ABSTRACT

Breast cancer is a phenomenon in which breast epithelial cells proliferate out of control under the action of various carcinogenic factors. However, the role of USP36 in breast cancer is unknown. We analyzed the expression of USP36 in breast cancer and its association with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. The effect of USP36 on malignant biological behavior of breast cancer was verified by cell functional experiments. The upstream regulatory mechanism of USP36 was analyzed by Western blot and quantitative RT-qPCR. The influence of USP36 on the Warburg effect of breast cancer was analyzed by detecting the metabolism of cellular energy substances. We found that USP36 is highly expressed in breast tumor tissues and breast cancer cell lines. High expression of USP36 predicts poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Effectively reducing the expression of USP36 can significantly inhibit the proliferation, invasion and migration of breast cancer cells, and promote the apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Meanwhile, inhibiting the expression of USP36 can significantly inhibit the production of ATP, lactate, pyruvate and glucose uptake in breast cancer cells. miR-140-3p is an upstream regulator of USP36, which can partially reverse the regulatory effect of USP36 on breast cancer cells. Importantly, USP36 regulates the expression of PKM2 through ubiquitination, which plays a role in regulating the Warburg effect. We confirmed that miR-140-3p regulates the expression of USP36, which mediates ubiquitination and regulates the expression of PKM2, and regulates the malignant biological behavior of breast cancer through the energy metabolism process.

Keywords: miR-140-3p, USP36, ubiquitination, PKM2, breast cancer, warburg effect

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the common malignant tumors [1]. The rearrangement of energy metabolism is an important biological feature of breast cancer [2]. The rearrangement of energy metabolism of breast cancer cells largely determines the malignant development and poor prognosis of breast cancer [2]. Although the mechanism of the rearrangement of energy metabolism has not been fully elucidated, it has been clear that the formation of Warburg effect is one of its key links [3]. Malignant tumors grow rapidly. Even when the oxygen supply is sufficient, tumor cells still actively take glucose and glycolysis [4]. The generated pyruvate can be reduced to a large amount of lactic acid by receiving hydrogen removed from propionate phosphate under the catalysis of lactate dehydrogenase [5]. Moreover, Warburg effect can make tumor cells produce more acid than normal cells, which has adverse effects on surrounding normal host cells [6]. Although the exact mechanism by which the Warburg effect causes malignant growth of tumor cells is not clear, it is clear that the Warburg effect does not only lie in the production of glycolytic ATP, but also produces many precursor intermediates as anabolic processes, such as the production of NADPH, ribose-6-phosphonic acid, amino acids, lipids, and other cellular energy (de novo synthesis of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats), provide sufficient material and energy basis for the rapid proliferation and growth of tumor cells [7–10].

Protein ubiquitination is a common post-translational modification of proteins, and it is a reversible dynamic process [11]. Ubiquitin protein modifiers can be removed by deubiquitination enzyme (DUB) [12]. Ubiquitin specific proteases (USPS) are the largest subfamily of deubiquitinated enzymes (DUB), which can catalyze the removal of polyubiquitin chains of target proteins, inhibit the degradation of target proteins by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway, and increase the stability of target proteins [13]. It was found that USPS family played a significant role in regulating glucose metabolism of cells [14]. USPS can play an important regulatory role in the process of glucose metabolism by deubiquitination of key proteins and signaling pathways related to glucose metabolism [15]. USP36 is a newly identified member of the USPS family [16]. It is localized in the nucleus and cytoplasm and mediates the deubiquitination of substrate proteins [17]. In addition, the study found that PKM2 is a unique substrate of the ubiquitin E3 ligase Parkin, which catalyzes the binding of ubiquitin to PKM2 at lys-186 and lys-206 sites, resulting in PKM2 ubiquitination, thereby increasing the level of cellular glycolytic metabolism [18]. However, whether USP36 mediated deubiquitination is involved in the regulation of PKM2 expression and whether it promotes or inhibits Warburg effect has not been reported.

In this study, we will analyze the upstream regulation mechanism of USP36, explore the specific regulation mechanism of USP36 on PKM2 and its impact on Warburg effect, and provide scientific basis for studying the energy metabolism rearrangement of breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Patient sample collection

51 breast cancer samples were retrospectively obtained from Department of Breast Surgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (age range, 21–77 years; all patients were female). All patients provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital, Sichuan university, and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Cell lines and cell culture

SKBR3, MDA-MB-231, MCF-7 and BT-474 (breast cancer cell lines), and MCF-10A (human normal mammary epithelial cell lines) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Breast cancer cell lines were cultured in DMEM (Gibco USA) containing 10% FBS (Gibco USA). MCF-10A cells were cultured in MEBM (CC-3151, Switzerland) supplemented with MEGM® SingleQouts® (CC-4136, Lonza) and 10% FBS (Gibco USA).

Cell transfection

Cells were transfected with the following plasmids: shRNA overexpression USP36 (Lv-USP36), shRNA downregulation USP36 (De-USP36), shRNA overexpression PKM2 (Lv-PKM2), miR-140-3p mimics (miR-140-3p), miR-140-3p inhibitor (De-miR-140-3p) (GenePharma, Shanghai, China). Plasmids were transfected into breast cancer cells with Lipofectamine® 3000 (Invitrogen).

Immunohistochemistry

The sample were dehydrated with xylene and alcohol. Antigen retrieval was performed in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate solution (pH 6.0) at 100°C for 16 min, and the samples were cooled for 30 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity using 3% hydrogen peroxide and blocked with fetal bovine serum for 30 min. Then, the slides were incubated with USP36 (ab236452, 1:200, Abcam, USA) at 4°C overnight. Next, the samples incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody at 37°C for 30 min. The samples were stained with DAB (3, 3- diaminobenzidine) and Mayer’s hematoxylin.

TCGA analysis

We used UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/cgi-bin/ualcan-res.pl) to analyze the expression of USP36 in the TCGA databases.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from breast cancer tumor tissues, paired normal adjacent tissues and cell lines by TRIzol reagent (TaKaRa, Japan). The extracted RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA by PrimeScript RT Reagent (TaKaRa, Japan). qRT – PCR was performed with Prime-Script® RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Japan), and a LightCycler system (Roche) was used for detection. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The relative RNA expression levels were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCq method. USP36: 5’ - -AGC ACT TTT CCC CCA GAA CTG −3’; reverse: 5’—GGC TCC CAG ATC TGC TGC TA −3’; GAPDH: forward: 5’- GGA GCG ACA TCC GTC CAA AAT −3’; reverse: 5’- GGC TGT TGT CAA TCT TCT CAT GG −3’.

Western blot

Total protein was isolated from breast cancer tumor tissues, paired normal adjacent tissues and cell lines by protein extraction buffer (RIPA lysis buffer). Total protein was separated on 10% SDS – PAGE gels. The membranes blocked in 5% nonfat powdered milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were probed at 4°C overnight with USP36 (ab236452, 1:1000, USA), PKM2 (ab137852, 1:1000, USA) and β-actin (ab8226, 1:5000, USA). Then, the membranes incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies. Finally, protein expression was analyzed by chemiluminescence reagents (Hyperfilm ECL, USA).

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Cells were collected and lysed using RIPA Lysis Buffer (Beyotime, China) of which containing protease inhibitor (Beyotime, China). 3 ug antibody was added into the lysate and incubated overnight at 4°C, then, 20 μL Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose beads (Santa Cruz, USA) was added into the lysate and rotated for 4 h at 4°C. The beads-antibody-protein complexes were washed with pre-cooled PBS solution for three times, and then boiled for subsequent western blot analysis.

Ubiquitination Assay

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were lysed in 1% SDS-containing radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer by sonication on ice. Then, lysates were treated with Protein A/G Plus-Agarose (sc-2003, Santa Cruz, USA) for 1 h. After that, each sample was incubated with the IgG (30000-0-AP, Proteintech, USA) overnight at 4°C. Then, the nuclear pellet was collected by centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C and subsequently washed four times by Protein A/G Plus-Agarose beads. The purified proteins were separated by gradient SDS-PAGE. Anti-PKM2 (ab137852, Abcam, USA) or anti-ubiquitin antibody (ab7780, Abcam, USA) was used for immunoblotting.

miRNA prediction

TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org), Oncomir (http://www.oncomir.org/), and miRWalk (http://mirwalk.umm.uni-heidelberg.de/) were used to predict miRNA targets and conserved sites bound by USP36.

Dual luciferase reporter assay

TargetScan was used to identify downstream target genes of miR-140-3p. The wild-type (WT) USP36-3”UTR and mutant (MUT) USP36-3”UTR oligonucleotides containing the putative binding site of miR-140-3p were cloned into the firefly luciferase-expressing pMIR-REPORT vector (Obio Technology Corp, USA). These constructs were cotransfected with miR-140-3p mimics, miRNA negative control mimics, miR-140-3p inhibitor, miRNA-NC inhibitor into breast cancer cells. After 48 h of transfection, luciferase activity was determined using the Dual- Luciferase Reporter Assay kit (Promega Corporation) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The ratio of Renilla luciferase activity to firefly luciferase activity was calculated.

Cell migration and invasion assays

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were seeded into the upper chamber of Transwell chambers. Then, 500 µl of high-glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS were added to the matched lower chamber. After incubation for 48 h, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells moved to the lower chamber. The cells were fixed in methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. For the invasion assay, the inserts were precoated with Matrigel (1 mg/mL).

5-Ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were transfected and inoculated into 96-well plates. Then, the cells were immobilized with 4% paraformaldehyde, and nuclei were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 solution. EdU (50 μM), 1× ApolloR reaction cocktail (100 μl) and 1× DAPI (100 μl) to 96-well plates. Cell proliferation was analyzed using the mean number cells per group.

Flow cytometry for cell apoptosis

For cell apoptosis, after transfection, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were seeded into 6 well plates. Once they reached confluence, cells were collected and incubated with Annexin V‑FITC (5 μl) and propidium iodide (PI) solution (5 μl; Biogot Technology Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 15 min according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Cells were subsequently suspended in 500 μl binding buffer.

Glucose uptake assay

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were incubated in DMEM medium without L-glucose and phenol red for 8 h. The amount of glucose in these media was measured using a Glucose Colorimetric Assay kit (Bio Vision, USA). Fresh DMEM medium was used for the negative control. Three biological replicates were performed.

Intracellular pyruvate assay, lactate assay, and ATP assay

MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells were incubated in phenol red-free DMEM medium without FBS. Then, pyruvate Assay Kit (Solarbio, China), Lactate Assay Kit (Solarbio, China), and ATP Assay Kit (Solarbio, China) were used to measure intracellular concentration of pyruvate, lactate, and ATP level, respectively. Then used for subsequent procedure according to the product manual. Relative absorbance was measured under spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, USA). The content of pyruvate, lactate, and ATP were calculated according to the product manual.

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences were analyzed by Student’s t test (two groups). For multiple group comparisons, ANOVA (analysis of variance) was used for comparisons. Tukey’s test was used as the post hoc test after ANOVA text. Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test analyzed the overall survival. The threshold for statistical significance was p < 0.05. Data were presented as the means ± standard deviation (SD). All data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS Inc, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (CA, USA).

Results

USP36 is high expressed in breast cancer and is closely related to the poor prognosis of patients

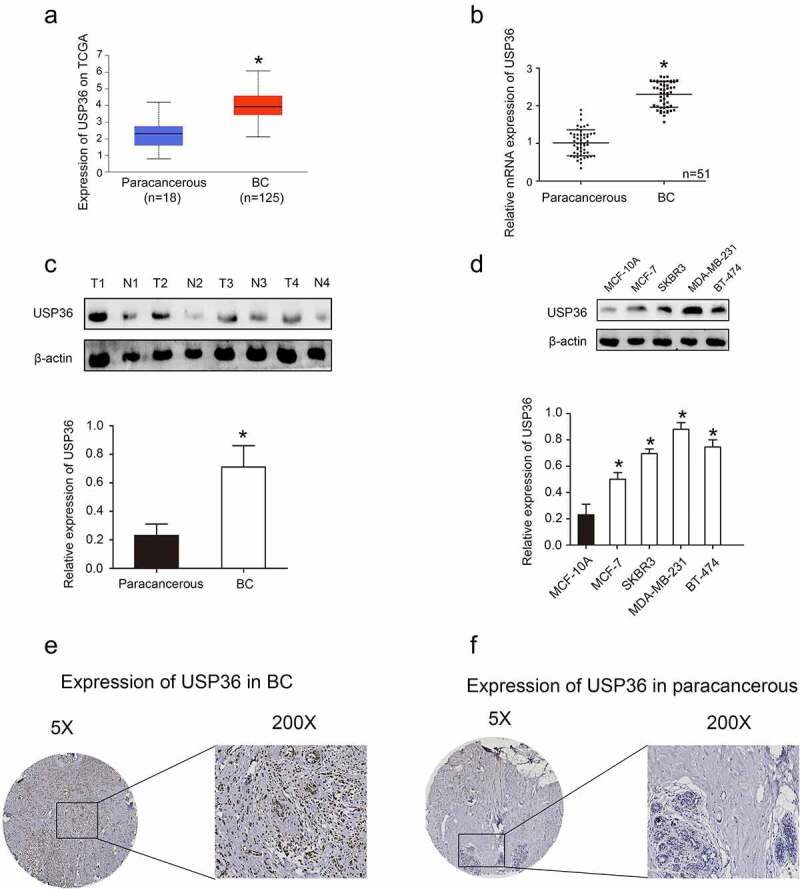

We first analyzed the expression of USP36 through the TCGA database and found that USP36 is high expressed in breast cancer tumor tissues (Figure 1(a)). The results of high expression of USP36 in breast cancer tissues were also verified by RT-qPCR (Figure 1(b)). WB results also showed that USP36 was highly expressed in breast cancer tumor tissues and cell lines (Figure 1(c,d)). Immunohistochemistry also confirmed the above results (Figure 1(e,f)).

Figure 1.

The expression of USP36 in breast cancer samples and cell lines. (a) the mRNA expression of USP36 in TCGA database. (b) the mRNA expression of USP36. (c) the protein expression of USP36 in breast cancer samples. (d) the protein expression of USP36 in breast cancer cell lines. (e) Immunohistochemical analysis of USP36 expression in breast cancer. (f) Immunohistochemical analysis of USP36 expression in paracancerous tissue. *P < 0.05.

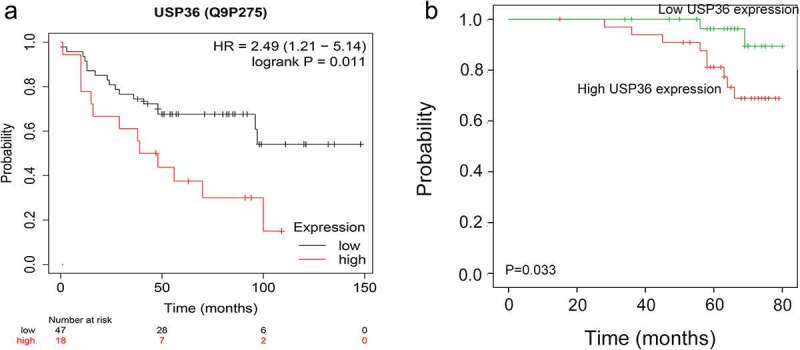

Bioinformatics database analysis finds that breast cancer patients with high USP36 expression have poor prognosis (Figure 2(a)). Through the follow-up of the collected clinical breast cancer patients, it was found that the overall survival rate of breast cancer patients with high USP36 expression was significantly lower than that of patients with low USP36 expression (Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Analysis of USP36 and poor prognosis of breast cancer patients. (a) Relationship between the expression of USP36 and the prognosis of breast cancer patients in TCGA database. (b) Relationship between the expression of USP36 and the prognosis of breast cancer patients.

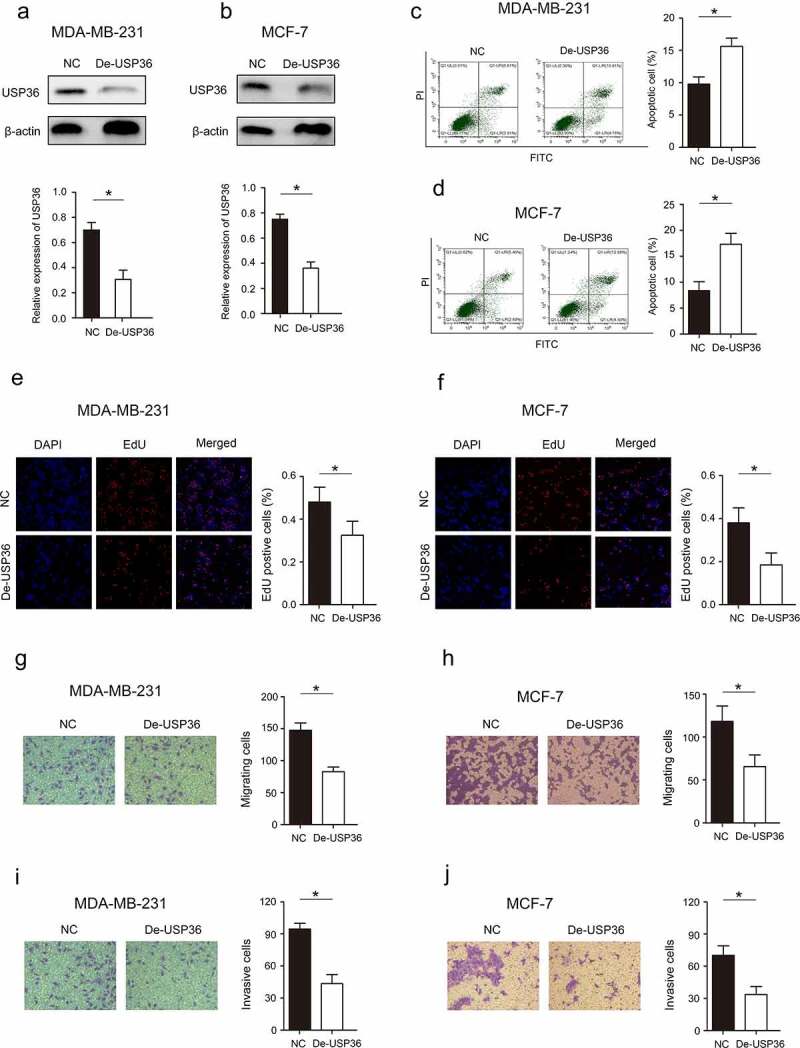

Reducing the expression of USP36 inhibits the proliferation, invasion, migration and promotes apoptosis of breast cancer cells

According to the previous experimental results, we reduced the expression of USP36 (Figure 3(a,b)), and further analyzed the effect of USP36 on the biological behavior of breast cancer. Results from flow cytometry assay demonstrated that reducing the expression of USP36 elevated the cell apoptotic rate of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines (Figure 3(c,d)). Reducing the expression of USP36 significantly inhibited cell proliferation measured by EdU assays in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines (Figure 3(e,f)). Moreover, cell mobility and invasion ability of MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 with reduced USP36 expression was obviously impaired measured by transwell assays (Figure 3(g–j)).

Figure 3.

Effects of USP36 on the biological behavior of breast cancer cells. (a) the protein expression of USP36 in MD-MBA-231 cells. (b) the protein expression of USP36 in MCF-7 cells. (c) Flow cytometry assay to analyze the effect of USP36 on apoptosis in MD-MBA-231 cells. (d) Flow cytometry assay to analyze the effect of USP36 on apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. (e) EdU assay to detect the effect of USP36 on proliferation in MD-MBA-231 cells. (f) EdU assay to detect the effect of USP36 on proliferation in MCF-7 cells. (g) Transwell assay to detect the effect of USP36 on MD-MBA-231 cell migration. magnification, x200. (h) Transwell assay to detect the effect of USP36 on MCF-7 cell migration. magnification, x200. (i) Transwell assay to detect the effect of USP36 on MD-MBA-231 cell invasion. magnification, x200. (j) Transwell assay to detect the effect of USP36 on MCF-7 cell invasion. magnification, x200. *P < 0.05.

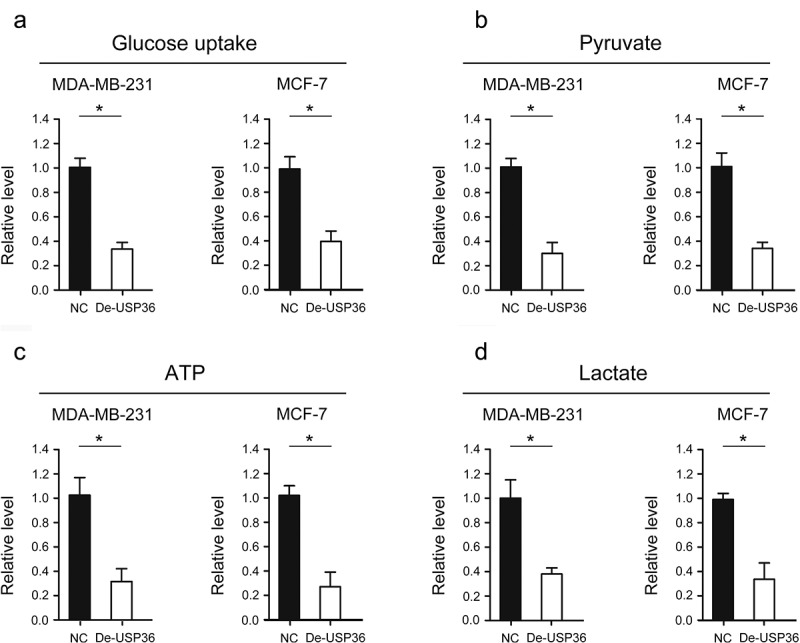

Reducing the expression of USP36 impedes the energy metabolism by restraining the glycolysis in breast cancer

Breast cancer cells have been found to have rearrangement of energy metabolism, which provides the material and energy basis for the malignant growth of tumor cells [19]. Therefore, we analyzed whether USP36 has a regulatory effect on energy metabolism in breast cancer. The level of glucose uptake was tested, and we found that the level of glucose uptake was significantly decreased after reducing the expression of USP36 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Figure 4(a)). In addition, we tested the level of related metabolites in pyruvate, lactate, and the production of ATP. The results revealed that the level of pyruvate, lactate, and the production of ATP were all significantly decreased after reducing the expression of USP36 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Figure 4(b–d)).

Figure 4.

USP36 impedes energy metabolism in breast cancer cells. (a) the effects of USP36 on glucose uptake of MD-MBA-231 and MCF-7 cells. (b) the effects of USP36 on pyruvate of MD-MBA-231 and MCF-7 cell. (c) the effects of USP36 on ATP of MD-MBA-231 and MCF-7 cells. (d) the effects of USP36 on lactate of MD-MBA-231 and MCF-7 cell. *P < 0.05.

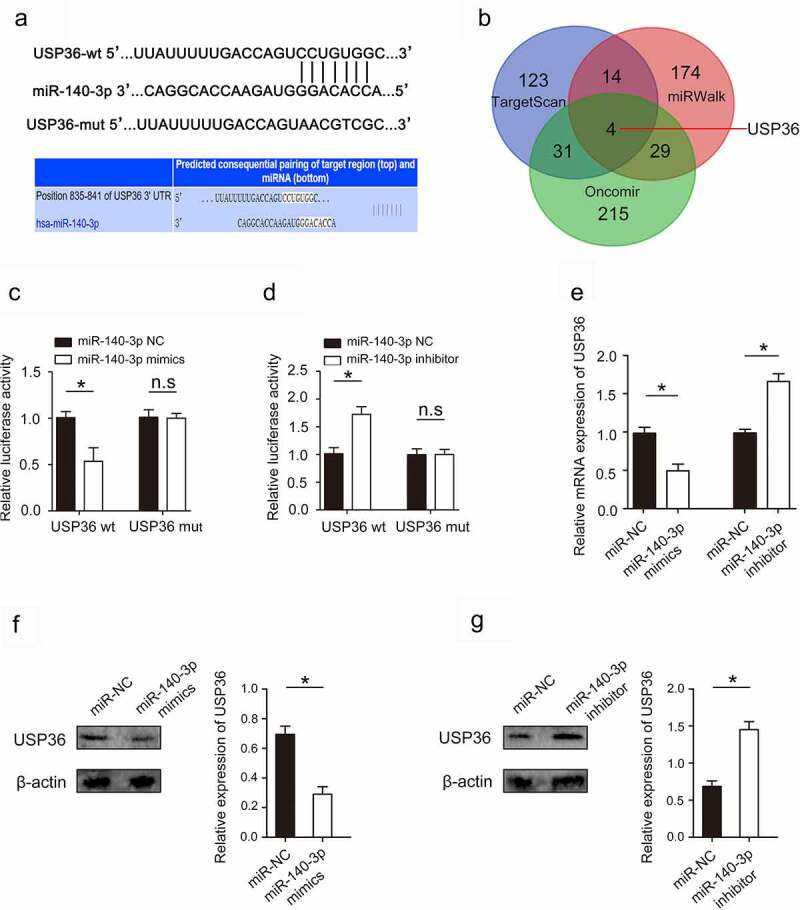

Verification of USP36 as a target gene of miR-140-3p and USP36 downregulation by miR-140-3p

A large number of studies have confirmed that miRNA has a significant regulatory effect on gene expression [20]. Is the expression of USP36 also regulated by miRNA in breast cancer? TargetScan, miRWalk and Oncomir databases identified USP36 as a potential target of miR-140-3p (Figure 5(a,b)). Dual luciferase reporter gene assay results showed that co-transfection of miR-140-3p mimics significantly inhibited luciferase activity in cells co-transfected with Wt USP36 3’-UTR (Figure 5(c)). In addition, co-transfection of miR-140-3p inhibitor significantly increased luciferase activity in cells transfected with Wt USP36 3’-UTR. (Figure 5(d)). RT – qPCR and western blot assays revealed that miR-140-3p overexpression significantly reduced USP36 expression (Figure 5(e–g)) These results suggest that miR-140-3p directly targets and downregulates USP36.

Figure 5.

miR-140-3p targets and downregulates USP36. (a) Binding sites and corresponding mutant sites of miR-140-3p and USP36 3’ UTR. (b) Venn diagram displaying miR-140-3p computationally predicted to target USP36 by TargetScan, miRwalk, and Oncomir databases. (c) Dual luciferase activity assay was performed by co-transfection of luciferase reporter containing USP36 3’ UTR or the mutant reporter with miR-140-3p mimics. (d) Dual luciferase activity assay was performed by co-transfection of luciferase reporter containing USP36 3’ UTR or the mutant reporter with miR-140-3p inhibitor. (e) the effect of miR-140-3p on USP36 mRNA expression. (f, g) the effect of miR-140-3p on USP36 protein expression. *P < 0.05.

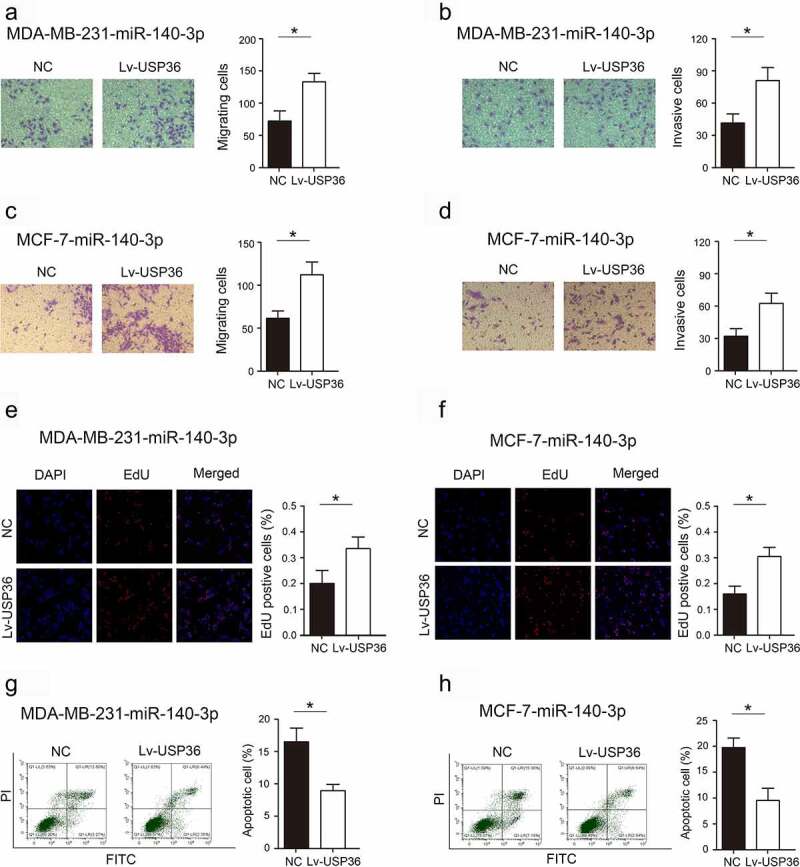

miR-140-3p exerts its biological function in breast cancer by regulating the expression of USP36

We examined the expression of miR-140-3p in breast cancer and cell lines, and found that miR-140-3p was lowly expressed in breast cancer and cell lines (Supplementary Figure S1). Further, we analyzed whether miR-140-3p affects its biological function by regulating the expression of USP36. Increasing the expression of USP36 significantly abolished the inhibitory effects of increasing the expression of miR-140-3p on proliferation, migration and invasion in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Figure 6(a–f)). Moreover, increasing the expression of USP36 significantly abolished the promoting effects of increasing the expression of miR-140-3p on apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells (Figure 6(g,h)). To further verify the effect of USP36/PKM2 regulatory axis on the biological behavior of breast cancer cells, we overexpressed PKM2 in breast cancer cells with USP36 suppression. The results showed that overexpression of PKM2 could restore the malignant biological behavior of breast cancer that was inhibited by USP36 (Supplementary Figure S2). More importantly, we overexpressed PKM2 in breast cancer cells after overexpressing miR-140-3p. The results indicated that the malignant biological behavior of breast cancer cells inhibited by miR-140-3p was restored (Supplementary Figure S3). These results confirm that miR-140-3p regulates the malignant biological behavior of breast cancer cells by regulating the USP36/PKM2 signaling axis.

Figure 6.

Effects of miR-140-3p through USP36 on the biological behavior of breast cancer. (a) Transwell assay to detect the effect of miR-140-3p through USP36 on MD-MBA-231 cell migration. magnification, x200. (b) Transwell assay to detect the effect of miR-140-3p through USP36 on MD-MBA-23 cell invasion. magnification, x200. (c) Transwell assay to detect the effect of miR-140-3p through USP36 on MCF-7 cell migration. magnification, x200. (d) Transwell assay to detect the effect of miR-140-3p through USP36 on MCF-7 cell invasion. magnification, x200. (e) EdU assay to detect the effect of miR-140-3p through USP36 on proliferation in MD-MBA-231 cells. (f) EdU assay to detect the effect of miR-140-3p through USP36 on proliferation in MCF-7 cells. (g) Flow cytometry assay to analyze the effect of miR-140-3p through USP36 on apoptosis in MD-MBA-231 cells. (h) Flow cytometry assay to analyze the effect of miR-140-3p through USP36 on apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. *P < 0.05.

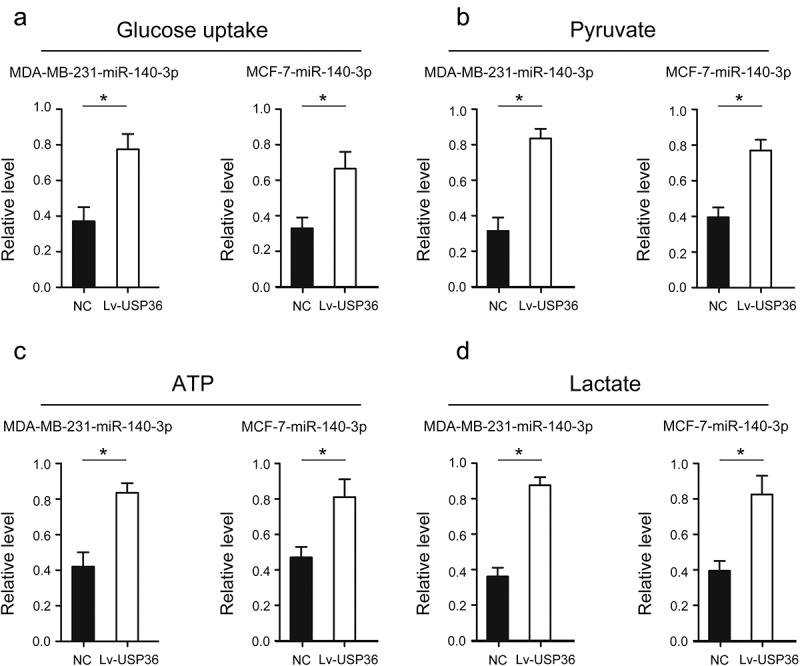

miR-140-3p affects glycolysis and energy metabolism in breast cancer by regulating the expression of USP36

We found that the level of glucose uptake was significantly increased after increased the expression of USP36 in MDA-MB-231- miR-140-3p and MCF-7- miR-140-3p cells (Figure 7(a)). In addition, the level of pyruvate, lactate, and the production of ATP were all significantly increased after increased the expression of USP36 in MDA-MB-231- miR-140-3p and MCF-7- miR-140-3p cells (Figure 7(b–d)).

Figure 7.

Effects of miR-140-3p through USP36 on energy metabolism in breast cancer cells. (a) the effects of miR-140-3p through USP36 on glucose uptake of MD-MBA-231 and MCF-7 cells. (b) the effects of miR-140-3p through USP36 on pyruvate of MD-MBA-231 and MCF-7 cell. (c) the effects of miR-140-3p through USP36 on ATP of MD-MBA-231 and MCF-7 cells. (d) the effects of miR-140-3p through USP36 on lactate of MD-MBA-231 and MCF-7 cell. *P < 0.05.

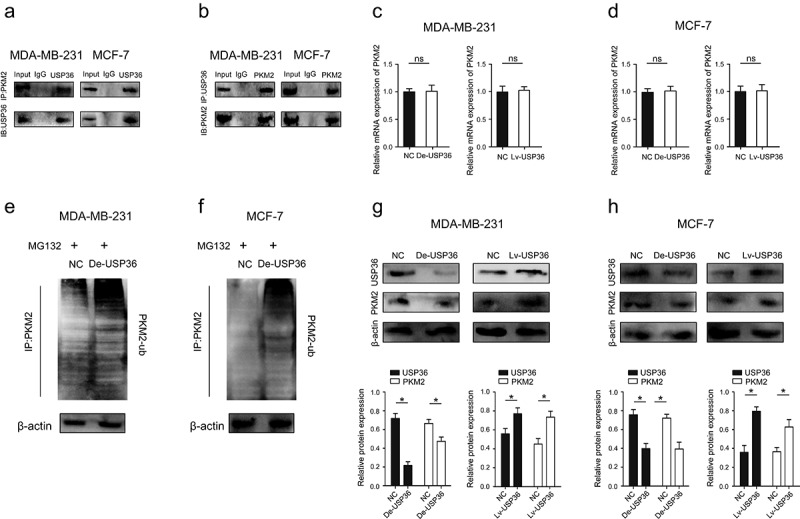

USP36 binds to PKM2 and regulates its expression through ubiquitination and affects

The key of energy metabolism of tumor cells is Warburg effect, and PKM2 is the key protein of Warburg effect [21]. Tumor cells often have higher expression levels of PKM2, thus promoting the Warburg effect to provide various substances and energy metabolites for the malignant growth of tumors [22]. The relationships between USP36 and PKM2 were verified by using reciprocal coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments carried out in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells, respectively. The results confirmed the interaction between endogenous USP36 and PKM2 (Figure 8(a,b)). While, we did not see changes in the mRNA expression of PKM2 after changing the expression of USP36 (Figure 8(c,d)).

Figure 8.

USP36 regulates the expression of PKM2 through ubiquitination. (a) the Co-IP experiments showed that USP36 interacted with PKM2 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines. (b) the Co-IP experiments showed that USP36 interacted with PKM2 in MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cell lines. (c) the mRNA expression of PKM2 in MDA-MB-231. (d) the mRNA expression of PKM2 in MCF-7. (e) the levels of ubiquitinated PKM2 proteins (PKM2-ub) were examined by western blot with anti-ubiquitin antibody in MDA-MB-231 cells. (f) the levels of ubiquitinated PKM2 proteins (PKM2-ub) were examined by western blot with anti-ubiquitin antibody in MCF-7 cells. (g) the protein expression of USP36 and PKM2 in MDA-MB-231. (h) the protein expression of USP36 and PKM2 in MCF-7. *P < 0.05.

USP36 plays a role in deubiquitination, and ubiquitination degrades the proteins translated by genes [23]. Therefore, we were concerned whether USP36 played a role in regulating the ubiquitination of PKM2. The ubiquitination levels of PKM2 were both increased in the MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells after decreasing the expression of USP36, which suggests that USP36 can prevent PKM2 from entering the ubiquitination degradation process (Figure 8(e,f)). Importantly, increasing the expression of USP36 significantly promoted the expression of PKM2, while inhibiting the expression of USP36 significantly inhibited the expression of PKM2 (Figure 8(g,h)). The above results suggest that USP36 changes PKM2 protein expression through ubiquitination.

Discussion

Warburg effect is that the main mode of ATP production in tumor cells changes from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation of glucose to aerobic glycolysis [24]. Its essence is the rearrangement of energy metabolism in tumor cells. Pyruvate kinase (PKM2), the final rate limiting enzyme of glycolysis, is the key enzyme in the Warburg effect [25]. It can catalyze the transfer of phosphoenolpyruvate to adenosine diphosphate to generate ATP [26]. High expression of PKM2 helps to make carbon atoms bind to bioactive substances more quickly, and promotes glycolytic intermediates to generate energy quickly and flow into collateral pathways [27]. It can synthesize nucleic acids, amino acids and lipids without accumulating reactive oxygen species and provide a variety of necessary energy and metabolic substances for malignant growth of breast cancer cells [28]. In breast cancer, PKM2 controls the expression of survivin by phosphorylating c-myc at the ser-62 site, thereby regulating the proliferation, migration and tamoxifen resistance of breast cancer cells [29]. In rectal cancer, FOXM1D binds to tetramers of PKM2 and assembles heterooctamers, inhibiting the metabolic activity of PKM2, thereby promoting glycolysis in tumor cells [30]. Furthermore, FOXM1D interacts with PKM2 and NF-κB and induces their nuclear translocation with the help of nuclear transporter importin 4, which subsequently enhances VEGFA transcription [30]. Increased VEGFA is secreted extracellularly by exosomes and promotes tumor angiogenesis [30]. Our results are consistent with previous studies, and we further found that USP36 regulates the ubiquitination level of PKM2, thereby affecting its protein expression, and regulates the glycolytic process of breast cancer cells through Warburg effect.

The dysfunction of miRNAs initiates a variety of malignant biological behaviors that promote tumors [20]. When the miRNA is loaded into the RNA induced silencing complex, the miRNA recognizes the binding site on the 3 ’- UTR of the target gene mRNA through its seed sequence (nucleotides 2–8 at the 5-terminal), and carries RISC to play the role of regulating gene expression [31]. There are three main effects of miRNAs: transcriptional inhibition, mRNA cleavage and mRNA degradation [32]. The function of miRNAs mainly depends on the above-mentioned methods to inhibit the expression of downstream genes and weaken or eliminate the function of downstream genes [33]. Studies have shown that the function of the signaling pathway is mainly exerted by effectors, and miRNAs can change the expression of key effectors in the signaling pathway through the regulation of target genes and affect the normal function of the signaling pathway [34]. Chen et al. demonstrated that miR-140-3p regulates the expression of downstream target gene BCL-2 and regulates BECN1-induced autophagy and tumor metastasis through BCL-2 in gastric cancer [35]. In breast cancer, circ_0008039 binds to miR-140-3p and regulates its expression, and further exerts biological functions of inhibiting tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion and glycolysis through the downstream target gene SKA2 [36]. Our results indicate that USP36 is highly expressed in breast cancer tumor tissues, and its expression level is significantly correlated with poor prognosis of patients. Mechanistically, miR-140-3p regulates the expression of USP36, and affects the protein expression of PKM2 through the ubiquitination of PKM2 by USP36, and changes the glycolysis and adverse biological processes of breast cancer cells through the Warburg effect.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82100655), the 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (No. ZYJC18018), the Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan province, China (2022YFQ0003), West China Hospital, Sichuan University (21HXFH011), Chengdu Science and Technology Bureau (2019-YF05-01082-SN), Key research and development projects of Sichuan Science and Technology Department (22ZDYF1209)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethics statement

Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan university.

Data availability statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2022.2139554

References

- [1].Britt KL, Cuzick J, Phillips KA.. Key steps for effective breast cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(8):417–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Farhadi P, Yarani R, Valipour E, et al. Cell line-directed breast cancer research based on glucose metabolism status. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;146:112526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Vaupel P, Multhoff G. Revisiting the Warburg effect: historical dogma versus current understanding. J Physiol. 2021;599(6):1745–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Spencer NY, Stanton RC. The Warburg effect, lactate, and nearly a century of trying to cure cancer. Semin Nephrol. 2019;39(4):380–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tekade RK, Sun X. The Warburg effect and glucose-derived cancer theranostics. Drug Discov Today. 2017;22(11):1637–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shulman RG, Rothman DL. The glycogen shunt maintains glycolytic homeostasis and the Warburg effect in cancer. Trends Cancer. 2017;3(11):761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nava GM, Madrigal Perez LA. Metabolic profile of the Warburg effect as a tool for molecular prognosis and diagnosis of cancer. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2022;22(4):439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lebelo MT, Joubert AM, Visagie MH. Warburg effect and its role in tumourigenesis. Arch Pharm Res. 2019;42(10):833–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Unterlass JE, Curtin NJ. Warburg and Krebs and related effects in cancer. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2019;21:e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kozal K, Jóźwiak P, Krześlak A. Contemporary perspectives on the Warburg effect inhibition in cancer therapy. Cancer Control. 2021;28:10732748211041243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].MA M. Ubiquitination: friend and foe in cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;101:80–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sun T, Liu Z, Yang Q. The role of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in cancer metabolism. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Deng L, Meng T, Chen L, et al. The role of ubiquitination in tumorigenesis and targeted drug discovery. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zou T, Lin Z. The involvement of ubiquitination machinery in cell cycle regulation and cancer progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):5754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hu X, Wang J, Chu M, et al. Emerging role of ubiquitination in the regulation of PD-1/PD-L1 in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Ther. 2021;29(3):908–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ryu H, Sun XX, Chen Y, et al. The deubiquitinase USP36 promotes snoRNP group SUMOylation and is essential for ribosome biogenesis. EMBO Rep. 2021;22(6):e50684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yan Y, Xu Z, Huang J, et al. The deubiquitinase USP36 Regulates DNA replication stress and confers therapeutic resistance through PrimPol stabilization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(22):12711–12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liu K, Li F, Han H, et al. Parkin regulates the activity of pyruvate kinase M2. Biol Chem. 2016;291(19):10307–10317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zhang D, Xu X, Ye Q. Metabolism and immunity in breast cancer. Front Med. 2021;15(2):178–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hill M, Tran N. miRNA interplay: mechanisms and consequences in cancer. Dis Model Mech. 2021;14(4):dmm047662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang Z, Deng X, Liu Y, et al. PKM2, function and expression and regulation. Cell Biosci. 2019;9(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].He X, Du S, Lei T, et al. PKM2 in carcinogenesis and oncotherapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8(66):110656–110670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].DeVine T, Sears RC, Dai MS. The ubiquitin-specific protease USP36 is a conserved histone H2B deubiquitinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;495(3):2363–2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Vaupel P, Schmidberger H, Mayer A. The Warburg effect: essential part of metabolic reprogramming and central contributor to cancer progression. Int J Radiat Biol. 2019;95(7):912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chen M, Liu H, Li Z, et al. Mechanism of PKM2 affecting cancer immunity and metabolism in tumor microenvironment. J Cancer. 2021;12(12):3566–3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wiese EK, Hitosugi T. Tyrosine kinase signaling in cancer metabolism: pKM2 paradox in the Warburg effect. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zam W, Ahmed I, Yousef H. The Warburg effect on cancer cells survival: the role of sugar starvation in cancer therapy. Curr Rev Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2021;16(1):30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].van Niekerk G, Engelbrecht AM. Role of PKM2 in directing the metabolic fate of glucose in cancer: a potential therapeutic target. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2018;41(4):343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yu P, Li AX, Chen XS, et al. PKM2-c-Myc-Survivin cascade regulates the cell proliferation, migration, and tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:550469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Zhang W, Zhang X, Huang S, et al. FOXM1D potentiates PKM2-mediated tumor glycolysis and angiogenesis. Mol Oncol. 2021;15(5):1466–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sun Z, Shi K, Yang S, et al. Effect of exosomal miRNA on cancer biology and clinical applications. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Petri BJ, Klinge CM. Regulation of breast cancer metastasis signaling by miRnas. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39(3):837–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ali Syeda Z, Langden SSS, Munkhzul C, et al. Regulatory mechanism of MicroRNA expression in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5):1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].He B, Zhao Z, Cai Q, et al. miRNA-based biomarkers, therapies, and resistance in cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(14):2628–2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hen J, Cai S, Gu T, et al. MiR-140-3p Impedes gastric cancer progression and metastasis by regulating BCL2/BECN1-mediated autophagy. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:2879–2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Dou D, Ren X, Han M, et al. Circ_0008039 supports breast cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and glycolysis by regulating the miR-140-3p/ska2 axis. Mol Oncol. 2021;15(2):697–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.