Abstract

Background:

Decades of war, famines, natural disasters, and political upheaval have led to the largest number of displaced persons in human history. The refugee experience is fraught with obstacles from preflight to resettlement, leading to high rates of mental distress including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. However, there is a paucity of mental health services for refugees in transit. To meet the needs of this vulnerable population, researchers are experimenting with teaching lay community members basic tools for the delivery of mental health and psychosocial support services (MHPSS). However, there are research gaps about the use of implementation science to inform the delivery of applicable interventions, especially within low resource settings, and even less in the humanitarian context.

Methods:

This review utilizes an implementation science framework (RE-AIM) to assess the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of these interventions. Studies included varying interventions and modes of delivery within refugee camp and urban settings. A comprehensive search strategy led to the inclusion and analysis of 11 unique studies.

Results:

While current research documents adaptation strategies, feasibility, and fidelity checks through routine monitoring, there is still a dearth of evidence regarding capacity building of lay providers in humanitarian settings. Barriers to this data collection include a lack of homogeneity in outcomes across studies, and a lack of comprehensive adaptation strategies which account for culture norms in the implementation of interventions. Furthermore, current funding prioritizes short-term solutions for individuals who meet criteria for mental illnesses and therefore leaves gaps in sustainability, and more inclusive programming for psychosocial services for individuals who do not meet threshold criteria.

Conclusion:

Findings contribute to the literature about task-shifting for MHPSS in humanitarian contexts, especially illuminating gaps in knowledge about the lay counselor experiences of these interventions.

Plain language summary:

There is a growing number of refugees forced to make homes in temporary camps or urban centers as they await resettlement, a process that can last decades. These refugees are at risk of serious mental health outcomes due to ongoing stress and trauma. One strategy commonly used in global mental health is the training of lay providers to deliver basic mental health and psychosocial programming to communities. While this tactic is currently being tested in refugee settings, there is limited evidence about the implementation of this strategy. The following scoping review aims to assess the implementation of task-shifting interventions within refugee settings, through the use of a robust implementation science framework.

Keywords: Task shifting, scoping review, psychosocial intervention, international

There are 25.9 million refugees worldwide, 80% of whom are hosted in countries neighboring their countries of origin (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 2020). Approximately 57% of refugees are from Syria, Afghanistan, and South Sudan, with growing numbers from Myanmar (UNHCR, 2020). Therefore, the majority of refugees are enduring protracted displacement in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). LMIC are often under-resourced, with minimal opportunities for economic mobility, overcrowded schools, and insufficient health care systems (World Bank, 2018).

The associations between exposure to conflict and poor mental health outcomes such as complicated grief, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety is well established (Ahearn, 2000; Çeri & Özer, 2018). The impact of trauma and compounded stressors have been found to be moderated by loss of relatives and support networks, lack of basic health needs, displacement, parental psychopathology, and socioeconomic adversity often exacerbated in refugee settings (Boothby et al., 2006). There has been progress toward the recognition of refugee psychological needs and the integration of mental health responses in complex humanitarian settings. However, the majority of LMIC do not have the capacity to support burgeoning refugee populations. Often, refugees rely on non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that provide mental health services based on short-term grants, with ongoing challenges to program maintenance after the intervention period (Shiras, 1996; UNHCR, 1994).

In addition, help-seeking behaviors for refugees experiencing psychological distress may be more limited when compared to the general population (Bean et al., 2006). Due to several barriers such as cultural and linguistic difficulties, lack of information, understanding public systems, cost, and stigma, people may not be able to access support in their new environments, even when they are actively seeking it (Sullivan & Simonson, 2016). Moreover, interventions have only recently begun to move away from individualized trauma-focused approaches to the provision of culturally adapted community-based services. Culturally adapted services include the integration of cultural idioms of distress, which are culturally specific ways of experiencing and communicating emotional suffering that do not fit into the categories of Western nosologies (Cork et al., 2019; Desai & Chaturvedi, 2017). Through the engagement of community members, interventions can more accurately gauge feasibility, adaptations, implementation, and evaluations of program components for more sustainable programs and outcomes (Castillo et al., 2019; Padmanathan & De Silva, 2013).

Task shifting or task sharing, involving the training of non-specialized lay community members in key intervention tasks, is employed universally for improved mental health outcomes but has not been empirically reviewed in the humanitarian context (Feiring & Lie, 2018; Hoeft et al., 2018). Task shifting has proven to be a highly effective strategy in low resource settings, primarily involving the training of community health workers to deliver mental health and psychosocial support interventions. Task shifting is an effective method to reduce the burden of disease and mental health disparities for underserved populations (Barnett, Gonzalez, et al., 2018; Barnett, Lau, et al., 2018; Galvin & Byansi, 2020; Mutamba et al., 2013; Singla et al., 2017). In addition, evidence in LMIC has shown that proper education, supervision, and community partnerships can improve the implementation of task-shifting programs (Hoeft et al., 2018; Shahmalak et al., 2019). However, the nuances of implementing a task-shifting intervention with refugees in LMIC are largely unknown. It is important to note the differences in mental health and psychosocial support services (MHPSS) delivery among displaced persons compared to host populations in LMIC. Protracted displacement, related fracturing of social systems, ongoing psychosocial stress and traumatization, and care provision delivered from humanitarian actors such as NGOs potentially complicate the implementation of task-shifting interventions in humanitarian settings (Crawford et al., 2015; Dickson & Bandpan, 2018; Siriwardhana & Stewart, 2013).

The aim of this scoping review is to consolidate literature on the development, deployment, and effectiveness of mental health and psychosocial support interventions (MHPSS) delivered by lay providers (people who are not formally trained as mental health professionals through tertiary educational institutions) for refugees who are living outside of their countries of origin, within LMIC. Populations living outside of their countries of origin were included in this review due to the nature of psychosocial stressors associated with living in a new environment, including language and cultural differences with their host communities. MHPSS is used to describe the range of activities that are used to treat mental disorders and improve the psychological and social well-being of individual and communities affected by conflict or disaster (Meyer, 2013). For the purposes of this study, the relevant disorders and concerns addressed in MHPSS programming will be limited to common mental disorders (CMD) including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and suicidal ideation.

Conceptual framework

To guide this analysis, the RE-AIM (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance) framework (Glasgow et al., 2019) was utilized. RE-AIM was developed to guide accurate process recording to achieve better understanding of complex interventions (Harden et al., 2015). Examples of RE-AIM dimensions we examined are as follows: reach (e.g., number and demographics of community members participate in intervention, if they are representative of the overall sample), effectiveness (e.g., if the intervention achieved its proposed outcomes), adoption (e.g., the development of organizational support to deliver the intervention, and the representative nature of the people adopting the intervention), implementation (e.g., training, supervision, fidelity checks, adaptations during implementation, assessments of feasibility and acceptability by program staff, and space utilization), and maintenance (e.g., long-term effects of program outcomes and potential sustained programming). Implementation science frameworks such as RE-AIM are especially crucial to guide the development and implementation of programs in low resource settings, due to limited infrastructure for complex projects. While the population of refugees in the world have been growing, interventions to meet the psychological and social needs of these populations are limited and their processes remain nebulous. To scale up effective programs, transparent process recording must be included throughout program management, through the use of an implementation science framework.

Methods

The purpose of the review is to generate a more complete understanding of the implementation of task-shifting MHPSS programs in humanitarian settings. The methodology for this scoping review was based on the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley and improved by others (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Peters et al., 2015; Tricco et al., 2018). The review included the following five key phases: (1) define the research question, (2) identify relevant studies, (3) select studies, (4) chart the data, and (5) collate, summarize, and report the results. The optional “consultation exercise” of the framework was conducted during the final phase of data synthesis.

Review questions

This scoping review utilizes exiting research about task-shifting approaches to MHPSS program delivery in humanitarian settings to answer the following questions:

How do programs address equity in reach through sampling and recruitment methods?

Are interventions that engage lay counselors effective?

How can programs be adapted and adopted in local contexts?

What tools are used to ensure task-shifting approaches are implemented successfully?

How can maintenance of MHPSS programming be addressed in humanitarian settings?

Search strategy

Using a comprehensive search strategy, a medical librarian searched the literature for records including the concepts of refugees, asylum seekers, displaced persons, LMIC, mental health, psychosocial support, trained teachers, and community health workers (see Supplemental Appendix). The librarian created search strategies using a combination of keywords and controlled vocabulary in Embase.com 1947–, Ovid Medline 1946–, Scopus 1823–, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL Plus) 1937–, Ebsco Global Health 1973–, and Ebsco APA PsycINFO 1600s–. All search strategies were completed February 18, 2020 with no added filters or limits to find a total of 268 results. A total of 91 duplicate records were deleted after using the de-duplication processes described in “De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote” (Bramer et al., 2016), resulting in a total of 174 unique citations included in the project library.

Inclusion criteria

For the purpose of this review, we selected research based on the following criteria:

Studies that describe, and evaluate the effect of, mental health and psychosocial support interventions for individuals affected by conflict. The term MHPSS is used to describe any type of support that aims to protect or promote psychological well-being and/or prevent or treat CMD.

Studies that involve people currently living in LMIC, outside of their countries of origin. This includes refugees or asylum seekers living in both urban and camp-based settings.

Studies that involved training and utilizing lay community members as counselors in the intervention strategy.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies that had not been sufficiently documented to evaluate fit with inclusion criteria. Usually, this meant that the counselor recruitment criteria, training, and support were not adequately documented. In addition, all studies specifically developed to prevent and treat serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were excluded from the review. Studies that included internally displaced persons (IDPs) who remained in their countries of origin or those who had resettled in high-income countries were excluded. We did not create exclusion criteria related to the quality of research design or measures of program effectiveness due to the limited use of universal effectiveness indicators across studies. Therefore, to make the review as comprehensive an array of programs as possible, we did not exclude studies with unclear effectiveness outcomes.

Data extraction and analysis

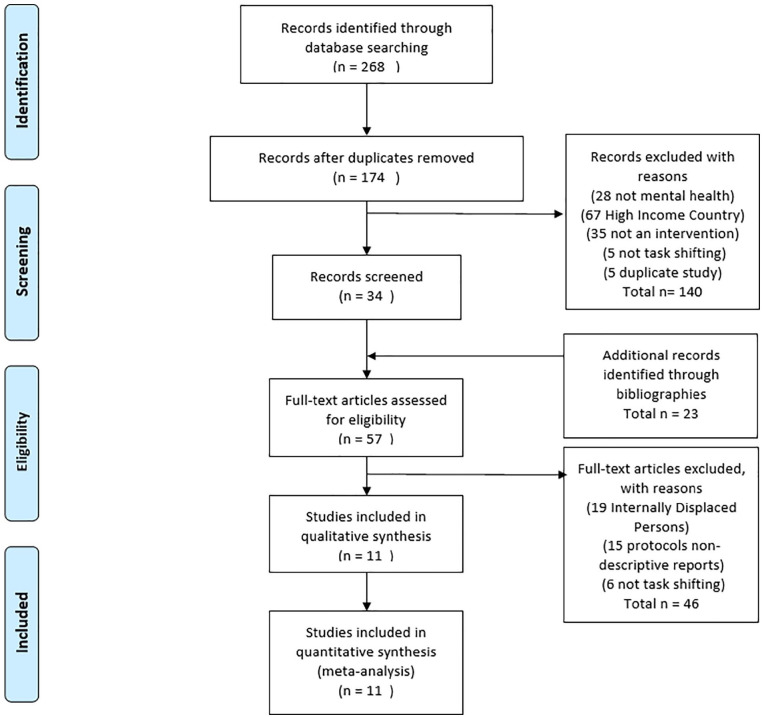

Following the database search, we screened the titles and abstracts for relevance and excluded records that did not meet the eligibility criteria in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009; Figure 1). Then, we screened full-text records for eligibility. Additional peer-reviewed articles and gray literature documents identified through hand searching were added to the body of texts. Data extraction included the specification of target groups and descriptions of interventions, treatment modalities, methodologies, counselor selection and training criteria, funding sources, and effectiveness outcomes if readily available. Once the final list of studies was compiled, we sought additional information about each program by manually searching the websites of the relevant organizations, other publications by the key authors, and contacted authors for additional findings. We reviewed all documents related to the selected programs and categorized them according to RE-AIM components for further analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Results

While included studies presented a range of activities and settings, there were no implementation science frameworks used in the articles. Therefore, findings for the purposes of this review are situated within the RE-AIM framework, to address key components and gaps in research findings. Reach was assessed through the demographics of key populations and sampling strategies for participants and counselors. Effectiveness was assessed through outcome data, primarily on mental health outcomes pre- and postinterventions. Adoption was measured through study setting adaptations to enhance program delivery, and the training, recruitment, and supervision of counselors. Implementation is about the interventions used in each setting including components of feasibility and acceptability, and maintenance is the collection of data about the ways in which programs were maintained after initial delivery.

Reach

Within the RE-AIM framework, reach refers to the representativeness of individuals who participate in a given program. To study this aim, we synthesized the data on sample populations and analyzed representation of key demographic characteristics. Relevant characteristics are outlined in Table 1. Studies included populations from Burma (Bolton et al., 2014; Tay et al., 2019; Sullivan et al., 2019; Tarannum et al., 2019), Somalia (Im et al., 2018; Murray et al., 2018; Neuner et al., 2008), Syria (Gormez et al., 2017), Palestine (Nakkash et al., 2012), Rwanda (Neuner et al., 2008), South Sudan (Tol et al., 2018), and Sri Lanka (Vijayakumar et al., 2017). These populations were living and accessing services in Uganda (Neuner et al., 2008; Tol et al., 2018), Bangladesh (Sullivan et al., 2019; Tarannum et al., 2019), Thailand (Bolton et al., 2014), Turkey (Gormez et al., 2017), Kenya (Im et al., 2018), Malaysia (Tay et al., 2019), Ethiopia (Murray et al., 2018), and India (Vijayakumar et al., 2017). Seven studies were conducted in camps, and four were in urban settings. Altogether, the research included 3,548 people, of whom the majority of participants were female (except for two studies where the gender ratios are unknown). Participant’s ranged in age due to the characteristics of the interventions (i.e., a school-based intervention targeted children, a youth-focused intervention targeted youth, etc.). Therefore, years of completed education and years living in host countries also varied considerably.

Table 1.

Intervention characteristics and adaptations..

| Citation and intervention | Level of evidence | Participant demographics | Location of intervention | Intervention information (component [C], dose [D]) | Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bolton et

al. (2014)

Individual CETA |

1 RCT |

347 participants Female: 63% Age: 35.6 years (mean) Education: 56% HS degree or higher Ethnicity: 63% Burman Eligibility criteria: witnessed or experienced a traumatic event and moderate to severe depression or PTSD |

Urban—Thailand Home of the client or counselor, local Burmese-run clinics, community organizations, or secluded outside areas |

C: Engagement, psychoeducation, anxiety management,

behavioral activation, cognitive coping/restructuring,

imaginal gradual exposure, in vivo exposure, safety, SBI for

alcohol D: unknown |

Preliminary adaptions to cultural idioms of distress and treatment. Family and friends were also invited to introductory sessions |

|

Gormez

et al. (2017)

Group CBT |

2 Program evaluation |

32 participants Female: 60% Age: 12.4 years (mean) Ethnicity: 100% Syrian Eligibility criteria: trauma-related psychopathology |

Urban—Turkey Temporary education centers (TEC) in the Fatih district of Istanbul |

C: cognitive restructuring, relaxation, psychoeducation,

trauma narrative, and problem-solving. D: 8-weekly 70–90 min sessions |

Cultural idioms of distress were utilized |

|

Im et

al. (2018)

Group TIPE |

2 Program evaluation |

141 participants 56% female Age: 20 years (mean) 48% elementary education or less 75% migrated from Somalia |

Urban—Kenya Local CBO run by Somali doctors, counselors, and community leaders |

C: psychoeducation, emotional coping, problem-solving,

community and support systems, conflict management

skills D: 12 sessions over 3 months |

Outcome measurements were adapted. Cultural idioms of distress used |

|

Tay et

al. (2019)

Individual IAT |

4 Field report |

115 Rohingya participants | Urban—Malaysia | C: Safety and Security, Attachments, Justice, Role and

Identities, Existential Meaning D: 6-weekly 45 min sessions |

Focus group discussion to assess the implementation outcomes |

|

Murray

et al. (2018)

Dyadic CETA |

2 Program evaluation |

37 participants Child Female: 44.44% Age: 11.21 years (mean) Caregiver Female: 82.6% Age: 41.24 years (mean) 100% from Somalia |

Camp—Ethiopia | C: (See above) D: 6–12 sessions depending on need. 60–90 min sessions with child and caregiver |

Matching local cultural idioms of distress |

|

Nakkash

et al. (2012)

Qaderoon (We are Capable) |

2 Program evaluation |

Six schools Age: 11–14 years Children from Palestine |

Camp—Lebanon Out of school hours but within a school building |

C: stress inoculation, social awareness, problem solving and

positive youth development D: 45 sessions (children), 15 sessions (parents), and 6 workshops (teachers) |

Feedback suggested scheduling with parents and schools |

|

Neuner

et al. (2008)

Individual NET, flexible trauma counseling (TC), and no-treatment monitoring group (MG) |

1 RCT |

NET (n = 111) Female: 50.5% Age: 34.4 years (mean) Ethnicity: 67.7% Somalian/32.3% Rwandan TC (n = 111) Female: 53.2% Age: 35.2 years (mean) Ethnicity: 46.8% Somalian/53.2% Rwandan MG (n = 55) Female: 49.1% Age: 35.6 years (mean) Ethnicity: 21.8% Somalian/79.1% Rwandan |

Camp—Uganda | C: NET: narrative account of traumatic experience. TC:

active listening, problem solving, exploration of coping

skills, and grief interventions D: NET six sessions (twice per week) between 1 and 2 hr each. TC as needed. |

Adapted outcome measures |

|

Sullivan

et al. (2019)

Individual Acupuncture and Relaxation |

2 Program evaluation |

46 households Female: 46% Age: 38 years (mean) Ethnicity: 100% Rohingya |

Camp—Bangladesh Community-based |

C: relaxation techniques (acupuncture, breathing

exercises) D: daily for 1 week |

Reflective discussion groups for feedback on the program |

|

Tarannum

et al. (2019)

mhGAP-HIG |

2 Program evaluation |

1,200 consultations delivered to Rohingya refugees. | Camp—Bangladesh Primary health care settings |

C: referrals for MHPSS services D: as needed |

More concise, adapted mhGAP for humanitarian settings |

|

Tol et

al. (2018)

SH+ Community Awarness |

1 RCT |

50 participants 100% female 29.5 years average age 100% South Sudanese |

Camp—Uganda Community-based |

C: psychological flexibility and referrals for additional

care D: Unclear |

Prior evaluations showed the need to adapt interventions for women |

|

Vijayakumar et al. (2017)

Individual CASP |

4 Surveys |

Intervention group (n = 639) Female: 60.7% Age: 41.58 (mean) Ethnicity: 100% Sri Lankan Control group (n = 664) Female: 56.2% Age: 39.1 (mean) Ethnicity: 100% Sri Lankan |

Camp—India Households |

C: coping strategies, contact numbers for supports, health

services, etc. D: periodic visits to provide emotional support to individuals |

FGDs to understand perceptions about suicidal behavior and attitudes toward the program |

CETA: common elements treatment approach; CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; TEC: temporary education centers; TIPE: trauma-informed psychoeducation; CBO: community-based organization; IAT: integrative adapt therapy; NET: narrative exposure therapy; TC: trauma counseling; MHPSS: mental health and psychosocial support services; SH+: Self Help+; CASP: contact and safety planning; RCT: randomized controlled trial, HS: high school, PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder, SBI: screening and brief intervention.

In addition, the methods used to recruit participants and counselors varied across studies. The majority of studies used convenience sampling techniques, including referrals, snowball sampling, and school-based samples to recruit participants (Gormez et al., 2017; Im et al., 2018; Murray et al., 2018; Nakkash et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2019). Three articles used household survey methods to recruit based on meeting criteria for mental illnesses (Neuner et al., 2008; Tol et al., 2018; Vijayakumar et al., 2017). Counselors were recruited through referrals, advertisements, or existing positions (through trainings for primary care staff members or teachers). This has implications for reach—as interventions should be tailored to the various aspects of individual demographics and livelihoods. In addition, recruitment primarily involved the inclusion of participants who met criteria for psychological distress, which presents a barrier for people who might not meet threshold criteria. Therefore, due to the sampling and recruitment methods, the reach for the included interventions was not sufficient to meet the needs of the sample populations.

Effectiveness

Interventions targeted various symptoms of mental distress and permutations of service delivery. Effectiveness refers to the impact of the intervention, including anticipated as well as unanticipated outcomes. Unfortunately, measurements for similar indicators of mental health were not uniform across studies to analyze differences in outcomes. Most studies aimed to improve symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD in addition to functional outcomes, related physical outcomes, and social well-being. Studies were effective in improving these outcomes both at 1- and 3-month evaluation periods. For example, following the group cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention, children’s anxiety decreased from a mean of 53.28 (SD = 13.78) on the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale to a mean of 40.38 (SD = 20.59) after 1 month (posttest). Additional results are available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pre- and postintervention scores on included measures.

| Author (year) | Intervention | Scale | Total (n) | Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | t or z statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gormez et al. (2017) | G-CBT | SCAS total | 32 | 53.28 (13.78) | 40.38 (20.59) | 3.73*** |

| CPTS-RI total | 30 | 23.9 (12.76) | 17.63 (13.64) | 2.72** | ||

| SDQ total | 31 | 18.77 (4.28) | 16.81 (5.41) | 2.44* | ||

| Im et al. (2018) | TIPE | PCL-C | 141 | 34.65 (13.02) | 33.65 (13.11) | 0.608 |

| Violence | 141 | 6.07 (4.51) | 5.75 (3.97) | 0.694 | ||

| Sense of community | 141 | 6.83 (3.69) | 8.19 (2.71) | −3.542*** | ||

| Emotional coping | 141 | 6.55 (3.15) | 7.13 (3.08) | −1.25 | ||

| Problem solving | 141 | 9.66 (4.09) | 10.13 (3.57) | −0.738 | ||

| Social support | 141 | 4.29 (2.56) | 5.04 (2.1) | −2.756** | ||

| Awareness | 141 | 6.87 (3.79) | 7.76 (3.75) | −2.01* | ||

| Murray et al. (2018) | CETA | Child | ||||

| CBCL/YSR: Internalizing | 37 | 25.73 (12.01) | 7.77 (10.14) | 8.35*** | ||

| CBCL/YSR: Externalizing | 37 | 13.63 (7.33) | 3.58 (5.31) | 4.96***, a | ||

| CPSS-1 | 37 | 20.84 (8.9) | 5.57 (5.89) | 10.39*** | ||

| Child well-being | 37 | 47.48 (15.98) | 62.72 (15.34) | 4.58*** | ||

| Caregiver | ||||||

| CBCL/YSR: Internalizing | 37 | 20.65 (8.26) | 8 (9.24) | 4.97***, a | ||

| CBCL/YSR: Externalizing | 37 | 16.41 (10.99) | 4.86 (7.02) | 4.63***, a | ||

| CPSS-1 | 37 | 21.19 (8.27) | 7.45 (9.55) | 5.17***, a | ||

| Neuner et al. (2008) | NET | PTSD symptoms | 111 | 25.9 (13.2) | 5.4 (6.6) | 1.4 |

| TC | PTSD symptoms | 111 | 26.7 (12.5) | 5.3 (5.7) | 1.5 |

SD: standard deviation; G-CBT: group cognitive behavioral therapy; SCAS: Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale; CPTS-RI: Child Post-Traumatic Stress–Reaction Index; SDQ: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; TIPE: trauma-informed psychoeducation; PCL-C: PTSD Check List–Civilian Version; CETA: common elements treatment approach; CBCL/YSR: Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist/Youth Self Report; CPSS-1: Child Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale-Interview format; NET: narrative exposure therapy; PTSD: score of posttraumatic stress symptoms; TC: trauma counseling.

Note: Sense of community, emotional coping, problem-solving, social support, and awareness measures used short (5-item) locally developed scales. PTSD refers to the score of posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Based on Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for non-normally distributed variables.

Significance values reported as *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Due to the heterogeneous nature of the included studies, findings varied. For example, one study aimed to build capacity among primary health care workers (Tarannum et al., 2019), while another aimed to improve suicide prevention mechanisms among community health workers (Vijayakumar et al., 2017). Most studies included elements of qualitative data collection to assess program satisfaction and improvements related to cultural idioms of distress, while quantitative measures were used to measure effectiveness outcomes using validated survey instruments. Overall, studies were effective in improving the recognition of CMD (Tarannum et al., 2019), decreasing suicides (Vijayakumar et al., 2017), decreasing PTSD symptoms, decreasing symptoms of depression, and improving overall well-being (Bolton et al., 2014; Gormez et al., 2017; Im et al., 2018; Murray et al., 2018).

Adoption

Adoption concerns the types, characteristics, and representativeness of settings that adopt the intervention. To assess adoption we addressed the ways in which study settings and organizations were invited and selected; however, this information was quite limited. While a couple studies were developed at the request of the implementing organization, the majority did not report the development of community partnerships for adoption of interventions.

The lay counselors who were adopting the interventions were primarily from within the refugee community themselves (111 lay counselors; Bolton et al., 2014; Im et al., 2018; Tay et al., 2019; Murray et al., 2018; Neuner et al., 2008; Sullivan et al., 2019; Tol et al., 2018; Vijayakumar et al., 2017), while the rest of the interventions included members from the host community or were unclear about the counselor demographics. To guide adoption, there were varying degrees of implementer training and supervision (Table 3). Trainings ranged from 90 min (Sullivan et al., 2019) to 6 weeks (Neuner et al., 2008). In addition, supervision ranged from daily to only if there is a high-risk case, for example, when someone expresses imminent suicidal ideation. In addition, while seven studies recruited lay counselors from within the community, and reported high levels of trauma exposure within the community, only one reported an assessment of mental health among lay counselors and the provision of treatment before program implementation.

Table 3.

Counselor training and supervision..

| Citation | Counselor characteristics | Counselor training (components [C], dose [D]) | Supervision (dose and duration) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bolton et al. (2014) | 20 Burmese refugee volunteers Female: 55% Age: 34 years (mean) Three male supervisors |

C: Apprenticeship model—case presentation, reviews of client

assessments and treatment plans, fidelity monitoring, roles

plays, and session planning. D: 10 days of in-person training. |

Practice groups with one supervisor per three to five

counselors. Each trainee treats one client with close

supervision before intervention. Each local supervisor met

with a small group of counselors for 2–4 hr per

week. Each supervisor received 2 hr per week of supervision with US-based CETA trainers by phone, internet, or email. |

| Gormez et al. (2017) | Arabic-speaking teachers | Two-day training | Hourly supervision meetings following each session |

| Im et al. (2018) | 25 youth leaders | C: conflict resolution, management skills, problem solving,

psychoeducation, and psychosocial competencies. D: 1 week TIPE TOT training. |

10 trained youth leaders were paired with five community health counselors to provide a peer-led intervention that consisted of 12 sessions over 3 months. |

| Tay et al. (2019) | 12 lay Rohingya counselors | C: theoretical and practical aspects of the intervention

(ADAPT (Adaptation and Development after Persecution and

Trauma) Pillars) D: 10-day training workshop facilitated by two clinical psychologists. |

6-month period of training and implementation. |

| Murray et al. (2018) | 19 counselors and 3 supervisors Inclusion criteria: fluent in Somali, good communication skills, and motivated. Experience working with children preferred but not required. Supervisors were staff from IRC (International Rescue Committee). |

C: Apprenticeship model—(see Bolton et al., 2014

above) D: 10 days of in-person training. |

6 months of weekly small group meetings with a local supervisor. Weekly virtual meetings were also held between each local supervisor and a CETA trainer for 1–2 hr |

| Nakkash et al. (2012) | Implementation team: 1 master trainer, 6 facilitators, and 23 youth mentors | C: stress inoculation, improving social awareness,

problem-solving, positive youth development. D: “intensive training” |

During the intensive summer session, daily meetings were held between the implementation team. Once the school year began meetings were held weekly. |

| Neuner et al. (2008) | Nine refugee volunteers Female: 56% Age: 27 years (mean) Inclusion criteria: English literacy, mother tongue literacy. Ability to empathize, and highly motivated. Three trainees had lifetime PTSD, and two had current PTSD. Those trainees received individual NET treatment as part of their education. |

C: general counseling and specific methods for the treatment

approaches. D: 6 weeks |

Trainee counselors were tutored under supervision for both approaches before beginning work. Case and personal supervision were still maintained thereafter on a weekly basis. |

| Sullivan et al. (2019) | 13 community health workers from within the camp | C: acupuncture and mindful breathing techniques D: 90-min group sessions with same-sex pairs |

Provided feedback following the intervention. |

| Tarannum et al. (2019) | 62 primary health care workers Inclusion criteria: staff who indicated interest in mental health, had work schedules that would allow for supervision, and were likely to stay long at their duty stations. |

C: psychoeducation, communication skills, human rights

protection, priority conditions, management of specific

priority conditions. Discussions, roles plays, case studies,

and video presentations. D: two 3-day trainings |

National psychiatrist visited each facility once every 2 weeks; she observed sessions and reviewed system support. Only 15 primary health care workers attended supervision regularly. A graduation model was used, which included assessments in various domains. |

| Tol et al. (2018) | Four volunteers Females: 100% Ethnicity: 100% Ugandan Inclusion criteria: Juba Arabic speaking, from the settlement area. |

C: psychoeducation, SH+, resource sharing. D: 4-day training |

Supervised weekly by a Ugandan social worker. |

| Vijayakumar et al. (2017) | Nine refugee volunteers Female: 100% Ethnicity: 100% Sri Lankan Inclusion criteria: willingness and ability to empathize while maintaining confidentiality of participants. |

C: communication skills, loss and grief, depression,

suicide, empathetic offering of support. D: 20+ hr training |

Volunteers inform their organization if there is imminent risk of suicide. |

CETA: common elements treatment approach; TIPE: trauma-informed psychoeducation; TOT: training-of-trainers; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; NET: narrative exposure therapy; SH+: Self Help+.

Implementation

Some programs like Contact and Safety Planning (CASP) and CETA (Common Elements Treatment Approach) were for individuals (adults or children), while CBT was delivered to groups of children, Trauma-Informed Psychoeducation (TIPE), Integrative Adapt Therapy (IAT), Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET), Trauma Counseling (TC), and Self Help+ (SH+) were delivered to groups of adults. Finally, the mhGAP is an organizational task-shifting intervention that was delivered at the point of accessing formal clinical care (compared to the other studies that utilized community-based mechanisms or at community-based organizations (CBOs). Interventions were delivered as needed/based on referrals (Bolton et al., 2014; Tarannum et al., 2019; Vijayakumar et al., 2017), or for set periods of time such as daily for 1 week (Sullivan et al., 2019) or 8-weekly sessions (Gormez et al., 2017). Fidelity to original programs was tested via video-recordings and subsequent analysis of sessions (Gormez et al., 2017), supervisors eliciting details from lay counselors and reviewing materials from in-session activities and homework (Bolton et al., 2014; Murray et al., 2018), and supervisors attending 10% of sessions (Tol et al., 2018).

The feasibility of included programs was assessed before program delivery in most settings. Some authors noted that they assessed feasibility through pre-implementation qualitative interviews with staff (Murray et al., 2018) and assessments of organizational resources (Tol et al., 2018). In addition, indicators of feasibility were assessed during and post-implementation, leading to adjustments in program protocol. For example, one program found that parents were barriers to children attending sessions at school because parents were prioritizing children preparing for exams, so the implementation team coordinated a more appropriate schedule with schools (Nakkash et al., 2012). Other examples of adaptations included adjustments to outcome measurements to include cultural idioms of distress and accounting for gender differences in appropriateness (Tol et al., 2018). For example, Tol et al. (2018) adapted the intervention method to be more accessible for male populations. Program acceptability was studied in a selection of studies, through assessments of participant and provider perspectives on the intervention method during the program pilot (Murray et al., 2018) and following implementation (Sullivan et al., 2019).

Maintenance

Maintenance refers to the long-term sustainability at both the setting and individual levels. To address sustainability, or the ability of the programs to continue to be delivered past the research intervention period, we analyzed capacity-building components of programs. Only one program utilized a training-of-trainers (TOT) method during implementation, but there was no investigation into the components of TOT other than preliminary training and supervision. While all studies included components of supervision during program implementation (primarily from the researchers), only one program measured knowledge and skill acquisition among counselors to allow for continued programming (Tarannum et al., 2019). Follow-up discussions with corresponding authors illuminated high rates of attrition among lay counselors due to the following reasons: lack of continued interest in psychosocial support, compassion fatigue, and the need for finding a job with consistent compensation. In addition, researchers reported barriers to capacity building due to lack of local government support for programming and difficulties acquiring ongoing funding.

Discussion

These studies present a complete overview of task-shifting programs being implemented in refugee settings within LMIC. Studies target most levels of the MHPSS pyramid (Inter-Agency Standing Committee [IASC], 2007), which includes (1) social consideration and basic services and security, (2) strengthening community and family supports, (3) focused (person-to-person) non-specialized supports, (4) specialized services provided by mental health professionals. Interventions recognized the utility of involving community members in intervention delivery because of their linguistic and cultural expertise. Each of the articles included in this review had specific strengths, including the documentation of adaptation strategies, testing feasibility, testing fidelity through routine monitoring and checklists, and other relevant aspects of implementation. However, while literature on MHPSS programming in humanitarian settings is burgeoning, documentation of the process of implementing task-shifting interventions is even more nascent. Existing literature addresses some key concepts of adaptation to local contexts through understanding the feasibility of interventions and barriers to adoption, but a strong analysis of the development, adaptation, and implementation of MHPSS interventions is still lacking.

Methodologically, there are some key barriers to synthesizing information across MHPSS interventions. The first of which is that it is difficult to develop rigorous experimental designs within these settings due to high staff turnover, the rapid migration of people (which effects retention), and ethical issues with withholding an intervention from a vulnerable population such as is the case with traditional randomized controlled trials (IASC, 2007). In addition, data analysis is difficult when outcomes are not uniform across studies. This is even more challenging because of the adaptations of outcome measurement tools to fit cultural idioms of distress. While inclusion of cultural idioms of distress is important to understand culturally relevant outcomes, it is also important to concurrently homogenize the use of validated survey instruments to address common outcomes across studies. In addition, given the variety of interventions currently being implemented in humanitarian settings, it would be beneficial to have guidelines regarding fidelity monitoring, and areas for porosity to ensure contextually relevant adaptations (Torre, 2020).

Implementation science provides useful frameworks for understanding the implementation of MHPSS programming in humanitarian settings. Hybrid designs, especially, can provide information on effectiveness and implementation concurrently, without sacrificing key research goals (Bernet et al., 2013). Frameworks such as RE-AIM, CFIR (Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research), and various others are useful to guide the development and rigorous evaluation of interventions (Powell et al., 2015; Proctor et al., 2011, 2013). Through fidelity to these implementation science frameworks of analysis, intervention implementation can be more systematically researched, scaled, and replicated. For example, if common indicators of success such as assessments of feasibility, barriers and facilitators, context-specific adaptations, and adoption methods are more routinely assessed and addressed, the potential for developing scalable implementation strategies will increase.

While the opinions of lay counselors were solicited during the implementation process, there is little information about the counselor experiences of mental health and well-being. Lay counselors received training and some form of supervision across studies but only one study discussed payment for the community volunteers, and no studies discussed training on vicarious trauma or compassion fatigue, which are documented to be quite common among humanitarian actors and peer providers (Anderson, 2011; Mancini & Lawson, 2009; Shah et al., 2007). This lack of discussion around compensation and mental health support for lay providers echoes findings in global mental health literature regarding the use of task-shifting interventions (Hoeft et al., 2018; Shahmalak et al., 2019; Singla et al., 2017). In fact, supplemental studies show that when international actors merge with local organizations, they often disrupt indigenous mechanisms for mitigating the risk of vicarious trauma (Hassan, 2013; Ismael, 2013; Mirghani, 2013). This issue is further exacerbated by lack of sustainable funding for the implementation of task-shifting interventions, within humanitarian settings and globally (Singla et al., 2017). In addition, previous task-shifting literature states that interventions delivered by lay counselors may be acceptable to community participants, but not as acceptable to community partners who would support referral mechanisms (Barnett, Gonzalez, et al., 2018; Galvin & Byansi, 2020; Padmanathan & De Silva, 2013; Singla et al., 2017). However, there were no findings about intervention acceptability among community partners in the included studies. Altogether, it would be beneficial to bridge implementation science evidence gaps through a careful analysis of contextual factors unique to humanitarian settings and their influence on MHPSS program delivery. RE-AIM provides a useful framework to understand the state of literature regarding task-shifting interventions, but does not provide a full picture of the complexities unique to task-shifting program implementation in humanitarian contexts.

Conclusion

MHPSS interventions delivered by lay counselors in humanitarian settings within LMIC are effective in improving mental health and well-being. However, without a stronger framework for implementation and criteria for supporting staff, they fall short of meeting the need. This study adds to existing literature about the appropriate avenues to scale up interventions and improve capacity of local community members. Ideally, it will inform future development of MHPSS task-shifting intervention implementation for refugees in LMIC.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-irp-10.1177_2633489521998790 for Task-shifting for refugee mental health and psychosocial support: A scoping review of services in humanitarian settings through the lens of RE-AIM by Flora Cohen and Lauren Yaeger in Implementation Research and Practice

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The project described was supported by Grant Number T32MH019960 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iD: Flora Cohen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7879-3958

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7879-3958

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Ahearn F. L. (2000). Psychosocial wellness of refugees: Issues in qualitative and quantitative research. Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson A. (2011). Peer support and consultation project for interpreters: A model for supporting the well-being of interpreters who practice in mental health settings. Journal of Interpretation, 21(1), 2. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1),19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett M. L., Gonzalez A., Miranda J., Chavira D. A., Lau A. S. (2018). Mobilizing community health workers to address mental health disparities for underserved populations: A systematic review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 45(2), 195–211. 10.1007/s10488-017-0815-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett M. L., Lau A. S., Miranda J. (2018). Lay health worker involvement in evidence-based treatment delivery: A conceptual model to address disparities in care. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 14, 185–208. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean T., Eurelings-Bontekoe E., Mooijaart A., Spinhoven P. (2006). Factors associated with mental health service need and utilization among unaccompanied refugee adolescents. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33(3), 342–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernet A. C., Willens D. E., Bauer M. S. (2013). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Implications for quality improvement science. Implementation Science, 8(1), S2. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-S1-S2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton P., Lee C., Haroz E. E., Murray L., Dorsey S., Robinson C., Ugueto A. M., Bass J. (2014). A transdiagnostic community-based mental health treatment for comorbid disorders: Development and outcomes of a randomized controlled trial among Burmese refugees in Thailand. PLOS Medicine, 11(11), Article e1001757. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothby N., Strang A., Wessells M. G. (2006). A world turned upside down: Social ecological approaches to children in war zones. Kumarian Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bramer W., Giustini D., de Jonge G., Holland L., Bekhuis T. (2016). De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. Journal of Medical Library Association, 104(3), 240–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo E. G., Ijadi-Maghsoodi R., Shadravan S., Moore E., Mensah M. O., Docherty M., Aguilera Nunez M. G., Barcelo N., Goodsmith N., Halpin L. E., Morton I., Mango J., Montero A. E., Rahmanian Koushkaki S., Bromley E., Chung B., Jones F., Gabrielian S., Gelberg L., . . .Wells K. B. (2019). Community interventions to promote mental health and social equity. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(5), 35. 10.1007/s11920-019-1017-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çeri V., Özer Ü. (2018). Türkiye’deki bir sığınmacı kampında yaşayan bir grup çocuk ve ergende gözlenen duygusal ve davranışsal sorunlar [Emotional and behavioral problems seen among a group of children and adolescents living in a refugee camp in Turkey]. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi, 19(4), 419–426. 10.5455/apd.285734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cork C., Kaiser B. N., White R. G. (2019). The integration of idioms of distress into mental health assessments and interventions: A systematic review. Global Mental Health, 6, Article E7. 10.1017/gmh.2019.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Crawford N., Cosgrave J., Haysom S., Walicki N. (2015). Protracted displacement: Uncertain paths to self-reliance in exile. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/publications/9906-protracted-displacement-uncertain-paths-self-reliance-exile

- Desai G., Chaturvedi S. K. (2017). Idioms of distress. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 8(Suppl. 1), S94–S97. 10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_235_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dickson K., Bandpan M. (2018). What are the barriers to, and facilitators of, implementing and receiving MHPSS programmes delivered to populations affected by humanitarian emergencies? A qualitative evidence synthesis. Global Mental Health, 5, Article E21. 10.1017/gmh.2018.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Feiring E., Lie A. E. (2018). Factors perceived to influence implementation of task shifting in highly specialised healthcare: A theory-based qualitative approach. BMC Health Services Research, 18, Article 899. 10.1186/s12913-018-3719-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Galvin M., Byansi W. (2020). A systematic review of task shifting for mental health in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Mental Health, 49(4), 336–360. 10.1080/00207411.2020.1798720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R. E., Harden S. M., Gaglio B., Rabin B., Smith M. L., Porter G. C., Ory M. G., Estabrooks P. A. (2019). RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: Adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, Article 64. 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gormez V., Kılıç H. N., Orengul A. C., Demir M. N., Mert E. B., Makhlouta B., Kınık K., Semerci B. (2017). Evaluation of a school-based, teacher-delivered psychological intervention group program for trauma-affected Syrian refugee children in Istanbul, Turkey. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(2), 125–131. 10.1080/24750573.2017.1304748 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harden S. M., Gaglio B., Shoup J. A., Kinney K. A., Johnson S. B., Brito F., Blackman K. C. A., Zoellner J. M., Hill J. L., Almeida F. A., Glasgow R. E., Estabrooks P. A. (2015). Fidelity to and comparative results across behavioral interventions evaluated through the RE-AIM framework: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 155. 10.1186/s13643-015-0141-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M. (2013). Personal reflections on a psychosocial community outreach programme and centre in Damascus, Syria. Intervention, 11(3), 330–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeft T. J., Fortney J. C., Patel V., Unützer J. (2018). Task-sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low-resource settings: A systematic review. The Journal of Rural Health, 34(1), 48–62. 10.1111/jrh.12229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im H., Jettner J. F., Warsame A. H., Isse M. M., Khoury D., Ross A. I. (2018). Trauma-informed psychoeducation for Somali refugee youth in urban Kenya: Effects on PTSD and psychosocial outcomes. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 11(4), 431–441. 10.1007/s40653-017-0200-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee. (2007). IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismael M. (2013). Painting glass as a psychosocial intervention: Reflections of a psychosocial refugee outreach volunteer in Damascus, Syria. Intervention, 11(3), 336–339. 10.1097/WTF.0000000000000007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini M. A., Lawson H. A. (2009). Facilitating positive emotional labor in peer-providers of mental health services. Administration in Social Work, 33(1), 3–22. 10.1080/03643100802508619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S. (2013). UNHCR’S mental health and psychosocial support for persons of concern [Global review]. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. https://www.unhcr.org/51bec3359.pdf

- Mirghani Z. (2013). Healing through sharing: An outreach project with Iraqi refugee volunteers in Syria. Intervention, 11(3), 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151, 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. K., Hall B. J., Dorsey S., Ugueto A. M., Puffer E. S., Sim A., Ismael A., Bass J., Akiba C., Lucid L., Harrison J., Erikson A., Bolton P. A. (2018). An evaluation of a common elements treatment approach for youth in Somali refugee camps. Global Mental Health, 5, Article E16. 10.1017/gmh.2018.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mutamba B. B., van Ginneken N., Smith Paintain L., Wandiembe S., Schellenberg D. (2013). Roles and effectiveness of lay community health workers in the prevention of mental, neurological and substance use disorders in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 13, Article 412. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nakkash R. T., Alaouie H., Haddad P., El Hajj T., Salem H., Mahfoud Z., Afifi R. A. (2012). Process evaluation of a community-based mental health promotion intervention for refugee children. Health Education Research, 27(4), 595–607. 10.1093/her/cyr062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner F., Onyut P. L., Ertl V., Odenwald M., Schauer E., Elbert T. (2008). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder by trained lay counselors in an African refugee settlement: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 686–694. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.4.686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanathan P., De Silva M. J. (2013). The acceptability and feasibility of task-sharing for mental healthcare in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 97, 82–86. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M. D. J., Godfrey C. M., Khalil H., McInerney P., Parker D., Soares C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B. J., Waltz T. J., Chinman M. J., Damschroder L. J., Smith J. L., Matthieu M. M., Proctor E. K., Kirchner J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1), 21. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E. K., Powell B. J., McMillen J. C. (2013). Implementation strategies: Recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Science, 8(1), 139. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E. K., Silmere H., Raghavan R., Hovmand P., Aarons G., Bunger A., Griffey R., Hensley M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. A., Garland E., Katz C. (2007). Secondary traumatic stress: Prevalence in humanitarian aid workers in India. Traumatology, 13(1), 59–70. 10.1177/1534765607299910 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahmalak U., Blakemore A., Waheed M. W., Waheed W. (2019). The experiences of lay health workers trained in task-shifting psychological interventions: A qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13(1), 64. 10.1186/s13033-019-0320-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiras P. (1996). Humanitarian emergencies and the role of NGOs. In Whitman J., Pocock D. (Eds.), After Rwanda: The coordination of United Nations Humanitarian Assistance (pp. 106–117). Palgrave Macmillan. 10.1007/978-1-349-24708-0_8 [DOI]

- Singla D., Kohrt B., Murray L., Anand A., Chorpita B., Patel V. (2017). Psychological treatments for the world: Lessons from low- and middle-income countries. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 149–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siriwardhana C., Stewart R. (2013). Forced migration and mental health: Prolonged internal displacement, return migration and resilience. International Health, 5(1), 19–23. 10.1093/inthealth/ihs014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan A., Simonson G. (2016). A systematic review of school-based social-emotional interventions for refugee and war-traumatized youth. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 503–530. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan J. E., Thorn N., Amin M., Mason K., Lue N., Nawzir M. (2019). Using simple acupressure and breathing techniques to improve mood, sleep and pain management in refugees: A peer-to-peer approach in a Rohingya refugee camp. 10.4103/INTV.INTV_13_19 [DOI]

- Tarannum S., Elshazly M., Harlass S., Ventevogel P. (2019). Integrating mental health into primary health care in Rohingya refugee settings in Bangladesh: Experiences of UNHCR. Intervention, 17(2), 130–139. 10.4103/INTV.INTV_34_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tay A., Awal Miah M. A., Khan S., Badrudduza M., Alam R., Balasundaram S., Rees S., Morgan K., Silove D. (2019). Implementing integrative adapt therapy with Rohingya refugees in Malaysia: A training-implementation model involving lay counsellors. Intervention, 17(2), 267–277. 10.4103/INTV.INTV_45_19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tol W. A., Augustinavicius J., Carswell K., Leku M. R., Adaku A., Brown F. L., García-Moreno C., Ventevogel P., White R. G., Kogan C. S., Bryant R., van Ommeren M. (2018). Feasibility of a guided self-help intervention to reduce psychological distress in South Sudanese refugee women in Uganda. World Psychiatry, 17(2), 234–235. 10.1002/wps.20537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre C. (2020). Self-help or silenced voices? An ethnographically informed warning. The Lancet Global Health, 8(5), Article e646. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30106-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A. C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K. K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Moher D., Peters M. D. J., Horsley T., Weeks L., Hempel S., Akl E. A., Chang C., McGowan J., Stewart L., Hartling L., Aldcroft A., Wilson M. G., Garritty C., . . .Straus S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (1994). Refugees Magazine Issue 97 (NGOs and UNHCR)—NGOs: Our right arm. https://www.unhcr.org/publications/refugeemag/3b53fd8b4/refugees-magazine-issue-97-ngos-unhcr-ngos-right-arm.html

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2020). Figures at a glance. https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

- Vijayakumar L., Mohanraj R., Kumar S., Jeyaseelan V., Sriram S., Shanmugam M. (2017). CASP—An intervention by community volunteers to reduce suicidal behaviour among refugees. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 63(7), 589–597. 10.1177/0020764017723940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2018). Fair progress? Economic mobility across generations around the world. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/publication/fair-progress-economic-mobility-across-generations-around-the-world

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-irp-10.1177_2633489521998790 for Task-shifting for refugee mental health and psychosocial support: A scoping review of services in humanitarian settings through the lens of RE-AIM by Flora Cohen and Lauren Yaeger in Implementation Research and Practice