Abstract

The objective of this study was to explore the relationship between accumulating adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and sipping alcohol in a large, nationwide sample of 9-to-10-year-old U.S. children. We analyzed data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (2016–2018). Of 10,853 children (49.1 % female), 23.4 % reported ever sipping alcohol. A greater ACE score was associated with a higher risk of sipping alcohol. Having 4 or more ACEs placed children at 1.27 times the risk (95 % CI 1.11–1.45) of sipping alcohol compared to children with no ACEs. Among the nine distinct ACEs examined, household violence (Risk Ratio [RR] = 1.13, 95 % CI 1.04–1.22) and household alcohol abuse (RR = 1.14, 95 % CI 1.05–1.22) were associated with sipping alcohol during childhood. Our findings indicate a need for increased clinical attention to alcohol sipping among ACE-exposed children.

Keywords: Adverse childhood experiences, Alcohol, Sipping, Substance use, Childhood, Pediatrics

Abbreviations: ACEs, Adverse childhood experiences; ABCD, Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development study

1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events that occur before the age of 18 and can have long-term negative health consequences (Petruccelli et al., 2019). ACEs span an array of adverse experiences including neglect, household dysfunction, and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse (Felitti et al., 1998, Karcher et al., 2020). ACEs affect nearly half of American youth and are associated with numerous long-term and deleterious mental and physical health outcomes such as obesity, depression, and anxiety (Santos et al., 2022).

In addition to the above consequences, ACEs have been associated with high-risk health behaviors such as binge drinking, smoking, and other substance use (Domoff et al., 2021). A recent meta-analysis finds that ACEs are moderately associated with heavy alcohol use and strongly associated with problematic alcohol use (Hughes et al., 2017). According to prior research, youth with a greater exposure to adversity during childhood may engage in problematic alcohol use due to reduced self-regulatory abilities (Lackner et al., 2018) or as a coping mechanism against their trauma (Dube et al., 2006).

Although previous studies have established associations between ACEs and overall alcohol use (Afifi et al., 2020) as well as binge drinking (Domoff et al., 2021), the examination of alcohol sipping within the context of ACEs has been overlooked. Sipping is characterized by taking one or multiple sips of alcohol without consuming a full standard drink (Donovan, 2007). Sipping is the most common form of alcohol use among children and young adolescents (Aiken et al., 2020) and has been associated with a greater frequency and quantity of drinking in adulthood (Aiken et al., 2020). Despite widespread perceptions of being innocuous (Jones et al., 2016), childhood sipping may be a useful predictor of alcohol use and related future adverse outcomes (Jackson et al., 2015b). For instance, children who sip alcohol by sixth grade have a higher likelihood of consuming a full drink, getting drunk, and engaging in heavy drinking (3+ drinks/occasion) by ninth grade (Jackson et al., 2015a). Additionally, children who sip alcohol by age 10 are more likely to drink (i.e., beyond a sip) by age 14 compared to those who do not engage in sipping (Donovan and Molina, 2011).

Further, previous studies have primarily focused on alcohol use during adolescence rather than childhood, a crucial period of growth and development in its own right (Dahl et al., 2018). The current study aims to address gaps in the literature by examining the relationship between accumulating ACEs (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4+) and childhood sipping in a large sample of U.S. children ages 9–10 from the nationwide Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. Several factors including child religiosity (Francis et al., 2019), sex, sexual orientation (Hughes et al., 2016), race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (Collins, 2016) may be potential confounders of this relationship and are accounted for in our analysis. We hypothesize that elevated ACE scores among children will be associated with a higher risk of sipping alcohol after adjusting for confounders.

2. Methods

Baseline cross-sectional data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study (Year 0 assessment; 2016–2018; fourth annual [4.0] data release) were analyzed. The ABCD study utilized probability sampling of U.S. elementary schools to identify and recruit 9–10-year-old participants from 21 research sites nationwide across the US (Garavan et al., 2018). The racial and ethnic composition of children in the study mirrors the overall demographics of the U.S. (Garavan et al., 2018). Further details about the ABCD Study® participants, recruitment, protocol, and measures have been previously described (Garavan et al., 2018). We examined individual differences in the relationship between ACEs and alcohol sipping among a sample from the ABCD cohort. Participants with missing data for ACEs and alcohol sipping were excluded, leaving a sample size of 10,853 children (Appendix 1). Centralized institutional review board approval was received from the University of California, San Diego. Study sites obtained approval from their local institutional review boards. Caregivers provided written informed consent, and each child provided written assent.

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Independent variables

ACEs data were collected from child and parental responses to adverse experience questions at baseline (2016–2018). The ABCD study reflects 9 out of 10 domains listed in the original ACEs study (Felitti et al., 1998). The 9 domains included in this study are physical abuse, sexual abuse, household violence, parental alcohol abuse, parental mental health issues, parent marital status (divorced/separated), emotional neglect, physical neglect, and household criminal justice system involvement (Appendix B). ACE scores were calculated and categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4+ ACEs (Raney et al., 2022, Testa et al., 2022). The 4+ threshold was chosen because it was found to be a valid threshold for a marker of increased risk across multiple ACE screening tools (Kerker et al., 2015, McKelvey et al., 2016).

2.1.2. Outcome variables

Children who responded “yes” to the question “Have you heard of alcohol, such as beer, wine or liquor?” in the ABCD assessment were then asked whether they had ever tried a sip of alcohol such as beer, wine, or liquor (rum, vodka, gin, whiskey) using an online adapted version of the Timeline Follow-Back instrument (Lisdahl et al., 2018). The Timeline Follow-Back is a calendar-based self-report instrument that measures the use of alcohol and other addictive substances retrospectively (Sobell and Sobell, 1992). It has been found to be reliable, psychometrically sound, and to display concurrent validity with other instruments (Janssen et al., 2017, Martin-Willett et al., 2020). The Timeline Follow-Back has been validated in adolescents who self-reported alcohol use (Harris et al., 2016, Levy et al., 2021, Martin-Willett et al., 2020); self-reports of alcohol consumption are highly correlated (r = 0.780–0.886, p < 0.001) between the online and in-person Timeline Follow-Back (Martin-Willett et al., 2020). Additionally, the Timeline Follow-Back demonstrated strong intra-class correlations (ICC = 0.79–0.82) and agreement between assessments at 6 and 12 months, indicating test–retest reliability (Janssen et al., 2017).

2.1.3. Covariates

Based on demographic differences reported in the literature (Lees et al., 2021, Stinson et al., 2021), we selected age, sex (female, male), sexual minority (no, yes or questioning, don’t understand the question) as assessed by the Kiddie Schedule of Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia background items (Potter et al., 2022, Townsend et al., 2020), child religiosity (religious/non-religious) (Francis et al., 2019), race/ethnicity (White, Latino/Hispanic, Black, Asian, Native American, other), household income (greater than or less than $75,000 U.S. dollars, which approximates the U.S. household median) (Nagata et al., 2021) and highest parent education (high school or less vs college or more) as confounders in the association between having ACEs and sipping alcohol. Gaussian normal regression imputation was used for missing household income and parent education data as has been previously described.

2.2. Statistical analyses

Weighted Poisson regression with robust standard errors (Zou, 2004) was used to estimate risk ratios for the associations between baseline ACE score and self-report of sipping alcohol at any point before the baseline visit, adjusted for the potential confounders listed above. Separate models were used to estimate associations of sipping first with the number of ACES and then with ACE subtypes. To aid with interpretation of the findings, adjusted sipping probabilities were calculated using regression standardization based on the Poisson model. Propensity weights were used in both the model and regression standardization steps so that sociodemographic variables in the ABCD Study matched the American Community Survey from the U.S. Census (Heeringa and Berglund, 2020). All analyses were conducted in 2022 using Stata 17 (StataCorp).

3. Results

Among a racially/ethnically diverse sample of 10,853 children ages 9.0–10.9 years (45 % racial/ethnic minorities; 49 % female), a large proportion of children reported having experienced household violence (43 %) and household alcohol abuse (42 %; Appendix C). These domains were followed by nearly a third of children who reported parental mental health issues (32 %) and children who reported parent divorce/separation (16 %) and household criminal justice system involvement (15 %). Nearly a quarter of the total sample (23 %) reported ever sipping alcohol.

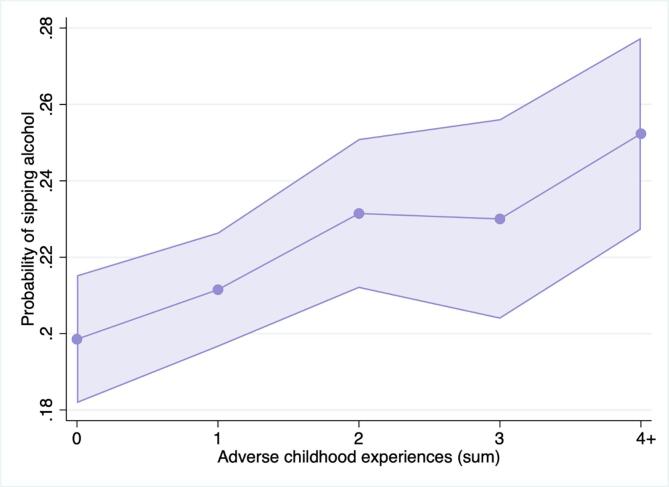

Table 1 and Appendix D show multiple modified Poisson regression analyses indicating that a greater ACE score category was associated with a higher risk of alcohol sipping (p for trend < 0.001). Notably, having 4 or more ACEs was associated with 1.27 times the risk (95 % confidence interval [CI] 1.11–1.45) of sipping alcohol compared to children with no ACEs. Regarding ACEs subtypes, household violence (Risk Ratio [RR] = 1.13 [95 % CI 1.04–1.22]) and household alcohol abuse (RR = 1.14 [95 % CI 1.05–1.22]) were statistically significant. Adjusted probabilities of alcohol sipping as a function of the number of ACEs are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Associations between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and alcohol sipping in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study.

| Sipping alcohol, adjusted |

||

|---|---|---|

| Risk Ratio (95 % CI) | p | |

| Number of ACEs | ||

| 0 ACEs | reference | |

| 1 ACEs | 1.06 (0.96–1.18) | 0.239 |

| 2 ACEs | 1.16 (1.04–1.31) | 0.009 |

| 3 ACEs | 1.16 (1.01–1.34) | 0.040 |

| ≥4 ACEs | 1.27 (1.11–1.45) | <0.001 |

| ACE subtypesa | ||

| Physical abuse | 1.33 (0.91–1.93) | 0.129 |

| Sexual abuse | 1.31 (0.90–1.91) | 0.157 |

| Household violence | 1.13 (1.04–1.22) | 0.002 |

| Household alcohol abuse | 1.14 (1.05–1.22) | 0.001 |

| Household mental illness | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) | 0.210 |

| Parental divorce/separation | 1.11 (0.99–1.24) | 0.071 |

| Emotional neglect | 1.15 (0.81–1.62) | 0.439 |

| Physical neglect | 0.89 (0.72–1.09) | 0.270 |

| Household criminal justice system involvement | 1.13 (1.00–1.27) | 0.058 |

Bold indicates p < 0.05. ABCD propensity weights were applied based on the American Community Survey from the U.S. Census.

Adjusted models include age, sex, child religiosity, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, household income, and parent education.

The risk ratios under ACE subtypes represent abbreviated outputs from a series of nine separate Poisson regression models with each ACE subtype as the independent variable and sipping alcohol as the dependent variable, adjusted for the confounders listed above.

Fig. 1.

Adjusted probabilities of adverse childhood experiences and alcohol sipping.

4. Discussion

This large study featuring a nationwide sample of U.S. children found that exposure to 2, 3, and 4+ ACEs was associated with a higher risk of sipping alcohol compared to having 0 ACEs. Accumulating ACEs (1, 2, 3, and 4 or more ACEs) generally displayed a dose-dependent relationship to sipping risk. Having 4 or more ACEs was associated with the highest risk of sipping alcohol, which is consistent with prior research linking accumulating ACEs, especially upon crossing the “4 or more ACEs” threshold, to multiple adverse social, medical, and mental health outcomes (Briggs et al., 2021, Kerker et al., 2015, McKelvey et al., 2016, Testa et al., 2021). Of the 9 individual ACE domains examined, household violence (RR = 1.13) and household alcohol abuse (RR = 1.14) were specifically associated with an elevated alcohol sipping risk. This finding is especially concerning given the prevalence of household violence (43 %) and household alcohol abuse (42 %) among the diverse sample.

The present study builds upon research that has identified relationships between ACEs and various forms of substance use (Afifi et al., 2020, Pilowsky et al., 2009) by demonstrating a novel association between ACE scores and sipping alcohol during childhood. ACEs could be related to sipping due to factors such as peer substance use (Shin et al., 2018), children’s imitation of parental behaviors (Gaines et al., 1988, Kandel, 1980), or ACEs’ effects on stress hormones (Lewis-de los Angeles, 2022). Further, since childhood sipping usually occurs within the household setting at an adult’s proffer (Jackson et al., 2015b), it is possible that parents with substance use disorders may more frequently offer sips to their children.

Our study adds to the literature by assessing ACEs and sipping within a childhood sample. The developmental transition from childhood to adolescence is an especially crucial period in which health-related behavioral risk factors are established (Dahl et al., 2018). Therefore, understanding the dynamics of alcohol use – not only in large amounts, but also in sips – is critical to informing public health interventions that disrupt children’s drinking patterns, especially among those who have experienced ACEs. This study further emphasizes the importance of screening for both ACEs and early alcohol use in children. Upon a positive screening, clinicians can educate patients and their families about the potential hazards of sipping and its status as an early predictor of future problematic drinking. Clinicians can then adopt a trauma-informed perspective to devise individualized strategies targeting early sipping among ACE-exposed children. The implications of screening for ACEs and early alcohol use extend beyond sipping; such screenings may also help identify and provide wider supports such as food purchasing assistance, therapy for families in need, strategies to reduce toxic stress and, following a safety assessment, child protective services as needed.

Study limitations include the use of self-reported data and possible recall bias. Some participants may not yet be aware of their sexual orientation given that the average age of first same-sex attraction is 12 (Bishop et al., 2020). However, three quarters of participants understood the question and we included as a separate category the 24 % who reported they did not understand the question. Residual confounders may exist that were not identified, and the cross-sectional design limits our ability to make causal inferences. Finally, one domain from the original ACEs study (emotional abuse) was not assessed, thus we cannot examine its effects.

5. Conclusions

Our findings underscore the significance of investigating sipping among ACE-exposed children, educating families about the potential for downstream health consequences, and developing multidisciplinary treatment options. Future studies can investigate resilience-building factors that discourage early sipping and minimize the association between childhood adversity and negative health behaviors.

Funding

J.M.N. was funded by the National Institutes of Health (K08HL159350), the American Heart Association Career Development Award (CDA34760281), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (2022056). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The ABCD Study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Maryland) and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041022, U01DA041025, U01DA041028, U01DA041048, U01DA041089, U01DA041093, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041120, U01DA041134, U01DA041148, U01DA041156, U01DA041174, U24DA041123, and U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners/. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/principal-investigators.html. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in the analysis or writing of this report.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Levi Cervantez and Anthony Kung for their editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102153.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ABCD Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). https://nda.nih.gov/

References

- Afifi T.O., Taillieu T., Salmon S., Davila I.G., Stewart-Tufescu A., Fortier J., Struck S., Asmundson G.J.G., Sareen J., MacMillan H.L. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), peer victimization, and substance use among adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;106 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken A., Clare P.J., Boland V.C., Degenhardt L., Yuen W.S., Hutchinson D., Najman J., McCambridge J., Slade T., McBride N., de Torres C., Wadolowski M., Bruno R., Kypri K., Mattick R.P., Peacock A. Parental supply of sips and whole drinks of alcohol to adolescents and associations with binge drinking and alcohol-related harms: a prospective cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;215 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop M.D., Fish J.N., Hammack P.L., Russell S.T. Sexual identity development milestones in three generations of sexual minority people: a national probability sample. Dev. Psychol. 2020;56:2177. doi: 10.1037/DEV0001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, E.C., Putnam, F.W., Purbeck, C., 2021. Why Two Can be Greater Than Four or More: What Mental Health Providers Should Know. Los Angeles, CA and Durham, NC.

- Collins S.E. Associations between socioeconomic factors and alcohol outcomes. Alcohol Res. 2016;38:83–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl R.E., Allen N.B., Wilbrecht L., Suleiman A.B. Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature. 2018;554:441–450. doi: 10.1038/nature25770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domoff S.E., Borgen A.L., Wilke N., Hiles Howard A. Adverse childhood experiences and problematic media use: perceptions of caregivers of high-risk youth. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J.E. Really underage drinkers: the epidemiology of children’s alcohol use in the United States. Prev. Sci. 2007;8:192–205. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0072-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan J.E., Molina B.S.G. Childhood risk factors for early-onset drinking. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:741–751. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S.R., Miller J.W., Brown D.W., Giles W.H., Felitti V.J., Dong M., Anda R.F. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. J. Adolesc. Health. 2006;38:444.e1–444.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V.J., Anda R.F., Nordenberg D., Williamson D.F., Spitz A.M., Edwards V., Koss M.P., Marks J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis J.M., Myers B., Nkosi S., Williams P.P., Carney T., Lombard C., Nel E., Morojele N. The prevalence of religiosity and association between religiosity and alcohol use, other drug use, and risky sexual behaviours among grade 8–10 learners in Western Cape, South Africa. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0211322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines L.S., Brooks P.H., Maisto S., Dietrich M., Shagena M. The development of children’s knowledge of alcohol and the role of drinking. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 1988;9:441–457. doi: 10.1016/0193-3973(88)90011-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H., Bartsch H., Conway K., Decastro A., Goldstein R.Z., Heeringa S., Jernigan T., Potter A., Thompson W., Zahs D. Recruiting the ABCD sample: design considerations and procedures. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018;32:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris S.K., Knight J.R., van Hook S., Sherritt L., Brooks T., Kulig J.W., Nordt C., Saitz R. Adolescent substance use screening in primary care: validity of computer self-administered vs. clinician-administered screening. Subst. Abus. 2016;37:197–203. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2015.1014615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa, S.G., Berglund, P.A., 2020. A guide for population-based analysis of the adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study baseline data. bioRxiv 2020.02.10.942011. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.10.942011.

- Hughes K., Bellis M.A., Hardcastle K.A., Sethi D., Butchart A., Mikton C., Jones L., Dunne M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e356–e366. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T.L., Wilsnack S.C., Kantor L.W. The influence of gender and sexual orientation on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems: Toward a global perspective. Alcohol Res. 2016;38:121–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K.M., Barnett N.P., Colby S.M., Rogers M.L. The prospective association between sipping alcohol by the sixth grade and later substance use. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76:212–221. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson K.M., Colby S.M., Barnett N.P., Abar C.C. Prevalence and correlates of sipping alcohol in a prospective middle school sample. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2015;29:766–778. doi: 10.1037/adb0000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen T., Braciszewski J.M., Vose-O’Neal A., Stout R.L. A comparison of long- vs. Short-term recall of substance use and HIV risk behaviors. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78:463–467. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S.C., Andrews K., Berry N. Lost in translation: a focus group study of parents’ and adolescents’ interpretations of underage drinking and parental supply. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3218-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D.B. Drug and drinking behavior among youth. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1980;6:235–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.06.080180.001315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karcher N.R., Niendam T.A., Barch D.M. Adverse childhood experiences and psychotic-like experiences are associated above and beyond shared correlates: findings from the adolescent brain cognitive development study. Schizophr. Res. 2020;222:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerker B.D., Zhang J., Nadeem E., Stein R.E.K., Hurlburt M.S., Heneghan A., Landsverk J., McCue Horwitz S. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health, chronic medical conditions, and development in young children. Acad. Pediatr. 2015;15:510–517. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner C.L., Santesso D.L., Dywan J., O’Leary D.D., Wade T.J., Segalowitz S.J. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with self-regulation and the magnitude of the error-related negativity difference. Biol. Psychol. 2018;132:244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees B., Stapinski L.A., Teesson M., Squeglia L.M., Jacobus J., Mewton L. Problems experienced by children from families with histories of substance misuse: an ABCD study®. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;218 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S., Wisk L.E., Chadi N., Lunstead J., Shrier L.A., Weitzman E.R. Validation of a single question for the assessment of past three-month alcohol consumption among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;228 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-de los Angeles W.W. Association between adverse childhood experiences and diet, exercise, and sleep in pre-adolescents. Acad. Pediatr. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisdahl K.M., Sher K.J., Conway K.P., Gonzalez R., Feldstein Ewing S.W., Nixon S.J., Tapert S., Bartsch H., Goldstein R.Z., Heitzeg M. Adolescent brain cognitive development (ABCD) study: overview of substance use assessment methods. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018;32:80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Willett R., Helmuth T., Abraha M., Bryan A.D., Hitchcock L., Lee K., Bidwell L.C. Validation of a multisubstance online Timeline Followback assessment. Brain Behav. 2020;10:1–10. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey L.M., Whiteside-Mansell L., Conners-Burrow N.A., Swindle T., Fitzgerald S. Assessing adverse experiences from infancy through early childhood in home visiting programs. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;51:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata J.M., Iyer P., Chu J., Baker F.C., Pettee Gabriel K., Garber A.K., Murray S.B., Bibbins-Domingo K., Ganson K.T. Contemporary screen time modalities among children 9–10 years old and binge-eating disorder at one-year follow-up: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021;54:887–892. doi: 10.1002/eat.23489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petruccelli K., Davis J., Berman T. Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;97 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky D.J., Keyes K.M., Hasin D.S. Adverse childhood events and lifetime alcohol dependence. Am. J. Public Health. 2009;99:258–263. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter A.S., Dube S.L., Barrios L.C., Bookheimer S., Espinoza A., Feldstein Ewing S.W., Freedman E.G., Hoffman E.A., Ivanova M., Jefferys H., McGlade E.C., Tapert S.F., Johns M.M. Measurement of gender and sexuality in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2022;53 doi: 10.1016/J.DCN.2022.101057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raney J., Testa A., Jackson D.B., Ganson K.T., Nagata J. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, adolescent screen time and physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad. Pediatr. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2022.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M., Burton E.T., Cadieux A., Gaffka B. Adverse childhood experiences, health behaviors, and associations with obesity among youth in the United States. Behav. Med. 2022;1–11 doi: 10.1080/08964289.2022.2077294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S.H., McDonald S.E., Conley D. Patterns of adverse childhood experiences and substance use among young adults: a latent class analysis sunny. Addict. Behav. 2018;78:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L.C., Sobell M.B. In: Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Litten R., Allen J., editors. The Humana Press Inc.; 1992. Timeline Follow-Back: A Technique for Assessing Self-Reported Alcohol Consumption; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson E.A., Sullivan R.M., Peteet B.J., Tapert S.F., Baker F.C., Breslin F.J., Dick A.S., Gonzalez M.R., Guillaume M., Marshall A.T., McCabe C.J., Pelham W.E., van Rinsveld A., Sheth C.S., Sowell E.R., Wade N.E., Wallace A.L., Lisdahl K.M. Longitudinal impact of childhood adversity on early adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the ABCD study cohort: does race or ethnicity moderate findings? Biol. Psychiatry: Global Open Sci. 2021;1:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa A., Jackson D.B., Ganson K.T., Nagata J.M. Adverse childhood experiences and criminal justice contact in adulthood. Acad. Pediatr. 2021;22 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa A., Jackson D.B., Boccio C., Ganson K.T., Nagata J.M. Adverse childhood experiences and marijuana use during pregnancy: findings from the North Dakota and South Dakota PRAMS, 2017–2019. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;230 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend L., Kobak K., Kearney C., Milham M., Andreotti C., Escalera J., Alexander L., Gill M.K., Birmaher B., Sylvester R., Rice D., Deep A., Kaufman J. Development of three web-based computerized versions of the kiddie schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia child psychiatric diagnostic interview: preliminary validity data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2020;59:309–325. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the ABCD Study (https://abcdstudy.org), held in the NIMH Data Archive (NDA). https://nda.nih.gov/