Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the leading causes of cancer-related death globally and liver transplantation (LT) can serve as the best curative treatment option. However, HCC recurrence after LT remains the major obstacle to the long-term survival of recipients. Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized the treatment of many cancers and provided a new treatment strategy for post-LT HCC recurrence. Evidence has been accumulated with the real-world application of ICIs in patients with post-LT HCC recurrence. Notably, the use of these agents as immunity boosters in recipients treated with immunosuppressors is still controversial. In this review, we summarized the immunotherapy for post-LT HCC recurrence and conducted an efficacy and safety evaluation based on the current experience of ICIs for post-LT HCC recurrence. In addition, we further discussed the potential mechanism of ICIs and immunosuppressive agents in regulating the balance between immune immunosuppression and lasting anti-tumor immunity.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplantation, immune checkpoint inhibitor, immunosuppression, transplant tolerance

Introduction

With almost 906,000 new cases and 830,000 deaths in 2020, liver cancer has become the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide (1). Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer, accounting for over 75% of cases (2, 3). Nowadays, liver transplantation (LT) for early-stage HCC has become a standard treatment and accounts for nearly 40% of all liver transplantations performed at most centers worldwide (4). Although the prognosis of HCC patients was markedly improved after LT due to the advances in surgical techniques and immunosuppressive agents, HCC recurrence remains the major obstacle to long-term survival.

In the past decades, numerous risk factors have been identified for HCC recurrence, including the pre-transplant alpha-fetoprotein levels, tumor number and size, etc. Therefore, some criteria, such as Milan criteria (5), University of California San Francisco criteria (6) and Hangzhou criteria (7), were advocated to select candidates who might benefit from LT. These strict criteria can minimize the risks, while the HCC recurrence rate after LT is still relatively high, approximately 10% to 30% (4). Several studies reported that the post-LT immunosuppressive environment could be the key hazard factor for HCC recurrence (8, 9), as it could promote tumor escape and cancer cell proliferation by suppressing the proliferation, differentiation and effector functions of T cells (10).

Post-LT HCC recurrence progressed with a predominant pattern of extra-hepatic metastases, including lung, bone and abdominal lymph nodes (4). For the treatment of these tumors, surgical interventions, such as resection (11), trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) (12) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) (13), are meaningful when the nodule is oligo-metastatic and local. For those unresectable nodules, systemic therapy has attracted great attention. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as sorafenib and lenvatinib, which are the first-line treatment strategies for advanced HCC, have been applied in recipients with HCC recurrence and proved to be of significant value (14). Sorafenib and lenvatinib can significantly prolong the survival of post-LT patients, and their safety and efficiency have been already evaluated (15, 16). In a meta-analysis, Li Z et al. (15) reviewed 23 studies and concluded that recipients treated with sorafenib for post-LT HCC recurrence had a median survival of 12.8 months and a pooled 1-year survival of 56.8%, better than that observed in patients with the best supportive care. In addition, Chen YY et al. (16) investigated the efficacy of lenvatinib and found a disease control rate of 70%. They also confirmed a comparable efficacy in both LT and non-LT patients in clinical practice. Moreover, several studies have reported the real-world application of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in these patients. Different from primary HCC, these relapsed tumors have a higher immune evasion characteristic due to the accumulation of inhibitory cytokines and molecules (17). Single-cell RNA sequencing further revealed that the activation of T cells in recurrent HCC was significantly inhibited by the up-regulation of immune checkpoints (17), suggesting that ICIs-based immunotherapy was promising for the treatment of recurrent HCC in LT recipients. Additionally, patients with recurrent HCC usually have no other way but to try to use the ICIs, due to distant metastasis and TKIs-resistance (18). Notably, while ICIs activate the anti-tumor immunity, they also put grafts in danger of rejection, resulting in limited use thus far. In this review, we appraise the current understanding of the immunotherapy for post-LT HCC recurrence with special attention to the efficacy and safety evaluation based on the current experience of ICIs. We also discussed the potential mechanism underlying the role of ICIs in altering the balance between cancer immunology and transplant tolerance.

The status of immunosuppressive agents after LT

Currently, various immunosuppressive medications are used in recipients after LT, including steroids, anti-metabolites, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors and calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) (10). Immunosuppressive agents have resulted in decreased incidence of acute rejection and to prolong graft survival of LT recipients, but also cause adverse events (19). CNIs, such as cyclosporine A (CsA) and tacrolimus (TAC), are the cornerstone of immunosuppressive regimens with profound significance in preventing graft rejection. Both TAC and CsA can inhibit the Ca2+/Calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) pathway, reduce the secretion of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and contribute to long-term allograft survival (10). However, studies in human cohorts reported that overexposure to TAC and CsA increased the risk of post-LT HCC recurrence (20, 21). Furthermore, both in vitro and in vivo studies showed that CNIs could enhance the expression of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and promote the proliferation of cancer cells (22, 23).

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is an anti-metabolite purine antagonist and its application in LT began in the late 1990s (24). Given the lack of nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity, MMF has been used in CNI- or steroid- sparing regimens. However, it remains controversial whether MMF will increase the risk of HCC recurrence after LT. With clinically achievable concentrations, Chen et al. (25) demonstrated that MPA, the active ingredient of MMF, could effectively inhibit cancer cell proliferation and the growth of liver tumor organoids. In addition, authors also found that the use of MMF in LT recipients was significantly associated with less tumor recurrence and improved patient survival. Notably, the result was reported with low precision due to the small sample size (44 LT patients identified as HCC-related LT were included). While a cohort study in Taiwan showed the opposite conclusion, demonstrating that high-dose MMF notably promoted HCC recurrence and reduced the overall survival of recipients after LT (26). Additionally, as a popular immunosuppressive agent, steroids have been reported to induce the proliferation of cancer cells and increase the risk of HCC recurrence (27). Our previous study demonstrated that recipients with steroids-free immunosuppressive protocol had reduced post-LT HCC recurrence as compared to those with steroids in a human cohort (28).

Nowadays, mTOR inhibitors (rapamycin), such as sirolimus and everolimus, have been reported to be anti-recurrence/metastasis and improve the prognosis of patients who underwent LT for HCC (29). Using mTOR inhibitors as an anti-rejection strategy has been accompanied by numerous studies, and the properties of mTOR complex have been emphasized. By targeting complex 1, the rapamycin could inhibit the thymic T cells proliferation and differentiation (30). Interestingly, considerable evidence showed that TOR inhibitors could not only prevent allograft rejection (30) but also represent potent anti-cancer effects by directly targeting the cancer cells (31). In a prospective, randomized, open-label, multicenter trial, Geissler EK et al. (32) enrolled 525 patients who underwent LT for HCC and found that broad-based practical incorporation of sirolimus into an immunosuppressive regime could improve outcome in the first 3 to 5 years after LT, while the outcome advantage is eventually lost after 5 years. Subsequently, Schnitzbauer et al. (33) performed a multivariate analysis based on the above trial data and concluded that those patients treated with sirolimus ≥ 3 months had better outcomes, especially in the group with higher alpha-fetoprotein levels. On the other hand, the everolimus-based regimen was also proved to be effective in patients with post-LT HCC recurrence. Patients who had high serum trough levels of everolimus (more than 5 ng/ml) had better survival compared to those treated with less than 5 ng/ml (34). In addition, early introduction of everolimus with reduced-CNIs is also associated with a significant renal benefit compared with CNsI-based immunosuppressive regime (35).

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

The discovery and clinical implementation of ICI has achieved remarkable clinical outcomes and revolutionized the treatment of cancer, as recognized by the 2018 Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology (36). There are three main classes of ICIs approved by FDA for clinical application, the inhibitors of programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4). Despite the promising results with immunotherapy in HCC, the safety of using ICIs for post-LT HCC recurrence remains disputed. Different from immunotherapy for primary HCC, post-LT ICIs treatment must be undertaken with caution due to the risk of allograft rejection or graft loss. Here we include all published 27 cases of LTs with ICI treatment for post-LT HCC recurrence ( Table 1 ). The median patient age was 49.4 (range: 14-70) years and 81.5% were males. The median time from LT to ICIs was 2.7 years. The immunotherapy regimens included PD-1 inhibitors (16 nivolumab, 4 toripalimab, 2 pembrolizumab, 1 camrelizumab), PD-L1 inhibitors (2 atezolizumab), CTLA-4 inhibitor (1 ipilimumab) and combination therapy (1 nivolumab followed by atezolizumab). There were 8 (29.6%) patients with disease control, which was defined by stable disease (SD, n=3), partial response (PR, n=1) and complete response (CR, n=4). Ten (37.0%) patients were found to be progressive disease (PD). Of note, graft rejection was reported in 6 out of 27 patients (22.2%), a much higher rate than in patients without ICIs treatment (53), and all of them were treated with nivolumab. To further evaluate the safety of ICIs in recipients, we next reviewed the records of using ICIs in patients with de novo malignancies after LT ( Table 2 ). The median age of these patients was 59.4 (range: 35-72) years and 78.57% were males. Melanoma was the main indication for ICIs therapy (n=7), which is followed by lung cancer (n=2). The median time from LT in this setting was longer than that in those with HCC recurrence (7.3 years versus 2.7 years). Among the liver recipients with de novo malignancies, 2 patients achieved CR, 4 patients with PR and 4 patients with PD. The graft rejection rate in this group was 21.4%, similar to that in the post-LT HCC recurrence setting.

Table 1.

Case reports with the application of ICIs in HCC recurrence patients after LT.

| No. | Age | Gender | Malignancy | TFTI | Treatment before ICIs |

ICIs | Dose | Duration | IS therapy before ICIs |

IS therapy during ICIs |

Rejection | Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | M | HCC | 1 yrs | TACE/MWA | Nivolumab | 3 mg/kg/2 wks | 15 cycles | TAC | TAC | NO | PD | (37) |

| 2 | 20 | M | HCC | 4 yrs | Sorafenib/Capecitabine | Nivolumab | – | 2 cycles | Sirolimus | Sirolimus | AMR/TCMR | - | (38) |

| 3 | 14 | M | HCC | 3 yrs | Gemcitabine/Oxaliplatin | Nivolumab | – | 1 cycle | TAC | TAC | AMR/TCMR | - | (38) |

| 4 | 70 | M | HCC | 8 yrs | Sorafenib/Capecitabine/ External bean radiation |

Pembrolizumab | 3 mg/kg/2 wks | 3 mths | TAC | TAC | NO | PD | (39) |

| 5 | 56 | M | HCC | 5.5 yrs | Sorafenib | Nivolumab | – | – | TAC | – | NO | CR | (40) |

| 6 | 55 | M | HCC | 1.8 yrs | Sorafenib | Nivolumab | – | – | Sirolimus/MMF | – | NO | PD | (40) |

| 7 | 34 | F | HCC | 3.7 yrs | Sorafenib | Nivolumab | – | – | TAC | – | NO | PD | (40) |

| 8 | 63 | M | HCC | 1.2 yrs | Sorafenib | Nivolumab | – | – | TAC | – | NO | - | (40) |

| 9 | 68 | M | HCC | 1.1 yrs | Sorafenib | Nivolumab | – | – | Sirolimus | – | YES | - | (40) |

| 10 | 53 | F | HCC | 3 yrs | Sorafenib | Nivolumab | 200 mg/2 wks | 1 cycle | Prednisone/MMF/Everolimus | Everolimus/ MMF |

TCMR | - | (41) |

| 11 | 61 | M | HCC | 2 yrs | Sorafenib | Nivolumab | – | 1 mth | – | – | TCMR | - | (42) |

| 12 | 57 | M | HCC | 3 yrs | Sorafenib | Pembrolizumab | 200 mg/3 wks | 10 mths | TAC/MMF /Steroid |

TAC/Sirolimus | NO | CR | (43) |

| 13 | 64 | M | HCC | 2 yrs | Sorafenib | Nivolumab | – | 0.25 mths | – | – | TCMR | - | (44) |

| 14 | 70 | M | HCC | 3 yrs | Sorafenib/Gemcitabine/Oxaliplatin | Nivolumab | 240 mg/2 wks | 4 cycles | TAC | TAC | NO | PD | (45) |

| 15 | 62 | F | HCC | 2 yrs | Sorafenib/Regorafenib/5Fluorouracil/Oxaliplatin | Nivolumab | 240 mg/2 wks | 5 cycles | TAC | TAC | NO | SD | (45) |

| 16 | 66 | M | HCC | 2 yrs | Sorafenib/Regorafenib Gemcitabine/Oxaliplatin |

Nivolumab | – | 6 cycles | TAC | TAC | NO | PD | (45) |

| 17 | 62 | F | HCC | 2 yrs | TACE | Nivolumab | – | 16 mths | TAC/MMF | – | NO | CR | (46) |

| 18 | 54 | F | HCC | 7 yrs | Sorafenib/Nanoknife /Ethanol ablation |

Ipilimumab | 3 mg/kg/3 wks | 13 mths | Everolimus/TAC | Everolimus /TAC |

NO | PR | (47) |

| 19 | 54 | M | HCC | 4 yrs | Sorafenib/RFA /Lenvatinib |

Camrelizumab | 200 mg/3 wks | 5 cycles | TAC | Sirolimus | NO | CR | (48) |

| 20 | 54 | M | HCC | 2 yrs | Sorafenib/mFolfox-6/ Gemcitabine/TACE |

Nivolumab | 200 mg/2 wks | 12 cycles | TAC | TAC | NO | PD | (49) |

| 21 | 46 | M | HCC | 1 yrs | Sorafenib/Lenvatinib | Toripalimab | 240 mg/3 wks | 6 cycles | Sirolimus | Sirolimus | NO | PD | (50) |

| 22 | 46 | M | HCC | 1 yrs | TACE/PEI/Resection /Sorafenib/Lenvatinib |

Toripalimab | 240 mg/3 wks | 2 cycles | Sirolimus | Sirolimus | NO | SD | (50) |

| 23 | 62 | M | HCC | 1 yrs | Sorafenib/Lenvatinib /TACE/PEI |

Toripalimab | 240 mg/3 wks | – | Sirolimus | Sirolimus | NO | - | (50) |

| 24 | 66 | M | HCC | 1 yrs | Sorafenib/Lenvatinib /Regorafenib |

Toripalimab | 240 mg/3 wks | – | Sirolimus | Sirolimus | NO | - | (50) |

| 25 | 35 | M | HCC | 4 yrs | Surgical/Gemcitabine/Oxaliplatin/Fluorouracil/ IFN alfa-2b |

Atezolizumab | – | 6 mths | – | – | NO | PD | (51) |

| 26 | 53 | M | HCC | – | Sorafenib/Resection/ External radiotherapy |

Nivolizumab/Atezolizumab | – | 7 cycles | – | – | NO | SD | (52) |

| 27 | 55 | M | HCC | 1 yrs | Ablation/TACE/ External radiotherapy |

Atezolizumab | 2 cycles | – | – | NO | PD | (52) |

TFTI, time from transplant to ICIs; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IS, immunosuppressive; Ref, references; M, male; F, female; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; MWA, microwave ablation; TAC, tacrolimus; AMR, antibody-mediated rejection; TCMR, T cell–mediated rejection; IFN, interferon; PEI, percutaneous ethanol injection; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; PD, progressive disease; CR, complete response; SD, stable disease; PR, partial response.

Table 2.

Case reports with the application of ICIs in de novo malignancy after LT.

| No. | Age | Gender | Reasons for LT | Malignancy After LT |

TFTI | ICIs | Dose | Duration | IS therapy before ICIs |

IS therapy during ICIs |

Rejection | Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | M | HCC | Melanoma | 8 yrs | Ipilimumab | – | 3 mths | Sirolimus | Sirolimus | NO | PR | (54) |

| 2 | 59 | F | Cirrhosis | Melanoma | 8 yrs | Ipilimumab | – | 3 mths | Tacrolimus | Tacrolimus | NO | PD | (55) |

| 3 | 67 | F | LMFM | Melanoma | 1.5 yrs | Ipilimumab | 3mg/kg | 0.75 mths | Sirolimus/MMF | – | YES | PD | (56) |

| 4 | 35 | M | Biliary atresia | Melanoma | 20 yrs | Pembrolizumab | – | 2 cycles | MMF/Steroid | Steroid | NO | CR | (57) |

| 5 | 54 | M | Cirrhosis | NSCLC | 13 yrs | Nivolumab | 3mg/kg | 3 cycles | Tacrolimus/Everolimus/Prednisone | Tacrolimus/Everolimus/Prednisone | NO | PD | (58) |

| 6 | 57 | M | HCC | Melanoma | 5.5 yrs | Pembrolizumab | – | – | MMF/Everolimus | – | NO | CR | (40) |

| 7 | 63 | M | CC | Melanoma | 3.1 yrs | Pembrolizumab | – | – | MMF/Prednisone | – | YES | – | (40) |

| 8 | 62 | F | HCC | MPNST-like melanoma | 6 yrs | Ipilimumab/Pembrolizumab | – | 4 cycles/ 25 cycles |

Prednisone/Tacrolimus | Prednisone | NO | PR | (59) |

| 9 | 61 | M | Cirrhosis | Colon adenocarcinoma | 3 yrs | Pembrolizumab | 200 mg/3 wks | 15 cycles | Tacrolimus/MMF/ Prednisone |

Tacrolimus | NO | PR | (60) |

| 10 | 66 | M | Cryptogenic liver disease. | Lung adenocarcinoma | 3 yrs | Nivolumab | 3 mg/kg | 0.5M | – | – | YES | – | (61) |

| 11 | 58 | M | PSC-related liver disease | Cutaneous scc | 21 yrs | Nivolumab/ Cemiplimab |

240 mg/2 wks; 350 mg/3 wks |

15M/2 cycles | Tacrolimus/Prednisone | Tacrolimus/Prednisone/MMF | NO | PR | (62) |

| 12 | 52 | M | Alcoholic liver injuries | Hypopharyngeal cancer | 2.7 yrs | Nivolumab | 240mg/2 wks | 4 cycles | Cyclosporine/MMF | Cyclosporine/MMF | NO | – | (63) |

| 13 | 72 | M | – | MCC | 7 yrs | Nivolumab | 3mg/kg/2 wks | 2 cycles | MMF/Budesonide | MMF/Budesonide | NO | – | (64) |

| 14 | 59 | M | ICC | Recurrent ICC | 1 yrs | Toripalimab | 240 mg/3 wks | 7 cycles | Sirolimus | Sirolimus | NO | PD | (50) |

LT, liver transplantation; TFTI, time from transplant to ICIs; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; IS, immunosuppressive; Ref, references; M, male; F, female; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; TFTI, time from transplant to ICIs; CC, cholangio carcinoma; LMFM, liver metastases from melanoma; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; MCC,merkel cell carcinoma; PD, progressive disease; CR, complete response; PR, partial response.

Several factors may be related to the risk of acute rejection after ICIs treatment based on the current data. First, we observed the rejection rate was lower in anti-PD-L1 group (0/2) than that in anti-PD-1 (8/32) and anti-CTLA-4 (1/4) groups. However, due to the limited cases, the current evidence is not certain to conclude that anti-PD-L1 therapy is relatively safe for post-LT HCC recurrence. Second, a longer interval from LT to initial ICIs treatment and a lower dose of ICIs might be related to a lower incidence of rejection. We found that patients without graft rejection after ICIs treatment have a longer interval from LT to drug exposure (4.65 yr vs. 2.52 yr), which is consistent with the previous studies (65). In addition, a series of cases demonstrated that patients receiving liver grafts with a high level of PD-L1 were prone to develop graft rejection after ICIs therapies (65, 66). Given that, Shi et al. (50) designed a pilot study to evaluate the rejection risk in liver grafts with different PD-L1 expressions. Among 5 recipients who suffered HCC recurrence and were treated with anti-PD-1 therapy (toripalimab), 4 with PD-L1-negative graft did not have rejection, while the other with PD-L1-positive graft developed rejection (50), suggesting that pathological assessment of the graft’s PD-L1 status may serve as a selection criterion to decrease the risk of graft rejection before ICIs treatment. Herein, we summarized the efficiency and side effects based on the existing data in the Table 3 . More well-designed preclinical and clinical studies with a large sample are required to determine the fundamental mechanisms of acute rejection after ICIs treatment.

Table 3.

The efficiency and side effects of each drug based on the existing data.

| Drugs | efficiency | side effects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR’s | The graft rejection rate in those treated with sirolimus is 22.2% (2/9). | Not mentioned. | |

| The graft rejection rate in those treated with everolimus is 50.0% (1/2). | |||

| TKI’s | 81.5% (22/27) patients use TKI’s and most of them change to ICI’s due to disease progression. | Proteinuria (44); Nausea, Emesis (41) | |

| ICI’s | PD-1 inhibitors | 28.5% (4/14) patients with disease control. | Graft rejection; Abnormal liver function (38) |

| PD-L1 inhibitors | 0% (0/2) patients with disease control. | ||

| CTLA-4 inhibitors | 100% (1/1) patients with disease control. | ||

| combination therapy (PD-1 inhibitors +PD-L1 inhibitors) | 100% (1/1) patients with disease control. | ||

mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; TKI, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitors; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4.

The potential mechanism of immune checkpoint inhibitors in altering immune microenvironment and interplaying with immunosuppressive agents

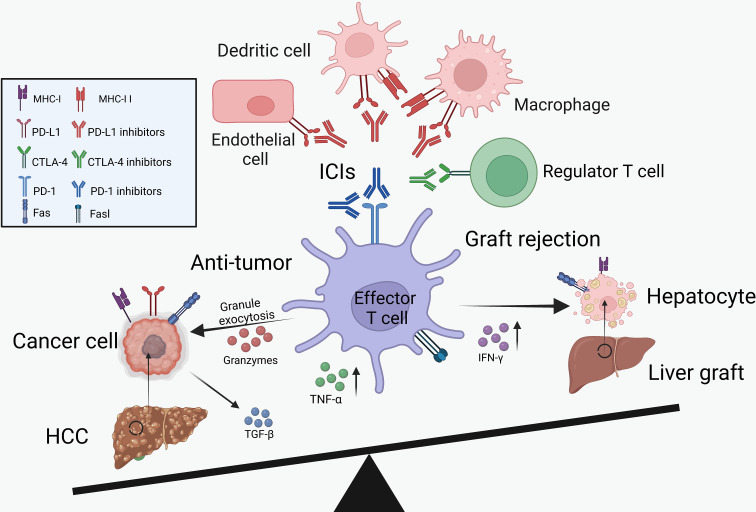

As described above, ICIs showed clinical benefits for the treatment of HCC recurrence but increased the risk of transplant rejection ( Figure 1 ). Therefore, we summarized the potential mechanisms of PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors in boosting the anti-tumor immunity and inducing transplant rejection.

Figure 1.

The balance between cancer immunology and transplant tolerance. Through the activation of effector T cells, the ICIs can not only reduce tumor burden but also increase the risk of graft rejection. IL-2, interleukin-2; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

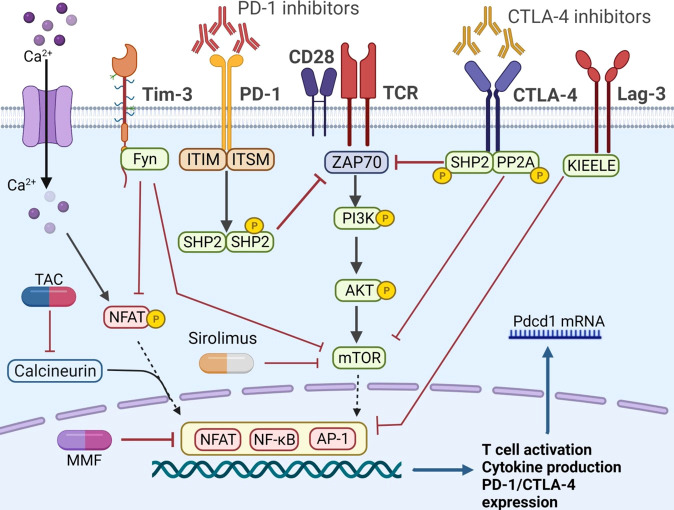

Physiologically, the non-parenchymal cells in liver graft, including regulatory T cells (Tregs), macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), played vital roles in promoting a tolerogenic microenvironment (67). These cells could secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., PGE2, IL-10 and TGF-β) and induce the death of cytotoxic T cells through the increased expression of immune checkpoints, such as PD-1 and CTLA-4 (67). Specifically, with these immune checkpoint molecules phosphorylated, the downstream co-stimulatory pathways would be inhibited in various immune cells, dampening the immune response (68–70).

PD-1 is mainly expressed on T cells and acts as a negative regulator of T-cell activation through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/MEK/ERK pathway (69). It was reported that blocking the PD-1 pathway could reduce the apoptosis of CD8+ T cells and increase the granzyme B expression by enhancing the mTOR signaling, further activating the immune system (71). Moreover, the administration of PD-1 inhibitors could up-regulate the proliferation marker Ki67, enhance the expression of the transcription factor T-bet and the secretion of IFN-γ of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (72). Those cytotoxic CD8+ T cells could not only eliminate the cancer cells but also lead to acute graft rejection (73, 74). In the absence of PD-1 expression, the cytotoxic CD8+ T cells would differentiate into an effector memory phenotype, further prolong the interaction with CD11c+ cells and cause harm to transplant tolerance significantly (75).

Apart from effector T cells, the regulatory T cells (Tregs) could mediate immune response in the pro-inflammatory microenvironments and maintain tolerance in organ transplant models (76). Differently, the immune checkpoint signaling played a controversial role in regulating Treg induction and maintenance. Up to now, several studies have reported that blockade of the CTLA-4 pathway (such as the downstream signaling molecule PP2A) could activate the mTOR signaling (77) and decrease formation of Tregs (78). However, some studies got opposite results and found that inhibition of either PD-1 or CTLA-4 contributes to the proliferation of Tregs and increase the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines (79, 80). We summarize the effect of ICI’s on Tregs based on current studies in Table 4 , and there certainly need more exhaustive studies to figure out the exact role of immune checkpoints in Tregs.

Table 4.

The effect of each ICI on each cell type.

| Cells | ICIs | Models | Function | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCs | PD-L1 inhibitors | MC38 colon cancer model | Activating DC function to enhance T cells killing effect. | (81) |

| Increasing the number of activated (IFN-γ+) CD8+ T cells and reactivating tumor-infiltrating T cells. | (82) | |||

| Inflammatory skin reaction | Inhibiting DCs migration from the skin to draining lymph node. | (83) | ||

| Macrophage | PD-1 inhibitors | MC38 colon cancer mode | Enhancing the capacity for phagocytosis. | (84) |

| PD-L1 inhibitors | B16 melanoma model | Upregulating mTOR pathway activity and promoting proliferation and survival. | (85) | |

| MC38 colon cancer model | Inducing T cell activation (more IFN-γ production and higher CD 69 expression). | (81) | ||

| Tregs | PD-1 inhibitors | Gastric cancer model | promoting the proliferation and immunosuppressive function. | (80) |

| Osteosarcoma model | Decreasing the percentage of Tregs in CD4+ T cells. | (86) | ||

| CTLA-4 inhibitors | Glycolysis-low tumor model | Enhancing the function of glucose-uptake and IFN-γ production. | (87) | |

| MC38 colon cancer models | Reducing the number of intra-tumoral Tregs. | (88) |

Tregs, regulatory T cells; DCs, dendritic cells, PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4; IFN-γ, interferon-γ.

As the ligands of PD-1, PD-L1 is frequently observed in macrophages, DCs, parenchyma cells as well as cancer cells and was found to induce graft tolerance (89). For instance, PD-L1 expressed on the anti-inflammatory phenotype macrophages (M2) was proved to be related to preventing chronic allograft rejection after LT (67). Specifically, these M2 macrophages could increase the number of Foxp3+ Tregs in the liver grafts, contributing to tolerance induction and further prolonging the survival time of recipients (90). Graft-infiltrating DCs, another potent antigen-presenting cell with high PD-L1 expression, have also been shown to contribute to the maintenance of graft tolerance (91). These cells could induce the CD8+ T cells exhaustion, subvert anti-donor T cell immune responses and increase the percentage of Tregs (91). However, blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 interaction by targeting PD-L1 would aggravate the cytotoxic damage caused by CD8+ T cells and enhance the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-2, INF-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (91). Recently, studies based on the heart and intestinal transplantation models further reported that the blockade or absence of PD-L1 expression on endothelial cells would also result in acute graft rejection by increasing the CD8+ T cells infiltration (92, 93).

We speculate that there could be the following possible reasons. Firstly, PD-L1 is mainly expressed on antigen-presenting cells (including macrophages and DCs) and tumor cells, therefore, PD-L1 antibodies always target these cells, unlike PD-1 antibodies, which directly target T cells to completely block T cell exhaustion. However, macrophages and DCs could also inhibit the activation of T cells by expressing other immune checkpoints, such as TIM-3 and LAG-3 (94, 95). Secondly, the preservation of PD-L2 (another ligand of PD-1) after PD-L1 inhibitor treatment, could partially activate the PD-1 pathway and suppress the immune response, which was proved to be associated with a lower incidence of immune-related adverse events (96). The PD-1 inhibitors could entirely block the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1/PD-L2, which may lead to T cell over-activation and a higher rejection rate.

To reduce the risk of graft rejection, the combination therapy of ICIs and immunosuppressive agents was proposed, which has attracted great attention recently. Herein, Figure 2 demonstrated the known pathways that control the activation of immune cells and the crosstalk between ICIs and immunosuppressive agents. Recent study revealed that anti PD-1 therapy could activate CD8+ T cells through PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and then induces colitis in melanoma patients. Blockade of the pathway with sirolimus not only inhibit tumor growth, but also suppresses the T cell infiltration in colitic lesions, showing a promising strategy for balancing immune overactivation and effective anti-tumor immunity (97). In a kidney transplant case, Esfahani et al. (98) reported that ICI-induced kidney allograft rejection was also associated with cytotoxic CD8+ T cell activation in the periphery, a subset of cells with a well-established role in renal allograft rejection on anti-PD-1 therapy (99). After combination with sirolimus, T cell activation and proliferation was reduced, although IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells persisted in circulation. These results further suggested that ICIs and mTOR inhibitors combination therapy promoted a state of functional tolerance without a loss of immune-mediated anti-tumor activity. However, to our knowledge, there are no clinical trials assessing the combination of ICIs and mTOR inhibitors in HCC recurrence after LT. In addition, the protocol of combination therapy still in question. For example, did immunosuppressants need to adjust when combined with ICIs? What is the optimal level of immunosuppressants compared to those without HCC recurrence?

Figure 2.

The co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory pathways in T cells. The PD-1 axis could phosphorylate ITIM and ITSM, recruit SHP1 and SHP2, and further inhibit ZAP 70. Similarly, CTLA-4 pathway recruited SHP2 and PP2A, and attenuated the mTOR signaling. Fyn is another motif on the cytoplasmic tail of Tim-3, promoting the inhibitory function by inhibiting the NFAT and mTOR activity. The unique KIEELE motif is essential for the inhibitory function of Lag-3. When implemented with ICIs, the co-inhibitory pathway is inhibited and T cell is activated. Immunosuppressive agents, such as CNIs and mTOR inhibitors, can obstruct T cell activation by different mechanisms. PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; ITIM, immune-receptor tyrosine based inhibitory motif; ITSM, immune-receptor tyrosine based switch motif; ZAP 70, zeta-chain-associated protein kinase 70; SHP, src homology 2 domain- containing protein tyrosine phosphatase; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T cells; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; Tim-3, T cell immunoglobulin-3; Lag-3, lymphocyte activation gene-3; TIGIT, T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain; TAC, tacrolimus.

Conclusion and future expectations

In this review, we summarized the existing research on the immunotherapy of post-LT HCC recurrence and discussed the experience of using ICIs in this setting. We believed that it’s better to adopt a steroids-free and mTOR-based regimen in patients with post-LT HCC recurrence instead of the CNIs. Compared to CsA and TAC, sirolimus and everolimus showed a promising role in anti-tumor with mild side effects. Additionally, based on the available data and cases mentioned above, we recommend that physicians should consider cautiously before the application of ICIs. The risks and benefits of ICIs-based immunotherapy must be fully assessed individually, depending on the circumstances of each patient. There are several factors should be taken into account to minimize the risks of graft rejection. Firstly, before the ICIs treatment, negative PD-L1 expression in liver biopsy and increased length of time from LT may contribute to lowering the risk of rejection. Secondly, compared to PD-1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors, PD-L1 therapy is a promising strategy to reduce the risk of graft rejection in post-LT HCC recurrence. Thirdly, the combination protocol (ICIs plus mTOR inhibitors) is a potential strategy to balance cancer immunology and graft tolerance. Moreover, close monitoring of immune status is mandatory during the ICIs therapies, such as the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the serum of IFN-γ, which were already proved to be helpful for the prediction of graft rejection in kidney and lung transplantation. Finally, once the acute graft rejection occurred, treatments such as ICIs withdrawal, high high-dose steroids and thymoglobulin should be taken immediately to improve patients’ outcomes. Further studies about the mechanism of the crosstalk of ICIs and immunosuppressive agents are necessary to improve the therapeutic effect for post-LT HCC recurrence.

Author contributions

QL and JJ participated in research design. JJ, HH, and RC participated in the writing of the paper. JJ and YL participated in data analysis. JJ, HH, and QL participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82171757 and 82011530442), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (No. LZ22H030004).

Abbreviations

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CNIs, calcineurin inhibitors; CR, complete response; CsA, cyclosporine A; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; ICIs, immune checkpoint inhibitors; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL-2, interleukin-2; irAEs, immune-related adverse events; LT, liver transplantation; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPA, mycophenolic acid; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; PD, progressive disease; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand 1; PR, partial response; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; SD, stable disease; TAC, tacrolimus; TACE, trans-arterial chemoembolization; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors; Tregs, regulatory T cells; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin (2021) 71(3):209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: Trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2019) 16(10):589–604. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0186-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2021) 7(1):6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sapisochin G, Bruix J. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Outcomes and novel surgical approaches. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2017) 14(4):203–17. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. New Engl J Med (1996) 334(11):693–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. (2001) 33(6):1394–403. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zheng SS, Xu X, Wu J, Chen J, Wang WL, Zhang M, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Hangzhou experiences. Transplantation. (2008) 85(12):1726–32. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816b67e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vivarelli M, Dazzi A, Zanello M, Cucchetti A, Cescon M, Ravaioli M, et al. Effect of different immunosuppressive schedules on recurrence-free survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplantation. (2010) 89(2):227–31. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181c3c540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mehta N, Bhangui P, Yao FY, Mazzaferro V, Toso C, Akamatsu N, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. working group report from the ILTS transplant oncology consensus conference. Transplantation. (2020) 104(6):1136–42. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pallet N, Fernandez-Ramos AA, Loriot MA. Impact of immunosuppressive drugs on the metabolism of T cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol (2018) 341:169–200. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fernandez-Sevilla E, Allard MA, Selten J, Golse N, Vibert E, Sa Cunha A, et al. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: Is there a place for resection? Liver Transpl (2017) 23(4):440–7. doi: 10.1002/lt.24742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ko HK, Ko GY, Yoon HK, Sung KB. Tumor response to transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after living donor liver transplantation. Korean J Radiol (2007) 8(4):320–7. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2007.8.4.320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang J, Yan L, Wu H, Yang J, Liao M, Zeng Y. Is radiofrequency ablation applicable for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation? J Surg Res (2016) 200(1):122–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sposito C, Mariani L, Germini A, Flores Reyes M, Bongini M, Grossi G, et al. Comparative efficacy of sorafenib versus best supportive care in recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: a case-control study. J Hepatol (2013) 59(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li Z, Gao J, Zheng S, Wang Y, Xiang X, Cheng Q, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Turk J Gastroenterol (2021) 32(1):30–41. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2020.19877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen YY, Chen CL, Lin CC, Wang CC, Liu YW, Li WF, et al. Efficacy and safety of lenvatinib in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with liver transplantation: A case-control study. Cancers (Basel) (2021) 13(18):4584. doi: 10.3390/cancers13184584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sun Y, Wu L, Zhong Y, Zhou K, Hou Y, Wang Z, et al. Single-cell landscape of the ecosystem in early-relapse hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell. (2021) 184(2):404–21.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sangro B, Sarobe P, Hervas-Stubbs S, Melero I. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2021) 18(8):525–43. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00438-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodríguez-Perálvarez M, de la Mata M, Burroughs AK. Liver transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplantation. (2014) 19(3):253–60. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vivarelli M, Cucchetti A, La Barba G, Ravaioli M, Del Gaudio M, Lauro A, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma under calcineurin inhibitors: reassessment of risk factors for tumor recurrence. Ann Surg (2008) 248(5):857–62. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181896278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rodriguez-Peralvarez M, Tsochatzis E, Naveas MC, Pieri G, Garcia-Caparros C, O'Beirne J, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors early after liver transplantation prevents recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol (2013) 59(6):1193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hojo M, Morimoto T, Maluccio M, Asano T, Morimoto K, Lagman M, et al. Cyclosporine induces cancer progression by a cell-autonomous mechanism. Nature. (1999) 397(6719):530–4. doi: 10.1038/17401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maluccio M, Sharma V, Lagman M, Vyas S, Yang H, Li B, et al. Tacrolimus enhances transforming growth factor-beta1 expression and promotes tumor progression. Transplantation. (2003) 76(3):597–602. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000081399.75231.3B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Di Maira T, Little EC, Berenguer M. Immunosuppression in liver transplant. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol (2020) 46-47:101681. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2020.101681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen K, Sheng J, Ma B, Cao W, Hernanda PY, Liu J, et al. Suppression of hepatocellular carcinoma by mycophenolic acid in experimental models and in patients. Transplantation. (2019) 103(5):929–37. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsai YF, Liu FC, Chen CY, Lin JR, Yu HP. Effect of mycophenolate mofetil therapy on recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: A population-based cohort study. J Clin Med (2021) 10(8):1558. doi: 10.3390/jcm10081558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gundisch S, Boeckeler E, Behrends U, Amtmann E, Ehrhardt H, Jeremias I. Glucocorticoids augment survival and proliferation of tumor cells. Anticancer Res (2012) 32(10):4251–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wei Q, Gao F, Zhuang R, Ling Q, Ke Q, Wu J, et al. A national report from China liver transplant registry: steroid avoidance after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res (2017) 29(5):426–37. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2017.05.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li BCW, Chiu J, Shing K, Kwok GGW, Tang V, Leung R, et al. The outcomes of systemic treatment in recurrent hepatocellular carcinomas following liver transplants. Adv Ther (2021) 38(7):3900–10. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01800-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fantus D, Thomson AW. Evolving perspectives of mTOR complexes in immunity and transplantation. Am J Transplant. (2015) 15(4):891–902. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mossmann D, Park S, Hall MN. mTOR signalling and cellular metabolism are mutual determinants in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. (2018) 18(12):744–57. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0074-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Geissler EK, Schnitzbauer AA, Zulke C, Lamby PE, Proneth A, Duvoux C, et al. Sirolimus use in liver transplant recipients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomized, multicenter, open-label phase 3 trial. Transplantation. (2016) 100(1):116–25. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schnitzbauer AA, Filmann N, Adam R, Bachellier P, Bechstein WO, Becker T, et al. mTOR inhibition is most beneficial after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with active tumors. Ann Surg (2020) 272(5):855–62. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nitta H, Younès A, El-domiaty N, Karam V, Sobesky R, Vibert E, et al. High trough levels of everolimus combined to sorafenib improve patients survival after hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence in liver transplant recipients. Transplant Int (2021) 34(7):1293–305. doi: 10.1111/tri.13897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saliba F, Duvoux C, Gugenheim J, Kamar N, Dharancy S, Salame E, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus and mycophenolic acid with early tacrolimus withdrawal after liver transplantation: A multicenter randomized trial. Am J Transplant. (2017) 17(7):1843–52. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kraehenbuehl L, Weng CH, Eghbali S, Wolchok JD, Merghoub T. Enhancing immunotherapy in cancer by targeting emerging immunomodulatory pathways. Nat Rev Clin Oncol (2022) 19(1):37–50. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00552-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. De Toni EN, Gerbes AL. Tapering of immunosuppression and sustained treatment with nivolumab in a liver transplant recipient. Gastroenterology. (2017) 152(6):1631–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Friend BD, Venick RS, McDiarmid SV, Zhou X, Naini B, Wang H, et al. Fatal orthotopic liver transplant organ rejection induced by a checkpoint inhibitor in two patients with refractory, metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer (2017) 64(12):e26682. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Varkaris A, Lewis DW, Nugent FW. Preserved liver transplant after PD-1 pathway inhibitor for hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol (2017) 112(12):1895–6. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. DeLeon TT, Salomao MA, Aqel BA, Sonbol MB, Yokoda RT, Ali AH, et al. Pilot evaluation of PD-1 inhibition in metastatic cancer patients with a history of liver transplantation: the Mayo clinic experience. J Gastrointest Oncol (2018) 9(6):1054–62. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2018.07.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gassmann D, Weiler S, Mertens JC, Reiner CS, Vrugt B, Nageli M, et al. Liver allograft failure after nivolumab treatment-a case report with systematic literature research. Transplant Direct. (2018) 4(8):e376. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000000814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gomez P, Naim A, Zucker K, Wong M. A case of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) immunotherapy inducing liver transplant rejection. Am J Gastroenterology. (2018) 113:S1347–S. doi: 10.14309/00000434-201810001-02415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rammohan A, Reddy MS, Farouk M, Vargese J, Rela M. Pembrolizumab for metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma following live donor liver transplantation: The silver bullet? Hepatology (2018) 67(3):1166–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.29575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kumar S. Nivolumab-induced severe allograft rejection in recurrent post-transplant hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterology. (2019) 114:S1251–S2. doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000598472.41771.5f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Al Jarroudi O, Ulusakarya A, Almohamad W, Afqir S, Morere JF. Anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) immunotherapy for metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: A report of three cases. Cureus. (2020) 12(10):e11150. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Amjad W, Kotiah S, Gupta A, Morris M, Liu L, Thuluvath PJ. Successful treatment of disseminated hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation with nivolumab. J Clin Exp Hepatol (2020) 10(2):185–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2019.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pandey A, Cohen DJ. Ipilumumab for hepatocellular cancer in a liver transplant recipient, with durable response, tolerance and without allograft rejection. Immunotherapy. (2020) 12(5):287–92. doi: 10.2217/imt-2020-0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Qiu J, Tang W, Du C. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: A case report and literature review. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. (2020) 20(9):720–7. doi: 10.2174/1568009620666200520084415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhuang L, Mou HB, Yu LF, Zhu HK, Yang Z, Liao Q, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int (2020) 19(1):91–3. doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2019.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shi GM, Wang J, Huang XW, Huang XY, He YF, Ji Y, et al. Graft programmed death ligand 1 expression as a marker for transplant rejection following anti-programmed death 1 immunotherapy for recurrent liver tumors. Liver Transpl. (2021) 27(3):444–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.25887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ben Khaled N, Roessler D, Reiter FP, Seidensticker M, Guba M, De Toni EN. Extending the use of atezolizumab and bevacizumab to a liver transplant recipient: Need for a posttransplant registry. Liver Transpl. (2021) 27(6):928–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.26011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang Z, Sun J, Zhuang L, Mou H, Zheng S. Preliminary evaluation of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab as salvage treatment for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl (2022) 28(5):895–6. doi: 10.1002/lt.26416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mao JX, Guo WY, Guo M, Liu C, Teng F, Ding GS. Acute rejection after liver transplantation is less common, but predicts better prognosis in HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatol Int (2020) 14(3):347–61. doi: 10.1007/s12072-020-10022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Morales RE, Shoushtari AN, Walsh MM, Grewal P, Lipson EJ, Carvajal RD. Safety and efficacy of ipilimumab to treat advanced melanoma in the setting of liver transplantation. J Immunother Cancer. (2015) 3:22. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0066-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ranganath HA, Panella TJ. Administration of ipilimumab to a liver transplant recipient with unresectable metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. (2015) 38(5):211. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dueland S, Guren TK, Boberg KM, Reims HM, Grzyb K, Aamdal S, et al. Acute liver graft rejection after ipilimumab therapy. Ann Oncol (2017) 28(10):2619–20. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Schvartsman G, Perez K, Sood G, Katkhuda R, Tawbi H. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a liver transplant recipient with melanoma. Ann Intern Med (2017) 167(5):361–2. doi: 10.7326/L17-0187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Biondani P, De Martin E, Samuel D. Safety of an anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor in a liver transplant recipient. Ann Oncol (2018) 29(1):286–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kuo JC, Lilly LB, Hogg D. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a liver transplant recipient with a rare subtype of melanoma: a case report and literature review. Melanoma Res (2018) 28(1):61–4. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chen JA, Esteghamat N, Kim EJ, Garcia G, Gong J, Fakih MG, et al. PD-1 blockade in a liver transplant recipient with microsatellite unstable metastatic colorectal cancer and hepatic impairment. J Natl Compr Canc Netw (2019) 17(9):1026–30. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.7328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Braun M, Fuchs V, Kian W, Roisman L, Peled N, Rosenberg E, et al. Nivolumab induced hepatocanalicular cholestasis and liver rejection in a patient with lung cancer and liver transplant. J Thorac Oncol (2020) 15(9):e149–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.01.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brumfiel CM, Patel MH, Aqel B, Lehrer M, Patel SH, Seetharam M. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in a liver transplant recipient with autoimmune disease and metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAAD Case Rep (2021) 14:78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kondo T, Kawachi S, Nakatsugawa M, Takeda A, Kikawada N, Aihara Y, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent/metastatic hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in a liver transplant recipient. Auris Nasus Larynx (2021) 49(4):721–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Delyon J, Zuber J, Dorent R, Poujol-Robert A, Peraldi MN, Anglicheau D, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in transplantation-a case series and comprehensive review of current knowledge. Transplantation. (2021) 105(1):67–78. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Hu B, Yang XB, Sang XT. Liver graft rejection following immune checkpoint inhibitors treatment: a review. Med Oncol (2019) 36(11):94. doi: 10.1007/s12032-019-1316-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Munker S, De Toni EN. Use of checkpoint inhibitors in liver transplant recipients. United Eur Gastroenterol J (2018) 6(7):970–3. doi: 10.1177/2050640618774631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Thomson AW, Vionnet J, Sanchez-Fueyo A. Understanding, predicting and achieving liver transplant tolerance: from bench to bedside. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (2020) 17(12):719–39. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0334-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. (2018) 359(6382):1350–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aar4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Patsoukis N, Wang Q, Strauss L, Boussiotis VA. Revisiting the PD-1 pathway. Sci Adv (2020) 6(38):eabd2712. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd2712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Anderson AC, Joller N, Kuchroo VK. Lag-3, Tim-3, and TIGIT: Co-inhibitory receptors with specialized functions in immune regulation. Immunity. (2016) 44(5):989–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Ahn E, Araki K, Hashimoto M, Li W, Riley JL, Cheung J, et al. Role of PD-1 during effector CD8 T cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2018) 115(18):4749–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718217115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Baas M, Besançon A, Goncalves T, Valette F, Yagita H, Sawitzki B, et al. TGFβ-dependent expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 controls CD8+ T cell anergy in transplant tolerance. eLife (2016) 5:e08133. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Farhood B, Najafi M, Mortezaee K. CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. J Cell Physiol (2019) 234(6):8509–21. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Morita M, Fujino M, Jiang G, Kitazawa Y, Xie L, Azuma M, et al. PD-1/B7-H1 interaction contribute to the spontaneous acceptance of mouse liver allograft. Am J Transplant. (2010) 10(1):40–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02859.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Takahashi T, Hsiao HM, Tanaka S, Li W, Higashikubo R, Scozzi D, et al. PD-1 expression on CD8(+) T cells regulates their differentiation within lung allografts and is critical for tolerance induction. Am J Transplant. (2018) 18(1):216–25. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Atif M, Conti F, Gorochov G, Oo YH, Miyara M. Regulatory T cells in solid organ transplantation. Clin Transl Immunol (2020) 9(2):e01099. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Apostolidis SA, Rodriguez-Rodriguez N, Suarez-Fueyo A, Dioufa N, Ozcan E, Crispin JC, et al. Phosphatase PP2A is requisite for the function of regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol (2016) 17(5):556–64. doi: 10.1038/ni.3390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Besancon A, Baas M, Goncalves T, Valette F, Waldmann H, Chatenoud L, et al. The induction and maintenance of transplant tolerance engages both regulatory and anergic CD4(+) T cells. Front Immunol (2017) 8:218. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Paterson AM, Lovitch SB, Sage PT, Juneja VR, Lee Y, Trombley JD, et al. Deletion of CTLA-4 on regulatory T cells during adulthood leads to resistance to autoimmunity. J Exp Med (2015) 212(10):1603–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kamada T, Togashi Y, Tay C, Ha D, Sasaki A, Nakamura Y, et al. PD-1(+) regulatory T cells amplified by PD-1 blockade promote hyperprogression of cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2019) 116(20):9999–10008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1822001116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lin H, Wei S, Hurt EM, Green MD, Zhao L, Vatan L, et al. Host expression of PD-L1 determines efficacy of PD-L1 pathway blockade-mediated tumor regression. J Clin Invest. (2018) 128(2):805–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI96113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Peng Q, Qiu X, Zhang Z, Zhang S, Zhang Y, Liang Y, et al. PD-L1 on dendritic cells attenuates T cell activation and regulates response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Commun (2020) 11(1):4835. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18570-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lucas ED, Schafer JB, Matsuda J, Kraus M, Burchill MA, Tamburini BAJ. PD-L1 reverse signaling in dermal dendritic cells promotes dendritic cell migration required for skin immunity. Cell Rep (2020) 33(2):108258. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Gordon SR, Maute RL, Dulken BW, Hutter G, George BM, McCracken MN, et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature. (2017) 545(7655):495–9. doi: 10.1038/nature22396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hartley GP, Chow L, Ammons DT, Wheat WH, Dow SW. Programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) signaling regulates macrophage proliferation and activation. Cancer Immunol Res (2018) 6(10):1260–73. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Yoshida K, Okamoto M, Sasaki J, Kuroda C, Ishida H, Ueda K, et al. Anti-PD-1 antibody decreases tumour-infiltrating regulatory T cells. BMC Cancer. (2020) 20(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6499-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Zappasodi R, Serganova I, Cohen IJ, Maeda M, Shindo M, Senbabaoglu Y, et al. CTLA-4 blockade drives loss of t(reg) stability in glycolysis-low tumours. Nature. (2021) 591(7851):652–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03326-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Selby MJ, Engelhardt JJ, Quigley M, Henning KA, Chen T, Srinivasan M, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies of IgG2a isotype enhance antitumor activity through reduction of intratumoral regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol Res (2013) 1(1):32–42. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Sun C, Mezzadra R, Schumacher TN. Regulation and function of the PD-L1 checkpoint. Immunity. (2018) 48(3):434–52. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zhao Y, Chen S, Lan P, Wu C, Dou Y, Xiao X, et al. Macrophage subpopulations and their impact on chronic allograft rejection versus graft acceptance in a mouse heart transplant model. Am J Transplant. (2018) 18(3):604–16. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ono Y, Perez-Gutierrez A, Nakao T, Dai H, Camirand G, Yoshida O, et al. Graft-infiltrating PD-L1hicross-dressed dendritic cells regulate antidonor T cell responses in mouse liver transplant tolerance. Hepatology. (2018) 67(4):1499–515. doi: 10.1002/hep.29529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bracamonte-Baran W, Gilotra NA, Won T, Rodriguez KM, Talor MV, Oh BC, et al. Endothelial stromal PD-L1 (Programmed death ligand 1) modulates CD8(+) T-cell infiltration after heart transplantation. Circ Heart Fail (2021) 14(10):e007982. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Matsushima H, Morita-Nakagawa M, Datta S, Pavicic PG, Jr., Hamilton TA, Abu-Elmagd K, et al. Blockade or deficiency of PD-L1 expression in intestinal allograft accelerates graft tissue injury in mice. Am J Transplant. (2022) 22(3):955–65. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Dixon KO, Tabaka M, Schramm MA, Xiao S, Tang R, Dionne D. Tim3 blockade in dendritic cells may potentiate antitumor immunity. Cancer Discovery (2021) 11(8):1873. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-RW2021-084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Lichtenegger FS, Rothe M, Schnorfeil FM, Deiser K, Krupka C, Augsberger C, et al. Targeting LAG-3 and PD-1 to enhance T cell activation by antigen-presenting cells. Front Immunol (2018) 9:12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Wang Y, Zhou S, Yang F, Qi X, Wang X, Guan X, et al. Treatment-related adverse events of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors in clinical trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol (2019) 5(7):1008–19. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Bai X, Wang X, Ma G, Song J, Liu X, Wu X, et al. Improvement of PD-1 blockade efficacy and elimination of immune-related gastrointestinal adverse effect by mTOR inhibitor. Front Immunol (2021) 12:793831. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.793831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Esfahani K, Al-Aubodah T-A, Thebault P, Lapointe R, Hudson M, Johnson NA, et al. Targeting the mTOR pathway uncouples the efficacy and toxicity of PD-1 blockade in renal transplantation. Nat Commun (2019) 10(1):4712. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12628-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lipson EJ, Bagnasco SM, Moore J, Jang S, Patel MJ, Zachary AA, et al. Tumor regression and allograft rejection after administration of anti-PD-1. New Engl J Med (2016) 374(9):896–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1509268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]