Abstract

Background:

Responding to the growing demand for scientific understanding of adoption and uptake of evidence-based interventions (EBIs), numerous dissemination and implementation (“D&I”) models have been proposed in the extant literature. This review aimed to identify community-specific constructs with the potential to help researchers engage community partners in D&I studies or deploy EBIs.

Methods:

We identified 74 D&I models targeting community-level changes. We built on Tabak et al.’s narrative review that identified 51 D&I models published up to 2012 and identified 23 D&I models published between 2012 and 2020 from the Health Research & Practice website (16 models) and PubMed database (7 models). Three coders independently examined all 74 models looking for community-specific engagement constructs.

Results:

We identified five community engagement constructs: (1) Communication, (2) Partnership Exchange, (3) Community Capacity Building, (4) Leadership, and (5) Collaboration. Of the 74 models, 20% reflected all five constructs; 32%, four; 22%, three; 20%, two; and 5%, only one. Few models with strong community content have been introduced since 2009.

Conclusion:

This article bridges the community-engaged and D&I research literature by identifying community engagement constructs reflected in existing D&I models, targeting community-level changes. Implications for future research and practice are discussed.

Plain language summary

Responding to the growing demand for scientific understanding of adoption and uptake of evidence-based interventions (EBIs), numerous dissemination and implementation (“D&I”) models have been proposed. This review aimed to identify community-specific constructs with the potential to help researchers engage community partners in D&I studies or deploy EBIs. We identified 74 D&I models targeting community-level changes, published between 2012 and 2020. Three coders independently examined all 74 models looking for community-specific engagement constructs. We identified five community engagement constructs: (1) Communication, (2) Partnership Exchange, (3) Community Capacity Building, (4) Leadership, and (5) Collaboration. Of the 74 models, 20% reflected all five constructs; 32%, four; 22%, three; 20%, two; and 5%, only one. This article identified community engagement constructs reflected in existing D&I models targeting community-level changes. Implications for future research and practice are discussed.

Keywords: Dissemination and implementation models, narrative review, community engagement, community change, community-engaged research and practice

Scientific findings that may improve the adoption (by practitioners) and uptake (by patients) of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) take up to two decades to reach the health care workforce—physicians, nurses, social workers, health educators, and others—responsible for their implementation (Institute of Medicine, 2001; World Health Organization, 2006). This workforce is ethically obligated to offer the latest EBIs to improve patient-level health outcomes and the public’s health (American Medical Association, 2016; National Association of Social Workers, 2017; Public Health Leadership Society, 2002). To improve the dissemination and implementation (D&I) of EBIs, in tandem with the field of community-engaged research, implementation science has focused on the study of methods for improving the systematic incorporation of research findings into health care policy and routine practice, and adoption and uptake of EBIs (Eccles & Mittman, 2006; National Information Center on Health Services Research and Health Care Technology, 2016). Globally, community-engaged research is the leading paradigm with theoretical and empirical foundations to help researchers and practitioners to advance D&I readiness and to develop approaches that can enhance the acceptability of EBIs by vulnerable communities (Blevins et al., 2010; James et al., 2013; Maar et al., 2015).

The D&I of EBIs have been described as theories, frameworks, or models (Nilsen, 2015; Tabak et al., 2012). Theories are generally defined as a set of principles intended to help us understand phenomena by defining a set of variables, how they relate to each other, and how they might be used for predictive analysis (Carpiano & Daley, 2006; Dubin, 1978). A framework summarizes variables and the relationships between them without necessarily explaining the phenomenon they represent (Frankfort-Nachmias & Nachmias, 1996; Sabatier, 2007). A model is a simplification of phenomena; less accurate than theories, they are more flexible as researchers can add or eliminate variables to make the model more applicable to a specific phenomenon (Carpiano & Daley, 2006). Theories, frameworks, and models aiming to describe and explain D&I efforts will be referred to as “D&I models” from this point forward (Bartholomew et al., 2011; Glanz & Bishop, 2010; Palinkas & Soydan, 2012; Rabin & Brownson, 2012).

The D&I literature encourages researchers to work collaboratively with community representatives, including residents, practitioners, politicians, and other stakeholders. This perspective reflects the community-engaged literature suggesting that researchers and community partners, with complementary knowledge/skills (e.g., methods, procedures, dissemination strategies), ought to work together to design, evaluate, disseminate, and implement EBIs (Israel et al., 1998; Pinto et al., 2011, 2015; Proctor et al., 2009). This is because community partnerships promote better retention of research participants, EBI adoption/acceptability, trust between communities and researchers, and diffusion of EBIs under “real-world” conditions (Viswanathan et al., 2004). Therefore, it is imperative that researchers examine existing D&I models to unearth variables/constructs that may facilitate engagement of community partners and assist researchers and practitioners alike to work out their differences concerning research priorities that may ultimately influence D&I efforts (Flaspohler et al., 2012).

Existing D&I models are not always grounded in community-engaged principles or practices (Matheson et al., 2015; Oh, 2018). Even those models attempting to use a community-focused approach often fail to identify key constructs that can optimize community engagement and deployment of D&I studies. Compelling empirical evidence that might help researchers choose one D&I model over another is still developing. A large number of models now available can make such a decision more complex. The decision on what model to choose mostly competes for which model is the most comprehensive, which may be translated into being the least pragmatic. Therefore, we sought to isolate D&I models with specific relevance for community engagement. Guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Moher et al., 2009), the current narrative review focuses on bridging community-engaged and D&I research by unearthing community engagement constructs reflected in existing D&I models. Findings from this review also have implications concerning the de-implementation of EBIs, a needed subject of research still in its infancy (McKay et al., 2018; Pinto & Witte, 2019).

Community-engaged and D&I research

Community-engaged research is a leading theoretical and empirical paradigm for improving D&I readiness, for evaluating partnerships between researchers and community (e.g., service providers and service consumers), and for developing optimal strategies for D&I of health and behavioral interventions (Blevins et al., 2010; James et al., 2013; Maar et al., 2015). Research on D&I, whose key aims are to identify best practices for community involvement, continues to be a public health priority worldwide (Cunningham & Card, 2014; World Health Organization, 2017). Engaging in partnerships with researchers may inspire practitioners to adopt/use scientific evidence to guide practice and inspire service consumers to trust/use EBIs to improve their health (Viswanathan et al., 2004). Practitioners personally involved in research (e.g., collected data, recruited participants) are more willing to use scientific evidence than their peers without such experience (Pinto et al., 2010; Pinto, 2013). Professional, ethical standards dictate that service consumers must receive up-to-date services and that practitioners must use current knowledge in their day-to-day practices (American Medical Association, 2016; National Association of Social Workers, 2017; Public Health Leadership Society, 2002). Researchers looking to develop partnerships with community stakeholders need to learn the community’s history, norms, and values and be upfront about the history of abuses by researchers who have participated in the stigmatization of the very communities they study—this can help build trust and consensus on priorities (George et al., 2014; Pinto et al., 2008). Other challenges include researchers’ unwillingness to compensate community partners monetarily, social imbalances in power- and knowledge-sharing, and concerns about dissemination of research findings in formats unfriendly to the community (Ion et al., 2019; J. (Langley et al., 2018; Samuel et al., 2018). These barriers are less problematic when researchers avail themselves of open communication and equitable leadership, collaboration with an eye toward community capacity-building, and information exchanges (Israel et al., 1998; Pinto et al., 2011, 2015).

Methods

We examined existing D&I models looking for constructs that might facilitate community engagement in D&I efforts. We build on Tabak and colleagues’ (2012) narrative review, which has advanced the field of D&I in several ways, including by identifying D&I models published up to 2012. Fifty-one models were recommended for studies targeting community-level changes. Unfortunately, this review did not provide evidence of what constructs for community engagement might be reflected in the models. Therefore, we updated the list of D&I models to 2020 and have assessed 74 D&I models to identify key constructs that might influence community engagement. This is not a systematic review; therefore, we have not registered a protocol.

Updating the inventory of D&I models

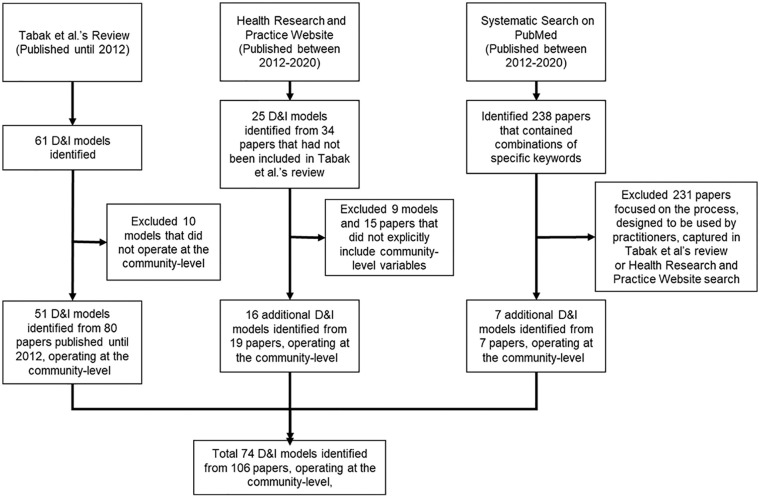

We used three different strategies to identify and update the existing inventory of D&I models published up to 2020 (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the Review

We adopted the list of D&I models published in the narrative review conducted by Tabak and colleagues (2012). Tabak et al. used snowball sampling, expert consultation, categorical placeholders, and secondary expert consultation. They prioritized their experiences to identify experts in the field who could help them find all available D&I models. Their review included models in the peer-reviewed literature on innovation, organizational behaviors, and research utilization. Out of 61 D&I models, Tabak et al. identified 51 as targeting community-level changes. We retained all 51 models and their associated 80 papers for further analyses.

To identify D&I models operating at the community-level published after 2012, we consulted (November 2020) the Health Research & Practice website (Center for Research in Implementation Science and Prevention, 2019), supported by the National Cancer Institute’s Implementation Science team and co-developed by the Center for Research in Implementation Science and Prevention through Adult and Child Center for Health Outcomes Research and Delivery Science and the Washington University Network for Dissemination and Implementation Research. From this website, we identified 25 D&I models and 34 associated papers not included in Tabak et al.’s review. Based on Tabak et al.’s (2012) inclusion criteria, two coders independently made decisions to keep or eliminate a particular paper/model, and a third coder resolved disagreements. Such criteria included descriptions/explanations of behaviors and social phenomena in the development, management, testing, dissemination, and implementation of evidence-based practices. We excluded nine models (15 papers) that did not explicitly target changes at the community level. Thus, 16 papers about 119 models were retained for further analysis.

To identify D&I models that might have appeared outside the Health Research & Practice website, we searched for models published after 2012. We searched PubMed, which contains peer-reviewed papers in the health field, where D&I is widely discussed. PubMed contains more than 23 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books, and it includes papers at different stages of the publishing process. As the primary goal of this review was not to identify every ever-published paper reporting on D&I models, we did not engage in the lengthy and unpredictable process of comparing databases. Even though we may have missed some papers, we do not have any reason to believe that this compromised the results here. We used the following search scheme:

“dissemination” OR “implementation” AND “evidence-based practices” AND “community” under the category “Title/Abstract.”

We added a filter for publication dates between 2012 and 2020 (the most updated possible). We used the term “community” aiming to capture D&I models operating at the community level.

Our search yielded 238 hits. Grounded in the selection criteria used by Tabak et al. (listed above), we reviewed each of these papers. All papers that focused exclusively on the process (e.g., barriers and facilitators) and models designed to be used by practitioners were eliminated. Studies that reported on the integration of existing models already accounted for in Tabak et al.’s review were eliminated as well. Decisions to keep or eliminate a particular paper/model were made independently by two coders, and a third coder resolved disagreements. From this process, we identified seven papers containing features of D&I operating at the community level and retained seven new models for further analyses.

Summary of model selection

For the models identified from Tabak et al.’s (2012) paper, we reviewed the papers included in the original review. For the models identified from the https://dissemination-implementation.org/ website, we included the original publication(s) of the model, identified on the website. For the models identified from the systemic review, we reviewed every paper relevant to the analysis.

Our review included 74 models (51 models from Tabak et al.’s (2012) review, 16 from the Health Research & Practice website, and seven from PubMed). We identified these models in 106 papers (80 papers from Tabak et al.’s review, 19 from the Health Research & Practice website, and seven from PubMed). The number of models is smaller than the number of papers because the same models may have appeared in several papers. Therefore, we report on the constructs that we found in each model—for example, an earlier version of a given model may have a different number of one or another construct on community engagement. All 74 models were retained for analysis. We used the PRISMA Flow Diagram (Moher et al., 2009) (Figure 1) to summarize how we arrived at 106 papers and 74 models.

Analysis

Our first step was to extract a definition of the term “community” that would reflect D&I models targeting changes at the community level. After careful consideration, we adopted Mendel et al.’s (2008) definition. This definition gave us a baseline to which we could contrast other models’ representations of the term “community” and their inclusion of key actors:

“Community” refers to a group of people or organizations defined by function (such as an industry), geography (such as a metropolitan area), shared interests or characteristics (such as ethnicity, sexual orientation, or occupation), or by a combination of these dimensions (Fellin, 2001; Scott, 1994), in which members share some sense of identity or connection (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Schulz et al., 2003). Here, we specify a community in terms of stakeholders in the provision and receipt of health care within a bounded, geographic area in order to emphasize capacity building (Jones & Wells, 2007) and processes of “collective efficacy” (Sampson, 2003; Sampson et al., 1997) that facilitate action at the local level. (Mendel et al., 2008, p. 23)

The second step was to analyze 10 randomly selected models to identify community engagement constructs—sensitizing concepts, terms, and/or defined variables. Blinded to which model we were examining, we searched for constructs reflecting the actual and/or suggested involvement of community partners in the D&I models. After examining the 10 randomly selected models, the coders met for three 2-hr sessions to discuss the most salient constructs across the models. We brought to these discussions our experiences as community members, practitioners, and researchers (Pinto et al., 2011, 2015). Our expertise helped us identify constructs known to facilitate community involvement in scientific research: (1) Communication, (2) Partnership Exchange, (3) Community Capacity-Building, (4) Leadership, and (5) Collaboration. We developed a codebook with definitions reflecting the purpose—community-level changes—of the models we examined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Codebook of community engagement constructs and definitions.

| Strategy | Definition |

|---|---|

| Communication | Communication between community stakeholders and representatives (residents, practitioners, politicians, and others) and researchers conducting D&I research. “Good communication” is guided by mutually understood values and guidelines and occurs through different means, including scheduled meetings, formal consultations, Memoranda of Understanding, and other strategies. |

| Partnership exchange | Partnership Exchange involves the specific trading of knowledge, skills, and various concrete resources (e.g., funding, books, space) between researchers, stakeholders, and potential users of knowledge generated by research and D&I efforts. The exchange often involves the elements of communication described above. |

| Community capacity-building | Community Capacity-Building is at once a process and an outcome of partnerships and collaborations that manifests in myriad ways, such as community development, job creation, political and social capital, and sustainability of D&I efforts. |

| Leadership | Leadership emanating from credible, well-positioned, influential figures and experts within the community who are invited to share their expertise and power in decision-making concerning D&I efforts. |

| Collaboration | Collaboration between stakeholders who share similar values and occupy stated roles in the partnership (e.g., paid positions) and who participate in all phases of D&I efforts to develop methods and procedures that are beneficial to both researchers and community members. |

Note. D&I = dissemination and implementation.

Third, using the codebook, coders independently marked all models for the presence of the constructs (zero to five). Each model was independently and blindly coded by two persons, who, after coding each model, met for scheduled meetings to discuss their findings and plan for subsequent analyses. For example, early in these discussions, we realized that the models varied widely in how their authors explicitly/implicitly mentioned a particular construct. Often, we had to apply the codebook definitions to text that did not mention the actual words we used to name the constructs, but which text, nonetheless, evoked the sentiment behind the definitions. Independent coders rigorously marked a model reflecting a specific construct only when the paper contained terms, themes, words, and/or segments related to that concept.

Another form of rigor was achieved by holding ten 60-min discussion sessions with a third coder, who reviewed the coding done by the original two independent coders. This technique was helpful in several ways. For example, arriving at the definition of “partnership exchange” was difficult because, at times, we considered collapsing it with “communication.” However, after a three-way discussion, we decided on two separate terms, because “exchange” to us represented a dynamic process that included “communication” between partners. We discussed all cases, and we came to 100% agreement after reviewing and deliberating on discrepancies. Finally, we calculated the frequency that each of the five themes appeared in each of the models.

Results

In chronological order, Table 2 summarizes the 74 D&I models we examined and the papers from which they came. We present the models in chronological order so that the reader can examine how they developed over time. Table 3 lists community engagement constructs found in each of 74 D&I models. Four (5.4%) of the models reflected only one construct—that is, Communication or Partnership Exchange. Fifteen (20.3%) models reflected two constructs, and 16 (21.6%) models reflected three constructs—the most common being Communication and Partnership Exchange. Twenty-four (32.4%) models reflected four constructs—all contained Partnership Exchange, and all but three mentioned Communication. At least half of the models in this category reflected Leadership, Community Capacity-Building, and Collaboration. Fifteen (20.3%) models reflected all five constructs. Partnership Exchange appeared in most models (91.9%), followed by Communication (78.4%), Community Capacity-Building (62.2%), Leadership (56.8%), and Collaboration (52.7%).

Table 2.

Community engagement constructs in dissemination and implementation models.

| Model title | Year first published | Community Engagement Constructs | Reference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | Partnership exchange | Community capacity-building | Leadership | Collaboration | Total | |||

| Research development dissemination and utilization framework | 1969 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Havelock (1969) |

| Streams of policy process | 1984 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Kingdon (1984, 2010) |

| RAND model of persuasive communication and diffusion of medical innovation | 1985 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Winkler et al. (1985) |

| Model for improving the dissemination of nursing research | 1989 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | Funk et al. (1989) |

| Real-world dissemination | 1992 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Chambers and Dopson (2003); Pettigrew et al. (1992) |

| Conceptual model of knowledge utilization | 1993 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Lester (1993) |

| Convergent diffusion and social marketing approach to dissemination | 1996 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Dearing (1996); Dearing et al. (2006) |

| Sticky knowledge | 1996 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | Elwyn et al. (2007); Szulanski (1996) |

| Health promotion technology transfer process | 1996 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Orlandi (1996) |

| Davis’ Pathman-PRECEED model | 1996 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | D. Davis et al. (2003); Green and Kreuter (2005); Pathman et al. (1996) |

| Community-based participatory research (CBPR)a | 1998 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Israel et al. (1998, 2005); Leykum et al. (2009) |

| Intervention mappinga | 1998 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | Bartholomew et al. (1998) |

| Promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) | 1998 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Kitson et al. (1998, 2008); Rycroft-Malone (2004) |

| OutPatient treatment in Ontario services (OPTIONS) model | 1998 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Martin et al. (1998) |

| Ottawa model of research use | 1998 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Logan and Graham (1998, 2010) |

| RE-AIM framework | 1999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Glasgow et al. (1999) |

| Model for locally based research transfer development | 1999 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Anderson et al. (1999) |

| CDC DHAP’s research-to-practice framework | 2000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | Collins et al. (2006, 2007, 2012); Neumann and Sogolow (2000); Sogolow et al. (2000, 2002) |

| Technology transfer modela | 2000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Kraft et al. (2000) |

| Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health carea | 2002 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Cooper et al. (2002) |

| Framework for the dissemination and utilization of research for health care policy and practice | 2002 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Dobbins et al. (2002, 2010) |

| Effective dissemination strategies | 2002 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Scullion (2002) |

| “4E” framework for knowledge dissemination and utilization | 2003 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Farkas et al. (2003); Farkas and Anthony (2007) |

| Diffusion of innovation | 2003 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Rogers (2003) |

| Conceptualizing dissemination research and activity: Canadian heart health initiative | 2003 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Elliott et al. (2003); Riley et al. (2009) |

| Research knowledge infrastructure | 2003 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Ellen et al. (2011); Lavis (2006); Lavis et al. (2003); Reardon et al. (2006) |

| Framework for knowledge translation | 2003 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Jacobson et al. (2003) |

| Conceptual model for the diffusion of innovations in service organizations | 2004 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Greenhalgh et al. (2004) |

| Active implementation framework | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Fixsen et al. (2005); National Implementation Research Network (2019) |

| Linking systems framework | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Robinson et al. (2005) |

| Availability, responsiveness & continuity (ARC): An organizational community intervention model | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Glisson et al. (2010); Glisson and Schoenwald (2005) |

| PRECEDE-PROCEED model | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Green and Kreuter (2005) |

| Framework for spread | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | G. J. Langley et al. (2009); Nolan et al. (2005) |

| Framework for translating evidence into actiona | 2005 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | Swinburn et al. (2005) |

| Explaining behavior change in evidence-based practicea | 2005 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Michie et al. (2005) |

| Pathways to evidence-informed policy | 2005 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Bowen and Zwi (2005) |

| Push-pull capacity model | 2006 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Green et al. (2006) |

| Policy framework for diffusion of evidence-based physical activity interventions | 2006 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Owen et al. (2006) |

| Six-step framework for international physical activity dissemination | 2006 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Bauman et al. (2006) |

| Advancing health disparities research within the health care systema | 2006 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Kilbourne et al. (2006) |

| Framework for analyzing adoption of complex health innovations | 2007 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Atun et al. (2007, 2010) |

| Replicating effective programs plus framework | 2007 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | Kilbourne et al. (2007) |

| Stages of research utilization modela | 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | S. M. Davis et al. (2007); Peterson et al. (2007) | |

| Facilitating adoption of best practices (FAB) model | 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Damush et al. (2008) |

| Translational research framework to address health disparitiesa | 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Fleming et al. (2008) |

| Framework of dissemination in health services intervention research | 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Mendel et al. (2008) |

| Caledonian practice development modela | 2008 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | Tolson et al. (2008) |

| Interactive systems framework | 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | Wandersman et al. (2008) |

| Pronovost’s 4E process theory | 2008 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Pronovost et al. (2008) |

| Utilization-focused surveillance framework | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Green et al. (2009) |

| Conceptual model of implementation research | 2009 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Proctor et al. (2009) |

| Consolidated framework for implementation research | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | Damschroder (2014; Damschroder et al. (2009) |

| Knowledge exchange framework | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | Ward et al. (2009a, 2009b, 2012) |

| Normalization process theory | 2009 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | May et al. (n.d.); May and Finch (2009); Murray et al. (2010) |

| Translational framework for public health researcha | 2009 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Ogilvie et al. (2009) |

| Blueprint for dissemination | 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Yuan et al. (2010) |

| Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) model (Conceptual Model of Evidence-based Practice Implementation in Public Service Sectors) | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Aarons et al. (2011) |

| Interacting elements of integrating science, policy, and practice | 2011 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | TIDIRH Working Group (2011) |

| Health promotion research center framework | 2011 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Harris et al. (2011) |

| Behavior change wheela | 2011 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Michie et al. (2011) |

| Framework for dissemination of evidence-based policy | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | Dodson et al. (2012) |

| Dissemination of evidence-based interventions to prevent obesity | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Dreisinger et al. (2012) |

| Evidence integration trianglea | 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Glasgow et al. (2012) |

| Marketing and distribution system for public health | 2012 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Kreuter et al. (2012) |

| Dynamic sustainability frameworka | 2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Chambers et al. (2013) |

| AIMS modelb | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Smith et al. (2014) |

| Framework for enhancing the value of research for dissemination and implementationa | 2015 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Neta et al. (2014) |

| Community-based learning collaborative modelb | 2016 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Hanson et al. (2016) |

| Interactive knowledge to action frameworkb | 2016 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Rütten et al. (2016) |

| Policy ecology frameworkb | 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Powell et al. (2016) |

| Community-based learning collaborative modelb | 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | Hanson et al. (2019) |

| Obesity prevention and evaluation of interVention effectiveness in NaTive North Americans (OPREVENT)b | 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Redmond et al. (2019) |

| Lay health workers enhancing engagement for parents (LEEP)b | 2019 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | Barnett et al. (2019) |

| Health equity implementation frameworka | 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Woodward et al. (2019) |

Note. Unmarked models were identified from Tabak et al.’s (2012) review paper. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DHAP = Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention; RE-AIM = reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance;

Identified from the Health Research & Practice website search. b Identified from PubMed database search.

Table 3.

Dissemination and implementation models containing community engagement constructs.

| Number of constructs | Number of models | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 5.4 |

| 2 | 1 | 20.3 |

| 3 | 16 | 21.6 |

| 4 | 24 | 32.4 |

| 5 | 15 | 20.3 |

| Total | 74 | 100.0 |

| Strategy type | ||

| Communication | 58 | 78.4 |

| Partnership exchange | 68 | 91.9 |

| Community capacity-building | 46 | 62.2 |

| Leadership | 42 | 56.8 |

| Collaboration | 39 | 52.7 |

Discussion

Several reviews of D&I models have been published in the past decade. Most scoping reviews describe D&I models based on expected changes at various levels—individual, organization, community, and policy level. These reviews contribute to the literature by identifying common elements in various D&I models and by concluding, by and large, that there is a vast number of D&I models, but the majority of them are too complex and therefore of limited use (Nilsen, 2015; Reed et al., 2019; Strifler et al., 2018). Nonetheless, these reviews have not offered enough guidance for researchers and practitioners who intend to design and implement D&I models. We have narrowed this gap by analyzing D&I models with an eye specifically toward the use of models operating at community-level changes.

Bridging community-engaged and D&I approaches

This review helps bridge the community-engaged and D&I research literature by identifying community engagement constructs reflected in existing D&I models targeting community-level changes. This article is grounded in a narrative review where Tabak and colleagues (2012) identified 51 D&I models targeting changes at the community level. For the current review, we identified 16 additional D&I models introduced after 2012. We found, between the years of 1969 and 2016, 74 D&I models reflecting five constructs—Communication, Partnership Exchange, Community Capacity-Building, Leadership, and Collaboration—that might influence positive community engagement in scientific research. Our goal was not to find the “best model,” or the model with the greatest potential, but rather to add more specificity to our understanding of what D&I models can offer to the field of community-engaged research. Therefore, this review moves the field a step forward by identifying specific constructs that can help researchers, practitioners, and community partners to select D&I models more likely to include strategies on how to engage the community in D&I studies.

Contextualizing “community” in D&I models

We examined the models grounded in our experiences as community organizers and community-engaged researchers. The process of coding and deriving themes began with more questions than answers: “What does ‘community’ mean in each of the models?” “How does D&I look like in a ‘community’?” In addition to Mendel et al.’s (2008) definition of the term ‘community,’ few papers provided a comparably clear definition. Notably lacking was the mention of key actors (practitioners, stakeholders, consumers) who might be champions and/or facilitators of D&I efforts. Another problematic area was the lack of specificity about the community boundaries—for example, some models appear to consider countrywide efforts as community-focused. Therefore, we recommend that any future D&I model be grounded in a clear definition of ‘community,’ one that specifically applies to that model. We invite D&I model developers to imagine ‘the community’ not only in geographic terms but also in terms of membership identity (e.g., racial/ethnic, sexual orientation, and gender) and relationship-building. We recommend that current D&I models be updated in future publications to be more specific about different areas of community engagement. With more specificity, D&I models will be more helpful to researchers who prioritize community involvement in scientific research.

D&I models can improve the adoption and uptake of EBIs by characterizing the variables (facilitators) that might alleviate implementation barriers. Both barriers and facilitators can be best described by those community stakeholders who face them daily. Regrettably, most D&I models that we analyzed did not fully reflect the voice of community stakeholders; those models that did often focused on practitioners, policymakers, and/or partnering community agencies. Notably missing in many models was the voice of “clients,” individuals who can most benefit from EBIs. Although the D&I models included the “community” as a domain of reference, the absence of how to include community partners weakened the models in their potential to improve access and uptake of EBIs. We recommend that D&I models be more inclusive of community voices. Whenever possible, they should be redesigned to include at least some aspects of each of the five strategies we have identified herein.

Community engagement constructs in D&I models

The models reflecting only one community engagement construct—that is, Communication or Partnership Exchange—suggested an ongoing adaptation of individual-level interventions. Those models reflecting two constructs were also mostly focused on individual-level changes, some specific to a health problem, for example, obesity. Although these models recommended that researchers find a fit between individual-level interventions and multi-level contexts, it is not surprising that they did not explore more deeply any of the five community-level constructs. Noteworthy is that the construct Partnership Exchange was reflected in 92% of the models, followed by Communication in 78% of the models. We engaged in lengthy discussions about the similarities and differences between Partnership Exchange and Communication before deciding not to collapse the two constructs into one. As indicated in the codebook, these constructs appear distinctly in the text of the papers describing D&I models—“communication” appears to be a strategy that includes concrete tools for researchers and community partners to document the transactions inherent in “partnership exchanges.” We recommend that D&I models more specifically describe these two constructs. Future qualitative research may be ideal for further clarifying the meaning of these terms, and quantitative research will be needed to test whether these constructs might differently influence community-level changes.

The frequency at which Community Capacity-Building (62%), Leadership (57%), and Collaboration (53%) are reflected in D&I models containing three to five constructs varies widely across all models. Putting the information gathered from examining all 74 models, we suggest that even though D&I models are seldom explicit about how researchers could engage communities in D&I studies, they generally conjure up constructs with the potential to influence D&I of EBIs positively. Grounded in our definitions of the five constructs, for changes to occur at the community level, researchers will need to partner with community stakeholders by using different methods of communication to engage in a meaningful exchange of concrete and social supports. Collaboration between stakeholders will need to honor the knowledge and skillsets of researchers, practitioners, and community partners so that the leadership may be shared appropriately around D&I studies. From the literature and our reading of the models, capacity is an outcome made possible by the presence of the other four constructs.

Nonetheless, more specificity will be needed to measure “capacity-building.” Is it more capacity to conduct research or better D&I of EBIs? The answers to these questions can be pursued in future research to parse out the unique and cumulative contributions of each of the five constructs we examined.

The progression of community-focused D&I models

The number of D&I models is similar from decade to decade. Similarly, the number of community engagement constructs reflected in older models is not meaningfully different from newer ones. For example, models reflecting all five constructs first appeared in 1969, and they continued to emerge until the present, most prominently in 2003 and 2009. Models developed after 1998 appear to have been greatly influenced by two research paradigms, community-based participatory research (CBPR) (Israel et al., 1998) and diffusion of innovation (Rogers, 2003), both of which were included in Tabak et al.’s (2012) narrative review as D&I models. Even though we included both as models in this current review, we wish to highlight the innovation and reach of these approaches, perhaps the most comprehensively community-focused approaches to date.

According to Google Scholar, combined, all five editions of diffusion of innovation have been cited more than 100,000 times and the original CBPR paper nearly 5,000 times. The five constructs we examined are reflected in both diffusion of innovation and CBPR, suggesting that strong community partnerships are grounded in meaningful community participation in the research methods and design, and dissemination of findings. These constructs align with the CBPR and diffusion of innovation, suggesting that D&I can be improved by promoting collaboration in all phases of the research cycle, by recognizing community as a unit of identity, by encouraging long-term partnerships to facilitate community capacity-building, and by supporting shared leadership that builds on strengths and resources of the community. Applying and integrating these principles in each step of the research cycle, we believe, might improve both the acceptance of findings by the communities involved in the research and the dissemination of findings within the community and the academia.

Although it is not possible to know precisely what might speed up or slow down the publication of new D&I models, it is noteworthy that, with the publication of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research in 2009, cited more than 2,500 times (CFIR Research Team-Center for Clinical Management Research, 2020), the number of new D&I models with strong community content began to slow down. Perhaps the consolidation of myriad models gave rise to an overarching typology that might work in multiple contexts but may also de-emphasize the level of change—system, community, organization, and/or individual—that a given D&I model may intend to achieve. The steady proliferation of D&I models shows that implementation science requires flexibility and innovation regarding research context, design, and methods. The specific proliferation of D&I models with community engagement content appears to have arisen to address time-sensitive environmental changes—policies, regulations, funding, and so on—that influence D&I studies, but which researchers alone are less able to tackle.

Selecting and adapting community-focused D&I models

Only 15 out of 74 D&I models contained all five constructs identified as having the potential to facilitate community engagement and improve D&I efforts. Therefore, it is appropriate to state that D&I models, in general, need improvements if they are to serve as comprehensive approaches that account for community-level variables. By unearthing five specific constructs, our review may enable researchers to identify D&I models that explicitly provide strategies that can be chosen for community engagement. The D&I models containing such strategies are suited for those who wish to conduct community-focused research—they may assist research partners in organizing research priorities, needs, and goals. When selecting or adapting a model, research partners need to consider the specific aims of the study at hand and all the procedures and methods that will be needed to make community-level changes. Before using any of the models, research partners ought to decide how they will define and measure these constructs to meet the needs and priorities of their research. This work is needed to explore the degree to which the constructs we highlighted herein, alone or in combination, may influence both processes and outcomes of D&I research. As the field begins to question the current utility of some EBIs (McKay et al., 2018; Pinto & Witte, 2019), we recommend that researchers pay particular attention to models that might foreshadow the possibility of de-implementation at a later date. This might save both human and concrete resources.

Conclusion

This review has implications for policy/management and decision-making in that it integrates the community-engaged and D&I research literature. Thus, it reveals community engagement constructs reflected in D&I models targeting community-level changes. We analyzed 74 D&I models reflecting five constructs—Communication, Partnership Exchange, Community Capacity-Building, Leadership, and Collaboration—that might influence positive community engagement in scientific research. The critical implication is that managers and policymakers can use the evidence provided in this review to make, for example, funding-related decisions regarding D&I research to affect community-level changes. Moreover, managers in community-based organizations can help researchers, practitioners, and community partners to select D&I models more likely to improve community involvement in D&I studies and subsequently in the services that may be generated by such studies. This is because managers have firsthand knowledge of both barriers and facilitators. Regrettably, most D&I models do not fully reflect the expertise of managers, practitioners, policymakers, or partnering community agencies. Redesigning current D&I models to include this expertise may be advanced by grounding D&I models in the five strategies identified herein. Managers and policymakers can help with the selection and adaptation of D&I models by assisting researchers in connecting specific aims of D&I studies with the methods needed to make community-level changes.

Limitations

Our work here builds on a previous narrative review that used rigorous methods for identifying D&I models. Even though we followed the authors’ original criteria for updating the list of D&I models, it is possible that we may have missed some. It is also possible that we missed papers outside PubMed’s scope. However, we do not believe that the addition of any study or model would substantively change or improve our findings. The lack of specific terminology concerning community engagement in D&I models has made it difficult for us to define, with more depth and specificity, the five constructs that we examined.

As a consequence, we had to lean heavily on our experiences as practitioners and community-engaged researchers to identify and to code the constructs in each of the models. Therefore, it is possible that, even with the definitions set in the codebook, a different set of coders may find slightly different results. However, we do not believe that minor differences would detract from our initial goal to bridge community-engaged and D&I research. We hope our findings will inspire researchers and their partners to use the constructs we have highlighted to pursue a better understanding of the impact of community involvement in D&I efforts.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aarons G. A., Hurlburt M., Horwitz S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. (2016). AMA principles of medical ethics. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/publications-newsletters/ama-principles-medical-ethics

- Anderson M., Cosby J., Swan B., Moore H., Broekhoven M. (1999). The use of research in local health service agencies. Social Science & Medicine, 49(8), 1007–1019. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00179-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atun R. A., de Jongh T., Secci F., Ohiri K., Adeyi O. (2010). Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: A conceptual framework for analysis. Health Policy and Planning, 25(2), 104–111. 10.1093/heapol/czp055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atun R. A., Kyratsis I., Jelic G., Rados-Malicbegovic D., Gurol-Urganci I. (2007). Diffusion of complex health innovations—Implementation of primary health care reforms in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Health Policy and Planning, 22(1), 28–39. 10.1093/heapol/czl031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett M., Miranda J., Kia-Keating M., Saldana L., Landsverk J., Lau A. S. (2019). Developing and evaluating a lay health worker delivered implementation intervention to decrease engagement disparities in behavioural parent training: A mixed methods study protocol. BMJ Open, 9(7), e028988. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-028988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew L. K., Parcel G. S., Kok G. (1998). Intervention mapping: A process for developing theory and evidence-based health education programs. Health Education & Behavior, 25(5), 545–563. 10.1177/109019819802500502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomew L. K., Parcel G. S., Kok G., Gottieb N. H., Fernandez M. E. (2011). Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman A. E., Nelson D. E., Pratt M., Matsudo V., Schoeppe S. (2006). Dissemination of physical activity evidence, programs, policies, and surveillance in the international public health arena. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31(4 Suppl.), 57–65. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins D., Farmer M. S., Edlund C., Sullivan G., Kirchner J. E. (2010). Collaborative research between clinicians and researchers: A multiple case study of implementation. Implementation Science, 5, 76. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S., Zwi A. B. (2005). Pathways to “evidence-informed” policy and practice: A framework for action. PLOS Medicine, 2(7), Article e166. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiano R. M., Daley D. M. (2006). A guide and glossary on postpositivist theory building for population health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(7), 564–570. 10.1136/jech.2004.031534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Research in Implementation Science and Prevention. (2019). Dissemination & implementation models. http://www.dissemination-implementation.org/index.aspx

- CFIR Research Team-Center for Clinical Management Research. (2020). The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). https://cfirguide.org/

- Chambers D. A., Dopson S. (2003). Leading clinical practice change: Evidence-based medicine in the US and UK. In Dopson S., Mark A. L. (Eds.), Leading health care organisations (pp. 173–195). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers D. A., Glasgow R. E., Stange K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8(1), 117. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C. B., Edwards A. E., Jones P. L., Kay L., Cox P. J., Puddy R. W. (2012). A Comparison of the interactive systems framework (ISF) for dissemination and implementation and the CDC division of HIV/AIDS prevention’s research-to-practice model for behavioral interventions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3–4), 518–529. 10.1007/s10464-012-9525-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C. B., Harshbarger C., Sawyer R., Hamdallah M. (2006). The diffusion of effective behavioral interventions project: Development, implementation, and lessons learned. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18(Suppl.), 5–20. 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C. B., Johnson W. D., Lyles C. M. (2007). Linking research and practice: Evidence-based HIV prevention. Focus, 22(7), 1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper L. A., Hill M. N., Powe N. R. (2002). Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 17(6), 477–486. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10633.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham S. D., Card J. J. (2014). Realities of replication: Implementation of evidence-based interventions for HIV prevention in real-world settings. Implementation Science, 9, 5. 10.1186/1748-5908-9-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J. (2014). Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) Wiki. http://cfirwiki.net/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damush T., Bravata D. M., Plue L., Woodward-Hagg H., Williams L. S., Bravata D. M., Hägg H., William L., Woodward H. (2008). Facilitation of best practices (FAB) framework. Stroke QUERI Center Annual Report. https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=ad2c559a-92ca-40ee-a19d-2da598a9567a [Google Scholar]

- Davis D., Davis M. E., Jadad A., Perrier L., Rath D., Ryan D., Sibbald G., Straus S., Rappolt S., Wowk M., Zwarenstein M. (2003). The case for knowledge translation: Shortening the journey from evidence to effect. British Medical Journal, 327(7405), 33–35. 10.1136/bmj.327.7405.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S. M., Peterson J. C., Helfrich C. D., Cunningham-Sabo L. (2007). Introduction and conceptual model for utilization of prevention research. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33(1 Suppl.), S1–S5. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing J. W. (1996). Social marketing and diffusion-based strategies for communicating with unique populations: HIV prevention in San Francisco. Journal of Health Communication, 1(4), 343–364. 10.1080/108107396127997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing J. W., Maibach E. W., Buller D. B. (2006). A convergent diffusion and social marketing approach for disseminating proven approaches to physical activity promotion. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31(4 Suppl.), 11–23. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio P. J., Powell W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. 10.2307/2095101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins M., Ciliska D., Cockerill R., Barnsley J., DiCenso A. (2002). A framework for the dissemination and utilization of research for health-care policy and practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing Presents the Archives of Online Journal of Knowledge Synthesis for Nursing, E, 9(1), 149–160. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2002.00149.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins M., DeCorby K., Robeson P., Tirilis D. (2010). Public health model. In Rycroft-Malone J., Bucknall T. (Eds.), Models and frameworks for implementing evidence-based practice: Linking evidence to action (Vol. 2, p. 268). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson E. A., Brownson R. C., Weiss S. M. (2012). Policy dissemination research. In Brownson R. C., Colditz G. A., Proctor E. K. (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice (pp. 437–458). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dreisinger M. L., Boland E. M., Filler C. D., Baker E. A., Hessel A. S., Brownson R. C. (2012). Contextual factors influencing readiness for dissemination of obesity prevention programs and policies. Health Education Research, 27(2), 292–306. 10.1093/her/cyr063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin R. (1978). Theory building. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles M. P., Mittman B. S. (2006). Welcome to implementation science. Implementation Science, 1(1), 1. 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen M. E., Lavis J. N., Ouimet M., Grimshaw J., Bédard P.-O. (2011). Determining research knowledge infrastructure for healthcare systems: A qualitative study. Implementation Science, 6(1), 60. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott S. J., O’Loughlin J., Robinson K., Eyles J., Cameron R., Harvey D., Raine K., Gelskey D. (2003). Conceptualizing dissemination research and activity: The case of the Canadian Heart Health Initiative. Health Education & Behavior, 30(3), 267–282. 10.1177/1090198103030003003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G., Taubert M., Kowalczuk J. (2007). Sticky knowledge: A possible model for investigating implementation in healthcare contexts. Implementation Science, 2, 44. 10.1186/1748-5908-2-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas M., Anthony W. A. (2007). Bridging science to service: Using Rehabilitation Research and Training Center program to ensure that research-based knowledge makes a difference. The Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 44(6), 879. 10.1682/JRRD.2006.08.0101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas M., Jette A. M., Tennstedt S., Haley S. M., Quinn V. (2003). Knowledge dissemination and utilization in gerontology: An organizing framework. The Gerontologist, 43(Suppl. 1), 47–56. 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin P. (2001). Understanding American communities. In Rothman J., Tropman J. E., Erlich J. L. (Eds.), Strategies of community intervention (6th ed., pp. 118–132). Peacock. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen D. L., Naoom S. F., Blase K. A., Friedman R. M., Wallace F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network (FMHI Publication #231). https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/resources/implementation-research-synthesis-literature [Google Scholar]

- Flaspohler P., Lesesne C. A., Puddy R. W., Smith E., Wandersman A. (2012). Advances in bridging research and practice: Introduction to the second special issue on the interactive system framework for dissemination and implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3–4), 271–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming E. S., Perkins J., Easa D., Conde J. G., Baker R. S., Southerland W. M., Dottin R., Benabe J. E., Ofili E. O., Bond V. C., McClure S. A., Sayre M. H., Beanan M. J., Norris K. C. (2008). The role of translational research in addressing health disparities: A conceptual framework. Ethnicity & Disease, 18(2 Suppl.), 155–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort-Nachmias C., Nachmias D. (1996). Research methods in the social sciences. Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Funk S. G., Tornquist E. M., Champagne M. T. (1989). A model for improving the dissemination of nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 11(3), 361–367. 10.1177/019394598901100311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S., Duran N., Norris K. (2014). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), e16–e31. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K., Bishop D. B. (2010). The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health, 31(1), 399–418. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R. E., Green L. W., Taylor M. V., Stange K. C. (2012). An evidence integration triangle for aligning science with policy and practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(6), 646–654. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow R. E., Vogt T. M., Boles S. M. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1322–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C., Schoenwald S. K. (2005). The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children’s mental health treatments. Mental Health Services Research, 7(4), 243–259. 10.1007/s11020-005-7456-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C., Schoenwald S. K., Hemmelgarn A., Green P., Dukes D., Armstrong K. S., Chapman J. E. (2010). Randomized trial of MST and ARC in a two-level EBT implementation strategy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(4), 537–550. 10.1037/a0019160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L. W., Kreuter M. W. (2005). Health program planning: An educational and ecological approach (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Green L. W., Orleans C. T., Ottoson J. M., Cameron R., Pierce J. P., Bettinghaus E. P. (2006). Inferring strategies for disseminating physical activity policies, programs, and practices from the successes of tobacco control. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31(4 Suppl.), 66–81. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L. W., Ottoson J. M., García C., Hiatt R. A. (2009). Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 30(1), 151–174. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T., Robert G., Macfarlane F., Bate P., Kyriakidou O. (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 581–629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson R. F., Saunders B. E., Ralston E., Moreland A. D., Peer S. O., Fitzgerald M. M. (2019). Statewide implementation of child trauma-focused practices using the community-based learning collaborative model. Psychological Services, 16(1), 170–181. 10.1037/ser0000319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson R. F., Schoenwald S., Saunders B. E., Chapman J., Palinkas L. A., Moreland A. D., Dopp A. (2016). Testing the Community-Based Learning Collaborative (CBLC) implementation model: A study protocol. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10, 52. 10.1186/s13033-016-0084-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. R., Cheadle A., Hannon P. A., Lichiello P., Forehand M., Mahoney E., Snyder S., Yarrow J. (2011). A framework for disseminating evidence-based health promotion practices. Preventing Chronic Disease, 9, E22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3277406/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelock R. G. (1969). Planning for innovation through dissemination and utilization of knowledge. Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century (No. 0309072808). National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ion G., Stîngu M., Marin E. (2019). How can researchers facilitate the utilisation of research by policy-makers and practitioners in education? Research Papers in Education, 34(4), 483–498. 10.1080/02671522.2018.1452965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B. A., Eng E., Schulz A. J., Parker E. A. (2005). Introduction to methods in community-based participatory research for health. In Israel B. A., Eng E., Schulz A. J., Parker E. A. (Eds.), Methods in community-based participatory research for health (pp. 3–26). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Israel B. A., Schulz A. J., Parker E. A., Becker A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N., Butterill D., Goering P. (2003). Development of a framework for knowledge translation: Understanding user context. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 8(2), 94–99. 10.1258/135581903321466067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James A. S., Richardson V., Wang J. S., Proctor E. K., Colditz G. A. (2013). Systems intervention to promote colon cancer screening in safety net settings: Protocol for a community-based participatory randomized controlled trial. Implementation Science, 8(1), 58. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L., Wells K. (2007). Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297(4), 407–410. 10.1001/jama.297.4.407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne A. M., Neumann M. S., Pincus H. A., Bauer M. S., Stall R. (2007). Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: Application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implementation Science, 2(1), 42. 10.1186/1748-5908-2-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne A. M., Switzer G., Hyman K., Crowley-Matoka M., Fine M. J. (2006). Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: A conceptual framework. American Journal of Public Health, 96(12), 2113–2121. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon J. W. (2010). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (2nd ed.). Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Kitson A. L., Harvey G., McCormack B. (1998). Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. Quality in Health Care, 7(3), 149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson A. L., Rycroft-Malone J., Harvey G., McCormack B., Seers K., Titchen A. (2008). Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: Theoretical and practical challenges. Implementation Science, 3, 1. 10.1186/1748-5908-3-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft J. M., Mezoff J. S., Sogolow E. D., Neumann M. S., Thomas P. A. (2000). A technology transfer model for effective HIV/AIDS interventions: Science and practice. AIDS Education and Prevention; New York, 12, 7–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter M. W., Casey C. M., Bernhardt J. M. (2012). Enhancing dissemination through marketing and distribution systems: A vision for public health. In Brownson R. C., Colditz G. A., Proctor E. K. (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice (pp. 213–222). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langley G. J., Moen R. D., Nolan K. M., Nolan T. W., Norman C. L., Provost L. P. (2009). The Improvement guide: A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Langley J., Wolstenholme D., Cooke J. (2018). “Collective making” as knowledge mobilisation: The contribution of participatory design in the co-creation of knowledge in healthcare. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 585. 10.1186/s12913-018-3397-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J. N. (2006). Assessing country-level efforts to link research to action. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 84(8), 620–628. 10.2471/BLT.06.030312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis J. N., Robertson D., Woodside J. M., McLEOD C. B., Abelson J. (2003). How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? The Milbank Quarterly, 81(2), 221–248. 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester J. P. (1993). The utilization of policy analysis by state agency officials. Knowledge, 14(3), 267–290. 10.1177/107554709301400301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leykum L. K., Pugh J. A., Lanham H. J., Harmon J., McDaniel R. R. (2009). Implementation research design: Integrating participatory action research into randomized controlled trials. Implementation Science, 4, 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J., Graham I. D. (1998). Toward a comprehensive interdisciplinary model of health care research use. Science Communication, 20(2), 227–246. 10.1177/1075547098020002004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J., Graham I. D. (2010). The Ottawa model of research use. In Rycroft-Malone J., Bucknall T. (Eds.), Models and frameworks for implementing evidence-based practice: linking evidence to action. pp. 38–45. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Maar M., Yeates K., Barron M., Hua D., Liu P., Lum-Kwong M. M., Perkins N., Sleeth J., Tobe J., Wabano M. J., Williamson P., Tobe S. W. (2015). I-RREACH: An engagement and assessment tool for improving implementation readiness of researchers, organizations and communities in complex interventions. Implementation Science, 10(1), 64. 10.1186/s13012-015-0257-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G. W., Herie M. A., Turner B. J., Cunningham J. A. (1998). A social marketing model for disseminating research-based treatments to addictions treatment providers. Addiction, 93(11), 1703–1715. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931117038.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson G. O., Pacione C., Shultz R. K., Klügl M. (2015). Leveraging human-centered design in chronic disease prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48(4), 472–479. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May C., Finch T. (2009). Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535–554. 10.1177/0038038509103208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- May C., Macfarlane A., Finch T., Rapley T., Treweek S., Ballini L., Mair F., Murray E. (n.d.). Normalization process theory on-line users’ manual and toolkit. http://www.normalizationprocess.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McKay V. R., Morshed A. B., Brownson R. C., Proctor E. K., Prusaczyk B. (2018). Letting go: Conceptualizing intervention de-implementation in public health and social service settings. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(1–2), 189–202. 10.1002/ajcp.12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendel P., Meredith L. S., Schoenbaum M., Sherbourne C. D., Wells K. B. (2008). Interventions in organizational and community context: A framework for building evidence on dissemination and implementation in health services research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 35(1), 21–37. 10.1007/s10488-007-0144-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S., Johnston M., Abraham C., Lawton R., Parker D., Walker A. (2005). Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: A consensus approach. BMJ Quality & Safety, 14(1), 26–33. 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S., van Stralen M. M., West R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6(1), 42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), Article e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E., Treweek S., Pope C., MacFarlane A., Ballini L., Dowrick C., Finch T., Kennedy A., Mair F., O’Donnell C., Ong B. N., Rapley T., Rogers A., May C. (2010). Normalisation process theory: A framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Medicine, 8(1), 63. 10.1186/1741-7015-8-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers. (2017). Code of ethics of the national association of social workers. https://socialwork.utexas.edu/dl/files/academic-programs/other/nasw-code-of-ethics.pdf

- National Implementation Research Network. (2019). Active implementation hub. http://implementation.fpg.unc.edu/

- National Information Center on Health Services Research and Health Care Technology. (2016). Dissemination and implementation science. https://hsric.nlm.nih.gov/hsric_public/topic/implementation_science/

- Neta G., Glasgow R. E., Carpenter C. R., Grimshaw J. M., Rabin B. A., Fernandez M. E., Brownson R. C. (2014). A framework for enhancing the value of research for dissemination and implementation. American Journal of Public Health, 105(1), 49–57. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M. S., Sogolow E. D. (2000). Replicating effective programs: HIV/AIDS prevention technology transfer. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 12(5 Suppl.), 35–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10(1), 53. 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan K., Schall M. W., Erb F., Nolan T. (2005). Using a framework for spread: The case of patient access in the Veterans health administration. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 31(6), 339–347. 10.1016/S1553-7250(05)31045-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie D., Craig P., Griffin S., Macintyre S., Wareham N. J. (2009). A translational framework for public health research. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 116. 10.1186/1471-2458-9-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh A. (2018, September). Design thinking and community-based participatory research for Implementation Science. National Cancer Institute. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/IS/blog/2018/09-design-thinking-and-community-based-participatory-research-for-implementation-science.html [Google Scholar]

- Orlandi M. A. (1996). Health promotion technology transfer: Organizational perspectives. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 87(Suppl. 2), S28–S33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen N., Glanz K., Sallis J. F., Kelder S. H. (2006). Evidence-based approaches to dissemination and diffusion of physical activity interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 31(4), 35–44. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas L. A., Soydan H. (2012). Translation and implementation of evidence-based practice. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pathman D. E., Konrad T. R., Freed G. L., Freeman V. A., Koch G. G. (1996). The awareness-to-adherence model of the steps to clinical guideline compliance: The case of pediatric vaccine recommendations. Medical Care, 34(9), 873–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J. C., Rogers E. M., Cunningham-Sabo L., Davis S. M. (2007). A framework for research utilization applied to seven case studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 33(1 Suppl.), S21–S34. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew A., Ferlie E., McKee L. (1992). Shaping strategic change: Making change in large organizations: The case of the National Health Service. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto R. M., Spector A. Y., Valera P. A. (2011). Exploring group dynamics for integrating scientific and experiential knowledge in community advisory boards for HIV research. AIDS Care, 23(8), 1006–1013. 10.1080/09540121.2010.542126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pinto R. M., Spector A. Y., Rahman R., Gastolomendo J. D. (2015). Research advisory board members’ contributions and expectations in the USA. Health Promotion International, 30(2), 328–338. 10.1093/heapro/dat042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pinto R. M., Witte S. S. (2019). No Easy Answers: Avoiding Potential Pitfalls of De-implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63(1–2), 239–242. 10.1002/ajcp.12298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pinto R. M., Yu G., Spector A. Y., Gorroochurn P., McCarty D. (2010). Substance abuse treatment providers’ involvement in research is associated with willingness to use findings in practice. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 39(2), 188–194. 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pinto R. M. (2013). What makes or breaks provider–researcher collaborations in HIV research? A mixed method analysis of providers’ willingness to partner. Health Education & Behavior : The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 40(2), 223–230. 10.1177/1090198112447616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pinto R. M., McKay M. M., Escobar C. (2008). “You’ve gotta know the community”: Minority women make recommendations about community-focused health research. Women & Health, 47(1), 83–104. 10.1300/J013v47n01_05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Powell B. J., Beidas R. S., Rubin R. M., Stewart R. E., Wolk C. B., Matlin S. L., Weaver S., Hurford M. O., Evans A. C., Hadley T. R., Mandell D. S. (2016). Applying the policy ecology framework to Philadelphia’s behavioral health transformation efforts. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 43(6), 909–926. 10.1007/s10488-016-0733-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E. K., Landsverk J., Aarons G., Chambers D., Glisson C., Mittman B. (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 36(1), 24–34. 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pronovost P. J., Berenholtz S. M., Needham D. M. (2008). Translating evidence into practice: A model for large scale knowledge translation. British Medical Journal, 337, a1714. 10.1136/bmj.a1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Leadership Society. (2002). Principles of the ethical practice of public health. https://www.apha.org/-/media/files/pdf/membergroups/ethics/ethics_brochure.ashx

- Rabin B. A., Brownson R. C. (2012). Developing the terminology for dissemination and implementation research. In Brownson R. C., Colditz G. A., Proctor E. K. (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice (pp. 23–51). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon R., Lavis J., Gibson J. (2006). From research to practice: A knowledge transfer planning guide. Institute for Work & Health. https://www.iwh.on.ca/sites/iwh/files/iwh/tools/iwh_kte_planning_guide_2006b.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Redmond L. C., Jock B., Gadhoke P., Chiu D. T., Christiansen K., Pardilla M., Swartz J., Platero H., Caulfield L. E., Gittelsohn J. (2019). OPREVENT (Obesity Prevention and Evaluation of InterVention Effectiveness in NaTive North Americans): Design of a multilevel, multicomponent obesity intervention for native American Adults and Households. Current Developments in Nutrition, 3(Suppl. 2), 81–93. 10.1093/cdn/nzz009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]