Abstract

Urothelial carcinoma (UC) is the most frequent malignancy of the urinary tract, which consists of bladder cancer (BC) for 90%, while 5% to 10%, of urinary tract UC (UTUC). BC and UTUC are characterized by distinct phenotypical and genotypical features as well as specific gene- and protein- expression profiles, which result in a diverse natural history of the tumor. With respect to BC, UTUC tends to be diagnosed in a later stage and displays poorer clinical outcome. In the present review, we seek to highlight the individuality of UTUC from a biological, immunological, genetic-molecular, and clinical standpoint, also reporting the most recent evidence on UTUC treatment. In this regard, while the role of surgery in nonmetastatic UTUC is undebated, solid data on adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy are still an unmet need, not permitting a definite paradigm shift in the standard treatment. In advanced setting, evidence is mainly based on BC literature and retrospective studies and confirms platinum-based combination regimens as bedrock of first-line treatment. Recently, immunotherapy and target therapy are gaining a foothold in the treatment of metastatic disease, with pembrolizumab and atezolizumab showing encouraging results in combination with chemotherapy as a first-line strategy. Moreover, atezolizumab performed well as a maintenance treatment, while pembrolizumab as a single agent achieved promising outcomes in second-line setting. Regarding the target therapy, erdafitinib, a fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitor, and enfortumab vedotin, an antibody-drug conjugate, proved to have a strong antitumor property, likely due to the distinctive immune-genetic background of UTUC. In this context, great efforts have been addressed to uncover the biological, immunological, and clinical grounds in UTUC patients in order to achieve a personalized treatment.

Keywords: upper tract urinary carcinoma, genomic profile, immune background, clinical management

Introduction

Urothelial carcinoma (UC) is the most frequent tumor of the urinary system, it may originate from lower (bladder and urethra) or upper (renal pelvis, calyces, and ureter) urinary tract.

Bladder cancer (BC) makes up 90% of UCs and, according to 2022 National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program, kidney, and renal pelvis cancer represents 4.1% of all new cancer cases in the US, with 79 000 new diagnoses in 2022.1

Upper urinary tract UCs (UTUC) accounts for 5% to 10% of UCs, with an estimated annual incidence of almost 2 cases per 100 000 persons.2

Even though BC and UTUC both derive from the urothelium, they arise from separate embryonic tissues, therefore presenting distinct phenotypical and genotypical (genetic and epigenetic) profiles with relevant clinical and therapeutic implications.3 Moreover, the physiologic function of the upper urinary tract (ie urine collection from the kidney and “transport” of urine, by pressure and gravity, to the bladder) is different from the bladder function (ie reservoir), resulting in different “time of contact” between urine and urothelium. UTUC is associated with specific risk factors including exposure to smoking, aristolochic acid (potentially leading to the Balkan endemic nephropathy, a familial chronic tubulo-interstitial disease with a slow progression to terminal renal failure4), arsenic or occupational carcinogens, analgesic abuse, hypertension, long-standing urinary obstruction, and it is common in patients with Lynch syndrome (LS).5 From a genetic point of view, recent molecular studies provided evidence of different gene- and protein-expression profiles in BC and UTUC,6 while in terms of immunopathological features UTUC results predominantly luminal papillary and T-cell deplet.7

UTUC appears to be more aggressive than BC, and correlates with poor clinical outcomes: two-thirds of UTUC are invasive at diagnosis, with a 5-year specific survival ranging from 50% for pT2/T3 stage to 10% for pT4 stage.2 Older age, smoking status, poor performance status, obesity, ureteral site or multifocal tumors and delay between diagnosis and surgery are all preoperative factors associated with decreased cancer-specific survival (CSS); postoperative prognostic factors include tumor stage and grade, lymph node (LN) involvement, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), positivity of surgical margins and extensive tumor necrosis.2

According to the European Association of Urology Treatment Guidelines the gold standard for localized low-risk UTUC is kidney-sparing surgery (KSS), followed by endocavitary treatment with chemotherapeutic agents and/or Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG). Radical nephroureterectomy (RNU) with bladder cuff excision and LN dissection associated with adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy is the treatment of choice for high-risk UTUC.2,8 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be considered.9

Metastatic disease is treated with systemic therapy. Platinum-based chemotherapy represents the backbone of first-line treatment strategies, while there is no defined therapy for later lines. Recent evidence supports the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), although not allowing any definite conclusion.10,11

In this review, we aim to provide the latest updates about UTUC characteristics, biological and clinical behavior, and therapeutic management, in order to underline its distinctiveness and improve our understanding of this complex and still lethal disease (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphical abstract illustrating the main urinary tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC)-centred fields analyzed in the present review.

Methods

The present work is not intended to be a systematic review, nonetheless we employed the following search strategy and specific keyword combinations to exploit the Medline database through PubMed: “urothelial carcinoma,” “upper urinary tract carcinoma,” “genetics,” “embryogenesis,” “immune microenvironment,” “molecular subtypes,” “prognosis,” “clinical management,” “treatment,” “chemotherapy,” “immunotherapy,” “surgery,” “radiotherapy,” “biomarkers.” No restrictions were placed on the year of publication. Identified original/review articles were examined and the most relevant works were selected according to their level of evidence.

Results

UTUC as a Distinct Tumor Disease

Embryogenesis

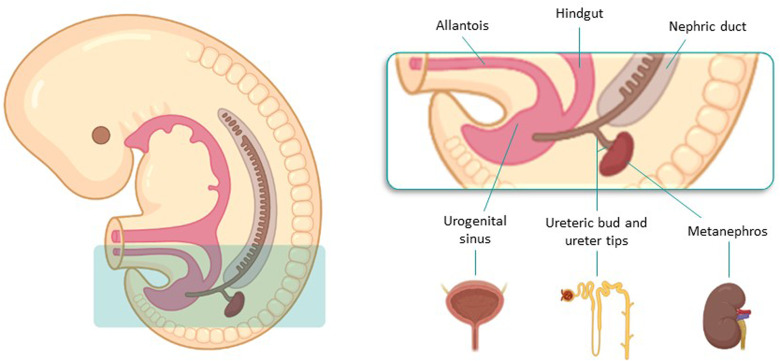

Urinary tract development starts in the fifth gestational week by the union of structures from different embryological origins and requires reciprocal interactions between epithelia (epithelial ureteric bud, UB) and mesenchyme.12,13 The UB emerges from the nephric duct (ND), that is the central component of pro/mesonephros, and originates from mesoderm cells of mid-gestation embryos. It eventually forms the collecting duct and ureter of the adult kidney (called the metanephros), while ureter tips induce the formation of nephrons from the circumjacent mesenchyme.12 Conversely, bladder structure stems from the urogenital sinus, which derives from the urogenital septum and also forms the urethra14 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of UTUC embryogenetic process.

Urinary tract development starts in the fifth gestational week, by the union of UB and mesenchyme. The UB emerges from the nephric duct and eventually forms the metanephros, while ureter tips induce the formation of nephrons from the circumjacent mesenchyme. Bladder sructure originates from the urogenital sinus. Abbreviations: UTUC, urinary tract urothelial carcinoma; UB, ureteric bud.

To date, 3 classes of secreted proteins are known to be responsible for mesenchymal signals for urothelial development: bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4), retinoic acid (RA), and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs).15 Forkhead Box F1 (FOXF1) regulates the expression of BMP4 in the ureteric mesenchyme and is, in turn, regulated by the epithelial sonic hedgehog (SHH) signal, whose gene is expressed in the cloaca epithelia.16 SHH-FOXF1-BMP4 axis controls epithelial differentiation, survival, proliferation and smooth muscle cell differentiation of the surrounding mesenchymal cells.15 PAX2, PAX8, GATA3, and RET genes appear to be implicated in the regulation of ND morphogenesis.12,17,18

In the view of this complex and multifaceted embryogenetic process, urothelial umbrella cells of the human ureter significantly differ from bladder cells in their uroplakin content, keratin expression pattern, and extracellular matrix-associated proteins.13,19 Moreover, embryogenetic differences between the bladder and ureter are also reflected in distinctive genetic-molecular and immune microenvironmental features of BC and UTUC.

Based on these elements, we speculate that the distinct embryonic origins of UTUC and BC could impact on the specific biological pattern of the neoplasms and their different pharmacological sensitivity

Genomics

Several studies aimed at exploring the molecular background of UTUC in order to better understand the disease and identify specific gene alterations, acting as potential targets for precision medicine.

Some of the strongest evidence emerging from all the published works is that BCs and UTUCs are characterized by a distinct genomic landscape; specifically, although the alterations are usually similar, they present a different prevalence.20

According to the main findings of several papers, the principal mutated genes in UTUCs are fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) (20%-74%), chromatin remodeling genes such as KMT2D (27%-65%), KDM6A (10%-94%), STAG2 (7%-60%), CDKN2A (5%-50%), TP53 (0%-47%) and HRAS (2%-13%). The relative percentages are reported in Table 1.7,20–25 Usually, in upper tract carcinoma, the alterations in RTK/RAS/MAPK or FGFR pathways and p53/MDM2 axis, are mutually exclusive.20

Table 1.

Overview of the Principal Mutated Genes in UTUC.

| Study | FGFR3 | KMT2D | KDM6A | STAG2 | CDKN2A | TP53 | HRAS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sfakianos et al20 | 54% | 35% | 34% | 22% | 21% | 18% | 10% | |

| Moss et al21 | Overall | 74% | 44% | 22% | 7% | 18% | 22% | NA |

| LG | 92% | |||||||

| HG | 60% | |||||||

| Donahue et al24 | sporadic | 50% | 27% | 37% | 23% | 21% | 18% | NA |

| LS | 65% | 65% | 94% | 18% | 24% | 29% | NA | |

| Robinson et al7 | 30% | 35% | 11% | 8% | 5% | 32% | 3% | |

| Audenet et al22 | 40% | 37% | 32% | 16.5% | 22% | 26% | 12% | |

| Nassar et al23 | LG | 80% | NA | 50% | 60% | 50% | 0% | 10% |

| HG | 16% | NA | 20% | 13% | 20% | 47% | 13% | |

| Yang et al25 | 20% | 57% | 18% | NA | NA | 41% | NA | |

Abbreviations: FGFR3, fibroblast growth factor receptor 3; KMT2D, Lysine methyltransferase 2D; KDM6A, lysine demethylase 6A; STAG2, stromal antigen 2; CDKN2A, cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A; TP53, tumor protein 53; HRAS, Harvey rat sarcoma virus; LG, low grade; HG, high grade; LS, Lynch syndrome; UTUC, urinary tract urothelial carcinoma.

Conversely, BC has more frequent variations in p53-MDM2 pathway genes, ARID1A, PIK3CA, RB1, ERBB2, and cell cycle pathway-associated genes, the latter especially in metastatic disease.20,22 Mutations in INPPL1 were only observed in BC.25

BC seems to have a higher median tumor mutational burden6 and DNA damage repair (DDR) gene mutations,23 while UTUC has been found to exhibit more microsatellite instability (MSI)26,27 and hypermethylation.28

Yang et al25 identified distinct mutational signatures between the 2 sites: BC is often characterized by a mutational signature determining the activation of APOBEC cytidine deaminases (43%), bound to viral infection, retrotransposon jumping or inflammation, whereas UTUC presents more commonly a signature causing deamination of 5-methylcytosine (42%) (Table 1).

Studies inspecting the link between genomic and clinicopathological behavior documented that FGFR3, CREBBP, and STAG2 are typical of low-grade (LG) tumors, while high-grade (HG) UTUCs usually display alterations in TP53, RB1, CDKN2A, and CDKN2B genes, and greater genomic instability20,21,23 (Table 1).

Moreover, significant correlations between gene expression and T stage have been reported: pTa/pT1/pT2 stages have alterations in FGFR3, HRAS, and the RTK/RAS pathway, while TP53, CCND1, ERBB2, ERBB3, and KRAS are typical of pT3/pT4.20,22

Contrasting results on the impact of FGFR3 emerged from the studies conducted by Van Oers et al29 and Nassar et al,23 which respectively documented a better survival in patients affected by pT2-pT4 UTUC with FGFR3 mutation, and an association between PIK3CA, EP300, and FGFR3 mutations with poorer survival.

Recently, several works aimed at characterizing gene expression profiles in BC and UTUC, in order to illustrate molecular subtypes, with distinct biological behavior, prognosis and pharmacological sensitivity. With regard to UTUC, a seminal work by Fujii et al30 identified, through an integrated genomic analysis of 199 UTUC cases, 5 molecular subtypes (hypermutated, TP53/MDM2, RAS, FGFR3, and triple negative [TN]) which correlated with distinct gene expression profiles, tumor location/histology and clinical outcomes. When it comes to BC, Kamoun et al31 focused on genomic alterations in 7 genes, FGFR3, CDKN2A, PPARG, ERBB2, E2F3, TP53, and RB1, and provided a consensus set of 6 molecular classes, characterized by distinct cells infiltration, oncogenic mechanisms, and clinical features: luminal papillary (24%), luminal nonspecified (8%), luminal unstable (15%), stroma-rich (15%), basal/squamous (35%), and neuroendocrine-like (3%).

The Lynch Syndrome

The hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer Syndrome, known as LS, is an autosomal dominant syndrome caused by germline mutations of mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2). It is characterized by a higher incidence of neoplasms like colorectal cancer, endometrial or ovarian cancer, tumors of the small bowel, biliary tract, stomach, and pancreas, and also of the skin, brain or genitourinary tract.32 Specifically, UTUC is the third most frequent malignancy in LS,33 with a lifetime risk of 8.4%.

For this higher incidence, the current European guidelines recommend screening for LS in patients younger than 60 years old, affected by UTUC.2

Patients with LS-associated UTUC are usually younger, affected in the ureter site, with lower exposure to tobacco.24

Donahue and colleagues juxtaposed the genomic background of patients with LS-associated UTUC and the sporadic one, revealing that LS-UTUC was characterized by a higher median number of mutations per tumor and higher frequency of MSI. Specifically, MSI-high LS-UTUC presents more frequent variations in DDR genes, KMT2D, CREBBP, SMARCA4, and ARID1A. Furthermore, alterations in CIC, FOXP1, NOTCH1, NOTCH3, and RB1 resulted nearly exclusive to the LS cohort.

Immune Background

The role of UTUC tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) has been deeply examined both by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and gene-expression analyses. Nonetheless, our knowledge of the immune milieu of UTUC still results incomplete.

Several investigations have delved into the impact of distinct TIME components, mostly embodied by PD-L1 expression and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) density, on patient survival and response to treatment, although without reaching a consensus. Krabbe et al34 have identified PD-L1 positivity as an independent prognostic factor of favorable outcome, while other studies have documented a significant association between higher tumor PD-L1 expression and shorter CSS35 or overall survival (OS).36 Similarly, a recent metanalysis involving 1406 UTUC patients (from 8 retrospective studies) highlighted that PD-L1 overexpression was related to worse survival outcomes in UTUC patients following RNU.37 Concerning TILs density and functional properties, Nukui et al38 observed a positive correlation between higher TILs and poorer differentiation, local invasiveness, OS and progression-free survival (PFS) on univariate analysis, while the work by Wang et al39 upheld the positive prognostic value of high CD8+ TILs in terms of both disease-free survival (DFS) and OS.

In the view of the critical role of TIME in dictating tumor evolution and modulating response to standard-of-care therapies, several strategies have been developed to therapeutically target each TIME component. Currently, advanced TIME-directed therapies have either been clinically approved or are currently being evaluated in trials, including immunotherapies (ie anti-LAG-3, TIM3, TIGIT), antiangiogenic drugs, and agents directed against cancer-associated fibroblasts and the extracellular matrix.40

To dissect the main features of UTUC immune cell compartments, Robinson and colleagues have analyzed whole-exome sequencing and RNA sequencing data from HG UTUC tumors showing that UTUC phenotype was predominantly luminal papillary and T-cell depleted.7 Moreover, they designated FGFR3 as a putative regulator of UTUC immune contexture through the attenuation of interferon gamma signalling, thus partly explaining the well-known limited efficacy of immunotherapy and shedding new light on this still uncovered disease.

Clinical Management

Diagnosis and Staging

Hematuria is usually the earliest symptom of UTUC, but the diagnosis may be also incidental. Nearly 7% of UTUC is already metastatic at diagnosis, thus exhibiting systemic symptoms.2 In the case of hematuria, an abnormal urinary cytology with normal cystoscopy may suggest HG invasive UTUC.41 In suspicion of UTUC, computed tomography urography (CTU) has the highest diagnostic accuracy, and it is able to identify ureteral wall thickenings, infiltrating lesions or filling defects. Nonetheless, flat lesions, wall invasiveness, and superficial extension of tumors remain difficult to assess.42

Magnetic resonance urography is usually performed when iodinated contrast is contraindicated. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is required to evaluate LN involvement and distant metastasis, while a recent retrospective multicentre study on the use of 18F-Fluorodeoxglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for the detection of nodal metastasis in 117 surgically-treated UTUC patients reported promising sensitivity and specificity of 82% and 84%, respectively.43 A flexible ureteroscopy (URS) has to be performed to characterize suspected lesions and take biopsy.2 Narrow band imaging, optical coherence tomography and confocal laser endomicroscopy are promising imaging technique which may enhance visualization of tumor microarchitecture.41 URS biopsy has a diagnostic and prognostic role since can inform on tumor grade and stage, key factors in preoperative risk stratification,42 and also enables the ureteral cytology, thus increasing the sensitivity of the procedure.2

Nevertheless, unlike bladder tumor, a significant discordance between URS biopsy and final pathology has been reported,44 since some URS biopsy specimens are so small to preclude any accurate assessment of invasiveness, thus carrying the risk of understaging.42,45 To minimize this eventuality, a flat-wire basket can be used to perform biopsy, increasing procedure accuracy.46

TNM classification 2017 is the selected staging system. Differently from BC, a subclassification of muscle wall invasion is not performed, due to the thinner muscle layer of upper tract urinary wall.47

Therapeutic Approaches: Localized Disease

Role of Surgery

The gold standard treatment for HG or invasive nonmetastatic UTUC is RNU with bladder cuff excision and template lymphadenectomy, regardless of tumor location. With similar survival benefits, KSS is the preferred approach for LG or noninvasive distal ureteral tumors. In addition, KSS should be considered in selected patients with a serious impaired renal function or solitary kidney.2

Nephron-sparing techniques consist mainly of ureteroscopic ablation and segmental ureteral dissection. The endoscopic management is practicable only for patients with low-risk cancer suitable for complete tumor resection. Percutaneous approach, although not routinely employed due to the availability of advanced endoscopic tools, might be pursued in low-risk UTUC of the renal pelvis which are inaccessible or difficult to manage by flexible URS. Complete distal ureterectomy with neo-cystostomy is indicated for low-risk tumors of the distal ureter which cannot be radically removed endoscopically, whereas segmental resection of the proximal and mid ureter is associated with higher failure rates compared to the distal pelvis. Partial pyelectomy or partial nephrectomy are extremely rarely indicated.48,49

Common postsurgical complications include early and delayed hematuria, wound infections, ileus, incisional hernia, and pneumothorax. Ni et al,50 showed that laparoscopic nephroureterectomy and the open technique offer similar perioperative safety and comparable oncologic efficacy. According to a review by Linehan et al,51 the major complications of an endoscopic approach may range from potentially life threatening (eg, sepsis or acute renal failure) to less serious. The most frequently reported complications are ureteral stricture or stenosis, hematuria, pain, LG fever, infections, and ureteral perforation.

Differently from the UC of the bladder, biopsy specimens from ureteroscopic staging do not enable an adequate assessment of the depth of infiltration into the upper urinary tract wall. Therefore, in order to obtain a sufficient biopsy specimen, the decision between RNU or KSS is predominantly based on the preoperative imaging combined with the tumor grade. Considering the risk of understaging and undergrading associated with endoscopic management, an intensive follow-up is recommended when kidney-sparing treatment is chosen.41

There is no oncological benefit for surgery in patients with metastatic UTUC, except for palliative care.52

Role of Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapy

Based on retrospective studies, neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed promising outcomes compared to RNU alone, with encouraging pathological downstaging and better.2,53–57 However, no randomized prospective trials have been published yet. Chemotherapy regimens adopted in UTUC patients are largely based on those employed for BC.2

The use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in UTUC holds various advantages (ie the chance of delivering higher dose of chemotherapy before surgery, testing chemosensitivity of the disease, tumor downstaging), and limitations (including the risk of overtreatment before an accurate pathological diagnosis).58–60 A phase II trial showed a 14% pathological complete response (CR) rate, obtaining a pathological stage minor than ypT1 in more than 60% of patients.61 A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with RNU alone, was associated with significantly better outcomes, in terms of pathologic CR rate (≤ ypT0N0M0), which resulted 11%, pathologic partial response (PR) rate (≤ ypT1N0M0) reaching 43%, and a pathological downstaging (cT > pT), documented in 33% of patients. Moreover, neoadjuvant chemotherapy led to higher performance in OS [HR 0.44] and CSS [HR 0.38]9 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prospective Studies Assessing Different Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Regimens in Localized UTUC.

| Trial | Drug | Study design | Setting | Overall pts n, UTUC pts n (%) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant | |||||

| Siefker-Radtke et al 201362 | IAG followed by CGI | Phase II | Neoadjuvant | 65, 5 (8) | Pathologic downstaging to ≤ pT1N0: BC pts 50%, UTUC pts 60%; pT0 rate: BC pts 43%, UTUC pts 0% |

| Hoffman- Censits et al 201463 | Accelerated MVAC | Phase II | Neoadjuvant | 10, 10 (100) | pCR rate 10%, pTD < pT1 40%, pTD < pT2 40%, pTD > pT3 or N + 30% |

| McConkey et al 201664 | DD-MVAC with bevacizumab | Phase II | Neoadjuvant | 60, 16 (27) | Pathologic downstaging to ≤ pT1N0: BC pts 45%, UTUC pts 75%; pT0N0 rate: BC pts 39%, UTUC pts 38% |

| Coleman et al 201965 | GemCis | Phase II | Neoadjuvant | 55, 55 (100) | Pathologic downstaging to < pT2N0: 58%; pT0N0 rate: 19% |

| Margulis et al 202061 | Accelerated MVAC/GemCarbo | Phase II | Neoadjuvant | 35, 35 (100) | pCR rate: aMVAC arm 14%, GCa arm 17%; ≤ pT1 rate: aMVAC arm 62%, GCa arm 50% |

| Adjuvant | |||||

| Birtle et al 2020 (POUT trial)8 | GemCis/GemCarbo versus Observation | Phase III | Adjuvant | 261, 261 (100) | mDFS: NR versus 29.8 months (95% CI, 13.6—not calculable) [HR 0.45 (95% CI 0.30-0.68) p = .0001] |

| Bajorin et al 2021 (CheckMate 274)66 | Nivolumab | Phase III | Adjuvant | 709, 149 (21) | mDFS: ITT population 20.8 months (95% CI, 16.5-27.6) versus 10.8 months (95% CI, 8.3-13.9) [HR 0.70 (98.22% CI 0.55-0.90)] |

Abbreviations: IAG, ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and gemcitabine; BC, bladder cancer; Pts, patients; pCR, pathologic complete response; pTD, pathologic tumor downstaging; MVAC, methotrexate, vinblastine sulfate, doxorubicin hydrochloride (Adriamycin); DD, dose dense; GemCis (GC), gemcitabine, cisplatin; GemCarbo (GCa), gemcitabine, carboplatin; Pts, patients; OS, overall survival; mDFS, median disease-free survival; ITT, intention to treat; NR, not reached; HR, Hazard ratio; UTUC, urinary tract urothelial carcinoma.

Nevertheless, the evidence for neoadjuvant chemotherapy is at most derived from retrospective or nonrandomized prospective studies, therefore hampering any strong recommendation9 (Supplemental Table S1).

Conversely, the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in UTUC has been established based on the results of phase III POUT trial, which compared adjuvant gemcitabine-platinum combined therapy (initiated within 90 days after RNU) with surgery alone.8 Adjuvant chemotherapy resulted in significant DFS benefit [HR 0.45] in high-risk nonmetastatic UTUC (pT2-T4 or N1-3 MO), being also associated with improved metastasis-free survival [HR 0.48], acceptable acute toxicities and only a transient deterioration of patient-reported quality of life.8 Specifically, 3-year event-free estimates were 71% (95%CI 61-78) and 46% (95%CI 36%-56%) for chemotherapy and surveillance, respectively. Moreover, although not reaching statistical significance yet, chemotherapy conferred a 30% reduction in relative risk of death [HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.46-1.06; P = .09], with a 3-year OS rate of 79% (95%CI 71%-86%) compared to 67% (95%CI 58%-75%) of patient surveillance.67 Along the same line, in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, adjuvant chemotherapy versus no chemotherapy, demonstrated benefit in OS (pooled HR 0.77), CSS (pooled HR 0.79) and DFS (pooled HR 0.52).9

The adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy is safe. The Pout trial reported a rate of 44% of grade 3 or worse acute treatment-emergent adverse. Patients treated with chemotherapy showed decreases in neutrophils and platelet count, febrile neutropenia, nausea, and vomiting.8

In the phase III CheckMate 274 trial, involving patients with high-risk muscle-invasive UC, adjuvant nivolumab, compared to placebo, improved DFS in the intention-to-treat population (20.8 vs 10.8 months) and among patients with PD-L1 expression ≥ 1%.66 In the subgroup analysis, patients with renal pelvis and ureter tumors do not appear to have benefited from adjuvant nivolumab (HR 1.23 95%CI 0.67-2.23 and HR 1.56 95%CI 0.70-3.48, respectively). Updated results demonstrated 12-month DFS rates of 63.5% in nivolumab-treated patients compared to 46.9% in placebo group,68 although further subgroup analyses mainly focused on UTUC are warranted. On the contrary, the phase III IMvigor010 study, including 54 (6.7%) UTUC patient and evaluating the role of adjuvant atezolizumab versus observation in muscle-invasive UC, did not meet its primary endpoint of improved DFS,69 thus highlighting the still unclear benefit from adjuvant ICIs in this setting. Nonetheless, the subsequent subgroup analysis conducted by Powles and colleagues reinforced the role of circulating-tumor DNA (ctDNA) as a promising biomarker for molecular residual disease and relapse, and led to the design of the prospective randomized IMvigor 011 trial, testing adjuvant atezolizumab only in ctDNA positive cases.69,70

Despite clear survival benefits deriving from adjuvant chemotherapy, one of the main drawbacks is still the restrained capacity to deliver full doses of cisplatin-based regimens after surgery.2,71,72

All things considered, the evidence for adjuvant chemotherapy appears stronger (with high level of evidence) (Table 2, Supplemental Table S2) than that for neoadjuvant treatment, but data are still insufficient to provide strong recommendations.9

Role of Radiotherapy in Unresectable Disease

The role of radiotherapy (RT) for UTUC management has not been clearly elucidated, since evidence on salvage/palliative RT in patients with recurrent UTUC is still scarce.73

RT may offer a safe therapeutic alternative in such patients with nonmetastatic UTUC who cannot tolerate or refuse surgery.74

Therapeutic Approaches: Advanced Disease

Role of CT in Metastatic Disease

Since limited data are available on management of advanced-stage UTUC, evidence is mainly extrapolated from BC literature and supported by retrospective studies demonstrating that the location of primary tumor (lower vs upper urinary tract) do not significantly affect PFS and OS in patients with metastatic UC treated with platinum-based combinatory approaches.75,76

Platinum-based combination regimens represent the mainstay in first-line treatment, whereas monotherapy is employed as a second- or more-line therapeutic strategy, in detail, single-agent immunotherapy in second-line setting, and enfortumab vedotin in third-line setting.

Specifically, cisplatin-based regimes, such as methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin or GC (gemcitabine and cisplatin) represent the standard of care in first-line setting and lead to a median OS of around 9 to 15 months.77,78 Carboplatin-based combinations constitute an alternative in patient ineligible for cisplatin due to comorbidities or impaired renal function, although being associated with a short duration of response, poor survival, and high toxicity.79,80

Scarce data are available about the efficacy of other chemotherapeutic agents administered in subsequent lines. Vinflunine plus best supportive care showed a modest, although significant, benefit in OS compared with best supportive care alone, and might be employed as second- or third-line treatment.81

Role of ICIs and Novel-Targeted Therapy in Metastatic Disease

Immunotherapy was evaluated as first-line treatment, either in combination with chemotherapy, or alone in platinum unfit patients, or as maintenance treatment after platinum-based regimens. The efficacy of atezolizumab-based first-line therapy was evaluated in several trials: as single agent, in phase II, single-arm IMvigor 210 study,65 which included patients with locally advanced or metastatic UC patients unfit for cisplatin; in combination with cisplatin-based chemotherapy, in phase III, randomized IMvigor 130 trial, involving metastatic urothelial cancer cases.82,83 Phase II, single-arm KEYNOTE 052 trial, assessed the activity of first-line pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer.84 Overall, 414 UTUC patients were enrolled in the 3 studies. Overall response rate (ORR) ranged from 22% to 39%. Of note, the combination of atezolizumab with chemotherapy demonstrated a relevant prolongation of PFS compared to chemotherapy alone.83 Both atezolizumab and pembrolizumab administered as monotherapy in cisplatin unfit patients showed encouraging response rates, survival, and tolerability.82,84

JAVELIN Bladder 100 trial, a phase III study assessing the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 avelumab, as maintenance therapy after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, documented significantly improved OS in the experimental arm which included 106 patients with unresectable UTUC85 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Studies Assessing ICIs as First-Line Therapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic UTUC.

| Trial | Drug | Study design | Overall pts n, UTUC pts n (%) | Outcomes in the overall population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMvigor 21082 | Atezolizumab | Phase II | 119, 33 (28%) cisplatin ineligible pts | ORR 23% (95%CI 16-31) |

| IMvigor 13083 | Atezolizumab plus platinum-based CT (group

A) Atezolizumab (group B) Platinum-based CT (group C) |

Phase III | 1213, 312 (26%) | mPFS 8.2 months (95%CI 6.5-8.3) in group A and 6.3

months (95%CI 6.2-7.0) in group C (stratified HR

0.82, 95%CI 0.70-0.96, one-sided

p = 0·007); mOS 16.0 months (95%CI 13.9-18.9) in group A and 13.4 months (95%CI 12.0-15.2) in group C (HR 0.83 95%CI 0.69-1.00, one-sided p = 0·027); mOS 15.7 months (95% CI 13.1-17.8) for group B and 13.1 months (95%CI 11.7-15.1) for group C (HR 1.02 95%CI 0.83-1.24). |

| KEYNOTE 05284 | Pembrolizumab | Phase II | 370, 69 (19%) Cisplatin ineligible pts |

ORR 24% (95%CI 20-29) in ITT population; ORR 38% (95%CI 29-48) in PD-L1 ≥ 10% population |

| JAVELIN Bladder 10085 | Avelumab versus BSC | Phase III | 700, 187 (27%) | mOS: 21.4 months versus 14.3 months [HR 0.69 (95% CI 0.56-0.86), p = .001]. |

Abbreviations: UTUC, upper tract urothelial cancer; pts, patients; ORR, objective response rate; CI, confidence interval; CT, chemotherapy; mPFS, median progression-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; mOS, median overall survival; ITT, intention to treat; PD-L1, programed death ligand 1; BSC, best supportive care; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor.

Concerning the second-line setting, several phase I, II, and III studies tested atezolizumab,86–88 pembrolizumab,89 durvalumab,90 avelumab,91 and nivolumab92,93 in platinum pretreated patients with advanced UC. Among all the above-mentioned compounds, pembrolizumab demonstrated a significant improvement in survival compared to chemotherapy in KEYNOTE 045 trial, in which UTUC patients accounted for 14% 89 (Table 4): in the subgroup analysis the HR for patients with UTUC was better compared with lower tract tumors (HR 0.53 95%CI 0.28-1.01 and HR 0.77 95%CI 0.60-0.97, respectively) .89

Table 4.

Studies Assessing ICIs as Second or More Line Therapy in Locally Advanced or Metastatic UTUC.

| Trial | Drug | Study design | Overall pts n, UTUC pts n (%) | Outcomes in the overall population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT 0210865286 | Atezolizumab | Phase II | 310, not specified | ORR 15% (95%CI 11-20) |

| IMvigor 21187 | Atezolizumab versus Paclitaxel/Docetaxel/Vinflunine | Phase III | 931, 236 (25%) | mOS: 11.1 (95%CI 8.6-15.5) versus

10.6 months (95%CI 8.4-12.2), P = .41 |

| SAUL88 | Atezolizumab | Phase II | 997, 219 (22%) | ORR 13% (95%CI 11-16) |

| KEYNOTE 04589 | Pembrolizumab versus Paclitaxel/Docetaxel/Vinflunine | Phase III | 748, 75 (10%) | mOS: 10.3 months (95%CI 8.0 to 11.8)

versus 7.4 months (95%CI, 6.1 to

8.3) [HR 0.73 (95%CI 0.59-0.91),

P = .002] mPFS: 2.1 months (95%CI 2.0-2.2) versus 3.3 months (95%CI 2.3-3.5) [HR 0.98 (95%CI 0.81-1.19), P = .42] |

| NCT0169356290 | Durvalumab | Phase I/II | 191, not specified | ORR 17.8% (95%CI 12.7-24.0) |

| JAVELIN Solid Tumor91 | Avelumab | Phase I | 249, 191 (77%) | ORR 17% (95%CI 11-24) |

| CheckMate 27592 | Nivolumab | Phase II | 279, not specified | ORR 19.6% (95%CI 15-24.9) |

| CheckMate 03293 | Nivolumab | Phase I/II | 78, not specified | ORR 24.4% (95%CI 15.3-35.4) |

Abbreviations: UTUC, upper tract urothelial cancer; pts, patients; ORR, objective response rate; CI, confidence interval; mPFS, median progression-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; mOS, median overall survival; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor.

An increasing number of clinical trials are also evaluating novel targeting agents. Erdafitinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of FGFR1-4, was evaluated in BLC2001,94 a single-arm, phase II trial, which included a total of 111 metastatic patients, out of which 33 were affected by UTUC, harboring FGFR3 mutation or FGFR2/3 fusion. Median PFS and OS of the overall population were 5.5 and 13.8 months, respectively, with an ORR of 40%. Moreover, Ding et al95 reported the case of a 67 years old metastatic, chemo-refractory UTUC patient displaying a dramatic response to pembrolizumab in association with erdafitinib.

Among antibody-drug conjugates, enfortumab vedotin, a novel agent targeting the surface protein nectin-4 highly expressed in UC, demonstrated robust antitumor activity in a phase III study including patients previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and ICIs. Out of 608 patients enrolled, the primary tumor was localized in upper tract in 205 patients. The subgroup analysis revealed a significant benefit in terms of OS in patients with BC [HR 0.67 (0.51-0.88)], while not reaching statistical significance in patients with UTUC [HR 0.85 (0.57-1.27)].96

Finally, numerous trials assessing backbone ICI in combination with chemotherapy, antibody-drug conjugates and tyrosine kinase inhibitors as first- or more-line treatment in UTUC metastatic setting are currently ongoing, underlying the strong biological, immunological, and clinical rationale of personalized therapy in UTUC.10

Role of RT in Advanced Disease

Among other therapeutic approaches, the role of RT is still marginal, both in metastatic BC and UTUC, being administered mostly with a symptomatic/palliative intent.97 The current evidence supports the use of RT to rapidly and effectively minimize tumor-induced urinary symptoms, such as hematuria, and demonstrates a similar symptom improvement following hypofractionated palliative RT compared to multifractionated treatments.97 In addition, as reported by a recent Japanese study, in a selected patient population, consolidative RT (usually more than 50 Gy) may result in long-term disease control and improved quality of life.98 Finally, although based on a small number of observations, a potential role of stereotactic body radiation therapy in specific cases of oligometastatic UC displaying distant node metastases, has been advised.99

Prognostic and Predictive Factors

Preoperative stratification into low and high-risk UTUC is fundamental to select patients who are eligible for KSS treatment or RNU,2 and it is practically based on tumor size, disease focality, cytological and histological grade, histological variants, invasive aspects on CTU, hydronephrosis and history of BC. Other preoperative factors have been demonstrated to impact on prognosis: sessile growth pattern, renal pelvis location, advanced age, too low or too high body mass index, diabetes, and poor performance status confer a worse CSS.2,41,100 Furthermore, smoking exposure and history of BC are associated with a higher risk of intravesical recurrence.2,41

Concerning morphologic classification, it is a well-established notion that pure UCs are characterized by a favorable disease course, while histologic tumor variants are usually associated with advanced stage, multifocality, sessile architecture, necrosis, LVI, and LN metastasis.101

Several models combining clinical, endoscopic, and imaging features have been developed to improve preoperative risk stratification, although mostly based on retrospective studies with a small sample size.41,45

In the postoperative setting, different nomograms relying on pathological features, have been generated to improve decision-making.41,100 High tumor grade and stage, LN involvement, LVI, and extensive tumor necrosis are linked to worse prognosis.2,102 Furthermore, positive tissue surgical margins, concomitant carcinoma in situ and macroscopic infiltration of peripelvic adipose tissue have been associated with higher risk of recurrence.2,100 Similarly, high expression of immunosuppression proteins such as Tim-3 and PD-1, has been related to bladder recurrence.103

Among pathological information, solely available after radical surgery, the investigation of specific molecular markers, such as ERBB2 amplification, FGFR3, and TP53 mutation, is known to improve the assessment of oncological outcomes.5,104 Some works have been focused on tissue RNA expression profiles able to subdivide UTUC in molecular subtypes exhibiting distinct clinical characteristics and outcomes.30,45 Moreover, significant prognostic tissue markers, obtained by immunohistochemical analysis on tissue microarrays, have been proposed. In detail, epidermal growth factor receptor/erythroblastosis oncogene B (c-erb), retinoblastoma protein loss, cyclin D1, high molecular-weight cytokeratin, and with E-cadherin have been demonstrated to be variably associated with OS, DFS, and intravesical recurrence-free survival.36

Beyond the above-mentioned parameters, new prognostic tools are increasingly being explored, especially those that are noninvasive. Analysis of urinary cell-free DNA addressing either genomic or epigenomic alterations, holds great potential as a noninvasive method for the diagnosis of UC, including UTUC, and might also be predictive of prognosis and treatment response.105

In localized disease, the relevance of ctDNA in identifying patients who may benefit from adjuvant atezolizumab-based immunotherapy has been undoubtedly demonstrated, and the assessment of protein and transcriptomic biomarkers offered new immunologically-relevant insights into the biology associated with ctDNA positivity and atezolizumab efficacy.70

Regarding the peripheral blood compartment, there has been an increasing interest in inflammatory markers. Several studies documented that high neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio or monocyte to lymphocyte ratio (MLR) and systemic immune-inflammation index (neutrophils * platelets/lymphocytes), were significantly associated with poor OS and CSS.106,107

Finally, regarding clinical/hematological prognostic factors in metastatic UTUC, a recent work conducted by Bersanelli et al109 provided the first validation of the Sonpavde score108 (including performance status > 0, hemoglobin < 10 g/dl, liver metastases, time from prior chemotherapy ≥ 3 months) in the UTUC population, proving its efficacy and usefulness for the outcome prediction also in these setting of patients.

However, the identification of reliable prognostic and predictive biomarkers able to improve clinical decision-making in UTUC patients, is still an unmet need.

Future Perspectives

Standard chemotherapy regimens administered according to different schedules, as well as novel targeting and immunotherapeutic agents, are currently exploiting in UTUC patients, Ongoing clinical trials (from https://clinicaltrials.gov/) addressed to UTUC cases, are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Actively ongoing studies aimed at assessing different therapeutic combination in locally advanced or metastatic UTUC.

| Trial code | Trial title | Interventions | Phase | Allocation | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant therapy | |||||

| NCT02969083 | Feasibility of neo-adjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy in upper tract urothelial carcinoma (URANUS) | Arm A: RNU only Arm B: NACT (3 cycles of GC or dose dense MVAC) plus RNU Arm C: RNU plus adjuvant CT (3 cycles of GC or dose dense MVAC) |

Phase II | Randomized | Primary: Proportion of pts randomized to CT able to start

and finalize 3 cycles of planned CT Secondary: DFS, OS, CSS |

| NCT02876861 | neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus surgery alone in patients with high-grade UTUC | Active comparator: RNU or DU only Experimental arm: NACT (2-4 cycles of GC) plus RNU or DU |

Phase II | Randomized | Pimary: DFS Secondary: ORR, OS, toxicity |

| NCT02412670 | Chemotherapy before surgery in treating patients with high grade upper urinary tract cancer | Arm A: 4 cycles of MVAC plus surgery Arm B: 4 cycles of GC plus surgery |

Phase II | Nonrandomized (parallel assignment) | Primary: pCR rate Secondary: safety, distant RFS, EFS, bladder cancer-free survival, CSS, renal functional outcomes |

| NCT01261728 | Gemcitabine and cisplatin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with high-grade upper tract urothelial carcinoma | 4 cycles of GC plus RNU or DU | Phase II | NA | Primary: pathologic response rate Secondary: time to disease progression, OS, safety |

| NCT01663285 | Clinical trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in upper tract urothelial carcinoma | 4 cycles of GC plus RNU | Phase II | NA | Primary: RFS time Secondary: number of pts with pathologic T0/Tis/Ta N0, number of pts with AEs |

| NCT04574960 | Neoadjuvant upper tract invasive cancer trial (NAUTICAL) | Experimental arm: NACT with 4 cycles of GC plus

surgery Active comparator: surgery plus adjuvant 4 cycles of GC or Gemcitabine + Carboplatin |

Phase III | Randomized | Primary: feasibility of enrolling UTUC pts in a randomized

trial of NACT versus standard of care, DFS, pCR

rate Secondary: site-specific enrollment rate, number of pts approached per site per month, number of pts randomized per site per month |

| NCT04099589 | Multicenter phase II study of gemcitabine/cisplatin chemotherapy combined with PD-1 inhibitor (Toripalimab) in the neoadjuvant treatment of upper urinary and muscular invasive bladder urothelial carcinoma | Neoadjuvant therapy with Toripalimab + GC plus surgery | Phase II | Non randomized | Primary: pCR rate |

| NCT04617756 | Safety nd efficacy of durvalumab + Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract (iNDUCT) | 4 cycles of durvalumab and GC or gemcitabine + carboplatin plus surgery | Phase II | NA | Primary: pCR Secondary: partial pathological response, safety, OS, |

| NCT04628767 | Testing the addition of MEDI4736 (Durvalumab) to chemotherapy before surgery for patients with high-grade upper urinary tract cancer | Arm A: 4 cycles of durvalumab + MVAC plus surgery Arm B: 4 cycles of MVAC plus surgery Arm C: 4 cycles of durvalumab + gemcitabine plus surgery |

Phase II/III | Randomized | Primary: event-free survival Secondary: pCR, OS, DFS, CSS, renal function outcomes, saftey |

| NCT05160285 | Neoadjuvant nivolumab for upper tract urothelial carcinoma | 3 cycles of neoadjuvant nivolumab plus surgery | Phase II | NA | Primary: pCR rate Secondary: safety, ORR, DFS, OS |

| NCT04672330 | Neoadjuvant PD-1 monoclonal antibody in locally advanced upper tract urothelial carcinoma | 2-4 cycles of neoadjuvant Tislelizumab plus RNU | Phase II | NA | Primary: pathologic response rate Secondary: pathologic downstaging response rate, perioperative complication rate, completion rate of neoadjuvant therapy |

| NCT04672317 | Neoadjuvant PD-1 monoclonal antibody plus cisplatin-based chemotherapy in locally advanced upper tract urothelial carcinoma | 2-4 cycles of Tislelizumab and GC plus surgery | Phase II | NA | Primary: pCR rate Secondary: pathologic response rate |

| NCT04228042 | Infigratinib before surgery for the treatment of upper tract urothelial cancer | 2 cycles of neoadjuvant Infigratinib plus surgery | Phase I | NA | Primary: tolerability Secondary: tolerability in pts with GFR 30-49; ORR after 2 cycles in UTUC with and without FGFR3 alterations; correlate tumor tissue FGFR3 alterations with response and AEs; local/distant recurrence; renal function; patient-reported quality of life outcomes |

| Local therapy | |||||

| NCT03617003 | Treatment of tumors in the urinary collecting system of the kidney or ureter using a light activated drug (WST11) | Intravenous administration of WST11 activated in the tumor by endoscopic phototherapy | Phase I | NA | Primary: Maximum tolerated laser fluence rate |

| NCT01606345 | Phase I study of percutaneous valrubicin for upper tract urothelial carcinoma | Surgery plus percutaneous valrubicin | Phase I | NA | Primary: MTD Secondary: RFS, PFS |

| NCT04398368 | Gemcitabine for the prevention of intravesical recurrence of urothelial cancer in patients with upper urinary tract urothelial cancer undergoing radical nephroureterectomy, GEMINI study | RNU followed by gemcitabine hydrochloride intravesically for at least 1 h | Phase II | NA | Primary: relapse-free survival Secondary: time to recurrence, incidence of AEs |

| NCT04865939 | Gemcitabine versus water irrigation in upper tract urothelial carcinoma | Active Comparator: intravesical instillation of gemcitabine during surgery Experimental: intravesical continuous irrigation with sterile water during surgery |

Noninferiority trial | NA | Primary: 1 and 2 years intravescical

recurrence Secondary: treatment-related associated AEs rate |

| NCT02438865 | Prophylactic intravesical chemotherapy after radical nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma: a randomized controlled trial between single postoperative dose versus maintenance therapy | Active comparator: Single intravesical dose of epirubicin

within 48 h of RNU Active comparator: Single intravesical dose of epirubicin plus a 6 weekly doses of intravesical therapy after surgery then monthly maintenance therapy for 1 year |

Phase II | Randomized | Primary: bladder recurrence Secondary: AEs |

| NCT02793128 | The OLYMPUS study—optimized delivery of mitomycin for primary UTUC study (Olympus) | 6 once weekly intravesical instillations of mitomycin C as ablation treatment | Phase III | NA | Primary: number of pts attaining CR at the end of the

treatment period Secondary: long-term durability of CR for each follow up time point, clinical benefit for pts with partial response, pharmacokinetic |

| Adjuvant therapy | |||||

| NCT03504163 | Pembrolizumab and bacillus calmette-guérin as first-line treatment for high-risk T1 non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer and high-grade non-muscle-invasive upper tract urothelial carcinoma | Surgery plus adjuvant therapy with 9 cycles of pembrolizumab and 6 doses of once-weekly BCG therapy through a percutaneous nephrostomy tube | Phase II | NA | Primary: pts who are disease-free at 6

months Secondary: pts who remain free from high-grade recurrence at 6 months |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; BCG, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin; CSS, cancer-specific survival; CT, chemotherapy; DFS, disease-free survival; DU, distal ureterectomy; EFS, event-free survival; GC, gemcitabine + cisplatin; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; MVAC, methotrexate, vinblastine, adriamycin, cisplatin; NA, not available; NACT, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; pCR, complete pathologic response; PFS, progression free survival; pts, patients; RFS, recurrence-free survival; RNU, radical nephroureterectomy; FGFR3, fibroblast growth factor receptor 3; UTUC, urinary tract urothelial carcinoma.

Conclusive Remarks

In conclusion, UTUC should be considered a unique disease entity in the context of urological malignancies, being endowed with distinctive biologic, genomic, and immune backgrounds which determine a diverse clinical outcome and require tumor-specific management.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-doc-1-tct-10.1177_15330338231159753 for Upper Tract Urinary Carcinoma: A Unique Immuno-Molecular Entity and a Clinical Challenge in the Current Therapeutic Scenario by Giulia Mazzaschi, Giulia Claire Giudice, Matilde Corianò, Davide Campobasso, Fabiana Perrone, Michele Maffezzoli, Irene Testi, Luca Isella, Umberto Maestroni and Sebastiano Buti in Technology in Cancer Research & Treatment

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BC

bladder cancer

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin

- BEN

Balkan endemic nephropathy

- BMI

body mass index

- BMP4

bone morphogenetic protein 4

- cfDNA

cell-free DNA

- ctDNA

circulating-tumor DNA

- CR

complete response

- CSS

cancer specific survival

- CT

computed tomography

- CTU

computed tomography urography

- DFS

disease-free survival

- DDR

DNA damage repair

- FDG PET-CT

fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- FGFs

fibroblast growth factors

- FGFR

fibroblast growth factor receptor

- FOXF1

forkhead box F1

- HG

high-grade

- ICIs

immune checkpoint inhibitors

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- IVRS

intravesical recurrence free survival

- KSS

kidney-sparing surgery

- LG

low-grade

- LN

lymph node

- LS

lynch syndrome

- LVI

lymphovascular invasion

- MLR

monocyte to lymphocyte ratio

- MMR

mismatch repair

- MRU

magnetic resonance urography

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- ND

nephric duct

- NLR

neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio

- ORR

overall response rate

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PR

partial response

- RA

retinoic acid

- RNAseq

RNA sequencing

- RNU

radical nephroureterectomy

- RT

radiotherapy

- SBRT

stereotactic body radiation therapy

- SEER

surveillance, epidemiology and end results

- SHH

sonic hedgehog

- TIL

tumor infiltrating lymphocytes

- TIME

tumor immune microenvironment

- TMAs

tissue microarrays

- TMB

tumor mutational burden

- TN

triple negative

- UB

ureteric bud

- UC

urothelial carcinoma

- URS

ureteroscopy

- UTUC

upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma

- WES

whole-exome sequencing

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Giulia Claire Giudice https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8541-1655

Davide Campobasso https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2072-114X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material (Supplementary Tables S1-S2) for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Kidney and Renal Pelvis Cancer — Cancer Stat Facts. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/kidrp.html. Accessed September 8, 2022.

- 2.Rouprêt M, Babjuk M, Burger M, et al. European association of urology guidelines on upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: 2020 update. Eur Urol. 2021;79(1). doi: 10.1016/J.EURURO.2020.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green DA, Rink M, Xylinas E, et al. Urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and the upper tract: Disparate twins. J Urol. 2013;189(4):1214–1221. doi: 10.1016/J.JURO.2012.05.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefanovic V, Polenakovic M, Toncheva D. Urothelial carcinoma associated with Balkan endemic nephropathy. A worldwide disease. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2011;59(5):286–291. doi: 10.1016/J.PATBIO.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q, Bagrodia A, Cha EK, Coleman JA. Prognostic genetic signatures in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Curr Urol Rep. 2016;17(2):1–8. doi: 10.1007/S11934-015-0566-Y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Necchi A, Madison R, Pal SK, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of upper-tract and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7(6):1339–1346. doi: 10.1016/J.EUF.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson BD, Vlachostergios PJ, Bhinder B, et al. Upper tract urothelial carcinoma has a luminal-papillary T-cell depleted contexture and activated FGFR3 signaling. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10873-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birtle A, Johnson M, Chester J, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in upper tract urothelial carcinoma (the POUT trial): A phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1268–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30415-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leow JJ, Chong YL, Chang SL, Valderrama BP, Powles T, Bellmunt J. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma: A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis, and future perspectives on systemic therapy. Eur Urol. 2021;79(5):635–654. doi: 10.1016/J.EURURO.2020.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Califano G, Ouzaid I, Verze P, Hermieu JF, Mirone V, Xylinas E. Immune checkpoint inhibition in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. World J Urol. 2021;39(5):1357–1367. doi: 10.1007/s00345-020-03502-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bersanelli M, Buti S, Giannatempo P, et al. Outcome of patients with advanced upper tract urothelial carcinoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;159(January):103241. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanchez-Ferras O, Pacis A, Sotiropoulou M, et al. A coordinated progression of progenitor cell states initiates urinary tract development. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1). doi: 10.1038/S41467-021-22931-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cuckow PM, Nyirady P, Winyard PJD. Normal and abnormal development of the urogenital tract. Prenat Diagn. 2001;21(11):908–916. doi: 10.1002/PD.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehman S, Ahmed D. Embryology, Kidney, Bladder, and Ureter. StatPearls. August 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547747/. Accessed July 19, 2022. [PubMed]

- 15.Meuser M, Deuper L, Rudat C, et al. FGFR2 signaling enhances the SHH-BMP4 signaling axis in early ureter development. Development. 2022;149(1). doi: 10.1242/DEV.200021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haraguchi R, Matsumaru D, Nakagata N, et al. The hedgehog signal induced modulation of bone morphogenetic protein signaling: an essential signaling relay for urinary tract morphogenesis. PLoS One. 2012;7(7). doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0042245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laury AR, Perets R, Piao H, et al. A comprehensive analysis of PAX8 expression in human epithelial tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(6):816–826. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0B013E318216C112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoshi M, Batourina E, Mendelsohn C, Jain S. Novel mechanisms of early upper and lower urinary tract patterning regulated by RetY1015 docking tyrosine in mice. Dev. 2012;139(13):2405–2415. doi: 10.1242/DEV.078667/-/DC1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riedel I, Liang FX, Deng FM, et al. Urothelial umbrella cells of human ureter are heterogeneous with respect to their uroplakin composition: Different degrees of urothelial maturity in ureter and bladder? Eur J Cell Biol. 2005;84(2-3):393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2004.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sfakianos JP, Cha EK, Iyer G, et al. Genomic characterization of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2015;68(6):970–977. doi: 10.1016/J.EURURO.2015.07.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss TJ, Qi Y, Xi L, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2017;72(4):641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Audenet F, Isharwal S, Cha EK, et al. Clonal relatedness and mutational differences between upper tract and bladder urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(3):967–976. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nassar AH, Umeton R, Kim J, et al. Mutational analysis of 472 urothelial carcinoma across grades and anatomic sites. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(8):2458–2470. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donahue TF, Bagrodia A, Audenet F, et al. Genomic characterization of upper-tract urothelial carcinoma in patients with lynch syndrome. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018(2):1–13. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang K, Yu W, Liu H, et al. Comparison of genomic characterization in upper tract urothelial carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Oncologist. 2021;26(8):e1395–e1405. doi: 10.1002/ONCO.13839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Catto JWF, Azzouzi AR, Amira N, et al. Distinct patterns of microsatellite instability are seen in tumours of the urinary tract. Oncogene. 2003;22(54):8699–8706. doi: 10.1038/SJ.ONC.1206964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartmann A, Zanardo L, Bocker-Edmonston T, et al. Frequent microsatellite instability in sporadic tumors of the upper urinary tract. Cancer Res. 2002;62(23):6796–6802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Catto JWF, Azzouzi AR, Rehman I, et al. Promoter hypermethylation is associated with tumor location, stage, and subsequent progression in transitional cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):2903–2910. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Oers JMM, Zwarthoff EC, Rehman I, et al. FGFR3 Mutations indicate better survival in invasive upper urinary tract and bladder tumours. Eur Urol. 2009;55(3):650–658. doi: 10.1016/J.EURURO.2008.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujii Y, Sato Y, Suzuki H, et al. Molecular classification and diagnostics of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:793–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.05.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamoun A, de Reyniès A, Allory Y, et al. A consensus molecular classification of muscle-invasive bladder cancer[formula presented]. Eur Urol. 2020;77(4):420–433. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koornstra JJ, Mourits MJ, Sijmons RH, Leliveld AM, Hollema H, Kleibeuker JH. Management of extracolonic tumours in patients with lynch syndrome. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(4):400–408. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70041-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson P, Lynch HT. The tumor spectrum in HNPCC. Anticancer Res. 1994;14(4B):1635–1639. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7979199/. Accessed July 16, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krabbe LM, Heitplatz B, Preuss S, et al. Prognostic value of PD-1 and PD-L1 expression in patients with high grade upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2017;198(6):1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/J.JURO.2017.06.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang B, Yu W, Feng X, et al. Prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression on tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating mononuclear cells in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2017;34(5):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12032-017-0941-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim SH, Park WS, Park B, et al. Identification of significant prognostic tissue markers associated with survival in upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma patients treated with radical nephroureterectomy: A retrospective immunohistochemical analysis using tissue microarray. Cancer Res Treat. 2020;52(1):128–138. doi: 10.4143/crt.2019.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu Y, Kang J, Luo Z, et al. The prevalence and prognostic role of PD-L1 in upper tract urothelial carcinoma patients underwent radical nephroureterectomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2020;10(August):1–11. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nukui A, Kamai T, Arai K, et al. Association of cancer progression with elevated expression of programmed cell death protein 1 ligand 1 by upper tract urothelial carcinoma and increased tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte density. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2020;69(5):689–702. doi: 10.1007/s00262-020-02499-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang LA, Yang B, Rao W, Xiao H, Wang D, Jiang J. The correlation of BER protein, IRF3 with CD8+ T cell and their prognostic significance in upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:7725–7735. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S222422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bejarano L, Jordāo MJC, Joyce JA. Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 2021;11(4):933–959. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soria F, Shariat SF, Lerner SP, et al. Epidemiology, diagnosis, preoperative evaluation and prognostic assessment of upper-tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC). World J Urol. 2017;35(3):379–387. doi: 10.1007/S00345-016-1928-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts JL, Ghali F, Aganovic L, et al. Diagnosis, management, and follow-up of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: An interdisciplinary collaboration between urology and radiology. Abdom Radiol (New York). 2019;44(12):3893–3905. doi: 10.1007/S00261-019-02293-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voskuilen CS, Schweitzer D, Jensen JB, et al. Diagnostic value of 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with computed tomography for lymph node staging in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol Oncol. 2020;3(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/J.EUO.2019.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fojecki G, Magnusson A, Traxer O, et al. Consultation on UTUC, Stockholm 2018 aspects of diagnosis of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. World J Urol. 2019;37(11):2271–2278. doi: 10.1007/S00345-019-02732-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leow JJ, Liu Z, Tan TW, Lee YM, Yeo EK, Chong YL. Optimal management of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: Current perspectives. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:1–15. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S225301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shvero A, Hubosky SG. Management of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022;24(5):611–619. doi: 10.1007/S11912-021-01179-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giudici N, Bonne F, Blarer J, Minoli M, Krentel F, Seiler R. Characteristics of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma in the context of bladder cancer: A narrative review. Transl Androl Urol. 2021;10(10):4036–4050. doi: 10.21037/TAU-20-1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lucca I, Klatte T, Rouprêt M, Shariat SF. Kidney-sparing surgery for upper tract urothelial cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2015;25(2):100–104. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grande M, Campobasso D, Inzillo R, et al. The use of endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery as an additional approach to upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: Our experience. Indian J Urol. 2021;37(2):187. doi: 10.4103/IJU.IJU_71_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ni S, Tao W, Chen Q, et al. Laparoscopic versus open nephroureterectomy for the treatment of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma: A systematic review and cumulative analysis of comparative studies. Eur Urol. 2012;61(6):1142–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Linehan J, Schoenberg M, Seltzer E, Thacker K, Smith AB. Complications associated with ureteroscopic management of upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Urology. 2021;147:87–95. doi: 10.1016/J.UROLOGY.2020.09.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muilwijk T, Akand M, van der Aa F, et al. Metastasectomy of oligometastatic urothelial cancer: A single-center experience. Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9(3):1296–1305. doi: 10.21037/TAU-19-624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martini A, Daza J, Poltiyelova E, et al. Pathological downstaging as a novel endpoint for the development of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma. BJU Int. 2019;124(4):665–671. doi: 10.1111/BJU.14719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matin SF, Margulis V, Kamat A, et al. Incidence of downstaging and complete remission after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high-risk upper tract transitional cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116(13):3127–3134. doi: 10.1002/CNCR.25050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liao RS, Gupta M, Schwen ZR, et al. Comparison of pathological stage in patients treated with and without neoadjuvant chemotherapy for high risk upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2018;200(1):68–73. doi: 10.1016/J.JURO.2017.12.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meng X, Chao B, Vijay V, et al. High response rates to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in high-grade upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Urology. 2019;129:146–152. doi: 10.1016/J.UROLOGY.2019.01.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Almassi N, Gao T, Lee B, et al. Impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on pathologic response in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma undergoing extirpative surgery. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16(6):e1237–e1242. doi: 10.1016/J.CLGC.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kubota Y, Hatakeyama S, Tanaka T, et al. Oncological outcomes of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced upper tract urothelial carcinoma: A multicenter study. Oncotarget. 2017;8(60):101500–101508. doi: 10.18632/ONCOTARGET.21551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hosogoe S, Hatakeyama S, Kusaka A, et al. Platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves oncological outcomes in patients with locally advanced upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4(6):946–953. doi: 10.1016/J.EUF.2017.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Porten S, Siefker-Radtke AO, Xiao L, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy improves survival of patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Cancer. 2014;120(12):1794–1799. doi: 10.1002/CNCR.28655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Margulis V, Puligandla M, Trabulsi EJ, et al. Phase II trial of neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy followed by extirpative surgery in patients with high grade upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2020;203(4):690–698. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Siefker-Radtke AO, Dinney CP, Shen Y, et al. A phase II clinical trial of sequential neoadjuvant chemotherapy with ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and gemcitabine, followed by cisplatin, gemcitabine, and ifosfamide in locally advanced urothelial cancer: Final results. Cancer. 2013;119(3):540–547. doi: 10.1002/CNCR.27751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoffman-Censits JH, Trabulsi EJ, Chen DYT, et al. Neoadjuvant accelerated methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (AMVAC) in patients with high-grade upper-tract urothelial carcinoma. https://doi.org/101200/jco2014324_suppl326. 2014;32(4_suppl):326–326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.32.4_SUPPL.326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McConkey DJ, Choi W, Shen Y, et al. A prognostic gene expression signature in the molecular classification of chemotherapy-naïve urothelial cancer is predictive of clinical outcomes from neoadjuvant chemotherapy: A phase 2 trial of dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin with bevacizumab in urothelial cancer. Eur Urol. 2016;69(5):855. doi: 10.1016/J.EURURO.2015.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coleman* JA, Wong NC, Sjoberg DD, et al. LBA-17 multicenter prospective phase II clinical trial of gemcitabine and cisplatin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with high-grade upper tract urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2019;201(Supplement 4). doi: 10.1097/01.JU.0000557509.30958.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bajorin DF, Witjes JA, Gschwend JE, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus placebo in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(22):2102–2114. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA2034442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.ASCO GU 2021: Updated Outcomes of POUT: A Phase III Randomized Trial of Peri-Operative Chemotherapy Versus Surveillance in Upper Tract Urothelial Cancer. https://www.urotoday.com/conference-highlights/asco-gu-2021/bladder-cancer/127914-asco-gu-2021-updated-outcomes-of-pout-a-phase-iii-randomized-trial-of-peri-operative-chemotherapy-versus-surveillance-in-upper-tract-urothelial-cancer.html. Accessed September 8, 2022.

- 68.Galsky M, Witjes JA, Gschwend JE, et al. PD10-01 Disease-free survival with longer follow-up from the checkmate 274 trial of adjuvant nivolumab in patients after surgery for high-risk muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 2022;207(Supplement 5). doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000002536.01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bellmunt J, Hussain M, Gschwend JE, et al. Adjuvant atezolizumab versus observation in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor010): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(4):525–537. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00004-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Powles T, Assaf ZJ, Davarpanah N, et al. ctDNA guiding adjuvant immunotherapy in urothelial carcinoma. Nature. 2021;595(7867):432–437. doi: 10.1038/S41586-021-03642-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaag MG, O’Malley RL, O’Malley P, et al. Changes in renal function following nephroureterectomy may affect the use of perioperative chemotherapy. Eur Urol. 2010;58(4):581–587. doi: 10.1016/J.EURURO.2010.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lane BR, Smith AK, Larson BT, et al. Chronic kidney disease after nephroureterectomy for upper tract urothelial carcinoma and implications for the administration of perioperative chemotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116(12):2967–2973. doi: 10.1002/CNCR.25043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim MS, Koom WS, Cho JH, Kim SY, Lee IJ. Optimal management of recurrent and metastatic upper tract urothelial carcinoma: Implications of intensity modulated radiation therapy. Radiat Oncol. 2022;17(1). doi: 10.1186/S13014-022-02020-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu MZ, Gao XS, Bin QS, et al. Radiation therapy for nonmetastatic medically inoperable upper-tract urothelial carcinoma. Transl Androl Urol. 2021;10(7):2929–2937. doi: 10.21037/tau-21-291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moschini M, Shariat SF, Rouprêt M, et al. Impact of primary tumor location on survival from the European organization for the research and treatment of cancer advanced urothelial cancer studies. J Urol. 2018;199(5):1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/J.JURO.2017.11.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen WK, Wu ZG, Xiao YB, et al. Prognostic value of site-specific metastases and therapeutic roles of surgery and chemotherapy for patients with metastatic renal pelvis cancer: A SEER Based Study. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2021;20. doi: 10.1177/15330338211004914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Loehrer PJ, Einhorn LH, Elson PJ, et al. A randomized comparison of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(7):1066–1073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.7.1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Von Der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(21):4602–4608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.De Santis M, Bellmunt J, Mead G, et al. Randomized phase II/III trial assessing gemcitabine/carboplatin and methotrexate/carboplatin/vinblastine in patients with advanced urothelial cancer who are unfit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy: EORTC study 30986. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(2):191–199. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.3571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Necchi A, Pond GR, Raggi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of gemcitabine plus either taxane or carboplatin in the first-line setting of metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15(1):23–30.e2. doi: 10.1016/J.CLGC.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bellmunt J, Théodore C, Demkov T, et al. Phase III trial of vinflunine plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone after a platinum-containing regimen in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(27):4454–4461. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Balar AV, Galsky MD, Rosenberg JE, et al. Atezolizumab as first-line treatment in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2017;389(10064):67–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32455-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Galsky MD, Arija JÁA, Bamias A, et al. Atezolizumab with or without chemotherapy in metastatic urothelial cancer (IMvigor130): A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2020;395(10236):1547–1557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30230-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Balar A V, Castellano D, O’Donnell PH, et al. First-line pembrolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with locally advanced and unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer (KEYNOTE-052): A multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(11):1483–1492. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30616-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Powles T, Park SH, Voog E, et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(13):1218–1230. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA2002788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: A single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2016;387(10031):1909–1920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00561-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Powles T, Durán I, van der Heijden MS, et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2018;391(10122):748–757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33297-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sternberg CN, Loriot Y, James N, et al. Primary results from SAUL, a multinational single-arm safety study of atezolizumab therapy for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial or nonurothelial carcinoma of the urinary tract. Eur Urol. 2019;76(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/J.EURURO.2019.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]