Abstract

Background

Despite the promise of implementation science (IS) to reduce health inequities, critical gaps and opportunities remain in the field to promote health equity. Prioritizing racial equity and antiracism approaches is critical in these efforts, so that IS does not inadvertently exacerbate disparities based on the selection of frameworks, methods, interventions, and strategies that do not reflect consideration of structural racism and its impacts.

Methods

Grounded in extant research on structural racism and antiracism, we discuss the importance of advancing understanding of how structural racism as a system shapes racial health inequities and inequitable implementation of evidence-based interventions among racially and ethnically diverse communities. We outline recommendations for explicitly applying an antiracism lens to address structural racism and its manifests through IS. An anti-racism lens provides a framework to guide efforts to confront, address, and eradicate racism and racial privilege by helping people identify racism as a root cause of health inequities and critically examine how it is embedded in policies, structures, and systems that differentially affect racially and ethnically diverse populations.

Results

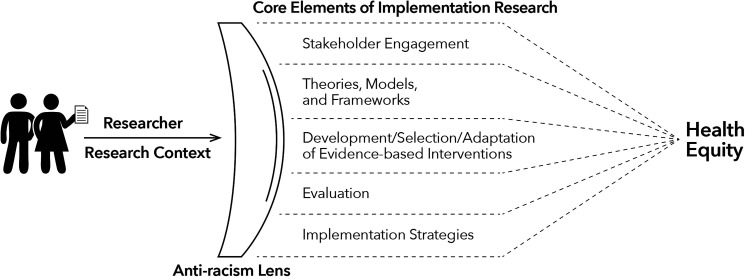

We provide guidance for the application of an antiracism lens in the field of IS, focusing on select core elements in implementation research, including: (1) stakeholder engagement; (2) conceptual frameworks and models; (3) development, selection, adaptation of EBIs; (4) evaluation approaches; and (5) implementation strategies. We highlight the need for foundational grounding in antiracism frameworks among implementation scientists to facilitate ongoing self-reflection, accountability, and attention to racial equity, and provide questions to guide such reflection and consideration.

Conclusion

We conclude with a reflection on how this is a critical time for IS to prioritize focus on justice, racial equity, and real-world equitable impact. Moving IS towards making consideration of health equity and an antiracism lens foundational is central to strengthening the field and enhancing its impact.

Plain language abstract

There are important gaps and opportunities that exist in promoting health equity through implementation science. Historically, the commonly used frameworks, measures, interventions, strategies, and approaches in the field have not been explicitly focused on equity, nor do they consider the role of structural racism in shaping health and inequitable delivery of evidence-based practices/programs. This work seeks to build off of the long history of research on structural racism and health, and seeks to provide guidance on how to apply an antiracism lens to select core elements of implementation research. We highlight important opportunities for the field to reflect and consider applying an antiracism approach in: 1) stakeholder/community engagement; 2) use of conceptual frameworks; 3) development, selection and adaptation of evidence-based interventions; 4) evaluation approaches; 5) implementation strategies (e.g., how to deliver evidence-based practices, programs, policies); and 6) how researchers conduct their research, with a focus on racial equity. This is an important time for the field of implementation science to prioritize a foundational focus on justice, equity, and real-world impact through the application of an anti-racism lens in their work.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, health equity, racism, antiracism, evaluation, implementation strategy, implementation, conceptual framework

The COVID-19 pandemic and recent racial injustices have brought greater global recognition to the relationship between racial health inequities and racism as a determinant of health (Chowkwanyun & Reed, 2020; Gross et al., 2020; Williams & Cooper, 2020; Williams et al., 2019a). For Implementation Science (IS), a field established to improve the translation of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) into routine practice across diverse settings and populations (Brownson et al., 2018), it is imperative for researchers to reflect on and enhance their ability to consider and address racism in implementation research and practice (Shelton et al., 2021a).

Racism as a Fundamental Driver of Racial Health Inequities: Racism is a hierarchical structure of oppression that operates at multiple levels and across systems (e.g., housing, education, employment, credit, healthcare, criminal justice) to create, reinforce, and maintain social and health inequities (Bailey et al., 2017; Reskin, 2012). Structural racism has been defined as the totality of societal structures and policies that create and maintain inequities by unequally distributing access to opportunities and societal resources by race and ethnicity (Bailey et al., 2017; LeBrón & Viruell-Fuentes, 2019; Williams et al., 2019b). Research has elucidated the health impacts of structural racism (e.g., residential segregation, incarceration, immigration policy) across the lifecourse (Bailey et al., 2017; Gee & Ford, 2011; Williams et al., 2019a). For example, a widely used algorithm for determining which patients with complex health needs would benefit from extra medical care favored white patients and underestimated the health needs of Black patients, because it was informed by data (i.e., costs) shaped by embedded societal and institutional biases (Obermeyer et al., 2019). This highlights how racism operates at interconnected levels within and across institutions and policies that are entrenched and adaptive in maintaining racial health inequities (Bailey et al., 2017, 2020; Hardeman et al., 2016; Reskin, 2012).

Gaps and Opportunities for Addressing Racism through Implementation Science: There is growing interest in health equity within IS (Annie E. Casey Foundation, Summer 2021; Brownson et al., 2021; Cooper et al., 2021; Eslava-Schmalbach et al., 2019; Galaviz et al., 2020). This interest includes modifications of frameworks to address equity (Baumann & Cabassa, 2020; Woodward et al., 2019, 2021), and promising approaches for incorporating social determinants of health (SDOH) (e.g., focus on context, adaptation of EBIs; Aschbrenner et al., 2021). Despite this interest, the core methods and frameworks commonly applied in IS have not emphasized equity or racism. Racism and resulting power dynamics are contextual implementation factors that shape the experiences, cultures, and history of the organizations and communities in which researchers work. Omitting structural racism as a key contextual factor in IS affects the effectiveness, feasibility, acceptability, adoption, implementation, and sustainability of EBIs in racially/ethnically diverse communities. Lack of consideration of racism can lead to inaccurate or incomplete explanations as to why racial inequities exist (Krieger et al., 2019), and suboptimal selection of EBIs and strategies (e.g., “solutions”) for addressing inequities. Making meaningful, sustained shifts in addressing and eradicating unjust and avoidable health inequities require identifying racism and other root causes of the disease, and incorporating social justice principles when addressing them (Braveman et al., 2011). Thus, explicitly applying an antiracism lens is essential to advancing the pursuit of racial health equity and justice through IS.

Application of an Antiracism Lens in Implementation Research: Antiracism is a framework that can be applied in public health/healthcare to confront, address, and eradicate racism, unearned racial privilege, and their adverse effects on health by helping people to: (1) identify racism as a root cause of health inequities; and (2) critically examine how racism is embedded in policies, structures, and systems in ways that differentially affect racially and ethnically diverse populations (Bonnett, 2000; Came & Griffith, 2018; LeBrón & Viruell-Fuentes, 2019). As a racially and ethnically diverse transdisciplinary team that includes implementation and health equity researchers, we build on the long history of scholarship on health equity and antiracism led by racially/ethnically diverse scholars. We provide recommendations for applying an antiracism lens in implementation research (Table 1, Figure 1) and actionable guidance on addressing structural racism. We discuss the application of an antiracism lens to select core elements of implementation research as examples of key areas for researchers to leverage to advance health equity (Koh et al., 2020; Shelton et al., 2020b). These core elements include: (1) stakeholder engagement; (2) conceptual frameworks and models; (3) development, selection, and/or adaptation of EBIs; (4) evaluation approaches; and (5) implementation strategies. We also describe the grounding and self-reflection needed for implementation scientists to bring an antiracism lens to their work.

Table 1.

Recommendations, considerations, and key questions for reflection in bringing an antiracism lens to implementation research and researchers.

| Core elements and recommendations for implementation research | Current/historical approach commonly applied in implementation research | Contributions of and recommendations for applying an antiracism lens to implementation research | Key questions for reflection and consideration in applying an antiracism lens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder engagement (research) Applying an antiracism lens in IS necessitates early and ongoing inclusion and engagement of all communities and stakeholders affected by research outcomes as foundational. |

|

|

|

| Conceptual frameworks and models (research) An antiracism lens will consider racism as a determinant and key aspect of context in IS conceptual frameworks, theories, and models. |

|

|

|

| Development, selection, and/or adaptation of evidence-based

interventions (EBI) (research) Applying an antiracism lens in IS includes consideration of the development, selection and/or testing of multilevel and structural interventions that include a focus on promoting health equity and addressing racism, as well as the de-implementation and dismantling of harmful or inequitable policies, practices, programs. |

|

|

|

| Evaluation approaches (measures & methods)

(research) An antiracism lens will explicitly include measures and evaluation approaches to assess racism and health equity. |

|

|

|

| Implementation strategies (research) Applying an antiracism lens in IS will require application and testing of implementation strategies to advance the spread and scale of antiracist, equity-focused solutions. |

|

|

|

| Individual researcher and research context To conduct IS research on health equity, self-reflection and attention to racial equity, justice, and race and racism consciousness should be foundational and ongoing grounding for implementation scientists. |

|

|

|

Figure 1.

Application of an antiracism lens in implementation science.

Stakeholder Engagement: Applying an Antiracism Lens in Implementation Research Necessitates Early and Ongoing Inclusion and Engagement of Communities

Community engagement in research provides a critical foundation for creating and sustaining structural change, promoting health equity, and avoiding the exacerbation of health disparities (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). Community engagement involves approaches to developing relationships and working with stakeholders in the research process that exist along a continuum (Key et al., 2019), and includes community-based participatory research (CBPR). CBPR is an approach to research that: (1) is action-oriented and social justice focused; (2) builds on community assets; (3) meaningfully engages the community in decision-making and prioritization; (4) encourages bi-directional learning and capacity-building; (5) facilitates mutual benefit and trust; and (6) necessitates transparent, equitable distribution of power and resources (Israel et al., 2003; Michener et al., 2020; Minkler et al., 2012; Wallerstein & Duran, 2003, 2010, 2017). Aligned with this approach, Wolff et al. (2017) propose equity and justice-oriented principles for collaborating with historically marginalized, racially/ethnically diverse communities that prioritize: addressing social/economic injustice and structural racism; community development and organizing to facilitate equitable community ownership, power, and resources; and systems, structural, and policy changes (Kegler et al., 2019).

While stakeholder engagement (e.g., with patients, community members, providers, organizational leaders, policymakers) is a common approach for enhancing adoption and implementation (Pinto et al., 2021; Ramanadhan et al., 2018), how, when, and how long communities are involved in the research process varies, as does the racial/ethnic diversity of groups represented (Wells & Jones, 2009). While not sufficient to eliminate structural racism, we see community engagement and co-creation as central to implementation research efforts using an antiracism approach to pursue health equity, by creating structures and processes for incorporating community perspectives and priorities. Meaningful community engagement can increase the likelihood EBIs and strategies are relevant, acceptable, appropriate, sustainable, and trusted without reinforcing racism or exacerbating racial inequities (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). Bringing an antiracism lens to stakeholder engagement in implementation research involves transparency, consideration of power dynamics, equitable sharing of resources, respect of community values, and inclusion of racially/ethnically diverse partners as equitable decision-makers early and often.

Given asymmetrical power relationships and resource allocation that can exist between researchers and communities, it is important to ground implementation research in community engagement. Incorporating community engagement can refine who defines the “problems” and “solutions”, who is at the table to decide (and who is excluded), metrics for what counts as “evidence-based”, and what settings/populations are represented in research (Freudenberg & Tsui, 2014). Community engagement approaches are not inherently antiracist, but can be applied as an antiracism approach if they include reflection on racism and power, confronting hard truths, and openness to shifting how we conduct research (Came & Griffith, 2018; Glasgow, 2020). For example, academic language that privileges researchers over the community can operate as a form of oppressive power (Wallerstein et al., 2019), and the ever-expanding lexicon in IS may operate similarly in an exclusionary way. Implementation researchers may benefit from applying user-centered design approaches to communicate research (Dopp et al., 2020), similar to approaches from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s Dissemination and Implementation Toolkit (Mathematica Policy Research, 2015). Researchers using antiracism approaches recognize the folly that can exist if communities are not involved with evidence generation, and the potential for disempowering communities if the evidence does not reflect their lived experiences and reinforces concerns about the trustworthiness of medical, public health, and research institutions (Griffith et al., 2020a, 2020b). Tools from the NIH-funded Engage for Equity (E2) study can facilitate reflection and action towards strengthening community/academic partnerships and operationalizing social justice goals (http://engageforequity.org/; Parker et al., 2020; Wallerstein, 2020).

It may not be possible to achieve the benefits of community engagement in implementation research seeking to promote antiracism if there is not adequate compensation or direct benefit to partners. Antiracism-informed implementation research must be coupled with funding and/or infrastructure changes that require research budgets to pay community-based organizations indirect costs, compensate partners for their time and expertise, and engage them in determining fair and appropriate compensation. Researchers may consider developing a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with community stakeholders to facilitate explicit discussion and expectations regarding the distribution of resources, costs, and data ownership. Additionally, implementation researchers must be attuned to how power, racism, and privilege are affecting the collaborative partnerships in their own community-engaged research (Ortiz et al., 2020; Yonas et al., 2006).

Conceptual Frameworks and Models: An Antiracism Lens Considers Racism as a Determinant and Key Aspect of Context in Implementation Frameworks, Theories, Models

Many IS determinant frameworks (e.g., Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, CFIR; Damschroder et al., 2009) emphasize multilevel context (Nilsen & Bernhardsson, 2019), yet implementation researchers often focus on organizational or “inner” context (e.g., implementation climate) without attention to how racism and power are operating. There has been insufficient focus on aspects of extra-organizational or social context that shape communities, institutions, and provision of care (e.g., racism, regulations, healthcare system norms, bias, stigma, medical mistrust; Griffith et al., 2007; Stangl et al., 2019). These aspects of racism operate within institutional norms, organizational/funding structures and policies, and healthcare systems (e.g., lack of racial/ethnic diversity of healthcare workforce) to influence implementation and outcomes (Griffith et al., 2007). The role of historical and ongoing racism in shaping SDOH is critical to address the given implications it has for differential resource allocation, healthcare utilization, and structural barriers to health (Krist et al., 2019).

Racism affects everyone in society (Gee & Ford, 2011); as such, implementation researchers should consider and examine structural racism as a contextual factor influencing implementation. Specifically, they should consider how structural racism shapes equitable or inequitable adoption, implementation, and sustainability of EBIs at the policy, system, organizational, community, provider, and individual levels (Alcaraz et al., 2020). Structural racism should be assessed as part of a contextual inquiry or formative work in understanding current and historical factors that may influence implementation (e.g., historical relationships between researchers/community; social conditions in the geographic context), or in assessing barriers/facilitators to equitable implementation (e.g., structural racism as a driver of disparate mental health outcomes and suboptimal access to and adoption of evidence-based mental health treatments in settings that serve diverse communities; Blas & Kurup, 2010; Cross et al., 2019; Harnett & Ressler, 2021; Moise & Hankerson, 2021). Even if a study’s research question does not directly focus on societal context, an antiracist approach would acknowledge, assess, or address how structural racism may shape implementation and modify downstream determinants of EBIs. IS may benefit from CBPR approaches that include assets-based contextual assessments, such as an Action-Oriented Community Diagnosis (AOCD), to inform efforts to leverage existing community strengths and mitigate root causes of racial health inequities (Eng & Blanchard, 2006; Eng et al., 2012).

Equity-focused determinant frameworks (e.g., The Health Equity Implementation Framework; Woodward et al., 2019) and adaptations to existing IS theories, frameworks, and models may elucidate how racism affects implementation and health outcomes (e.g., see Allen et al., 2021 for racism-conscious adaptation of CFIR). For example, Bendall et al. (2016) used CFIR and community engagement to tailor the implementation of a community chronic disease program to reflect the worldview of a historically marginalized Indigenous Aboriginal population in British Columbia. Etherington et al. (2020) developed a tool to use alongside the Theoretical Domains Framework to bring an intersectionality lens to understanding how social identities (race, gender) and power structures (racism, sexism) influence barriers/facilitators to implementation. Further, Stanton and Ali (2020) explicated how forms of formal and informal power operate across implementation phases using the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) framework. Adapting IS frameworks or integrating existing frameworks and theories from outside of IS to include consideration of structural racism provides opportunities to advance this study (Alcaraz et al., 2020; Bowleg, 2017a; Ford et al., 2019; Griffith et al., 2021; Snell-Rood et al., 2021). Prioritizing the inclusion of structural racism in contextual inquiries and research, particularly for communities experiencing inequities, allows IS to build an evidence base around how racism influences implementation outcomes (e.g., adoption, implementation, sustainability) and health equity.

Implementation of Evidence-based Interventions: Applying an Antiracism Lens in Implementation Research Requires the Development, Selection, and/or Adaptation of Multilevel & Structural Interventions that Include a Focus on Health Equity and Addressing Racism

An antiracism lens requires reflection on how we select and prioritize EBIs. Many EBIs have not been developed with explicit consideration of how structural racism shapes differential opportunities for people to be healthy, experience stress, or engage in health-promoting behaviors. Even research conducted with diverse racial/ethnic groups often lacks attention to racial/ethnic heterogeneity of the sample and there is a tendency to prioritize randomized designs to establish efficacy (with strict protocols, narrow eligibility). Important questions about EBIs must be answered in partnership with communities, which include: What “counts” as an EBI?; For whom is an intervention “evidence-based”?; Who was involved in evidence generation?; Does the EBI reduce inequities and/or target SDOHs or racism?; and How can EBIs be developed and adapted to promote equity? (Alvidrez et al., 2019).

Interventions are needed to address structural racism directly or explicitly mitigate its health effects, and evidence in this area is growing. If the goal is to use IS and EBIs to promote health equity, it is critical to prioritize disseminating and implementing EBIs that target the root causes of racial/ethnic health inequities or to target interventions further upstream towards structural racism and other root causes. Because there are few existing EBIs with demonstrated efficacy in achieving these goals, it will be necessary to develop and test new interventions explicitly focused on dismantling racism and mitigating its health effects (e.g., applying frameworks like Transcreation Framework for Community-Engaged Behavioral Interventions to Reduce Health Disparities; Napoles & Stewart, 2018). Even when unable to address structural racism directly, implementation researchers should consider how interventions may differentially affect populations and health outcomes because of structural racism.

Given that knowledge production has valued certain types of evidence in determining what is included in EBI repositories, implementation researchers may consider partnering with stakeholders to identify existing “community-defined evidence” or “practice-based evidence” when examining promising practices and interventions for addressing or attenuating the health effects of structural racism (Green, 2008; Martinez et al., 2010). There is also an opportunity to test adaptations to EBIs and policies that seek to address racism and SDOH, and elucidate whether such adaptations to existing EBIs are sufficient to address structural racism and other root causes.

Bringing an antiracism lens to IS also requires trans-disciplinary and multilevel approaches that prioritize interventions and policies extending beyond healthcare settings. A growing evidence base for programs and policies to address racism can provide examples of EBIs to consider prioritizing for dissemination, implementation, and scale-up. Reviews of antiracism interventions and policies show promise to address and mitigate the effects of structural racism and promote more equitable health outcomes (Bailey et al., 2017; Williams & Cooper, 2019; Williams et al., 2019a). Examples include implementation of early childhood development initiatives and policies with demonstrated positive lifelong health and social consequences around reducing childhood poverty (e.g., transfers to enhance family income; Zimmerman et al., 2021), and place-based solutions for improving neighborhood/housing conditions, including affordable housing vouchers (Bailey et al., 2017; Williams & Cooper, 2019). There are also opportunities within the healthcare system to reduce inequities and address the effects of racism through the implementation of programs to address patients’ social needs (e.g., Bailey et al., 2017; Medical-Legal Partnership, Nurse-Family Partnership; Williams & Cooper, 2019). To address structural racism and its effects, IS researchers may consider prioritizing the implementation of policies that reduce health inequities and actively address SDOH and racism, including those related to criminal justice reform (Hardeman et al., 2021).

From a systems perspective, because of the insidious, interconnected, dynamic, multilevel nature of structural racism (Bailey et al., 2017; Reskin, 2012), IS researchers should stretch beyond the traditional boundaries of healthcare sectors and work across other systems (e.g., schooling, employment, housing, justice). For example, Corburn et al. (2015) used a co-production health equity planning process and integrated strategy to promote equity by addressing structural racism and place-based “toxic stressors” through neighborhood-based interventions, violence reduction programs, and drafting a “Health in All Policies” (Association of State & Territorial Health Officials, 2018) equity-focused strategy and city ordinance. Critical to this process were workshops and discussions analyzing how structural racism operated through policies and practices across multisectors to disempower communities, and the generation of practical strategies to dismantle racism and mitigate its impact, including through interinstitutional dynamics and daily governmental and system decisions.

Now is the time to address structural racism in public health and healthcare through an enhanced focus in IS. Health inequities and collective racial trauma have been amplified by COVID-19 and the mental health effects of police killings and their media coverage (Bor et al., 2018). As such, IS researchers should prioritize the implementation of mental health-focused EBIs that reduce inequities and meet the needs of racially diverse communities (e.g., culturally tailored trauma-informed therapies; collaborative care; Cenat, 2020; Comas-Díaz, 2016; Fullilove et al., 2004; Lee-Tauler et al., 2018; Wells et al., 2008).

Implementation researchers can also identify policies and practices that have differential harmful effects on specific racial/ethnic groups and further develop and apply de-implementation science to remove such programs/policies (Agénor et al., 2021; Helfrich et al., 2019). Researchers may benefit from the application of Health Impact Assessment tools which have been used to assess the impact of policy and investment decisions, including whether health impacts of such decisions are equitably distributed (Povall et al., 2014; Prasad et al., 2015; Welch et al., 2017). Ultimately, to change deeply entrenched patterns and address root causes like structural racism, researchers have highlighted that maximally “disruptive” interventions may be necessary (e.g., Browne et al., 2018; Hawe, 2015; Hawe et al., 2009), including new organizational structures, practices, policies, and processes within and across systems to shift power dynamics that structure routine patterns in organizations and societies to reinforce racism.

Evaluation Approaches: An Antiracism Lens Explicitly Includes Measures and Study Designs to Assess Racism and Health Equity

To date, measuring or operationalizing racial equity or racism in IS is not routine. While there is debate on how to appropriately measure racism (Came & Griffith, 2018), and recognition that measuring racism depends on scale, domain, and/or historical context (Bailey et al., 2017; Cross et al., 2019; Groos et al., 2018; Krieger, 2014), it is critical that implementation frameworks and studies include metrics and measures aligned with the inclusion of racism as a contextual determinant of health inequities and inequitable implementation. Beginning to conceptualize and measure racism within implementation research with specificity will inform where and how to intervene; identify potential mechanisms through which racism shapes inequities; and help to determine whether the implementation of EBIs or strategies could reduce racism and its impacts. There are validated measures to capture individual discrimination, including the everyday discrimination measure (Williams, 2016) and experiences of discrimination measure (Krieger et al., 2005), and measures operationalizing structural racism or its effects on SDOH and health outcomes, such as administrative data (e.g., indices of segregation, data on redlining/housing discrimination), and self-report measures (e.g., the Perceived Racial Composition Scale, the Perceived Structural Racism Scale) (Adkins-Jackson et al., 2021, in press; Alson et al., 2021; Ford et al., 2019; Groos et al., 2018; Krieger, 2020).

An antiracism lens requires evaluation metrics to track improvements in health equity outcomes by race/ethnicity, informed by antiracism principles. It requires IS researchers to clarify and operationalize the ways that racism is shaping their study components and outcomes. An antiracism lens would extend the engagement of community stakeholders in determining which measures should be prioritized and ensure that data is disseminated to communities to promote transparency. Transparency and accountability in measuring the impacts of racism on racial inequities are essential for dismantling racism and promoting equity.

To this end, evaluation helps to enhance the assessments of equitable reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and sustainability of EBIs in addressing racism or modifying its effects on health. This has been highlighted in frameworks like RE-AIM, which has been extended to track health and implementation outcomes with an explicit focus on equity and sustainability (Shelton et al., 2020a). Other efforts include reframing Proctor’s IS framework to apply an equity lens to implement indicators like feasibility, costs, fidelity, adoption (Baumann & Cabassa, 2020). Further study is needed to advance the operationalization and validation of these measures in implementation research.

The evidence base for interventions and policies to reduce health inequities and dismantle racism are growing, but further development and testing are needed. This presents a unique opportunity for IS researchers to partner with intervention/policy developers seeking to address racism earlier in the process to design antiracist interventions with implementation in mind. Depending on the nature of existing evidence of a policy or EBI to address racism and equity, a range of hybrid effectiveness-implementation trials and systems modeling may be helpful in growing this evidence base (Chinman et al., 2017; McNulty et al., 2019); given that racism is reinforced across interconnected systems (e.g., housing, education, healthcare), a systems approach might help to identify potentially impactful leverage points with high potential for dismantling racism and promoting equity across the system (Brownson et al., 2021; Reskin, 2012). This may include evaluation of the implementation of innovations, practices, and policies already underway using natural experiments, adaptive designs, and rapid-cycle assessments. As policy plays a critical role in addressing structural racism, policy-focused implementation research may provide insight into the extent to which policies that promote or hinder health equity get implemented, enforced, sustained, and dynamically adapted over time (Emmons & Chambers, 2021; Hoagwood et al., 2020).

Qualitative methods amplify the voices and experiences of those affected by racism and unpack the intersection of multiple social identities (e.g., age, gender) that are proxies for structures affecting health through moderating access to power and privilege (Bowleg, 2017a, 2017b; Hamilton & Finley, 2019; Palinkas & Zatzick, 2019). Qualitative approaches may help document racism and unintended yet important contextual factors that shape the implementation of EBIs, as well as unplanned consequences, and the mechanisms through which policies and practices rooted in racism advantage some and disadvantage others (Bowleg et al., 2020; Griffith et al., 2017; Shelton et al., 2017).

Implementation Strategies: Applying an Antiracism Lens in Implementation Research Requires Application and Testing of Implementation Strategies to Advance Spread and Scale of Antiracist, Equity-focused Solutions

There is value in identifying, implementing, evaluating, and scaling implementation strategies seeking to promote equity and dismantle or attenuate the health effects of racism. Some strategies for promoting equity and antiracist policies/practices may align with existing implementation strategy taxonomies (e.g., ERIC taxonomy; Powell et al., 2015), including building equitable and diverse teams, building trust and community capacity, training/education, and organizational/policy change (Gaias et al., 2021; Gittelsohn et al., 2020; Hassen et al., 2021). However, there is a need for more development and testing of strategies grounded in antiracism principles and evaluation of impacts on equity. One strategy is clinician and practitioner training focused on critical self-reflection, power imbalances between professionals/providers and patients/communities, and recognition of structural racism in shaping health (Bailey et al., 2017; Came & Griffith, 2018; Duerme et al., 2021; Hardeman et al., 2016). While training alone is insufficient to dismantle racism when working in structurally racist systems (Griffith et al., 2007), it is an important component of multilevel antiracism strategies, and may improve uptake of EBIs that dismantle racism if it explicitly considers structural racism and helps professionals to apply an antiracism lens in their work.

Came and Griffith (2018) propose an antiracist framework to address public health inequities and inform institutional support and training of allies, with five elements: reflexive relational praxis (reflection and action), structural power analysis, socio-political education, monitoring/evaluation, and systems change approaches. We strongly encourage IS researchers and practitioners to explicitly test or learn how best to employ antiracist strategies in their work. For example, Browne et al. (2015) applied multilevel implementation strategies (organizational integration and tailoring, practice facilitation, staff training) to build capacity and support practice and policy changes within primary care and facilitate the provision of equity-oriented care in Canada (EQUIP, Research to Equip Primary Healthcare for Equity). To address structural determinants including racism, practitioners were trained on “cultural safety” to address power inequities and historical racial injustices. Browne et al. (2016) have also used an ethnographic approach to identify dimensions of equity-oriented healthcare and ten strategies as the foundation for organizational-level interventions that address power differentials and provide equitable, antiracist healthcare services for Indigenous populations.

Evaluation of implementation strategies that address institutional racism underlying racial inequities is another approach. As one IS-relevant example informed by CBPR, Cykert et al. (2020) conducted a pragmatic quality improvement (QI) trial across five cancer centers (ACCURE: The Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity) to address potential bias among clinicians shaping differential decision-making for Black and white patients. In addition to training medical and administrative staff on antiracism and healthcare equity (Black et al., 2019), researchers found that the use of a real-time electronic health record registry that signaled unmet care/missed appointments combined with race-specific measurement and clinical feedback on cancer treatments and nurse navigation enhanced treatment completion among breast/lung cancer patients and decreased racial inequities. Other promising health system studies have used implementation strategies (e.g., on-site coaching, facilitation, audit/feedback), race-specific data, and stakeholder engagement to build capacity around implementing evidence-based QI methods to target racial inequities (Cooper et al., 2013; Halladay et al., 2013; Purnell et al., 2016). Policy-oriented strategies that address outer contextual determinants that shape health inequities, including adaptive policies that are dynamic and based on a feedback system are also promising (Carey et al., 2015). These examples highlight opportunities to examine whether implementation strategies that promote or hinder health equity are equitably feasible, culturally acceptable, and effective across racial/ethnic groups, and how best to elucidate mechanisms through which strategies operate (e.g., directly or indirectly address racism).

Application of antiracism lens among researchers and within research contexts

Implementation research promoting health equity requires foundational and ongoing self-reflection, accountability, and attention to racial equity and racism consciousness (i.e., awareness of one’s racial position and positionality; Ford & Airhihenbuwa, 2010b; Smith, 2021). For some, it may be difficult to open themselves to think about racism. In these instances, Griffith and Semlow (2020) suggest utilizing art to facilitate understanding of what racism is, how it feels to experience privilege or oppression, and how to understand the implications of policies and practices that affect health. Self-reflection helps acknowledge one’s own racial, economic, cultural biases and privilege and combat systems of oppression within our disciplines and research (Griffith & Came, in press). Critical to antiracism is understanding the history and ongoing experiences of racism in broader societal contexts and in specific contexts in which we live and conduct research (Griffith et al., 2020a). Awareness of historical and ongoing socio-political contexts can contextualize deep-seated mistrust of medicine and public health. In the United States, this would include educating oneself about racial injustices, including the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2020), HeLa Cells from Henrietta Lacks (Skloot, 2017), and forms of racism (e.g., residential segregation, redlining) that have ongoing health implications (Hicken et al., 2019; Smith, 2021). Dismantling racism necessitates researcher reflection to identify where visible and invisible racist policies and processes are operating within and across systems.

We encourage IS researchers to employ antiracism approaches in their research. The Public Health Critical Race Praxis (PHCRP), based on Critical Race Theory (CRT), is one example of a grounding approach for assessing and addressing racism-related factors that may influence research conduct (Crenshaw et al., 1995; Ford & Airhihenbuwa, 2010a, 2010b, 2018). The PHCRP focuses on: (1) contemporary race relations (salience of structural racism during study time/context); (2) knowledge production (a field’s cumulative understandings including potential racial biases); (3) conceptualization/measurement (operationalization of racism-related variables, including intersectionality); and (4) action (how findings help to dismantle power differentials between community and researchers, benefit community, and build off of community assets). Application of PHCRP benefits implementation researchers as it encourages recognition that racism may underlie assumptions, methods, and theories, and facilitates racial consciousness around how aspects of racial context and inequitable power differentials influence research (e.g., how race or racism shape framing of research questions or funding) and disciplinary norms. Further, it grounds the work in the lived experiences of populations that have been marginalized (“Centering in the Margins”; Bradley, 2020; Ford & Airhihenbuwa, 2010a).

There is value in having implementation researchers engage in ongoing critical self-reflection, as it shapes our field, research, and communication. For example, are we using inclusive language to reflect diverse communities? What biases, power, and experiences do we bring to research? This includes opportunities to create spaces within our teams and partnerships for collective reflection. An antiracism lens includes an analysis of power and how the access and ability to leverage power varies by race/ethnicity (Came & Griffith, 2018). Building off of the work of Lukes (1974, 2005), researchers can critically examine how power is used within their research team and institutions regarding: (1) overt decision-making; (2) agenda setting and prioritization; and (3) shaping meaning and value. Informed by Freire’s (1972) pedagogical texts and CBPR, “reciprocal dialogues” applied in IS may enable stakeholders and researchers to collaborate to identify the root causes of inequities, and engage in ongoing reflection and dialogue. These concepts have implications for analyzing who has formal and informal power in our institutions and research, and determining how racism and power are operating, which includes: how inequities are framed and by who; who sets the agenda; whose voices are heard; what types of policies and research are valued and rewarded; and who benefits.

Conclusion

Implementation science is uniquely positioned to apply an antiracism lens in efforts to achieve population health equity. Here, we highlight opportunities to bring an antiracism lens to several core elements in implementation research and encourage the IS field to prioritize and reflect on the role we are playing in efforts to achieve health equity. Selecting frameworks or methods that do not consider racism, overlooking inequitable community-academic power dynamics in determining the evidence, conducting research that excludes settings and diverse racial/ethnic populations that face more structural barriers, and inattention to racial/ethnic patterns in our research are some ways that IS could inadvertently exacerbate health inequities. To be a part of the solution in helping to achieve racial/ethnic justice, IS needs to ground the field in extant scholarship on health equity and racism, and reframe a foundational focus on social justice, equity, and real-world impact.

To achieve these aims, we recognize that there are many more questions to address in IS. For example, what does it mean that dissemination efforts encouraging adoption typically focus on gatekeepers and those who already hold power? How could an antiracism approach facilitate the sustainability of EBIs? Could one of the reasons we struggle to sustain interventions, particularly, in communities experiencing inequities is because of the lack of examination of structural racism? What would it mean to center the values and experiences of individuals experiencing racism in adaptation and de-implementation efforts (Shelton et al., 2021b)? How has structural racism shaped the field of implementation science itself? We also recognize that while racism and its manifests are specific to particular historical and sociopolitical contexts (Came et al., 2019; Gee et al., 2019; Lentin, 2016), there is tremendous heterogeneity that exists within racial/ethnic groups and across geographic settings (e.g., urban or rural contexts; Zahnd et al., 2021) and globally, which require further explication.

It is important to acknowledge that our research is embedded within and influenced by broader institutions that form and influence research. This study requires commitment from funders and institutions to address racism and inequity in promoting and sustaining racially diverse scholars. We guide readers to pieces that have focused on this in more depth (Airhihenbuwa et al., 2019; Carnethon et al., 2020; Chaudhary & Berhe, 2020). Efforts are underway at the National Institutes of Health (NIH; Collins et al., 2021), including recent funding opportunities to examine the role of structural racism on health (NIH, 2021b, 2021d) that calls for information on addressing health equity (NIH, 2021c), and diversity/inclusion efforts to establish an equitable research workforce through the NIH UNITE initiative (NIH, 2021a). Racial diversity in the scientific workforce is central to addressing structural racism in IS, and structural changes are needed to enable the recruitment, support, and retention of a diverse workforce (Green et al., 2021; Yousif et al., 2020).

IS must also consider that some of the foundations and data that inform our field may not center on the principles of equity (e.g., race/ethnicity categories, standards for scientific “rigor” and “evidence”). Collaborating with stakeholders across disciplines (e.g., epidemiologists, clinical trialists) earlier along the research continuum with a focus on antiracism and equity is essential. Aligned with recent disciplinary critiques and recommendations for addressing structural racism in related fields (Alang et al., 2021; Bowleg, 2021; Boyd et al., 2020; Breland & Stanton, 2021; Buchanan et al., 2020; Hardeman & Karbeah, 2020; Merchant et al., 2021; South et al., 2020), we encourage implementation researchers to reflect critically and with care on their efforts around equity, invest in the implementation of policies, practices, and systems that are justice-centered, and consistently seize the opportunity to be more explicitly antiracist.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Savannah Alexander for assistance in formatting and references for this article. Dr. Shelton would like to acknowledge the work of the Collaborative for Anti-Racist Dissemination and Implementation Science (CARDIS) for creating a community for scholars and practitioners to support antiracism efforts. This study was prepared or accomplished by Dr. April Oh in her personal capacity. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States government.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: Dr. Griffith is funded by The American Cancer Society (RSG-15-223-01-CPPB), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (75,532), and NIIMHD (5U54MD010722-02). Dr. Shelton is funded by The American Cancer Society (131174-RSG-17-156-01-CPPB). Dr. Nathalie Moise is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01HS025198). The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the American Cancer Society (grant number 131174-RSG-17-156-01-CPPB, RSG-15-223-01-CPPB, NIIMHD, 75532).

ORCID iDs: Prajakta Adsul https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2860-4378

Nathalie Moise https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5660-5573

Derek M. Griffith https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0018-9176

References

- Adkins-Jackson P. B., Chantarat T., Bailey Z. D., Ponce N. A. (in press). Measuring structural racism: A guide for epidemiologists and other health researchers. American Journal of Epidemiology. 10.1093/aje/kwab239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins-Jackson P. B., Legha R. K., Jones K. A. (2021). How to measure racism in academic health centers. AMA Journal of Ethics, 23(2), E140–E145. 10.1001/amajethics.2021.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agénor M., Perkins C., Stamoulis C., Hall R. D., Samnaliev M., Berland S., Bryn Austin S. (2021). Developing a database of structural racism-related state laws for health equity research and practice in the United States. Public Health Reports, 136(4), 428–440. 10.1177/0033354920984168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airhihenbuwa C. O., Iwelunmor J. I., Ford C. L., Griffith D., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (2019). A call for leadership in tackling systemic and structural racism in the academy. In Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (Eds.), Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional (pp. 97–116). American Public Health Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alang S., Hardeman R., Karbeah J., Akosionu O., McGuire C., Abdi H., McAlpine D. (2021). White supremacy and the core functions of public health. American Journal of Public Health, 111(5), 815–819. 10.2105/ajph.2020.306137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz K. I., Wiedt T. L., Daniels E. C., Yabroff K. R., Guerra C. E., Wender R. C. (2020). Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: A blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70(1), 31–46. 10.3322/caac.21586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M., Wilhelm A., Ortega L. E., Pergament S., Bates N., Cunningham B. (2021). Applying a race(ism)-conscious adaptation of the CFIR framework to understand implementation of a school-based equity-oriented intervention. Ethnicity and Disease, 31(1), 375–388. 10.18865/ed.31.S1.375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alson J. G., Robinson W. R., Pittman L., Doll K. M. (2021). Incorporating measures of structural racism into population studies of reproductive health in the United States: A narrative review. Health Equity, 5(1), 49–58. 10.1089/heq.2020.0081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J., Nápoles A. M., Bernal G., Lloyd J., Cargill V., Godette D., Cooper L., Horse Brave Heart M. Y., Das R., Farhat T. (2019). Building the evidence base to inform planned intervention adaptations by practitioners serving health disparity populations. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S94–S101. 10.2105/ajph.2018.304915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annie E. Casey Foundation (Summer 2021). Bringing equity to implementation [Special supplement]. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 19(3), 1–31. https://ssir.org/supplement/bringing_equity_to_implementation [Google Scholar]

- Aschbrenner K. A., Mueller N. M., Banerjee S., Bartels S. J. (2021). Applying an equity lens to characterizing the process and reasons for an adaptation to an evidenced-based practice. Implementation Research and Practice, 2(Jan-Dec 2021), 1–8. 10.1177/26334895211017252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (2018). Promoting Health in all Policies: An Assessment of Cross-sector Collaboration Among State Health Agencies. https://www.astho.org/Prevention/Promoting-HiaP-An-Assessment-of-Cross-Sector-Collaborating-Among-State-Health-Agencies-2018/.

- Bailey Z. D., Feldman J. M., Bassett M. T. (2020). How structural racism works—Racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(8), 768–773. 10.1056/nejmms2025396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey Z. D., Krieger N., Agenor M., Graves J., Linos N., Bassett M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet (London, England), 389(10077), 1453–1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann A. A., Cabassa L. J. (2020). Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Services Research, 20, 190. 10.1186/s12913-020-4975-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendall C. L., Wilson D. M., Frison K. R., Inskip J. A., Camp P. G. (2016). A partnership for indigenous knowledge translation: Implementation of a first nations community COPD screening day. Canadian Journal of Respiratory Therapy, 52(4), 105–109. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30996618 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black K. Z., Baker S. L., Robertson L. B., Lightfoot A. F., Alexander-Bratcher K. M., Befus D., Cothern C., Dixon C. E., Ellis K. R., Guerrab F., Schaal J. C., Simon B., Smith B., Thatcher K., Wilson S. M., Yongue C. M., Eng E., Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., … Gilbert K. L. (2019). Health care: Antiracism organizing for culture and institutional change in cancer care. In Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (Eds.), Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional (pp. 283–314). American Public Health Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blas E., Kurup A. S. (Eds.). (2010). Equity, Social Determinants and Public Health Programmes. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnett A. (2000). Antiracism. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bor J., Venkataramani A. S., Williams D. R., Tsai A. C. (2018). Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of Black Americans: A population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet (London, England), 392(10144), 302–310. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. (2017a). Intersectionality: An underutilized but essential theoretical framework for social psychology. In Gough B. (Ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Social Psychology (pp. 507–529). Palgrave Macmillan/Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. (2017b). Towards a critical health equity research stance: Why epistemology and methodology matter more than qualitative methods. Health Education and Behavior, 44(5), 677–684. 10.1177/1090198117728760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. (2021). “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”: Ten critical lessons for Black and other health equity researchers of color. Health Education and Behavior, 48(3), 237–249. 10.1177/10901981211007402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L., Massie J. S., Holt S. L., Boone C. A., Mbaba M., Stroman W. A., Urada L., Raj A. (2020). The stroman effect: Participants in MEN Count, an HIV/STI reduction intervention for unemployed and unstably housed Black heterosexual men, define its most successful elements. American Journal of Men’s Health, 14(4), 1–16. 10.1177/1557988320943352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd R. W., Lindo E. G., Weeks L. D., McLemore M. R. (2020, July 2). On racism: A new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog. 10.1377/hblog20200630.939347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley C. (2020, November 19). A ruthless critique of everything: Possibilities for Critical Race Theory (CRT) in implementation science to achieve health equity [Conference presentation]. Consortium for Implementation Science Forum: Harnessing Implementation Science to Promote Health Equity, Remote due to COVID. https://consortiumforis.org/index.php/events/ [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P. A., Kumanyika S., Fielding J., Laveist T., Borrell L. N., Manderscheid R., Troutman A. (2011). Health disparities and health equity: The issue is justice. American Journal of Public Health, 101(S1), S149–S155. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breland J. Y., Stanton M. V. (2021). Anti-Black racism and behavioral medicine: Confronting the past to envision the future. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 10.1093/tbm/ibab090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A. J., Varcoe C., Ford-Gilboe M., Nadine Wathen C., Smye V., Jackson B. E., Wallace B., Pauly B. B., Herbert C. P., Lavoie J. G., Wong S. T., Blanchet Garneau A. (2018). Disruption as opportunity: Impacts of an organizational health equity intervention in primary care clinics. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17, 154. 10.1186/s12939-018-0820-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A. J., Varcoe C., Ford-Gilboe M., Wathen C. N. (2015). EQUIP Healthcare: An overview of a multi-component intervention to enhance equity-oriented care in primary health care settings. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14, 152. 10.1186/s12939-015-0271-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne A. J., Varcoe C., Lavoie J., Smye V., Wong S. T., Krause M., Tu D., Godwin O., Khan K., Fridkin A. (2016). Enhancing health care equity with indigenous populations: Evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 544. 10.1186/s12913-016-1707-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownson R. C., Colditz G. A., Proctor E. K. (Eds.). (2018). Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson R. C., Kumanyika S. K., Kreuter M. W., Haire-Joshu D. (2021). Implementation science should give higher priority to health equity. Implementation Science, 16, 28. 10.1186/s13012-021-01097-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan N. T., Perez M., Prinstein M., Thurston I. (2020). Upending racism in psychological science: Strategies to change how our science is conducted, reported, reviewed & disseminated. PsyArXiv. 10.31234/osf.io/6nk4x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Came H., Griffith D. (2018). Tackling racism as a “wicked” public health problem: Enabling allies in antiracism praxis. Social Science and Medicine, 199(Feb 2018), 181–188. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Came H., McCreanor T., Manson L. (2019). Upholding Te tiriti, ending institutional racism and crown inaction on health equity. New Zealand Medical Journal, 132(1492), 61–66. https://journal.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/upholding-te-tiriti-ending-institutional-racism-and-crown-inaction-on-health-equity [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey G., Crammond B., Malbon E., Carey N. (2015). Adaptive policies for reducing inequalities in the social determinants of health. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 4(11), 763–767. 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnethon M. R., Kershaw K. N., Kandula N. R. (2020). Disparities research, disparities researchers, and health equity. JAMA, 323(3), 211–212. 10.1001/jama.2019.19329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenat J. M. (2020). How to provide anti-racist mental health care. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(11), 929–931. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30309-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). The Tuskegee Timeline. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.

- Chaudhary V. B., Berhe A. A. (2020). Ten simple rules for building an antiracist lab. PLoS Computational Biology, 16(10), e1008210. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinman M., Woodward E. N., Curran G. M., Hausmann L. R. M. (2017). Harnessing implementation science to increase the impact of health equity research. Medical Care, 55(Suppl 9 2), S16–S23. 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowkwanyun M., Reed A. L., Jr. (2020). Racial health disparities and COVID-19—Caution and context. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(3), 201–203. 10.1056/NEJMp2012910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. S., Adams A. B., Aklin C., Archer T. K., Bernard M. A., Boone E., Burklow J., Evans M. K., Jackson S., Johnson A. C., Lorsch J., Lowden M. R., Nápoles A. M., Ordóñez A. E., Rivers R., Rucker V., Schwetz T., Segre J. A., Tabak L. A., Hooper M. W., Wolinetz C. (2021). Affirming NIH’s commitment to addressing structural racism in the biomedical research enterprise. Cell, 184(12), 3075–3079. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Díaz L. (2016). Racial trauma recovery: A race-informed therapeutic approach to racial wounds. In Alvarez A. N., Liang C. T. H., Neville H. A. (Eds.), The Cost of Racism for People of Color: Contextualizing Experiences of Discrimination (pp. 249–272). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L. A., Marsteller J. A., Noronha G. J., Flynn S. J., Carson K. A., Boonyasai R. T., Anderson C. A., Aboumatar H. J., Roter D. L., Dietz K. B., Miller E. R., Prokopowicz G. P., Dalcin A. T., Charleston J. B., Simmons M., Huizinga M. M. (2013). A multi-level system quality improvement intervention to reduce racial disparities in hypertension care and control: Study protocol. Implementation Science, 8, 60. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L. A., Purnell T. S., Engelgau M., Weeks K., Marsteller J. A. (2021). Using implementation science to move from knowledge of disparities to achievement of equity. In Dankwa-Mullan I., Pérez-Stable E. J., Gardner K. L., Zhang X., Rosario A. M. (Eds.), The Science of Health Disparities Research (pp. 289–308). Wiley-Blackwell. 10.1002/9781119374855.ch17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corburn J., Curl S., Arredondo G., Malagon J. (2015). Making health equity planning work: A relational approach in Richmond, California. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 35(3), 265–281. https://doi-org.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/10.1177/0739456X15580023 [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K., Gotanda N., Peller G., Thomas K. (Eds.). (1995). Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement. New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cross R. I., Ford C. L., Griffith D., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (2019). Appendix B: Selected measures of racism. In Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (Eds.), Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional (pp. 491–509). American Public Health Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cykert S., Eng E., Manning M. A., Robertson L. B., Heron D. E., Jones N. S., Schaal J. C., Lightfoot A., Zhou H., Yongue C., Gizlice Z. (2020). A multi-faceted intervention aimed at Black--white disparities in the treatment of early stage cancers: The ACCURE pragmatic quality improvement trial. Journal of the National Medical Association, 112(5), 468–477. 10.1016/j.jnma.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopp A. R., Parisi K. E., Munson S. A., Lyon A. R. (2020). Aligning implementation and user-centered design strategies to enhance the impact of health services: Results from a concept mapping study. Implementation Science Communications, 1, 17. 10.1186/s43058-020-00020-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerme R., Dorsinville A., McIntosh-Beckles N., Wright-Woolcock S. (2021). Rationale for the design and implementation of interventions addressing institutional racism at a local public health department. Ethnicity and Disease, 31(Suppl 1), 365–374. 10.18865/ed.31.S1.365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons K. M., Chambers D. A. (2021). Policy implementation science—An unexplored strategy to address social determinants of health. Ethnicity and Disease, 31(1), 133–138. 10.18865/ed.31.1.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng E., Blanchard L. (2006). Action-oriented community diagnosis: A health education tool. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 26(2), 141–158. 10.2190/8046-2641-7HN3-5637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng E., Strazza K., Rhodes S., Griffith D., Shirah K., Mebane E. (2012). Insiders and outsiders assess who is “the community”: Participant observation, key informant interview, focus group interview, and community forum. In Israel B., Eng E., Schulz A., Parker E. (Eds.), Methods for Conducting Community-based Participatory Research in Health (2nd ed., pp. 133–160). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Eslava-Schmalbach J., Garzón-Orjuela N., Elias V., Reveiz L., Tran N., Langlois E. V. (2019). Conceptual framework of equity-focused implementation research for health programs (EquIR). International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 80. 10.1186/s12939-019-0984-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etherington N., Rodrigues I. B., Giangregorio L., Graham I. D., Hoens A. M., Kasperavicius D., Kelly C., Moore J. E., Ponzano M., Presseau J., Sibley K. M., Straus S. (2020). Applying an intersectionality lens to the theoretical domains framework: A tool for thinking about how intersecting social identities and structures of power influence behaviour. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20, 169. 10.1186/s12874-020-01056-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. L., Airhihenbuwa C. O. (2010a). Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: Toward antiracism praxis. American Journal of Public Health, 100(S1), S30–S35. 10.2105/ajph.2009.171058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. L., Airhihenbuwa C. O. (2010b). The public health critical race methodology: Praxis for antiracism research. Social Science and Medicine, 71(8), 1390–1398. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. L., Airhihenbuwa C. O. (2018). Commentary: Just what is Critical Race Theory and what’s it doing in a progressive field like public health? Ethnicity and Disease, 28(1), 223–230. 10.18865/ed.28.S1.223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (Eds.). (2019). Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional. American Public Health Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. (1972). Pedagogy of the Oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). Continuum. (Orginial work published 1968).

- Freudenberg N., Tsui E. (2014). Evidence, power, and policy change in community-based participatory research. American Journal of Public Health, 104(1), 11–14. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove M. T., Hernandez-Cordero L., Madoff J. S., Fullilove R. E. (2004). Promoting collective recovery through organizational mobilization: The post-9/11 disaster relief work of NYC RECOVERS. Journal of Biosocial Science, 36(4), 479–489. 10.1017/s0021932004006741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaias L. M., Arnold K. T., Liu F. F., Pullmann M. D., Duong M. T., Lyon A. R. (2021). Adapting strategies to promote implementation reach and equity (ASPIRE) in school mental health services. Psychology in the Schools, 1–15. 10.1002/pits.22515 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galaviz K. I., Breland J. Y., Sanders M., Breathett K., Cerezo A., Gil O., Hollier J. M., Marshall C., Wilson J. D., Essien U. R. (2020). Implementation science to address health disparities during the coronavirus pandemic. Health Equity, 4(1), 463–467. 10.1089/heq.2020.0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G. C., Ford C. L. (2011). Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new directions. Du Bois Review, 8(1), 115–132. 10.1017/S1742058X11000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G. C., Sangalang C. C., Morey B. N., Hing A. K., Ford C. L., Griffith D., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (2019). The global and historical nature of racism and health among Asian Americans. In Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (Eds.), Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional (pp. 393–412). American Public Health Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gittelsohn J., Belcourt A., Magarati M., Booth-LaForce C., Duran B., Mishra S. I., Belone L., Jernigan V. B. B. (2020). Building capacity for productive indigenous community-university partnerships. Prevention Science, 21(Suppl 1), 22–32. 10.1007/s11121-018-0949-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow L. M. (2020, June 9). Beyond lip service: Taking a genuine approach to tackling COVID-19 (and all) Black-white health disparities in the United States. Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200604.585088/full/.

- Green L. W. (2008). Making research relevant: If it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Family Practice, 25(Suppl 1), i20–i24. 10.1093/fampra/cmn055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green T. L., Zapata J. Y., Brown H. W., Hagiwara N. (2021). Rethinking bias to achieve maternal health equity: Changing organizations, not just individuals. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 137(5), 935–940. 10.1097/aog.0000000000004363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Came H. (in press). Antiracism praxis: A community organizing approach to achieve health and social equity. In Minkler M., Wakimoto P. (Eds.), Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Social Equity (4th ed.). Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Semlow A. R. (2020). Art, antiracism and health equity: “Don’t ask me why, ask me how!”. Ethnicity and Disease, 30(3), 373–380. 10.18865/ed.30.3.373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Bergner E. M., Fair A. S., Wilkins C. H. (2020a). Using mistrust, distrust, and low trust precisely in medical care and medical research advances health equity. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 60(3), 442–445. 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Holliday C. S., Enyia O. K., Ellison J. M., Jaeger E. C. (2021). Using syndemics and intersectionality to explain the disproportionate COVID-19 mortality among Black men. Public Health Reports, 136(5), 523–531. 10.1177/00333549211026799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Jaeger E. C., Bergner E. M., Stallings S., Wilkins C. H. (2020b). Determinants of trustworthiness to conduct medical research: Findings from focus groups conducted with racially and ethnically diverse adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(10), 2969–2975. 10.1007/s11606-020-05868-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Mason M., Yonas M., Eng E., Jeffries V., Plihcik S., Parks B. (2007). Dismantling institutional racism: Theory and action. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39(3-4), 381–392. 10.1007/s10464-007-9117-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith D. M., Shelton R. C., Kegler M. (2017). Advancing the science of qualitative research to promote health equity. Health Education and Behavior, 44(5), 673–676. 10.1177/1090198117728549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groos M., Wallace M., Hardeman R., Theall K. P. (2018). Measuring inequity: A systematic review of methods used to quantify structural racism. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 11(2), 190–206. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1792&context=jhdrp [Google Scholar]

- Gross C. P., Essien U. R., Pasha S., Gross J. R., Wang S. Y., Nunez-Smith M. (2020). Racial and ethnic disparities in population-level COVID-19 mortality. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(10), 3097–3099. 10.1007/s11606-020-06081-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halladay J. R., Donahue K. E., Hinderliter A. L., Cummings D. M., Cene C. W., Miller C. L., Garcia B. A., Tillman J., DeWalt D. (2013). The heart healthy lenoir project-An intervention to reduce disparities in hypertension control: Study protocol. BMC Health Services Research, 13, 441. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A. B., Finley E. P. (2019). Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Research, 280(Oct 2019), 112516. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman R. R., Hardeman-Jones S. L., Medina E. M. (2021). Fighting for America’s paradise-The struggle against structural racism. Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law, 46(4), 563–575. 10.1215/03616878-8970767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman R. R., Karbeah J. (2020). Examining racism in health services research: A disciplinary self-critique. Health Services Research, 55(S2), 777–780. 10.1111/1475-6773.13558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardeman R. R., Medina E. M., Kozhimannil K. B. (2016). Dismantling structural racism, supporting Black lives and achieving health equity: Our role. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(22), 2113–2115. 10.1056/NEJMp1609535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnett N. G., Ressler K. J. (2021). Structural racism as a proximal cause for race-related differences in psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(7), 579–581. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21050486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassen N., Lofters A., Michael S., Mall A., Pinto A. D., Rackal J. (2021). Implementing anti-racism interventions in healthcare settings: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 2993. 10.3390/ijerph18062993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P. (2015). Minimal, negligible and negligent interventions. Social Science and Medicine, 138(Aug 2015), 265–268. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P., Shiell A., Riley T. (2009). Theorising interventions as events in systems. American Journal of Community Psychology, 43(3-4), 267–276. 10.1007/s10464-009-9229-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich C. D., Hartmann C. W., Parikh T. J., Au D. H. (2019). Promoting health equity through de-implementation research. Ethnicity and Disease, 29(Suppl 1), 93–96. 10.18865/ed.29.S1.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicken M. T., Burnside L., Edwards D. L., Lee H., Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (2019). Black–white health inequalities by intentional design: The lasting health impact of racial residential segregation. In Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (Eds.), Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional (pp. 117–132). American Public Health Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K. E., Purtle J., Spandorfer J., Peth-Pierce R., Horwitz S. M. (2020). Aligning dissemination and implementation science with health policies to improve children’s mental health. American Psychologist, 75(8), 1130–1145. 10.1037/amp0000706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B. A., Schulz A. J., Parker E. A., Becker A. B. (2003). Critical issues in developing and following community-based participatory research principles. In Minkler M., Wallerstein N. (Eds.), Community-based Participatory Research for Health (pp. 47–62). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Kegler M. C., Wolff T., Christens B. D., Butterfoss F. D., Francisco V. T., Orleans T. (2019). Strengthening our collaborative approaches for advancing equity and justice. Health Education and Behavior, 46(1S), 5S–8S. 10.1177/1090198119871887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Key K. D., Furr-Holden D., Lewis E. Y., Cunningham R., Zimmerman M. A., Johnson-Lawrence V., Selig S. (2019). The continuum of community engagement in research: A roadmap for understanding and assessing progress. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 13(4), 427–434. 10.1353/cpr.2019.0064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh S., Lee M., Brotzman L. E., Shelton R. C. (2020). An orientation for new researchers to key domains, processes, and resources in implementation science. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(1), 179–185. 10.1093/tbm/iby095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. (2014). Discrimination and health inequities. International Journal of Health Services, 44(4), 643–710. 10.2190/HS.44.4.b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. (2020). Measures of racism, sexism, heterosexism, and gender binarism for health equity research: From structural injustice to embodied harm-An ecosocial analysis. Annual Review of Public Health, 41, 37–62. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N., Ford C. L., Griffith D., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (2019). Epidemiology—Why epidemiologists must reckon with racism. In Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (Eds.), Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional (pp. 249–266). American Public Health Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N., Smith K., Naishadham D., Hartman C., Barbeau E. M. (2005). Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science and Medicine, 61(7), 1576–1596. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krist A. H., Davidson K. W., Ngo-Metzger Q., Mills J. (2019). Social determinants as a preventive service: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force methods considerations for research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57(6), S6–S12. 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBrón A. M. W., Viruell-Fuentes E. A. (2019). Racism and the health of Latina/Latino communities. In Ford C. L., Griffith D. M., Bruce M. A., Gilbert K. L. (Eds.), Racism: Science and Tools for the Public Health Professional (pp. 413–428). American Public Health Association Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Tauler S. Y., Eun J., Corbett D., Collins P. Y. (2018). A systematic review of interventions to improve initiation of mental health care among racial-ethnic minority groups. Psychiatric Services, 69(6), 628–647. 10.1176/appi.ps.201700382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentin A. (2016). Racism in public or public racism: Doing antiracism in ‘post-racial’ times. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39(1), 33–48. 10.1080/01419870.2016.1096409 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lukes S. (1974). Power: A Radical Review. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lukes S. (2005). Power: A Radical Review (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]