SUMMARY

Objective

Our objective was to specify the indications and duration of effectiveness of Awake Patient Polyp Surgery (APPS) in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps (CRSwNP). Secondary objectives were to evaluate complications and Patient-Reported Experience (PREMs) and Outcome Measures (PROMs).

Methods

We collected information regarding sex, age, comorbidities and treatments. Duration of effectiveness was the duration of non-recurrence defined by the time between APPS and a new treatment. Nasal Polyp Score (NPS) and Visual Analogic Scales (VAS, from 0/10 to 10/10) for nasal obstruction and olfactory disorders were assessed preoperatively and one month after surgery. PREMs were evaluated using a new tool: the APPS score.

Results

Seventy-five patients were enrolled (SR = 3.1, mean age = 60.9 ± 12.3 years). 60% of patients had a previous history of sinus surgery, 90% had stage 4 NPS and more than 60% had overuse of systemic corticosteroids. Mean time of non-recurrence was 31.3 ± 2.3 months. We found a significant improvement (all p < 0.001) for NPS (3.8 ± 0.4 vs 1.5 ± 0.6), VAS obstruction (9.5 ± 1.6 vs 0.9 ± 1.7) and VAS olfactory disorders (4.9 ± 0.2 vs 3.8 ± 1.7). Mean APPS score was 46.3 ± 5.5/50.

Conclusions

APPS is a safe and efficient procedure in the management of CRSwNP.

KEY WORDS: sinusitis, nasal polyps, endoscopic sinus surgery, inflammatory nasal disease, local anesthesia

RIASSUNTO

Obiettivo

Descrivere indicazioni e risultati dell’intervento di polipectomia nasosinusale in anestesia locale (APPS) in pazienti con rinosinutite cronica polipoide (CRSwNP). Obiettivo secondario è la valutazione delle complicanze post-operatorie, dell’esperienza soggettiva del paziente (PREMs) e la misurazione dell’outcome terapeutico (PROMs).

Metodi

L’efficacia del trattamento è stata definita come intervallo di tempo in assenza di recidiva, stimato come il tempo tra due trattamenti successivi. La clinica è stata quantificata applicando il Nasal Polyp Score (NPS) e la Visual Analogic Scales (VAS) per ostruzione nasale e disturbi olfattivi, valutati prima e un mese dopo la procedura. La PREM è stata valutata utilizzando un nuovo strumento: l’APPS score.

Risultati

Sono stati inclusi 75 pazienti. Il tempo medio in assenza di recidiva è stato di 31,3 ± 2,3 mesi. In seguito ad APPS sono stati documentati miglioramenti significativi (p < 0,001) per NPS (3,8 ± 0,4 vs 1,5 ± 0,6), VAS per ostruzione nasale (9,5 ± 1,6 vs 0,9 ± 1,7), VAS per disturbi olfattivi (4,9 ± 0,2 vs 3,8 ± 1,7). L’APPS score medio è stato di 46,3 ± 5,5/50.

Conclusioni

APPS si è rivelata essere una procedura sicura ed efficace nel trattamento della CRSwNP.

PAROLE CHIAVE: rinosinusite cronica, poliposi nasale, chirurgia endoscopica naso-sinusale, patologia infiammatoria nasale, anestesia locale

Introduction

Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps (CRSwNP) is a debilitating disease affecting 2.8-5.8% of the European population and gives rise to significant impairment of patients’ health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) and inflated public health costs 1. The first-line treatment of CRSwNP combines local treatment with short courses of systemic corticosteroids that should not exceed 500 to 1000 mg per year to avoid short- and long-term side effects (osteoporosis, diabetes, etc.) 2.

When medical treatments are insufficient, the practitioner should consider surgery. Severe CRSwNP may involve repeated endoscopic sinus surgeries (ESS). Usually, such surgeries require general anaesthesia (GA), which can be unsafe for vulnerable patients and professionally disabling for young and active patients. This has led to the development in recent years of ESS performed under local anaesthesia, also called Awake Patient Polyp Surgery (APPS) in our centre. Increasingly practiced in Northern America and the UK, APPS appears to be beneficial from a cost perspective, especially for office-based surgeries 3. However, to date, few studies have investigated the indications and duration of effectiveness of APPS in CRSwNP 4.

The main objective of this study was thus to clarify the indications and duration of effectiveness of APPS in patients with CRSwNP. Secondary objectives were to evaluate Patient-Reported Experience Measures (PREMs), Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and APPS complications.

Materials and methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All adult patients operated on in our centre for CRSwNP under local anaesthesia between February 2018 and March 2021 were included. Non-inclusion criterion was age under 18 years.

Description of the Awake Patient Polyp Surgery (APPS) procedure

Preoperatively, the patient was received at the hospital by the nursing team and escorted to the operating room for local anaesthesia. Patients received no premedication and were placed in a semi-seated position to limit the risk of inhalation. Local anaesthesia was performed by dabbing the nasal cavities with cotton-wool soaked in naphazoline with xylocaine for 10 minutes. No infiltration of vasoconstrictor was performed. Using a microdebrider (Medtronic® 2.9 mm blade, Dublin, Ireland) connected to a suction tube, the surgery consisted in polyp removal, without opening the paranasal sinuses that were not opened during previous operations. Posterior nasal packings were used to prevent inhalation only in case of significant intraoperative bleeding. Most of the time, posterior nasal packings were not needed as small amounts of bleeding were easily suctioned by the microdebrider. Postoperative treatment included large-volume nasal lavages, corticosteroid nasal sprays (400 micrograms a day) and antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for 7 days). No systemic corticosteroid therapy was prescribed in any case.

Data collection

Data collection was carried out by consulting patients’ medical records, during follow-up consultations, or through teleconsultation due to the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. We collected information regarding sex, age, comorbidities [asthma, aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), etc.], treatments and doses of corticoid therapies, history of nasal surgery with type and date and eosinophil levels. We also analysed the nasal polyp score (NPS) (range: 0/4 to 4/4 for each side) preoperatively and one month after surgery.

Main outcome measurement

By studying the population’s characteristics, we were able to determine APPS indications and factors influencing the duration of effectiveness. The duration of effectiveness was the duration of non-recurrence defined by the time between APPS and the need for a new treatment. A new (systemic corticosteroid therapy or surgery) treatment was proposed if patients complained of nasal symptoms in association with polyp recurrence observed at endoscopic examination (NPS > 2 for each side). In patients with no recurrence of nasal symptoms, the duration of effectiveness was, at least, the time between APPS and the date of the last medical consultation.

Secondary outcome measurement

PREMs AND PROMs

PREMs are measures usually carried out using a self-reported questionnaire to assess patients’ feelings or experiences related to a treatment. As no specific tool is reported in the literature, we evaluated PREMs by means of a new questionnaire, the APPS (Awake Patient Sinus Surgery) score (Tab. I). The questionnaire included 10 questions (Likert scale from 1 to 5) assessing the patients’ experience before, during and after APPS. APPS scores ranged from 10 to 50. The higher the score, the better the outcome.

Table I.

Awake Patient Polyp Surgery (APPS) questionnaire.

| APPS questionnaire | ||

| Please indicate your level of agreement with each of the following statements using the following scale: | ||

| ||

| Before APPS | During APPS | After APPS |

| 1) I was reassured to be operated on under local anesthesia |

|

|

PROMs were analysed preoperatively and at one month postoperatively using Visual Analogic Scales (from 0/10 to 10/10) for nasal obstruction and olfactory disorders. The higher the score, the lower the outcome.

COMPLICATIONS

Major complications included nasal bleeding requiring re-hospitalisation or revision surgery, intraoperative blood inhalation, orbital breach or haematoma, CSF leak or the need to stop surgery. Minor complications were postoperative nasal bleeding requiring nasal packing, postoperative pain and infections requiring prolonged antibiotic therapy.

STATISTICS

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software. The paired series involved a comparison test used to assess duration of effectiveness, pre- and postoperative differences in nasal obstruction VAS, olfactory disorders VAS and pre- and postoperative differences in NPS. The significance level was set at 0.05 for all analyses. The highest NPS from both the right and left nasal fossae was used for statistical analyses. Student’s mean comparison test was used to evaluate the influence of factors potentially affecting our results. Gender, asthma or AERD, history and number of sinus surgeries, preoperative NPS, hypereosinophilia, cardiovascular history and diabetes were tested. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method to determine non-recurrence. The log-rank test was performed to evaluate the influence of factors potentially affecting recurrence.

Results

Seventy-five patients were included in our study (male to female ratio = 3.1). Two patients were lost to follow-up. The duration of follow-up ranged from 1 to 41 months. The percentage of patients with a minimum follow-up of 36 months was 82.2%.

Main outcome measurements

The main characteristics of the population are reported in Table II. APPS is mainly indicated in patients with severe and difficult-to-treat CRSwNP combined with high corticosteroid use. Most patients (92%) used daily nasal lavages and corticosteroid nasal sprays, while only 2.7% used nasal lavages alone.

Table II.

Patient characteristics.

| Number (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male/Female | 56 (74.7%) | 19 (25.3%) | |

| Asthma | 35 (46.7%) | ||

| AERD | 20 (26.7%) | ||

| Previous sinus surgery | 45 (60%) | ||

| Diabetes | 6 (8%) | ||

| Cardiovascular diseases | 27 (36%) | ||

| Chronic obstructive Pulmonary disease | 3 (4%) | ||

| Anti-coagulant therapy | 3 (4%) | ||

| Antiplatelet therapy | 10 (13.3%) | ||

| Hypereosinophilia Y/N/not tested | 18 (24%) | 20 (26.7%) | 37 (49.3%) |

| Preoperative NPS (Highest score of both nasal cavities) | 1 | 1 (1.33%) | |

| 2 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 7 (9.33%) | ||

| 4 | 67 (89.33%) | ||

| Number of previous ESS | 0 | 30 (40%) | |

| 1 | 17 (22.7%) | ||

| 2 | 16 (21.3%) | ||

| 3 | 4 (5.3%) | ||

| 4 | 3 (4%) | ||

| 5 | 4 (5.3%) | ||

| 6 or more | 1 (1.3%) | ||

| Yearly SCT (1 mg/kg): ≤ 2 week/year / > 2 week/year | 29 (38.7%) | 46 (61.3%) | |

AERD: Aspirin Exacerbated Respiratory Disease; NPS: Nasal Polyp Score; ESS: Endoscopic Sinus Surgery; SCT: Systemic Corticosteroid Therapy.

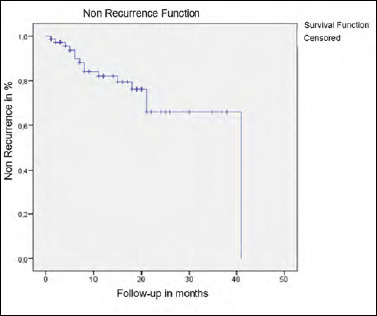

Duration of effectiveness (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve of non-recurrence after APPS. X-axis represents the number of months of postoperative follow-up. Y-axis represents the percentage of non-recurrence. Each step corresponds to a recurrence, each vertical line corresponds to a last news date.

Mean time to nonrecurrence was 31.3 ± 2.38 months. Sixty-six percent of patients were recurrence-free at 36 months after APPS. History of asthma and ESS were associated with a lower duration of effectiveness (26.88 ± 3.37 vs 33.38 ± 1.97 and 27.22 ± 3.24 vs 31.84 ± 2.11 months, p = 0.04 and p = 0.017, respectively).

We found a significant improvement between pre- and postoperative NPS (3.87 ± 0.45 vs 1.59 ± 0.66; p < 0.001). The difference between pre- and postoperative NPS was significantly greater in surgery-naïve patients (p < 0.05) and those with more severe polyposis (preoperative NPS = 4/4, p = 0.006).

Secondary outcome measurements

PREMs

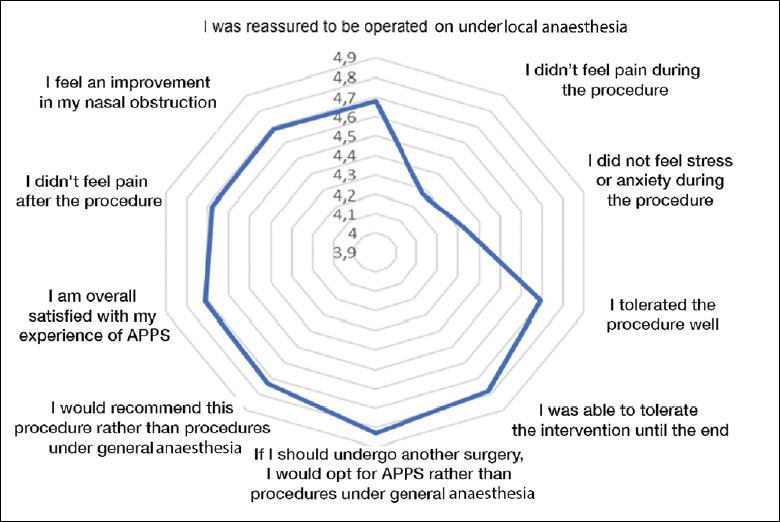

The APPS questionnaire was analysed in 59 patients (Fig. 2). The mean APPS score was 46.37/50 ± 5.54. 84.7% of the patients were reassured about being operated on without GA. The procedure was well tolerated in 88.1% of cases. 91.5% of patients did not experience any postoperative pain and would prefer APPS if they had to undergo another surgery. Two items, intraoperative pain and stress, showed slightly lower satisfaction rates. The mean score in response to the statement “I did not feel any pain during the procedure” was 4.27/5 and the mean score regarding the statement “I did not feel any stress or anxiety during the procedure” was 4.32/5, whereas mean scores to other questions ranged from 4.70 to 4.83/5. No factor studied herein influenced the APPS score.

Figure 2.

Graphical presentation of mean APPS score. Values range from 3.9 to 4.9/5 for better visibility.

PROMs

Nasal obstruction VAS was significantly improved after APPS (9.51 ± 1.68 vs. 0.97 ± 1.79; p < 0.001). Patients with a history of polypectomy without previous ethmoidectomy had significantly better improvement than patients with a history of ethmoidectomy (-9.09 ± 1.04 vs -7.87 ± 2.96; p = 0.05).

Olfactory disorders VAS was significantly improved after APPS (4.96 ± 0.26 vs 3.86 ± 1.76; p < 0.001). AERD, diabetes, hypereosinophilia, and high preoperative NPS were associated with poorer smell recovery (all p < 0.01).

COMPLICATIONS

No procedure had to be stopped early. Sixty-two patients (82.67%) had no complications. Two patients (2.67%) had major complications (one blood inhalation only requiring monitoring (1 night stay and discharge) and one nasal bleeding requiring rehospitalisation).

Eight patients had minor complications (10.6%). Seven (9.3%) had local superinfection requiring bacteriological sampling and a new antibiotic therapy. One (1.33%) had a vagal malaise.

Discussion

New findings

The objective of this study was to clarify APPS indications and duration of effectiveness in CRSwNP. Our study included 60% of patients with a prior history of surgery and/or excessive systemic use of corticosteroids (Tab. II). APPS was safe with a mean duration of effectiveness greater than 2 years and a satisfactory patient experience. Recurrence rates were comparable to surgeries performed under GA, although our population included patients with poor prognosis. These new data argue in favour of full integration of APPS in the management of CRSwNP. As a reliable procedure, APPS could be an alternative to systemic corticosteroid therapy, whose overuse can be harmful to patients.

Comparison with literature data

Like most studies in the literature, we reported a predominance of males and a strong association with asthma (46.7%) 5. However, our population was 10 to 20 years older, probably because APPS is usually performed in frail patients for whom GA would be contraindicated (e.g. cystic fibrosis). Compared with the literature, our population had higher rates of ESS (60% vs 30% to 50%) 6 and AERD history (26.7% vs 10% to 15%) 7,8. In addition, we observed a very high use of systemic corticosteroids. These points reflect the severe and difficult-to-treat condition of patients included in this study. Indeed, a history of ESS, asthma and AERD have been shown to be risk factors for earlier recurrence 9.

Despite this, we reported a mean duration of effectiveness of approximately 2.5 years. This finding could be underestimated given the limited follow-up of the study. A prospective study with a longer follow-up would allow more accurate results. In the literature, recurrence rates one year after ESS under GA range from 20 to 80% 10,11. Hopkins et al. reported 11% of surgical revisions 36 months after ESS 12. Other authors have shown 78.9% of recurrences within 12 years with 36.8% of patients requiring revision surgery 11,13.

The improvement of olfactory disorders could be surprising because APPS does not always clear ethmoidal corridors and olfactory clefts and postoperative treatment in our protocol does not include systemic corticosteroids. However, this improvement remained inferior to results obtained with the usual procedures under GA (-1.1/10 vs -3.31/10) 14. AERD, hypereosinophilia, high preoperative NPS and diabetes were associated with poorer recovery of smell, in agreement with the literature 15.

APPS appeared to be safe since the major complication rate (2.67%) was substantially lower than rates reported for surgery under GA (12.5 to 20%) 9.

Patient-related experience

One of the strengths of our study lies in the analysis of PREMs 16. Our questionnaire showed a high degree of satisfaction since more than 90% of patients expressed a preference for APPS over GA if they had to be re-operated on. Anxiety and intraoperative pain were the main patient concerns. In future, these findings could be further improved by optimising the logistics of surrounding surgery, especially with the development of an office-surgery department providing relaxing activities (hypnotherapy, virtual reality headsets, relaxing music) and analgesic and anxiolytic premedication. Many studies have shown the benefits of using such tools during APPS 17. In our experience, it is rare that patients refuse APPS and prefer surgery under GA.

Financial considerations

In Europe, the annual cost of managing a patient with severe CRSwNP is € 1570 18. The literature has shown the economic interest of office-surgery 19. In our department, the estimated cost of an APPS procedure is €876. Given its long-lasting effectiveness, APPS is therefore less expensive compared with surgery under GA (between $8 and $16,000), which is less expensive than biological therapies 20,21.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study lies in the retrospective aspect of the data collection and the inadequate follow-up time for optimal assessment of procedural effectiveness. We acknowledge that recurrence rate is difficult to define in a population not followed prospectively. VAS was used for PROMs evaluation instead of validated scales (SNOT- 22, Sniffin’ Sticks tests) 22,23. Moreover, PROMs and NPS were systematically evaluated only one month after surgery and duration of effectiveness was subjectively assessed based on the surgeon’s opinion and patients’ complaints. VAS tend to underestimate objective improvements, especially with regard to smell disorders 14,24. The use of semi-objective measures such as Sniffin’ Sticks tests in future studies may improve our results.

Conclusions

By virtue of its duration of effectiveness, safety, tolerance and reasonable cost, APPS is an option in treatment of CRSwNP.

Acknowledgements

To Mr Thirion for statistics.

To Mr Morgan for linguistic assistance.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

CM: first author; TR: supervision; MP and PD: data collection; JM: validation.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Marseille) (protocol n. 2021-15).

The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant/patient for study participation and data publication.

Figures and tables

Funding Statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Bhattacharyya N, Villeneuve S, Joish VN, et al. Cost burden and resource utilization in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps. Laryngoscope 2019;129:1969-1975. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.27852 10.1002/lary.27852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price D, Shah S, Bhatia S, et al. A new therapy (MP29-02) is effective for the long-term treatment of chronic rhinitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2013;23:495-503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudmik L, Smith KA, Kilty S. Endoscopic polypectomy in the clinic: a pilot cost-effectiveness analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 2016;41:110-117. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.12473 10.1111/coa.12473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gan EC, Habib ARR, Hathorn I, et al. The efficacy and safety of an office-based polypectomy with a vacuum-powered microdebrider: Vacuum-powered microdebrider for nasal polyps. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2013;3:890-895. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.21198 10.1002/alr.21198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomassen P, Vandeplas G, Van Zele T, et al. Inflammatory endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis based on cluster analysis of biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;137:1449-1456.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1324 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrel R, Gardiner Q, Khudjadze M, et al. Endoscopic surgical treatment of sinonasal polyposis-medium term outcomes (mean follow-up of 5 years). Rhinology 2003;41:91-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nores J, Avant P, Bonfils P. Polypose naso-sinusienne. Evaluation de l’efficacité de la corticothérapie mixte, locale et générale, dans une série de 100 malades consécutifs avec un suivi de trois ans. Presse Méd 2000:1214-1216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radenne F, Lamblin C, Vandezande LM, et al. Quality of life in nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;104:79-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70117-X 10.1016/S0091-6749(99)70117-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Zhang Y, Gao Y, et al. Long-term outcomes of different endoscopic sinus surgery in recurrent chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and asthma. Rhinology 2020;58:126-135. https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin19.184 10.4193/Rhin19.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeConde AS, Mace JC, Levy JM, et al. Prevalence of polyp recurrence after endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis: polyp recurrence after ESS. Laryngoscope 2017;127:550-555. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26391 10.1002/lary.26391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calus L, Van Bruaene N, Bosteels C, et al. Twelve-year follow-up study after endoscopic sinus surgery in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis. Clin Transl Allergy 2019;9:30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-019-0269-4 10.1186/s13601-019-0269-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins C, Browne JP, Slack R, et al. The national comparative audit of surgery for nasal polyposis and chronic rhinosinusitis. Clin Otolaryngol 2006;31:390-398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01275.x 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker SS. Surgical management of polyps in the treatment of nasal airway obstruction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2009;42:377-385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2009.01.002 10.1016/j.otc.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kohli P, Naik AN, Farhood Z, et al. Olfactory outcomes after endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;155:936-948. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599816664879 10.1177/0194599816664879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiménez A, Organista-Juárez D, Torres-Castro A, et al. Olfactory dysfunction in diabetic rats is associated with miR-146a overexpression and inflammation. Neurochem Res 2020;45:1781-1790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-020-03041-y 10.1007/s11064-020-03041-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingsley C, Patel S. Patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures. BJA Education 2017;17:137-144. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaed/mkw060 10.1093/bjaed/mkw060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray ML, Goldrich DY, McKee S, et al. Virtual reality as distraction analgesia for office-based procedures: a randomized crossover-controlled trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021;164:580-588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820942215 10.1177/0194599820942215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachert C, Zhang L, Gevaert P. Current and future treatment options for adult chronic rhinosinusitis: focus on nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:1431-1440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.010 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar S, Thavorn K, Katwyk S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of endoscopic polypectomy in clinic compared to endoscopic sinus surgery: a modelling study. Clin Otolaryngol 2020;45:477-485. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13533 10.1111/coa.13533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scangas GA, Wu AW, Ting JY, et al. Cost utility analysis of dupilumab versus endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Laryngoscope 2021;131:e26-e33. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28648 10.1002/lary.28648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scangas GA, Remenschneider AK, Su BM, et al. Cost utility analysis of endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyposis: cost-utility analysis of ESS for CRS. Laryngoscope 2017;127:29-37. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26169 10.1002/lary.26169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan BK, Lane AP. Endoscopic sinus surgery in the management of nasal obstruction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2009;42:227-240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2009.01.012 10.1016/j.otc.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang RS, Su MC, Liang KL, et al. Preoperative prognostic factors for olfactory change after functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2009;23:64-70. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3262. 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seyed Toutounchi SJ, Yazdchi M, Asgari R, et al. Comparison of olfactory function before and after endoscopic sinus surgery. Iran J Otorhinolaryngol 2018;30:33-40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]