This study evaluates trends in outcomes of women undergoing coronary artery bypass in the US from 2011 to 2020.

Key Points

Question

Have operative outcomes in women undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) improved from 2011 to 2020?

Findings

In this cohort study of more than 1 million patients, women had a higher operative mortality and incidence of the composite of operative mortality and morbidity compared with men. The attributable risk of female sex for operative mortality varied from 1.28 in 2011 to 1.41 in 2020, with no significant change over the study period and the attributable risk for the composite of operative mortality and morbidity was 1.08 in both 2011 and 2020 with no significant change over the study period.

Meaning

Women remain at significantly higher risk for adverse outcomes following CABG with no significant improvement over the last decade.

Abstract

Importance

It has been reported that women undergoing coronary artery bypass have higher mortality and morbidity compared with men but it is unclear if the difference has decreased over the last decade.

Objective

To evaluate trends in outcomes of women undergoing coronary artery bypass in the US from 2011 to 2020.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study at hospitals contributing to the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons included 1 297 204 patients who underwent primary isolated coronary artery bypass from 2011 to 2020.

Exposure

Coronary artery bypass.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was operative mortality. The secondary outcome was the composite of operative mortality and morbidity (including operative mortality, stroke, kidney failure, reoperation, deep sternal wound infection, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and prolonged hospital stay). The attributable risk (the association of female sex with coronary artery bypass grafting outcomes) for the primary and secondary outcomes was calculated.

Results

Between 2011 and 2020, 1 297 204 patients underwent primary isolated coronary artery bypass grafting with a mean age of 66.0 years, 317 716 of which were women (24.5%). Women had a higher unadjusted operative mortality (2.8%; 95% CI, 2.8-2.9 vs 1.7%; 95% CI, 1.7-1.7; P < .001) and overall unadjusted incidence of the composite of operative mortality and morbidity compared with men (22.9%; 95% CI, 22.7-23.0 vs 16.7%; 95% CI, 16.6-16.8; P < .001). The attributable risk of female sex for operative mortality varied from 1.28 in 2011 to 1.41 in 2020, with no significant change over the study period (P for trend = 0.38). The attributable risk for the composite of operative mortality and morbidity was 1.08 in both 2011 and 2020 with no significant change over the study period (P for trend = 0.71).

Conclusions and Relevance

Women remain at significantly higher risk for adverse outcomes following coronary artery bypass grafting and no significant improvement has been seen over the course of the last decade. Further investigation into the determinants of operative outcomes in women is urgently needed.

Introduction

Background/Rationale

Every year in the US more than 370 000 patients undergo coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and of them approximately 30% are women.1 Women are referred for surgery at an older age than men and with a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, including diabetes, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and dyslipidemia.2,3 Women also present more frequently with heart failure or in nonelective settings, such as cardiogenic shock or acute myocardial infarction.2,3 It is also well documented that women undergoing CABG experience significantly higher observed operative mortality compared with men2 and are at increased risk of major postoperative adverse events, including myocardial infarction and stroke.4 These differences persist despite adjustment for differences in baseline risk factors.3,5

On a national scale, the outcomes of CABG surgery have generally improved significantly over the past decades despite an increase in the risk profile of patients referred for surgery.6,7 It is not known, however, whether the above-mentioned CABG outcomes gap between women and men has been mitigated or removed over the past decade.

Objective

Our objective was to evaluate trends in the outcomes of women undergoing isolated CABG surgery in the US during the last decade. We used data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Adult Cardiac Surgery Database (ACSD).

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective cohort study based on the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons was approved by the institutional review board at Weill Cornell Medicine, which waived the need for individual patient consent. This study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.8

Setting

The data for this study were provided through the STS Participant User File (PUF) research program. Versions 2.73, 2.81, and 2.9 of the STS-ACSD were queried for all patients in the US undergoing primary isolated CABG from July 2011 to June 2020.

Population

Patients were included in the analysis if they underwent primary isolated CABG during the study period. Patients requiring resuscitation prior to surgery, emergent/salvage operations, and reoperation were excluded. Data were analyzed by sex.

Data Collection

The STS-ACSD is a voluntary prospectively maintained and audited database that has been previously described.9 In brief, the STS-ACSD collected data from over 1100 participating centers across the US in addition to other international participants and represents over 95% of the US cardiac surgical volume.10 STS PUF data are deidentified of personal health information and analyzed in compliance with the STS PUF Research Program. Details on data collection and quality control methods in the STS Database are provided in the eMethods in the Supplement.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was operative mortality defined as in-hospital death anytime during index hospitalization or within 30 days of CABG after discharge. The secondary outcome was the composite of operative mortality and morbidity, including operative mortality, stroke, kidney failure, reoperation, deep sternal wound infection, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and prolonged hospital stay. For all the outcomes, the STS definitions were used (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Patients with unknown operative mortality status were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical Analyses

The Anderson-Darling normality test was used to assess whether continuous variables were normally distributed. As they were all nonnormally distributed, continuous variables were reported as median and IQR and compared between groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data were reported as frequency counts and percentages and compared using the χ2 test. The patient demographics, risk factors, payer data, cardiovascular data, and surgical priority data fields used for risk adjustment are those included in the 2018 STS Risk Model (eTable 2 in the Supplement).11,12

The primary analytic method to estimate the association of female sex with CABG operative outcomes over time was to derive the attributable risk of female sex for the primary and secondary outcome derived for each calendar year. This was accomplished as follows: first, for each year over the study period, we fit a multivariable logistic regression model for each outcome using only male patients; second, we used the male-based model coefficients to calculate the predicted risk for each female patient from that year; and third, we estimated the year-specific risk attributable to female sex (attributable risk [AR]) as the resulting ratio of observed rate to expected rate ratio for each outcome based on female patients only. Here, since the model was based on male patients, the ratio (year; male) will always be equal to 1 by definition. In such instance, an AR (female) more than 1 can be interpreted as the attributable added risk for women compared with men. Alternatively, an AR (female) less than 1 can be interpreted as an attributable reduced risk for women compared with men. Importantly, this modeling approach excludes patient sex as a covariate, as well excludes interaction-term covariates involving female sex, body surface area, and preoperative hematocrit levels.9,10

As a confirmatory analysis, the 2018 STS risk models, inclusive of all model parameters,11 were calculated using multivariable mixed logistic regression model with hospital identifier as a random effect for the primary and secondary outcomes for each year. The adjusted β coefficients and corresponding adjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI for women were then quantified. The trends over the past decade for both the AR and OR for women were plotted and the P for trend was calculated using linear regression.

Missing covariates were handled using a simple single imputation strategy. Values were imputed to the most common category of binary or categorical variables and to the median or subgroup-specific median of continuous variables. This single imputation approach was previously validated for the 2008 STS risk models by demonstrating that coefficients and predicted risk estimates obtained using single imputation were similar to the gold standard of multiple imputation.12 Missing data are summarized in eTable 3 in the Supplement. Two-sided significance testing was used and a P value for significance was set at .05 without adjustment for multiple testing. All analyses were performed using R version 4.1.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing) within RStudio.

Results

Participants

Between 2011 and 2020, 1 297 204 patients underwent primary isolated CABG and met the inclusion criteria. Of them, 317 716 were women (24.5%). The proportion of women decreased from 26.2% in 2011 to 22.7% in 2020 (P for trend <.001) (eTable 4 and eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Descriptive Data

Key baseline preoperative characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Women were older (67 [IQR, 60-74] years, vs 65 [IQR, 58-72] years; P < .001) and had a higher incidence of hypertension (91.9%; 95% CI, 91.8-92.0 vs 88.4%; 95% CI, 88.3-88.5; P < .001), diabetes (56.3%; 95% CI, 56.2-56.5 vs 46.2%;95% CI, 46.1-46.3; P < .001), chronic lung disease (29.0%; 95% CI, 28.8-29.1 vs 24.4; 95% CI, 24.3-24.5; P < .001), cerebrovascular disease (24.3%; 95% CI, 24.1-24.4 vs 17.8%; 95% CI, 17.7-17.8; P < .001), and peripheral vascular disease (15.8%; 95% CI, 15.7-15.9 vs 13.2%; 95% CI, 13.1-13.3; P < .001) compared with men. Women were more likely to be symptomatic (93.2%; 95% CI, 93.1-93.3 vs 91.5%; 95% CI, 91.4-91.5; P < .001) with the most common presentations being unstable angina (36.1%) and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (30.9%). Women were also more likely to undergo urgent CABG (64%; 95% CI, 63.9-64.2 vs 59.7%; 95% CI, 59.6-59.8; P < .001).

Table 1. Baseline Demographic Characteristics of the Patients Included in the Analysis.

| Variable | No. (%)a | Absolute difference (95% CI)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Men | Women | ||

| No. | 1 297 204 | 979 488 | 317 716 | |

| Age, y | 66.0 (59.0-73.0) | 65.0 (58.0-72.0) | 67.0 (60.0-74.0) | 2.00 (2.00 to −2.00) |

| Racec | ||||

| African American | 97 343 (7.5) | 59 916 (6.1) | 37 427 (11.8) | 5.66 (5.54-5.78) |

| Asian | 43 183 (3.3) | 34 005 (3.5) | 9178 (2.9) | -0.58 (−0.65 to −0.51) |

| Native American | 9178 (0.7) | 6585 (0.7) | 2593 (0.8) | 0.14 (0.11-0.18) |

| White | 1 074 096 (82.8) | 822 591 (84.0) | 251 505 (79.2) | −4.82 (−4.98 to −4.66) |

| Otherd | 47 065 (3.6) | 35 943 (3.7) | 11 122 (3.5) | -0.17 (−0.24 to −0.09) |

| BMIe | 29.2 (25.9-33.2) | 29.1 (26.0-32.8) | 29.8 (25.8-34.7) | 0.74 (0.70-0.78) |

| Body surface area, m2 | 2.0 (1.9 to-2.2) | 2.1 (1.9-2.2) | 1.8 (1.7-2.0) | −0.26 (−0.26 to −0.25) |

| Family history of coronary disease | 301 963 (23.3) | 222 153 (22.8) | 79 810 (25.2) | 2.44 (2.27-2.61) |

| Hypertension | 1 157 544 (89.3) | 865 867 (88.4) | 291 677 (91.9) | 3.40 (3.29-3.52) |

| Diabetes | 630 536 (48.6) | 451 837 (46.2) | 178 699 (56.3) | 10.11 (9.92-10.31) |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 666 868 (51.5) | 500 340 (51.1) | 166 528 (52.5) | 1.33 (1.13-1.53) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 178 803 (13.8) | 128 795 (13.2) | 50 008 (15.8) | 2.59 (2.45-2.73) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 249 927 (19.4) | 173 112 (17.80) | 76 815 (24.30) | 6.50 (6.34-6.67) |

| Chronic lung disease | 325 429 (25.5) | 234 981 (24.4) | 90 448 (29.0) | 4.48 (4.30-4.66) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 175 991 (13.7) | 143 640 (14.8) | 32 351 (10.3) | −4.48 (−4.61 to −4.36) |

| Need for home oxygen | 14 402 (1.1) | 9291 (1.0) | 5111 (1.6) | 0.66 (0.61-0.71) |

| Cancer diagnosis within 5 y | 58 937 (4.5) | 45 408 (4.6) | 13 529 (4.3) | −0.38 (−0.46 to −0.30) |

| Mediastinal radiation | 10 394 (0.8) | 4053 (0.4) | 6341 (2.0) | 1.58 (1.53-1.63) |

| Recent pneumonia | 88 362 (7.0) | 62 835 (6.6) | 25 527 (8.3) | 1.62 (1.51-1.73) |

| Liver disease | 36 688 (2.8) | 29 349 (3.0) | 7339 (2.3) | −0.69 (−0.75 to −0.62) |

| Dialysis | 40 011 (3.1) | 28 099 (2.9) | 11 912 (3.8) | 0.88 (0.81-0.95) |

| Endocarditis | 898 (0.1) | 688 (0.1) | 210 (0.1) | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.01) |

| Illicit drug use | 41 681 (3.3) | 35 137 (3.7) | 6544 (2.1) | −1.53 (−1.59 to −1.47) |

| Alcohol consumption | 751 184 (60.1) | 591 710 (62.8) | 159 474 (51.9) | −10.84 (−11.04 to −10.64) |

| Preoperative IABP | 94 118 (7.3) | 70 402 (7.2) | 23 716 (7.5) | 0.28 (0.17-0.38) |

| Urgent surgery | 787 502 (60.7) | 584 159 (59.7) | 203 343 (64.0) | 4.36 (4.17-4.56) |

| Steroids within 24 h | 29 389 (2.3) | 19 993 (2.0) | 9396 (3.0) | 0.92 (0.85-0.98) |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor within 24 h | 21 147 (1.6) | 16 170 (1.7) | 4977 (1.6) | −0.08 (−0.13 to −0.03) |

| Inotropes within 48 h | 11 423 (0.9) | 8527 (0.9) | 2896 (0.9) | 0.04 (0-0.08) |

| ADP receptor inhibitor usage within 5 d | 131 002 (10.1) | 95 923 (9.8) | 35 079 (11.0) | 1.25 (1.12-1.37) |

| Immunosuppressive therapy within 30 d | 39 790 (3.1) | 27 765 (2.8) | 12 025 (3.8) | 0.95 (0.88-1.02) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 8745 (0.7) | 6605 (0.7) | 2140 (0.7) | 0 (−0.03 to 0.03) |

| Clinical presentation on admission | ||||

| No symptoms | 71 921 (8.1) | 57 496 (8.5) | 14 425 (6.8) | −1.75 (−1.88 to −1.63) |

| Stable angina | 142 095 (16.0) | 112 107 (16.6) | 29 988 (14.1) | −2.54 (−2.72 to 2.37) |

| Unstable angina | 311 732 (35.2) | 234 846 (34.8) | 76 886 (36.1) | 1.28 (1.05-1.51) |

| Non-STEMI | 244 716 (27.6) | 178 939 (26.6) | 65 777 (30.9) | 4.36 (4.13-4.58) |

| STEMI | 36 294 (4.1) | 28 497 (4.2) | 7797 (3.7) | −0.56 (−0.66 to −0.47) |

| Angina equivalent | 34 612 (3.9) | 26 688 (4.0) | 7924 (3.7) | −0.24 (−0.33 to −0.14) |

| Others | 45 392 (5.1) | 35 366 (5.2) | 10 026 (4.7) | −0.54 (−0.64 to −0.43) |

| No. of diseased coronary vessels | ||||

| 1 | 49 637 (3.80) | 32 540 (3.3) | 17 097 (5.4) | 2.08 (1.99-2.17) |

| 2 | 248 170 (19.2) | 179 806 (18.5) | 68 364 (21.6) | 3.21 (3.05-3.37) |

| 3 | 990 077 (76.8) | 760 408 (78.1) | 229 669 (72.7) | −5.29 (−5.47 to −5.11) |

| Left main disease | 263 767 (20.3) | 200 859 (20.5) | 62 908 (19.8) | −0.71 (−0.87 to −0.55) |

| Proximal LAD disease | 212 314 (16.4) | 162 541 (16.6) | 49 773 (15.7) | −0.93 (−1.07 to −0.78) |

| Ejection fraction, % | 55.0 (45.0-60.0) | 55.0 (45.0-60.0) | 57.0 (48.0-61.0) | 2.00 (2.00 to 2.00) |

| Hematocrit, % | 39.8 (36.0-43.0) | 40.8 (37.1-43.8) | 36.7 (33.1-39.8) | −4.10 (−4.10 to −4.10) |

| White blood cell count, 103/uL | 7.6 (6.3-9.3) | 7.6 (6.3-9.2) | 7.8 (6.4-9.5) | 0.20 (0.20-0.20) |

| Platelet count, 103/uL | 209 (173-251) | 203 (169-243) | 230 (189-276) | 27.00 (26.00-27.00) |

Abbreviations: ADP, adenosine diphosphate; BMI, body mass index; IAB, intra-aortic balloon pump; LAD, left anterior descending artery; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

SI conversion factors: To convert white blood cell count to μmol/L, multiply by .001; platelet count multiple by 1.

Data are presented as count (%) or median (IQR).

Men used as reference.

Race was self-reported in the database that was used for this study. When race was not reported, we left this as a separate classification.

Race listed as “Other” is its own category in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database. Per their definition, a response of “Other” indicates that the patient's race (as determined by the patient or family) includes all other responses not included in the White, African-American, American Indian, Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian (here summarized as Native American), or Asian categories listed above.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Women had a higher incidence of single-vessel coronary disease (5.4%; 95% CI, 5.4-5.5 vs 3.3%; 95% CI, 3.3-3.4; P < .001) and double-vessel coronary disease (21.6%; 95% CI, 21.6-21.8 vs 18.5%; 95% CI, 18.4-18.6) and lower rates of triple-vessel vessel coronary disease (72.7%; 95% CI, 72.7-73.0 vs 78.1%; 95% CI, 78.1-78.3; P < .001) and left main coronary disease (19.8%; 95% CI, 19.7-19.9 vs 20.5%; 95% CI, 20.4-20.6; P < .001).

Outcome Data

The overall unadjusted operative mortality was higher in women compared with men (2.8%; 95% CI, 2.8-2.9 vs 1.7%; 95% CI, 1.7-1.7; P < .001). The overall unadjusted incidence of the composite of operative mortality and morbidity was 22.9% for women (95% CI, 22.7-23.0) and 16.7% for men (95% CI, 16.6-16.8) (P < .001). Other key postoperative outcomes by sex are summarized in Table 2. The sex disparity in overall CABG outcomes was unchanged in case of off-pump or on-pump CABG, nor in case of single-arterial or multiarterial CABG (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Unadjusted Key Outcomes by Sex.

| No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Overall | Men | Women | Absolute difference (95% CI)a |

| Total No. | 1 297 204 | 979 488 | 317 716 | NA |

| Operative mortality | 25 337 (2.0) | 16 368 (1.7) | 8969 (2.8) | 1.15 (1.09-1.21) |

| Operative mortality and morbidity | 236 163 (18.2) | 163 501 (16.7) | 72 662 (22.9) | 6.18 (6.01-6.34) |

| Stroke | 18 467 (1.4) | 12 208 (1.2) | 6259 (2.0) | 0.72 (0.67-0.78) |

| Kidney failure | 25 994 (2.0) | 18 365 (1.9) | 7629 (2.4) | 0.53 (0.47-0.59) |

| Reoperation | 28 724 (2.2) | 21 836 (2.2) | 6888 (2.2) | −0.06 (−0.12 to 0.00) |

| Sternal wound complications | 7232 (0.6) | 4322 (0.4) | 2910 (0.9) | 0.47 (0.44-0.51) |

| Prolonged | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | 92 515 (7.1) | 63 353 (6.5) | 29 162 (9.2) | 2.71 (2.60-2.82) |

| Hospital stay (>14 d) | 150 259 (11.6) | 102 404 (10.5) | 47 855 (15.1) | 4.61 (4.47-4.75) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Men used as reference.

Main Results

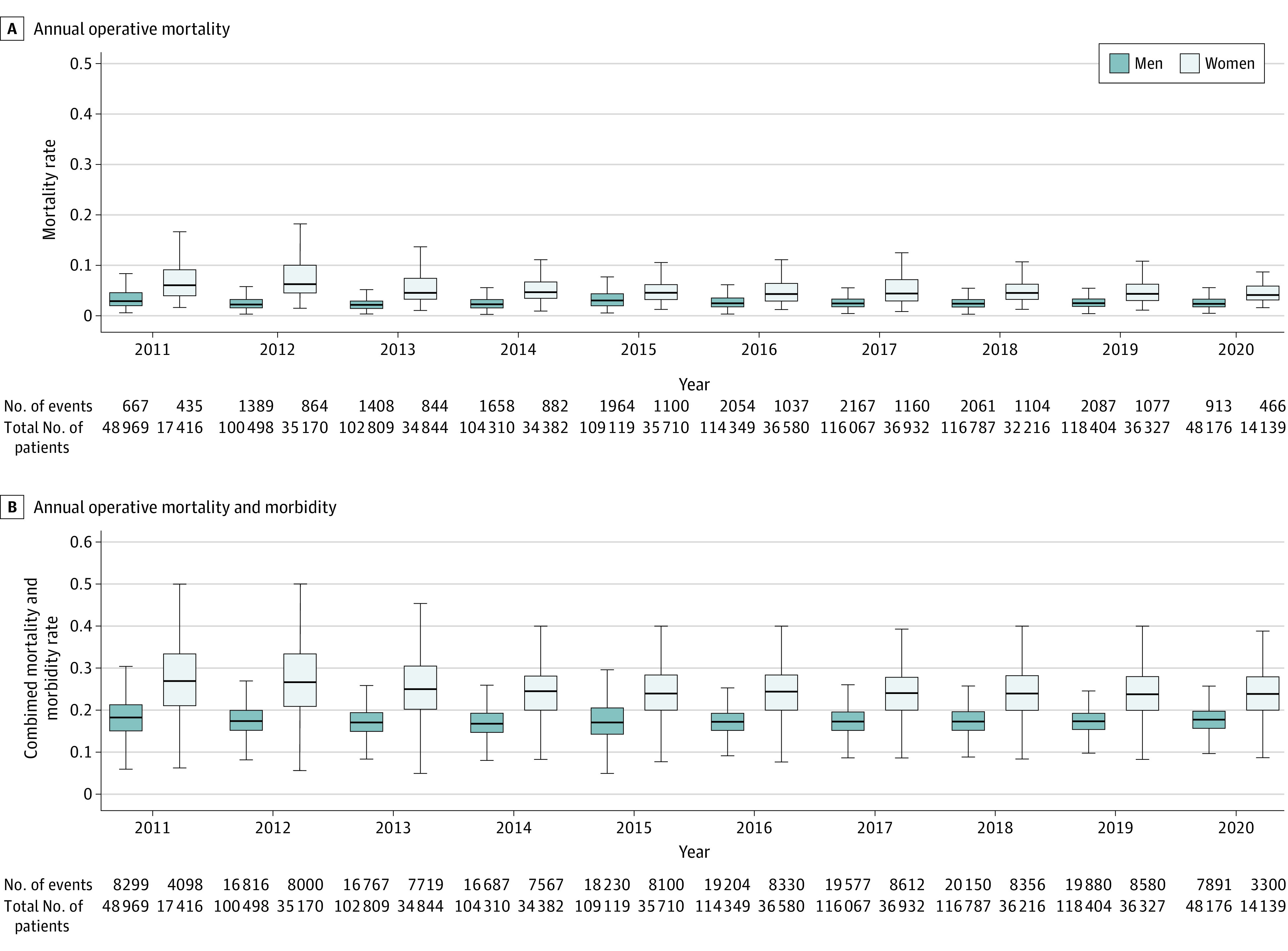

Operative mortality for women varied nonsystematically from 2.90% in 2011 to 3.33% in 2020 with a peak in 2020 (3.33%) and a nadir in 2013 (2.83%). The incidence of the composite of operative mortality and morbidity similarly varied from 26.4% in 2011 to 23.5% in 2020 with the highest value in 2011 (26.4%) and the lowest in 2016 (22.9%). Details of the primary and secondary outcome by sex and year are provided in Figure 1 and in eTable 6 in the Supplement. The observed to expected mortality ratios by year for both sexes are presented in eFigure 2 in the Supplement.

Figure 1. Annual Operative Mortality by Sex and Annual Operative Mortality and Morbidity by Sex.

P < .001 for all the outcomes for each year. Variability in the boxplots reflects the annual difference in mortality rates between hospitals. Numerators/denominators in the horizontal axes are without adjustment for variability in hospital mortality rates.

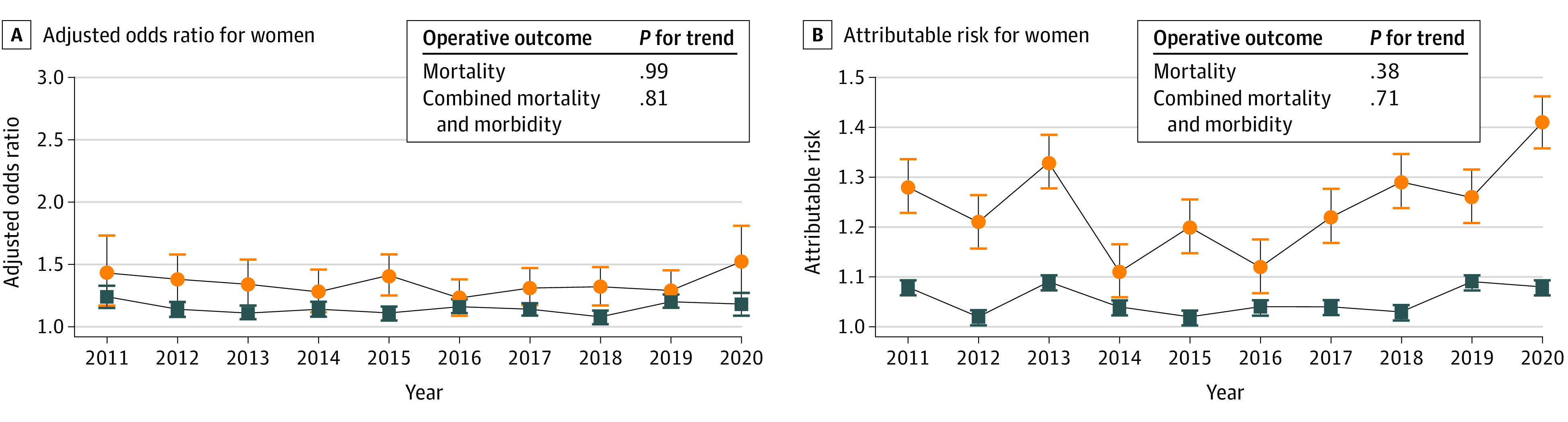

The AR of female sex for operative mortality varied from 1.28 in 2011 to 1.41 in 2020 with the highest value in 2020 (1.41) and the lowest in 2014 (1.11). There was no significant change over the study period (P for trend = 0.38). The AR for the composite of operative mortality and morbidity was 1.08 in 2011 and 2020; the highest value was in 2013 and 2019 (1.09) and the lowest in 2012 and 2015 (1.02), and there was no significant change over the study period (P for trend = 0.71).

Similar trends were seen in the confirmatory analyses using the OR (Figure 2). Details of the relative variations of the AR and the adjusted OR in each year are given in Table 3.

Figure 2. Temporal Trend for the Attributable Risk and the Adjusted Odds Ratio for Women Between 2011 and 2020.

Whiskers indicate 95% CIs.

Table 3. Relative Variation of the Attributable Risk (AR) and the Odds Ratio (OR) in Each Year Compared With the First Year of the Study.

| Year | AR | Relative variation in ARa | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Relative variation in adjusted ORa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative mortality | ||||

| 2011 | 1.28 | [Reference] | 1.43 (1.17-1.73) | [Reference] |

| 2012 | 1.21 | −0.07 | 1.38 (1.20-1.58) | −0.05 |

| 2013 | 1.33 | 0.05 | 1.34 (1.17-1.54) | −0.09 |

| 2014 | 1.11 | −0.17 | 1.28 (1.12-1.46) | −0.15 |

| 2015 | 1.20 | −0.08 | 1.41 (1.25-1.58) | −0.02 |

| 2016 | 1.12 | −0.16 | 1.23 (1.09-1.38) | −0.20 |

| 2017 | 1.22 | −0.06 | 1.31 (1.17-1.47) | −0.12 |

| 2018 | 1.29 | 0.01 | 1.32 (1.17-1.48) | −0.11 |

| 2019 | 1.26 | −0.02 | 1.29 (1.15-1.45) | −0.14 |

| 2020 | 1.41 | 0.13 | 1.52 (1.27-1.81) | 0.09 |

| Operative mortality and morbidity | ||||

| 2011 | 1.08 | [Reference] | 1.24 (1.15-1.33) | [Reference] |

| 2012 | 1.02 | −0.06 | 1.14 (1.08-1.20) | −0.10 |

| 2013 | 1.09 | 0.01 | 1.11 (1.06-1.17) | −0.13 |

| 2014 | 1.04 | −0.04 | 1.14 (1.08-1.20) | −0.10 |

| 2015 | 1.02 | −0.06 | 1.11 (1.05-1.16) | −0.13 |

| 2016 | 1.04 | −0.04 | 1.16 (1.11-1.22) | −0.08 |

| 2017 | 1.04 | −0.04 | 1.14 (1.09-1.19) | −0.10 |

| 2018 | 1.03 | −0.05 | 1.08 (1.02-1.13) | −0.16 |

| 2019 | 1.09 | 0.01 | 1.20 (1.15-1.26) | −0.04 |

| 2020 | 1.08 | 0 | 1.18 (1.09-1.27) | −0.06 |

The relative variation in each year was obtained by subtracting the attributable risk in the first year of the study from the corresponding year value (eg, for 2022: 1.21 to 1.28 = −0.07).

Discussion

Key Results

In this analysis of 1 297 204 patients (317 716 women) from the STS-ACSD, we found that women had higher risk of operative mortality and postoperative complications after CABG compared with men and that the excess risk in women was essentially unchanged over the last decade. We did not observe a significant decrease in the operative risk for women undergoing CABG in the US between 2011 and 2020.

Interpretation

Several studies have reported on the higher risk of mortality and morbidity in women after CABG. In the most recent study-level meta-analysis investigating the effect of sex on outcomes following CABG, Robinson et al4 pooled data from 84 studies including 903 346 patients (224 340 women) and found that women had a higher adjusted risk of operative mortality (OR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.64-1.92; P < .001). In addition, women were at significantly higher risk for late mortality, major adverse cardiac events, myocardial infarction, and stroke. An individual patient data meta-analysis of 4 CABG trials including 13 193 patients (2714 women) found that women have a higher adjusted incidence of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at 5 years after CABG compared with men (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04–1.21; P = .004).13 Multiple studies have also reported an increased risk of postoperative morbidity in female patients, including increased risk of transfusion, reoperation, prolonged ventilator dependence, deep sternal wound infection, and cardiac readmissions.14,15,16

It is known that CABG outcomes have significantly improved over time. In an analysis of the STS-ACSD, including 1 497 254 isolated CABG procedures between 2000 and 2009, ElBardissi and coauthors7 found that there was a significant decline in morbidity and mortality over the study period (P for trend <.001), despite a worsening of the patients’ preoperative risk profile. Similarly, in a study6 based on the National Inpatient Sample database and including more than 3 million patients undergoing CABG in the US between 2003 and 2016, Alkhouli and associates6 reported that despite a marked increase in the prevalence of clinical risk factors, there was a significant reduction in risk-adjusted CABG mortality over time (P for trend <.001). While this positive trend is generally reassuring, to date no study has investigated if it applies to women undergoing CABG.

Our study, to our knowledge, provides the only contemporary nationwide analysis of the trends in operative mortality and morbidity for women undergoing CABG in the US. Unadjusted operative mortality in women increased from 2.9% in 2011 to 3.3% in 2020 and the operative risk attributable to female sex varied from 1.28 in 2011 to 1.41 in 2020, without significant improvement over time. Similar results were seen when analyzing the composite of operative mortality and morbidity, and in all the sensitivity analyses.

The reason for the lack of improvement in outcomes for women in the last decade is unclear. It is well known that there are significant differences in baseline anatomical and clinical characteristics between men and women. Women have smaller and more spastic coronary arteries and CABG conduits when compared with men, which may increase the technical complexity of the operation17,18 and the risk of graft failure.16 The pattern of ischemic heart disease differs between women and men.19 Women more frequently present with nonobstructive coronary artery disease with coronary microvascular dysfunction and limited coronary flow reserve, a phenotype that is associated with excess cardiovascular risk and may benefit less from revascularization.20

Importantly, sex-related differences in outcomes are seen not only after surgical, but also after percutaneous coronary revascularization.21 An individual patient data meta-analysis of 21 contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention trials, including 32 877 patients (9141 women), found that women had a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with men 5 years following the intervention (adjusted HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.01-1.30; P = .04).22 In a propensity–matched analysis based on the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample that included a total of 3 603 142 patients (1 180 436 women) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or CABG for acute myocardial infarction, in-hospital mortality was higher for women than men regardless of revascularization strategy.23 A study-level meta-analysis of 6 randomized clinical trials comparing PCI and CABG in 1909 women with multivessel and/or left main disease found that PCI was associated with an increased risk of all-cause death, myocardial infarction, or stroke (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.05-1.63) compared with CABG.24 However, studies directly comparing CABG with PCI in women are lacking and current guideline recommendations on the choice of revascularization strategy are derived from studies enrolling predominantly men, thus limiting the generalizability of findings to women.

Reducing mortality in women after CABG likely entails a multifactorial approach.25 The indication to revascularization may have to be different in women compared with men due to the differences in the processes and pathology of coronary artery disease. However, current diagnostic and therapeutic protocols for coronary revascularization are all informed from data derived from studies performed prevalently in men21 and may be inadequate for women. It is possible, for example, that standardized diagnostic testing with evaluation of coronary flow reserve may aid in selection of women who are more likely to derive substantial benefit from CABG, but the current evidence is very limited and it is clear that more and better data are urgently needed to define the indication to coronary revascularization in women.

In addition, equitable delivery of the CABG procedure itself is paramount to improve outcomes for women. Jawitz and colleagues26 in an analysis from the STS database showed that in 1.2 million patients (female, 25% ) undergoing first-time isolated CABG from 2011 to 2019, women were significantly less likely to receive a left internal thoracic artery graft to the left anterior descending coronary artery, considered the gold standard in CABG surgery, in addition to less frequently receiving bilateral internal thoracic artery or radial artery grafts and achieving less completeness of revascularization.

Also, the detrimental effect of perioperative hemodilution, anemia, and transfusions are increased in women and may contribute to the difference in outcomes between sexes.27,28,29 Those factors are not captured in any available risk model and cannot be included in statistical adjustments.

Limitations

A limitation of our study is that the STS-ACSD is limited in the granularity of anatomic and functional information and it is possible that unmeasured variables affected sex-related outcomes. On the other hand, it is reassuring to note that different risk-adjustment approaches were consistent. Other important limitations are the risk of reporting bias and errors that is common to all large databases. Additionally, cardiac surgery outcomes have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the data from 2020 must be viewed in light of this additional confounder.30

Conclusions

Women remain at significantly higher risk for adverse outcomes following CABG and there has been no significant improvement over the course of the last decade. Further investigation in the determinants of operative outcomes in women is urgently needed.

eMethods. Steps for data collection and quality control in the STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database.

eTable 1. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons outcomes definitions.

eTable 2. Data fields used for risk adjustment (based on the 2018 STS Risk Model).

eTable 3. Missing data.

eTable 4. Annual coronary artery bypass grafting procedures by sex.

eTable 5. Outcomes by sex stratified by multiple or single arterial grafting and off- or on-pump CABG.

eTable 6. Unadjusted primary and secondary outcome by sex and year.

eFigure 1. Annual percentage of women undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting between 2011 and 2020.

eFigure 2. Observed-to-expected (O/E) operative mortality ratios by year for both sexes.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics `Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56-e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam M, Bandeali SJ, Kayani WT, et al. Comparison by meta-analysis of mortality after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting in women versus men. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112(3):309-317. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.03.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassan A, Chiasson M, Buth K, Hirsch G. Women have worse long-term outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting than men. Can J Cardiol. 2005;21(9):757-762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryce Robinson N, Naik A, Rahouma M, et al. Sex differences in outcomes following coronary artery bypass grafting: a meta-analysis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2021;33(6):841-847. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivab191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blankstein R, Ward RP, Arnsdorf M, Jones B, Lou YB, Pine M. Female gender is an independent predictor of operative mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: contemporary analysis of 31 Midwestern hospitals. Circulation. 2005;112(9)(suppl):I323-I327. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alkhouli M, Alqahtani F, Kalra A, et al. Trends in characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing coronary revascularization in the United States, 2003-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1921326. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ElBardissi AW, Aranki SF, Sheng S, O’Brien SM, Greenberg CC, Gammie JS. Trends in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting: an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons adult cardiac surgery database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(2):273-281. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkley Shroyer AL, Bakaeen F, Shahian DM, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database: the driving force for improvement in cardiac surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;27(2):144-151. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2015.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs JP, Shahian DM, Grau-Sepulveda M, et al. Current penetration, completeness, and representativeness of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac surgery database. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113(5):1461-1468. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.04.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shahian DM, O’Brien SM, Filardo G, et al. ; Society of Thoracic Surgeons Quality Measurement Task Force . The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2008 cardiac surgery risk models: part 1–coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(1)(suppl):S2-S22. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.05.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien SM, Feng L, He X, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2018 adult cardiac surgery risk models: part 2-statistical methods and results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(5):1419-1428. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaudino M, Di Franco A, Alexander JH, et al. Sex differences in outcomes after coronary artery bypass grafting: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Eur Heart J. 2021;43(1):18-28. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matyal R, Qureshi NQ, Mufarrih SH, et al. Update: Gender differences in CABG outcomes-Have we bridged the gap? PLoS One. 2021;16(9):e0255170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Galas FRBG, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1559-1567. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blasberg JD, Schwartz GS, Balaram SK. The role of gender in coronary surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(3):715-721. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheifer SE, Canos MR, Weinfurt KP, et al. Sex differences in coronary artery size assessed by intravascular ultrasound. Am Heart J. 2000;139(4):649-653. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(00)90043-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connor NJ, Morton JR, Birkmeyer JD, Olmstead EM, O’Connor GT; Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group . Effect of coronary artery diameter in patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 1996;93(4):652-655. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.93.4.652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia M, Mulvagh SL, Merz CN, Buring JE, Manson JE. Cardiovascular disease in women: clinical perspectives. Circ Res. 2016;118(8):1273-1293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taqueti VR, Shaw LJ, Cook NR, et al. Excess cardiovascular risk in women relative to men referred for coronary angiography is associated with severely impaired coronary flow reserve, not obstructive disease. Circulation. 2017;135(6):566-577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaudino M, Di Franco A, Cao D, et al. Sex-related outcomes of medical, percutaneous, and surgical interventions for coronary artery disease: JACC Focus Seminar 3/7. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(14):1407-1425. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosmidou I, Leon MB, Zhang Y, et al. Long-term outcomes in women and men following percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(14):1631-1640. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.01.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahowald MK, Alqahtani F, Alkhouli M. Comparison of outcomes of coronary revascularization for acute myocardial infarction in men versus women. Am J Cardiol. 2020;132:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gul B, Shah T, Head SJ, et al. Revascularization options for females with multivessel coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(8):1009-1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zwischenberger BA, Jawitz OK, Lawton JS. Coronary surgery in women: How can we improve outcomes. JTCVS Tech. 2021;10:122-128. doi: 10.1016/j.xjtc.2021.09.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jawitz OK, Lawton JS, Thibault D, et al. Sex differences in coronary artery bypass grafting techniques: a Society of Thoracic Surgeons database analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113(6):1979-1988. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.06.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Habib RH, Zacharias A, Schwann TA, Riordan CJ, Durham SJ, Shah A. Adverse effects of low hematocrit during cardiopulmonary bypass in the adult: should current practice be changed? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125(6):1438-1450. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(02)73291-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habib RH, Zacharias A, Schwann TA, et al. Role of hemodilutional anemia and transfusion during cardiopulmonary bypass in renal injury after coronary revascularization: implications on operative outcome. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(8):1749-1756. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000171531.06133.B0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Habib RH, Zacharias A, Schwann TA, Riordan CJ, Durham SJ, Shah A. Worse early outcomes in women after coronary artery bypass grafting: is it simply a matter of size? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128(3):487-488. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen TC, Thourani VH, Nissen AP, et al. The effect of COVID-19 on adult cardiac surgery in the United States in 717 103 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113(3):738-746. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Steps for data collection and quality control in the STS Adult Cardiac Surgery Database.

eTable 1. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons outcomes definitions.

eTable 2. Data fields used for risk adjustment (based on the 2018 STS Risk Model).

eTable 3. Missing data.

eTable 4. Annual coronary artery bypass grafting procedures by sex.

eTable 5. Outcomes by sex stratified by multiple or single arterial grafting and off- or on-pump CABG.

eTable 6. Unadjusted primary and secondary outcome by sex and year.

eFigure 1. Annual percentage of women undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting between 2011 and 2020.

eFigure 2. Observed-to-expected (O/E) operative mortality ratios by year for both sexes.