Abstract

Pseudomembranous colitis is severe inflammation of the inner lining of the colon due to anoxia, ischemia, endothelial damage, and toxin production. The majority of cases of pseudomembranous colitis are due to Clostridium difficile. However, other causative pathogens and agents have been responsible for causing a similar pattern of injury to the bowel with the endoscopic appearance of yellow-white plaques and membranes on the mucosal surface of the colon. Common presenting symptoms and signs include crampy abdominal pain, nausea, watery diarrhea that can progress to bloody diarrhea, fever, leukocytosis, and dehydration. Negative testing for Clostridium difficile or failure to improve on treatment should prompt evaluation for other causes of pseudomembranous colitis. Bacterial infections other than Clostridium difficile, Viruses such as cytomegalovirus, parasitic infections, medications, drugs, chemicals, inflammatory diseases, and ischemia are other differential diagnoses to look out for in pseudomembranous colitis. Complications of pseudomembranous colitis include toxic megacolon, hypotension, colonic perforation with peritonitis, and septic shock with organ failure. Early diagnosis and treatment to prevent progression are important. The central perspective of this paper is to provide a concise review of the various etiologies for pseudomembranous colitis and management per prior literature.

Keywords: Infections, Pseudomembranous colitis, Gastroenteritis, Gastrointestinal diseases, Non-Clostridium difficile, Enterocolitis, Digestive system diseases

Core Tip: Pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) is mostly caused by Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). The incidence of CDI-related PMC is 3%-8% and is increasing. Other than CDI, ischemia, infections, medications, and inflammatory conditions can cause PMC. Infections from S. aureus, E. coli, Klebsiella, and Strongyloidiasis may also cause PMC. Non-infectious causes of PMC include chemical endoscope cleaning agents, intestinal ischemia, drug abuse from cocaine, inflammatory bowel disease, and microscopic colitis. Understanding various causes of pseudomembranous colitis helps avoid over usage of antibiotics and focus on targeted therapy and early diagnosis. This is a concise review of non-CDI pseudomembranous colitis.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomembranous colitis is an acute inflammation of the colon. It is primarily due to the overgrowth of the bacterium clostridium difficile and the production of toxins that damage the colonic mucosa. Prior antibiotic usage causes an imbalance in gut bacteria and predisposes to Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) (Figure 1). Common medications associated with it include Penicillin, clindamycin, cephalosporins, trimethoprim-Sulphamethoxazole, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and fluoroquinolones. Toxin A (Enterotoxin) and Toxin B (Cytotoxin) are the causative agents for triggering the immune system and leading to inflammation in the colon[1]. Over the years, other causes of pseudomembranous colitis have been increasingly identified. Pseudomembranous colitis is named due to ulceration and inflammation of the colonic mucosa with the formation of pseudomembranes. The absence of Clostridium Difficile on testing or failure of response to Clostridium difficile treatment in a patient with pseudomembranes on colonoscopy should encourage physicians to evaluate for other causes of colitis. Prior literature provides evidence of pseudomembranous colitis from inflammatory causes, non-clostridial infections, chemical agents, drugs, and ischemia. It is important to evaluate these causes after the failure of antibiotic therapy to avoid prolonged, unnecessary Clostridium difficile treatment. Symptoms of pseudomembranous colitis include watery diarrhea with pus or mucus in stool. This is the commonest symptom in the majority of patients, followed by abdominal pain/cramps and fever. Leukocytosis is the commonest sign in these patients. Symptoms can start as early as a few days and up to 6 wk after starting antibiotics due to alteration in the gut flora[2].

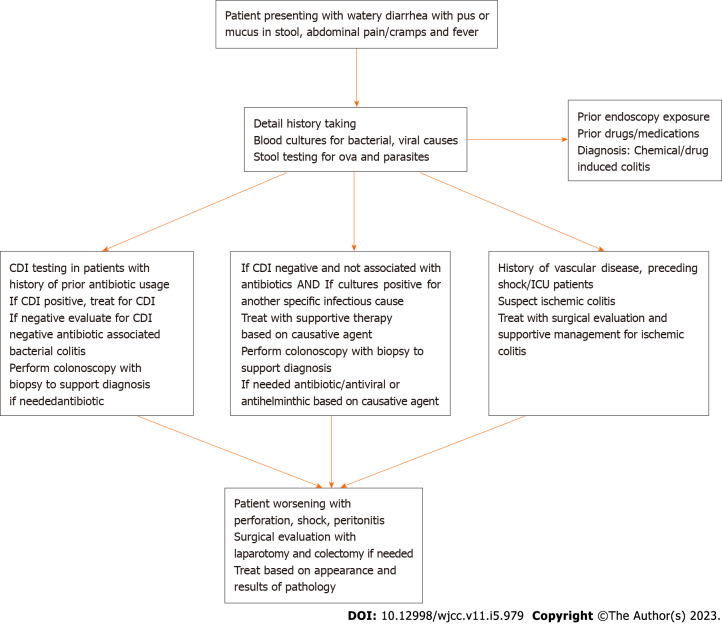

Figure 1.

Causes for Non-Clostridium difficile colitis.

Pseudomembranes are composed of mucus, fibrinous material, inflammatory cells (neutrophils), and cellular debris over the colonic mucosa with mucosal damage of varying degrees. Computed tomography imaging in these patients shows diffuse mucosal wall thickening. In this brief review, we highlight various agents from previous literature which cause pseudomembranous colitis and present their management options.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

A literature review was conducted in PubMed and Google Scholar to identify articles discussing Pseudomembranous colitis from inception till December 2022. We searched using a combination of free text words, including pseudomembranous colitis, non-clostridium, parasitic, ischemic, Chemical, strongyloidiasis, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), Microscopic, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Amoeba, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Cocaine, chemical, and glutaraldehyde. We reviewed studies published in the English language. Relevant articles were analyzed and presented in the review.

NON-CLOSTRIDIUM DIFFICILE COLITIS

Infections

Other than Clostridium difficile other bacterial infections, Viral, parasitic and fungal infections (Aspergillus[3]) have been implicated in antibiotic-associated colitis.

Bacterial infections

Staphylococcus aureus colitis: Before Clostridium difficile emerged as the commonest cause of antibiotic-associated colitis in the 1970s, staphylococcus was implicated as the commonest cause after antibiotic usage or abdominal surgery. The author describes a patient who developed MRSA proctocolitis with profuse diarrhea after Whipple's procedure that improved on oral and IV vancomycin for 14 d. C diff testing was negative twice in this patient[4]. The prior literature describes antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic and non-hemorrhagic colitis from Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus[5-7]. Pressly et al[8] describe a 37-year-old female with Crohn's disease who developed hemorrhagic colitis after staphylococcal food poisoning and subsequent use of antibiotics. Flexible sigmoidoscopy showed segmental pseudomembranes from the rectum to the sigmoid colon, and CDI infection was negative on testing twice. Similar pseudomembranous colitis with non-bloody diarrhea has been described by Kalakonda et al[9]. Patients recovered on oral vancomycin for 7-14 d[5,8,9]. In a systematic review conducted by Gururangan et al[4]. On staphylococcal enterocolitis, antibiotics (74%) were the most common cause of Staphylococcus aureus colitis, followed by recent gastrointestinal surgeries (18%) and inflammatory bowel disease (2%)[4] Froberg et al[10] reported antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis from simultaneous infection with CDI and MRSA. An autopsy after the patient's death revealed two distinct patterns of pseudomembranes from both organisms observed in the ileum and cecum. Clostridium difficile lesions were confined to the cecum and colon and showed 1-4 mm-sized yellow-colored, well-defined, tightly attached pseudomembranous lesions. The lesions from Staphylococcus aureus were located in the small intestine. They were yellowish-green, patches that covered the circumference of the mucosa and were loosely adherent. The mucosa was edematous and erythematous. Histopathology in Staphylococcal colitis showed extensive pseudomembranes consisting of necrosis, fibrin deposition, predominant polymorphonuclear cells containing phagocytes with bacteria, and clusters of gram-positive cocci on the luminal surface. Clostridium difficile colitis histopathology showed clearly defined pseudomembranes with necrosis, fibrin, mucin deposition and mixed inflammatory cell infiltrates with normal adjacent mucosa. Enterotoxins are responsible for staphylococcal pseudomembranous colitis. Toxic shock syndrome toxins (TSST-1) are less commonly responsible from prior literature. In a systematic review by Iwata et al[11] enterotoxins, TSST-1, Protease B, and Leucotoxins were identified in 18 studies in the literature. Another differentiating feature of Staphylococcus aureus colitis is the presence of bacteremia. Bacteremia in Clostridium difficile colitis is rare and usually follows a gastrointestinal infection or surgery. Death from staphylococcal enterocolitis has declined over the years due to accessibility to vancomycin approved by the US Food and drug administration for Staphylococcal enterocolitis[4].

Klebsiella Oxytoca : In a systematic review by Motamedi et al[12] Klebsiella, oxytoca was the most common cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients, with a prevalence of 27%. Akanbi et al[13] describe a patient who presented with hemorrhagic colitis after taking amoxiclav for 5 d a week before the presentation. Cultures were positive only for Klebsiella Oxytoca. The patient improved symptomatically after the withdrawal of antibiotics and supportive management. Few other cases are described in the literature that resulted after the use of antibiotics and recovered after discontinuation and with conservative treatment[14,15]. Few deaths with colitis from Klebsiella oxytoca are reported. Nagamura et al[16] described a patient who died of Klebsiella Oxytoca pseudomembranous colitis. Klebsiella Oxytoca does not have an enterotoxin like CDI but secretes cytotoxins that may play a role in pseudomembranous colitis[17].

Escherichia Coli : Kendrick et al[18] describe a 59-year-old man who developed pseudomembranous colitis during the national outbreak of Escherichia coli O157: H7 from ingesting contaminated food during an outbreak. The patient required colectomy due to worsening infection. Pathology identified fibrinous and inflammatory pseudo membranes from the cecum to the proximal rectum. Another case report by Kennedy et al[19] describes a patient who developed hemolytic uremic syndrome and neurological sequelae. The pseudomembranes extended from the mid-transverse colon to the rectum, and the biopsy revealed fibrinous exudates and polymorphonuclear cells. The intervening intact mucosa showed crypt inflammation and abscesses. Both patients recovered from the infection with supportive management. Escherichia coli produces Shiga-like toxins that can cause pseudomembranous types of colitis. Patients recovered off antibiotics[18-20] in most of the cases presented in the literature.

VIRUSES

CMV

Multiple cases of pseudomembranous colitis from CMV have been described in the literature[21,22-24]. Colitis refractory to CDI treatment leads to the authors testing for other causes of pseudomembranous colitis. Positive CMV Immunohistochemical staining or the presence of inclusion bodies on colonic mucosal biopsy specimens establishes the diagnosis. The pseudomembranes are described as similar to Clostridium difficile colitis[25,26]. Chan et al[27] Described eight patients with colitis that were refractory to oral metronidazole and diagnosed as CMV colitis on colonic mucosal biopsy. Four of these patients had pseudomembranes on colonoscopy. Three of the patients with pseudomembranes also had concurrent CDI with toxin positive on testing. The authors recommend initiating early antiviral therapy before definitive diagnosis by biopsy in patients with a high risk of suspicion and stool or blood polymerase chain reaction positive for CMV polymerase chain reaction. This is due to the high risk of rapid progress and the development of complications in untreated patients[28]. Factors associated with poor prognosis include older age, surgical requirement, male gender, late presentation, ulcerative colitis, and immune status. Galiatsatos et al[29] report a mortality rate of > 30% in patients aged > 55 years with CMV colitis. In a study by Le et al[30] on CMV, colitis mortality was 26% in patients and did not differ based on immune status. Treatment includes ganciclovir or Foscarnet and is necessary, particularly in older patients or those with immune compromise.

CORONAVIRUS

Timerbulatov et al[31] described 19 cases of pseudomembranous colitis that occurred after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection. The average time to development of colitis after a COVID-19 infection was 19 d. Histology of the lesions revealed necrosis extending up to the entire thickness of the colon in some cases. Histopathology revealed crypt destruction, fibrinoid deposition, and polymorphonuclear cell infiltration. Additional findings included necrosis of the neural plexus and vascular walls with hyaline deposition, probably from ischemia due to COVID-19. All patients underwent subtotal colectomy with ileostomy. Jabbar et al[32] described pseudomembranous colitis in a patient with COVID-19. Histology showed inflammatory cells, fibrin, and mucin deposits along with necrotic epithelial cells. The authors hypothesize that the prothrombotic nature of COVID-19 can predispose to intestinal ischemia complicated by pseudomembranous colitis.

PARASITIC INFECTIONS

Parasitic infections are common in patients living or traveling to endemic regions or immunocompromised.

Strongyloides stercoralis

Strongyloides stercoralis causing eosinophilic granulomatous enterocolitis with colonic ulcerations was described by Gutierrez et al[33] in 6 patients. Symptoms are similar to ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease, with abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting[33,34]. Immunosuppression from HIV and treatment with steroids for other conditions predispose to hyper infection with Strongyloides. Patients recovered on a course of Thiabendazole. The presence of dead larvae in the colonic mucosal biopsy with intense surrounding inflammatory reaction is a characteristic finding[33,34].

Entamoeba Histolytica

In a retrospective study conducted by Roure et al[35] on 50 patients with amoebic colitis, international travel, immigrants, and immunosuppression were common risk factors for acquiring infection. Diarrhea and abdominal pain were the commonest presenting symptoms. Pathology showed exudates containing amoeba and mucosal thickening with ulcerations which can be classic geographic, flask-shaped, and deep ulcers leading to necrosis and perforation of the intestinal wall. Chaturvedi et al[36] described 30 cases of fulminant amoebic colitis with pathology showing pseudomembranes, geographical colonic ulcers, and lesions mimicking inflammatory bowel disease. 17 patients died due to septicemia and shock due to perforation despite surgical intervention. Colonic mucosal biopsies in these studies revealed trophozoites on histology[35-37]. Treatment with metronidazole or tinidazole was curative. Some patients required treatment with luminal anti-parasitic medications. Tomino et al[37] described a patient with colonic perforation and fulminant necrotizing amoebic colitis requiring emergent subtotal colectomy and enterectomy. The patient died from sepsis, and disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiple organ failure ten days post-procedure.

INFLAMMATORY CONDITIONS

Collagenous colitis

Yuan et al[38] described 10 female patients with clinical and histological collagenous colitis who presented with chronic watery diarrhea. Prior usage of non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and estrogen was identified. Pseudomembranes and ulcerations were identified in these patients on endoscopy. This establishes that pseudomembranous colitis is a pattern of injury that occurs due to toxic and ischemic processes and is not a separate diagnosis in itself. These patients recovered after stopping NSAIDs on conventional treatment with anti-inflammatory and anti-diarrheal agents[38-40].

IBD

Pseudomembranous colitis can occur in patients with IBD during a flare with or without superimposed causative factors such as infections, medication, and drug usage[41].

Kilincalp and Berdichevski reported pseudomembranous colitis in patients with a history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and a lack of exposure to antibiotics. The patient had a positive CDI on testing[42,43]. Another report of pseudomembranous colitis in a patient with ulcerative colitis and CMV-superimposed infection is described[44]. A prior study by Horin et al[45] describes that 13% of hospitalized IBD patients with CDI infection have pseudomembranes on endoscopy, and outcomes in these patients are not different from others. This further establishes that pseudomembranes are an endoscopic and pathological entity that can occur due to various underlying causes.

Medications, illicit drugs, and chemicals

NSAIDs[46,47], dextroamphetamine[48,49], Alosetron[50], Voriconazole[51], and drugs such as cocaine are responsible for a pseudomembranous type of colitis.

Cocaine

Non-occlusive ischemia of the bowel in patients with no cardiac risk factors should guide clinicians to suspect cocaine-induced colitis[52-55]. Ellis et al[56] identified 18 patients with cocaine colitis who presented within three days of cocaine use. The proximal colon was predominantly involved, and the majority of the patients recovered with supportive management. 2 out of 4 patients who underwent laparotomy died due to peritonitis. Fishel et al[54] and Leth et al[57] described patients' superficial ulcerations, edema, and yellow fibrinous material. Histopathology revealed findings consistent with ischemic pseudomembranous colitis.

Chemicals

Chemicals like glutaraldehyde and hydrogen peroxide can cause acute retro colitis after endoscopy procedures. Patients present with acute onset of abdominal pain, fever, and rectal bleeding after the procedure. Deficiencies in endoscopy equipment disinfection procedures should be looked into if outbreaks occur after endoscopy in patients[58-61]. Endoscopic examination shows fibrin and inflammatory cell exudate with ischemic injury. The colitis appearance is similar to ischemic colitis. Conservative treatment with bowel rest and hydration results in the improvement of symptoms[60,62,63]. Ensuring adequate cleaning of the channels of endoscope before drying prevents this condition. The colitis appearance is similar to ischemic colitis.

Ischemia

Refractory CDI treatment, particularly for those with a history of vascular diseases, should raise suspicion of ischemic colitis. Ischemic colitis is commonly seen in patients > 60 years of age due to predisposing risk factors such as atherosclerosis, small vessel disease, and vascular occlusion. Prolonged hypotension resulting in ischemia can also cause pseudomembranous colitis. Right-sided colon supplied by the superior mesenteric artery is prone to transient non-occlusive ischemia during episodes of hypotension or low flow states. Early ischemic changes in the colonic mucosal include punctate hemorrhages and pseudomembranes. With the progression to severe ischemic injury, the pseudomembranes become confluent, and during resolution, they resemble inflammatory bowel disease with patchy ulcerations[64,65]. Management includes bowel rest, intravenous fluids, gastric decompression, and antibiotics to prevent bacterial translocation. Discontinuation of any precipitating agents such as NSAIDs is necessary.

Diagnosis and treatment

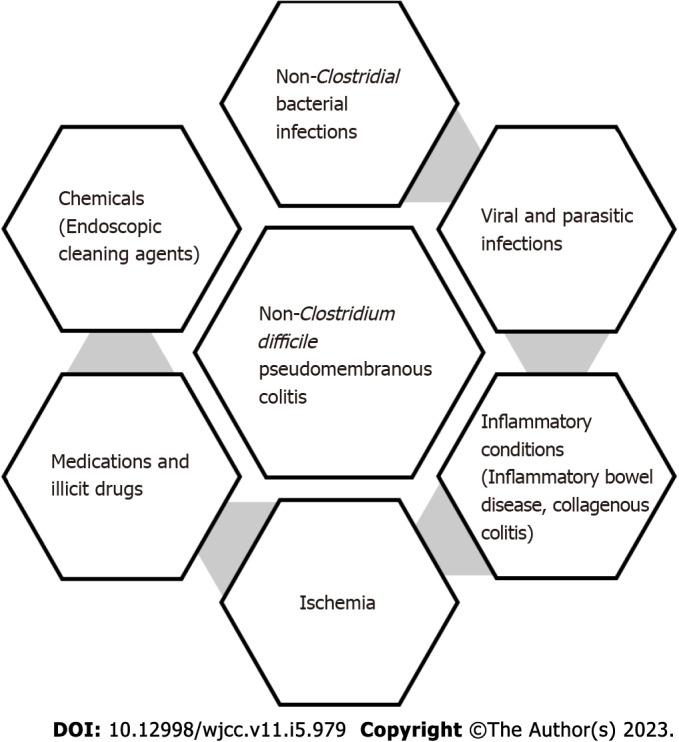

Since CDI causes the majority of the cases of pseudomembranous colitis, Initial management includes workup for Clostridial infections. Enzyme immune assay for Glutamate dehydrogenase antigen (GDH) test and Toxin A and B testing is the first step to identifying colonization Vs. Infection. The presence of positive GDH and Toxin testing indicates infection. Indeterminate results can be followed by nucleic acid amplification testing. Early treatment if suspicion for infection is high and in hemodynamically unstable patients while waiting for workup results should be done. Failure of treatment for CDI or negative cultures and toxin testing should be followed by exploration for other causes of colitis. Detailed history taking in patients can provide clues to causative factors and aid in diagnosis. Stool testing to identify infectious causes other than CDI can be done in patients with signs and symptoms. Treatment varies depending on the cause of colitis. Table 1 shows the management for pseudomembranous colitis based on etiology per prior literature and evidence. 30-d All-cause Mortality in CDI is around 9%-38%. Mortality in the various causes of non-Clostridium colitis depends on the cause, age, the extent of involvement of the colon, and progression to complications such as perforation, toxic megacolon, bacteremia, and shock. Patients requiring surgery generally had poorer prognoses. Poor prognosis in older patients could be due to a decline in humoral and cellular immunity and the existence of co-morbidities. Further research on the various causes and pathogenesis of pseudomembranous colitis, along with active reporting, is necessary to understand the true incidence of this condition and its management (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Treatment for various causes of pseudomembranous colitis per prior literature

|

Cause for pseudomembranous colitis

|

Treatment

|

| Staphylococcus | Vancomycin |

| Klebsiella Oxytoca | Withdrawal of antibiotics, conservative management |

| Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 | Withdrawal of antibiotics, supportive management |

| Cytomegalovirus | Anti-viral therapy |

| Strongyloides Stercoralis | Anti-helminthic agents |

| Entamoeba Histolytica | Nitroimidazoles |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Conventional IBD treatment |

| Collagenous colitis | Stop offending agents (NSAIDS), Supportive management |

| Medications, illicit drugs | Stop the causative drug, Supportive management |

| Chemicals (Endoscope cleaning agents) | Ensuring effective cleaning of endoscopy devices, Supportive management |

| Ischemia | Stop offending agent, bowel rest and decompression, intravenous fluids, antibiotics to prevent gut translocation of bacteria, surgical consultation |

IBD: Inflammatory bowel diseases; NSAIDS: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Figure 2.

Treatment for various causes of pseudomembranous colitis per prior literature. CDI: Clostridium difficile infection; ICU: Intensive care unit.

CONCLUSION

Pseudomembranous colitis is a pathological finding on endoscopy and is not only due to CDI. Infectious, inflammatory, Drug, and Ischemic causes should be investigated in a patient with endoscopic findings of pseudomembranous colitis and negative CDI on testing or refractory to CDI treatment. Initiating early management based on diagnosis results in the resolution of symptoms in most patients.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: November 2, 2022

First decision: January 3, 2023

Article in press: January 20, 2023

Specialty type: Medicine, general and internal

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ankrah AO, Netherlands; Ghimire R, Nepal; Meena DS, India S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Gowthami Sai Kogilathota Jagirdhar, Department of Medicine, Saint Michaels Medical Center, Newark, NJ 07102, United States.

Salim Surani, Department of Pulmonary, Critical Care & Pharmacy, Texas A&M University, Kingsville, TX 78363, United States. srsurani@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Srisajjakul S, Prapaisilp P, Bangchokdee S. Drug-induced bowel complications and toxicities: imaging findings and pearls. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2022;47:1298–1310. doi: 10.1007/s00261-022-03452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surawicz CM, McFarland LV. Pseudomembranous colitis: causes and cures. Digestion. 1999;60:91–100. doi: 10.1159/000007633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reynolds IS, O'Connell K, Fitzpatrick F, Masania R, Richardson M, McNamara DA. A Case of Primary Invasive Aspergillus Colitis Masquerading as Clostridium difficile Infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2016;17:262–263. doi: 10.1089/sur.2015.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gururangan K, Holubar MK. A Case of Postoperative Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Enterocolitis in an 81-Year-Old Man and Review of the Literature. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e922521. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.922521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergevin M, Marion A, Farber D, Golding GR, Lévesque S. Severe MRSA Enterocolitis Caused by a Strain Harboring Enterotoxins D, G, and I. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:865–867. doi: 10.3201/eid2305.161644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogers E, Dooley A, Vu S, Haq F, Ferderigos S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Colitis Secondary to Complicated Acute Diverticulitis: A Rare Case Report. Cureus . 2019;11:e5013. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estifan E, Nanavati SM, Kumar V, Vora A, Alziadat M, Sharaan A, Ismail M. Unusual Presentation of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Colitis Complicated with Acute Appendicitis. J Glob Infect Dis. 2020;12:34–36. doi: 10.4103/jgid.jgid_117_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pressly KB, Hill E, Shah KJ. Pseudomembranous colitis secondary to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-215225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalakonda A, Garg S, Tandon S, Vinayak R, Dutta S. A rare case of infectious colitis. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2016;4:328–330. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gov016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Froberg MK, Palavecino E, Dykoski R, Gerding DN, Peterson LR, Johnson S. Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium difficile cause distinct pseudomembranous intestinal diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:747–750. doi: 10.1086/423273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwata K, Doi A, Fukuchi T, Ohji G, Shirota Y, Sakai T, Kagawa H. A systematic review for pursuing the presence of antibiotic associated enterocolitis caused by methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motamedi H, Fathollahi M, Abiri R, Kadivarian S, Rostamian M, Alvandi A. A worldwide systematic review and meta-analysis of bacteria related to antibiotic-associated diarrhea in hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0260667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akanbi O, Saleem N, Soliman M, Pannu BS. Antibiotic-associated haemorrhagic colitis: not always Clostridium difficile. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-219915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sweetser S, Schroeder KW, Pardi DS. Pseudomembranous colitis secondary to Klebsiella oxytoca. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2366–2368. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann KM, Deutschmann A, Weitzer C, Joainig M, Zechner E, Högenauer C, Hauer AC. Antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis caused by cytotoxin-producing Klebsiella oxytoca. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e960–e963. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagamura T, Tanaka Y, Terayama T, Higashiyama D, Seno S, Isoi N, Katsurada Y, Matsubara A, Yoshimura Y, Sekine Y, Akitomi S, Sato K, Tsuda H, Saitoh D, Ikeuchi H. Fulminant pseudomembranous enterocolitis caused by Klebsiella oxytoca: an autopsy case report. Acute Med Surg. 2019;6:78–82. doi: 10.1002/ams2.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tse H, Gu Q, Sze KH, Chu IK, Kao RY, Lee KC, Lam CW, Yang D, Tai SS, Ke Y, Chan E, Chan WM, Dai J, Leung SP, Leung SY, Yuen KY. A tricyclic pyrrolobenzodiazepine produced by Klebsiella oxytoca is associated with cytotoxicity in antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:19503–19520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.791558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kendrick JB, Risbano M, Groshong SD, Frankel SK. A rare presentation of ischemic pseudomembranous colitis due to Escherichia coli O157:H7. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:217–219. doi: 10.1086/518990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy J, Simmonds L, Orme R, Doherty W. An unusual case of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection with pseudomembranous colitis-like lesions associated with haemolytic-uraemic syndrome and neurological sequelae. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-218586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kravitz GR, Smith K, Wagstrom L. Colonic necrosis and perforation secondary to Escherichia coli O157:H7 gastroenteritis in an adult patient without hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:e103–e105. doi: 10.1086/342889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chua YY, Ho QY, Ngo NT, Krishnamoorthy TL, Thangaraju S, Kee T, Wong HM. Cytomegalovirus-associated pseudomembranous colitis in a kidney transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2021;23:e13694. doi: 10.1111/tid.13694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurtz M, Morgan M. Concomitant Clostridium difficile colitis and cytomegalovirus colitis in an immunocompetent elderly female. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olofinlade O, Chiang C. Cytomegalovirus infection as a cause of pseudomembrane colitis: a report of four cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;32:82–84. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200101000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harano Y, Kotajima L, Arioka H. Case of cytomegalovirus colitis in an immunocompetent patient: a rare cause of abdominal pain and diarrhea in the elderly. Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:97–100. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S63771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sylva D, Villa P, García C, Pérez JC, Agudelo CA. Pseudomembranous colitis from cytomegalovirus infection. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:384. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Failure to Recognize the Diagnosis of Cytomegalovirus Colitis in an Immunocompetent Male: Need for Heightened Index of Suspicion. Surgical Infections Case Reports. 2016;1:156–160. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan KS, Yang CC, Chen CM, Yang HH, Lee CC, Chuang YC, Yu WL. Cytomegalovirus colitis in intensive care unit patients: difficulties in clinical diagnosis. J Crit Care. 2014;29:474.e1–474.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan KS, Lee WY, Yu WL. Coexisting cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients with Clostridium difficile colitis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2016;49:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galiatsatos P, Shrier I, Lamoureux E, Szilagyi A. Meta-analysis of outcome of cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent hosts. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:609–616. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2544-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le PH, Lin WR, Kuo CJ, Wu RC, Hsu JT, Su MY, Lin CJ, Chiu CT. Clinical characteristics of cytomegalovirus colitis: a 15-year experience from a tertiary reference center. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:1585–1593. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S151180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timerbulatov MV, Aitova LR, Grishina EE, Sakaev EM, Shchekin VS, Shchekin SV, Nizamutdinov TR. [Severe pseudomembranous colitis in patients with previous coronavirus infection] Khirurgiia (Mosk) 2022:53–60. doi: 10.17116/hirurgia202208153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jabbar A, Rana T, Ilyas G, Baqir A, Emechebe D, Agaronov M. A Rare Presentation of Pseudomembranous Colitis in a COVID-19 patient. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:S72–S73. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutierrez Y, Bhatia P, Garbadawala ST, Dobson JR, Wallace TM, Carey TE. Strongyloides stercoralis eosinophilic granulomatous enterocolitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:603–612. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199605000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al Samman M, Haque S, Long JD. Strongyloidiasis colitis: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:77–80. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199901000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roure S, Valerio L, Soldevila L, Salvador F, Fernández-Rivas G, Sulleiro E, Mañosa M, Sopena N, Mate JL, Clotet B. Approach to amoebic colitis: Epidemiological, clinical and diagnostic considerations in a non-endemic context (Barcelona, 2007-2017) PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212791. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaturvedi R, Gupte PA, Joshi AS. Fulminant amoebic colitis: a clinicopathological study of 30 cases. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91:200–205. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomino T, Ninomiya M, Minagawa R, Matono R, Yumi Oshiro, Kitahara D, Izumi T, Taniguchi D, Hirose K, Kajiwara Y, Minami K, Nishizaki T. Lethal multiple colon necrosis and perforation due to fulminant amoebic colitis: a surgical case report and literature review. Surg Case Rep. 2021;7:27. doi: 10.1186/s40792-020-01095-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan S, Reyes V, Bronner MP. Pseudomembranous collagenous colitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1375–1379. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Villanacci V, Cristina S, Muscarà M, Saettone S, Broglia L, Antonelli E, Salemme M, Occhipinti P, Bassotti G. Pseudomembranous collagenous colitis with superimposed drug damage. Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:735–739. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grunwald D, Mehta M, Sheth SG. Pseudomembranous Collagenous Colitis: A Case of Not-so-Microscopic Colitis. ACG Case Rep J. 2016;3:e187. doi: 10.14309/crj.2016.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farooq PD, Urrunaga NH, Tang DM, von Rosenvinge EC. Pseudomembranous colitis. Dis Mon. 2015;61:181–206. doi: 10.1016/j.disamonth.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kilinçalp S, Altinbaş A, Başar O, Deveci M, Yüksel O. A case of ulcerative colitis co-existing with pseudo-membranous enterocolitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:506–507. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berdichevski T, Barshack I, Bar-Meir S, Ben-Horin S. Pseudomembranes in a patient with flare-up of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): is it only Clostridium difficile or is it still an IBD exacerbation? Endoscopy. 2010;42 Suppl 2:E131. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1244045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chiba M, Abe T, Tsuda S, Ono I. Cytomegalovirus infection associated with onset of ulcerative colitis. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:40. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ben-Horin S, Margalit M, Bossuyt P, Maul J, Shapira Y, Bojic D, Chermesh I, Al-Rifai A, Schoepfer A, Bosani M, Allez M, Lakatos PL, Bossa F, Eser A, Stefanelli T, Carbonnel F, Katsanos K, Checchin D, de Miera IS, Reinisch W, Chowers Y, Moran GW European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO) Prevalence and clinical impact of endoscopic pseudomembranes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and Clostridium difficile infection. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romero-Gómez M, Suárez García E, Castro Fernández M. Pseudomembranous colitis induced by diclofenac. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;26:228. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199804000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gentric A, Pennec YL. Diclofenac-induced pseudomembranous colitis. Lancet. 1992;340:126–127. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90459-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beyer KL, Bickel JT, Butt JH. Ischemic colitis associated with dextroamphetamine use. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:198–201. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199104000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dirkx CA, Gerscovich EO. Sonographic findings in methamphetamine-induced ischemic colitis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1998;26:479–482. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199811/12)26:9<479::aid-jcu9>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedel D, Thomas R, Fisher RS. Ischemic colitis during treatment with alosetron. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:557–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kwon JC, Kang MK, Kim SH, Choi SM, Kim HJ, Min WS, Lee DG. A case of pseudomembranous colitis after voriconazole therapy. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52:863–865. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2011.52.5.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martínez-Vieira A, Camacho-Ramírez A, Díaz-Godoy A, Calvo-Durán A, Pérez-Alberca CM, de-la-Vega-Olías C, Muñoz-Arias G, Balbuena-García M, Najeb A, Vega-Ruiz V. Bowel ischaemia and cocaine consumption; case study and review of the literature. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2014;106:354–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fabra I, Roig JV, Sancho C, Mir-Labrador J, Sempere J, García-Ferrer L. [Cocaine-induced ischemic colitis in a high-risk patient treated conservatively] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;34:20–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fishel R, Hamamoto G, Barbul A, Jiji V, Efron G. Cocaine colitis. Is this a new syndrome? Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:264–266. doi: 10.1007/BF02554049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Linder JD, Mönkemüller KE, Raijman I, Johnson L, Lazenby AJ, Wilcox CM. Cocaine-associated ischemic colitis. South Med J. 2000;93:909–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellis CN, McAlexander WW. Enterocolitis associated with cocaine use. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2313–2316. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leth T, Wilkens R, Bonderup OK. Sonographic and Endoscopic Findings in Cocaine-Induced Ischemic Colitis. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2015;2015:680937. doi: 10.1155/2015/680937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsu CW, Lin CH, Wang JH, Wang HT, Ou WC, King TM. Acute rectocolitis following endoscopy in health check-up patients--glutaraldehyde colitis or ischemic colitis? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1193–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00384-009-0764-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shih HY, Wu DC, Huang WT, Chang YY, Yu FJ. Glutaraldehyde-induced colitis: case reports and literature review. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27:577–580. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2011.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stein BL, Lamoureux E, Miller M, Vasilevsky CA, Julien L, Gordon PH. Glutaraldehyde-induced colitis. Can J Surg. 2001;44:113–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.West AB, Kuan SF, Bennick M, Lagarde S. Glutaraldehyde colitis following endoscopy: clinical and pathological features and investigation of an outbreak. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1250–1255. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ahishali E, Uygur-Bayramiçli O, Dolapçioğlu C, Dabak R, Mengi A, Işik A, Ermiş E. Chemical colitis due to glutaraldehyde: case series and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2541–2545. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurdaş OO, Sezikli M, Cetinkaya ZA, Güzelbulut F, Yaşar B, Coşgun S, Değirmenci AS. Glutaraldehyde-induced colitis: three case reports. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:221–223. doi: 10.1007/s12664-009-0082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang DM, Urrunaga NH, De Groot H, von Rosenvinge EC, Xie G, Ghazi LJ. Pseudomembranous Colitis: Not Always Caused by Clostridium difficile. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:812704. doi: 10.1155/2014/812704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huynh TM, Le QD, Bui KLN, Bui MQH, Vo CMH, Quach DT. Ischemic Colitis Presented as Pseudomembranous Colitis: An Untypical Case from Vietnam. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2022;80:93–98. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2022.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]