Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Randomized controlled trials show that certain axillary surgical practices can be safely de-escalated in older adults with early-stage breast cancer. Hospital volume is often equated with surgical quality, but it is unclear if this includes performance of low-value surgeries. We sought to describe how utilization of two low-value axillary surgeries have varied by time and hospital volume.

METHODS:

Women ≥70 years diagnosed with breast cancer from 2013–2016 were identified in the National Cancer Database. The outcomes of interest were sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) in cT1N0 hormone receptor-positive cancer patients and axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in cT1–2N0 patients undergoing breast conserving surgery with ≤2 pathologically positive nodes. Time trends in procedure use and multivariable regression with restricted cubic splines were performed, adjusting for patient, disease, and hospital factors.

RESULTS:

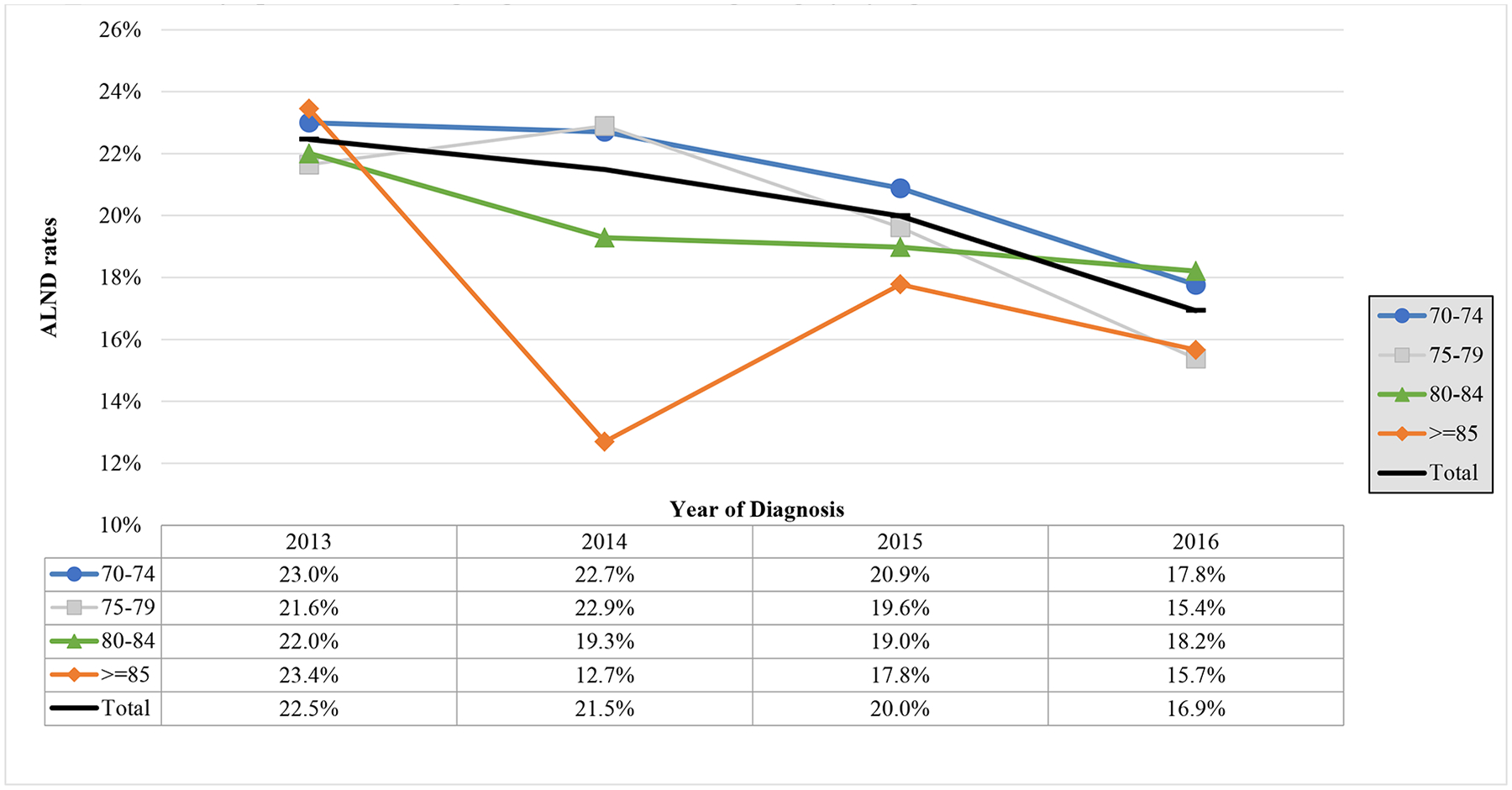

Overall, 83.4% of 44,779 women eligible for omission of SLNB underwent SLNB and 20.0% of 7,216 patients eligible for omission of ALND underwent ALND. SLNB rates did not change significantly over time, and remained significantly different by age group (70–74: 93.5%, 75–79: 89.7%, 80–84: 76.7%, ≥85: 48.9%, p<0.05). ALND rates decreased over the study period across all age groups included (22.5% to 16.9%, p<0.001). In restricted cubic splines models, lower hospital volume was associated with a higher likelihood of undergoing SLNB and ALND.

CONCLUSIONS:

ALND omission has been more widely adopted than SLNB omission in older adults, but lower hospital volume is associated with a higher likelihood of both procedures. Practice-specific de-implementation strategies are needed, especially for lower-volume hospitals.

INTRODUCTION

Existing randomized controlled trial data suggest that omission of axillary surgery in the following two instances do not portend a survival disadvantage: A) sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) in women ≥70 years with clinical (c)T1N0 hormone receptor-positive (HR+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative disease1–4 and B) axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) in women undergoing breast conserving surgery (BCS) with cT1–2N0 disease and with ≤2 pathologically positive lymph nodes on SLNB.5–9The former practice (SLNB omission) is supported by International Breast Cancer Study Group (IBCSG) 10–93 (published in 2006),1 Martelli et al’s randomized trial published in 2012,4 and long-term follow-up of Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 9343 (published in 2013)3; the latter practice (omission of ALND in the setting of <2 positive lymph nodes) is supported by American College of Surgeon Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011, published in 2011.6 These axillary surgical practices were deemed “low-value” by the Choosing Wisely campaign in 2016.10,11

Appropriate use of these axillary surgeries is especially important in older adults, as >30% of new breast cancer diagnoses annually in the U.S. are in women ≥70 years.12 ALND has adverse surgical effects in up to 70% of patients,13 and has been associated with significantly increased decisional regret in older breast cancer patients.14 In addition, although SLNB is viewed as a low-risk procedure, the potential for bleeding, infection, increased operative time, and lymphedema remain.13

Appropriate de-escalation of axillary surgery can be difficult among older adults as surgeons must weigh numerous factors (e.g., uncertainty regarding effect of omission of axillary surgery on adjuvant treatment, patient preference, contention with misaligned financial incentives). Moreover, diversity of patient life expectancies, competing risks, and frailty status create nuances in the relative risks and benefits of a given intervention, and may lead to variation in practice patterns.

While these decisions are made at the patient-physician interface, there may also be notable factors external to this exchange, such as hospital-related factors15–18 or time since the publication of landmark data, affecting the uptake of a given practice. It has been previously shown that higher annual breast surgery hospital volume associated with higher overall survival rates19 and that significant hospital-level variation exists15,20 in utilization of axillary surgery, but whether hospital volume is a proxy for quality with respect to the use of low-value surgeries remains unclear. As de-implementation efforts aimed at these practices evolve, it is crucial to understand at what level these efforts should be focused. We thus sought to describe the variation in rates of these two axillary surgical practices in older adults over time and by hospital volume.

METHODS

Data Source

Data from 2013–2016 were examined from the participant user file of the National Cancer Database (NCDB). The NCDB is a hospital-based oncology dataset that captures approximately 80% of newly diagnosed cancer in the U.S.21 It is a joint project of the American Cancer Society and the Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons, receiving data from approximately 1,500 CoC-accredited cancer programs. This study was deemed exempt from review by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board.

Patients

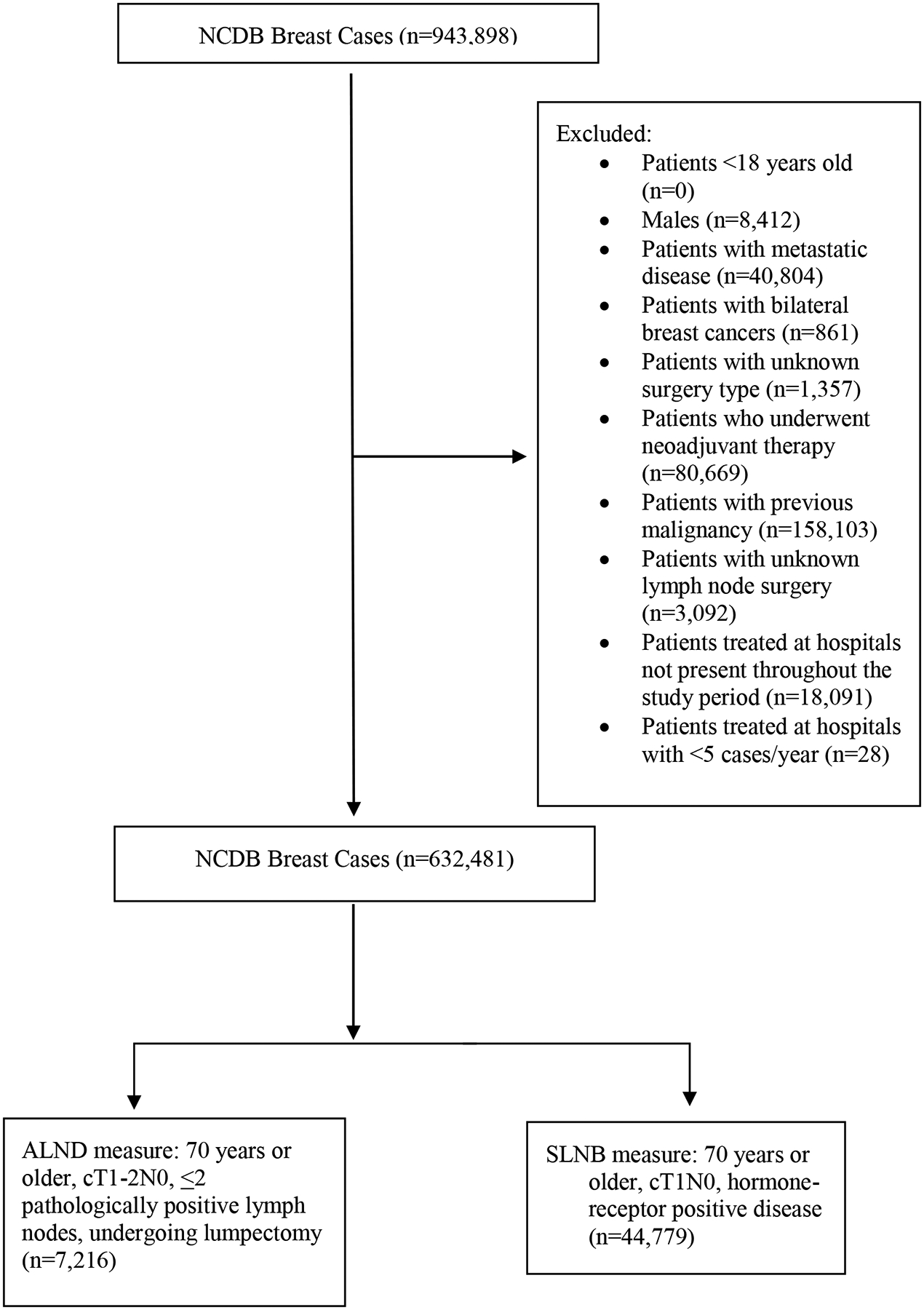

All patients ≥70 years diagnosed January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2016 who underwent breast cancer surgery were identified. The study years were chosen to depict U.S. practices after publication of the landmark data (i.e. publication of the long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343 was in 2013). The populations of interest, which did have some overlap, were defined by combining the pertinent Choosing Wisely recommendations10,11 with the population specifics of the landmark randomized controlled trials pertaining to de-escalation of axillary surgery in breast cancer patients. The SLNB Omission cohort included any patient with cT1N0 HR+ (defined as either estrogen receptor [ER]-positive or progesterone receptor [PR]-positive)/HER2-negative disease. The ALND Omission cohort included patients with cT1–2N0 breast cancer who underwent BCS and who had ≤2 pathologically positive lymph nodes, as defined by the ACOSOG Z0011 trial.6 As the Choosing Wisely recommendation regarding SLNB in patients with cT1N0 HR+/HER2− disease does not specify breast surgery type, patients undergoing mastectomy were included in the SLNB Omission cohort.10,22 Patients who underwent any type of neoadjuvant treatment, had bilateral or metastatic disease, had a previous malignancy, were male, had an unknown surgery type (i.e. did not explicitly have a lumpectomy or mastectomy, or, if undergoing axillary surgery, did not explicitly have SLNB or ALND), had unknown HR status, were treated in hospitals that were not present in the dataset for the entire study period, or hospitals treating <5 cases/year, were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

CONSORT diagram of patient population

Variables

The exposures of interest were year of diagnosis and annual hospital volume, defined as the number of non-metastatic breast cancer cases treated at a given facility divided by the number of study years (only hospitals present for all study years were included in this analysis). Hospital volume was defined on a continuous basis for the restricted cubic splines modeling. For the purposes of modeling volume as a categorical variable in other adjusted analyses, volume was divided at the 25th and 75th percentiles (low: <150 cases/year, medium: 151–433 cases/year, high: >433 cases/year).

Patient-level covariates included age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, insurance status, median patient zip code income and education level, Charlson Comorbidity Index score (CCI), regional location of the patient’s home zip code, and year of diagnosis. Disease characteristics included grade and tumor stage. Tumor subtype was classified by combinations of ER, PR, and HER2 status, with either ER or PR positivity qualifying a patient as HR+ (HR+/HER2+, HR+/HER2−, HR−/HER2+, HR−/HER2−, unknown). In addition to volume, other hospital-level covariates included status as a minority-serving hospital (defined as hospitals comprising the top decile of proportion of black patients treated),23,24 facility location (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) and facility type as defined by CoC accreditation status (academic, comprehensive community cancer center, community cancer program, integrated network cancer program).

Outcome Measures

The main outcomes of interest were the proportion of women who underwent each surgical procedure of interest (SLNB or ALND), among those eligible for omission.

Statistical Analysis

Separate analyses were performed for the ALND Omission cohort and SLNB Omission cohort. We performed Chi-square tests to test the significance of difference in unadjusted proportions of SLNB and ALND in the study population by patient, disease, and hospital characteristics. To test the significance of hospital volume on axillary surgery use, controlled for all other patient and hospital covariates, we performed random-effects multivariate generalized linear mixed models to account for hospital clustering. Variables for this model were chosen a priori based on clinical relevance.

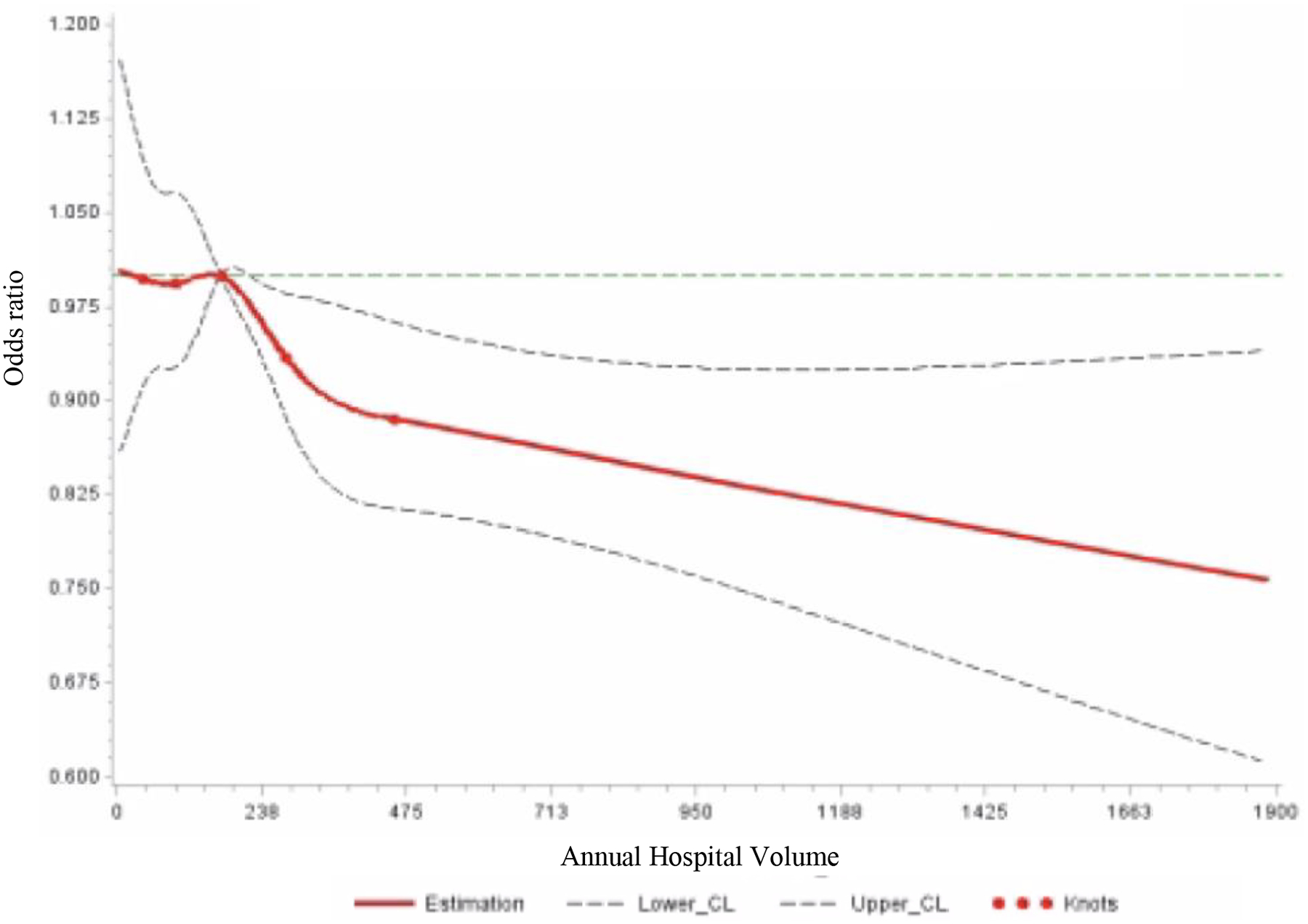

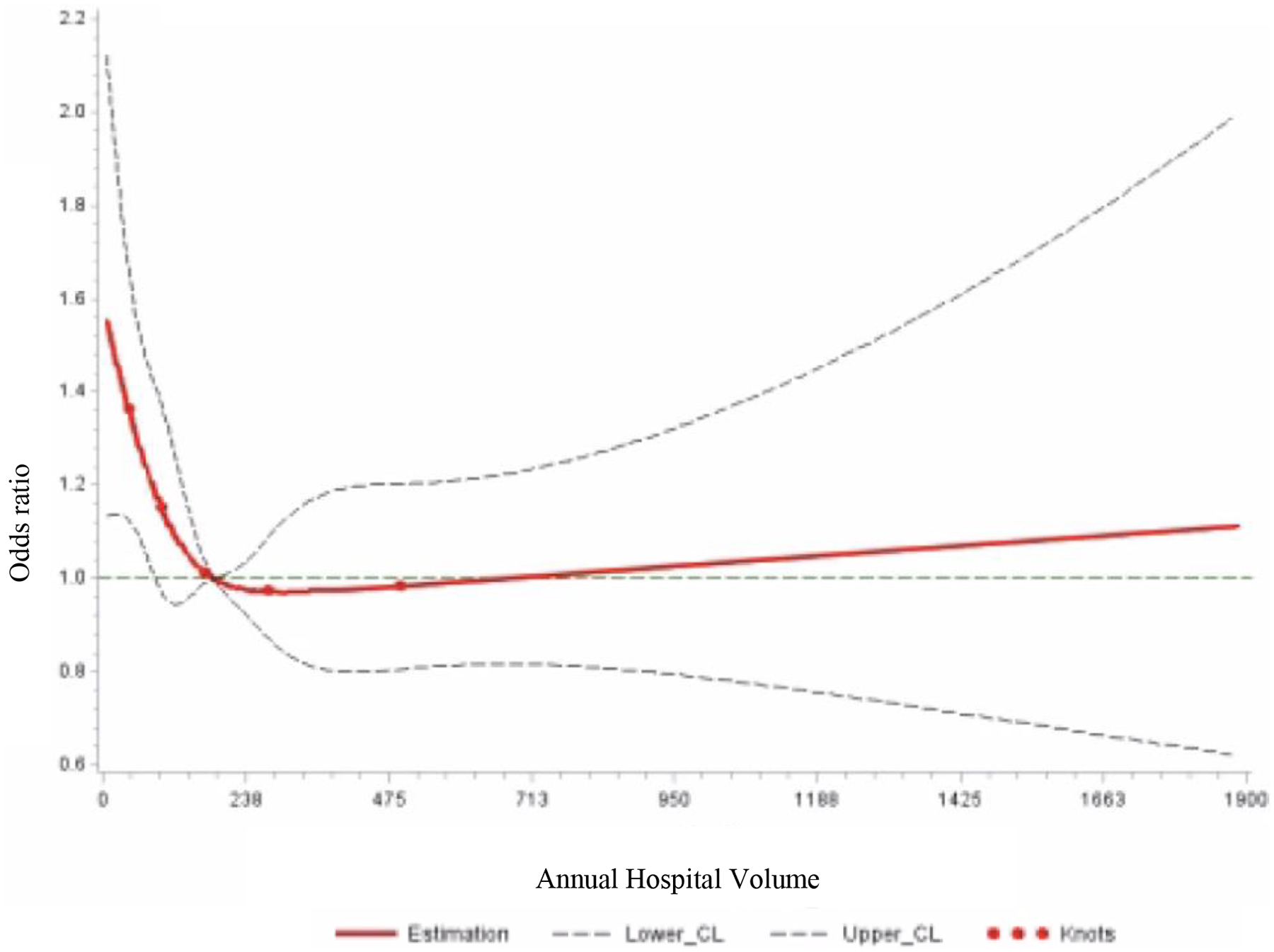

To display the non-linear relationship between hospital volume and “low-value” axillary surgery practices, hospital volume was treated as a continuous variable in restricted cubic splines modeling. Restricted cubic splines modeling allows for a flexible, non-linear model that demonstrates relationships without any presumption of arbitrary cutoffs.19,25 Figures 2a and 2b express odds ratios expressed with reference to the median hospital volumes for each respective recommendation (170 cases per year for the SLNB Omission population and 184 cases per year for the ALND Omission cohort) with 95% confidence intervals. These models were adjusted for age, race, year of diagnosis, insurance status, education, CCI, urban/rural status, tumor grade, subtype, stage, minority-serving hospital status, facility type, and facility location. Given the large sample size, a 5-knot model was chosen with knots at the 5, 25, 50, 75, and 95%.19,25 All tests were two-sided with a p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software, v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Figure 2a:

Restricted Cubic Splines Model of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB) in Patients ≥70 Years of Age with cT1N0 Hormone Receptor-Positive Disease by Hospital Volume

*Reference point set at median hospital volume for each procedure

CL: confidence limit

Figure 2b:

Restricted Cubic Splines Model of Axillary Lymph Node Dissection (ALND) in Patients ≥70 Years of Age with cT1–2N0, ≤2 Positive Lymph Nodes Undergoing Breast Conserving Surgery by Hospital Volume

*Reference point set at median hospital volume for each procedure

CL: 95% confidence limit

RESULTS

In total, 44,779 women met inclusion criteria for the SLNB Omission cohort and 7,216 women ≥70 years old met inclusion criteria for the ALND Omission cohort. Baseline characteristics of the population can be found in Table 1. Overall, of the patients eligible for the SLNB Omission cohort, 37,758 (84.3%) underwent SLNB. Adjuvant treatment rates in this cohort are available in Supplemental Table 1. Of the patients in the ALND Omission cohort, 1,446 (20.0%) underwent ALND.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of Patients 70 Years of Age or Older Diagnosed with Breast Cancer, 2013–2016, by Low-Value Axillary Surgery Practice

| ALND Omission Cohort: BCS Patients with cT1–2N0, ≤ 2 + LNs (%) (N=7,216) |

SLNB Omission Cohort: Patients with cT1N0 HR+ Disease (%) (N=44,779) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| 70–74 | 3,286 (45.5) | 17,073 (38.1) |

| 75–79 | 2,200 (30.5) | 14,572 (32.5) |

| 80–84 | 1,158 (16.1) | 8,131 (18.2) |

| ≥85 | 572 (7.9) | 5,003(11.2) |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 5,978 (82.8) | 37,815 (84.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 605 (8.4) | 3,051 (6.8) |

| Hispanic | 274 (3.8) | 1,434 (3.2) |

| Other | 269 (3.7) | 1,930 (4.3) |

| Unknown | 90 (1.3) | 549 (1.2) |

| Year of Diagnosis | ||

| 2013 | 1,545 (21.4) | 10,177 (22.7) |

| 2014 | 1,759 (24.4) | 10,692 (23.9) |

| 2015 | 1,916 (26.6) | 11,642 (26.0) |

| 2016 | 1,996 (27.7) | 12,268 (27.4) |

| Insurance status | ||

| Private | 731 (10.1) | 4,396 (9.8) |

| Government | 6,377 (88.4) | 39,773 (88.8) |

| None/Other | 108 (1.6) | 610 (1.4) |

| Median income | ||

| <$40,000 | 1,045 (14.5) | 6,502 (14.5) |

| >=$40,000 | 6,106 (84.6) | 37,807 (84.4) |

| Unknown | 65 (0.9) | 470 (1.1) |

| Education | ||

| >80% high school graduation rate | 6,029 (83.6) | 37,577 (83.9) |

| <=80% high school graduation rate | 1,129 (15.7) | 6,805 (15.2) |

| Unknown | 58 (0.8) | 397 (0.9) |

| Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index | ||

| 0 | 5,465 (75.7) | 34,534 (77.1) |

| 1 | 1,304 (18.1) | 7,497 (16.7) |

| >=2 | 447 (6.2) | 2,748 (6.1) |

| Urban/Rural status | ||

| Metropolitan county | 6,026 (83.5) | 37,354 (83.4) |

| Urban | 897 (12.4) | 5,498 (12.3) |

| Rural | 118 (1.6) | 782 (1.8) |

| Unknown | 175 (2.43) | 1,145 (2.6) |

| Disease Characteristics | ||

| ER/PR/HER-2 status | ||

| HR+/HER2+ | 694 (9.6) | N/A |

| HR+/HER2− | 4,783 (66.3) | N/A |

| HR−/HER2+ | 109 (1.5) | N/A |

| HR−/HER2− | 369 (5.11) | N/A |

| Unknown | 1,261 (17.5) | 0 |

| Tumor Grade | ||

| 1 | 1,625 (22.5) | 17,158 (38.3) |

| 2 | 3,753 (52.0) | 22,389 (50.0) |

| 3 | 1,562 (21.7) | 3,544 (7.9) |

| Unknown | 276 (3.8) | 1,688 (3.8) |

| Tumor Stage | ||

| T1 | 5,397 (75.8) | 100 |

| T2 | 1,819 (25.2) | N/A |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||

| Minority Serving Hospital | ||

| Yes | 389 (5.4) | 2,433 (5.4) |

| No | 6,827 (94.6) | 42,346 (94.6) |

| Facility Type | ||

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Center Program | 764 (47.9) | 21,120 (47.2) |

| Academic/Research | 1,951 (30.3) | 12,237 (27.3) |

| Community Cancer Program | 764 (10.6) | 4,713 (10.5) |

| Integrated Network Cancer Program | 1,048 (14.5) | 6,709 (15.0) |

| Facility Location | ||

| Northeast | 1,509 (20.9) | 10,458 (23.4) |

| Midwest | 1,944 (34.6) | 11,768 (26.3) |

| South | 2,498 (26.9) | 15,338 (34.3) |

| West | 1,265 (17.5) | 7,215 (16.1) |

| Hospital Volume | ||

| Low-Volume | 1,839 (25.5) | 11,546 (25.8) |

| Medium-Volume | 3,579 (49.6) | 21,802 (48.7) |

| High-Volume | 1,798 (24.9) | 11,431 (25.5) |

Abbreviations: BCS: breast-conserving surgery; LN: lymph nodes; HR: hormone receptor

SLNB Omission Cohort

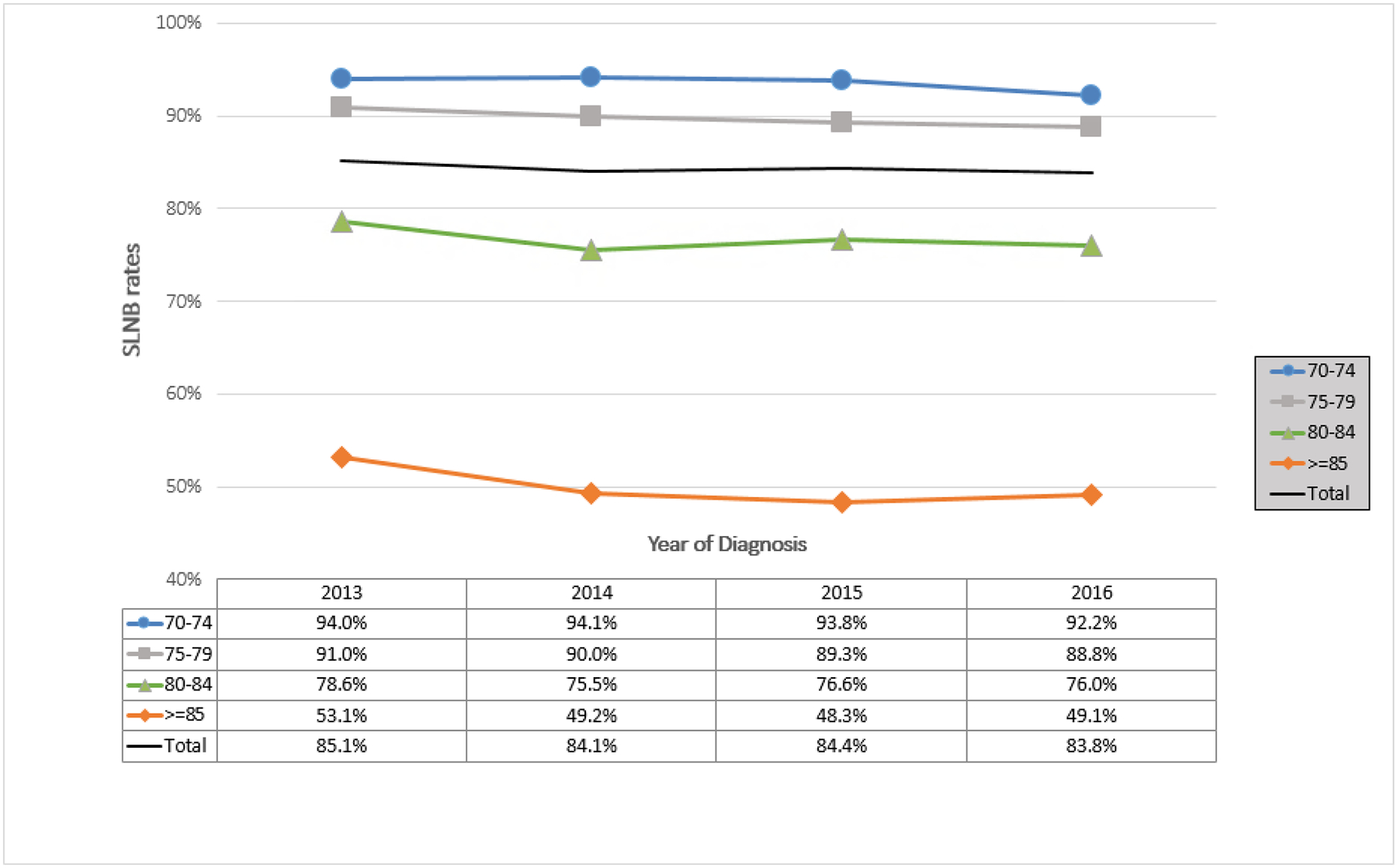

The rates of SLNB in women eligible for omission remained similar through the study years (85.1% to 83.8%, p<0.05) (Table 2). Figure 3a show unadjusted rates over time, demonstrating that SLNB rates in women eligible for omission were the lowest in older age groups—particularly those ≥85 years—and with little decrease over time. Adjusted analyses showed patients diagnosed in 2014–2016 had statistically significant decreased odds of undergoing a SLNB compared to those diagnosed in 2013 (2013: REF; 2014: OR 0.86, 95% CI [0.79–0.94]; 2015: OR 0.82, 95% CI [0.75–0.89]; 2016: OR 0.76, 95% CI [0.70–0.83]) (Table 3).

Table 2:

Unadjusted Proportions of Patients 70 Years of Age or Older Diagnosed with Breast Cancer, 2013–2016, Undergoing Low-Value Axillary Surgery by Cohort

| ALND Omission Cohort: ALND in BCS Patients ≥70 years with cT1–2N0, ≤2 + LNs |

SLNB Omission Cohort: SLNB in Patients >70 Years, T1N0 HR+ Disease |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALND (N=1,446, 20.0%) |

No ALND (N= 5770, 80.0%) |

SLNB (N= 37,758, 84.3%) |

No SLNB (N= 7,021, 15.7%) |

|

| Patient Characteristics | ||||

| Age (not sig for ALND) | ||||

| 70–74 | 687 (21.9) | 2,599 (79.1) | 15,957 (93.5) | 1,116 (6.5) |

| 75–79 | 433 (19.7) | 1,767 (80.3) | 13,072 (89.7) | 1,500 (10.3) |

| 80–84 | 226 (19.5) | 932 (80.5) | 6,233 (76.7) | 1,898 (23.3) |

| ≥85 | 100 (17.5) | 473 (82.5) | 2,496 (49.9) | 2,507 (50.1) |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1,180 (19.7) | 4,798 (80.3) | 31,970 (84.5) | 5,845 (15.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 126 (20.8) | 479 (79.2) | 2,523 (82.7) | 528 (17.3) |

| Hispanic | 74 (27.0) | 200 (73.0) | 1,202 (83.8) | 232 (16.2) |

| Other | 55 (21.5) | 214 (79.6) | 436 (79.4) | 113 (20.6) |

| Unknown | 11 (12.2) | 79 (87.8) | 1,627 (84.3) | 303 (15.7) |

| Year of Diagnosis | ||||

| 2013 | 347 (22.5) | 1,198 (77.5) | 8,661 (85.1) | 1,516 (14.9) |

| 2014 | 378 (21.5) | 1,381 (78.5) | 8,987 (84.1) | 1,705 (16.0) |

| 2015 | 383 (20.0) | 1,533 (80.0) | 9,824 (84.4) | 1,818 (15.6) |

| 2016 | 338 (16.9) | 1,658 (83.1) | 10,286 (83.8) | 1,982 (16.2) |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Private | 145 (19.8) | 586 (80.2) | 3,810 (86.7) | 586 (13.3) |

| Government | 1,278 (20.0) | 5,099 (80.0) | 33,465 (84.1) | 6,308 (15.9) |

| None/Other | 23 (21.3) | 85 (78.7) | 483 (79.2) | 127 (20.8) |

| Median income | ||||

| <$40,000 | 226 (21.6) | 819 (78.4) | 5,440 (83.7) | 1,062 (16.3) |

| >=$40,000 | 1,210 (19.8) | 4,896 (80.2) | 31,913 (71.3) | 5,894 (15.6) |

| Unknown | 10 (15.4) | 55 (84.6) | 405 (86.2) | 65 (13.8) |

| Education | ||||

| >80% high school graduation rate | 1,206 (20.0) | 4,823 (80.0) | 31,715 (84.4) | 5,862 (15.6) |

| <=80% high school graduation rate | 230 (20.4) | 899 (79.6) | 5,697 (83.7) | 1,108 (16.3) |

| Unknown | 10 (17.2) | 48 (82.8) | 346 (87.2) | 51 (12.9) |

| Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index | ||||

| 0 | 1,087 (19.9) | 4,378 (80.1) | 29,194 (84.5) | 5,340 (15.5) |

| 1 | 272 (20.9) | 1,032 (79.1) | 6,388 (85.2) | 1,109 (14.8) |

| >=2 | 87 (19.5) | 360 (80.5) | 2,176 (79.2) | 572 (20.8) |

| Urban/Rural status | ||||

| Metropolitan county | 1,207 (20.0) | 4,819 (80.0) | 31,298 (83.8) | 6,056 (16.2) |

| Urban | 175 (19.5) | 722 (80.5) | 4,866 (88.5) | 632 (11.5) |

| Rural | 25 (21.2) | 93 (78.8) | 690 (88.2) | 92 (11.8) |

| Unknown | 39 (22.3) | 136 (77.7) | 904 (78.9) | 241 (21.1) |

| Disease Characteristics | ||||

| ER/PR/HER-2 status | ||||

| HR+/HER2+ | 152 (21.9) | 542 (78.1) | N/A | N/A |

| HR+/HER2− | 916 (19.2) | 3,867 (80.9) | 37,758 (84.3) | 7,021 (15.7) |

| HR−/HER2+ | 30 (27.5) | 79 (72.5) | N/A | N/A |

| HR−/HER2− | 88 (23.9) | 281 (76.2) | N/A | N/A |

| Unknown | 260 (20.6) | 1,001 (79.4) | N/A | N/A |

| Tumor Grade | ||||

| 1 | 272 (16.7) | 1,353 (83.3) | 14,292 (83.3) | 2,866 (16.7) |

| 2 | 771 (20.5) | 2,982 (79.5) | 19,108 (85.4) | 3,281 (14.7) |

| 3 | 354 (22.7) | 1,208 (77.3) | 3,063 (86.4) | 481 (13.6) |

| Unknown | 49 (17.8) | 227 (82.3) | 1,295 (76.7) | 393 (23.3) |

| Tumor Stage | ||||

| T1 | 1,031 (19.1) | 4,366 (80.9) | 37,758 (84.3%) | 7,021 (15.7%) |

| T2 | 415 (22.8) | 1,404 (77.2) | N/A | N/A |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||||

| Minority Serving Hospital (not sig for SLNB) | ||||

| Yes | 101 (26.0) | 288 (74.0) | 2,071 (85.1) | 362 (14.9) |

| No | 1,345 (19.7) | 5,482 (80.3) | 35,687 (84.3) | 6,659 (15.7) |

| Facility Type | ||||

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Center Program | 698 (20.2) | 2755 (79.8) | 18087 (85.6) | 3033 (14.4) |

| Academic/Research | 378 (19.4) | 1573 (80.6) | 9886 (80.8) | 2351 (19.2) |

| Community Cancer Program | 188 (24.6) | 576 (75.4) | 4075 (86.5) | 638 (13.5) |

| Integrated Network Cancer Program | 182 (17.4) | 866 (82.6) | 5710 (85.1) | 999 (14.9) |

| Facility Location | ||||

| Northeast | 301 (20.0) | 1208 (80.1) | 8217 (78.6) | 2241 (21.4) |

| Midwest | 414 (21.3) | 1530 (78.7) | 10089 (85.7) | 1679 (14.3) |

| South | 495 (19.8) | 2003 (80.2) | 13289 (86.6) | 2049 (13.4) |

| West | 236 (18.7) | 1029 (81.3) | 6163 (85.4) | 1052 (14.6) |

| Hospital Volume | ||||

| Low-Volume | 442 (24.0) | 1397 (76.0) | 9851 (85.3) | 1695 (14.7) |

| Medium-Volume | 676 (18.9) | 2903 (81.1) | 18511 (84.9) | 3291 (15.1) |

| High-Volume | 328 (18.2) | 1470 (81.8) | 9396 (82.2) | 2035 (17.8) |

Abbreviations: ALND: axillary lymph node dissection; BCS: breast-conserving surgery; LN: lymph nodes; HR: hormone receptor; SLNB: sentinel lymph node biopsy

p<0.05 for comparison by column

Figure 3a:

Trends Over Time in Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB) in Patients ≥70 Years of Age with cT1N0 Hormone Receptor-Positive Disease by Age

Table 3:

Adjusted Logistic Regression Predicting Receipt of Axillary Surgery in Patients 70 Years of Age or Older Diagnosed with Breast Cancer, 2013–2016, by Low-Value Practice

| ALND Omission Cohort: ALND in Patients ≥70 Years with cT1–2N0, ≤2 + LNs (N=7,216) OR [95% CI] |

SLNB Omission Cohort: SLNB in Patients >70 Years, T1N0 HR+ Disease (N=44,779)OR [95% CI] |

|

|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ||

| Age | ||

| 70–74 | REF | REF |

| 75–79 | 0.91 [0.78–1.05] | 0.59 [0.54–0.64] |

| 80–84 | 0.89 [0.74–1.07] | 0.19 [0.18–0.21] |

| ≥85 | 0.73 [0.57–0.95] | 0.05 [0.04–0.05] |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | REF | REF |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.99 [0.78–1.27] | 0.90 [0.79–1.02] |

| Hispanic | 1.42 [1.02–1.97] | 0.88 [0.73–1.05] |

| Other | 1.02 [0.72–1.44] | 1.02 [0.87–1.21] |

| Unknown | 0.53 [0.27–1.03] | 0.68 [0.53–0.86] |

| Year of Diagnosis | ||

| 2013 | REF | REF |

| 2014 | 0.93 [0.77–1.11] | 0.86 [0.79–0.94] |

| 2015 | 0.82 [0.69–0.99] | 0.82 [0.75–0.89] |

| 2016 | 0.65 [0.54–0.78] | 0.76 [0.70–0.83] |

| Insurance status | ||

| Private | REF | REF |

| Government | 1.08 [0.87–1.34] | 0.88 [0.79–0.98] |

| None/Other | 1.06 [0.60–1.86] | 0.59 [0.45–0.76] |

| Median income | ||

| <$40,000 | REF | REF |

| >=$40,000 | 0.90 [0.73–1.11] | 1.16 [1.05–1.29] |

| Unknown | N/A | 0.99 [0.50–1.96] |

| Education | ||

| >80% high school graduation rate | REF | REF |

| <=80% high school graduation rate | 0.93 [0.75–1.14] | 0.98 [0.88–1.08] |

| Unknown | N/A | 1.18 [0.56–2.51] |

| Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Index | ||

| 0 | REF | REF |

| 1 | 1.02 [0.86–1.20] | 0.96 [0.88–1.04] |

| >=2 | 0.97 [0.74–1.26] | 0.60 [0.53–0.67] |

| Urban/Rural status | ||

| Metropolitan county | REF | REF |

| Urban | 0.93 [0.75–1.16] | 1.28 [1.14–1.44] |

| Rural | 1.03 [0.61–1.73] | 1.16 [0.89–1.50] |

| Unknown | 1.18 [0.78–1.79] | 1.04 [0.85–1.28] |

| Disease Characteristics | ||

| ER/PR/HER-2 status | ||

| HR+/HER2+ | REF | N/A |

| HR+/HER2− | 0.92 [0.74–1.14] | N/A |

| HR−/HER2+ | 1.52 [0.91–2.53] | N/A |

| HR−/HER2− | 1.09 [0.78–1.52] | N/A |

| Unknown | 0.97 [0.75–1.27] | N/A |

| Tumor Grade | ||

| 1 | REF | REF |

| 2 | 1.30 [1.10–1.54] | 1.34 [1.26–1.43] |

| 3 | 1.36 [1.11–1.68] | 1.55 [1.37–1.75] |

| Unknown | 0.94 [0.64–1.36] | 0.65 [0.56–0.76] |

| Tumor Stage | ||

| T1 | REF | N/A |

| T2 | 1.22 [1.06–1.41] | N/A |

| Hospital Characteristics | ||

| Minority Serving Hospital | ||

| Yes | 1.31 [0.92–1.87] | 1.08 [0.84–1.37] |

| No | REF | REF |

| Facility Type | ||

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Center Program | REF | REF |

| Academic/Research | 0.93 [0.73–1.17] | 0.67 [0.56–0.80] |

| Community Cancer Program | 1.06 [0.80–1.40] | 1.01 [0.83–1.22] |

| Integrated Network Cancer Program | 0.75 [0.58–0.97] | 0.89 [0.74–1.06] |

| Facility Location | ||

| Northeast | 0.99 [0.77–1.26] | 0.57 [0.48–0.67] |

| Midwest | 1.13 [0.91–1.41] | 1.05 [0.90–1.23] |

| South | REF | REF |

| West | 0.93 [0.72–1.20] | 0.96 [0.80–1.15] |

| Hospital Volume | ||

| Low-Volume | REF | REF |

| Medium-Volume | 0.74 [0.60–0.93] | 0.96 [0.83–1.13] |

| High-Volume | 0.74 [0.55–1.00] | 0.86 [0.69–1.08] |

Abbreviations: ALND: axillary lymph node dissection; BCS: breast-conserving surgery; LN: lymph nodes; HR: hormone receptor; SLNB: sentinel lymph node biopsy

Figure 2a shows the relationship modeled by the restricted cubic splines model between annual hospital volume and the odds of receiving a SLNB at a given hospital. Similar to the ALND Omission cohort, lower hospital volume was associated with higher odds of receiving a SLNB, but with a more continuous downward trend. In adjusted models using hospital volume as a categorical variable, among patients eligible for SLNB omission, there was no significant difference by hospital volume (medium: OR 0.96, 95% CI [0.83–1.13]; high: OR 0.86, 95% CI [0.69–1.08]), despite results of the restricted cubic splines models.

In addition, in adjusted models, women who were ≥75 years were significantly less likely to undergo SLNB, compared to those 70–74 years (75–79 years: OR 0.59, 95% CI [0.54–0.64]; 80–84 years: OR 0.19, 95% CI [0.18–0.21]; ≥85 years: OR 0.05, 95% CI [0.04–0.05). Having no insurance or having non-private or non-government insurance was associated with lower odds of SLNB receipt (private: REF; none/other: 0.59, 95% CI [0.45–0.76]), as was having an income of <$40,000/year (<$40,000/year: REF, ≥$40,000: OR 1.16, 95% CI [1.05–1.29]). Increasing tumor grade was significantly associated with higher likelihood of SLNB receipt (grade 1: REF; grade 2: OR 1.34, 95% CI [1.26–1.43]; grade 3: OR 1.55, 95% CI [1.37–1.75]). Those with a CCI score of ≥2 were less likely to undergo a SLNB (OR 0.60, 95% CI [0.53–0.67]) than those with a CCI of 0. While minority-serving hospital status was not a significant factor, CoC facility type was, with patients treated at an academic/research facility being less likely to undergo SLNB than those treated at a comprehensive community cancer program (OR 0.67, 95% CI [0.56–0.80]). Patients treated in facilities located in the Northeast were significantly less likely than those treated in the South (OR 0.57, 95% CI [0.48–0.67]) to undergo SLNB.

Adjusted models stratified by BCS-only patients showed similar significant associations compared to models using the entire cohort, while adjusted models in mastectomy patients demonstrated that while SLNB use decreased with age (75–79 years: OR 0.84, 95% CI [0.56–1.25]; 80–84 years: OR 0.38, 95% CI [0.26–0.57]; ≥85 years: OR 0.10, 95% CI [0.07–0.15), insurance type, income, tumor grade, CCI, facility type, and geographic region were no longer significant (Supplemental Table 2).

ALND Omission Cohort

Unadjusted proportions (Table 2) demonstrate a downward trend from 2013–2016 in ALND rates in women eligible for omission (from 22.5% to 16.9%, p<0.001). Figure 3b shows unadjusted rates over time, stratified by age, demonstrating that ALND in all age groups decreased over time. Similarly, in adjusted models (Table 3), patients eligible for omission of ALND treated in years subsequent to 2013 were less likely to undergo ALND, with significantly decreasing odds in the latter years (2015: OR 0.82, 95% CI [0.69–0.99]; 2016: OR 0.65, 95% CI [0.54–0.78]).

Figure 3b:

Trends over Time in Axillary Lymph Node Dissection (ALND) in Patients ≥70 Years of Age with cT1–2N0, ≤2 Positive Lymph Nodes Undergoing Breast Conserving Surgery by Age

Restricted cubic splines models exploring the relationship between annual hospital volume and the odds of receiving ALND at a given hospital are shown in Figure 2b. Lower hospital volume was associated with higher odds of receiving an ALND, with relatively stable use in hospitals with an annual case volume greater than the median (i.e., 184 cases/year). In adjusted models using hospital volume as a categorical variable, patients eligible for omission of ALND treated at medium-volume hospitals were significantly less likely to undergo ALND than those treated at low-volume hospitals (medium: OR 0.74, 95% CI [0.60–0.93]; high: OR 0.74, 95% CI [0.55–1.00]), but not at high-volume hospitals. This relationship roughly follows the curves of the restricted cubic splines models.

Adjusted models also showed that women eligible for omission of ALND who were ≥85 years of age were as likely to undergo ALND as women 70–74 years of age (Table 3). Hispanic women were at slightly increased odds of undergoing ALND compared to non-Hispanic whites (OR 1.42, 95% CI [1.02–1.97]). No significant associations were seen between tumor subtype and ALND receipt, but higher tumor grade (grade 1: REF; grade 2: OR 1.30, 95% CI [1.10–1.54]; grade 3: OR 1.36, 95% CI [1.11–1.68]) and larger tumor size (T1: REF; T2: OR 1.22, 95% CI [1.06–1.41]) were associated with a higher likelihood of undergoing ALND. Neither facility location nor minority-serving hospital status were associated with ALND receipt, but patients seen at an integrated network cancer hospital had lower odds of undergoing ALND, compared to a comprehensive community cancer center program (OR 0.75, 95% CI [0.58–0.97).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that among women ≥70 years of age, use of low-value axillary surgery over time and its relationship with hospital volume differ by specific axillary surgical practice in question. Although the odds of undergoing a SLNB decreased significantly by year of diagnosis, the unadjusted rates of SLNB among those eligible for omission remained high over time (at approximately 84% overall). ALND rates, however, were much lower at the outset (20% overall) and significantly decreased over the study period. Our results also highlight the lack of significance in chronologic age in ALND use in contrast to the clear difference in SLNB use by age. The specific associations between axillary surgery practices and increasing annual hospital volume were different for ALND and SLNB, as illustrated by our restricted cubic splines models, but patients treated in low-volume hospitals had higher odds of undergoing an SLNB and ALND despite being eligible for omission.

ALND rates in patients undergoing BCS with cT1–2N0 disease have decreased dramatically since the early 2000s, with retrospective analyses showing rates of up to 85% of completion ALND prior to the publication of Z0011.26–30 Rates subsequently dropped to approximately 29.6% in the NCDB in 2012.30 Time from publication is not likely an important factor as the ACOSOG Z0011’s 5-year results were published in 20116 and 10-year follow-up published in 20175 and the 5-year results of CALGB 9343 were published in 2004, and 10-year results were published in 2013It is possible that the lack of change in SLNB rates stems from the fact that CALGB 9343, which is perhaps the most often cited trial in support of SLNB omission in older adults in the U.S., was designed as an omission of RT trial, not an omission of axillary surgery.

We also found that chronologic age was a significant factor in SLNB use amongst women eligible for omission, similar to previous studies.22,31,32 The significance of this finding, however, comes when contrasted with the lack of association with age in the ALND Omission cohort. That patients who are ≥85 years of age are just as likely as a patients who are 70–74 years of age to undergo an ALND when meeting Z0011 criteria, while patients ≥85 years of age are much less likely than patients 70–74 years of age to undergo a SLNB, begs the question of how chronologic and physiologic age have been evaluated and factored into treatment decision-making in recent years. In addition, greater comorbidity was associated with lower SLNB rates, but not ALND rates. Why comorbidities are not associated with decision-making in a procedure with higher morbidity warrants more investigation. In addition, the decision to omit an ALND after a positive SLNB is more traditionally surgeon-driven (i.e. ALND is not traditionally “offered” after a pathology report of ≤2 positive LNs), while the decision to omit SLNB in cT1N0 HR+ patients may viewed as one that is patient-sensitive, given that regional recurrence rates are nominally higher when axillary surgery is omitted.3 The magnitude of patient preference and self-perceived patient health as a contributor of SLNB rates thus deserves more scrutiny.

We also tested whether low-volume hospitals had higher rates of low-value care. Although the volume-quality relationship in surgery is more often attributed to the peri-operative care processes that develop around high-risk procedures at high-volume centers,33,34 association between higher hospital volume and lower breast cancer mortality is likely driven by different mechanisms (e.g., as Greenup et al.19 speculate, the complex multidisciplinary aspects of breast oncology require evaluation from a hospital-level, where the sum of the components of care are more likely more influential than any single provider). Our findings suggest that this volume-quality relationship might extend to certain low-value surgical practices as well; while these are decisions that could be attributable to a single surgeon, the anticipated adjuvant treatment decisions can influence surgical decision-making,35 thus making this question of low-value surgery relevant to a multidisciplinary arena. As is well-known in this body of literature, however, the volume-quality relationship can be very dependent on how hospital volume is defined.33 In our adjusted analyses examining hospital volume as a categorical variable, there was no significant difference between high-volume and low-volume hospitals with respect to ALND rates, and no significant association between volume and SLNB in the SLNB Omission population. However, our restricted cubic splines models illustrate that when volume is examined as a continuous variable, patients treated at very low volume hospitals (<200 cases/year) appear to have higher odds of undergoing an ALND and SLNB. In this range, hospital volume may represent the work of single high-volume surgeons in a given hospital or of multiple low-volume surgeons, thus rendering it unclear whether the practice of a single surgeon or a given hospital setting or culture is a better target for intervention.

Not only do barriers to de-implementation in these particular settings need to be explored (lack of knowledge of the Choosing Wisely recommendations, malpractice environment, financial incentives, or preferences of certain patient populations may all be significant factors), but effective interventions for low-volume hospitals also need to be developed. De-implementation interventions piloted in other settings have included patient cost-sharing, patient education, pay-for-performance measures, electronic health-record-based decision support tools, and clinician education.36,37 As our study illustrates, low-value care practices are unique and interventions must be tailored to their drivers. The fact that both axillary surgery practices seem to be more problematic at low-volume hospitals, may point away from patient preference as the sole driver, but more to clinician-controlled factors, at least in these environments. Although lack of knowledge may be driving this and that simple clinician education may be the key, but when explored in a cluster randomized trial, educational interventions were initially effective but the effects waned over time.38 Moreover, Smith et al, in their qualitative study examining barriers and facilitators to de-implementation practices in breast surgery, including Z0011 and CALGB 9343 practices, suggested that lack of knowledge was not a significant barrier.39 While this study mainly included high-volume surgeons, it supports the idea that the perception of the quality of the data supporting these practices is a larger problem than simple lack of knowledge.39 Successful de-implementation will likely need multi-level interventions, not only at the patient or provider level, but at the level of the health system as well. Complicating these efforts is the fact that the goal is not to get to zero. Multiple disease (e.g. extranodal extension), patient (e.g. patient preference or physiologic age), or treatment factors (e.g. need for nodal status to make adjuvant treatment decisions)35 may signal the need for a more aggressive approach. More detailed review of large experiences with these cohorts will be necessary to help to quantify what a truly “appropriate” rate may be.

Limitations

Limitations to our study include the following. First, variable coding the extent of axillary surgery in the NCDB may contain coding errors and inconsistencies that may have affected the results of our study. Second, certain factors that are not captured in this dataset (e.g., frailty status, functional status) could significantly factor into clinical decision-making. This supports the need for capture of geriatric-specific concerns in large datasets. Third, the NCDB captures data from CoC-accredited hospitals and patients with missing data were excluded from our cohorts; the study populations may thus not be representative of the whole U.S. population. Fourth, there exists no gold-standard for defining hospital volume in categorical terms and thus “low,” “medium”, and “high” designations may be considered largely arbitrary. This was, however, the reason behind including the restricted cubic splines models. Fifth, treatment decisions can turn on data that are not readily available (e.g., size of lymph node disease deposit, whether medical or radiation oncologists involved in patient care had input on surgical decision, patient preference). Finally, surgeon-volume and hospital-volume effects may be significantly intertwined but we are unable to extricate one from the other given the variables available in the NCDB.

Conclusion

While omission of ALND in eligible patients has decreased over time, omission of SLNB in eligible patients has been relatively static over time. Both practices appear to be more successfully de-escalated in higher-volume hospitals. While our findings reinforce the idea that de-implementation efforts should be practice-specific, interventions targeting lower volume CoC hospitals should be prioritized. Additional studies to identify effective practice-specific de-implementation strategies are needed.

Supplementary Material

SYNOPSIS.

The variation by hospital volume and over time in two axillary de-escalation surgical practices in older adults is described. SLNB rates remained static over time and after stratifying by age, but ALND rates decreased similarly across all age groups.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors have any relevant financial or commercial conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Rudenstam CM, Zahrieh D, Forbes JF, et al. Randomized trial comparing axillary clearance versus no axillary clearance in older patients with breast cancer: first results of International Breast Cancer Study Group Trial 10–93. J Clin Oncol. Jan 20 2006;24(3):337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Berry D, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women 70 years of age or older with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. Sep 2 2004;351(10):971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Bellon JR, et al. Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343. J Clin Oncol. Jul 1 2013;31(19):2382–2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martelli G, Boracchi P, Ardoino I, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in older patients with T1N0 breast cancer: 15-year results of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. Dec 2012;256(6):920–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giuliano AE, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al. Effect of Axillary Dissection vs No Axillary Dissection on 10-Year Overall Survival Among Women With Invasive Breast Cancer and Sentinel Node Metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. Sep 12 2017;318(10):918–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer and sentinel node metastasis: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. Feb 9 2011;305(6):569–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galimberti V, Cole BF, Viale G, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with breast cancer and sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23–01): 10-year follow-up of a randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. Oct 2018;19(10):1385–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donker M, van Tienhoven G, Straver ME, et al. Radiotherapy or surgery of the axilla after a positive sentinel node in breast cancer (EORTC 10981–22023 AMAROS): a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. Nov 2014;15(12):1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sávolt Á, Péley G, Polgár C, et al. Eight-year follow up result of the OTOASOR trial: The Optimal Treatment Of the Axilla - Surgery Or Radiotherapy after positive sentinel lymph node biopsy in early-stage breast cancer: A randomized, single centre, phase III, non-inferiority trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. Apr 2017;43(4):672–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Society of Surgical Oncology. Choosing Wisely. http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/sso-sentinel-node-biopsy-in-node-negative-women-70-and-over. Accessed May 3, 2019. 2016.

- 11.American Society of Breast Surgeons. https://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/american-society-of-breast-surgeons/. Accessed July 19, 2019.

- 12.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts and Figures. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2018.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2019..

- 13.Lucci A, McCall LM, Beitsch PD, et al. Surgical complications associated with sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND) plus axillary lymph node dissection compared with SLND alone in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Trial Z0011. J Clin Oncol. Aug 20 2007;25(24):3657–3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Advani PG, Lei X, Swanick CW, et al. Local Therapy Decisional Regret in Older Women With Breast Cancer: A Population-Based Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. Jun 1 2019;104(2):383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang T, Bredbeck BC, Sinco B, et al. Variations in Persistent Use of Low-Value Breast Cancer Surgery. JAMA Surg. Apr 1 2021;156(4):353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yen TWF, Li J, Sparapani RA, Laud PW, Nattinger AB. The interplay between hospital and surgeon factors and the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). Aug 2016;95(31):e4392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yen TW, Pezzin LE, Li J, Sparapani R, Laud PW, Nattinger AB. Effect of hospital volume on processes of breast cancer care: A National Cancer Data Base study. Cancer. May 15 2017;123(6):957–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coromilas EJ, Wright JD, Huang Y, et al. The Influence of Hospital and Surgeon Factors on the Prevalence of Axillary Lymph Node Evaluation in Ductal Carcinoma In Situ. JAMA Oncol. Jun 2015;1(3):323–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenup RA, Obeng-Gyasi S, Thomas S, et al. The Effect of Hospital Volume on Breast Cancer Mortality. Ann Surg. Feb 2018;267(2):375–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong AL, Pezzin LE, Nattinger AB. Identifying patterns of breast cancer care provided at high-volume hospitals: a classification and regression tree analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. Oct 2015;153(3):689–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallin K, Browner A, Palis B, et al. Incident Cases Captured in the National Cancer Database Compared with Those in U.S. Population Based Central Cancer Registries in 2012–2014. Ann Surg Oncol. Jun 2019;26(6):1604–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louie RJ, Gaber CE, Strassle PD, Gallagher KK, Downs-Canner SM, Ollila DW. Trends in Surgical Axillary Management in Early Stage Breast Cancer in Elderly Women: Continued Over-Treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. Mar 25 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. Jama. Feb 16 2011;305(7):675–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Joynt KE. Disparities in surgical 30-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. Ann Surg. Jun 2014;259(6):1086–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desquilbet L, Mariotti F. Dose-response analyses using restricted cubic spline functions in public health research. Stat Med. Apr 30 2010;29(9):1037–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caudle AS, Hunt KK, Tucker SL, et al. American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011: impact on surgeon practice patterns. Ann Surg Oncol. Oct 2012;19(10):3144–3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright GP, Mater ME, Sobel HL, et al. Measuring the impact of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 trial on breast cancer surgery in a community health system. Am J Surg. Feb 2015;209(2):240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le VH, Brant KN, Blackhurst DW, et al. The impact of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial: An institutional review. Breast. Oct 2016;29:117–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fillion MM, Glass KE, Hayek J, et al. Healthcare Costs Reduced After Incorporating the Results of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0011 Trial into Clinical Practice. Breast J. May 2017;23(3):275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard DH, Soulos PR, Chagpar AB, Mougalian S, Killelea B, Gross CP. Contrary To Conventional Wisdom, Physicians Abandoned A Breast Cancer Treatment After A Trial Concluded It Was Ineffective. Health Aff (Millwood). Jul 1 2016;35(7):1309–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Downs-Canner SM, Gaber CE, Louie RJ, et al. Nodal positivity decreases with age in women with early-stage, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer. Mar 15 2020;126(6):1193–1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dominici LS, Sineshaw HM, Jemal A, Lin CC, King TA, Freedman RA. Patterns of axillary evaluation in older patients with breast cancer and associations with adjuvant therapy receipt. Breast Cancer Res Treat. Jan 2018;167(2):555–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mesman R, Westert GP, Berden BJ, Faber MJ. Why do high-volume hospitals achieve better outcomes? A systematic review about intermediate factors in volume-outcome relationships. Health Policy. Aug 2015;119(8):1055–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pieper D, Mathes T, Neugebauer E, Eikermann M. State of evidence on the relationship between high-volume hospitals and outcomes in surgery: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Am Coll Surg. May 2013;216(5):1015–1025.e1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamirisa N, Thomas SM, Fayanju OM, et al. Axillary Nodal Evaluation in Elderly Breast Cancer Patients: Potential Effects on Treatment Decisions and Survival. Ann Surg Oncol. Oct 2018;25(10):2890–2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. Feb 9 2016;315(6):562–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colla CH, Mainor AJ, Hargreaves C, Sequist T, Morden N. Interventions Aimed at Reducing Use of Low-Value Health Services: A Systematic Review. Med Care Res Rev. Oct 2017;74(5):507–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharp AL, Hu YR, Shen E, et al. Improving antibiotic stewardship: a stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial. Am J Manag Care. Nov 1 2017;23(11):e360–e365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith ME, Vitous CA, Hughes TM, Shubeck SP, Jagsi R, Dossett LA. Barriers and Facilitators to De-Implementation of the Choosing Wisely(®) Guidelines for Low-Value Breast Cancer Surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. Aug 2020;27(8):2653–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.