Abstract

Background and Objectives

Procedural practice by paediatricians in Canada is evolving. Little empirical information is available on the procedural competencies required of general paediatricians. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to conduct a needs assessment of Canadian general paediatricians to identify procedural skills required for practice, with the goal of informing post-graduate and continuing medical education.

Methods

A survey was sent to paediatricians through the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program (CPSP) (www.cpsp.cps.ca/surveillance). In addition to demographic information about practice type and location, participants were asked to indicate the frequency with which they performed each of 32 pre-selected procedures and whether each procedure was considered essential to their practice.

Results

The survey response rate was 33.2% (938/2,822). Data from participants who primarily practice general paediatrics were analyzed (n=481). Of these, 71.0% reported performing procedures. The most frequently performed procedures were: bag-valve-mask ventilation of an infant, lumbar puncture, and ear curettage, being performed monthly by 40.8%, 34.1%, and 27.7% of paediatricians, respectively. The procedures performed by most paediatricians were also those found most essential to practice, with a few exceptions. Respondents performed infant airway procedures with greater frequency and rated them more essential when compared to the same skill performed on children. We found a negative correlation between procedures being performed and difficulty maintaining proficiency in a skill.

Conclusions

This report of experiences from Canadian general paediatricians suggests a wide variability in the frequency of procedural performance. It helps establish priorities for post-graduate and continuing professional medical education curricula in the era of competency-based medical education.

Keywords: Educational needs, Graduate medical education, Paediatric, Procedural skills assessment

Procedures performed by paediatricians are an important aspect of patient care. The scope of procedural practice seems to be evolving; the changing epidemiology of paediatric illness and interventions (1–5), availability of non- or minimally invasive technologies (6,7), variation in practice type and location (8–10), and the expanding scope of multi-professional providers (11,12) may all contribute to changes in procedural skill needs for Canadian paediatricians.

Procedural skills have been identified internationally as an area of weakness in medical education (13,14). Residents have been shown to have difficulty with these skills, and often perform them incorrectly (15–17), including both skills that are commonly performed and those which, although performed rarely, are potentially life-saving.

A robust needs assessment is necessary to target curriculum development for procedural skills training (18). Therefore, understanding the skills required by general paediatricians is vital for planning and allocating educational resources for both current and future paediatricians. There is little empirical information available on the procedural competencies required of general paediatricians. A study from the USA in 1986 identified a list of 49 essential procedures based on survey responses of 173 practicing paediatricians (19), with no similar published practice assessment in North America since, to our knowledge.

Establishing a core set of procedural competencies is important because graduates from Canadian training programs are expected to be able to practice in any one of a variety of settings across the country. The most recent list of procedures guiding Canadian paediatric post-graduate medical education programs referenced in the 2008 Objectives of Training (OTR) issued by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) (20) is limited by being opinion-based, and may not reflect the changing landscape of paediatric practice. The incoming competency-based medical education structure also provides an opportunity for procedural training to be updated and provide paediatricians the skills required to meet the needs of Canadian children.

Accordingly, the aim of this study was to conduct a comprehensive needs assessment based on input from Canadian general paediatricians to identify the procedural skills required for independent practice, with the goal of informing post-graduate and continuing medical education. Our specific objectives were: (1) to explore which procedures are considered essential for independent general paediatric practice in Canada and (2) to describe the frequency with which paediatricians perform these procedures.

METHODS

Study design

This was a cross-sectional observational survey study of a national sample of practicing Canadian paediatricians.

Survey development

We developed and conducted a one-time survey in partnership with the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program (CPSP). The CPSP is a collaboration of the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Paediatric Society that conducts national paediatric surveillance and epidemiological studies, which allows data to be collected from over 2,800 paediatricians and paediatric subspecialists across Canada.

The initial survey draft was developed based on available literature and the 2008 OTR for paediatrics, with input from an education researcher with survey methodology expertise. The survey was then reviewed by the CPSP Scientific Steering Committee, whose membership includes general and subspecialty paediatric providers as well as public health professionals with perspectives that range from rural to urban. This feedback informed further revision by the research group, with members having experience both in general paediatrics and post-graduate education. The survey was then piloted by a small group of general paediatricians with various backgrounds to ensure clarity and ease of survey completion.

The final survey consisted of demographic questions followed by a table containing 32 procedural skills of interest (see www.cpsp.cps.ca/uploads/surveys/Procedural-skill-needs-for-Canadian-paediatricians-Survey.pdf). Demographics included information on practice setting, type, location, years in independent practice, and whether their practice involved performing and/or supervising procedures. Respondents who indicated procedures were not part of their practice were not asked to complete the procedure table. For each of the 32 procedures, participants were asked to indicate the frequency of performance (monthly, yearly, rarely, or never). For each procedure, participants were also asked whether they considered it essential to their practice to be able to perform the skill independently, and whether they considered it difficult to maintain proficiency.

Survey administration and data collection

Web- and paper-based versions of the survey, both in French and English, were distributed via the CPSP. Surveys were sent to 2,822 Canadian paediatricians in March 2018, with two online reminders. Web responses were collected by the CPSP and directly entered into a secure database. Paper responses were manually added into the existing database and individually verified for accuracy. Surveys with fewer than 50% of questions answered were considered incomplete and not included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and procedure table data were summarized descriptively and valid percentages calculated where appropriate. Only data from participants reporting more than 50% of their clinical work spent in general paediatrics practice (n= 481) were included for final analysis. This was done to increase focus on general paediatrics practice, and reduce the influence from those that either mostly or entirely perform subspecialty practice. Correlation and chi-squared analyses (or Fisher’s exact test) were used for sub-group comparisons of categorical variables. A P-value of <0.05 was considered as significant.

Permission/ethics

The CPSP routinely administers one-time surveys to their potential respondent pool whom knowingly complete surveys on a voluntary basis for surveillance purposes. Given this, formal research ethics board approval was not pursued in this instance as neither patient nor personal health data was being collected. The final version of the survey was reviewed by the CPSP Scientific Steering Committee prior to distribution. Finally, to maintain anonymity, survey distribution and data collection were performed solely by the CPSP, and the final dataset was transmitted to the research team anonymized by source.

RESULTS

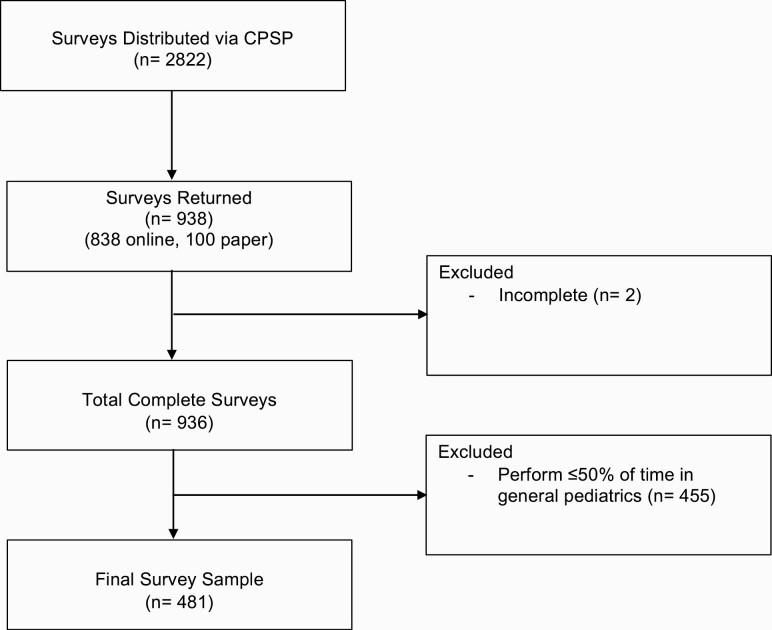

A total of 938/2822 (33.2%) surveys were returned to the CPSP (838 electronic and 100 paper). The steps taken to compile the final dataset are shown in Figure 1. The demographic and practice information of the 481 analyzed respondents are shown in Supplementary Appendix 1. All provinces and territories were represented and response frequency generally reflected provincial population. Most participants (n=423/481, 88.1%) completed their paediatric residency training within Canada, and 93.8% (n=451/481) of participants indicated they spent >75% of their clinical time in general paediatrics. Within the group, 226 paediatricians (47.0%) reported working in a single practice type, with community office practice and tertiary care being the most common settings. The remaining respondents (n=255/481, 53.0%) indicated that they worked in multiple settings. The number of participants that predominantly practiced within 50 km or greater than 100 km from a tertiary care facility were n=305/457, 66.7% and n=107/457, 23.4%, respectively. The majority (n=346/481, 71.9%) of participants indicated their practice involved performing and/or supervising procedures.

Figure 1.

Study profile.

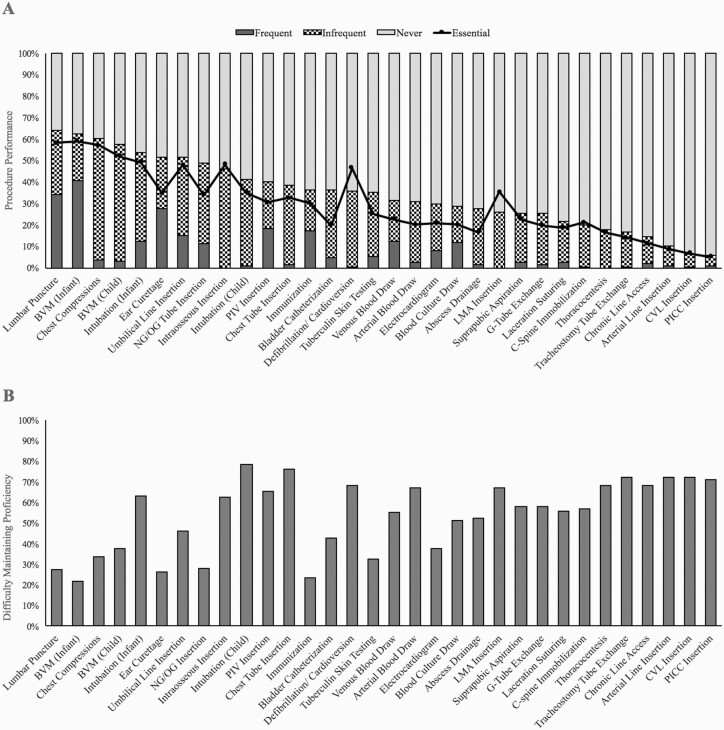

Results for procedure frequency and perceived essentialness are shown in Figure 2A. It was decided a priori that ‘frequent’ procedures would be those performed monthly, ‘infrequent’ if they were performed yearly or rarely, and ‘not performed’ if they were never performed or if the respondent indicated that they do not perform procedures at the outset of the survey. The most frequently performed procedures were: bag-valve-mask ventilation of an infant (BVM-I), lumbar puncture, and ear curettage, reported as being performed monthly by 40.8% (n=196/481), 34.1% (n=164/481), and 27.7% (n=133/481) of paediatricians, respectively. The procedures most commonly reported as not being performed were: peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) insertion, central venous line (CVL) insertion (jugular/femoral), and peripheral arterial line insertion (94.0% [n=452/481], 93.6% [n=450/481], and 89.8% [n=432/481] of paediatricians, respectively). Procedures most commonly reported to be infrequently performed (‘yearly’ or ‘rarely’) were chest compressions (n=271/481, 56.3%), BVM of a child (BVM-C; n=262/481, 54.5%), and intraosseous (IO) line insertion (n=221/481, 46.0%).

Figure 2.

Procedural skill data. (A) Performance frequency and essentiality by percentage of respondents. (B) Difficulty in maintenance of proficiency by percentage of respondents. Procedures listed in descending order of percentage performed. BVM Bag-valve-mask ventilation; C-spine Cervical spine; CVL Central venous line; G-tube Gastrostomy tube; LMA Laryngeal mask airway insertion; NG/OG Nasogastric tube/orogastric tube; PICC Peripherally inserted central catheter; PIV Peripheral intravenous line.

In general, the frequency and essentiality data appeared to trend together, with those procedures performed frequently being the procedures also rated as essential, as seen in Figure 2B. Generally, for each individual procedure, a higher percentage of paediatricians performed it than deemed it as essential to practice. However, there were three procedures that deviated from this pattern, being considered essential by many but performed by few. These were defibrillation/cardioversion, laryngeal mask airway (LMA), and IO insertion, which are seen as peaks in the trend line in Figure 2A.

The procedure list differentiated two key procedures (BVM and intubation) based on age: infants (age < 2 years) or children (age ≥ 2 years), as defined in the survey table. Data for this comparison are shown in Supplementary Appendix 2. Results indicate that paediatricians are significantly more likely both to perform and rate as essential those procedures performed on infants.

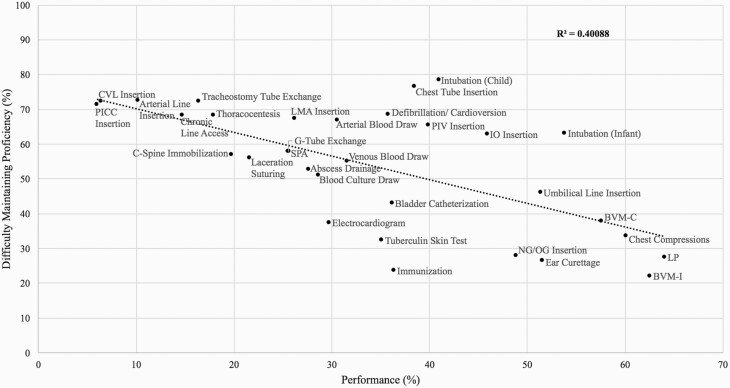

Data on maintenance of proficiency are represented in Figures 2B and 3. The procedures that respondents reported the most difficulty maintaining proficiency in were: intubation of a child, insertion of a chest tube, and insertion of an arterial line (78.3% [n=235/300], 76.5% [n=221/289], and 72.4% [n=205/283] of paediatricians, respectively). Maintaining proficiency was least difficult for BVM-I, immunization, and ear curettage (22.0% [n =68/309], 23.5% [n=69/293], and 26.5% [n=79/298] of paediatricians, respectively). Difficulty maintaining proficiency in a skill was negatively correlated with the percentage of paediatricians performing the skill, with a coefficient of determination (R2) equal to 0.4, indicating only a modest correlation (Figure 3). This is also demonstrated in Figure 2B, where difficulty maintaining proficiency appeared to be higher for procedures that are performed by fewer respondents, with several outliers such as intubation, chest tube insertion, IO insertion, and immunization.

Figure 3.

Percentage of respondents performing a procedural skill as part of their practice vs their perceived ability to maintain proficiency in that skill. Linear regression analysis represented with coefficient of determination (R2). BVM-I Bag-valve-mask ventilation of infant; BVM-C Bag-valve-mask ventilation of child; C-spine Cervical spine; CVL Central venous line; G-tube Gastrostomy tube; IO Intraosseous line; LMA Laryngeal mask airway insertion; LP Lumbar puncture; NG/OG Nasogastric tube/orogastric tube; PICC Peripherally inserted central catheter; PIV Peripheral intravenous line; SPA Suprapubic aspiration.

DISCUSSION

To inform educational planning at the post-graduate and professional development levels, particularly as paediatrics undergoes a significant curriculum change to competency-based medical education, we performed a needs assessment of procedural skill practice of general paediatricians in Canada. The survey results provide insights into frequency and necessity of procedural practice for Canadian paediatricians.

The results suggest that several procedures are performed routinely by many general paediatricians. Post-graduate programs should ensure that their graduates are competent to perform these high frequency procedures independently. Examples include: lumbar puncture, BVM of an infant, ear curettage, and peripheral intravenous line insertion. Some procedures were rarely performed and would likely not justify the educational resource investment to train all paediatric graduates to proficiency. Those intending to practice in specific contexts requiring such procedures could consider additional training through specialized fellowship or continuing medical education efforts. Examples include: central line insertion (jugular/femoral), peripheral arterial line insertion, and PICC insertion. While the post-graduate training implications of procedures with high or low frequency of performance may be clear, those that fall in the middle may require further analyses and discussion among post-graduate educators.

The proportion of respondents considering a procedure to be essential to independent practice was similar to performance frequency data. There were, however, procedures that were discrepant, in that they were reported by participants to be essential to independent practice but, by many, were never performed. Examples of such procedures include: defibrillation/cardioversion, LMA insertion, and IO insertion. Given that these procedures may be necessary for successful resuscitation of critically ill children prior to reaching subspecialty care, they likely require both initial post-graduate and ongoing continuing medical training.

Interpretation of the implications for continuing professional development requires an even more thoughtful approach. Our study found a negative, albeit modest, correlation between performance of, and difficulty maintaining proficiency in, a particular skill, suggesting performance is not the only factor in ongoing perception of proficiency. Procedural skill maintenance is likely complex, and may also be influenced by: technical difficulty, cognitive/psychomotor skill retention, practice type and setting, and availability of alternate support personnel (e.g., anesthesiologist). Frequently performed procedures, such as lumbar puncture, likely require little to no continuing professional education as it is expected that routine clinical exposure should suffice; however, it could also be argued that frequently performed procedures should receive some attention for ensuring maintenance of competency. Procedures not performed frequently, however, especially those considered highly essential, may represent key areas to invest continuing professional education resources for practicing paediatricians. Exploring currently used or preferred methods of continuing professional education were beyond the scope of our survey, but interactive, hands-on techniques (e.g., videos, simulations) seem most amenable.

Our results also suggest that while many consider procedures in children as essential, procedures on infants may be even more critical. This may be because alternate providers (e.g., emergency physicians), when available, may have a greater involvement and confidence in the care of older children, while much of the acute care of infants may rest solely with paediatricians. To avoid making the survey excessively lengthy, only two procedures, intubation and BVM, were specifically differentiated by age. While these findings may not necessarily be extrapolated to other procedures, it does contend that a focus on ensuring proficiency of certain procedures on infants is crucial.

The survey results are highly heterogeneous and reflect the broad spectrum of paediatric practice that exists in the country. For example, while most respondents engaged in the use of procedural skills and considered them essential, approximately 30% of responding general paediatricians indicated that they performed no procedures whatsoever. Although practice location and context are likely factors in procedural skill needs, given that there exists a single certification process for paediatricians who then work in highly varied practice settings, a general procedural skill set should be agreed upon. Further tailoring of procedural skill training or requirements based on practice context is a topic worthy of future discussion.

This study is the largest of its kind, producing a comprehensive profile of current procedural skill practices of paediatricians across the country. It is one of two published studies gathering information from practitioners, and not educators, to guide paediatric procedural skills education. Despite being the largest sample size and acquiring data directly from front-line general paediatricians, our study does have limitations. Survey results were based on self-reported frequency data and as such, are subject to recall bias. The survey also required individual interpretation of concepts such as ‘essential’ and ‘proficiency’ introducing a degree of subjectivity. Given that the survey included only voluntary members of the CPSP, there may be an element of selection bias. Despite wide ranging representation of paediatricians and practice type, our response rate was 33.2%, which may indicate a bias towards those who were interested in the study and/or performed procedures.

The results of this study should help certification and licensing bodies define a contemporary set of procedural skills that are core to general paediatrics. In turn, this will aid post-graduate and continuing medical educators in curriculum development. Future research should focus on the effects of practice factors (e.g., type/setting, distance to tertiary care, years in practice, available supports) on procedural practice patterns to further target educational efforts at both the post-graduate and continuing medical education levels. It would also be important to identify paediatricians who engage in supervising procedures, to better understand how these roles affect their own procedural skill needs and maintenance of proficiency.

We administered a national survey to conduct a comprehensive needs assessment of procedural skills for Canadian general paediatricians. The results provide contemporary insight into performance frequency, professional opinion on essentiality to paediatric practice, and challenges in maintenance of proficiency. This data will substantially assist in informing the core set of procedural skills required by general paediatricians in Canada.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The study team would like to thank Dr. Tim Wood from the Department of Innovation for Medical Education at the University of Ottawa for assisting in survey development, Dr. Zia Bismilla at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto for providing content expertise, and the CPSP for providing the platform to conduct this study. An abstract of this study was presented in oral format at the Canadian Paediatric Society 96th Annual Conference in Toronto, Canada: https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxz066.158. A non-peer-reviewed summary of the survey was published in the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program 2018 Results document: https://www.cpsp.cps.ca/uploads/publications/CPSPResults2018.pdf

Contributor Information

Jessica White, Department of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Anne Rowan-Legg, Department of Pediatrics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario.

Hilary Writer, Department of Pediatrics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario.

Rahul Chanchlani, Department of Pediatrics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario; Department of Health Services Research, Evidence and Impact, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario.

Ronish Gupta, Department of Pediatrics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario; School of Education, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Funding: The investigators were awarded an in-kind grant from the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program to conduct a one-time survey.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: RG reports personal fees from Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, outside the submitted work. There are no other disclosures. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Author contributions: JW conceptualized and designed the study, facilitated data acquisition and analysis, and drafted as well as revised the manuscript. RG conceptualized and designed the study, carried out initial data analyses, and critically reviewed the manuscript. AR-L and HW contributed to study design, data analysis, and critically reviewed the manuscript. RC contributed to data analysis, data interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1. Olfson M, Druss BG, Marcus SC. Trends in mental health care among children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2015;372(21):2029–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berry JG, Hall M, Hall DEet al. Inpatient growth and resource use in 28 children’s hospitals: A longitudinal, multi-institutional study. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167(2):170–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McDougall CM, Adderley RJ, Wensley DF, Seear MD. Long-term ventilation in children: Longitudinal trends and outcomes. Arch Dis Child 2013;98(9):660–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Trey L, Niedermann E, Ghelfi D, Gerber A, Gysin C. Pediatric tracheotomy: A 30-year experience. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48(7):1470–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fox D, Campagna EJ, Friedlander J, Partrick DA, Rees DI, Kempe A. National trends and outcomes of pediatric gastrostomy tube placement. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;59(5):582–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gibson C, Connolly BL, Moineddin R, Mahant S, Filipescu D, Amaral JG. Peripherally inserted central catheters: Use at a tertiary care pediatric center. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24(9):1323–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ganu SS, Gautam A, Wilkins B, Egan J. Increase in use of non-invasive ventilation for infants with severe bronchiolitis is associated with decline in intubation rates over a decade. Intensive Care Med 2012;38(7):1177–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mihalicz D, Phillips L, Bratu I. Urban vs rural pediatric trauma in Alberta: Where can we focus on prevention? J Pediatr Surg 2010;45(5):908–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim K, Ozegovic D, Voaklander DC. Differences in incidence of injury between rural and urban children in Canada and the USA: A systematic review. Inj Prev 2012;18(4):264–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stewart TC, Gilliland J, Fraser DD. An epidemiologic profile of pediatric concussions: Identifying urban and rural differences. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014;76(3):736–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chopra V, Kuhn L, Ratz Det al. Vascular access specialist training, experience, and practice in the United States: Results from the National PICC1 Survey. J Infus Nurs 2017;40(1):15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kawaguchi A, Nielsen CC, Saunders LD, Yasui Y, de Caen A. Impact of physician-less pediatric critical care transport: Making a decision on team composition. J Crit Care 2018;45:209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gaies MG, Landrigan CP, Hafler JP, Sandora TJ. Assessing procedural skills training in pediatric residency programs. Pediatrics 2007;120(4):715–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Wylde K, Cameron HS. Are medical graduates ready to face the challenges of Foundation training? Postgrad Med J 2011;87(1031):590–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buss PW, McCabe M, Evans RJ, Davies A, Jenkins H. A survey of basic resuscitation knowledge among resident paediatricians. Arch Dis Child 1993;68(1):75–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Falck AJ, Escobedo MB, Baillargeon JG, Villard LG, Gunkel JH. Proficiency of pediatric residents in performing neonatal endotracheal intubation. Pediatrics 2003;112(6 Pt 1):1242–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. White JR, Shugerman R, Brownlee C, Quan L. Performance of advanced resuscitation skills by pediatric housestaff. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998;152(12):1232–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kern DE. Overview: A Six-Step Approach to Curriculum Development. In: Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT, eds. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six Step Approach, 2nd edn. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. p. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oliver TK Jr, Butzin DW, Guerin RO, Brownlee RC. Technical skills required in general pediatric practice. Pediatrics 1991;88(4):670–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Objectives of Training in Pediatrics [Internet]. 2008. [cited November 3, 2019]. 1–32. <www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/documents/ibd/pediatrics_otr_e.pdf> (Accessed September 22, 2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.