Abstract

Introduction

The current study aimed to investigate the rates of anxiety, clinical depression, and suicidality and their changes in health professionals during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Materials and methods

The data came from the larger COMET-G study. The study sample includes 12,792 health professionals from 40 countries (62.40% women aged 39.76 ± 11.70; 36.81% men aged 35.91 ± 11.00 and 0.78% non-binary gender aged 35.15 ± 13.03). Distress and clinical depression were identified with the use of a previously developed cut-off and algorithm, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Chi-square tests, multiple forward stepwise linear regression analyses, and Factorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) tested relations among variables.

Results

Clinical depression was detected in 13.16% with male doctors and ‘non-binary genders’ having the lowest rates (7.89 and 5.88% respectively) and ‘non-binary gender’ nurses and administrative staff had the highest (37.50%); distress was present in 15.19%. A significant percentage reported a deterioration in mental state, family dynamics, and everyday lifestyle. Persons with a history of mental disorders had higher rates of current depression (24.64% vs. 9.62%; p < 0.0001). Suicidal tendencies were at least doubled in terms of RASS scores. Approximately one-third of participants were accepting (at least to a moderate degree) a non-bizarre conspiracy. The highest Relative Risk (RR) to develop clinical depression was associated with a history of Bipolar disorder (RR = 4.23).

Conclusions

The current study reported findings in health care professionals similar in magnitude and quality to those reported earlier in the general population although rates of clinical depression, suicidal tendencies, and adherence to conspiracy theories were much lower. However, the general model of factors interplay seems to be the same and this could be of practical utility since many of these factors are modifiable.

Keywords: COVID-19, Health professionals, Depression, Suicidality, Mental health, Conspiracy theories, Mental disorders, Psychiatry, Anxiety

Introduction

There are many reports in the literature suggesting that health professionals are at particular risk to experience a deterioration of their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [23]. Clinical depression, sleep disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was also reported both in the general population as well as in health care professionals (HCP) [55, 97]. Thus, while the COVID-19 pandemic started as an epidemic of an infectious agent, it soon gained a wider content and included all effects on all aspects of human life by this condition, even the overwhelming burst of information of questionable reliability and validity (‘infodemic’) [10]. The abuse of the terms ‘trauma’ and ‘PTSD’ is such an example. The vast majority of studies reported a ‘tsunami’-scale impact on mental health. It is highly possible that this could be an exaggeration [96]. In addition, changes to social behavior, as well as working conditions, daily habits, and routines have imposed secondary stress. Higher levels of anxiety, stress, and depressive feelings have been reported, but it seems that this depends on the temporal situation and the specific events; the response is by no means homogenous [37, 85, 96, 115], [75, 104]. Apart from the effect of the virus itself, in addition, changes in social behavior, as well as in working conditions, daily habits, and routine are expected to impose further stress, especially with the expectation of an upcoming economic crisis and possible unemployment. In this frame, mental health has gained a central position as an area that is expected to be affected by the pandemic because of its threatening nature as well as because of the profound impact on the everyday life of people. Especially concerning the later, it has been suggested that lockdowns triggered feelings of loneliness, irritableness, restlessness, and nervousness in the general population [90]. Especially the expectation of an upcoming economic crisis and possible unemployment were stressful factors. Conspiracy theories and maladaptive behaviors were also prevalent, compromising the public defense against the outbreak. The issue of increased suicidality as a consequence of extreme stress and depression has been raised again [25, 84].

At the end of the day, although are several empirical data papers, their methodology varies, it is very difficult to make comparisons among countries and it is also difficult to arrive at universally valid conclusions [55, 97]. Additionally, the literature is full of opinion papers, viewpoints, perspectives, guidelines, and narrations of activities to cope with the pandemic. These borrow from previous experiences with different pandemics and utilize common sense, but, as a result, they often obscure rather than clarify the landscape. The role of mass and social media has been discussed but remains poorly understood in empirical terms.

An early meta-analysis reported high rates of anxiety (25%) and depression (28%) in the general population [86] while a second one reported that 29.6% of people experienced stress, 31.9% anxiety and 33.7% depression [92]. Not only do we need more reliable and valid data, but we also need to identify risk and protective factors to be able to recommend measures that will eventually improve public health by preventing the adverse impact on mental health and simultaneously improve health-related behaviors [4, 47, 73, 75].

The aim of the current study was to investigate the rates of anxiety, clinical depression, and suicidality and their changes in health professionals aged 18–69 internationally, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The secondary aims were to investigate their relations with several personal, interpersonal/social, and lifestyle variables. The aim also included the investigation of the spreading of conspiracy theories concerning the COVID-19 outbreak and their relationship with mental health in this specific population group.

Materials and methods

Methods

The protocol used is available in the webappendix; each question was given an ID code; these ID codes were used throughout the results for increased accuracy.

According to a previously developed method, [39, 40, 42] the cut-off score of 23/24 for the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale and a derived algorithm were used to identify cases of clinical depression. This algorithm utilized the weighted scores of selected CES-D items to arrive at the diagnosis of clinical depression, and has already been validated. Cases identified by only either method were considered cases of distress (false positive cases in terms of depression), while cases identified by both the cut-off and the algorithm were considered as clinical depression. The State-Trate Anxiety Inventory-State form (STAI-S) [100] and the Risk for Assessment of Suicidality Scale (RASS) [42] were used to assess anxiety and suicidality respectively.

The data were collected online and anonymously from April 2020 through March 2021, covering periods of full implementation of lockdowns as well as of relaxations of measures in countries around the world. Announcements and advertisements were done on the social media and through news sites, but no other organized effort had been undertaken. The first page included a declaration of consent which everybody accepted by continuing with the participation.

Approval was initially given by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, and locally concerning each participating country.

Materials

The data came from the larger COMET-G study [41].

The study population was self-selected. It was not possible to apply post-stratification on the sample as it was done in a previous study [40], because this would mean that we would utilize a similar methodology across many different countries and the population data needed were not available for all.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests were used for the comparison of frequencies when categorical variables were present and for the post hoc analysis of the results a Bonferroni-corrected method of pair-wise comparisons was utilized [69].

Factorial Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test for the main effect as well as the interaction among grouping variables concerning continuous variables. The Scheffe test was used as the post-hoc test.

Multiple forward stepwise linear regression analysis (MFSLRA) was performed to investigate which variables could function as predictors and contribute to the development of others (e.g. clinical depression).

To correct for multiple comparisons, the level of p<0.001 was accepted as the level of significance for ANOVA and MFSLRA results (but not for post-hoc tests)

Results

Demographics

From the 55,589 responses from 40 countries (Table 1) of the COMET study, 23.01% reported they were working in the health field. Thus, the study sample of the current paper includes 12,792 health professionals (N = 7983–62.40% women aged 39.76 ± 11.70; N = 4709–36.81% men aged 35.91 ± 11.00 and N = 100–0.78% non-binary gender aged 35.15 ± 13.03). The contribution of each country and the gender and age composition are shown in Table 1. The sex-by-specific occupation composition is shown in Table 2. The sociodemographic characteristics are shown in webtables 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 of the appendix. Details concerning various sociodemographic variables (marital status, education, work, etc. are shown in the webappendix, in webtables 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9).

Table 1.

List of participating countries by sex, with number of subjects and mean age

| Country | Men | Women | Non-binary gender | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Age | Age | ||||||||||||

| N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | Mean | SD | N | % | |

| Argentina | 439 | 20.14 | 44.53 | 14.39 | 1725 | 79.13 | 40.60 | 14.49 | 16 | 0.73 | 37.44 | 17.29 | 2180 | 3.92 |

| Australia | 21 | 30.43 | 33.67 | 8.05 | 48 | 69.57 | 32.63 | 7.89 | 0.00 | 69 | 0.12 | |||

| Azerbaijan | 70 | 19.89 | 36.20 | 10.33 | 280 | 79.55 | 37.71 | 11.46 | 2 | 0.57 | 26.00 | 0.00 | 352 | 0.63 |

| Bangladesh | 1681 | 55.42 | 24.09 | 5.24 | 1333 | 43.95 | 23.98 | 5.48 | 19 | 0.63 | 27.42 | 8.88 | 3033 | 5.46 |

| Belarus | 200 | 18.30 | 38.62 | 12.46 | 893 | 81.70 | 39.15 | 11.11 | 0.00 | 1093 | 1.97 | |||

| Brazil | 86 | 40.19 | 31.36 | 13.06 | 127 | 59.35 | 28.80 | 9.97 | 1 | 0.47 | 31.00 | 214 | 0.38 | |

| Bulgaria | 202 | 26.47 | 558 | 73.13 | 3 | 0.39 | 763 | 1.37 | ||||||

| Canada | 142 | 27.73 | 42.24 | 15.49 | 367 | 71.68 | 42.57 | 14.00 | 3 | 0.59 | 46.33 | 17.79 | 512 | 0.92 |

| Chile | 86 | 26.71 | 40.76 | 15.43 | 234 | 72.67 | 39.57 | 15.08 | 2 | 0.62 | 42.50 | 16.26 | 322 | 0.58 |

| Croatia | 1041 | 35.91 | 41.73 | 11.70 | 1835 | 63.30 | 42.32 | 11.84 | 23 | 0.79 | 44.26 | 13.75 | 2899 | 5.22 |

| Egypt | 24 | 14.55 | 37.38 | 14.18 | 141 | 85.45 | 39.66 | 11.82 | 0.00 | 165 | 0.30 | |||

| France | 64 | 24.33 | 38.98 | 14.70 | 197 | 74.90 | 37.89 | 15.53 | 2 | 0.76 | 27.50 | 10.61 | 263 | 0.47 |

| Georgia | 48 | 11.59 | 30.77 | 6.82 | 364 | 87.92 | 32.06 | 9.04 | 2 | 0.48 | 33.50 | 6.36 | 414 | 0.74 |

| Germany | 15 | 25.00 | 48.93 | 18.58 | 45 | 75.00 | 34.87 | 13.98 | 0.00 | 60 | 0.11 | |||

| Greece | 624 | 18.26 | 36.55 | 10.58 | 2772 | 81.10 | 34.00 | 9.87 | 22 | 0.64 | 29.59 | 6.68 | 3418 | 6.15 |

| Honduras | 74 | 33.48 | 28.19 | 7.17 | 147 | 66.52 | 32.05 | 11.09 | 0.00 | 221 | 0.40 | |||

| Hungary | 146 | 19.13 | 44.60 | 11.95 | 617 | 80.87 | 41.36 | 11.95 | 0.00 | 763 | 1.37 | |||

| India | 3044 | 61.01 | 33.51 | 8.94 | 1917 | 38.42 | 31.59 | 11.97 | 28 | 0.56 | 28.36 | 7.86 | 4989 | 8.97 |

| Indonesia | 909 | 27.68 | 33.64 | 12.06 | 2358 | 71.80 | 30.49 | 11.42 | 17 | 0.52 | 28.00 | 11.62 | 3284 | 5.91 |

| Israel | 28 | 19.44 | 48.79 | 18.24 | 116 | 80.56 | 38.97 | 13.56 | 0.00 | 144 | 0.26 | |||

| Italy | 257 | 26.22 | 43.10 | 16.17 | 717 | 73.16 | 41.22 | 14.17 | 6 | 0.61 | 42.17 | 21.14 | 980 | 1.76 |

| Japan | 182 | 70.00 | 45.31 | 11.61 | 78 | 30.00 | 41.71 | 11.10 | 0.00 | 260 | 0.47 | |||

| Kyrgyz Republic | 614 | 27.76 | 36.38 | 14.16 | 1561 | 70.57 | 38.87 | 14.58 | 37 | 1.67 | 33.57 | 12.60 | 2212 | 3.98 |

| Latvia | 1036 | 39.72 | 48.18 | 12.38 | 1570 | 60.20 | 45.26 | 14.64 | 2 | 0.08 | 48.00 | 18.38 | 2608 | 4.69 |

| Lithuania | 271 | 21.54 | 39.34 | 13.62 | 983 | 78.14 | 40.16 | 12.75 | 4 | 0.32 | 40.75 | 12.89 | 1258 | 2.26 |

| Malaysia | 311 | 32.29 | 41.95 | 12.08 | 578 | 60.02 | 39.24 | 11.71 | 74 | 7.68 | 39.03 | 12.66 | 963 | 1.73 |

| Mexico | 447 | 25.03 | 36.84 | 16.13 | 1332 | 74.58 | 38.18 | 14.74 | 7 | 0.39 | 22.86 | 4.78 | 1786 | 3.21 |

| Nigeria | 752 | 65.22 | 30.30 | 7.46 | 397 | 34.43 | 25.83 | 7.55 | 4 | 0.35 | 31.75 | 7.97 | 1153 | 2.07 |

| Pakistan | 575 | 28.24 | 25.46 | 6.35 | 1445 | 70.97 | 23.45 | 4.42 | 16 | 0.79 | 24.75 | 10.93 | 2036 | 3.66 |

| Peru | 56 | 36.13 | 43.80 | 15.80 | 99 | 63.87 | 38.72 | 14.03 | 0.00 | 155 | 0.28 | |||

| Poland | 286 | 18.58 | 33.46 | 11.54 | 1239 | 80.51 | 33.65 | 11.24 | 14 | 0.91 | 31.21 | 14.67 | 1539 | 2.77 |

| Portugal | 16 | 18.82 | 43.31 | 18.22 | 68 | 80.00 | 42.34 | 13.77 | 1 | 1.18 | 38.00 | 85 | 0.15 | |

| Romania | 293 | 20.22 | 47.54 | 14.45 | 1144 | 78.95 | 46.77 | 14.21 | 12 | 0.83 | 51.58 | 15.45 | 1449 | 2.61 |

| Russia | 3825 | 38.50 | 30.34 | 12.03 | 5847 | 58.85 | 31.74 | 12.25 | 264 | 2.66 | 27.64 | 10.87 | 9936 | 17.87 |

| Serbia | 152 | 25.08 | 39.16 | 11.94 | 453 | 74.75 | 41.84 | 11.77 | 1 | 0.17 | 58.00 | 606 | 1.09 | |

| Spain | 330 | 31.82 | 51.49 | 14.85 | 703 | 67.79 | 48.52 | 13.53 | 4 | 0.39 | 50.00 | 13.11 | 1037 | 1.87 |

| Turkey | 95 | 27.38 | 25.03 | 6.26 | 249 | 71.76 | 25.05 | 7.36 | 3 | 0.86 | 21.33 | 0.58 | 347 | 0.62 |

| Ukraine | 306 | 21.07 | 38.42 | 15.38 | 1132 | 77.96 | 39.09 | 13.13 | 14 | 0.96 | 35.93 | 17.88 | 1452 | 2.61 |

| UK | 55 | 34.38 | 43.53 | 11.12 | 105 | 65.63 | 44.56 | 11.95 | 0.00 | 160 | 0.29 | |||

| USA | 124 | 30.32 | 37.50 | 15.47 | 273 | 66.75 | 37.78 | 14.51 | 12 | 2.93 | 28.00 | 9.78 | 409 | 0.74 |

| Total | 18,927 | 34.05 | 34.90 | 13.29 | 36,047 | 64.85 | 35.80 | 13.61 | 615 | 1.11 | 31.64 | 13.15 | 55,589 | 100.00 |

Table 2.

Sex-by-occupation composition and rates of clinical depression and distress

| % | Age | Distress % | Clinical depression % | Distress plus clinical depression (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||||

| Administrative staff in hospital (4.10%) | ||||||

| Women | 64.35 | 40.29 | 11.14 | 12.28 | 17.37 | 29.64 |

| Men | 34.10 | 38.01 | 10.83 | 13.56 | 15.82 | 29.38 |

| Non-binary gender | 1.54 | 39.00 | 12.42 | 37.50 | 37.50 | 75.00 |

| Total | 13.10 | 17.15 | 30.25 | |||

| Doctor (42.66%) | ||||||

| Women | 70.70 | 39.88 | 11.84 | 15.36 | 15.23 | 30.60 |

| Men | 28.67 | 40.21 | 13.42 | 14.03 | 7.89 | 21.91 |

| Non-binary gender | 0.63 | 37.35 | 15.25 | 35.29 | 5.88 | 41.18 |

| Total | 15.11 | 13.07 | 28.17 | |||

| Nurse (10.89%) | ||||||

| Women | 87.22 | 41.11 | 11.90 | 14.49 | 16.65 | 31.14 |

| Men | 12.20 | 34.99 | 11.25 | 16.67 | 11.31 | 27.98 |

| Non-binary gender | 0.58 | 32.00 | 12.74 | 0.00 | 37.50 | 37.50 |

| Total | 14.67 | 16.12 | 30.79 | |||

| Other healthcare profession (36.21%) | ||||||

| Women | 44.97 | 38.77 | 11.31 | 15.69 | 14.81 | 30.50 |

| Men | 54.36 | 33.34 | 7.87 | 14.54 | 9.60 | 24.15 |

| Non-binary gender | 0.68 | 36.35 | 11.57 | 29.03 | 16.13 | 45.16 |

| Total | 15.16 | 11.99 | 27.15 | |||

| Other hospital staff (6.14%) | ||||||

| Women | 60.05 | 39.35 | 11.78 | 17.38 | 15.45 | 32.83 |

| Men | 37.63 | 34.40 | 12.43 | 18.84 | 14.38 | 33.22 |

| Non-binary gender | 2.32 | 28.61 | 9.58 | 33.33 | 22.22 | 55.56 |

| Total | 18.30 | 15.21 | 33.51 | |||

| Total study sample | ||||||

| Women | 62.40 | 39.76 | 11.70 | 15.30 | 15.44 | 30.75 |

| Men | 36.81 | 35.91 | 11.00 | 14.68 | 9.63 | 24.31 |

| Non-binary gender | 0.78 | 35.15 | 13.03 | 30.30 | 17.17 | 47.47 |

| Total | 100.00 | 38.31 | 11.61 | 15.19 | 13.31 | 28.50 |

History of health

Moderate or bad somatic health was reported by 16.70% and the presence of a chronic medical somatic condition was reported by 21.29%. Detailed results are shown in webtable 8. Being either relatives or caretakers of vulnerable persons was reported by 46.88% (webtable 9).

In terms of mental health history and self-harm, 8.59% had a prior history of an anxiety disorder, 10.93% of depression, 0.71% of Bipolar disorder, 0.42% of psychosis, and 2.90% of other mental disorder. Any mental disorder history was present in 23.58%. At least once, 17.20% had hurt themselves in the past and 8.20% had attempted at least once in the past. The detailed rates by sex and country are shown in webtable 10.

Family

In terms of family status, 57.86% were married, 60.02% had at least one child and only 11.42% were living alone. The responses suggested an increased need for communication with family members in 41.79%, an increased need for emotional support in 30.26%, fewer conflicts in 37.36% and increased conflicts within families for 17.77%, an improvement of the quality of relationships in 25.62%, while in most cases (90.18%) there was maintenance of basic daily routine at least somehow (webtable 11). During lockdowns 80.81% continued to work, while 47.65% expected their economic situation to worsen because of the COVID-19 outbreak (webtable 12).

Present mental health

Concerning mental health, data 47.15% reported an increase in anxiety, and 39.95% reported a worsening in depressive affect. Suicidal thoughts were increased in 10.48%. Overall, current clinical depression was present in 13.16% of the study sample (unweighted average) with male doctors and ‘non-binary genders’ having the lowest rates (7.89 and 5.88%, respectively) and ‘non-binary gender’ nurses and administrative staff having the highest (37.50%). In detail, the results are shown in Table 2. However, after taking into consideration the expected rates of current clinical depression in the population, men with positive history had the highest Relative Risk (RR = 6.47) while the lowest was observed in women without a history of mental disorder (RR = 1.81). Additionally, distress was present in 15.19%, with the highest rates being for ‘non-binary genders’ (> 30%) and the lowest for female administrative staff (12.28%). The complete rates by sex and occupation are shown in webtable 17.

Suicidal tendencies doubled according to RASS subscales scores (webtable 17) and in comparison to what is expected [42].

Persons with a history of mental disorders had higher rates of current clinical depression (24.64% vs. 9.62%, chi-square test = 454.90; df = 1; p < 0.0001) (webtable 14). In persons without mental health history, the RR ranged from 2.14 to 2.90. In persons with a mental health history, the RR was highest in those with a psychotic history (Bipolar disorder RR = 9.04; Psychosis RR = 8.08) and ranged between 3.82 and 6.40 for non-psychotic history, with the lowest RR in persons with a history of ‘other mental disorder’, in comparison to the expected prevalence of depression (3% for men and 6% for women). Of women with clinical depression, half were new cases (without any past history of mental disorder) while this was true for two thirds of men. Taking into consideration that the pandemic increased the risk by definition, the risk to develop clinical depression during the pandemic when having a previous history was highest for bipolar disorder (RR = 4.23), while the previous history of self-harm or suicidal attempts did not increase the risk (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relative Risk (RR) to develop clinical depression vs. participants with no mental health history and no history of self-harm or suicidal acts

| History | Risk to develop clinical depression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| When alone | When history of self-harm/attempt is also present | |||

| % | RR | % | RR | |

| No previous history at all | 9.62 | 1.00 | 1.0 | |

| Any mental disorder | 31.81 | 3.31 | 29.87 | 3.11 |

| Anxiety | 19.93 | 2.07 | 29.49 | 3.07 |

| Clinical depression | 28.81 | 2.99 | 30.46 | 3.17 |

| Bipolar disorder | 40.66 | 4.23 | 30.78 | 3.20 |

| Psychosis | 36.36 | 3.78 | 30.93 | 3.22 |

| Other | 17.20 | 1.79 | 30.52 | 3.17 |

| Only history of self-harm/attempt | 17.89 | 1.86 | ||

The mean scale scores were 43.52 ± 11.99 for the STAI-S, 19.36 ± 8.17 for the CES-D, and 70.23 ± 134.74 for the Intention subscale of the RASS. The complete results by sex and country are shown in webtable 17.

From the total sample, 5.17% reported that they often thought much or very much about committing suicide if they had the chance. Men and women had similar rates (5.76% vs. 4.69%) but those self-identified as ‘non-binary gender’ had much higher rates (17.00%). In subjects with a history of psychotic disorder or self-harm/attempt the rate was 15.45% while in those with a history of non-psychotic disorder, it was 9.76%. In persons free of any mental disorder or self-harm/attempt history the rate was as low as 2.09%. This means that the RR for the manifestation of at least moderate suicidal thoughts was equal to 7.4 for psychotic history and 3.7 for non-psychotic history. In those identified as ‘non-binary gender’, the RR was approximately equal to 3.5.

Beliefs in conspiracy theories

Approximately one third of responders accepted at least a moderate degree some non-bizarre conspiracy theory. The acceptance of inflated death rates was 44.24% while that of the 5G antenna theory was 20.81%. Doctors had the lowest rates, but impressively, 37.6% of doctors and 50.86% of nurses reported they were believing in the deliberate inflation of death rates by governments and 14.75% and 27.22% respectively were accepting the 5G theory. In detail, the responses by sex and country are shown in webtable 21.

Modeling of mental health changes during the pandemic

The presence of any mental health history acted as a risk factor for the development of current clinical depression with all chi-square tests being significant at p < 0.001. Interestingly a history of self-harm or suicidality emerged as a risk factor even for persons without reporting mental health history. In persons with only a history of self-harm or suicidality, 17.89% developed clinical depression. The combination of both self-harm and suicidal attempts history with specific mental health history revealed that subjects without any such history at all had the lowest rate or current clinical depression (9.62%), while the presence of previous self-harm/attempts increased the risk in subjects with past anxiety (29.49%) and other mental disorders (30.52%), but not clinical depression (30.46%), Bipolar disorder (30.78%) and psychoses (30.93%). The highest relative risk (RR) was calculated for history of Bipolar disorder but history of self-harm/attempt played no role (RR = 4.23). All RR values are shown in Table 2 and webtable 22. After taking into consideration that the annual incidence of depression is 0.3% [66], the calculated risk because of the pandemic for the health professionals population to develop clinical depression is RR = 30 Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Map of the 40 participating countries

The presence of a chronic somatic condition acted as a significant but weak risk factor for the development of clinical depression (Chi-square = 14.61, df = 1, p < 0.001; In terms of rates, 15.35% of those with a chronic somatic condition manifested clinical depression vs. 12.56% of those without (RR = 1.22).

The results of the MFSLRA suggested that a significant number of variables acted either as risk or as protective factors (Table 4, Fig. 2, webtable 23). These factors explained 16.1% of the change in anxiety, 11.6% of change in depressive affect, 19.1% of the development of distress or clinical depression, and 5.1% of change in suicidal thoughts. The individual contribution of each predictor separately was very small (many b coefficients were very close to zero).

Table 4.

Results of four separate Multiple Forward Stepwise Linear Regression Analysis (MFSLRA) with change in anxiety (F21), change in depressive affect (G21), change in suicidal thoughts (O11) and the development of distress or clinical depression as dependent variables

| Change in anxiety (F21)R2 = 0.161; F (25, 12,620) = 97.286 p < < 0.0001; SE of est: 0.809 | Change in depressive affect (G21) R2 = 0.116; F (25, 12,620) = 66.742 p < < 0.0001; SE of est: 0.827 | Development of distress or clinical depression R2 = 0.191; F(31,12,611) = 93.466 p < < 0.0001; SE of est: 0.640 | Change in suicidal thoughts (O11) R2 = 0.051; F (31,12,614) = 22.282 p < < 0.0001; SE of est: 0.770 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | t | p | b | SE | t | p | b | SE | t | p | b | SE | t | p | |

| Intercept | – 0.87 | 0.06 | – 14.49 | < 0.001 | – 0.75 | 0.06 | – 11.95 | < 0.001 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 14.31 | < 0.001 | 0.44 | 0.06 | 7.24 | < 0.001 |

| Demographics | ||||||||||||||||

| Sex (A1)- ‘non-binary gender’ was not included | 0.06 | 0.02 | 3.88 | < 0.001 | – 0.04 | 0.01 | – 3.02 | 0.003 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 3.98 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Age (A2) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.23 | 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.67 | < 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – 4.00 | < 0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00 | – 3.79 | < 0.001 |

| Number of persons in household (A5) | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 2.99 | 0.003 | ||||||||||||

| Education level (A7) | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 2.23 | 0.026 | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 2.42 | 0.016 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.02 | 0.044 | ||||

| Work and finance | ||||||||||||||||

| Continue to work during lockdown (A11) | ||||||||||||||||

| Change in economic situation (E7) | 0.10 | 0.01 | 14.02 | < 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 15.11 | < 0.001 | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 3.15 | 0.002 | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 2.58 | 0.010 |

| Health | ||||||||||||||||

| Condition of general health (B1) | 0.10 | 0.01 | 13.90 | < 0.001 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 10.55 | < 0.001 | – 0.09 | 0.01 | – 15.30 | < 0.001 | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 3.29 | 0.001 |

| Presence of a chronic medical condition (B2) | ||||||||||||||||

| Family/social | ||||||||||||||||

| Being a carer of a person belonging to a vulnerable group (B4) | – 0.04 | 0.02 | – 2.60 | 0.009 | – 0.04 | 0.01 | – 2.98 | 0.003 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 2.57 | 0.010 | ||||

| Conflicts within family (E3) | – 0.03 | 0.01 | – 4.53 | < 0.001 | – 0.04 | 0.01 | – 5.21 | < 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 7.37 | < 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 8.30 | < 0.001 |

| Change in quality of relationships within family (E4) | 0.12 | 0.01 | 12.27 | < 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 15.33 | < 0.001 | – 0.02 | 0.01 | -3.24 | 0.001 | – 0.06 | 0.01 | – 6.67 | < 0.001 |

| Keeping a basic routine during lockdown (E5) | 0.11 | 0.01 | 12.78 | < 0.001 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 11.46 | < 0.001 | – 0.10 | 0.01 | – 14.79 | < 0.001 | – 0.05 | 0.01 | – 5.81 | < 0.001 |

| Changes in religiousness/spirituality (P1) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.63 | 0.009 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.22 | 0.026 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 4.99 | < 0.001 | – 0.05 | 0.01 | – 6.22 | < 0.001 |

| Mental health history | ||||||||||||||||

| History of anxiety (B5) | – 0.14 | 0.03 | – 5.37 | < 0.001 | – 0.12 | 0.03 | – 4.39 | < 0.001 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 9.37 | < 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 2.03 | 0.042 |

| History of depression (B5) | – 0.10 | 0.02 | – 4.14 | < 0.001 | – 0.13 | 0.02 | – 5.45 | < 0.001 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 18.61 | < 0.001 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 2.95 | 0.003 |

| History of psychosis (B5) | 0.37 | 0.09 | 4.26 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| History of bipolar disorder (B5) | 0.44 | 0.07 | 6.36 | < 0.001 | – 0.19 | 0.08 | – 2.28 | 0.023 | ||||||||

| History of other mental disorder (B5) | – 0.20 | 0.04 | – 4.50 | < 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 4.46 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| History of self-harm (O12) | – 0.05 | 0.02 | – 2.66 | 0.008 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 9.63 | < 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2.48 | 0.013 | ||||

| History of suicidal attempt (O13) | 0.14 | 0.02 | 5.65 | < 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 3.87 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| The effect of the pandemic | ||||||||||||||||

| Fears of getting COVID-19 (C1) | – 0.10 | 0.01 | – 12.09 | < 0.001 | – 0.05 | 0.01 | – 6.41 | < 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 8.69 | < 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.08 | 0.037 |

| Fears that a member of the family will get COVID-19 and die (C3) | – 0.08 | 0.01 | – 11.22 | < 0.001 | – 0.04 | 0.01 | – 6.35 | < 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 9.92 | < 0.001 | – 0.01 | 0.01 | – 2.24 | 0.025 |

| Time spent outside of house during lockdown (D1) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.89 | < 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.21 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Currently locked up in the house (D2) | – 0.03 | 0.01 | – 4.03 | < 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.05 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| Satisfaction by availability of information (D4) | 0.06 | 0.01 | 8.09 | < 0.001 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 7.88 | < 0.001 | – 0.06 | 0.01 | – 8.12 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Beliefs in conspiracy theories | ||||||||||||||||

| The vaccine was ready before the virus broke out and they conceal it (J1) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 5.15 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 4.41 | < 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 4.38 | < 0.001 | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 2.97 | 0.003 |

| COVID-19 was created in a laboratory as a biochemical weapon (J2) | – 0.03 | 0.01 | – 4.09 | < 0.001 | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 2.91 | 0.004 | ||||||||

| COVID-19 is the result of 5G technology antenna (J3) | – 0.03 | 0.01 | – 3.19 | 0.001 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 6.71 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| COVID-19 appeared accidentally from human contact with animals (J4) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.42 | 0.016 | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 3.75 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| COVID-19 has much lower mortality rate but there is terror-inducing propaganda (J5) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.03 | 0.042 | ||||||||||||

| COVID-19 is a creation of the world’s powerful leaders to create a global economic crisis (J6) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.43 | 0.015 | – 0.02 | 0.01 | – 2.15 | 0.031 | ||||||||

| COVID-19 is a sign of divine power to destroy our planet (J7) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 4.43 | < 0.001 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 6.12 | < 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.99 | 0.003 | ||||

| Occupation (A10) | ||||||||||||||||

| Doctor | – 0.04 | 0.01 | – 3.08 | 0.002 | ||||||||||||

| Nurse | 0.07 | 0.02 | 2.89 | 0.004 | – 0.05 | 0.02 | – 2.06 | 0.040 | ||||||||

| Other Hospital staff | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2.13 | 0.033 | ||||||||||||

| Other healthcare professional | ||||||||||||||||

| Administrative staff | ||||||||||||||||

The predictors are shown in the left column

Fig. 2.

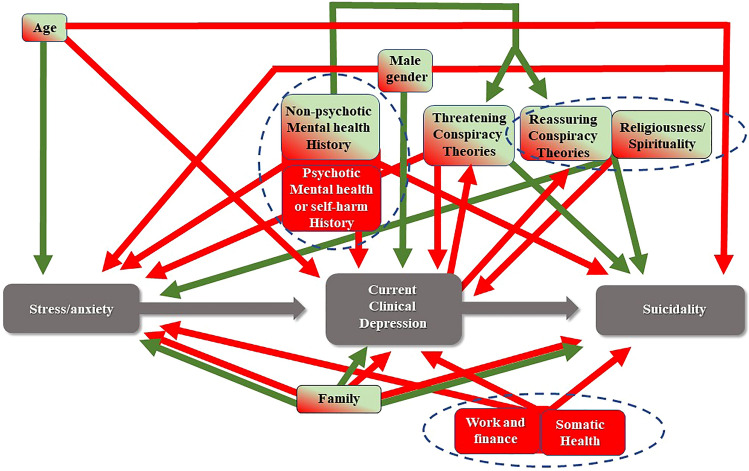

The model which was previously developed in the general population and was proven valid also in the population of health professionals. It includes multiple vulnerabilities representing the mechanism through which the COVID-19 outbreak in combination a great number of factors could lead to clinical depression through stress, and eventually to suicidality. A number of variables act as risk factors (red) or as protective factors (green), while some of them change direction of action depending on the phase (green/red). Three core clusters emerge (delineated with the doted lines)

If we consider a more or less linear continuum from fear to anxiety to depressive emotions to clinical depression and eventually to suicidality, the model which can be derived suggests there is a core of variables (Fig. 2, webfigure 1) that exert a stable either adverse or protective effect throughout the course of the development of the mental state.

Factorial ANOVA with the scores of STAI-S, CES-D and RASS as continuous variables and sex and being a doctor or a nurse as grouping variables was always significant for sex (p < 0.0001). For doctors only the interaction with sex is significant (Wilks = 0.996, F = 4.86, df = 10, error df = 25,562, p < 0.0001), with ‘non-binary genders’ having higher psychopathology. For nurses it was significant both independently (Wilks = 0.999, F = 7.768, df = 10, error df = 25,562, p = 0.009) as well as in interaction with sex (Wilks = 0.998, F = 2.618, df = 10, error df = 25,562, p = 0.004). Overall nurses had lower psychopathological scores than the rest. The Scheffe post-hoc tests (at p < 0.05) revealed that most groups defined by sex and occupation differed from each other in a complex and difficult-to-explain matrix.

Conspiracy theories manifest a complex behavior with some of them exerting a protective effect at certain phases (Fig. 2), but their overall impact was lower in comparison to the general population. The mean scores of responses to questions pertaining to different conspiracy beliefs by history of any mental disorder and current clinical depression are shown in Table 5 and webtable 24. Factorial ANOVA suggested that history of any mental disorder and current clinical depression as well as their interaction were significant factors concerning the belief in conspiracy theories (Table 5). The results of post-hoc tests are shown in webtable 25. They suggest that persons with a history of mental disorder have lower overall tendency in believing in both the threatening and the reassuring conspiracy theories. Not believing in any conspiracy theory had a different composition with history of having any mental disorder being the determining factor leading to lower adaption of conspiracy theories and with depression acting at a second level and further decreasing this tendency. These findings were consistent across disorders and conspiracy theories.

Table 5.

Means of responses (from –2 to + 2) to all conspiracy theories by current clinical depression and history of any mental disorder and ANOVA results

| Current clinical depression | History of any mental dis | Reassuring conspiracy theories | Threatening conspiracy theories | No believing in conspiracy theories | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J1 | J5 | J7 | J2 | J3 | J6 | J4 | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Means of response scores by clinical depression and history | |||||||||||||||

| No | Yes | 0.61 | 1.02 | 1.20 | 1.29 | 0.41 | 0.89 | 0.97 | 1.15 | 0.39 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 1.19 | 2.01 | 1.21 |

| No | No | 0.81 | 1.10 | 1.32 | 1.25 | 0.57 | 0.99 | 1.28 | 1.24 | 0.56 | 0.95 | 1.20 | 1.24 | 1.69 | 1.19 |

| Yes | Yes | 0.94 | 1.23 | 1.28 | 1.28 | 0.58 | 1.05 | 1.31 | 1.29 | 0.63 | 1.08 | 1.22 | 1.31 | 1.87 | 1.23 |

| Yes | No | 1.06 | 1.21 | 1.41 | 1.25 | 0.95 | 1.28 | 1.43 | 1.28 | 0.89 | 1.16 | 1.44 | 1.30 | 1.73 | 1.21 |

| All Grps | 0.80 | 1.11 | 1.31 | 1.26 | 0.57 | 1.01 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 0.55 | 0.96 | 1.17 | 1.25 | 1.76 | 1.21 | |

| ANOVA results | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilks | F | Effect df | Error df | p | |||||||||||

| Clinical depression | 0.986 | 26.54 | 7 | 12,780 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| History of any mental disorder | 0.988 | 23.06 | 7 | 12,780 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Clinical depression* history of any mental disorder | 0.997 | 5.51 | 7 | 12,780 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||

Discussion

This large international study in a convenient sample of 12,792 health professionals from 40 countries detected clinical depression in 13.31% (unweighted average) with men and ‘non-binary genders’ doctors having the lowest rates (7.89% and 5.88% respectively) and ‘non-binary gender’ nurses and administrative staff having the highest (37.50%). Distress was present in 15.19%, with the highest rates being for the ‘non-binary gender’ (> 30%) and the lowest for female administrative staff (12.28%). A significant percentage reported a deterioration in mental state, family dynamics and everyday lifestyle. Persons with a history of mental disorders had higher rates of current clinical depression (24.64%) while persons without any such history had the lowest rate or current clinical depression (9.62%). The highest rate was for the history of Bipolar disorder (40.66%; RR = 4.23). In those with a chronic somatic condition, the rate of clinical depression was 15.35% vs. 12.56% in those without (RR = 1.22). Believing in conspiracy theories was significant with at least one-third of cases accepting at least to a moderate degree a non-bizarre conspiracy.

The model developed suggested that a significant number of variables acted either as risk or as protective factors, explaining 19.1% of the development of distress or clinical depression, but their individual contribution was very small. Conspiracy theories manifested a complex behavior with some of them exerting a protective effect at certain phases. Current clinical depression acted as a risk factor and past history acted as a protective for the development of such beliefs.

The overall levels of clinical depression were lower than the rates reported in the literature, probably because of the stringent criteria of the algorithm in the current study. The large heterogeneity among countries probably reflects different phases of the pandemic in each country during the data collection. Rates of depression and mental health deterioration, in general, are probably higher in those that actually suffered from COVID-19 [29]. Other studies reported that half or more of health care professionals might suffer from depression. [7, 24, 32, 48, 76, 81, 82, 103, 117],Mira et al. 2020; [111, 112, 118]. Our results are identical to two reports [26, 52]. Meta-analyses suggested that depression rates range from 27% to 36% [45, 102, 109, 116] which is two to three times higher in comparison to our findings. In comparison, it has been reported that more than two-thirds of the general population experienced at least severe distress [18, 31, 50, 62, 80, 83, 110], and high levels of suicidality [19]. Furthermore, our findings are in accord with a recently published meta-analysis that reported much lower depression rates in the general population [21].

An important observation is that while the rate of clinical depression was much higher in persons with a history of a mental disorder the proportion of depressed persons without such a history is much higher than expected, taking into consideration that the annual incidence of depression is 0.3% [66]. This might mean that the pandemic posed a RR = 30 on the population of health professionals to develop clinical depression.

The multivariable analysis of the data allowed the current paper to confirm a staged model previously proposed concerning the effect of the pandemic on mental health (Fig. 2). This model had been developed concerning the general population and it seems that in principle it is valid for health professionals, although with some differences, especially concerning the attenuating effect of conspiracy theories and religiousness/spirituality.

According to it, with the onset of the pandemic, its psychological impact and the development of severe anxiety and distress were determined by several sociodemographic and interpersonal variables including age, fears specific to the pandemic, the quality of relationships within the family, keeping a basic daily routine, change in the economic situation, history of any mental disorder and being afraid that him/herself or a family member will get COVID-19 and die. Similar findings concerning the effects of these factors have been reported in the literature [7, 17, 32, 35, 36, 46, 56, 57, 65, 67, 70, 80, 95, 98, 107, 111–113], Garre-Olmo et al. 2021; [89], but until now their detailed contribution had not been identified and no comprehensive model had been developed. On the other hand, several factors not assessed by the current study, including the level of training, whether the person worked in the frontline against COVID or in an ICU, etc. [8, 54, 67, 111, 112], Mira et al. 2020; [7, 20, 24, 48, 51, 52, 71, 82, 95, 101, 103, 107] were reported as contributing in the development of clinical depression. The current paper suggests that from all health occupations, nurses might be at a higher risk to develop severe stress and clinical depression, and this is in accord with the literature [33, 48, 51, 58, 118]. Previous reports on the role of temperament are in accord with this [74]

At the pandemic onset, we might not have imagined the important role and the impact of conspiracy theories, which are largely social media driven. They are currently widely accepted as being important since the literature strongly supports their relationship with anxiety and depression [22, 28]. According to the results of the current study, approximately one-third of responders accepted at least to a moderate degree a non-bizarre conspiracy theory, and this was true both for ‘threatening’ as well as for ‘reassuring’ theories. The acceptance of inflated death rates was 44.24% while that of the 5G antenna theory was 20.81%. Doctors had the lowest rates, but impressively, 37.6% of doctors and 50.86% of nurses reported they were believing in the deliberate inflation of death rates by governments, and 14.75% and 27.22% respectively were accepting the 5G theory. Interestingly, believing in conspiracy theories pertaining to COVID-19 was lower in comparison to the general population and played an attenuated role in the development of anxiety and depression, however, these beliefs seem to be an important factor even among doctors. The high rates of believing in conspiracy theories are in accord with findings from various countries [1, 64, 91, 108] and are a worrying manifestation. Conspiracy beliefs – especially those regarding science, medicine, and health-related topics – are widespread [78], are widely distributed in social media [1, 11] and they challenge the capacity of the average person to distill and assess the content [30, 34]. They exert a well-documented adverse effect on health behaviors, especially vaccination [2, 3, 14–16, 43, 49, 59, 63, 72, 88, 91, 93, 99, 105]. There seems to be some relationship between believing in bizarre conspiracy theories and psychotic tendencies or a history of psychotic disorders [60].

As was found in the general population, current clinical depression and past history of mental disorders are both critical factors related to believing in conspiracy theories. Our results could mean that the critical factor which increases belief is the presence of current clinical depression, while the past history acts at a second level. As correlation does not imply causation, conspiracy theories could be either the cause of clinical depression, a copying mechanism against clinical depression, or a marker of maladaptive psychological patterns of cognitive appraisal. After taking into consideration the complete model, and especially the relationship to past mental health history, the authors propose that the beliefs in conspiracy theories are a copying mechanism against stress. The finding of the relationship between current clinical depression and believing in conspiracies is in accord with the literature [28, 44, 106], One explanation could be found in the theory concerning ‘Depressive Realism’ [5, 6], Alloy et al. 1981; [12, 68, 77] which suggests that depressive persons are more able than others to realistically interpret the world, however, this higher ability leads to pessimism.

At the most extreme end, when the emergence of suicidal thinking is possible, the family environment and family responsibilities and care act either as risk or protective factors, depending on their quality, while religiosity/spirituality and all beliefs in conspiracy theories act as protective factors, except for one which includes religious content. These results are in accord with the reports in the literature [9, 56, 57, 61, 65, 79, 113].

A difficult-to-answer question is how many of the cases detected by questionnaires and sophisticated algorithms correspond to real major clinical depression. The underlying neurobiology is opaque and maybe much diagnosed clinical depression might simply be an extreme form of a normal adjustment reaction [53]. However, there is no better way to psychometrically achieve higher validity and the algorithm we utilized is the best available method. The impressive increase in new cases of clinical depression (9.62% of persons without any history of mental disorders developed depression) which was found in our sample is in accord with the literature [87]. However, a large part of clinical depressions emerged from a previous mental health history. Of the 13.15% with current clinical depression, 7.35% were new cases while 5.80% had previous history. This suggests that almost beyond doubt true clinical depression increased by 30% (in the extreme scenario that none of cases without previous history was a case of true clinical depression. This extremely positive scenario also suggests that maybe relapses expected to occur in the next several years occurred earlier.

Concerning those without a previous history of mental disorder, it is expected that much of the adverse effects on mental health will rapidly attenuate with the end of the pandemic [27] but enduring effects will impact some vulnerable populations. So far studies investigating the long-term outcome and the long-term impact of the pandemic on mental health display equivocal findings [13, 114]. Especially sociability and the sense of belonging could be important factors determining mental health and health-related behaviors [15], and these factors seem to correspond to specific vulnerabilities seen especially in western cultures.

Conclusion

The current paper reports high rates of clinical depression, distress, and suicidal thoughts among the population of health workers during the pandemic, with a high prevalence of beliefs in conspiracy theories. For the development of clinical depression, general health status, previous mental health history, self-harm and suicidal attempts, family responsibility, economic change, and age acted as risk factors while keeping a daily routine, religiousness/spirituality, and belief in conspiracy theories were acting mostly as protective factors. These findings, although they should be closely monitored longitudinally, support previous suggestions by other authors concerning the need for a proactive intervention to protect the mental health of the general population but more specifically of vulnerable groups [38, 94]

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the current paper include the large number of persons who filled out the questionnaire and the large bulk of information obtained, as well as the detailed way of post-stratification of the study sample.

The major limitation was that the data were obtained anonymously online through the self-selection of the responders. Additionally, the assessment included only the cross-sectional application of self-report scales, although the advanced algorithm used for the diagnosis of clinical depression corrected the problem to a certain degree. However, what is included under the umbrella of ‘clinical depression’ in the stressful times of the pandemic remains a matter of debate. Also, the lack of baseline data concerning the mental health of a similar study sample before the pandemic is also a problem.

Finally, a limitation would be that data from different countries were pooled together and with a rather large difference in numbers among countries. So the interpretation of findings should bear in mind the possible bias induced by different cultural backgrounds. However, one should have also in mind that backgrounds are not so different as one might think since the online survey of a specific professional population poses requirements that lead to similarities rather than differences among the populations from different countries. Each of these countries was also undergoing a different phase of the pandemic at each time point and phases were also different across individuals. This means that the results should be interpreted.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the paper. KNF and DS conceived and designed the study. The other authors participated formulating the final protocol, designing and supervising the data collection and creating the final dataset. KNF and DS did the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors participated in interpreting the data and developing further stages and the final version of the paper.

Funding

None.

Data availability statement

Raw data are available upon request to the principal investigator.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None pertaining to the current paper.

Contributor Information

Konstantinos N. Fountoulakis, Email: Kostasfountoulakis@gmail.com.

Grigorios N. Karakatsoulis, Email: gregkarakatsoulis@gmail.com.

Seri Abraham, Email: seri.abraham@nhs.net.

Kristina Adorjan, Email: Kristina.Adorjan@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Helal Uddin Ahmed, Email: soton73@gmail.com.

Renato D. Alarcón, Email: renato.alarcon@upch.pe, Email: alarcon.renato@mayo.edu

Kiyomi Arai, Email: k_arai@shinshu-u.ac.jp.

Sani Salihu Auwal, Email: auwal01@yahoo.com.

Julio Bobes, Email: bobes@uniovi.es.

Teresa Bobes-Bascaran, Email: bobesmaria@uniovi.es.

Julie Bourgin-Duchesnay, Email: julie.bourgin@gmail.com.

Cristina Ana Bredicean, Email: brediceancristina@gmail.com.

Laurynas Bukelskis, Email: bukelskis@gmail.com.

Akaki Burkadze, Email: dr.burkadze@gmail.com.

Indira Indiana Cabrera Abud, Email: indira_ica@hotmail.com.

Ruby Castilla-Puentes, Email: rcastil4@its.jnj.com.

Marcelo Cetkovich, Email: mcetkovich@ineco.org.ar.

Hector Colon-Rivera, Email: hectorcolonriveramd@gmail.com.

Ricardo Corral, Email: rcorral33@gmail.com.

Carla Cortez-Vergara, Email: carla.cortez.v@upch.pe.

Piirika Crepin, Email: piirika.crepin@gmail.com.

Domenico de Berardis, Email: domenico.deberardis@aslteramo.it.

Sergio Zamora Delgado, Email: szamora@calvomackenna.cl.

David de Lucena, Email: alienista@ufc.br, Email: dvdlucena@gmail.com.

Avinash de Sousa, Email: avinashdes888@gmail.com.

Ramona di Stefano, Email: ramonadist@gmail.com.

Seetal Dodd, Email: seetaldodd@gmail.com.

Livia Priyanka Elek, Email: elek.livia.priyanka@gmail.com.

Anna Elissa, Email: annaelissa.md@gmail.com.

Berta Erdelyi-Hamza, Email: hamzaberta@gmail.com.

Gamze Erzin, Email: gamze.erzin@gmail.com.

Martin J. Etchevers, Email: martinjetchevers@gmail.com

Peter Falkai, Email: Peter.Falkai@med.uni-muenchen.de.

Adriana Farcas, Email: 6amf@queensu.ca.

Ilya Fedotov, Email: ilyafdtv11@gmail.com.

Viktoriia Filatova, Email: filatovaviktoria@mail.ru.

Nikolaos K. Fountoulakis, Email: nikolasfountoulakis@gmail.com

Iryna Frankova, Email: iryna.frankova@gmail.com.

Francesco Franza, Email: franza.francesco@virgilio.it.

Pedro Frias, Email: friaspn@gmail.com.

Tatiana Galako, Email: tatiana-galako@yandex.ru.

Cristian J. Garay, Email: cristiangaray@psi.uba.ar

Leticia Garcia-Álvarez, Email: lettti@gmail.com.

Paz García-Portilla, Email: albert@uniovi.es.

Xenia Gonda, Email: kendermagos@yahoo.com.

Tomasz M. Gondek, Email: tomaszmgondek@gmail.com

Daniela Morera González, Email: danielamorera@gmail.com.

Hilary Gould, Email: hgould@health.ucsd.edu.

Paolo Grandinetti, Email: grandinetti.paolo@gmail.com.

Arturo Grau, Email: doctorgrau@yahoo.com.

Violeta Groudeva, Email: violetagroudeva@gmail.com.

Michal Hagin, Email: michal.hagin@gmail.com.

Takayuki Harada, Email: tkharada77@gmail.com.

Tasdik M. Hasan, Email: tasdikhdip@yahoo.com

Nurul Azreen Hashim, Email: azreen@uitm.edu.my.

Jan Hilbig, Email: hilbig.jan@gmail.com.

Sahadat Hossain, Email: sahadat.hossain@juniv.edu.

Rossitza Iakimova, Email: rosica.iakimova@abv.bg.

Mona Ibrahim, Email: monaawaad99@gmail.com.

Felicia Iftene, Email: iftenef@providencecare.ca.

Yulia Ignatenko, Email: hvala_korolevna@rambler.ru.

Matias Irarrazaval, Email: matias.irarrazaval@minsal.cl.

Zaliha Ismail, Email: zaliha78@uitm.edu.my.

Jamila Ismayilova, Email: ismayilova.d@gmail.com.

Asaf Jacobs, Email: asafjacobs@gmail.com.

Miro Jakovljević, Email: jakovljevic.miro@yahoo.com.

Nenad Jakšić, Email: nenad_jaksic@yahoo.com.

Afzal Javed, Email: afzalj@gmail.com.

Helin Yilmaz Kafali, Email: helinyilmaz136@gmail.com.

Sagar Karia, Email: kariabhai117@gmail.com.

Olga Kazakova, Email: olga.kazakova.md@gmail.com.

Doaa Khalifa, Email: doaakhalifa72@gmail.com.

Olena Khaustova, Email: 7974247@gmail.com.

Steve Koh, Email: shkoh@ucsd.edu.

Svetlana Kopishinskaia, Email: kopishinskaya@gmail.com.

Korneliia Kosenko, Email: sun2003@ukr.net.

Sotirios A. Koupidis, Email: sotirioskoupidis@yahoo.gr

Illes Kovacs, Email: kovilles@gmail.com.

Barbara Kulig, Email: kulig.barbara@hotmail.com.

Alisha Lalljee, Email: alishalalljee@gmail.com.

Justine Liewig, Email: j.liewig@gmail.com.

Abdul Majid, Email: maajid72@gmail.com.

Evgeniia Malashonkova, Email: e.malashonkova@gh-nord-essonne.fr.

Khamelia Malik, Email: khameliapsi@gmail.com.

Najma Iqbal Malik, Email: Najma.iqbal@uos.edu.pk, Email: najmamalik@gmail.com.

Gulay Mammadzada, Email: gulay.mammadzada@gmail.com.

Bilvesh Mandalia, Email: bilveshmandalia@gmail.com.

Donatella Marazziti, Email: dmarazzi@psico.med.unipi.it.

Darko Marčinko, Email: predstojnik.psi@kbc-zagreb.hr.

Stephanie Martinez, Email: stm032@health.ucsd.edu.

Eimantas Matiekus, Email: eimantasmatiekus@yahoo.com.

Gabriela Mejia, Email: ggmejia@health.ucsd.edu.

Roha Saeed Memon, Email: memon.roha@gmail.com.

Xarah Elenne Meza Martínez, Email: xarahmeza22@gmail.com.

Dalia Mickevičiūtė, Email: dalia.mickeviciute@gmail.com.

Roumen Milev, Email: roumen.milev@queensu.ca.

Muftau Mohammed, Email: miftahmuhammad101@gmail.com.

Alejandro Molina-López, Email: doctor.alex.psiquiatra@gmail.com.

Petr Morozov, Email: prof.morozov@gmail.com.

Nuru Suleiman Muhammad, Email: nurusulemuhammad@gmail.com.

Filip Mustač, Email: filip.mustac@gmail.com.

Mika S. Naor, Email: Mikanaor@mail.tau.ac.il

Amira Nassieb, Email: amiraelbatrawy@gmail.com.

Alvydas Navickas, Email: alvydas.navickas@mf.vu.lt.

Tarek Okasha, Email: tarek.okasha@gmail.com.

Milena Pandova, Email: milena.pandova@gmail.com.

Anca-Livia Panfil, Email: anca.livia.panfil@gmail.com.

Liliya Panteleeva, Email: p.lilya12@gmail.com.

Ion Papava, Email: papava.ion@umft.ro.

Mikaella E. Patsali, Email: mikaellapatsali@gmail.com

Alexey Pavlichenko, Email: apavlichenko76@gmail.com.

Bojana Pejuskovic, Email: bpejuskovic@hotmail.com.

Mariana Pinto da Costa, Email: mariana.pintodacosta@gmail.com.

Mikhail Popkov, Email: mihailpopkovanat@gmail.com.

Dina Popovic, Email: popovic.dina@gmail.com.

Nor Jannah Nasution Raduan, Email: norjannah@uitm.edu.my.

Francisca Vargas Ramírez, Email: fvargas.ra@gmail.com.

Elmars Rancans, Email: erancans@latnet.lv.

Salmi Razali, Email: drsalmi@uitm.edu.my.

Federico Rebok, Email: federicorebok@gmail.com.

Anna Rewekant, Email: reweana@gmail.com.

Elena Ninoska Reyes Flores, Email: elena.reyes@unah.edu.hn.

María Teresa Rivera-Encinas, Email: mriverae@usmp.pe.

Pilar A. Saiz, Email: frank@uniovi.es

Manuel Sánchez de Carmona, Email: msanchezdecarmona@mac.com.

David Saucedo Martínez, Email: davidsaucedomartinez1@gmail.com.

Jo Anne Saw, Email: annejosaw@uitm.edu.my.

Görkem Saygili, Email: gsaygili@gmail.com.

Patricia Schneidereit, Email: p.schneidereit@klinikum-weissenhof.de.

Bhumika Shah, Email: bhumikarshah47@gmail.com.

Tomohiro Shirasaka, Email: shirasaka.t@gmail.com.

Ketevan Silagadze, Email: ketevani26@gmail.com.

Satti Sitanggang, Email: sattiradja_96@yahoo.co.id.

Oleg Skugarevsky, Email: skugarevsky@gmail.com.

Anna Spikina, Email: a-spikina@yandex.ru.

Sridevi Sira Mahalingappa, Email: sridevi.siramahalingappa@nhs.net.

Maria Stoyanova, Email: mb_milenkova@yahoo.com.

Anna Szczegielniak, Email: anna.szczegielniak@gmail.com.

Simona Claudia Tamasan, Email: simona_tamasan@yahoo.com.

Giuseppe Tavormina, Email: dr.tavormina.g@libero.it.

Maurilio Giuseppe Maria Tavormina, Email: mtavormina@virgilio.it.

Pavlos N. Theodorakis, Email: theodorakisp@who.int

Mauricio Tohen, Email: MTohen@salud.unm.edu.

Eva-Maria Tsapakis, Email: emtsapakis@doctors.org.uk.

Dina Tukhvatullina, Email: d.tukhvatullina@smd20.qmul.ac.uk.

Irfan Ullah, Email: Irfanullahecp2@gmail.com.

Ratnaraj Vaidya, Email: r.vaidya@newcastle.ac.uk.

Johann M. Vega-Dienstmaier, Email: johann.vega.d@upch.pe, Email: johannvega@yahoo.com

Jelena Vrublevska, Email: vrublevskaja@inbox.lv.

Olivera Vukovic, Email: olivukovic@gmail.com.

Olga Vysotska, Email: uafmed@gmail.com.

Natalia Widiasih, Email: widiasih_1973@yahoo.com.

Anna Yashikhina, Email: akvaraul@mail.ru.

Panagiotis E. Prezerakos, Email: prezerpot@gmail.com

Michael Berk, Email: michael.berk@deakin.edu.au.

Sarah Levaj, Email: sarahbjedov@gmail.com.

Daria Smirnova, Email: daria.smirnova.md.phd@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Ahmed W, Vidal-Alaball J, Downing J, Lopez Segui F. COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: social network analysis of Twitter Data. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(5):e19458. doi: 10.2196/19458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allington D, Duffy B, Wessely S, Dhavan N, Rubin J. Health-protective behaviour, social media usage and conspiracy belief during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Psychol Med. 2021;51(10):1763–1769. doi: 10.1017/S003329172000224X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allington D, McAndrew S, Moxham-Hall V, Duffy B. Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2021 doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Viscusi D. Induced mood and the illusion of control. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1981;41(6):1129. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.41.6.1129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: sadder but wiser? J Exp Psychol Gen. 1979;108(4):441–485. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.108.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Cognitive processes in depression. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press; 1988. Depressive realism: Four theoretical perspectives; pp. 223–265. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amin F, Sharif S, Saeed R, Durrani N, Jilani D. COVID-19 pandemic- knowledge, perception, anxiety and depression among frontline doctors of Pakistan. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):459. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02864-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonijevic J, Binic I, Zikic O, Manojlovic S, Tosic-Golubovic S, Popovic N. Mental health of medical personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav. 2020;10(12):e01881. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arslan G, Yildirim M. Meaning-based coping and spirituality during the COVID-19 pandemic: mediating effects on subjective well-being. Front Psychol. 2021;12:646572. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asmundson GJG, Taylor S. Garbage in, garbage out: the tenuous state of research on PTSD in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and infodemic. J Anxiety Disord. 2021;78:102368. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banerjee D, Meena KS. COVID-19 as an "Infodemic" in public health: critical role of the social media. Front Public Health. 2021;9:610623. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.610623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Beck AT, Brown G, Steer RA, Eidelson JI, Riskind JH. Differentiating anxiety and depression: a test of the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis. J Abnorm Psychol. 1987;96(3):179–183. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bendau A, Plag J, Kunas S, Wyka S, Strohle A, Petzold MB. Longitudinal changes in anxiety and psychological distress, and associated risk and protective factors during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Brain Behav. 2021;11(2):e01964. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertin P, Nera K, Delouvee S. Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloroquine: a conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Front Psychol. 2020;11:565128. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biddlestone M, Green R, Douglas KM. Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Br J Soc Psychol. 2020;59(3):663–673. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bogart LM, Wagner G, Galvan FH, Banks D. Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among African American men with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(5):648–655. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c57dbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruffaerts R, Voorspoels W, Jansen L, Kessler RC, Mortier P, Vilagut G, De Vocht J, Alonso J. Suicidality among healthcare professionals during the first COVID-19 wave. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busch IM, Moretti F, Mazzi M, Wu AW, Rimondini M. What we have learned from two decades of epidemics and pandemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychological burden of frontline healthcare workers. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90(3):178–190. doi: 10.1159/000513733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caballero-Dominguez CC, Jimenez-Villamizar MP, Campo-Arias A (2020) Suicide risk during the lockdown due to coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Colombia. Death Stud 10.1080/07481187.2020.1784312 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Celmece N, Menekay M. The effect of stress, anxiety and burnout levels of healthcare professionals caring for COVID-19 patients on their quality of life. Front Psychol. 2020;11:597624. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.597624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cenat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Noorishad PG, Mukunzi JN, McIntee SE, Dalexis RD, Goulet MA, Labelle PR. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113599. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen X, Zhang SX, Jahanshahi AA, Alvarez-Risco A, Dai H, Li J, Ibarra VG. Belief in a COVID-19 conspiracy theory as a predictor of mental health and well-being of health care workers in Ecuador: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(3):e20737. doi: 10.2196/20737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Claponea RM, Pop LM, Iorga M, Iurcov R. Symptoms of burnout syndrome among physicians during the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic-a systematic literature review. Healthcare (Basel) 2022 doi: 10.3390/healthcare10060979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conti C, Fontanesi L, Lanzara R, Rosa I, Doyle RL, Porcelli P. Burnout status of italian healthcare workers during the first COVID-19 pandemic peak period. Healthcare (Basel) 2021 doi: 10.3390/healthcare9050510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courtet P, Olie E. Suicide in the COVID-19 pandemic: what we learnt and great expectations. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;50:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.da Silva FCT, Neto MLR. Psychological effects caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in health professionals: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;104:110062. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daly M, Robinson E. Anxiety reported by US adults in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: population-based evidence from two nationally representative samples. J Affect Disord. 2021;286:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Coninck D, Frissen T, Matthijs K, d'Haenens L, Lits G, Champagne-Poirier O, Carignan ME, David MD, Pignard-Cheynel N, Salerno S, Genereux M. Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Front Psychol. 2021;12:646394. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, Silver Z, Wong CY, Chang O, Huang E, Zuo QK. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021;1486(1):90–111. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desta TT, Mulugeta T. Living with COVID-19-triggered pseudoscience and conspiracies. Int J Public Health. 2020;65(6):713–714. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01412-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dominguez-Salas S, Gomez-Salgado J, Andres-Villas M, Diaz-Milanes D, Romero-Martin M, Ruiz-Frutos C. Psycho-emotional approach to the psychological distress related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: a cross-sectional observational study. Healthcare (Basel) 2020 doi: 10.3390/healthcare8030190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong ZQ, Ma J, Hao YN, Shen XL, Liu F, Gao Y, Zhang L. The social psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical staff in China: a cross-sectional study. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63(1):e65. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donkers MA, Gilissen V, Candel M, van Dijk NM, Kling H, Heijnen-Panis R, Pragt E, van der Horst I, Pronk SA, van Mook W. Moral distress and ethical climate in intensive care medicine during COVID-19: a nationwide study. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12910-021-00641-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duplaga M. The determinants of conspiracy beliefs related to the COVID-19 pandemic in a nationally representative sample of internet users. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17217818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elbogen EB, Lanier M, Blakey SM, Wagner HR, Tsai J. Suicidal ideation and thoughts of self-harm during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of COVID-19-related stress, social isolation, and financial strain. Depress Anxiety. 2021 doi: 10.1002/da.23162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elhai JD, Yang H, McKay D, Asmundson GJG, Montag C. Modeling anxiety and fear of COVID-19 using machine learning in a sample of Chinese adults: associations with psychopathology, sociodemographic, and exposure variables. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;34(2):130–144. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2021.1878158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fancourt D, Steptoe A, Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fiorillo A, Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63(1):e32. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fountoulakis K, Iacovides A, Kleanthous S, Samolis S, Kaprinis SG, Sitzoglou K, St Kaprinis G, Bech P. Reliability, validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2001;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fountoulakis KN, Apostolidou MK, Atsiova MB, Filippidou AK, Florou AK, Gousiou DS, Katsara AR, Mantzari SN, Padouva-Markoulaki M, Papatriantafyllou EI, Sacharidi PI, Tonia AI, Tsagalidou EG, Zymara VP, Prezerakos PE, Koupidis SA, Fountoulakis NK, Chrousos GP. Self-reported changes in anxiety, depression and suicidality during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fountoulakis KN, Karakatsoulis G, Abraham S, Adorjan K, Ahmed HU, Alarcón RD, Arai K, Auwal SS, Berk M, Bjedov S, Bobes J, Bobes-Bascaran T, Bourgin-Duchesnay J, Bredicean CA, Bukelskis L, Burkadze A, Abud IIC, Castilla-Puentes R, Cetkovich M, Colon-Rivera H, Corral R, Cortez-Vergara C, Crepin P, De Berardis D, Zamora Delgado S, De Lucena D, De Sousa A, Stefano RD, Dodd S, Elek LP, Elissa A, Erdelyi-Hamza B, Erzin G, Etchevers MJ, Falkai P, Farcas A, Fedotov I, Filatova V, Fountoulakis NK, Frankova I, Franza F, Frias P, Galako T, Garay CJ, Garcia-Álvarez L, García-Portilla MP, Gonda X, Gondek TM, González DM, Gould H, Grandinetti P, Grau A, Groudeva V, Hagin M, Harada T, Hasan TM, Hashim NA, Hilbig J, Hossain S, Iakimova R, Ibrahim M, Iftene F, Ignatenko Y, Irarrazaval M, Ismail Z, Ismayilova J, Jakobs A, Jakovljević M, Jakšić N, Javed A, Kafali HY, Karia S, Kazakova O, Khalifa D, Khaustova O, Koh S, Kopishinskaia S, Kosenko K, Koupidis SA, Kovacs I, Kulig B, Lalljee A, Liewig J, Majid A, Malashonkova E, Malik K, Malik NI, Mammadzada G, Mandalia B, Marazziti D, Marčinko D, Martinez S, Matiekus E, Mejia G, Memon RS, Martínez XEM, Mickevičiūtė D, Milev R, Mohammed M, Molina-López A, Morozov P, Muhammad NS, Mustač F, Naor MS, Nassieb A, Navickas A, Okasha T, Pandova M, Panfil A-L, Panteleeva L, Papava I, Patsali ME, Pavlichenko A, Pejuskovic B, Da Costa MP, Popkov M, Popovic D, Raduan NJN, Ramírez FV, Rancans E, Razali S, Rebok F, Rewekant A, Flores ENR, Rivera-Encinas MT, Saiz P, de Carmona MS, Martínez DS, Saw JA, Saygili G, Schneidereit P, Shah B, Shirasaka T, Silagadze K, Sitanggang S, Skugarevsky O, Spikina A, Mahalingappa SS, Stoyanova M, Szczegielniak A, Tamasan SC, Tavormina G, Tavormina MGM, Theodorakis PN, Tohen M, Tsapakis EM, Tukhvatullina D, Ullah I, Vaidya R, Vega-Dienstmaier JM, Vrublevska J, Vukovic O, Vysotska O, Widiasih N, Yashikhina A, Prezerakos PE, Smirnova D. Results of the COVID-19 MEntal health inTernational for the General population (COMET-G) study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fountoulakis KN, Pantoula E, Siamouli M, Moutou K, Gonda X, Rihmer Z, Iacovides A, Akiskal H. Development of the Risk Assessment Suicidality Scale (RASS): a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2012;138(3):449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Freeman D, Loe BS, Chadwick A, Vaccari C, Waite F, Rosebrock L, Jenner L, Petit A, Lewandowsky S, Vanderslott S, Innocenti S, Larkin M, Giubilini A, Yu LM, McShane H, Pollard AJ, Lambe S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: the Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol Med. 2020 doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freyler A, Simor P, Szemerszky R, Szabolcs Z, Koteles F. Modern health worries in patients with affective disorders. A pilot study. Ideggyogy Sz. 2019;72(9–10):337–341. doi: 10.18071/isz.72.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galli F, Pozzi G, Ruggiero F, Mameli F, Cavicchioli M, Barbieri S, Canevini MP, Priori A, Pravettoni G, Sani G, Ferrucci R. A systematic review and provisional metanalysis on psychopathologic burden on health care workers of coronavirus outbreaks. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:568664. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.568664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gambin M, Sekowski M, Wozniak-Prus M, Wnuk A, Oleksy T, Cudo A, Hansen K, Huflejt-Lukasik M, Kubicka K, Lys AE, Gorgol J, Holas P, Kmita G, Lojek E, Maison D. Generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms in various age groups during the COVID-19 lockdown in Poland. Specific predictors and differences in symptoms severity. Compr Psychiatry. 2021;105:152222. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Marti-Lluch R, Zacarias-Pons L, Alves-Cabratosa L, Serrano-Sarbosa D, Vilalta-Franch J, Ramos R, Girona Health Region Study G Changes in lifestyle resulting from confinement due to COVID-19 and depressive symptomatology: a cross-sectional a population-based study. Compr Psychiatry. 2021;104:152214. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giusti EM, Pedroli E, D'Aniello GE, Stramba Badiale C, Pietrabissa G, Manna C, Stramba Badiale M, Riva G, Castelnuovo G, Molinari E. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1684. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gu F, Wu Y, Hu X, Guo J, Yang X, Zhao X. The role of conspiracy theories in the spread of COVID-19 across the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gualano MR, Lo Moro G, Voglino G, Bert F, Siliquini R. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hacimusalar Y, Kahve AC, Yasar AB, Aydin MS. Anxiety and hopelessness levels in COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative study of healthcare professionals and other community sample in Turkey. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;129:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han S, Choi S, Cho SH, Lee J, Yun JY. Associations between the working experiences at frontline of COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of Korean public health doctors. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):298. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03291-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He L, Wei D, Yang F, Zhang J, Cheng W, Feng J, Yang W, Zhuang K, Chen Q, Ren Z, Li Y, Wang X, Mao Y, Chen Z, Liao M, Cui H, Li C, He Q, Lei X, Feng T, Chen H, Xie P, Rolls ET, Su L, Li L, Qiu J. Functional connectome prediction of anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178(6):530–540. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20070979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hesselink G, Straten L, Gallee L, Brants A, Holkenborg J, Barten DG, Schoon Y. Holding the frontline: a cross-sectional survey of emergency department staff well-being and psychological distress in the course of the COVID-19 outbreak. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):525. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06555-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hill JE, Harris C, Danielle LC, Boland P, Doherty AJ, Benedetto V, Gita BE, Clegg AJ. The prevalence of mental health conditions in healthcare workers during and after a pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(6):1551–1573. doi: 10.1111/jan.15175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang Y, Zhao N. Chinese mental health burden during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102052. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57.Huang Y, Zhao N. Mental health burden for the public affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in China: who will be the high-risk group? Psychol Health Med. 2021;26(1):23–34. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1754438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jo SH, Koo BH, Seo WS, Yun SH, Kim HG. The psychological impact of the coronavirus disease pandemic on hospital workers in Daegu. South Korea. Compr Psychiatry. 2020;103:152213. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jolley D, Douglas KM. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jolley D, Paterson JL. Pylons ablaze: Examining the role of 5G COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. Br J Soc Psychol. 2020;59(3):628–640. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jovancevic A, Milicevic N. Optimism-pessimism, conspiracy theories and general trust as factors contributing to COVID-19 related behavior - A cross-cultural study. Pers Individ Dif. 2020;167:110216. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knolle F, Ronan L, Murray GK. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a comparison between Germany and the UK. BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):60. doi: 10.1186/s40359-021-00565-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lazarevic LB, Puric D, Teovanovic P, Lukic P, Zupan Z, Knezevic G. What drives us to be (ir)responsible for our health during the COVID-19 pandemic? The role of personality, thinking styles, and conspiracy mentality. Pers Individ Dif. 2021;176:110771. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leibovitz T, Shamblaw AL, Rumas R, Best MW. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: relations with anxiety, quality of life, and schemas. Pers Individ Dif. 2021;175:110704. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]