Abstract

Objective(s)

To assess laryngologic symptomatology following severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and determine whether symptom severity correlates with disease severity.

Methods

Single-institution survey study in participants with documented SARS-CoV-2 infection between March 2020 and February 2021. Data acquired included demographic, infection severity characteristics, comorbidities, and current upper aerodigestive symptoms via validated patient reported outcome measures. Primary outcomes of interest were scores of symptom severity questionnaires. Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) severity was defined by hospitalization status. Descriptive subgroup analyses were performed to investigate differences in demographics, comorbidities, and symptom severity in hospitalized participants stratified by ICU status. Multivariate logistical regression was used to evaluate significant differences in symptom severity scores by hospitalization status.

Results

Surveys were distributed to 5300 individuals with upper respiratory infections. Ultimately, 470 participants with COVID-19 were included where 352 were hospitalized and 118 were not hospitalized. Those not hospitalized were younger (45.87 vs. 56.28 years), more likely female (74.17 vs. 58.92%), and less likely white (44.17 vs. 52.41%). Severity of dysphonia, dyspnea, cough, and dysphagia was significantly worse in hospitalized patients overall and remained worse at all time points. Cough severity paradoxically worsened in hospitalized respondents over time. Dyspnea scores remained abnormally elevated in respondents even 12 months after resolution of infection.

Conclusions

Results indicate that laryngologic symptoms are expected to be worse in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Dyspnea and cough symptoms can be expected to persist or even worsen by 1-year post infection in those who were hospitalized. Dysphagia and dysphonia symptoms were mild. Nonhospitalized participants tended to have minimal residual symptoms by 1 year after infection.

Keywords: COVID-19, long COVID, dysphagia, dysphonia, SARS-CoV-2

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has remained an ongoing public health crisis since it was first declared a public health emergency of international concern on January 30, 2020.1 Clinical manifestations of infection vary among patients, but commonly include fever, fatigue, and cough.2 Less frequently sputum production, headache, hemoptysis, and diarrhea are reported.2

Laryngologic complications of COVID-19 have been observed and described, including voice changes, cough, dyspnea, and intubation-related injuries. What is now more clinically evident is longstanding manifestations of infection. A recent review of symptoms following COVID-19 infection revealed 32.6%–87.4% of infected patients reported one or more persistent symptom, with fatigue and dyspnea listed as most common.3 New research from October 2022 studied over 33,000 patients with COVID-19 and reported that 42% of them had not fully recovered to preinfection symptom baseline.4 That study used serial patient questionnaires and found breathlessness, chest pain, palpitations and confusion were the most reported long-lasting COVID-19 symptoms.

The goal of the current investigation was to determine the prevalence and severity of specific laryngologic and upper aerodigestive symptoms in participants following COVID-19 infection, with particular attention to differences between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. We aimed to contribute to the evolving evidence regarding long-term clinical manifestations of COVID-19 with the goal of improving patient management and counseling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This single institution, cross-sectional survey study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board (STUDY00001054). All individuals who had contracted the novel SARS-CoV2 virus were eligible to participate regardless of hospitalization status or disease severity. Documented COVID-19 positive patients between March 2020 and Feb 2021 were identified via an Emory Healthcare patient database called Clinical Data Warehouse. The Clinical Data Warehouse is a repository that integrates data within Emory Healthcare including patient billing and collections, general ledger and budget information, patient visit data, provider information, diagnoses and procedures, clinical laboratory results, clinician documentation, pharmacy, and emergency department utilization and details.

Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 identified via the database were contacted via email to request their participation using a HIPAA-compliant Research Electronic Database Capture (REDCap) survey.5 Surveys were distributed in May 2021. The included surveys were all completed between May 2021 to August 2021. The survey questions included self-reported comorbidities, smoking status, self-reported hospitalization status, quality of life post-infection questions, and responses on patient-reported quality of life and disease-severity questionnaires specific to laryngologic and upper aero-digestive symptoms. These validated symptom severity instruments included voice handicap index-10 (VHI-10), dyspnea index (DI), cough severity index (CSI), and eating assessment tool-10 (EAT-10).6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Of note, higher scores represent more severe symptoms where abnormal scores for each questionnaire are defined as the following: VHI-10 > 11, DI > 10, CSI > 3.23, and EAT-10 ≥ 3.6 , 9 , 11 , 12

Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4 software (SAS, Cary, NC). The primary outcomes of interest were total scores of the symptom severity questionnaires. Univariate analysis was performed to evaluate the normality of the data. Student's t and chi-squared tests were utilized to assess differences between demographics and disease severity status stratified by hospitalization status. Multivariate linear regression models were built to identify various participant characteristics, hospitalization status and time since infection associated with individual participant scores. Logistic regression was used to evaluate if the comorbidities differed for hospitalized, ICU and intubated participants.

RESULTS

Surveys were distributed to 5300 individuals diagnosed with upper respiratory infections including COVID-19 and influenza. Given the small number of participants with influenza (n = 6), a comparative analysis was not performed. Inclusion for analysis required reported diagnosis of COVID-19 and completion of at least one symptom severity questionnaire. Five hundred and twenty-seven signed the consent and began the survey; 57 participants were excluded for lack of survey completion. Remaining 470 participants (81% completion rate) were then stratified based on hospitalization admission status, which was used as a surrogate marker for infection severity. A consort diagram representing exclusions and final participation is represented in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

Subject acquisition, exclusion, and selection.

Significant differences among demographic variables and hospitalization status are depicted in Table 1. Those not hospitalized tended to be younger (45.9 vs. 56.3 years; P ≤ 0.001), more likely female (74.2 vs. 58.9%; P = 0.003), and less likely white (44.2 vs. 52.4%). Overall nonsmoking status was similar between both groups (80.0 vs. 82.2%). Comorbidities varied between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients as seen in Table 2 . Of the patients hospitalized, 77.27% stated they required supplemental O2, 31.53% (111) were admitted to the intensive care unit and 11.93% (42) required intubation and mechanical ventilation. There was no statistically significant difference in the comorbidities between hospitalized, ICU and intubated participants except pulmonary diagnosis, which was greater in the intubated group (P-value = 0.03) (Table 3 ). Subgroup analysis of symptom severity scores was performed in hospitalized participants stratified by disease severity, which was defined as hospitalized but non-ICU admitted, ICU admitted but not intubated, and ICU admitted and intubated. All mean symptom severity scores were highest in those participants who reported being intubated during their ICU stay (Table 4 ). The largest differences were in DI, CSI, and VHI-10. VHI-10 scores were below the accepted abnormal threshold (<11) in all groups. Participants who were not intubated, regardless of ICU status, had overall very similar symptom severity scores.

TABLE 1.

Demographics Stratified by Hospitalization Status

| Not Hospitalized (N = 118) | Hospitalized (n = 352) | P-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 45.87 (14.72) | 56.28 (18.35) | <0.0001 |

| Gender (%) | 0.0028 | ||

| Male | 25.83% | 41.08% | |

| Female | 74.17% | 58.92% | |

| Race (%) | 0.07 | ||

| Black or African American | 47.5% | 39.02% | |

| White | 44.17% | 52.41% | |

| More than one race | 5.83% | 2.55% | |

| Unknown/ not reported | 2.50% | 1.42% | |

| Smoking status (%) | 0.5990 | ||

| Smokers | 20.00% | 17.85% | |

| Nonsmoker | 80.00% | 82.15% | |

| Time since COVID infection (%) | 0.1034 | ||

| Less than 6 mo | 43.22% | 39.2% | |

| 6–12 mo | 49.15% | 45.45% | |

| More than 12 mo | 7.63% | 15.34% |

TABLE 2.

Comorbidities, Vaccine Administration and Disease Severity

| Not Hospitalized | Hospitalized | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID vaccine administrated (%) | 0.027 | ||

| Yes | 67.5% | 77.62% | |

| Comorbidity | <0.0001 | ||

| Asthma | 16.95% | 19.89% | |

| Cardiac disease | 2.54% | 11.65% | |

| Pulmonary disease | 0.85% | 6.82% | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8.47% | 31.25% | |

| Hypertension | 29.66% | 40.91% | |

| None | 38.14% | 21.02% | |

| Severity | |||

| Oxygen supplementation | 0 | 272/352 | |

| ICU admission | 0 | 111/271 | |

| Ventilation | 0 | 42/111 |

Notes: Cardiac disease includes individuals with reported coronary artery disease and congested heart failure. Pulmonary disease includes individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/emphysema, and pulmonary fibrosis.

TABLE 3.

Percent Differences of Comorbidities in Patients Based on ICU and Intubation Status

| N | Hypertension | Diabetes Mellitus | Asthma | Cardiac Disease | Pulmonary Disease | None | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not ICU | 241 | 38.17 | 24.90 | 19.09 | 9.13 | 4.98 | 21.16 |

| ICU, not intubated | 69 | 47.27 | 36.36 | 21.82 | 17.39 | 10.14 | 21.74 |

| Intubated | 42 | 54.76 | 42.86 | 30.95 | 16.67 | 14.29 | 19.05 |

Notes: Cardiac disease includes individuals with reported coronary artery disease and congested heart failure. Pulmonary disease includes individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/emphysema, and pulmonary fibrosis.

TABLE 4.

Means and Standard Deviations of Symptom Severity Scores in Patients Based on ICU and Intubation Status

| VHI-10 | DI | CSI | EAT-10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) Range |

Not ICU | 3.40 (5.82) 31 |

10.33 (10.30) 37 |

5.91 (8.74) 36 |

2.59 (6.55) 40 |

| ICU, not intubated | 4.33 (6.84) 28 |

11.43 (9.76) 33 |

5.55 (8.69) 39 |

2.51 (4.66) 20 |

|

| Intubated | 8.90 (8.77) 29 |

17.45 (12.24) 40 |

11.44 (11.45) 40 |

3.34 (5.79) 30 |

Notes: All questionnaires are scored from 0–40. Higher score indicates more severe symptoms.

Multivariable linear regression

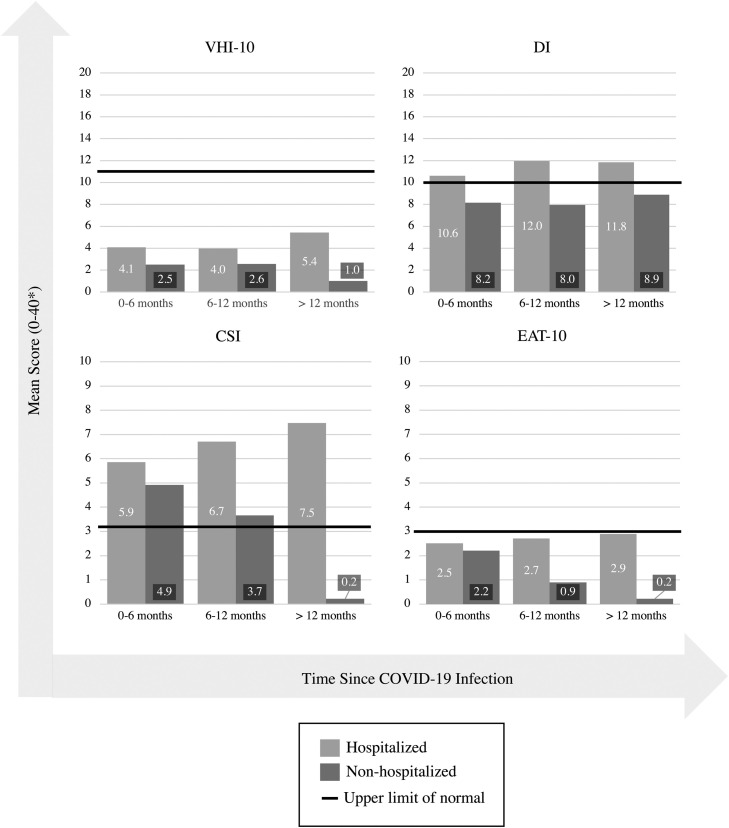

In assessing each symptom severity index, hospitalization status was added as the primary independent variable with age, gender, smoking status, and time since COVID-19 infection as covariates. Table 5 presents all mean scores, standard deviation, and sample size data for subgroups defined by time since infection (0–6 months, 6–12 months, and >12 months). Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the data in comparison to abnormal thresholds for each symptom questionnaire.

TABLE 5.

Means and Standard Deviations of Symptom Severity Scores in Patients Stratified By Time Since Infection

| 0–6 mo Since Infection |

6–12 mo Since Infection |

>12 mo Since Infection |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalized | Nonhospitalized | Hospitalized | Nonhospitalized | Hospitalized | Nonhospitalized | ||

| VHI-10 (abnormal > 11) |

N | 138 | 51 | 160 | 58 | 54 | 9 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.1 (6.6) | 2.5 (5.3) | 4.0 (5.9) | 2.6 (4.5) | 5.4 (8.7) | 1 (1.6) | |

| DI (abnormal > 10) |

N | 136 | 48 | 158 | 57 | 53 | 9 |

| Mean (SD) | 10.6 (10.0) | 8.2 (9.2) | 12.0 (11.0) | 8.0 (8.4) | 11.8 (11.4) | 8.9 (8.2) | |

| CSI (abnormal > 3.23) |

N | 136 | 47 | 157 | 56 | 53 | 9 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.9 (9.3) | 4.9 (8.8) | 6.7 (8.9) | 3.7 (5.8) | 7.5 (10.2) | 0.2 (0.7) | |

| EAT-10 (abnormal ≥ 3) |

N | 156 | 45 | 136 | 56 | 53 | 9 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.5 (5.7) | 2.2 (6.5) | 2.7 (6.7) | 0.9 (2.3) | 2.9 (5.7) | 0.2 (0.7) | |

Note: All questionnaires scored 0–40.

FIGURE 2.

Severity of upper aerodigestive symptoms post COVID-19 Infection.

Voice handicap index—10

Mean VHI-10 scores in both hospitalized and nonhospitalized groups were subclinical. They did not reach abnormal threshold, greater than 11, indicative of those more likely of having a voice disorder.11 However, multivariable linear regression (MLR) showed that VHI-10 scores were statistically significantly greater in hospitalized compared to nonhospitalized participants. Average scores for hospitalized and nonhospitalized were 4.9 (SD 1.4) versus 2.0 (SD 1.6), respectively (P = 0.001).

Figure 2 highlights the mean VHI-10 scores reported at varying times since infection. The highest mean score of voice handicap was reported by hospitalized patients >12 months since infection (mean 5.5, SD 8.7). The lowest mean score of voice handicap was reported at the same postinfection time point, but in nonhospitalized patients (mean 1, SD 1.58).

Dyspnea index

The DI was significantly greater in the hospitalized participants than nonhospitalized. Mean DI score for the hospitalized cohort was 12.7 (2.2) compared to 8.1 (2.5) for nonhospitalized (P = 0.002), for reference, a clinically abnormal DI score is greater than 10.7 DI scores were elevated above the clinical threshold for abnormal for all hospitalized participants at all time-points post COVID-19 infection (Figure 2). Hospitalized individuals continued to report high DI even after 12 months post infection (mean 11.8, SD 11.4).

Cough severity index

MLR analysis found overall CSI mean scores to be significantly elevated in those who were hospitalized (mean 7.0 [1.9]) compared to nonhospitalized (mean = 2.5 [2.2]; P ≤ 0.001). A CSI score >3.23 is indicative of clinically significant cough symptoms.12 Mean reported scores were clinically abnormal at all time points in the post infectious period of those who were hospitalized. Of note, highest mean score in hospitalized patients was reported at >12 months since infection (mean 7.5, SD 10.2), while highest mean score in nonhospitalized patients was reported earlier at 0-6 months since infection (mean 4.9, SD 8.8).

Eating assessment tool-10

Dysphagia symptoms captured by EAT-10 score were significantly greater in hospitalized (mean 3.6, SD 1.3) versus nonhospitalized participants (mean 1.7, SD 1.5) (P = 0.026), per MLR analysis. EAT-10 is considered clinically abnormal at a score of 3 or more.9 Dysphagia was subclinical when assessed at varying time points post infection. At >12 months since infection, the mean EAT-10 score in hospitalized patients was 2.9 (5.7), compared to a mean score of 0.2 (0.7) in nonhospitalized patients at the same time postinfection.

DISCUSSION

Our findings provide relevant and practical insight into the prevalence and severity of specific laryngologic COVID-19 symptoms, with particular focus on how symptomatology may be related to severity of infection and duration of symptoms postinfection. These results are generally consistent with emerging literature.

Laryngeal symptoms and complications of COVID-19 continue to be described in the literature as the pandemic has progressed. In a newly published study of long-COVID outcomes in over 33,000 patients, 33% of individuals reported symptom duration greater than 4 weeks.4 Many of those symptoms assessed were laryngologic, including cough (54%), breathlessness (45%), sore throat (31%) and hoarseness (13%).4 Allisan-Arrighi et al13 found that nonintubated patients with COVID-19 were more likely to be diagnosed with muscle tension dysphonia and laryngopharyngeal reflux. In the recent study by Hastie and colleagues,4 13% of participants reported dysphonia as a symptom during acute COVID-19 infection. That study used symptom checklists and not validated quality of life questionnaires so it is unknown if the dysphonia was long-term or how it affected participants’ lives. Most recently, Shah et al14 described long-term laryngeal complications post infection including dysphonia, dysphagia, COVID-related hypersensitivity and laryngotracheal stenosis.

In our population of participants post-COVID-19 infection, voice handicap, as rated by the VHI-10, was worse in hospitalized than nonhospitalized respondents. The most critically ill participants who required intubation rated the greatest voice handicap postinfection, which is similar to another recent international cohort.15 However, this score did not reach the defined and accepted threshold of clinically significant dysphonia.6 In fact, all respondents, regardless of disease severity and time point postinfection did not reach this threshold. Other investigations have revealed dysphonia can be experienced in up to 20% of patients 6 months post-acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), where the voice disturbance is often attributable directly to the pathophysiology and management of the condition.16 Intubation appears to be a key predictor of dysphonia after critical illness.17 , 18 There is little literature to support any direct pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 on the glottis, however, reports on COVID-19 related dysphonia and laryngeal edema exist.19, 20, 21 Dysphonia remains a minimized symptom, but is prevalent in 3%–9% of the general population where it can impact quality of life and can contribute to lost wages.22 , 23 Post-COVID-19 patients who experiencing significant dysphonia should be evaluated for hyperfunctional muscle-tension-related voice disorders, glottic insufficiency, and vocal manifestations of poor pulmonary function. Challenging diagnoses such as post intubation phonatory insufficiency or posterior glottis stenosis may be more frequently encountered in this population.24 , 25 Laryngoscopy will remain paramount and indicated at any time in the evaluation of a dysphonic patient, and recommended for vocal symptoms lasting longer than 4 weeks.26

Swallowing is a physiologic process that is frequently negatively impacted by systemic disease and critical illness. In large prospective observational studies of the critically ill, dysphagia is observed in 10% of patients at time of ICU discharge, where the majority of patients continue to have swallowing issues through the remainder of their hospitalization.27 Heterogeneous data limits accurate estimates, but immediate postextubation dysphagia rates vary widely in the literature from 3% to 62%.28 Severe swallowing deficits after prolonged intubation, such as penetration and aspiration, are present in up to 35% of patients.29 Longer periods of intubation increase the risk of aspiration as well as subsequent pneumonia.30 A multi-institutional study in Ireland revealed in a group of post-COVID-19 patients referred for SLP evaluation that 84% required modified diets and 31% required alternative forms of nutrition.15 The current study revealed that overall dysphagia symptoms post COVID-19 infection were mild. Only the hospitalized participant group reached clinically meaningful dysphagia symptom severity. Although subgroup analysis was not performed on our dataset, participants who may have suffered severe thromboembolic complications such as CVA or other neurologic insults would be expected to have worse swallowing outcomes than participants who did not.

Acute cough is a common and now stigmatizing symptom in COVID-19 infection, however, its presence may be less specific than fever in those infected, particularly with the Delta variant.31 , 32 Preliminary studies have thus far indicated that persistent cough after SARS-CoV-2 infection for at least 2 months postinfection ranges between 7% and 16%.33, 34, 35 A recent review investigating cough in the setting of Post-COVID syndrome indicates a possible higher prevalence, and discusses potential neurotropism of this virus and neuroinflammatory mechanisms leading to a hypersensitive cough state.36 The exact pathophysiologic mechanisms driving cough post-COVID infection are not completely known, but speculated to be due to parenchymal lung damage, the direct influence of infection of sensory neural tissues, and sensory hypersensitivity.37, 38, 39, 40, 41 Postinfectious cough is not novel to SARS-CoV-2, where previous infection as an etiology for subacute cough lasting >3 but less than 8 weeks ranges from 12% to 48%.42, 43, 44After H1N1 influenza, postinfectious cough was reported as high as 43%, and was objectively associated with 9-fold higher cough reflex sensitivity and worse quality of life when compared to those with no cough.45 There may be cough predilection phenotypes where certain individuals can be susceptible to recurrent bouts of postinfectious cough, and also tend to have a predisposition to elevated cough sensitivity.46 In this cohort, postinfectious cough severity symptoms appear to be dependent on disease severity. Critically ill and intubated participants had the worst cough scores at all time-points. Additionally, there was an inverse symptom course, with hospitalized participants more likely to have worsening scores over time versus improvement in the nonhospitalized participants. Nonhospitalized participants had near normal cough severity scores by 6 months. With these findings in mind, expectant management with cough suppressive therapies and reassurance may suffice for the majority of recovering patients post-COVID.

In its most severe form, COVID-19 infection results in significant aberrations in oxygenation with multilobar pneumonia and ARDS where even young individuals with minimal comorbidities have required extensive cardiopulmonary support including extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.47 In the current cohort, 31.5% of hospitalized respondents reported ICU admission and 6.8% required intubation and mechanical ventilation. Recent reports indicate that up to 74% of patients with severe pulmonary manifestations of COVID-19 (requiring at least 6 L of supplemental oxygen) experience dyspnea at 1 month after discharge.48 Others have reported that 10% of patients experience significant dyspnea at 6 months postinfection, and those admitted to the ICU were more likely to endorse these symptoms than those hospitalized without ICU admission.49 Average postinfection dyspnea scores in our cohort remained abnormally elevated at all time points in hospitalized participants with substantially higher mean scores in recovered mechanically ventilated participants. Although reported data are heterogeneous, the anticipated duration of mechanical ventilation once a patient is intubated for acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19 infection is >9 days.50, 51, 52 The consequences of ARDS, prolonged intubation, and mechanical ventilation can result in anatomic and physiologic abnormalities of the airway and lungs. Herridge et al53 investigated post ARDS cohorts and commonly noted restrictive lung patterns and reduced diffusional capacity at 3 months postillness, where median lung volumes and spirometric values approach 80% predicted by 6 months. At 5 years, spirometry should be expected to be normal or near-normal in surviving patients, and chest CT findings are typically minor where even the extent of disease does not significantly correlate with subjective respiratory symptoms or pulmonary function.54 , 55 Iatrogenic airway stenosis has been reported throughout the literature for decades with the risk of such sequelae often dramatically increasing after a week of orotracheal intubation.56, 57, 58, 59 In the setting of COVID-19, those with milder disease not requiring hospitalization can be reassured that dyspnea symptoms should resolve, while those who were critically ill would benefit from a thorough investigation to ensure no evidence of diminished pulmonary function or sequelae of prolonged intubation or other airway instrumentation such as laryngotracheal stenosis.

Survey studies are not without limitations where informational biases such as recall bias and response fatigue can be expected and can influence outcomes. In this particular study, the surveys were presented to participants in the same order. Despite so many questions, our study had a survey completion rate of 81%. Other possible biases include selection bias where nonresponders could be older, sicker, or even deceased. Another consideration, more specific to this population, is cognitive impairment post-COVID.60 Although we asked patients to report only their current symptoms, cognitive impairment could impact the accuracy of self-reported responses, especially comorbidities and estimated time since infection. Regarding the validity of the questionnaires, each symptom severity index queried is a validated and routinely used patient reported outcome measure. Survey responses were able to be stratified into different time periods since infection, which provides a glimpse of patient experiences and recovery. Therefore, this data may provide some insight into the prevalence of specific symptoms and their severity postinfection. However, a longitudinal cohort study would better assess the progression and severity of these symptoms postinfection. Of note, a key limitation of our results is sample size—particularly when assessing symptoms at different time points post infection. Table 5 presents sample sizes of each subgroup, which make direct comparisons difficult. Importantly, as this data was obtained via cross-sectional survey design, these results are observational and cannot predict causality.

CONCLUSION

In this population, those nonhospitalized with COVID-19 tended to be younger, female, and have less comorbidities than hospitalized participants. At all time-points, all upper aerodigestive symptom severities were worse in those hospitalized with COVID-19 versus not hospitalized. Based on these survey results, dyspnea and cough can be expected to linger or even worsen postinfection in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Dysphonia and dysphagia symptoms were found to be mild. Nonhospitalized participants tended to have minimal symptoms by 1-year postinfection. These findings provide some practical and applicable data that can be clinically useful in counseling patients presenting with persistent complaints after recovering from infection with novel SARS-CoV2. Particularly, those who were hospitalized and critically ill could have sequelae of their illness and management that should warrant Otolaryngology referral.

Authors' contributions

All authors mentioned had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Tkaczuk, Gillespie, Shelly. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Tkaczuk, Shelly. Drafting of the manuscript: Tkaczuk, Shelly, Bouldin, Gillespie. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Tkaczuk, Shelly Bouldin, Gillespie. Study Supervision: Tkaczuk.

Footnotes

This research was presented at the Fall Voice Meeting (2021).

REFERENCES

- 1.Eurosurveillance editorial team Note from the editors: World Health Organization declares novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) sixth public health emergency of international concern. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.200131e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601–615. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hastie CE, Lowe DJ, McAuley A, et al. Outcomes among confirmed cases and a matched comparison group in the Long-COVID in Scotland study. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33415-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosen CA, Lee AS, Osborne J, et al. Development and validation of the voice handicap index-10. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1549–1556. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200409000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gartner-Schmidt JL, Shembel AC, Zullo TG, et al. Development and validation of the dyspnea index (DI): a severity index for upper airway-related dyspnea. J Voice. 2014;28:775–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shembel AC, Rosen CA, Zullo TG, et al. Development and validation of the cough severity index: a severity index for chronic cough related to the upper airway. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1931–1936. doi: 10.1002/lary.23916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, et al. Validity and reliability of the eating assessment tool (EAT-10) Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:919–924. doi: 10.1177/000348940811701210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simopoulos E, Katotomichelakis M, Gouveris H, et al. Olfaction-associated quality of life in chronic rhinosinusitis: adaptation and validation of an olfaction-specific questionnaire. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1450–1454. doi: 10.1002/lary.23349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arffa RE, Krishna P, Gartner-Schmidt J, et al. Normative values for the voice handicap index-10. J Voice. 2012;26:462–465. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shembel AC, Rosen CA, Zullo TG, et al. Development and validation of the cough severity index: a severity index for chronic cough related to the upper airway. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1931–1936. doi: 10.1002/lary.23916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allisan-Arrighi AE, Rapoport SK, Laitman BM, et al. Long-term upper aerodigestive sequelae as a result of infection with COVID-19. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2022;7:476–485. doi: 10.1002/lio2.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah HP, Bourdillon AT, Panth N, et al. Long-term laryngological sequelae and patient-reported outcomes after COVID-19 infection. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;44 doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regan J, Walshe M, Lavan S, et al. Dysphagia, dysphonia, and dysarthria outcomes among adults hospitalized with COVID-19 across Ireland. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(6):1251–1259. doi: 10.1002/lary.29900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Angus DC, Musthafa AA, Clermont G, et al. Quality-adjusted survival in the first year after the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1389–1394. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.2005123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brodsky MB, Levy MJ, Jedlanek E, et al. Laryngeal injury and upper airway symptoms after oral endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation during critical care: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:2010–2017. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000003368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinn JR, Kimura KS, Campbell BR, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute laryngeal injury after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1699–1706. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000004015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Cabaraux P, et al. Features of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients with dysphonia. J Voice. 2022;36(2):249-255 doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asiaee M, Vahedian-Azimi A, Atashi SS, et al. Voice quality evaluation in patients with COVID-19: an acoustic analysis. J Voice. 2022;36(6):879.e13–879.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGrath BA, Wallace S, Goswamy J. Laryngeal oedema associated with COVID-19 complicating airway management. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:972. doi: 10.1111/anae.15092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy N, Merrill RM, Gray SD, et al. Voice disorders in the general population: prevalence, risk factors, and occupational impact. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1988–1995. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000179174.32345.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhattacharyya N. The prevalence of voice problems among adults in the United States. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:2359–2362. doi: 10.1002/lary.24740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bastian RW, Richardson BE. Postintubation phonatory insufficiency: an elusive diagnosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:625–633. doi: 10.1177/019459980112400606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeitels SM, de Alarcon A, Burns JA, et al. Posterior glottic diastasis: mechanically deceptive and often overlooked. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120:71–80. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stachler RJ, Francis DO, Schwartz SR, et al. Clinical practice guideline: hoarseness (dysphonia) (update) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(suppl 1):S1–S42. doi: 10.1177/0194599817751030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schefold JC, Berger D, Zürcher P, et al. Dysphagia in mechanically ventilated ICU patients (DYnAMICS): a prospective observational trial. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:2061–2069. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000002765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skoretz SA, Flowers HL, Martino R. The incidence of dysphagia following endotracheal intubation: a systematic review. Chest. 2010;137:665–673. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheel R, Pisegna JM, McNally E, et al. Endoscopic assessment of swallowing after prolonged intubation in the ICU setting. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125:43–52. doi: 10.1177/0003489415596755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim MJ, Park YH, Park YS, et al. Associations between prolonged intubation and developing post-extubation dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia in non-neurologic critically ill patients. Ann Rehabil Med. 2015;39:763–771. doi: 10.5535/arm.2015.39.5.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen JR, Martin MR, Martin JD, et al. Modeling the onset of symptoms of COVID-19. Front Public Health. 2020;8:473. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho HJ, Heinsar S, Jeong IS, et al. ECMO use in COVID-19: lessons from past respiratory virus outbreaks-a narrative review. Crit Care. 2020;24:301. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02979-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Cruz RF, Waller MD, Perrin F, et al. Chest radiography is a poor predictor of respiratory symptoms and functional impairment in survivors of severe COVID-19 pneumonia. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00655-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnold DT, Hamilton FW, Milne A, et al. Patient outcomes after hospitalisation with COVID-19 and implications for follow-up: results from a prospective UK cohort. Thorax. 2021;76:399–401. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song WJ, Hui CKM, Hull JH, et al. Confronting COVID-19-associated cough and the post-COVID syndrome: role of viral neurotropism, neuroinflammation, and neuroimmune responses. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:533–544. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(21)00125-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones RM, Hilldrup S, Hope-Gill BD, et al. Mechanical induction of cough in Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Cough. 2011;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-9974-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ojha V, Mani A, Pandey NN, et al. CT in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of chest CT findings in 4410 adult patients. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:6129–6138. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-06975-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meinhardt J, Radke J, Dittmayer C, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:168–175. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dicpinigaitis PV, Bhat R, Rhoton WA, et al. Effect of viral upper respiratory tract infection on the urge-to-cough sensation. Respir Med. 2011;105:615–618. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dicpinigaitis PV. Effect of viral upper respiratory tract infection on cough reflex sensitivity. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(Suppl 7):S708–S711. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.12.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamasaki A, Hanaki K, Tomita K, et al. Cough and asthma diagnosis: physicians' diagnosis and treatment of patients complaining of acute, subacute and chronic cough in rural areas of Japan. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3:101–107. doi: 10.2147/ijgm.s8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishida T, Yokoyama T, Iwasaku M, et al. Clinical investigation of postinfectious cough among adult patients with prolonged cough. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2010;48:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwon NH, Oh MJ, Min TH, et al. Causes and clinical features of subacute cough. Chest. 2006;129:1142–1147. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ryan NM, Vertigan AE, Ferguson J, et al. Clinical and physiological features of postinfectious chronic cough associated with H1N1 infection. Respir Med. 2012;106:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin L, Yang ZF, Zhan YQ, et al. The duration of cough in patients with H1N1 influenza. Clin Respir J. 2017;11:733–738. doi: 10.1111/crj.12409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dreier E, Malfertheiner MV, Dienemann T, et al. ECMO in COVID-19-prolonged therapy needed? A retrospective analysis of outcome and prognostic factors. Perfusion. 2021;36:582–591. doi: 10.1177/0267659121995997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weerahandi H, Hochman KA, Simon E, et al. Post-discharge health status and symptoms in patients with severe COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:738–745. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06338-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taboada M, Cariñena A, Moreno E, et al. Post-COVID-19 functional status six-months after hospitalization. J Infect. 2021;82:e31–e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karagiannidis C, Mostert C, Hentschker C, et al. Case characteristics, resource use, and outcomes of 10 021 patients with COVID-19 admitted to 920 German hospitals: an observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30316-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee YH, Choi KJ, Choi SH, et al. Clinical significance of timing of intubation in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a multi-center retrospective study. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2847):1-13 doi: 10.3390/jcm9092847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roedl K, Jarczak D, Thasler L, et al. Mechanical ventilation and mortality among 223 critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019: a multicentric study in Germany. Aust Crit Care. 2021;34:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilcox ME, Patsios D, Murphy G, et al. Radiologic outcomes at 5 years after severe ARDS. Chest. 2013;143:920–926. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whited RE. A prospective study of laryngotracheal sequelae in long-term intubation. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:367–377. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198403000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Volpi D, Lin PT, Kuriloff DB, et al. Risk factors for intubation injury of the larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1987;96:684–686. doi: 10.1177/000348948709600614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gelbard A, Francis DO, Sandulache VC, et al. Causes and consequences of adult laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:1137–1143. doi: 10.1002/lary.24956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hillel AT, Karatayli-Ozgursoy S, Samad I, et al. Predictors of posterior glottic stenosis: a multi-institutional case-control study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125:257–263. doi: 10.1177/0003489415608867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ceban F, Ling S, Lui LMW, et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;101:93–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]