Abstract

BACKGROUND

Several lines of evidence support the view that sarcopenia and osteoporosis are strictly connected. However, the capability of the updated sarcopenia definition to capture the concomitant presence of osteoporosis has been scarcely investigated.

AIM

The main aim was to assess the association between sarcopenia defined according to the revised criteria from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) and osteoporosis in women with a hip fracture. A second aim was to investigate the thresholds for low appendicular lean mass (aLM) and handgrip strength to optimize osteoporosis detection.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional study.

SETTING

Rehabilitation hospital.

POPULATION

Women with subacute hip fracture.

METHODS

A scan by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) was performed to assess body composition. A Jamar dynamometer was used to measure handgrip strength. Sarcopenia was diagnosed with both handgrip strength <16 kg and aLM <15 kg. Osteoporosis was identified with femoral bone mineral density lower than 2.5 standard deviations below the mean of the young reference population.

RESULTS

We studied 262 of 290 women. Osteoporosis was found in 189 of the 262 women (72%; 95% CI: 67-78%) whereas sarcopenia in 147 (56%; 95% CI: 50-62%). After adjustment for age, time interval between fracture and DXA scan and body fat percentage the odds ratio to have osteoporosis for a sarcopenic woman was 2.30 (95% CI: 1.27-4.14; P=0.006). Receiver operating characteristic curve analyses showed that the best cut-off points to discriminate osteoporosis were 20 kg for handgrip strength and 12.5 kg for aLM. Adopting the optimized thresholds to define sarcopenia, the adjusted odds ratio to have osteoporosis for a sarcopenic woman was 3.68 (95% CI: 1.93-7.03; P<0.001).

CONCLUSIONS

This preliminary study shows a positive association between sarcopenia defined according to the EWGSOP2 criteria and osteoporosis in 262 women with hip fracture. The association may be bettered by refining the cut-off points for low aLM and handgrip strength.

CLINICAL REHABILITATION IMPACT

Sarcopenia seems to be a risk factor for osteoporosis in hip-fracture women. The issue, and the potential role of optimized thresholds should be addressed by robust longitudinal studies.

Key words: Body composition; Absorptiometry, photon; Hip fractures; Osteoporosis; Sarcopenia

Osteosarcopenia, the concomitant presence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia, is an emerging syndrome characterized by mass loss and qualitative deterioration of both bones and skeletal muscles.1, 2 Bones become fragile and muscles loose strength and contribute to the decline in physical performance. Interest in osteosarcopenia is rapidly increasing, because of its association with unfavorable outcomes: falls, fractures, disability, institutionalization, poor quality of life and death.1, 2 Sarcopenia and osteoporosis, the 2 components of the syndrome, share several risk factors, including older age, sedentary lifestyle, poor nutrition, chronic inflammation, endocrine disorders and genetic susceptibility.3 Furthermore, muscles and bones can affect each other by mechanical and humoral factors: weak muscles can contribute to generate weak bones and vice-versa.4 As expected, given shared underlying factors and cross-talk between bones and muscles, several observational studies showed that sarcopenia and osteoporosis are significantly associated in various populations.5

One major challenge in studying osteosarcopenia and its consequences is the lack of a single definition agreed on:1 osteoporosis definition released by the World Health Organization in 1994 is still universally adopted both for clinical diagnosis and epidemiological studies,6, 7 but sarcopenia (and consequently osteosarcopenia) definition is still under development. Initially, sarcopenia definition focused on reduced muscle mass.8 However, a number of surveys have demonstrated that isolated low muscle mass is not a good biomarker for clinically relevant outcomes,9 leading to the concept that 2 crucial components must be jointly present to diagnose sarcopenia: structural damage of the muscle (loss of mass and/or quality) and impaired function.10-12 In 2019 the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) released a revised European consensus aimed at increasing consistency in the field of sarcopenia.13 The consensus indicated cut-off points for both muscle mass and function to be used in clinical and epidemiological studies. It is noteworthy that sarcopenia defined according to the revised criteria could prove to be associated with osteoporosis, to make easier interventions on both the components of the bone-muscle unit, particularly in people at high risk of unfavorable outcomes.14

Older people who sustain a fragility fracture of the hip are at high risk of falls, recurrent fractures, poor function, institutionalization and death. One year after the hip fracture, excess mortality is around 20%, whereas among the survivors one in three are totally dependent or in a nursing home and 60% do not fully regain the level of functional ability they had before the fracture occurrence.15-17

Our main aim was to assess the association between sarcopenia defined according to the EWGSOP2 criteria and osteoporosis in women with a fragility fracture of the hip. We hypothesized that sarcopenia could be a risk factor for bone fragility resulting in a higher prevalence of osteoporosis in sarcopenic women than in non-sarcopenic ones. A second aim was to investigate the thresholds for low levels of aLM and handgrip strength to optimize osteoporosis detection.

Materials and methods

Patients and setting

We performed the study in a city with around one-million inhabitants. We evaluated 290 women with subacute hip fracture who were consecutively admitted to our rehabilitation ward during a 18-month time interval. All the women were Caucasian (few non-Caucasian older women live in our city). All the hip fractures were surgically treated. The exclusion criteria were as follows: hip fractures due to either bone cancer or major trauma; presence of arthroplasties, nails, screws or other implants that could alter body composition assessment; refusal to undergo dual-energy X-ray (DXA) scan; severe cognitive impairment preventing handgrip strength measurement and/or DXA scan; impairments due to neurologic, rheumatic or other conditions that could alter handgrip strength measurement. We included only women whose hip fracture was either spontaneous or due to minimal trauma (trauma equal to or less than a fall on the ground from the standing position). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Helsinki Declaration. All the women included in the final sample gave their written informed consent to participate in the study. IRB approval was obtained for the study protocol (Ethical Committee from City of Health and Science from our city).

Outcome measures

We performed a DXA scan (Discovery Wi, Hologic Inch) to measure body composition. The sum of lean mass (LM) in arms and legs was calculated to obtain appendicular lean mass (aLM) in all the women. Because metal implants (prostheses, nails, screws) and postsurgical edema can affect local body composition, we corrected aLM by substituting LM in unfractured leg for LM in fractured leg as previously described.18 Body fat percentage was calculated by the DXA software.

Handgrip strength was measured by a Jamar dynamometer (Lafayette Instrument Co.) with the patient seated, with her shoulder adducted and neutrally rotated and with elbow at 90° of flexion, forearm neutrally rotated and wrist between 0° and 15° of ulnar deviation and 0-30° of palmar flexion. The best of three attempts of maximal effort, performed at 1-minute intervals at the dominant arm, was used for analyses.

To define sarcopenia, we adopted the criteria released in 2019 by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (known as EWGSOP2 criteria): sarcopenia was diagnosed with both handgrip strength <16 kg and aLM<15 kg.13

During the same DXA scan used to assess LM, we measured bone mineral density (BMD) at 2 sites of the non-fractured hip: femoral neck and total proximal femur. A T-score <-2.5 at least at one of the two femoral sites defined the diagnosis of osteoporosis.6 The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) supplied the reference population for T-score calculation. We did not perform a DXA scan at the lumbar spine to diagnose osteoporosis, because several highly prevalent conditions, including vertebral fractures, osteoarthritis and aortic calcifications, can alter vertebral DXA assessment in older women with hip fracture. Time interval between fracture occurrence and DXA assessment was recorded in each patient.

Height was measured with standard method in the vast majority of the women, whereas 7 women who could not keep the standing position at the time of assessment were measured supine. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by height squared (m).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are shown as mean and standard deviation after checking the shown variables for normality by a Shapiro-Wilk Test. The association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis was preliminary investigated by a χ2 test for independence. A binary logistic regression test was used to further assess the association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis (dependent variable) either unadjusted or after adjustment for age, body fat percentage and time interval between hip fracture occurrence and DXA scan. The analysis was repeated after substituting BMI for body fat percentage among the independent variables.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to assess the optimal cut-off points for both handgrip strength and aLM to discriminate subjects with and without osteoporosis. The Youden Index was used to find optimal cut-off points. The 262 women were re-categorized according to the new thresholds and binary logistic regression analyses with osteoporosis as the dependent variables were repeated. In the new regression models, low levels of aLM and grip strength were included either as 2 independent variables or combined to define sarcopenia according to the optimized thresholds.

We had no missing data.

The statistical package used was SPSS, version 17.

Availability of data and material: Any additional information is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

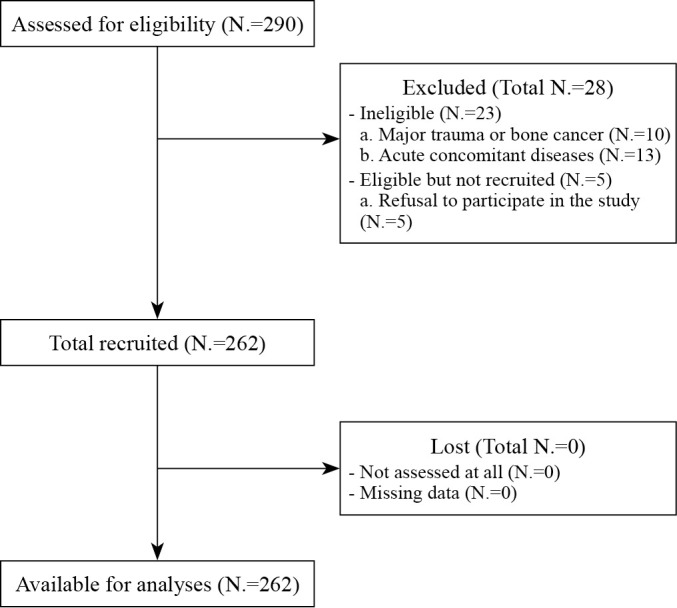

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram for the study: data from 262 of the 290 women were available for analyses. The descriptive statistics for the 262 participants are shown in Table I.

Figure 1.

—Flow diagram for the study participants.

Table I. —Characteristics in 262 women.

| Age, years | 79.7 (7.6) |

| Height, cm | 158.2 (6.8) |

| Weight, kg | 59.7 (12.7) |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 23.8 (4.7) |

| Body fat percentage | 39.2 (8.3) |

| Bone mineral density at total hip, T-score | -2.4 (0.9) |

| Bone mineral density at femoral neck, T-score | -2.8 (0.8) |

| Corrected appendicular lean mass, kg | 12.8 (2.4) |

| Time interval between fracture occurrence and DXA scan, days | 20.7 (9.0) |

| Handgrip strength, kg | 13.3 (7.5) |

Data is shown as mean (standard deviation).

Osteoporosis was found in 189 of the 262 women (72%; 95% CI: 67-78%) whereas sarcopenia was found in 147 of the 262 women (56%; 95% CI: 50-62%). The presence of sarcopenia was significantly associated with the presence of osteoporosis: χ2 (1, N.=262)=13.97, P<0.001. Based on either the presence of sarcopenia or its absence, we correctly classified 120 of the 189 women with osteoporosis and 46 of the 73 without osteoporosis (sensitivity 63%, specificity 63%, positive predictive value 82%, negative predictive value 40%). The unadjusted odds ratio to suffer from osteoporosis for the women with sarcopenia was 2.93 (95% CI: 1.69 to 5.19, P<0.001). After adjustment for age, time interval between fracture and DXA scan and body fat percentage the odds ratio to have osteoporosis for a sarcopenic woman was 2.30 (95% CI: 1.27 to 4.14; P=0.006) as shown in Table II.

Table II. —Binary logistic regression analysis (I): association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis adjusted for age, body fat percentage and time interval between fracture and DXA scan.

| Independent variables | B (SE) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sarcopenia | 0.83 (0.30) | 2.30 (1.27-4.14) | 0.006 |

| Age (years) | -0.05 (0.02) | 1.05 (1.01-1.09) | 0.021 |

| Time interval fracture-DXA scan (days) | 0.003 (0.02) | 1.003 (0.97-1.03) | 0.875 |

| Body fat percentage | -0.03 (0.02) | 0.97 (0.93-1.005) | 0.089 |

The dependent variable was the presence of osteoporosis. The independent variables included in the regression model are listed in the table. The presence of sarcopenia was conventionally attributed a value of 1 (the absence of sarcopenia a value of 0).

When BMI was substituted for body fat percentage among the independent variables in the binary logistic regression model, the adjusted odds ratio to have osteoporosis for a sarcopenic woman became 1.94 (95% CI: 1.05 to 3.56; P=0.033. Data not shown in detail).

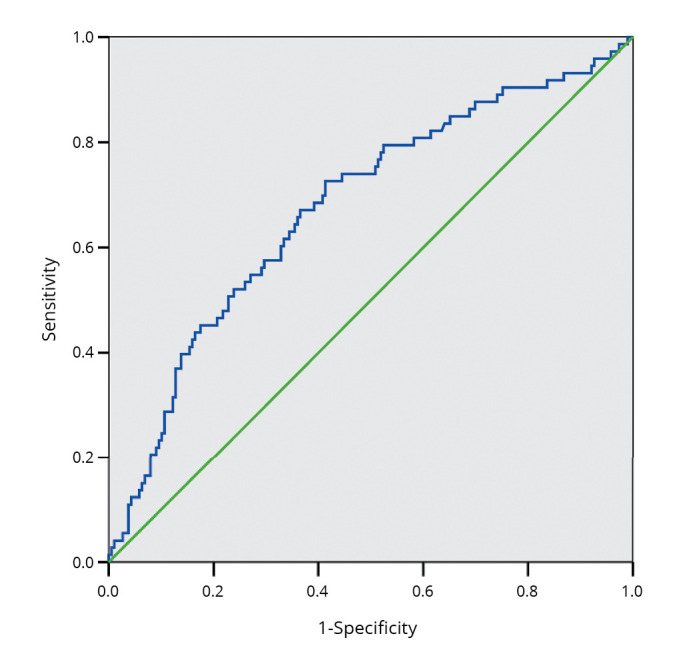

Results of the ROC curve analyses are shown in Figure 2, 3. The best cut-off points to discriminate osteoporosis were 20kg for handgrip strength (Figure 2) and 12.5 kg for aLM (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

—Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (I). We assessed the ability of handgrip strength to discriminate the women with or without osteoporosis. The area under the curve was 0.64 (95% CI: 0.56-0.71, P=0.001).

Figure 3.

—Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (II). We assessed the ability of appendicular lean mass to discriminate the women with or without osteoporosis. The area under the curve was 0.68 (95% CI: 0.60-0.75, P<0.001).

When categorizations according to either handgrip strength <20 kg or aLM <12.5 kg were included together as independent variables in the regression models, both of them were significantly associated with the presence of osteoporosis (Table III).

Table III. —Binary logistic regression analysis (II): association between low levels of handgrip strength and appendicular lean mass (both defined according to the optimized thresholds found by the ROC curve analyses) and osteoporosis adjusted for age, body fat percentage and time interval between fracture and DXA scan.

| Independent variables | B (SE) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low handgrip strength (<20 kg) | 0.86 (0.36) | 2.37 (1.16-4.83) | 0.017 |

| Low appendicular lean mass (<12.5 kg) | 1.18 (0.31) | 3.25 (1.75-6.02) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 0.04 (0.02) | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | 0.062 |

| Time interval fracture-DXA scan (days) | 0.001 (0.02) | 1.001 (0.97-1.03) | 0.952 |

| Body fat percentage | -0.04 (0.02) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 0.044 |

The dependent variable was the presence of osteoporosis. The independent variables included in the regression model are listed in the table. The presence of low handgrip strength and low appendicular lean mass was conventionally attributed a value of 1 (the absence of low levels was attributed a value of 0).

The concomitant presence of handgrip strength <20 kg and aLM <12.5 kg (optimized thresholds) was found in 118 of the 262 women (45%, CI 39-51%). The presence of sarcopenia defined according to the optimized thresholds was significantly associated with the presence of osteoporosis: χ2 (1, N.=262)=20.58, P<0.001. Based on either the presence of sarcopenia defined according to the optimized thresholds or its absence, we correctly classified 102 of the 189 women with osteoporosis and 57 of the 73 without osteoporosis (sensitivity 54%, specificity 78%, positive predictive value 86%, negative predictive value 40%). The unadjusted odds ratio to suffer from osteoporosis for the women with sarcopenia defined according to the optimized thresholds was 4.18 (95% CI: 2.24-7.79, P<0.001). After adjustment for age, time interval between fracture and DXA scan and body fat percentage the odds ratio to have osteoporosis for a sarcopenic woman was 3.68 (95% CI: 1.93-7.03; P<0.001) as shown in Table IV.

Table IV. —Binary logistic regression analysis (III): association between sarcopenia (defined according to the optimized thresholds for handgrip strength and appendicular lean mass) and osteoporosis adjusted for age, body fat percentage and time interval between fracture and DXA scan.

| Independent variables | B (SE) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sarcopenia (with optimized thresholds) | 1.30 (0.33) | 3.68 (1.93-7.03) | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 0.04 (0.02) | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | 0.038 |

| Time interval fracture-DXA scan (days) | 0.002 (0.02) | 1.002 (0.97-1.03) | 0.906 |

| Body fat percentage | -0.04 (0.02) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | 0.036 |

The dependent variable was the presence of osteoporosis. The independent variables included in the regression model are listed in the table. The presence of sarcopenia was conventionally attributed a value of 1 (the absence of sarcopenia a value of 0).

When BMI was substituted for body fat percentage among the independent variables in the binary logistic regression model, the adjusted odds ratio to have osteoporosis for a sarcopenic woman became 2.89 (95% CI: 1.49-5.60; P=0.002. Data not shown in detail).

Discussion

We show a positive association between sarcopenia defined according to the EWGSOP2 criteria and osteoporosis in 262 women with a fragility fracture of the hip. To our knowledge, a single study investigated the same issue, showing that sarcopenia and osteoporosis were positively associated in 313 women with subacute hip fracture.18 The novelty of the current data rests on 2 aspects. Firstly, the diagnostic criteria were updated: sarcopenia was diagnosed with the concurrent presence of low muscle mass and low muscle strength, both identified with cut-off points aimed at predicting relevant outcomes.13 Conversely, in the previous report (published in 2011) sarcopenia was diagnosed with isolated low aLM, defined according to normative data from the New Mexico Elder Health Study,8 with the cut-off point arbitrarily set at two standard deviations below the mean of the young reference group.18 The second novelty is data adjustment for measures of fatness, either body fat percentage or BMI to take into account their potential confounding role. This is noteworthy, because of the tight connections among fat, muscle and bone involving mechanisms at both cellular and endocrine levels, from the stem cell lineage commitment to the release of osteokines, myokines and adipokines that are responsible for the continuous inter-tissue cross-talk.19, 20 Indeed, alterations of the three tissues, namely obesity, sarcopenia and osteoporosis, share several risk factors including hormonal changes, physical inactivity, altered nutrition, various non-communicable diseases, chronic inflammation and aging.19, 20

The positive association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis we describe is consistent with several reports in older women not selected on the basis of a recent hip fracture who were classified according to various sarcopenia definitions by different authors.4 Two recent studies adopted the EWGSOP2 criteria for diagnosing sarcopenia; notably, both of them confirmed the positive association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Nielsen et al. investigated 529 Danish people (297 women) aged 65-93 years showing that individuals with sarcopenia were more likely to have low bone mineral density: the odds ratio for having osteoporosis was 7.3 (95% confidence interval from 2.3 to 22.8) for sarcopenic versus non-sarcopenic subjects.21 Scott et al. investigated 3334 people from Sweden (50.6% women) who were aged 70 years.22 Osteoporosis prevalence was significantly higher in sarcopenic subjects than in non-sarcopenic ones (44.9% versus 12.8%, P<0.001). Both the studies had 2 relevant limitations:21, 22 mixed sample (data from men and women were analyzed together) and very low prevalence of osteosarcopenia (a total of 8 individuals in the survey by Nielsen et al., and 16 in the study by Scott et al. were concurrently affected by osteoporosis and sarcopenia). The 2 limitations of the previous studies strengthen the novelty of our current data obtained in a sample of women (thus avoiding any sex-associated confounding role) whose prevalence of osteosarcopenia (46%) was high. The prevalence of osteoporosis we found (72%) is in agreement with several previous reports in women with hip fracture and with the well-known role of low BMD in the genesis of bone fragility and fractures.6, 23-25 Advanced age was significantly associated with osteoporosis in our sample, in agreement with the wider literature.6

The significant association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis in women with hip fracture may have both prognostic and therapeutic implications. Osteosarcopenia has been shown to carry prognostic disadvantages in patients with hip fracture. Bae et al. prospectively investigated 154 patients up to one year after hip fracture.25 Osteosarcopenia was associated with reduced ability in activities of daily living assessed by the Barthel index, impaired hip function measured by the Harris Hip Score and increased risk of incident fractures. Yoo et al. investigated 324 patients in a retrospective survey, showing that osteosarcopenia was associated with an 80% increase in the one-year mortality.26 Kim et al. showed an osteosarcopenia-associated increase in the 5-year mortality rate of 91 patients with hip fracture in a retrospective study.27 Di Monaco et al. performed a cross-sectional study of 350 women with subacute hip fracture showing that the burden (number and severity) of prevalent vertebral fractures, which is in turn associated with poor functional recovery and high mortality rates,23, 24 was higher in the women with osteosarcopenia than in those with isolated sarcopenia or osteoporosis.28 Given the tight links between sarcopenia and osteoporosis, optimal treatment options and preventive strategies should ideally target both the components of the muscle-bone unit. Currently, a pivotal role in optimizing the health state of both muscles and bones is thought to be played by lifestyle changes, including increase in physical activity and adequate nutrition, with special consideration to proteins and vitamin D.1-3, 6, 29 Unfortunately, the evidence from randomized controlled trials focusing on the concomitant effects of lifestyle changes on both the components of the muscle-bone unit is still weak.14, 30 Several effective medications to prevent fragility fractures are available. However, they have been developed targeting only bones,31 whereas medications targeting muscles are still under development.2, 32 Interestingly, some data suggest that medications primarily acting on bone as antiresorptive agents (i.e., denosumab and bisphosphnates) may also exert muscle mediated effects which may contribute to their antifracture activity.33-35 Furthermore, some of the molecules potentially active on the muscle may also exert favorable effects on bone.2, 32 It is advisable that future studies on both lifestyle changes and medications consider outcome measures at the muscle-bone-unit level. In this view, it is noteworthy that sarcopenia could be associated with osteoporosis, thus helping clinicians to focus on damages affecting both muscles and bones. We show that EWGSOP2 criteria to define sarcopenia discriminate concurrent osteoporosis in our sample of women with subacute hip fracture, although with moderate sensitivity and specificity. We also show that the capability to discriminate osteoporosis may be improved by optimizing the thresholds that define low levels of aLM and handgrip strength. Notably, the categorizations according to both aLM and strength were significantly and independently associated with the presence of osteoporosis. Previous studies have supported the association of low bone mineral density with both low aLM and low handgrip strength, although the independence of the two which is suggested by our data has not been established.36-40 Sarcopenia definition is still under development and our data may contribute to refine the cut-off points for low muscle mass and muscle strength. Besides refining thresholds, several other issues need to be addressed in order to achieve a single definition of sarcopenia universally agreed on.41, 42 One crucial point regards proper performance tests to assess either sarcopenia presence or its severity. Unfortunately, we could not contribute to optimize performance evaluation, because of the specific features of the study sample: the recent hip fracture and its surgical treatment are expected to be major determinants of body function and activities involving the lower limbs, thus acting as pivotal confounders. One more debated issue in sarcopenia definition is the optimal assessment of muscle mass. We performed a DXA scan to measure aLM as indicated by the EWGSOP2 criteria and by several other sarcopenia definitions.13, 41, 42 However, doubts exist about the relevance of DXA assessed aLM in the prediction of clinical outcomes.43 It has been suggested that DXA failure as a prognostic tool may rest on its incapability to detect qualitative changes in muscle tissue that strongly contribute to the loss of muscle function irrespectively of muscle mass. Indeed, several important damages of the muscle cannot be detected by DXA: fat infiltration and increase of connective tissue within the muscle, selective loss of type II fibers, altered satellite cell properties, metabolic changes and variations in the muscle spindle.44 Furthermore, DXA assessment may be affected by changes in body hydration that could falsely influence aLM measure.45 Very recently, a special working group from the International Society of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine has proposed one more explanation for DXA inadequacy in the prediction of clinical outcomes: regional (not generalized) muscle loss, particularly in the anterior thighs, has been proposed as the true determinant of clinically relevant sarcopenia.43 A novel approach arises: anterior thigh muscle measurement is pointed out as the proper assessment of muscle mass to diagnose clinically relevant sarcopenia. Notably, a recent cross-sectional study of 326 community-dwelling adults, actually found a negative correlation between the anterior thigh muscle thickness measured using ultrasound and various performance tests.46 Sex specific thresholds for sonographic thickness of the anterior thigh muscles adjusted for body mass index have been proposed for sarcopenia diagnosis.46 Validation of the new approach, particularly by longitudinal studies including people at high risk of unfavorable outcomes is strongly advocated.

Limitations of the study

Our study has limitations. Firstly, we cannot generalize our conclusions to all the patients suffering from hip fractures, because we selectively studied women who were surgically operated on and who were admitted to a single rehabilitation ward in Italy. Secondly, our DXA scan was performed after hip fracture and we cannot exclude changes in body composition due to hip fracture with associated reduced mobility and nutritional deficiencies. Indeed, a decrease in aLM has been shown after hip fracture: a mean percentage reduction of either 3.4% or 6.2% was prospectively shown at a 2-mo follow-up, whereas no significant changes were found 10 days after the fracture.47, 48 We hypothesize that changes in aLM could be small in our study, because we assessed body composition at a median of 21 days after fracture occurrence, but we have no data on postfracture changes. Finally, the study design was cross-sectional: we did not collect prospective data to investigate the relationship between sarcopenia and osteoporosis over time.

Conclusions

The association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis we describe contributes to the concept of tight links between bones and muscles in the poorly investigated population of older women with a fragility fracture of the hip. Future studies on prevention and treatment of sarcopenia and osteoporosis should ideally target both muscles and bones and outcome measures of the 2 components of the muscle-bone unit should be concurrently assessed. In this view, it is noteworthy that sarcopenia defined according to the EWGSOP2 criteria seems able to capture the women with concomitant osteoporosis, although with modest sensitivity and specificity. The issue, and the potential role of optimized thresholds for defining low levels of aLM and handgrip strength should be addressed by robust prospective studies.

References

- 1.Kirk B, Zanker J, Duque G. Osteosarcopenia: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment-facts and numbers. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020;11:609–18. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32202056&dopt=Abstract 10.1002/jcsm.12567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paintin J, Cooper C, Dennison E. Osteosarcopenia. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2018;79:253–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29727228&dopt=Abstract 10.12968/hmed.2018.79.5.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagundes Belchior G, Kirk B, Pereira da Silva EA, Duque G. Osteosarcopenia: beyond age-related muscle and bone loss. Eur Geriatr Med 2020;11:715–24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32676865&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s41999-020-00355-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He C, He W, Hou J, Chen K, Huang M, Yang M, et al. Bone and muscle crosstalk in aging. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020;8:585644. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33363144&dopt=Abstract 10.3389/fcell.2020.585644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirk B, Phu S, Brennan-Olsen SL, Bani Hassan E, Duque G. Associations between osteoporosis, the severity of sarcopenia and fragility fractures in community-dwelling older adults. Eur Geriatr Med 2020;11:443–50. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32297263&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s41999-020-00301-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY, Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis (ESCEO) and the Committees of Scientific Advisors and National Societies of the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) . European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 2019;30:3–44. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30324412&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s00198-018-4704-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iolascon G, de Sire A, Curci C, Paoletta M, Liguori S, Calafiore D, et al. Osteoporosis guidelines from a rehabilitation perspective: systematic analysis and quality appraisal using AGREE II. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2021;57:273–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33650841&dopt=Abstract 10.23736/S1973-9087.21.06581-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D, Romero L, Heymsfield SB, Ross RR, et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:755–63. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=9554417&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhasin S, Travison TG, Manini TM, Patel S, Pencina KM, Fielding RA, et al. Sarcopenia Definition: The Position Statements of the Sarcopenia Definition and Outcomes Consortium. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:1410–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32150289&dopt=Abstract 10.1111/jgs.16372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, et al. European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People . Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing 2010;39:412–23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=20392703&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/ageing/afq034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE, Cawthon PM, McLean RR, Harris TB, et al. The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69:547–58. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=24737557&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/gerona/glu010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Bahyah KS, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:95–101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=24461239&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. ; Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019;48:16–31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30312372&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/ageing/afy169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atlihan R, Kirk B, Duque G. Non-Pharmacological Interventions in Osteosarcopenia: A Systematic Review. J Nutr Health Aging 2021;25:25–32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33367459&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s12603-020-1537-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maggi S, Siviero P, Wetle T, Besdine RW, Saugo M, Crepaldi G, Hip Fracture Study Group . A multicenter survey on profile of care for hip fracture: predictors of mortality and disability. Osteoporos Int 2010;21:223–31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=19415372&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s00198-009-0936-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham DS, Barr E, Ostir GV, Hebel JR, Golden J, Gruber-Baldini AL, et al. Residual disability, mortality, and nursing home placement after hip fracture over 2 decades. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019;100:874–82. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30391413&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu BY, Yan S, Low LL, Vasanwala FF, Low SG. Predictors of poor functional outcomes and mortality in patients with hip fracture: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:568. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31775693&dopt=Abstract 10.1186/s12891-019-2950-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Monaco M, Vallero F, Di Monaco R, Tappero R. Prevalence of sarcopenia and its association with osteoporosis in 313 older women following a hip fracture. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011;52:71–4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=20207030&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.archger.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly OJ, Gilman JC, Boschiero D, Ilich JZ. Osteosarcopenic obesity: current knowledge, revised identification criteria and treatment principles. Nutrients 2019;11:747. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30935031&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/nu11040747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer JM, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Fielding RA, Kanis JA, Reginster JY, Bruyère O, et al. Is there enough evidence for osteosarcopenic obesity as a distinct entity? A critical literature review. Calcif Tissue Int 2019;105:109–24. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31098729&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s00223-019-00561-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nielsen BR, Andersen HE, Haddock B, Hovind P, Schwarz P, Suetta C. Prevalence of muscle dysfunction concomitant with osteoporosis in a home-dwelling Danish population aged 65-93 years - The Copenhagen Sarcopenia Study. Exp Gerontol 2020;138:110974. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32464171&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.exger.2020.110974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott D, Johansson J, McMillan LB, Ebeling PR, Nordstrom P, Nordstrom A. Associations of sarcopenia and its components with bone structure and incident falls in Swedish older adults. Calcif Tissue Int 2019;105:26–36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30899995&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s00223-019-00540-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ha YC, Baek JH, Ko YB, Park SM, Song SH. High mortality and poor morbidity after hip fracture in patients with previous vertebral fractures. J Bone Miner Metab 2015;33:547–52. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=25227286&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s00774-014-0616-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C, Di Monaco R, Tappero R. Prevalence and burden of vertebral fractures in older men and women with hip fracture: A cross-sectional study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2016;16:352–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=25809960&dopt=Abstract 10.1111/ggi.12479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bae GC, Moon KH. Effect of osteosarcopenia on postoperative functional outcomes and subsequent fracture in elderly hip fracture patients. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2020;11:2151459320940568. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32699654&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/2151459320940568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoo JI, Kim H, Ha YC, Kwon HB, Koo KH. Osteosarcopenia in patients with hip fracture is related with high mortality. J Korean Med Sci 2018;33:e27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29318794&dopt=Abstract 10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim YK, Yi SR, Lee YH, Kwon J, Jang SI, Park SH. Effect of sarcopenia on postoperative mortality in osteoporotic hip fracture patients. J Bone Metab 2018;25:227–33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30574467&dopt=Abstract 10.11005/jbm.2018.25.4.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C, Bardesono F, Milano E, Massazza G. Sarcopenia, osteoporosis and the burden of prevalent vertebral fractures: a cross-sectional study of 350 women with hip fracture. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020;56:184–90. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32052946&dopt=Abstract https://doi.org/ 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.05991-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Filipovi Ć TN, Lazovi Ć MP, Backovi Ć AN, Filipovi Ć AN, Ignjatovi Ć AM, Dimitrijevi Ć SS, et al. A 12-week exercise program improves functional status in postmenopausal osteoporotic women: randomized controlled study. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2021;57:120–30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32902207&dopt=Abstract 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06149-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Rui M, Inelmen EM, Pigozzo S, Trevisan C, Manzato E, Sergi G. Dietary strategies for mitigating osteosarcopenia in older adults: a narrative review. Aging Clin Exp Res 2019;31:897–903. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30674008&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s40520-019-01130-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouxsein ML, Eastell R, Lui LY, Wu LA, de Papp AE, Grauer A, et al. ; FNIH Bone Quality Project. Change in Bone Density and Reduction in Fracture Risk: A Meta-Regression of Published Trials. J Bone Miner Res 2019;34:632–42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30674078&dopt=Abstract 10.1002/jbmr.3641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwak JY, Kwon KS. Pharmacological interventions for treatment of sarcopenia: current status of drug development for sarcopenia. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2019;23:98–104. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32743297&dopt=Abstract 10.4235/agmr.19.0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chotiyarnwong P, McCloskey E, Eastell R, McClung MR, Gielen E, Gostage J, et al. A pooled analysis of fall incidence from placebo-controlled trials of denosumab. J Bone Miner Res 2020;35:1014–21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31999376&dopt=Abstract 10.1002/jbmr.3972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonnet N, Bourgoin L, Biver E, Douni E, Ferrari S. RANKL inhibition improves muscle strength and insulin sensitivity and restores bone mass. J Clin Invest 2019;129:3214–23. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=31120440&dopt=Abstract 10.1172/JCI125915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein GL. Pharmacologic Treatments to Preserve Bone and Muscle Mass in Osteosarcopenia. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2020;18:228–31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32172444&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s11914-020-00576-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon WG, Lunt M, Pye SR, Reeve J, Felsenberg D, Silman AJ, et al. European Prospective Osteoporosis Study Group . Low grip strength is associated with bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in women. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:642–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15728415&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/rheumatology/keh569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rikkonen T, Sirola J, Salovaara K, Tuppurainen M, Jurvelin JS, Honkanen R, et al. Muscle strength and body composition are clinical indicators of osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 2012;91:131–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=22733383&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s00223-012-9618-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li YZ, Zhuang HF, Cai SQ, Lin CK, Wang PW, Yan LS, et al. Low grip strength is a strong risk factor of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Orthop Surg 2018;10:17–22. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29430846&dopt=Abstract 10.1111/os.12360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Monaco M, Castiglioni C, Di Monaco R, Tappero R. Association between low lean mass and low bone mineral density in 653 women with hip fracture: does the definition of low lean mass matter? Aging Clin Exp Res 2017;29:1271–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28160254&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s40520-017-0724-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miranda C, de Morais VF, Martins FM, Pelet DC, Orsatti CL, Cangussu-Oliveira LM, et al. Different cutoff points to diagnose low muscle mass and prediction of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2021;28:1181–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34284436&dopt=Abstract 10.1097/GME.0000000000001820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carvalho do Nascimento PR, Bilodeau M, Poitras S. How do we define and measure sarcopenia? A meta-analysis of observational studies. Age Ageing 2021;50:1906–13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34537833&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/ageing/afab148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dent E, Woo J, Scott D, Hoogendijk EO. Sarcopenia measurement in research and clinical practice. Eur J Intern Med 2021;90:1–9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34238636&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kara M, Kaymak B, Frontera W, Ata AM, Ricci V, Ekiz T, et al. Diagnosing sarcopenia: functional perspectives and a new algorithm from the ISarcoPRM. J Rehabil Med 2021;53:jrm00209. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34121127&dopt=Abstract 10.2340/16501977-2851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Degens H, Korhonen MT. Factors contributing to the variability in muscle ageing. Maturitas 2012;73:197–201. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=22902240&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toomey CM, McCormack WG, Jakeman P. The effect of hydration status on the measurement of lean tissue mass by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Eur J Appl Physiol 2017;117:567–74. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28204901&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s00421-017-3552-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kara M, Kaymak B, Ata AM, Özkal Ö, Kara Ö, Baki A, et al. STAR-Sonographic Thigh Adjustment Ratio: A golden formula for the diagnosis of sarcopenia. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2020;99:902–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32941253&dopt=Abstract 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fox KM, Magaziner J, Hawkes WG, Yu-Yahiro J, Hebel JR, Zimmerman SI, et al. Loss of bone density and lean body mass after hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 2000;11:31–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10663356&dopt=Abstract 10.1007/s001980050003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D’Adamo CR, Hawkes WG, Miller RR, Jones M, Hochberg M, Yu-Yahiro J, et al. Short-term changes in body composition after surgical repair of hip fracture. Age Ageing 2014;43:275–80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=24370941&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/ageing/aft198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]