Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted existing crises and introduced new stressors for various populations. We suggest that a multilevel ecological perspective, one that researchers and practitioners have used to address some of public health’s most intransigent challenges, will be necessary to address emotional distress and mental health problems resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple levels of influence (individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy) each contribute (individually and in combination) to population health and individual well-being. We use the convergence strategy to illustrate how multilevel communication strategies designed to raise awareness, educate, or motivate informed decision-making or behavior change can address various sources of information surrounding a person to synergistically affect mental health outcomes. Looking ahead, dissemination and implementation researchers and practitioners will likely need to coordinate organizations and networks to speak in complementary and resonant ways to enhance understanding of complex information related to the pandemic, mitigate unnecessary anxiety, and motivate healthy behavior to support population mental health.

Plain language abstract:

The current COVID-19 pandemic has threatened the mental health and well-being of various populations. The pandemic also has compounded health disparities experienced by communities of color and magnified the vast treatment gaps they experience related to behavioral health and substance use treatment access. A multilevel approach to future communication interventions focused on mental health likely will be useful, as we need to know about and address interactions with health care professionals, mass media information sources, social networks, and community influences rather than solely trying to reach people with carefully crafted videos or advertisements. Implementation researchers and practitioners likely will need to coordinate organizations and networks to speak in complementary and resonant ways to support population mental health.

Keywords: COVID-19, pandemic, mental health, multilevel communication

To address some of public health’s most intransigent challenges—such as changing unhealthy behaviors or addressing health disparities that are driven by social determinants of health—researchers and practitioners have begun to use a multilevel ecological perspective that accounts for context in considering interventions. This same multilevel ecological perspective will be necessary to optimally communicate about factors that may moderate the emotional distress and mental health problems resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Here we focus specifically on the dissemination and implementation of communication interventions, which are defined broadly as interven-tions involving informational exchanges that seek to raise awareness, educate, or motivate informed decision-making or behavior change. These informational exchanges can be one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many. They also may involve one or more communication channels, such as print, digital, interpersonal, or mass communication.

Communication is a multilevel phenomenon

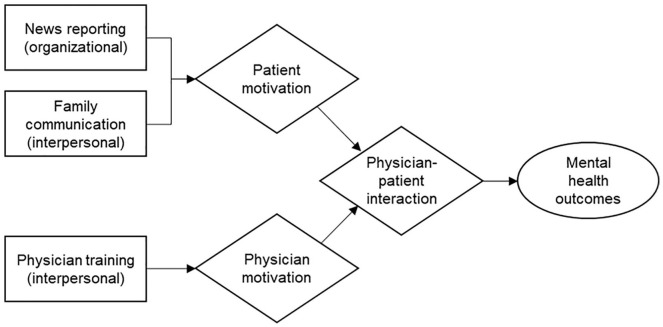

It is not difficult to argue that multiple levels of influence—such as individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy—each contribute to population health and individual well-being. Importantly, though, we also need to consider interactions between levels. For example, by considering how the different levels interact, we can optimize communication interventions by designing them to work synergistically at multiple levels to influence mental health outcomes. We use the convergence strategy proposed by Weiner and colleagues (2012) to illustrate potential multilevel synergy. For example, communication among informal interpersonal sources (family, friends, coworkers) and formal sources (physicians, therapists) separately or in conjunction can affect an individual’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. We also know that organizations (workplaces, news organizations, or health systems) are important sources of information (or misinformation) influencing individual behavior and well-being (Southwell et al., 2019). Additionally, communities, whether they be online or defined by geography, can shape experience. As such, multilevel communication interventions may increase the chances of effectively influencing mental health outcomes by addressing various sources of information surrounding a person.

In the context of COVID-19, what might we do to optimize public understanding of complex science related to the pandemic, mitigate unnecessary anxiety, and motivate healthy behavior? We could consider a single focused educational campaign through mass media channels that focuses on reaching individuals directly with self-help information. At the same time, we know that efforts to reach individuals directly with messages in this way will exist alongside myriad other public information dynamics, social network activity, and historical differences in access to information, such as formal education or health literacy. Focusing only on reaching individuals with an isolated educational campaign will not provide the multilevel support we could be offering. We also need to acknowledge (and attempt to shape when possible) various streams of information reaching a person. We illustrate this point using the convergence strategy.

The convergence strategy

The convergence strategy (Figure 1) illustrates how interventions at the organizational and interpersonal levels can be mutually reinforcing by changing patterns of interaction between two or more audiences, in this case patients and health care providers. These multilevel interventions are synergistic because they exhibit what is termed reciprocal interdependence (Thompson, 1967). For example, as shown in Figure 1, if we consider the sources of information that surround a patient, we can begin to see opportunities for potential interactions that promote or undermine positive mental health outcomes. Although health care providers strive to offer timely and accessible information to their patients, many health care providers lack training in mental health care (Pfefferbaum & North, 2020) or in patient education or counseling techniques, especially with regard to historical and structural forces that can shape a person’s engagement with health information (e.g., Ammentorp et al., 2007). What is immediately salient for patients, in turn, is often a function of what recent news headlines or social media posts have highlighted (Southwell et al., 2016). Unfortunately, patients can find substantial amounts of medical misinformation during a quick session on social media or with any online search engine (Southwell et al., 2019). We also cannot assume that journalistic institutions will provide optimally focused information without assistance. As we have noted elsewhere (Uhrig et al., 2020), budget cuts have decimated U.S. newsrooms for years. Many news outlets have merged health journalism beats that once exclusively focused on medical and public health stories with more general reporting. Consequently, a gap has emerged in the translation of medical and scientific evidence into plain English for lay audiences. Patient understanding and motivation also can be influenced (positively or negatively) by exposure to organizational-level communication that is consistent or conflicting with interpersonal exchanges with family members and with exchanges during clinical encounters to produce either positive or negative mental health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Convergence strategy.

Boxes show intervention and level (in parentheses). Diamonds indicate mediators. The oval indicates the outcome. A single mediating pathway is presented for simplicity, and other potential effects are not depicted.

Communication is a convergent, multilevel phenomenon in which people and their environments interact (Manojlovich et al., 2015; Southwell, 2005). Not only can we explain variance in health outcomes at these different levels, but, as we have illustrated with the convergence strategy, we need to plan for cross-level interactions in which forces at one level either constrain or enhance the effects of factors at another level.

Multilevel communication and implementation strategies

Through the convergence strategy, we have suggested how multilevel communication strategies—efforts to ensure we are supporting people directly and indirectly through the coordination of various sources of influence—can synergistically affect mental health outcomes. Lewis and colleagues (2017) found that engagement, coordination, and alignment between patients, health care providers, and health systems were related to better communication, information sharing, support, and health care access in an evaluation of a cross-site national initiative aimed at reducing health disparities in diabetes among underserved communities using the convergence strategy approach. Similarly, we might expect that these same implementation strategies may improve mental health outcomes by optimizing interactions between patients, health care providers, and health systems better than single-level intervention alone. Other implementation strategies might be better reflected in other examples developed by Weiner and colleagues (2012), including the accumulation, amplification, facilitation, or cascade models. As this research area is in its infancy, future studies should explore the intersection of multilevel communication interventions and implementation strategies focused on improving mental health outcomes.

A multilevel approach to dissemination through translation and connection

We can find a multilevel perspective reflected already in some translational work that actively connects various levels of consideration to improve patient health. Work funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is relevant, such as the development and dissemination of lay version abstracts of scientific studies to make evidence more accessible to the public (Broitman et al., 2019). We also can see a multilevel perspective in research on direct-to-consumer advertising for prescription drugs, such as the work of the Food and Drug Administration (Sullivan et al., 2019). Furthermore, tools like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Clear Communication Index (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020) provide evidenced-based recommendations on developing communication to enhance public understanding of complex health information. What is common to many of these efforts is the realization that many of the most urgent communication challenges we face lie not just in patient information deficits per se, but rather in problems at the intersection between individual patients and the systems in which they seek care, a point echoed previously by scholars who argued for the importance of communication as a key process in knowledge translation (Manojlovich et al., 2015).

Conclusion

We need more recognition that people live in systems that operate in the present and that also have been operating in the past. We come to this conclusion as communication researchers. From our perspective, implementation researchers and practitioners are well positioned both to identify the various sources and systems that surround patients and to build translational efforts that ensure communication between patients and those sources. We have engines for medical science research, we have platforms for reaching large audiences with information, and we have health care systems that enroll patients and offer care. These various components, however, often operate independently in terms of funding and formal scope. As we cope with the COVID-19 pandemic and plan for future public health emergencies, what we need to build now are more ties between the components of a patient’s world so that we can better understand the information flooding (or absent from) patient perspectives, identify patient needs for mass media outlets and health care providers, and ensure accurate understanding of rapidly generated peer-reviewed science among patients trying to make decisions that will affect their health and well-being.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Ammentorp J., Sabroe S., Kofoed P.-E., Mainz J. (2007). The effect of training in communication skills on medical doctors’ and nurses’ self-efficacy: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 66(3), 270–277. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broitman M., Sox H. C., Slutsky J. (2019). A model for public access to trustworthy and comprehensive reporting of research. Journal of the American Medical Association, 321(15), 1453–1454. 10.1001/jama.2019.2807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). The CDC Clear Communication Index. https://www.cdc.gov/ccindex/index.html

- Lewis M. A., Fitzgerald T. M., Zulkiewicz B., Peinado S., Williams P. A. (2017). Identifying synergies in multilevel interventions: The convergence strategy. Health Education and Behavior, 44(2), 236–244. 10.1177/1090198116673994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manojlovich M., Squires J. E., Davies B., Graham I. D. (2015). Hiding in plain sight: Communication theory in implementation science. Implementation Science, 10, Article 58. 10.1186/s13012-015-0244-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B., North C. S. (2020). Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. The New England Journal of Medicine. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Southwell B. G. (2005). Between messages and people: A multilevel model of memory for television content. Communication Research, 32(1), 112–140. 10.1177/0093650204271401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Southwell B. G., Dolina S., Jimenez-Magdaleno K., Squiers L. B., Kelly B. J. (2016). Zika virus-related news coverage and online behavior, United States, Guatemala, and Brazil. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 22(7), 1320–1321. 10.3201/eid2207.160415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwell B. G., Niederdeppe J., Cappella J. N., Gaysynsky A., Kelley D. E., Oh A., Peterson E. B., Chou W. S. (2019). Misinformation as a misunderstood challenge to public health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57(2), 282–285. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan H. W., Aikin K. J., Poehlman J. (2019). Communi-cating risk information in direct-to-consumer prescription drug television ads: A content analysis. Health Commu-nication, 34(2), 212–219. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1399509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D. (1967). Organizations in action; Social science bases of administrative theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Uhrig J. D., Lewis M. A., Poehlman J. A., Southwell B. G. (2020). Beyond evidence reporting: Evidence translation in an era of uncertainty [online publication of Medical Care]. Medical Care Blog. https://www.themedicalcareblog.com/evidence-translation/ [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. J., Lewis M. A., Clauser S. B., Stitzenberg K. B. (2012). In search of synergy: Strategies for combining interventions at multiple levels. Journal of the National Cancer Institute: Monographs, 2012(44), 34–41. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]