Abstract

Cryoablation (CRA) and microwave ablation (MWA) are two main local treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, which one is more curative and suitable for combining with immunotherapy is still controversial. Herein, CRA induced higher tumoral PD-L1 expression and more T cells infiltration, but less PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells infiltration than MWA in HCC. Furthermore, CRA had better curative effect than MWA for anti-PD-L1 combination therapy in mouse models. Mechanistically, anti-PD-L1 antibody facilitated infiltration of CD8+ T cells by enhancing the secretion of CXCL9 from cDC1 cells after CRA therapy. On the other hand, anti-PD-L1 antibody promoted the infiltration of NK cells to eliminate PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) effect after CRA therapy. Both aspects relieved the immunosuppressive microenvironment after CRA therapy. Notably, the wild-type PD-L1 Avelumab (Bavencio), compared to the mutant PD-L1 atezolizumab (Tecentriq), was better at inducing the ADCC effect to target PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells. Collectively, our study uncovered the novel insights that CRA showed superior curative effect than MWA in combining with anti-PD-L1 antibody by strengthening CTL/NK cell immune responses, which provided a strong rationale for combining CRA and PD-L1 blockade in the clinical treatment for HCC.

Key words: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Immunotherapy, Cryoablation, Microwave ablation, CXCL9, NK cells, Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, Immunosuppressive microenvironment

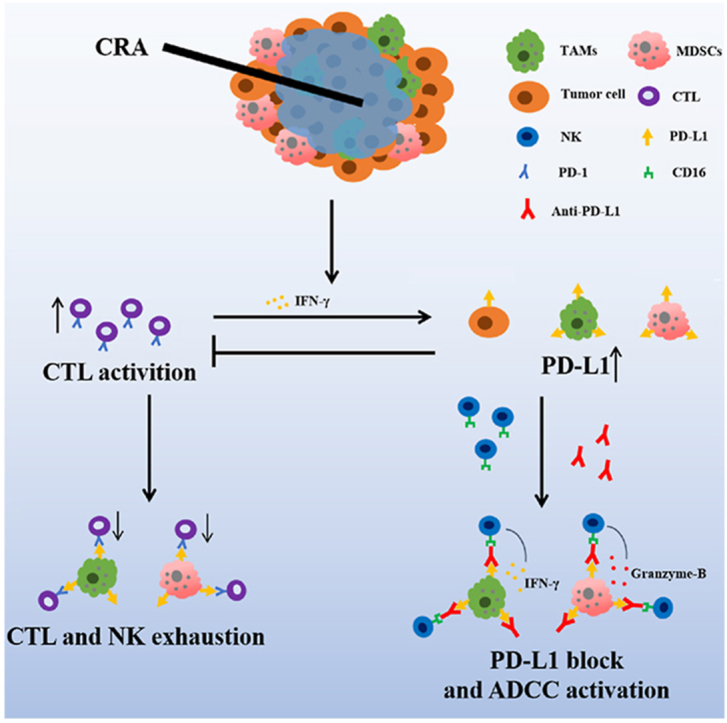

Graphical abstract

Anti-PD-L1 antibody plays a key role in improving curative effect of cryoablation of HCC via blocking PD-L1. It can enhance antitumor activity of CTL/NK cells and eliminating PD-L1highCD11b+ cells by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) effect.

1. Introduction

Cryoablation (CRA) and microwave ablation (MWA) are the most commonly used local hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treatments1,2. Many studies have verified that CRA activates T cells in tumor microenvironment in many types of malignant tumors. It acts by releasing tumor antigen peptides from frozen tumor cells3,4, which are easily degraded at high temperatures. Multiple studies have demonstrated that, compared to other forms of thermal ablation, CRA induces a more potent immune response and up-regulates the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway in HCC5, 6, 7. The combination of ablation and checkpoint block inhibitors (CBI), such as anti-PD-1 or anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, can efficiently induce the abscopal effect and increase the prognosis of colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer8,9. However, some studies have revealed that CRA does not significantly improve the overall survival of HCC patients compared to MWA and radio-frequency-ablation (RFA)10, 11, 12. Whether CRA or MWA combined with immunotherapy can improve therapeutic efficacy for HCC treatments still needs to be further studied.

Importantly, thermal ablation induces immunosuppression in residual tumors by triggering infiltration of immunosuppressive CD11b+ myeloid cells via up-regulating PD-L1, CCL2, TGF-β, Arg-1, and IDO13,14. Therefore, we speculated that CRA may also hinder the anti-tumor effect of CTLs, which is responsible for the unsatisfactory prognosis, like MWA. Recent studies have shown that the combined application of anti-human PD-L1 (Tecentriq) and anti-VEGF (Avastin) antibody results in better overall outcomes compared to sorafenib administered alone to patients with unresectable HCC15, 16, 17. It suggested that anti-PD-L1 antibody may help to improve the efficacy of CRA. Recent studies also found that the expression level of PD-L1 is low in cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and NK cells, but is extremely high in CD11b+ myeloid cells, such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)18,19. Therefore, making good use of the PD-L1 antibody may help diminish CD11b+PD-L1high cells by inducing antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) effect of NK cells, which need to be further explored and verified.

In clinical practice, the most commonly used PD-L1 antibody is atezolizumab (tecentriq), which contains mutant Fc fragment N298A binding sites in order to weaken its affinity to the CD16 molecule. This prevents NK-mediated ADCC from targeting the patient's normal immune cells. Only avelumab (bavencio) has strong ADCC effect and shows outstanding ability to eliminate tumor cells highly expressing PD-L120, 21, 22, 23. Whether avelumab (bavencio) could have better therapeutic effects compared to atezolizumab (tecentriq) in treating HCC post-ablation needs to be further studied.

In this paper, we aimed to explore the mechanism underlying the unsatisfactory effect of CRA and MWA in HCC treatment, and verify whether CRA or MWA was more suitable for the combined application with anti-PD-L1 antibodies in HCC mouse model. Our data revealed that CRA had more advantages than MWA in combining with ant-PD-L1 antibody to cure HCC. Combining with the PD-L1 blockade can greatly improve the immunosuppressive microenvironment after CRA, by enhancing the function of CTL/NK cells and reducing the number of CD11b+ immunosuppressive myeloid cells. More importantly, using the wild-type PD-L1 antibody, avelumab (bavencio), had more advantages compared to the mutant FC antibody in inducing NK cell-mediated ADCC effect, which target PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells in tumor microenvironment. Altogether, our study is the first to reveal the superior curative efficacy of CRA over MWA in combination with anti-PD-L1 antibody, and uncover the importance of wild-type anti-PD-L1 antibody in maintaining its function in inducing NK cell-mediated ADCC effect.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient samples

Tumor samples from 10 HCC patients treated by CRA, 10 HCC patients treated by MWA, and 10 HCC patients without any therapy were collected in The First Affiliated Hospital at Sun-yat sen University from 2018.01 to 2021.05. Tumor samples were collected by needle biopsies at 14 days after ablation therapies. Patients who took TKI or other therapies during this time were also excluded. The baseline imaging evaluation of HCC progress was performed and evaluation criterion referred to in the iRECIST Refining Guidelines. This study was conducted and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (2018[43]).

2.2. Cell lines

The mouse HCC cell line, H22, was purchased from iCell (iCell, iCell-m074, Shanghai, China) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Gibco, A4192101, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, 10100147C, CA, USA).

2.3. Mouse models and treatment

BALB/c mice were purchased from the Model Animal Research Center, Sun Yat-sen University. A density of 1 × 106 H22 cells was injected into male BALB/C mice on the right flank. The experimental treatments were initiated 12 days post-injection and the longest diameter of tumor was 0.5 cm.

The mice were then subjected to CRA or MWA. Two freezing cycles were used lasting 30–60 s. By the end of the first cycle, the tumor was visibly covered by an ice ball with frost on its surface. During both freezing cycles, the area around the tumor was rinsed with normal saline drip to prevent edge of tumor tissue from getting damaged. MWA was performed following the protocol of partial ablation described by Shi et al.7, with ablation parameters set as follows: ablation time 30–60 s, ablation power 10 w and temperature set to 60 °C. Skin burns were avoided as much as possible during the ablation process. Microwave ablation was terminated when local skin ulceration was found.

To treat the mice with antibodies, 10 mg/kg anti-mouse PD-L1 or anti-human PD-L1 were administered via intraperitoneal injection every 3 days after ablation therapy. Anti-mouse PD-L1 antibody were InVivoPlus anti-mouse PD-L1 (CD279) monoclonal antibody (BP0101, BioXcell, Lebanon, NH, USA), Anti-human PD-L1 antibodies included atezolizumab (also known as tecentriq) (AbMole, M6101, Houston, TX, USA), Durvalumab (also known as Imfinzi) (AstraZeneca, L01XC28, London, UK), and Avelumab (also known as Bavencio) (AbMole, M3813, Houston, TX, USA). For CXCL9 blocking assay, 10 mg/kg anti-mouse CXCL9 (BE0309, BioXcell, Lebanon, NH, USA) was administered via intraperitoneal injection every 3 days. For ADCC blocking assay, 10 mg/kg anti-mouse CD16 (BE0307, BioXcell, Lebanon, NH, USA) was administered via intraperitoneal injection every 3 days.

The tumor sizes (volume) were calculated every day using Eq. (1):

| Volume = 0.5 × L × W × H | (1) |

where L is the longer diameter, W is the shorter diameter, and H is the perpendicular dimension. The tumor weight at end point was tested. All experiment protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee Board for Human and Animal Experiments in Zhongshan School of Medicine of Sun Yat-sen University (ethics approval ID: SYSU-IACUC-2022-000335). The procedure was performed in accordance to the National Commission for the Protection of Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research guidelines for animal experiments. All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

2.4. Flow cytometric analysis

Single-cell suspensions were surface stained in fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer (phosphate buffer solution (PBS) supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) with the following antibodies for cell membrane staining and flow cytometric analysis: Zombie NIR Fixable Viability Kit (Biolegend, 423105, San Diego, CA, USA) for live/died cells staining, PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD45 (Biolegend, 157613, San Diego, CA, USA), Pacific Blue anti-mouse CD3 (Biolegend, 100213, San Diego, CA, USA), Alexa Fluor® 488 anti-mouse CD11b (ThermoFisher, 53-0112-82, Carlsbad, CA, USA), PerCP/Cy5.5 anti-mouse Gr-1 (Elabscience, E-AB-F1120J-50T, wuhan, China), APC anti-mouse F4/80 (Biolegend, 123116, San Diego, CA, USA), APC anti-mouse CD11c (Biolegend, 117309, San Diego, CA, USA), PE anti-mouse PD-L1 (Elabscience, E-AB-F1132D-200T, wuhan, China), PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse CD3 (Biolegend, 100218, San Diego, CA, USA), PE anti-mouse CD8a (Biolegend, 100708, San Diego, CA, USA), APC anti-mouse CD39 (Biolegend, 143809, San Diego, CA, USA), and FITC anti-mouse CD49b (Biolegend, 103503, San Diego, CA, USA). For intracellular staining, collected cells were fixed and permeabilized using BD Cytofix/Cytoperm Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (BD, 554714, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA) as recommended by the manufacturer. Pacific Blue anti-mouse IFN-γ (Biolegend, 505818, San Diego, CA, USA) and APC anti-mouse Granzyme B (Biolegend, 372203, San Diego, CA, USA) were used for intracellular staining.

For testing the affinity between PD-L1 antibodies and mouse CD16, atezolizumab (tecentriq), Avelumab (Bavencio), Mutant Anti-PD-L1-mIgG1e3 (InvivoGen, hpdl1-mab15, San Diego, CA, USA), Mouse IgG1 Isotype Control (R&D, MAB002, Emeryville, CA, USA), Human IgG1 (N298A) isotype control (InvivoGen, bgal-mab12, San Diego, CA, USA) were labeled with FITC fluorescence using the ZENON ALEXA FLUOR 488 MOUSE IG 1 KIT (ThermoFisher, Z25002, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as recommended by the manufacturer. FITC anti-mouse CD16 (101305, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA) was used as a positive control. Stained samples were visualized on a BD FACSAria and analyzed with FlowJo software (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Ashland, OR, USA).

2.5. Total RNA extraction and RNA-seq

Total RNA was extracted from tumor tissues, using a total RNA purification kit (NORGEN Biotek, NGB-17200, Thorold, ON, Canada), according to the manufacturer's instructions. An equivalent of 2 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the cDNA synthesis kit (Roche, 11117831001, basle, Swiss) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA-seq was performed by Kidio Biotechnology (Guangzhou, China), and the data was presented as the mean displayed in the center of the heatmaps. The fold-change was calculated and converted to log2.

2.6. Isolation of single cells from tumors, spleen and PBMC

The mouse spleens were ground into a cell suspension. Tumor tissues were cut up and digested with digesting solution (1 mg/mL collagenase II, 1 mg/mL collagenase IV, 300 μg/mL DNase I, and 0.01% HEPES in RPMI1640) at 37 °C for 1 h. The cell suspension was then filtered through a 40 μm cell strainer to remove the debris and cell clumps. The single cell suspension was washed and resuspended in PBS. Erythrocytes in the suspension were lysed with RBC lysis buffer (Sigma, R7757, St. Louis, MO, USA) and dead cells were removed using a Dead Cell Removal Kit (Miltenyi, 130-090-101, Cologne, Germany). The NK cells from the mouse spleen suspension were sorted by EasySep™ Mouse CD49b Positive Selection Kit (Stemcell, 18755, Vancouver, Canada); the CD11b+ and CD11c+ myeloid cells from the mouse tumors and spleens were sorted by EasySep™ Mouse CD11b Positive selection Kit (Stemcell, 18970, Vancouver, Canada) and EasySep™ Mouse CD11c Positive Selection Kit II (Stemcell, 18780, Vancouver, Canada). The mouse tumor cells were negatively sorted by EasySep™ Mouse CD45 Positive Selection Kit (Stemcell, 18945, Vancouver, Canada). The human myeloid cells from human tumors were sorted by EasySep™ Human CD33 Positive selection Kit(Stemcell, 17876, Vancouver, Canada). The human tumor cells were sorted by EasySep™ Human CD45 Depletion Kit II (Stemcell, 18259, Vancouver, Canada). Human Blood samples was collected from patients one day before operation and PBMCs were isolated via density gradient centrifugation. NK cells were sorted by EasySep™ Human CD56 Positive Selection Kit II (Stemcell, 17855, Vancouver, Canada) from the isolated PBMCs. All sorting protocols were performed following by the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay (ELISPOT)

For this assay, NK cells (105 cells) were mixed with target cells (tumor cells or myeloid cells) at effector-to-target (E:T) ratios of 2:1. This mix was then added to anti-IFN-γ pre-coated plates from the human IFN-γ ELISpot assay kit (DKW22-1000-096s; Dakewei, China), along with the following control groups: no antibody, isotype IgG1 control (MCE, HY-P9900, Newark, NJ, USA), and positive control (phytohemagglutinin stimulation). Plates were incubated for 24 h in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The ELISpot assays were then performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The plates were scanned with the S6 ultra immunoscan reader (Cellular Technology Ltd.) and the number of IFN-γ-positive T-cells was calculated using ImmunoSpot software (Version 5.1.34, Cellular Technology Ltd.).

2.8. Immunofluorescence staining

For immunofluorescence staining, the following antibodies were used: Alexa Fluor®594 Rabbit Anti-mouse CD8 alpha antibody (Abcam, ab277939, Cambridge, UK), goat anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody (R&D, AF-485-NA, Emeryville, CA, USA) and Alexa Fluor® 488 Donkey Anti-Goat IgG H&L (Abcam, ab150129, Cambridge, UK). Mouse CXCL9 was stained by Rabbit anti-Mouse FITC-CXCL9 Antibody (CUSABIO, P18340, Wuhan, China). Mouse CD11b was stained by rabbit Anti-mouse CD11b antibody (Abcam, ab184308, Cambridge, UK) and Alexa Fluor® 594 conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Abcam, ab150076, Cambridge, UK) as well as Alexa Fluor® 647 Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (Abcam, ab150075, Cambridge, UK). Mouse CCL2 was stained by Rat anti-mouse CCL2 antibody (Abcam, ab8101, Cambridge, UK) and Alexa Fluor® 488 Donkey Anti-Rat IgG H&L (Abcam, ab150153, Cambridge, UK). CD49b was stained by sheep anti-mouse CD49b antibody (R&D, AF1740-SP, Emeryville, CA, USA) and Alexa Fluor 488 Rabbit Anti-Sheep IgG H&L (Abcepta, ASP1212, Suzhou, China). Tunel was labeled using Tunel Assay Kit BrdU-Red (Abcam, ab66110, Cambridge, UK). DAPI (Thermo Fisher, D1306, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for the staining of the nucleus. Fluorescent signals were detected using the laser scanning confocal microscope (ZEISS LSM 800). To quantify immunofluorescence results, the images were further analyzed with Imaris software (Version 7.4, BITPLANE). The “Spot” function was used to locate and enumerate cells based on size and intensity threshold. Alternatively, the absolute numbers of cells spotted per mm2 in nine high-power fields of interested areas were also statistically analyzed (three separate fields from each mouse and three mice from each group).

2.9. Statistical analyses

Overall Survival curves were generated using Kaplan–Meier estimates and tested using the log-rank test. Data from animal experiments are expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean), and a P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was used for the comparing data from all groups. An ANOVA test was used for the comparing tumor growth curves. Data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism software.

3. Results

3.1. CRA induced higher tumoral PD-L1 expression but less infiltrated PD-L1highCD11b+ cells than MWA

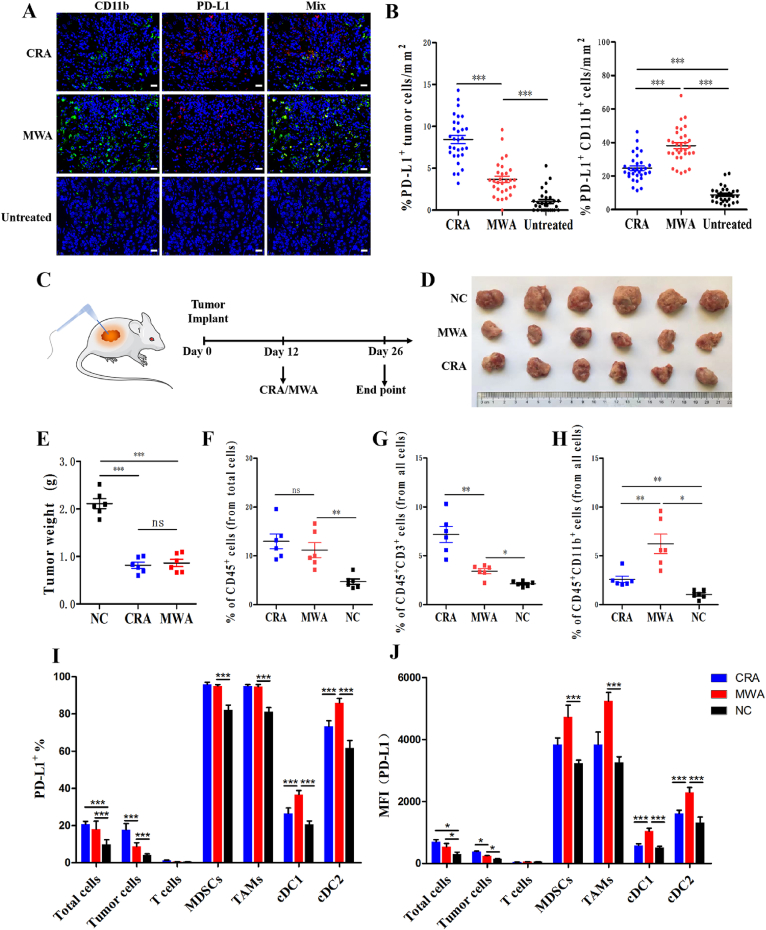

To explore the mechanism underlying the unsatisfactory outcome of CRA and MWA in HCC treatment, clinical samples were collected from HCC patients treated by CRA and MWA before and after therapy. We found that PD-L1+CD11b+ cells were significantly increased after ablation therapy, especially in MWA, while PD-L1+ tumor cells were significantly increased in CRA groups (Fig. 1A and B). To validate the clinical discovery and explore the underlying causes, BALB/c mice models were established by inoculating subcutaneously with H22 HCC cell lines and treating them with either CRA or MWA. All the ablation therapy were partial ablation to simulate real clinic, refering to the Methods section for details. Our data showed that there was no significant difference in tumor volume reduction between the CRA and MWA groups (Fig. 1C‒E). Flow cytometry analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells showed total number of immune cells were increased after CRA and MWA, but no difference between these two groups. In CRA groups, there were more T cells but less CD11b+ myeloid cells than MWA groups (Fig. 1F‒H). To further study the immunosuppressive ability of each cell subset, PD-L1 expression was tested. Flow cytometry gating strategy was shown in Supporting Information Fig. S1. Our results reveal that the expression level of PD-L1 was significantly higher on TAMs, MDSCs and classical dendritic type 2 cells (cDC2) than tumor cells, T cells and cDC1 cells (Fig. 1I). In CRA groups, both the total PD-L1 and tumoral PD-L1 expression level were higher than those in MWA groups. In contrast, MFI of PD-L1 was higher on myeloid cells in MWA than CRA groups (Fig. 1J).

Figure 1.

CRA induced higher tumoral PD-L1 expression but less infiltrated PD-L1highCD11b+ cells than MWA. Immunofluorescence staining of tumor biopsy specimens collected from CRA/MWA patients on Day 14 after ablation. Untreated samples were used as control group. PD-L1+ cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 594, CD11b+ cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488. Scale bar = 20 μm. Three separate fields from each patient and ten patients from each group were calculated. (B) The number of PD-L1+tumor cells and PD-L1+CD11b+ cells in every field of view of 1 mm2; Three separate fields from each patient and 10 patients for each group were calculated. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc tests. All data are mean ± SEM. (C–E) Schematic diagram of a complete animal experiment. H22 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into BALB/c mice. Twelve days later, cryoablation or microwave-ablation was performed. Two weeks later all mice were sacrificed (n = 6 for each group). Tumor weight at end points in all 3 groups were shown. (F–H) Quantification of frequency of CD45+, CD3+ T cells and CD11b+ myeloid cells in 3 groups were shown. (I, J) Relative quantification and MFI of PD-L1 expressed in different cell sub-populations in three groups were revealed. n = 6 for each group, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are means ± SEM.

Collectively, our results revealed how PD-L1 expressed on different cell subpopulations. The high expression level of PD-L1 and infiltration of immunosuppressive myeloid cells in tumor tissues were the main causes for the unsatisfactory outcome of CRA and MWA in HCC treatment. More importantly, the higher frequency of T cell infiltration, less PD-L1highCD11b+ cells, and up-regulated PD-L1 expression on tumor cells in CRA group suggest that CRA may have more underlying potential than MVA for anti-PD-L1 combination therapy.

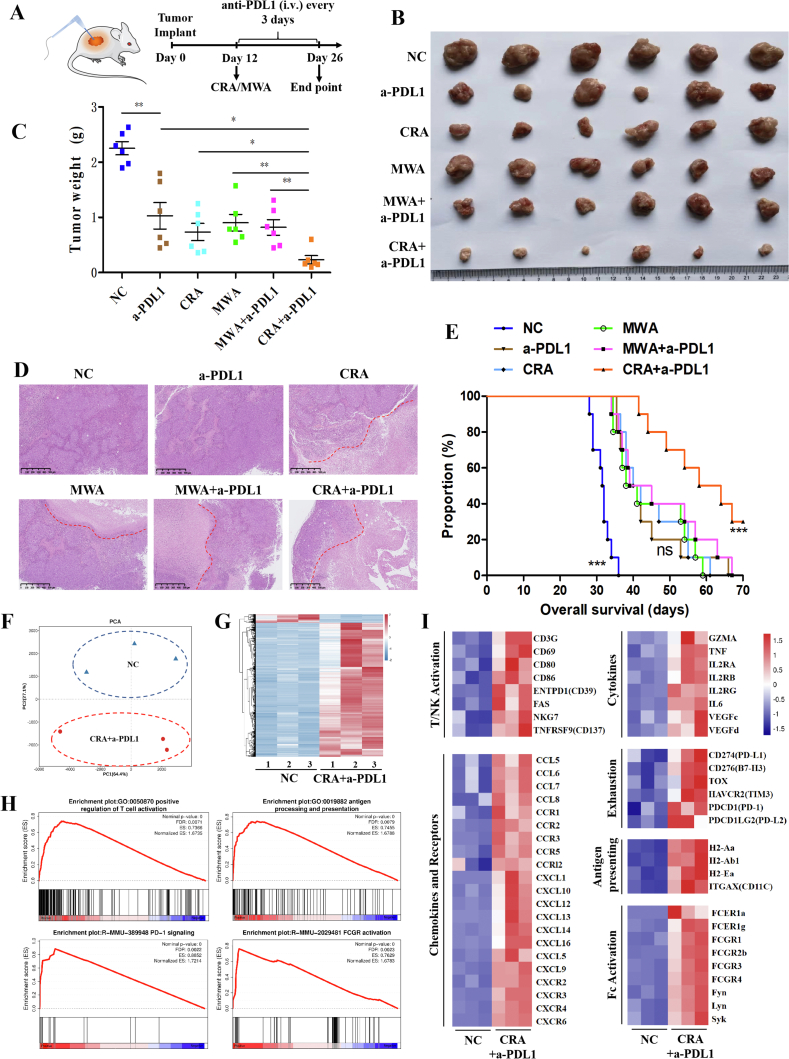

3.2. Anti-PD-L1 antibody combined with CRA showed a more excellent curative efficacy than combined with MWA in HCC mouse model

To validate the hypothesis above, anti-mouse PD-L1 antibody were used every 3 days after CRA and MWA ablation (Fig. 2A). After 14 days of treatments, the tumor volume of CRA plus anti-mouse PD-L1 (CRA+a-PDL1) was significantly reduced compared to other groups (Fig. 2B and C). H&E staining of tumor tissue sections revealed the largest area of necrosis and a minimal area of residual viable tumor in the CRA+a-PDL1 group (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the overall survival curves revealed that mice of CRA+a-PDL1 group had better prognosis than any other group (Fig. 2E). This data collectively suggested the combined application of anti-PD-L1 antibody improved the efficacy of CRA in HCC therapy.

Figure 2.

CRA had better curative effect than MWA in combining with anti-PD-L1 antibody therapy by inducing antitumor immune activity. (A) Schematic diagram of a complete animal experiment was shown. H22 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into BALB/c mice. 12 days later, cryoablation or microwave-ablation was proceeded, with anti-mouse PD-L1 antibody being infused via tail injection every 3 days, 10 mg/kg. Two weeks later all mice were sacrificed. (B, C) Tumor weight at end point in all 6 groups was shown. (n = 6 for each group, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are mean ± SEM). (D) The H&E staining of tumor tissue sections. Red lines represented the edge of live tumor zone and necrosis zone. (Scale bar = 500 μm). (E) Mouse model was constructed refering to the methods of Fig. 2A and overall survival of mice from 6 groups was revealed. (Survival curve was analyzed by log-rank test P > 0.05 was considered no significant difference). (F, G) Gene-expression analysis of CD45+ immune cells from CRA+anti-PD-L1 group and untreated group. PCA map and heatmap of the different expressed genes between two groups was shown. Blue color indicates down-regulated genes, and red color indicates up-regulated genes. (H) GSEA of immune response pathways in the transcriptome analysis, which presented as the normalized enrichment score (NES). (I) Heatmap of mean fold-change of genes in cytokines, chemokines, and so on. Red and blue colors indicate up-regulated or down-regulated genes, respectively.

To obtain a further understanding of the underlying mechanism responsible for the therapeutic effect of CRA+a-PDL1 treatments, RNA-seq analysis was performed. Fresh residual tumors were collected from CRA+a-PDL1 group and untreated control group and CD45+ cells was sorted for RNA-seq. The principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering heatmap revealed huge differences of gene signature between CRA+a-PDL1 and NC groups (Fig. 2F and G). Gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) found that genes in pathways associated with T cell activation, antigen presenting, PD-1 signaling, and Fc activation, were significantly up-regulated in CRA+a-PDL1 groups (Fig. 2H). Up-regulation of genes CD69, CD80, ENTPD1 (CD39), TNSRSF9 (CD137), and NKG7 and elevated levels of cytokines GZMA and TNF-α were observed in CRA+a-PDL1 groups, indicating the activation of CTLs and NK cells. Genes associated with antigen presenting cells, such as ITGAX (CD11c) and MHC-II, and chemokines of CXCL9 and CXCL10, were all up-regulated. The up-regulation of checkpoints such as PD-1, Tim-3, and PD-L1 revealed the potential negative feedback regulation of the antitumor immune response (Fig. 2I). Meanwhile, the top 20 enrichment pathways indicated that CRA combined with anti-PD-L1antibody elicited a complex anti-tumor immune response via multiple mechanisms, and ultimately attenuated immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment (Supporting Information Fig. S2). Interestingly, the Fc receptor was activated, suggesting the ADCC effect may be an important pathway for CRA+a-PDL1-mediated anti-tumor immune response, which needs further study.

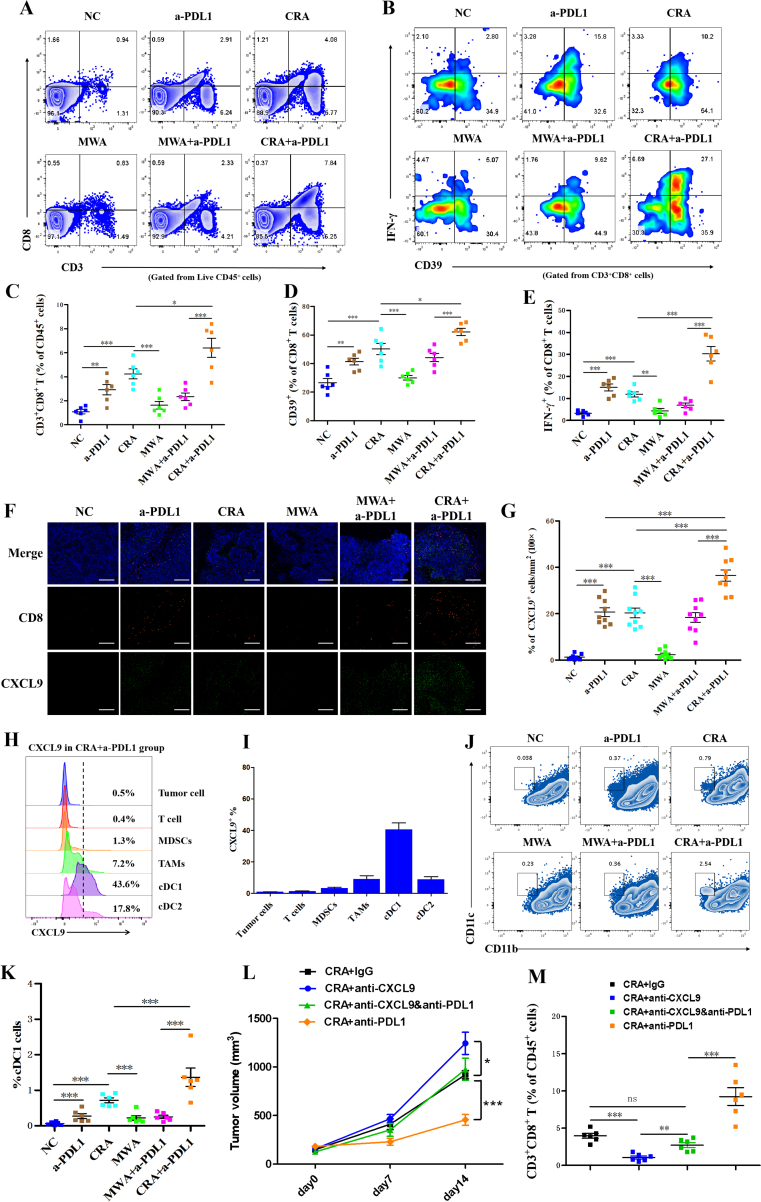

3.3. Combination of CRA and anti-PD-L1 antibody facilitated infiltration of CD8+ T cells by enhancing CXCL9 secretion of cDC1

To further investigate the underlying mechanism responsible for the better therapeutic effect of CRA+a-PDL1 treatments, the phenotype of CD8+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. We observed that the frequency of CD3+CD8+ T cells was significantly increased in the CRA+a-PDL1 group, with elevated expression of neoantigen-specific marker, CD3924, 25, 26 and increased secretion of IFN-γ, indicating a stronger antitumor activity (Fig. 3A‒E). To explore the underlying mechanism of the increased CD8+ T cells recruitment in CRA+a-PDL1 group, T cell recruitment-associated chemokine CXCL9 was analyzed. Immunofluorescence images revealed an increased production of CXLC9 after CRA+a-PDL1 therapy and an increased the recruitment of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3F and G, Supporting Information Fig. S3). Furthermore, we found that CXCL9 were mainly produced by CD11c+CD11b‒ cells, which was known as cDC1 cells (Fig. 3H‒I). In addition, Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the frequency of cDC1 cells were increased in CRA+a-PDL1 group (Fig. 3J and K). Finally, to verify the key role of CXCL9 in the recruitment of CD8+ T cells, the anti-CXCL9 antibody was given to mouse model. We found that the antitumor response in CRA+anti-CXCL9&anti-PD-L1 group were significantly weakened with less tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells infiltration than in CRA+anti-PD-L1 groups. The application of anti-CXCL9 significantly suppressed the curative efficacy of CRA+anti-PD-L1 in HCC mouse model (Fig. 3L and M). Altogether, our study demonstrated that anti-PD-L1 promoted the recruitment of CD8+ T cells after CRA by enhancing the CXCL9 secretion of cDC1.

Figure 3.

Anti-PD-L1 antibody enhanced infiltration of CD8+ T cells by increasing proportion of cDC1 cells that secrete CXCL9. (A, B) Flow cytometry plots of CD3+CD8+ T cells gated on CD45+ cells and CD39+IFN-γ+ gated on CD3+CD8+ cells in all 6 groups. (C–E) Relative quantification of CD3+CD8+ T cells gated on CD45+ cells and CD39+IFN-γ+ cells gated on CD3+CD8+ T cells. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of tumor tissue sections. CD8+ T cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 594, CXCL9 was stained with Alexa Fluor 488. Scale bar = 200 μm. (G) The percentages of CD8+ T cells and CXCL9+ spots in every field of view found in all different 6 groups; three separate fields from each mice and three mice from each group were calculated. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01,∗∗∗P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc tests. All data are means ± SEM. (H,I) Representative flow cytometry analysis of the frequency of CXCL9 gated from different cell types in tumor microenvironment. (J, K) Analysis of flow cytometric quantification of CD11c+CD11b− cDC1 cells gated on tumor infiltrating CD45+ cells. (L, M) H22 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into BALB/c mice. 12 days later, cryoablation or microwave-ablation was proceeded, with anti-mouse CXCL9 neutralizing antibody (10 mg/kg) or anti-mouse PD-L1 antibody (10 mg/kg) being infused via tail injection every 3 days. Anti-mouse IgG was used as negative control. Tumor volume and frequency of infiltrated CD8+ T cells were revealed. n = 6 for each groups, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are means ± SEM.

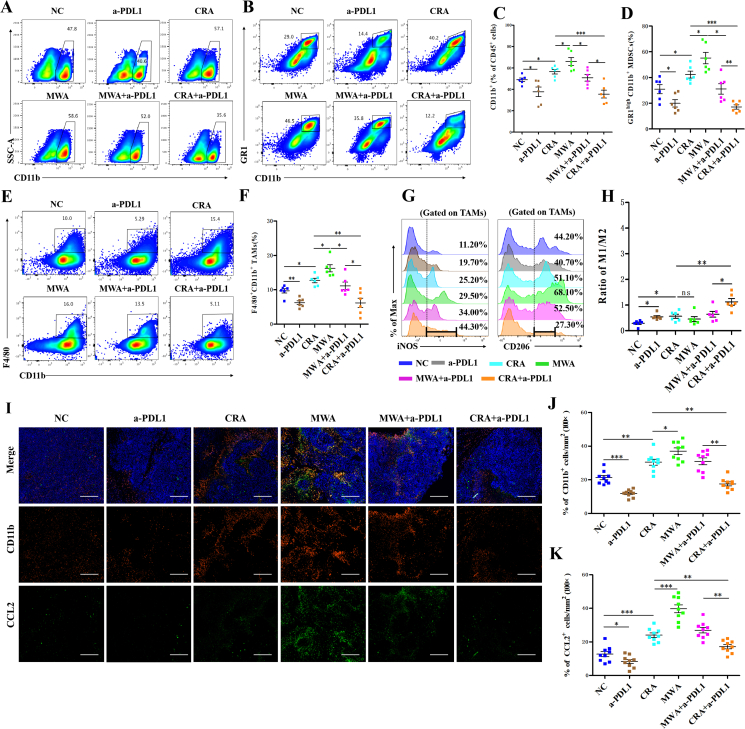

3.4. Combination of CRA and anti-PD-L1 antibody reduced the number of PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells by NK-mediated ADCC effect

Previous data has shown that the PD-L1highCD11b+ cells were significantly increased in both CRA and MWA groups. However, after the combined therapy of CRA+a-PDL1, the frequency of CD11b+ cells and MDSCs (GR1+CD11b+ cells) were significantly decreased (Fig. 4A‒D). Furthermore, the number of F4/80+ TAMs also decreased in CAR+a-PDL1 group (Fig. 4E and F). Moreover, we quantified the tumor inflammatory M1-like (CD11b+F4/80+iNOS+) and immunosuppressive M2-like (CD11b+F4/80+CD206+) macrophage subsets. The ratio of M1/M2 macrophages was significantly increased in the CRA+a-PDL1 group, indicating that the macrophages were further shifted to the proinflammatory M1-like phenotype rather than the anti-inflammatory M2-like phenotype after the combined application of anti-PD-L1 antibody (Fig. 4G and H). The immunofluorescence staining results revealed an increasing CD11b+ cells infiltration and CCL2 expression in both residual live tumors and necrotic areas after ablation therapy. The proportion of CD11b+ cells and expression of CCL2, however, were decreased with the usage of anti-PD-L1 antibodies (Fig. 4I‒K).

Figure 4.

Less CD11b+ myeloid cells infiltration was observed in CRA + anti-PD-L1 groups than in MWA + anti-PD-L1 groups. (A–F) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD11b+ (A), CD11b + GR1high (B), and CD11b+F4/80+ cells (E) gated on tumor infiltrating CD45+ cells in all groups. Flow cytometric quantification of CD11b+ (C), CD11b + GR1high (D), and CD11b+F4/80+ (F) in all groups. (G, H) Flow cytometric quantification of CD11b+F4/80+ (TAMs) population, and expression of iNOS and CD206 in CD11b+F4/80+ cell populations in all groups (n = 6 for each groups, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are means ± SEM). (I) Immunofluorescence staining of tumor tissue sections. CD11b+ cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 594, CCL2 was stained with Alexa Fluor 488. Scale bar = 200 μm. (J, K) The percentages of CD11b+ cells and the percentages of CCL2+ spots in every field of view found in all different 6 groups; Three separate fields from each mice and three mice from each group were calculated. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01,∗∗∗P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc tests. All data are means ± SEM.

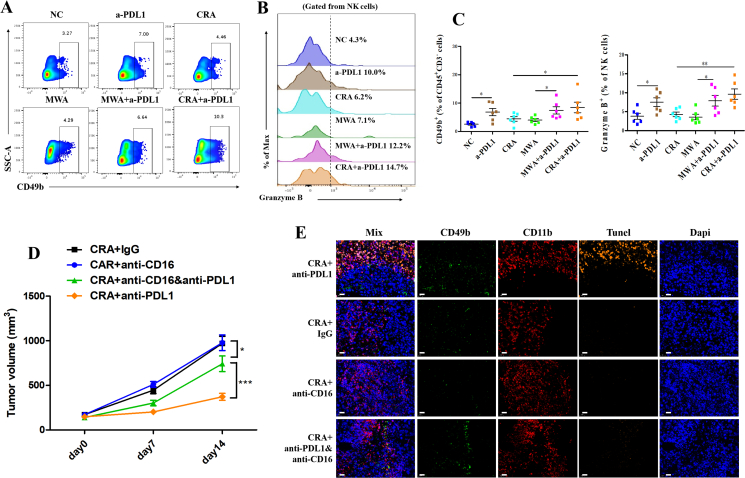

Previous data has shown the activation of Fc receptor in CRA+a-PDL1, suggesting that ADCC effect mediated by NK cells may be involved in eliminating CD11b+ myeloid cells after CRA+a-PDL1 therapy. Therefore, to further confirm this hypothesis, the function of NK cells was investigated. Our data showed an increasing infiltration and improved antitumor activity of CD49b+ NK cells in tumor microenvironment of a-PDL1 and CRA+a-PDL1 groups, compared to other groups (Fig. 5A‒C). Furthermore, to investigate whether the decrease of CD11b+ myeloid cells after CRA+a-PDL1 owe to the ADCC effect of NK cells, the ADCC-blocking antibody (anti-CD16 antibody) was given to the mouse model. Our data show that the addition of anti-CD16 antibody significantly diminished the therapeutic effect of CRA+anti-PDL1 combined therapy (Fig. 5D). Additionally, less NK cells and attenuated tunnel signal of CD11b+ myeloid cells were observed in CRA+anti-PDL1&anti-16 groups, compared to CRA+anti-PDL1 groups (Fig. 5E), suggesting that NK cells played an important role in reducing the number of CD11b+ myeloid cells via ADCC effect.

Figure 5.

Anti-PD-L1 antibody triggered NK cell-mediated ADCC effect to eliminating CD11b+ myeloid cells. (A, B) Representative flow cytometry plots of CD49b+ NK cells gated on CD45+ cells and granzyme B+ cells gated on NK cells in all groups. (C) Flow cytometric quantification of CD49b+ (NK) population, and expression of granzyme B+ populations in all groups. n = 6 for each group, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are mean ± SEM. (D) H22 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into BALB/c mice. Twelve days later, cryoablation or microwave-ablation was proceeded, with corresponding antibody being infused via tail injection every 3 days. ADCC blocking assay employed by anti-mouse CD16 neutralizing antibody. Anti-mouse IgG was used as negative control. Tumor volume was shown. n = 6 for each groups, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are mean ± SEM. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of tumor tissue sections. CD11b were stained with Alexa Fluor 647, CD49b was stained with Alexa Fluor 488, Tunel was stained by Alexa Fluor 594. Scale bar = 20 μm.

Collectively, this data verifies that the combination of CRA and anti-PD-L1 antibody reduced the number of PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells by NK-mediated ADCC effect, thus relieving the immunosuppressive microenvironment after ablation.

3.5. The wildtype anti-human PD-L1 antibody avelumab (bavencio) was better at eliminating PD-L1high CD11b+ cells by NK-mediated ADCC effect

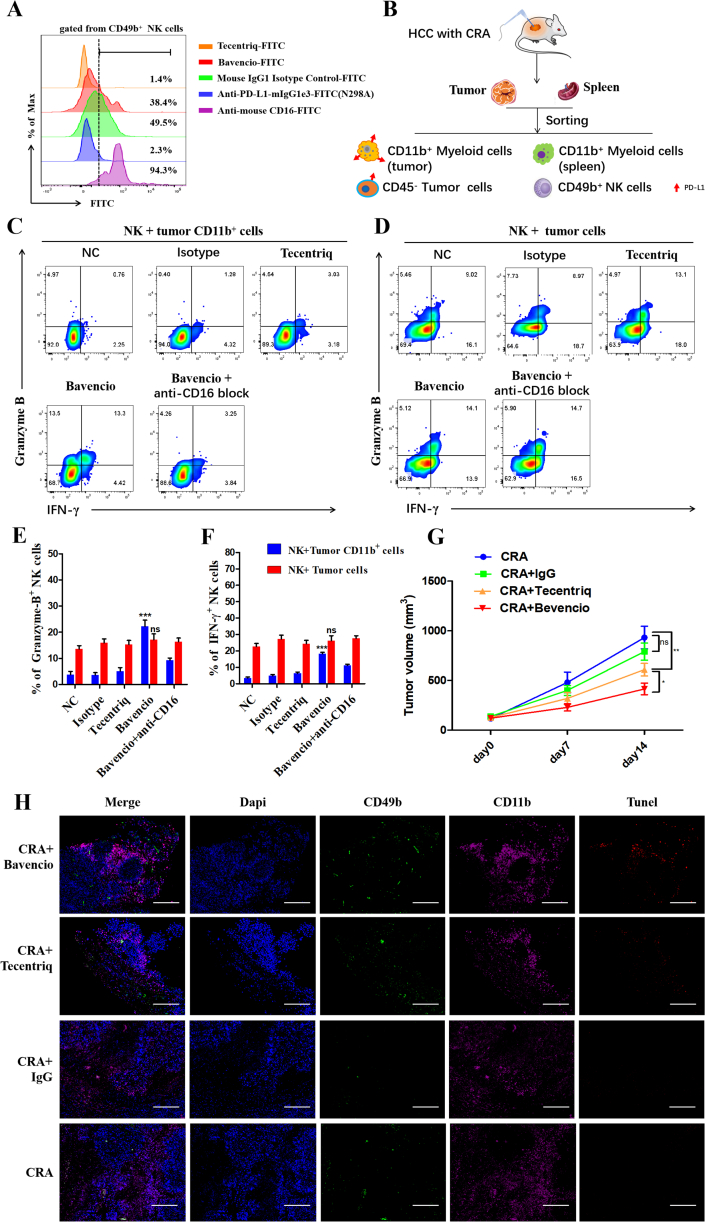

In clinic, the commonly used PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab (tecentriq) was engineered to have a point mutation in the Fc region N298A, which eliminates ADCC effect. Therefore, in our study, to improve the therapeutic effect, we included avelumab (bavencio), a PD-L1 antibody with a wild-type Fc region with ADCC effect. Firstly, we explored the affinity of the humanized Fc fragments of PD-L1 antibodies, bavencio and tecentriq, to murine NK cells. Murine antibody, anti-PD-L1-mIgG1e3 with N298A mutation and wild-type Mouse IgG1 Isotype, acted as controls for the experimental groups, while anti-mouse CD16 was the positive control. All antibodies were labeled with FITC fluorescence for analysis via flow cytometry. Bavencio was found to have stronger affinity to CD16 on mouse NK cells, compared to the other humanized and murine antibodies with mutation N298A. Murine WT antibodies and bavencio effectively coupled to NK cells (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Bavencio induces more PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells killing than Tecentriq via ADCC effect. (A) Flow cytometry revealed the affinity of different anti-PD-L1 antibodies with humanized Fc fragment or murine Fc fragment to CD16 molecule on mouse NK cells. (B) Residual tumor and autologous spleen were collected from HCC mouse models treated with CRA. Then CD11b+ myeloid cells from tumor or spleen were sorted, as well as tumor cells for target cells. NK cells were firstly incubated with antibodies for 30 mins for CD16 and Fc fragment conjunction, then cocultured with target cells with E:T ratio at 2:1 for 24 h in vitro. Golgi-stop (#554724, BD) was added at 1:1000 to stop cytokine secretion. (C, D) Flow cytometry analysis of effector molecules revealed the degree of ADCC effect activated by different antibodies. (E, F) Flow cytometric quantification of effector molecules gate on NK cells in all groups. n = 3 for each group, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are means ± SEM. (G) In vivo experiment of tumor-bearing mice treated with CRA combined with different antibodies. H22 cells were inoculated subcutaneously into BALB/c mice. Twelve days later, cryoablation or microwave-ablation was proceeded, with avelumab (bavencio) or atezolizumab (tecentriq) or human IgG1 being infused via tail injection every 3 days. Each antibody was injected at 10 mg/kg. Tumor volume was shown. n = 6 for each group, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are means ± SEM. (H) Immunofluorescence staining of tumor tissue sections. CD11b+ cells were stained with Alexa Flour 647, tunel was stained with Alexa Flour 594,CD49b was stained with Alexa Fluor 488 and nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar = 200 μm.

Next, from a tumor-bearing mouse model treated with CRA, we sorted CD11b+ myeloid cells, CD45- tumor cells, and NK cells via magnetic cell sorting (MACS). The NK cells were then co-cultured with target cells at an E:T ratio of 2:1 with antibodies in vitro (Fig. 6B). Only avelumab (bavencio) was able to induce the NK-mediated ADCC effect, indicated by the significant increase of cytotoxic cytokines, such as Granzyme B and IFN-γ. These cytokines release was hampered by anti-mouse CD16 antibodies. Interestingly, this phenomenon was very significant when tumor CD11b+ cells were used as target cells, but not tumor cells (Fig. 6C‒F). To exclude the influence of different Fab regions of PD-L1 antibodies, FITC-labeled avelumab (bavencio) and atezolizumab (tecentriq) were compared based on their affinity for CD11b+ cells and tumor cells. The FITC-labeled anti-mouse PD-L1 antibody was acted as a positive control. Results showed that there was no bias of the affinity of bavencio and tecentriq to PD-L1 molecules (Supporting Information Fig. S4). In vivo testing was then conducted to further verify whether the wild-type PD-L1 antibody avelumab (bavencio) was better than the mutated PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab (tecentriq) at inducing NK-mediated ADCC effect. Results show that the tumor volume was lower in the CRA+bavencio group compared to the CRA+tecentriq group (Fig. 6G). The immunofluorescence staining also showed that more NK cells and less myeloid cells were infiltrated under the treatment of anti-PD-L1 antibodies. Significantly, there was more tunnel fluorescence at the region of CD11b+ cells infiltration in the bavencio group, which indicates that the apoptosis of myeloid cells was induced by bavencio (Fig. 6H).

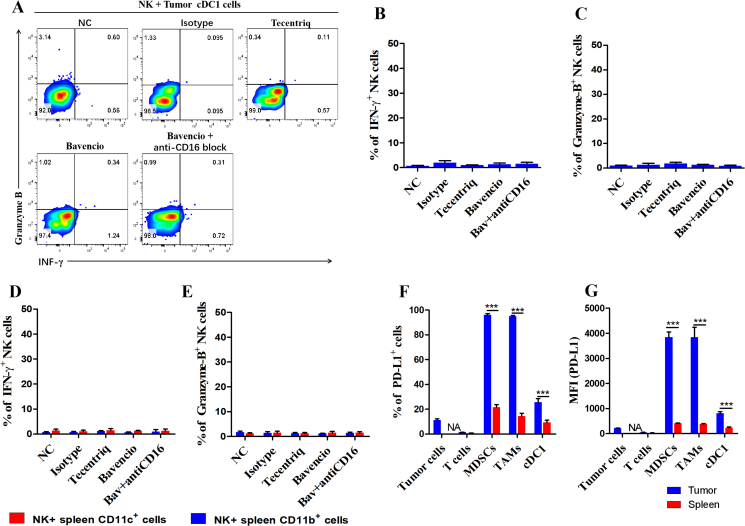

To verify whether bavencio-induced ADCC effect had negative consequences on tumor cDC1 cells and myeloid cells in peripheral circulation, CD11b+ cells from the spleens and CD11b−CD11C+ from tumors were separately sorted. Target cells were co-cultured with NK cells as previously described. Surprisingly, we found that none of the antibodies induced the ADCC effect to peripheral myeloid cells or tumor cDC1 cells (Fig. 7A‒E). To further explore the underlying mechanism of this result, we tested the PD-L1 expression of cell subsets from the spleen and tumor microenvironment. The expression of PD-L1 of myeloid cells in the spleen was significantly lower than those in the tumor microenvironment. The PD-L1 expression of cDC1 cells was also lower than CD11b+ cells in tumor (Fig. 7F and G). Therefore, these results suggest that the application of avelumab (bavencio) does not affect peripheral myeloid cells and antigen presenting cells in tumor the microenvironment, for their lower expression level of PD-L1 than PD-L1high CD11b+ cells.

Figure 7.

Bavencio did not induce ADCC effect to tumor cDC1 cells or spleen derived myeloid cells. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of effector molecules revealed the degree of ADCC effect induced by different antibodies. NK cells and tumor derived cDC1 cells were co-cultured at E:T = 2:1 for 24 h. Golgi-stop (#554724, BD) was added for suppressing cytokines release at 1:1000. (B, C) Flow cytometric quantification of effector molecules gate on NK cells cocultured with tumor cDC1 cells. (D, E) Flow cytometric quantification of effector molecules gate on NK cells cocultured with spleen derived myeloid cells. n = 3 for each group, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are means ± SEM. (F, G) Relative quantification and MFI of PD-L1 expressed in different cell subpopulations in tumor microenvironment or spleen were revealed. n = 3 for each group, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are mean ± SEM.

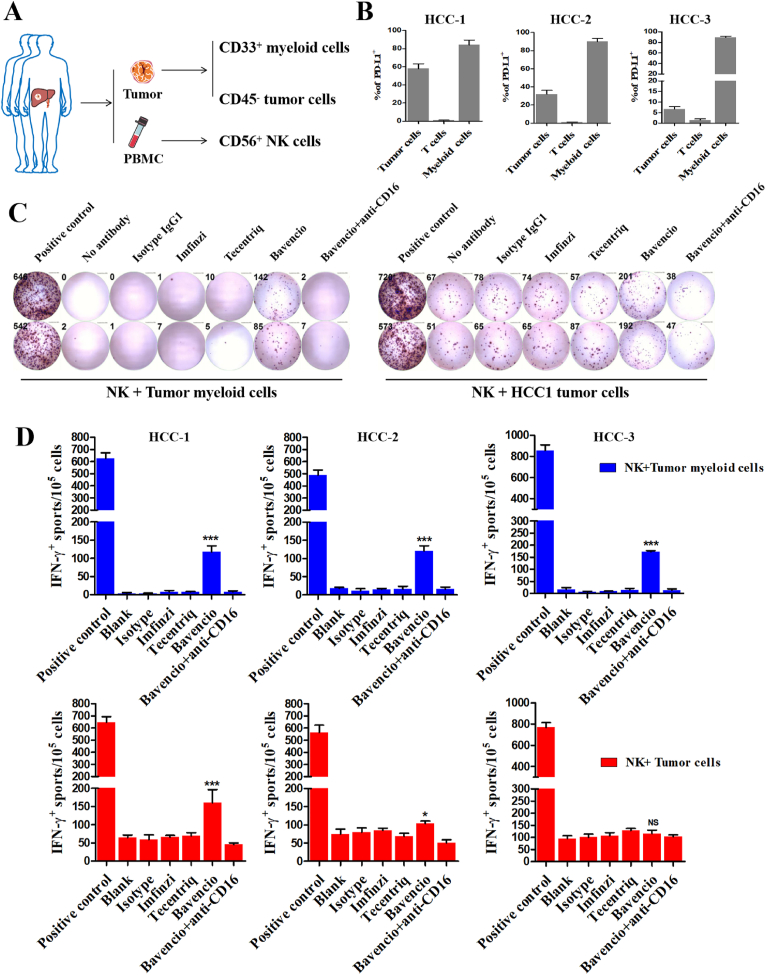

Finally, to confirm these results, human cells were isolated from three HCC patients. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and surgically resected fresh tumor tissues were collected. Peripheral CD56+ NK cells, CD33+ tumor infiltrating myeloid cells and CD45- tumor cells were sorted by MACS (Fig. 8A). The expression level of PD-L1 in all subsets of the tumor microenvironment were examined (Fig. 8B). An ELISPOT assay revealed that avelumab (bavencio) induced significant IFN-γ secretion in all three NK + myeloid groups and two NK + tumor groups (Fig. 8C and D), which was also based on level of PD-L1 expression on cells.

Figure 8.

Bavencio induced enhanced ADCC effect than mutant Fc antibodies in eliminating human HCC infiltrating PD-L1+ CD33b+ myeloid cells in vitro. (A) Surgically resected human HCC tumor and autologous PBMCs were collected from three individuals. Three different parts of each tumor was collected considering intratumoral heterogeneity. CD33+ myeloid cells and CD45- tumor cells from tumor were sorted as target cells, and CD56+ NK cells from PBMCs for effector cells. NK cells were co-cultured with target cells as previously described. (B) Quantification of flow cytometry revealed PD-L1 expressed on tumor cell, T cell and myeloid cells in tumor microenvironment for three patients. (C) Representative images for IFN-γ Elispot assay revealed the different antibodies induced ADCC effect. Target cells derived from one of the three part of tumor in HCC-1 candidate. PHA was regarded as positive control, no antibodies added and Isotype IgG1 was control group. (D) The number of IFN-γ spots/1 × 105 cells in each group. n = 3 for each patient, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ns, no significant difference, t-tests. All data are mean ± SEM.

In summary, all this data indicates that avelumab (bavencio) with a wild-type Fc region can induce a stronger NK-mediated ADCC effect to eliminate tumor-infiltrating PD-L1highCD11b+ cells and PD-L1high tumor cells.

4. Discussion

Increasing evidence has shown that immunotherapy, such as anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies, can enhance the local treatment of multiple cancers3,17,27. Recently, accumulating evidence has revealed that cryoablation (CRA) can trigger antitumor activity by releasing tumor antigens from frozen tumor cells and activating CTLs. However, CRA is limited in effectively treating HCC, compared to other thermal ablations, such as MWA and RFA2,10, 11, 12. Based on our clinical samples, we found PD-L1+CD11b+ cells were significantly increased, especially in MWA, whereas the number of PD-L1+ tumor cells were more increased in CRA than in MWA. Previous studies have also reported that RFA triggers local inflammation which leads to an increase in immunosuppressive CD11b+ myeloid cells infiltrating the tumor microenvironment, thereby hindering the therapeutic effects of immunotherapy post-ablation7,13. That is consistent with the results we reported. The infiltrated CD11b+ cells expressed higher levels of PD-L1 after CRA and MWA. Herein, we report that the combined therapy of CRA and anti-PD-L1 antibodies overcomes this obstacle and enhances HCC treatment by attenuating the PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells to promote antitumor activity of CTLs and NK cells.

Studies have shown that unresectable HCC patients treated with anti-PD-L1 antibody and anti-VEGF antibody had improved overall survival outcomes16,17. Researchers also found radiotherapy combined with anti-PD-L1 antibodies can reduce the number of CD11b+F4/80+ and tumor-infiltrating MDSC cells and increase CD8+ T cells so as to reshape tumor microenvironment and effectively reduce tumor burden28, 29, 30. Su et al.31 found that anti-PD-L1 treatment can inhibit immunosuppression of TAMs by AIM2-IL-1β axis. It was also proved that there was positive correlation between PD-L1 expression and myeloid cells in high-grade glioma and Hodgkin lymphoma32, 33, 34. Meanwhile, the cell number increase and function strengthening of CD8+ T cells and NK cells was also observed after anti-PD-L1 therapy35. In summary, the therapy of anti-PD-L1 antibodies to reduce PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells infiltration caused by ablation therapy was theoretically rational.

Surprisingly, our study found that the wild-type PD-L1 antibody, avelumab (bavencio), is better than the commonly used mutant PD-L1 antibody, atezolizumab (tecentriq) and durvalumab (Imfinzi) at eliminating PD-L1highCD11b+ myeloid cells in the tumor microenvironment by promoting NK-mediated ADCC. Normally, to prevent NK-mediated ADCC from targeting the patient's own immune cells, most clinical PD-L1 inhibitors like atezolizumab (tecentriq) contain a mutant Fc fragment N298A binding sites to weaken the inhibitor's affinity to CD16 molecules. However, recent studies have found that immune cells with antitumor activity, such as CTLs or NK cells, actually rarely express PD-L1. In contrast, PD-L1 is highly expressed on tumor-infiltrating CD11b+ myeloid cells in tumor microenvironment, including macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and cDC2 cells18,19. Researchers found tCAR-NK cells targeting PD-L1 can preferentially kill the myeloid-derived suppressor cell population and PD-L1 high tumor cell lines, but not other immune cell types, and the cytotoxicity of PD-L1-CAR-NK cells was correlated to the PD-L1 expression of the target cells36. Only avelumab (bavencio) utilizing the ADCC effect, has shown outstanding ability to eliminate PD-L1 expressing tumor cells20. Many studies have also verified bavencio's strong ADCC effect of killing PD-L1high tumor cells combined with NK cells. It is reported that avelumab-induced ADCC effect helps NK cells to kill non-Hodgkin lymphoma cells, meningiomas and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC)21, 22, 23,37. In our study, avelumab-induced ADCC showed significant cytotoxicity to tumor infiltrating CD11b+ myeloid cells expressing extremely high levels of PD-L1 in vitro and in vivo. More importantly, avelumab induced NK-mediated ADCC were not observed when co-cultured with cells expressing lower levels of PD-L1, such as splenic myeloid cells and cDC1 cells. This means that ADCC effect caused by avelumab is dependent on the PD-L1high target cells. It is found that the lack of any reduction induced by ADCC on multiple immune cell subsets from PBMCs, following multiple cycles of avelumab38, and only PD-L1high tumor cells can trigger avelumab-induced ADCC37. All of these evidences were in accordance with our study and to be an evidence of security in clinic.

To summarize, this study provides the rationale to further explore the improvement of HCC treatments by combining CRA with immunotherapy. Also, because avelumab can induce ADCC, it may be more effective at treating HCC.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, results from our study revealed that CRA had better curative effect combined with PD-L1 blockade than MWA in vivo. Mechanistically, anti-PD-L1 antibody promoted the infiltration of CD8+ T cells by increasing secretion of CXCL9 from cDC1 cells, and enhanced NK cells to eliminate PD-L1highCD11b+ cells by ADCC effect. Notably, wild-type PD-L1 avelumab (bavencio) was better at inducing ADCC effect to target PD-L1highCD11b+ cells than mutant PD-L1 atezolizumab (tecentriq). It provided a novel strategy for wild-type PD-L1 blockade combined with CRA for HCC treatment in clinic.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81971719, 82172036, and 82102169), the major scientific and technological project of Guangdong Province (No. 2020B0101130016, China), the major programme for tackling key problems of Guangzhou city (No. 202103000021, China). General project of China Postdoctoral Foundation (No. 2021M693646, China). Guangdong Province joint training postgraduate demonstration base project (No. 80000-18842217, China).

Author contributions

Jizhou Tan, Ting Liu, and Wenzhe Fan wrote the manuscript. Jizhou Tan, Ting Liu, and Wenzhe Fan designed the research. Jizhou Tan, Ting Liu and Wenzhe Fan carried out the experiments and performed data analysis. Jialiang Wei, Bowen Zhu, Yafang Liu, Lingwei Liu, Xiaokai Zhang, Songling Chen participated part of the experiments. Bowen Zhu, Jialiang Wei and Haibiao Lin collected clinical samples and data. Yuanqing Zhang and Jiaping Li supervised the project. Jizhou Tan, Ting Liu and Wenzhe Fan revised the manuscript. All of the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.08.006.

Contributor Information

Yuanqing Zhang, Email: zhangyq65@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Jiaping Li, Email: lijiap@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1450–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1713263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei J.L., Cui W., Fan W.Z., Wang Y., Li J.P. Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: transcatheter arterial chemoembolization combined with microwave ablation vs. combined with cryoablation. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1285. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato T., Iwasaki T., Uemura M., Nagahara A., Higashihara H., Osuga K., et al. Characterization of the cryoablation-induced immune response in kidney cancer patients. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6 doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1326441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katzman D., Wu S., Sterman D.H. Immunological aspects of cryoablation of non-small cell lung cancer: a comprehensive review. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:624–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansen M.C., Hillegersberg R.V., Schoots I.G., Levi M., Beek J.F., Crezee H., et al. Cryoablation induces greater inflammatory and coagulative responses than radiofrequency ablation or laser induced thermotherapy in a rat liver model. Surgery. 2010;147:686–695. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng Z., Shi F., Zhou L., Zhang M.N., Chen Y., Chang X.J., et al. Upregulation of circulating PD-L1/PD-1 is associated with poor post-cryoablation prognosis in patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023621. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi L.R., Chen L.J., Wu C.P., Zhu Y.B., Xu B., Zheng X., et al. PD-1 blockade boosts radiofrequency ablation-elicited adaptive immune responses against tumor. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:1173–1184. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McArthur H.L., Diab A., Page D.B., Yuan J.D., Solomon S.B., Sacchini V., et al. A pilot study of preoperative single-dose Ipilimumab and/or cryoablation in women with early-stage breast cancer with comprehensive immune profiling. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:5729–5737. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waitz R., Solomon S.B., Petre E.N., Trumble A.E., Fassò M., Norton L., et al. Potent induction of tumor immunity by combining tumor cryoablation with anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Cancer Res. 2012;72:430–439. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta P., Maralakunte M., Kumar P., Chandel K., Chaluvashetty S.B., Bhujade H., et al. Overall survival and local recurrence following RFA, MWA, and cryoablation of very early and early HCC: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:5400–5408. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07610-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L., Ren Y.Q., Sun T., Cao Y.Y., Yan L.L., Zhang W.H., et al. The efficacy of radiofrequency ablation versus cryoablation in the treatment of single hepatocellular carcinoma: a population-based study. Cancer Med. 2021;10:3715–3725. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cha S.Y., Kang T.W., Min J.H., Song K.D., Lee M.W., Rhim H., et al. RF ablation versus cryoablation for small perivascular hepatocellular carcinoma: propensity score analyses of mid-term outcomes. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;43:434–444. doi: 10.1007/s00270-019-02394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi L.R., Wang J.J., Ding N.H., Zhang Y., Zhu Y.B., Dong S.L., et al. Inflammation induced by incomplete radiofrequency ablation accelerates tumor progression and hinders PD-1 immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2019;10:5421. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13204-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng S.J., Li Z.Y., Gao R.R., Xing B.C., Gao Y.N., Yang Y., et al. A pan-cancer single-cell transcriptional atlas of tumor infiltrating myeloid cells. Cell. 2021;184:792–809. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finn R.S., Qin S.K., Ikeda M., Galle P.R., Ducreux M., Kim T.Y., et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee M.S., Ryoo B.Y., Hsu C.H., Numata K., Stein S., Verret W., et al. Atezolizumab with or without bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (GO30140): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:808–820. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30156-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdo J., Cornell D.L., Mittal S.K., Agrawal D.K. Immunotherapy plus cryotherapy: potential augmented abscopal effect for advanced cancers. Front Oncol. 2018;8:85. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen L.T., Ohashi P.S. Clinical blockade of PD1 and LAG3—potential mechanisms of action. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:45–56. doi: 10.1038/nri3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng Q., Qiu X., Zhang Z., Zhang S., Zhang Y., Liang Y., Guo J., et al. PD-L1 on dendritic cells attenuates T cell activation and regulates response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4835. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18570-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyerinas Benjamin, Jochems Caroline, Fantini Massimo, et al. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity of a novel anti-PD-L1 antibody avelumab (MSB0010718C) on human tumor cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:1148–1157. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jochems C., Tritsch S.R., Pellom S.T., Su Z., Soon-Shiong P., Wong H.C., et al. ADCC employing an NK cell line (haNK) expressing the high affinity CD16 allele with avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 antibody. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:583–593. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juliá E.P., Amante A., María Betina Pampena M.B., Mordoh J., Levy E.M., et al. Avelumab, an IgG1 anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, triggers NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity and cytokine production against triple negative breast cancer cells. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2140. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giles A.J., Hao S.Y., Padget M., Song H., Zhang W., Lynes J., et al. Efficient ADCC killing of meningioma by avelumab and a high-affinity natural killer cell line, haNK. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.130688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simoni Y., Becht E., Fehlings M., Loh C.Y., Koo S.L., Teng K.W.W., et al. Bystander CD8+ T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature. 2018;557:575–579. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu T., Tan J.Z., Wu M.H., Fan W.Z., Wei J.L., Zhu B.W., et al. High-affinity neoantigens correlate with better prognosis and trigger potent antihepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) activity by activating CD39+ CD8+ T cells. Gut. 2021;70:1965–1977. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou F., Tan J.Z., Liu T., Liu B.F., Tang Y.P., Zhang H., et al. The CD39+ HBV surface protein-targeted CAR-T and personalized tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells exhibit potent anti-HCC activity. Mol Ther. 2021;29:1794–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Machlenkin A., Goldberger O., Tirosh B., Paz A., Volovitz I., Bar-Haim E., et al. Combined dendritic cell cryotherapy of tumor induces systemic antimetastatic immunity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4955–4961. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu J.L., Green M.D., Li S.S., Sun Y.L., Journey S.N., Choi J.E., et al. Liver metastasis restrains immunotherapy efficacy via macrophage-mediated T cell elimination. Nat Med. 2021;27:152–164. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1131-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng L., Liang H., Burnette B., Beckett M., Darga T., Weichselbaum R.R., et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:687–695. doi: 10.1172/JCI67313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gong X., Li X., Jiang T., Xie H., Zhu Z., Zhou F., et al. Combined radiotherapy and anti-PD-L1 antibody synergistically enhances antitumor effect in non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su S., Zhao J., Xing Y., Zhang X., Liu J., Ouyang Q., et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition overcomes ADCP induced immunosuppression by macrophages. Cell. 2018;175:442–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lai Y.S., Wahyuningtyas R., Aui S.P., Chang K.T. Autocrine VEGF signalling on M2 macrophages regulates PD-L1 expression for immunomodulation of T cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:1257–1267. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue S., Hu M., Li P., Ma J., Xie L., Teng F., et al. Relationship between expression of PD-L1 and tumor angiogenesis, proliferation, and invasion in glioma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:49702–49712. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh Y.W., Han J.H., Yoon D.H., Suh C., Huh J., et al. PD-L1 expression correlates with VEGF and microvessel density in patients with uniformly treated classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:1883–1890. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-3115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallin J.J., Bendell J.C., Funke R., Sznol M., Korski K., Jones S., et al. Atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab enhances antigen-specific T-cell migration in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fabian K.P., Padget M.R., Donahue R.N., et al. PD-L1 targeting high-affinity NK (t-haNK) cells induce direct antitumor effects and target suppressive MDSC populations. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park J.E., Kim S.E., Keam B., Park H.R., Kim S., Kim M., et al. Anti-tumor effects of NK cells and antiPD-L1 antibody with antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in PD-L1-positive cancer cell lines. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donahue R.N., Lepone L.M., Grenga I., Jochems C., Fantini M., Madan R.A., et al. Analyses of the peripheral immunome following multiple administrations of avelumab, a human IgG1 anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:20. doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0220-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.