Abstract

Background

Complete Eats Rx is a fruit and vegetable prescription program designed to incentivize fruit and vegetable consumption among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participants via $10 incentives distributed either weekly or per encounter to purchase fruits and vegetables at a mid-price supermarket chain in Washington State.

Objective

To better understand SNAP participants’ experience, and to determine perceived impacts and consequences of the program.

Design

Qualitative analysis of nine photovoice sessions. Participants chose the topics for discussion. Sessions were audiorecorded and transcribed. Thematic content analysis was performed to identify key emergent themes using Atlas.ti.

Setting

Spokane, Seattle, and Yakima, Washington.

Participants

Twenty-six individuals who received a fruit and vegetable prescription within the past 6 months, 23 of whom attended all three photovoice sessions offered at their site. Participants were recruited from three participating health care or public health organizations in Spokane, Seattle, and Yakima, Washington.

Analysis

Transcriptions were coded using inductive methods. Coded statements were organized into major themes. Coding structures and analysis were strengthened by iterative interactions between researchers.

Results

Participants reported Complete Eats Rx was an important resource for families and improved food security, diet quality, and the ability to purchase healthy foods, including a greater variety of fruits and vegetables. Primary barriers to food security and fruit and vegetable consumption included limited geographic accessibility and the high cost of fruits and vegetables, exacerbated by other financial constraints such as rising housing costs. Participants reported supermarket checkout difficulty because of embarrassment, stigmatization, and inability to redeem incentives. The most frequently mentioned barrier to perceived program acceptability was having only one supermarket chain as the acceptor of the incentive.

Conclusion

Partnering with supermarkets to accept fruit and vegetable incentives is a unique strategy to increase produce purchasing that can be adopted by other localities. Focus on geographic accessibility, appropriate price points, and positive shopping experiences via expansion to local grocers, improvements in staff interactions, and a transition to an electronic system may improve incentive redemption and usability.

Keywords: Qualitative research, Fruit and vegetable incentive, Food retail, Nutrition policy, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

DIETS RICH IN FRUITS AND VEGETABLES ARE ASSOciated with better overall health and lower chronic disease risk.1 However, only 12.2% of Americans meet the daily recommended intake of fruit, and 9.3% meet vegetable recommendations.2 Evidence suggests that low-income populations face additional barriers to fruit and vegetable consumption compared with their higher-income counterparts, including limited access to fruit and vegetables, prohibitively high costs of fruit and vegetables, and low quality of available fruit and vegetables.3,4 These factors have been associated with lower consumption of fruits and vegetables among populations with low socioeconomic status.3–5 Income-based disparities in access to and intake of fruits and vegetables also may contribute to disparities in diet-related chronic disease.6,7

Evidence suggests a positive association of fruit and vegetable incentive programs with food security, fruit and vegetable purchases, and perceived fruit and vegetable consumption among low-income individuals.8–14 Furthermore, fruit and vegetable incentives have been associated with improvements in hemoglobin A1c levels and body mass index,15,16 suggesting potential for long-term reductions in diet-related disease and health care costs.16 Additionally, participants in incentive programs have largely endorsed the programs.3,9

Although incentive programs are increasing in popularity in the United States, most of the literature has centered around incentives that can only be redeemed at farmers markets.1,8,9,12,14,16 There is a dearth of literature on incentive programs that can be redeemed at supermarkets or grocery stores. One exception is a recent study by Rummo et al,17 which analyzed transaction data from 17 supermarkets participating in a grocery store fruit and vegetable incentive program, and 15 control supermarkets from the same chain that were not participating in the program. Researchers found that Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participants’ spending on fresh produce was significantly higher at participating stores compared with control stores. Still, little is known about the specific impacts and challenges of incentive programs redeemable in supermarkets. Programs that allow fruit and vegetable incentives to be redeemed at participating supermarkets have the potential to add convenience and purchasing power for consumers in ways that differ from farmers markets through the possibility of extended hours of operation, convenient locations, and lower price points. It is therefore important to study the impact of supermarket fruit and vegetable incentive programs.

The Washington State Department of Health tested three different fruit and vegetable incentive strategies for SNAP participants funded by a US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentive grant. One of the strategies was Complete Eats Rx. Complete Eats Rx launched in 2016 and consisted of $10 incentives prescribed by health care providers at participating clinics or community sites to eligible patients. Frequency of incentive distribution varied by site at the time of this study because of the wide variety in settings. Seattle participants received one to two incentives per week for 6 months. Spokane and Yakima participants received incentives per encounter; number and frequency of encounters varied. At the time of this study, SNAP participation was the only eligibility criteria. Incentives were valid at a large, mid-price supermarket chain in Washington State for the purchase of fresh, canned, and frozen fruit and vegetables with no added salt, sugars, or fats. Evaluation shows that Complete Eats Rx is feasible for increasing fruit and vegetable purchases, and it has moderate reach and moderately high redemption rates.18 Evaluation results also found that 88.2% of survey respondents reported eating more fruits and vegetables than previously as a result of the prescription. Internal Department of Health program records found that between July 2016 and December 2019, 8,787 people redeemed Complete Eats Rx vouchers, and 62% of the vouchers distributed were redeemed.

The purpose of this study was to understand participant experiences with the Washington State Complete Eats Rx program to determine the perceived impacts and consequences of the program. We used photovoice techniques to elevate participants’ roles in shaping group discussions, leveraged imagery to elicit participant experience, and allowed researchers and program staff to better understand participants’ lived experiences.

METHODS

Photovoice

This study used photovoice to qualitatively assess participant experiences with the Washington State Complete Eats Rx program. Photovoice is a community-based qualitative data collection technique that uses participant-taken photos to drive conversation. Although photovoice allows for a facilitator to encourage conversation, discussions rely on participant collaboration and leadership in topics discussed, thus differentiating them from traditional focus groups.19

Study Recruitment and Enrollment

Participants self-selected into the study. They were recruited using flyers and sign-up sheets in the lobbies of three health care and public health organizations (one each in Spokane, Seattle, and Yakima, Washington) that implemented Complete Eats Rx. Yakima sessions were held in Spanish, and Seattle and Spokane sessions were held in English. At the time of the study, 48% of vouchers distributed in Seattle were redeemed, 60% of vouchers distributed in Yakima were redeemed, and 60% of vouchers distributed in Spokane were redeemed. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were older than 18 years, comfortable communicating in English or Spanish, had received an incentive within the past 6 months regardless of use, and intended to attend each of the three meetings.

Data Collection

Photovoice meetings were conducted May 6 through July 3, 2019. Each of the three organizations’ participants attended one 75-minute and two 125-minute meetings at their local site, for a total of three weekly meetings per individual and nine meetings total. Researchers chose to hold three meetings per site to encourage group relationships and provide enough opportunity to discuss their experiences while not requiring too much participant time, which would have potential to discourage participation. Participants received $50 in either grocery store gift cards or farmers market gift cards after each meeting (depending on their preference) as compensation for their time.

Researchers performed a literature review and studied photovoice methodology and best practices before conduction. Photovoice facilitators were oriented by two of the researchers. The orientation was approximately 1 hour in duration and included information on the Complete Eats Rx program, photovoice technique, and evaluation aims. In both Seattle and Spokane, all three meetings were facilitated by the same health care or public health organization employee, respectively. In Yakima, each meeting was facilitated by a different local community health worker, although all three community health workers attended all meetings. Facilitators were matched in terms of ethnicity and language for most of the participants at each site. A researcher was present at each meeting as a notetaker. Notes were used for reference but were not incorporated into analysis. Three of the researchers are Washington State Department of Health staff members, two of which are affiliated with the Complete Eats Rx program. Two of these researchers participated as notetakers and were identified as Department of Health employees; however, participants were assured nothing they said would affect their ability to participate in the program. These researchers did not contribute to data analysis or interpretation of the findings. Each meeting was audio recorded, with participant consent. The Washington State Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Photovoice Process

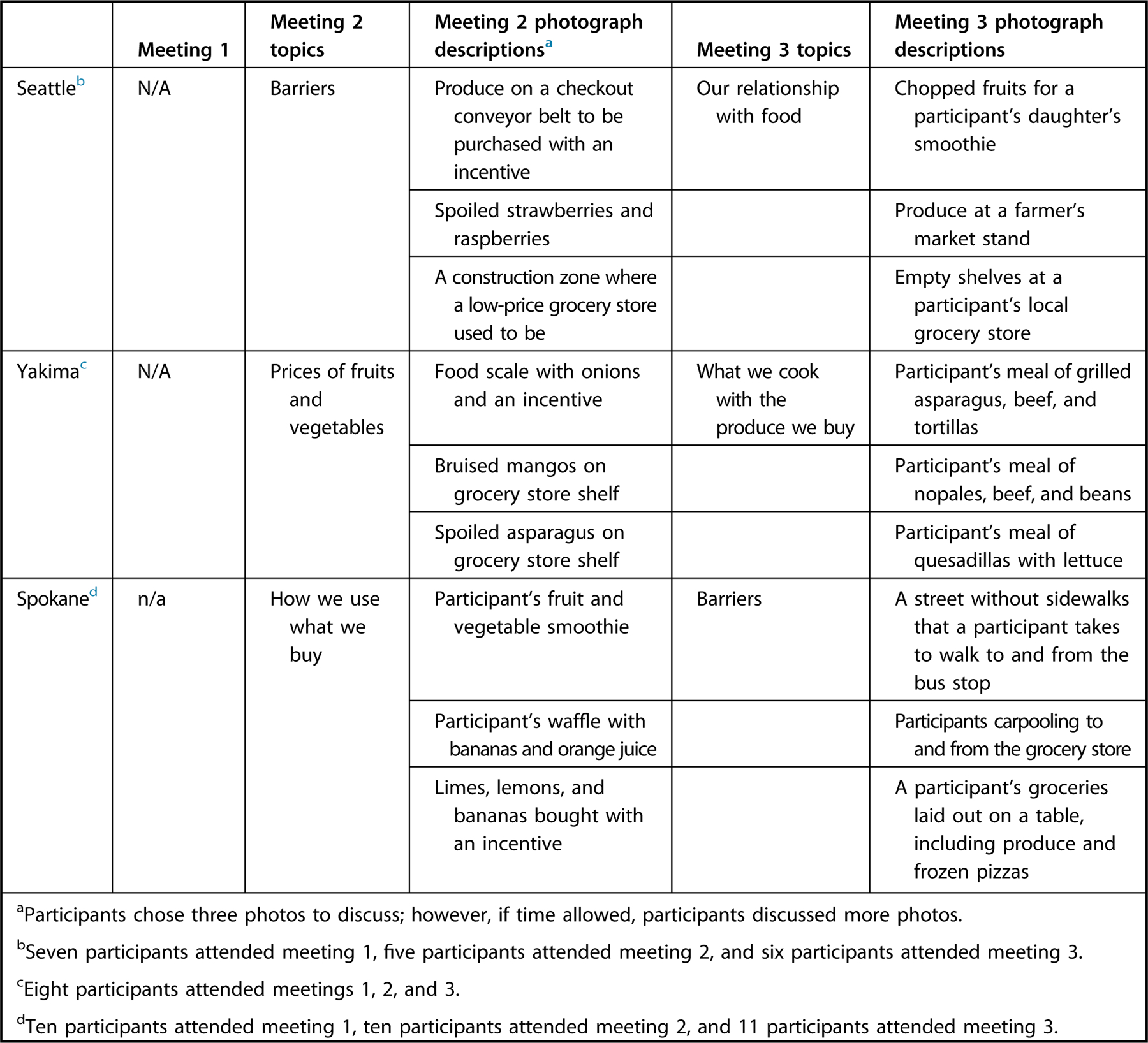

The first meeting at each site consisted of an orientation to photovoice and the purpose of the study. This led to impromptu initial discussion of participant experiences with the program. Cameras were distributed to participants who requested one, and participants practiced using them. Participants who chose not to use a camera supplied by the Department of Health used their personal phone camera. Facilitators then asked participants to suggest and vote on topics for the photos they would like to capture in the first week related to their experiences with the program, often prompted from the initial discussion of their experiences. Each cohort chose their topics separately. Topics chosen are shown in Figure 1. Participants were instructed to take photos of their lived experience as it related to the selected topic and were instructed to not capture faces to protect anonymity. There was no limit on how many photos they could capture. Cameras were brought back to the subsequent weekly meetings, and photos were digitally projected. Photos taken on personal phones were emailed to the researcher present at the meeting for digital projection. Once all photos were presented, facilitators instructed participants to vote for three photos for discussion. If time allowed, participants could discuss more photos once they finished discussing the three originally chosen. Descriptions of photos chosen are shown in Figure 1. The discussion was structured through the use of questions linked by the mnemonic SHOWED, or VENCeR for Spanish speakers.20 These questions are designed to guide discussion around photos toward abstract critical analysis and action steps to address the issue. For each photo, facilitators guided discussion through the use of the following questions: (1) what do you see in the photo? (2) What is really happening in the photo? (3) How does this relate to our lives? (4) Why does this situation, concern, or strength exist? and (5) What can we do to improve the situation or enhance these strengths? At the end of the second meeting, participants chose a new topic for the third session. During the third meeting, photos taken in week 2 were discussed in the same manner as the previous week.

Figure 1.

Topics, number of participants, and descriptions of photos discussed by cohort participating in photovoice meetings on Washington State Department of Health’s Complete Eats Rx program.

Data Analysis

All session recordings were transcribed. The Spanish language focus group recordings were directly transcribed into English by native Spanish speakers, using a transcription service.

Researchers qualitatively analyzed data by using inductive content analysis. One researcher with substantial qualitative training and experience supervised the coding process, providing instruction and feedback to the lead researcher, who had formal training in qualitative analysis. An initial reading of the transcripts was performed to identify emergent themes in the text. One researcher served as a coder, performing close readings of the text and developing and consolidating specific codes into an initial codebook. A Department of Health staff member who was not involved in other aspects of the study served as a double coder and reviewed one transcript from each cohort, coding 30% of total transcripts. Coders reviewed differences in coding, iteratively discussed rationale, and created the final codebook. The original coder then coded the remaining transcripts, using these final codes. Codes were then grouped into five major themes. Atlas.ti 8.421 was used to code and analyze all data.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

A total of 26 individuals participated in the study, and 23 attended all three sessions. Most of the participants were female (n = 17) and mothers (n = 15). Many participants were older adults (n = 12). Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Krippendorff’s alpha with a value of α = .823. Five major themes emerged from analysis: (1) environmental factors influencing food security and food purchasing decisions; (2) programmatic factors influencing incentive use; (3) perception of the program; (4) program impact; and (5) participants’ suggestions to overcome food security and program barriers. The Food and Agricultural Organization’s definition of food security was used for this study. This definition states that food security is when an individual, at all times, has physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food.22 Major themes are discussed in the following sections.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS INFLUENCING FOOD SECURITY AND PURCHASING

Financial Constraints

Participants faced multiple financial constraints that took precedence over food budgets, reducing food security and fruit and vegetable consumption. Participants had to manage other expenses, including housing/rent, transportation, medical bills, and life events such as moving. Participants’ long work hours and low wages lowered financial accessibility to a quality diet and reduced their motivation and ability to spend time cooking healthy meals. Most participants were unable to purchase fruits and vegetables because of financial and other constraints. They understood healthy eating recommendations but found them impractical. “They want you to have more than one serving of fruit and vegetables every day….with our income, low-income people, you might as well forget about it and I’ll just say that right out.”

Participants named the rising cost of living as having a large effect on their ability to afford food. “The cost of living does not take into account the diet, you know? You know life is life and you can barely pay rent and if you can keep the lights on that month you’ve done good and it gets worse and worse every year so of course the diet goes on the back-burner.” Financial barriers related to wages and the high cost of living, followed by housing concerns related to gentrification, and poor access to quality grocers were the most frequently mentioned barriers to food security by participants in urban areas, whereas financial barriers related to medical issues and low to no income were frequently mentioned by older participants.

Community was also mentioned as a valuable safety net in guaranteeing participants’ ability to feed themselves and their families. Seattle participants noted that this community safety net is disappearing because of gentrification. “When you take away those great resources and infrastructure that allow us to come together…it breaks down those networks.” Finally, many participants live in apartments because of the high cost of housing. Apartment living limits the ability of participants to grow food. Home gardens were noted as a significant source of fruits and vegetables and a strategy that had been used for generations to supplement diets. According to participants, apartment living has taken away that supply and reduced diet quality and affordability.

Cost of Fruits and Vegetables

The high cost of produce was the most frequently mentioned barrier to food security by participants in rural areas and one of the most frequently mentioned barriers by older participants. Fruits and vegetables were perceived as the most expensive component of the diet and as a luxury. Those who benefitted from healthy living classes explained they would not have been able to transition from learning about the benefits of fruit and vegetable consumption to increasing purchase and consumption without the Complete Eats Rx program. One older participant explained, “People at our age splurge on fruits and vegetables. You used to have to splurge on meats but now it’s fruits and vegetables. Fresh or organic especially.” Along with the high cost, purchasing fruits and vegetables was seen as a gamble; participants feared their children may not like them, they may be low quality, or they may spoil quickly. Many were driven to highly processed food because of affordability and convenience (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

A photo taken by a participant in photovoice focus groups evaluating the Washington State Department of Health’s Complete Eats Rx program. The participant told us the photo was of their weekly groceries and “the cherries...cost more than the three pizzas.”

Location

Location and availability of food sources were named as barriers to food security. Issues with public transit stemming from spatial access to supermarkets was the most frequently mentioned barrier to food security by older adults. Participants reported limited access to supermarkets, leading to long, impractical trips on public transit. Lack of sidewalks, long walks with groceries, multiple bus transfers, and stigma from other patrons and bus drivers caused physical distress and made grocery shopping using public transit less feasible. “We’re having to carry the groceries on the bus so sometimes it takes me and my sister a good half an hour just to walk from [the bus stop] to our apartment.” Long bus rides led to infrequent grocery trips, reducing the practicality of purchasing perishable foods. Compared with stores in communities with higher socioeconomic status, participants perceived the stores most accessible to them as having less accommodating staff, and poorer selection, quantity, and quality of produce (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

A photo taken by a participant in photovoice focus groups evaluating the Washington State Department of Health’s Complete Eats Rx program portraying their environment. The photo on the left shows the lack of unobstructed and continuous pathways on the participant’s walk to and from the bus stop. This makes the trip difficult and dangerous. The photo on the right shows the empty shelves at a participant’s local participating grocer. “I went to the [high SES area] one and it looked like a little showroom,” explained the participant.

PROGRAMMATIC FACTORS INFLUENCING INCENTIVE USE

Supermarket Access, Cost, and Quality

The most frequently mentioned program concern was that there was only one participating supermarket chain that accepted the incentive, limiting options for redemption. The main reasons for this concern were difficulty accessing the supermarket, high-cost products, and poor-quality produce. Product prices were seen as outside of participants’ budgets, limiting the purchasing power of the incentive. Additionally, participants reported low-quality produce in the stores most accessible to them. They told stories of produce spoiling too quickly after purchasing or spoiling while still in the store. They reported that miscalibrated scales led to overcharging and reduced incentive purchasing power. Overcharging for items was especially difficult for participants, because they could not afford to go back to the supermarket and fix the issues.

No participants named the participating supermarket chain as their preferred grocery store. Transit cost and time spent to access the supermarket were considered when deciding whether to use the incentives. Many participants made separate trips to the participating supermarket to use the incentive and did the rest of their shopping elsewhere. This forced participants to spend extra money on transit and was impractical for those with limited time. Other participants did all of their shopping at the participating supermarket when they had an incentive. These participants reported spending more on items they could purchase for less at other stores. “The only reason I spent the money at [participating supermarket] yesterday was because I felt like I didn’t have a choice. You got there, you spent the bus money.”

Difficulty at Checkout, Lack of Knowledge, and Inconsistency Around Program Rules

Difficulty at checkout was the most frequently reported reason participants did not use their incentives. Difficulties stemmed from staff inability to redeem incentives, incorrect incentive redemption, and inconsistent rules around incentives such as what can be purchased and how many incentives could be redeemed at once, and long checkout times. “Because some [cashiers] will say ‘ok this is ok’ and another might say ‘no that’s not ok’ and that’s a big confusing aspect and that happened to me. I got so mad I left and didn’t buy anything that day. I was in that line for about 45 minutes. The lady made me go to a whole other checkout, the manager came. My kids were like, ‘can we go now?’ And I was like ‘no, we did everything right.’” Staff difficulties led to perceived embarrassment for participants and stigmatization by cashiers and other customers.

Participants reported confusion around the program rules, most commonly regarding what types of products could be purchased with incentives. Although most of the confusion stemmed from misreported rules by supermarket staff, participating health care and public health organizations’ lack of knowledge around changes in program regulations also caused difficulties.

Program Perception

Although some program difficulties such as those related to checkout reduced redemption of the incentive, most difficulties did not prevent incentive use. Participants were grateful for the program and hoped for its continuation. “These coupons saved my family. I learned how to cook things. Sometimes that’s all we had.” Participants either viewed the incentive as an increase in their SNAP benefits, thus contributing to their overall food security, or as a tool to motivate behavior change around increasing produce consumption. The following two quotes exemplify these two perceptions of the program: “That little bit makes a big difference. Like that’s ten dollars I can put down on bread,” and, “This program is helping me stay on track so we can buy things that are less packaged. Things we normally just can’t afford.” These views varied by cohort. The Seattle cohort generally viewed the incentive as contributing to their general food security, and the Spokane and Yakima cohorts generally viewed the incentive as a tool to increase fruit and vegetable consumption (Fig 4).

Figure 4.

A photo taken by a participant in photovoice focus groups evaluating the Washington State Department of Health’s Complete Eats Rx program portraying the quality of papayas at their local participating grocer. Other participants agreed that they frequently found produce spoiling on the shelves.

PROGRAM IMPACT

Diet Quality, Variety, and Affordability

Complete Eats Rx was associated with perceived increases in participants’ self-reported grocery budget, perceived produce consumption, and perceived food security. As explained by one participant, “I’m not spending as much on food but getting a lot of produce—fruits and vegetables. It gives us a chance to get the fresh stuff.” Incentives helped them purchase produce they otherwise would not be able to afford, such as berries, dark leafy greens, and organic produce. Although the incentive allowed some participants to eat a diet they already desired but couldn’t afford, others credited a new positive outlook on fruits and vegetables to the program. Incentives were used to alter typical meals and cultural favorites to feature more fruits and vegetables. Incentives were also used for healthy after-school snacks, smoothies, and canning homemade jams.

Family and Community

Most of the participants were parents. These participants were aware of the effects their children’s diet would have on their futures. “They’re learning, they’re going to be the future, so we must teach them about this, because I didn’t know so much about vegetables.” Participants perceived Complete Eats Rx as having a large impact on their childrens’ behaviors around food. Parents used the incentives for healthy after-school snacks and meals and for bonding activities. Participants reported incentives increasing their children’s exposure to fruits and vegetables and supporting fruit and vegetable normalization in the home. “My goddaughter that I have now, she grew up not having any vegetables or anything, she’s used to microwaving all her stuff. So it was good to have them try different things out.” Incentives encouraged families to cook with their children and to take them produce shopping, as well as engage in learning activities such as reading labels, weighing, measuring, and learning the names of fruits and vegetables. The program also allowed participants to hold large family and community meals. Participants expressed the importance of the program in their ability to feed friends and family: “Not only did we feed the nine people in our house, but our neighbor has bone marrow cancer he just told us about—and we were able to feed him and his family and another neighbor.” Medical conditions, dietary restrictions, and preferences can make it difficult to afford holding large dinners, and the incentives alleviated some of the financial barriers associated. “With health conditions or special diets...you end up making three different meals and it costs more,” explained one participant.

Participant Suggestions

Throughout the meetings, participants suggested solutions to address food insecurity, as well as ways to improve the Complete Eats Rx program. The most commonly mentioned suggestions to alleviate food insecurity included bringing paratransit to low-income housing, allowing incentive and electronic benefit transfer (EBT) use for online grocery shopping, freezing produce and using proper storage techniques to reduce spoilage, encouraging supermarkets to sample produce to ensure quality, and building community to help families feed each other during difficult times. Common solutions to programmatic barriers included expanding the program to more stores, making alterations to the incentive such as dispensing incentives at various values and extending the expiration date, including recipes and snack/meal ideas with incentives, and including food storage education with the incentive.

DISCUSSION

Participants reported Complete Eats Rx, a fruit and vegetable prescription program, as an important intervention to increase both food security and fruit and vegetable consumption in their households. Primary reported barriers to food security and produce consumption among participants were the high cost of fruits and vegetables exacerbated by other financial constraints, and low geographic accessibility. Although nutrition education was seen as beneficial, education was not perceived as beneficial without addressing major access constraints. The most frequently mentioned barrier to program use was difficulty at checkout, and the most frequently mentioned barrier to program acceptability was the supermarket chain as the sole acceptor of the incentive.

Before this study, most of the literature on the benefits and barriers to fruit and vegetable incentive use has focused on farmers market incentive programs. Although farmers market incentives benefit local vendors and are associated with positive outcomes such as higher fruit and vegetable purchase and consumption in low-income individuals,1,9 farmers markets are often perceived as a venue for high-income individuals and can leave low-income shoppers feeling stigmatized when using supplemental programs.23 However, possibly perceptions of farmers market pricing are dependent on features of particular regions or farmers markets, as findings are mixed in the literature.23 The results of this study expand on current literature by examining a supermarket-based incentive program, a unique strategy to increase produce consumption that can be modeled by other localities.

Participants reported that the fruit and vegetable prescription incentive program increased both their produce consumption and food security. This finding is consistent with previous studies.1,13,14 Savoie-Roskos et al24 examined fruit and vegetable intake and food security in a dollar-per-dollar match for up to $10 per week in farmers market incentives with a pretest‒posttest design. They found improvement in intake of certain vegetables and in food insecurity-related behaviors such as skipping meals and eating less than desired postintervention.1 Several other studies have found similar increases in purchase and consumption with farmers market incentive use.1,8,9 Although few studies have examined whether these same benefits translate to supermarket incentive programs, Rummo et al17 analyzed transactions from 32 individual grocery stores in a large chain, 17 of which participated in a fruit and vegetable dollar-matching program for SNAP participants in Michigan.18 They found that SNAP participant spending on fruits and vegetables was significantly higher at participating stores than at control stores.

Primary reported barriers to food security and produce consumption among participants were the high cost of produce, exacerbated by other financial constraints. This is consistent with previous studies.5,13,24 A qualitative study using a customer intercept survey examined customer characteristics and barriers to healthy eating among customers at a mobile farmers market.24 Among all customer respondents, the most common barrier to healthy eating was cost. Long-term follow-up of a large intervention with nine Women, Infants, and Children supplemental nutrition program (WIC) clients involving $40/week fruit and vegetable incentives, nutrition education, and produce shopping guidance, found that 3 years later participants reported feeling limited in their ability to eat healthily after the program’s subsidization ended, largely because of the cost of produce.

Geographic accessibility was another major reported barrier to food access and produce consumption. Although produce incentive programs primarily address financial access, simultaneously addressing both financial and geographic access may increase usability, further increasing fruit and vegetable consumption. Analysis of consumer survey data of a farmers market incentive program found evidence that consumers from areas with low food access and low income were the most likely to perceive that their consumption was higher with the use of fruit and vegetable incentives.13 Although farmers market incentives aim to address both of these barriers and are associated with improved food access in low-income individuals, lack of farmer’s markets close to home is a common barrier, because they often operate during limited hours and in high-income neighborhoods.13,23–26 In a systematic review of farmers market incentive programs, Freedman et al23 found that among studies involving low-income populations, key barriers to use included lack of access to transportation and lack of racial diversity in the market space.24 Supermarket incentive programs have the opportunity to address geographic access and produce acceptability barriers by expanding incentive programs to local grocers that participants already frequent. Previous studies have found that small stores in high-need communities can increase produce availability, improve diet quality, and impact the eating culture of a neighborhood.27,28 Improving financial access to these small stores through incentives has the potential to further these benefits. In theory, fruit and vegetable incentive use in small local stores may increase fruit and vegetable purchases, motivating retailers to provide a larger selection of produce.

The most frequently mentioned barrier to program use was difficulty at checkout, including technical issues and stigma. Difficulties at checkout and stigma are common concerns in supplemental nutrition and incentive programs.29–31 Although most literature examining the shopping experience of incentive program recipients is found in the gray literature, a qualitative study evaluating WIC customer experiences was conducted by using a series of focus groups with New Mexico WIC participants to better understand their shopping experiences.31 Researchers found employee‒customer interactions to be a major theme in the WIC customer experiences, with participants reporting employee impatience and unfriendliness. Participants also reported experiences of poor store-level WIC program management. Examples of this included poor cashier training, which can result in transaction errors and decreased redemption of benefits. Our study found similar participant experiences with the Complete Eats Rx program. Difficulties at checkout stemmed from either a perceived lack of employee training or technical difficulties. These difficulties can lead to perceived bias against incentive users by staff and customers. Focusing on improving the checkout experience via improvements in staff interactions or through technical means such as a transition to an electronic system may have beneficial effects on redemption. Although, to our knowledge, no published data exist evaluating efforts to improve user‒staff relations in incentive programs, after similar customer experience findings in the New Mexico WIC program, Payne et al30 suggest setting normative retailer benchmarks of what is expected for WIC customer experiences. A similar strategy could be recommended for organizations implementing supermarket-based incentive programs. Normative retailer benchmarks create motivation for participating stores to address program barriers such as difficulty at checkout and poor-quality produce. An example of this is to reward stores that train staff or use a nutrition expert to explain how to choose and handle quality produce. This would address the frequently mentioned barrier of low-quality produce while providing hands-on nutrition education.

As incentive programs continue to grow in size and duration, organizations may want to switch to an electronic system as soon as is feasible. The EBT systems have been shown to reduce the stigma associated supplemental programs, because EBT cards are used similarly to a credit or debit card, allowing for easier and more discreet transactions.32 If fruit and vegetable incentive programs embrace a similar transition to an electronic system, similar results may be possible. This transition would be resource-intensive but is feasible, as shown by the electronic systems used in Flint Michigan’s Double Up Food Bucks grocery store incentive program and in the USDA Healthy Incentives Pilot that took place in western Massachusetts.33

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include utilization of a community-led discussion technique rather than discussion based on expected outcomes and concerns. Encouraging participant leadership has been shown to broaden the focus of the research question.34 It has also been shown to empower communities and enhance understanding of community needs.19,34 Use of the photovoice methodology provided more detailed insight into the unique experiences and challenges among participants of a fruit and vegetable incentive program. Additionally, three distinct regions of varying populations were included, including a Spanish-speaking cohort. Finally, recordings were transcribed and underwent rigorous qualitative analysis.

This study also had limitations. Participants self-selected into the study, introducing bias toward those who had opinions on the program and were available during the hours of the meetings. Neither demographic characteristics nor information on frequency of incentive use were collected. Researchers attended meetings, which also may have introduced bias. However, researchers did not contribute to conversation other than to clarify program-related information. Topics discussed at sites were not uniform because of the participatory nature of the photovoice methodology. This may have led to uncaptured experiences relevant to the populations studied. Additionally, participants attended two meetings for the purpose of photo discussion. Possibly the discussion during the first meeting could have influenced what participants decided to take photos of for the second discussion. Three of the researchers are Washington State Department of Health staff members, two of whom are affiliated with the Complete Eats Rx program. These researchers did not contribute to data analysis or interpretation of the findings. Because of the qualitative nature of this study, causality between the program and the self-reported benefits of the program cannot be determined. Furthermore, findings from this evaluation may not be generalizable. Given regional variability and variability among independent incentive programs, some of these findings may not be applicable to specific regions or populations.

CONCLUSION

Incentive programs have been shown to increase fruit and vegetable purchasing in vulnerable populations; however, further research is needed on the participant experience, particularly in supermarket settings. We found the Complete Eats Rx program was associated with increased perceived food security and produce consumption in participants and their families. Although participants reported perceived program benefits, barriers to incentive use remained. As incentive programs continue to increase in prevalence and size, focus on geographic accessibility, appropriate price points, positive shopping experiences via expansion to local grocers, improvements in staff interactions, and a transition to an electronic system may improve the participants’ experiences and incentive redemption and usability.

RESEARCH SNAPSHOT.

Research Question:

What is the user experience of a USDA-funded fruit and vegetable prescription program in Washington State? What are the impacts and consequences of the program?

Key Findings:

In a qualitative study that included 26 individuals participating in a fruit and vegetable prescription incentive program, redeemable at a large national supermarket chain, participants reported perceived improvements in food security, diet quality, healthy food affordability, and fruit and vegetable variety. The most frequently mentioned barrier to program use was difficulty at supermarket checkout. The most frequently mentioned barrier to program acceptability was that the participating supermarket was the sole acceptor of the incentive, limiting redemption options.

PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS.

What Is the Current Knowledge on This Topic?

Diets rich in fruits and vegetables are associated with better overall health and lower chronic disease risk.1 However, evidence suggests that low-income populations face barriers to fruit and vegetable consumption, including limited access to fruit and vegetables, prohibitively high costs of fruit and vegetables, and low quality of available fruit and vegetables, reducing consumption.3–5

Fruit and vegetable incentive programs have been shown to improve food access, self-reported mental wellbeing, and food insecurity, and they show promise as a strategy for improving dietary quality among low-income individuals.13,14 Incentives are also associated with higher fruit and vegetable purchase and consumption in low-income individuals.1,8–12 Even with these promising findings, barriers to redemption and acceptability of incentives exist. Common challenges include stigma experienced by the individual using an incentive, limited geographic access and hours of operation of venues accepting the incentives, technical difficulties at checkout, and negative employee‒customer interactions. 23,24,25,28–30

How Does This Research Add to Knowledge on This Topic?

The purpose of this study was to understand participant experiences with the Washington State Complete Eats Rx fruit and vegetable prescription program to better understand the perceived impacts and consequences of the program. We used photovoice techniques to elevate participants’ roles in shaping group discussions, leverage imagery to elicit participant experience, and allow researchers and program staff to better understand participants’ lived experiences.

How Might This Knowledge Impact Current Dietetics Practice?

Dietitians are often key members of health care and public health teams that distribute fruit and vegetable incentive programs. The findings from this study provide insight into patient-perceived benefits and barriers of one such program in Washington State.

Participants reported that Complete Eats Rx was an important resource for families and improved food security, diet quality, healthy food affordability, and fruit and vegetable variety. The reported barriers to program use and acceptance present opportunities to improve grocery store incentive programs as they continue to grow in size and duration.

The most frequently mentioned barrier to program acceptability was the supermarket chain as the sole acceptor of the incentive, in part because of limited geographic access and reports of poor-quality produce. Supermarket incentive programs have the opportunity to address both geographic access and produce acceptability barriers by expanding incentive programs to locally owned grocers that participants already frequent. The most frequently mentioned barrier to program use was difficulty at checkout, stemming from either a perceived lack of employee training or technical difficulties, which can lead to perceived bias against incentive users. Improving the checkout experience via improvements in staff interactions, such as setting normative retailer benchmarks, and reducing technical difficulties through electronic systems such as electronic benefit transfer (EBT), may have beneficial effects on redemption.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

Complete Eats Rx was supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture (award no. 2015-70018-23357). Support for the project was also made possible by the Bloomberg American Health Initiative. Partial support for this research came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, P2C HD042828, to the Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology at the University of Washington. Permission has been received for this acknowledgement.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Contributor Information

Sophia Riemer, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Lina Pinero Walkinshaw, University of Washington Center for Public Health Nutrition, Seattle, WA.

Alyssa Auvinen, Washington State Department of Health, Olympia, WA.

Jessica Marcinkevage, Washington State Department of Health, Olympia, WA.

Mary Daniel, Washington State Department of Health, Olympia, WA.

Jessica C. Jones-Smith, Department of Health Services, University of Washington School of Public Health, Seattle, WA.

References

- 1.Savoie-Roskos M, Durward C, Jeweks M, LeBlanc H. Reducing food insecurity and improving fruit and vegetable intake among farmers’ market incentive program participants. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2016;48(1):70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee-Kwan SH, Moore LV, Blanck HM, Harris DM, Galuska D. Disparities in state-specific adult fruit and vegetable consumption—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(45): 1241–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AbuSabha R, Namjoshi D, Klein A. Increasing access and affordability of produce improves perceived consumption of vegetables in low-income seniors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(10):1549–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bihan H, Castetbon K, Mejean C, et al. Sociodemographic factors and attitudes toward food affordability and health are associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in a low-income French population. J Nutr. 2010;140(4):823–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans A, Banks K, Jennings R, et al. Increasing access to healthful foods: A qualitative study with residents of low-income communities. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12(Suppl 1):S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen M, Krølner R, Klepp K-I, et al. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Part I: Quantitative studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: What the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S186–S196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson JV, Bybee DI, Brown RM, et al. 5 A day fruit and vegetable intervention improves consumption in a low income population. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(2):195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forbes JM, Forbes CR, Lehman E, George DR. “Prevention produce”: Integrating medical student mentorship into a fruit and vegetable prescription program for at-risk patients. Permanente J. 2019;23:18–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swartz H Produce Rx programs for diet-based chronic disease prevention. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(10):E960–E973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polacsek M, Moran A, Thorndike AN, et al. A supermarket double dollar incentive program increases purchases of fresh fruits and vegetables among low-income families with children: The Healthy Double Study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50(3):217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, Stites SD, et al. Impact of a rewards-based incentive program on promoting fruit and vegetable purchases. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):166–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dimitri C, Oberholtzer L, Nischan M. Reducing the geographic and financial barriers to food access: Perceived benefits of farmers’ markets and monetary incentives. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2013;8(4): 429–444. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridberg RA, Bell JF, Merritt KE, Harris DM, Young HM, Tancredi DJ. A pediatric fruit and vegetable prescription program increases food security in low-income households. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2019;51(2): 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavanagh M, Jurkowski J, Bozlak C, Hastings J, Klein A. Veggie Rx: An outcome evaluation of a healthy food incentive programme. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(14):2636–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryce R, Guajardo C, Ilarraza D, et al. Participation in a farmers’ market fruit and vegetable prescription program at a federally qualified health center improves hemoglobin A1C in low income uncontrolled diabetics. Prev Med Rep. 2017;7:176–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rummo PE, Noriega D, Parret A, Harding M, Hesterman O, Elbel BE. Evaluating a USDA program that gives SNAP participants financial incentives to buy fresh produce in supermarkets. Health Affairs. 2019;38(11):1816–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcinkevage J, Auvinen A, Nambuthiri S. Washington state’s fruit and vegetable prescription program: improving affordability of healthy foods for low-income patients. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16: 180617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nykiforuk CIJ, Vallianatos H, Nieuwendyk LM. Photovoice as a method for revealing community perceptions of the built and social environment. Int J Qual Methods. 2011;10(2):103–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hergenrather KC, Rhodes SD, Cowan CA, Bardhoshi G, Pula S. Photovoice as community-based participatory research: A qualitative review. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(6):686–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atlas.ti. Version 8.4.18.0. Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food Security; 2006.

- 23.Freedman DA, Vaudrin N, Schneider C, et al. Systematic review of factors influencing farmers’ market use overall and among low-income populations. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(7):1136–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savoie Roskos MR, Wengreen H, Gast J, LeBlanc H, Durward C. Understanding the experiences of low-income individuals receiving farmers’ market incentives in the United States: A qualitative study. Health Promotion Practice. 2017;18(6):869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ylitalo KR, During C, Thomas K, Ezell K, Lillard P, Scott J. The veggie van: Customer characteristics, fruit and vegetable consumption, and barriers to healthy eating among shoppers at a mobile Farmers Market in the United States. Appetite. 2019;133:279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Racine EF, Vaughn AS, Laditka SB. Farmers’ market use among African-American women participating in the special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(3):441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardiner B, Blake M, Harris R, et al. Can small stores have a big impact? A qualitative evaluation of a store fruit and vegetable initiative: Evaluation of store fruit and vegetable initiative. Health Promot J Austr. 2013;24(3):192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodor JN, Ulmer VM, Futrell Dunaway L, Farley TA, Rose D. The rationale behind small food store interventions in low-income urban neighborhoods: Insights from New Orleans. J Nutr. 2010;140(6): 1185–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haynes-Maslow L, Auvergne L, Mark B, Ammerman A, Weiner BJ. Low-income individuals’ perceptions about fruit and vegetable access programs: A qualitative study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47(4): 317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payne CR, Niculescu M, Guthrie JF, Mancino L. Can a better understanding of WIC customer experiences increase benefit redemption and help control program food costs? J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2018;13(2):143–153. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertmann FMW, Barroso C, Ohri-Vachaspati P, Hampl JS, Sell K, Wharton CM. Women, infants, and children cash value voucher (CVV) use in Arizona: A qualitative exploration of barriers and strategies related to fruit and vegetable purchases. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(3):S53–S58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanks AS, Gunther C, Lillard D, Scharff RL. From paper to plastic: Understanding the impact of eWIC on WIC recipient behavior. Food Policy. 2019;83:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evaluation of the Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP) Final Report—Summary. United States Department of Agriculture; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catalani C, Minkler M. Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Educ Behav. 2010;37(3):424–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]