Abstract

At the end of 2019, the world began to fight the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2. Many vaccines have quickly been developed to control the epidemic, and with the widespread use of vaccines globally, several vaccine-related adverse events have been reported. This review mainly focused on COVID-19 vaccination-associated thyroiditis and summarized the current evidence regarding vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis, silent thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, and Graves’ orbitopathy. The main clinical characteristics of each specific disease were outlined, and possible pathophysiological mechanisms were discussed. Finally, areas lacking evidence were specified, and a research agenda was proposed.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, vaccine, subacute thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, Hashimoto thyroiditis, painless thyroiditis, vaccination, thyroiditis

Introduction

After the emergence of a new coronavirus variant in China, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), several vaccines have been rapidly developed in an attempt to immunize and protect populations [1], [2]. After massive vaccination campaigns using diverse types of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, several autoimmune-inflammatory disorders have been reported and linked with vaccines [3]. This review focused on SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced autoimmune and inflammatory thyroid disorders and summarized the current understanding. Furthermore, we addressed the challenges in the clinical management of vaccine-induced thyroid diseases and discussed possible pathophysiological mechanisms. Finally, we determined the knowledge gap and proposed a research agenda.

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis

Postinfectious subacute thyroiditis (SAT), the classical type, is a self-limited inflammatory disorder of the thyroid gland characterized by T-cell-mediated destruction of thyroid follicles and granuloma formation [4]. SAT typically follows an upper respiratory tract infection (2–8 weeks) and is more frequent in young and middle-aged females (F/M ratio: 4/1, the peak age of incidence 40–50 years). Although clear evidence is lacking, several viral infections (such as Enterovirus, Coxsackie, Epstein-Barr, Adenoviruses, Influenza, and SARS-COV-2) in individuals with a certain genetic background (carrying specific HLA alleles) have been suggested to be implicated in the pathogenesis [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Its incidence varies between 12 and 35 cases per 100.000/year; however, seasonal changes in frequency have also been observed, suggesting an incidence related to viral infections [5], [10].

Inflammatory destruction of follicular epithelium is the primary event in the pathophysiology [4]; eventually, uncontrolled release of preformed thyroglobulin, thyroxine, and other iodinated fragments into circulation results in thyrotoxicosis. The clinical picture reflects the disease process. The thyroid gland functions are generally suppressed during this period [5], [6]. Due to the inflammation in the thyroid gland, patients develop neck pain that is initially confined to one lobe, then commonly spreads and involves the whole gland and may radiate to the jaw and ears. Apart from local symptoms, generalized symptoms like malaise, myalgia, fever, and anorexia may also occur. About half of the patients may exhibit signs of thyrotoxicosis, even though commonly mild, due to thyroid hormone release from the destroyed gland. Recovery is typically complete with the waning of inflammation and healing thyroid cells. However, less than 15% of patients may develop permanent thyroid damage, especially those with underlying autoimmune thyroid disease, requiring lifelong hormone replacement [5], [6], [7].

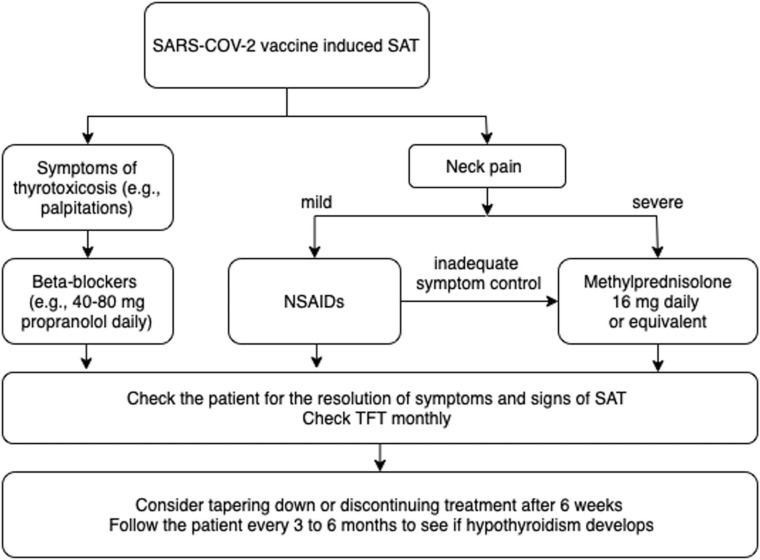

The primary goal of the treatment is symptom control since SAT resolves spontaneously. Although analgesic treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is sufficient to relieve pain in some cases, a course of glucocorticoids is needed in most cases with severe pain and where long-term symptom control is required [11]. Beta-blocking agents are generally adequate to control symptoms related to thyrotoxicosis, and anti-thyroid medications are useless. Although it is not common, patients that have permanent hypothyroidism require levothyroxine treatment in the long term [12].

There is no certain evidence regarding the frequency of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT, and none of the clinical trials evaluating the vaccines’ efficacy and safety have reported this side effect [13], [14]. Besides, too many have been vaccinated worldwide (by January 2023, approximately 13 billion vaccine doses have been administered), and there are few case reports and case series about the subject. In addition, in a prospective study that evaluated SAT cases in a tertiary care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic, only 6 (9%) out of 64 cases were linked to vaccines [15]. Therefore, it seems that SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT is not a common complication.

In the English literature, 98 cases of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis were documented [15], *[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], *[23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61]. The clinical data of all papers were analyzed to examine the demographic characteristics of the patients such as sex and age. In addition, the type and dose of administered vaccines, including mRNA, inactivated, and adenovirus vectored, were examined, as well as the timing of symptom onset after vaccination, main symptoms and signs, laboratory tests such as thyroid function tests and autoantibodies, and imaging characteristics including ultrasonography and scintigraphy. Medical therapies and follow-up results were also evaluated. Table 1 summarizes the clinical features of the reported cases based on the analyzed data [15], *[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], *[23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61].

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of the 98 reported SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis cases.

| Age (median years, range) | 42 (26–82) |

|---|---|

| Gender (n, %) Female Male |

72 (73.5) 26 (26.5) |

| Type of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (n, %) mRNA Inactivated whole-virion Adenovirus- vectored Recombinant protein Non-specified |

54 (55) 28 (29) 13 (13) 1 (1) 2 (2) |

| Vaccination dose (n, %) First Second Non-specified |

54 (55) 43 (44) 1 (1) |

| Time from vaccination to symptom onset (median days, range) | 10 (1–84) |

| Prior history of thyroid disease (n, %) | 12/74 (16) |

| Symptoms associated with thyrotoxicosis (n, %) | 79/95 (83) |

| Symptoms associated with local or systemic inflammation (n, %) | 94/98 (96) |

| Treatment for pain (n, %) Not specified None NSAIDs Glucocorticoids First NSAIDs, then glucocorticoids Low dose (less than or equal to 16 mg methylprednisolone or equivalent) High dose (>16 mg methylprednisolone or equivalent) Non-specified |

4 (5) 10 (9) 48 (49) 23 (24) 13 (13) 19/36 (53) 10/36 (28) 7/36 (19) |

| Time from treatment to remission (median), weeks | 7 (2–20) |

NSAIDs: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

In many aspects, there are similarities between classical and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT. Vaccine-induced SAT is more frequent in young and middle-aged individuals (median age: 42 years, min-max: 26–82 years) as well, and females (3:1) account majority of the patients. No adolescent and child cases have been reported yet. mRNA vaccines were administered to 54 (55%) cases, followed by the inactivated virus to 28 (29%) and the adenovirus vectored to 13 (13%). In one case, SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT developed after recombinant protein vaccine, and the vaccine type was not specified in two [26], [48]. Most patients, 54 (55%), developed SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT after the first dose of the vaccine; however, in 43 (44%), the onset of the SAT symptoms occurred following the second dose. The median time from vaccination to symptom onset was ten days. The time from vaccination to symptom onset was as early as 12 h in one [21], and the longest lag period was 84 days [15], [24].

Only 16% of the subjects reported a personal history of previous thyroid disorder, including four patients with a prior SAT history *[23], [42]. Almost all patients complained about local (neck pain, swelling) or systemic inflammatory symptoms (fatigue, fever, myalgia); however, symptoms associated with thyrotoxicosis were not the rule, and a considerable number of patients (17%) had normal thyroid functions at admission. Even a patient without symptoms was diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT by incidentally discovered pathologic findings in a lobectomy specimen performed for thyroid papillary carcinoma [32]. Anti-thyroid peroxidase antibodies (anti-TPO) were positive only in 10%, and except in concurrent Graves’ disease-SAT cases, TSH receptor antibodies (TRAb) were negative [22], *[23]. Ultrasound examinations revealed characteristic findings of SAT: heterogeneous thyroid gland with ill-defined hypoechoic areas and decreased blood flow. Tracer uptake was found to be reduced in radionuclide studies. The diagnosis was straightforward with consistent clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings, and cytologic analyses were not needed in most.

In a minority of cases (9%), no treatment was required. NSAIDs were sufficient for symptom control in approximately half of the patients; however, oral glucocorticoids were considered for the patients with more severe symptoms, n = 23 (24%). Thirteen cases (13%) were not controlled with NSAIDs, and glucocorticoids were required. In most cases, low-dose glucocorticoid therapy (16 mg methylprednisolone or equivalent) was sufficient. Propranolol was the choice of treatment to control symptoms associated with thyrotoxicosis. Symptom resolution was quick, and the patients were in remission at a median of 7 weeks [9], [10], *[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], *[16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], *[23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]. Recurrence was reported in four cases with boost vaccine doses, and all patients were vaccinated with mRNA vaccines *[23], [36], [37]. Therefore, although evidence is scarce, revaccination seems safe [23]. Only three patients required levothyroxine treatment; however, whether hypothyroidism is temporary was not specified [24], [31], [39]. The approach to patients with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Approach to patients with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT.

Evidence is limited regarding whether there are differences in clinical characteristics between classical and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT. In a direct comparison study conducted in a tertiary endocrinology unit during the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers compared the cardinal features of classical and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT. Accordingly, they found that both SAT types presented similar findings; however, neck pain was milder, and the duration of treatment was shorter in vaccine-induced SAT cases [15]. In line with this study, our analysis showed that the time from the inciting event to the onset of SAT symptoms was shorter in vaccine-induced cases compared to classical SAT (1–2 weeks vs. 2–8 weeks). Although thyrotoxicosis seems more frequent in vaccine-induced SAT (80% vs. 50%), the resolution of symptoms and recovery is faster in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced cases (6–10 weeks vs. 8–16 weeks). Therefore, SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT may present with milder clinical findings. A comparison of subacute thyroiditis clinics according to etiologies was summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of subacute thyroiditis clinic according to etiologies.

| Classical SAT | SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine-induced SAT | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Middle-aged (40–50 years) | Middle-aged (40–50 years) |

| Gender | More frequent in women (3–4:1) | More frequent in women (4:1) |

| Genetic predisposition | HLA B* 35 and HLA C* 04 | HLA B* 35, HLA C* 04 and HLA-A* 11 |

| Onset of symptoms | 2–8 weeks after infection | The first day - 2 weeks after vaccination |

| Symptoms associated with inflammation | Almost all | Almost all |

| Symptoms associated with thyrotoxicosis | ∼50% | ∼80% |

| Severity of inflammation | Mild to moderate | Mild to moderate |

| Severity of thyrotoxicosis | Mild to moderate | Mild to moderate |

| Ultrasound findings | Heterogeneous thyroid gland with ill-defined hypoechoic areas and decreased blood flow | Similar involvement with classical-type SAT In some, involvement in a limited area of the gland |

| Treatment | Few cases can be controlled with NSAIDs Most cases require glucocorticoids |

Most cases can be controlled with NSAIDs Few cases require glucocorticoids |

| Recovery | 8–16 weeks | 4–10 weeks |

| Hypothyroidism | Up to 15% in the long term | %5 in short term No long-term evidence |

NSAIDs: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Other important questions are whether the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT is more frequent for some vaccines than others or whether or not there are clinical differences in the presentation of vaccine-induced SAT according to the vaccine type. There is no comparative data regarding the frequency of vaccine-induced SAT for different vaccines. Limited evidence indicates no differences in patient demographics, symptoms, laboratory and imaging characteristics, and follow-up results between SAT patients induced by different vaccines [52], [62].

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced painless thyroiditis

Painless thyroiditis, a type of autoimmune thyroiditis characterized by thyrotoxicosis caused by inflammatory thyroid gland destruction [5], has rarely been reported following SARS-CoV-2 vaccines [28], [33], [63], [64], [65]. The main characteristics of the seven (five female, two male) reported cases are presented in Table 3. Thyrotoxicosis without neck pain, normal serum markers of inflammation, and low radioiodine uptake levels indicating thyroid gland destruction were used to confirm the diagnosis in each case. The median age of the patients was 38 years (range: 29–59). Symptoms and signs emerged in a median time of 17 days (range: 10–21), whereas two patients were asymptomatic. TPO and thyroglobulin antibodies were positive in three and four cases, respectively. TRAb was negative in all cases. Except for one patient who had concomitant myocarditis, none of the patients received treatment. During a median of 8 weeks (range: 3–20) follow-up, overt hypothyroidism developed in only one patient (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced painless thyroiditis cases in the literature.

| Age & Gender | Vaccine type | Vaccination dose |

Symptoms & Signs |

Time to symptoms/ diagnosis | Thyroid function tests (RR) | Thyroid Abs (RR) | ESR& CRP |

RAIU (RR) | Treatment | Outcome | Hx of AI disease | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nakaizumi, N.[63] | 38, F | BNT162b2 | 1st | Palpitations | 17 days | TSH< 0.01 uIU/mL fT4: 4.08 ng/dL (0.9–1.7) fT3: 7.30 (2.3–4) |

TgAb: 299 IU/mL (<40) TPOAb: 350 IU/mL (<28) TRAb: 1.16 IU/L (<2) |

NA | 1.3% (5–15%) |

None | Mild hypothyroidism at 14th week, normalized TFT in 5 months | NA |

| 59, F | BNT162b2 | 2nd | None | 10 days | TSH= 0.01 mIU/L fT4: 2.35 ng/dL (0.9–1.7) fT3: 5.42 (2.3–4) |

TgAb: 430 IU/mL (<40) TPOAb < 16 IU/mL (<28) TRAb: 0.98 IU/L (<2) |

NA | 0.01% (5–15%) |

None | Normalized TFT in 2 months | NA | |

| Marsukjai, A.[64] | 55, F | Adenovirus-vectored | 2nd | Palpitations, myocarditis | 14 days | TSH: 0.11 uIU/mL fT4: 1.08 ng/dL (0.7–1.5) fT3: 7.37 pg/mL (1.6–4.0) |

All negative | Normal | 3.95% | Low-dose beta blockers | Normalized TFT in 3 weeks | NA |

| Capezzone, M.[65] | 29, F | 1273 mRNA | 1st | Palpitations, weight loss | 3 weeks | TSH: 0.01 uU/mL fT4: 24 pmol/L (12–22) fT3: NA |

All negative | Normal | Low | None | Normalized TFT in 1 month | NA |

| 34, M | 1273 mRNA | 1st | Palpitations, weight loss | 3 weeks | TSH: 0.03 uU/mL fT4: 21.7 pmol/L (12–22) fT3: 5.8 pmol/L (3.1–6.8) |

All negative | Normal | Low | None | Normalized TFT in 1 month | NA | |

| Pujol, A. [28] |

32, M | BNT162b2 | 1st | Palpitations, insomnia | 10 days | TSH: 0.01 uIU/mL fT4: 2.37 ng/dL (0.7–1.5) |

TPOAb: 186 IU/mL (<5.6) TgAb: 42 IU/mL (<4.1) TSI: 0.4 IU/L (<0.7) |

NA | Absent | None | Overt hypothyroidism in 8 weeks | Personal history of T1D |

| Siolos, A. [33] |

39, F | Adenovirus-vectored | NA | None | 3 weeks | TSH< 0.01mIU/mL fT4: 20.47 pmol/L (7.7–17.6) TT3: 2.22 nmol/L (0.8–2.4) |

TPOAb: 777.4 IU/mL (<9) TgAb: 275.3 IU/mL (<4) TRAb: 0.2 IU/L (<1) |

Normal | Low | None | Normalized TFT in 2 months | Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in mother |

F: female, M: male, TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone, fT4: free thyroxine, fT3: free triiodothyronine, TPOAb: thyroid peroxidase antibody, TgAb: thyroglobulin antibody, TRAb: TSH receptor antibody, ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP: C-reactive protein, RAIU: radioactive iodine uptake, TFT: thyroid function tests, RR: reference range, NA: not available. Hx. History. AI: Autoimmune disease

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced Graves’ disease and Graves’ orbitopathy

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced Graves’ disease

The data on SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced Graves’ disease (GD) has been chiefly obtained from case reports and case series. Seventy-nine cases with new-onset and relapsing GD with or without orbital involvement have been attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations thus far. Meanwhile, few clinical studies have been published with significant limitations, and the pathogenetic underpins of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD remains to be elucidated.

The characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD cases in the literature

In the English literature, a total of 79 cases (58 female, 21 male) of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD were documented. The summary of the main characteristics of the cases is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of the characteristics of the reported cases of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD.

| Age (median years, range) | 43 (19–74) |

|---|---|

| Gender (n, %) Female Male |

58 (73.4%) 21 (26.6%) |

| Type of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (n, %) mRNA Adenovirus- vectored Inactivated whole-virion |

63 (79.7%) 14 (17.7%) 2 (2.5%) |

| Vaccination dose (n, %) First Second Third |

35/64 (54.7%) 26/64 (40.6%) 3/64 (4.7%) |

| Time from vaccination to symptom onset (median days, range) | 11.5 (1–63) |

| GD presentation (n, %) New-onset GD Relapsing GD with thyrotoxicosis Relapsing GD with onset GO Worsening GO Concurrent GD&SAT GD following SAT |

52 (65.8%) 13 (16.5%) 2 (2.5%) 8 (10.1%) 3 (3.8%) 1 (1.3%) |

| GO (n, %) | 24 (30.4%) |

| Mild/moderate | 12/24 (50%) |

| Severe | 12/24 (50%) |

| Thyrotoxicosis (n, %) | 70 (88.6%) |

| TRAb (or TSI) positivity (n, %) | 73/78 (93.5%) |

| TPOAb positivity (n, %) | 41/52 (78.8%) |

| TgAb positivity (n, %) | 34/43 (79.0%) |

| Anti-thyroid medication (n, %) | 58/74 (78.4%) |

| Revaccination data (n, %) Available No worsening Worsening |

17/79 (21.5%) 12/17 (70.5%) 5/17 (29.5%) |

| History of thyroid disease (%) | 41/71 (57.7%) |

| Personal or family history of autoimmune diseases (%) | 41/53 (77.3%) |

GD: Graves’ disease, GO: Graves’ orbitopathy, SAT: subacute thyroiditis, TPOAb: thyroid peroxidase antibody, TgAb: thyroglobulin antibody, TRAb: TSH receptor antibody

The median age at GD diagnosis was 43 years (19−74). Male to female ratio in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD cases seems to be higher than that reported for non-vaccine-induced patients (3:1 vs. 5–6:1) [66]. TRAb or thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) was positive in all but four cases *[23], [67], whereas indeterminate and unavailable in one case each [68], [69]. The diagnosis of GD in TRAb-negative patients was based on imaging findings in three cases *[23], [68], whereas the other two already had thyroid eye disease due to pre-existing GD [67]. The remaining patient had hypothyroidism and thyroid eye disease due to Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Thyroid functions and eye findings deteriorated after receiving a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine [69].

Sixty-six percent (n = 52) of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD cases were new-onset [22], *[23], [27], [28], [37], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], *[78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87]. Forty-nine (37 F, 12 M) out of 52 new-onset SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD cases presented within the four weeks after vaccination (94%). Thirteen patients (16.4%) had relapsing GD with deteriorating thyroid function tests [22], [70], [72], [87], [88], [89], whereas ten patients who had previously received or were currently receiving adequate treatment for GD or Graves’ orbitopathy (GO) presented with symptoms and signs of either newly occurring [67], [90] or worsening GO without thyrotoxicosis (euthyroid GO, see below) [67], [69], *[78], [91]. Three patients had concurrent SAT and GD [22], [27], [56], and one developed GD five months after a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT [23].

The mRNA vaccines were the most common cause of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD (n = 63, 79.7%), followed by adenovirus-vectored vaccines (n = 14, 17.7%) (Table 4). Interestingly, only one case of inactivated whole-virion SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD has been reported [70]. She was diagnosed and treated for GD thirteen years ago, had been asymptomatic for twelve years, not knowing her thyroid function status for the last two, and developed symptoms of thyrotoxicosis seven days after the vaccination. The remaining patient, who also received an inactivated whole-virion vaccine, was diagnosed with SAT four days after the vaccination, with negative thyroid autoantibodies, including TRAb. When her neck pain was finally relieved after five months, ultrasonography and scintigraphy findings changed, and TRAb became positive. She was then diagnosed with GD [23].

Thirty-five (44.3%), 26 (32.9%), and 3 (3.8%) patients were diagnosed with GD following the first, second, and booster (third) doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations, respectively. This information was missing in 15 (19%) patients. Revaccination data were available in 17 cases, with a majority (12, 70.5%) having no exacerbations of thyroid functions or GO *[23], [67], [70], [71], *[78], [86]. On the other hand, after receiving a repeat vaccination, four patients developed relapsing thyrotoxicosis [70], [71], [88], and one developed worsening GO [67].

The median time from vaccination to the onset of symptoms was 12 days (range: 1–63), with 87% (n = 69) of the patients experiencing symptoms within four weeks of vaccination. Five patients, however, were asymptomatic [72], [85], [87]. Three asymptomatic patients with new-onset SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD were also diagnosed within four weeks of vaccination [72], [85], [87], whereas the other two with GD relapse were diagnosed later [72]. A total of five patients had severe thyrotoxicosis: thyroid storm was identified in two of them with fever and abdominal pain [75], [85] and atrial fibrillation (AF) in three others [27], [84], [86]. It was reassuring that a 64-year-old female with AF and heart failure had no worsening her condition after receiving SARS-CoV-2 revaccination [86].

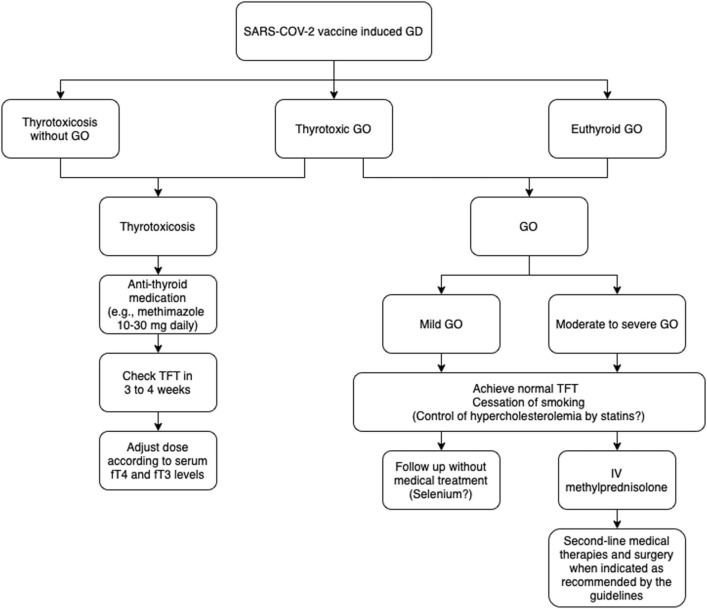

The medical treatment of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD did not differ from non-vaccine-induced GD. Patients received methimazole (n = 33) or carbimazole (n = 23) with median doses of 15 mg (range: 5–80) and 20 mg (range: 2.5–30), respectively in addition to beta-blockers when necessary. Information on the dose of anti-thyroid medication was not available in 15 cases. Patients who needed anti-thyroid medication responded well after a median follow-up of 3 months (range:1–8). There is currently no data on the time to remission for cases of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD that required medical treatment. The approach to patients with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD is summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Approach to patients with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced Graves’ disease and Graves’ orbitopathy.

A positive personal or family history of autoimmune diseases has been recorded in 29 patients (including GD and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) *[23], [67], [69], [70], [71], [77], *[78], [79], [81], [82], [85], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91]. Four patients had multiple autoimmune diseases [67], [77], *[78], [79], and three had a history of autoimmune disease in more than one family member [71], [85], [89]. Patients with multiple autoimmune disorders were not specifically assessed for autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes in the published literature. It is possible that further evaluation could have revealed the presence of such syndromes in these patients, but this was not done as part of the analysis reported in the literature.

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced Graves’ disease with Graves’ orbitopathy

Twenty-four cases (16 F, 8 M) with GO associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD have been recorded. GO was reported in eleven patients with new-onset SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD [69], [70], [71], [72], [74], [75], *[78], twelve with pre-existing GD [67], [69], *[78], [88], [90], [91], and one with concurrent SAT and GD [56]. Three GD patients who had previously been treated with RAI and anti-thyroid medication developed new-onset thyroid orbitopathy while remaining euthyroid (euthyroid GO) after receiving SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations [67], [88], [90]. In nine patients with pre-existing thyroid eye disease associated with GD [67], [69], *[78], [91], and Hashimoto's disease [69], GO worsened after receiving a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

Most SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD cases with GO were administered an mRNA-type SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (21/24, 87.5%), while three received an adenovirus-vectored vaccine. None of the cases were associated with an inactivated whole-virion SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Thirteen patients developed or experienced worsened symptoms of GO after receiving the first dose of the vaccine, while ten patients developed or experienced worsened symptoms of GO after receiving the second dose.

GO either developed or worsened in a median time of 10 days (range: 1–60). Half of all GO cases had severe orbitopathy (clinical activity score ≥ 3), and all twelve received an mRNA-type SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ( Table 5). Severe GO developed in three new-onset SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD cases [69], [70], *[78] and two patients with a GD history but no GO [67], [90]. The remaining patients developed severe GO as their pre-existing thyroid eye disease deteriorated following a SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

Table 5.

Characteristics of the reported cases with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced Graves’ disease and severe orbitopathy.

| Age (years) & Gender |

Type of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine | Vac. dose | Time to symptom onset (days) | GD presentation | Previous treatment history for GD | GO presentation | Previous treatment history for GO | Thyroid function tests | TRAb/ TSI (RR) | Treatment of GO | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubinstein, TJ.[90] | 50, F | BNT162b2 | 1st | 3 | Relapse | RAI in 2010 | New-onset | None | Euthyroid w/ LT4 |

TSI: 2.29 IU/L (<0.55) | Teprotumumab | NA |

| Patrizio, A[91] | 58, F | BNT162b2 | 2nd | 3 | Relapse | RAI in 2020 | Worsening (CAS 3/7→6/10) |

IV MPZ (4.5 g) in 2020 | Euthyroid w/ LT4 |

TRAb: 6.8 IU/mL (<1.5) | Teprotumumab planned | NA |

| 43, M | BNT162b2 | NA | 14 | Relapse | Under MMI treatment | Worsening (CAS 4/7→8/10, exposure keratopathy) |

IV MPZ (6 g) and orbital radiation | Euthyroid w/MMI | TRAb: 20.7 IU/mL (<1.5) | NA | NA | |

| Abeillon-du Payrat, J. [92] |

70, F | mRNA | 2nd | 60 | Relapse | Total thyroidectomy | Worsening | Stable GO after 4 doses of tocilizumab | Euthyroid w/LT4 | TRAb> 40 IU/mL | Tocilizumab | Clinical improvement with 5 doses of tocilizumab, decreased TRAb levels |

| 43, M | 1273 mRNA | 1st | 1 | Relapse | Under CMZ treatment | Worsening (Spontaneous orbital pain and diplopia → Decreased visual acuity after 2nd vaccine dose) | Tocilizumab for GO + DON | Slightly elevated TSH and low fT4 | TRAb negative | Tocilizumab | Clinical improvement with 4 doses of tocilizumab | |

| 73, M | BNT162b2 | 1st | 21 | Relapse | Under CMZ treatment | New-onset | None | Euthyroid | TRAb negative | IV MPZ | Clinical improvement with a total dose of 3 g IV MPZ | |

| 48, M | 1273 mRNA | 2nd | 30 | Relapse | Total thyroidectomy | Worsening | IV glucocorticoids and orbital decompression | TSH< 0.001 mIU/L fT4: 21 pmol/L |

TRAb: 28 IU/L | IV MPZ 3 g → Orbital decompression → Teprotumumab | Improvement in GO after 1st dose of teprotumumab decreased TRAb after 3 months | |

| Mohamed, A.[78] | 50, M | BNT162b2 | 2nd | 21 | Relapse | Total thyroidectomy | Worsening (CAS 4/10 → 7/10) |

Total thyroidectomy | Euthyroid w/LT4 | TSI: 4.45 IU/L (<1.75) | IV MPZ (4.5 g) → Tocilizumab x3 → Teprotumumab x8 | Excellent overall response in 6 months |

| 71, F | 1273 mRNA | 2nd | 3 | New-onset | Primary hypothyroidism for 40 years, euthyroid w/LT4 | New-onset (DON in 6.5 months) | None | TSH: Undetectable fT4: 1.4 ng/dL (0.9–1.7) fT3: 3.9 pg/mL (2.3–4.2) |

TSI index: 5.5 (<1.3) | IV MPZ (2 g) → Teprotumumab x4 | Good response in 9 weeks | |

| Park, KS. [69] |

66, F | 1273 mRNA | 2nd | 21 | Relapse | RAI | Worsening (CAS: 6) |

Orbital decompression+ strabismus surgery 20 yrs ago | TSH: 0.04 mIU/L fT4: 1.7 ng/dL |

TRAb: 5.5 IU/L TSI: 3.9 IU/L |

Teprotumumab | GO improved in 5 months |

| 53, F | BNT162b2 | 1st | 1 | New-onset | None | New-onset | None | Euthyroid w/MMI | TSI: 3.21 IU/L | Teprotumumab | GO improved in 8 months | |

| Bostan, H.[70] | 51, F | BNT162b2 | 2nd | 4 | New-onset | None | New-onset (CAS: 3) |

None | TSH< 0.01 mIU/L fT4:3.7 ng/dL (0.9–1.7) fT3: 12.6 ng/L (2–4.4) |

TRAb: 5.04 IU/L (<1.5) | Total thyroidectomy | Orbitopathy improved after thyroidectomy |

F: female, M: male, GD: Graves’ disease, GO: Graves’ orbitopathy, SARS-CoV-2: TRAb: TSH receptor antibody, DON: dysthyroid optic neuropathy, LT4: levothyroxine. IV MPZ: intravenous methylprednisolone. MMI: methimazole, CMZ: carbimazole, TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone, TSI: thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin, fT4: free thyroxine, fT3: free triiodothyronine. CAS: clinical activity score, RAIU: radioactive iodine. RR: reference range, NA: not available.

Despite differences in laboratory measurement methods, when compared, patients with GO had insignificantly higher TRAb levels than those without (median 9.0 IU/L, IQR: 3.0–34.0 vs. 5.4 IU/L, IQR: 3.5–9.4; p = 0.78). However, TRAb levels were not higher in patients with severe GO than in non-severe GO (p = 0.64). Furthermore, patients with severe GO were not current smokers [69], *[78], [90], or their smoking status was not reported [67], [70]. A history of radioiodine treatment was present in two cases [69], [90].

The treatment modalities and response to treatment in patients with severe GO are presented in Table 5. Five of twelve patients have presented with new-onset severe GO following an mRNA-type SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Two patients were given intravenous methylprednisolone as first-line treatment, followed by teprotumumab in one *[78], [92]. Tocilizumab or teprotumumab was given as first-line treatment in two [69], [90], which contradicts recent guidelines [93]. The remaining patient underwent total thyroidectomy [70]. Seven patients developed worsening of their pre-existing GO following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Patients' previous treatment modalities and the treatment they received following a relapse of GO varied widely (Table 5). All patients responded well to treatment. The approach to patients with GO associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD is summarized in Fig. 2. Revaccination data was available for only one patient whose GO worsened after receiving a second dose of the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine [67].

SARS-COV-2 vaccine-induced GD in older patients

Twelve patients were above the age of 60 when diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD [22], [27], [67], [69], [72], [75], *[78], [85], [86], [87]. The median time from vaccination to the onset of symptoms was insignificantly longer than the younger patients (14 days, IQR: 5.7–21 and 10 days, IQR: 5–21, p = 0.34, respectively). Weight loss was present in four [22], [27], *[78], AF in two [27], [86], and a thyroid storm clinic with dyspnea, fever, and abdominal pain in one patient [75]. Two patients were asymptomatic [72], [85].

GO was detected in five patients: as new-onset in three [67], [75], *[78] and as worsening of pre-existing GO in two [67], [69]. Four patients required specific treatment for severe GO (methylprednisolone, tocilizumab, or teprotumumab, either as single or sequential therapy) [67], [69], *[78]. The remaining patient developed GO later in the course, and treatment was not specified [75]. Patients older than 60 years had a higher percentage of GO than younger patients (41.7% vs. 28.3%). In addition, the older group had a higher rate of severe GO (defined as clinical activity score ≥ 3) compared to the younger group among all cases of GO (4/5, 80% vs. 8/19, 42%). Despite differences in laboratory measurement methods, when compared, TRAb levels were similar in older and younger patients (median 5.85 IU/L, IQR: 3.75–24.95 vs. 5.77 IU/L, IQR: 3.17–12.33, respectively). Two older patients with available data who had previously been diagnosed with GO were re-vaccinated, but there was no observed exacerbation of GO or thyrotoxicosis after revaccination [86].

Overall, data from case reports and series show that the clinical characteristics of new-onset SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD are highly comparable to those not caused by vaccination. However, the male proportion may be higher. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination may result in a relapse in patients with a history of GD, manifested as thyrotoxicosis or new-onset orbitopathy. In patients with a history of severe GO, thyroid eye disease may worsen, necessitating re-treatment with intravenous glucocorticoids, monoclonal antibodies, and even surgery. Nearly all cases have been related to mRNA and adenovirus-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Most patients experienced symptoms within four weeks of receiving the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, which was usually manageable. However, older patients have been reported to present with AF and thyroid storm clinic. Severe orbitopathy has also been frequent in older patients. Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD with anti-thyroid medications could be initiated as usual (Fig. 2). It is currently unknown whether a shorter duration of anti-thyroid medication would be sufficient for GD remission. The management strategies utilized for severe cases of new-onset and relapsing GO have been varied. There is no current evidence to support any other strategies for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GO cases other than those recommended in the guidelines, and we believe it is best to follow them when available [93]. Long-term follow-up data are lacking, and there is still a need for more information on the safety of revaccinations. Furthermore, because most cases did not report prior SARS-CoV-2 infections, the impact could not be determined, but it remains a possibility.

Insights from clinical studies

The effects of SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations on thyroid function tests and thyroid autoantibodies were investigated in a few studies. Lui et al. reported in their prospective study that vaccination with two doses of mRNA (n = 125) or inactivated (n = 86) vaccines have no clinically significant effect on thyroid functions and autoantibodies after eight weeks. However, there was a slight decrease in fT3 and a slight increase in fT4, anti-TPO, and anti-thyroglobulin antibody titers. Participants had no prior history of COVID-19 or thyroid diseases [94]. Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine did not significantly affect thyroid functions or thyroid autoantibodies in another prospective study enrolling over 500 participants. After vaccination, none of the participants with negative TPO or Tg antibodies became positive [95]. Furthermore, a prospective study including 173 subjects reported that inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine had no clinically meaningful effect on thyroid function tests or TRAb titers in GD patients [96]. These studies may shed light on the paucity of new-onset and relapse GD cases associated with inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations. It remains unclear whether SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations increased the incidence of new-onset GD cases. A prospective study of 70 healthy subjects showed that TRAb titers increased 32 weeks after the second dose and four weeks after the third dose of BNT162b2 but remained negative. There were no significant changes in thyroid function tests during the study period [97] Moreover, Wong CH et al. reported that mRNA-type vaccines might be safe in patients with pre-existing GD. In their study, patients with GD (n = 784, 529 vaccinated vs. 255 unvaccinated) had no increased risk of thyroid function deterioration when vaccinated with either an mRNA (BNT162b2) or inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. GD relapse rates were similar among vaccinated and unvaccinated subjects. Even if they had uncontrolled thyrotoxicosis at the time of vaccination (n = 27), there were no cases of thyroid storm following SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations [98].

Overall, few studies have yielded encouraging results on the possible clinical effects of SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations on thyroid functions and autoantibodies in healthy subjects and patients with pre-existing GD. However, it is yet to be determined whether SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations increased the incidence of new-onset GD in the general population or the risk of relapse in patients with a pre-existing GD or GO.

Possible pathophysiological mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced thyroid disorders

SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus, and its genomic organization resembles other coronaviruses. This single-stranded RNA encodes four structural proteins: spike surface glycoprotein (S), membrane protein, envelope protein, and nucleocapsid protein [99]. The S protein interacts with the membrane-bound angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptor for viral fusion, followed by the internalization of the virus-bound ACE2 receptor complex [100]. Thus, the entry of the virus into the cell, which is the critical step for the infection of the cells, is completed. These features make S protein a good candidate for vaccine development.

COVID-19 vaccines comprise SARS-CoV-2 antigens or nucleic acid sequence and trigger the host immune response against the virus. Although many vaccines with different techniques have been developed, three vaccines have been used more frequently worldwide during this pandemic: inactivated-virus, mRNA-based, and adenovirus vectored vaccines [2]. Inactivated virus vaccines are produced by culturing the viruses in vitro and then inactivating them with physical or chemical agents. The inactivated virus cannot interact with host cells; however, it elicits an immune reaction. Typically, these vaccines include whole virus or split viral fragments, and to boost immune response, inactivated vaccines usually require an adjuvant [101], [102]. Aluminum hydroxide is the most widely used adjuvant because it strengthens immune responses and has a favorable side effect profile [2].

The mRNA vaccines, on the other hand, contain a nucleic acid sequence covered by lipid nanoparticles that is translated into a specific viral antigen in vivo, and in the case of SARS-CoV-2, this antigen is the S protein. After injection, mRNA is introduced to recipient cells for translation; S protein is synthesized and induces a potent cellular and humoral immune response [103]. Another type of nucleic acid-based vaccine is the adenovirus-vectored vaccine. gene encoded by the S protein is integrated into a non-toxic virus (usually adenovirus). Once injected, the pathogenic gene produces the S protein, followed by the induction of the immune system and the constitution of a specific immune response to the pathogen [2].

The exact pathogenic mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced thyroid disorders are not clear yet; however, some hypotheses have been proposed.

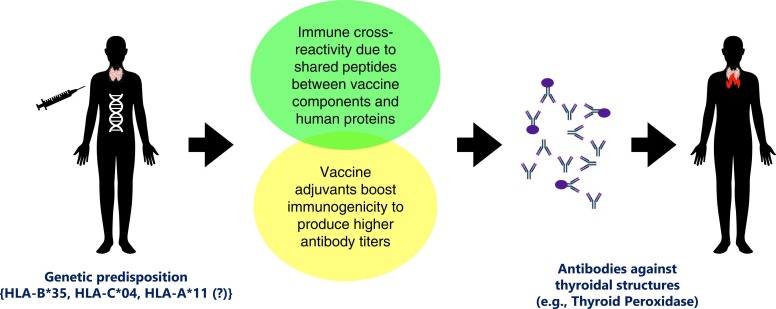

As a potential mechanism: molecular mimicry

The molecular mimicry hypothesis was one of the earliest hypotheses proposed to explain autoimmunity [104]. It is based on the fact that the peptide similarities between infectious pathogens and host proteins may pave the way to developing auto-antibodies in infected subjects. Pathogen antigenic structures should be distinct enough to elicit an immune response, which is then directed at host proteins because pathogen-specific antibody responses would interact with host structures [105]. Immune cross-reactivity may also develop following the vaccinations due to the commonalities between the vaccine's components and human proteins [106]. Despite the lack of direct evidence on its role in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced autoinflammatory diseases, it remains a viable theory supported by some valuable data.

Studies have demonstrated that the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 and certain human proteins share a considerable number of peptides *[107], [108]. While peptide similarities may be linked to clinical manifestations of COVID-19 (e.g., shared peptides with surfactant protein leading to lung involvement), they may also be related to autoimmune events (e.g., shared peptides with thyroid peroxidase leading to autoimmune thyroid destruction) [108], [109]. Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, on the other hand, consist of an inactivated whole-virion or encode for the synthesis of viral S protein to induce an immune response [2]. Antibodies against the S protein formed by polyclonal B cell activation after vaccination may thus cross-react with host antigens, such as TPO, and precipitate thyroid autoimmunity in susceptible subjects. In addition, antibodies against the S protein (common in all vaccine types) displayed higher cross-reactivity to TPO than antibodies against other viral proteins [107].

No study has yet demonstrated a clear cause-effect relationship indicating that molecular mimicry between thyroid antigens and the S protein induces SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-related autoinflammatory thyroid diseases. In addition, only a small percentage of individuals develop autoimmune disorders after receiving a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, lending credence to the notion that molecular mimicry alone is insufficient to induce vaccine-related autoimmunity, but genetic predisposition is necessary.

As a potential mechanism: ASIA syndrome

Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) was first described in 2011 in an attempt to depict the role of environmental factors (adjuvants) as a trigger for autoimmunity in susceptible individuals. Since the establishment of the criteria for ASIA syndrome, numerous cases that met these criteria started to be reported one after the other, including the most recent reports of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced autoimmune events [110].

Adjuvants are substances that, when introduced to the organism, strengthen a specific immune response and cause higher antibody titers, such as those against particular pathogens [111]. For example, aluminum is a common adjuvant frequently used in vaccines to boost immunogenicity and produce higher antibody titers to a specific antigen, including inactivated whole-virion SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. In addition, polyethylene glycol is commonly used in the lipid nanoparticles of RNA-based vaccines, and the adenovirus vectored vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, includes polysorbate 80 as an adjuvant [2]. While it is unclear whether these particular adjuvants are to blame, SARS-CoV-2 vaccines may overstimulate the immune system and cause a clinical picture consistent with ASIA syndrome.

Vera-Lastra et al. and our group reported the first cases of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-related ASIA syndrome, including two patients with GD and three with SAT, respectively *[16], [84], which were followed by many others. Interestingly, only a small number of endocrine autoimmune disorders, including SAT and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, have been attributed to ASIA syndrome before, and GD was not among them [112]. However, under-reporting due to a lack of awareness is likely because physicians might not ask their patients if they had recently received a vaccination if it was not for SARS-CoV-2. In addition, the role of genetic susceptibility to ASIA syndrome, such as in carriers of HLA DRB1 haplotypes, needs further investigation [113]. Another question that needs to be addressed is whether adjuvants increase the likelihood of developing molecular mimicry-related autoimmunity in susceptible subjects by boosting the immune response in the host, resulting in higher autoantibody production.

As a potential mechanism: genetic predisposition

Genetic predisposition may be at the root of pathogenetic underpinnings of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced autoimmune disorders. Because, despite widespread vaccination of over five billion people worldwide, the relative scarcity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced autoimmune disorders gives credibility to the hypothesis that molecular mimicry or adjuvants alone are insufficient to induce vaccine-related autoimmunity, but genetic predisposition is required. For instance, as specific HLA haplotypes are associated with SAT predisposition and clinical severity [114], they may also predispose individuals to SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT. Previous SAT history in some SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT cases, and a report of two sisters who developed SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT a few days after the mRNA vaccine supported this view [18], *[23]. Moreover, we established that the frequencies of HLA-B* 35 and HLA-C* 04 alleles were higher in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT (n = 14) compared with healthy controls (n = 100) and the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT followed a more severe clinical course in individuals homozygous for HLA-B* 35 and HLA-C* 04 [115]. Sahin Tekin et al., on the other hand, found higher frequencies of HLA-B* 35 and HLA-C* 04 alleles in non-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT cases (n = 14) than in vaccine-induced SAT cases (n = 13). They also found an increased frequency of the HLA-A* 11 allele in subjects with SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT, which had never been linked to SAT before, a finding that needs to be supported by additional research [116]. Genetic predisposition, as evidenced by a specific HLA allele, was also encountered in an older patient developing ANCA-associated vasculitis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination [117]. We believe that looking for disease-specific HLA allele presence or other evidence of genetic susceptibility when available and gathering a personal and family history of autoimmune diseases is essential to understanding the pathogenetic mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced autoimmune disorders.

Overall, the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced thyroid disorders are understudied and thus remain unclear. There is a multitude of hypotheses waiting to be tested. Although molecular mimicry and ASIA syndrome in genetically susceptible subjects appear to be plausible explanations ( Fig. 3), they should be supported by further research. On the other hand, reports of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced cases of concurrent or subsequent SAT and GD are intriguing, as they are both unusual and rare occurrences [118]. Because the presence of thyroid autoantibodies has been proposed to be the result of an immune response against thyroid antigens released during SAT due to gland injury, it might be speculated that the release of thyroid antigens during SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT triggered the development of concurrent or future Graves' disease [114]. Furthermore, whether the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein included or encoded by vaccines can directly activate thyroidal ACE2 receptors requires further investigation [119].

Practice points

-

•

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis (SAT), painless thyroiditis, and GD (with or without GO) are rare auto-inflammatory complications of COVID-19 vaccinations. However, considering the mass vaccination, physicians should be aware of these conditions and be able to make a differential diagnosis to treat patients appropriately.

-

•

Demographic characteristics of SAT and GD are similar to non-vaccine related cases: SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT mostly affects young and middle-aged women, whereas vaccine-induced GD is more frequent in men. However, the male-to-female ratio in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD cases might be higher than that of non-vaccine-induced patients.

-

•

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT may occur at any dose of any SARS-CoV-2 vaccine type. However, SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced painless thyroiditis and GD have both been associated with adenovirus vectored or mRNA-type vaccinations, except one GD case emerged after the inactivated vaccine.

-

•

Unlike classical SAT, vaccine-induced SAT usually develops within a few days after antigen exposure. A vast majority of new-onset GD cases also emerged within the four weeks after vaccination.

-

•

Mild local and systemic inflammatory symptoms with mild thyrotoxicosis dominate the clinical picture in SAT patients, and the diagnosis is straightforward after suspicion. Neck pain and elevated serum inflammatory markers help distinguish these patients from those with painless thyroiditis, even though radioactive iodine uptake is low in both. TPO and Tg antibodies may be positive in both painless thyroiditis and GD. Positive TRAb, increased RAIU, and GO can be used to differentiate GD.

-

•

The clinical course of SAT and painless thyroiditis is usually mild. Many patients can be followed without treatment. A short course of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be given to patients with SAT, while few require glucocorticoids, usually in low doses.

-

•

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD can be treated with anti-thyroid medications as the guidelines recommend. There is no evidence to support any other strategies for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD with or without GO than those recommended in the guidelines.

-

•

Older patients with thyrotoxicosis can present with severe symptoms or signs such as atrial fibrillation and heart failure, thus requiring special care.

-

•

Recurrence of SAT and GD with repeat vaccine doses seems to be rare.

-

•

SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced subacute and painless thyroiditis are self-limiting disorders, and recovery is quick and complete. Hypothyroidism is rare. There is currently no data on time to remission for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD cases, nor on whether a shorter duration of anti-thyroid medication would suffice for GD remission.

-

•

Considering the benefits of global vaccination, these adverse events should not discourage physicians from offering vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2, including boost doses.

Research agenda

-

•

The exact incidence of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced thyroid disorders is not known. The frequency of these should be assessed in clinical trials to evaluate the vaccine efficacy and safety.

-

•

The underlying pathogenetic mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced thyroid disorders are understudied. Molecular mimicry, ASIA syndrome, and genetic predisposition are plausible explanations regarding the pathophysiological mechanisms of vaccine-induced inflammatory thyroid disorders; however, the exact mechanisms remain to be elucidated.

-

•

Individuals carrying specific HLA alleles are more susceptible to vaccine-induced thyroid complications. Few studies, only in individuals of certain ethnicities, have evaluated the contribution of HLA alleles to vaccine-induced thyroid disorders. More studies are needed to determine whether similar HLA alleles are responsible for the predisposition to vaccine-induced thyroid disorders in subjects of different ethnicities.

-

•

Although hypothyroidism is a rare complication of vaccine-induced SAT in the short term, there is no evidence regarding the long-term consequences of vaccine-induced SAT. Long-term data is also required to assess the remission and recurrence rates of GD.

-

•

Few prospective clinical studies have examined whether thyroid dysfunction occurs after SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations in healthy adults. More research is required with selected subjects who may be predisposed to thyroid disorders (e.g., carriers of specific HLA alleles or positive self or family history of autoimmune diseases).

Fig. 3.

Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 consist of an inactivated whole-virion or encode for the synthesis of viral S protein to induce an immune response. The S protein of SARS-CoV-2 and certain human proteins share a considerable number of peptides, including thyroid peroxidase. As a result of this molecular mimicry, pathogen-specific antibody responses may interact with thyroidal structures following vaccination. Vaccine adjuvants are used to strengthen the immune response and cause higher antibody titers. However, they may trigger autoimmunity in susceptible individuals. Whether adjuvants increase the risk of developing molecular mimicry-related autoimmunity in susceptible subjects by increasing autoantibody production is unclear. Genetic predisposition (e.g., carrying HLA-B*35, HLA-C*04, and maybe HLA-A*11 alleles) appears to be the key in the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced SAT, since only a small percentage of individuals develop autoimmune disorders after receiving a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. HLA: human leukocyte antigen, TPO: thyroid peroxidase.

Summary

Several vaccines have been developed, and billions have been vaccinated quickly against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) to control the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, one of the most devastating epidemics in human history. Since the massive vaccination campaign worldwide, an increasing number of cases indicating a possible relationship between inflammatory thyroid disorders and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have been described in the literature. Early reports have identified a possible connection between SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and subacute thyroiditis, and accumulated evidence has confirmed this association. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis is an uncommon complication of vaccination that mainly affects young and middle-aged women with a certain genetic background. It usually develops a few days after vaccination, and all SARS-CoV-2 vaccines can cause vaccine-induced SAT at any dose. The clinical findings are not severe, and the disease is self-limiting. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or low-dose glucocorticoids are sufficient to control the disease in most. The disease duration is short, and relapses are not frequent.

The clinical and demographic characteristics of new-onset SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced painless thyroiditis and GD are highly comparable to those not caused by vaccination. Nearly all cases have been related to mRNA and adenovirus-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccines shortly after vaccinations. The clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced painless thyroiditis was mild, requiring no treatment and resolving in most patients in one to two months. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD cases can be new-onset or relapse. GD presents mostly with thyrotoxicosis symptoms and may cause cardiac complications in older patients. New-onset orbitopathy may emerge in both new-onset and relapse GD cases. Worsening of pre-existing thyroid eye disease is also possible, especially in patients with a history of severe GO. Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GD with anti-thyroid medications could be initiated in doses used for non-vaccine-related cases, but the time to remission is unclear. There is currently no evidence to support any other strategies for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced GO cases different than the ones recommended in the guidelines. Long-term follow-up data are lacking, and more information on the safety of revaccinations is still needed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.WHO Technical Guidance. Naming the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and the Virus That Causes It (2020). 2020.

- 2.Zhang Z., Shen Q., Chang H. Vaccines for COVID-19: a systematic review of immunogenicity, current development, and future prospects. Front Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.843928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jara L.J., Vera-Lastra O., Mahroum N., et al. Autoimmune post-COVID vaccine syndromes: does the spectrum of autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome expand? Clin Rheuma. 2022;41:1603–1609. doi: 10.1007/s10067-022-06149-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kojima M., Nakamura S., Oyama T., et al. Cellular composition of subacute thyroiditis. an immunohistochemical study of six cases. Pathol Res Pr. 2002;198:833–837. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce E.N., Farwell A.P., Braverman L.E. Thyroiditis. N. Engl J. Med. 2003;348:2646–2655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuels M.H. Subacute, silent, and postpartum thyroiditis. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fatourechi V., Aniszewski J.P., Fatourechi G.Z., et al. Clinical features and outcome of subacute thyroiditis in an incidence cohort: Olmsted County, Minnesota, study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2100–2105. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stasiak M., Tymoniuk B., Michalak R., et al. Subacute thyroiditis is associated with HLA-B*18:01, -DRB1*01 and -C*04:01-the significance of the new molecular background. J Clin Med. 2020:9. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossetti C.L., Cazarin J., Hecht F., et al. COVID-19 and thyroid function: What do we know so far? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.1041676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iitaka M., Momotani N., Ishii J., et al. Incidence of subacute thyroiditis recurrences after a prolonged latency: 24-year survey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:466–469. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lanzo N., Patera B., Fazzino G.F.M., et al. The old and the new in subacute thyroiditis: an integrative review. Endocrines. 2022;3:391–410. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanzo N., Patera B., Fazzino G.F.M., et al. The old and the new in subacute thyroiditis: an integrative review. endocrines. 2022;3:391–410. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanriover M.D., Doğanay H.L., Akova M., et al. Efficacy and safety of an inactivated whole-virion SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac): interim results of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial in Turkey. Lancet. 2021;398:213–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01429-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahçecioğlu A.B., Karahan Z.C., Aydoğan B.I., et al. Subacute thyroiditis during the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:865–874. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].İremli B.G., Şendur S.N., Ünlütürk U. Three cases of subacute thyroiditis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: postvaccination ASIA syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106:2600–2605. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bornemann C., Woyk K., Bouter C. Case report: two cases of subacute thyroiditis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021:8. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.737142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chatzi S., Karampela A., Spiliopoulou C., et al. Subacute thyroiditis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a report of two sisters and summary of the literature. Hormones. 2022;21:177–179. doi: 10.1007/s42000-021-00332-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Das L., Bhadada S.K., Sood A. Post-COVID-vaccine autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome in response to adjuvants (ASIA syndrome) manifesting as subacute thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:465–467. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01681-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeeyavudeen M.S., Patrick A.W., Gibb F.W., et al. COVID-19 vaccine-associated subacute thyroiditis: an unusual suspect for de Quervain's thyroiditis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021:14. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-246425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyriacou A., Ioakim S., Syed A.A. COVID-19 vaccination and a severe pain in the neck. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;94:95–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee K.A., Kim Y.J., Jin H.Y. Thyrotoxicosis after COVID-19 vaccination: seven case reports and a literature review. Endocrine. 2021;74:470–472. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02898-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Oğuz S.H., Şendur S.N., İremli B.G., et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced thyroiditis: safety of revaccinations and clinical follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e1823–e1834. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oyibo S.O. Subacute thyroiditis after receiving the adenovirus-vectored vaccine for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Cureus. 2021;13 doi: 10.7759/cureus.16045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandya M., Thota G., Wang X., et al. Thyroiditis after COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: a case series. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2022;8:116–118. doi: 10.1016/j.aace.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel K.R., Cunnane M.E., Deschler D.G. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;43 doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.103211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pla Peris B., Merchante Alfaro A., Maravall Royo F.J., et al. Thyrotoxicosis following SARS-COV-2 vaccination: a case series and discussion. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:1071–1077. doi: 10.1007/s40618-022-01739-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pujol A., Gómez L.A., Gallegos C., et al. Thyroid as a target of adjuvant autoimmunity/inflammatory syndrome due to mRNA-based SARS-CoV2 vaccination: from Graves' disease to silent thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:875–882. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01707-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ratnayake G.M., Dworakowska D., Grossman A.B. Can COVID-19 immunisation cause subacute thyroiditis? Clin Endocrinol. 2022;97:140–141. doi: 10.1111/cen.14555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Şahin Tekin M., Şaylısoy S., Yorulmaz G. Subacute thyroiditis following COVID-19 vaccination in a 67-year-old male patient: a case report. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:4090–4092. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1947102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saygılı E.S., Karakilic E. Subacute thyroiditis after inactive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. BMJ Case Rep. 2021:14. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-244711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sigstad E., Grøholt K.K., Westerheim O. Subacute thyroiditis after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. Tidsskr Nor Laege. 2021:141. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.21.0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siolos A., Gartzonika K., Tigas S. Thyroiditis following vaccination against COVID-19: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Metab Open. 2021;12 doi: 10.1016/j.metop.2021.100136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soltanpoor P., Norouzi G. Subacute thyroiditis following COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9 doi: 10.1002/ccr3.4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sözen M., Topaloğlu Ö., Çetinarslan B., et al. COVID-19 mRNA vaccine may trigger subacute thyroiditis. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:5120–5125. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.2013083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vasileiou V., Paschou S.A., Tzamali X., et al. Recurring subacute thyroiditis after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine: a case report. Case Rep. Women’s Health. 2022;33 doi: 10.1016/j.crwh.2021.e00378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raven L.M., McCormack A.I., Greenfield J.R. Letter to the editor from raven et al.: three cases of subacute thyroiditis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022:e1767–e1768. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bostan H., Unsal I.O., Kizilgul M., et al. Two cases of subacute thyroiditis after different types of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2022;66:97–103. doi: 10.20945/2359-3997000000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jhon M., Lee S.H., Oh T.H., et al. Subacute thyroiditis after receiving the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Moderna): the first case report and literature review in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37 doi: 10.3346/jkms.2022.37.e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan F., Brassill M.J. Subacute thyroiditis post-Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccination for COVID-19. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2021:2021. doi: 10.1530/EDM-21-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schimmel J., Alba E.L., Chen A., et al. Letter to the editor: thyroiditis and thyrotoxicosis after the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. Thyroid. 2021:1440. doi: 10.1089/thy.2021.0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yorulmaz G., Sahin Tekin M. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-associated subacute thyroiditis. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:1341–1347. doi: 10.1007/s40618-022-01767-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adelmeyer J., Goebel J.N., Kauka A., et al. Two case reports of subacute thyroiditis after receiving vaccine for COVID-19. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/3180004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alkis N., Baysal M. Subacute thyroiditis after SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in a multiple myeloma patient. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022;10 doi: 10.1177/2050313X221091392. 2050313×221091392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennet W.M., Elamin A., Newell-Price J.D. Subacute thyroiditis following COVID-19 vaccination: case report and Society for Endocrinology survey. Clin Endocrinol. 2022 doi: 10.1111/cen.14716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brès F., Joyeux M.A., Delemer B., et al. Three cases of thyroiditis after COVID-19 RNA-vaccine. Ann Endocrinol. 2022;83:262–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2022.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Casey C., Higgins T. Subacute thyroiditis post viral vector vaccine for COVID-19. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2022:2022. doi: 10.1530/EDM-21-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang Y., Chen X., Wang Q., et al. Case report: subacute thyroiditis after receiving SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, maybe not only adjuvants. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022:9. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.856572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kishimoto M., Ishikawa T., Odawara M. Subacute thyroiditis with liver dysfunction following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination: report of two cases and a literature review. Endocr J. 2022;69:947–957. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ21-0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murashita M., Wada N., Baba S., et al. Subacute thyroiditis associated with thyrotoxic periodic paralysis after COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2022:2022. doi: 10.1530/EDM-22-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pi L., Lin J., Zheng Y., Wang Z., et al. Case Report: Subacute thyroiditis after receiving inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (BBIBP-CorV) Front Med. 2022:9. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.918721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pipitone G., Rindi L.V., Petrosillo N., et al. Vaccine-induced subacute thyroiditis (De Quervain's) after mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a case report and systematic review. Infect Dis Rep. 2022;14:142–154. doi: 10.3390/idr14010018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raashid S., Khan O., Rehman Z., et al. Subacute thyroiditis after receiving inactivated virus vaccine for COVID-19. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2022;12:14–17. doi: 10.55729/2000-9666.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reisi-Vanani V., Farzan M., Farzan M., et al. Role of the immune system and possible mechanisms in COVID-19 vaccine-induced thyroiditis: case report and literature review. J Clin Transl Endocrinol Case Rep. 2022;26 doi: 10.1016/j.jecr.2022.100138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saha A., Chittimoju S., Trivedi N. Thyroiditis after mRNA vaccination for COVID-19. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/7604295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taşkaldıran I., Altay F.P., Bozkuş Y., et al. A case report of concurrent Graves' disease and subacute thyroiditis following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: an autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome (ASIA) Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2022 doi: 10.2174/1871530322666220621101209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teti C., Nazzari E., Graziani G., et al. Subacute thyroiditis after SARS-CoV2 vaccine: possible relapse after boosting. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:2019–2020. doi: 10.1007/s40618-022-01856-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wijenayake U.N., Ratnayake G.M., Abeyratne D., et al. A case report of subacute thyroiditis after inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2022:10. doi: 10.1177/2050313X221140243. 2050313×221140243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borges Canha M., Neves J.S., Oliveira A.I., et al. Subacute thyroiditis after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 Vaxzevria vaccination in a patient with thyroid autoimmunity. Cureus. 2022;14 doi: 10.7759/cureus.22353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flores Rebollar A. Subacute thyroiditis after anti-SARS-CoV-2 (Ad5-nCoV) vaccine. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:459–460. doi: 10.1016/j.eimce.2022.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.González López J., Martín Niño I., Arana, Molina C. Subacute thyroiditis after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: report of two clinical cases. Med Clin. 2022;158:e13–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.medcle.2022.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ippolito S., Gallo D., Rossini A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-associated subacute thyroiditis: insights from a systematic review. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:1189–1200. doi: 10.1007/s40618-022-01747-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakaizumi N., Fukata S., Akamizu T. Painless thyroiditis following mRNA vaccination for COVID-19. Horm (Athens) 2022;21:335–337. doi: 10.1007/s42000-021-00346-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marsukjai A., Theerasuwipakorn N., Tumkosit M. Concomitant myocarditis and painless thyroiditis after AstraZeneca coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16:212. doi: 10.1186/s13256-022-03438-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Capezzone M., Tosti-Balducci M., Morabito E.M., et al. Silent thyroiditis following vaccination against COVID-19: report of two cases. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:1079–1083. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01725-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith T.J. Hegedüs L.Graves' disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1552–1565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1510030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abeillon-du Payrat J., et al. Grunenwald S., Gall E. Graves' orbitopathy post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: report on six patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40618-022-01955-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cuenca D., Aguilar-Soto M., Mercado M. A case of Graves' disease following vaccination with the oxford-AstraZeneca SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2022;9 doi: 10.12890/2022_003275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park K.S., Fung S.E., Ting M., et al. Thyroid eye disease reactivation associated with COVID-19 vaccination. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2022;12:93–96. doi: 10.4103/tjo.tjo_61_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bostan H., Ucan B., Kizilgul M., et al. Relapsed and newly diagnosed Graves' disease due to immunization against COVID-19: a case series and review of the literature. J Autoimmun. 2022;128 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chaudhary S., Dogra V., Walia R. Four cases of Graves' disease following viral vector severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine. Endocr J. 2022;69:1431–1435. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ22-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chee Y.J., Liew H., Hoi W.H., et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination and Graves' disease: a report of 12 cases and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:e2324–e2330. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chua M.W.J. Graves' disease after COVID-19 vaccination. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2022;51:127–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.di Filippo L., Castellino L., Giustina A. Occurrence and response to treatment of Graves' disease after COVID vaccination in two male patients. Endocrine. 2022;75:19–21. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02919-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goblirsch T.J., Paulson A.E., Tashko G., et al. Graves' disease following administration of second dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. BMJ Case Rep. 2021:14. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-246432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lui D.T.W., Lee K.K., Lee C.H., et al. Development of Graves' disease after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination: a case report and literature review. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.778964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Manta R., Martin C., Muls V., et al. New-onset Graves' disease following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a case report. Eur Thyroid J. 2022:11. doi: 10.1530/ETJ-22-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Mohamed A., Tzoulis P., Kossler A.L., et al. New onset or deterioration of thyroid eye disease after mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines:report of 2 cases and literature review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgac606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patrizio A., Ferrari S.M., Antonelli A., et al. A case of Graves' disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. J Autoimmun. 2021;125 doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ruggeri R.M., Giovanellla L., Campennì A. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine may trigger thyroid autoimmunity: real-life experience and review of the literature. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:2283–2289. doi: 10.1007/s40618-022-01863-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sakai M., Takao K., Kato T., et al. Graves' disease after administration of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine in a type 1 diabetes patient. Intern Med. 2022;61:1561–1565. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.9231-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shih S.R., Wang C.Y. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination related hyperthyroidism of Graves' disease. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121:1881–1882. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2022.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Taieb A., Sawsen N., Asma B.A., et al. A rare case of Grave's disease after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: is it an adjuvant effect? Eur Rev Med Pharm Sci. 2022;26:2627–2630. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202204_28500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vera-Lastra O., Ordinola Navarro A., Cruz Domiguez M.P., et al. Two cases of Graves' disease following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: an autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. Thyroid. 2021;31:1436–1439. doi: 10.1089/thy.2021.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Weintraub M.A., Ameer B., Sinha Gregory N. Graves disease following the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: case series. J Invest Med High Impact Case Rep. 2021;9 doi: 10.1177/23247096211063356. 23247096211063356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamamoto K., Mashiba T., Takano K., et al. A case of exacerbation of subclinical hyperthyroidism after first administration of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccined. 2021:9. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zettinig G., Krebs M. Two further cases of Graves' disease following SARS-Cov-2 vaccination. J Endocrinol Invest. 2022;45:227–228. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01650-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pierman G., Delgrange E., Jonas C. Recurrence of Graves' disease (a Th1-type Cytokine disease) following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine administration: a simple coincidence? Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.12890/2021_002807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sriphrapradang C. Aggravation of hyperthyroidism after heterologous prime-boost immunization with inactivated and adenovirus-vectored SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in a patient with Graves' disease. Endocrine. 2021;74:226–227. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02879-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]