Abstract

Ceruloplasmin (Cp) is a glycoprotein secreted by the liver and monocytic cells and probably plays roles in inflammation and iron metabolism. We showed previously that gamma interferon (IFN-γ) induced Cp synthesis by human U937 monocytic cells but that the synthesis was subsequently halted by a transcript-specific translational silencing mechanism involving the binding of a cytosolic factor(s) to the Cp mRNA 3′ untranslated region (UTR). To investigate how protein interactions at the Cp 3′-UTR inhibit translation initiation at the distant 5′ end, we considered the “closed-loop” model of mRNA translation. In this model, the transcript termini are brought together by interactions of poly(A)-binding protein (PABP) with both the poly(A) tail and initiation factor eIF4G. The effect of these elements on Cp translational control was tested using chimeric reporter transcripts in rabbit reticulocyte lysates. The requirement for poly(A) was shown since the cytosolic inhibitor from IFN-γ-treated cells minimally inhibited the translation of a luciferase reporter upstream of the Cp 3′-UTR but almost completely blocked the translation of a transcript containing a poly(A) tail. Likewise, a requirement for poly(A) was shown for silencing of endogenous Cp mRNA. We considered the possibility that the cytosolic inhibitor blocked the interaction of PABP with the poly(A) tail or with eIF4G. We found that neither of these interactions were inhibited, as shown by immunoprecipitation of PABP followed by quantitation of the poly(A) tail by reverse transcription-PCR and of eIF4G by immunoblot analysis. We considered the alternate possibility that these interactions were required for translational silencing. When PABP was depleted from the reticulocyte lysate with anti-human PABP antibody, the cytosolic factor did not inhibit translation of the chimeric reporter, thus showing the requirement for PABP. Similarly, in lysates treated with anti-human eIF4G antibody, the cytosolic extract did not inhibit the translation of the chimeric reporter, thereby showing a requirement for eIF4G. These data show that translational silencing of Cp requires interactions of three essential elements of mRNA circularization, poly(A), PABP, and eIF4G. We suggest that Cp mRNA circularization brings the cytosolic Cp 3′-UTR-binding factor into the proximity of the translation initiation site, where it silences translation by an undetermined mechanism. These results suggest that in addition to its important function in increasing the efficiency of translation, transcript circularization may serve as an essential structural determinant for transcript-specific translational control.

Ceruloplasmin (Cp) is a 132-kDa, copper-containing glycoprotein secreted primarily by the liver, but also by monocyte/macrophages (42). Hepatic synthesis of Cp is induced during acute and chronic inflammatory processes (10). An important role in iron metabolism has been assumed for a long time (31) and was recently established by the finding of debilitating iron overload in patients with hereditary Cp deficiency (29) and in mice with targeted Cp gene disruption (14). Recently, we reported that gamma interferon (IFN-γ) induced the synthesis of Cp by U937 monocytic cells (26). However, synthesis was halted about 16 h after IFN-γ treatment by a mechanism involving transcript-specific translational silencing (25). The inhibition of translation most probably occurred at the initiation step since the 24-h treatment with IFN-γ caused a shift of Cp mRNA from the polyribosomes to the nonpolyribosomal fraction. Translational silencing was accompanied by the binding of a cytosolic factor in IFN-γ-treated cells to the Cp mRNA 3′ untranslated region (UTR), as shown by detection of a binding complex by RNA gel shift analysis and by restoration of in vitro translation by a synthetic 3′-UTR cRNA added as a “decoy.” Deletion mapping of the Cp 3′-UTR indicated an internal 100-nucleotide (nt) region of the Cp 3′-UTR that was required for complex formation as well as for silencing of translation (25).

Efficient mRNA translation and its control depend on a temporally and spatially complex orchestration of multiple protein-protein, protein-RNA, and RNA-RNA interactions. All structural elements of the transcript, including the 5′-cap (m7GpppN), 5′-UTR, 3′-UTR, and poly(A) tail, appear to be involved in the initiation of mRNA translation. Although several of these elements are involved in transcript-specific translational control, there is accumulating evidence for a special role of the 3′-UTR. Regulatory sequences in the 3′-UTR profoundly influence cell development and fate by regulating three key events in transcript processing: intracellular localization, stability, and translation initiation (47, 50, 54). For example, mRNA stability is regulated by the interaction of specific trans-acting RNA-binding proteins to cognate cis-acting sequences in the 3′-UTR of tumor necrosis factor alpha (22, 36), vascular endothelial growth factor (35, 46), inducible nitric oxide synthase (40), elastin (15), and the transferrin receptor (21). In eukaryotes, initiation is the rate-limiting step of translation under most circumstances and is often the target of both global and transcript-specific translational control (44). trans-acting factors that bind the 3′-UTR repress the initiation of translation of multiple transcripts including 15-lipoxygenase (33), MEF-2A (1), β-F1 ATPase (18), p53 (7), and amyloid precursor protein (27). The mechanism by which the binding of a factor(s) to a 3′-UTR alters the initiation of translation at the distant 5′-UTR is not clearly understood, but recent studies of the structure of the initiation complex and the protein-protein interactions of mRNA-binding proteins are beginning to shed light on this important process.

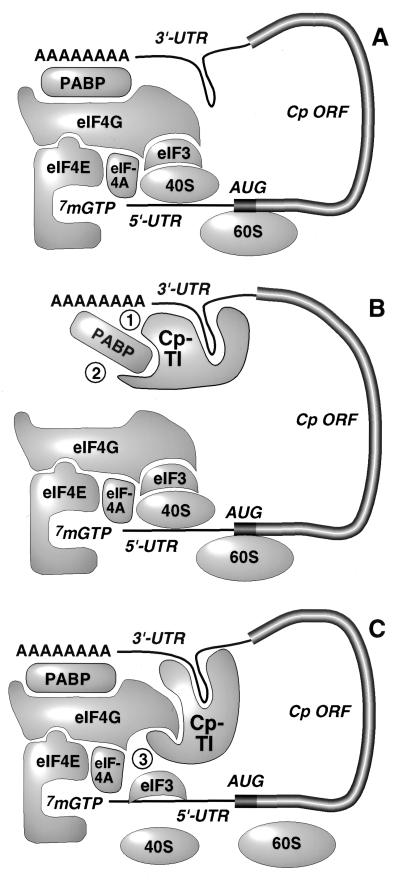

Most eukaryotic transcripts are polyadenylated by a nuclear process at the 3′ terminus (5). Multiple functions of the tail have been demonstrated, including mRNA stabilization, increased translational efficiency, and facilitation of transport of the processed mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (43, 53). Recently, the poly(A) tail has been shown to regulate translationally coupled mRNA turnover (12). Poly(A) shortening or removal initiates mRNA turnover in yeast and in somatic metazoan cells. In addition, translational silencing of maternal mRNAs during oocyte maturation and embryogenesis occurs following the removal of poly(A) (39). The poly(A) tract of most transcripts is coated with multiple copies of poly(A)-binding protein (PABP), a 70-kDa protein with four highly conserved RNA recognition motifs (13). In yeast cell extracts, PABP that was bound to poly(A) also bound to the translation initiation factor eIF4G (48). eIF4G in turn interacts with cap-binding protein eIF4E, effectively circularizing the mRNA via end-to-end complex formation (Fig. 1A). This complex has been reconstituted in vitro using purified components and visualized by atomic force microscopy (43, 52). Transcript circularization is poly(A) dependent, and translation is enhanced by the presence of a PABP-poly(A) complex, most probably by enhancing recruitment of the 40S ribosomal subunit (49). Circularization of mRNA may improve translation efficiency by facilitating the utilization or recycling of 40S ribosomes (9, 24). Alternatively, a proofreading function of circularization has been suggested in which the recognition of correctly processed mRNA is improved (52). Several laboratories have speculated that regulatory proteins that bind to the 5′- or 3′-UTR may function by disrupting or enhancing circularization (9, 52); however, a role for transcript circularization in translational control has not yet been shown. Here we provide experimental evidence that the presence of poly(A), PABP, and eIF4G, the central elements of mRNA circularization, are essential for translational silencing of Cp in IFN-γ-treated monocytic cells.

FIG. 1.

Models for translational silencing of Cp. (A) “Circular” or “closed-loop” mRNA model showing circularization mediated by PABP binding to both the poly(A) tail and eIF4G of the initiation complex. (B) Inhibition of Cp mRNA translation by disruption of Cp mRNA circularization. Indicated are two potential mechanisms by which the translational inhibitor of Cp (CpTI) may block translation: 1, disruption of PABP interaction with poly(A); 2, disruption of PABP interaction with eIF4G. (C) Inhibition of Cp mRNA translation by a mechanism dependent on mRNA circularization. In this proposed mechanism (mechanism 3), circularization of the transcript brings the 3′-UTR-bound CpTI into the proximity of the 5′-translation initiation complex, where it exerts its inhibitory activity. Abbreviations: eIF4A, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A; eIF4E, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E; eIF3, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3; ORF, open reading frame.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Rabbit reticulocyte lysate, methionine-minus amino acid mixture, and RNasin were purchased from Promega (Madison, Wis.). Human IFN-γ, RNase H, and Superscript were purchased from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, Md.). [35S]methionine (translation grade) was purchased from NEN-DuPont (Boston, Mass.) for in vitro translation. All other assay reagents were from Sigma.

Antibodies.

Monoclonal antibodies (as ascites fluids) against human PABP and Sp2/O were gifts from Gideon Dreyfuss, University of Pennsylvania (13). Polyclonal rabbit antisera against a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein of the PABP-binding site of eIF4G were prepared as described by Wakiyama et al. (51). Polyclonal rabbit anti-human Cp antibody was from Accurate (Westbury, N.Y.).

cRNA constructs.

Luciferase (Luc) cRNA was made by in vitro transcription of pGEM-Luc (Promega). Cloning of the human Cp 3′-UTR was described previously (25). A construct containing Luc upstream of the human Cp 3′-UTR (Luc-Cp 3′-UTR) was prepared by cloning the 247-nt Cp 3′-UTR into the StuI-SacI site of pGEM-Luc. A construct containing Luc upstream of the Cp 3′-UTR and followed by a poly(A) tail [Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A)] was prepared by cloning the BamHI-SacI restriction fragment of pGEM-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR into the appropriate site in PSP64 poly(A) (Promega).

Epitope mapping of monoclonal anti-human PABP.

Regions of PABP were expressed as chimeric, Flag-tagged proteins from vectors expressing the N-terminal 376 amino acids of PABP [pcDNA3-Flag-PABP(1–376)] and the C-terminal 257 amino acids [pcDNA3-Flag-PABP(377–633)] (17). The pcDNA3-Flag empty vector was used as control. HeLa cells were infected with vaccinia virus vTF7-3 and then subjected to transient transfection with the plasmids using Lipofectamine (Gibco-BRL). After 20 h, cell extracts containing 10 μg of protein were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (10% polyacrylamide). Immunoblot analysis was done with monoclonal anti-human PABP and anti-Flag (Sigma) antibodies.

In vitro transcription of chimeric luciferase-Cp 3′-UTR constructs.

pGEM-Luc and pGEM-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR constructs were linearized using SfiI, and PSP64 Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) was linearized using PvuII. Linearized constructs were subjected to in vitro transcription with Sp6 polymerase using the MegaScript kit (Ambion, Austin, Tex.). The cRNA transcripts were capped by the addition of the cap analog m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G and GTP in the ratio of 4:1 (Message Machine; Ambion). Capped T7 gene 10 transcript was made by in vitro transcription of pGEMEX-2 by T7 polymerase using Message Machine. Full-length cRNA transcripts were purified by electrophoresis on a 5% acrylamide gel containing 8 M urea.

Preparation of cytosolic extracts from U937 cells.

Human U937 monocytic cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.; CRL 1593.2) were preincubated for 3 h in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium (108 cells per 50 ml), and then IFN-γ (500 U/ml) was added for 8 or 24 h. The cells were harvested by scraping and suspended in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6)–50 mM NaCl–1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)–1 mM dithiothreitol. The suspension was subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles, passaged several times through a 26-gauge needle, and ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min. The protein concentration of the supernatant was adjusted to 1 mg/ml, and 4 μg was used in the in vitro translation reaction.

In vitro translation of Cp mRNA and cRNA by a reticulocyte lysate.

To measure translation of endogenous (or deadenylated) Cp mRNA, total RNA from 108 U937 cells was isolated by two rounds of Trizol extraction. An aliquot (100 μg) was subjected to in vitro translation by addition to 35 μl of rabbit reticulocyte lysate, 20 μM methionine-free amino acid mixture, 40 U of RNasin, 20 μCi of translation grade [35S]methionine, and 4 μg of cell extract in a total volume of 50 μl for 1 h at 30°C. To isolate Cp, an aliquot of the translation reaction mixture (45 μl) was subjected to immunoprecipitation using rabbit anti-human Cp antibody and protein A-Sepharose in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 1 mM PMSF. The immunoprecipitated protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE (7% polyacrylamide). The gel was fixed, soaked in Amplify, dried, and used to expose Kodak MR film. To evaluate the total pool of newly synthesized proteins, a 5-μl aliquot that was not subjected to immunoprecipitation was similarly subjected to SDS-PAGE (7% polyacrylamide) and fluorography.

To measure translation of purified cRNA, the in vitro-synthesized transcript was gel purified and the eluted transcript (200 ng) was subjected to in vitro translation as above. A 10-μl aliquot of the reaction mixture was resolved by SDS-PAGE (7% polyacrylamide). The gel was fixed, treated with Amplify (Amersham), dried, and used to expose Kodak MR film.

Removal of the poly(A) tail of cellular Cp mRNA.

U937 cells (5 × 108) were treated with IFN-γ (500 U/ml) for 8 h. Poly(A)-containing mRNA was isolated from 100 μg of total RNA by poly(A) selection using the oligo-Tex mRNA kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). The poly(A) tail was removed by incubating mRNA with 2 μg of oligo(dT) (20-mer) for 30 min at 37°C in a 20-μl reaction solution containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 8.0), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 20 U of RNasin (Promega). Double-stranded regions containing DNA-RNA hybrids were digested by incubation with 20 U of RNase H (Life Technology) for an additional 60 min at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by addition of 10 mM EDTA, and deadenylated mRNA was isolated by Trizol extraction and ethanol precipitation. To assess Cp mRNA shortening, aliquots were fractionated on a 1% agarose–formaldehyde gel and transferred to Nytran membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.). The blot was hybridized with a randomly primed, 32P-labeled 646-bp human Cp cDNA probe (nt 984 to 1629 in the open reading frame). To verify the removal of the poly(A) tail, aliquots of RNase H-treated and untreated cellular mRNA were subjected to reverse transcription using oligo(dT) and Superscript (Life Technology), followed by PCR amplification using primers encompassing the full-length Cp 3′-UTR.

Quantitation of binding of PABP to poly(A) of chimeric Cp 3′-UTR cRNA in reticulocyte lysate and to endogenous transcript in U937 cells.

A capped Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) cRNA construct [or the same construct lacking poly(A) as control] was prepared by in vitro transcription. The product was treated with RNase-free DNase I (Ambion) followed by acidic phenol extraction, ethanol precipitation, and gel purification. To permit binding of PABP in the reticulocyte lysate to the poly(A) tail, purified transcript (200 ng) was incubated at 30°C for 1 h with 35 μl of rabbit reticulocyte lysate and 40 U of RNasin in the presence of cytosolic extracts from IFN-γ-treated U937 cells. PABP was collected by immunoprecipitation using 3 μl of monoclonal anti-human PABP (or monoclonal antibody Sp2/O as control) and protein A-Sepharose in buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 1 mM PMSF (pH 7.6). The monoclonal anti-human PABP antibody was previously shown to recognize rabbit PABP (13). PABP-bound RNA was isolated from the immunoprecipitate by Trizol (Life Technologies) extraction of the beads and ethanol precipitation. The amount of chimeric cRNA bound to PABP was quantitated by reverse transcription using Superscript and an antisense primer to the extreme 3′ terminus of the Cp 3′-UTR followed by PCR amplification of the Cp 3′-UTR using gene-specific primers. To determine the binding of PABP to poly(A) in cells, cytosolic extracts (400 μg of protein) from IFN-γ-treated U937 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-human PABP antibody (and control antibody). Polyadenylated, PABP-bound mRNA was isolated and subjected to reverse transcription with oligo(dT) followed by PCR amplification with Cp 3′-UTR-specific primers. The linearity of the amplification was confirmed by PCR cycle dependence.

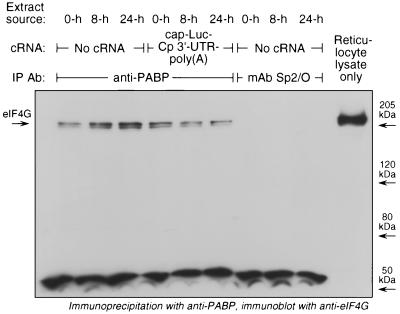

Determination of eIF4G-PABP interaction by immunoprecipitation of PABP followed by eIF4G immunoblot analysis.

An in vitro translation reaction mixture containing rabbit reticulocyte lysate, cRNA, and unlabeled methionine was incubated with 3 μl of monoclonal anti-PABP antibody (or monoclonal antibody Sp2/O as control) in a total volume of 50 μl. Immune complexes were precipitated by addition of protein A-Sepharose in buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% Triton X-100. The immunoprecipitated protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE (5% polyacrylamide) using Protogel (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, Ga.) and was transferred by a semidry method to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.). The membrane was incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-human eIF4G (1:10,000) as primary antibody and then with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000) (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). The blot was visualized by chemiluminescense using ECL Plus (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) and BioMax-MR film (Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.).

Statistical analysis.

All key experiments have been done at least three times with similar results, and results of representative experiments are shown. In some cases, results of replicate experiments have been normalized to the controls and reported as mean values ± standard error of the mean.

RESULTS

Translational silencing of Cp requires the 3′-UTR and poly(A) tail.

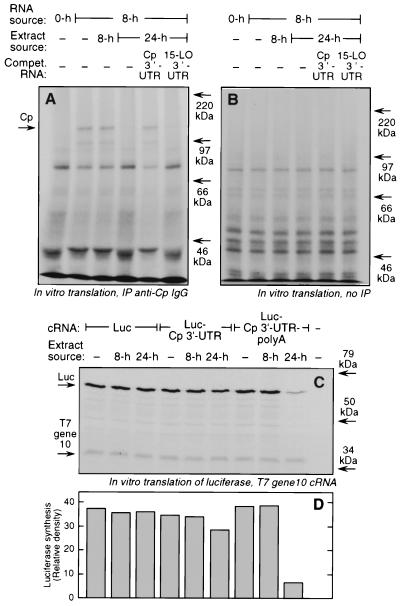

The translational silencing activity of U937 cell cytosolic extracts was examined in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate system. U937 cells were incubated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h. Total cellular RNA was isolated from the cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 h. This treatment induces Cp mRNA and protein expression and also provides an RNA template for efficient Cp translation by a rabbit reticulocyte lysate (25). The RNA was subjected to in vitro translation in the presence of cytosolic extracts from the IFN-γ-treated cells. The specific translation of Cp mRNA was determined by immunoprecipitation of the translation reaction product using polyclonal anti-human Cp antibody. In agreement with our earlier report (25), the extract made from cells treated with IFN-γ for 24 h completely inhibited the translation of Cp mRNA whereas the extract made from cells treated for 8 h did not inhibit translation (Fig. 2A). The translated Cp was a full-length product since it comigrated with an authentic human Cp standard. A band of approximately 100 kDa that appeared to be coregulated with Cp was seen in some experiments. It may be a premature translation termination product of Cp mRNA or a proteolysis product of Cp. Its variable appearance may be due to differences in commercial rabbit reticulocyte lysates used in these studies. An important role of the Cp 3′-UTR in translational silencing was shown by performing a decoy experiment. Cp translation was completely restored by preincubating the inhibitory extract with a competitor consisting of a synthetic, full-length Cp 3′-UTR cRNA. As a control for specificity, the 3′-UTR of 15-lipoxygenase, shown to be required for translational control of that transcript (33, 34), was found to lack decoy activity. The amount of competitors added was estimated to be greatly in excess of the amount of endogenous Cp mRNA; assuming that the low-expressing, endogenous Cp transcript is less than 1% of the total mRNA, then the molar excess of competitor was at least 150-fold. As a control for target transcript specificity, the effect of the cytosolic inhibitor on the translation of other proteins was determined. Cytosolic extracts from IFN-γ-treated U937 cells did not inhibit the translation of other cellular mRNAs, as shown by analysis of the total in vitro translation product, i.e., lysates not subjected to immunoprecipitation (Fig. 2B). Thus, the 3′-UTR is necessary for transcript-specific translational silencing of Cp.

FIG. 2.

Role of 3′-UTR and the poly(A) tail in translational silencing of Cp in IFN-γ-activated U937 cells. (A) U937 cells (5 × 108) were treated with IFN-γ (500 U/ml) for 8 or 24 h. For the translation template, total RNA was extracted from cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 h. The mRNA from 100 μg of total RNA was subjected to in vitro translation in a reticulocyte lysate with [35S]methionine in the presence of cytosolic extracts (4 μg of protein) from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h. Some extracts were preincubated with synthetic, unlabeled Cp 3′-UTR and 15-lipoxygenase (15-LO) 3′-UTR cRNA (0.5 μg) as competitors before being added to the translation reaction mixture. An aliquot (45 μl) was subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) using rabbit anti-human Cp IgG and translated, and [35S]Cp was resolved by SDS-PAGE (7% polyacrylamide) and detected by fluorography. (B) Total in vitro protein synthesis was determined with a 5-μl aliquot of the same translation reaction mixture described in panel A that was not subjected to immunoprecipitation. 35S-labeled protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE and detected by fluorography. (C) Capped cRNA transcripts cap-Luc, cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR, and cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) were gel purified and subjected (200 ng of each) to in vitro translation at 30°C for 60 min in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate containing [35S]methionine and cytosolic extracts (4 μg of protein) from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h. A capped, gel-purified transcript of T7 gene 10 (100 ng) was added to each lysate as a loading control. Newly translated, 35S-labeled Luc and T7 gene 10 were resolved by SDS-PAGE (7% polyacrylamide) and detected by fluorography. (D) The relative rate of Luc synthesis under each condition was quantitated by densitometry.

To test whether the Cp 3′-UTR is sufficient to confer translational silencing of a transcript, we used chimeric cRNA constructs containing Luc as reporter. Capped, chimeric reporter transcripts containing Luc alone, Luc upstream of the Cp 3′-UTR (cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR), and Luc upstream of the Cp 3′-UTR and a 30-nt stretch of poly(A) tail [cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A)] were prepared. The transcripts were subjected to in vitro translation in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence of the cytosolic inhibitor from IFN-γ-treated U937 cells. cRNA carrying T7 gene 10 was added to each translation reaction mixture as a control for loading as well as for nonspecific inhibition of translation. As expected, the extracts made from cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h did not inhibit translation of the Luc cRNA not containing the Cp 3′-UTR (Fig. 2C and D). However, the 24-h extract, which almost completely inhibited the in vitro translation of cellular Cp mRNA, caused only a modest inhibition of translation of the synthetic Luc-Cp 3′-UTR transcript. This result suggested that the 3′-UTR was not sufficient to confer translational silencing to a heterologous transcript. Translational silencing of Luc by the 24-h extract (but not by the 8-h extract) was seen when poly(A) was present downstream of the Cp 3′-UTR (Fig. 2C and D). The 24-h extract inhibited the translation of Luc-Cp 3′-UTR-poly(A) compared to Luc-Cp 3′-UTR by 77% ± 6% in four experiments, thus showing a stringent requirement for poly(A) for translational control. Similar expression of the T7 gene 10 product in all lanes showed equal loading of transcript and similar global translation efficiency under all conditions. The minor 35S-labeled bands running below Luc were most probably due to premature termination (or internal initiation) of the Luc transcript since they followed the same lane-to-lane pattern as full-length Luc. The presence of a poly(A) tail increased Luc-Cp 3′-UTR translation by 10 to 30% under basal conditions, i.e., when no cytosolic extract was present. The relatively minor dependence of basal translation on transcript adenylation is consistent with previous reports and may be due to non-rate-limiting amounts of ribosomes and initiation factors in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (2, 28, 38).

We examined whether the poly(A) tail was also required for translational silencing of the endogenous U937 cell Cp transcript. mRNA was isolated from IFN-γ-activated U937 cells (8-h treatment), and the poly(A) tail was removed by treatment with oligo(dT) and RNase H. Efficient removal of the tail was shown by Northern blot analysis, in which oligo(dT)- and RNase H-treated Cp mRNA had slightly higher electrophoretic mobility (Fig. 3A). Poly(A) tail removal was confirmed by reverse transcription using oligo-(dT) followed by PCR amplification using primers encompassing the full-length Cp 3′-UTR; no product was observed when the template mRNA was pretreated with oligo(dT) and RNase H (Fig. 3B). Intact and deadenylated Cp transcripts were subjected to in vitro translation in rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence of cytosolic extracts prepared from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h. Newly translated [35S]Cp was immunoprecipitated with anti-Cp immunoglobulin G (IgG) and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The 24-h extract effectively inhibited the translation of the intact transcript but only slightly inhibited the translation of the deadenylated transcript (Fig. 3C). The same extract did not inhibit the translation of other adenylated or deadenylated cellular transcripts, as shown by electrophoresis of an aliquot of the translation reaction mixture not subjected to immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3D). The translation rate of detectable cellular transcripts was not influenced significantly by the polyadenylation state, an observation consistent with the small effect of poly(A) on reporter transcript translation shown in Fig. 2C. In summary, these results show that the poly(A) tail, in addition to the 3′-UTR, is an essential element for translational silencing of Cp in IFN-γ-treated U937 cells.

FIG. 3.

Role of poly(A) tail in translational silencing of endogenous Cp mRNA. U937 cells (5 × 108) were treated with IFN-γ (500 U/ml) for 8 or 24 h. Poly(A)-containing mRNA was isolated from total RNA (100 μg) extracted from cells treated for 8 h. The poly(A) tail was removed by incubation with oligo(dT) (18-mer), and then double-stranded regions of DNA-RNA hybrids were digested by incubation with RNase H. The reaction was terminated by addition of 10 mM EDTA followed by ethanol precipitation. (A) The Cp transcript length was determined by Northern blot hybridization using radiolabeled Cp cDNA as probe. The two major transcripts are indicated by arrow. (B) To verify the absence of a poly(A) tail, aliquots of RNase H-treated and untreated cellular mRNA were subjected to reverse transcription using Superscript and oligo(dT) followed by PCR amplification using primers encompassing the full-length Cp 3′-UTR. (C) Intact and deadenylated cellular mRNA were subjected to in vitro translation in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate with [35S]methionine in the presence of cytosolic extracts (4 μg of protein) from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h (the rightmost pair of lanes show the effect of replicate 24-h extracts on translation of deadenylated RNA). Newly synthesized, [35S]Cp was immunoprecipitated (IP) with rabbit anti-human Cp IgG, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and detected by fluorography (arrow). (D) To show specificity of the translational inhibition by U937 cell extracts, aliquots of the rabbit reticulocyte lysates that were not subjected to immunoprecipitation were resolved by SDS-PAGE and fluorography.

Effect of the IFN-γ-activated translational inhibitor on the interactions of PABP with the poly(A) tail and with eIF4G.

Studies indicate that the 3′ terminus of a transcript is directly connected to the 5′ terminus of the same transcript by a discrete set of RNA-protein and protein-protein interactions which cause mRNA circularization (48, 49, 52). We used this model as the basis of two potential mechanisms by which a 3′-UTR-binding protein inhibits Cp translation. According to the first mechanism, the inhibitory cytosolic factor prevents one or more protein-mRNA or protein-protein interactions required for transcript circularization, thereby inhibiting translation (Fig. 1B). This mechanism of translational control has been suggested by others (9, 52), but experimental evidence has not been reported. According to the second mechanism, the silencing activity of the cytosolic factor is not inhibited by but, rather, requires, protein-mRNA and protein-protein interactions leading to transcript circularization (Fig. 1C). In this case, suppression of these interactions, or removal or inactivation of any of the requisite components, would prevent translational silencing by the 3′-UTR-binding protein.

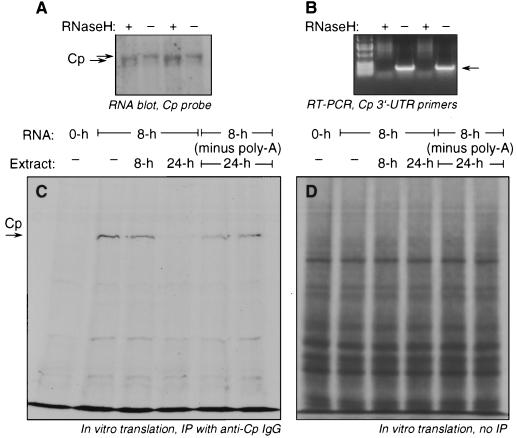

In view of the requirement of the poly(A) tail for translational silencing of Cp and the importance of the interaction of PABP with poly(A) in translational initiation, we considered the possibility that the cytosolic factor from IFN-γ-treated cells blocked this interaction (Fig. 1B, mechanism 1). To measure this interaction, we used a strategy in which a monoclonal antibody against human PABP was used to immunoprecipitate PABP-bound cRNA from reticulocyte lysate and the specific chimeric transcript quantitated by reverse transcription-PCR. The epitope was mapped to determine whether antibody binding was likely to interfere with critical PABP interactions. Flag-tagged N- and C-terminal regions of PABP were expressed by transfection of HeLa cells with pcDNA3-Flag-PABP(1–376) and pcDNA3-Flag-PABP(377–633), respectively (17). Empty pcDNA3-Flag vector was used as a control. Immunoblot analysis of HeLa cell extracts showed that monoclonal anti-PABP antibody recognizes the full-length PABP and PABP(377–633) but not PABP(1–376) (Fig. 4A, left panel). Equal expression of N- and C-terminal regions was shown by immunoblotting with anti-Flag antibody (right panel). From these data it is expected that the anti-PABP (C terminus) antibody should not disrupt the binding of PABP to poly(A) and eIF4G since the four RNA recognition motifs and the sites of interaction with poly(A) and eIF4G are present in the N-terminal region of PABP (3, 6, 13, 17).

FIG. 4.

Effect of the cytosolic inhibitor on binding of PABP to polyadenylated chimeric transcript. (A) The recognition site of anti-human PABP antibody was mapped by expression of Flag-tagged chimeric plasmids containing N- and C-terminal PABP regions in Hela cells. Cells were infected with vaccinia virus vTF7-3 and transiently transfected with pcDNA3-Flag-PABP(1–376), pcDNA3-FLAG-PABP(377–633), or with pcDNA3-Flag as control. At 20 h after transfection, cell extracts (10 mg protein) were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) and subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-human PABP antibody (left) or anti-Flag antibody (right). (B) (Upper panel) Gel-purified transcripts cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR and cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) (200 ng of each) were incubated with rabbit reticulocyte lysates for 15 min in the presence of cytosolic extracts from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h. PABP was immunoprecipitated (IP) by addition of monoclonal anti-human PABP (3 μl) and protein A-Sepharose. PABP-bound RNA was extracted by Trizol and subjected to reverse transcription using a primer for the extreme 3′ end of Cp 3′-UTR followed by PCR amplification with primers for the extreme 5′ and 3′ ends of the full-length Cp 3′-UTR (the 17 cycles used gave a product in the linear range of the assay [not shown]). The leftmost lane is a DNA ladder containing a series of DNA fragments at multiples of 100-bp (Life Technologies). The predicted position of the amplified product is indicated by an arrow. (Lower panel) Same as in the upper panel but without the addition of reverse transcriptase (RT) to the reverse transcription reaction. (C) (Upper panel) The binding of PABP to endogenous Cp transcript in U937 cells was determined. U937 cells were incubated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h, and lysates (400 μg of protein) were subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-human PABP antibody. PABP-bound mRNA was extracted and subjected to reverse transcription using an oligo(dT) primer. The cDNA was subjected to 12 or 16 cycles of PCR amplification using primers for the extreme 5′ and 3′ ends of the full-length Cp 3′-UTR. (Lower panel) Same as in the upper panel but without the addition of reverse transcriptase.

The chimeric cRNA cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) construct and the same construct lacking a poly(A) tail were incubated with reticulocyte lysates (as a source of PABP) in the presence of cytosolic extracts from IFN-γ-treated U937 cells. PABP was immunoprecipitated from the lysate using anti-PABP antibody (or control antibody). The amount of chimeric transcript bound to PABP was quantitated by reverse transcription-PCR amplification using primers encompassing the full-length Cp 3′-UTR. Substantial binding of cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) to PABP was observed (Fig. 4B). Binding specificity was shown by the absence of signal when the lysate was immunoprecipitated with a control antibody (Fig. 4B, upper panel) or when reverse transcriptase was not included in the reaction mixture (lower panel). Binding of cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR-poly(A) to PABP was not diminished by cytosolic extracts from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for either 8 or 24 h (Fig. 4B). Since PABP can bind to nonpolyadenylated regions of mRNA [although with lower affinity than it binds to the poly(A) tail] (9), we examined the interaction of PABP with the cRNA construct lacking poly(A) (cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR). Only a very small amount of amplicon was detected (and not in all experiments), suggesting specificity for binding to poly(A) in the chimeric construct used. These results suggest that the cytosolic inhibitor does not silence Cp translation by blocking the binding of PABP to poly(A).

The above experiment tested the effect of the cytosolic inhibitor on the interaction of PABP with a synthetic, poly(A)-containing transcript in rabbit reticulocyte lysates. We extended these results to the interaction of PABP with endogenous Cp mRNA in U937 cells. U937 cells were treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h, and lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-human PABP antibody. After RNA extraction, PABP-bound Cp transcript was semiquantitatively determined by reverse transcription with oligo(dT) followed by PCR amplification using Cp 3′-UTR-specific primers. The same amount of PABP-bound Cp mRNA was found in lysates made from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 and 24 h (Fig. 4C, upper panel). Similar results at two levels of PCR amplification showed response linearity under these conditions. The specificity of the amplified product was shown by its absence in lysates immunoprecipitated with SP2/O control antibody or when reverse transcriptase was omitted (Fig. 4C, lower panel). Therefore, PABP binding to endogenous Cp mRNA is not inhibited by a 24-h treatment of U937 cells with IFN-γ.

The cytosolic inhibitor could silence translation by blocking the interaction of PABP with eIF4G, a requirement for mRNA circularization (9, 49) (Fig. 1B, mechanism 2). PABP-bound eIF4G was determined by immunoprecipitation of PABP from reticulocyte lysates followed by immunoblot analysis using anti-eIF4G antibody. As shown above, the epitope recognized by the monoclonal anti-PABP antibody is not near the eIF4G interaction site. Cytosolic extracts from IFN-γ-treated U937 cells did not decrease the amount of PABP-bound eIF4G (Fig. 5). The specificity of the interaction was shown by the complete absence of eIF4G in the immunoprecipitate prepared using monoclonal antibody Sp2/O as control. Since the binding between eIF4G and PABP may be facilitated by mRNA containing both translation initiation sites and a poly(A) tail, this experiment was also done in the presence of the poly(A)-containing chimeric reporter cRNA, cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A). There was only a very small inhibition of the PABP-eIF4G interaction by the 24-h extract; this inhibition was not considered to be specific since the 8-h extract showed a similar inhibition. We were unable to determine the effect of IFN-γ treatment on the PABP-eIF4G interaction in U937 cells because, under all conditions tested, eIF4G became highly degraded during lysate preparation from monocytic cells (data not shown). Together, these experiments indicate that the cytosolic inhibitor factor in IFN-γ-treated U937 cells does not block the interaction of PABP with either the poly(A) tail or eIF4G, thus arguing against the mechanism in Fig. 1B. The fact that these interactions occur, even in the presence of the cytosolic inhibitor, supports the alternate mechanism in which interactions at the 5′ and 3′ termini are required for translational control of Cp (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 5.

Effect of the cytosolic inhibitor on binding of PABP to eIF4G. Reticulocyte lysates (50 μl) were incubated with cytosolic extracts (4 μg of protein) from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h. To one set of lysates was added cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) cRNA (200 ng). PABP was immunoprecipitated (IP) with monoclonal anti-human PABP antibody (Ab) (or with monoclonal antibody [mAb] Sp2/O as a control) and protein A-Sepharose beads. The beads were washed and boiled with Laemmli buffer, and the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (5% polyacrylamide). The resolved proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P and subjected to immunoblot analysis using polyclonal rabbit anti-human eIF4G antibody. The rightmost lane contained untreated reticulocyte lysate (1 μl) as an eIF4G standard.

Requirement for PABP and initiation factor eIF4G in translational silencing of Cp.

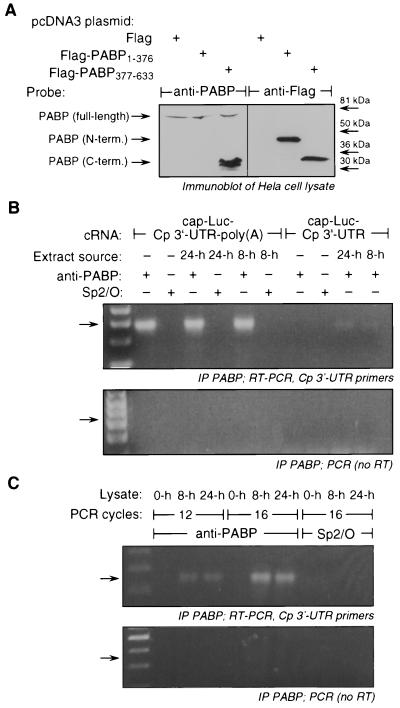

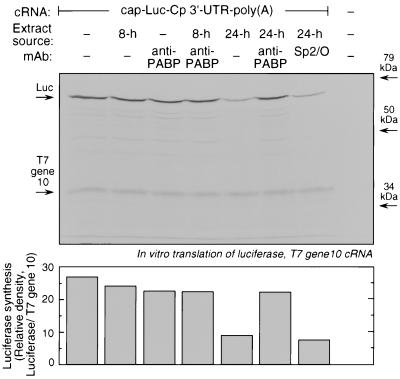

We further examined the alternate mechanism of translational silencing of Cp by determining whether the essential elements of the interaction of the 5′ and 3′ termini were required. We first tested the requirement for PABP in translational silencing of Cp. Rabbit reticulocyte lysates were preincubated for 15 min with monoclonal anti-human PABP (or with monoclonal antibody Sp2/O as a control). The chimeric cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) transcript was used as a template for in vitro translation in the presence of the cytosolic extracts from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h. As shown above, the 24-h cytosolic extract effectively inhibited translation of the reporter; however, in the presence of anti-PABP antibody, the inhibitory activity of the extract was greatly diminished (Fig. 6). In three repetitions of this experiment, reporter translation in the presence of the 24-h extract was 33% ± 5% of that of the untreated control, and anti-PABP antibody restored translation to 87% ± 5% of that of the control. Specificity was shown by the absence of any restorative activity after treatment of the reticulocyte lysate with the control monoclonal antibody, Sp2/O. The effect of PABP inactivation on basal translation was small, averaging about 10% inhibition in multiple experiments, suggesting only a marginal requirement for PABP for basal translation by reticulocyte lysates, a finding consistent with previous observations. Translation of T7 gene 10 cRNA was not altered by any treatment (Fig. 6). Given that the epitope recognized by anti-PABP antibody is distinct from the sites of eIF4G and poly(A) interaction, the restoration of Luc translation by this antibody merits consideration. It is possible that the antibody inhibits the interaction of proteins known to bind the C terminus of PABP, e.g., eRF3, Paip-1 and Paip-2, and Pbp1p, which may contribute to transcript structure or circularization (11, 16, 20, 23). Alternatively, binding of the antibody to the C terminus of PABP may sterically hinder protein-protein or protein-mRNA interactions at the N terminus, thereby preventing or altering transcript circularization.

FIG. 6.

Requirement for PABP in transcript-specific translational silencing of the polyadenylated chimeric reporter transcript. (Upper panel) Rabbit reticulocyte lysates were preincubated for 15 min with 3 μl of monoclonal anti-human PABP or with monoclonal antibody (mAb) Sp2/O as a control. Gel-purified cRNA transcript cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) (100 ng) was subjected to in vitro translation by reticulocyte lysates for 60 min at 30°C in the presence of [35S]methionine and cytosolic extracts (4 μg of protein) from IFN-γ-treated U937 cells. A cRNA transcript encoding T7 gene 10 (100 ng) was added as a control. Newly synthesized, 35S-labeled Luc and T7 gene 10 were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the radiolabeled bands were detected by fluorography. (Lower panel) The relative amount of Luc synthesis was quantitated by densitometry and normalized by division by T7 gene 10 synthesis under each condition.

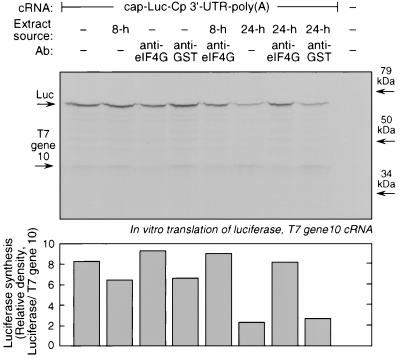

To investigate the requirement for eIF4G, we took advantage of an antibody made against the N-terminal sequence of human eIF4G, which is responsible for PABP binding (17). Rabbit reticulocyte lysates were preincubated with polyclonal rabbit antiserum against a GST fusion protein of the PABP-binding site of eIF4G (or with rabbit antiserum against GST as a control). Chimeric cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) was added to the lysate as a template for in vitro translation in the presence of the cytosolic extracts from U937 cells treated with IFN-γ for 8 or 24 h. At the amount of anti-eIF4G used, basal translation of both cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A) and T7 gene 10 control cRNA was partially inhibited (Fig. 7). Therefore, to determine the specific translational inhibition of Luc, the ratio of translation of Luc relative to that of T7 gene 10 was calculated. The 24-h (but not the 8-h) cytosolic extract inhibited the translation of the reporter cRNA by 75% (the range of inhibition was between 50 and 75% in all experiments). The inhibitory activity of the 24-h extract was completely abrogated by anti-eIF4G (translation was restored to between 100 and 105% of control values in replicate experiments) but not by the control anti-GST antibody. We stress that while the anti-eIF4G antibody slightly inhibits basal translation of Cp, it greatly stimulates Cp translation in the presence of the cytosolic inhibitor. Therefore our results suggest a requirement of eIF4G for translation silencing in the presence of the cytosolic inhibitor (as well as for optimal translation in the absence of the inhibitor). Together, the results indicate that in addition to the requirement for a poly(A) tail and PABP, a third element of mRNA circularization, eIF4G, is required for translational silencing of Cp mRNA.

FIG. 7.

Requirement for eIF4G in the transcript-specific translational silencing of the polyadenylated chimeric reporter transcript. (Upper panel) A capped transcript containing luciferase upstream of the Cp 3′-UTR and a 30-nt poly(A) tail [cap-Luc-Cp 3′-UTR–poly(A)] was prepared by in vitro transcription in the presence of the cap analog, m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G. Rabbit reticulocyte lysates were preincubated for 15 min with 1 μl of polyclonal rabbit antiserum against human eIF4G or rabbit anti-GST antiserum as a control. Gel-purified cRNA transcript (100 ng) was subjected to in vitro translation in the presence of [35S]methionine and cytosolic extracts (4 mg of protein) from IFN-γ-treated U937 cells for 60 min at 30°C. A cRNA transcript encoding T7 gene 10 (100 ng) was simultaneously translated as a control. Newly synthesized, 35S-labeled luciferase and T7 gene 10 were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the radiolabeled bands were detected by fluorography (indicated by arrows). (Lower panel) The relative rate of Luc synthesis was quantitated by densitometry and normalized by division by T7 gene 10 synthesis under each condition. Ab, antibody.

DISCUSSION

Interactions between trans-acting RNA-binding proteins and cis-acting elements in a transcript UTR can markedly influence the global and transcript-specific translational efficiency (9, 45). Given the proximity of elements in the 5′-UTR to the translation initiation site, it is at least conceptually straightforward that 5′-UTR-binding proteins can influence initiation. A recognized paradigm of this class of translational control is the binding of the iron-responsive element-binding protein to the cognate element in the ferritin 5′-UTR (30, 41). More recent studies suggest that trans-acting proteins bind to elements in the 3′-UTR of several mRNAs and that this binding strongly influences (usually represses) translation initiation (1, 7, 18, 27, 33). The mechanism by which binding of a protein(s) to the 3′-UTR influences translation initiation at the distant 5′-UTR is not clearly understood. An attractive framework is provided by recent studies suggesting that mRNA may be circularized (9, 37) by protein-protein and protein-mRNA interactions at the 5′ and 3′ termini (48, 49). Circularized mRNA has been observed directly by atomic force microscopy (52). However, there is little evidence that transcript circularization is important in translational control mechanisms.

Poly(A) tail and translational control.

There is limited information about the mechanisms of 3′-UTR-mediated translational control, and specifically on the requirement for the poly(A) tail. Several recent studies have provided clues to these regulatory mechanisms. In Drosophila, a gender-specific translational control mechanism regulates dosage compensation by hypertranscription of genes on the single male X chromosome (8). Hypertranscription is mediated by a complex containing male-specific-lethal (msl) gene products including MSL-2. Expression of msl-2 is translationally silenced in females by binding of the female-specific RNA-binding protein Sex-lethal to binding sites in the msl-2 5′- and 3′-UTRs. The cooperative binding of msl-2 to both UTRs suggests that circularization may be required for this translational control mechanism. However, unlike the results of our own studies, translational silencing of msl-2 was found to be poly(A) tail independent (8). It is not known whether msl-2 participates in transcript circularization or if other factors e.g., Drosophila homologues of PABP and eIF4G, are required for circularization (and translational control). A second example of translational control studied in depth is sex determination in the Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodite. The female development gene tra-2 is translationally repressed by binding of GLD-1, a germ line-specific RNA-binding protein, to the TGE element present in the tra-2 3′-UTR; this silencing is required for the onset of spermatogenesis (4, 19, 50). A recent study suggests that tra-2 mRNA requires a poly(A) tail for translational silencing by GLD-1 (50). The studies also show that binding of GLD-1 to the TGE element causes rapid removal of the poly(A) tail (50). In our own studies, we show that the poly(A) tail is required for translational silencing of Cp mRNA in IFN-γ-treated U937 cells. We have shown this for endogenous cellular Cp mRNA as well as for chimeric RNA transcripts containing Luc upstream of the Cp 3′-UTR. These studies extend those with C. elegans to show the importance of poly(A) in translational control in a mammalian system. We suggest that translational control should be added to the assemblage of well-known regulatory functions of poly(A), i.e., mRNA stabilization, translation efficiency, and transport (12, 43, 53).

Mechanisms of 3′-UTR-mediated translational control.

We have considered two mechanisms by which cytosolic extracts from IFN-γ-treated U937 cells could inhibit Cp mRNA translation. Several avenues of evidence argue against the first mechanism, i.e., that the inhibitory factor blocks transcript circularization, thereby inhibiting Cp translation (Fig. 1B). First, we showed experimentally that the inhibitory extract does not block the binding of PABP to either poly(A) or eIF4G. Furthermore, the fact that the chimeric Luc-Cp 3′-UTR cRNA construct is translated at a high rate, even in the absence of a poly(A) tail, indicates that transcript circularization is not required for efficient translation (in reticulocyte lysates). A corollary to this observation is that mere disruption of transcript circularization is unlikely to substantially inhibit Cp translation in reticulocyte lysates. According to the second proposed mechanism, the inhibitory factor does not block circularization but, rather, requires it. All of the experiments described here are consistent with this mechanism. First, PABP interacts with the poly(A) tail of Luc-Cp 3′-UTR and with eIF4G, even in the presence of the inhibitory cytosolic factor. Second, three elements required for transcript circularization, i.e., the poly(A) tail, PABP, and eIF4G, are all required for translational silencing of Cp by IFN-γ. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a translational control system that requires these elements.

Our experiments do not shed light on the specific translation events which may be negatively affected by the Cp translation inhibitor. Our previous work indicated that translation initiation was blocked by IFN-γ since Cp mRNA shifted from the polyribosomes to the nonpolyribosomal fraction (25). Together, our data suggest that transcript circularization brings the inhibitory Cp 3′-UTR-binding protein(s) into the vicinity of the initiation complex, where it may negatively influence complex assembly by competitive interactions with a specific initiation factor or by steric hindrance (Fig. 1C). Alternatively, transcript circularization may bring the inhibitor near the initiation codon and prevent assembly of the 60S and 40S ribosomal subunits into a translation-competent 80S ribosome. The latter mechanism has been recently described for silencing of 15-lipoxygenase translation (32). In that study, a silencing complex bound to the 15-lipoxygenase 3′-UTR was shown to permit 40S ribosomal subunit recruitment and scanning to the AUG codon; however, formation of a competent 80S ribosome was blocked. The requirement for the poly(A) tail, PABP, or eIF4G in translational control of 15-lipoxygenase was not investigated, so it is not clear whether the inhibition of this mRNA and Cp utilize similar control points. Additional studies are necessary to identify the specific cis elements and trans factors involved in the translational silencing of Cp and to identify the specific 5′-terminal factors targeted. Studies of other systems will show whether our observations of Cp regulation can be extended to other translational control systems. In that case, transcript circularization may have evolved not only to increase the rate of global translation initiation but also as an essential structural determinant for transcript-specific translational control.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants HL-29582 and HL-52692 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (to P.L.F.), and by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association, National Affiliate (to B.M.).

We gratefully acknowledge Gideon Dreyfuss and Naoyuki Kataoka of Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of Pennsylvania, for providing monoclonal antibody made against human PABP and for providing monoclonal antibody Sp2/O; we also thank Matthias Hentze of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory for providing the 15-lipoxygenase 3′-UTR construct.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black B L, Lu J, Olson E N. The MEF2A 3′ untranslated region functions as a cis-acting translational repressor. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2756–2763. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borman A M, Michel Y M, Kean K M. Biochemical characterisation of cap-poly(A) synergy in rabbit reticulocyte lysates: the eIF4G-PABP interaction increases the functional affinity of eIF4E for the capped mRNA 5′-end. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:4068–4075. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.21.4068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burd C G, Matunis E L, Dreyfuss G. The multiple RNA-binding domains of the mRNA poly(A)-binding protein have different RNA-binding activities. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3419–3424. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.7.3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clifford R, Lee M H, Nayak S, Ohmachi M, Giorgini F, Schedl T. FOG-2, a novel F-box containing protein, associates with the GLD-1 RNA binding protein and directs male sex determination in the C. elegans hermaphrodite germline. Development. 2000;127:5265–5276. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.24.5265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colgan D F, Manley J L. Mechanism and regulation of mRNA polyadenylation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deo R C, Sonenberg N, Burley S K. X-ray structure of the human hyperplastic discs protein: an ortholog of the C-terminal domain of poly(A)-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4414–4419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071552198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu L, Benchimol S. Participation of the human p53 3′UTR in translational repression and activation following γ-irradiation. EMBO J. 1997;16:4117–4125. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gebauer F, Corona D F, Preiss T, Becker P B, Hentze M W. Translational control of dosage compensation in Drosophila by Sex-lethal: cooperative silencing via the 5′ and 3′ UTRs of msl-2 mRNA is independent of the poly(A) tail. EMBO J. 1999;18:6146–6154. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.21.6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gingras A C, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gitlin J D. Transcriptional regulation of ceruloplasmin gene expression during inflammation. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6281–6287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray N K, Coller J M, Dickson K S, Wickens M. Multiple portions of poly(A)-binding protein stimulate translation in vivo. EMBO J. 2000;19:4723–4733. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosset C, Chen C Y, Xu N, Sonenberg N, Jacquemin-Sablon H, Shyu A B. A mechanism for translationally coupled mRNA turnover: interaction between the poly(A) tail and a c-fos RNA coding determinant via a protein complex. Cell. 2000;103:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Görlach M, Burd C G, Dreyfuss G. The mRNA poly(A)-binding protein: Localization, abundance, and RNA-binding specificity. Exp Cell Res. 1994;211:400–407. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris Z L, Durley A P, Man T K, Gitlin J D. Targeted gene disruption reveals an essential role for ceruloplasmin in cellular iron efflux. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10812–10817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hew Y, Lau C, Grzelczak Z, Keeley F W. Identification of a GA-rich sequence as a protein-binding site in the 3′-untranslated region of chicken elastin mRNA with a potential role in the developmental regulation of elastin mRNA stability. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24857–24864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoshino S, Imai M, Kobayashi T, Uchida N, Katada T. The eukaryotic polypeptide chain releasing factor (eRF3/GSPT) carrying the translation termination signal to the 3′-poly(A) tail of mRNA. Direct association of erf3/GSPT with polyadenylate-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16677–16680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imataka H, Gradi A, Sonenberg N. A newly identified N-terminal amino acid sequence of human eIF4G binds poly(A)-binding protein and functions in poly(A)-dependent translation. EMBO J. 1998;17:7480–7489. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izquierdo J M, Cuezva J M. Control of the translational efficiency of β-F1-ATPase mRNA depends on the regulation of a protein that binds the 3′ untranslated region of the mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5255–5268. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jan E, Motzny C K, Graves L E, Goodwin E B. The STAR protein, GLD-1, is a translational regulator of sexual identity in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 1999;18:258–269. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.1.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khaleghpour K, Kahvejian A, Crescenzo G D, Roy G, Svitkin Y V, Imataka H, O'Connor-McCourt M, Sonenberg N. Dual interactions of the translational repressor Paip2 with the poly(A) binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5200–5213. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5200-5213.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klausner R D, Rouault T A, Harford J B. Regulating the fate of mRNA: the control of cellular iron metabolism. Cell. 1993;72:19–28. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90046-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai W S, Carballo E, Strum J R, Kennington E A, Phillips R S, Blackshear P J. Evidence that tristetraprolin binds to AU-rich elements and promotes the deadenylation and destabilization of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4311–4323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mangus D A, Amrani N, Jacobson A. Pbp1p, a factor interacting with Saccharomyces cerevisiae poly(A)-binding protein, regulates polyadenylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7383–7396. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, Hershey J W. Origins and targets of translational control. In: Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazumder B, Fox P L. Delayed translational silencing of ceruloplasmin transcript in gamma interferon-activated U937 monocytic cells: role of 3′ untranslated region. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6898–6905. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazumder B, Mukhopadhyay C K, Prok A, Cathcart M K, Fox P L. Induction of ceruloplasmin synthesis by IFN-γ in human monocytic cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:1938–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mbongolo Mbella E G, Bertrand S, Huez G, Octave J N. A GG nucleotide sequence of the 3′ untranslated region of amyloid precursor protein mRNA plays a key role in the regulation of translation and the binding of proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4572–4579. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4572-4579.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michel Y M, Poncet D, Piron M, Kean K M, Borman A M. Cap-poly(A) synergy in mammalian cell-free extracts. Investigation of the requirements for poly(A)-mediated stimulation of translation initiation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32268–32276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyajima H, Nishimura Y, Mizoguchi K, Sakamoto M, Shimizu T, Honda N. Familial apoceruloplasmin deficiency associated with blepharospasm and retinal degeneration. Neurology. 1987;37:761–767. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.5.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muckenthaler M, Gray N K, Hentze M W. IRP-1 binding to ferritin mRNA prevents the recruitment of the small ribosomal subunit by the cap-binding complex eIF4F. Mol Cell. 1998;2:383–388. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osaki S, Johnson D A, Frieden E. The possible significance of the ferrous oxidase activity of ceruloplasmin in normal human serum. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:2746–2751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ostareck D H, Ostareck-Lederer A, Shatsky I N, Hentze M W. Lipoxygenase mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: the 3′UTR regulatory complex controls 60S ribosomal subunit joining. Cell. 2001;104:281–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ostareck D H, Ostareck-Lederer A, Wilm M, Thiele B J, Mann M, Hentze M W. mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: hnRNP K and hnRNP E1 regulate 15-lipoxygenase translation from the 3′ end. Cell. 1997;89:597–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostareck-Lederer A, Ostareck D H, Standart N, Thiele B J. Translation of 15-lipoxygenase mRNA is inhibited by a protein that binds to a repeated sequence in the 3′ untranslated region. EMBO J. 1994;13:1476–1481. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pages G, Berra E, Milanini J, Levy A P, Pouysségur J. Stress-activated protein kinases (JNK and p38/HOG) are essential for vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA stability. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26484–26491. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002104200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piecyk M, Wax S, Beck A R, Kedersha N, Gupta M, Maritim B, Chen S, Gueydan C, Kruys V, Streuli M, Anderson P. TIA-1 is a translational silencer that selectively regulates the expression of TNF-α. EMBO J. 2000;19:4154–4163. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preiss T, Hentze M W. From factor to mechanism: translation and translational control in eukaryotes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999;9:515–521. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Proweller A, Butler J S. Ribosome concentration contributes to discrimination against poly(A)− mRNA during translation initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6004–6010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.6004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richter J D. Dynamics of poly(A) addition and removal during development. In: Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 481–503. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez-Pascual F, Hausding M, Ihrig-Biedert I, Furneaux H, Levy A P, Forstermann U, Kleinert H. Complex contribution of the 3′-untranslated region to the expressional regulation of the human inducible nitric-oxide synthase gene. Involvement of the RNA-binding protein HuR. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26040–26049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910460199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rouault T A, Hentze M W, Caughman S W, Harford J B, Klausner R D. Binding of a cytosolic protein to the iron-responsive element of human ferritin messenger RNA. Science. 1988;241:1207–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.3413484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rydé L. Ceruloplasmin. In: Lontie R, editor. Copper proteins and copper enzymes. III. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1984. pp. 37–100. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sachs A B, Sarnow P, Hentze M W. Starting at the beginning, middle, and end: translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sachs A B, Varani G. Eukaryotic translation initiation: there are (at least) two sides to every story. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:356–361. doi: 10.1038/75120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Standart N, Jackson R J. Regulation of translation by specific protein/mRNA interactions. Biochimie. 1994;76:867–879. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stein I, Itin A, Einat P, Skaliter R, Grossman Z, Keshet E. Translation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by internal ribosome entry: implications for translation under hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3112–3119. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.St Johnston D. The intracellular localization of messenger RNAs. Cell. 1995;81:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tarun S Z, Sachs A B. Association of the yeast poly(A) tail binding protein with translation initiation factor eIF-4G. EMBO J. 1996;15:7168–7177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarun S Z, Wells S E, Deardorff J A, Sachs A B. Translation initiation factor eIF4G mediates in vitro poly(A) tail-dependent translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9046–9051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson S R, Goodwin E B, Wickens M. Rapid deadenylation and poly(A)-dependent translational repression mediated by the Caenorhabditis elegans tra-2 3′ untranslated region in Xenopus embryos. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2129–2137. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.6.2129-2137.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wakiyama M, Imataka H, Sonenberg N. Interaction of eIF4G with poly(A)-binding protein stimulates translation and is critical for Xenopus oocyte maturation. Curr Biol. 2001;10:1147–1150. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00701-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wells S E, Hillner P E, Vale R D, Sachs A B. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol Cell. 1998;2:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wickens M, Anderson P, Jackson R J. Life and death in the cytoplasm: messages from the 3′ end. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:220–232. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wickens M, Kimble J, Strickland S. Translational control of developmental decisions. In: Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 411–450. [Google Scholar]