Abstract

The cofactor nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) plays a key role in a wide range of physiological processes and maintaining or enhancing NAD+ levels is an established approach to enhancing healthy aging. Recently, several classes of nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (NAMPT) activators have been shown to increase NAD+ levels in vitro and in vivo and to demonstrate beneficial effects in animal models. The best validated of these compounds are structurally related to known urea-type NAMPT inhibitors, however the basis for the switch from inhibitory activity to activation is not well understood. Here we report an evaluation of the structure activity relationships of NAMPT activators by designing, synthesising and testing compounds from other NAMPT ligand chemotypes and mimetics of putative phosphoribosylated adducts of known activators. The results of these studies led us to hypothesise that these activators act via a through-water interaction in the NAMPT active site, resulting in the design of the first known urea-class NAMPT activator that does not utilise a pyridine-like warhead, which shows similar or greater activity as a NAMPT activator in biochemical and cellular assays relative to known analogues.

Key words: Nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase activator, Healthy aging, Drug discovery, Bioisosteres, Medicinal chemistry

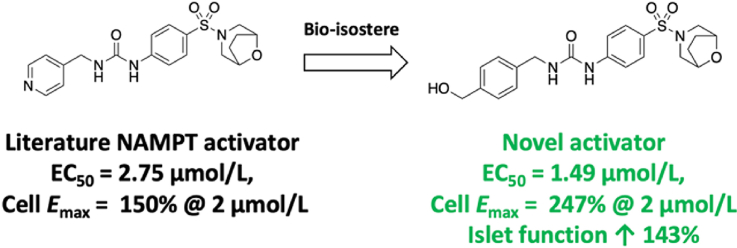

Graphical abstract

Chemistry-led investigation of the structure activity relationships of urea-class NAMPT activators resulting in the discovery of non-pyridyl class compounds with enhanced cellular and phenotypic activity.

1. Introduction

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and its reduced and/or phosphorylated forms are essential cofactors for a range of both redox and non-redox based processes in healthy cells1. Declining NAD+ levels are associated with aging and have been implicated in age-associated disease including neurodegeneration and metabolic disease, with in vivo studies demonstrating the potential role of increasing NAD+ in improving healthy aging in animal models2,3.

As a result, the enhancement of NAD+ levels by either nutritional or pharmacological approaches is a potential therapeutic option for treatment of aging-associated conditions2. While cells have multiple routes by which NAD+ can be obtained, the salvage pathway, in which nicotinamide and phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate are condensed to form the NAD+ precursor nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) by the action of nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (NAMPT), is the most studied pathway in the context of cellular control of NAD+ levels4,5.

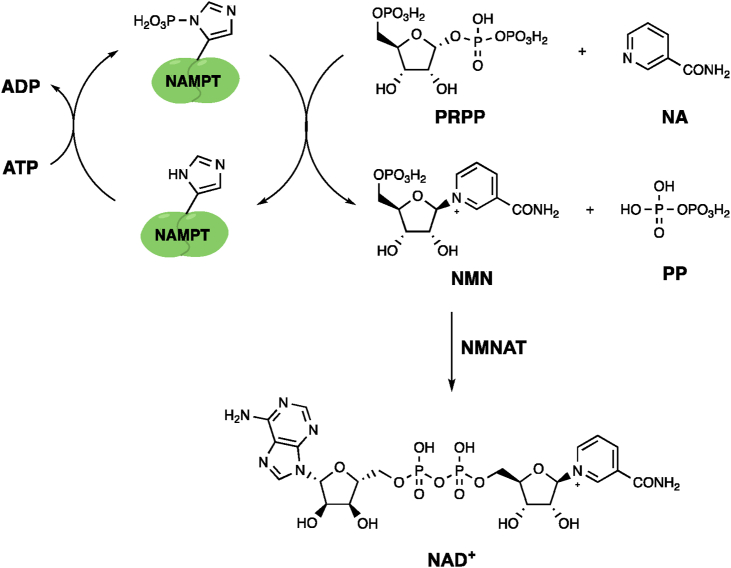

NAMPT is a highly conserved homo-dimeric protein containing two identical active sites that each comprise residues from both chains of the dimer4. It catalyses the reaction between phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) and nicotinamide (NA) to form NMN and pyrophosphate (PP), with NMN then further converted to NAD+ by the action of Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenosyl transferase (NMNAT), which catalyses the condensation of NMN and adenosine triphosphate (ATP, Fig. 1)4. The catalytic activity of NAMPT is dependent on ATP, which binds in the catalytic site resulting in phosphorylation of His2474. This phospho-histidine is readily hydrolysed under physiological conditions and can also facilitate the transfer of phosphate to ATP to form ATtP6. Due to the high activity of NMNAT and high levels of NMNAT and ATP in cells, NAMPT-mediated NMN synthesis is considered the rate-limiting stage of the NAD+ salvage pathway7.

Figure 1.

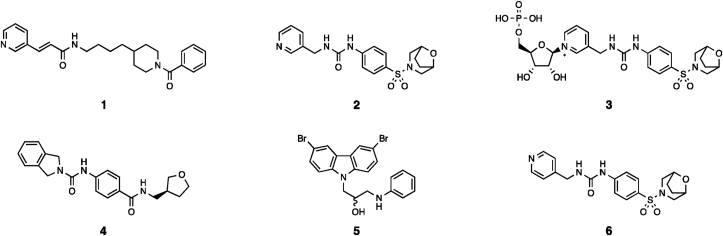

The understanding of cellular function of this pathway was driven in part by the discovery of highly cytotoxic NAMPT inhibitors, the prototypical example of which is FK866 1 (Fig. 2)9. Subsequent research has identified a number of NAMPT inhibitor chemotypes, which can be classified into two broad sets; pyridine-like inhibitors, such as FK866 and compound 2 (Fig. 2), which react with PRPP in the active site to form high affinity phosphoribosylated adducts (exemplified by 3, Fig. 2), and reversible non-substrate inhibitors such as compound 4 (Fig. 2)11, 12, 13. These inhibitors are able to induce near complete depletion of NAD+ in cells within 24 h of treatment, leading to metabolic dysfunction including loss of ATP after 12–24 h, and typically induce cell death after 72–96 h9. As a result, NAMPT inhibitors have been extensively studied, especially in the oncology setting, however due to the relative non-specificity of these molecules across different cell types such compounds have only been advanced to clinical trials in oncology indications and to date none have shown a useable therapeutic window13.

Figure 2.

Structures of previously reported NAMPT modulators. Compounds 1, 2, 3 and 4 are NAMPT inhibitors, compounds 5 and 6 are reported to be NAMPT activators, despite 6 being a close analogue of inhibitor 2.

As NAMPT function is the rate limiting step in the NAD+ salvage pathway, it is possible that compounds that can enhance cellular NAMPT activity could be used to increase cellular NAD+ levels and thus treat conditions associated with reduced NAD+ function. The first identified example of such a molecule is P7C3 5 (Fig. 2), which can increase cellular NAD+ levels and may be a direct NAMPT ligand, however we and others have failed to detect a direct interaction between P7C3 and NAMPT by biophysical methods14, 15, 16. A more recent study identified SBI-797812 6 (Fig. 2) as a direct NAMPT ligand that is capable of activating the enzyme in vitro and results in increased NAD+ levels in cells and mouse in vivo studies15. The mechanism of these compounds appears to be linked to altered reactivity of phospho-His24715, however it is not clear if this is the result of binding to one active site resulting in activation of the second free site, or through competitive reversible binding at the functional active site which results in net activation of the protein.

The structure and published structure–activity relationships around 6 are somewhat surprising given the compounds similarity to potent NAMPT inhibitors such as 2 (Fig. 2). There appears to be a specific requirement for a pyridine-like nitrogen at the 4-position of 6, with the phenyl analogue being inactive and the 3-pyridyl being a known NAMPT inhibitor. This pyridine-like nitrogen is also present in all urea-class NAMPT activators reported in later publications, wherein the 3-pyridine has been modified to heterocyclic systems including pyrazoles and isoxazoles, alongside modifications in other regions that can enhance both activity and selectivity of these compounds17, 18, 19. This finding has been followed by the discovery of further NAMPT-activator chemotypes that do not bind in the NA site, however the pyridine/azole urea molecules remain the most fully biologically characterised molecules20.

2. Results and discussion

As a result of the limitations in our understanding of the activity of 6 and related NA-site binding activators, we sought to investigate the structure–activity relationships around this compound in more detail by preparing analogues based on the following design criteria:

-

1)

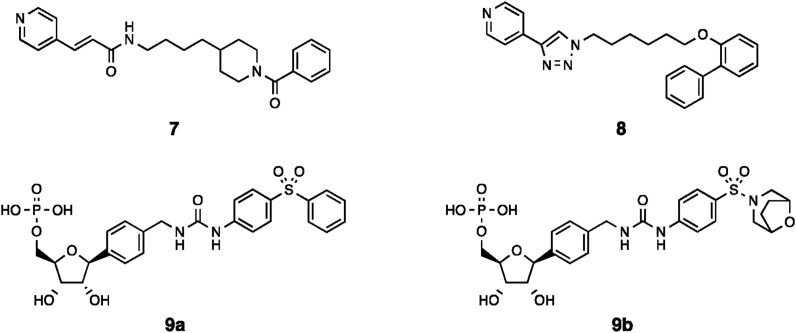

To date, the published examples of NAMPT-activators from the NA-site binding class are based on the urea-like scaffold of 617, 18, 19. Crystal structures of closely related inhibitors such as 2 demonstrate a similar binding mode to FK866 and triazole-based NAMPT inhibitors, we therefore designed and synthesised compounds 7 and 8 (Fig. 3) to investigate the activity of compounds from other scaffolds.

-

2)

Given the essential nature of the 4-pyridyl like functionality in 6 and analogues, we hypothesised these compounds may form phosphoribosylated adducts, in a similar manner to the conversion of inhibitor 2 to adduct 3. While the detection of such a species has not been disclosed and we observed no evidence of its formation by LC‒MS in vitro, we considered it possible that very low levels of a high affinity phosphoribosylated species could be responsible for the observed activity, as it is known that the conformation of such phosphoribosylated analogues affects their affinity and rate of formation10. To avoid any concerns around stability of the phosphoribosylated analogue, we designed and synthesised the stable C-nucleoside derivatives 9a and 9b (Fig. 3) as stable analogues of the product derived from phosphoribosylation of 6.

Figure 3.

Structures of tool compounds designed to investigate mechanism of NAMPT activators.

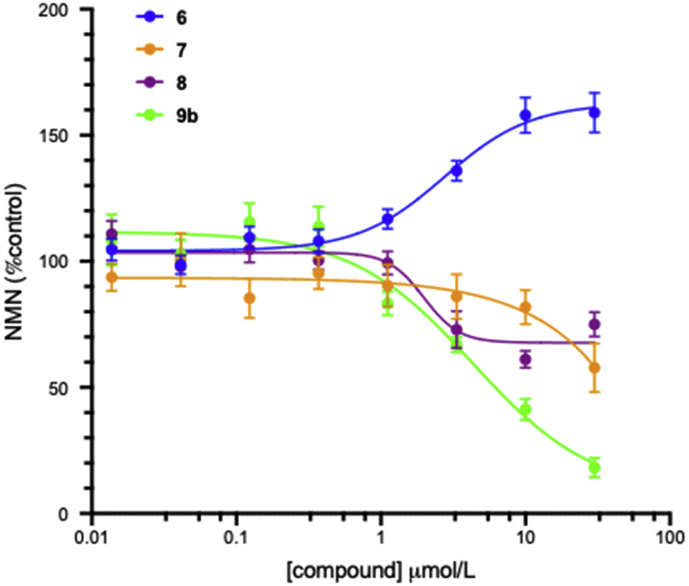

The activity of known activator 6 and new analogues 7, 8 and 9b (Fig. 3) were initially assessed in a biochemical assay similar to that reported previously21. This assay format allows for detection of both activators and inhibitors of NAMPT, however in our hands the assay-to-assay variability is higher for activators than inhibitors. In our experiments, 6 increases NAMPT activity, resulting in a 59% increase in NMN production at 30 μmol/L, with an EC50 of 2.75 μmol/L, which represents lower activity than the reported EC50 of 0.37 μmol/L with maximal 110% activation.

Compounds 7 and 8, based on alternative NAMPT inhibitor scaffolds, both act as weak inhibitors in this assay, suggesting that the urea-derived 6 and analogues have a unique mechanism or binding mode which are distinct from these structural classes. The weak activity of these compounds relative to the reported low-nmol/L IC50 of the related 3-pyridiyl analogues is consistent with them either not acting as substrates or forming low affinity phosphoribosyl adducts. Consistent with this observation, the phosphoribosylated analogue 9b also showed no evidence of activation, but rather acts as a weak inhibitor of NAMPT, with an IC50 of 4.32 μmol/L (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Effects of compounds 6, 7, 8 and 9b on NMN production in the biochemical NAMPT assay. All data is from a minimum of three independent replicates conducted in triplicate and is shown as mean ± SEM.

While this data alone is not conclusive, the inhibitory effect of the phosphoribosyl mimetic 9b suggests that NAMPT activation by 6 and analogues is not mediated by phosphoribosylated adducts generated by the action of NAMPT.

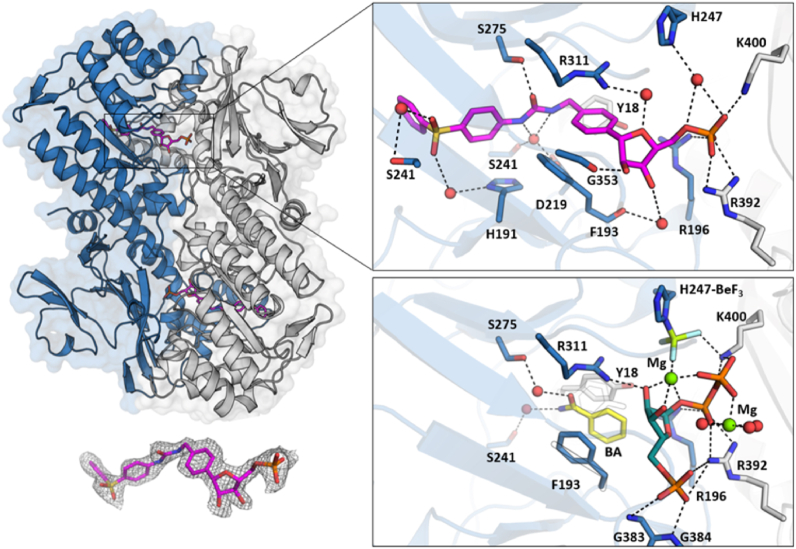

As part of our studies on NAMPT activators compound 9a, a close analogue of 9b which differs only in a solvent-adjacent region away from the active site, had previously been co-crystallised with NAMPT and as expected interacts in the active site, however there are some key differences relative to the majority of previously reported NAMPT-ligand structures. Firstly, the phosphoribose is displaced from the region occupied by the natural substrate/products or known phosphoribosylated inhibitor structures, which is likely due to the change in orientation enforced by the switch from 3- to 4-substitution (Fig. 5). The second observed change is a shift of the orientation of the nicotinamide-like phenyl ring such that it no longer makes pi-interactions with Phe193 and Tyr18 (as are observed with NMN and the majority of NAMPT-inhibitor structures), but rather sits in a pocket between Phe193 and Arg 311, forming an apparent pi-stacking interaction between the phenyl ring in 9a and the cationic guanidine of Arg311 (Fig. 5). This binding mode is closer to that previously observed in the complex with an ADP analogue, while both Phe193/Tyr18 and Phe193/Arg311 binding modes are observed in the structure of the phosphoribosylated urea-based inhibitor SAR154782 (PDB: 5LX5)22,23.

Figure 5.

Compound 9a bound to dimeric NAMPT (PDB: 7Q8T). One chain is colored in blue the other in grey. The upper insert shows detailed interaction of 9a (pink) with surrounding residues as dashed black lines. Bridging water molecules are shown as red spheres. The bottom right insert shows the PRPP (teal) and nicotinamide mimetic (benzamide, BA, yellow) bound structure of BeF3-His247 (PDB: 3DKL). Magnesium ions are coloured in green. The orientation is the same as in the upper panel. The conformation change of F193 and Y18 is indicated as a black outline. Bottom right shows the observed electron density of the ligand contoured at 1 σ.

Effectively all known NAMPT inhibitors form either direct or water-mediated hydrogen bonding interactions in the region of Asp219, Ser241 and Arg311, for example these interactions are achieved by the urea of 2 and the secondary amide of FK866. These interactions are maintained by 9a with the change in binding mode to Phe193/Arg311 resulting from flexibility in the aryl–CH2–urea region, which is a unique feature of this ligand class relative to other NAMPT inhibitor chemotypes.

As compounds 7 and 8 show inhibitory activity against NAMPT, both the Phe193/Arg311 binding mode and NAMPT activation appear to be a unique feature of the CH2-urea class ligands. We therefore hypothesised that the known NAMPT activators may bind specifically through this binding mode, however this binding mode alone cannot explain the switch in activity as both 9b and SAR154782 are inhibitors of the protein.

To further understand the potential link between the Phe193/Arg311 binding mode and NAMPT activation, we examined the structure of 9a overlaid with the structures of NAMPT bound to its substrates, including the phospho-histidine mimetic BeF3-His247 structure. This analysis revealed that the ribose ring oxygen in 9a occupies a position in the active site which is very close to the ribose hydroxyls in the product-bound BeF3-His247 structure.

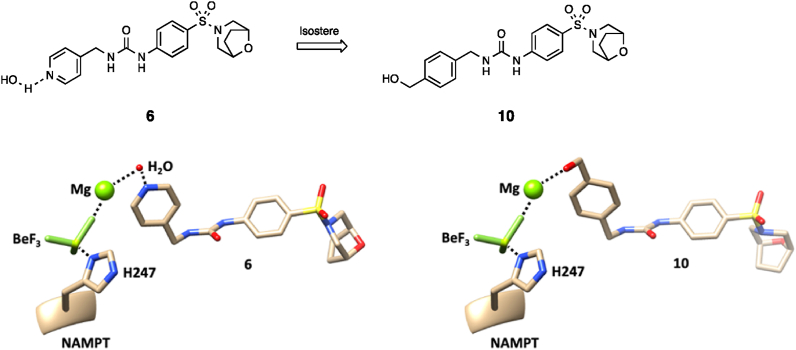

Given the lack of obvious rationale for the requirement for the 4-pyridyl (or 3-azole) ring in 6 and analogues, we docked 6 into NAMPT in the conformation seen with 9a. This docking resulted in a close overlay with the benzyl urea region of 9a, with the pyridine of 6 orientated towards His247 but not in a region that would allow for any direct interactions with the protein (Fig. 6). We considered the possibility that this nitrogen forms an indirect (i.e., through-water) interaction with p-His247 or a metal ion (likely magnesium) thereby stabilising the phospho-histidine and/or holding the enzyme in a conformation that favours the formation of NMN at the second active site. Overlay with the His247-BeF3-Mg bound NAMPT structure from PDB:3DKL demonstrated this interaction is feasible (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Design hypothesis of benzyl alcohol 10 as an isostere of a putative pyridine–water interaction made by 6. Docked pose of compounds 6 and 10 bound to PDB:7Q8T, aligned with the His 247-BeF3-Mg residues from PDB: 3DKL, demonstrating the potential for interactions with the p-His247 region in this binding mode. All other NAMPT residues from PDB:7Q8T and PDB: 3DKL are removed for clarity.

Based on the findings that: 1) Both NAMPT activation and the Phe193/Arg311 binding mode are unique features of the benzyl urea NAMPT ligand chemotype, 2) the 4-pyridyl (or 3-azole) functionality that is essential for NAMPT activation in this chemotype does not appear to be linked to formation of phosphoribosylated adducts and 3) the Phe193/Arg311 binding mode places the essential 4-pyridyl (or 3-azole) in a region that would allow formation of water-mediated interactions with the p-His247, we designed compound 10, with the aim that the benzylic alcohol can directly replicate this putative interaction (Fig. 6). The use of benzyl alcohols as bioisosteres for a pyridine–water interaction (or the reverse) is precedented, for example in the design of PI3K inhibitors, and has the advantage of reducing the likelihood of CYP450 interactions which are commonly observed with unsubstituted aza-hetrocycles24.

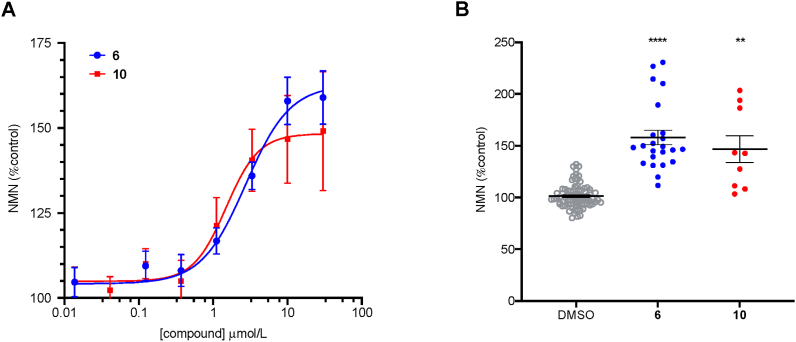

Compound 10 was therefore prepared and tested in the NAMPT activity assay used previously. The results from these experiments demonstrate that benzylic alcohol 10 retains the ability to enhance NMN production by NAMPT, with an observed EC50 of 1.49 μmol/L under these conditions (Fig. 7). This result is consistent with the hypothesis that 6 and related molecules make an interaction with a water molecule in the active site of NAMPT (potentially interacting with coordinated metal in the active site) and, as this compound cannot be a substrate, further supports the hypothesis that the activity of 6 is not dependant on phosphoribosylation.

Figure 7.

Effects of compounds 6 and 10 on NMN production in the biochemical NAMPT assay; (A) Dose response data. All data is from a minimum of three independent replicates conducted in triplicate and is shown as mean ± SEM (B) Comparison of effects of 6 (n = 21) and 10 (n = 9) at 10 μmol/L vs DMSO control (n = 81). Significant differences (from DMSO vehicle) are denoted by ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

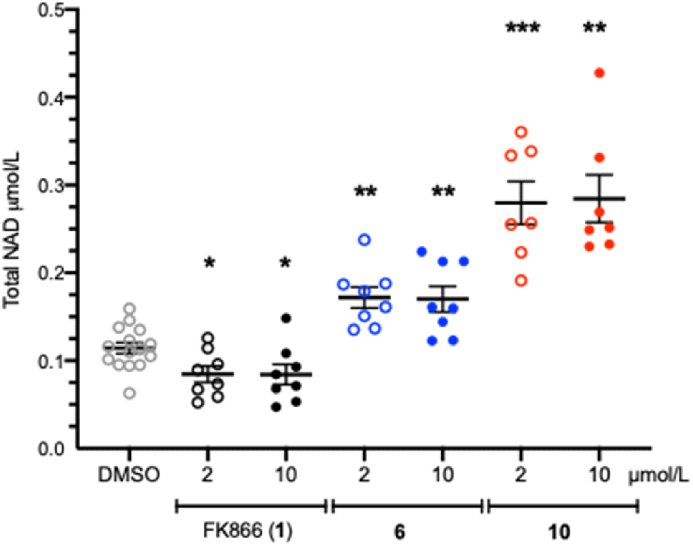

Following the characterization of 10 as a novel NAMPT activator in biochemical experiments, we sought to evaluate its effects on NAD + levels in cells following similar methods to those utilized in the characterization of 615. A 4-h treatment of A549 cells with compounds 6 or 10 results in a significant increase in total NAD+/NADH levels relative to media control (DMSO). At the tested concentrations of 2 and 10 μmol/L compound 10 demonstrated a higher degree of activity relative to the known activator 6, increasing NAD+/NADH levels by an average of 247% vs 150% (difference reaches significance at P < 0.01 at both concentrations, Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Effects of 4-h treatment of FK866 (1) and compounds 6 (blue) and 10 (red) on NAD+ levels in A549 cells. Significant differences (from DMSO vehicle) are denoted by ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

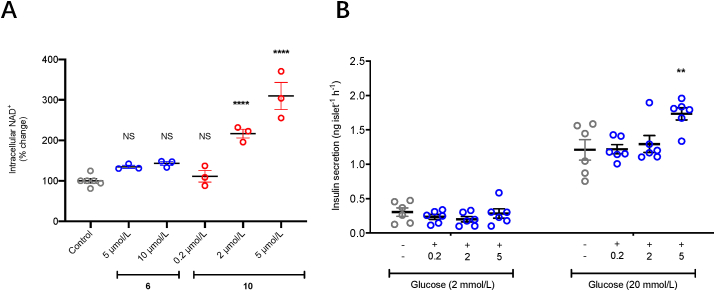

Following the report that NAMPT activators enhance insulin secretion in vivo and based on our previous interest in the role of NAMPT in this context, we sought to investigate the effects of compounds 6 and 10 on ex vivo mouse islets19,25. In line with our results in A549 cells compound 10 caused a dose dependant increase in total NAD+ content, reaching 310% control at 5 μmol/L (Fig. 9A), which resulted in increased insulin secretion response at higher concentrations following stimulation with 20 mmol/L glucose (Fig. 9B). Also similar to the data in A549 cells, compound 6 showed more limited effects on islets, with increase in NAD+ levels to 142% of control and no significant effect on insulin secretion (data not shown).

Figure 9.

(A) Effects of compounds 6 and 10 on intracellular NAD+ change in mouse CD1 islets. Data is from three independent replicates. (B) Effects of compounds 6 on insulin secretion from mouse CD1 islets. Data is from three independent replicates conducted in duplicate. All data is shown as individual values with mean ± SEM (n = 6). Significant differences (from control) are denoted ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test.

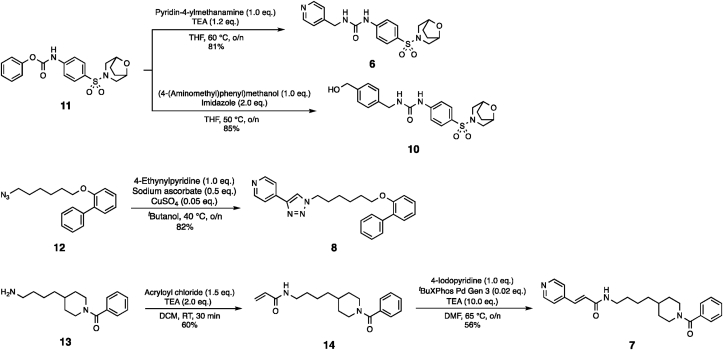

Chemistry. Compounds 6, 8 and 10 were synthesised from known intermediates 11 and 12 respectively by following published protocols (Scheme 1)15,26. Likewise, previously reported intermediate 13 was utilised to synthesise 14, which was coupled to the pyridine warhead through a Heck reaction to generate compound 7 (Scheme 1)27.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic protocol of compounds 6, 7, 8 and 10.

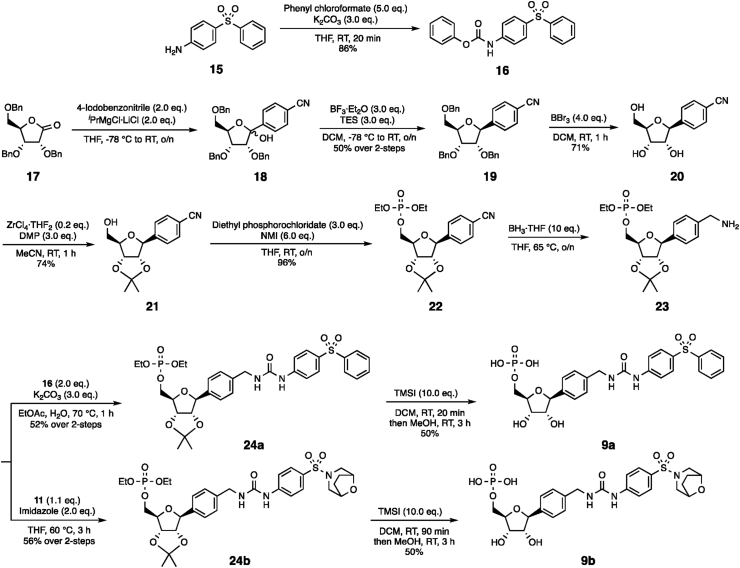

To synthesise 9a, we started by converting commercially available aniline 15 to carbamate 16 by following a similar protocol to that used previously15. Ribonolactone 17 was alkylated to form 18 as a mixture of isomers and deoxygenation gave nucleoside 19 as a single diastereoisomer, in accordance with the established selectivity of this rection28. 19 was debenzylated to compound 20 using published conditions28, then converted to acetal 21. Subsequent phosphorylation reaction generated 22, which was reduced to the corresponding amine 23 using borane29, 30, 31, 32, 33. The sugar warhead 23 was reacted with the previously synthesised carbamates 16 and 11 to afford the protected intermediates 24a and 24b, which were deprotected to provide the desired compounds 9a and 9b respectively (Scheme 2) 34,35.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic protocol for compounds 9a and 9b.

3. Conclusions

Enhancing NAD+ levels represent a potential therapeutic strategy for treatment of a range of diseases associated with aging. The analysis of the structure–activity relationships (SAR) and binding mode of molecules that combine the structural features of known NAMPT activators and inhibitors conducted here reveals areas clearly divergent SAR, highlighting likely changes in the binding mode between chemically related NAMPT activators and inhibitors. The hypothesis that the critical 4-pyridiyl (or aza-hetrocycle) in such compounds makes a water mediated interaction with NAMPT, or more probably an interaction bridged by a NAMPT-chelated magnesium ion, led to the design of a novel NAMPT activator warhead which demonstrates equivalent or superior activity to the pyridines in in vitro models. This work will inform further studies and optimisation to provide drug-like and ultimately clinically developable NAMPT activators.

4. Experimental

4.1. Expression and purification of NAMPT

The plasmid containing the NAMPT (from Mus musculus) along with an N-terminal His6-Tag and TEV cutting site was transformed into E. coli Rosetta cells. The cells were grown in Terrific Broth medium containing ampicillin. Protein expression was induced at an OD600 of ∼2 by using 0.5 mmol/L, isopropyl-thio-galactopyranoside (IPTG) at 18 °C. The next morning cells were harvested by centrifugation (6000×g). Typically, 20 g of cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mmol/L HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mmol/L NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mmol/L TCEP, 20 mmol/L imidazole) and subsequently disintegrated by sonication on ice. Cell fragments were separated by centrifugation (30 min, 21,000×g, 4 °C) and the supernatant was loaded onto an immobilized metal affinity sepharose resin (Chelating Sepharose™ Fast Flow, GE Healtcare, Uppsala, Sweden) pre-equilibrated with 30 mL lysis buffer. After washing the resin with ∼100 mL lysis buffer, the protein was eluted by an imidazole step gradient (50, 100, 200, 300 mmol/L). Fractions containing protein were pooled together and dialysed overnight against 1 L of final buffer (25 mmol/L HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mmol/L NaCl, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mmol/L TCEP) at 4 °C. Additionally, TEV protease was added (protein:TEV ∼20:1 molar ratio) to cleave the tag. The protein solution was loaded onto Nickel-Sepharose beads again to remove TEV protease and uncleaved protein. The flow through fraction was concentrated to approx. 4–5 mL and loaded onto Superdex 200 16/60 HiLoad size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) column equilibrated with final buffer. Following elution of the protein the pure fractions were combined and concentrated to approximately 20 mg/mL.

4.2. Crystallisation

NAMPT was co-crystallized using the sitting-drop vapour diffusion method by mixing protein (4–6 mg/mL), inhibitor of interest (0.5–1 mmol/L) and reservoir conditions in 2:1, 1:1, and 1:2 ratios at 20 °C. Crystals appear after 1 day in reservoir solution containing 20%–30% PEG 3350, 0.1 mol/L NaCl, 0.1 mol/L HEPES, pH 8.2.

4.3. Enzyme activity assay

The enzymatic assay was adapted from a published protocol21. NAMPT (36 nmol/L) with PRPP (50 μmol/L) and ATP (2 mmol/L) in TMD buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 10 mmol/L MgCl2, 2 mmol/L DTT, pH 7.5) were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min in 96-well opaque bottom plate (final volume 180 μL per well). The reactions were performed in the presence of NAMPT activators, inhibitors or DMSO control with the final DMSO concentration was 1% in all cases. After 20 min incubation at 37 °C, NAM (10 μL of 125 μmol/L solution in TMD buffer, to give a final concentration of 25 μmol/L) was added to each well and further incubated for 20 min at 37 °C15. NMN was assayed using a chemical method which converts NMN into a fluorescent derivative by mixing NMN-containing samples with 20 μL of 20% acetophenone (in DMSO) and 20 μL of 2 mol/L KOH aqueous solution. Following regent addition, the mixture was kept for 5 min at ambient temperature then 90 μL of 80% formic acid was added to each sample. Fluorescence was measured using a Hidex sense microplate reader with excitation filter 355 ± 40 nm and emission 460 ± 20 nm, and NMN concentrations calculated using a NMN calibration curve performed in the same plate.

4.4. Cellular studies

Human A549 lung carcinoma cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (with 1% l-glutamine), 10% fetal bovine serum (T175 cell culture flasks). Plated in 96-well plates (white plate, clear bottom with lid, Costar, Cat.# 3610) at approximately 800 cells per well in 50 μL of medium and treated with testing compounds or DMSO (control) for 4 h at 37 °C. After the incubation, plates were equilibrated to ambient temperature and 50 μL of NAD/NADH-Glo™ Assay solution (Promega, Cat.#G9071) was added. Plates were incubated at ambient temperature for 1 h and luminescence was measured using a plate reader (FLUOstar OPTIMA, BMG Labtech). NAD+/NADH concentrations were calculated using an NAD+ calibration curve performed in the same plate.

4.5. Molecular docking

To reveal the binding model of compounds 6 and 10, we built a complex of compounds 6, 10 and NAMPT based on the crystal structures of NAMPT with compound 9a (PDB code: 7Q8T) and published PRPP-bound structure of BF3-His247 NAMPT (PDB code: 3DKL). Compound 9a was removed from the crystal structure and all hydrogen atoms added. The chemical structures of compounds 6 and 10 were sketched in SYBYL (Tripos, St Louis, MO, USA) and protonated, if appropriate, before energy minimization using the Tripos force field (Gasteiger–Hückel charges, distance-dependent dielectric constant = 4.0, nonbonded interaction cutoff = 8 Å and termination criterion = energy gradient <0.05 kcal/(mol × Å) for 10,000 iterations). The molecular docking was performed using GOLD Suite 5.1 (Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge, UK). The original ligand was extracted and the new ligands (compounds 6 and 10) were fit into the binding pocket of compound 9a in NAMPT. The ChemScore and GoldScore fitness scoring functions were utilized to identify lowest energy binding poses. The exported complexes were edited using UCSF Chimera 1.13.1 software.

4.6. General chemistry experimental

Commercial reagents and solvents were used directly without further purification. Anhydrous solvents were supplied by Acros Organics over 4 Å molecular sieves. Glassware such as round bottom flasks and ace pressure tubes were dried in the oven first and then heated with a heating gun under vacuum. Progress of the reaction was monitored with TLC using F245 aluminium-backed silica gel plate purchased from Merck. UV light (254/365 nm) and KMnO4 were used for visualisation. The following cooling baths were used: 0 °C (ice/water), −10 °C (ice/MeOH), −40 °C (dry ice/MeCN) and −78 °C (dry ice/acetone). For heating reactions, paraffin oil baths and stirrer hotplates were employed and the temperature was monitored using a thermometer. Compounds were purified by flash column chromatography (silica gel) using Geduran silica gel 60 or reverse phase flash column chromatography CombiFlash® machine using 5.5, 15.5 or 30.0 g C18 Gold columns with 20–40 μm silica, eluting with a gradient 0%–100% MeCN in water as acid method (0.1% formic acid as modifier) or base method (0.1% NH4OH as modifier) as indicated, or by prep HPLC using C18 Kinetex HPLC column with 5 μm silica, eluting with a gradient 0%–100% MeCN in water. Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker Tensor 27 FT-IR using an ATR attachment. NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV400 (1H = 400 MHz, 13C = 101 MHz, 19F = 376 MHz, 31P = 162 MHz) spectrometer in commercial deuterated solvents. Chemical shift (δ) were reported in ppm and spectra were recorded in CDCl3 referenced to residual CHCl3 (δH 7.26 ppm, δC 77.16 ppm), CD3OD referenced to residual MeOH (δH 3.31 ppm, δC 49.00 ppm) or (CD3)2SO referenced to residual DMSO (δH 2.50 ppm, δC 39.52 ppm). Coupling constants J were reported in Hz to the nearest 0.1 Hz. Coupling constants that were non-identical were reported as averages. Data were processed on Mestrenova 14.0.1. Unless stated otherwise, 31P were reported decoupled to 1H, 19F were reported coupled to 1H. All 1H and 13C assignments were supported by two-dimensional spectrum 1H–1H COSY, 1H–1H NOESY, 1H–13C HSQC and 1H–13C HMBC. LC data was obtained using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC PDA detector scanning between 210 and 400 nm. LC‒MS retention time was reported at tR in minutes. Mass spectra were recorded on Waters ACQUITY QDa detector. All solvents were LC‒MS grade (Fisher Optima) and were modified by the addition of 0.1% formic acid (Fisher Optima) as acid method or NH4OH (Fisher, 28% v/v aq. solution) as base method as indicated. Table 1 detailed the gradient used on a standard 4-min run with a 0.60 mL/min flow rate. All high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was performed on a Thermofisher Exactive Plus EMR Orbitrap.

Table 1.

Gradient used on a standard 4-min run with a 0.60 mL/min flow rate for LC‒MS.

| Time (min) | MeCN in water (% v/v) |

|---|---|

| 0 to 0.50 | 5:95 |

| 0.50 to 2.50 | 5:95 to 95:5 |

| 2.50 to 3.00 | 95:5 |

| 3.00 to 3.10 | 95:5 to 5:95 |

| 3.10 to 4.00 | 5:95 |

1-(4-((8-Oxa-3-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-yl)sulfonyl)phenyl)-3-(pyridin-4-yl)urea (6).

11 (80 mg, 0.21 mmol) was dissolved in THF (10 mL), pyridin-4-ylmethanamine (22 mg, 0.21 mmol) and TEA (3.45 × 10‒2 mL, 0.25 mmol) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was heated up to 60 °C and stirred overnight under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a yellow oil. The crude material was purified by flash chromatography (silica gel), eluting with 3% MeOH in DCM to afford the title compound (69 mg, 0.17 mmol, 81%) as a colorless oil. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 9.35 (s, 1H), 8.53–8.47 (m, 2H), 7.693–7.62 (m, 2H), 7.56 (d, 2H, J = 8.7 Hz), 7.323–7.26 (m, 2H), 6.98 (t, 1H, J = 6.1 Hz), 4.33 (dd, 4H, J = 12.9, 4.1 Hz), 3.20 (d, 2H, J = 11.0 Hz), 2.38 (dd, 2H, J = 11.3, 2.3 Hz), 1.78 (d, 4H, J = 2.5 Hz). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 154.9, 149.6, 149.3, 145.0, 128.8, 126.2, 122.0, 117.3, 72.8, 50.9, 41.9, 27.5. MS m/z (ES+) 403.4 [M+H]+.

(E)-N-(4-(1-Benzoylpiperidin-4-yl)butyl)-3-(pyridin-4-yl)acrylamide (7).

4-Iodopyridine (33 mg, 0.16 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DMF (3 mL), 14 (50 mg, 0.16 mmol), tBuXPhos Pd Gen-3 (25 mg, 0.03 mmol) and TEA (0.22 mL, 1.60 mmol) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred at 65 °C overnight under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (30 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a brown oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using acid method to afford the title compound (35 mg, 0.09 mmol, 56%) as a colourless oil. Vmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3057, 2180, 1968, 1671, 1625, 1552, 1445, 1341, 1282, 1224, 1113, 979, 814, 708, 543. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 8.52–8.46 (m, 2H), 7.42 (d, 1H, J = 15.6 Hz), 7.28 (t, 5H, J = 2.5 Hz), 7.18 (dd, 2H, J = 6.0, 4.3 Hz), 6.49 (d, 1H, J = 15.7 Hz), 6.29 (t, 1H, J = 5.9 Hz), 4.58 (s, 1H), 3.63–3.58 (m, 1H), 3.25 (q, 2H, J = 6.8 Hz), 2.85 (s, 1H), 2.64 (s, 1H), 1.77-0.86 (m, 10H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 170.5, 165.0, 150.5, 142.5, 138.0, 136.5, 129.7, 128.6, 126.9, 125.7, 121.8, 48.2, 42.7, 39.9, 36.2, 36.2, 33.1, 32.1, 29.9, 24.1. MS m/z (ES+) 392.4 [M+H]+. HRMS C24H28N3O2 requires [M‒H]‒ 390.2186, found [M‒H]‒ 390.2187.

4-(1-(6-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-2-yloxy)hexyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)pyridine (8).

12 (100 mg, 0.34 mmol) was dissolved in tert-butanol (2 mL), 4-ethynylpyridine (35 mg, 0.34 mmol), sodium ascorbate (27 mg, 0.14 mmol), CuSO4 (2 mg, 1.36 × 10‒2 mmol) and water (2 mL) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred at 40 °C overnight under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (20 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 15 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a brown oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using acid method to afford the title compound (112 mg, 0.28 mmol, 82%) as a yellow oil. Vmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3131, 3057, 3031, 2938, 2861, 1709, 1609, 1433, 1260, 1220, 1122, 1044, 991, 911, 753, 729, 698, 532. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 8.56 (s, 2H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, 2H, J = 5.7 Hz), 7.48–7.40 (m, 2H), 7.33–7.15 (m, 5H), 6.98–6.83 (m, 2H), 4.21 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.85 (t, 2H, J = 6.1 Hz), 1.78 (q, 2H, J = 7.3 Hz), 1.67–1.56 (m, 2H), 1.34 (dtd, 2H, J = 11.7, 9.0, 8.0, 6.1 Hz), 1.28-1.15 (m, 2H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 155.9, 150.0, 145.0, 138.7, 138.6, 131.0, 131.0, 129.7, 128.8, 127.9, 126.9, 121.3, 121.1, 120.2, 112.7, 68.1, 50.4, 30.1, 28.9, 25.9, 25.4. MS m/z (ES+) 399.4 [M+H]+. HRMS C25H26N4ONa requires [M+Na]+ 421.1983, found [M+Na]+ 421.1999.

((2R,3S,4R,5S)-3,4-Dihydroxy-5-(4-((3-(4-(phenylsulfonyl)phenyl)ureido)methyl)phenyl)tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)methyldihydrogenphosphate (9a).

24a (56 mg, 0.08 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DCM (10 mL), TMSI (0.11 mL, 0.83 mmol) was added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred at RT for 20 min under argon atmosphere and then MeOH (5 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred at RT for another 3 h and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide an orange oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using base method to afford the title compound (24 mg, 0.04 mmol, 50%) as a colourless oil. Vmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3325, 2953, 2173, 2155, 1698, 1683, 1590, 1542, 1337, 1227, 1159, 1107, 946, 733, 598, 583. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δH 7.94–7.87 (m, 2H), 7.82–7.74 (m, 2H), 7.65–7.49 (m, 5H), 7.40 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), 7.28 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 4.68 (d, 1H, J = 6.9 Hz), 4.35 (s, 2H), 4.16 (dd, 1H, J = 5.4, 3.6 Hz), 4.09 (d, 1H, J = 4.2 Hz), 4.10-3.97 (m, 2H), 3.91 (dd, 1H, J = 6.9, 5.4 Hz). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δC 157.3, 146.6, 143.7, 140.8, 140.1, 134.5, 134.2, 130.5, 129.9, 128.3, 128.3, 127.8, 119.2, 85.2, 85.0 (d, JCP = 8.8 Hz), 79.0, 73.2, 66.4 (d, JCP = 5.2 Hz), 44.3. 31PNMR (162 MHz, CD3OD) δP 1.4 (s). MS m/z (ES+) 579.2 [M+H]+. HRMS C25H26N2O10PS requires [M‒H]‒ 577.1048, found [M‒H]‒ 577.1051.

((2R,3S,4R,5S)-5-(4-((3-(4-((8-Oxa-3-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-yl)sulfonyl)phenyl)ureido)methyl)phenyl)-3,4-dihydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)methyldihydrogen phosphate (9b).

24b (109 mg, 0.15 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DCM (10 mL), TMSI (0.21 mL, 1.54 mmol) was added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred at RT for 90 min under argon atmosphere and then MeOH (5 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred at RT for another 3 h and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide an orange oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using base method to afford the title compound (49 mg, 0.08 mmol, 53%) as a colourless oil. Vmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3336, 2921, 2155, 1698, 1589, 1541, 1446, 1319, 1229, 1152, 1107, 1018, 733, 593, 567. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δH 7.67–7.57 (m, 4H), 7.42 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 7.33 (d, 2H, J = 7.9 Hz), 4.74 (d, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz), 4.38 (d, 4H, J = 4.3 Hz), 4.20 (t, 1H, J = 4.6 Hz), 4.14 (q, 1H, J = 4.3 Hz), 4.01 (dt, 3H, J = 12.5, 5.5 Hz), 3.34–3.26 (m, 2H), 2.54 (d, 2H, J = 11.2 Hz), 1.91 (d, 4H, J = 2.7 Hz). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δC 157.5, 145.9, 140.2, 139.7, 129.8, 128.4, 128.0, 127.9, 119.2, 85.0, 84.7 (d, JCP = 8.8 Hz), 78.5, 75.0, 72.9, 65.9 (d, JCP = 4.9 Hz), 52.1, 44.1, 28.4. 31PNMR (162 MHz, CD3OD) δP 2.1 (s). MS m/z (ES+) 614.3 [M+H]+. HRMS C25H31N3O11PS requires [M‒H]‒ 612.1417, found [M‒H]‒ 612.1422.

1-(4-((8-Oxa-3-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-yl)sulfonyl)phenyl)-3-(4(hydroxymethyl)benzyl)urea (10).

11 (100 mg, 0.26 mmol) was dissolved in THF (10 mL), (4-(aminomethyl)phenyl)methanol (35 mg, 0.26 mmol), imidazole (35 mg, 0.52 mmol) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was heated up to 50 °C and stirred overnight under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a yellow oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using acid method to afford the title compound (95 mg, 0.22 mmol, 85%) as a white solid. Vmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3410, 3322, 2976, 2867, 2359, 1672, 1542, 1509, 1205, 917, 733. 591, 577, 528. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 9.12 (s, 1H), 7.68–7.61 (m, 2H), 7.60–7.52 (m, 2H), 7.31–7.22 (m, 4H), 6.80 (t, 1H, J = 5.9 Hz), 5.13 (t, 1H, J = 5.7 Hz), 4.47 (d, 2H, J = 5.7 Hz), 4.31 (t, 4H, J = 4.6 Hz), 3.25-3.14 (m, 2H), 2.41 (dd, 2H, J = 11.4, 2.3 Hz), 1.86–1.74 (m, 4H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 154.7, 145.0, 141.1, 138.3, 128.7, 126.9, 126.5, 126.2, 117.1, 72.7, 62.7, 50.9, 42.6, 27.4. MS m/z (ES+) 432.4 [M+H]+. HRMS C21H25N3O5SNa requires [M+Na]+ 454.1390, found [M+Na]+ 454.1407.

Phenyl (4-((8-oxa-3-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-yl)sulfonyl)phenyl)carbamate (11).

4-((8-Oxa-3-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-yl)sulfonyl)aniline (970 mg, 3.62 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (50 mL), phenyl chloroformate (1.36 mL, 10.86 mmol) and K2CO3 (2497 mg, 18.09 mmol) were add under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred for 3 h under argon atmosphere at RT. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (100 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL). The organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a yellow solid. The crude material was washed with cold Et2O to afford the title compound (950 mg, 2.45 mmol, 68%) as a white solid. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.73–7.66 (m, 2H), 7.61 (d, 2H, J = 8.8 Hz), 7.46–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.34–7.23 (m, 2H), 7.23–7.16 (m, 2H), 4.36 (dd, 2H, J = 4.5, 2.3 Hz), 3.41–3.33 (m, 2H), 2.62 (dd, 2H, J = 11.2, 2.2 Hz), 2.06–1.88 (m, 4H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 151.4, 150.3, 141.9, 130.3, 129.7, 129.2, 126.3, 121.7, 118.4, 73.8, 51.2, 27.9. MS m/z (ES+) 389.4 [M+H]+.

2-((6-Azidohexyl)oxy)-1,1′-biphenyl (12).

A solution of 6-([1,1′-biphenyl]-2-yloxy)hexan-1-ol (200 mg, 0.74 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (15 mL) was cooled down to 0 °C, DBU (0.33 mL, 2.22 mmol) and DPPA (0.48 mL, 2.22 mmol) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min under argon atmosphere and NaN3 (144 mg, 2.22 mmol) was added. The mixture was heated up to 100 °C and stirred for 2 h under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (30 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a dark-brown oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using base method to afford the title compound (150 mg, 0.51 mmol, 69%) as a colourless oil. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.52–7.45 (m, 2H), 7.39–7.17 (m, 5H), 6.97 (td, 1H, J = 7.5, 1.2 Hz), 6.92 (dd, 1H, J = 8.2, 1.1 Hz), 3.91 (t, 2H, J = 6.3 Hz), 3.15 (t, 2H, J = 6.9 Hz), 1.66 (dt, 2H, J = 7.9, 6.2 Hz), 1.50 (q, 2H, J = 7.0 Hz), 1.32 (ttd, 4H, J = 15.2, 6.2, 4.6, 2.5 Hz). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 156.1, 138.8, 131.2, 131.0, 129.8, 128.7, 128.0, 127.0, 121.0, 112.7, 68.4, 51.5, 29.1, 28.9, 26.5, 25.9. MS characterization was not possible due to the poor ionisation.

(4-(4-Aminobutyl)piperidin-1-yl) (phenyl)methanone (13).

(4-(4-Azidobutyl)piperidin-1-yl) (phenyl)methanone (100 mg, 0.35 mmol) was dissolved in THF (10 mL), PPh3 (139 mg, 0.53 mmol) and water (0.04 mL, 2.10 mmol) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was heated up to 75 °C and stirred for 3 h under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (30 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a colourless oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using acid method to afford the title compound (70 mg, 0.27 mmol, 77%) as a colourless oil. 1HNMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δH 7.51–7.41 (m, 3H), 7.44–7.35 (m, 2H), 4.62 (d, 1H, J = 12.9 Hz), 3.71 (d, 1H, J = 13.3 Hz), 3.16–3.03 (m, 1H), 2.96–2.89 (m, 2H), 2.84 (t, 1H, J = 12.7 Hz), 1.86 (d, 1H, J = 13.2 Hz), 1.73–1.54 (m, 3H), 1.44 (dtd, 2H, J = 15.2, 7.1, 2.9 Hz), 1.38–1.27 (m, 2H), 1.16 (dd, 2H, J = 38.6, 19.2, 11.5 Hz). 13CNMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δC 172.3, 137.3, 130.9, 129.7, 127.7, 49.3, 43.7, 40.7, 37.0, 36.8, 33.8, 33.0, 28.7, 24.5. MS m/z (ES+) 261.4 [M+H]+.

N-(4-(1-Benzoylpiperidin-4-yl)butyl)acrylamide (14).

13 (148 mg, 0.57 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DCM (20 mL), TEA (0.16 mL, 1.14 mmol) and acryloyl chloride (0.06 mL, 0.68 mmol) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred for 30 min at RT under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (20 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a colourless oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using acid method to afford the title compound (107 mg, 0.34 mmol, 60%) as a colourless oil. νmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3289, 2929, 2856, 1610, 1545, 1438, 1280, 1485, 985, 708. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.41–7.31 (m, 5H), 6.24 (dd, 1H, J = 17.0, 1.6 Hz), 6.07 (dd, 1H, J = 17.0, 10.2 Hz), 5.99 (d, 1H, J = 6.3 Hz), 5.58 (dd, 1H, J = 10.2, 1.6 Hz), 4.65 (s, 1H), 3.70 (s, 1H), 3.28 (td, 2H, J = 7.3, 5.9 Hz), 2.93 (s, 1H), 2.72 (s, 1H), 1.84–1.72 (m, 1H), 1.66–1.55 (m, 1H), 1.55–0.91 (m, 8H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 170.4, 165.7, 136.5, 131.1, 129.6, 128.5, 126.9, 126.2, 48.2, 42.6, 39.6, 36.2, 36.1, 33.0, 32.1, 29.9, 24.1. MS m/z (ES+) 315.3 [M+H]+. HRMS C19H26N2O2Na requires [M+Na]+ 337.1868, found [M+Na]+ 337.1886.

Phenyl (4-(phenylsulfonyl)phenyl)carbamate (16).

15 (4.92 g, 21.09 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (200 mL), phenyl chloroformate (13.23 mL, 105.43 mmol) and K2CO3 (0.87 g, 63.27 mmol) were add under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred for 20 min at RT under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (50 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 150 mL). The organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a brown solid. The crude material was purified by flash chromatography (silica gel), eluting with 1% MeOH in DCM to afford the title compound (6.40 g, 18.14 mmol, 86%) as a white solid. 1HNMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO) δH 10.76 (s, 1H), 7.97–7.90 (m, 4H), 7.77–7.70 (m, 2H), 7.69–7.57 (m, 3H), 7.43 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 7.31–7.20 (m, 3H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, (CD3)2SO) δC 151.6, 150.2, 143.6, 141.7, 134.5, 133.4, 129.7, 129.5, 128.9, 127.0, 125.7, 121.9, 118.5. MS m/z (ES+) 354.1 [M+H]+.

4-((3R,4R,5R)-3,4-Bis(benzyloxy)-5-((benzyloxy)methyl)-2-hydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-yl)benzonitrile (18).

A solution of 4-iodobenzonitrile (109 mg, 0.48 mmol) in anhydrous THF (8 mL) was cooled down to −78 °C and i-PrMgCl·LiCl (0.37 mL from a 1.3 mol/L solution in THF, 0.48 mmol) was added dropwise under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h under −78 °C to form the yellow turbo Grignard solution. The ribonolactone 17 (100 mg, 0.24 mmol) anhydrous THF solution (2 mL) was added to the Grignard solution dropwise and stirred overnight under argon atmosphere at RT. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (80 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL). The organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a yellow oil. The crude material was taken forward without further purification. MS m/z (ES+) 544.3 [M+Na]+.

4-((2S,3S,4R,5R)-3,4-Bis(benzyloxy)-5-((benzyloxy)methyl)tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)benzonitrile (19).

A solution of crude 18 (0.24 mmol as hypothetic quantitative yield from last step) in anhydrous DCM (15 mL) was cooled down to −78 °C, BF3·Et2O (0.19 mL, 0.72 mmol) and TES (0.12 mL, 0.72 mmol) were added dropwise under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at −78 °C and then allowed to reach RT and stirred overnight under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was quenched with a saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution (50 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL). The organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a pink oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using acid method to afford the title compound (60 mg, 0.12 mmol, 50% over two steps) as a colourless oil. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.49 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.44 (d, 2H, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.35–7.06 (m, 15H), 4.98 (d, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz), 4.59–4.24 (m, 7H), 3.98 (dd, 1H, J = 5.1, 3.3 Hz), 3.71 (dd, 1H, J = 7.3, 5.0 Hz), 3.63 (dd, 1H, J = 10.4, 3.9 Hz), 3.56 (dd, 1H, J = 10.4, 3.5 Hz). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 146.2, 138.0, 137.8, 137.5, 132.2, 128.6, 128.5, 128.3, 128.1, 128.0, 128.0, 127.9, 127.8, 127.0, 119.1, 111.4, 84.0, 82.4, 81.6, 77.4, 73.7, 72.6, 72.1, 70.5. MS m/z (ES+) 506.4 [M+H]+.

4-((2S,3R,4S,5R)-3,4-Dihydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)benzonitrile (20).

19 (790 mg, 1.56 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous DCM (30 mL) and BBr3 (6.26 mL from a 1 mol/L solution in DCM, 6.26 mmol) was added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred for 1 h under argon atmosphere at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was quenched with MeOH (10 mL) and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a dark-yellow oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using acid method to afford the title compound (261 mg, 1.11 mmol, 71%) as a colourless oil. νmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3449, 2932, 2883, 2232, 1610, 1411, 1332, 1114, 1055, 827, 561. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.70 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 7.65 (d, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz), 4.76 (d, 1H, J = 7.1 Hz), 4.08–3.97 (m, 2H), 3.85–3.76 (m, 2H), 3.72 (dd, 1H, J = 12.0, 4.6 Hz). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 148.1, 133.1, 128.0, 119.8, 112.2, 86.9, 84.3, 79.3, 73.0, 63.5. MS m/z (ES+) 234.2 [M‒H]‒. HRMS C12H12NO4 requires [M‒H]‒ 234.0769, found [M‒H]‒ 234.0772.

4-((3aS,4S,6R,6aR)-6-(Hydroxymethyl)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrofuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)benzonitrile (21).

20 (89 mg, 0.38 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous MeCN (15 mL), ZrCl4·THF2 (29 mg, 0.08 mmol) and DMP (0.14 mL, 1.14 mmol) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred for 1 h under argon atmosphere at RT. The reaction mixture was quenched with a saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution (30 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL). The organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a yellow oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using base method to afford the title compound (77 mg, 0.28 mmol, 74%) as a colourless oil. νmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3483, 2936, 2881, 2342, 2229, 1611, 1382, 1212, 1156, 1077, 857, 829, 558. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.68–7.62 (m, 2H), 7.51 (d, 2H, J = 8.2 Hz), 4.90 (d, 1H, J = 5.7 Hz), 4.74 (dd, 1H, J = 6.9, 4.1 Hz), 4.46 (dd, 1H, J = 6.9, 5.7 Hz), 4.21 (q, 1H, J = 3.9 Hz), 3.95 (dd, 1H, J = 12.2, 3.2 Hz), 3.82 (d, 1H, J = 12.1 Hz), 1.85 (s, 1H), 1.62 (s, 3H), 1.36 (s, 3H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 145.0, 132.5, 126.4, 118.9, 115.6, 111.9, 86.7, 85.1, 84.7, 81.6, 62.9, 27.7, 25.6. MS m/z (ES+) 274.3 [M‒H]‒. HRMS C15H17NO4Na requires [M+Na]+ 298.1037, found [M+Na]+ 298.1050.

((3aR,4R,6S,6aS)-6-(4-Cyanophenyl)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrofuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)methyl diethyl phosphate (22).

21 (68 mg, 0.25 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (15 mL), NMI (0.12 mL, 1.48 mmol) and diethyl phosphorochloridate (0.11 mL, 0.74 mmol) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was stirred overnight under argon atmosphere at RT. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (20 mL) and extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a yellow oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using base method to afford the title compound (98 mg, 0.24 mmol, 96%) as a colourless oil. νmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 2985, 2937, 2908, 2228, 1611, 1373, 1264, 1213, 1078, 1023, 979, 813, 557, 511. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 7.67–7.60 (m, 2H), 7.52 (d, 2H, J = 8.1 Hz), 4.91 (d, 1H, J = 5.5 Hz), 4.74 (dd, 1H, J = 6.7, 3.5 Hz), 4.45 (dd, 1H, J = 6.7, 5.5 Hz), 4.36–4.18 (m, 3H), 4.11 (p, 4H, J = 7.3 Hz), 1.62 (s, 3H), 1.37–1.28 (m, 9H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 145.1, 132.4, 126.4, 118.9, 115.5, 111.8, 86.7, 85.3, 82.7 (d, JCP = 7.7 Hz), 81.6, 66.8 (d, JCP = 5.7 Hz), 64.2, 64.2, 27.7, 25.7, 16.3, 16.2. 31PNMR (162 MHz, CDCl3) δP −0.9 (s). MS m/z (ES+) 412.4 [M+H]+. HRMS C19H26NO7PNa requires [M+Na] 434.1322, found [M+Na] 434.1339.

((3aR,4R,6S,6aS)-6-(4-(Aminomethyl)phenyl)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrofuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)methyl diethyl phosphate (23).

22 (88 mg, 0.21 mmol) was dissolved in THF (13 mL) and BH3·THF (2.14 mL from a 1 mol/L solution in THF, 2.14 mmol) was added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was heated up to 60 °C and stirred overnight under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was quenched with MeOH (8 mL) and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a colourless oil. The crude material was taken forward without further purification. MS m/z (ES+) 416.4 [M+H]+.

((3aR,4R,6S,6aS)-2,2-Dimethyl-6-(4-((3-(4-(phenylsulfonyl)phenyl)ureido)methyl)phenyl)tetrahydrofuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)methyldiethyl phosphate (24a).

The crude 23 (0.21 mmol as hypothetic quantitative yield from last step) was dissolved in EtOAc (15 mL), K2CO3 (89 mg, 0.64 mmol), 16 (151 mg, 0.43 mmol) and water (5 mL) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was heated up to 70 °C and stirred for 1 h under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a yellow oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using base method to afford the title compound (75 mg, 0.11 mmol, 52% over two steps) as a colourless oil. νmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3356, 2986, 2935, 1703, 1590, 1539, 1305, 1244, 1153, 1106, 1027, 839, 732, 689, 592, 566. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 8.25 (s, 1H), 7.85 (dd, 2H, J = 7.3, 1.8 Hz), 7.71–7.63 (m, 2H), 7.56–7.41 (m, 5H), 7.24 (s, 1H), 7.17 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.12 (t, 1H, J = 5.6 Hz), 4.84 (d, 1H, J = 4.9 Hz), 4.64 (dd, 1H, J = 6.9, 3.8 Hz), 4.44 (dd, 1H, J = 6.8, 4.9 Hz), 4.39–4.12 (m, 5H), 4.05 (p, 4H, J = 7.2 Hz), 1.59 (s, 3H), 1.34–1.19 (m, 9H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 155.3, 145.0, 142.3, 138.9, 138.5, 133.1, 133.0, 129.4, 129.1, 127.8, 127.4, 126.1, 118.1, 115.4, 87.0, 85.8, 82.5 (d, JCP = 7.3 Hz), 81.2, 67.2 (d, JCP = 5.9 Hz), 64.5, 64.5, 43.8, 27.6, 25.6, 16.2, 16.2. 31PNMR (162 MHz, CDCl3) δP −1.6 (s). MS m/z (ES+) 675.3 [M+H]+. HRMS C32H39N2O10PSNa requires [M+Na] 697.1931, found [M+Na] 697.1955.

((3aR,4R,6S,6aS)-6-(4-((3-(4-((8-Oxa-3-azabicyclo[3.2.1]octan-3-yl)sulfonyl)phenyl)ureido)methyl)phenyl)-2,2-dimethyltetrahydrofuro[3,4-d][1,3]dioxol-4-yl)methyldiethylphosphate (24b).

The crude 23 (0.14 mmol as hypothetic quantitative yield from last step) was dissolved in THF (10 mL), 11 (62 mg, 0.16 mmol) and imidazole (18 mg, 0.26 mmol) were added under argon atmosphere. The mixture was heated up to 60 °C and stirred for 3 h under argon atmosphere. The reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL) and the organic phases were combined, dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide a yellow oil. The crude material was purified by CombiFlash® using acid method to afford the title compound (62 mg, 0.09 mmol, 56% over two steps) as a colorless oil. νmax (thin film, ATR)/cm‒1: 3359, 2983, 2957, 2909, 2247, 1702, 1591, 1538, 1349, 1216, 1159, 1105, 1023, 946, 729, 582, 493. 1HNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δH 8.28 (s, 1H), 7.55 (d, 2H, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.49 (d, 2H, J = 9.0 Hz), 7.28 (d, 2H, J = 8.2 Hz), 7.21 (d, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.12 (t, 1H, J = 5.4 Hz), 4.85 (d, 1H, J = 4.9 Hz), 4.65 (dd, 1H, J = 6.8, 3.7 Hz), 4.45 (dd, 1H, J = 6.8, 4.9 Hz), 4.40–4.13 (m, 7H), 4.07 (p, 4H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.29 (dd, 2H, J = 11.0, 4.4 Hz), 2.55 (dt, 2H, J = 11.1, 2.2 Hz), 1.94 (ddd, 4H, J = 17.5, 12.5, 8.0, 3.9 Hz), 1.59 (s, 3H), 1.34–1.27 (m, 9H). 13CNMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δC 155.4, 144.7, 138.8, 138.5, 129.0, 127.8, 127.1, 126.1, 117.7, 115.4, 86.9, 85.8, 82.4 (d, JCP = 7.3 Hz), 81.1, 73.8, 67.2 (d, JCP = 5.8 Hz), 64.6, 64.5, 51.2, 27.9, 27.6, 25.6, 16.3, 16.2. 31PNMR (162 MHz, CDCl3) δP −1.6 (s). MS m/z (ES+) 710.3 [M+H]+. HRMS C32H22N3O11PSNa requires [M+Na]+ 732.2301, found [M+Na]+ 732.2326.

Acknowledgments

Siyuan Tang was funded by the China Sponsorship Council (No. 201709110169). Stefan Knapp and Andreas Krämer are grateful for support by the SGC, a registered charity (number 1097737) that receives funds from AbbVie, Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Eshelman Institute for Innovation, Genome Canada, Innovative Medicines Initiative (EU/EFPIA), Janssen, Merck KGaA Darmstadt Germany, MSD, Novartis Pharma AG, Ontario Ministry of Economic Development and Innovation, Pfizer, São Paulo Research Foundation-FAPESP and Takeda. Stefan Knapp and Andreas Krämer were also supported by the Frankfurt Cancer Institute (FCI) and the DKTK translational cancer network. We would like to thank staff at the Swiss Light Source (SLS) for assisting with data collection and for financial support by the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement number 730872, project CALIPSOplus.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.07.016.

Author contributions

Siyuan Tang and Sam Butterworth conceptualised the research. Siyuan Tang conducted chemical synthesis and structural characterisation under the supervision of Sam Butterworth. In vitro assays were performed by Siyuan Tang, Oliver Smith, Miguel Garzon Sanz and Daniel Egbase under the supervision of Sam Butterworth and Paul Caton. Molecular modelling studies were conducted by Siyuan Tang. Crystallography was conducted and analysed by Andreas Krämer under the supervision of Stefan Knapp. Siyuan Tang, Miguel Garzon Sanz, Oliver Smith and Sam Butterworth were involved in data interpretation and discussion. Sam Butterworth and Siyuan Tang co-wrote the manuscript with input from Andreas Krämer and Stefan Knapp. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cantó C., Menzies K., Auwerx J. NAD+ metabolism and the control of energy homeostasis―a balancing act between mitochondria and the nucleus. Cell Metab. 2015;22:31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Covarrubias A.J., Perrone R., Grozio A., Verdin E. NAD+ metabolism and its roles in cellular processes during ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:119–141. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00313-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mouchiroud L., Houtkooper R.H., Moullan N., Katsyuba E., Ryu D., Cantó C., et al. The NAD+/Sirtuin pathway modulates longevity through activation of mitochondrial UPR and FOXO signaling. Cell. 2013;154:430. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgos E.S., Ho M.C., Almo S.C., Schramm V.L. A phosphoenzyme mimic, overlapping catalytic sites and reaction coordinate motion for human NAMPT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903898106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy B.E., Sharif T., Martell E., Dai C., Kim Y., Lee P.W.K., et al. NAD+ salvage pathway in cancer metabolism and therapy. Pharmacol Res. 2016;114:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amici A., Grolla A.A., Del Grosso E., Bellini R., Bianchi M., Travelli C., et al. Synthesis and degradation of adenosine 5′-tetraphosphate by nicotinamide and nicotinate phosphoribosyltransferases. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24:553–564.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang B., Hasan M.K., Alvarado E., Yuan H., Wu H., Chen W.Y. NAMPT overexpression in prostate cancer and its contribution to tumor cell survival and stress response. Oncogene. 2011;30:907–921. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunzner-Toste J., Zhao G., Bauer P., Baumeister T., Buckmelter A.J., Caligiuri M., et al. Discovery of potent and efficacious urea-containing nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) inhibitors with reduced CYP2C9 inhibition properties. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:3531–3538. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasmann M., Schemainda I. FK866, a highly specific noncompetitive inhibitor of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase, represents a novel mechanism for induction of tumor cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7436–7442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh A., Ho Y.C., Zak M., Liu Y., Chen X., Yuen P.W., et al. Structural and biochemical analyses of the catalysis and potency impact of inhibitor phosphoribosylation by human nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. Chembiochem. 2014;15:1121–1130. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201402023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng X., Bauer P., Baumeister T., Buckmelter A.J., Caligiuri M., Clodfelter K.H., et al. Structure-based identification of ureas as novel nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt) inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2013;56:4921–4937. doi: 10.1021/jm400186h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilsbacher J.L., Cheng M., Cheng D., Trammell S.A.J., Shi Y., Guo J., et al. Discovery and characterization of novel nonsubstrate and substrate NAMPT inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16:1236–1245. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldinger S.M., Bischof S.G., Fink-Puches R., Klemke C.D., Dréno B., Bagot M., et al. Efficacy and safety of Apo 866 in patients with refractory or relapsed cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Dermatology. 2016;152:837–839. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang G., Han T., Nijhawan D., Theodoropoulos P., Naidoo J., Yadavalli S., et al. P7C3 neuroprotective chemicals function by activating the rate-limiting enzyme in NAD salvage. Cell. 2014;158:1324–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardell S.J., Hopf M., Khan A., Dispagna M., Sessions E.H., Falter R., et al. Boosting NAD+ with a small molecule that activates NAMPT. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3241. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11078-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pieper A.A., Xie S., Capota E., Estill S.J., Zhong J., Jeffrey M., et al. Discovery of a Pro-Neurogenic, neuroprotective chemical. Cell. 2010;142:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinkerton A.B., Sessions E.H., Hershberger P., Maloney P.R., Peddibhotla S., Hopf M., et al. Optimization of a urea-containing series of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) activators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2021;41 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.128007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akiu M., Tsuji T., Sogawa Y., Terayama K., Yokoyama M., Tanaka J., et al. Discovery of 1-[2-(1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-5-yl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-a]pyridin-6-yl]-3-(pyridin-4-ylmethyl)urea as a potent NAMPT (nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase) activator with attenuated CYP inhibition. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2021;43 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2021.128048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akiu M., Tsuji T., Iida K., Sogawa Y., Terayama K., Yokoyama M., et al. Discovery of DS68702229 as a potent, orally available NAMPT (nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase) activator. Chem Pharm Bull. 2021;69:1110–1122. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c21-00700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L., Liu M., Zu Y., Yao H., Wu C., Zhang R., et al. Optimization of NAMPT activators to achieve in vivo neuroprotective efficacy. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;236 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang R.Y., Qin Y., Lv X.Q., Wang P., Xu T.Y., Zhang L., et al. A fluorometric assay for high-throughput screening targeting nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase. Anal Biochem. 2011;412:8–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgos E.S., Ho M.C., Almo S.C., Schramm V.L. A phosphoenzyme mimic, overlapping catalytic sites and reaction coordinate motion for human NAMPT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13748–13753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903898106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jerome A., Claude B., Monsif B., Romain C., Sandrine H., Samir J., inventors. Sanofi S.A. PCT WO2010109122; 2010. Nicotinamide derivatives, preparation thereof, and therapeutic use thereof as anticancer drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng H., Bagrodia S., Bailey S., Edwards M., Hoffman J., Hu Q., et al. Discovery of the highly potent PI3K/MTOR dual inhibitor PF-04691502 through structure based drug design. Medchemcomm. 2010;1:139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sayers S.R., Beavil R.L., Fine N.H.F., Huang G.C., Choudhary P., Pacholarz K.J., et al. Structure-functional changes in ENAMPT at high concentrations mediate mouse and human beta cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2020;63:313–323. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-05029-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galli U., Ercolano E., Carraro L., Blasi Roman C.R., Sorba G., Canonico P.L., et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of isosteric analogues of FK866, an inhibitor of NAD salvage. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:771–779. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Travelli C., Aprile S., Rahimian R., Grolla A.A., Rogati F., Bertolotti M., et al. Identification of novel triazole-based nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) inhibitors endowed with antiproliferative and antiinflammatory activity. J Med Chem. 2017;60:1768–1792. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonnac L.F., Gao G.Y., Chen L., Patterson S.E., Jayaram H.N., Pankiewicz K.W. Efficient synthesis of benzamide riboside, a potential anticancer agent. Nucleos Nucleot Nucleic Acids. 2007;26:1249–1253. doi: 10.1080/15257770701528222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krohn K., Heins H., Wielckens K. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity of C-glycosidic nicotinamide riboside analogs. J Med Chem. 1992;35:511–517. doi: 10.1021/jm00081a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernández A.R., Kool E.T. The components of XRNA: synthesis and fluorescence of a full genetic set of size-expanded ribonucleosides. Org Lett. 2011;13:676–679. doi: 10.1021/ol102915f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh S., Duffy C.D., Shah S.T.A., Guiry P.J. ZrCl4 as an efficient catalyst for a novel one-pot protection. J Org Chem. 2008;73:6429–6432. doi: 10.1021/jo800932t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou L., Zhang H., Tao S., Ehteshami M., Cho J.H., McBrayer T.R., et al. Synthesis and evaluation of 2,6-modified purine 2′-C-methyl ribonucleosides as inhibitors of HCV replication. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2016;7:17–22. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burkhardt E.R., Matos K. Boron reagents in process chemistry: excellent tools for selective reductions. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2617–2650. doi: 10.1021/cr0406918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung M.E., Lyster M.A. Quantitative dealkylation of alkyl ethers via treatment with trimethylsilyl iodide. A new method for ether hydrolysis. J Org Chem. 1977;42:3761–3764. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jung M.E., Lyster M.A. Cleavage of methyl ethers with iodotrimethylsilane: cyclohexanol from cyclohexyl methyl ether. Org Synth. 2003;6:35. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.