Abstract

Cancer is the second leading cause of mortality globally which remains a continuing threat to human health today. Drug insensitivity and resistance are critical hurdles in cancer treatment; therefore, the development of new entities targeting malignant cells is considered a high priority. Targeted therapy is the cornerstone of precision medicine. The synthesis of benzimidazole has garnered the attention of medicinal chemists and biologists due to its remarkable medicinal and pharmacological properties. Benzimidazole has a heterocyclic pharmacophore, which is an essential scaffold in drug and pharmaceutical development. Multiple studies have demonstrated the bioactivities of benzimidazole and its derivatives as potential anticancer therapeutics, either through targeting specific molecules or non-gene-specific strategies. This review provides an update on the mechanism of actions of various benzimidazole derivatives and the structure‒activity relationship from conventional anticancer to precision healthcare and from bench to clinics.

Key Words: Benzimidazole derivatives, Targeted therapy, Anticancer, Precision medicine

Graphical abstract

The benzimidazole pharmacophore resembles naturally occurring purine nucleotides and exerts anticancer effects through various mechanisms.

1. Benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents

The rapid escalation of cancer incidence and the incremental mortality rate have made cancer a global burden. The development of tumour resistance, drug toxicities, cancer recurrence, and the low success rate of drug development reaching clinical trials are limiting factors that aggravate the challenges in cancer treatment. One of the focuses on improving treatment efficacy and survival rate of cancer patients is the search for new classes of anticancer drugs. The traditional ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach using conventional non-targeting agents is toxic to healthy cells and may not benefit all patients. As cancer is a significant focus of the precision medicine initiative, personalized therapeutic approaches aimed to maximize outcomes based on individual variability in genetic profile, lifestyle, and environmental factors are widely gaining acceptance1. Therefore, targeted therapy provides the foundation of precision medicine to allow tailored treatment targeting specific oncogenic markers in cancers.

Among the anticancer drugs discovered in recent years, various benzimidazole derivatives have gained attention in anticancer agent development due to their diverse biological activities and clinical applications. The unique core structure of benzimidazole and its minimal toxicity property has made it an excellent scaffold in anticancer drug development. Benzimidazole (also known as 1H-benzimidazole, 1,3-benzodiazole, benzoglyoxaline, iminazole, and imidazole) is an aromatic organic compound that contains a benzene ring fused to an imidazole ring at 4,5-position to form a bicyclic ring2,3. Historically, benzimidazole (i.e., 2,6-dimethylbenzimidazole) was first synthesized by Hoebrecker, followed by Ladenberg and Wundt in the 1870s2. Benzimidazole has a molecular weight of 118.14 g/mol and appears as white tabular crystals. Benzimidazole contains a hydrogen atom attached to nitrogen in the 1-position and can form a tautomer upon interaction with aprotic solvents, such as water or the existence of more than one benzimidazole molecule2. Nonetheless, substitution at position N will prohibit the tautomerism process3. Benzimidazole is a weak base with a pK value at 5.3 and 12.3 for pKa1 and pKa2, respectively4. Therefore, the benzimidazole ring is highly stable and can withstand extreme conditions such as being heated under pressure up to 270 °C in a concentrated sulphuric acid solution or vigorous treatment with hot hydrochloric acid or with alkalis4.

Benzimidazole is an important biologically active heterocyclic compound that serves as one of the top ten most frequently employed five-membered nitrogen heterocycles among the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs5. The electron-rich nitrogen heterocycles of benzimidazole could readily accept or donate protons and easily allow the formation of diverse weak interactions, offering an advantage for it to bind with a broad spectrum of therapeutic targets, thereby exhibiting wide-ranging pharmacological activities6. Mounting evidence has reported a vast pharmacological profile of benzimidazole and its derivatives, substitution at the 1, 2, 5 and/or 6-positions, in multiple categories of therapeutic agents with unique properties, including antimicrobial7, 8, 9, 10, anti-tuberculosis11, 12, 13, anti-viral14, 15, 16, anti-ulcer17,18, anti-inflammatory19, 20, 21, anti-diabetic, anti-convulsant22,23, anti-hypertensive24, and anti-malarial25, 26, 27. There is also increasing evidence highlighting the prospect of benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents, particularly in the advancement of precision medicine, which will be discussed in this review.

Benzimidazoles have a structure that resembles naturally occurring purine nucleotides, which allows them to easily contact the biopolymers within the living system28. The benzimidazole pharmacophore can form hydrogen bonds, amide-ring and aromatic-ring interactions, hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals forces, polar contact and pi-bonds with the targets (Table 1, Fig. 1). Benzimidazole and its derivatives are reported to play key roles as topoisomerase inhibitors, DNA intercalation and alkylating agents, androgen receptor antagonists, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, protein kinase inhibitors, dihydrofolate reductase inhibitors, and microtubule inhibitors29,30. Benzimidazole derivatives have also been reported to act as epigenetic regulators with demonstrated promising anticancer activities31, 32, 33, 34. Examples of benzimidazole-based drugs that have gained approval clinically encompass Binimetinib (NCT04965818 and NCT03170206), Bendamustine (NCT04217317 and NCT04510636), Selumetinib (NCT02768766), Abemaciclib (NCT04003896 and NCT0404-0205), Veliparib (NCT02723864 and NCT01434316), Dovitinib (NCT01635907), Pracinostat (NCT03848754), Galeterone (NCT-04098081) and Nazartinib (NCT02335944 and NCT02108964)35. This review article summarises the recent literature on benzimidazole derivatives exhibiting anticancer properties based on different mechanisms.

Table 1.

The interaction between the benzimidazole pharmacophore of compounds and respective target receptors.

| Category | PDB ID | RMSD (Å) | Compd. | Receptor | Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA intercalation and alkylating agents | 2B3E | 1.36 | DBN | DNA | Hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, aromatic |

| 453D | 1.80 | E96 | DNA | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, pi–pi | |

| 1VZK | 1.77 | D1B | DNA | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, pi–pi, aromatic | |

| 442D | 1.60 | IB | DNA | Van der Waals, hydrogen bond, polar, carbon‒pi | |

| PARP inhibitors | 3KJD | 1.95 | 78P | PARP-2 | Hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, pi–pi, donor‒pi, amide-ring, hydrophobic |

| 7AAC | 1.59 | 78P | PARP-1 | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, pi–pi, donor‒pi, amide-ring, aromatic, hydrophobic | |

| 5WS1 | 1.90 | 7U9 | PARP-1 | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, pi–pi, donor‒pi, amide ring, aromatic, hydrophobic | |

| 6NRJ | 1.65 | KYJ | PARP-1 | Hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, donor‒pi, aromatic, hydrophobic | |

| Kinase inhibitors | 1ZOH | 1.81 | K44 | CK2 | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, methionine‒sulfur‒pi, hydrophobic |

| 4KWP | 1.25 | EXX | CK2 | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, methionine‒sulfur‒pi, hydrophobic | |

| 3H30 | 1.56 | RFZ | CK2 | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, methionine‒sulfur‒pi | |

| 4DSU | 1.70 | BZI | GTPase KRas | Hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi | |

| 3DA6 | 2.00 | BZ9 | MAPK10 | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi, methionine‒sulfur‒pi | |

| 3EWH | 1.60 | K11 | VEGFR2 | Polar, carbon‒pi | |

| 5KGD | 1.98 | 6SL | Ser/Thr protein kinase Pim 1 | Hydrogen, polar, carbon‒pi | |

| Androgen receptor inhibitors | 2YLO | 2.5 | YLO | Androgen receptor | Van der Waals, polar, carbon‒pi, pi–pi |

| 4HLW | 2.5 | 17W | Androgen receptor | Polar, pi–pi | |

| Epigenetic modulators | 7KBG | 1.26 | WBD | HDAC2 | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, pi–pi, hydrophobic |

| 6DQF | 1.68 | H61 | KDM5A | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, donor‒pi, hydrophobic | |

| 5PHK | 1.25 | BZI | KDM4D | Van der Waals, hydrogen, polar, covalent, hydrophobic | |

| 6G5X | 1.78 | MY7 | KDM4A | Van der Waals, hydrogen, carbon‒pi, pi–pi, donor‒pi, cation‒pi, aromatic, covalent, metal complex |

Figure 1.

Key interactions between the benzimidazole pharmacophore of benzimidazole derivatives and target receptors. Representative structures illustrating key interactions between the benzimidazole moiety of various compounds with (a) kinases (PDB ID: 3DA6), (b) PARP proteins (PDB ID: 7AAC), (c) androgen receptors (PDB ID: 2YLO), (d) epigenetic regulators (PDB ID: 7KBG) and (e) DNA (PDB ID: 1VZK). Structures and interactions were obtained from the PDBe database and visualized using PyMOL 2.0 software. Receptors are presented as cartoons, and residue side chains are presented as licorice according to the elements: oxygen is red, nitrogen is blue, and sulfur is yellow. Crystal waters are presented as red spheres. Benzimidazole compounds are presented as green licorice.

Available X-ray crystal structures with root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) ≤ 2.5 Å from each category were selected for analysis. In addition, ligand–receptor interactions between the benzimidazole moiety and target receptors are presented based on analyses from Protein Data Bank in Europe (PDBe) database (Table 1, Fig. 1).

1.1. Traditional non-oncogene targeting anticancer agents

1.1.1. Topoisomerase inhibitors

DNA topoisomerase is an important ubiquitous enzyme associated with genomic integrity involving DNA replication, transcription, recombination, and chromatin remodelling36. Type I topoisomerase (Topo I) cleaves only one strand of the DNA molecule. In contrast, type II topoisomerase (Topo II) functions by cutting both strands of the double-stranded DNA molecule37. Cells mainly utilize this enzyme to maintain the chromosome segregation and topology of DNA. In general, these topoisomerase inhibitors work as catalytic inhibitors to suppress topoisomerase activity, to activate enzyme activity towards bona fide or surrogate substrate; or convert topoisomerase into a toxic enzyme in the cells38,39. Much effort has been channelled into developing topoisomerase inhibitors or topoisomerase poisons using the benzimidazole scaffold in cancer cells. Therefore, targeting DNA topoisomerases to prevent cancer replicative immortality has been one of the research interests in anticancer drug development for several decades (Fig. 2).

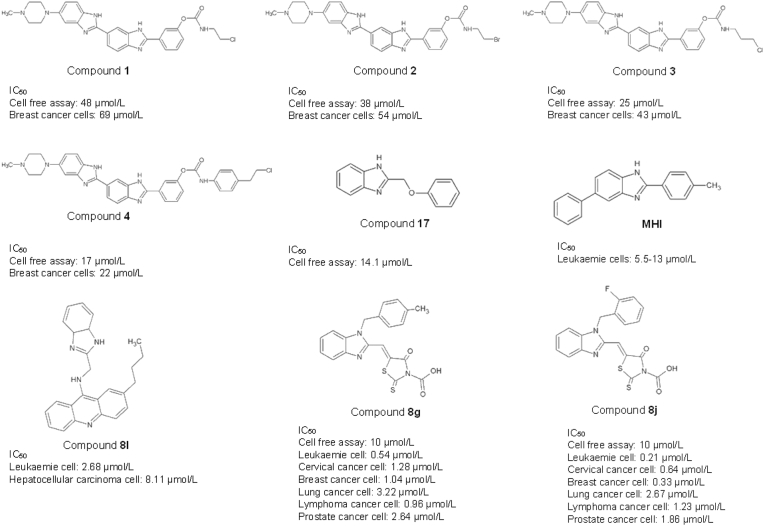

Figure 2.

Benzimidazole derivatives as topoisomerase inhibitors.

The flexible nature of the bis-benzimidazole ring allows the high-affinity binding of its derivatives to the DNA, which leads to the change in DNA conformation and inhibits the formation of the cleavable complex40. Bielawski and colleagues have reported the use of bis-benzimidazole derivatives with chloroalkyl and bromoalkyl moieties in developing the Topo I and Topo II inhibitors, compounds 1–4. These compounds inhibit DNA synthesis by interacting with the GC base pair at the DNA minor groove, leading to the irreversible inhibition of proliferation in the MDA-MB-231 estrogen receptor-negative human breast cancer cells. The four compounds 1–4 have been found to hamper the incorporation of [3H]thymidine into the DNA at 48 ± 2, 38 ± 2, 25 ± 3 and 17 ± 3 μmol/L, respectively, resulting in the reduction of the MDA-MB-231 cell viability40. Oksuzoglu et al.41 have cleverly synthesized eighteen derivatives of 2,5-disubstituted-benzoxazole and benzimidazole with demonstrated Topo I and Topo II enzymatic activities. Among the eighteen compounds, 2-phenoxymethylbe-nzimidazole (compound 17) contained the benzimidazole moiety and exhibited the most potency in inhibiting DNA Topo I enzymatic activities, with IC50 values at 14.1 μmol/L. MH1 is another potent topoisomerase inhibitor, synthesis of 2,5-disubstituted benzimidazoles, that binds to DNA at the minor groove in leukemia cells (Molt4 cells), inhibiting the conversion of supercoiled DNA to circular DNA, leading to G2/M arrest and apoptosis42. Gao et al.43 synthesized a benzimidazole-acridine derivative, compound 8I, with reported strong cytotoxic effects against K562 leukaemia and HepG-2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells at 2.68 and 8.11 μmol/L, respectively. This compound functions as Topo I inhibitor and promotes cell death in K562 cells through the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. In another study, Li et al.44 demonstrated a panel of benzimidazole-rhodanine conjugates to possess strong anti-proliferative activity against human lymphoma, acute leukaemia, human cervical, breast, lung, and prostate cancer cells. Among the 35 synthesized benzimidazole–rhodanine conjugates, compounds 8g and 8j exhibited the best Topo II inhibitory activity at 10 μmol/L. Compounds 8g and 8j act as non-intercalative Topo II inhibitors that bind to the ATP-binding site of the Topo II enzyme to block the enzymatic activity. The presence of the benzyl and electron donor groups on the compound revealed a significant impact on Topo II inhibitory activity.

1.1.2. DNA intercalation and alkylating agents

Protein-DNA binding interactions are implicated in various cancer pathways and often require the direct or indirect contact of protein at the major and/or minor grooves of DNA45,46. The interactions play a significant role in DNA replication, gene transcription, chromosomal packaging, and DNA repair47,48. However, the interruption of protein-DNA interactions by the DNA intercalator could alter the DNA conformation and the biological functions of DNA-binding proteins such as transcription factors, topoisomerase, polymerase and DNA repair proteins49. Therefore, DNA intercalators are widely accepted in cancer chemotherapy50. Drugs targeting protein-DNA interaction work either through covalent or non-covalent binding51. The former involves metallointercalators (e.g., cisplatin) which form a dual-inhibition mode (i.e., intercalation and metal coordination) that leads to irreversible binding and ultimately induces cancer cell death. On the contrary, non-covalent binding is reversible in which intercalation, groove binding or electrostatic interactions take place between two adjacent base pairs of duplex DNA, resulting in the inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis and consequently impair cancer cell replication. The mechanism involved either intercalation, grooves binding or electrostatic interactions47,50,52,53. Most benzimidazole derivatives act as DNA minor groove binders (MGBs), particularly at the AT-rich sequences (Fig. 3).

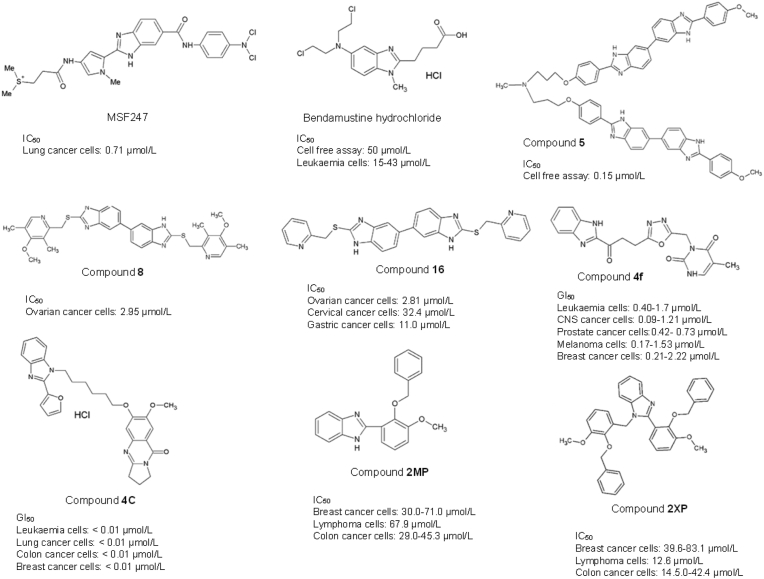

Figure 3.

Benzimidazole derivatives as DNA intercalation and alkylating agents.

Yamori et al.52 have synthesized a compound known as MS-247, (2-[[N-[1-methyl-2-[5-[N-[4-[N,N-bis(2-chloroethyl) amino] phenyl]] carbamoyl]-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl] pyrrol-4-yl] carbamoyl] ethyldimethylsulfonium di-p-toluenesulfonate) that exhibited antitumour activity in 39 cancer cell lines and 17 tumour xenografts of the lung, colon, stomach, breast, and ovarian cancers. MS-247 consists of a netropsin-like moiety and an alkylating residue in the structure to facilitate the DNA minor groove binding and DNA alkylation properties, respectively. MS-247 attaches to the AT-rich sites of the DNA minor groove to inhibit DNA synthesis via the formation of DNA–DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICL). This ultimately leads to cell cycle blockage at the G2/M phase and apoptosis induction52,54.

Bisbenzimodazole compound 5, another widely studied DNA MGB, is a symmetrical bis-benzimidazole, 2,2′-di-[[(3,5-dimethyl-4-methoxy)pyrid-2-yl]methylenethio]-5,5′-bis-1H,1′H-benzimidazole synthesized by Joubert et al.55 as a dimeric bis-benzimidazole molecule that recognises ten base pair ([A‘T]4-[G‘C]-[A‘T]4 motifs) in the DNA sequence. Interestingly, it is less sensitive on the human ovarian carcinoma cells (IC50 > 10 μmol/L range) as compared to two other benzimidazole derivatives (IC50 <<1 μmol/L), which, however, displayed no known role as minor groove binders and quick uptake by the tumour cell. The central nitrogen in the –N+H(Me)‒ linker of compound 5 was predicted to have the highest binding affinity towards the DNA B-helix. Compound 8 is another bis-benzimidazole derivative with an omeprazole thioether group connected to the 2-position benzimidazole, demonstrating MGB function. Compound 8 exhibited cytotoxic effects on ovarian cancer cells at IC50 = 2.95 μmol/L but was least effective on cervical and gastric cancer cells (IC50 = or > 50 μmol/L)56. Similarly, Compound 16 with pyrid-4yl substitute that Yang and colleagues56 synthesized is another MGB also demonstrated a potent antitumour effect at IC50 = 2.81, 32.4 and 11.0 μmol/L on SKOV-3 ovarian, HeLa cervical and BGC-823 gastric cancer cells respectively.

Bendamustine hydrochloride comprises a benzimidazole heterocyclic ring, mechlorethamine, N-substituted methyl group and butyric acid substitution. The bendamustine compound can form intra- and interstrand crosslinks between DNA bases, impede DNA replication, deter transcription and repair, and disrupt the DNA matrix function during DNA replication57. Bendamustine is an alkylating agent which causes DNA breakage. It is more potent than other DNA-alkylating agents such as cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, or carmustine, highlighting the role of the benzimidazole ring in enhancing the anticancer properties of bendamustine compared to other conventional 2-chloroethylamine alkylators58. In 2008, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved bendamustine hydrochloride (TREANDA®) as a DNA alkylating agent targeting chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL)57. The molecular mechanism of Bendamustine in cancer includes the induction of S-phase mitotic arrest, mitotic catastrophe and the activation of p53-mediated apoptosis58. However, this drug may cause pyrexia, nausea, and vomiting in CLL patients. In addition, headache, fatigue, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhoea, pyrexia, rash, constipation, anorexia, cough, dyspnea, and stomatitis were also commonly observed in patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma59,60.

The benzimidazole ring in synthesized compounds has been shown to increase anticancer potency selectively in leukaemia61,62. Compound 4f (NSC: 761982/1) uses bendamustine and chlorambucil as templates. Compound 4f consists of a methylene linker which joins the benzimidazole and oxadiazole. Compound 4f is cytotoxic on leukaemia, melanoma, ovarian, prostate, breast, colon, central nervous system, and non-small cell lung cancer cells63. The presence of oxadiazole conjugate was found to enhance the antiproliferative effects compared to thiadiazole, triazolo-thiadiazines and triazolo-thiadiazoles63. Compound 4c is a pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD)-conjugated benzimidazole derivative that has demonstrated remarkable DNA-binding affinity at GI50 value and potent inhibition of cancer cell growth with concentration less than 10 nmol/L in the 60 cancer cell lines screen of NCI, comprising of leukaemia, melanoma, lung, ovarian, colon, renal, breast, prostate, and CNS cancers64. In 2013, Al-Mudaris and colleagues65 successfully synthesized the benzyl vanillin (2-(benzyloxy)-3-methoxybenzaldehyde) analogues, 2MP, 2-(2-benzyloxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1H-benzimidazole) and 2XP (N-1-(2-benzyloxy-3-methoxybenzyl)-2-(2-benzyloxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1H-benzimidazole), and screened them for anticancer potentials. The addition of benzimidazole moiety to the side chain has improved the DNA binding affinity, and enhanced the cytotoxic effect of 2MP and 2XP compared to their parent structure. However, the anticancer activity was not shown in 2MP but in 2XP. In addition, 2XP exhibited anti-proliferative capabilities towards HL60 leukaemia cancer cells and induced G2/M phase cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in these cells.

1.1.3. Microtubule inhibitors

Microtubules are major cytoskeleton components composed of α- and β-tubulin subunits66. Microtubules help maintain cellular shape development, motility, and facilitate cell–cell communication, mitosis and cell division66. Hence, the dynamic instability of microtubules would inevitably result in a continuous rapid turnover, which is critical for mitosis67. Microtubule inhibitors, also known as antimitotic drugs, function by suppressing the spindle-microtubule dynamics, leading to the partial attachment of microtubules to chromosomes at their kinetochores, and the incomplete formation of metaphase spindles68. Treatment with such inhibitors would arrest mitosis at the metaphase–anaphase transition and induce apoptotic cell death66,67,69. This strategy has been successful with the employment of clinical drugs such as paclitaxel and Vinca alkaloids in cancers such as Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, breast, colon, cervical, ovarian and testicular carcinoma69, 70, 71. However, toxicity and multidrug resistance are limiting factors in the development of microtubule targeting agents (MTAs)72. The paclitaxel site, Vinca and Colchicine domains are the three main binding sites targeted by MTAs through microtubule stabilization and destabilization66,72. The benzimidazole derivatives function as a microtubule inhibitor are summarized in Fig. 4.

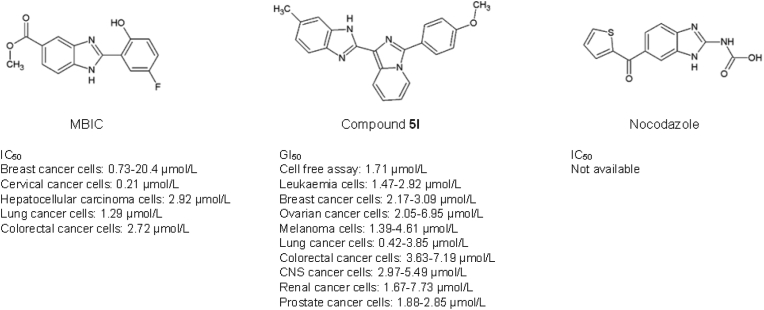

Figure 4.

Benzimidazole derivatives used as microtubule inhibitors.

Methyl 2-(5-fluoro-2-hydroxyphenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-5-carboxylate (MBIC) is a microtubule inhibitor that consists of 2-hydroxyl and 5-fluoro substitution in the aryl ring, and a methyl ester group giving a strong cytotoxic effect against breast cancer cells73,74. The MBIC was reported to induce mitosis and stimulates mitochondria-dependent intrinsic apoptotic cell death in cervical cancer75. Cervical cancer cells treated with MBIC exhibited G2-M phase arrest followed by cancer cell death. MBIC was also reported to inhibit microtubule polymerisation, through the up-regulation of cyclin B1, cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), and budding uninhibited by benzimidazole-related 1 (BubR1) proteins and down-regulation of the Aurora B protein, indicating the occurrence of mitotic arrest. Besides, MBIC also demonstrated cytotoxicity against a panel of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated activation of the JNK signalling cascade76.

Nocodazole (methyl [5-(2-thienylcarbonyl)-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl]carbamate) functions as a tubulin destabiliser that disrupts the microtubule formation in prometaphase cells and hampers the ability of the microtubules to attach to the chromosome kinetochores, leading to cell cycle arrest, and eventually cell death77, 78, 79. The benzimidazole core is substituted at position 2 by a (methoxycarbonyl) amino group and position 5 by a 2-thienoyl group. A study conducted by Blajeski and co-workers demonstrated that selected breast cancer cells (i.e., MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-453, HS0578T, SKBr3, and ZR-75-10) to be susceptible to mitotic arrest when treated with nocodazole. These breast cancer cells undergo p21-associated cell cycle arrest at G1 and G2 phases post-treatment with 1 μmol/L Nocodazole78.

Compound 5l is an imidazo[1,5-a]pyridine-benzimidazole hybrid that showed significant cytotoxic activity against the 60 human cancer cell lines with GI50 values ranging from 0.43 to 7.73 μmol/L while displaying no cytotoxicity in normal human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells80. The cytotoxic effects of compound 5l on cancer cells are attributed to its binding pattern to the colchicine binding site of the tubulin. The presence of the methoxy phenyl group improved the binding affinity to the colchicine binding site and further enhanced its antiproliferative activity. Compound 5l binds to the colchicine binding site to suppress tubulin polymerisation by 71.27% at the IC50 value of 1.71 μmol/L. This treatment concentration eventually resulted in ROS production and mitochondrial-dependent cell death of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. In addition, compound 5l also inhibits tubulin polymerisation and the p13/AKT pathway to retard breast tumour growth.

1.2. Target-specific modalities as the basis of precision medicine

1.2.1. Kinase inhibitors

Kinases are enzymes that are imperative in mediating the execution of the signalling cascade in regulating molecular functions and biological processes, including growth, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The human kinome comprises approximately 535 protein kinases, which can be classified into tyrosine kinases, serine/threonine kinases, and tyrosine kinase-like enzymes81. Tyrosine kinases (TKs) encompassed receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) (e.g., EGFR, FGFR, PDGFR) and non-receptor tyrosine kinases (NRTKs) (e.g., ABL, FBK, SRC). BRAF/MEK/ERK, CDKs, PI3K/AKT/mTOR are serine/threonine kinases. In living cells, a defect in cellular kinase phosphorylation can eventually lead to the constitutive activation of kinases to promote the development of malignancy and tumour progression81,82. The benzimidazole scaffold has been widely employed as a template for synthesizing kinase inhibitors (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Benzimidazole derivatives as protein kinase inhibitors.

TIBI or 4,5,6,7-tetraiodobenzimidazole is an example of an ATP-competitive inhibitor targeting protein kinase CK2 inhibitor derived from 5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole 1-β-d-ribofuranoside (DRB) scaffold83,84. The substitution of four iodine groups on the benzene ring demonstrated a better binding affinity to the CK2 ATP-binding pocket than tetrabromo and tetrachloro substitutions, which possess an IC50 value of 0.023 μmol/L83. Koronkiewicz and colleagues85 have previously reported that TIBI exerted proapoptotic and cytostatic effects on promyelocytic leukaemia cell line through inhibition of CK2 activity. Inhibition of CK2 by TIBI was then found to interfere with another protein kinase, Rio1, which is highly expressed in glioblastoma cells84. The inhibition of CK2 has been reported to negatively affect the Rio1 atypical serine kinase, resulting in the perturbation of ribosome biogenesis, cell cycle progression, and chromosome maintenance84. The specific interaction between Rio1 and CK2 resulted in the similar susceptibility of the two protein kinases to TIBI, creating another cross-link between the enzymes.

Dovitinib ((3E)-4-amino-5-fluoro-3-[5-(4-methylpiperazine-1-yl)-1,3-dihydrobenzimidazol-2-ylidene]quinolin-2-one), initially known as CHIR-258 or TKI258, is an orally bioavailable lactate salt of a benzimidazole-quinolinone compound which function as a multitargeted growth factor receptor kinase inhibitor86. Dovotinib binds to class III (FLT3/c-Kit) with IC50 of 1–2 nmol/L, class IV (fibroblast growth factor receptor 3, FGFR1/3) and class V (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, VEGFR1‒4) receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) with IC50 of 8–13 nmol/L86,87. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (SK-HEP1) cells with dovitinib resulted in G2/M phase arrest, inhibition of cell proliferation, blockage of bFGF-induced cell motility, and promoted apoptosis88. Furthermore, dovitinib potently suppressed lung tumour growth, metastasis and significantly prolonged mouse survival88. Besides, dovotinib was also found to hamper the leukaemia K562 cancer cells growth by functioning as Topo I and II inhibitors89. The FDA has recently approved Dovitinib in a premarket approval application for a companion test in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients90.

Selumetinib (ARRY-142886 or AZD6244) [6-(4-bromo-2-chloro-phenylamino)-7-fluoro-3-methyl-3H-benzimidazole-5-carboxylic acid (2-hydroxy-ethoxy)-amide], is a non-ATP-competitive, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitor targeting MEK1 and MEK2 (IC₅₀ = 14 nmol/L). The binding of Selumetinib at the MEK1/2 allosteric inhibitor binding site disrupts the interaction of both ATP and substrate and the assessment of the ERK activation loop91,92. Selumetinib can inhibit oncogenic downstream effects of the Raf-MEK-ERK signalling pathway, demonstrating potent anticancer effects in vitro and in vivo, and is currently under phase I and II trials for pancreatic cancer, melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer and differentiated thyroid cancer93, 94, 95. Although selumetinib has been investigated for the treatment of several types of cancer, it is currently approved only for the treatment of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) in paediatric patients ≥2 years who have symptomatic, inoperable plexiform neurofibromas96.

Binimetinib [5-((4-bromo-2-fluorophenyl)amino)-4-fluoro-N-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-1-methyl-1H-benzimidazole-6-carboxamide] is another non-ATP-competitive, high selectivity inhibitor toward MEK1/2 with IC50 at 12 nmol/L97,98. Remarkably, Binimetinib was highly selective, thus no off-target inhibition was detected across 220 other serine/threonine and tyrosine kinases97,98. Inhibition of the MEK1/2 led to the suppression of ERK activity which ultimately promoted cancer cell apoptosis and hampered tumour growth in tumour xenograft97,99. Binimetinib gained approval by the FDA in 2018 to be used in combination with Encorafenib to treat metastatic cutaneous melanoma with the BRAF V600E or V600K mutation98,100.

Abemaciclib [N-[5-[(4-ethylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-pyridin-2-yl]-N′-[5-fluoro-4-(7-fluoro-2-methyl-3-methylethyl-3H-benzimidazol-5-yl)-pyrimidin-2-yl]-amine] is a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor that has gained the FDA approval to be used as an adjuvant with endocrine therapy to treat breast cancers101. Abemaciclib selectively targets CDK4 (IC50: 2 nmol/L) and CDK6 (IC50:10 nmol/L) and is competitively bound to the ATP binding site of the enzymes102. Inhibition of CDK4/6 suppressed Rb phosphorylation, led to G1 arrest, and impeded cancer cell proliferation103.

Nazartinib [EGF816; (R,E)-N-(7-chloro-1-(1-[4-(dimethylamino)but-2-enoyl]azepan-3-yl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-2-yl)-2-methylisonicotinamide] is a third-generation, irreversible, mutant- selective EGFR TKI that potently targets EGFR-activating mutations104. Nazartinib comprises dimethylamino crotonamide, which is known as the optimal group for a number of covalent pan-EGFR inhibitors, a racemic 3-substituted azepane linker, and a chloro substituent at the benzene ring of the benzimidazole nucleus contribute to the better solubility, oral bioavailability, selectivity and high affinity towards EFGR105. Nazartinib suppresses the EGFR signalling and MAPK pathway, promoting cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and tumour regression in xenograft models106. Nazartinib is currently under phase I/II clinical trial in patients with EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung carcinoma104.

Compound 56q (CPL304110) was identified as a selective and potent pan-FGFR inhibitor for FGFR1, 2, 3 with IC50 of 0.75, 0.50, 3.05 nmol/L respectively, whereas IC50 of 87.90 nmol/L for FGFR4. Due to its favourable pharmacokinetic profile, low toxicity and potent antitumour activity in vivo, compound 56q is currently under evaluation in phase I clinical trial for the treatment of bladder, gastric and squamous cell lung cancers (01FGFR2018; NCT04149691)107. Compound 12n is a 6,7-dimethoxy-N-(2-phenyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-6-yl)quinolin-4-amine derivatives with para-tert-butyl substituent to the phenyl ring, targeting the c-Met tyrosine kinase with an IC50 value of 0.030 ± 0.008 μmol/L. Their findings suggested the substituent with lipophilic properties favours the inhibitory activity due to the ability to form a hydrophobic interaction with c-Met kinase. The anticancer potential of compound 12n is also well demonstrated in A549 non-small cell lung, MCF-7 breast, and MKN-45 stomach cancer cells at IC50 concentrations of 7.3 ± 1.0, 6.1 ± 0.6, and 13.4 ± 0.5 μmol/L respectively108. Compounds 18 and 27 are rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF) kinase inhibitors, with the reported IC50 values of 0.002 and 0.014 μmol/L against the B-RAFV600Eoncogenic protein is strikingly elevated in skin and colon cancers109. The RAF oncogene positively correlates with cancer cellular processes, including proliferation, invasion, metastasis and cell survival. Both compounds can inhibit the proliferation of the SK-MEL-28 melanoma cells harbouring the B-RAFV600E proteins (half-maximal effective concentration, EC50 = 4.6 and 2.3 μmol/L) to consequently inhibit the phosphorylation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Both compounds 18 and 27 possess a methyl group at the benzimidazole NH but varied in the substituent at the R2 position (4-bromo substituent in compound 18, whereas 3-(4-pyridyl) in compound 27)109. Ramurthy and colleagues demonstrated the presence of methyl group at benzimidazole NH to enhance the binding affinity towards RAF kinase compared to the unmethylated analogous. In this study, compound 27 demonstrated significant impediment of the ERK pathway, particularly in B-RAFV600E in HT29 colon mouse tumour xenograft model with an oral administration of 30 and 100 (mg/kg)/day for 28 days. However, significant body weight loss was observed as a notable side effect at a high dosage (100 mg/kg/day)109.

Compound 5a (2-chloro-N-(2-p-tolyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-5-yl)acetamide) is a 2-aryl benzimidazole which is known as a multi-target RTK inhibitor against EGFR, VEGFR-2 and PDGFR110. The presence of Part II: new candidates of pyrazole‒benzimidazole conjugates as checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) inhibitors. In a separate study by Chu and colleagues111, compound 5a was reported to block the erythroblastic leukaemia viral oncogene homologue (ErbB) full family of transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). These RTKs include the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), which are markedly over-expressed in breast cancer. In addition, compound 5a also upregulates the death receptor 5 (DR5) through the activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signalling pathway in EGFR-positive, HER2-positive and EGFR/HER2-double-negative breast cancer cells (i.e., MDA-MB-468, BT-549, MDA-MB-231, HCC1937, T-47D, BT-474, MDA-MB-453, ZR-75-1 and MCF-7 cells). Inhibition of the EFGR and HER2 expression may subsequently obstruct the downstream activation of PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK pathways. Conversely, the activation of DR5 protein expression resulted in breast cancer cell death111. Compound 8d with carbamoylhydrazone substituent was another candidate from the library of benzimidazole derivatives synthesized by Galal et al.112, acting as a checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) inhibitor to inhibit the cell cycle progression in ER + MCF7 breast, HeLa cervical, HepG2 hepatocellular cancer cell lines. In addition, the compound 8d significantly shifted the cell cycle distribution from 8% in the S phase to 51% in the G2/M phase when used in combination with doxorubicin in a breast cancer model, indicating its potency as a cytostatic agent. However, compound 8d displayed toxicity in vitro and in vivo and showed a median lethal dose (MD50) at 500 mg/kg body weight in mice.

The 1,2,3-triazolyl linked 2-aryl benzimidazole derivatives, compounds 10c (p-chlorophenyl-substituted 1,2,3-triazolyl N-isopropylamidine) and 11f (benzyl-substituted 1,2,3-triazolyl imidazoline) demonstrated remarkable anti-proliferative activity and induced apoptosis and primary necrosis in non-small cell lung cancer (A549) cells at IC50 concentrations: 0.05 and 0.07 μmol/L113. The 1,2,3-triazolyl demonstrated a high binding affinity towards different kinases and its combination with benzimidazole increased the cytostatic selectivity against non-small cell lung cancer cells. The substituent of imidazoline in compound 11f demonstrated better proliferative activity than the amidine substituent in compound 10c. The presence of PhOCH2 linker contributes to the high selectivity towards A549 cells and increased activity on CFPAC-1 and HeLa cells. Moreover, the p-substitution with ClPh further enhanced the potency of compound 10c towards A549 cells. Nevertheless, both compounds showed a remarkable reduction of sphingosine kinase 1 (SK1) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) proteins expressed in abundance in lung carcinoma. Besides, compound 11f also downregulated the cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) protein expression, delineating its function in cell cycle arrest. In silico study further confirmed their inhibition activity against p38 MAPK activities113.

1.2.2. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) inhibitors

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1), also known as poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase or poly(ADP-ribose) transferase, is a nuclear enzyme with a crucial role in executing an immediate DNA damage response (DDR) to DNA damage and promoting DNA repair. DNA damage is classified as single-strand breaks or double-strand breaks. If these damages are not repaired, chronic DDR signalling may trigger cancer cell death or cellular senescence114. Cancers of the liver, breast, skin, lung, and ovary have been reported to rely on PARP-mediated DNA repair for survival115. PARP-mediated DDR includes base excision repair (BER), mismatch repair (MMR), nucleotide excision repair (NER), non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR)116, 117, 118. PARP maintains genome integrity and facilitates cell survival119. Inhibition of PARP-1 results in genomic instability and accumulation of damaged cells in cell cycle arrest, eventually leading to apoptosis119. Synthetic lethality (SL) refers to cell death due to simultaneous deficiencies in expressing two or more genes120. SL has been detected in HR-deficient cancer cells bearing defective DDR upon inhibition of PARP115. SL can also transpire as a consequence of gene perturbation using small molecule inhibitors. For instance, PARP inhibitor has been shown to induce synthetic lethality in HR-deficient breast cancer cells harbouring the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations by exploiting the defect in DNA repair machinery in these cells. The PARP inhibitors with benzimidazole moiety are illustrated in Fig. 6.

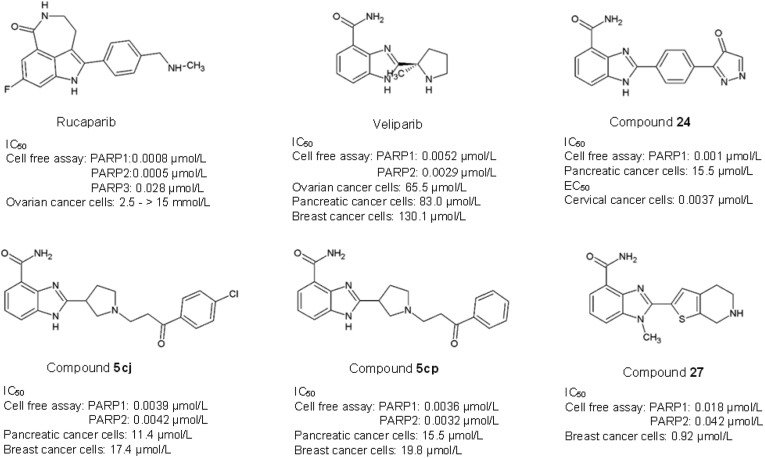

Figure 6.

Benzimidazole derivatives used as PARP inhibitor.

Many commercially available PARP inhibitors, including Olaparib, Rucaparib, Niraparib, Veliparib, and Talazoparib, are being studied in various cancer clinical trials121,122. Among them, Rucuparib and Veliparib are benzimidazole carboxamide-derived PARP inhibitors. The benzimidazole-carboxamide scaffold provides an advantage with its low molecular weight and high intrinsic potency towards the active binding site of PARP by forming hydrogen bonds and π-stacking interactions with the nicotinamide binding site of PARP-1121,123. Rucaparib (Rubraca™) is a tricyclic benzimidazole carboxamide derivative targeting PARP-1, -2, and -3 with IC50 of 0.8, 0.5 and 28 nmol/L respectively124,125. Rucaparib is the first PARP inhibitor tested in clinical trials, having entered phase III trial on solid tumour124,126, 127, 128. The FDA has approved it129 and the European Medicine Agency (EMA)130 to be used as a therapeutic agent to treat ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers, as well as advanced solid tumours with evidence of germline or somatic BRCA mutation. Veliparib (2-[(R)-2-methylpyrrolidin-2-yl]-1H-benzimidazole-4-carboxamide) has an inhibitory constant of 5.2 and 2.9 nmol/L against PARP-1 and PARP-2 respectively131. Veliparib has been tested preclinically in combination with temozolomide in a panel of tumours, including lymphoma, glioma, melanoma, colon, breast, ovarian, lung, prostate and pancreatic cancers132. Remarkably, the study revealed significant inhibition of PARP in all xenograft tumours. Veliparib is currently in phase II and phase III clinical trials for breast, lung, prostate, glioma, pancreatic, colorectal and ovarian cancers131. The relatively low molecular weight and high intrinsic potency of Veliparib have made it attractive in cancer therapy121. However, Veliparib exhibits the least potency to trap PARP-1 on DNA with relatively low cytotoxic and reduced stability of PARP‒DNA complexes in cancer cells as compared to other PARP-1 inhibitors used in the clinics (Talazoparib >> Olaparib = Rucaparib >> Veliparib)133,134.

Compounds 5cj and 5cp, also known as 2-(1-(3-(4-chloroxyphenyl)-3-oxo-propyl)pyrrolidine-3-yl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide, are PARP inhibitor synthesized using Veliparib as a template with substitution of alkyl side chain with an aromatic ring attached to the nitrogen atom in the five-member cyclic amine, and a phenyl group attached to the terminal of the side chain with the purpose to improve membrane permeability. Both compounds 5cj and 5cp displayed an inhibition potency with IC50 values at 3.9 and 3.6 nmol/L for PARP-1 as well as 4.2 and 3.2 nmol/L for PARP-2, respectively. These two compounds have demonstrated better cytotoxicity against breast and pancreatic cancer cells as compared to Veliparib and Olaparib121. The IC50 of compound 5cj towards MDA-MB-436 breast and CAPAN-1 pancreatic cancer cells are at 17.4 and 11.4 μmol/L, respectively. On the other hand, compound 5cj displayed an IC50 of 19.8 and 15.5 μmol/L against the breast and pancreatic cancer cell lines121. In an elegant study, Lee et al.123, reported compound 24, with an oxadiazole moiety at the 2-phenyl group of benzimidazole scaffold, inhibits H2O2-induced poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in C-41 cervical carcinoma cells (EC50 = 3.7 nmol/L) and exhibits an excellent in vivo oral efficacy in the B16F10 murine melanoma model. Compound 27 (6-fluoro-2-(4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[2,3-c]pyridin-2-yl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide) which contains a 4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothienopyridin-2-yl moiety and a methyl group at N1 of benzimidazole core, revealed better potency against PARP-1 and PARP-2 with the IC50 of 18 and 42 nmol/L respectively compared to other analogues135. Compound 27 was cytotoxic towards cells harbouring BRCA2 mutants with an IC50 of 0.92 μmol/L, and significantly impeded tumour growth in the BRCA-1-mutated MDA-MB-436 breast xenograft tumour model.

1.2.3. Androgen receptor (AR) antagonists

Androgen receptor (AR) is also known as nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 4 (NR3C4). It belongs to the steroid receptor family that plays an essential role in regulating gene transcription in response to testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) binding136. AR is a critical prognostic marker used commonly for diagnosing breast and prostate cancers. Approximately 53%–99% of breast cancer137 and 80%–90% of prostate cancer138 have been reported to depend on AR for tumour initiation and progression. Increased expression of AR proteins is also associated with poor response to endocrine treatment139. AR has many vital functions, including the stimulation of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) secretion, regulation of lipid metabolism, and growth promotion of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC)140. AR antagonists that disrupt the AR/SRC association can activate the human epidermal growth factor receptor (i.e., HER2, HER3) or phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), to inhibit androgen-induced cell proliferation in breast cancer141. ARs provide excellent therapeutic targets in managing estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer to prevent recurrence and spread141. However, very little is known about the use of benzimidazole-derived AR antagonists to treat cancer; hence this opens a new avenue for further investigation. Below are some benzimidazole derivatives employed in cancer research (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Benzimidazole derivatives used as androgen receptor antagonist.

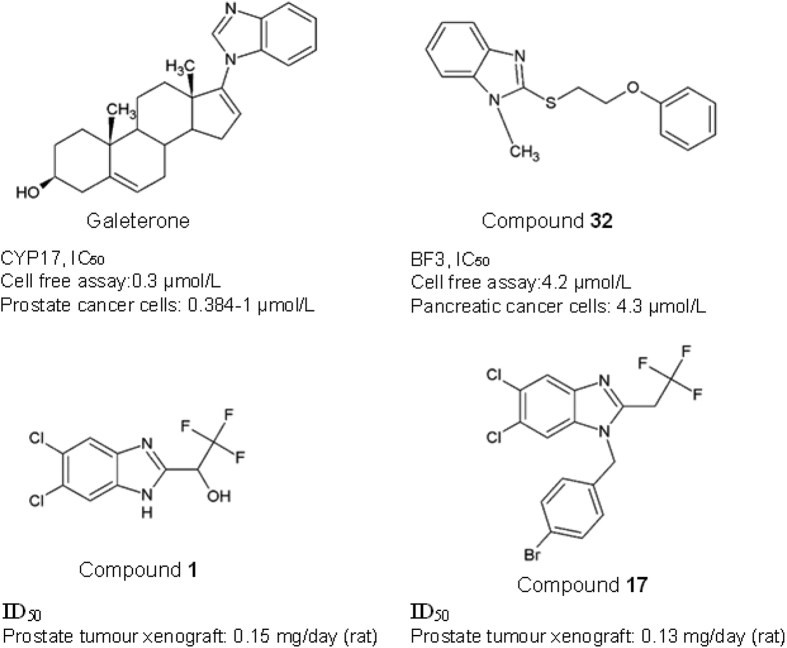

Galeterone (3β-hydroxy-17-(1H-benzimidazole-1-yl)androsta-5,16-diene) functions by blocking androgen binding to AR. Galeterone, formerly known as VN/124-1, has shown that the presence of benzimidazole moieties in the steroidal C-17 benzoazoles structure enhanced the antagonist effect against AR142,143. The anticancer effect is orchestrated through CYP17 lyase inhibition, AR antagonism, or induction of AR degradation which in turn disrupts androgen signalling144,145. Galeterone specifically targets two highly homologous deubiquitinating enzymes (i.e., USP12 and USP46). Both enzymes are implicated in the positive regulation of the AR-AKT-MDM2-p53 signalling pathway. Interestingly, treatment with Galeterone can effectively inhibit cancer cell growth in androgen-sensitive,androgen-independent anti-androgen resistant and androgen-negative prostate cancer cell lines145. With an IC50 value of 384 nmol/L in human prostate PC3AR cells, Galeterone significantly inhibited the growth of androgen-dependent LAPC4 human prostate tumour xenograft142. Galeterone was previously investigated in phase III clinical trials to investigate its efficacy in cancer patients with splice variant 7 (AR-V7) demonstrated resistance to AR treatment146,147. Regrettably, the primary endpoint of radiographic progression-free survival was not met, demonstrating a lack of clinically meaningful benefits to the patients; hence the trial was terminated by the Data Safety Monitoring Board148.

Munuganti et al.149 have synthesized a series of 2-((2-phenoxyethyl)thio)-1H-benzimidazole and 2-((2-phenoxyethyl)thio)-1H-indole, compound 32, that target the binding function 3 (BF3) protein in AR. Compound 32 is a BF3-specific inhibitor with the corresponding IC50 of 4.2 μmol/L, which causes a conformation change in the BF3 receptor. The sulphur atom in compound 32 is essential for the binding to AR receptor and inhibitory activity. The replacement of sulphur atom with other atoms such as nitrogen, carbon, sulfinyl, and sulfonyl has reduced activity and binding affinity. Besides, the presence of a methyl group at the meta-position of benzene rings enhances the ligand binding by forming a hydrophobic interaction with BF3. Compound 32 decreased prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels in LNCaP and Enzalutamide-resistant pancreatic cancer cells and Enzalutamide-resistant cell line with the reported IC50 of 4.3 μmol/L149. Compound 1 (5,6-dichloro-benzimidazole derivatives) is a hydroxyl analogue with trifluoromethyl group having demonstrated antagonistic effect in rat prostate xenograft model with ID50 = 0.15 mg/day. The 2-(2,2,2-trifluoro-ethyl)-benzimidazole 4 has shown a potent efficacy towards AR and the substitution of the OH group in compound 1 further improves the oral bioavailability (PO). The compound has a high PO (132%) and a half-life of 14.7 h150. Ng et al.151 further extended the study by synthesizing the N-substituted 2-(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)-5,6-dichloro-benzimidazoles with benzyl, N-aceto, and ethylene aryl ether group, using the 5,6-dichloro-benzimidazole scaffold. Benzyl substitution with bromine at the 4th position gave rise to the 4-bromobenzyl analogue, compound 17, which has an ID50 of 0.13 mg/day in the rat and is more potent than another known anti-androgen drug, bicalutamide. Conversely, the N-aceto and ethylene aryl ether derivatives exhibited no improvement in the antagonistic activity in prostate cancer cells.

1.2.4. Aromatase inhibitors

Aromatase is a cytochrome P450 (CYP19A1) enzyme that synthesises estrogen from either androstenedione or testosterone152,153. Aromatase was overexpressed in breast cancer and fuel the tumour progression and metastasis in estrogen receptor-α (ERα) positive breast cancers153. Aromatase inhibitors lower estrogen levels by halting the enzyme activity of aromatase in estrogen biosynthesis154. Therefore, aromatase inhibition is one of the effective current therapeutic strategies for controlling estrogen-dependent breast cancer (Fig. 8i).

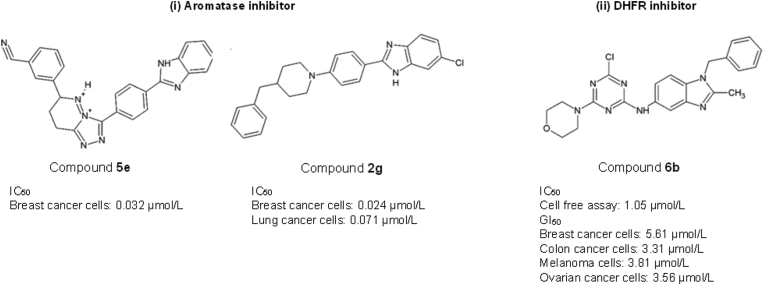

Figure 8.

Benzimidazole derivatives as (i) aromatase inhibitor and (ii) dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitor.

A library of benzimidazole-triazolothiadiazine derivatives has been synthesized and exhibited aromatase inhibition activities155. Among the compounds, compound 5e revealed the potent inhibitory effect of aromatase with an IC50 of 0.032 μmol/L in breast cancer cells155. Compound 5e carries a 4-cyanophenyl substituent at the fourth position of the phenyl ring, which contributes to its inhibitory activity155. Another potent aromatase inhibitor, a 4-benzylpiperidine derivative: compound 2g inhibits aromatase and exhibits cytotoxic effects against breast and lung cancer cells with an IC50 of 0.024 and 0.071 μmol/L, respectively156. The presence of chlorine substituent on the benzene ring enhanced the interaction with the aromatase active site by forming a halogen bond with the Gln215 amino group within the enzyme156.

1.2.5. Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitors

Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) is a metabolic enzyme that regulates cell proliferation by catalysing the reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate by NADPH to produce active folate required for the de novo synthesis of purines, amino acids, and thymidylate (TMP)157. The up-regulation of DHFR has been described in different cancers, for example, human glioma158, ovarian159, and acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)160. High DHFR expression is also associated with poor survival and drug resistance159,160. Inhibition of DHFR debilitates tetrahydrofolate production, which subsequently affects cell growth and proliferation, and ultimately drives cell death in various cancers including leukaemia, osteosarcoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and lung cancer157.

Compound 6b from Singla et al.161 is the most active DHFR inhibitor with an IC50 of 1.05 μmol/L (Fig. 8ii). It is a regioisomeric hybrid of s-triazine and benzimidazole moieties, substituting primary and secondary amines. Compound 6b harbours nucleophilic displacement at the primary and secondary amines. This attribute enhances its anticancer effects with a median growth inhibition (GI50) in the range of 3.31–5.61 μmol/L in melanoma, colon, breast, and ovarian cancer cells. Besides performing as a DHFR inhibitor, compound 6b has also displayed a strong DNA interaction, showing its potential to act as a DNA intercalator161.

1.3. Epigenetic modulators

Cancer is a consequence of accumulative genetic mutations in concert with epigenetic alterations that lead to alteration in various cellular events, including cell proliferation, invasion, senescence, and apoptosis162,163. Epigenetic heterogeneity in the tumour could also lead to various diagnostic and treatment outcomes even in cancer patients with the same tumour stage and grade. However, the application of benzimidazole moiety in the development of epigenetic regulators, is scarce. Here we report the reported application of benzimidazole moiety as histone deacetylases (HDACs) and demethylase inhibitors (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Benzimidazole derivatives used as epigenetic modulator.

HDACs describe a group of histone-silencing enzymes that remove the acetyl group from histones, and maintain the steady-state level of lysine acetylation level of histone and non-histone proteins164. HDACs are implicated in gene silencing transcription repression, in which the aberrant expression may lead to malignancy165,166. HDAC can be divided into four classes comprising class I HDACs (yeast Rpd3-like proteins: HDAC1‒3, and HDAC8), class II HDACs with a single deacetylase domain at the C-terminus (yeast Hda1-like proteins: HDAC4‒7, and HDAC9‒10), class 3 HDACs (yeast silent information regulator 2 (Sir2)-like proteins: Sirtuin 1‒7), and class IV (HDAC11)162. Given the potent antitumour effects of HDAC inhibitors (HDACi) to reverse the epigenetic changes in cancer by restoring the balance of histone acetylation164. HDACi, thus, is a potent inducer of growth arrest and apoptosis and inhibit the differentiation of malignant cells167.

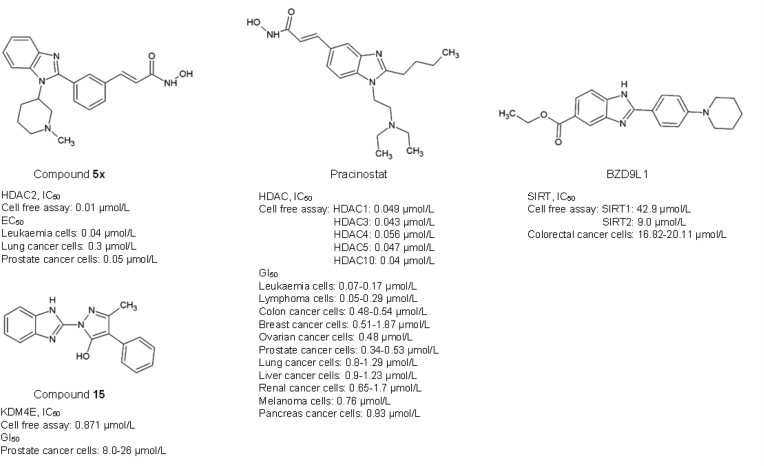

Compound 5x is an HDAC2 inhibitor, one of the N-hydroxy-3-[3-(1-substituted-1H-benzoimidazol-2-yl)-phenyl]-acrylamide analogues, which displayed effective anticancer activities in vitro and in vivo in nanomolar range31. Compound 5x induced the hyperacetylation of histone H3 and H4 as well as p21 activity, which led to tumour suppression in HCT116 colorectal cancer and PC3 prostate xenograft models31. Pracinostat (SB939) dialkyl benzimidazole competitive histone deacetylase inhibitor targeting Class I, II and IV HDACs168. Combination treatment of Pracinostat with azacytidine has shown synergistic effects against acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) in phase II clinical trial, with reported tolerable safety and efficacy. However, common adverse effects such as infection, thrombocytopenia and febrile neutropenia were present in patients169. Regrettably, the phase III clinical trial of Pracinostat with azacytidine in AML was discontinued because the treatment outcome was unlikely to meet the primary endpoint of overall survival170.

Sirtuins are a family of class III histone deacetylases which rely on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to function171,172. Sirtuin 1‒7 perform mainly as lysine deacetylase and/or mono-ADP-ribosyltransferase on both histone and non-histone proteins173,174. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated the crucial role of sirtuin in cancer initiation and progression, thereby making sirtuins a target of interest in anticancer therapy173,175, 176, 177, 178. BZD9L1 is a newly discovered sirtuin inhibitor with auto-fluorescence and anticancer properties (Fig. 7)179. BZD9L1 is a diversified 1,2-disubstituted benzimidazole analogue targeting both SIRT1 (IC50: 42.9 μmol/L) and SIRT2 (IC50: 9 μmol/L) proteins but showed higher inhibitory potency towards SIRT2 protein179. The substitution of the piperidinyl group, which is a fundamental and strong electron-donating side chain, at the phenyl ring builds the foundation for SIRT inhibitory activity. This piperidinyl side-chain stabilises the benzimidazole moiety and allows a stronger interaction with the active site of SIRT protein179. BZD9L1 has demonstrated comparable SIRT1 and/or SIRT2 inhibitory effects to commercially available sirtuin inhibitors such as AGK-2, EX527, and Tenovin-6. A functional study by Tan et al. has revealed its anticancer capabilities either as stand-alone or in combination with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), the first-line chemotherapy for colorectal cancer, in vitro and in vivo32,33. Tan and colleagues have also reported the ability of BZD9L1 to impede colorectal cancer cell viability, proliferation, migration, invasion, and induce apoptosis in vitro at the IC50 concentration of 16.82 and 20.11 μmol/L in HCT116 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cell lines respectively32. Combining BZD9L1 with 5-FU further enhanced the treatment efficiency by hindering colorectal tumour growth through increased cell survival, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, senescence and micronucleated33. Furthermore, BZD9L1 was predicted to modulate the p53-dependent signalling pathways to exert cell death in CRC cells180.

DNA demethylation removes the methyl group from cytosine by ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenases (TET) to produce 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine through the oxidation process181. The histone lysine demethylase (KDM) subfamily contains the catalytic Jumanji C domain and utilizes Fe2+ as a cofactor and α-ketoglutarate [α-KG or 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)] as a co-substrate to remove methyl groups from histone lysine residues34,182. KDMs are overexpressed in various cancers, including breast, prostate, pancreatic, lung, colorectal, liver, glioma, gynaecological, oesophageal and lymphatic cancers, resulting unaggressive phenotypes34,183,184. Compound 15 is a benzimidazole pyrazole-based inhibitor of recombinant lysine demethylase 4E (KDM4E), modified from its parental structure CBN209350 by introducing a non-polar aromatic ringside chain at the scaffold R2 position, that resulted in 10-fold improved potency relative to the original HTS hit34. Crystallography data showed that compound 15 competes with the enzyme for Fe2+ binding leading to the removal of active-site iron, thereby inhibiting KDM4E activity. Treatment of LnCaP and DU145 prostate cancer cells with compound 15 also revealed a significant reduction of the H3K9me3 compared to untreated cells34.

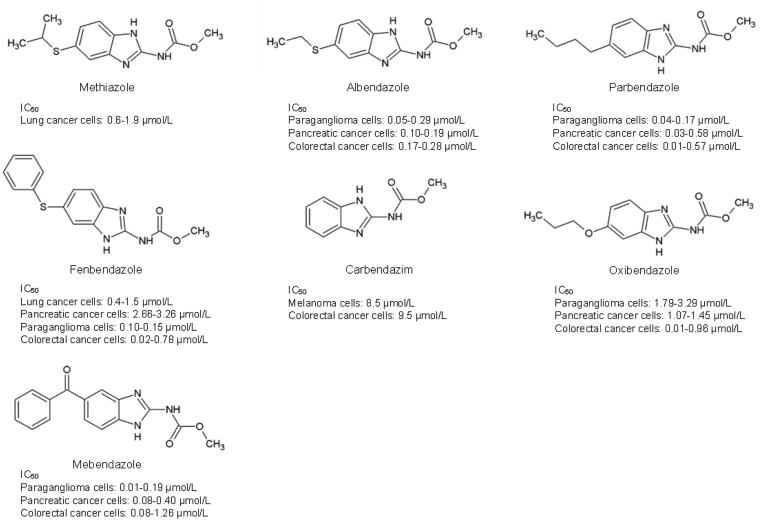

2. Repurposing FDA-approved benzimidazole-derived drugs for cancer treatment

Drug repositioning is a valuable alternative strategy in drug discovery due to establishing well-documented pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, and safety profiles of drug candidates, which may speed up the traditional process of approval and utilization in clinics185. Intriguingly, many benzimidazole anthelmintic drugs have been reprofiled as anticancer agents; these examples include fenbendazole (FBZ), carbendazim (CBZ), oxibendazole, mebendazole (MBZ), albendazole (ABZ), and parbendazole (Fig. 10)185,186. For instance, FBZ, and MBZ possess the ability to bind with the colchicine binding site, which can lead to the reduction of angiogenesis and multidrug-resistance in cancer cells187,188. Moreover, parbendazole, oxibendazole, FBZ and MBZ have also reduced pancreatic cancer cell viability in the nanomolar range189. Furthermore, Parbendazole possesses a linear alkylic side-chain that provides a strong antiproliferative benefit and results in the drastic inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell growth, survival, migration and induced DNA damage response, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis189. In addition, combination treatment of parbendazole with gemcitabine also enhanced the treatment effects in pancreatic cancer cell lines189.

Figure 10.

Repurposed benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents.

An investigation of the anticancer activities of these compounds on Kirsten rat sarcoma 2 viral oncogene homolog (KRAS)-wildtype and KRAS-mutant lung cancer in vitro and in vivo has revealed that lung cancer cells harbouring the KRAS mutation showed increased sensitivity towards benzimidazole derivatives. Methiazole and FBZ were used as TK inhibitors and showed enhanced inhibitory effects on KRAS-mutant lung cancer model in vitro and in vivo, inhibiting RAS signalling-related TK and suppressing the PI3K/AKT and RAF/MEK/ERK pathway, causing inhibition of proliferation and inhibition of apoptosis30. From the study, methiazole was cytotoxic towards cancer cell lines harbouring KRAS mutation with an IC50 of 1.9 and 0.6 μmol/L in A549 and H23 lung cancer cells, respectively, while an IC50 > 40 μmol/L was reported in KRAS wildtype cancer cells, without affecting the normal lung epithelial cells. On the other hand, FBZ exhibited higher sensitivity in KRAS mutant than KRAS wildtype cells (i.e., IC50 in KRAS-mutant A-549: 1.5 μmol/L; H-23: 0.4 μmol/L, and KRAS-wildtype: H-1650: 6.2 μmol/L, H-2228: 7.8 μmol/L) but slightly cytotoxic towards normal lung epithelial cells30.

Methyl 2-benzimidazolecarbamate (CBZ) is a well-known fungicide with a high binding affinity toward mammalian tubulin (Kd, 42.8 ± 4.0 μmol/L) in the MCF7 human breast cancer cells190. CBZ has also been highlighted to hamper cell proliferation in B16 melanoma (IC50 = 8.5 μmol/L) and HT-29 colon carcinoma (IC50 = 9.5 μmol/L) cell lines191. The anticancer potential of CBZ has also been shown to extend to the human breast (MCF-7, MX-1), pancreas (Panc-1, MiaPaCa), colon (ht-29), lung (A549, SK-MES), prostate (DU145), and murine (B16, p388) tumour models191,192. CBZ functions by interfering with the formation of microtubules to instigate cell cycle arrest and apoptosis191,192. CBZ was reported to have no interaction with the colchicine binding site but suppressed the spindle microtubule dynamic at interphase, resulting in mitotic arrest and cancer cell death190. Another popular benzimidazole-derived veterinary drug, FBZ (methyl N-(6-phenylsulfanyl-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl) carbamate) can induce microtubule depolymerising activity in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells, ensuing in early G2/M arrest accompanied by p53-mediated cell death in both in vitro and in vivo studies72. In addition, oral treatment of FBZ in lung cancer xenografts demonstrated tumour vascularisation reduction and tumour growth inhibition72. Furthermore, FBZ has been shown to interfere with cellular microtubule polymerisation-impeded lymphoma tumour growth in vivo when used in combination with supplemented vitamins193.

MBZ demonstrated a wide range of anticancer mechanisms by inhibiting tubulin polymerization, angiogenesis, pro-survival pathways, matrix metalloproteinases, and multi-drug resistance protein transporters in various cancer cell lines and xenograft models, which is extensively reviewed by Guerini and colleagues194. However, MBZ has demonstrated low toxicity but possesses poor oral bioavailability (17%–20% of the dose absorption)194. There is no evidence of MBZ in a clinical trial for cancer treatment, but many studies on MBZ alone or in combination treatments have been registered for anticancer clinical trials194.

Both ABZ and FBZ work well as antimitotic agents and regulators of ATP production72,195, 196, 197, and have therefore been repositioned as anticancer candidates. ABZ has been reported to hinder cell proliferation in leukaemia, and breast, ovarian and liver malignancies198, 199, 200. In addition, the role of ABZ in driving cells towards intrinsic apoptosis in Epothilone-paclitaxel resistant leukemic cells has been documented. The mechanism contributing to this event was the upregulation of cleaved caspase-3 and cytochrome C, and the downregulation of BCL-2 anti-apoptotic proteins tightly controlled by the p53 cellular gatekeeper201. A recent study by Castro et al.200, also reported that ABZ could suppress breast cancer cell proliferation in vitro, and trigger p53-dependent apoptosis in mouse Ehrlich mammary tumour cells in vivo. Another study by Dogra and colleagues72 reported that FBZ could disrupt microtubule dynamics through p53 activation in vitro and in vivo in human NSCLC cells. These findings corroborate the latest study by Mrkvová and colleagues202, in which the inhibition of MDM2 and MDMX by ABZ and FBZ eventually led to p53 activation. In this study, Mrkvová et al.203 highlighted the ability of ABZ and FBZ to inhibit MDM2 and MDMX, through which a subsequent increase in p53 protein (by 2.5 and 1.3-folds respectively) was observed. MDM2 and MDMX are known as p53 regulators, which negatively regulate and abrogate p53 activities by promoting p53 proteasome-mediated degradation. The inhibition of p53 prevents cancer cells from cell cycle arrest and thus promotes cell survival.

3. Conclusions and future perspectives

Benzimidazole is a promising compound for anticancer either through target-specific or non-oncogene-specific targeting. Numerous benzimidazole-derived drugs have recently gained approval by the FDA, delineating the remarkable potential of benzimidazole scaffolds to be employed as anticancer agents. The advancement of science and technology has revolutionized healthcare and necessitated the development of more precise targeted drugs. The emergence of benzimidazole-derived PARP inhibitor: Rucaparib was redefined and approved by the FDA as one of the personalized medicines in 2020204. With the unique structure of benzimidazole core that exhibits a broad spectrum of bioactivities, it could potentially mimic naturally occurring nucleotides to interrupt biological processes in cancer and thereby potentially hijack multiple cellular processes at any one time. The enormous literature on the imperative roles of benzimidazole derivatives in targeting cancers also supports the use of benzimidazole scaffold in the transition from conventional to precision medicine.

Cancers are associated with multiple dysfunctions in genes or proteins in which multitargeted drugs may have an added advantage over non-target-specific drugs. Some benzimidazole drugs have been shown to target multiple biomarkers, which may improve the treatment response and result in the synergistic impediment of tumour growth. Although evidence has acknowledged the promising outcomes of multi-targeted therapies, the underlying possibility of inducing antagonist effect on tumour progression and off-target toxicity cannot be ruled out. Additional downstream analyses need to be undertaken to investigate further the molecular mechanism and pathway in vitro and in vivo. Inevitably, problems like toxicity, drug-resistant and poor bioavailability have become the limiting factors in the development of small molecules in general. Thus, lead optimization is needed to generate drug candidates that are highly specific, less toxic, and with improved bioavailability. Due to the exorbitant costs in drug discovery and development, it may be reasonable to repurpose the currently available benzimidazole drugs to be developed in the cancer field as increasing evidence has demonstrated the therapeutic switching of benzimidazole drugs used to treat other diseases to demonstrate anticancer effects. This review could provide insight into the broad application of benzimidazole in targeting cancer, which may open up new avenues for benzimidazole anticancer drug development toward precision medicine.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia for the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme with the Project Code: FRGS/1/2021/SKK06/USM/02/7 for supporting this work. We would also like to thank Lim Wei Khei from the School of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences at Curtin University, Australia, for proofreading the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Yeuan Ting Lee drafted the manuscript. Yi Jer Tan performed the structural analysis for ligand-target interaction. Chern Ein Oon reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Hodson R. Precision medicine. Nature. 2016;537:S49. doi: 10.1038/537S49a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright J.B. The chemistry of the benzimidazoles. Chem Rev. 1951;48:397–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keri R.S., Hiremathad A., Budagumpi S., Nagaraja B.M. Comprehensive review in current developments of benzimidazole-based medicinal chemistry. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2015;86:19–65. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh P.K., Silakari O. In: Key heterocycle cores for designing multitargeting molecules. Silakari O., editor. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2018. Benzimidazole: journey from single targeting to multitargeting molecule. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitaku E., Smith D.T., Njardarson J.T. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J Med Chem. 2014;57:10257–10274. doi: 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaba M., Mohan C. Development of drugs based on imidazole and benzimidazole bioactive heterocycles: recent advances and future directions. Med Chem Res. 2016;25:173–210. [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-masry H.A., Fahmy H.H., Ali Abdelwahed H.S. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of some new benzimidazole derivatives. Molecules. 2000;5:1429–1438. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ansari K.F., Lal C. Synthesis, physicochemical properties and antimicrobial activity of some new benzimidazole derivatives. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44:4028–4033. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padalkar V.S., Borse B.N., Gupta V.D., Phatangare K.R., Patil V.S., Umape P.G., et al. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of novel 2-substituted benzimidazole, benzoxazole and benzothiazole derivatives. Arab J Chem. 2016;9:S1125–S1130. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tahlan S., Kumar S., Ramasamy K., Lim S.M., Shah S.A.A., Mani V., et al. Design, synthesis and biological profile of heterocyclic benzimidazole analogues as prospective antimicrobial and antiproliferative agents. BMC Chemistry. 2019;13:50. doi: 10.1186/s13065-019-0567-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar K., Awasthi D., Lee S.Y., Zanardi I., Ruzsicska B., Knudson S., et al. Novel trisubstituted benzimidazoles, targeting Mtb FtsZ, as a new class of antitubercular agents. J Med Chem. 2011;54:374–381. doi: 10.1021/jm1012006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon Y.K., Ali M.A., Choon T.S., Ismail R., Wei A.C., Kumar R.S., et al. Antituberculosis: synthesis and antimycobacterial activity of novel benzimidazole derivatives. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/926309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai N.C., Shihory N.R., Kotadiya G.M., Desai P. Synthesis, antibacterial and antitubercular activities of benzimidazole bearing substituted 2-pyridone motifs. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;82:480–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou R., Ayres K.R., Drach J.C., Townsend L.B. Synthesis and antiviral evaluation of certain disubstituted benzimidazole ribonucleosides. J Med Chem. 1996;39:3477–3482. doi: 10.1021/jm960157v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tonelli M., Simone M., Tasso B., Novelli F., Boido V., Sparatore F., et al. Antiviral activity of benzimidazole derivatives. Ii. Antiviral activity of 2-phenylbenzimidazole derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:2937–2953. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vausselin T., Séron K., Lavie M., Mesalam A.A., Lemasson M., Belouzard S., et al. Identification of a new benzimidazole derivative as an antiviral against hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2016;90:8422. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00404-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noor A., Qazi N.G., Nadeem H., Khan A.U., Paracha R.Z., Ali F., et al. Synthesis, characterization, anti-ulcer action and molecular docking evaluation of novel benzimidazole‒pyrazole hybrids. Chem Cent J. 2017;11:85. doi: 10.1186/s13065-017-0314-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radhamanalan R., Alagumuthu M., Nagaraju N. Synthesis and drug efficacy validations of racemic-substituted benzimidazoles as antiulcer/antigastric secretion agents. Future Med Chem. 2018;10:1805–1820. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arora R.K., Kaur N., Bansal Y., Bansal G. Novel coumarin-benzimidazole derivatives as antioxidants and safer anti-inflammatory agents. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2014;4:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma R., Bali A., Chaudhari B.B. Synthesis of methanesulphonamido-benzimidazole derivatives as gastro-sparing antiinflammatory agents with antioxidant effect. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27:3007–3013. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Can N.Ö., Çevik U.A., Sağlık B.N., Özkay Y., Atlı Ö., Baysal M., et al. Pharmacological and toxicological screening of novel benzimidazole-morpholine derivatives as dual-acting inhibitors. Molecules. 2017;22:1374. doi: 10.3390/molecules22081374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shingalapur R.V., Hosamani K.M., Keri R.S., Hugar M.H. Derivatives of benzimidazole pharmacophore: synthesis, anticonvulsant, antidiabetic and DNA cleavage studies. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:1753–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Bakri Y., Anouar E.H., Marmouzi I., Sayah K., Ramli Y., El Abbes Faouzi M., et al. Potential antidiabetic activity and molecular docking studies of novel synthesized 3.6-dimethyl-5-oxo-pyrido[3,4-f][1,2,4]triazepino[2,3-a]benzimidazole and 10-amino-2-methyl-4-oxo pyrimido[1,2-a]benzimidazole derivatives. J Mol Model. 2018;24:179. doi: 10.1007/s00894-018-3705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y., Xu J., Li Y., Yao H., Wu X. Design, synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of novel no-releasing benzimidazole hybrids as potential antihypertensive candidate. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2015;85:541–548. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torres-Gómez H., Hernández-Núñez E., León-Rivera I., Guerrero-Alvarez J., Cedillo-Rivera R., Moo-Puc R., et al. Design, synthesis and in vitro antiprotozoal activity of benzimidazole-pentamidine hybrids. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:3147–3151. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toro P., Klahn A.H., Pradines B., Lahoz F., Pascual A., Biot C., et al. Organometallic benzimidazoles: synthesis, characterization and antimalarial activity. Inorg Chem Commun. 2013;35:126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okombo J., Brunschwig C., Singh K., Dziwornu G.A., Barnard L., Njoroge M., et al. Antimalarial pyrido[1,2-a]benzimidazole derivatives with mannich base side chains: synthesis, pharmacological evaluation, and reactive metabolite trapping studies. ACS Infect Dis. 2019;5:372–384. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamanna K. In: Chemistry and applications of benzimidazole and its derivatives. Marinescu M., editor. IntchOpen; London: 2019. Synthesis and pharmacological profile of benzimidazoles. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shrivastava N., Naim M.J., Alam M.J., Nawaz F., Ahmed S., Alam O. Benzimidazole scaffold as anticancer agent: synthetic approaches and structure–activity relationship. Arch Pharmazie. 2017;350 doi: 10.1002/ardp.201700040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimomura I., Yokoi A., Kohama I., Kumazaki M., Tada Y., Tatsumi K., et al. Drug library screen reveals benzimidazole derivatives as selective cytotoxic agents for KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;451:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bressi J.C., Jong Rd, Wu Y., Jennings A.J., Brown J.W., O'Connell S., et al. Benzimidazole and imidazole inhibitors of histone deacetylases: synthesis and biological activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:3138–3141. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan Y.J., Lee Y.T., Yeong K.Y., Petersen S.H., Kono K., Tan S.C., et al. Anticancer activities of a benzimidazole compound through sirtuin inhibition in colorectal cancer. Future Med Chem. 2018;10:2039–2057. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2018-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan Y.J., Lee Y.T., Petersen S.H., Kaur G., Kono K., Tan S.C., et al. BZD9L1 sirtuin inhibitor as a potential adjuvant for sensitization of colorectal cancer cells to 5-fluorouracil. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11 doi: 10.1177/1758835919878977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter D.M., Specker E., Małecki P.H., Przygodda J., Dudaniec K., Weiss M.S., et al. Enhanced properties of a benzimidazole benzylpyrazole lysine demethylase inhibitor: mechanism-of-action, binding site analysis, and activity in cellular models of prostate cancer. J Med Chem. 2021;64:14266–14282. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haider K., Yar M.S. In: Benzimidazole. Kendrekar P., Adimule V., editors. IntechOpen; London: 2022. Advances of benzimidazole derivatives as anticancer agents: bench to bedside. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Champoux J.J. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lodish H., Berk A., Zipursky S.L., Matsudaira P., Baltimore D., Darnell J. In: DNA topoisomerase protocols: Volume II: enzymology and drugs. Osheroff N., Bjornsti M.A., editors. Humans Press; Totowa: 2001. The role of topoisomerases in DNA replication. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McClendon A.K., Osheroff N. DNA topoisomerase ii, genotoxicity, and cancer. Mutat Res. 2007;623:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delgado J.L., Hsieh C.M., Chan N.L., Hiasa H. Topoisomerases as anticancer targets. Biochem J. 2018;475:373–398. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bielawski K., Wolczynski S., Bielawska A. Inhibition of DNA topoisomerase i and ii, and growth inhibition of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells by bis-benzimidazole derivatives with alkylating moiety. Pol J Pharmacol. 2004;56:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oksuzoglu E., Tekiner-Gulbas B., Alper S., Temiz-Arpaci O., Ertan T., Yildiz I., et al. Some benzoxazoles and benzimidazoles as DNA topoisomerase i and ii inhibitors. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem. 2008;23:37–42. doi: 10.1080/14756360701342516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hegde M., Kumar K.S.S., Thomas E., Ananda H., Raghavan S.C., Rangappa K.S. A novel benzimidazole derivative binds to the DNA minor groove and induces apoptosis in leukemic cells. RSC Adv. 2015;5:93194–93208. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao C., Li B., Zhang B., Sun Q., Li L., Li X., et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of benzimidazole acridine derivatives as potential DNA-binding and apoptosis-inducing agents. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:1800–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li P., Zhang W., Jiang H., Li Y., Dong C., Chen H., et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of benzimidazole–rhodanine conjugates as potent topoisomerase ii inhibitors. MedChemComm. 2018;9:1194–1205. doi: 10.1039/c8md00278a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gromiha M.M., Nagarajan R. In: Protein interactions: computational methods, analysis and applications. Gromiha M.M., editor. Danvers: World Scientific Publishing; 2020. Computational approaches for predicting the binding sites and understanding the recognition mechanism of protein–DNA complexes. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bhaduri S., Ranjan N., Arya D.P. An overview of recent advances in duplex DNA recognition by small molecules. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2018;14:1051–1086. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.14.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong K.C. A novel approach to predict core residues on cancer-related DNA-binding domains. Cancer Inf. 2016;15:1–7. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S39366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thirumal Kumar D., Mendonca E., Priyadharshini Christy J., George Priya Doss C., Zayed H. In: Advance in protein chemistry and structural biology. Donev R., editor. Elsevier; 2019. A computational model to predict the structural and functional consequences of missense mutations in O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goftar M.K., Kor N.M., Kor Z.M. Dna intercalators and using them as anticancer drugs. Int J Adv Biol Biom Res. 2014;2:811–822. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soni A., Khurana P., Singh T., Jayaram B. A DNA intercalation methodology for an efficient prediction of ligand binding pose and energetics. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:1488–1496. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waring M.J. DNA modification and cancer. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:159–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]