Abstract

Purpose

To determine if suicide attempts increased during the first year of the pandemic among young adolescents in Quebec, Canada.

Methods

We analyzed children aged 10–14 years who were hospitalized for a suicide attempt between January 2000 and March 2021. We calculated age-specific and sex-specific suicide attempt rates and the proportion of hospitalizations for suicide attempts before and during the pandemic and compared rates with patients aged 15–19 years. We used interrupted time series regression to measure changes in rates during the first (March 2020 to August 2020) and second (September 2020 to March 2021) waves and difference-in-difference analysis to determine if the pandemic had a greater impact on girls than boys.

Results

Suicide attempt rates decreased for children aged 10–14 years during the first wave. However, rates increased sharply during the second wave for girls, without changing for boys. Girls aged 10–14 years had an excess of 5.1 suicide attempts per 10,000 at the start of wave 2, with rates continuing to increase by 0.6 per 10,000 every month thereafter. Compared with the prepandemic period, the increase in the proportion of girls aged 10–14 years hospitalized for a suicide attempt was 2.2% greater than that of boys during wave 2. The pattern seen in girls aged 10–14 years was not present in girls aged 15–19 years.

Discussion

Hospitalizations for suicide attempts among girls aged 10–14 years increased considerably during the second wave of the pandemic, compared with boys and older girls. Young adolescent girls may benefit from screening and targeted interventions to address suicidal behavior.

Keywords: Adolescent, Attempted suicide, COVID-19, Pandemics, Self-injurious behavior

Implications and Contribution.

Hospitalization rates for suicide attempts increased considerably among girls aged 10–14 years during the second wave of the pandemic in Quebec, Canada. There was no change in older girls or boys. The impact of the pandemic on young girls may have been missed in current studies.

A growing number of studies suggest that children aged 10–14 years had considerable mental health concerns during the pandemic, especially girls [1,2]. Lockdowns led to social isolation and limited contact with peers, and may have had a greater impact on young adolescent girls who are vulnerable to stress [3]. School closures and loss of extracurricular services during the pandemic made it difficult to address mental health needs [4]. Yet, studies have not quantified the impact of the pandemic on suicide attempts in girls aged 10–14 years. Most reports focus on older adolescents or adolescents overall, providing only mixed evidence for an increase in suicide attempts [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. Data from the United States, Spain, and Mexico indicate that suicide attempts increased in adolescent girls under 20 years but not boys the same age [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. In contrast, a survey of Korean adolescents aged 12–18 years reported a decrease in suicide attempts for both girls and boys [9]. A Canadian study found that the pandemic was associated with a lower risk of self-harm in girls aged 14–24 years, but younger adolescents were not examined [10]. Moreover, some of these patterns may reflect preexisting trends in suicide attempts [4,6,11].

Many countries implemented extreme measures to reduce COVID-19 transmission. Lockdowns were particularly strict in Quebec, the initial center of the pandemic in Canada [12]. Quebec used a mix of remote learning, mask mandates, and forced classroom bubbles to prohibit interaction with peers outside of immediate classmates [13]. Many of these measures disproportionately affected children aged 10–14 years [13,14]. Children were obliged to maintain classroom distancing, had assigned schoolyard locations during recess, and classroom-specific start and end times to ensure that no student encountered schoolmates from outside their classroom bubble at any point [13]. While these measures appear to have affected mental health [1,2], the extent to which they may have exacerbated suicidal behavior is not known. We hypothesized that suicide attempts increased in young adolescents during the pandemic, especially girls. Our objective was to determine if suicide attempt rates changed in children aged 10–14 years during the first year of the pandemic in Quebec.

Methods

We carried out a time trend analysis of hospitalization rates for suicide attempts between January 1, 2000, and March 31, 2021, among adolescents aged 10–14 years in Quebec, Canada. We used 10 years as the lower cutoff because suicide attempts were rare before this age. We included adolescents aged 15–19 years for comparison as they were affected by similar lockdown measures. We utilized the Maintenance and Use of Data for the Study of Hospital Clientele registry to extract suicide attempts in this time period. The registry comprises discharge abstracts for all hospitalizations and day surgeries in Quebec, and provides clinical administrative information compiled by trained staff. The data include self-injury codes from the International Classification of Diseases that allow us to identify suicide attempts [15]. As patients with nonsuicidal self-injuries are not admitted, they are not present in the dataset. Suicidal intent is generally required for admission [16].

Exposure

The main exposures were the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Quebec, the first wave started February 25, 2020 [14]. The first wave extended until July 11, 2020, and was followed by a six week trough from July 12, 2020, to August 22, 2020, when the number of COVID-19 hospitalizations was low. The first wave was characterized by province-wide school closures and cancellation of extracurricular activities throughout summer. The second wave extended from August 23, 2020, to March 31, 2021, the study end. In-person learning resumed in the second wave but with severe restrictions, including strict classroom bubbles and periods of remote learning. We used the prepandemic period which extended from January 1, 2000, to February 24, 2020, as the reference period.

Outcome

The outcome comprised hospitalizations for suicide attempts, identified through intentional self-harm codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th (E950-E959) and 10th Revisions (X60-X84, Y87.0). These codes capture suicide attempts by poisoning, hanging, cutting, piercing, jumping, drowning, firearm, smoke, fire, heat, motor vehicle collision, caustic substances, electrocution, and unspecified means. We categorized the method of suicide attempt as self-poisoning, violent means (hanging, cutting, piercing, and other), or unspecified [16].

Covariates

We considered characteristics that may have influenced suicide attempts, including sex, mental illness, and socioeconomic disadvantage (low, low-moderate, moderate, moderate-high, and high). We assigned socioeconomic quintiles using a neighborhood index derived from average household income, education, and employment levels [17]. Mental illness included comorbid schizophrenia, depression, bipolar, anxiety, personality, and eating disorders.

Statistical analysis

We calculated hospitalization rates for suicide attempt by age and sex for the 6-month period before the pandemic, the first wave, and the second wave, using population estimates from Statistics Canada for the denominator [18]. Because hospital capacity decreased during the pandemic [19,20], we also determined if the proportion of hospitalizations for suicide attempts changed over time.

We used interrupted time series regression to assess monthly suicide attempt hospitalization rates before and during the first and second waves. Interrupted time series analysis is a quasi-experimental method that measures the effect of sudden exposures on an outcome [21]. To carry out this analysis, we computed suicide attempt hospitalization rates for every month of the study, and included an interruption for each pandemic wave in the regression model. We stratified the time series by sex to determine if rates varied between girls and boys. We also assessed if the method of suicide attempt, including self-poisoning and violent means, changed during the time series. We used an autoregressive model to account for seasonal factors that could confound the associations [22].

We used difference-in-difference analysis to determine the modifying effect of sex on the proportion of adolescents admitted for a suicide attempt during the pandemic. Difference-in-difference analysis is a quasi-experimental method suitable for determining whether the pandemic had a greater impact on girls or boys [23]. To carry out this analysis, we first determined if patients had a suicide attempt before the pandemic or during wave 1. We then modeled these two time points in a log-binomial generalized estimating equation with an identity link and an interaction term between sex and time [24]. Using this model, we estimated the difference in the proportion of girls admitted for a suicide attempt in wave 1 compared with the prepandemic period, as well as the difference for boys. We also estimated the overall difference between girls and boys, or the difference-in-differences. We repeated the difference-in-difference analysis for the comparison of wave 2 with the prepandemic period.

In sensitivity analyses, we stratified the analysis by history of mental illness and socioeconomic disadvantage. We examined time trends with data restricted to the first suicide attempt. We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, N.C) for statistical analyses, and obtained an ethics waiver from our institution as we utilized anonymized data.

Results

There were 3,174 suicide attempt hospitalizations between January 1, 2000, and March 31, 2021, among adolescents aged 10–14 years, and 19,865 among adolescents aged 15–19 years. The majority of suicide attempts occurred in girls and socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents, were self-poisonings, and involved mental illness (Table 1 ). Among patients 10–14 years of age who attempted suicide, the proportion of girls increased from 75% before the pandemic to 83.1% during wave 1 and 90.9% during wave 2. In contrast, among patients 15–19 years of age, the proportion of girls decreased, especially during wave 1. The proportion of 10–14 year old adolescents with violent attempts increased, particularly during wave 1. Suicide attempts remained more common in adolescents aged 15–19 years of age both before and during the pandemic.

Table 1.

Characteristics of youth hospitalized for suicide attempts before versus during the pandemica

| Patient characteristic | No. of suicide attempt hospitalizations (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepandemic |

Wave 1 |

Wave 2 |

||||

| 10–14 years | 15–19 years | 10–14 years | 15–19 years | 10–14 years | 15–19 years | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Girls | 69 (75.0) | 287 (74.7) | 59 (83.1) | 183 (66.5) | 190 (90.9) | 334 (74.1) |

| Boys | 23 (25.0) | 97 (25.3) | 12 (16.9) | 92 (33.5) | 19 (9.1) | 117 (25.9) |

| Method of suicide attempt | ||||||

| Self-poisoning | 66 (71.7) | 296 (77.1) | 44 (62.0) | 204 (74.2) | 151 (72.2) | 324 (71.8) |

| Violent means | 26 (28.3) | 85 (22.1) | 25 (35.2) | 75 (27.3) | 59 (28.2) | 129 (28.6) |

| Hanging | 13 (14.1) | 23 (6.0) | 8 (11.3) | 16 (5.8) | 19 (9.1) | 35(7.8) |

| Cutting or piercing | 7 (7.6) | 38 (9.9) | 10 (14.1) | 38 (13.8) | 29 (13.9) | 59 (13.1) |

| Otherb | 6 (6.5) | 25 (6.5) | 8 (11.3) | 23 (8.4) | 14 (6.7) | 41 (9.1) |

| Unspecified means | 0 (0.0) | 10 (2.6) | 6 (8.5) | <5 | 10 (4.8) | 16 (3.5) |

| Mental illness | ||||||

| Yes | 60 (65.2) | 282 (73.4) | 43 (60.6) | 207 (75.3) | 155 (74.2) | 339 (75.2) |

| No | 32 (34.8) | 102 (26.6) | 28 (39.4) | 68 (24.7) | 54 (25.8) | 112 (24.8) |

| Socioeconomic disadvantage | ||||||

| Low | 7 (7.6) | 59 (15.4) | 10 (14.1) | 56 (20.4) | 22 (10.5) | 70 (15.5) |

| Low-moderate | 19 (20.7) | 63 (16.4) | 11 (15.5) | 43 (15.6) | 43 (20.6) | 83 (18.4) |

| Moderate | 23 (25.0) | 63 (16.4) | 14 (19.7) | 39 (14.2) | 42 (20.1) | 65 (14.4) |

| Moderate-high | 11 (12.0) | 55 (14.3) | 11 (15.5) | 48 (17.5) | 38 (18.2) | 91 (20.2) |

| High | 23 (25.0) | 119 (31.0) | 23 (32.4) | 72 (26.2) | 55 (26.3) | 98 (21.7) |

| Total | 92 (100.0) | 384 (100.0) | 71 (100.0) | 275 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 451 (100.0) |

Prepandemic period extends from August 23, 2019, to February 24, 2020, wave 1 from February 25,2020, to August 22, 2020, and wave 2 from August 23, 2020, to March 31, 2021.

Drowning, firearm, smoke, fire, heat, jumping, motor vehicle collision, caustic substance, and electrocution.

Hospitalization rates for suicide attempts decreased during the first wave for most groups (Table 2 ). However, rates increased during the second wave, especially for younger adolescent girls. There were 13.9 suicide attempts per 10,000 girls aged 10–14 years in wave 2 (95% CI 11.9–15.8), a rate that significantly exceeded the prepandemic rate of 6.2 per 10,000 (95% CI 4.7–7.6). In contrast, rates for girls aged 15–19 years returned to prepandemic levels in wave 2. The proportion of hospitalizations for suicide attempts increased among girls aged 10–14 years in both waves.

Table 2.

Trends in hospitalizations for suicide attempt among youth before versus during the pandemica

| Patient age | Hospitalization rate per 10,000 population (95% confidence interval)b |

Proportion of hospitalizations for suicide attempts, % (95% confidence interval)c |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prepandemic | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Prepandemic | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |

| Girls | ||||||

| All ages | 16.3 (14.6–18.0) | 11.3 (9.9–12.7) | 19.9 (18.2–21.6) | 3.9 (3.5–4.3) | 3.8 (3.3–4.3) | 5.1 (4.7–5.6) |

| 10–14 years | 6.2 (4.7–7.6) | 5.3 (4.0–6.7) | 13.9 (11.9–15.8) | 2.1 (1.6–2.6) | 2.7 (2.0–3.4) | 4.9 (4.2–5.6) |

| 15–19 years | 27.0 (23.9–30.2) | 17.8 (15.2–20.4) | 26.4 (23.6–29.3) | 5.0 (4.4–5.5) | 4.4 (3.8–5.0) | 5.3 (4.7–5.8) |

| Boys | ||||||

| All ages | 5.3 (4.3–6.2) | 4.7 (3.8–5.6) | 5.0 (4.1–5.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 1.8 (1.5–2.2) | 1.6 (1.3–1.8) |

| 10–14 years | 2.0 (1.2–2.8) | 1.0 (0.5–1.6) | 1.3 (0.7–1.9) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.5 (0.2–0.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) |

| 15–19 years | 8.7 (7.0–10.5) | 8.6 (6.8–10.3) | 8.9 (7.3–10.5) | 2.1 (1.6–2.5) | 2.9 (2.3–3.5) | 2.4 (2.0–2.9) |

Prepandemic period extends from August 23, 2019, to February 24, 2020, wave 1 from February 25, 2020, to August 22, 2020, and wave 2 from August 23, 2020, to March 31, 2021.

Number of suicide attempt hospitalizations per 10,000 population based on the Canada census.

Number of suicide attempt hospitalizations divided by total number of hospitalizations.

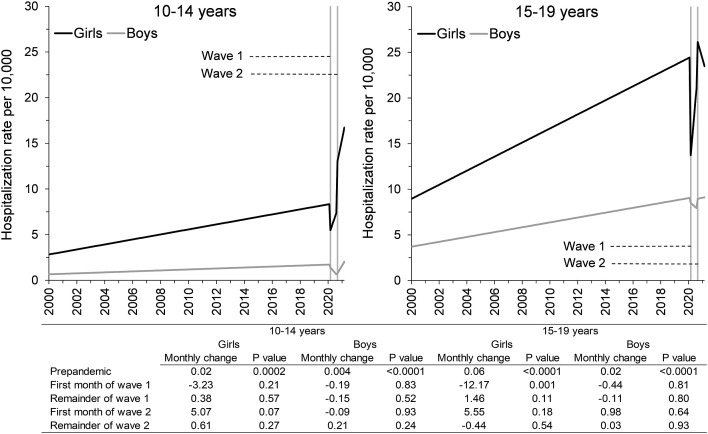

Interrupted time series analyses indicated that suicide attempt rates increased incrementally every month before the start of the pandemic, especially in girls (Figure 1 ). The pattern, however, changed during the pandemic. Among girls aged 10–14 years, rates decreased by 3.2 attempts per 10,000 the first month of wave 1. Rates then increased by 0.4 attempts per 10,000 every month during the remainder of wave 1, 5.1 attempts per 10,000 the first month of wave 2, and 0.6 attempts per 10,000 every month thereafter. Among girls aged 15–19 years, rates declined at the start of wave 1 before returning to original levels in wave 2. The pandemic had no significant impact on suicide attempts in boys.

Figure 1.

Interrupted time series of suicide attempt hospitalization rates for youth before and during the pandemica. aRates of suicide attempt hospitalizations before the pandemic (January 2000 to February 2020), during wave 1 (March 2020 to August 2020), and during wave 2 (September 2020 to March 2021). Monthly change refers to change in the suicide attempt hospitalization rate per 10,000 population.

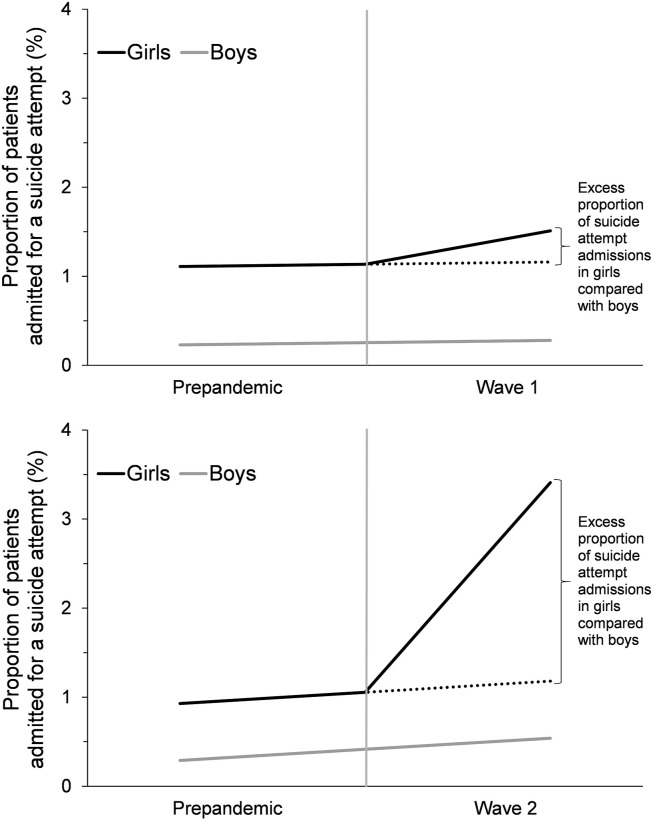

Compared with boys, the proportion of girls aged 10–14 years who were hospitalized for a suicide attempt increased disproportionately during the pandemic (Figure 2 ). Difference-in-difference analyses indicated that the proportion increased 0.4% more for girls during wave 1, compared with boys. The change was even more pronounced in the second wave, with the proportion of hospitalizations for suicide attempts increasing 2.2% more for girls compared with boys.

Figure 2.

Difference-in-difference analysis of the change in proportion of suicide attempts for girls versus boys aged 10–14 years during the pandemica. aPrepandemic period extends from August 23, 2019, to February 24, 2020, wave 1 from February 25, 2020, to August 22, 2020, and wave 2 from August 23, 2020, to March 31, 2021. Dotted line represents the expected increase in the proportion of hospitalizations for suicide attempts had girls experienced the same increase as boys.

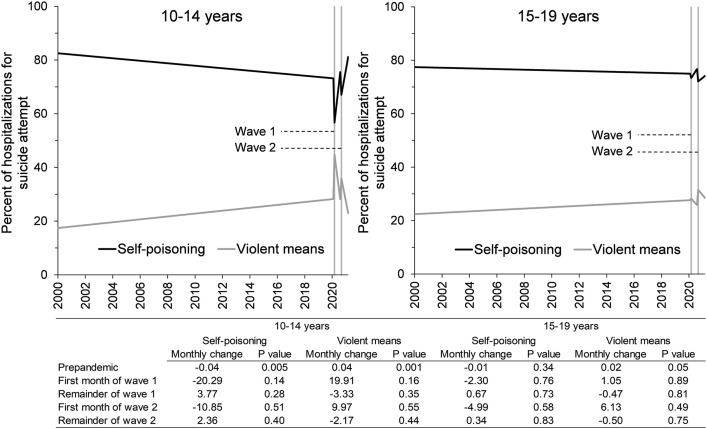

The pandemic affected the method that adolescents used for suicide attempts (Figure 3 ). Violent methods, such as hanging, cutting, and piercing, were more frequently used at the start of each wave, particularly by adolescents aged 10–14 years. The proportion of attempts by violent means in this age group increased by 19.9 percentage points the first month of wave 1 and 10.0 percentage points the first month of wave 2. In comparison, the proportion of attempts by violent means in adolescents aged 15–19 years of age increased by 1.1 percentage points the first month of wave 1 and 6.1 percentage points the first month of wave 2. The proportion of violent attempts returned to original levels towards the end of each wave for both age groups.

Figure 3.

Use of violent means for suicide attempts in youth before versus during the pandemica. aProportion of hospitalizations for suicide attempts due to self-poisoning versus violent means before the pandemic (January 2000 to February 2020), during wave 1 (March 2020 to August 2020), and during wave 2 (September 2020 to March 2021). Monthly change refers to change in the proportion of hospitalizations in percentage points.

Sensitivity analyses indicated that trends were similar for adolescents with and without mental illness up until wave 2, at which point suicide attempt rates continued to increase for adolescents with mental illness but returned to baseline for adolescents without mental illness (Figure A1). Rates dropped among the most socioeconomically advantaged adolescents at the start of wave 1, but surpassed prepandemic levels thereafter. Rates also dropped at the start of wave 1 among the most socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents, before rebounding to prepandemic levels in wave 2. Trends were similar when we analyzed only the first suicide attempt.

Discussion

In this analysis of adolescents in Quebec, Canada, hospitalization rates for suicide attempts increased in girls aged 10–14 years during the pandemic. Rates initially decreased at the start of the first wave, but rapidly rebounded and increased as the pandemic progressed. By the end of the first year, rates for girls aged 10–14 years reached levels that were markedly greater than before the pandemic. In contrast, rates in boys and older girls merely returned to prepandemic levels. The increase in the proportion of girls aged 10–14 years with suicide attempts during the second wave was 2.2% greater than the proportion of boys the same age. Adolescents aged 10–14 years were also more likely to use violent methods during the first wave. Overall, the findings suggest that the pandemic had a particularly strong impact on suicide attempt rates in young adolescent girls.

Very little is known about suicide attempt rates in youth during the pandemic. Up to now, studies have focused on older adolescents or adolescents overall, without stratifying by age [5,7,25]. In Spain, suicide attempts in girls aged 12–18 years increased by 48% the first year of the pandemic compared with the preceding year [7]. There was no increase in boys. In the United States and Australia, emergency room visits for suicide attempts and intensive care unit admissions for intentional self-harm increased among adolescent girls [5,25]. Australian data suggest that demand for child and adolescent mental health and suicide helplines increased during the pandemic, especially among girls [26]. Yet in Ontario, which shares a border with Quebec, hospitalization rates for self-harm declined in females 14–24 years [10]. Children under 14 years did not receive attention in any of these studies [5,7,10,25]. Our findings suggest that the pandemic may have had a concentrated effect on suicide attempts in girls aged 10–14 years, more than in boys or older girls. The impact in younger girls may have been missed in previous studies that focused on older adolescents [5,7,10,25].

Early adolescence coincides with physical, social, and emotional changes, especially for girls who enter puberty earlier than boys [3,27]. Early in adolescence, girls may cope with stress differently [3]. Boys may be more likely to seek distractions such as physical activity [3]. However, boys may be less likely to seek support, making it easier to miss or overlook mental health issues. Strict lockdown measures during the pandemic, including school closures and social distancing, may have increased isolation, affected the quantity and quality of peer interactions, and influenced the mental well-being of young girls [27]. Evidence suggests that young adolescent girls were more likely to internalize problems and have stress, anxiety, or depressive symptoms during the pandemic [27].

The pandemic was associated with province-wide school closures in the first wave, and use of small classroom bubbles with limits on in-person learning in the second wave [13,14]. Classroom bubbles were designed to enforce social distancing and prevent students from encountering friends while on school grounds. Children were assigned to a specific group for the duration of the year and never met other students while at school. Mask mandates were also implemented. These measures were supplemented with restrictions on contact with school personnel, who normally have a role in the promotion of mental health [13]. Combined, these measures reduced the capacity for peers and school personnel to identify children struggling with mental health, provide early prevention and support, and refer children to appropriate resources [13]. These safety nets may be more important for younger than older adolescents. Prior research has shown that school support is particularly helpful to identify young adolescents exposed to parental neglect or abuse [28].

The pandemic had almost no effect on suicide attempt hospitalizations in adolescents aged 15–19 years. Although this age group may be better at hiding distress, our findings may also reflect the likelihood that older adolescents are more mature and better able to cope. This age group is more independent and may have more freedom to find ways of seeing friends and maintaining relationships. Older adolescents are more likely to have a smartphone and access to digital platforms allowing them to videoconference or chat with friends. In contrast, children aged 10–14 years may not have access to these types of media. Although some may have a phone or other electronic device, younger adolescents may be restricted by parental controls or not as equipped to handle difficult online content and cyberbullying [29].

In our population, the methods used for suicide attempts tended to shift during the pandemic. Children aged 10–14 years of age were more likely to use violent means, especially cutting, at the start of the pandemic. Violent methods are tied to greater impulsivity and are more likely to be fatal [30]. Unfortunately, studies of methods used for suicide attempts during the pandemic are sparse. A study from Korea reported that the proportion of suicide attempts by cutting increased from 31.2% to 40.5% in adolescents ≤18 years the first year of the pandemic [31]. It is possible that lockdown measures reduced the availability or acceptability of pharmaceutical products used in self-poisonings, resulting in an increase in violent attempts. Identifying the reasons behind the increase in violent suicide attempts may help inform prevention efforts.

While socioeconomic disadvantage is a risk factor for suicidal behavior [30], our findings indicate that suicide attempt hospitalizations increased more among advantaged adolescents. The increase occurred despite job losses that disproportionately affected disadvantaged families [32]. Advantaged adolescents were more likely to have parents who worked remotely and kept their jobs. Economic stress is therefore unlikely to explain the increase in suicide attempt hospitalizations among advantaged adolescents. Rather, advantaged children may have faced fewer barriers accessing care, unlike disadvantaged children who may have found it harder to access services or obtain help. Reduction of services during the pandemic may have disproportionately affected disadvantaged populations [20]. Although Quebec provides publicly funded mental healthcare, we may not have captured all disadvantaged adolescents with suicide attempts.

It is important to note that hospitalization rates for suicide attempts started increasing among girls aged 10–14 years long before the pandemic. The pandemic appears to have affected a group of girls that was already susceptible to suicide attempts for other underlying reasons. Reducing the risk of suicide attempts during a pandemic may therefore require addressing other risk factors for suicide attempts and increasing mental health support in this age group. As wave 1 coincided with the middle of the school year and wave 2 with the beginning of a new session, school-related risk factors may be a potential target for prevention. Adolescents are known to have a greater risk of suicidal behavior during the school year [33].

This study had limitations. We analyzed suicide attempts that required hospital admission, but could not account for patients who did not seek care or were treated at an emergency department. However, suicide attempts in adolescents aged 10–14 years usually require hospitalization in Quebec. We could not examine completed suicides as most occur outside of hospital. Coding errors may have led to misclassification of variables, and attenuated the difference between groups. We lacked information on race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, nativity, and immigration as such information was not collected. We could not account for the underlying cause of the suicide attempt or family context. We did not have data on parental and peer support, victimization, and child abuse or neglect. The findings indicate that suicide attempts increased in young girls during the pandemic, but are not proof of causality. Generalizability of the findings to other regions remains to be determined.

The findings of this study suggest that young adolescent girls in Quebec were more affected by lockdown measures than older adolescents. Hospitalizations for suicide attempts increased substantially and surpassed prepandemic levels among girls aged 10–14 years. In contrast, rates in boys and older adolescent girls changed little. Moreover, young adolescents were more likely to use violent methods at the start of the pandemic. Although further research is needed to determine if adolescent suicide attempts continued to increase during the remainder of the pandemic, the findings indicate that young adolescent girls could benefit from universal mental health screening, including screening for suicidal behavior and associated risk factors, as well as interventions geared specifically towards suicide prevention. Improving mental health literacy may help reduce the stigma of mental illness and suicidal behavior and encourage vulnerable adolescents to seek help.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2023.01.019.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Quebec Population Health Research Network; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [grant number WI2-179928]; and the Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé [career award 296785]. The study sponsors had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication. N.A., A.A., and J.H.P. wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Gadermann A., Thomson K., Gill R., et al. Early adolescents’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in their well-being. Front Public Health. 2022;10:823303. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.823303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cost K.T., Crosbie J., Anagnostou E., et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31:671–684. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoon Y., Eisenstadt M., Lereya S.T., Deighton J. Gender difference in the change of adolescents’ mental health and subjective wellbeing trajectories. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s00787-022-01961-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chadi N., Ryan N.C., Geoffroy M.C. COVID-19 and the impacts on youth mental health: Emerging evidence from longitudinal studies. Can J Public Health. 2022;113:44–52. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00567-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yard E., Radhakrishnan L., Ballesteros M.F., et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12-25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, January 2019-May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:888–894. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridout K.K., Alavi M., Ridout S.J., et al. Emergency department encounters among youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:1319–1328. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gracia R., Pamias M., Mortier P., et al. Is the COVID-19 pandemic a risk factor for suicide attempts in adolescent girls? J Affect Disord. 2021;292:139–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valdez-Santiago R., Villalobos A., Arenas-Monreal L., et al. Comparison of suicide attempts among nationally representative samples of Mexican adolescents 12 months before and after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2022;298:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S.Y., Kim H.R., Park B., Choi H.G. Comparison of stress and suicide-related behaviors among Korean youths before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.36137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray J.G., Austin P.C., Aflaki K., et al. Comparison of self-harm or overdose among adolescents and young adults before vs during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.43144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheridan D.C., Grusing S., Marshall R., et al. Changes in suicidal ingestion among preadolescent children from 2000 to 2020. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:604–606. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron-Blake E., Breton C., Sim P., et al. Blavatnik School of Government Working Paper; Oxford: 2021. Variation in the Canadian provincial and territorial responses to COVID-19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaillancourt T., Szatmari P., Georgiades K., Krygsman A. The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of Canadian children and youth. FACETS. 2021;6:1628–1648. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institut national de santé publique du Québec Ligne du temps COVID-19 au Québec. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees/ligne-du-temps Available at:

- 15.Ministry of Health and Social Services . Government of Quebec; Quebec: 2020. Med-Echo system normative framework - Maintenance and use of data for the study of hospital clientele. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auger N., Chadi N., Ayoub A., et al. Suicide attempt and risk of substance use disorders among female youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:710–717. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pampalon R., Raymond G. A deprivation index for health and welfare planning in Quebec. Chronic Dis Can. 2000;21:104–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Statistics Canada Table 17-10-0005-01 Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501 Available at:

- 19.Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS). État des pratiques - COVID-19: Regard sur la fréquentation des urgences par les adolescents pour certaines problématiques de santé mentale et psychosociales. INESS; Quebec: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chadi N., Spinoso-Di Piano C., Osmanlliu E., et al. Mental health-related emergency department visits in adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicentric retrospective study. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:847–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernal J.L., Cummins S., Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: A tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:348–355. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penfold R.B., Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13:S38–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker M.M., Fernández A., Moffet H.H., et al. Association of patient-physician language concordance and glycemic control for limited-English proficiency Latinos with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:380–387. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warton E.M., Parker M. SAS Institute Inc; Sacramento, CA: 2018. Oops, I D-I-D it again! Advanced difference-in-differences models in SAS®. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrigan C., Duke G., Millar J., et al. Admissions of children and adolescents with deliberate self-harm to intensive care during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Australia. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.11692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batchelor S., Stoyanov S., Pirkis J., et al. Use of Kids Helpline by children and young people in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68:1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiss O., Alzueta E., Yuksel D., et al. The pandemic’s toll on young adolescents: Prevention and intervention targets to preserve their mental health. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron E.J., Goldstein E.G., Wallace C.T. Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. J Public Econ. 2020;190:104258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cappa C., Jijon I. COVID-19 and violence against children: A review of early studies. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;116:105053. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hawton K., Saunders K.E., O’Connor R.C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379:2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim M.J., Paek S.H., Kwon J.H., et al. Changes in suicide rate and characteristics according to age of suicide attempters before and after COVID-19. Children (Basel) 2022;9:151. doi: 10.3390/children9020151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang M.T., Henry D.A., Del Toro J., et al. COVID-19 employment status, dyadic family relationships, and child psychological well-being. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69:705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carbone J.T., Holzer K.J., Vaughn M.G. Child and adolescent suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: Evidence from the healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. J Pediatr. 2019;206:225–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.