Abstract

Sexual attraction and perception, governed by separate genetic circuits in different organs, are crucial for mating and reproductive success, yet the mechanisms of how these two aspects are integrated remain unclear. In Drosophila, the male-specific isoform of Fruitless (Fru), FruM, is known as a master neuro-regulator of innate courtship behavior to control perception of sex pheromones in sensory neurons. Here we show that the non-sex specific Fru isoform (FruCOM) is necessary for pheromone biosynthesis in hepatocyte-like oenocytes for sexual attraction. Loss of FruCOM in oenocytes resulted in adults with reduced levels of the cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs), including sex pheromones, and show altered sexual attraction and reduced cuticular hydrophobicity. We further identify Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (Hnf4) as a key target of FruCOM in directing fatty acid conversion to hydrocarbons in adult oenocytes. fru- and Hnf4-depletion disrupts lipid homeostasis, resulting in a novel sex-dimorphic CHC profile, which differs from doublesex- and transformer-dependent sexual dimorphism of the CHC profile. Thus, Fru couples pheromone perception and production in separate organs for precise coordination of chemosensory communication that ensures efficient mating behavior.

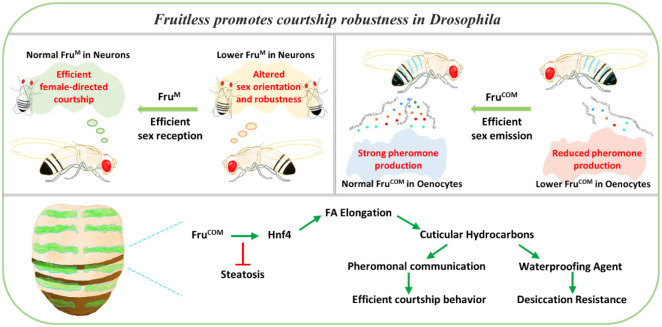

Teaser

Fruitless and lipid metabolism regulator HNF4 integrate pheromone biosynthesis and perception to ensure robust courtship behavior.

Introduction

Chemical sensing, regarded from an evolutionary perspective as the oldest one, is common to all organisms, which are surrounded by a world full of odors emitted from conspecific or heterospecific individuals and the environment (1). Chemical communication is fundamental to social behaviors such as con-specific recognition, courtship, aggression, aggregation, and avoidance. Many animals, including insects, rely on chemical cues to locate and select appropriate mating partners for reproductive success. Insect chemical communication involves emission and perception of chemical cues (pheromones) and requires coordination of different organs that are involved in pheromone biosynthesis and sensing, respectively (2). Drosophila, with its long tradition in behavioral studies, is an ideal model to explore the evolution and diversity of pheromones associated with the diverse array of social behaviors, and the ethological context connecting chemical communication to behavioral and systemic processes. Although significant progress has been made in the Drosophila model during the past decades in unraveling the receptors and neural circuits for pheromone detection that give rise to innate behaviors, whether pheromone emission and perception can be regulated by the same upstream regulators remain unclear.

Insect cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs), derived from long-chain fatty acids, are important for desiccation resistance (3–5), cold tolerance (6) and starvation resistance (7). Some CHCs function as sex pheromones for mate recognition (8–12). As in other insects, specialized hepatocyte-like oenocytes, located in the inner surface of the abdominal cuticle, are the primary site for biosynthesis of very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) and VLCFA-derived hydrocarbons in D. melanogaster (11, 13–15). Oenocytes are also the major site for ROS metabolism, proteasome-mediated protein catabolism, xenobiotic metabolism, ketogenesis, and peroxisomal beta-oxidation (16–22). Although the biosynthetic pathway for CHCs is active in both male and female oenocytes, the CHC profile shows apparent sexual dimorphism (23). In most populations of D. melanogaster, sexually dimorphic expression of enzymes such as elongase F (eloF) and desaturase F (desatF) leads to female-biased enrichment of several CHCs including 7,11-HD and 7,11-ND (24, 25). Further proof that the CHC composition could be affected by sex-determination genes has been shown by ectopic expression of transformer (tra) in male oenocytes, which upregulates eloF and feminizes the CHC profile (25, 26). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the sexual dimorphism of CHC biosynthesis remain elusive (27).

Pheromone perception in Drosophila requires the neuronal function of fruitless (fru), a master regulator of the sexually dimorphic neural circuits that underlie sexual-dimorphic patterns of courtship (28–31), aggression (32–34), sleep (35) and other behaviors. The fru gene spans over 150 kb of the genome, and harbors P1–P4 promoters (36, 37). The distal P1 promoter is dedicated to the expression of male-specific Fru proteins (FruM), whereas P2–P4 promoters are involved in the production of non-sex-specific Fru proteins (FruCOM) (37–39) (Fig. 4A). Compared with the well-characterized involvement of FruM in neuronal behavior, the precise function of FruCOM in development and behavior is less clear (40, 41).

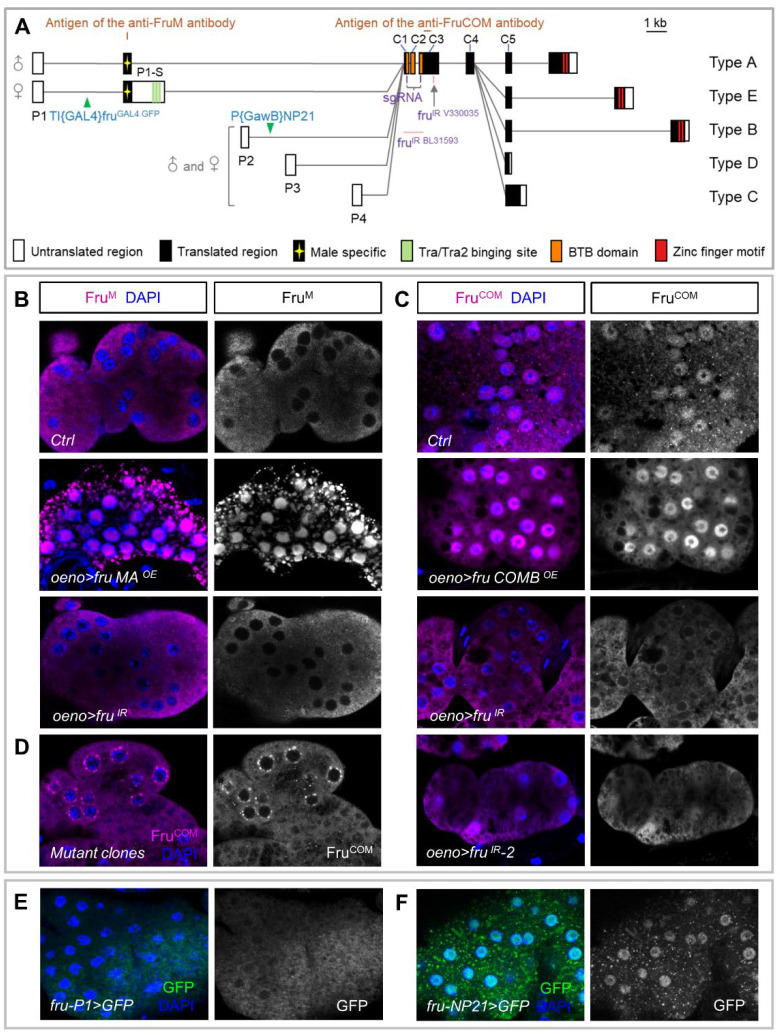

Fig. 4. The fru gene locus and its expression in oenocytes.

(A) Schematic representation of the fru gene locus. Locations of four promoters (P1–P4), the exon-intron organization, and the P-element insertion sites of fruP1 and fruNP21 (green triangles) are shown. Filled and open boxes indicate coding and non-coding exons, respectively. A-E denote isoform-specific exons for types A-E. The start and termination codons are also shown. The regions containing epitopes for the anti-Fru antibodies are indicated. fru gRNA and fru dsRNA sites are displayed. (B and C) Anti-Fru antibodies were used to stain oenocytes, from wild-type flies and overexpression of FruM/FruCOM or knockdown of Fru (all isoforms) in oenocytes. (D) Validation of the effectiveness of fru mutant clones by anti-FruCOM staining in oenocytes. (E and F) fru-P1-Gal4 inserted into the first intron and fru-NP21-Gal4 inserted into the second intron of fru, driving UAS-GFP as a reporter to mark the transcriptional level of fru in oenocytes.

In this study, we report that FruCOM is required for CHC biosynthesis in adult oenocytes of both sexes for chemical communication and desiccation resistance. Silencing of fru in oenocytes resulted in desiccation-sensitive adults with accompanying social behavioral changes. We further identify evolutionarily conserved Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF4) as a key target of FruCOM to inhibit steatosis and to direct fatty acid conversion to hydrocarbons in oenocytes. Thus, fru is involved in both pheromone biosynthesis and perception by distinct splicing isoforms in separate organs, bringing sexual attraction and perception under the control of a single gene.

Results

fru is required in both the nervous system and oenocytes for innate courtship behavior.

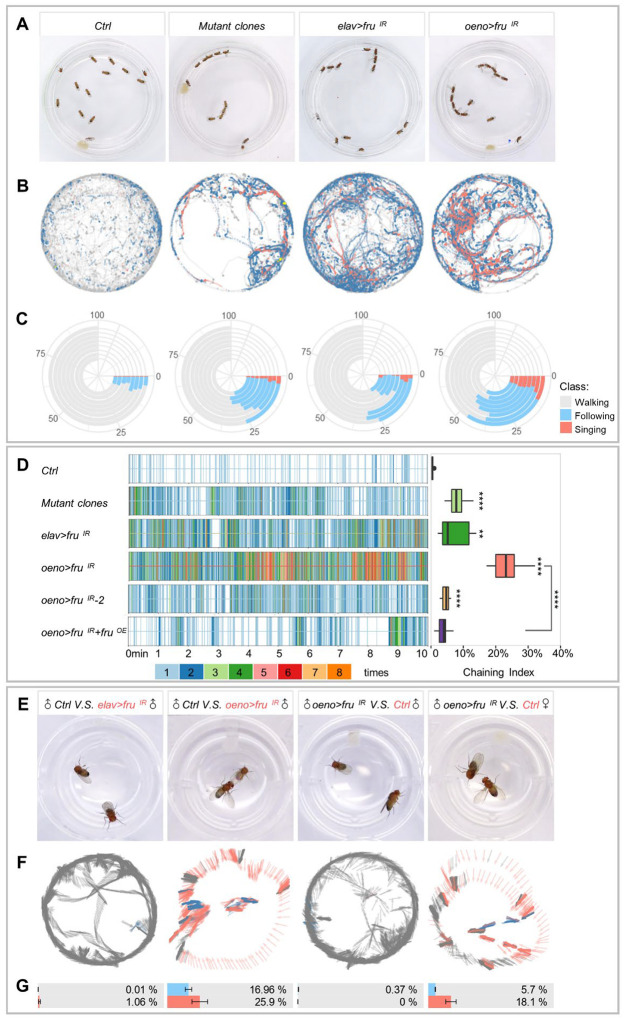

To understand the function of FruCOM isoforms, we induced whole-body clonal mutation of fru using a recently developed mosaic analysis by guide (g) RNA-induced crossing-over (MAGIC) technique, which generates mosaic animals based on DNA double-strand breaks produced by CRISPR/Cas9 (42). The double gRNA design allowed us to eliminate all Fru isoforms in mutant clones randomly induced by a heat-shock inducible Cas9 (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, male flies bearing fru MAGIC clones, which were induced during early 3rd larval instar, exhibited male-male courtship and male chaining behavior (Fig. 1A–D, and movie S1). This behavior is similar to FruM mutant flies reported previously (43, 44), and the male-male courtship phenotype was reproduced when we used a pan-neuron elav-Gal4 to knockdown fru expression (elav>fru IR) with a double-stranded (ds) RNA targeting exon C3, which is present in all Fru isoforms (Fig. 1A–D and 4A, movie S2).

Fig. 1. Loss of fru function in the nervous system or oenocytes alters male courtship behavior.

(A) Representative movie screenshots of fly groups with indicated genotypes. 13 male adults of the same genotype were collected and placed in one chamber. (B) Event maps generated from representative movies of indicated genotypes (1.5-min movie per map). (C) Polarized bar plots illustrating the ratio of each detected behavior. Each bar plot was generated from 8 independent biological replicates (10-min movie per replicate). (D) Rug plots showing the chaining events detected from 10min movies. X axis refers to the time of movie. Each vertical line with different color stands for the number of chaining events detected in a single frame. The corresponding color to the number of events is illustrated in the legend. The box plots of chaining index are quantitative statistics of 8 independent biological replicates. (E) Representative movie screenshots of pair-housed flies with indicated genotypes (black: active party; red: passive beheaded party; control: oeno-Gal4/+). The trajectory and behavioral classification of the active party are shown in F. The arrow indicates the head orientation of the active party flies. The color of the arrow indicates different behavior status (grey: resting/walking; blue: following; salmon: singing) (1.5-min movie per map). Bar plots with error bar are quantitative statistics of 10 min movies of 8 independent biological replicates in G. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. P values are calculated using one-way ANOVA (D) and two-tailed unpaired t-test (G) followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons. n.s., not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

To better assay the behavior phenotype of different fru loss-of-function (LOF) flies, we developed a machine-learning-based automatic fly-behavioral detection and annotation (MAFDA) system to track flies and identify multiple classes of behavior such as chasing, singing, and copulating (fig. S1A–E). The MAFDA platform facilitates visualization of complex behavioral phenotypes under a temporal and spatial overlay, and quantitative comparison of behavioral indexes among different genetic backgrounds. Using this platform, we found that the male-male following, singing and chaining behaviors exhibited in flies with MAGIC-induced fru mutant clones were comparable to or more pronounced than neuronal fru knockdown (Fig. 1D, and fig. S2A). The severe behavior phenotypes displayed by MAGIC fru mosaic flies were thus probably not due only to abnormalities in the nervous system, but also in the production of pheromones.

Oenocytes, which perform certain lipid processing functions, are the principal site for the synthesis of VLCFA-derived CHCs, including sex pheromones, that are associated with a variety of social behaviors in Drosophila (11, 13, 14). Using an oenocyte-specific Gal4 (oeno-Gal4) (45) to knockdown fru (oeno>fruIR) we found that male adult flies displayed male-male courtship and chaining behaviors (Fig. 1A–D, and movie S3). MAFDA analysis revealed that the male-male courtship behaviors exhibited by oeno>fruIR flies were highly pronounced (45% following, 25% chaining and 8% singing; Fig. 1D, and fig. S2A), and could be alleviated by FruCOM overexpression in oenocytes (Fig. 1D, and fig. S2A, C), indicating that the defect was indeed caused by fru silencing. To avoid possible off-target effects of the dsRNA, additional independent fru RNAi lines were used and showed similar male-male courtship phenotypes (Fig. 1D, and fig. S2B). As revealed by MAFDA analysis, the degree of male-male courtship behavior by distinct RNAi lines was consistent with their respective knockdown efficiency (Fig. 1D and 4C, and fig. S2A). In addition, we combined gene-switch (GS) with oeno-Gal4 to knockdown fru after pupal eclosion to avoid a possible role of fru in oenocyte development from its larval progenitors. Indeed, the behavioral phenotypes were similar between fru-depleted flies with or without gene-switch in oenocytes (fig. S2D). These results suggest that fru is required in oenocytes to maintain male courtship rituals.

To verify that the male-male courtship behavior in oeno>fruIR flies was caused by changes in sexual attraction rather than pheromone perception, we performed the single-pair mating experiment by placing a male fly with a headless target in the same chamber. The wild-type male was attracted to the headless male with fru-depletion in oenocytes (oeno>fruIR), but not the headless male lacking Fru in pan-neurons (elav>fruIR) (Fig. 1E–G). By contrast, the male fly with oenocyte-specific fru-knockdown (oeno>fruIR) selected the decapitated wild-type female to initiate courtship but averted the wild-type male (Fig. 1E–G). These results indicate that while males lacking Fru in oenocytes maintain the ability in sexual selection, they are attractive to other males. Further, to determine whether females with oenocyte-depletion of Fru (oeno>fruIR) also show altered sexual attraction, we performed the two-choice courtship assay by putting a wild-type male and two headless female targets (oeno>fruIR and control oeno-Gal4/+) in the same chamber. MAFDA analysis revealed that the courtship index for oeno>fruIR females was ~60% of that of the control group (fig. S2E), suggesting that females with oenocyte fru-knockdown show reduced sexual attractiveness to male flies. Taken together, these results demonstrate that a deficiency of fru in oenocytes modifies sexual attraction in both sexes.

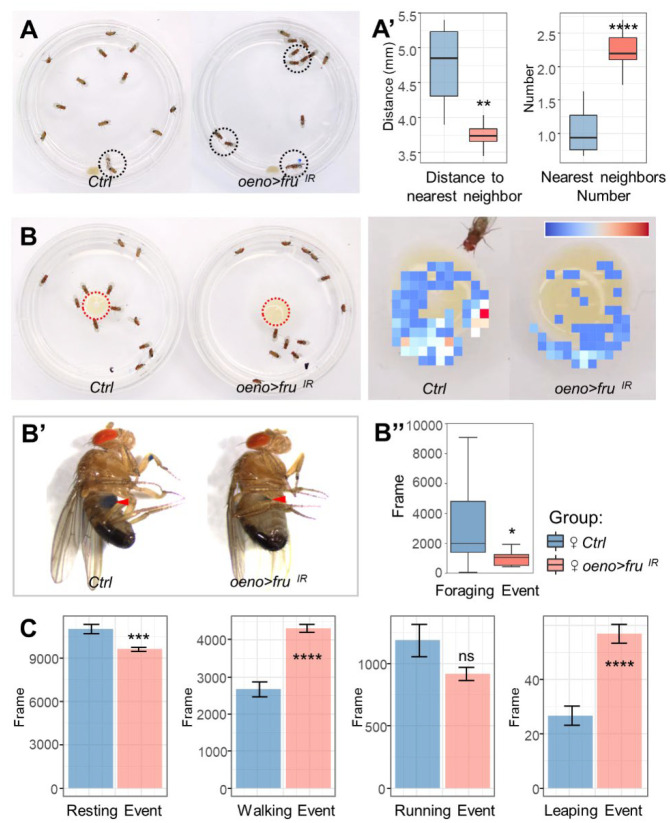

Flies with fru-depletion in oenocytes exhibit aberrant social behavior

In Drosophila, innate social behaviors driven by pheromones include aggregation, male courtship, and female post-mating behaviors (46). To test whether fru knockdown affects social aggregation, we measured the distance between individual flies and their nearest neighbors: their ‘social space’ (47), within a social group. oeno>fruIR flies, on average, showed reduced social space and had more nearby neighbors when compared with the control (Fig. 2A), suggesting that fru expression in oenocytes is necessary for flies to maintain their social distance. Additionally, oeno>fruIR male flies showed reduced foraging behavior in a fixed time window (10 min) (Fig. 2B). MAFDA analysis revealed that the foraging index of the oeno>fruIR males was ~60% of the control group (Fig. 2B”). Measurement of solid food intake in adult via a dye tracer further revealed that flies with fru-depletion ingested less food than wild-type flies over the same time period (1hr) (Fig. 2B’). To rule out that the observed social behavior changes are caused by impaired motor ability, we further examined their locomotion activity during the daytime. Compared with the control group, oeno>fruIR flies were more active, showing a 10% reduction in resting, a 35% increase in walking, and a 55% increase in leaping by MAFDA analysis (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the observed social behavior changes are not caused by impaired motor ability. Taken together, these data provide evidence that fru is required in oenocytes for normal social behavior.

Fig. 2. Social behavior changes in flies with fru-depletion in oenocytes.

(A) Social space behavior. Left: representative images of an open field assay. Black circles indicate flies staying close together. (A’) Quantification of the distance of each fly to its nearest neighbor and the number of surrounding neighbors of each fly for both control (oeno-Gal4/+) and oeno>fruIR males (n = 8 groups of 13 flies for each genotype) (10-min movie per replicate). (B) Control (oeno-Gal4/+) and oeno>fruIR males were analyzed for total number of social interactions in a ‘competition-for-food’ assay. The heatmap on the right shows the degree to which flies gather in the food area. (B’) Measurement of solid food intake in adult using a dye tracer. (B”) Quantification of the total number of feeding times of the flies for control (oeno-Gal4/+) and oeno>fruIR males (n = 10 groups of 13 flies for each genotype) (10-min movie per replicate). (C) Locomotion activity of control (oeno-Gal4/+) and oeno>fruIR males was monitored. From left to right, bar plots show resting events, walking events, running events and jumping events of flies, respectively (n = 8 independent experiments with 13 flies per genotype). For all paradigms, data are represented as mean ± SEM. P values are calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons. Asterisks illustrate statistically significant differences between conditions. n.s., not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

fru function is necessary for CHC production.

In Drosophila, CHCs act primarily as pheromones and play fundamental roles in sexual attraction or repulsion (11, 48). Using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis, we identified 46 distinct chromatogram peaks from the cuticle extracts of wild-type adults and determined the chemical identities of their corresponding hydrocarbons (Fig. 3A, and fig. S3A–B). Subsequent analysis of CHC profiles by GC-MS and comparison of the main cuticular extracts of elav>fruIR and oeno>fruIR males revealed that the levels of total hydrocarbons were reduced by 90% when fru was knocked down in oenocytes, while fru-loss in the nervous system showed a CHC profile largely resembled the wild-type control (Fig. 3B and fig. S4A). Comparison of the CHC content in oeno>fruIR male flies revealed that 7-tricosene (7-T), the principle non-volatile male pheromone (11), was reduced by 97% (Fig. 3B’). Because 7-T mediates repulsion to other males and prevent male-male interactions (45, 49), the drastic reduction of 7-T explains why wild-type males show a strong preference of males with fru-knockdown in the oenocyte (Fig. 1A–D). In addition, oeno>fruIR males showed a 87% decrease of n-tricosane (nC23), another characteristic pheromone of sexually mature fly which negatively regulates courtship and mating (50), may also underly the changed behavior patterns (Fig. 3B’).

Fig. 3. Fru is required in the oenocytes for the biosynthesis of cuticular hydrocarbons.

(A) A schematic of cuticular hydrocarbon extraction and GC-MS analysis. (B) CHCs from adult male flies of each genotype were analyzed using GC-MS. Compared with the control and elav>fruIR males, oeno>fruIR males exhibit significantly lower levels of CHCs. (B’) The absolute contents of total hydrocarbons, male key pheromones (7-T and nC23) carried by a single male were calculated by the loading of internal standards. (C) CHCs from females of each genotype were analyzed using GC-MS. Compared to controls and elav>fruIR females, oeno>fruIR females exhibit lower levels of CHCs. (C’) The absolute contents of total hydrocarbons, female key pheromones (7,11-HD and 7,11-ND) carried by a single female were calculated by the loading of internal standards. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. P values are calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons. Asterisks illustrate statistically significant differences between conditions. n.s., not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

CHCs are highly sexually dimorphic in D. melanogaster, with many of the compounds present in one sex but absent in the other, while shared compounds often differ between sexes (51). To determine whether fru knockdown also alters the CHC profile in female flies, we performed the GS-MS analysis and found that the total CHCs were reduced by 40% in oeno>fruIR females when compared with the control. Different from the male flies, the changes in the CHC profile fall mainly into the CHCs with the chain length beyond C26 (Fig. 3C), which include the female pheromones 7,11-HD and 7,11-ND (45). These results explain why wild-type female are more sexually attractive than females with fru-knockdown in oenocytes (fig. S2E).

The hydrophobic properties of CHCs protect insects from transpirational water loss through insect epicuticle and play a major role in desiccation resistance (14, 52). In oeno>fruIR flies, we found significant reduction of multiple long-chain n-alkanes, including n-heptacosane (nC27) and n-nonacosane (nC29) (Fig. 3B–C and fig. S4A). To test the hydrophobicity of these flies, both male and female adults were dehydrated and incubated in water to assess defects in hydrophobic coating of the cuticle. While control carcasses remained at the surface of the liquid following a 4-hr incubation, oeno>fruIR carcasses sank below the surface (fig. S4B–C). Together, these results suggest that fru is required in both male and female oenocytes for CHC and sex pheromone production.

FruCOM, not FruM, is expressed in the oenocytes

fru is a complex locus with sophisticated precise spatiotemporal control of transcription through four distinct promoters (36, 37, 41) (Fig. 4A). Translation of P1 transcripts in males produces the male-specific FruM proteins that have an amino-terminal extension of 101 amino acids preceding the BTB domain, whereas transcripts from the P2–P4 promoters encode a set of non-sex-specific FruCOM proteins that have essential functions in the development of both sexes (38) (Fig. 4A). All Fru proteins are putative transcription factors containing a common BTB N-terminal domain and five alternatively spliced C-terminus varying in the number and sequence of Zn-finger DNA binding domains (A, B, C, D, or E) (36, 37, 53) (Fig. 4A).

To determine which Fru isoforms are expressed in oenocytes, we stained oenocytes with a FruM-specific antibody (54) and found no signal (Fig. 4B). Using a newly generated polyclonal antibody recognizing an epitope in exon C3, which is present in both FruCOM and FruM isoforms (Fig. 4A), we detected strong signal in oenocyte nuclei in both male and female adults (Fig. 4C). The FruCOM signal was lost in oenocytes with fru RNAi knockdown or with MAGIC induced fru deletion (Fig. 4C–D). Furthermore, we found that fru-P1-Gal4 (55), with the Gal4 inserted in the first intron to mimic the FruM pattern (Fig. 4A), showed no expression in oenocytes (Fig. 4E). In contrast, fru-NP21-Gal4, with its Gal4 located in the second intron (56), possibly under the control of both P1 and P2 promoters (Fig. 4A), drove UAS-GFP expression in oenocytes (Fig. 4F). Together, these results suggest that FruCOM, not FruM, is expressed in oenocytes in both sexes to regulate CHC biosynthesis.

FruCOM controls Hnf4 expression in oenocytes to maintain lipid homeostasis.

In insects, long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) biosynthesis is predominantly derived from palmitate, which is synthesized by Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and Fatty acid synthase 2 (FASN2) (57). After that, they are elongated by the successive action of elongases, desaturases and decarbonylate enzymes, before being converted to hydrocarbons (14, 52, 58). To determine how FruCOM affects hydrocarbon biosynthesis, we generated multiple RNA-Seq datasets from male oenocytes with fru-knockdown by three independent fru-RNAi lines and corresponding control samples, which were then subjected to Principal Component Analysis (PCA). On the PCA plot, the three independent fru-RNAi datasets clustered together, and separate from the control samples (fig. S5A–B). When compared with the wild-type control, we found that the transcripts of genes involved in various steps of VLCFA and hydrocarbon biosynthesis, including ACC, Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (Hnf4), FASN2, Desaturase1 (desat1), Cytochrome P450 4g1 (Cyp4g1), and multiple elongases (CG16904 and CG30008), were reduced in oenocytes with fru-knockdown (Fig.5A). The downregulation of these transcripts was validated by RT-qPCR of RNAs from male oenocytes (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5. Fru controls HNF4 expression in the oenocytes to inhibit steatosis.

(A) Downregulation of VLCFA/hydrocarbon biosynthesis genes in oenocytes with fru-knockdown from two independent replicates. Colors in the heatmap correspond to the scaled FPKM which is shown as a number in each cell. (B) The FA synthesis & elongation pathway from KEGG, with green boxes indicating genes down-regulated in this subset, and RT-qPCR analysis of genes in the VLCFA/hydrocarbon metabolic pathway (controls: blue bars; oeno>fruIR: salmon bars). Transcript levels are normalized to Rp49 mRNA and presented relative to the level of controls. Asterisks illustrate statistically significant differences between conditions. n.s., not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. (C) Bodipy stains are depicted for oenocytes dissected from control and oeno>fruIR males raised on standard diet and starved for 7-day after emergence. Oenocytes are outlined with a yellow dotted line. (D) Triglyceride levels were measured in 7-day old control and oeno>fruIR reared on a standard diet after emergence. Metabolite levels are normalized to total protein and presented relative to the amount in control animals. Red indicates that decapitated whole body was used as the sample material, and blue indicates that only adipose tissue (fat body and oenocytes) was used. (E) TLC analysis shows TAG and FFA levels in adipose tissue of control and oeno>fruIR males. (F) NileRed stains are depicted for oenocytes dissected from fru mutant clones and oeno>fruIR+fruOE males cultured on standard diet. (G) fru-knockdown in oenocytes resulted in decreased HNF4 protein levels. Upper panel, Fru (magenta) colocalized with HNF4 (yellow) in control oenocytes. Lower panel, the level of HNF4 was significantly reduced in oenocytes of fru-knockdown. (H) GFP-tagged HNF4 from the endogenous Hnf4 promoter is highly expressed in oenocytes, but the GFP signal is lost in oenocytes with fru-knockdown. (I) Bodipy (green) and anti-HNF4 (magenta) stain are depicted for oenocytes dissected from oeno>Hnf4IR males raised on standard diet. (J) Bodipy stains are depicted for oenocytes of oeno>fruIR+Hnf4OE males cultured on standard diet.

The hepatocyte-like oenocytes accumulate lipid droplets (LDs) as a normal response to fasting and this readout of steatosis also indicates abnormal lipid metabolism in fed flies (17, 45). We noticed LD accumulation in oenocytes in both starved and fed oeno>fru IR flies, suggesting that fru is required for preventing steatosis independent of nutritional status (Fig. 5C). To determine whether fru-knockdown interferes with systemic lipid homeostasis, we measured the TAG levels in oeno>fru IR male adults and found that the whole-body TAG level of these flies was 2.4-fold of the control (Fig. 5D), a result that explains why fru-knockdown males have less food requirements than control males (Fig. 2B). In addition, thin layer chromatography (TLC) of adipose tissue revealed that the TAG content, but not free fatty acids (FFA), was significantly increased when fru was depleted in oenocytes (Fig. 5E). Consistently, flies bearing fru MAGIC clones exhibited similar LDs accumulation, and fru-depletion induced steatosis could be alleviated by FruCOM overexpression in oenocytes (Fig. 5F). These results indicate that Fru functions in oenocytes to prevent steatosis and to maintain systemic lipid homeostasis.

Among the downregulated genes induced by fru-depletion, we focused on Hnf4, which has been reported to be necessary in maintaining lipid homeostasis and promoting fatty acid conversion to VLCFA and hydrophobic hydrocarbons in oenocytes (59). To determine whether HNF4 acts downstream of Fru, we first used an anti- HNF4 antibody (60) and found that the HNF4 protein level was significantly downregulated in fru-silenced oenocytes (Fig. 5G, and fig. S6A). Consistently, a HNF4 protein trap line with GFP-tagged endogenous HNF4 (61), showed loss of the GFP signal in oenocytes with fru-depletion (Fig. 5H), further suggesting that HNF4 expression is regulated by fru in oenocytes. To determine whether Hnf4 is functionally downstream of fru in oenocytes, the dsRNAs of Hnf4 (Hnf4IR) were targeted to oenocytes by oeno-Gal4. As expected, knockdown of Hnf4 in oenocytes resulted in similar steatosis, as reported previously (59), whereas HNF4 overexpression alleviated lipid accumulation induced by fru-depletion (Fig. 5I–J). Taken together, these results suggest that FruCOM regulates HNF4 expression in oenocytes to inhibit steatosis and maintain systemic lipid homeostasis.

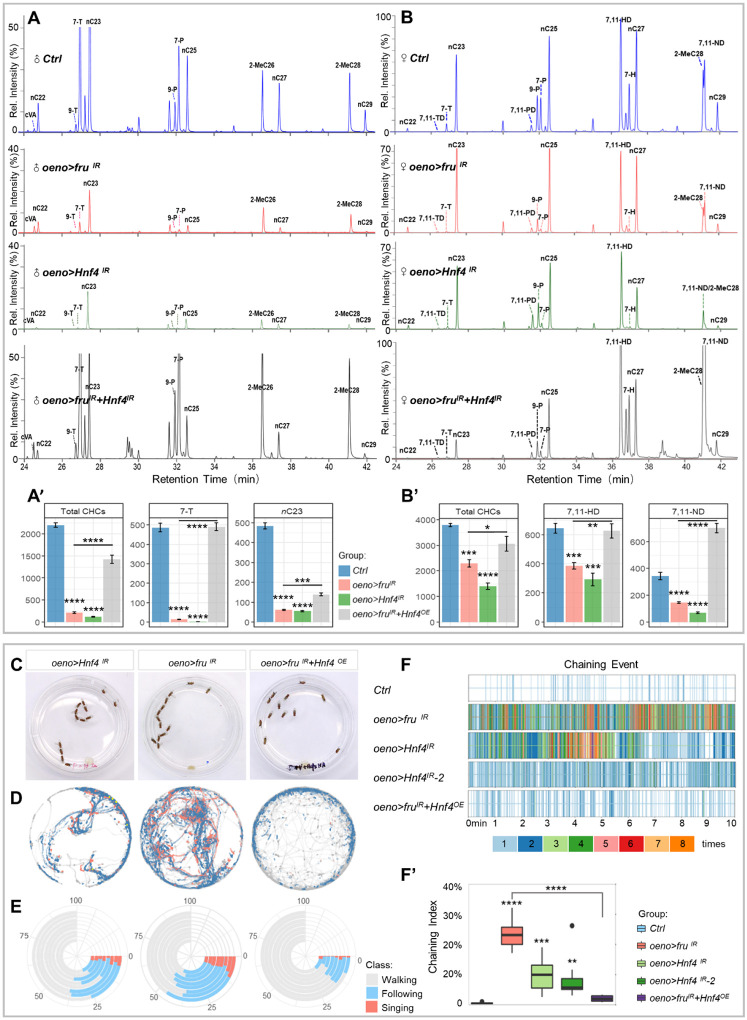

Hnf4 is essential in mediating fru-regulated CHC biosynthesis and courtship behavior.

To determine whether fru-regulated CHC production is mediated by HNF4, we used GC-MS to measure hydrocarbon levels in flies with HNF4 depletion in oenocytes (oeno>Hnf4 IR). Unsurprisingly, these flies also show significant decreases in total CHCs in both sexes (94% decrease in males and a 62% decrease in females), similar to flies with fru-knockdown in oenocytes (Fig. 6A–B). Notably, knockdown of Hnf4 also resulted in defective synthesis of sex pheromones in both sexes, including male pheromone 7-T (99% decrease), nC23 (89% decrease) and female pheromone 7,11-HD (66% decrease), 7,11-ND (80% decrease) (Fig. 6A–B). In addition, oeno>Hnf4 IR flies also showed a significant reduction of multiple long-chain n-alkanes (Fig. 6A–B), resulting in defects in the hydrophobic coating of cuticles in both male and female adults (fig. S6B). Next, we asked whether re-introducing HNF4 in oenocytes with fru-knockdown would restore the CHC profile, and found that the total CHC levels were restored to 71% and 79% of the control males and females, respectively. It is noteworthy that the major sex pheromones in both male and female flies, especially 7-T and 7,11-HD, were well recovered and comparable to the levels of the control flies (Fig. 6A–B).

Fig. 6. Fru controls HNF4 expression in the oenocytes to maintain CHC biosynthesis and innate courtship behavior.

(A) GC-MS analysis of CHCs from male adults in oeno>Hnf4IR and oeno>fruIR+Hnf4OE. (A’) The absolute contents of total hydrocarbons, male key pheromones (7-T and nC23) carried by a single male were calculated by the loading of internal standards. (B) GC-MS analysis of CHCs from female adults of controls (oeno-Gal4/+), oeno>fruIR, oeno>Hnf4IR and oeno>fruIR+Hnf4OE females. (B’) The absolute contents of total hydrocarbons, female key pheromones (7,11-HD and 7,11-ND) carried by a single female were calculated by the loading of internal standards. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. P values are calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons. Asterisks illustrate statistically significant differences between conditions. n.s., not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. (C) Representative movie screenshots of fly groups with indicated genotypes. 13 male adults of the same genotype were collected and placed in one chamber. (D) Event maps generated from representative movies of indicated genotypes (1.5-min movie per map). (E) Polarized bar plots illustrating the ratio of each detected behavior. Each bar plot was produced from 8 independent biological replicates (10-min movie per replicate). (F) Rug plots showing the chaining events detected from 10-min movies. X axis refers to the time of movie. Each vertical line with different color indicates the number of chaining events detected in a single frame. The corresponding color to the number of events is illustrated in the legend. (F’) The box plots of chaining index are quantitative statistics of 8 independent biological replicates.

The impairment of CHC biosynthesis suggests that flies with Hnf4-knockdown in oenocytes may also have changed courtship-behavior patterns. To test this, we applied the MAFDA platform to analyze the courtship behavior of male flies with oenocyte Hnf4-knockdown using two independent Hnf4-RNAi lines. As expected, these flies exhibited pervasive male-male courtship and chaining behaviors, similar to fru-depleted males (Fig. 6C–F, and fig. S6C–D and movie S4). Importantly, misexpression of HNF4 in oenocytes with fru-knockdown alleviated the male-male courtship and male-chaining phenotypes when compared with fru-knockdown alone (Fig. 6C–F, and fig. S6D and ovie S5), highly consistent with their respective CHC profiles (Fig. 6A). Together, these results suggest HNF4 is a key factor downstream of Fru in oenocytes to control pheromone and CHC production and its downregulation is accountable for the behavior phenotypes displayed by oeno>fru IR flies.

dsx- and fru-depletion induce two distinct sex-dimorphic CHC profiles.

Although fru- or Hnf4- knockdowns in oenocytes induced significant decreases of total CHCs in both male and female flies, the changes appeared sexually dimorphic. While males showed almost complete loss of CHCs, the reduction of CHCs in females was mostly on those with a chain-length beyond C26 (Fig. 3B–C). In insects, the sexual dimorphism of CHCs could be regulated by sex determination genes, including tra and dsx (24, 62–64). Consistently, knockdown of dsx in oenocytes caused male-chaining behavior (Fig. 7A). To test whether fru acts downstream of dsx in oenocytes, we first performed immunohistochemistry analyses using anti-HNF4 and anti-FruCOM antibodies and found that the protein levels of HNF4 and FruCOM were not changed in oenocytes with dsx-knockdown (Fig. 7B). Further CHC profiling revealed that oenocyte-specific depletion of dsx led to a 26% increase in total CHCs in males but a 19% decrease in females (Fig. 7C–D). Consistent with these findings, oeno>dsx IR male flies showed better water repellency than controls, whereas females had impaired hydrophobic coating of the cuticle (Fig. 7A–B). And at the pheromone level, dsx-loss in oenocytes caused feminization of the pheromone profile in male flies and masculinization of the pheromone profile in females (Fig. 7C–D). These findings reveal that despite the phenotypic similarity in courtship behavior between dsx- and fru-deleted flies, the underlying mechanism of these two genes in regulating CHC and pheromone profiles is different (Fig. 7C–D). The mechanism underlying the sex differences of CHC profile in fru and Hnf4 depleted flies is yet to be determined. Nonetheless, our results suggest that fru is not a downstream target of dsx in regulating CHC biosynthesis in oenocytes.

Fig. 7. Fru does not act downstream of Dsx in regulating CHC biosynthesis.

(A) Silencing of of dsx in oenocytes causes male chaining behavior. (B) Immunostaining shows that FruCOM and HNF4 protein levels remain high in oenocytes with dsx-knockdown. (C) CHCs from males of each genotype were analyzed using GC-MS. oeno>fruIR males exhibit significantly lower levels of CHCs in the full spectrum than the controls. The CHCs of oeno>dsxIR males, in contrast, exhibit a mixture of low-levels of characteristic male hydrocarbons (7-T) and high-levels of diene hydrocarbons (7,11-HD and 7,11-ND, characteristic of females). (D) GC-MS analysis of CHCs in female adults shows that oenocyte-specific knockdown (oeno>fruIR) resulted in lower levels of CHCs in the full spectrum than control females. However, knockdown of dsx in female oenocytes (oeno>dsxIR) resulted in lower female pheromones (diene hydrocarbons 7,11-HD and 7,11-ND) but high levels of male pheromone (7-T). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. P values are calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons. Asterisks illustrate statistically significant differences between conditions. n.s., not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Discussion

This study reveals a combined control of pheromone production and perception by a zinc-finger transcription factor gene, fru, which regulates lipid homeostasis through an evolutionarily conserved gene Hnf4, thereby promoting the robustness and efficiency of courtship behavior in Drosophila. Such an integrated regulation of sexual attractiveness and sexual perception/execution by a single gene in distinct cells may have reproductive advantage, as the recruitment of fru in certain insect species (65) could enhance both the emission and perception of sex-related cues simultaneously, which has stronger selective advantage than separate evolvement of each process (Fig.8).

Fig. 8. Model of fruitless regulates pheromone biosynthesis and perception.

A schematic drawing to show that Fru regulates both pheromone production and perception through different isoforms (the male-specific FruM and the non-sex-specific FruCOM) expressed in different organs, thereby promoting the robustness and efficiency of courtship behavior. FruCOM expression in oenocytes regulates HNF4 protein levels for the biosynthesis of sex pheromones, along with other cuticle hydrocarbons required for desiccation resistance.

The fru gene locus contains a complex transcription unit with multiple promoters and alternative splicing isoforms (Fig. 4A). fru P1 transcripts have only been detected in the nervous system, their sex-specific protein product FruM is expressed in ~2000 neurons to masculinize their structure and function (66). In contrast, FruCOM is expressed in both neural and non-neural tissues. Its expression has been detected in neuroblasts in both male and female larval CNS (41). FruCOM appears to be also required in adult female brain to regulate female rejection behavior (67). Outside the nervous system, FruCOM is detected in specific cell types in the reproductive system (66, 68), and is necessary for the maintenance of germline stem cells and cyst stem cells in male gonads (40). Our study shows that in pheromone-producing oenocytes, FruCOM, rather than FruM, is expressed in both sexes and plays a key role in CHC biosynthesis (Fig. 4C). Although how the sex- and tissue-dynamic expression of FruM and FruCOM is orchestrated remains to be resolved, the utilization of different transcriptional/splicing products of the same gene in pheromone production and perception may provide a potential advantage in coordinating these two related biological processes during development.

In insect, pheromone synthesis has coevolved with chemosensory perception. Numerous examples of correlated evolutionary changes between pheromone production and perception have been reported, with evolutionary pros and cons of sex-specific pheromones mirroring their sensory responses (69, 70). The genetic mechanisms that control pheromone perception is best understood in Drosophila with >150 chemoreceptor proteins identified (11). The odorant receptor neurons (ORNs) that express ORs are specialized to detect most volatile chemicals, including low volatility pheromones (71). In Or47b ORNs, fru has been shown to regulate sensory plasticity and act as a downstream genomic coincidence detector (72–75). Although it is unclear whether Hnf4 is regulated by fru in the nervous system, neuronal function of Hnf4 has been reported during neural stem cell differentiation and in the aging brain for β-oxidation of fatty acids (76, 77). Impaired lipid homeostasis has been shown to be associated with disrupted neuronal integrity in human neurodegenerative diseases (78). It will be interesting to find out whether lipid homeostasis regulated by Hnf4 is an integral part of the fru-regulated neural network in pheromone detection.

Insect CHCs and pheromones undergo rapid evolution and show sexual dimorphism. In Drosophila melanogaster, manipulations of sex-determination genes such as sxl, dsx or tra lead to changed CHC profiles (79–83). Mutations or ectopic expressions of dsx or tra induces either masculinization or feminization of CHC profiles, with the major changes at sex-specific pheromones (Fig. 7B–C) (79, 83). Our study revealed a novel sex-dimorphic CHC profile resulted from fru- or Hnf4-depletion in oenocytes (Fig. 3B–C, Fig. 6A–B), which differs substantially from sxl-, dsx- or tra-dependent sexual dimorphism of the CHC profile (64) (Fig. 7C–D). The male flies with fru- or Hnf4-knockdown show an almost complete loss of all CHCs, but female flies with fru- or Hnf4-knockdown have changes primarily in CHCs with the chain length > C26, which include the female pheromones 7,11-HD and 7,11-ND (Fig. 3C). The more severe changes of the male CHCs are consistent with the previous report that male CHCs change more rapidly during lab-induced natural and sexual selection in D. simulans (84). The sex dimorphic CHC patterns regulated by dsx or tra appear to stem from their regulation of DesatF and EloF expression, respectively (24), which promote female long-chain hydrocarbon biosynthesis (Fig. 7C) (25, 26). In contrast, male flies withs fru or Hnf4 knockdown have significantly reduced pheromones, and their behavioral phenotype is consistent with a previous report that wildtype males exhibit a higher preference on males without CHCs (similar to the oeno>fruIR generated in this study) over wild-type females (45). Furthermore, as we did not see changes in FruCOM or HNF4 expression when dsx was knocked down in oenoctyes, dsx and fru/Hnf4 likely target different downstream genes CHC and pheromone biosynthesis (Fig. 7A).

The sexual differences in hormone homeostasis may contribute to the novel sexual dimorphic CHC profiles induced by fru- and Hnf4-knockdown. CHCs need to be replenished after each molt, a process induced by pulses of ecdysteroid hormones (ecdysone). They are first stored internally before molting and subsequently transferred to the cuticular surface (23). It has been postulated that CHC biosynthesis is regulated by an interplay of ecdysone and juvenile hormone (JH) (85, 86). As fru have been shown to be subject to ecdysone and JH regulation (74, 87–89), and the expression of HNF4 is in response to hormonal pulses in a variety of insects (90, 91), fru and hnf4 may integrate the sex-dimorphic hormonal signals to regulate CHC biosynthesis.

Materials and Methods

Fly strains and genetics

Flies were maintained at 25 °C, 60% relative humidity, and 12-h light/dark cycle. Adults and larvae were reared on a standard cornmeal and yeast-based diet, unless otherwise noted. The Gal4/UAS driven RNAi crosses were cultured at 25°C until eclosion, and then incubated at 29°C for 7 days, and the same culture conditions were also used for the control group.

promE-Gal4 and promE-GS-Gal4 (oeno-specific GAL4) were obtained from Dr. H. Bai(92). UAS-fruMA and UAS-fruCOMB were from Dr. M. Arbeitman. elav-Gal4 (BDSC#6920), UAS-fruRNAi (BDSC#31593), UAS-GFP (BDSC#5413), fru-NP21-Gal4 (BDSC# 30027), fru-P1-Gal4 (BDSC#66696), Hnf4::GFP.FLAG (BDSC#38649), UAS-Hnf4RNAi (BDSC#29375), UAS-Hnf4RNAi (BDSC#64988), UAS-dsxRNAi (BDSC#55646), Act5C-GAL4 (BDSC#4414) and W1118 (BDSC#5905) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. UAS-fru-gRNA (VDRC#342548), UAS-fruRNAi (VDRC#330035), UAS-fruRNAi (VDRC#105005) were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Center. UAS-Hnf4::HA (F000144) was obtained from FlyORF (Zurich ORFeome Project).

RU486 (mifepristone, Fisher Scientific) was dissolved in 95% ethanol, and added to standard food at a final concentration of 100 μM for all the experiments. For activation of the GeneSwitch (GS) Gal4 driver, flies were fed on RU486 food for 7 consecutive days, unless otherwise noted.

To temporally induce fru MAGIC clones, early 3rd instar larvae of w; UAS-frug-RNA/Act5C-Gal4; HS-Cas9/+ were heat shocked for 30min at 37°C, and examined at day-7 after eclosion. The HS-Cas9 stock was kindly provided by Dr. C. Han(42).

Behavioral Assays

For the single-pair courtship assay, a tester male and a target fly (both at day-7 after eclosion) were gently aspirated into a round two-layer chamber (diameter: 1 cm; height: 3 mm per layer) to allow courtship test. Courtship index (CI), the percentage of observed time a fly performing any courtship step, was used to measure courtship between the tester male and the target fly. Each test was performed for 1 hr. For male chaining assay, the tester males were loaded into large round chambers (diameter: 4 cm; height: 3 mm) by cold anesthesia. Chaining index, which is the percentage of observed time during which at least three flies engaged in a courtship, was used to measure the courtship behavior in groups of 13 males.

For the two-choice courtship assay, a standard courtship assay was used to test male preference (i.e., female attractiveness) between fru knockdown (oeno>fru IR) and the control (oeno-Gal4/+) females. Assays were performed under both normal and dark conditions. For each measurement, two subject females for comparison were decapitated and placed on the opposite sides of a single well in a standard 12-well cell culture plate containing standard fly medium, and a 5–7-day old w1118 virgin male was subsequently aspirated into the cell. The videorecording lasted for one hour to record the courtship behaviors (including orientation, wing vibration and attempted copulation) of the male fly directed toward each female. The assays were conducted at 25°C at night. To control for individual variability, male preference was shown as the percentage of time the w1118 male was courting the fru-knockdown female divided by the total courtship time.

For social space assay, the tester males were loaded into large round chambers (diameter: 4 cm; height: 3 mm) by cold anesthesia. Flies were allowed to acclimate for 10 min and then digital images were collected after the flies reached a stable position (up to 20 min). Digital images were imported in Yolov5 and an automated measure of the nearest neighbor to each fly was determined using our own MAFDA system.

For food intake assay, the tester males were analyzed using a horizontal circular chamber (diameter: 4 cm; height: 3 mm). Flies were allowed to acclimate for 10 min and then digital images were collected after the flies reached a stable position (up to 20 min). Digital images were imported in Yolov5, the location of food was given manually, using our own MAFDA system to determine the number of foraging for each fly through its distribution and dwell time.

Development of machine-learning-based automatic fly-behavioral detection and annotation (MAFDA) system

The tracking algorithm was achieved by sorting the nearest position of fly between adjacent frames. Each fly is identified and assigned a specific ID by the system in the first frame. Subsequently, the position of each fly in the next frame is paired with the nearest neighbor in the previous frame, and inherits its ID. In the event that a target fly is lost, the fly ID remains at the position of the previous frame until a target reappears. ID-switch is identified manually. A GUI software based on Python-3.8 (Kivy-2.00) was developed to correct the IDs after ID-switching.

Yolov5 was chosen as the platform to train the data with 800 well-annotated pictures. After argumentation (flip, merge, rotate, brighten, flip, and random-salt mask), we obtained over ~140,000 labeled flies, ~130,000 labeled heads, and collected ~ 40,000 chasing events, ~8,700 wing-expansion, and ~1600 mountings. We used the Loni server to train the data with default hyperparameters with yolov5x.pt as the initial weight. The model was trained with parameters (500 epochs, 80 batch-size and 640*640 pixel) in Tesla-V100 for over a day. Chaining events are identified through 2 or more independent chase events based on a shared chasing target.

To generate an event map of fly behaviors in real-time using the MAFDA system, each fly in each frame (30 frames per second) is marked as a dot and the frames are overlayed. Different behavioral events are marked by different colored dots. To avoid over-representation, event maps are generated with 1.5-min movies to exhibit trajectories and behavioral classifications of flies in a given group.

The behavior indexes (including chasing index, singing index and chaining index) are calculated with the detected behavior events divided by the maximum possible value for that event to occur. Index = B(d)/B(max) ×100%. Chasing and singing B(max) equate fly number (N), and chaining B(max) equates N-1. For example, 10 flies in a group could have max chasing events of 10 when they form a ring and the index is 100%. When only 5 chasing-pairs are detected in a 10-fly group, the index is 50%.

Cuticular hydrocarbon analysis

Virgin male and female flies were collected at emergence and cultured at 29°C for 7 days. Each sample (including 10 flies) was frozen at −20°C for 15 min, and then introduced to a 2 ml vial containing 100 μl hexane (Thermo Scientific) with n-C19 alkanes (10 ng/μl, MilliporeSigma) as an internal standard. After extraction for 5 min, 1 μl solution was injected into a GC (Trace 1310, Thermo Scientific) in splitless mode equipped with a TG-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Thermo Scientific), using helium as carrier gas (1.0 ml/min). Column temperature was programmed to increase from 90°C to 150°C at 20°C/min and then to 300°C at 3°C/min. The GC was coupled with a MS (ISQ 7000, Thermo Scientific). Injection temperature was 280°C, MS source temperature was 310°C, and transfer line was 300°C. The MS was set to scan a mass range from 40 to 550. Standard mixture of n-alkanes (C7 to C40, MilliporeSigma) was injected following the same temperature program. The identity of 7(Z)-tricosene, 11-cis vaccenyl acetate and 7(Z), 11(Z)-heptacosadiene was confirmed by comparison of retention times and mass spectra with synthetic standards (Cayman Chemical, Cat# 9000313, 10010101 and 10012567, respectively). Other compounds were tentatively identified based on electron ionization mass spectra and Kovats indices, as well as previously published data in Drosophila(93, 94). The quantities of CHCs were calculated based on peak areas in comparison with the internal standard. For each analysis, five biological replicates and two technical replicates were conducted.

RNA-seq and data analysis

Adult oenocytes were carefully dissected in 1 × PBS before RNA extraction. Total RNAs were extracted from 7-day-old adult oenocytes using the Zymo RNA preparation kit. Two replicates were collected for each genotype. NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module and NEBNext Ultra II RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina were used for library preparation. The libraries were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 system, obtaining 40 million reads for each sample. Raw reads were aligned to the Drosophila melanogaster reference genome (95). Feature Counts and DESeq2 were then used to assign gene identity to genomic features, and to analyze fold change (log2(FC)) from count data.

cDNA Synthesis and RT-qPCR

Reverse transcription was performed on 0.25–1μg total RNA using the Superscript Reverse Transcriptase II from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Cat# 18064022) and oligo(dT) primers. cDNA was used as a template for qPCR.

qPCR was performed with a Quantstudio-3 Real-Time PCR System and PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Two independent biological replicates were performed with three technical replicates each. The mRNA abundance of each candidate gene was normalized to the expression of Rp49 by the comparative CT methods. Primer sequences are listed in Fig.S7C.

Generation of anti-FruCOM antibody (anti-FruALL)

The rabbit polyclonal antibody against FruCOM was generated by ABclonal (Wuhan, China). In brief, the fragment of the fru gene encoding 89 amino acids from the common part of the polypeptide, RERERERERERDRDRELSTTPVEQLSSSKRRRKNSSSNCDNSLSSSHQDR HYPQDSQANFKSSPVPKTGGSTSESEDAGGRHDSPLSMT, was cloned into the expression vector pET-28a (Sigma-Aldrich, #69864). A SUMO-tagged FruCOM fusion antigen was synthesized from bacteria, purified, and used to immunize the rabbit. The anti-FruCOM antibody was affinity purified. This polyclonal antibody recognizing an epitope in exon C3 of fru, which is present in both FruCOM and FruM isoforms.

Immunostaining and Confocal Imaging

Tissue samples were dissected in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), then fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes. After washing with PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBT), the samples were incubated in PBT with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight with shaking and then washed in PBT three times for 15 minutes each. The following antibodies were used in immunostaining: anti-GFP (Cell Signaling Technology, #2956S, 1:200), anti-HA (Cell Signaling Technology, #3724S, 1: 500), anti-HNF4 guinea pig polyclonal antibody (1:100, a gift from G. Storelli), anti-FruCOM rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:500) and rabbit anti-FruM polyclonal antibody (1:250) (54). The secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa 546 or 633 (Invitrogen) were diluted 1:200 and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (Invitrogen, 1:1000). After washing, samples were mounted and imaged with Zeiss LSM 800 or Zeiss LSM 980 Confocal Microscopes. Image analysis was performed in ImageJ.

TAG Assays

For TAG assays, 8 whole adult or 20 adipose tissues were homogenized in 100 μl PBS, 0.5% Tween 20 and immediately incubated at 70°C for 5 min. Heat-treated homogenate (20 μl) was incubated with either 20 μl PBS or Triglyceride Reagent (Sigma T2449–10ML) for 30 min at 37°C, after which the samples were centrifuged at maximum speed for 3 min. Then, 30 μl was transferred to a 96-well plate and incubated with 100 μl of Free Glycerol Reagent (Sigma F6428–40ML) for 5 min at 37°C. Samples were assayed using a BioTek Synergy HT microplate spectrophotometer at 540 nm. TAG amounts were determined by subtracting the amount of free glycerol in the PBS-treated sample from the total glycerol present in the sample treated with Triglyceride reagent. TAG levels were normalized to protein amounts in each homogenate using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), and data were analyzed using a student’s t test. Independent experiments were performed 2–3 times.

Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC)

Homogenize 20 adult flies’ adipose tissue in 2:1:0.8 of methanol:chloroform:water and further using 1.4 mm ceramic beads by vigorous vortexing for 10 min at 4°C. Samples were incubated in a 37°C, water bath for 1 hour. Chloroform and 1M KCl (1:1) were added to the sample, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 2 min, and the bottom layer containing lipids was aspirated using a syringe. Lipids were dried using argon gas and resuspended in chloroform (100 ul of chloroform/7mg of fly weight). Extracted lipids alongside serially diluted standard neutral lipids of known concentrations were separated on TLC plates using hexane:diethylether:acetic acid solvent (80:20:1). TLC plate was air dried for 10 min, spray stained with 3% copper (II) acetate in 8% phosphoric acid and incubated at 180°C in the oven for 10 min to allow bands to develop for scanning and imaging.

Starvation

Polystyrene vials (Genesee Scientific Cat# 32-110) were half filled with water and a dense weave cellulose acetate stopper (Genesee Scientific Cat# 49-101) was pushed to the bottom of the vial allowing saturation of this artificial substrate with water. Excess water was discarded and newly emerged flies were transferred to these vials at a density of 5–10 males per vial. Vials were sealed with a second dense weave cellulose acetate stopper to reduce water evaporation. Starvation experiments were conducted at 29°C. In this case, animals were transferred daily to fresh starvation vials and collected at 6–7 days after emergence for lipid stains.

Lipid Stains

Oenocytes dissected from adults were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, rinsed in PBS, and incubated in Bodipy 493/503 (1:1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat#D3922) or NileRed (1:2000, TCI America, 7385-67-3) for 1hr at room temperature, in the dark, to stain the neutral lipid droplets. Next, the oenocytes tissues were rinsed in PBS and mounted in antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen).

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism. Unpaired t-test was used for two-sample comparisons, one-way ANOVA Dunnett’s multiple comparison test and One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test were used for multiple-sample comparisons. Specific statistical approaches for each figure are indicated in the figure legend.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dr. M. Arbeitman, H. Bai, C.-Y. Lee, C. Han, Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC, USA) and the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC, Austria) for providing fly stocks; Dr. G. Storelli and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB, USA) for providing antibodies. We also thank Dr. X.-M. Yu and Dr. S. Lenhert for critical reading and helpful comments on the manuscript and members of the Deng lab for feedback and suggestions. Special thanks to A. Brown from the FSU Department of Biological Science for help with bulk RNA-seq library preparation.

Grant Support:

W.-M. Deng received funding (GM072562, CA224381, CA227789) for this work from the National Institutes of Health (https://www.nih.gov/) and the start-up fund from Tulane University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials Availability:

All data used to evaluate the conclusions are presented in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Requests for further information and additional data and materials related to this paper should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the corresponding author, Wu-Min Deng (wdeng7@tulane.edu).

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Khallaf M. A. et al. , Large-scale characterization of sex pheromone communication systems in Drosophila. Nature Communications 12, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyatt T. D., Pheromones and signature mixtures: defining species-wide signals and variable cues for identity in both invertebrates and vertebrates. Journal of Comparative Physiology A 196, 685–700 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toolson E. C., Effects of rearing temperature on cuticle permeability and epicuticular lipid composition in Drosophila pseudoobscura. Journal of Experimental Zoology 222, 249–253 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lockey K. H., Lipids of the insect cuticle: origin, composition and function. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Comparative Biochemistry 89, 595–645 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rouault J.-D., Marican C., Wicker-Thomas C., Jallon J.-M., in Drosophila melanogaster, Drosophila simulans: So Similar, So Different. (Springer, 2004), pp. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohtsu T., Kimura M. T., Katagiri C., How Drosophila species acquire cold tolerance: qualitative changes of phospholipids. European Journal of Biochemistry 252, 608–611 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann A. A., Hallas R., Sinclair C., Mitrovski P., Levels of variation in stress resistance in Drosophila among strains, local populations, and geographic regions: patterns for desiccation, starvation, cold resistance, and associated traits. Evolution 55, 1621–1630 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobb M., Jallon J.-M., Pheromones, mate recognition and courtship stimulation in the Drosophila melanogaster species sub-group. Animal Behaviour 39, 1058–1067 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coyne J. A., Crittenden A. P., Mah K., Genetics of a pheromonal difference contributing to reproductive isolation in Drosophila. Science 265, 1461–1464 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etges W. J., Ahrens M. A., Premating isolation is determined by larval-rearing substrates in cactophilic Drosophila mojavensis. V. Deep geographic variation in epicuticular hydrocarbons among isolated populations. The American Naturalist 158, 585–598 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferveur J.-F., Cuticular hydrocarbons: their evolution and roles in Drosophila pheromonal communication. Behavior genetics 35, 279–295 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyatt T. D., Pheromones and animal behaviour. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003), vol. 626. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makki R., Cinnamon E., Gould A. P., The development and functions of oenocytes. Annual review of entomology 59, 405–425 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wicker-Thomas C. et al. , Flexible origin of hydrocarbon/pheromone precursors in Drosophila melanogaster [S]. Journal of lipid research 56, 2094–2101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan Y., Zurek L., Dykstra M. J., Schal C., Hydrocarbon synthesis by enzymatically dissociated oenocytes of the abdominal integument of the German cockroach, Blattella germanica. Naturwissenschaften 90, 121–126 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung H. et al. , Characterization of Drosophila melanogaster cytochrome P450 genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106, 5731–5736 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutierrez E., Wiggins D., Fielding B., Gould A. P., Specialized hepatocyte-like cells regulate Drosophila lipid metabolism. Nature 445, 275–280 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunte A. S., Matthews K. A., Rawson R. B., Fatty acid auxotrophy in Drosophila larvae lacking SREBP. Cell metabolism 3, 439–448 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lycett G. et al. , Anopheles gambiae P450 reductase is highly expressed in oenocytes and in vivo knockdown increases permethrin susceptibility. Insect molecular biology 15, 321–327 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martins G. F. et al. , Insights into the transcriptome of oenocytes from Aedes aegypti pupae. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 106, 308–315 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parvy J.-P. et al. , Drosophila melanogaster acetyl-CoA-carboxylase sustains a fatty acid–dependent remote signal to waterproof the respiratory system. (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Huang K. et al. , RiboTag translatomic profiling of Drosophila oenocytes under aging and induced oxidative stress. BMC Genomics 20, 50 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard R. W., Blomquist G. J., Ecological, behavioral, and biochemical aspects of insect hydrocarbons. Annual review of entomology 50, 371–393 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirangi T. R., Dufour H. D., Williams T. M., Carroll S. B., Rapid evolution of sex pheromone-producing enzyme expression in Drosophila. PLoS biology 7, e1000168 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chertemps T. et al. , A female-biased expressed elongase involved in long-chain hydrocarbon biosynthesis and courtship behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 4273–4278 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chertemps T., Duportets L., Labeur C., Ueyama M., Wicker-Thomas C., A female-specific desaturase gene responsible for diene hydrocarbon biosynthesis and courtship behaviour in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol Biol 15, 465–473 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holze H., Schrader L., Buellesbach J., Advances in deciphering the genetic basis of insect cuticular hydrocarbon biosynthesis and variation. Heredity 126, 219–234 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimura K.-i., Hachiya T., Koganezawa M., Tazawa T., Yamamoto D., Fruitless and doublesex coordinate to generate male-specific neurons that can initiate courtship. Neuron 59, 759–769 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohatsu S., Koganezawa M., Yamamoto D., Female contact activates male-specific interneurons that trigger stereotypic courtship behavior in Drosophila. Neuron 69, 498–508 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rideout E. J., Billeter J.-C., Goodwin S. F., The sex-determination genes fruitless and doublesex specify a neural substrate required for courtship song. Current Biology 17, 1473–1478 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Von Philipsborn A. C. et al. , Neuronal control of Drosophila courtship song. Neuron 69, 509–522 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asahina K. et al. , Tachykinin-expressing neurons control male-specific aggressive arousal in Drosophila. Cell 156, 221–235 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishii K., Wohl M., DeSouza A., Asahina K., Sex-determining genes distinctly regulate courtship capability and target preference via sexually dimorphic neurons. Elife 9, e52701 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koganezawa M., K.-i. Kimura, D. Yamamoto, The neural circuitry that functions as a switch for courtship versus aggression in Drosophila males. Current Biology 26, 1395–1403 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen D. et al. , Genetic and neuronal mechanisms governing the sex-specific interaction between sleep and sexual behaviors in Drosophila. Nature communications 8, 1–14 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Usui-Aoki K. et al. , Formation of the male-specific muscle in female Drosophila by ectopic fruitless expression. Nature cell biology 2, 500–506 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryner L. C. et al. , Control of male sexual behavior and sexual orientation in Drosophila by the fruitless gene. Cell 87, 1079–1089 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anand A. et al. , Molecular genetic dissection of the sex-specific and vital functions of the Drosophila melanogaster sex determination gene fruitless. Genetics 158, 1569–1595 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song H.-J. et al. , The fruitless gene is required for the proper formation of axonal tracts in the embryonic central nervous system of Drosophila. Genetics 162, 1703–1724 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou H., Whitworth C., Pozmanter C., Neville M. C., Van Doren M., Doublesex regulates fruitless expression to promote sexual dimorphism of the gonad stem cell niche. PLoS Genet 17, e1009468 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato K., Yamamoto D., Mutually exclusive expression of sex-specific and non-sex-specific fruitless gene products in the Drosophila central nervous system. Gene Expression Patterns 43, 119232 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen S. E. et al. , Versatile CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mosaic analysis by gRNA-induced crossing-over for unmodified genomes. PLoS biology 19, e3001061 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gill K. S., A mutation causing abnormal courtship and mating behavior in males of Drosophila melanogaster. Am. Zool. 3, 507 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villella A. et al. , Extended reproductive roles of the fruitless gene in Drosophila melanogaster revealed by behavioral analysis of new fru mutants. Genetics 147, 1107–1130 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Billeter J.-C., Atallah J., Krupp J. J., Millar J. G., Levine J. D., Specialized cells tag sexual and species identity in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 461, 987–991 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amrein H., Pheromone perception and behavior in Drosophila. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 14, 435–442 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mogilner A., Edelstein-Keshet L., Bent L., Spiros A., Mutual interactions, potentials, and individual distance in a social aggregation. Journal of Mathematical Biology 47, 353–389 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Greenspan R. J., Ferveur J.-F., Courtship in drosophila. Annual review of genetics 34, 205–232 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lacaille F. et al. , An inhibitory sex pheromone tastes bitter for Drosophila males. PloS one 2, e661 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snellings Y. et al. , The role of cuticular hydrocarbons in mate recognition in Drosophila suzukii. Scientific Reports 8, 4996 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jallon J. M., David J. R., Variations in cuticular hydrocarbons among the eight species of the Drosophila melanogaster subgroup. Evolution 41, 294–302 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qiu Y. et al. , An insect-specific P450 oxidative decarbonylase for cuticular hydrocarbon biosynthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 14858–14863 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Billeter J.-C. et al. , Isoform-specific control of male neuronal differentiation and behavior in Drosophila by the fruitless gene. Current Biology 16, 1063–1076 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J. et al. , fruitless tunes functional flexibility of courtship circuitry during development. eLife 10, e59224 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stockinger P., Kvitsiani D., Rotkopf S., Tirián L., Dickson B. J., Neural Circuitry that Governs Drosophila Male Courtship Behavior. Cell 121, 795–807 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kimura K.-I., Ote M., Tazawa T., Yamamoto D., Fruitless specifies sexually dimorphic neural circuitry in the Drosophila brain. Nature 438, 229–233 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blomquist G. J., Bagnères A.-G., Insect hydrocarbons: biology, biochemistry, and chemical ecology. (Cambridge University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cinnamon E. et al. , Drosophila Spidey/Kar regulates oenocyte growth via PI3-kinase signaling. PLoS Genetics 12, e1006154 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Storelli G., Nam H.-J., Simcox J., Villanueva C. J., Thummel C. S., Drosophila HNF4 Directs a Switch in Lipid Metabolism that Supports the Transition to Adulthood. Developmental Cell 48, 200–214.e206 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palanker L., Tennessen J. M., Lam G., Thummel C. S., Drosophila HNF4 regulates lipid mobilization and β-oxidation. Cell metabolism 9, 228–239 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palu R. A., Thummel C. S., Sir2 Acts through Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4 to maintain insulin Signaling and Metabolic Homeostasis in Drosophila. PLoS Genet 12, e1005978 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pei X.-J. et al. , Modulation of fatty acid elongation in cockroaches sustains sexually dimorphic hydrocarbons and female attractiveness. PLoS biology 19, e3001330 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen N. et al. , A single gene integrates sex and hormone regulators into sexual attractiveness. Nature Ecology & Evolution, (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fernández M. d. l. P. et al. , Pheromonal and behavioral cues trigger male-to-female aggression in Drosophila. PLoS biology 8, e1000541 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parker D. J., Gardiner A., Neville M. C., Ritchie M. G., Goodwin S. F., The evolution of novelty in conserved genes; evidence of positive selection in the Drosophila fruitless gene is localised to alternatively spliced exons. Heredity 112, 300–306 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dornan A. J., Gailey D. A., Goodwin S. F., GAL4 enhancer trap targeting of the Drosophila sex determination gene fruitless. genesis 42, 236–246 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chowdhury T., Calhoun R. M., Bruch K., Moehring A. J., The fruitless gene affects female receptivity and species isolation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 287, 20192765 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee G. et al. , Spatial, temporal, and sexually dimorphic expression patterns of the fruitless gene in the Drosophila central nervous system. Journal of neurobiology 43, 404–426 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ng S. H. et al. , Pheromone evolution and sexual behavior in Drosophila are shaped by male sensory exploitation of other males. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 3056–3061 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dekker T. et al. , Loss of Drosophila pheromone reverses its role in sexual communication in Drosophila suzukii. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282, 20143018 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Joseph R. M., Carlson J. R., Drosophila Chemoreceptors: A Molecular Interface Between the Chemical World and the Brain. Trends Genet 31, 683–695 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Manoli D. S. et al. , Male-specific fruitless specifies the neural substrates of Drosophila courtship behaviour. Nature 436, 395–400 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodrigues V., Hummel T., Development of the Drosophila olfactory system. Adv Exp Med Biol 628, 82–101 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sethi S. et al. , Social Context Enhances Hormonal Modulation of Pheromone Detection in Drosophila. Current Biology 29, 3887–3898.e3884 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang Y., Ng R., Neville M. C., Goodwin S. F., Su C.-Y., Distinct Roles and Synergistic Function of FruM Isoforms in Drosophila Olfactory Receptor Neurons. Cell Reports 33, 108516 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang J. et al. , Regulation of Neural Stem Cell Differentiation by Transcription Factors HNF4–1 and MAZ-1. Molecular Neurobiology 47, 228–240 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Laranjeira A., Schulz J., Dotti C. G., Genes related to fatty acid β-oxidation play a role in the functional decline of the drosophila brain with age. PLoS One 11, e0161143 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lessing D., Bonini N. M., Maintaining the brain: insight into human neurodegeneration from Drosophila melanogaster mutants. Nature Reviews Genetics 10, 359–370 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jallon J.-M., Lauge G., Orssaud L., Antony C., Female pheromones in Drosophila melanogaster are controlled by the doublesex locus. Genetics Research 51, 17–22 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tompkins L., McRobert S. P., Behavioral and pheromonal phenotypes associated with expression of loss-of-function mutations in the Sex-lethal gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of neurogenetics 9, 219–226 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tompkins L., McRobert S., Regulation of behavioral and pheromonal aspects of sex determination in Drosophila melanogaster by the Sex-lethal gene. Genetics 123, 535–541 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Waterbury J. A., Jackson L. L., Schedl P., Analysis of the doublesex female protein in Drosophila melanogaster: role in sexual differentiation and behavior and dependence on intersex. Genetics 152, 1653–1667 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ferveur J.-F. et al. , Genetic feminization of pheromones and its behavioral consequences in Drosophila males. Science 276, 1555–1558 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sharma M. D., Hunt J., Hosken D. J., Antagonistic responses to natural and sexual selection and the sex-specific evolution of cuticular hydrocarbons in Drosophila simulans. Evolution: International Journal of Organic Evolution 66, 665–677 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wicker C., Jallon J.-M., Influence of ovary and ecdysteroids on pheromone biosynthesis in Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera: Drosophilidae). European Journal of Entomology 92, 197–197 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bilen J., Atallah J., Azanchi R., Levine J. D., Riddiford L. M., Regulation of onset of female mating and sex pheromone production by juvenile hormone in Drosophila melanogaster. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, 18321–18326 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dalton J. E., Lebo M. S., Sanders L. E., Sun F., Arbeitman M. N., Ecdysone Receptor Acts in fruitless- Expressing Neurons to Mediate Drosophila Courtship Behaviors. Current Biology 19, 1447–1452 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang B., Sato K., Yamamoto D., Ecdysone signaling regulates specification of neurons with a male-specific neurite in Drosophila. Biology open 7, bio029744 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhao S. et al. , Chromatin-based reprogramming of a courtship regulator by concurrent pheromone perception and hormone signaling. Science Advances 6, eaba6913 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang X. et al. , Hormone and receptor interplay in the regulation of mosquito lipid metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, E2709–E2718 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sullivan A. A., Thummel C. S., Temporal profiles of nuclear receptor gene expression reveal coordinate transcriptional responses during Drosophila development. Molecular Endocrinology 17, 2125–2137 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huang K. et al. , Impaired peroxisomal import in Drosophila oenocytes causes cardiac dysfunction by inducing upd3 as a peroxikine. Nature Communications 11, 2943 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dweck H. K. M. et al. , Pheromones mediating copulation and attraction in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, E2829–E2835 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Everaerts C., Farine J.-P., Cobb M., Ferveur J.-F., Drosophila cuticular hydrocarbons revisited: mating status alters cuticular profiles. PloS one 5, e9607 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.dos Santos G. et al. , FlyBase: introduction of the Drosophila melanogaster Release 6 reference genome assembly and large-scale migration of genome annotations. Nucleic Acids Research 43, D690–D697 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used to evaluate the conclusions are presented in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Requests for further information and additional data and materials related to this paper should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the corresponding author, Wu-Min Deng (wdeng7@tulane.edu).