Abstract

Equity remains poorly conceptualised in current nutrition frameworks and policy approaches. We draw on existing literatures to present a novel Nutrition Equity Framework (NEF) that can be used to identify priorities for nutrition research and action.

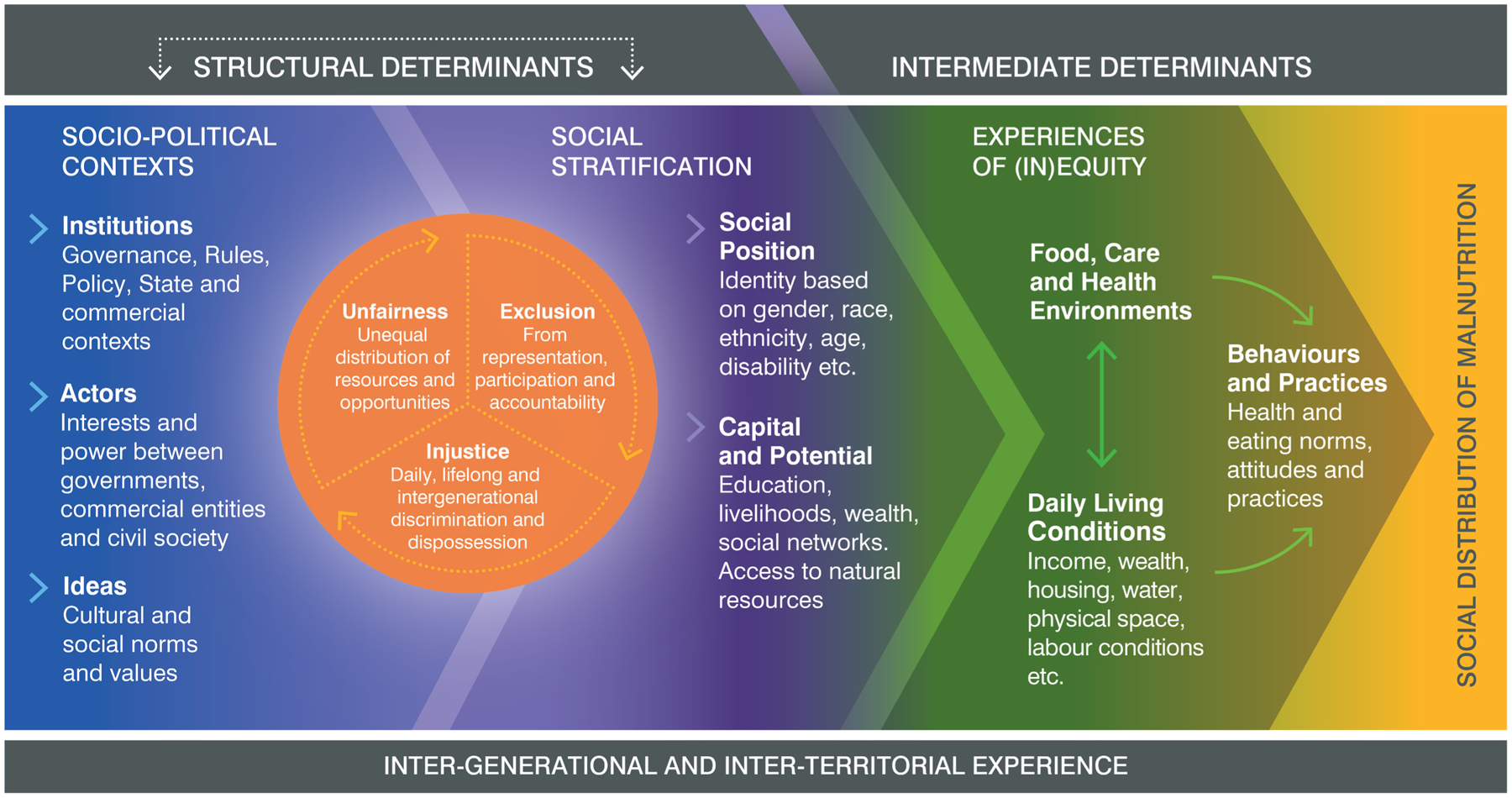

The framework illustrates how social and political processes structure the food, health and care environments most important to nutrition. Central to the framework are processes of unfairness, injustice and exclusion as the engine of nutrition inequity across place, time and generations, ultimately influencing both nutritional status and people’s space to act.

The NEF illustrates conceptually how action on the socio-political determinants of nutrition is the most fundamental and sustainable way of improving nutrition equity for everyone everywhere, through ‘equity-sensitive nutrition’. Efforts must ensure, in the words of the Sustainable Development Goals, that not only is “no one left behind” but also that the inequities and injustices we describe do not hold anyone back from realising their right to healthy diets and good nutrition.

Keywords: Nutrition, Equity, Social determinants, Framework, Review

1. Introduction

The global distribution of malnutrition is remarkably unequal (Development Initiatives, 2020). The number of stunted children remains very high, at an estimated 149 million, with 9 out of 10 of all stunted children living in Africa and Asia (UNICEF, WHO, World Bank, 2020). Worldwide, 820 million people are chronically undernourished (i.e. experiencing hunger), with the total number rising since 2015, especially in Africa, West Asia and Latin America (FAO 2019). The prevalence of overweight and obesity is high in many high-income countries and rates are rapidly escalating in low and middle-income countries.1 The majority of countries for whom we have data are experiencing double or triple burdens of malnutrition.

Rates of malnutrition are also starkly unequal between population groups within countries. There are important differences between those from richer or poorer households, those with higher or lower educational attainment, women and men, or between urban and rural areas (Development Initiatives, 2020). Evidence points to notable differences in outcomes for those with different forms of disability, or those from non-majority religions, ethnicities, genders and sexualities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015; Finegold et al., 2009; Harris et al., 2021b; Kite et al., 2014; Love et al., 2019; Mesenburg et al., 2018; Perez-Escamilla et al., 2018).

These measurable inequalities in malnutrition outcomes point to the inequitable and unjust distribution of malnutrition: a comprehensible and avoidable situation of inequity holding certain people back from healthy foods and diets, and other factors that ensure their proper nourishment. These inequities within and between countries reflect rapid transitions in food systems, and the wider social, economic, commercial and political systems that drive the production, distribution, marketing and consumption of food. Subsequently, food environments are highly unequal, including people’s physical access, affordability, exposure to advertising and promotion, and quality of food (Development Initiatives, 2020).

International research on nutrition has not engaged substantively with agendas on equity, and (in)equity itself remains poorly conceptualised in current frameworks and policy approaches. There is no doubt that transformational shifts are needed to existing food systems and food environments to better support healthy, nutritious diets, for everyone. But equity in diets and nutrition will never be achieved unless action within the food system is combined with actions outside of the food system, which address the deeply rooted socio-political drivers of health and nutrition inequities. Addressing nutrition inequities ultimately requires addressing power imbalances, by holding the powerful to account, and foregrounding the interests and voices of those who are marginalised and excluded(Walls et al., 2020). In this paper we establish how existing literatures – in health equity, development studies, and ethics more broadly – can help better understand the fundamental drivers of the social distribution of malnutrition through the lens of equity.

1.1. Purpose of this paper

We ask “what are the structures and processes that drive global and within-country inequities in nutrition, and what are the implications for policy, practice and research?“. Towards this aim, we review a variety of literatures highlighting the relationships between inequalities in nutrition outcomes, and individual, social, political, commercial, cultural and economic factors structuring inequity, historically and currently. Missing from the nutrition literature is an integrated framework that helps to understand the interconnections between these factors, drawing on theory and evidence of inequity from across disciplines. We present such a framework in this paper, the Nutrition Equity Framework (NEF), which we envisage will be suitable for guiding understanding and action to address inequities in malnutrition in all its forms.

1.2. Approach

The Nutrition Equity Framework (NEF) brings together existing frameworks and theories that have been used separately to understand equity in health, in development, and in various forms of malnutrition. We focus on equity rather than equality (Harris and Nisbett, 2018) because this foregrounds the drivers and processes which lead to unequal nutrition outcomes.

We combined a critical narrative review of the literature (Grant and Booth, 2009; Greenhalgh et al., 2018) with a process of framework development via an iteration of the frameworks deemed the ‘best fit’ (Booth and Carroll, 2015). This involved drawing on academic and grey literature (across the fields of health equity, development studies, and ethics more broadly) retrieved from three prior reviews conducted by members of the authorship team (Harris and Nisbett, 2018; Harris et al., 2021b; Salm et al., 2020).2 An additional electronic library search was undertaken for the term ‘nutrition AND equity AND framework’ and all papers which reported on a framework were considered for inclusion. Key theories were identified from this literature, followed by a targeted search and identification of additional frameworks that addressed these theories.

Two key frameworks were identified as an initial ‘best fit’ (Booth and Carroll, 2015) and were modified to include other relevant framework components drawn from our reading of the associated literature. A further description of the chosen frameworks and the broader literature base is provided as the first section of the results. All framework components were then used to produce a narrative summary of the literature.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we review existing theories and conceptual frameworks that we identified as relevant to the paper aims. Second, drawing on this, we summarise how we define and frame the concept of equity. Third, we introduce the Nutrition Equity Framework, and outline its principal components. Finally, we discuss what this means for research and action going forward, with reference to broader literatures on these themes.

1.2.1. Methodological strengths and limitations

Notable advantages and limitations based on the set of methods used are that a critical narrative review relies on the subjective interpretation by the authors and their knowledge of a field of work to consider what kinds of themes to include or exclude, and in our case what framework to build on (Grant and Booth, 2009:97). In addition to the structured searches, authors were invited to contribute additional material, in line with the critical interpretive review methodology, where considered relevant or where there were perceived gaps in the review yield in relation to new post-hoc themes that were discovered a part of the analysis.3 This is one of the stated advantages of a narrative or ‘expert’ review methodology over more ‘systematic’ methods (Greenhalgh et al., 2018).

Counter to these claims of ‘expertise’, the positionality of the authorship as speaking from positions of relative academic and other forms of privilege, requires acknowledgement. Our positionality as health equity, public health and development scholars informs our framework and our framing of nutrition equity. Early versions of the framework were reviewed by the International Expert Group of the Global Nutrition Report (GNR), which includes both academics and practitioners. Our authorship was then expanded in the writing process of this paper to include expertise on Indigenous health and food systems (VBJ), which hadn’t been represented in the GNR process. But this process still includes gaps in perspectives and expertise from many different communities affected by malnutrition not represented amongst our authorship and we acknowledge this as a weakness of our review to be addressed in future work, having begun the conversation on equity in research amongst our professional community.

Acknowledging these gaps, we also stress the importance of understanding the material effects that different framings of inequity and inequality actually have, as well as their unintended consequences. For example, a ‘deficit discourse’ can result in framing target groups as deficient, lacking or as failures, thereby perpetuating further discrimination and marginalization. Such discourse, for example, harmfully framed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia as irresponsible and incompetent at managing their health, with an underlying frame of ‘otherness’ (Aldrich et al., 2007). Similarly, while we draw on the work that has taken place under the Sustainable Development Goals’ slogan of ‘leave no-one behind’, our analysis questions the understandings that ‘being left behind’ are somehow the result of benign neglect on the part of national governments and international policy. On the contrary, we refer to multiple instances where structural injustice and exclusion, including via historical processes such as colonialism, have led to people(s) being systematically ‘held back’ from fully realising their agency and sovereignty over their own nutrition.

2. Framework development

2.1. Frameworks and theories relevant to nutrition equity

We found that two key public health frameworks best informed the backbone of the NEF: one on the social determinants of health (WHO, 2008); and one on the causes of malnutrition (UNICEF, 1990). The NEF was refined iteratively as we considered the broader frameworks and theories outlined in Table 1, which we identified in our search process.

Table 1.

Existing conceptual and theoretical frameworks that are relevant for nutrition equity.

| Author(s) | Discipline | Geographical focus | Framework/theory | Description | How this adds to understanding of nutrition equity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backholer et al., (2014) | Public health/health equity | Global | Framework for the likely impact of obesity prevention strategies on socioeconomic inequalities in population weight | Considers the role agency-structure theory for understanding the likely impact of population-level obesity prevention interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in health. Highlights that interventions that rely heavily on individual agency are more likely to increase socioeconomic inequalities in weight, whereas interventions that make structural changes to support healthy eating are less likely to do so. | Underlines importance of understanding assumptions behind degrees of agency; or structural change required; in different settings for obesity intervention. |

| Cadieux & Slocum, (2015) | Sociology/Geography/Critical food studies | Global South, US and Canada | Food Justice | Provides an introduction to food justice and comparison with allied concepts of food sovereignty, whilst critiquing analysis centred on mainstream paradigms of food security. Roots food justice in transformational practice, derived through examining gender, race, class and capitalist relations as experienced in wider processes of equity/trauma; exchange; land and labour. | Inequity as structural injustice is central to food justice approaches and is something we have adopted here to strengthen mainstream analysis, which often focuses only on income disparities, without always questioning how these might originate. |

| (Friel et al., 2007) (Friel and Ford, 2015) Friel and Ford (2015), (Friel et al., 2017) | Health equity | Global | Social and systemic determinants of obesity and health eating | Food and health inequities as based on broader social determinants, including: social stratification based on race, ethnicity, sex, age, lack of decent housing, work, welfare, inequities in access to natural and build environments. Systems science as a way of bringing stakeholders together to derive shared understandings of systemic drivers of unhealthy food. | Demonstrates how inequities in food and health eating are the sum of a number of different sub-systems which are part of people’s everyday living conditions. Links such conditions to clear policy choices and policy failures. |

| Food Ethics Council, (2020) | NGO and multilateral literature | UK (but with global links) | The Fairness Framework | Based on considerations of “whether all have enough, while avoiding some having too much (“fair share”); “all are protected and have the same chances, supported by an enabling environment (“fair play”); all are free to make their own decisions about food and have sufficient voice e. g. in public decision making (“fair say”) | Complementary to our work and has similarities to the tripartite framing (Karllson et al.) that we adapt as fairness (fair share), justice (fair play) and inclusion (fair say). |

| Hankivsky et al., (2014) | Health Equity | Canada | Intersectionality based policy analysis framework | Prioritises the complexity of human life, drawing on socially constructed categories such as race/ethnicity, gender and class; shaping historically and spatially contingent identities and experiences … leads to a set of questions on how problems are constructed, represented by and for different groups and how more transformative interventions can be produced via such analysis. | Important for demonstrating how key social science concepts, “[r]ooted in a long and deep history of Black feminist writing, Indigenous feminism, third world feminism, and queer and postcolonial theory” (p2) can be brought squarely into health policy analysis. |

| Herman et al., (2014) | Community health | USA & global | Life course perspective | Emphasises experience over the lifetime end widens environmental exposures to include social and biological characteristics: exposure to these different environments influences nutrition over the lifetime and is part of the production of intergenerational differences between groups. | A reminder that nutrition inequity is experienced as and derived from a set of experiences, environments and exposures that are neither purely biological nor purely social, but a combination of the two, which iterate over a lifetime and over generations (see also Nisbett 2019). |

| Harris & Nsbett, (2020) | Public health/Development Studies | Global | Basic determinants of malnutrition: Resources, Structures, Ideas and Power | Updates the classic UNICEF (1990) Framework to focus on basic determinants - including imbalances in different human and natural resources; ideas, institutions and other forms of structural power. Draws on Harris and Nisbett (2018) which also draws from social science and health equity literature to develop these concepts | Emphasises factors classically ‘black-boxed’ in nutrition frameworks and draws on classic social science and political economy considerations of the link between ideas, institutions and resources. |

| Karlsson et al. (2018), Nichols (2020); Salm et al. (2020) | Development studies/sustainable development | Global (mostly global south) | ‘Tripartite’ understanding of distributional, recognition and procedural justice. | Equity as based on distributional justice (of power, resources, opportunities and impacts of policy); on recognition justice - i.e of different forms of everyday and historical injustice; and on procedural justice, i.e. fair process/fair participation in process. Draws on both liberal Rawlsian (distributional, procedural) and feminist philosophy of justice and equity, the latter influenced by Nancy Fraser. | Moves beyond overly simplistic definitions of equity as ‘fairness’ - particularly in relation to historical and ideological injustices such as racism and patriarchy. We adapt this in understanding micro- and macro- processes of power, labelled as unfairness; injustice and exclusion |

| (Madureira Lima and Galea, 2018)) | Public health/Sociology | Global | Corporate practices and health | Describes the key mechanisms through which corporations exert their influence on health: influencing the political environment, preference shaping, the knowledge environment; the legal environment and the extra-legal environment. | Ultimately these corporate actions penetrate the social, cultural and political determinants of malnutrition. Underscores the importance of addressing corporate actions and power to address inequities in malnutrition. |

| (Marmot et al., 2008; WHO, 2008) | Health equity | Global | WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health/Addressing health equity | Locates the root causes of ill health in broader failings in social and political systems; the unequal distribution of money, other resources and political power. The ‘social gradient’ in experiencing health inequity (including greater vulnerability and exposure to health damaging factors) means that all people are affected by their place in the social hierarchy, not only those at the bottom. | Highly influential in highlighting how population health problems can be traced to broader social, economic and political determinants and social position … but also that such problems are remediable and not immutable. |

| Odom et al. (2019) | Public health | Hawaii, USA | Pilinahā: An Indigenous Framework for Health | Framework derived from shared accounts of Indigenous community members in Kalihi, Honolulu, stressing “the 4 vital connections that people typically seek to feel whole and healthy in their lives: connections to place, community, past and future, and one’s better self.” (p32 | An alternative to individualised conceptions of health and health behaviours - health is here theorised as distributed or community-wide, based in a strong community identity, and rooted in place and territory. |

| Perez-Escamilla et al., (2018) | Public health | Global | Nutrition disparities and the global burden of malnutrition | Maps socio and demographic, behavioural, biological and environmental drivers of nutrition disparities across the lifecourse. Emphasis on socio-economic disadvantage and factors working across the generations. | Highlights disparities across all different forms of malnutrition and across low, middle and high income countries. Emphasises nutrition outcomes as not only linked to income, race/ethnicity, but also multiple social determinants coming together and building up over lifetimes. |

| (S. Kumanyika, 2017; S. K. Kumanyika, 2019) | Health equity | USA | Equity Oriented Obesity Prevention Framework | Considers socio-economic and physical/food environment factors; and factors amenable to policy and systems change; as well as individual and community capacity. Highlights discrimination and social exclusion | Importance of understanding different factors (physical, sociocultural, economic, policy/political) in operation at both micro- and macro-levels. Emphasises capacity and agency of communities as central to intervention. |

| UNICEF (1990) | NGO and multilateral literature | Global | Strategy for Improving Nutrition of Children and Women in Developing Countries. Causes of Malnutrition and Death | Describes basic, underlying and Immediate causes of child and maternal malnutrition and malnutrition related deaths. Identifies, at an immediate level, the interaction of dietary intake and health status; at an underlying level, household food security, care for women and children, and health service and a healthy environment; and at a basic level, the political economy of potential resources and their control. | The classic public health framework for understanding the broader causes of malnutrition. |

| (Woods, Williams, Baker, Nagarajan, Sacks, 2021) | Public health | Global | The influence of corporate market power on health: exploring the structure-conduct-performance model from a public health perspective | Considers the public health impacts of highly concentrated (e.g. oligopolistic) market structures, including the use of anti-competitive market strategies by transnational food corporations, and the ways in which corporate and market power mediates the distribution and allocation of resources via market systems in society. Market concentration provides corporations with considerable structural and relational power over governments, including through their ability to control and move large amounts of capital investments across borders, which is enhanced under neoliberal globalization. | Helps to understand and redress nutrition inequities as relating to the considerable market power of transnational ultra-processed food corporations, and identifies a broader set of government policy actions (e.g. anti-trust, industrial, financial and trade and investment policies) that reduce market concentration and related instances of market failure. Guides understanding of how asymmetries in political and economic power can be addressed within food systems. |

The identified literature (Table 1) derives from multiple fields, from public health to sociology to geography to development studies, with a focus on equity in both low- and high-income country contexts. The literature provided multiple insights and entry-points for refining the original combined framework, bringing in ideas of the interplay of structure and agency in equity; how social, political and commercial sub-systems shape equity structures; how broader ethical issues of fairness, justice and inclusion shape experiences of equity; how each of these aspects is rooted in contextualised and historical socio-political and power-related processes; and how research (from various disciplines) and activism can interact to address inequity.

To the initial frameworks we therefore connected wider understandings of equity drawn from these literatures and influenced by feminist and intersectional theory and related work on food justice, politics and sovereignty (Cadieux and Slocum, 2015; Karlsson et al., 2018; Leach et al., 2020; Nichols, 2020; Salm et al., 2020). In defining malnutrition we also draw on recent work which considers the common drivers of malnutrition in all its forms (Scrinis, 2020), rather than focus in a siloed manner on different forms of undernutrition such as micronutrient deficiencies, or dietary related non communicable diseases (Hawkes et al., 2020; Popkin et al., 2020; Scrinis, 2020). These ideas generated a draft Nutrition Equity Framework that was subsequently discussed, critiqued and refined by the entire authorship.

3. Defining and framing nutrition equity

3.1. The Nutrition Equity Framework

Fig. 1 presents the Nutrition Equity Framework. In summary, moving left to right on the diagram, the framework begins with the broad structural determinants and interactions of nutrition inequity, through socio-political contexts and social stratification, linked by an ‘engine of inequity’ comprising unfairness, injustice and exclusion. The intermediate determinants of malnutrition are on the right side of the diagram and depict the way in which structural causes are experienced in everyday conditions and environments. In the description that follows, we devote more focus to the processes that are covered within the structural, left-hand side, given that this is the main focus of our work: the right-hand side intermediate determinants have generally been a stronger focus of existing nutrition literature (further definitions of the intermediate determinants are provided in online supplementary materials 1). Throughout, we emphasise the dynamics and feedback loops that are inherent between the different parts of the framework: it is these interactions, rather than the individual components, that are most critical for understanding the structural inequities causing malnutrition.

Fig. 1. The Nutrition Equity Framework.

[see separate file].

3.1.1. Structural determinants

3.1.1.1. Socio-political contexts.

Socio-political context is a combination of shared societal ideas, social and cultural norms and values; and the broader socio-economic and political institutions which both arise from and shape them (forms of governance, other formal and informal rules, market and exchange systems) and which also shape ideas. These are in-turn influenced by distributions of power, money and resources between different actors and interests, including governments, corporate entities, civil society groups and citizens.

Of core ideas shaping food systems and nutrition, neoliberalism remains a foundational ideology in most of the world today, crystalising into institutions emphasising market freedom, minimal government intervention, devolved governance, and an expanded role for the private sector in all spheres of political, economic and social activity (Baker et al., 2018). Neoliberal systems and norms have obstructed equitable nutrition policy action in several ways. The preferencing of vested commercial interests in nutrition governance and policy decision-making has obstructed the regulation of harmful commercial activities, negatively influenced existing food environments and food systems (e.g through predatory marketing) also emphasised behavioural-lifestyle approaches to nutrition that devolve responsibility to individuals (Baker et al., 2017; Guthman and DuPuis, 2006; Phillips et al., 2021).

Closely associated with neoliberalism, ‘nutritionism’ is a curative, biomedical or nutrient-centric view of nutrition, emphasising reductionist interventions to the neglect of integrated, preventative or food systems-wide approaches (Clapp and Scrinis, 2017; Scrinis, 2013). Through these processes, nutrition governance and policy processes can become depoliticised and disconnected from the values, perspectives or interests of marginalised groups (Hoey and Pelletier, 2011; Pelletier et al., 2012) or conflate malnutrition with lack of staple food production to the neglect of other (nutrition and equity) objectives (Carey et al., 2016; De Schutter, 2014; te Lintelo and Lakshman, 2015).

Other dominant social norms and ideas of relevance include patriarchy and racism. Patriarchy centers power in the hands of men and is based on assumptions of gendered roles and heterosexual norms in micro- (family, kin) and macro- (community, political) settings, sex, reproduction and caring, sexuality, access to knowledge, education, livelihoods, freedom of movement and expression (Beechey, 1979). Multiple effects are seen on nutrition, including defining household roles and care roles, access to nutritious food, the medicalisation of pregnancy, birth and infant feeding, the distribution of resources, including land, freedom to access public services, and the design and implementation of public services (Van den Bold et al., 2013). Racism assigns values and social and economic opportunities based on assumptions related to race, ethnicity, caste, variations in skin colour and (assumed) hereditary characteristics (Ndumbe-Eyoh, 2020). Racism is strongly linked to colonialism, particularly privileging white Europeans and their descendants in settler/colonial communities, and used to justify poorer outcomes for those not of elite status (box 1) without questioning underlying privilege of those elites in all aspects of access to resources, opportunities and political power (Griffiths et al., 2016; Marmot, 2018; Mowbray, 2007; Ndumbe-Eyoh, 2020).

Box 1. Nutrition Equity from an Indigenous Perspective.

Source: Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Public Health, Valarie Blue Bird Jernigan (In process)

Indigenous concepts of food, nutrition, health, wellness are often distinctly different from Western notions (Browne et al., 2020; Jernigan and Haring, 2019). For example, for many Indigenous peoples in North America food is considered a sacred gift, and animals and plants are seen as relatives. As such, Indigenous peoples not only have rights to healthy and traditional foods and clean water but relational responsibilities to care for the land that provides this gift. Colonization, recognised by the World Health Organization as a social determinant of health (Mowbray, 2007), disrupted the food systems for many Indigenous peoples, forcibly removing them from their traditional homelands to often unfamiliar and barren reservation lands. Indigenous reservations, most of which are rural, have been the target of environmental destruction and degradation (Dhillon and Young, 2010) and are more likely than urban settler-concentrated areas to bear the burden of climate change(Ford, 2012). National policies aimed to reduce or eliminate racial/ethnic health disparities may not impact Indigenous peoples if they are not applicable on Indigenous lands and can even exacerbate disparities, as is the case of tobacco regulations in the United States (Brokenleg et al., 2014; Hafez et al., 2019). Further, these policies are based on Western notions of health and health equity and don’t account for Indigenous relational concepts of health. Thus, even political inclusion of Indigenous people is an insufficient solution to promote nutrition equity when the system is a colonialized system. Indigenous food sovereignty, the right and responsibility of Indigenous people to healthy and culturally appropriate foods produced through traditional Indigenous practices (Grey and Patel, 2015; Jernigan, 2012a; Settee, 2020) has emerged as one important strategy to support Indigenous communities in taking greater control over their land and food systems by increasing and protecting traditional and healthy foods and reducing dependence on packaged and fast foods. Indigenous food sovereignty mirrors public health efforts to address nutrition-related disparities through food system change in non-Indigenous populations (Story et al., 2009), and addresses the urgent need for nutrition equity approaches that are embedded within an Indigenous concept of health and wellness and self-determination (Walters et al., 2020). An equity-focused nutrition framework that focuses on improved food security and healthy foods access alone is insufficient. An equity focused framework must recognise and create space for Indigenous sovereignty, culturally appropriate approaches to health, and the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples to determine how their lands are used.

Institutions and ideas combine to privilege the views of particular dominant actors, creating and reinforcing power imbalances via rules and norms at multiple levels, from invisible assumptions which may dictate what happens within a family, to the ‘hidden’ power of large private sector actors to counter regulatory threats within food system, trade and health policy decision-making spaces, including by private companies (Baker et al., 2020b; Milsom et al., 2020). The interests of different groups also intersect with their control over ideas and institutions in setting the rules for market governance, including the extent to which the food sector is regulated or encouraged to self-regulate to improve population diets (Clapp and Scrinis, 2017).

Such ‘commercial determinants’ of nutrition (Mialon, 2020) are also an increasingly important part of the interaction between socio-economic and political contexts, social position, and material resources, demonstrated in the links between marketing of unhealthy foods, disproportionately targeted at minority communities (Backholer et al., 2021). In addition to marketing to consumers, private corporations use a number of market and political techniques to shape institutions and promote ideas conducive to growing and sustaining their markets (Baker et al., 2020b). For example, institutions are often shaped by corporate lobbying, threats of litigation and through the promotion of self-regulation in-place of regulation by the state. Ideas are also powerfully shaped through branding and product marketing, corporate social responsibility initiatives that promote a favourable public image, and through funding scientific research that favours corporate interests and undermines opponents (Mialon, 2020).The rise of public-private partnerships in food and nutrition governance can also privilege these powerful commercial interests in shaping policy agendas in ways that perpetuate (rather than attenuate) unhealthy food markets (Baker et al., 2020a; Clapp and Scrinis, 2017).

The framework therefore depicts socio-political contexts driving not only the stratification of society into different groups based on identity and resources, but also the intermediate level factors of food, health and care environments.

3.1.1.2. Social stratification.

Premised on these ideologies and the actors and institutions whose power is maintained, social stratification includes the way in which people are separated or ascribed more or less powerful positions in society according to, for example, gender, age, sexuality, racialized identities and ethnicities, occupation or relative wealth. This can result from a combination of individual and groups’ perceived social position and the personal and material resources they have available to them in terms of education, livelihood opportunities and social networks – their capital and potential. These resources can include economic, capital, such as land or money; natural capital such as control over natural resources such as fishing, water or mining rights (Ericksen, 2008); social capital through access to networks of relatives or community; and cultural capital via education and other forms of cultural know-how (Bourdieu, 1984).

3.1.2. Intermediate determinants: experiences of inequity

At intermediate levels, nutrition inequity is determined by this interaction of daily living conditions, health and eating behaviours, and access to adequate or optimal food, health, care environments (See Supplementary Materials 1 for further definition and explanation, and: Bhutta et al., 2013; Friel and Ford, 2015; Friel et al., 2017; Hankivsky et al., 2014; Marmot et al., 2008; L. C. Smith and Haddad, 2015; B. Swinburn, Egger and Raza, 1999; B. A. Swinburn et al., 2019; UNICEF, 1990; WHO, 2008).

In Fig. 1 we illustrate a circular relationship between daily living conditions, food health and care environments, and behaviour and practices. For example, socialised (learned) behaviours around health seeking or food choice are influenced by exposure to different types of food or health environments (Friel et al., 2017), which in turn are shaped by socio-political and commercial contexts.

Socio-political context and social stratification, interacting through processes of unfairness, injustice and exclusion, shape intermediate determinants of nutrition equity in key ways. Daily living conditions such as wealth, housing and labour influence people’s everyday experiences, preferences and behaviours around food and nutrition, from whether children are breastfed, to food tastes, to the food available to different members of the family (Aurino, 2017; Dixon-Woods et al., 2006; Friel and Ford, 2015; Kroeger, 1983; Mackian et al., 2004; Marmot et al., 2008; Messer, 1984; L. C. Smith and Haddad, 2015; Watson and Caldwell, 2005). Human and material capital and potential shape daily living conditions and access to essential services (including, in many parts of the world, paid education, health, sanitation, water), which are strong predictors of nutritional status (Bhutta et al., 2013; Black and Dewey, 2014; Downs et al., 2020; Headey et al., 2017; Turner et al., 2018; Victora et al., 2016).

3.1.3. The engine of inequity at a structural level: unfairness, injustice and exclusion

Most political economy frameworks in health and nutrition will make the connection between socio-political context and intermediate determinants (Baker et al., 2018; Nisbett et al., 2014), but in the NEF we pay particular attention to why particular groups are affected so inequitably from structural to intermediate levels. Fuelled by socio-political contexts and driving both social stratification and the way stratified groups experience determinants at the intermediate level is the ‘engine’ of inequity, which perpetuates dominant structures in determining the social distribution of malnutrition.

In an equitable society, differing social positions and identities – for example, coming from a minority ethnicity, skin colour, gender or sexual identity, being disabled or from a recent migrant background – would not affect human capital and potential. All people would be able to influence the development of norms and institutions, which then guide the distributions of societal resources and opportunities, such as access to education or land. In reality, it is the interactions between these different positions and identities that are the engine of inequity at the core of the NEF. To simplify the multiple interactions which occur between these structural factors, we employ the notions of social injustice, distributional unfairness and social and political exclusion which are adapted from the wider literature on equity and justice (Karlsson et al., 2018; McDermott et al., 2013; Nichols, 2020).

Social injustice begins with discrimination against individuals and groups because of social norms and cultural values which treat them as unequal, unwanted or stigmatised. Often these forms of discrimination intersect – racism, for example, is often experienced through the prism of sexism, and vice-versa (Hankivsky et al., 2014; Kabeer, 2005, 2010). Increasingly, nutritional status itself can become a form of such stigma, such as the growing level of discrimination faced by people labelled as fat or obese (O’Hara and Taylor, 2018). Social and policy failure to recognise multiple forms of such discrimination is a way in which inequities are perpetuated (UNDP, 2018) and institutionalised (Macpherson, 1999; Ndumbe-Eyoh, 2020). The resulting social position (e.g. the social assumptions that are called to mind when people imagine ‘a disabled boy’, ‘a low caste woman’ or ‘a black man’) becomes a source of repeated points of distributional unfairness throughout their lives and over generations – not just in wealth and other resources such as land, but also societal spending on education, health, food and social safety nets or other opportunities that structure daily living conditions such as decent work, income and access to justice (Kabeer, 2010, 2011; Nichols, 2020; UNDP, 2018; WHO, 2008, pp. 50–59). Transitional justice, such as food aid, can relieve the immediate effects of such injustices, temporarily, but is another way in which contemporary and historical injustices, such as colonialism, remain hidden from political view (Richardson, 2020).

Multiple examples in the literature explain why such processes of exclusion, injustice and unfairness are important in producing and reproducing nutritional inequity. Without fair and inclusive access to education and social support, certain groups are discouraged to seek help from available services (food, care, health) (Barros et al., 2010; WHO, 2008, pp. 50–59), or these services simply do not exist as easily available in the localities in which certain groups live. Some social groups find they are further discriminated at the point of access by people responsible for important public services (Cambell et al., 2017), while better public services and environments – education, health, public space, retail of healthier foods might cluster around wealthier areas(WHO, 2008). Social position and human capital also interact, for example in the case of an illiterate female farmer finding barriers to setting up a bank account or accessing credit, because of a combination of their lack of human capital (education/literacy) and the discrimination they encounter from officials or official policy, affecting the farmer’s family’s material and food environments, as well as the broader food environment for others (Adegbite and Machethe, 2020). Such factors may be at play even in the case of theoretically ‘freely available’ services, including some health services and safety nets which provide or subsidise food or cooking fuel (Pradhan and Rao, 2018). Socio-economic and political contexts are likely to either be blind to such examples, or reinforce them (e.g. written signs and guidance that don’t take into account illiteracy or non-official languages, or aspects of the physical environment that don’t take into account disability).

3.1.4. Inequity over multiple scales: time, space and territory

The Nutrition Equity Framework also makes reference to temporal and spatial dimension to aid understanding that injustices, distributional unfairness and political exclusion build up not just over a lifetime, but over generations, adhering to different territorial and social groups and becoming ‘embodied’ (Krieger, 2001) in their very nutritional and health status (Nisbett, 2019; Wells, 2010). Determinants play out dynamically in different countries and ecological territories, as they change over the course of human development, and different stages of food systems and nutrition transitions. For example, the social transition in obesity has been described as primarily affecting high-income urban population groups at the early-stages of country economic development, before affecting lower-income groups in later stages (Baker et al., 2020b; Baker et al., 2020; Monteiro et al., 2004).

Factors operating to shape food systems and nutrition environments at local, territorial (such as the traditional territory of an Indigenous group; or a watershed), regional and national levels cannot be seen in isolation from global processes. The global food system is in fact a ‘system of systems’, spanning global to sub-national and even household levels, with strong multi-level interconnectedness (Hospes and Brons, 2016). Not only may national governments subscribe to a range of international political processes, such as trade, food and plant safety, climate or human rights treaties, but actors in the private sector, civil society, academia and other types of international organisations will also operate across multiple spatial scales. These processes and networks may lead to the replication of inequity over time and space (e.g. aggressive resource extraction continuing from colonial regimes to present day geopolitical relationships); or may attempt to resist such inequity (such as transnational alliances of famer/peasant organisations).

The temporal scale is also an important factor in understanding change in people’s bodies and health status as a result of nutrition inequity. Here, infancy and childhood are a critical time for the building of human capital and potential and act as an important period for socialisation into food practices, tastes and different eating cultures (Popkin et al., 2020), in ways that can positively reinforce diverse food cultures (Watson and Caldwell, 2005), but can also cement past inequity into food practices and preferences (Del Casino Jr (2015, p. 805). A crucial yet often unacknowledged factor influencing the feeding and care of children in particular, including the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding, is the structuring of care work within gender power systems, and women’s resulting time-poverty (J. P. Smith and Forrester, 2013; UN Women, 2019, 2021).

Box 1 provides an example of nutrition inequity with temporal and spatial dimensions through dispossession of peoples from their ancestral lands, a process that has been replicated through history via processes of colonialism and the privileging of ‘modern’ over ‘traditional’ knowledge (Hayes-Conroy and Hayes-Conroy, 2013; Horne, 2018; Nichols, 2020).

4. Discussion: action on the structural causes of malnutrition

The Nutrition Equity Framework proposes that inequality in all forms of malnutrition stems from structurally inequitable processes that play out over time and space and are driven by an ‘engine’ of unfairness, exclusion and injustice through unequal power. This framework posits that action on the social and political (including commercial) causes of malnutrition, and especially those mediated via food systems, is likely to be the most fundamental and sustainable way of improving nutrition equity, and can be used to identify priority areas for action. Below we summarise a set of actions inferred by the components of the framework as necessary (though perhaps not on their own sufficient) to improve nutrition equity, and discuss these in light of existing literature.

The WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health recommended that action aims to: 1) Improve Daily Living Conditions, 2) Tackle the Inequitable Distribution of Power, Money, and Resources and 3) Measure and Understand the Problem and Assess the Impact of Action (WHO, 2008). We adapt and extend these recommendations below for the field of nutrition, arguing that actors in international nutrition need to acknowledge the role of inequity in shaping who is malnourished; assess the structural causes of malnutrition as depicted in the Nutrition Equity Framework; and address nutrition inequity at these structural levels, in both research and action.

Firstly, nutrition researchers and practitioners need to formally acknowledge that inequity exists in the first place and fundamentally shapes who is affected by malnutrition in all its forms. This draws on important principles of ‘recognition justice’ (Fraser, 2007) in the wider equity literature and requires that daily and historical injustices, unfairness in resource and human capital distribution, and exclusion from political voice and agency is called out and recognised. Much nutrition policy research (Baker et al., 2018; Gillespie et al., 2013; Harris, 2019a; Nisbett et al., 2014) finds that nutrition as a sector is not a particularly political field, with a strong focus on technical interventions but less on the political economy of what it takes to get these into policy, or the coalitions working to encourage or block nutrition- and equity-sensitive action (Friel, 2020). Not enough attention has been paid in nutrition policy research to the importance of building broad-based advocacy networks or coalitions for nutrition action, even though collective action of this nature has been powerful in generating pro-nutrition policy reform (Baker et al., 2019). Policymakers are not the only audience for nutrition equity research: advocates and activists are also important actors in bringing nutrition-relevant change in many contexts (Hossain et al., 2014).

More broadly, in acknowledging inequity and injustice we note the need for a historical reckoning with ideological and historical processes such as colonialism, racism, patriarchy and neoliberalism, which have directly shaped food, nutrition and health systems, as well as the experience of people within them, brought into sharp relief by the COVID-19 pandemic (Büyüm et al., 2020). Bringing equity issues and ideas into mainstream discourse is a first step in rectifying nutrition inequities (Development Initiatives, 2020; UN Standing Committee on Nutrition, 2018). These ideas already have traction in global health (Ndumbe-Eyoh, 2020; Powers and Faden, 2019), and the NEF can help to explain these concepts to global nutrition constituencies who have traditionally focused further ‘downstream’ in the framework of malnutrition’s causes.

Secondly, research and practice in international nutrition and national nutrition contexts ought to regularly and comprehensively assess and report on the ways in which inequity shapes nutrition via the processes we have identified in the NEF. Globally and nationally, nutrition outcome data has been limited in the ways it describes inequalities, and it is recognised that there are many gaps which need to be filled by “simultaneous disaggregation of [outcome] data by multiple dimensions, including income, sex, age, race, ethnicity, migration status, disability, geographic location and other characteristics relevant to national contexts” (UN Women, Women Count, & United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2019). In addition, there is a need to better understand how these axes of marginalization interact and intersect, drawing on existing work in intersectionality (Bauer, 2014; López and Gadsden, 2017; Mullings and Schulz, 2006). There is room for improvement in current global and national data collection systems for understanding equity to ensure comprehensive and regular monitoring and reporting. Data collected via Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) modules on disability, for example, has only recently been improved (DHS Program, 2016) and will help meet calls for “disaggregated data to enable comparison between the disabled and their non-disabled peers” with regard to nutrition (Groce et al., 2014).

Notably, not all relevant equity factors are amenable to large-scale surveys, so a range of fit-for-purpose evidence is needed to properly assess equity in context, with attendant focus on building respect across disciplines for different types of research. This research will thus assess the social, economic, political and commercial determinants of malnutrition, focusing on ways of understanding structure and process as illustrated in the NEF, and not just outcome measures disaggregated by indicators of social stratification. Examples of such work also include “qualitative work to understand root causes” from the perspectives of those experiencing social disadvantage (UN Women et al., 2019). The latter is important to foreground the demands of those affected by malnutrition in all its forms, and of those who play vital roles in food and health provisioning and care (ibid.). Wider research in this vein takes many forms, as reviewed above (Table 1), from ethnographic explorations of lived experiences of nutrition inequity, to policy process studies of inequity in systems and services, to economic assessments of the asset bases, nutrition outcomes, life opportunities and service access of marginalised groups.

Thirdly, fairness and justice imply the need not only to recognise the imbalances in existing systems, and to use data and research to highlight these, but also the need for some form of action to address the situation. The nutrition community has long called for other sectors to become more ‘nutrition-sensitive’; there is now an urgent need for all nutrition-focused actions to become more ‘equity-sensitive’. This will mean a combination of interventions that focus on the most disadvantaged groups and how they experience the ‘engine of inequity’ in shaping their life chances; and adopting universal interventions that improve nutrition outcomes across the socioeconomic gradient, implemented at a scale and intensity that is proportionate to the level of disadvantage (‘proportionate universalism’ - Marmot et al. (2010)). Working practically on the upstream determinants of malnutrition means redistribution is needed through not only the classic redistributive politics of taxation, welfare, and social protection, but also the more radical reforms to land, labour and capital that have been attempted in some countries in terms of, for example, land reform and redistribution (Habitat, 2019; Holden et al., 2016), including gender-positive reforms (Ali et al., 2014) and alternative forms of ownership and production (Hairong, 2018; IPES Food, 2018; Kerr et al., 2011).4

One key limitation of many global hunger and malnutrition initiatives is that they are depoliticised and therefore lack focus on addressing the ‘engine of inequity’ and ensuring that communities have power over the food, health and care decisions that affect their lives (Harris, 2019b; Nisbett et al., 2014). Approaches designed to redress this balance prioritise participation and ownership of affected groups in designing and delivering policies and services. As Box 1 highlights, for instance, Indigenous food sovereignty - the right and responsibility of Indigenous people to healthy and culturally appropriate foods produced through traditional Indigenous practices - has emerged in the US and other contexts as an important strategy to support Indigenous communities in taking greater control over their land and food systems by increasing and protecting traditional and healthy foods (Grey and Patel, 2015; Jernigan, 2012b; Settee, 2020). Another key pathway is accountability of institutions for making these equitable, including forms of social accountability that involve people participating and auditing the decisions and services that affect them most (Gaventa and Barrett, 2012). Legal and moral frameworks such as human rights bring these ideas together, but are not embraced by all working in nutrition and are not strong norms embraced by all working within the global nutrition sector (Harris, Gibbons, Kaaba, Hrynick, & Stirton, Forthcoming). This illustrates the need for ethical guidance in global nutrition thinking and action, in parallel with empirical and technical guidance (Fanzo, 2015).

5. Conclusion

The Nutrition Equity Framework, illustrating the social and political determinants of malnutrition, is based on a synthesis of literature from multiple disciplines. As far as we are aware, it is the first framework to bring together theories, ideas and approaches from public health and health equity, development studies, social sciences, critical food studies, and work on Indigenous food systems. As such we hope it offers researchers clarity in understanding and analysing issues of nutrition equity, from the social groups and material circumstances we come from, to the structures and systems which shape our lives, to the engines of unfairness, exclusion and injustice which drive continued unequal outcomes. The framework also aims to be of use to policymakers, practitioners and activists working towards nutrition equity: in adapting its broad ideas to the specifics of different contexts, it can provide a structure to start conversations, guide data collection and analysis, and spur ethical action.

Why does this matter? Recognising the need to right historical injustice, including via redistribution, can work hand in hand with the need to realise political inclusion; recognise and reverse the various forms of exclusion that disbar people from the decisions that most affect their lives; and find ways to support and enhance the ways in which people are already making their voice and agency felt in social, political and economic structures that shape malnutrition and inequity. The Nutrition Equity Framework is an attempt to cut through the complexities inherent in these areas to help the conceptualisation of practical and political action for nutrition equity. We hope that this will further efforts to address malnutrition for everyone everywhere – less ‘leaving no-one behind’, more ‘holding no-one back’ from their natural proclivity and agency to realise their right to good nutrition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the International Expert Group of the Global Nutrition Report for review and comments at an earlier stage of this work, particularly to the Chairs, Renata Micha, Venkatesh Mannar, Charlotte Martineau of Development Initiatives. We are also grateful to Mary Wickenden at the Institute of Development Studies, for reading and commenting on a draft at this earlier stage and providing insightful recommendations on disability and exclusion. Funding for Jody Harris’ participation within this research was provided by long-term strategic donors to the World Vegetable Center: Taiwan, UK aid from the UK government, United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), Germany, Thailand, Philippines, Korea, and Japan.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests.

Nicholas Nisbett reports a relationship with Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation India that includes: funding grants. Kathryn Backholer reports a relationship with National Heart Foundation of Australia that includes: funding grants. Nicholas Nisbett reports a relationship with UK Research and Innovation that includes: funding grants.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100605.

Whilst there has been some progress with a slowing or decline in the prevalence of childhood obesity in some countries, these benefits fall disproportionately among children with greater social and economic resources(Chung et al., 2016).

Two studies (Salm et al., 2020; Harris et al., 2021) drew on peer-reviewed literature only; one study (Harris and Nisbett 2018) drew on both peer review and grey-literature, such as NGO and think tank reports.

Examples of this include work on the commercial determinants of health contributed by KB, PB and SF; and work on Indigenous food systems and sovereignty, contributed by VBJ.

For example, gender positive land reforms have been associated both with gender empowerment and improved natural resource conversation (Ali et al., 2014); food security (Habitat, 2019) and the nutritional status of children (Holden et al., 2016), while a systematic review of agroecological approaches, where equity considerations are often an important component, shows promising outcomes for food and nutrition security across the majority of studies in 55 cases (Kerr et al., 2021).

References

- Adegbite OO, Machethe CL, 2020. Bridging the financial inclusion gender gap in smallholder agriculture in Nigeria: an untapped potential for sustainable development. World Dev 127, 104755. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich R, Zwi AB, Short S, 2007. Advance Australia fair: social democratic and conservative politicians’ discourses concerning aboriginal and Torres Strait islander peoples and their health 1972–2001. Soc. Sci. Med 64 (1), 125–137. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali DA, Deininger K, Goldstein M, 2014. Environmental and gender impacts of land tenure regularization in Africa: pilot evidence from Rwanda. J. Dev. Econ 110, 262–275. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aurino E, 2017. Do boys eat better than girls in India? Longitudinal evidence on dietary diversity and food consumption disparities among children and adolescents. Econ. Hum. Biol 25, 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backholer K, Beauchamp A, Ball K, Turrell G, Martin J, Woods J, Peeters A, 2014. A framework for evaluating the impact of obesity prevention strategies on socioeconomic inequalities in weight. Am. J. Public Health 104 (10), e43–e50. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backholer K, Gupta A, Zorbas C, Bennett R, Huse O, Chung A, Peeters A, 2021. Differential exposure to, and potential impact of, unhealthy advertising to children by socio-economic and ethnic groups: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev 22 (3), e13144 10.1111/obr.13144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P, Brown AD, Wingrove K, Allender S, Walls H, Cullerton K, Lawrence M, 2019. Generating political commitment for ending malnutrition in all its forms: a system dynamics approach for strengthening nutrition actor networks. Obes. Rev 20, 30–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P, Gill T, Friel S, Carey G, Kay A, 2017. Generating political priority for regulatory interventions targeting obesity prevention: an Australian case study. Soc. Sci. Med 177, 141–149. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P, Hawkes C, Wingrove K, Demaio AR, Parkhurst J, Thow AM, Walls H, 2018. What drives political commitment for nutrition? A review and framework synthesis to inform the United Nations Decade of Action on Nutrition. BMJ Global Health 3 (1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P, Machado P, Santos T, Sievert K, Backholer K, Hadjikakou M, Lawrence M, 2020a. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes. Rev 21 (12), e13126 10.1111/obr.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P, Machado P, Santos T, Sievert K, Backholer K, Hadjikakou M, Lawrence M, 2020b. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes. Rev 10.1111/obr.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P, Santos T, Neves PA, Machado P, Smith J, Piwoz E, McCoy D, 2020. First-food Systems Transformations and the Ultra-processing of Infant and Young Child Diets: the Determinants, Dynamics and Consequences of the Global Rise in Commercial Milk Formula Consumption. Maternal & Child Nutrition, e13097. 10.1111/mcn.13097. n/a(n/a). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros FC, Victora CG, Scherpbier R, Gwatkin D, 2010. Socioeconomic inequities in the health and nutrition of children in low/middle income countries. Rev. Saude Publica 44 (1), 1–16. 10.1590/S0034-89102010000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, 2014. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Soc. Sci. Med 110, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beechey V, 1979. On patriarchy. Fem. Rev 3 (1), 66–82. 10.1057/fr.1979.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta ZA, Das J, Rizvi A, Gaffey M, Walker N, Horton S, for the Lancet Nutrition Interventions Review Group & the Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group, 2013. Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition: what can be done and at what cost. Lancet 382 (9890), 452–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Dewey KG, 2014. Promoting equity through integrated early child development and nutrition interventions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1308 (1), 1–10. 10.1111/nyas.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth A, Carroll C, 2015. How to build up the actionable knowledge base: the role of ‘best fit’ framework synthesis for studies of improvement in healthcare. BMJ Qual. Saf 24 (11), 700. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P, 1984. Distinction : a Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. [Google Scholar]

- Brokenleg I, Barber TK, Bennett NL, Boyce SP, Jernigan VBB, 2014. Gambling with our health: smoke-free policy would not reduce tribal Casino patronage. Am. J. Prev. Med 47 (3), 290–299. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne J, Gilmore M, Lock M, Backholer K, 2020. First Nations peoples’ participation in the development of population-wide food and nutrition policy in Australia: a political economy and cultural safety analysis. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büyüm AM, Kenney C, Koris A, Mkumba L, Raveendran Y, 2020. Decolonising global health: if not now, when? BMJ Global Health 5 (8), e003394. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadieux KV, Slocum R, 2015. What does it mean to do food justice? J. Political Ecol 22, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cambell J, Hirnschall G, Magar V, 2017. Ending Discrimination in Healthcare Settings Commentary. Retrieved from Geneva: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/ending-discrimination-in-health-care-settings. [Google Scholar]

- Carey R, Caraher M, Lawrence M, Friel S, 2016. Opportunities and challenges in developing a whole-of-government national food and nutrition policy: lessons from Australia’s National Food Plan. Publ. Health Nutr 19 (1), 3–14. 10.1017/S1368980015001834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. Summary Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey: 2015 Retrieved from.

- Chung A, Backholer K, Wong E, Palermo C, Keating C, Peeters A, 2016. Trends in child and adolescent obesity prevalence in economically advanced countries according to socioeconomic position: a systematic review: child obesity trends and socio-economic position. Obes. Rev 17 (3), 276–295. 10.1111/obr.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp J, Scrinis G, 2017. Big food, nutritionism, and corporate power. Globalizations 14 (4), 578–595. 10.1080/14747731.2016.1239806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Schutter O, 2014. The specter of productivism and food democracy. Wis. Law Rev (2), 199, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Del Casino VJ Jr., 2015. Social geography I: food. Prog. Hum. Geogr 39 (6), 800–808. [Google Scholar]

- Development Initiatives, 2020. Global Nutrition Report 2020. Action on Equity to End Malnutrition Retrieved from, Bristol, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon C, Young MG, 2010. Environmental racism and First Nations: a call for socially just public policy development. Can. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci 1 (1), 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- DHS Program, 2016. Press Release COLLABORATION YIELDS NEW DISABILITY QUESTIONNAIRE MODULE. Retrieved from. https://dhsprogram.com/Who-We-Are/News-Room/Collaboration-yields-new-disability-questionnaire-module.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, Smith L, 2006. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med. Res. Methodol 6 (1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SM, Ahmed S, Fanzo J, Herforth A, 2020. Food environment typology: advancing an expanded definition, framework, and methodological approach for improved characterization of wild, cultivated, and built food environments toward sustainable diets. Foods 9 (4), 532. 10.3390/foods9040532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericksen PJ, 2008. Conceptualizing food systems for global environmental change research. Global Environ. Change 18 (1), 234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Fanzo J, 2015. Ethical issues for human nutrition in the context of global food security and sustainable development. Global Food Security 7, 15–23. 10.1016/j.gfs.2015.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finegold K, Pindus N, Levy D, Tannehill T, 2009. Tribal Food Assistance: A Comparison of the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) The Urban Institute and Support Services International, Inc. November, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Food Ethics Council, 2020. Fairness framework Retrieved from. https://www.foodethicscouncil.org/resource/fairness-framework-fairness-for-whom/.

- Ford JD, 2012. Indigenous health and climate change. Am. J. Public Health 102 (7), 1260–1266. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser N, 2007. Feminist politics in the age of recognition: a two-dimensional approach to gender justice. Studies Soc. Justice 1 (1), 23–35. 10.26522/ssj.v1i1.979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friel S, 2020. Redressing the corporate cultivation of consumption: releasing the weapons of the structurally weak. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel S, Chopra M, Satcher D, 2007. Unequal weight: equity oriented policy responses to the global obesity epidemic. BMJ 335 (7632), 1241–1243. 10.1136/bmj.39377.622882.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel S, Ford L, 2015. Systems, food security and human health. Food Security 7 (2), 437–451. [Google Scholar]

- Friel S, Pescud M, Malbon E, Lee A, Carter R, Greenfield J, Meertens B, 2017. Using systems science to understand the determinants of inequities in healthy eating. PLoS One 12 (11), e0188872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa J, Barrett G, 2012. Mapping the outcomes of citizen engagement. World Dev 40, 2399–2410. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie S, Haddad L, Mannar V, Menon P, Nisbett N, 2013. The politics of reducing malnutrition: building commitment and accelerating progress. Lancet 382 (9891), 552–569. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60842-9, 1016/S0140-6736(13)60842-9. Epub 2013 Jun 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MJ, Booth A, 2009. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J 26 (2), 91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K, 2018. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Invest 48 (6) 10.1111/eci.12931 e12931–n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey S, Patel R, 2015. Food sovereignty as decolonization: some contributions from Indigenous movements to food system and development politics. Agric. Hum. Val 32 (3), 431–444. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths K, Coleman C, Lee V, Madden R, 2016. How colonisation determines social justice and Indigenous health—a review of the literature. J. Pop Res 33 (1), 9–30. 10.1007/s12546-016-9164-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groce N, Challenger E, Berman-Bieler R, Farkas A, Yilmaz N, Schultink W, Kerac M, 2014. Malnutrition and disability: unexplored opportunities for collaboration. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 34 (4), 308–314. 10.1179/2046905514Y.0000000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthman J, DuPuis M, 2006. Embodying neoliberalism: economy, culture, and the politics of fat. Environ. Plann. Soc. Space 24 (3), 427–448. [Google Scholar]

- Habitat U, 2019. Land Tenure and Climate Vulnerability. A World in Which Everyone Enjoys Secure Land Rights Retrieved from Nairobi. https://unhabitat.org/land-tenure-and-climate-vulnerability. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez AY, Gonzalez M, Kulik MC, Vijayaraghavan M, Glantz SA, 2019. Uneven access to smoke-free laws and policies and its effect on health equity in the United States: 2000–2019. Am. J. Public Health 109 (11), 1568–1575. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hairong Y, 2018. Puhan Rural Community - shanxi, China: rebuilding community ties as a pathway to cooperative-led local food systems. In: Food I (Ed.), Breaking Away from Industrial Food and Farming Systems: Seven Case Studies of Agroecological Transition, IPES Food, pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky O, Grace D, Hunting G, Giesbrecht M, Fridkin A, Rudrum S, Clark N, 2014. An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: critical reflections on a methodology for advancing equity. Int. J. Equity Health 13 (1), 119. 10.1186/s12939-014-0119-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, 2019a. Coalitions of the Willing? Advocacy Coalitions and the Transfer of Nutrition Policy to Zambia Health Policy and Planning, Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, 2019b. Narratives of Nutrition: Alternative Explanations for International Nutrition Practice World Nutrition. [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Gibbons S, Kaaba OB, Hrynick T, & Stirton R (Forthcoming). A ‘right to Nutrition’ in its Social, Legal and Political Context: Zambia’s Experience in a Global System

- Harris J, Huynh P, Nguyen HT, Hoang N, Mai LT, Tuyen LD, Nguyen PH, 2021a. Nobody Left behind? Equity and the Drivers of Stunting Reduction in Vietnamese Populations. Food Security 13, 803–818. [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Nisbett N, 2018. Equity in social and development studies research: what insights for nutrition? SCN News 43. [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Nisbett N, 2020. The basic determinants of malnutrition: resources, structures, ideas and power. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag 10, 817–827. Special Issue on Political Economy of Food Systems. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Tan W, Mitchell B, Zayed D, 2021b. Equity in agriculture-nutrition-health research: a scoping review. Nutr. Rev 80 (1), 78–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C, Ruel MT, Salm L, Sinclair B, Branca F, 2020. Double-duty actions: seizing programme and policy opportunities to address malnutrition in all its forms. Lancet 395 (10218), 142–155. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Conroy A, Hayes-Conroy J, 2013. Doing Nutrition Differently: Critical Approaches to Diet and Dietary Intervention Routledge, London. [Google Scholar]

- Headey D, Hoddinott J, Park S, 2017. Accounting for nutritional changes in six success stories: a regression-decomposition approach. Global Food Security 13, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Herman DR, Taylor Baer M, Adams E, Cunningham-Sabo L, Duran N, Johnson DB, Yakes E, 2014. Life course perspective: evidence for the role of nutrition. Matern. Child Health J 18 (2), 450–461. 10.1007/s10995-013-1280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey L, Pelletier DL, 2011. Bolivia’s multisectoral zero malnutrition Program: insights on commitment, collaboration, and capacities. Food Nutr. Bull 32 (2_Suppl. 2), S70–S81. 10.1177/15648265110322S204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden S, Bezu S, Tilahun M, 2016. How Pro-poor Are Land Rental Markets in Ethiopia?

- Horne M, 2018. Monday December 03). Highland Woes Still Linked to Clearances The Times. [Google Scholar]

- Hospes O, Brons A, 2016. Food system governance: a systematic literature review. Food systems governance 13–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain N, Brito L, Jahan F, Joshi A, Nyamu-Musembi C, Patnaik B, Sinha D, 2014. Them Belly Full (But We Hungry)’: Food Rights Struggles in Bangladesh, India, Kenya and Mozambique. Synthesis report from DFID-ESRC research project “Food Riots and Food Rights Institute of Development Studies, Brighton. [Google Scholar]

- IPES Food, 2018. Breaking Away from Industrial Food and Farming Systems: Seven Case Studies of Agroecological Transition Retrieved from. http://www.ipes-food.org/reports/.

- Jernigan VBB, 2012a. Addressing food security and food sovereignty in native American communities. In: Joe JR, Gachupin FC (Eds.), Health and Social Issues of Native American Women Praeger, Santa Barbara, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan VBB, 2012b. Addressing food security and food sovereignty in Native American communities In: Health and Social Issues of Native American Women, pp. 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan VBB, Haring RC, 2019. Health and Well-Being Among Native American Indigenous Peoples. Well-Being as a Multidimensional Concept: Understanding Connections among Culture Community, and Health, p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N, 2005. Social Exclusion: Concepts, Findings and Implications for the MDGs. Paper commissioned as background for the Social Exclusion Policy Paper Department for International Development (DFID), London. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N, 2010. Can the MDGs Provide a Pathway to Social Justice? the Challenge of Intersecting Inequalities Retrieved from. New York. http://www.mdgfund.org/sites/default/files/MDGs_and_Inequalities_Final_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N, 2011. Gendered poverty traps: inequality and care in a globalised world. Eur. J. Dev. Res 23 (4), 527–530. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson L, Naess LO, Nightingale A, Thompson J, 2018. ‘Triple wins’ or ‘triple faults’? Analysing the equity implications of policy discourses on climate-smart agriculture (CSA). J. Peasant Stud 45 (1), 150–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr RB, Berti PR, Shumba L, 2011. Effects of a participatory agriculture and nutrition education project on child growth in northern Malawi. Publ. Health Nutr 14 (8), 1466–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr RB, Madsen S, Stüber M, Liebert J, Enloe S, Borghino N, Wezel A, 2021. Can agroecology improve food security and nutrition? A review. Global Food Security 29, 100540. [Google Scholar]

- Kite G, Manuel Roche J, Wise L, 2014. Leaving No One behind under the Post-2015 Framework: incentivizing equitable progress through data disaggregation and interim targets. Development 57 (3–4), 376–387. 10.1057/dev.2015.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, 2001. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int. J. Epidemiol 30 (4), 668–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger A, 1983. Anthropological and socio-medical health care research in developing countries. Soc. Sci. Med 17 (3), 147–161. 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S, 2017. Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention: A New Framework. 10.31478/201701c. Discussion Paper Retrieved from. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika SK, 2019. A framework for increasing equity impact in obesity prevention. Am. J. Public Health 109 (10), 1350–1357. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach M, Nisbett N, Cabral L, Harris J, Hossain N, Thompson J, 2020. Food politics and development. World Dev 134, 105024. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López N, Gadsden VL, 2017. Health Inequities, Social Determinants and Intersectionality Retrieved from, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Love CV, Taniguchi TE, Williams MB, Noonan CJ, Wetherill MS, Salvatore AL, Jernigan VBB, 2019. Diabetes and obesity associated with poor food environments in American Indian communities: the tribal health and resilience in vulnerable environments (THRIVE) study. Curr. Dev. Nutr 3 (Suppl. ment_2), 63–68. 10.1093/cdn/nzy099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackian S, Bedri N, Lovel H, 2004. Up the garden path and over the edge: where might health-seeking behaviour take us? Health Pol. Plann 19 (3), 137–146. 10.1093/heapol/czh017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vol. 1 Macpherson W, 1999. The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry Stationery Office Limited London. [Google Scholar]