors, where gi = [gi,1, …, gi,2r] and gi,j ∈ {0, 1} for any i and j. Let cn be the aggregate coverage vector observed from HTS data, and let us introduce a binary variable zi for each gi that indicates if gi is a part of the solution or not. The objective—minimization of difference between the observed aggregate coverage and predicted solution—can be modeled as follows:

Although this model performs well on WGS and targeted data (Numanagić et al. 2018), it is rather sensitive to deviations from the expected coverage distribution. It also cannot properly handle the cases in which the normalized aggregate coverage is not stable or uniform. For targeted panels with nonuniform coverage distributions, aggregate coverage can be “normalized” by dividing it by the coverage of the control sample if it is stable across different samples. Aldy does this automatically for known targeted panels. Thus, Aldy 4 improves the original CNEP formulation by introducing additional optimization terms. This is performed by modifying the original objective term and extending it with two additional terms, resulting in a three-term optimization objective.

The first term is the same as the original CNEP objective but focuses only on the regions associated with the pharmacogene (and not its pseudogene):

The second term of the objective function considers the interaction between the pharmacogene and the corresponding pseudogene region by considering the changes between their respective region coverage. For example, if the coverage of the exon 2 in CYP2D6 is three and in CYP2D7 is two, the resulting region coverage difference would be one. This difference can be further normalized (in this case, divided by three). Using normalized differences allows us to handle samples in which the observed aggregate coverage (cn) varies between the regions owing to various sequencing and alignment biases. Despite region-specific coverage variation, the relative abundances between the matching gene–pseudogene regions remain constant. This term can formally be expressed as

Here νj = max{cnj, cnj+r} + 1 is the normalization factor.

The final term of the objective function ensures that the ILP solver selects the most parsimonious solution:

μi is parsimony parameter (by default set to ). However, some unlikely configurations, such as left fusions, will have higher parsimony scores to reflect the observation that such configurations are rare (Sim et al. 2012).

Aldy 4's modified CNEP model uses an ILP solver to minimize sum of these three terms o1 + o2 + o3. These solutions are passed to the later steps that will decide the best overall solution.

Star-allele calling

Aldy now proceeds by assigning the exact star-allele identifier to each of the n structural configurations obtained in the previous step. As stated in Methods, a star-allele Si is defined as a tuple (gi, Ai), where and . The star-allele assignment problem can also be modeled through the ILP as follows.

Let us indicate the presence of star-allele Si with a binary variable ai. Our goal is to select a set of star-alleles S1, …, Sn such that (1) the set of the structural configurations that describes selected star-alleles is identical to the set of the structural configurations from the previous step, and (2) the difference between predicted and observed coverage for each variant m (denoted as cov(m)) is minimized. In other words, we want to minimize

Although conceptually simple, this model does not account for cases in which database definitions are incomplete or incorrect. To account for these cases, the model must be allowed to alter star-allele definitions if needed. Aldy thus introduces new binary variables pi,m and qi,m that indicate if a variant m is to be “removed” from the star-allele Si (while being present in the database definition Ai), or “added” to it (while being absent in Ai). Then it attempts to minimize the following expression for each variant m:

As ai, pi,m, and qi,m are all binary variables, their product can be expressed as a set of linear constraints.

The minimization objective can be expressed as

Parameters αi,m and βi,m are penalties for adding or removing the variant m from allele Si. Adding a variant is less common than missing a variant, so generally we use αi,m = 2 and βi,m = 1 for any i and m (Numanagić et al. 2018). Note that not all variants are the same: As functional (core) variants can fundamentally alter the behavior of a star-allele (and thus change its designation), Aldy disallows removing such variants from any star-allele and allows adding novel functional (core) variants to the allele if and only if no other assignment is possible. This is performed by setting the corresponding αi,m to a very large value. Note that novel core variants are added only if no other decision can be made.

The star-allele calling model also enforces other constraints: Each functional (core) variant must be expressed by at least one allele, and each structural configuration must be expressed by at least one allele compatible with it. Finally, Aldy performs two rounds of star-allele calling for improved accuracy. In the first round, Aldy only considers functional (core) variants and identifies all major (core) star-allele combinations that explain the present functional variants (Numanagić et al. 2018). Being restricted solely to core variants, this step alone often produces multiple candidate solutions. Thus, Aldy then uses the second round to refine the candidate calls from the first round and break the ties by considering the silent variants (subvariants) as well. It finally selects the star-allele with the best second-round objective score as the final call.

The formulation Aldy 4 uses for this step remains similar to the original model used in the older versions of Aldy. The single major difference is the change in the first (functional star-allele calling) round: Aldy 4 can now call star-alleles that contain novel functional (core) variants—a not uncommon event if a gene database is incomplete—if no other call can be made.

Read-based phasing

The above-described model essentially performs a variant of statistical phasing: It uses the database knowledge to select the most likely haplotypes that best explain the given observations from the data. Although performing well in practice (Numanagić et al. 2018), there are nevertheless cases when the aforementioned model produces multiple equally likely calls. It is also unable to assign a novel variant to a particular star-allele unambiguously. Finally, in sporadic cases, the above model can produce incorrect results. These challenges can be resolved with long reads that provide long-range phasing information. Aldy 4 newly incorporates the handling of long-range phasing information to the star-allele calling model as follows.

Suppose that there are z fragments R1, …, Rz, each fragment being defined by a set of variants that it spans: . Each sequenced fragment originated from a single star-allele and can thus be assigned to one of the star-alleles in the data set. This assignment can be controlled by introducing a binary variable fi,j that is set if and only if a fragment Rj is assigned to Si. Clearly, must be one for every Rj because each fragment originates from a single allele.

Ideally, we want to assign a Rj to Si only if such an assignment agrees with the star-allele sequence as much as possible. In other words, we want to minimize the number of disagreements between allele Si and fragment Rj. Thus, the total disagreement of an assignment can be expressed as follows:

where denotes the set of variants that are not present in read Rj but are spanned by it.

The total phasing error can be expressed as . This expression can be added to the objective function of the star-allele calling model. Although the expanded version of this expression contains quadratic terms, each quadratic term is a product of two binary variables and, as such, can be trivially linearized.

As a final remark, note that the number of binary variables in the phasing model is dependent on the total number of present reads and alleles. In some cases, it can exceed half a million variables, making the overall model very costly to solve. The model can be significantly improved by using a smaller random sample of fragments, where the size of the random sample depends on the number of present reads and alleles.

Limitations

Aldy uses ILP solvers to solve the presented models. Although ILP solving is NP-hard even when restricted to the models mentioned above (Numanagić et al. 2018), all these models are solvable in practice in less than a minute thanks to the state-of-the-art integer programming solvers used by Gurobi (https://www.gurobi.com/) or CBC (https://github.com/coin-or/Cbc/tree/releases/2.9.9) solvers.

In some rare instances, Aldy cannot unambiguously call star-alleles from short-read data sets owing to the read length limitations and lack of strand information. In these cases, Aldy will report all possible solutions. In some cases, this might be misleading; for example, a *68 + *4/*5 call can be reported as *68/*4 (where *5 stands for deletion allele). However, both calls are functionally identical and should be treated as equal (as is performed here). Aldy also makes heavy use of the existing star-allele databases to call star-alleles and fusion breakpoints. Although it can handle cases in which the database is incomplete or lacking, it can theoretically report incorrect results if a present allele is wildly divergent from any allele in the database.

Aldy 4's detection of structural configurations is highly dependent on the stability of coverage across different sequencing runs. Although this is not a significant issue for short-read WGS and targeted sequencing panels, the coverage might vary more than expected in PacBio samples. For this reason, Aldy 4 brings support for the exploration of a broader solution space when needed to account for potential noise.

Finally, note that Aldy 4 does not cover all existing pharmacogenes: Genes from the IGH and HLA regions, ABC gene families (e.g., ABCG2), and the UGT1/2 gene clusters are prominently not included. Although some genes, such as ABCG2, can be easily supported with a corresponding database file (something that is planned for the future releases), more complex clusters such as HLA or IGH require major changes to the core algorithm to account for challenges posed by those regions and are better left to the specialized tools such as ImmunoTyper-SR (Ford et al. 2022).

Software availability

Aldy 4 is available at GitHub (https://github.com/0xTCG/aldy) and also uploaded as Supplemental Code. The experimental procedure and results are available at GitHub (https://github.com/0xTCG/aldy/tree/master/paper) and are also uploaded as the Supplemental Notebook and Supplemental Experiments, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard Gibbs, Donna Muzny, and the rest of the Human Genome Sequencing Center at Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, Texas) for generating PGRNseq v.3 sequencing data. Q.Z. and I.N. were supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant (RGPIN-04973) and the Canada Research Chairs Program. A.H. and S.C.S. were supported by funding from the Intramural Research Programs of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). A.H. is also funded by the NCI-UMD Partnership Program.

Author contributions: A.H., S.C.S., and I.N. designed the study. N.G., J.H., and S.A.S. oversaw the generation of PacBio sequencing data. X.Q. and S.S. oversaw the generation of PGRNseq v.3 sequencing data. I.N. developed the software. A.H. and Q.Z. tested the software, designed the experimental procedure, and performed the experiments. A.H., Q.Z., and I.N. wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at https://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.277075.122.

Competing interest statement

S.C.S. and I.N. are listed as coinventors on the U.S. Patent App. 16/615,089. N.G. and J.H. are employees and shareholders of Pacific Biosciences.

References

- Berger E, Yorukoglu D, Zhang L, Nyquist SK, Shalek AK, Kellis M, Numanagić I, Berger B. 2020. Improved haplotype inference by exploiting long-range linking and allelic imbalance in RNA-seq datasets. Nat Commun 11: 4662. 10.1038/s41467-020-18320-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning BL, Tian X, Zhou Y, Browning SR. 2021. Fast two-stage phasing of large-scale sequence data. Am J Hum Genet 108: 1880–1890. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspar SM, Schneider T, Meienberg J, Matyas G. 2020. Added value of clinical sequencing: WGS-based profiling of pharmacogenes. Int J Mol Sci 21: 2308. 10.3390/ijms21072308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Shen F, Gonzaludo N, Malhotra A, Rogert C, Taft RJ, Bentley DR, Eberle MA. 2021. Cyrius: accurate CYP2D6 genotyping using whole-genome sequencing data. Pharmacogenomics J 21: 251–261. 10.1038/s41397-020-00205-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews KR, Gaedigk A, Dunnenberger HM, Steve Leeder J, Klein TE, Caudle KE, Haidar CE, Shen DD, Callaghan JT, Sadhasivam S, et al. 2014. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype and codeine therapy: 2014 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 95: 376–382. 10.1038/clpt.2013.254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Coster W, Weissensteiner MH, Sedlazeck FJ. 2021. Towards population-scale long-read sequencing. Nat Rev Genet 22: 572–587. 10.1038/s41576-021-00367-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge P, Bafna V, Bansal V. 2017. HapCUT2: robust and accurate haplotype assembly for diverse sequencing technologies. Genome Res 27: 801–812. 10.1101/gr.213462.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H, Liu X, Ramírez J, Choudhury N, Kubo M, Im HK, Konkashbaev A, Cox NJ, Ratain MJ, Nakamura Y, et al. 2014. Establishment of CYP2D6 reference samples by multiple validated genotyping platforms. Pharmacogenomics J 14: 564–572. 10.1038/tpj.2014.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford M, Haghshenas E, Watson CT, Sahinalp SC. 2020. Genotyping and copy number analysis of immunoglobin heavy chain variable genes using long reads. iScience 23: 100883. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.100883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford M, Hari A, Rodriguez O, Xu J, Lack J, Oguz C, Zhang Y, Weber S, Magliocco M, Barnett J, et al. 2022. ImmunoTyper-SR: a novel computational approach for genotyping immunoglobulin heavy chain variable genes using short read data. In International Conference on Research in Computational Molecular Biology, San Diego, pp. 382–384. Springer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaedigk A, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Miller NA, Steven Leeder J, Whirl-Carrillo M, Klein TE, PharmVar Steering Committee. 2018. The Pharmacogene Variation (PharmVar) Consortium: incorporation of the human cytochrome P450 (CYP) allele nomenclature database. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103: 399–401. 10.1002/cpt.910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaedigk A, Turner A, Everts RE, Scott SA, Aggarwal P, Broeckel U, McMillin GA, Melis R, Boone EC, Pratt VM, et al. 2019. Characterization of reference materials for genetic testing of CYP2D6 alleles: a GeT-RM collaborative project. J Mol Diagn 21: 1034–1052. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2019.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaedigk A, Boone EC, Scherer SE, Lee S-B, Numanagić I, Sahinalp C, Smith JD, Smith JD, McGee S, Radhakrishnan A, et al. 2022. CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19 characterization using next-generation sequencing and haplotype analysis: a GeT-RM collaborative project. J Mol Diagn 24: 337–350. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2021.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AS, Fulton RS, Qin X, Mardis ER, Nickerson DA, Scherer S. 2016. PGRNseq: a targeted capture sequencing panel for pharmacogenetic research and implementation. Pharmacogenet Genomics 26: 161–168. 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara K, Edmonson MN, Wheeler DA, Zhang J. 2022. indelPost: harmonizing ambiguities in simple and complex indel alignments. Bioinformatics 38: 549–551. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg MA, Collins FS. 2010. The path to personalized medicine. N Engl J Med 363: 301–304. 10.1056/NEJMp1006304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hon T, Mars K, Young G, Tsai Y-C, Karalius JW, Landolin JM, Maurer N, Kudrna D, Hardigan MA, Steiner CC, et al. 2020. Highly accurate long-read HiFi sequencing data for five complex genomes. Sci Data 7: 399. 10.1038/s41597-020-00743-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelman-Sundberg M. 2005. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and functional diversity. Pharmacogenomics J 5: 6–13. 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingan S, Harting J, Hon T, Tsai YC, McLaughlin I, Ziegle J, Han T, Arbiza L, Kloet S, Busscher L, et al. 2022. Poster: enablement of long-read targeted sequencing panels using twist hybrid capture and PacBio HiFi sequencing. In ESHG 2022, Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer WE, Walker DL, O'Kane DJ, Mrazek DA, Fisher PK, Dukek BA, Bruflat JK, Black JL. 2009. CYP2D6: novel genomic structures and alleles. Pharmacogenet Genomics 19: 813–822. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283317b95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S-b, Wheeler MM, Patterson K, McGee S, Dalton R, Woodahl EL, Gaedigk A, Thummel KE, Nickerson DA. 2019. Stargazer: a software tool for calling star alleles from next-generation sequencing data using CYP2D6 as a model. Genet Med 21: 361–372. 10.1038/s41436-018-0054-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 2014. Toward better understanding of artifacts in variant calling from high-coverage samples. Bioinformatics 30: 2843–2851. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 2018. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34: 3094–3100. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/MAP format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh P-R, Palamara PF, Price AL. 2016. Fast and accurate long-range phasing in a UK Biobank cohort. Nat Genet 48: 811–816. 10.1038/ng.3571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly RC, Shugg T, Ratcliff R, Osei W, Lynnes TC, Pratt VM, Schneider BP, Radovich M, Bray SM, Salisbury BA, et al. 2022. Analytical validation of a computational method for pharmacogenetic genotyping from clinical whole exome sequencing. J Mol Diagn 24: 576–585. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2022.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, et al. 2010. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 20: 1297–1303. 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numanagić I, Malikić S, Pratt VM, Skaar TC, Flockhart DA, Sahinalp SC. 2015. Cypiripi: exact genotyping of CYP2D6 using high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31: i27–i34. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numanagić I, Malikić S, Ford M, Qin X, Toji L, Radovich M, Skaar TC, Pratt VM, Berger B, Scherer S, et al. 2018. Allelic decomposition and exact genotyping of highly polymorphic and structurally variant genes. Nat Commun 9: 828. 10.1038/s41467-018-03273-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poplin R, Ruano-Rubio V, DePristo MA, Fennell TJ, Carneiro MO, Van der Auwera GA, Kling DE, Gauthier LD, Levy-Moonshine A, Roazen D, et al. 2017. Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples. bioRxiv 10.1101/201178 [DOI]

- Portik D, Hon T, Wilcots J, Gonzaludo N, Yang Y, Hammond NA, Kronenberg Z, Watson N, Harting J, Ashley E, et al. 2021. Abstract: development and optimization of a 43 gene pharmacogenomic panel using enrichment-based capture and PacBio HiFi sequencing. In ASHG 2021 Virtual Conference. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt VM, Zehnbauer B, Wilson JA, Baak R, Babic N, Bettinotti M, Buller A, Butz K, Campbell M, Civalier C, et al. 2010. Characterization of 107 genomic DNA reference materials for CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, VKORC1, and UGT1A1: a GeT-RM and association for molecular pathology collaborative project. J Mol Diagn 12: 835–846. 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.100090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt VM, Everts RE, Aggarwal P, Beyer BN, Broeckel U, Epstein-Baak R, Hujsak P, Kornreich R, Liao J, Lorier R, et al. 2016. Characterization of 137 genomic DNA reference materials for 28 pharmacogenetic genes: a GeT-RM collaborative project. J Mol Diagn 18: 109–123. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2015.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relling MV, Evans WE. 2015. Pharmacogenomics in the clinic. Nature 526: 343–350. 10.1038/nature15817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robarge JD, Li L, Desta Z, Nguyen A, Flockhart DA. 2007. The star-allele nomenclature: retooling for translational genomics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 82: 244–248. 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 29: 24–26. 10.1038/nbt.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangkuhl K, Whirl-Carrillo M, Whaley RM, Woon M, Lavertu A, Altman RB, Carter L, Verma A, Ritchie MD, Klein TE. 2020. Pharmacogenomics Clinical Annotation Tool (PharmCAT). Clin Pharmacol Ther 107: 203–210. 10.1002/cpt.1568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SA, Scott ER, Seki Y, Chen AJ, Wallsten R, Obeng AO, Botton MR, Cody N, Shi H, Zhao G, et al. 2021. Development and analytical validation of a 29 gene clinical pharmacogenetic genotyping panel: multi-ethnic allele and copy number variant detection. Clin Transl Sci 14: 204–213. 10.1111/cts.12844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sezutsu H, Le Goff G, Feyereisen R. 2013. Origins of P450 diversity. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 368: 20120428. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shajii A, Numanagic I, Berger B. 2018. Latent variable model for aligning barcoded short-reads improves downstream analyses. In RECOMB, Paris, pp. 280–282. Springer. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim SC, Daly AK, Gaedigk A. 2012. CYP2D6 update: revised nomenclature for CYP2D7/2D6 hybrid genes. Pharmacogenet Genomics 22: 692–694. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283546d3c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twesigomwe D, Wright GE, Drögemöller BI, da Rocha J, Lombard Z, Hazelhurst S. 2020. A systematic comparison of pharmacogene star allele calling bioinformatics algorithms: a focus on CYP2D6 genotyping. NPJ Genom Med 5: 30. 10.1038/s41525-020-0135-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twesigomwe D, Drögemöller BI, Wright GE, Siddiqui A, da Rocha J, Lombard Z, Hazelhurst S. 2021. StellarPGx: a Nextflow pipeline for calling star alleles in cytochrome P450 genes. Clin Pharmacol Ther 110: 741–749. 10.1002/cpt.2173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twist GP, Gaedigk A, Miller NA, Farrow EG, Willig LK, Dinwiddie DL, Petrikin JE, Soden SE, Herd S, Gibson M, et al. 2016. Constellation: a tool for rapid, automated phenotype assignment of a highly polymorphic pharmacogene, CYP2D6, from whole-genome sequences. NPJ Genom Med 1: 15007. 10.1038/npjgenmed.2015.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, Jordan T, Shakir K, Roazen D, Thibault J, et al. 2013. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 43: 11.10.1–11.10.33. 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshilboum RM, Wang L. 2017. Pharmacogenomics: precision medicine and drug response. Mayo Clin Proc 92: 1711–1722. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.