Abstract

Introduction:

Vaccination continues to be the most effective method for controlling COVID-19 infectious diseases. Nonetheless, SARS-CoV-2 variants continue to evolve and emerge, resulting in significant public concerns worldwide, even after more than 2 years since the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to better understand how different COVID-19 vaccine platforms work, why SARS-CoV-2 variants continue to emerge, and what options for improving COVID-19 vaccines can be considered to fight against SARS-CoV-2 variants and future pandemics.

Area covered:

Here, we reviewed the innate immune sensors in the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 virus, innate and adaptive immunity including neutralizing antibodies by different COVID-19 vaccines. Efficacy comparison of the several COVID-19 vaccine platforms approved for use in humans, concerns about SARS-CoV-2 variants and breakthrough infections, and the options for developing future COIVD-19 vaccines were also covered.

Expert opinion:

Owing to the continuous emergence of novel pathogens and the reemergence of variants, safer and more effective new vaccines are needed. This review also aims to provide the knowledge basis for the development of next-generation COVID-19 and pan-coronavirus vaccines to provide cross-protection against new SARS-CoV-2 variants and future coronavirus pandemics.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2: ACE-2, TMPRSS-2, nucleic-acid-based vaccine, universal vaccine

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a positive sense, single-stranded (ss) RNA virus belonging to the Coronaviridae family that comprises four genera (alpha, beta, gamma, and deltacoronavirus). SARS-CoV-2 causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The ~30 kb capped and methylated RNA genome encodes four major structural proteins (Spike, E, M, N) and two overlapping ORFs, ORF1a, and ORF1b. A – 1 frameshift-induced ORF1b serves as a template for the synthesis of genomic RNA and subgenomic RNAs [1]. The 6–7 nucleotide (nt) core sequence, which is called the transcription-regulating sequence (TRS), has a common leader with a 5′-cap structure fused to different segments with a 3′ poly(A) tail of the viral genome [2,3]. The different subgenomic RNAs encode four conserved structural proteins (spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N)) and several accessory proteins.

The S protein of SARS-CoV-2 interacts with the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor for entry into host cells. ACE2 is highly expressed in capillary rich organs, such as the nasal upper respiratory tract, lung, heart, pancreas, kidney, gut, and brain [4]. To facilitate the entry of the virus, proteolytic activation of the S protein is induced by the cellular serine protease, TMPRSS2 [5]. In addition to S1 and S2 cleavage by TMPRSS2, the endosomal cysteine protease, cathepsin, induces endocytic-based fusion of host cell and viral membrane [6]. SARS2-S-driven fusion strongly depends on the expression of ACE2 rather than that of TMPRSS2, while SARS1-S-driven fusion is strongly dependent on TMPRSS2 expression and less dependent on ACE2 expression [7].

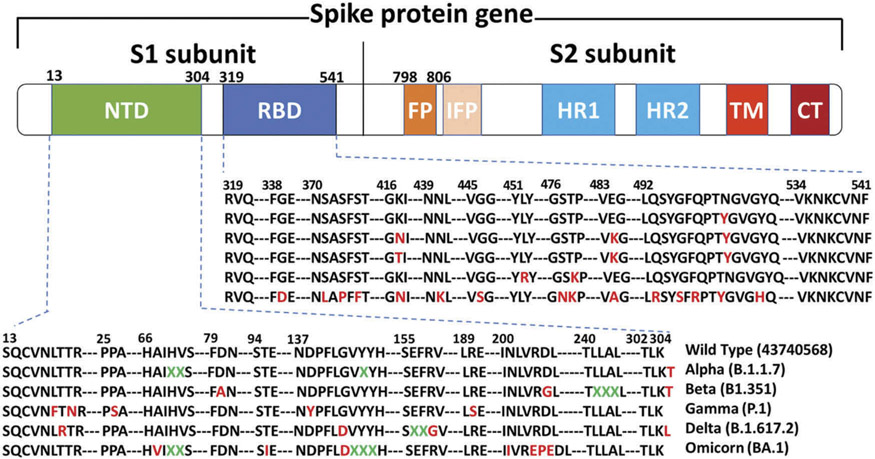

Multiple newly emerging variants of SARS-Cov-2 have rapidly spread worldwide, resulting in a global death toll of over 5 million. These SARS-Cov-2 variants include Beta, Delta, Alpha, Iota, Kappa, A.23.1, and Omicron, which have circulated within 2 years since the first confirmation of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. The Omicron variant is 4 times more contagious and 5.4 times more re-infectious than the Delta variant. At the receptor binding domain (RBD) of viral spike proteins, the Omicron variant has 15 amino acid mutations compared to wild-type SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1). Although RBD plays a critical role in recognizing ACE2 for viral attachment, the RBD is highly variable [8]. The S protein has evolved a finely tuned pre-fusion structure that switches between a standing position for receptor binding and a laying position for immune evasion [9-11]. The conformational masking of RBD potentially contributes to immune evasion, which might lead to insufficient immune responses and extensive spreading of the virus [12].

Figure 1.

Domain arrangement of the SARS-CoV-2 S glycoprotein. S1 comprises a signal sequence, NTD, and RBD. S2 comprises FP, HR1, HR2, the TM domain, and cytoplasmic C-terminus. NTD, N-terminal domain; RBD, receptor-binding domain; FP, fusion peptide; IFP, internal fusion peptide; HR1, heptad repeat 1; HR2, heptad repeat 2; TM, transmembrane domain. The spike protein sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 variants were aligned using MAGAX webserver.

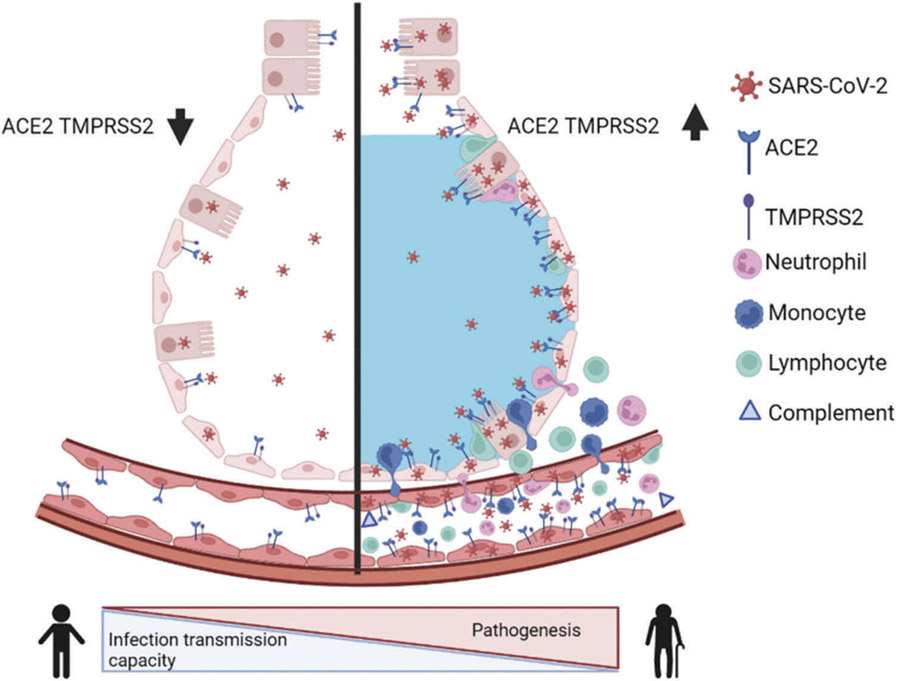

Therefore, continuous monitoring of the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations and understanding their potential roles in viral escape from existing neutralizing antibodies must be performed. Based on the results of a systematic meta-analysis performed before the emergence of the omicron variant, the pooled percentage of asymptomatic infections was 40.50% among the confirmed COVID-19 cases. In fact, asymptomatic patients were the potential source of COVID-19 transmission (Figure 2)[13]. The mutation-induced transmission of divergent variants provides unique opportunities for a natural selection of strains based on greater stability and immune escape [14,15]. Following the emergence of the omicron variant in December 2021, the rate of asymptomatic carriage became markedly higher than that seen for the earlier variants, which could explain that omicron has rapidly spread across the globe.

Figure 2.

The differences in airway tissue expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 between healthy and compromised elderly population. SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to an imbalance in vascular homeostasis by hijacking ACE2 in the elderly population and patients with comorbid diseases. Compared to ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression levels in the elderly population, healthy people with low expression of this receptor and protease have a higher infection transmission capacity without the severe pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. After SARS-CoV-2 infection, more inflammatory immune cells such as neutrophils, monocytes migrate to the alveoli and enhance lung inflammation and pathogenesis, increasing vascular permeability, ultimately leading to edema. This figure was created using the BioRender web-based software.

2. Molecular and cellular interactions at the virus–host interface

The RBD on the spike S1 subunit of SARS-CoV-2 hijacks the human cell membrane receptor ACE2 to invade host cells following proteolytic activation of transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2). Human ACE2 acts as a key modulator of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) by catalyzing the conversion of Ang II to Ang I. The ratio of Ang I to Ang II is critical in the regulation of vascular homeostasis. Hijacking of ACE II by the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 results in the accumulation of Ang II and pathological damage in the lung [16]. Excessive concentrations of Ang II, the autocrine vasoconstrictor of endothelial cells, cause endothelial cell death and vascular degeneration by destroying the connection between endothelial cells and pericytes [17,18]. However, the blockade and decrease in the activity of ACE2 fail to inactivate the ligands, bradykinin for the bradykinin-2 receptor (B2R) and desarg9-bradykinin for the B1R, causing increased vascular permeability. Increased pulmonary vascular permeability causes pulmonary edema. SARS-CoV-2 can cause acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) via the bradykinin pathway in the lung [19]. SARS-CoV-2 causes more aggressive and serious consequences in patients with comorbid diseases, such as hypertension, asthma, diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, than in those without comorbidities (i.e. the healthy population) [20]. Compared with individuals aged 54 years or younger, the mortality rate of COVID-19 is 8.1 times higher among those 55–64 years, and is 62 times higher among those ages 65 or older [21].

3. Recognition by pathogen-recognition receptors (PRRs) in host cells

RLRs.

Retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG)-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) are the two most prominent cytoplasmic sensors for distinguishing the SARS-CoV-2 genome from the host genome, and belong to the RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) family of PRR. RIG-I and MDA5 are expressed in all cell types, including endothelial cells [22]. The caspase activating and recruiting domains (CARD)-containing common adapter molecule mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS) interacts with both RIG-I and MDA5, which stimulates the signaling pathways resulting in IRF3/7-dependent IFN-α/β response and leads to NF-κB-dependent inflammatory gene transcription [23]. The MDA5-MAVS-IRF3 signaling axis is necessary for the induction of type I and III IFNs in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection [24]. However, the role of RIG-I in SARS-CoV-2 infection is inconsistent. Yin et al. [25] revealed that RIG-I is dispensable for the control of SARS-CoV-2 replication, while other studies suggest a role of RIG-1 in exhibiting antiviral effects on SARS-CoV-2 [26,27]. Mechanistically, RNA helicase RIG-I detects the 3’ untranslated region of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome and prevents viral RNA replication independently of IFNs [27]. Although the SARS-CoV-2 genome has multiple N-6-methyladenosine (m6A) residues within the N gene [28], other RNA pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) motifs, such as poly-U sequences or short hairpin structures, contribute to RIG-I binding [29].

TLRs.

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), a type I integral transmembrane glycoprotein family, play a crucial role in the initiation of innate immune response. The receptor domains of TLR1, 2, 4–6 are located on the cell surface, while those of TLR3, 7, 8, and 9 are located in intracellular vesicles (e.g. endosomes) with the cytoplasmic tail domain of the membrane. TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 contribute to the recognition of viral nucleic acids, while TLR2 and TLR4 detect viral glycoproteins. Upon viral PAMP recognition, TLRs dimerize and recruit the adaptor molecules, myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), or TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF), which triggers a signaling cascade that activates MAP kinases and NF-κB to induce the transcription of proinflammatory genes. TLR signaling also leads to the nuclear translocation of transcription factors, such as NF-κB, IRF-3, and IRF-7, which eventually stimulate type I IFN and IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) expression. SARS-CoV-2 E [30] or S [31] protein induces TLR2 signaling and pro-inflammatory cytokine (IL-6, IL-1 β) production. TLR7 and TLR8 are activated by guanosine and uridine rich (GU-rich) sequences [32]. Synthetically generated SARS-CoV-2-specific GU-rich RNAs act as TLR8 ligands in myeloid cells [33,34]. However, the frequency of poly-U or GU-rich sequences in microbial RNA does not markedly differ from that in vertebrate RNA. Further, how the preference for these motifs may help distinguish self from non-self RNA remains unclear [32]. Although the biological rationale for these sequence preferences is still unknown [32], TLR7 and 8 can accommodate ssRNA oligonucleotides produced during SARS-CoV-2 infection.

NLRs.

The nucleotide-binding and oligomerization domain (NOD-), leucine-rich repeat (LRR-) like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) interacts with apoptosis-associated Speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) and caspase-1 to form multi-protein complexes called inflammasomes [35]. After assembly of the inflammasome complex, active caspase-1 regulates the proteolytic processing of TLR signaling-induced proIL-1β and proIL-18 into mature and secreted forms. Eventually, the activation of the inflammasome can lead to pyroptosis, a pro-inflammatory form of programmed cell death. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is induced by multiple SARS-CoV-2 PAMPs, including GU-rich RNAs, E, and ORF3a proteins [30,36,37]. The SARS-CoV-2 E protein ion channel activity promotes lung inflammation, fluid accumulation, and bronchoalveolar epithelial damage [38]. Furthermore, the ORF3a viroporin ion channel protein induces potassium (K+) efflux, leading to NLRP3 inflammasome activation via mechanisms such as the formation of pores with ion-redistribution and lysosomal disruption [37,39].

4. Development outcomes of current SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

DNA vaccines.

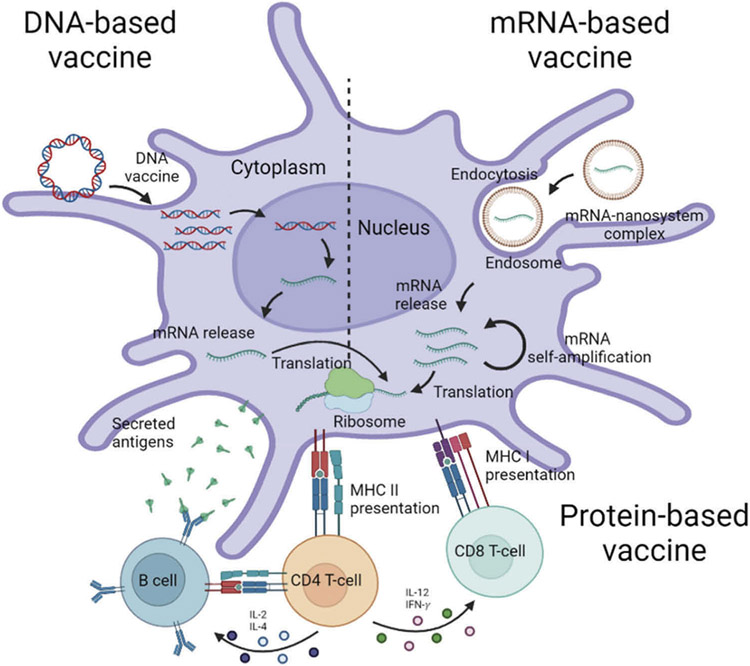

DNA vaccines are delivered into skin compartment using a gene gun, jet injector, microneedles, or via intramuscular injection. Although there is concern that the DNA vaccine can change the genetic composition of the host (insertional mutagenesis) [40], the manufacturing process of DNA vaccines is inexpensive, rapid, and scalable for a larger population [41]. DNA vaccines are administered to the host via several vehicles, such as bacterial plasmids, with DNA in the minicircle or linear form. The DNA construct encoding the target antigen should translocate to the nucleus for the transcription to mRNA that is then transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm for translation and expression of the DNA-encoded vaccine antigen (Figure 3). The translated vaccine antigens are presented by both MHC class I and class II molecules of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). If the target antigens are secreted, they can be recognized by B cell receptors in naive B cells. Activated APC migrates to the draining lymph nodes to present antigenic peptides to CD4 and CD8 T cells for activation of the adaptive immune system. Delivery of DNA vaccines involves a gene gun, jet injector, and microneedle, with electroporation of cells to create transient pores in the cell membrane [42]. DNA vaccines required a higher dose or more frequent injections than other vaccine platforms owing to low immunogenicity in large animals and humans. Consistently, DNA vaccines required more than two administrations to trigger humoral immune response compared to virus-like particle (VLP) vaccination [43]. The first DNA COVID-19 vaccine (ZyCoV-D) developed by Zydus Cadila was available in India, which was administered three times by using a needleless device with a high-pressure stream [44].

Figure 3.

Fates of DNA, RNA, and protein-based vaccines. After the DNA vaccine is taken up by antigen-presenting cells (APCs), the DNA should undergo a two step-journey of transcription and translation to express the encoded protein. After un-coating of the nano-system, the released mRNA undergoes translation to express the encoded protein through a cytosolic antigen process. Vaccine antigen can be presented to naive T cells through the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) pathways. CD8 + T cell is predominantly activated by endogenously expressed antigens presented on MHC class I molecules. CD4 + T helper cell activation is triggered through MHC class II from APC. In humoral immune response, B cells cognate vaccine antigens and retrieve CD4 + T cells for the differentiation into antibody secreting plasma cells. The protein-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine directly and specifically targets B cells via B cell-receptors and APCs. This figure was created using the BioRender web-based software.

The cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS)–stimulator of interferon genes (STING) pathway is a cytosolic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) sensor of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Circular DNA vector can be recognized via cGAS of cytosolic DNA sensor, which induces type-I interferons in response to DNA [45]. cGAS detects cytosolic foreign DNA and produces the cyclic dinucleotide, cGAMP, which binds the adaptor molecule, STING, whose expression is correlated with that of type I IFN gene and interferon stimulated genes (ISGs). Mechanistically, intracellular transfected DNA activates the cGAS-STING pathway and induces the expression of the 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS) family proteins, leading to the activation of RNaseL and degradation of mRNA derived from DNA vectors [45].

Vector-delivered COVID-19 vaccines.

In contrast to low immunogenicity of DNA vaccines, replication incompetent vector vaccines were approved for use in human vaccination in advance prior to the completion of phase 3 trials: one was adenovirus type 5 based COVID-19 vaccine (Ad5-nCoV) developed by Can Sino in China [46] and another was Gam-COVID-Vac/Sputnik V vaccine by Gamaleya Research Institute in Russia [47,48]. Soon later, two additional viral vector vaccines based on recombinant adenoviruses have been approved for emergency use authorization in human vaccination against COVID-19. ChAdOx-nCoV-19 was based on chimpanzee adenovirus developed by Oxford/AstraZeneca [49], and Ad26. COV2.S (Janssen’s vaccine) was based on adenovirus type 26 [50].

RNA-based COVID-19 vaccines.

The COVID-19 mRNA vaccine platforms mRNA-1273 (Moderna) and BNT162b2 (Pfizer/BioNTech) were unprecedently, rapidly, and successfully developed, resulting in earlier acquiring the license of emergency use authorization for human vaccination against COVID-19, compared to other vaccine platforms [51,52]. Both mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 are pre-fusion stabilized full-length S protein with transmembrane (TM) domain [53,54]. In contrast to DNA vaccines requiring delivery to intracellular nuclei, the mRNA vaccines need only a shortcut delivery to the cytoplasm (Figure 3) and showed higher efficacy at a lower dose than comparable DNA vaccines. Booster dose of mRNA SARS-CoV-2 S vaccines could induce neutralizing antibody activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants [55]. The fusion of early endosome containing lipid nanoparticle (LNP)-mRNA and lysosome generally initiates acidification of the endosomal environment (pH 5.5–6.2) [56]. Trapped in endosomes in getting lower pH, positively charged lipid LNP interacts with the negatively charged endosomal membrane, which may promote membrane destabilization and facilitate endosomal escape of mRNA encoding for SARS-CoV-2 S protein [57]. After unloading from LNPs, mRNA in the cytosol translates into the S protein synthesis at the ribosomes. The translated S protein is expressed on the cell membranes or secreted to the extracellular space, depending on the presence of transmembrane domain of S-encoding mRNA, and then recognized by B-cell receptor for induction of S-specific antibodies. Also, S protein antigens are synthesized intracellularly or internalized via endocytosis into antigen-presenting cells and loaded onto MHC class II molecules to present the antigen to the T cells, inducing CD4 T cell immunity, promoting the affinity maturation and isotype-switching of antibodies (Figure 3). Partially degraded S peptides by the proteasome in the APCs are incorporated into MHC class I complexes, which are then transported to the cell surface and presented as antigens to CD8+T cells [58].

The translated proteins of mRNA vaccines are presented via MHC-I and MHC-II molecules on APCs for efficient induction of adaptive immune responses. Enhancing the stability of mRNA vaccine is critical for its potency as a vaccine. Capping 7-methyl-guanosine cap (m7G) pppNmN to the 5’-end of the mRNA chain protects mRNA from the action of 5’ to 3’ exonuclease and enhances the binding to eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) to form a complex with protein synthesis initiation factors and ribosomes [59,60]. Moreover, the incorporation of chemically modified nucleosides, such as pseudouridine and 1-methylpseudouridine [61], allows mRNA molecules to escape the intracellular signaling triggers (TLR7/8) [62], resulting in enhanced mRNA translation, antigen expression, and adaptive immune responses [63]. Codon optimization can also impact mRNA stability and translation efficiency by increasing the GC-rich sequence and the availability of the more abundant tRNA species [64]. Recent research and technological breakthrough have enabled mRNA to be a compelling vaccine platform by overcoming critical limitations, such as instability, delivery, safety, and immunogenicity [59,65].

Whole inactivated virus vaccines.

Whole inactivated virus vaccines (WIV) platform is one of the traditional approaches used for combating SARS-CoV-2. The Chinese WIV vaccines, BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) and CoronaVac [66,67] (Sinovac Biotech Ltd.), were approved for emergency use by the WHO in May and June 2021 [68]. Corona Vac uses β-propiolactone (BPL) for inactivation and is administered with an aluminum hydroxide adjuvant. Covaxin (Bharat Biotech), the Indian WIV vaccine, was approved for emergency use in India at the beginning of 2021. This WIV vaccine involves BPL inactivation and is administered with the adjuvant, Algel-IMDG (chemosorbed imidazoquinoline absorbed on alum hydroxide gel). The IMDG component is a TLR 7/8 agonist that induces a Th1-type immune response to balance the Th2-inducing properties of alum [69].

In earlier preclinical studies with vaccines against SARS-CoV, administration of WIV and recombinant protein vaccines, as well as virus-vectored vaccines resulted in similar cellular infiltrate levels in the lungs or liver [70]. Two- to 7-month old infants administered formalin-inactivated WIV vaccine against the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) were found to experience exacerbated respiratory illness [71] due to the Th2 type biased immune response, overflowing mucus production, and infiltration of host inflammatory cells (neutrophils and eosinophils) in the lungs. To date, COVID-19 vaccines in nonhuman primate immunization or in human clinical trials have not presented evidence of respiratory disease enhancement following the worldwide use of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines approved for emergency use [72].

Protein-based vaccines.

Over the past 50 years, recombinant expression systems, such as bacterial, yeast, insect, and mammalian expression cells, have been established for foreign protein production, leading to the licensure of subunit vaccines or virus-like particle (VLP) vaccines. However, these vaccines have several disadvantages, such as high cost of purification processes, time-consuming, and requirement of an adjuvant to increase the immune responses. Nonetheless, owing to the safety advantages, the protein-based vaccine platform was later approved for emergency use as a COVID-19 vaccine. The first protein VLP vaccine against hepatitis B virus (HBV) was prepared by using the Saccharomyces cerevisiae expression system and approved as Recombivax in 1986 [73]. The currently licensed prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines are based on self-assembled VLPs that contain the L1 capsid protein: Gardasil (Merck), Cervarix (GSK), Gardasil-9 (Merck), and Cecolin (Innovax) [74].

As a recombinant protein vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, Corbevax produced using the yeast (P. pastoris) expression system targets the RBD of the spike protein of SARS-CoV and was demonstrated to induce virus neutralizing antibodies at high levels. This vaccine contains aluminum hydroxide and a CpG oligonucleotide as adjuvant and is completing phase 3 clinical trials after displaying a highly favorable safety and immunogenicity profile in India. Soberana 2 expressed in mammalian (CHO) cells is also an RBD candidate that is conjugated to a tetanus toxoid carrier protein via a free cysteine and is administered with aluminum hydroxide adjuvant. This vaccine has received emergency use authorization in Cuba and Iran. The MVCCOV1901 (Medigen Vaccine Biologics Corporation in Taiwan) targets the pre-fusion spike protein ectodomain. MVCCOV1901 is produced in CHO cells and administered with the adjuvant, aluminum hydroxide and CpG1018, and has been approved for emergency use in Taiwan.

In regard to the VLP vaccine platform, plant-derived VLP vaccine, CoVLP (Medicago) [75,76], targeting the spike protein trimer formulated with AS03, has recently been licensed for human vaccination in Canada. SCB-2019 (Clover Pharmaceuticals) [77,78] is a trimer-like spike protein that fuses with a self-assembling C-terminus of human type I procollagen. SCB-2019 is expressed in CHO cells and formulated with a combination of adjuvant CpG and aluminum hydroxide.

NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) which is expressed in the Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9 insect cell system and formulated with a Matrix-M saponin adjuvant has been proven to be safe and highly immunogenic, capable of inducing high levels of neutralizing antibodies. When human antisera were tested against the beta variant of SARS-CoV-2, NVX-CoV2373 vaccine induced cross-protective virus neutralizing antibodies with a highly acceptable safety profile, revealing rare adverse events in phase 3 studies, and has been approved for use in human vaccination [79,80]. To develop safer, acceptable, and effective vaccines that are easily accessible to immunocompromised individuals, young children, and infants, exploiting the expertise in producing multiple vaccine technologies is more important than reliance on a single specific platform.

5. Efficacy comparison of different COVID-19 vaccines from preclinical and clinical trials

Lessons that we have learned from a short history of comparative outcomes of the ongoing different COVID-19 vaccines would provide insightful information to rapidly develop future vaccines against emerging infectious pathogens. In response to the urgent need for COVID-19 vaccines, pre-clinical trials of many candidates in appropriate animal models such as non-human primates (NHP) were carried out in parallel with initial clinical trials once COVID-19 vaccine candidates demonstrated high neutralizing titers and T helper type 1 (Th1) immune responses.

The Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccine was ranked as a top level in terms of inducing neutralizing titers (501–3,481), Th1-biased response, and viral clearance in the upper and lower respiratory in Rhesus macaques with 10 μg or 100 μg mRNA prime-boost doses [53,81]. Consistent, phases 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials with mRNA-1273 (100 μg dose) reported the highest levels of neutralizing titers approximately four- to eightfolds higher than convalescent sera and 95% protective efficacy (Table 1) [82]. Similarly, Pfizer BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine was reported to effectively induce neutralizing antibody titers (eighfolds higher than convalescent human sera) and Th1 immune responses, and clear lung viral titers in Rhesus macaques with 30 μg or 100 μg mRNA prime-boost doses [83]. Pfizer BNT162b2 mRNA has become one of the most common COVID-19 vaccines used to immunize humans, inducing 2–3 folds higher neutralizing titers than convalescent sera, conferring ~95% efficacy of protection in clinical trials (Table 1) [52,82]. Consistent with this, a recent study using human samples reported that Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA and Novavax protein nanoparticle vaccines provided higher levels of S-specific antibodies than Ad26.COV2 vaccine, whereas mRNA and Ad26.COV2 vaccines showed similarly higher levels of CD4 and CD8 T cell responses than protein nanoparticle vaccine [84]. A platform of mRNA vaccines might provide an effective strategy of vaccination to induce both humoral and memory cellular immune responses compared to other vaccine platforms. Not all mRNA COVID-19 vaccines were successful, implicating company-specific confidential mRNA vaccine technologies. Pre-fusion stabilized S-TM unmodified mRNA vaccines such as CVnCoV (CureVac) [85] and MRT5500 (TranslateBio/Sanofi) [86] did not reach the immunogenicity and efficacy expected [81]. In contrast to Moderna and Pfizer mRNA pre-fusion stabilized vaccines with two consecutive proline substitutions (2P; K986P and V987P) only in the S2 domain, MRT5500 has both mutations in the furin cleavage site and 2P substitutions in S2 and was shown to be more immunogenic in inducing neutralizing antibodies in an NHP model [86], but its detail clinical outcomes are not available.

Table 1.

Currently approved COVID-19 vaccines for use in humans.

| Vaccine platform |

Name | Company/Approved Country | National Clinical Trial (NCT) ID/Injection Route/Age |

Vaccine Efficaciesa | Mode of action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | BNT162b2 [52] | Pfizer/BioNTech/146 countries | IM/16 years old and above | 95% initial efficacy | CD4 and CD8 T cells in mice [54] CD4, CD8, neutralizing Ab in humans |

| mRNA | Spikevax [51] | Moderna/86 countries | NCT04470427/IM/18 years old and above | 95% initial efficacy, high levels of neutralizing Abs | CD4, CD8 T cells in Rhesus Macaques [53], Neutralizing Ab in humans |

| Vectorb | Ad26.COV2.S [48] | Janssen/111 countries | NCT04505722/IM/18 years old and above | Variable (~65–85% initial efficacy) | CD8, CD4 T cells, Neutralizing Ab |

| Vectorb | ChAdOx-nCoV-19 [49] | AstraZeneca/UK, South Korea, other countries | Variable (~65–85% initial efficacy) | CD8, CD4 T cells, Neutralizing Ab | |

| Vectorb | Sputnik V [47] | Gamaleya/74 Countries | NCT04530396/IM/18 years old and above | No related papers | Neutralizing Abs |

| Vectorb | Ad5-nCoV [46] | CanSino/Argentina, Chile, China, Ecuador, Hungary, other countries | NCT04526990/IM/18 years old and above | Variable depending on the cases | CD8, CD4 T cells, (Neutralizing Abs) |

| Protein nanoc | Covovax (NVX-CoV2373) [79] | Novavax/Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand | NCT04533399/IM/18-84 years old | Variable, high levels of neutralizing Abs | CD4, CD8 T cells, Tfh, germinal center B cells and neutralizing Ab in mice and baboon. [88] |

| Protein VLPsd | Covifenz [75] | Medicago/Canada | NCT04636697/IM/individuals 18 to 64 years of age | Variable depending on the cases | CD4 T cells, neutralizing Ab [76] |

| Inactivated virus | CoronaVac [66] | Sinovac Biotech/China | NCT04582344 IM/18 years old and above | Variable depending on the cases | CD4 and CD8 T cells [67], Neutralizing Abs |

| Inactivated virus | COVAXIN (BBV152) [93] | Bharat Biotech/14 countries | NCT04641481/IM/18 years old and above | Variable depending on the cases | Neutralizing Abs [94] |

| DNA | ZyCoV-D [44] | Zydus Cadila/India | NCT04642638/ID/12 years and above | Variable depending on the cases | CD8 T cells, neutralizing Abs |

Vaccine efficacies are not absolute and highly variable depending on the ages and circulating variants at the time of clinical trials and the criteria of efficacies.

Recombinant adenovirus vector-based vaccines.

Protein nanoparticles produced in insect cells and formulated in adjuvant.

Protein virus-like particles produced in plant cells and formulated in adjuvant

IM, intramuscular injection, ID, intradermal injection.

NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) is a pre-fusion stabilized full-length S-TM protein with dual mutations in the cleavage site (QQAQ from RRAR) and 2P in S2, expressed in insect cells, and was formulated into nanoparticle adjuvanted vaccine [87,88]. Vaccination of Cynomolgus macaques with NVX-CoV2373 vaccine (2.5 μg, 5 μg, 25 μg) induced significantly higher levels of neutralizing titers (17,920–23,040 ranges) after boost dose compared to those in mRNA vaccination of NHP, and resulted in complete clearance of viral titers in the upper and lower airways after challenge [89]. In clinical trials, NVX-CoV2373 showed similar potency of neutralizing titers and efficacy as those observed after mRNA (BNT162b2, mRNA-1273) vaccination [82]. RBD and S-Trimer protein vaccines could induce immunity, contributing to clearing lung viral titers in NHP [81] but further clinical data are not available.

Non-replicating vector vaccine ChAdOx-nCoV-19 (prime-boost) dose and Ad26.COV2.S prime dose induced moderate ranges of neutralizing titers (10–160 titers) and Th1 responses, and complete lung viral clearance in Rhesus macaques after challenge [49,50]. Prime dose Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen’s vaccine) and prime-boost dose ChAdOx-nCoV-19 (AstraZeneca) in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials induced protective levels of neutralizing titers (similar to or lower than convalescent sera) [47]. Early phase 3 clinical data indicated a wider range of ~60% to 85% efficacy (Table 1), which were lower levels than those induced by mRNA vaccination [47]. The Pfizer vaccine was found to be more protective than the AstraZeneca vaccine [82]. Another clinical study also reported that vaccinee with BNT162b2 mRNA induced many folds higher neutralizing antibody titers than ChAdOx-nCoV-19 vaccination [90].

Adjuvanted inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (3–6 μg PiCoVacc/SinoVac; 4–8 μg BBIBP-CoV/China) induced low to moderate levels of neutralizing antibody titers (10–200 ranges) and provided partial clearance of virus in upper respiratory tracts and complete protection in lower respiratory tracts after challenge of vaccinated Rhesus macaques [91,92]. A whole-virion inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine BBV152 (Covaxin) approved in India was well tolerated with an overall estimated vaccine efficacy of 77.8% in adults (age ≥18 years) who were healthy or had stable chronic medical conditions with no safety concerns [93]. Covaxin-induced antibodies were also found to neutralize against beta and delta variants in-vitro [94]. After the peak of the second wave of COVID-19, Covaxin showed an effectiveness of 29% for preventing breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare workers [95].

In overall phase 1 and 2 clinical studies, adjuvanted NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccine showed the highest levels (3,906) of neutralizing antibody titers with 5 ug dose (Table 1) [79]. Moderna mRNA-1273 showed moderate to high neutralizing titers (343–654) with 100 ug mRNA dose [96], followed by Pfizer BNT162b2 inducing a range of 147 and 361 titers in elderly and healthy adults, respectively [97]. AstraZeneca ChAdOx-nCoV-19 induced low to median ranges 29–136 neutralizing titers [98], and SinoPharm inactivated whole virus moderate ranges 121–316 neutralizing titers [99]. NVX-CoV2373 took a longer time to obtain a licensure for use in vaccination for the general population.

6. The concerns of breakthrough infections and need for third dose booster vaccination

The success and high efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines were considered a promising measure to stop the ongoing pandemic. Immune correlates of protection include the main neutralizing activity and, to a lesser degree, the quantity of anti-S IgG antibodies and Th1 type T cell immunity. Nonetheless, these protective immune responses declined with time after COVID-19 vaccination, lowering vaccine effectiveness [100,101]. Breakthrough infections are a consequence of lower levels of immunity at the time of infection and transmission efficacy of virus variants that were exposed to an individual. SARS-CoV-2 variants continue to emerge, circulate, and replace prior strains to become a newly dominant strain circulating in human populations since the outbreak of COVID-19 and after vaccination. Rates of breakthrough infections are likely correlated with reduced activity of neutralization against SARS-CoV-2 variants, particularly in older individuals with lower levels of circulating neutralizing antibodies. Antisera of vaccination showed reductions in neutralizing activities against the Beta and Delta variants by 3–15 folds and 1.4–3 folds, respectively [100,102], which might be a cause for breakthrough infection [103]. The Omicron variant is reported to be highly resistant against neutralization by antisera from convalescent patients and vaccinated individuals with BNT162b2 mRNA or AstraZeneca vaccine, contributing to becoming the globally dominant and rapidly spreading variant [104-106].

Progressive reduction in protection against any symptomatic infections and increasing concerns about breakthrough infections were reported after standard prime-boost COVID-19 vaccination [107,108]. A third dose of booster vaccination was demonstrated to significantly reduce viral loads and disease severity when breakthrough infection happens [109], supporting current implementation of booster vaccination policy in many countries. T cell immunity is important in recovery from disease severity and likely remains effective against variants of concern, particularly under a condition for reduced neutralizing activities against variants [110]. T cell responses were induced at higher levels by a strategy of heterologous prime boost (adenovector ChAdOx-nCoV-19 vaccine prime – mRNA vaccine second dose) than those by homologous vaccination schedule [90].

Regarding the third booster vaccination, full-dose Pfizer or half-dose Moderna mRNA vaccine was found to effectively boost IgG responses in the vaccinee with prior ChAdOx-nCoV-19 AstraZeneca or the same mRNA vaccine [111], which is currently adopted in many countries. Cellular responses were effectively boosted with the third dose of mRNA or Ad26. COV2.S for the prior vaccinee with AstraZeneca or the same mRNA vaccine [111]. Cellular responses were not boosted by homologous booster vaccination with ChAdOx-nCoV-19 AstraZeneca probably due to the vector immunity, whereas NVX-CoV2373 booster was effective in enhancing immune responses in ChAdOx-nCoV-19 vaccinee [111]. Inactivated whole virus vaccine was least effective in boosting immune responses specific for S in the prior ChAdOx-nCoV-19 or mRNA vaccinee [111]. Overall, mRNA vaccines were the highly recommended vaccine platforms for booster dose in prior naturally infected individuals and vaccinees with the same mRNA or other COVID-19 vaccines.

Prior to the emergence of the Delta variant, SARS-CoV-2 reinfection was rare among individuals with laboratory evidence of a previous infection for up to 1 year [112]. Reinfection risk was increased in association with old age populations (85+ years), comorbid immunologic conditions, and living in congregate care settings. Another recent study reported that individuals with prior infection remained low for the risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and COVID-19 hospitalization for 20 months and vaccination further decreased the risk of reinfection and hospitalization for 9 more months [113]. Clinical data reflecting real-world evidence demonstrated the benefits of protection from additional vaccinations. That is, hybrid immunity of vaccination and prior natural infection were shown to be closely linked to a significantly lower risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and COVID-19 hospitalization than natural immunity alone [113].

7. Future vaccine approaches to better control and protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants

With the increasing rates of breakthrough infections and new variants continuing to emerge, it is becoming evident that COVID-19 vaccines should be newly formulated to better match the emerging variants of concern. Unvaccinated individuals, young adults, and children were the primary targets for a surging wave of infection cases and hospitalizations when new variants such as Delta and Omicron emerged. Nonetheless, substantial numbers of breakthrough infections with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron were reported in individuals even with full mRNA vaccine booster dose [114]. Current COVID-19 vaccines were generated by targeting S of the ancestral Wuhan Hu-1 strain and are still being used until now, resulting in the consequences of immune-escaping breakthrough infections when new variants circulate. Several future approaches might be considered to provide protective immunity against emerging variants. (1) An option is to continue further vaccination after the third vaccination with current vaccines, relying on the boost of existing immunity, based on an assumption that COVID-19 pandemic will be ended soon. A concern is that repeat booster vaccination with first-generation spike vaccines would provide suboptimal protection against immune-escaping variants, leading to long duration of COVID-19 waves. (2) First-generation platforms of vaccines based on Wuhan Hu-1 strain should be updated and modified to be more specific for circulating variants. The efficacy outcomes are expected to be difficult, in a wide range of variations, as similarly observed with seasonal influenza vaccination requiring annual updates of vaccine strain components. Concerns are that new variants will continue to evolve faster than the speed of updating the vaccines, and the impact of prior immune imprinting remains unknown.

8. Future strategies for pan-coronavirus universal vaccines

Some European and U.S. governments are en route to lifting the COVID-19 restrictions as the cases decline from their Omicron peak; nonetheless, wearing protective masks remains recommended and isolation is required after COVID-19 infection. However, there are concerns that immunity following natural infection or vaccination has not prevented the emergence and rapid spread of variants of concern, such as the highly transmissible delta (B.1.617.2) and omicron (B.1.1.529) variants. The current COVID-19 vaccine strategies have some drawbacks, including the continuing decline in neutralizing antibodies, the inability to prevent waves of new variants, and the need for frequent booster shots. An ideal broad spectrum ‘universal vaccine’ approach would not only include a broadly protective vaccine strategy but also a broad-spectrum of neutralizing Abs, cellular response, and cross protection that can be applied in different epidemiological scenarios [115,116].

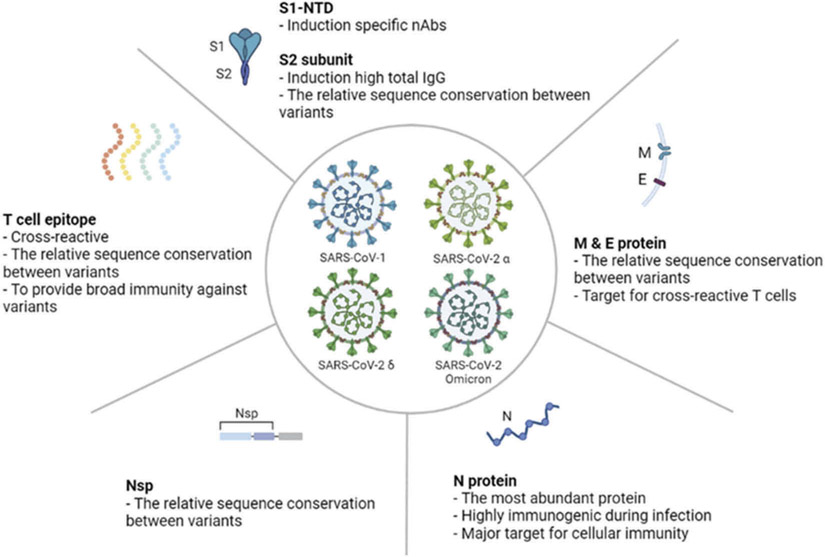

The new vaccine constructs and vehicles delivering multi-epitope vaccines were reported to have an advantage over classical and single epitope vaccines, possibly thanks to the increased chances of recognition by various MHC class molecules and induction of broader humoral and cellular immune responses [117-124]. Sequence alignment and immunoinformatic approaches revealed the highly conserved epitopes for human B cells, CD4 and CD8 T cells in genome sequences among SARS-CoV-2 variants, human and animal coronaviruses, suggesting potential targets for pan-coronavirus vaccines [125]. Studies reporting broadly cross neutralizing antibodies would provide a clue for developing universal coronavirus vaccines. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with broad neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants (alpha, delta) and cross clade sarbecovirus were reported in SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinees and in SARS-CoV-1 survivors with SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination [126,127]. In relevant vaccination approaches to induce broader cross protection, vaccination of mice with chimeric S mRNA composed of NTD, RBD, and S2 (Figure 4) derived from SARS-CoV-1 and 2 viruses could induce broadly neutralizing antibodies and protection against Sarbecovirus of both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 variants [128]. Also, SARS-CoV-1 vaccination or infection of mice was reported to induce cross immunity against SARS-CoV-2, suggesting the presence of common cross-protective immunogens [129]. A cocktail vaccine of spike and non-structural protein (Nsp) appears to represent cross-protective immunogenicity [130]. Immunity against pan-coronavirus coverage might be induced by sequential vaccination with heterologous S vaccine immunogens, either mRNA or adjuvanted protein nanoparticles from representative SARS-CoV clades.

Figure 4.

Universal SARS-CoV-2 vaccine approaches. (A) Spike protein is a major immunogen to induce neutralizing antibodies and, with a certain degree, T cell immunity. (B) Matrix and envelope proteins have a relatively conserved sequence and are targets for cross reactive T cell response against different variants. (C) Abundant nuclear proteins are a target for cellular immunity during SARS-CoV-2 infection. (D) Non-structural protein (Nsp) has a relatively conserved sequence among the SARS-CoV-2 variants. T cell epitopes can induce cross reactive and broad immunity against variants. This figure was created using the BioRender web-based software.

The SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 RBD sequences within S1 were found to have approximately 74% genetic homogeneity [131]. A broad-spectrum candidate for targeting coronavirus is the RBD in S1 because it contains some epitopes conserved among the various coronavirus strains [132]. Vaccination of macaques with adjuvanted SARS-CoV-2 RBD conjugate nanoparticles induced cross neutralizing antibodies against bat coronaviruses, SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 [133], which remains for further confirmation in clinical trials. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibodies revealed unique antibodies with high affinity to all sarbecovirus clades and prophylactic protection in hamsters from viral challenge [134], suggesting the rare conserved (cryptic) epitopes for development of future pandemic coronavirus vaccines. Another study reported that vaccination of mice with nanoparticle vaccines of mosaic RBD proteins composed of SARS-CoV-2 and animal betacoronavi- ruses elicited antibodies cross reactive and neutralizing activity against heterologous pseudotyped coronaviruses [135]. Based on structural vaccinology studies, antibodies were found to recognize B cell epitopes in proximity to the RBD region and hindered ACE2 receptor binding of SARS-COV-2 viruses [136]. The region of fusion peptide is conserved among the variants of SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1). Therefore, linear B cell epitope region (S21P2 epitope peptide) located at the fusion peptide might provide another universal target for inhibiting the fusion of the host cell plasma membrane and SARS-CoV viral envelope [136]. The S2 subunit could be a cross-protective target because of conserved heptad repeat (HR) 1 and 2, which might contribute to inducing broadly neutralizing antibodies against COVID-19, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), and SARS CoV-1 [137]. Five mAbs from COVID-19 convalescent individuals were identified to cross react with the S2 stem helix and neutralize multiple beta coronaviruses, and to reduce SARS CoV-2 viral replication in hamsters [138]. In addition, the NTD of S1 was investigated as a potential target for the development of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine [128,139,140]. In fact, NTD mutations were structurally implicated in epitope recognition of emerging SARS-CoV-2 strains.

9. Expert opinion

The historic success of several current COVID-19 vaccines was hoped to stop the spread of SARS-CoV-2 pandemics. The high efficacy rates of earliest COVID-19 vaccines were estimated by assessing the protection against the outbreak strain of SARS-CoV-2 within a short time after vaccination, when the peak immune responses were induced in a clinical trial cohort. These accelerated vaccine development pipelines and logistics were justified and encouraged under overwhelming uncontrolled pandemics worldwide, in contrast to most other traditional vaccines whose efficacy and safety are carefully monitored for many years following vaccination. Now, we will likely learn new lessons, by encountering the real challenging and difficult issues concerning the still ongoing COVID-19 pandemics. Initial efficacy rates of COVID-19 vaccinations are not being held up with waning immunity and unable to prevent emerging new variants of SARS-CoV-2. The Moderna vaccine likely induces higher magnitudes and durable antibody responses than Pfizer, which might be due to a higher dose and more time between prime and boost. The adenovirus vaccines induce relatively lower levels of but stable antibodies, compared to mRNA vaccines. The approval of new vaccine platforms such as mRNA and adenoviruses within a year of the pandemic outbreak might provide the future potential for improvement in controlling infectious diseases of continuously emerging new variants. Current COVID-19 vaccination regimen might be suboptimum, in the aspects of spacing between immunizations and components of vaccines. Many new challenging issues remain to be solved with a high priority in near future studies.

Over the 2 years of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 variants have continued to evolve, spread, and circulate even in humans with full vaccinations, despite fewer disease symptoms and lower mortality compared to unvaccinated individuals. As RNA viruses are prone to mutate, the SARS-CoV-2 virus will continue to emerge as a new variant of concerns. Prior SARS-CoV-2 variants include Alpha (B.1.1.7, UK strain), Beta (B.1.351, Africa), Gamma (P.1, Brazil), Epsilon (B.1.429, US), Mu (B.1.621, Columbia), and Delta (B.1.617.2, India). Since December 2021, SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529, South Africa) and its subvariants Omicron BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3 are recently becoming dominant strains circulating in most countries. The risk of reinfection has been significantly increased with the emerging Omicron variants [141,142], suggesting immune evasion by the Omicron variant in previously infected or vaccinated individuals. In contrast to the many emerging variants since the COVID-19 pandemic, the most current COVID-19 vaccines remain the same original Wuhan Hu-1 strain, causing a substantial reduction in vaccine efficacy. It will be highly possible that new immune-evading variants will continue to emerge for years. There are mixed views and concerns that SARS-CoV-2 is now transitioning to endemic, in the absence of effective vaccines matching the newly emerging variants. SARS-CoV-2 might be more prone to mutate and evolve into new variants as we have seen since COVID-19, compared to influenza. Seasonal influenza is controlled by annual vaccination and by updating the components of multiple vaccine strains predicted to circulate dominantly worldwide or on northern and southern continents. Comparable to influenza or better preventive strategies should be developed and implemented for more effective and sustainable control of ongoing COVID-19.

A consensus view regarding the effective and safe COVID-19 vaccine platforms has not been researched yet among the different platforms: mRNA, recombinant adenovirus, adjuvanted protein, and inactivated virus vaccine forms. Moderna and Pfizer mRNA vaccines appear to be more effective than other platforms and are mostly recommended for the third or fourth booster shots, regardless of the prime vaccine types. To improve the efficacy of vaccination, frequent updates of the vaccine spike proteins might be required to match the changing variant antigens to ensure efficacy against current and future variants. A strategy to provide cross or universal vaccines will be to supplement spike neutralizing antigens with highly conserved antigens inducing T cell immunity less likely to undergo immune escape mutations. It will be critical to better understand the phenomenon of original antigenic sin, whether preexisting immunity by prior vaccinations or natural infection would skew immune responses toward original antigens rather than new variant antigens. Cocktail multi-variant antigenic formulations or heterologous prime boost strategies remain to be developed and tested.

Different vaccine platforms and adjuvants would differentially activate innate immune cells and inflammatory cytokines via specific innate immune signaling molecules and pathways, subsequently influencing the quality and magnitude of adaptive immune responses. In addition, intrinsic innate antiviral immunity such as cGAMP-STING axis is induced by certain vaccine platforms (mRNA, DNA) and adjuvants. Expression of antiviral genes correlates with antiviral status by interfering with virus entry, by inhibiting transcription and translation, or promoting degradation of viral nucleic acids, which will be important for the control of emerging viral variants nonspecifically. Induction of trained or memory-like innate immunity such as monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells as well as adaptive immunity by adjuvants or COVID-19 vaccinations (mRNA, recombinant adenovirus) will contribute to being refractory to heterologous antigens.

The sooner people are vaccinated against COVID-19, the lesser the chance of continued virus mutation. An ideal vaccine should induce high levels of neutralizing antibodies, elicit robust Th1-biased immune responses, stimulate, and maintain long-lasting immunological memory prior to the emergence of new variants, and provide cross-protection among various coronavirus strains and variants [143]. Polyvalent cocktails of SARS-CoV-2 spike or RBD vaccines in mRNA, adenovirus, or adjuvanted protein nanoparticle vaccine platforms capable of inducing Th1 responses could be developed to generate existing immunity prior to unpredictable variants of coronaviruses. Structure-guided T cell epitope vaccine harboring a globally relevant set of CD4 and CD8 T cell epitopes augments protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants [144] including Omicron [145]. A strategy of removing glycan motifs in the design of SARS-CoV-2 spike vaccine antigens was recently reported to induce more broadly neutralizing antibodies, in a protein subunit or mRNA vaccine platform [146,147], indicating the potential exposure of common epitopes by freeing sugar molecules. Although virus escape from neutralizing Abs can facilitate transmission in vaccinated and convalescent individuals, preexisting cellular and innate immunity and residual neutralizing antibodies might protect against symptomatic infections, severe disease, hospitalization, and mortality. Without safe and effective vaccination for immunocompromised individuals and young children, COVID-19 and new pandemics will continue to exacerbate existing health inequalities in the population with preexisting vulnerabilities and chronic health conditions. Lastly, the extraordinary measures on waiving intellectual property protections for COVID-19 vaccines, which is backed by the Biden government in the U.S., have had a significant impact on bolstering international efforts on vaccine production, promoting global vaccination in developing nations, and would contribute to ending this global pandemic health crisis sooner.

Article highlights.

SARS-CoV-2 infection of the respiratory epithelium leads to an imbalance in vascular homeostasis by hijacking ACE2 in the elderly population and patients with comorbid diseases.

Genomic materials and structural components of SARS-CoV-2 are recognized by pathogen-recognition receptors.

It is important to develop safer and effective vaccines that are easily accessible to immunocompromised individuals and young children, exploiting the expertise in producing multiple vaccine technologies.

‘Universal vaccine’ approaches would induce broadly neutralizing antibodies and innate and cellular immunity, controlling SARS-CoV-2 variants and future pandemics.

Funding

This preparation of review research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2019R1I1A1A01061532), and partially by NIH/NIAID grant AI154656 (S.M.K).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

- 1.Finkel Y, Mizrahi O, Nachshon A, et al. The coding capacity of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;589(7840):125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai MM, Stohlman SA. Comparative analysis of RNA genomes of mouse hepatitis viruses. J Virol. 1981. May;38(2):661–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yogo Y, Hirano N, Hino S, et al. Polyadenylate in the virion RNA of mouse hepatitis virus. J Biochem. 1977;82(4):1103–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samavati L, Uhal BD. ACE2, much more than just a receptor for SARS-COV-2. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glowacka I, Bertram S, Muller MA, et al. Evidence that TMPRSS2 activates the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein for membrane fusion and reduces viral control by the humoral immune response. J Virol. 2011;85(9):4122–4134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simmons G, Gosalia DN, Rennekamp AJ, et al. Inhibitors of cathepsin L prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(33):11876–11881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun G, Sui Y, Zhou Y, et al. Structural basis of covalent inhibitory mechanism of TMPRSS2-Related serine proteases by camostat. J Virol. 2021;95(19):e0086121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li T, Han X, Gu C, et al. Potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies with protective efficacy against newly emerged mutational variants. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan Y, Cao D, Zhang Y, et al. Cryo-EM structures of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV spike glycoproteins reveal the dynamic receptor binding domains. Nat Commun. 2017;10(8):15092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gui M, Song W, Zhou H, et al. Cryo-electron microscopy structures of the SARS-CoV spike glycoprotein reveal a prerequisite conformational state for receptor binding. Cell Res. 2017;27(1):119–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger I, Schaffitzel C. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: balancing stability and infectivity. Cell Res. 2020. Dec;30(12):1059–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shang J, Wan Y, Luo C, et al. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(21):11727–11734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma Q, Liu J, Liu Q, et al. Global percentage of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections among the tested population and individuals with confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(12):e2137257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klinakis A, Cournia Z, Rampias T. N-terminal domain mutations of the spike protein are structurally implicated in epitope recognition in emerging SARS-CoV-2 strains. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:5556–5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang R, Chen J, Gao K, et al. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 mutations in the United States suggests presence of four substrains and novel variants. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sriram K, Insel PA. A hypothesis for pathobiology and treatment of COVID-19: the centrality of ACE1/ACE2 imbalance. Br J Pharmacol. 2020. Nov;177(21):4825–4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geranmayeh MH, Rahbarghazi R, Farhoudi M. Targeting pericytes for neurovascular regeneration. Cell Commun Signal. 2019;17(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fagiani E, Christofori G. Angiopoietins in angiogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2013;328(1):18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cure E, Cumhur Cure M, Vatansev H. Central involvement of SARS-CoV-2 may aggravate ARDS and hypertension. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2020;21(4):1470320320972015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saheb Sharif-Askari N, Saheb Sharif-Askari F, Alabed M, et al. Airways expression of SARS-CoV-2 receptor, ACE2, and TMPRSS2 is lower in children than adults and increases with smoking and COPD. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2020;18:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanez ND, Weiss NS, Romand JA, et al. COVID-19 mortality risk for older men and women. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015;347(6220):1260419.Proteomics; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li W, Qiao J, You Q, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp5 activates NF-kappaB pathway by upregulating SUMOylation of MAVS. Front Immunol. 2021;12:750969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sampaio NG, Chauveau L, Hertzog J, et al. The RNA sensor MDA5 detects SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin X, Riva L, Pu Y, et al. MDA5 governs the innate immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in lung epithelial cells. Cell Rep. 2021;34(2):108628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang DM, Geng TT, Harrison AG, et al. Differential roles of RIG-I like receptors in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mil Med Res. 2021;8(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada T, Sato S, Sotoyama Y, et al. RIG-I triggers a signaling-abortive anti-SARS-CoV-2 defense in human lung cells. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(7):820–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li N, Hui H, Bray B, et al. METTL3 regulates viral m6A RNA modification and host cell innate immune responses during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Rep. 2021;35(6):109091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loo YM, Gale M Jr. Immune signaling by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity. 2011;34(5):680–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng M, Karki R, Williams EP, et al. TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol. 2021;22(7):829–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Theobald SJ, Simonis A, Georgomanolis T, et al. Long-lived macrophage reprogramming drives spike protein-mediated inflammasome activation in COVID-19. EMBO Mol Med. 2021;13(8):e14150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlee M, Hartmann G. Discriminating self from non-self in nucleic acid sensing. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016. Sep;16(9):566–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salvi V, Nguyen HO, Sozio F, et al. SARS-CoV-2-associated ssRNAs activate inflammation and immunity via TLR7/8. JCI Insight. 2021;6:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell GR, To RK, Hanna J, et al. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1, and HIV-1 derived ssRNA sequences activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages through a non-classical pathway. iScience. 2021;24(4):102295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agostini L, Martinon F, Burns K, et al. NALP3 forms an IL-1beta-processing inflammasome with increased activity in Muckle-Wells autoinflammatory disorder. Immunity. 2004;20(3):319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Madden EA, Diamond MS. Host cell-intrinsic innate immune recognition of SARS-CoV-2. Curr Opin Virol. 2022. Feb;52:30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siu KL, Yuen KS, Castano-Rodriguez C, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus ORF3a protein activates the NLRP3 inflammasome by promoting TRAF3-dependent ubiquitination of ASC. FASEB J. 2019;33(8):8865–8877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nieto-Torres JL, Verdia-Baguena C, Jimenez-Guardeno JM, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus E protein transports calcium ions and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Virology. 2015;485:330–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah A. Novel coronavirus-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation: a potential drug target in the treatment of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glenting J, Wessels S. Ensuring safety of DNA vaccines. Microb Cell Fact. 2005. Sep;6(4):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pardi N, Hogan MJ, Porter FW, et al. mRNA vaccines - a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17(4):261–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shafaati M, Saidijam M, Soleimani M, et al. A brief review on DNA vaccines in the era of COVID-19. Future Virol. 2021. DOI: 10.2217/fvl-2021-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwang HS, Kwon YM, Lee JS, et al. Co-immunization with virus-like particle and DNA vaccines induces protection against respiratory syncytial virus infection and bronchiolitis. Antiviral Res. 2014;110:115–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mallapaty S. India’s DNA COVID vaccine is a world first - more are coming. Nature. 2021. Sep;597(7875):161–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu Y, Fang Y, Lin Z, et al. Inhibition of cGAS-Mediated interferon response facilitates transgene expression. iScience. 2020;23(4):101026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halperin SA, Ye L, MacKinnon-Cameron D, et al. Final efficacy analysis, interim safety analysis, and immunogenicity of a single dose of recombinant novel coronavirus vaccine (adenovirus type 5 vector) in adults 18 years and older: an international, multicentre, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10321):237–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature. 2020. Oct;586(7830):516–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Shcheblyakov DV, et al. Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet. 2021;397(10275):671–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Doremalen N, Lambe T, Spencer A, et al. ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine prevents SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2020;586(7830):578–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mercado NB, Zahn R, Wegmann F, et al. Single-shot Ad26 vaccine protects against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2020;586(7830):583–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397(10287):1819–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Corbett KS, Flynn B, Foulds KE, et al. Evaluation of the mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 in nonhuman primates. N Engl J Med. 2020;28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laczko D, Hogan MJ, Toulmin SA, et al. A single immunization with nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines elicits strong cellular and humoral immune responses against sARS-CoV-2 in mice. Immunity. 2020;53(4):724–732 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gruell H, Vanshylla K, Tober-Lau P, et al. mRNA booster immunization elicits potent neutralizing serum activity against the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant. Nat Med. 2022;19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maugeri M, Nawaz M, Papadimitriou A, et al. Linkage between endosomal escape of LNP-mRNA and loading into EVs for transport to other cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hou X, Zaks T, Langer R, et al. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater. 2021;6(12):1078–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park JW, Lagniton PNP, Liu Y, et al. mRNA vaccines for COVID-19: what, why and how. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(6):1446–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeeva S, Kim KH, Shin CH, et al. An update on mRNA-based viral vaccines. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fischer PM. Cap in hand: targeting eIF4E. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(16):2535–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kariko K, Muramatsu H, Welsh FA, et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol Ther. 2008;16(11):1833–1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kariko K, Buckstein M, Ni H, et al. Suppression of RNA recognition by toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23(2):165–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jackson NAC, Kester KE, Casimiro D, et al. The promise of mRNA vaccines: a biotech and industrial perspective. NPJ Vaccines. 2020;5:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Presnyak V, Alhusaini N, Chen YH, et al. Codon optimality is a major determinant of mRNA stability. Cell. 2015;160(6):1111–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guan S, Rosenecker J. Nanotechnologies in delivery of mRNA therapeutics using nonviral vector-based delivery systems. Gene Therapy. 2017. Mar;24(3):133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanriover MD, Doganay HL, Akova M, et al. Efficacy and safety of an inactivated whole-virion SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac): interim results of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial in Turkey. Lancet. 2021;398(10296):213–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Escobar A, Reyes-Lopez FE, Acevedo ML, et al. Evaluation of the immune response induced by coronaVac 28-day schedule vaccination in a healthy population group. Front Immunol. 2021;12:766278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thanh Le T, Andreadakis Z, Kumar A, et al. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(5):305–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Colak E, Leslie A, Zausmer K, et al. RNA and imidazoquinolines are sensed by distinct TLR7/8 ectodomain sites resulting in functionally disparate signaling events. J Immunol. 2014;192(12):5963–5973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haynes BF, Corey L, Fernandes P, et al. Prospects for a safe COVID-19 vaccine. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim HW, Canchola JG, Brandt CD, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89(4):422–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME. Whole inactivated virus and protein-based COVID-19 vaccines. Annu Rev Med. 2022. Jan;73(1):55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stevens CE, Taylor PE, Tong MJ, et al. Yeast-recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Efficacy with hepatitis B immune globulin in prevention of perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission. JAMA 1987;257(19):2612–2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Qian C, Liu X, Xu Q, et al. Recent progress on the versatility of virus-like particles. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hager KJ, Perez Marc G, Gobeil P, et al. Efficacy and safety of a recombinant plant-based adjuvanted covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(22):2084–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ward BJ, Gobeil P, Seguin A, et al. Phase 1 randomized trial of a plant-derived virus-like particle vaccine for COVID-19. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):1071–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liang JG, Su D, Song TZ, et al. S-Trimer, a COVID-19 subunit vaccine candidate, induces protective immunity in nonhuman primates. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Richmond P, Hatchuel L, Dong M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of S-Trimer (SCB-2019), a protein subunit vaccine candidate for COVID-19 in healthy adults: a phase 1, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10275):682–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Keech C, Albert G, Cho I, et al. Phase 1–2 Trial of a SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike protein nanoparticle vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2320–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shinde V, Bhikha S, Hoosain Z, et al. Efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 vaccine against the B.1.351 variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(20):1899–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mukhopadhyay L, Yadav PD, Gupta N, et al. Comparison of the immunogenicity & protective efficacy of various SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidates in non-human primates. Indian J Med Res. 2021;153(1 & 2):93–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1205–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vogel AB, Kanevsky I, Che Y, et al. BNT162b vaccines protect rhesus macaques from SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;592(7853):283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang Z, Mateus J, Coelho CH, et al. Humoral and cellular immune memory to four COVID-19 vaccines. bioRxiv. 2022;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rauch S, Roth N, Schwendt K, et al. mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine candidate CVnCoV induces high levels of virus-neutralising antibodies and mediates protection in rodents. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kalnin KV, Plitnik T, Kishko M, et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine MRT5500 in preclinical animal models. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bangaru S, Ozorowski G, Turner HL, et al. Structural analysis of full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein from an advanced vaccine candidate. Science. 2020;370(6520):1089–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tian JH, Patel N, Haupt R, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein vaccine candidate NVX-CoV2373 immunogenicity in baboons and protection in mice. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Guebre-Xabier M, Patel N, Tian JH, et al. NVX-CoV2373 vaccine protects cynomolgus macaque upper and lower airways against SARS-CoV-2 challenge. Vaccine. 2020;38(50):7892–7896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu X, Shaw RH, Stuart ASV, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of heterologous versus homologous prime-boost schedules with an adenoviral vectored and mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Com-COV): a single-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10303):856–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang H, Zhang Y, Huang B, et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate, BBIBP-CorV, with potent protection against SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2020;182(3):713–721 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gao Q, Bao L, Mao H, et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369(6499):77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ella R, Reddy S, Blackwelder W, et al. Efficacy, safety, and lot-to-lot immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (BBV152): interim results of a randomised, double-blind, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10317):2173–2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sapkal GN, Yadav PD, Ella R, et al. Inactivated COVID-19 vaccine BBV152/COVAXIN effectively neutralizes recently emerged B.1.1.7 variant of SARS-CoV-2. J Travel Med. 2021;28(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Behera P, Singh AK, Subba SH, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccine (Covaxin) against breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection in India. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18(1):2034456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, et al. An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - Preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(20):1920–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Walsh EE, Frenck R, Falsey AR, et al. RNA-Based COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 selected for a pivotal efficacy study. medRxiv. 2020. DOI: 10.1101/2020.08.17.20176651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Folegatti PM, Ewer KJ, Aley PK, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10249):467–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xia S, Duan K, Zhang Y, et al. Effect of an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 on safety and immunogenicity outcomes: interim analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2020;324(10):951–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Widge AT, Rouphael NG, Jackson LA, et al. Durability of responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(1):80–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Naaber P, Tserel L, Kangro K, et al. Dynamics of antibody response to BNT162b2 vaccine after six months: a longitudinal prospective study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;10:100208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lustig Y, Zuckerman N, Nemet I, et al. Neutralising capacity against Delta (B.1.617.2) and other variants of concern following Comirnaty (BNT162b2, BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccination in health care workers, Israel. Euro Surveill. 2021;26(26). DOI: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.26.2100557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shastri J, Parikh S, Aggarwal V, et al. Severe SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough reinfection with delta variant after recovery from break-through Infection by alpha variant in a fully vaccinated health worker. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:737007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hoffmann M, Kruger N, Schulz S, et al. The omicron variant is highly resistant against antibody-mediated neutralization: implications for control of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cell. 2022;185(3):447–456 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Planas D, Saunders N, Maes P, et al. Considerable escape of SARS-CoV-2 omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2022;602(7898):671–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Liu L, Iketani S, Guo Y, et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2022;602(7898):676–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chemaitelly H, Tang P, Hasan MR, et al. Waning of BNT162b2 vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in Qatar. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(24):e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tartof SY, Slezak JM, Fischer H, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine up to 6 months in a large integrated health system in the USA: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10309):1407–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]