This cohort study evaluates whether racial and ethnic disparities in incidence of triple-negative breast cancer among US women vary across states.

Key Points

Question

Are there state variations in racial and ethnic disparities in the incidence of female triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) in the US?

Findings

In this cohort study using population-based cancer registry data for 133 579 US women with TNBC, there were substantial state variations in racial and ethnic disparities in TNBC incidence, with Black women in Delaware, Missouri, Louisiana, and Mississippi experiencing the highest rates among all states and racial and ethnic populations.

Meaning

The findings suggest a role of social determinants of health in shaping the geographically patterned risk of TNBC and a need for more research to identify factors contributing to the state variations in disparity to develop effective preventive measures.

Abstract

Importance

There are few data on state variation in racial and ethnic disparities in incidence of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) in the US, limiting the ability to inform state-level health policy developments toward breast cancer equity.

Objective

To quantify between and within racial and ethnic disparities in TNBC incidence rates (IRs) among US women across states.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study using population-based cancer registry data included data for all women with TNBC diagnosed from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2019, identified in the US Cancer Statistics Public Use Research Database. Data were analyzed from July through November 2022.

Exposures

State and race and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Black, or non-Hispanic White) abstracted from medical records.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes were diagnosis of TNBC, age-standardized IR per 100 000 women, state-specific incidence rate ratios (IRRs) using the rate among White women in each state as a reference for between-population disparities, and state-specific IRRs using the race and ethnicity–specific national rate as a reference for within-population disparities.

Results

The study included data for 133 579 women; 768 (0.6%) were American Indian or Alaska Native; 4969 (3.7%), Asian or Pacific Islander; 28 710 (21.5%), Black; 12 937 (9.7%), Hispanic; and 86 195 (64.5%), White. The TNBC IR was highest among Black women (25.2 per 100 000 women), followed by White (12.9 per 100 000 women), American Indian or Alaska Native (11.2 per 100 000 women), Hispanic (11.1 per 100 000 women), and Asian or Pacific Islander (9.0 per 100 000 women) women. Racial and ethnic group–specific and state-specific rates substantially varied, ranging from less than 7 per 100 000 women among Asian or Pacific Islander women in Oregon and Pennsylvania to greater than 29 per 100 000 women among Black women in Delaware, Missouri, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Compared with White women, IRRs were statistically significantly higher in 38 of 38 states among Black women, ranging from 1.38 (95% CI, 1.10-1.70; IR, 17.4 per 100 000 women) in Colorado to 2.32 (95% CI, 1.90-2.81; IR, 32.0 per 100 000 women) in Delaware; lower in 22 of 22 states among Asian or Pacific Islander women, varying from 0.50 (95% CI, 0.34-0.70; IR, 5.7 per 100 000 women) in Oregon to 0.82 (95% CI, 0.75-0.90; IR, 10.5 per 100 000 women) in New York; and did not differ among Hispanic and American Indian or Alaska Native women in 22 of 35 states and 5 of 8 states, respectively. State variations within each racial and ethnic population were smaller but still substantial. For example, among White women, compared with the national rate, IRRs varied from 0.72 (95% CI, 0.66-0.78; IR, 9.2 per 100 000 women) in Utah to 1.18 (95% CI, 1.11-1.25; IR, 15.2 per 100 000 women) in Iowa, 1.15 (95% CI, 1.07-1.24; IR, 14.8 per 100 000 women) in Mississippi, and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.07-1.24; IR, 14.8 per 100 000 women) in West Virginia.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, there were substantial state variations in racial and ethnic disparities in TNBC incidence, with Black women in Delaware, Missouri, Louisiana, and Mississippi having the highest rates among all states and racial and ethnic populations. The findings suggest that more research is needed to identify factors contributing to the substantial geographic variations in racial and ethnic disparities in TNBC incidence to develop effective preventive measures and that social determinants of health contribute to the geographic disparities in TNBC risk.

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is an aggressive breast cancer subtype more frequently diagnosed among non-Hispanic Black women than other racial and ethnic populations in the US.1 It is unknown, however, whether the racial and ethnic disparity in TNBC risk differs by state, limiting our ability to inform state-level health policy for breast cancer equity. Prior studies on state-level TNBC incidence were limited by lower geographical coverage,1,2,3 lack of consideration of race and ethnicity,1 or exclusion of racial and ethnic minority groups other than Black and White populations.2,3 Furthermore, none of these studies reported on state variations in racial and ethnic disparities in TNBC rates. This study examined state variations in TNBC incidence rates (IRs) between and within racial and ethnic populations.

Methods

This cohort study using population-based cancer registry data was based on deidentified publicly available data and was therefore exempt from institutional review board approval or informed consent. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

We identified women of all ages with TNBC diagnosed from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2019, in the US Cancer Statistics Public Use Research Database,4 which includes incidence of cancer for 50 states and the Washington, DC (hereafter referred to collectively as states). Data from 2019 were the latest incidence data available for analysis after the data release in May 2022. Data were analyzed from July through November 2022. Triple-negative breast cancer was defined as estrogen receptor negative, progesterone receptor negative, and ERBB2 negative or equivocal.5 Race and ethnicity were abstracted from medical records (self-reported by patients or data inferred from health care practitioners) and classified into mutually exclusive categories of Hispanic, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic Black, or non-Hispanic White. For each population, states with fewer than 30 cases and Nevada (due to data quality concerns) were excluded, leaving 8, 22, 38, 35, and 50 states for American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic, White, and women, respectively.

Age-standardized (2000 US standard population) state-specific IRs of TNBC were calculated by race and ethnicity. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated to quantify disparities in state-specific rates using the rate among White women in each state as a reference for between-population disparities and using the race and ethnicity–specific national rate as a reference for within-population disparities. Spearman ρ was calculated to test correlations in state-specific rates between populations using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All other analyses were conducted using SEER*Stat, version 8.4.0 (National Cancer Institute). Two-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

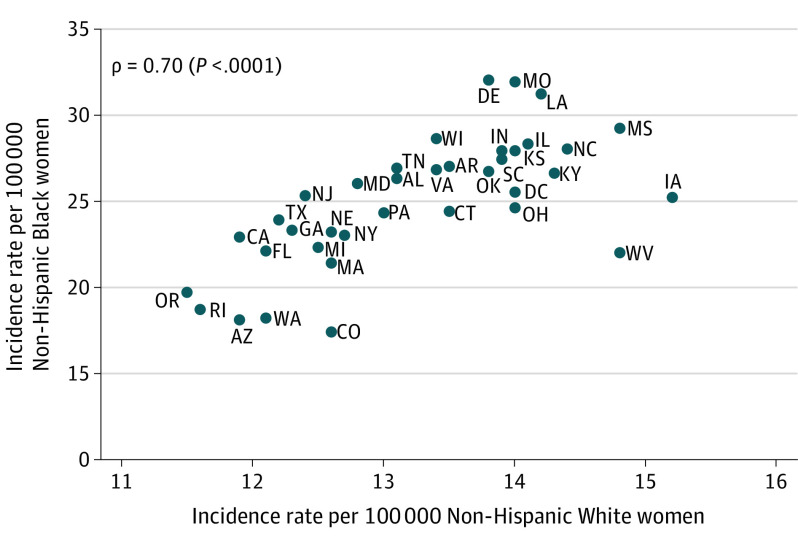

The study included data for 133 579 women; 768 (0.6%) were American Indian or Alaska Native; 4969 (3.7%), Asian or Pacific Islander; 28 710 (21.5%), Black; 12 937 (9.7%), Hispanic; and 86 195 (64.5%), White. Nationally, the TNBC IR was highest among Black women (25.2 per 100 000 women), followed by White (12.9 per 100 000 women), American Indian or Alaska Native (11.2 per 100 000 women), Hispanic (11.1 per 100 000 women), and Asian or Pacific Islander (9.0 per 100 000 women) women. eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 shows state-specific IR by race and ethnicity. There was substantial variation in IRs across states and race and ethnicity, ranging from less than 7 per 100 000 women among Asian or Pacific Islander women in Oregon and Pennsylvania to greater than 29 per 100 000 women among Black women in Delaware, Missouri, Louisiana, and Mississippi (case numbers and IRs are given in eTable 1 in Supplement 1). Despite the lack of data for several states, regional patterns were notable for Black and White women, with many Western states having lower rates. There was a strong correlation in state-specific rates between Black and White populations (ρ = 0.70; P < .001) (Figure 1; eFigure 2 in Supplement 1 gives all pairwise comparisons).

Figure 1. Correlation of State-Specific Incidence Rates of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Between Black and White Women in the US.

Spearman ρ was calculated to test correlations in state-specific rates between populations in 37 states and Washington, DC. Race and ethnicity in the US Cancer Statistics Public Use Research Database4 was based on information abstracted from medical records that was either self-reported by patients or data inferred from health care practitioners.

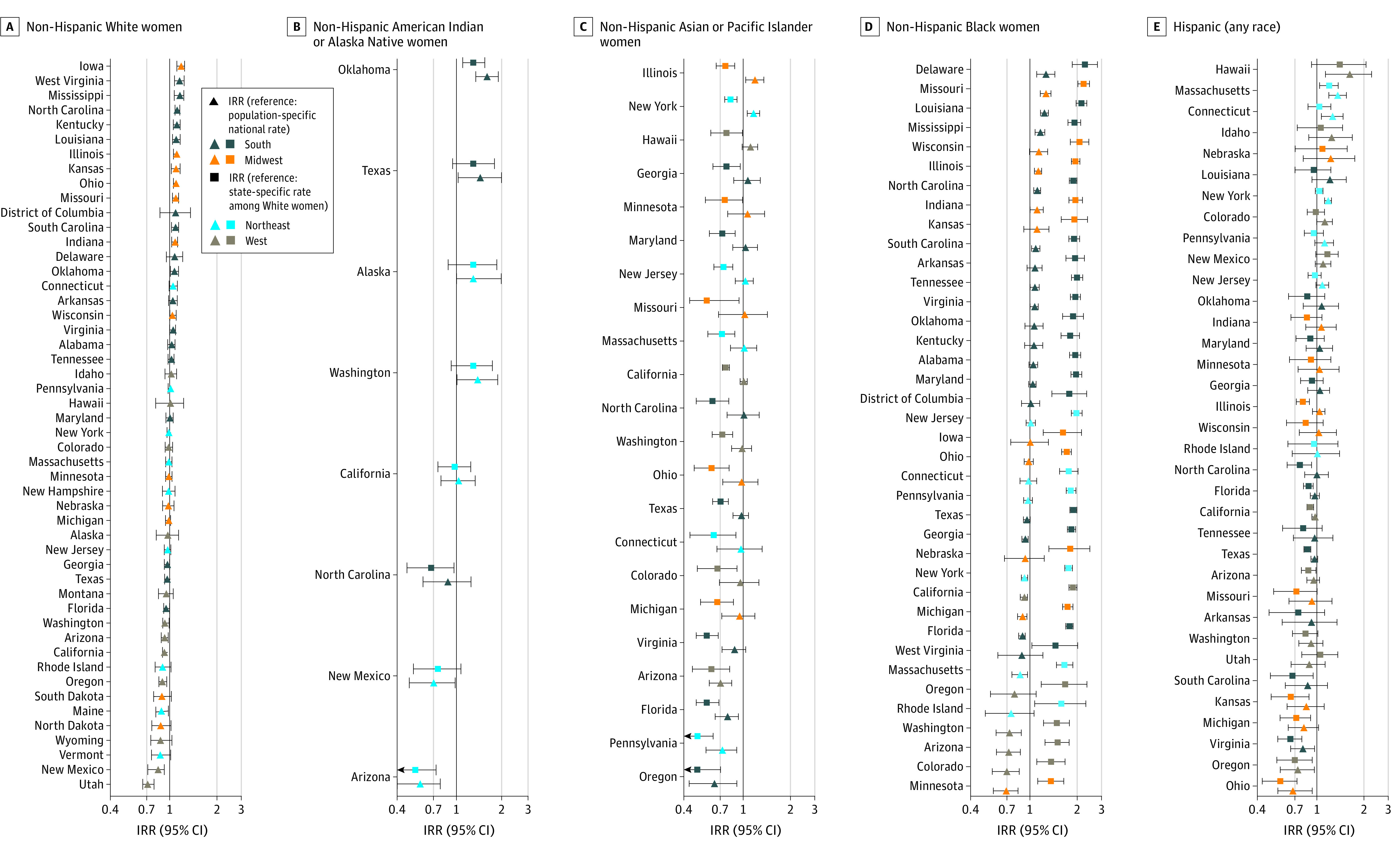

Figure 2 presents state variations in between-population and within-population disparities. Incidence rate ratios were statistically significantly higher among Black vs White women for 38 of 38 states, with the highest IRRs in Delaware (2.32; 95% CI, 1.90-2.81; IR, 32.0 per 100 000 women), Missouri (2.28; 95% CI, 2.08-2.50; IR, 31.9 per 100 000 women), and Louisiana (2.20; 95% CI, 2.02-2.38; IR, 31.2 per 100 000 women) (eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 1). Disparities between Black and White women were the smallest in Colorado (IRR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.10-1.70; IR, 17.4 per 100 000 women) and Minnesota (IRR = 1.38; 95% CI, 1.12-1.68; IR, 17.4 per 100 000 women). Contrarily, rates were statistically significantly lower among Asian or Pacific Islander women than among White women for 22 of 22 states with IRRs ranging from 0.50 (95% CI, 0.34-0.70; IR, 5.7 per 100 000 women) in Oregon to 0.82 (95% CI, 0.75-0.90; IR, 10.5 per 100 000 women) in New York. Incidence rate ratios did not differ between White and Hispanic women in 22 of 35 states or between White and American Indian or Alaska Native women in 5 of 8 states; however, compared with rates among White women, rates among Hispanic women were statistically significantly lower in 12 of 35 states and higher in Massachusetts, while those for American Indian or Alaska Native women were statistically significantly lower in North Carolina and Arizona and higher in Oklahoma.

Figure 2. State Variation in Within-Population and Between-Population Disparities in Incidence Rates (IRs) of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer in the US.

Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for within-population variation used the race and ethnicity–specific national rate as a reference, while IRRs for between-group disparities used the rate among White women in each state as a reference. Race and ethnicity in the US Cancer Statistics Public Use Research Database4 was based on information abstracted from medical records that were either self-reported by patients or data inferred from health care practitioners. All IRRs and 95% CIs are given in eTables 1 and 2 in Supplement 1.

Within-population variations were smaller but still substantial. For example, IRRs among White women compared with the national rate varied from 0.72 (95% CI, 0.66-0.78; IR, 9.2 per 100 000 women) in Utah to 1.18 (95% CI, 1.11-1.25; IR, 15.2 per 100 000 women) in Iowa, 1.15 (95% CI, 1.07-1.24; IR, 14.8 per 100 000 women) in Mississippi, and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.07-1.24; IR, 14.8 per 100 000 women) in West Virginia. Ranges in IRRs were 0.69 to 1.27 for Black women, 0.72 to 1.66 for Hispanic women, 0.64 to 1.19 for Asian or Pacific Islander women, and 0.57 to 1.60 for American Indian or Alaska Native women.

Discussion

Using nationwide, population-based cancer registry data, we found substantial state-level variations in racial and ethnic disparities in TNBC IRs, suggesting an important role of social determinants of health in these disparities. Accumulating evidence suggests that the legacy of racial discrimination and contemporary residential and economic segregation may jointly be associated with increased TNBC risk among Black women.6,7,8 For example, higher odds of having estrogen receptor–negative subtype was reported among Black women born in Jim Crow vs non–Jim Crow states before the Civil Rights Act of 19643 and those residing in socioeconomically deprived vs privileged areas.7,8 Therefore, the state variations in TNBC rates among Black women may reflect varying degrees of collective exposure to systematic racism by state. Intriguingly, states with the highest rates of TNBC among Black women (Missouri, Louisiana, and Mississippi) were also those with the highest rates among White women. This correlation suggests involvement of structural and environmental factors and merits further investigation with risk factor data at multiple levels and a rigorous ecosocial framework to better understand the association of social exposures with increased risk of TNBC.9,10

Differences in the prevalence of individual-level risk factors that have been associated with TNBC risk—breastfeeding,11 age at menarche,12,13 Western African ancestry14—may also partly explain the variations in TNBC rates by race and ethnicity and state. For example, breastfeeding has been consistently associated with lower TNBC risk.11 Nationally, the prevalence of breastfeeding initiation in 2019 was 90% among infants of Asian mothers followed by 87% among infants of Hispanic mothers, 86% among infants of White mothers, and 74% among infants of Black mothers11—the inverse order of TNBC rates by race and ethnicity. Particularly, states with the highest TNBC rates among Black women (Wisconsin, Illinois, Missouri, Mississippi, and Louisiana) coincided with those with the lowest breastfeeding initiation prevalence (54%-68%), below 88% in Colorado and Minnesota, where TNBC rates were lowest.11 Likewise, the prevalence among White women was 64% to 75% in West Virginia and Mississippi compared with 89% in Utah, the state with the lowest TNBC rate.11

Limitations

This study has several important limitations. A small number of cases resulted in wide 95% CIs for IRRs and precluded calculation of state-specific rates for racial and ethnic minority populations in many states. Additionally, the effect of likely nonrandom missing subtype information by race and ethnicity (8.1%-10.1%) and states (5.1%-13.4%) is unknown. Also, we were unable to separate ERBB2-equivocal and ERBB2-negative subtypes due to data constraints5 and, thus, potentially overestimated TNBC rates; however, the same definition was used across all states and races and ethnicities and should not have affected interpretations of findings. Furthermore, the proportion of the ERBB2-equivocal subtype among all cases was approximately 0% to 2% during the study period, and therefore the chance of misclassification should be small. State-level examination masks intrastate heterogeneity,6,15 and using aggregated racial and ethnic classifications obscures disparities in subpopulations, warranting future work with disaggregated data to inform locally relevant and culturally appropriate interventions. In addition, the descriptive nature of our study did not allow causal inference.

Conclusions

In this cohort study using population-based cancer registry data, there were substantial state variations in racial and ethnic disparities in IRs of TNBC, with Black women in Delaware, Missouri, Louisiana, and Mississippi having the highest rates among all states and racial and ethnic populations. These findings suggest a role of social determinants of health in these disparities and may encourage public health practitioners to identify specific regions and racial and ethnic groups on which to focus risk-reducing efforts. More research, however, is needed to elucidate factors contributing to these variations and to develop effective TNBC preventive measures, which may ultimately reduce disparities in breast cancer outcomes and lower the burden of death from breast cancer.

eTable 1. Case number, age-standardized incidence rates, between racial and ethnic group disparities in incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer by state in the United States, 2015-2019

eTable 2. Within-racial and ethnic group disparities in incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer by state in the United States, 2015-2019

eFigure 1. State-specific incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer by race and ethnicity in the United States

eFigure 2. Pairwise correlation in state-specific incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer among racial and ethnic populations in the United States, 2015-2019

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Kohler BA, Sherman RL, Howlader N, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2011, featuring incidence of breast cancer subtypes by race/ethnicity, poverty, and state. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(6):djv048. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss JL, Tatalovich Z, Zhu L, Morgan C, Cronin KA. Triple-negative breast cancer incidence in the United States: ecological correlations with area-level sociodemographics, healthcare, and health behaviors. Breast Cancer. 2021;28(1):82-91. doi: 10.1007/s12282-020-01132-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krieger N, Jahn JL, Waterman PD. Jim Crow and estrogen-receptor–negative breast cancer: US-born black and white non-Hispanic women, 1992-2012. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28(1):49-59. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0834-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Cancer Statistics Public Use Databases: Epidemiology and End Results Program SEER*Stat Database. Released June 2022. Accessed November 31, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/public-use

- 5.US Data Variable Definitions . U.S. Cancer Statistics Public Use Database. Extent of Disease – Collaborative Stage (CS). Merged estrogen receptor. Merged progesterone receptor. Merged HER2 summary. Accessed on Aug 16, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/public-use/dictionary/data-variable.htm?dataVarDesc=merged-her2-summary&dataVarAlt=merged-HER2&dbName=us

- 6.Wright E, Waterman PD, Testa C, Chen JT, Krieger N. Breast cancer incidence, hormone receptor status, historical redlining, and current neighborhood characteristics in Massachusetts, 2005-2015. J Natl Cancer Inst Cancer Spectr. 2022;6(2):pkac016. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkac016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barber LE, Zirpoli GR, Cozier YC, et al. Neighborhood disadvantage and individual-level life stressors in relation to breast cancer incidence in US Black women. Breast Cancer Res. 2021;23(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13058-021-01483-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin B, Babel RA, Plascak JJ, et al. Neighborhood social environmental factors and breast cancer subtypes among Black Women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(2):344-350. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falcinelli M, Thaker PH, Lutgendorf SK, Conzen SD, Flaherty RL, Flint MS. The role of psychologic stress in cancer initiation: clinical relevance and potential molecular mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2021;81(20):5131-5140. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-0684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dietze EC, Sistrunk C, Miranda-Carboni G, O’Regan R, Seewaldt VL. Triple-negative breast cancer in African-American women: disparities versus biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(4):248-254. doi: 10.1038/nrc3896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang KV, Li R, Anstey EH, Perrine CG. Racial and ethnic disparities in breastfeeding initiation—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(21):769-774. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7021a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krieger N, Kiang MV, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Beckfield J. Age at menarche: 50-year socioeconomic trends among US-born black and white women. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):388-397. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambrosone CB, Zirpoli G, Hong CC, et al. Important role of menarche in development of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer in African American women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(9):djv172. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman LA, Jenkins B, Chen Y, et al. Hereditary susceptibility for triple negative breast cancer associated with western Sub-Saharan African ancestry: results from an International Surgical Breast Cancer Collaborative. Ann Surg. 2019;270(3):484-492. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaels EK, Canchola AJ, Beyer KMM, Zhou Y, Shariff-Marco S, Gomez SL. Home mortgage discrimination and incidence of triple-negative and Luminal A breast cancer among non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White females in California, 2006-2015. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33(5):727-735. doi: 10.1007/s10552-022-01557-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Case number, age-standardized incidence rates, between racial and ethnic group disparities in incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer by state in the United States, 2015-2019

eTable 2. Within-racial and ethnic group disparities in incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer by state in the United States, 2015-2019

eFigure 1. State-specific incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer by race and ethnicity in the United States

eFigure 2. Pairwise correlation in state-specific incidence rates of triple-negative breast cancer among racial and ethnic populations in the United States, 2015-2019

Data Sharing Statement