Abstract

Background:

Effective implementation of evidence-based prevention interventions in schools is vital to reducing the burden of drug use and its consequences. Universal prevention interventions often fail to achieve desired public health outcomes due to poor implementation. One central reason for suboptimal implementation is the limited fit between the intervention and the setting. Research is needed to increase our understanding of how intervention characteristics and context influence intervention implementation in schools to design implementation strategies that will address barriers and improve public health impact.

Methods

Using a convergent mixed methods design we examined qualitative and quantitative data on implementation determinants for an evidence-based health curriculum, the Michigan Model for HealthTM (MMH) from the perspective of health teachers delivering the curriculum in high schools across the state. We examined data strands independently and integrated them by investigating data alignment, expansion, and divergence.

Results

We identified three mixed methods domains: (1) Acceptability, (2) intervention-context fit, and (3) adaptability. We found alignment across data strands as teachers reporting low acceptability also reported low fidelity. The fit between student needs and the curriculum predicted fidelity (expansion). Teachers mentioned instances of poor intervention-context fit (discordance), including when meeting the needs of trauma-exposed youth and keeping updated on youth drug use trends. Teachers reported high adaptability (concordance) but also instances when adaptation was challenging (discordance).

Conclusions

This investigation advances implementation research by deepening our understanding of implementation determinants for an evidence-based universal prevention intervention in schools. This will support designing effective implementation strategies to address barriers and advance the public health impact of interventions that address important risk and protective factors for all youth.

Plain Language Summary

(1) What is Already Known About the Topic? While many evidence-based interventions (EBIs) exist to address key health issues among youth including substance use and mental health, few of these interventions are effectively implemented in community settings, such as schools. Notable multilevel barriers exist to implement universal prevention in schools. Researchers identify that misalignment between the intervention and the context is a key reason why many implementation efforts do not achieve desired outcomes. (2) What Does This Paper Add? This paper combines the strengths of qualitative and quantitative research methods to identify and understand challenges to intervention-context fit for a comprehensive health curriculum, the Michigan Model for HealthTM (MMH) which is widely adopted throughout Michigan, from the perspective of end users. This paper also utilizes the consolidated framework for implementation research and implementation outcomes framework to guide our understanding of implementing complex interventions and key barriers to implementation in schools. This research provides a foundation to design effective strategies that will balance curriculum fidelity and adaptation to achieve public health objectives. (3) What are the Implications for Practice, Research, or Policy? We need implementation strategies that guide flexibility and fidelity in EBI delivery in schools. While overall teachers felt the curriculum was adaptable and met student needs, they also mentioned specific instances when they would benefit from additional implementation support, such as making adaptations to meet the needs of trauma-exposed youth and keeping up-to-date with emerging drugs. Implementation strategies designed to address these challenges can improve fidelity and ultimately student well-being.

Keywords: prevention, substance use, adolescence, school health, implementation science, mixed methods

Background

School-based interventions offer a unique opportunity to reach large populations of youth, including those underserved in other settings (e.g., clinical settings; Lee & Gortmaker, 2018). The field of prevention science has made notable gains in developing evidence-based interventions (EBIs) that address cross-cutting risk and protective factors for substance use and related outcomes including mental health (Dusenbury et al., 2003). Universal or Tier 1 health interventions, that is for all students regardless of risk level, have demonstrated efficacy in preventing or delaying the onset and escalation of drug use, and improving youths’ overall well-being (Durlak et al., 2011; Dusenbury et al., 2003; Herrenkohl et al., 2019). Yet, few EBIs are implemented with sufficient fidelity to achieve desired health outcomes due to a range of barriers across levels of influence (Herlitz et al., 2020; U.S. Department of Education, 2011; Wolfenden et al., 2022).

One central reason for poor implementation is limited intervention-context fit (Eisman et al., 2021; Lyon & Bruns, 2019b). Interventions rarely fit “off the shelf” and adaptations are frequently needed to meet population needs and priorities, and contextual challenges (Aarons et al., 2011; Chambers et al., 2013). Although traditional approaches to EBI implementation view adaptation as incongruent with fidelity, others suggest adaptation is essential to implementation success (Baumann et al., 2018; Hogue et al., 2013).

Changing an EBI to fit the context, however, can either enhance or diminish intervention effectiveness depending on if it is fidelity-consistent or inconsistent (Stirman et al., 2013). We define fidelity as the “effective implementation of core intervention elements (Allen et al., 2018, p. 267).” Core elements or functions, considered central to effectiveness, relate to intervention activities’ purpose and how activities work to produce desired outcomes (Kirk et al., 2019). Peripheral or form elements represent possible activities or methods (e.g., role-playing) to achieve the core functions (e.g., skill building; Stirman et al., 2013). Researchers collaborating with implementers can help support the inevitable EBI adaptations that occur in real-world settings using participatory approaches such as community-based participatory research (Minkler et al., 2018).

While various interventions exist, effective prevention curricula share common characteristics. One such curriculum is the Michigan Model for Health™ (MMH), a theoretically-based, comprehensive, skills-focused intervention that has demonstrated efficacy in reducing substance use and improving mental health outcomes in randomized controlled trials (O’Neill et al., 2011; Shope et al., 1996). Based on the Health Belief Model (HBM) (Champion & Skinner, 2008) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) (Bandura, 1989), MMH addresses developmentally appropriate cognitive, attitudinal, and contextual factors related to health behaviors. As a universal intervention, MMH is designed for all youth and addresses cross-cutting developmental risks and protective factors. MMH is also aligned with Michigan and National Health Education standards (CDC, 2018). The core functions of MMH are grounded in underlying theory (e.g., SCT, HBM) and consistent with those described by Boustani et al. (2015) and include addressing key predictors of health behaviors including attitudes, norms, social influences, with a focus on building skills (e.g., problem-solving, communication) and opportunities to apply and practice these skills and building positive social relationships. Standard MMH implementation includes a curriculum manual, foundational training, and as-needed technical assistance from the state's network of regional school health coordinators. Widely adopted throughout Michigan, 91% of high school health teachers use MMH, but 17%–29% (varying by grade level), deliver 80% or more of the curriculum, the state-identified fidelity standard (Rockhill, 2017).

Despite ongoing challenges with fidelity monitoring and measurement researchers have found a robust link between fidelity and youth outcomes in schools (Botvin et al., 2018; Dane & Schneider, 1998; Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Ringwalt et al., 2010). Thus, a gap remains between what we know works and how to effectively translate these findings into routine practice for school-based EBIs (Botvin et al., 2018). Understanding the dynamic relationship between the intervention, the context, fidelity, and adaptation is central to designing effective implementation strategies (see Figure 1). Implementation strategies are techniques or methods to enhance the implementation of EBIs (Proctor et al., 2013). A comprehensive understanding of implementation can aid in designing strategies that will mitigate key barriers experienced in practice.

Figure 1.

Factors that influence fidelity and adaptation, adapted from Allen et al., 2018. aAcceptability of the Michigan Model for HealthTM (MMH) intervention from teachers’ perspectives.

Mixed methods designs use qualitative and quantitative approaches to better understand complex issues (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). While mixed methods are central to implementation research, they have been underutilized to study implementation in educational settings. Mixed methods are especially useful for examining intervention characteristics, within the context of implementation; qualitative methods are useful for understanding the context, while quantitative methods are well suited to examining the intervention and implementation outcomes (Palinkas et al., 2011). Bringing quantitative and qualitative strands together permits us to obtain new insights that are beyond those of a single strand (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

To support effective implementation, however, our research efforts would also benefit from considering other implementation outcomes relevant to EBIs and providers’ perceptions of them (Weiner et al., 2017). Previous research points to the central role of acceptability in other outcomes, including fidelity (Eisman et al., 2021). Assessing acceptability, the perception that an intervention is satisfactory or agreeable can inform why an EBI or its implementation does (or does not) fit with implementers’ preferences (Proctor et al., 2011; Weiner et al., 2017). Acceptability may also be important as it is more proximal to intervention-level characteristics than other outcomes such as dose (Lyon & Bruns, 2019a).

The Present Study

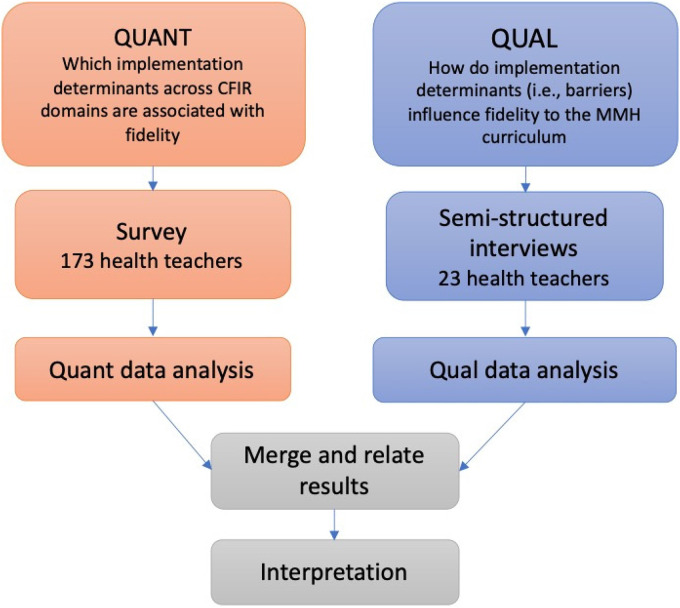

We used a convergent mixed methods design (see Figure 2) to obtain a comprehensive understanding of MMH delivery. This included intervention-context fit, and examining its relationship to adaptation and fidelity. We apply the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) as our overarching framework because it identifies determinants, that is factors that enable or inhibit effective implementation across levels of influence (Damschroder et al., 2009; Nilsen & Bernhardsson, 2019). CFIR is a comprehensive framework with five multilevel domains: intervention, outer setting, inner setting, individuals’ characteristics, and process, which influence EBI delivery (Damschroder et al., 2009). We also apply the Implementation Outcomes Framework to guide our discussion of implementation outcomes, including dose delivered (a fidelity dimension; Proctor et al., 2011). We focus on intervention-setting fit, that is alignment between the intervention and inner and/or outer setting factors, as key determinants (Lyon & Bruns, 2019b). Key determinants are factors that are especially consequential to implementation success or failure (Powell et al., 2019).

Figure 2.

Convergent mixed methods design.

We collected qualitative and quantitative data concurrently (see Figure 2), analyzed each independently, then merged the data and directly compared the quantitative and qualitative findings. We investigated how the results of each strand related to each other. Specifically, we identified the areas where the qualitative and quantitative findings converged to support the findings of each strand, and where they diverged to suggest a more nuanced understanding of EBI implementation. Our research questions were as follows:

What is the relationship between implementation determinants, specifically characteristics of the intervention, the setting (intervention-context fit), and implementation outcomes (e.g., acceptability, fidelity/dose delivered)? (Quantitative).

How and why does intervention-setting fit influence acceptability and the balance between fidelity/dose delivered and adaptation? (Qualitative).

What is the alignment between each strand of data (qualitative and quantitative) and how do qualitative results elaborate on quantitative results? (Mixed).

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Study procedures have been described elsewhere (Eisman et al., 2020, 2021), but are reviewed briefly here. We recruited high school health teachers throughout Michigan, in cooperation with the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services and their state-wide network of School Health Coordinators. School Health Coordinators are professionals who promote the health and well-being of students and families using evidence-based approaches. Health Coordinators work with school districts and teachers in their assigned regions (multiple adjacent counties) to support the implementation of health-focused interventions, such as providing MMH training and technical assistance. Coordinators in all 83 Michigan counties contacted high school health teachers in their regions; the exact number of recruitment messages sent out is unknown, however, every health teacher in the state with a valid email address was sent the recruitment information. Health teachers received an email that included a short study description and a link to the online survey. One-hundred ninety-nine potential participants responded by clicking on the link and completed a screening survey to ensure that they met the following criteria: (1) Be 18 years of age or older, (2) work with high school students/in a high school building, and (3) teach high school-level health classes. After screening out ineligible respondents, 171 participants completed the full research survey.

At the end of the survey, participants were offered an opportunity to participate in semistructured interviews. Research staff contacted interested participants and conducted interviews virtually, using video conferencing software. Twenty-three teachers participated in the interview portion of the study. Interviews lasted approximately 30 min, were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. We collected survey data from October to February 2018 and interview data in January and February 2018. Participants received remuneration for the survey and interview ($10 and $20 gift cards, respectively). We obtained consent before the survey administration and the semistructured interview. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Measures

A central feature of a convergent mixed methods design, to draw mixed methods inferences or meta-inferences, is to have a unifying theoretical or conceptual framework for both strands of data (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). The umbrella frameworks, in this case, CFIR and the Implementation Outcomes Frameworks, guide all the measurement instruments, analyses of each strand, and the integration of results from both strands of data (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). We describe each measurement instrument in the following section.

Survey

Fidelity

We assessed fidelity as dose delivered, a self-report measure asking the amount of the curriculum delivered. We utilized this dimension as our measure of fidelity as it is consistent with other evaluations of MMH (Rockhill, 2017) and has been identified by MMH practitioners as a key fidelity dimension. Teachers were asked what proportion of the MMH curriculum they delivered, for each of the six core units: Skills; Social and Emotional Learning; Nutrition and Physical Activity; Safety; Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Prevention; and Personal Health and Wellness. The ordinal response scale was from 0 = none to 4 = 75% or more, in 25% increments. We calculated each teacher's fidelity score as the mean dose delivered across these six core units.

Acceptability

We measured intervention acceptability, an implementation outcome, using four items based on intervention domains described in the CFIR, assessing teachers’ satisfaction with curriculum materials. Teachers were asked to what extent they agreed with the following statements using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree): (1) MMH lessons are easy to teach, (2) MMH rubrics/checklists are helpful, (3) MMH lessons are engaging for students, (4) MMH includes relevant/up-to-date information. These items were based on implementer knowledge and beliefs about an intervention from the CFIR framework (Damschroder et al., 2009). Cronbach’s alpha for these items was 0.73. We used their mean as a single acceptability score for each participant.

Student Needs (Outer Context)

We assessed student needs using one item developed for this study based on CFIR, “MMH meets the needs of high school students” using a 5-point Likert scale.

Adaptability (Intervention Characteristic)

We assessed adaptability using one item based on CFIR, “I can make changes to MMH if needed to make the intervention work effectively in my setting” using a 5-point Likert scale.

Teacher Interview

We used a semistructured interview guide focused on understanding how implementation determinants influence MMH fidelity (in this case, dose delivered). Questions were adapted from the CFIR interview guide and selected to match the specific domains included in the teacher survey (2014). We included questions that addressed intervention characteristics including teachers’ assessment of curriculum materials and adaptations to the program. We also included questions about the context, namely, student needs (See Table 1 for sample questions). In addition to the primary questions, interviewers asked follow-up probes to ensure comprehensive responses. We also asked teachers several multidomain questions for example, “Can you tell me about some challenges to using MMH or other health curricula?”

Table 1.

Data Sources: Matching the Survey Constructs With the Interview Guide Questions

| Quantitative sources | Qualitative sources |

|---|---|

| Intervention characteristics | |

| Satisfaction with packaging/curriculum materials How would you rate material resources (e.g., Michigan Model for HealthTM [MMH] curriculum materials) for MMH? 1: Significant Barrier to 5: Significant Asset |

Curriculum materials (packaging)

|

| Adaptability I can make changes to MMH if needed to make the intervention work effectively in my setting. 1: Strongly disagree to 5: Strongly agree |

Adaptations

|

| Context (outer setting) Student needs MMH meets the needs of high school students. 1: Strongly disagree to 5: Strongly agree |

Student needs

|

Note. Adapted from Fetters (2020)

Quantitative Data Analytic Approach

We examined quantitative survey data using Stata 16 (StataCorp), including univariate and bivariate statistics, to investigate possible variation in factors related to implementation guided by CFIR and their association with dose delivered. The type of correlation was determined by the scale of the variables: polyserial correlation if one variable was ordinal and the other continuous, and Pearson correlation if both were continuous (Cohen et al., 2003; Kaiser & Lacy, 2009; Olsson et al., 1982). Previous research suggests that the dose delivered can be examined as continuous because it meets a parallel regression assumption (Long, 1997), that is, the distance between categories is equivalent (see Eisman et al., 2020); therefore, we treated this variable as continuous in bivariate analyses.

Qualitative Data Analytic Approach

A more detailed description of the qualitative data analysis process can be found elsewhere (Eisman et al., 2021) so we review it only briefly here. Our process included the following steps: (1) Developing an initial codebook; this was based on the overarching CFIR and the implementation outcomes framework, (2) using an inductive approach to expand and build upon the deductive codes, (3) reviewing the codes (inductive and deductive) for consensus, resolving disagreements, and developing an inductive-deductive themed codebook, and (4) finalizing the thematic representation specific to factors related to the dose delivered.

First, three study team staff with graduate-level training in qualitative methods reviewed transcript material to develop a broad understanding of content, make initial notes and define the boundaries of the a priori codes (e.g., the inclusion and exclusion criteria) based on CFIR and the implementation outcomes framework. Second, we utilized an inductive approach to build upon and expand the deductive codes. Next, we assigned codes to segments of text based on a priori or emergent themes (Corbin & Strauss, 2008). We derived emergent themes or sub-codes through inductive open coding (Ritchie et al., 2003). The research team designated coding segments by starting when teachers began discussing a topic, and stopping when they changed to a new topic (Fusch & Ness, 2015). Two coders initially consensus-coded all segments from a subset of four transcripts, one at a time. In instances of disagreement, team members continued refining definitions for codes or adding inclusion/exclusion criteria in the codebook to describe the code boundaries to improve the agreement. The two analysts coded the data collaboratively until, as recommended by Miles and Huberman (1994) at least 80% agreement was achieved (4 interviews). The analysts coded the data independently for the remaining 19 interviews. We assessed drift by checking with 10% of each transcript together (Bakeman & Gottman, 1997) and conferring with each other when ascribing a code to a given piece of text was unclear. We resolved any further disagreement through consensus discussion with the principal investigator. We reached a consensus on those codes that needed consultation or were discrepant in coder drift.

Our thematic analysis focused on identifying the implementation determinants aligned with CFIR constructs, most frequently mentioned and/or widely endorsed, and relevant to the dose delivered. To analyze the factors, we extracted all segments identified by our determinant codes (i.e., CFIR domains) that were congruent with constructs measured in the survey. We identified thematic relationships between key determinants and outcomes described in each segment. We used a code co-occurrence matrix analysis tool in a qualitative software program (DeDoose) to identify CFIR factors that were coded with implementation outcomes. We then calculated the percentage of interview participants who endorsed each thematic relationship to assess the relative salience of the theme. We report qualitative results guided by the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (Tong et al., 2007), by including quotations from multiple participants, identifying major and minor themes, and supporting these with data.

Alignment Between Quantitative and Qualitative Data (Mixed)

Our mixed methods analysis focused on comparing results and evaluating the data for (1) concordance: findings confirming each other; (2) expansion: findings expanding and having overlap; and (3) discordance: findings in conflict or disagreement with each other (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018; Palinkas, 2014). We connected quantitative and qualitative data by matching survey items with interview questions (as in Table 1) and created a joint display to facilitate meta-inferences. This allowed us to deductively and inductively derive conclusions when combining data sources (Plano Clark & Ivankova, 2016). We merged results from the quantitative and qualitative analyses through a process of spiraled comparison: going back and forth, and cyclically considering results from both strands of data to merge and enhance the findings (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Results

Our sample included approximately 21% of all certified high school health teachers in Michigan according to a state database (Center for Educational Performance and Evaluation: CEPI, see Table 2). The teaching experience was symmetrically distributed, with 29% of participants at 10 years or less, 40% between 11 and 20 years, and 28% at more than 20 years. The social demographics of our sample were largely representative of the social demographics of high school health teachers across the state (see Table 2). We had 58 of 83 counties in the state represented in the sample (13% of participants did not report their county). Forty-one participants (24%) indicated their interest in participating in a semistructured interview; all were contacted and 23 responded to schedule the interview. We conducted interviews with 23 participants (13%; 26% male), who had somewhat less teaching experience than the complete sample (mean = 7.36 years). Demographics for the interview subsample are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic Data: State Data, Survey Sample, and Study Sample

| Race/ethnicity | Michigan health teachersa (population: number, proportion) | Study survey teachers (sample: number, proportion) | Study interview teachers (interview subsample: number, proportion) |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 7 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Asian | 1 (0.07%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Black | 55 (4.3%) | 7 (4%) | |

| White | 1190 (93.9%) | 160 (94%) | |

| Latino/a | 12 (0.9%) | 4 (2%) | |

| Total | 1266 | 171 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 606 (48%) | 99 (57%) | 17 (74%) |

| Male | 660 (52%) | 74 (43%) | 6 (26%) |

| Total | 1266 | 173 | 23 |

| Teaching Experience | |||

| < 5 | 376 (29%) | 15 (9%) | 4 (20%) |

| 5 −10 years | 172 (13%) | 35 (21%) | 5 (21%) |

| 11–15 years | 216 (17%) | 32 (19%) | 5 (21%) |

| 16–20 years | 257 (20%) | 40 (23%) | 5 (21%) |

| 20 + years | 259 (21%) | 49 (28%) | 3 (16%) |

| Total | 1280 | 171 | 22b |

Note. aData from the Center for Educational Performance and Information.

One interview teacher did not report.

Our survey results indicated that most teachers (89%) were below the state-identified standard of dose of 80% of the curriculum delivered (M: 2.34/4, SD: 1.18). Qualitative and mixed-methods analyses provided an informative picture of how acceptability, intervention-setting fit, and adaptability influenced health teachers’ curriculum dose delivered. Table 3 summarizes the results from each analysis approach.

Table 3.

Joint Display of Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods Metainferences for the Study Domains

| Mixed methods domains | Qualitative findings | Quantitative findings | Mixed methods meta-inferences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability |

Summary

Teacher perceptions about the acceptability of MMH were closely associated with behaviors to deliver the curriculum with fidelity. Acceptability refers to the degree to which teachers perceived an intervention as agreeable or satisfactory. Example quotes “I think that some lessons and materials are great, and then others I just don't feel like actually really are that great for…high schoolers…Sometimes I’d rather give them…more information that's not (in the curriculum).” “I (use other resources because) found the redundancy in (content and activities) turned students away, and it turned the group of students away who needed it most.” |

MMH packaging ratings/satisfaction: Mean = 3.58 (max 5), SD = 0.075 Bivariate analysis with fidelity: Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.42, p < .01 Quantifying qualitative data: ¼ of acceptability codes also coded for fidelity |

Concordance

If teachers were not satisfied with the curriculum/low acceptability, they would veer from the curriculum or abandon it altogether, resulting in lower fidelity. Barrier/facilitator: Acceptability, a perceptual implementation outcome, is associated with fidelity and can be a barrier or facilitator. |

| Intervention-setting fit |

Summary

Teachers reported challenges with the curriculum meeting the needs of students, a dimension of the outer setting in CFIR. While teachers shared that the curriculum has many strengths, identified two issues related to student needs: (1) Keeping up with new and emerging drug use issues and (2) addressing the needs of students exposed to trauma, specifically youth exposed to ACEs. Students exposed to trauma Example quotes “A lot of our students have interrupted educational experiences. They just aren't at that point where some of the things (in the curriculum), they were (not) even capable of doing.” “(The curriculum and) training that we received sometimes didn't correlate to what we could use in the classroom (given the student population)…some of it wasn't received well (by students).” |

The curriculum meets student needs: 19%

disagree/SD, 20% neutral, 61% agree/SA

Bivariate analysis with fidelity: Polyserial, Rho = 0.39, SE = 0.07, p < .01 |

Expansion

One challenge to fidelity is a lack of fit between the curriculum and student needs. One need highlighted is trauma-informed approaches for youth exposed to ACEs. Discordance Over 60% of teachers felt the curriculum does a good job of meeting student needs, but interviews emphasized cases when it did not. Barrier/facilitator: Student needs were a barrier to curriculum fidelity in instances where there was not alignment- including trauma-informed approaches for youth exposed to ACEs. |

| Adaptability |

Summary Teachers report frequently adapting the

curriculum to fit their context, teaching style, and experience

level. Although they reported they feel free to adapt the

curriculum as needed, teachers report specific instances when

adaptation is challenging, particularly when trying to include

up-to-date drug use information and adapting the curriculum to

meet the needs of students exposed to trauma.

Example quotes “It doesn't really meet our needs… if you have to use it, it needs to be customized for your particular population.” “The time is the issue to be able to go through each individual step and to be able to pull out (or change what I need for my students).” |

Curriculum is adaptable: 3% disagree/SD, 10%

neutral, 86% agree/SA

Bivariate analysis with fidelity: Polyserial, Rho = 0.48, SE = 0.07, p < .01 |

Expansion Teachers overall felt the curriculum

is adaptable, and reported making changes based on the context,

teaching style, and teaching experience.

Discordance Teachers reported high adaptability, but qual results also revealed instances when adaptation is challenging. In particular, adapting the curriculum to the needs of students exposed to trauma. Barrier/facilitator: Results indicate that adaptability is a key determinant and potential barrier or facilitator to fidelity. |

Note. MMH = Michigan Model for HealthTM; ACE = adverse childhood experiences; CFIR = consolidated framework for implementation research.

Acceptability

The mean acceptability rating of 3.58/5 (SD = 0.75) indicated that health teachers were moderately satisfied with the curriculum. Acceptability was moderately associated with a higher dose (r = .42, p < .01). Qualitative findings revealed that teachers reported high acceptability for some intervention characteristics, such as specific engaging activities and lessons in the curriculum. One participant stated, “what I do use the most, is the engaging lessons … where it gets the whole class into it …” However, qualitative data on MMH acceptability revealed instances when teachers were not satisfied with the curriculum.

Teachers provided examples of scenarios in which students were not engaged or did not sufficiently relate to prescribed examples or activities. One teacher stated, “I feel like some of the activities or discussion points…don't really hit on (what) students really need. So I kinda go in a different direction or add supplemental materials in that way.” In these cases, supplementation or replacement of the content may constitute a lower dose delivered. One teacher said “(If) I just don't like the lesson … I just skip it, and I’ll do something else … I pick and choose what I use.” Another teacher mentioned, “I kept on modifying it (the curriculum), and modifying it, so I don't know how close I am to the curriculum anymore.” Using the data from our co-occurrence matrix, we found that approximately one-fourth of segments coded for acceptability were also coded for dose. Qualitative results were concordant with quantitative results in that teachers who reported low acceptability also reported making changes to the curriculum that may not have been consistent with the core functions.

Intervention-Setting Fit: Student Needs

Sixty-one percent of participants agreed or strongly agreed that MMH meets student needs. Similar to results for acceptability, teachers who felt more strongly that the curriculum met student needs were also likely to report greater dose delivered (Rho = 0.39, p < .01).

Teachers who were interviewed described challenges with meeting the needs of specific groups of students. Teachers expressed that more was needed, for example, to meet the needs of youth exposed to trauma, marginalization, and socioeconomic disadvantage. Meeting student needs, an outer setting factor in the CFIR, is vital to achieving the objectives of Tier 1 EBIs. Some teachers shared that they felt, that while the curriculum has many strengths, it is written for “suburban white students.” In reference to trauma and other adversity, teachers mentioned the following:

A lot of our students have interrupted educational experiences. They just aren't at that point where some of the things (in the curriculum), they were (not) even capable of doing.

(The curriculum and) training that we received sometimes didn't correlate to what we could use in the classroom (given the student population) … some of it wasn't received well (by students).

Teachers also reported that addressing current and emerging drug issues is a priority. They mentioned that their students often were personally experiencing and/or affected by drug use, abuse, and dependence. One teacher stated, “We really want to focus in on the topics that really matter to these kids … Like what drugs are students using … Where we’re at now, heroin is getting to be very big. (And our county) has several deaths every year (due to heroin in) the closest big city to us. That really hits home for the kids.” Consequently, teachers felt that addressing relevant and timely health issues is vital to meeting student needs.

Adaptability

Our survey results indicated that 86% of teachers agreed or strongly agreed that the curriculum is adaptable, and in the bivariate analysis, we found that teachers’ perceptions of curriculum adaptability were positively associated with dose (Rho = 0.48, SE = 0.07, p < .01).

The qualitative findings offered a more nuanced picture of curriculum adaptability. Teachers reported frequently adapting the curriculum to fit their setting, teaching style, and experience level. One teacher remarked, “I would say a lot of us teachers take little parts of the Michigan Model and some lessons, but then skip other lessons and add in our own information, or because of the amount of time we have (or other things we want to include).” Another mentioned, “being a teacher as long as I have, there's a lot of times I don't need a … script and I can change things on the fly if it's not working … I can change things up a little bit.”

Although they reported freedom to adapt the curriculum as needed, teachers also reported specific instances when adaptation was challenging, as with trauma. One teacher said, “So I’ve really had to change how I teach this stuff because it's gone from students learning about (traumatic events) to students (who are) living with (traumatic events).”

Teachers also reported specific challenges with updating the content to address the rapidly changing nature of drug use among youth and the notable time it takes to address the most pressing and relevant issues. One teacher mentioned, “We got pretty big drug problems, so we’re hoping to kind of figure out where (the information we need) is, where our holes are (in the curriculum) so we can address those needs.”

Overall we found some convergence in quantitative and qualitative data results on teachers’ positive perceptions of curriculum adaptability. But interviews revealed specific situations in which adaptation was more challenging, including addressing student trauma exposure and rapidly changing patterns in drug use.

Discussion

In this study, we used mixed methods to expand our understanding of implementation determinants associated with a school-based Tier 1 EBI. Specifically, we examined the fit between the intervention and the context and its relationship to dose delivered and adaptation from the perspective of the implementers, high school health teachers. We examined mixed methods domains, guided by CFIR and the implementation outcomes framework, including acceptability, intervention-context fit, and adaptability that, by combining qualitative and quantitative data strands, permits additional insights beyond each strand alone (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

The health teachers in our study reported that they are often not implementing the MMH curriculum consistently according to state-identified standards of fidelity (i.e., dose delivered). While our quantitative measure of dose delivered is consistent with other MMH research, it only includes one fidelity dimension. Our qualitative results revealed a more nuanced picture of fidelity, including adherence. Teachers who were interviewed described several ways in which they alter or deviate from the curriculum due to limited intervention-context fit and reduced acceptability, which influence, for example, dose delivered and/or adherence. Yet, our results are consistent with other research indicating that implementers (i.e., teachers) face barriers across fidelity dimensions and levels of influence that likely contribute to implementation challenges that can compromise achieving desired health objectives (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; U.S. Department of Education, 2011). Given that MMH is a widely adopted EBI, our results provide clear evidence that MMH and similar interventions would benefit from a systematic investigation of barriers related to intervention-context fit to design implementation strategies that will mitigate barriers and promote fidelity to core components (see Figure 3 for examples).

Figure 3.

Example of how the current study results can inform selecting suitable implementation strategies to address key implementation barriers, using the first components of the Implementation Research Logic Model adapted from Smith et al. (2020) and using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Damschroder et. al., 2009)-Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC; Powell et al., 2015) implementation strategy matching tool.

Quantitative and qualitative results taken together indicate that acceptability can be a barrier or facilitator. Teacher perceptions about MMH acceptability were closely associated with dose. This finding is consistent with Lyon and Bruns (2019a) who assert that implementation outcomes focused on intervention perceptions are a critical predictor of behavioral implementation outcomes such as fidelity; if teachers are not satisfied with the curriculum, then they will be less likely to deliver components as intended. Thus, to enhance fidelity, strategies need to focus on mitigating barriers that reduce acceptability. Health teachers indicate that, when delivering MMH, it is important to address intervention characteristics that lower relatability and student engagement; that is, fit with the student needs.

We found that student needs are a barrier to fidelity in instances where there was limited alignment between the intervention and the outer setting. Consideration of student needs is central to interventions that seek to improve outcomes such as drug use (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Teachers highlighted specific areas of misalignment between the EBI and the setting. We found discordance when integrating qualitative and quantitative data, as over 60% of teachers felt the curriculum does a good job of meeting student needs, while interviews emphasized specific cases when they did not. Two specific issues mentioned were meeting the needs of youth exposed to trauma and keeping the information in the curriculum current for drug use prevention; this is consistent with a recent systematic review that identified meeting student needs and keeping curriculum materials current as key barriers to effective implementation and sustainment of public health interventions in schools (Herlitz et al., 2020).

Although the curriculum meets the needs of many students, it may not meet the needs of some. These results underscore the need for implementation strategies to facilitate EBI responsiveness for specific populations including those at risk of poor health outcomes due to marginalization, trauma, and socioeconomic disadvantage. Promoting adaptability, is defined as ways an intervention can be “adapted to best fit with the school/classroom context, meet local needs, and clarify which elements of the new practice must be maintained to preserve fidelity (Cook et al., 2019, p. 922)”, for example, is a promising strategy; it can provide structure for fidelity-consistent adaptations to address the needs and challenges of the setting. These results also highlight the importance of a developing area in implementation science: health equity (Baumann & Cabassa, 2020). Implementation strategies that explicitly address intervention-setting fit and meet the needs of trauma-exposed youth are essential to mitigating health disparities in the consequences of trauma exposure. These consequences include substance abuse, substance use disorders, and poor mental health outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019). Strategies such as providing tailored implementation support (e.g., facilitation) for fidelity-consistent adaptations, and community collaboration (see Figure 3), can support achieving public health objectives including health equity (Ringwalt et al., 2010).

Another need mentioned by teachers was current health information for students, specifically related to drugs. Teachers cited that the curriculum “can't keep up with the drugs.” Drug use trends among youth change over time, and sometimes quickly (Johnston et al., 2018). To meet this need, teachers report frequently diverting from the curriculum in order to find and share updated and relevant substance use information for their students. Teachers felt that having the most current drug use data, emerging trends, and new modes of administration are vital to engaging students, addressing their concerns, and, ultimately, meeting their needs. Deploying strategies such as developing and distributing educational materials to supplement the curriculum content can support teachers in addressing timely drug use issues (see Figure 3). This can support effective implementation as teachers are unlikely to deliver a curriculum with fidelity if they do not feel it engages students and meets their needs (Herlitz et al., 2020).

Overall, teachers described the curriculum as adaptable. Adaptability, according to the CFIR framework, refers to the extent to which an intervention can be refined or tailored to meet population needs (Damschroder et al., 2009). Although teachers reported high adaptability, qualitative results revealed instances when adaptation is challenging, such as meeting the needs of trauma-exposed students and addressing current drug use issues most relevant to youth. Unfortunately, many (if not most) behavioral interventions have been developed by researchers without sufficient consideration of the end-users and intervention recipients (Lyon & Bruns, 2019a). Our results highlight the need to design strategies that address this limitation, promote fidelity-consistent adaptations and collaborate with practitioners in tailoring EBIs for their setting. We found that an adaptable curriculum can be a potent facilitator for fidelity. Thus, it is critical to design implementation strategies that focus on fidelity and adaptation, not as competing but as complementary features. Fidelity and adaptation can co-exist as complementary features of intervention when maintaining core EBI components that are critical to its effectiveness (Lyon & Bruns, 2019b; Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2019). Promoting MMH adaptability may include retaining, the focus on key predictors of health behaviors including attitudes, norms, and social influences, with a focus on building skills (e.g., problem-solving, communication), and providing specific guidance on alternative activities to accomplish these objectives. Monitoring and evaluating core components may also be suitable to support assessing the extent to which core functions are preserved.

Results from this research underscore the importance of designing and deploying implementation strategies for optimizing school-based EBIs to achieve their highest public health impact. Our results suggest that multiple implementation strategies may be needed to address intervention-context fit, improve acceptability, and support an effective fidelity-adaptation balance. As this area of research continues to emerge, tailoring the strategies and combinations of strategies, and assessing their hypothesized mechanisms of action, will be important to continue moving the field of implementation science forward (Lewis et al., 2018). In addition, careful documentation of core components, adaptations, and their implications on implementation and participant outcomes will advance our understanding of balancing fidelity and adaptation to optimize EBI impact (Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2019).

Limitations

While findings revealed important considerations for implementation science, this study had some important limitations. Our study examined the implementation of one specific EBI (MMH) in a single Midwestern state. Barriers to implementation may be specific to this sample and may not fully generalize to other geographic regions or evidence-based curricula. This sample may not be representative of all health teachers. Additionally, due to our recruitment method, we were unable to identify the number of teachers originally approached and thereby calculate the response rate. Our quantitative measure of fidelity included only one dimension, dose delivered; our qualitative results revealed other important dimensions of fidelity, such as adherence, that were not quantitatively measured and thus not fully addressed in the mixed method analysis. As acceptability emerged as an important implementation outcome, the quantitative strand of the research would have benefitted from utilizing current established measures such as Acceptability of Intervention Measure, Intervention Appropriateness Measure, and Feasibility of Intervention Measure by Weiner et al. (2017). We were able to obtain qualitative data only from a subsample of the larger survey, and this subsample may not have been fully representative of the larger sample. Numerous methods to estimate intercoder reliability are available, and although this area of qualitative research is evolving and the best approach is debated, other methods of calculating ICR may also be useful (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). Finally, other implementation science frameworks, such as the FRAME, would be useful in deepening our understanding of EBI modifications and the extent to which they are fidelity-consistent or inconsistent (Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2019).

Conclusions

This study addresses current gaps in implementation science by exploring determinants, that is types of factors that either enable or inhibit effective intervention implementation, including those related to intervention-context fit, for school-based Tier 1 prevention. This work can provide a foundation for systematically designing effective implementation strategies that will enhance fidelity and ultimately youth outcomes. A vital next step is applying these results to designing and testing implementation strategies that support fidelity-consistent adaptations and thus support acceptability for users in the long run. As currently many adaptations to MMH and other EBIs are made reactively, and the level to which they are fidelity-consistent is unknown; implementation strategies can provide much-needed support and scaffolding to engage in adaptations that enhance versus diminish intervention effectiveness (Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2019).

Our results also suggest the need for implementation strategies to support the responsiveness of interventions and delivery systems to changing trends. Drug use trends change rapidly among adolescents, yet schools and other organizations engaged in prevention efforts struggle to respond quickly and effectively to these changing trends. Stemming the onset and rapid escalation of drug use requires swift responses. Methods for optimizing EBIs to systematically respond to current trends are needed to prevent drug use and addiction in real-world settings. For the field of implementation, science to have a greater “real-world” impact it needs to be more rapid, iterative, and work within the timeframes of youth-serving systems (Glasgow et al., 2020; Glasgow & Chambers, 2012). Thus, implementation strategies that focus on facilitating rapid responsiveness are needed to stem the onset and escalation of drug use trends that become popular and spread quickly among youth.

Deepening our understanding of implementation determinants using mixed methods is useful for informing implementation strategies that mitigate barriers and can be applied to other school-based EBIs, with a focus on balancing adaptation and fidelity in EBI delivery. Systematically designing implementation strategies based on these insights regarding barriers can support implementable, EBIs that balance fidelity to core functions and adaptations to the setting.

Footnotes

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Palinkas is an Associate Editor for Implementation Research and Practice. As such, he did not participate in any part of the peer review process for this manuscript. The remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health (K01 DA044279) and the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (UL1TR002240).

Ethical Approval: All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Informed Consent: The authors obtained consent from participants before the survey administration and the semistructured interview.

ORCID iD: Andria B. Eisman https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4100-6543

References

- Aarons G., Hurlburt M., Horwitz S. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38, 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J., Linnan L., Emmons K. (2018). Fidelity and its relationship to implementation effectiveness, adaptation, and dissemination. In R. Brownson, G. Colditz, & E. Proctor (Eds.), Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice (2nd ed., pp. 281–304). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman R., Gottman J. (1997). Observing interaction: An introduction to sequential analysis (2nd ed). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann A., Cabassa L. (2020). Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Services Research, 20(190), 9. 10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann A., Cabassa L., Stirman S. (2018). Adaptation in dissemination and implementation science. In Brownson R., Colditz G., Proctor E. (Eds.), Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice (2nd ed., pp. 285–300). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin G., Griffin K., Botvin C., Murphy M., Acevedo B. (2018). Increasing implementation fidelity for school-based drug abuse prevention: Effectiveness of enhanced training and technical assistance. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 9(4), 599–613. 10.1086/700972 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boustani M. M., Frazier S. L., Becker K. D., Bechor M., Dinizulu S. M., Hedemann E. R., Ogle R. R., Pasalich D. S. (2015). Common elements of adolescent prevention programs: Minimizing burden while maximizing reach. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(2), 209–219. 10.1007/s10488-014-0541-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (2018, November 29). Characteristics of an Effective Health Curriculum. CDC Healthy Schools. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/sher/characteristics/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- CFIR Research Team (2014). CFIR interview guide tool. http://www.cfirguide.org/guide/app/index.html#/.

- Chambers D., Glasgow R., Stange K. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science : IS, 8(1), 117. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion V., Skinner C. (2008). The health belief model. In Glanz K., Rimer B. K., Viswanath K. (Eds.), Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice (4th ed., pp. 45–66). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Cohen P., West S., Aiken L. (2003). Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (pp. xxviii, 703 p.). L. Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cook C., Lyon A., Locke J., Waltz T., Powell B. (2019). Adapting a compilation of implementation strategies to advance school-based implementation research and practice. Prevention Science, 20(6), 914–935. 10.1007/s11121-019-01017-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., Strauss A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J., Plano Clark V. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (Third Edition., Vol. 1–xxvii). Sage, [2018]. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L., Aron D., Keith R., Kirsh S., Alexander J., Lowery J. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(50), 1–15. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dane A. V., Schneider B. H. (1998). Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review, 18(1), 23–45. 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00043-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J., DuPre E. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3), 327–350. 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J., Weissberg R., Dymnicki A., Taylor R., Schellinger K. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusenbury L., Brannigan R., Falco M., Hansen W. (2003). A review of research on fidelity of implementation: Implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research, 18(2), 237–256. 10.1093/her/18.2.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisman A., Kilbourne A., Greene D., Walton M., Cunningham R. (2020). The user-program interaction: How teacher experience shapes the relationship between intervention packaging and fidelity to a state-adopted health curriculum. Prevention Science, 21(6), 820–829. 10.1007/s11121-020-01120-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisman A., Kiperman S., Rupp L., Kilbourne A., Palinkas L. (2021). Understanding key implementation determinants for a school-based universal prevention intervention: A qualitative study. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 12(3), 411–422. 10.1093/tbm/ibab162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetters M. (2020). Performing fundamental steps of mixed methods data analysis. In Fetters M. (Ed.), The Mixed Methods Workbook (pp. 180). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch P., Ness L. (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 20(9), 1408–1416. 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R., Battaglia C., McCreight M., Ayele R., Rabin B. (2020). Making implementation science more rapid: Use of the RE-AIM framework for mid-course adaptations across five health services research projects in the veterans health administration. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 1–13. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R., Chambers D. (2012). Developing robust, sustainable, implementation systems using rigorous, rapid and relevant science. Clinical and Translational Science, 5(1), 48–55. 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00383.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitz L., MacIntyre H., Osborn T., Bonell C. (2020). The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 15(1), 4. 10.1186/s13012-019-0961-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl T., Hong S., Verbrugge B. (2019). Trauma-informed programs based in schools: Linking concepts to practices and assessing the evidence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(3–4), 373–388. 10.1002/ajcp.12362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A., Ozechowski T. J., Robbins M. S., Waldron H. B. (2013). Making fidelity an intramural game: Localizing quality assurance procedures to promote sustainability of evidence-based practices in usual care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20(1), 60–77. Scopus. 10.1111/cpsp.12023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (2001). Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press (US). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L., Miech R., O’Malley P., Bachman J., Schulenberg J., Patrick M. (2018). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use: 1975-2017. Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser J., Lacy M. (2009). A general-purpose method for two-group randomization tests. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 70–85. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0900900105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk M., Haines E., Rokoske F., Powell B., Weinberger M., Hanson L., Birken S. (2019). A case study of a theory-based method for identifying and reporting core functions and forms of evidence-based interventions. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(1), 21–33. 10.1093/tbm/ibz178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R., Gortmaker S. (2018). Health dissemination and implementation within schools. In Brownson R., Colditz G., Proctor E. (Eds.), Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice (2nd ed., pp. 401–416). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C., Klasnja P., Powell B., Lyon A., Tuzzio L., Jones S., Walsh-Bailey C., Weiner B. (2018). From classification to causality: Advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 1–6. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long J. (1997). Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables (Vol. 1–xxx, 297 p.). Sage Publications; U-M Catalog Search. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon A., Bruns E. (2019a). User-Centered redesign of evidence-based psychosocial interventions to enhance implementation—hospitable soil or better seeds? JAMA Psychiatry, 76(1), 3. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon A., Bruns E. (2019b). From evidence to impact: Joining our best school mental health practices with our best implementation strategies. School Mental Health, 11(1), 106–114. 10.1007/s12310-018-09306-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M. B., Huberman A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M., Salvatore A., Chang C. (2018). Participatory Approaches for Study Design and Analysis in Dissemination and Implementation Research. In Brownson R., Colditz G., Proctor E. (Eds.), Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Research to Practice (2nd ed., pp. 175–190). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P., Bernhardsson S. (2019). Context matters in implementation science: A scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 189. 10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor C., Joffe H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. 10.1177/1609406919899220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson U., Drasgow F., Dorans N. (1982). The polyserial correlation coefficient. Psychometrika, 47(3), 337–347. 10.1007/BF02294164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J., Clark J., Jones J. (2011). Promoting mental health and preventing substance abuse and violence in elementary students: A randomized control study of the Michigan Model for Health. Journal of School Health, 81(6), 320–330. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas L. (2014). Qualitative and mixed methods in mental health services and implementation research. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43(6), 851–861. 10.1080/15374416.2014.910791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas L., Aarons G., Horwitz S., Chamberlain P., Hurlburt M., Landsverk J. (2011). Mixed method designs in implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(1), 44–53. 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plano Clark V., & Ivankova N. (2016). Mixed Methods Research: A Guide to the Field. Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483398341 [Google Scholar]

- Powell B., Fernandez M., Williams N., Aarons G., Beidas R. S., Lewis C., McHugh S., Weiner B. J. (2019). Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: A research agenda. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 1–9, 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B. J., Waltz T. J., Chinman M. J., Damschroder L. J., Smith J. L., Matthieu M. M., Proctor E. K., Kirchner J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation science, 10, 1–14, 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Powell B., McMillen J. (2013). Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Science : IS, 8(1), 139. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A., Griffey R., Hensley M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringwalt C. L., Pankratz M. M., Jackson-Newsom J., Gottfredson N. C., Hansen W. B., Giles S. M., Dusenbury L. (2010). Three-year trajectory of teachers’ fidelity to a drug prevention curriculum. Prevention Science, 11(1), 67–76. 10.1007/s11121-009-0150-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J., Spencer L., O'Connor W. (2003). Carrying out qualitative analysis. In Richie, J., & Lewis, J. (Eds.), Qualitative Research Practice (pp. 219–262). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill S. (2017). Use of the Michigan Model for Health Curriculum among Michigan Public Schools: 2017. Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, Lifecourse Epidemiology and Genomics Division, Child Health Epidemiology Section. [Google Scholar]

- Shope J., Copeland L., Maharg R., Dielman T. (1996). Effectiveness of a high school alcohol misuse prevention program. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 20(5), 791–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05253.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J., Li D., Rafferty M. (2020). The implementation research logic model: A method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implementation Science, 15(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s13012-020-01041-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirman S., Miller C., Toder K., Calloway A. (2013). Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science, 8(1), 65. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education (2011). Prevalence and Implementation Fidelity of Research-Based Prevention Programs in Public Schools: Final Report (ED-00-CO-0119). U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, Policy and Programs Study Service. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. J., Lewis C. C., Stanick C., Powell B. J., Dorsey C. N., Clary A. S., Boynton M. H., Halko H. (2017). Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Science, 12(1), 108. 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltsey Stirman S., Baumann A., & Miller C. (2019). The FRAME: An expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science, 14(1), 58. 10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfenden L., McCrabb S., Barnes C., O'Brien K. M., Ng K. W., Nathan N. K., Sutherland R., Hodder R. K., Tzelepis F., Nolan E., Williams C. M., Yoong S. L. (2022). Strategies for enhancing the implementation of school-based policies or practices targeting diet, physical activity, obesity, tobacco or alcohol use. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8(8), CD011677. 10.1002/14651858.CD011677.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]