Abstract

Background:

Aortic arch calcium (AAC), which is frequently detected on ungated lung computed tomography (CT) due to a large field of view, can serve as a marker of subclinical atherosclerotic burden. Our study sought to validate novel cardiac screening metrics of subclinical atherosclerosis by evaluating the inter- and intra-observer reproducibility of AAC measurements with ungated lung CT.

Methods:

The authors randomly selected 100 ungated lung CT scans from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis cohort. A Bland-Altman plot analysis was used to test inter- and intra-reader reproducibility, after measuring the total arch calcium score and arch calcium volume.

Results:

The intra-reader reproducibility for the total arch calcium score and arch calcium volume in all subjects was excellent at 99% and 97%, respectively. The inter-reader reproducibility for the total arch calcium score and volume in all subjects was similarly excellent at 97% and 96%, respectively.

Conclusions:

The high reproducibility of ungated lung CT suggests a potential new method of stratifying the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk among patients undergoing lung CT without requiring additional scanning. This methodology helps promote routine reporting of AAC and coronary artery calcium based on millions of ungated CT images acquired for lung screening purposes.

Keywords: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, coronary artery calcium scoring, computed tomography, extracoronary calcification, MESA

I. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for over 30% of annual global fatalities1). One approach to predicting the cardiovascular risk is coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring, a direct measure of the atherosclerotic plaque burden2,3). CAC is a validated marker of subclinical atherosclerosis on both electrocardiogram (ECG)-gated/cardiac and non-gated/lung computed tomography (CT), and it offers a robust assessment of the CVD risk. While aortic valve and aortic arch calcification are almost invariably atherosclerotic, they are commonly overlooked in studies investigating the relationship between plaque burden and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk. The atherosclerotic calcium burden in aortic and other noncoronary structures can be readily quantified on non-gated CT due to the larger field of view than with gated scans, which may hold significant value in predicting future cardiac events and clinical outcomes4,5).

Aortic atherosclerotic plaque greatly affects stroke risk but is not considered a traditional prediction tool6). In fact, the prevalence of severe aortic plaque as a cause of stroke (14%–21%) is comparable to that of other predominant agents of embolic stroke, including carotid artery disease (10%–13%) and atrial fibrillation (18%–30%) 7,8). Kronzon et al. found that proximal aortic plaque thickness ≥ 5 significantly increases the risk of stroke and peripheral embolization6). With aortic plaque as (1) a well-established marker of atherosclerosis and (2) an important cause of iatrogenic stroke and peripheral emboli, it is imperative to consider the mechanistic implications of aortic arch calcium (AAC)6, 9). Aortic atherosclerosis may greatly influence future acquisition strategies and clinical reporting tools. The present study therefore focused on the creation of a key platform to follow in the detailed assessment of AAC as an ASCVD risk predictor and evaluated for the first time the reproducibility of novel aortic arch segmenting methods.

The novelty of this study also stems from its examination of cardiac calcium reproducibility on lung CT. Millions of ungated CT images are acquired yearly for lung screening purposes, and coronary data are not routinely reported. The evaluation of lung CT findings in this context would support the recognition of CV risk even in non-cardiac studies. The clinical incorporation of coronary and aortic into all non-contrast chest CT reports could facilitate the early diagnosis, treatment, and patient counseling for coronary artery disease (CAD) and atherosclerosis, improving both preventive care and treatment adherence in CVD.

Aortic arch calcium (AAC) is frequently detected on ungated lung CT and can serve as a marker of subclinical atherosclerotic burden. However, the prognostic value of AAC remains unclear. The present study therefore validated novel cardiac screening metrics of subclinical atherosclerosis by assessing the inter- and intra- observer reproducibility of AAC. Through the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) involving ungated non-contrast lung CT, the quantification of full aortic arch and valve calcification was possible without additional imaging. Future studies will apply this paper’s validated methodology and examine the potential utility of AAC for improving ASCVD risk prediction.

II. Materials and methods

1. Study population

Data in this study was gathered from the MESA, which involved a diverse sample of 6,814 men and women 45–84 years old and free of clinically evident CVD at the study intake. This prospective cohort was curated as a population-based sample powered to assess the associations between atherosclerotic plaque calcium and ASCVD risk within major ethnic groups in the United States10). All individuals gave their informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the review board at each institution in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The original MESA study design and methods have been previously published4).

A subset of the MESA population was assessed to determine the reproducibility of the technique used for aortic arch calcification measurement. In total, 100 participants were used in the analysis.

2. Image analyses

Among the six MESA study sites, three sites utilized four slice multi-detector row CT scanners, while three used an Imatron C-150XL electron beam CT Scanner (GE Healthcare Systems ; Chicago, IL, USA), as previously reported11). Axial images of the thorax were acquired in the supine position. The present ancillary study will analyze images obtained during the inspiration phase. Scans have a slice thickness of 0.75 mm.

All images were analyzed in blinded fashion by trained technologists at the CT Reading Center at the Lundquist Institute of Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, the same group that has analyzed all CT findings since the MESA’s inception. Utilizing the methods detailed below to calculate the aortic arch calcification score and volume, trained readers complete 1 read in approximately 10–15 minutes.

3. Calcium scoring measurements

Calcification on CT was measured using the Philips HeartBeat CS software program (Philips Company, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The following measures of calcium were obtained: area, volume (area × CT slice thickness), density [both mean and maximum attenuation of plaque in Hounsfield Units (HU)], density factor [ordinal score corresponding to the maximum plaque attenuation (1 = 130–199 HU ; 2 = 200–299 HU ; 3 = 300–399 HU ; 4 = ≥ 400 HU)], and Agatston score (area × density factor)12, 13). Any structures with complete absence of calcium were assigned scores of 0. Note that in structures with no calcium present, the calcium density was undefined.

All CT studies were scored for arch calcium burden in the following segmentations: aortic valve and root ; south and north aortic arch segment; brachiocephalic, common carotid and subclavian artery ; and ascending and descending aorta. These measures were also summed to yield the total arch calcium score and total arch volume. The anatomical definitions used to segment these aortic arch regions are described below.

4. Novel aortic arch screening metrics: anatomical definitions and segmentation

Aortic valve calcification (AVC) and aortic wall calcification (AWC)

AVC and AWC are scored following methods previously described for the measurement of coronary and aortic calcification3, 11). Calcified regions that extend from the aortic root into the aortic lumen are categorized as AVC14), whereas AWC is defined as the sum of calcification present along the circumference of the aortic root.

Both AVC and AWC are scored within the same slice levels, beginning from the slice level of the left main coronary artery (LMCA) and proceeding inferiorly to the level at which the right coronary artery (RCA) emerges from the right coronary cusp.

Aortic arch calcification (AAC)

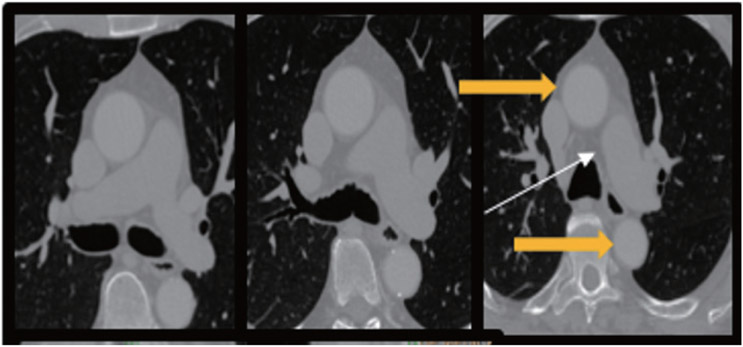

Next, to analyze the aortic arch segment, the right pulmonary artery (RPA) serves as an anatomic marker15). The most superior slice of the RPA (Fig. 1. white arrow) defines the end-RPA level, which we use to define the initiation of the aortic arch (Fig. 1, yellow arrows). In turn, we define the end-aortic arch level as the axial slice at which three distinct great vessels first become appreciable (Fig. 2). Any calcified focus seen from the end-RPA level to the end-aortic arch level is scored as AAC.

Fig. 1.

Axial CT images from a representative patient demonstrate the aortic arch initiation (yellow arrows), defined at the most superior slice level containing the right pulmonary artery (white arrow).

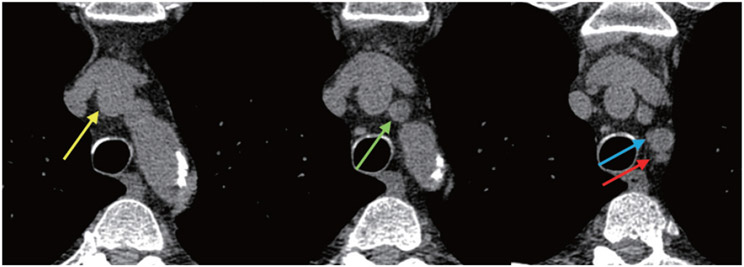

Fig. 2. Axial CT images depicting the identification of the end-aortic arch level.

Left: Only the brachiocephalic artery (yellow arrow) is clearly discernible. Middle: The left common carotid artery (green arrow) is discernible. Right: The brachiocephalic, left common carotid, and left subclavian (blue arrow) arteries become clearly discernible, defining the end-aortic arch level (red arrow).

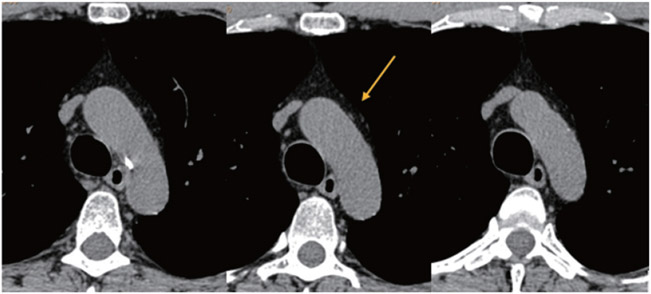

Initial studies suggest that calcium near the great vessels may indicate increased stroke risk6, 7). A detailed segmentation technique in this region of the proximal aorta may provide important mechanistic data to aid future studies. To further distinguish between inferior and superior arch calcification, we therefore separate the aortic arch into two segments: the inferior aspect and superior aspect of the aortic arch. We define the North-South aortic arch boundary on axial images using the following criteria: (1) the ascending and descending portions of the aortic arch must meet to become contiguous in a single oblong shape, (2) the transverse (i.e. left-right) aortic arch width is maximal, and (3) the longitudinal (i.e. anterior-posterior) arch length is stable or only minimally changing on the adjacent slice below. As illustrated in Fig. 3, these criteria mark the boundary distinguishing the South (inferior) and North (superior) aortic arch.

Fig. 3. Axial CT images defining the “North-South” (superior-inferior) aortic arch boundary.

The middle panel depicts the exact slice level at which the North-South arch boundary has been reached. At this level, (1) the ascending and descending arch components meet to form a contiguous, oblong shape, (2) the transverse aortic arch width is maximal, and (3) the longitudinal arch length is roughly unchanged from the adjacent slice below (left panel).

Ascending and descending thoracic aortic calcification

Similarly, the ascending and descending thoracic aorta are individually scored for calcification. Ascending aortic calcium is quantified from the level of the LMCA superiorly to the end-RPA level. Descending thoracic aortic calcium is quantified from the level of the end-RPA inferiorly to the cardiac apex (i.e. inferior-most slice level at which ventricular myocardium is still present). The distinct cardiac apex optimizes inter-observer reliability. We therefore employ this anatomic marker as the inferior boundary of the descending thoracic aorta in place of an alternate perimeter, such as the aortic hiatus.

The great vessels: Brachiocephalic artery calcification (BAC), common carotid artery calcification (CCAC), and subclavian artery calcification (SAC)

Calcification of the proximal components of the brachiocephalic artery, left common carotid artery, and left subclavian artery are also assessed. The same slice level (i.e. end-aortic arch level; see Fig. 2) is used to demarcate the common inferior border for calcium measurements of all three of these vessels. The proximal brachiocephalic, left common carotid, and left subclavian arteries will each be measured for plaque burden 25 mm superiorly from the end-aortic arch level. By dividing the total 25 mm by the image slice thickness, the exact number of slices to measure in the caudo-cranial direction can be determined. This strategy was chosen to follow the standard protocol among readers.

III. Reproducibility analyses

1. Aortic arch calcification measurement

The authors randomly selected 100 ungated lung CT images. A single reader completed extra-coronary measurements on the same scans twice to assess the intra-reader variability. The second reader then completed measurements on the same 100 patient scans to assess the inter-reader variability. These two trained analysts measured the scans independently while blinded to the demographic data and to each other’s reads.

2. Statistical analyses

A Bland-Altman plot analysis tested the reproducibility between the two readers and intra-reader variability. For patients with aortic arch calcification, calcium scores were measured with the Agatston and volumetric methods. The following measures were summed to yield the total arch calcium score and total arch calcium volume: aortic valve and root ; south and north aortic arch segment ; brachiocephalic, common carotid and subclavian artery ; and ascending and descending aorta. The intra- and inter- observer agreement for the total calcium score and volume were further divided into two groups: < 1000 and < 5000, respectively. This distinction was used to verify the reliability of reads for patients with a higher total calcium burden (< 5000) compared with those with a lower total calcium burden (< 1000).

3. Results

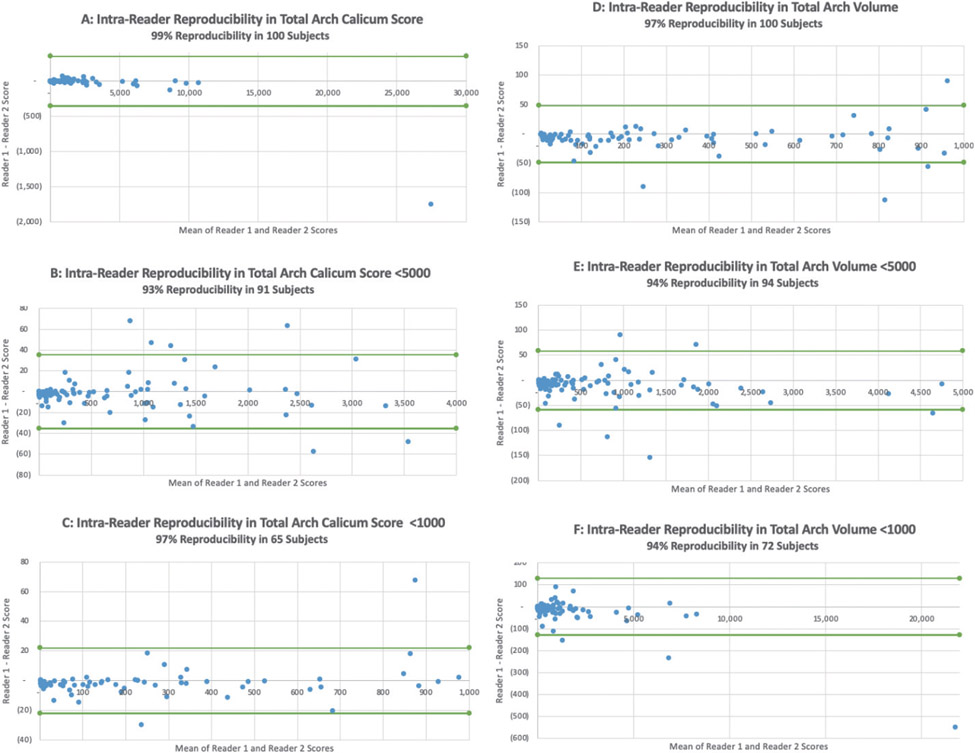

A total of 100 patients with aortic arch calcification on ungated lung CT were included in analyses. The intra-reader reproducibility was excellent for the total arch calcium score in all subjects (99%), subjects with < 5000 calcium (93%), and subjects with < 1000 calcium (97%) (Fig. 4A-C, respectively). The intra-reader reproducibility was also excellent for the total arch calcium volume in all subjects (97%), subjects with < 5000 volume (94%), and subjects with < 1000 volume (94%) (Fig. 4D-F, respectively).

Fig. 4. Bland-Altman intra-reader reproducibility plots.

These intra-reader reproducibility Bland-Altman plots all demonstrate excellent reader reproducibility. The intra-reader reproducibility was excellent for the total arch calcium score in all subjects (99%), subjects with < 5000 calcium (93%), and subjects with < 1000 calcium (97%) (A–C, respectively). The intra-reader reproducibility was also excellent for the total arch calcium volume in all subjects (97%), subjects with < 5000 volume (94%), and subjects with < 1000 volume (94%) (D–F, respectively).

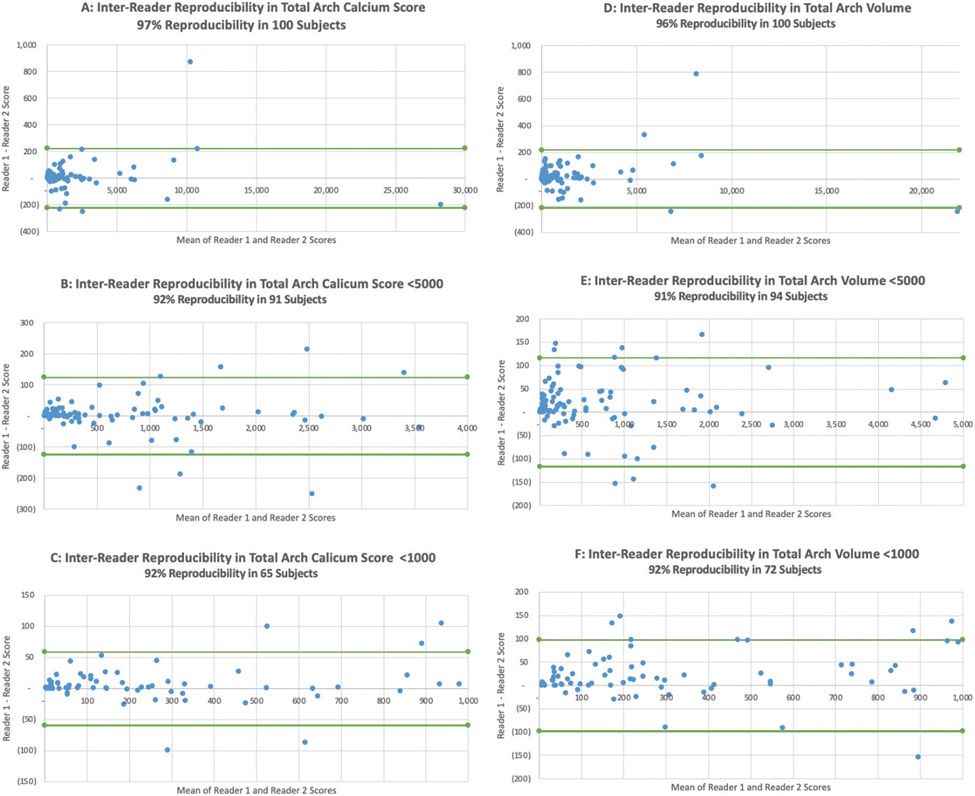

The inter-reader reproducibility was similarly excellent for the total arch calcium score in all subjects (97%), subjects with < 5000 calcium (92%), and subjects with < 1000 calcium (92%) (Fig. 5A-C, respectively). The inter-reader reproducibility was also excellent for the total arch calcium volume in all subjects (96%), subjects with < 5000 volume (91%), and subjects with < 1000 volume (92%) (Fig. 5D-F, respectively). The intra- and inter-reader reproducibility Bland-Altman plots are shown in Fig. 4 and 5, respectively.

Fig. 5. Bland-Altman inter-reader reproducibility plots.

These inter-reader reproducibility Bland-Altman plots all demonstrate excellent reader reproducibility. The inter-reader reproducibility was excellent for the total arch calcium score in all subjects (97%), subjects with < 5000 calcium (92%), and subjects with < 1000 calcium (92%) (A–C, respectively). The inter-reader reproducibility was also excellent for the total arch calcium volume in all subjects (96%), subjects with < 5000 volume (91%), and subjects with < 1000 volume (92%) (D–F, respectively).

Sub-analyses of arch calcification segments will be essential for future studies. Total arch reproducibility results attest to the strong intra- and inter-observer reproducibility of the aforementioned arch calcium measurement methods. These findings indicate the reputable nature of the methodology and anatomical definitions, which may be used to test whether or not CAC, AAC, and their respective calcium density scores predict future ASCVD events similarly between gated and ungated scans.

IV. Discussion

Low intra- and inter-observer variabilities on ungated lung CT attest to the proposed arch calcium measurement methods. These findings suggest that this AAC segmenting method should allow for atherosclerotic disease risk stratification among patients undergoing lung CT evaluations without requiring additional scanning. Our results confirm that measuring AAC on lung CT allows for the recognition of CV risk and helps promote routine reporting of calcium burden on millions of ungated CT images acquired for lung screening purposes.

1. Capability of AAC for predicting ASCVD events

The largest study of aortic arch calcification conducted thus far was the Rotterdam Study, the results of which were published by Bos et al.16). While our methodology stratifies the arch into unique and specific markers, Rotterdam evaluated the arch as a less specific, singular segment: from its origin to the first centimeter of the great arteries16). After adjusting for the calcium burden measured in other areas, aortic arch calcification remained independently associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality [hazard ratio (HR) per 1-standard deviation (SD) increase, 1.42 (95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.16–1.74)]. AAC was also significantly associated with cardiovascular mortality [HR, 2.72 (95% CI, 1.85–4.02)]. The Rotterdam Study also examined the incremental predictive value of AAC when used in addition to CAC to predict mortality and found moderate improvements in the predictive value for all mortality outcomes considered. Improved model performance was most pronounced for atherosclerotic cardiovascular mortality, with a continuous net reclassification of 0.36 (0.11–0.57) and 30.1% of events correctly reclassified16). Building on Rotterdam’s determined predictive value of AAC, our study for the first time stratifies the aortic arch into unique and standardizable anatomic segments. This paper’s novel methodology allows for a stratified regional assessment of AAC.

Subsequently, O’Dink performed a sub-analysis of the Rotterdam study to examine the association between CV risk factors and calcification of the coronary arteries, carotid arteries, and aortic arch17). A strong association between current smoking and AAC was found, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.5 in women and 4.7 in men (both P < 0.001). Additional associations were found between AAC and hypercholesterolemia, hypertension and diabetes.

2. Comparisons of calcium measurements on gated and ungated CT

In a select cohort of patients enrolled in the Genetic Epidemiology of COPD study who underwent both ECG-gated and non-gated thoracic CT studies, concordance between ECG-gated and non-gated techniques for the detection of coronary artery calcium was 100%, and concordance when CAC scores were stratified by clinical cut-points (i.e. density factor) was 94%18). In a separate study of 500 patients referred for lung cancer screening who underwent both types of testing, concordance rates for ECG-gated and non-gated thoracic CT were 97% and 93%, respectively19). These data support our high level of confidence in obtaining concordant calcium measurements from gated and ungated CT when assessing AAC burden.

Similarly, we previously performed an ancillary study in the MESA and correlated the accuracy of calcium burden from (1) ungated scans and (2) ECG-gated cardiac CT performed specifically for CAC scoring20). The CAC score was measured on both ungated and ECG-gated cardiac CT scans in a random sample of 516 subjects (mean age 68.5 ± 8.7 years old). CAC scores were divided into four intervals according to Agatston CAC Units, and 381 subjects had measurable CAC on at least one scan. Bland-Altman agreement analyses yielded r = 0.95 with an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.95 and a weighted i of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.84–0.89). Thus, we are highly confident we can accurately assess the calcium burden on lung CT.

3. Future directions

Validated AAC metrics on ungated CT allow for accurate ASCVD assessments on ungated thoracic CT scans without additional radiation, costs, or inconvenience for patients. Evaluating CVD and pulmonary disease based on a single imaging study is an effective addition to standard work-ups of lung disease patients that already require thoracic CT imaging. Uniquely, this methodology also presents the opportunity to evaluate the complex nature of interactions between pulmonary and cardiovascular systems at subclinical levels, before clinical manifestation of CVD. Using an extensive documented history of clinical stroke risk factors alongside novel AAC imaging metrics, future studies will strive to identify high- and low-risk patients across multiple age, gender, and race/ethnicity subgroups.

V. Conclusion

Segmented AAC measurements can be obtained reproducibly from routine ungated lung CT and may help improve cardiovascular risk assessments. These findings suggest that this AAC segmenting method will allow for atherosclerotic disease risk stratification among patients undergoing lung CT evaluations without requiring additional scanning.

It is imperative that we provide stronger evidence regarding the prognostic importance of AAC, CAC, and calcium density measured on non-gated CT. If these imaging metrics prove to be independent predictors of CVD events in future studies, this method will provide outcome data to enable widespread dissemination and application. Doing so will help encourage clinicians to describe the presence and severity of both AAC and CAC as a standard integrant of thoracic CT readings. Including coronary and aortic measurements in all non-contrast chest CT reports may greatly improve the rates of the early diagnosis, treatment, and patient education for CAD and atherosclerosis. This practice works to advance both preventative care and treatment adherence in CVD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by RO1 HL146666 and MESA was supported by contracts 75N92020D00001, HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, 75N92020D00005, N01-HC-95160, 75N92020D00002, N01-HC-95161, 75N92020D00003, N01-HC-95162, 75N92020D00006, N01-HC-95163, 75N92020D00004, N01-HC-95164, 75N92020D00007, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and by grants UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, and UL1-TR-001420 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Abbreviations

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- ASCVD

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

- CT

computed tomography

- CAC

coronary artery calcium

- AAC

aortic arch calcium

- MESA

multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/competing interests: Not applicable.

References

- 1).Mathers C, Fat DM, Boerma T: The global burden of disease: 2004 update. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2).Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, et al. : Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 72: 434–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Budoff MJ, Takasu J, Katz R, et al. : Reproducibility of CT measurements of aortic valve calcification, mitral annulus calcification, and aortic wall calcification in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Acad Radiol 2006; 13: 166–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Shavelle DM, Takasu J, Budoff MJ, et al. : HMG CoA reductase inhibitor (statin) and aortic valve calcium. Lancet 2002; 359: 1125–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Otto CM, Lind BK, Kitzman DW, et al. : Association of aortic-valve sclerosis with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in the elderly. N Engl J Med 1999; 341: 142–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Kronzon I, Tunick PA: Aortic atherosclerotic disease and stroke. Circulation 2006; 114: 63–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Jones EF, Kalman JM, Calafiore P, et al. : Proximal aortic atheroma: an independent risk factor for cerebral ischemia. Stroke 1995; 26: 218–224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Amarenco P, Cohen A, Tzourio C, et al. : Atherosclerotic disease of the aortic arch and the risk of ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 1474–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Thomas IC, McClelland RL, Allison MA, et al. : Progression of calcium density in the ascending thoracic aorta is inversely associated with incident cardiovascular disease events. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018; 19: 1343–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. : Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156: 871–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, et al. : Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology 2005; 234: 35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, et al. : Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990; 15: 827–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Hecht HS, Cronin P, Blaha MJ, et al. : 2016 SCCT/STR guidelines for coronary artery calcium scoring of noncontrast noncardiac chest CT: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society of Thoracic Radiology. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2017; 11: 74–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Yamamoto H, Shavelle D, Takasu J, et al. : Valvular and thoracic aortic calcium as a marker of the extent and severity of angiographic coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2003; 146: 153–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Allison MA, Criqui MH, Wright CM: Patterns and risk factors for systemic calcified atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004; 24: 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Bos D, Leening MJ, Kavousi M, et al. : Comparison of atherosclerotic calcification in major vessel beds on the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality: The Rotterdam Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2015; 8: e003843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).O’Dink AE, van der Lugt A, Hofman A, et al. : Risk factors for coronary, aortic arch and carotid calcification; The Rotterdam Study. J Hum Hypertens 2010; 24: 86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Budoff MJ, Nasir K, Kinney GL, et al. : Coronary artery and thoracic calcium on noncontrast thoracic CT scans: comparison of ungated and gated examinations in patients from the CORD Gene cohort. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2011; 5: 113–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Wu MT, Yang R Huang YL, et al. : Coronary arterial calcification on low-dose ungated MDCT for lung cancer screening: concordance study with dedicated cardiac CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190: 923–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Honoris L, DeFranco A, Port S, et al. : Correlation of coronary artery calcium scoring on ungated computed tomography compared to gated cardiac computed tomography scans from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 65 (10 Suppl): A1063 [Google Scholar]