Abstract

Acute pain is one of the most frequent, and yet one of the most challenging, complaints physicians encounter in the emergency department (ED). Currently, opioids are one of several pain medications given for acute pain, but given the long-term side effects and potential for abuse, alternative pain regimens are sought. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks (UGNB) can provide quick and sufficient pain control and therefore can be considered a component of a physician’s multimodal pain plan in the ED. As UGNB are more widely implemented at the point of care, guidelines are needed to assist emergency providers to acquire the skill necessary to incorporate them into their acute pain management.

Keywords: Ultrasound Guided Nerve Blocks, Regional Anesthesia, Ultrasound Guided Procedures, Pain Management, Opioids

Introduction

Background: Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blocks: Suggested Procedural Guidelines in The Emergency Department

Acute pain is one of the most frequently encountered complaints in the Emergency Department (ED) 1, 2, 3. Because of the increased awareness of opioid tolerance and potential for downstream abuse, most clinicians have adopted a multimodal pathway for optimal management of acute pain in the ED 4, 5. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks (UGNB) are a core element of this multifaceted approach to pain 6, 7. Although traditionally used by anesthesiologists for intraoperative anesthesia and the management of post-operative pain, targeted UGNB can also significantly reduce acute pain in ED patients 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. When performed by trained EM physicians, UGNB may also decrease unintended side effects from opioids and procedural sedation, such as hypotension and respiratory depression 19, 20.

Recently, the American College of Emergency Physicians released a Policy Statement on the utilization of UGNB in the Emergency Department, endorsing the use of this procedural skill as a part of multimodal pain control in the ED 21. Further, the American College of Surgeons recently released guidelines on the management of acute pain in trauma patients, endorsing the use of UGNB 19. In the ED, UGNB have been shown to significantly reduce pain, decrease the risk of delirium and decrease patient length of stay without an increase in adverse events 22, 23, 24, 25, 26.

Ultrasound visualization of both specific nerves and relevant fascial planes greatly enhances clinician comfort in performing UGNB. This allows clinicians to determine a clear needle trajectory while visualizing the needle tip during the entire procedure. This gives ED clinicians the ability to avoid vascular structures and make real-time adjustments that are necessary for effective perineural spread of injectate. Specifically, ultrasound enhances the nerve block duration, decrease complications, and reduce the time spent performing the procedure, therefore providing a more efficacious block 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36.

The following document represents a national collaborative effort by an expert group of physicians to define the scope of practice for UGNB in the ED. We present this document as guidelines for the use of UGNB performed by emergency physicians as a strategy to reduce the reliance of systemic opioids. Specifically, our objectives are as follows:

Define and describe the common tasks used when performing a UGNB

Describe the core competencies associated with UGNB

Suggest a credentialing system for clinicians working in the emergency department

Describe the specific complications associated with UGNB.

Due to a lack of published guidelines, we present these guidelines for ED physicians when performing UGNB.

Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Block Procedural Department Workflow

Consent

A hospital/health system policy should be in place regarding the need for either a verbal or written patient consent before performing UGNB in the ED. Specific attention should be given to LAST syndrome, peripheral nerve injury, procedural pain, bleeding, infection, and block specific complications (i.e. pneumothorax).

Equipment

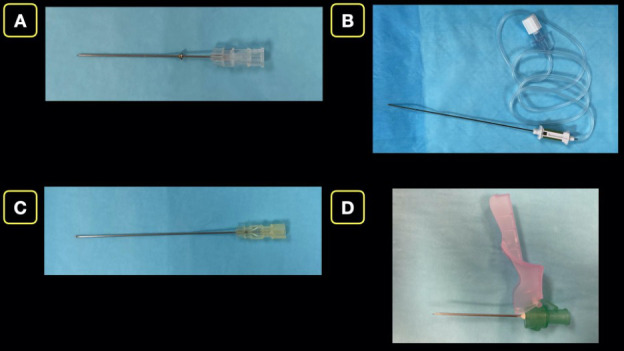

The operator should choose an ultrasound transducer dependent on the depth of the targeted nerve or fascial plane. UGNB with a required depth less than 5-6 cm can be performed with a high frequency linear probe, while deeper blocks will require a lower frequency curvilinear probe. Echogenic short-beveled needles are recommended if available, otherwise the use of other short-bevel needles, blunt tip spinal needles or Touhy-tip needles are acceptable. Sharp cutting needles are not recommended due to concerns of peripheral nerve injury. (Figure 1). Finally, the needle length should directly be related to the depth of the structures of interest.

Figure 1 . Nerve Block needles. A) Blunt tip 38 mm (1.5 in) Regional Block Needle. B) Blunt tip 100 mm (3.9 in) Regional Block Needle. C) Blunt tip 90 mm (3.5 in) Spinal Needle. D) Sharp tip 40 mm (1.6 in) Cutting Needle.

Based on consensus, we recommend continuous ECG, pulse oximetry, and intermittent blood pressure monitoring should be performed on all patients during and after a large volume block (greater than 10 mL) 37. Equipment for airway management and advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation, as well as lipid emulsion, should be immediately available for managing life-threatening complications.

Anesthetic

The anesthetic should be chosen based on the desired length of pain relief. For short relief, 1% lidocaine will provide anesthesia for approximately 45-90 minutes when performing a laceration closure or reduction of joint dislocation. For longer analgesia, ropivacaine or bupivacaine are preferred agents (Table 1). Clinicians should be aware of maximal doses for the anesthetic being used in order to prevent local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) syndrome. Adjuncts can be considered in addition to the local anesthetic to serve as a marker for intravascular injection (epinephrine) and/or further prolong the duration of action (i.e., dexamethasone) 38, 39.

Table 1. Anesthetic choices and their respective expected duration of actions for UGNBs in the ED.

|

Local Anesthetic |

Estimated half-life (min) |

Duration of Anesthesia (h) |

Maximum Dosage (mg/kg) |

Common uses |

|

1% Lidocaine |

95 |

1-2 |

4 |

Laceration repairs, hand surgery |

|

0.5% Bupivacaine |

160 |

6-8 |

2 |

Fractures, burns, acute-on-chronic pain indications |

|

0.5% Ropivacaine |

250 |

6-8 |

3 |

Fractures, burns, post-operative pain, epidural anesthesia |

Procedure

Prior to starting the procedure, the correct side of the body should be marked and verified by the operator. It is also during this time before the procedure that there should be a pre-procedure briefing. In this the entire team should review the planned procedure and be made aware of potential complications with appropriate interventions, examples include a pneumothorax with corresponding chest tube or LAST and intralipid.

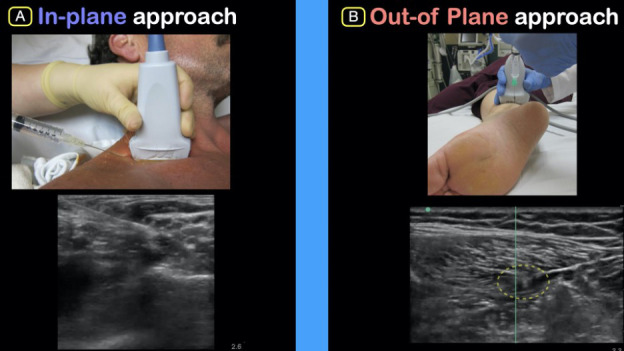

An UGNB is considered a sterile procedure 40. Once sterile, position the ultrasound machine directly in front of the provider and in line with the target of interest. Most UGNBs are performed in-plane with the needle parallel to the direction of the probe with the entire length of the needle (and specifically the needle tip) visualized. In cases where this is not possible, an out-of-plane guided procedure can be performed. In this technique, the needle is advanced perpendicularly to the ultrasound probe and the needle is not visualized in its entirety.

Once the targeted nerve and/or fascial plane is identified, the needle should be inserted in-plane, if possible. We recommend using small aliquots of sterile saline as the needle tip nears the target nerve or to open the fascial plane (hydrodissection) in order to optimally place anesthetic in the desired location. Using these two aforementioned techniques will help locate the needle tip as well as improve needle tip placement. Once the needle is optimally located gently deposit anesthetic in 1-3 ml aliquots. We recommend aspirating between repeated injections to ensure lack of vascular puncture and clear visualization of anechoic anesthetic on the ultrasound screen (Figure 2).

After completion of the UGNB, the sterile transducer cover should be removed, and low-level disinfection (LLD) performed on the transducer/probe 41.

Figure 2 . Peripheral Tibial Nerve Block: In-plane approach of needle with visualization of anechoic fluid surrounding nerve on ultrasound.

Monitoring

Currently, there is no evidence-based guidance on the length or need of cardiac monitoring post procedure. However, we find that if greater than 10 cc’s of anesthetic is being used, or if a block is located near large intravascular structures, the patient should be left on the cardiac monitor for a period of observation for the possible development of hypotension or dysrhythmia for at least 60 minutes. This volume of anesthetic assumes using commonly available medications (i.e. Lidocaine, Bupivacaine, or Ropivacaine). Otherwise, we find that 30 minutes is appropriate. During the time of observation, a detailed post-procedure neurologic exam should be documented. If the patient is to be discharged after observation, the patient should be started on a defined multimodal oral pain regimen to avoid the potential of rebound pain when the anesthetic wears off. A clear follow-up system should be present in managing complications such as peripheral nerve injury if they present.

Documentation

All UGNBs should be documented in the health record including the clinical indication, a pre-block neurovascular exam, the specific block being performed, the type, concentration and amount of anesthetic, any adjuvants, procedural complications, and a detailed post-block neurologic examination. If the patient is being admitted, a limb alert identifier can be placed to ensure all staff are aware of the motor deficits that may be present post-block. Communication with the ED nursing team and other clinicians caring for the patient is vital to ensure a safe transition of care to the inpatient team.

Indications, Training and Credentialing for Point-Of-Care Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blocks

Indications

Single injection ultrasound-guided nerve blocks are ideal for pain control from acute injuries as well as an alternative to procedural sedation for painful procedures. The specific block should be based on the nervous innervation of the affected area, while the choice and volume of anesthetic medication and dose are based on duration of analgesia desired. A complete list of indications affected dermatomes and their associated nerve block can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. A current list of UGNBs and their specific indications, affected dermatomes and specific complications. (Con’t on next page).

|

Upper Extremity | |||

|

Dermatomal Distribution |

Common Indications |

Specific Complications |

|

|

Superficial Cervical Plexus |

Lateral neck extending from clavicle to anteauricular and retroauricular areas |

– Clavicular fracture – IJ placement – Earlobe lacerationsSubmandibular abscess and/or Laceration |

– Vascular puncture |

|

Interscalene |

C5-C7. Complete anesthesia from shoulder to distal humerus. Ulnar nerve is rarely blocked. |

– Shoulder dislocation – Proximal humeral fracture – Laceration and/or abscess of upper arm |

– Vascular puncture – Intravascular injection – Ipsilateral phrenic nerve palsy – PNIPneumothorax |

|

Supraclavicular |

Mid-humerus to distal hand. |

– Distal radial fracture – Distal humerus fracture – Deltoid abscess |

– Vascular puncture – Intravascular injection – PNIPneumothorax |

|

RAPTIR – Retroclavicular Approach To the Infraclavicular Region, Retroclavicular Block of the Brachial Plexus |

Mid-humerus to distal hand |

– Arm fractures/dislocations – Large arm abscesses/lacerations |

– Vessel puncture – Intravascular injection – PNIPneumothorax |

|

Forearm – Radial, Median, Ulnar |

Radial: Radial aspect of dorsum of hand thumb, index finger, middle finger and radial half of ring finger Median: Medial aspect of palmar surface, thumb, index, middle finger and radial aspect of ring finger Ulnar: Ulnar portion of palmar and dorsum of hand and fifth finger. Ulnar aspect of ring finger |

– Large lacerations/abscess – Hand fracture/reduction – Finger amputation – Blast injuries |

– Vessel puncturePNI |

|

Trunk | |||

|

Regions of Anesthesia |

Common Indications |

Specific Complications |

|

|

PECS |

Axilla, Breast |

– Breast abscess – Axillary abscess |

|

|

Serratus Anterior |

Mid-axilla to anterior T3-9 |

– Rib Fractures – Thoracic abscess – Tube thoracostomy |

– Pneumothorax |

|

Thoracic Erector Spinae (T5-T12) |

Truncal nerve INCLUDING posterior aspect. Sympathetic trunk: visceral pain relief |

– Posterior rib fracture – Extensive chest wall trauma – Herpes zoster – Acute appendicitis – Vertebral compression fracture |

– Pneumothorax |

|

TAP – Transverse Abdominis Plane |

T10-12 distribution anterior abdomen |

– Appendicitis – Trunk abscess |

|

|

Penile |

Circumferential penile distribution |

– Priapism – Penile trauma |

|

|

Lower Extremity | |||

|

Regions of Anesthesia |

Common Indications |

Specific Complications |

|

|

Transgluteal Sciatic Nerve Block |

Posterior thigh to lateral ankle and knee |

– Sciatica |

– PNI |

|

Fascia Iliaca |

Anterior thigh from inguinal ligament to knee |

– Hip fracture |

– Vessel punctureIntravascular injection |

|

Femoral Nerve |

Anterior thigh from greater trochanter to knee |

– Femur fracture – Patellar fracture – Thigh abscess |

– Vessel puncture – Intravascular injection – PNI |

|

PENG – Pericapsular Nerve Group |

Proximal hip joint including medial pelvis and proximal femur |

– Acetabular fracture – Pubic rami fracture – Intertrochanteric hip fracture – Femoral neck fracture |

– Vessel punctureIntravascular injection |

|

Saphenous Nerve |

Medial malleolus of ankle and calf |

– Distal tibia fracture |

– Intravascular injection |

|

Distal Sciatic Nerve |

Distal ⅔ of lower extremity with exception of medial aspect of leg |

– Distal tibia/fibula fracture – Achilles tendon rupture – Lateral/Posterior calf abscess/laceration |

–Intravascular injection – PNI |

|

Posterior Tibial Nerve |

Plantar aspect of foot |

– Plantar laceration – Plantar foreign body removal – Plantar abscess – Inadequate anesthesia on extreme medial/lateral aspect of foot |

|

Training and Credentialing for Point-Of-Care Nerve Blocks

Since 2001, clear and succinct ultrasonographic credentialing recommendations for POCUS were established by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP). The ultrasonographic guidelines recommended a benchmark minimum of 25-50 quality reviewed scans per modality to demonstrate technical and interpretive ability 42. Conversely for ultrasound guided procedures, 10 quality reviewed scans were recommended. A similar recent guideline for ED transesophageal echocardiography was recently published 43. As UGNBs are an extension of soft tissue and musculoskeletal ultrasound, skill with image acquisition and interpretation will have already been achieved through credentialing in these modalities 44.

The standards presented here may provide a guideline for emergency departments to utilize when credentialing physicians in UGNBs. When looking across other specialties for guidance, currently, the joint committee and the The American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine have omitted any specific recommendations when credentialing providers 45. However, the ACGME has set a standard minimum of 40 peripheral nerve block procedures for anesthesia residents 46. As UGNB education and training has not been standardized within the ED POCUS guidelines, it is important to set a minimum standard.

Although UGNBs are quite similar to a number of other modalities in the ultrasound guidelines set forth by ACEP, additional required skills are still needed. Operators must be able to visualize and identify specific fascial planes and/or peripheral nerves, visualize the spread of anesthetic with the ability to make adjustments to optimize placement of injectate, detailed understanding of sensory and motor function of specific nerves, and have a thorough understanding of the specific complications associated with UGNBs. A specific skill set needed for proficiency can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Skill Sets associated with Proficiency.

|

Image optimization |

Image Interpretation |

Needle Insertion and Injection |

|

Learn the importance of transducer pressures |

Identify Nerves |

Develop in-plane technique to maximize needle visualization |

|

Learn the importance of transducer alignment |

Identify Muscles and Fascia |

Develop out-of-plane technique |

|

Learn the importance or transducer alignment |

Identify Blood Vessels |

Understand the contraindications for each block |

|

Maximizing needle visualization |

Identify Bone and Pleura |

Visualize correct and incorrect anesthetic placement |

|

Understand Anisotropy |

Minimize unintentional transducer movement |

|

|

Identify Acoustic Artifacts |

Visualize and recognize intraneuronal needle location |

|

|

Identify Needle |

In keeping with ACEP Ultrasound guidelines, providers seeking credentialing in ultrasound-guided nerve blocks should:

Complete 2-4 hours of UGNB continuing medical education

Complete a minimum of 10 quality reviewed US-guided nerve blocks (of any type) on live patients and simulation models

Complete a standardized assessment by a credentialed UGNB provider.

Like transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), UGNB imaging is a new technical skill. Therefore, a minimum number of UGNB may not be the most accurate method for assessment. A standardized direct observational tool may be more desirable as has been recommended by the recent TEE guidelines. As UGNB is also highly dependent on hand-eye coordination, a standardized direct observational assessment tool is likely more ideal.

As with all new ultrasonographic guidelines, the goal is to offer guidance for optimal performance and safety, and not set unrealistic roadblocks to beneficial novel techniques. These guidelines aim to ensure provider proficiency to provide safe patient care when performing UGNBs, and we based this document on similar anesthesia literature 47, 48.

Specific Complications from Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blocks

Peripheral Nerve Injury

Peripheral Nerve Injury (PNI) occurs rarely (less than 0.02%) with 99% of cases resolving within one year 49. If a patient has a motor or sensory deficit, peripheral neuropathy, or poorly managed diabetes we recommend against performing an UGNB given the higher incidence of peripheral nerve injury. To reduce the possibility of PNI, always visualize the needle tip before injecting anesthetic, use a low-pressure injection technique, and a blunt tip needle if available. Additionally, the clinician can ask the patient if there is any discomfort or neuropathic pain during the injection. There should be a clearly defined system for follow-up for patients who persist to have paresthesia, pain or neurological deficits post block.

Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity

Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity (LAST) is a rare but serious complication that is thought to be due to inadvertent injection of local anesthetic into the vascular system 50, 51. In order to prevent LAST, it is necessary to have clear needle tip visualization throughout the procedure, aspirate frequently prior to, and while, injecting anesthetic, and ensure that the dose of anesthetic being used is under the maximum recommended dose. If your patient exhibits symptoms including vertigo, tinnitus, circumoral numbness, tremors, myoclonic jerks, convulsions, or cardiovascular collapse, the immediate use of intralipid is advised. Intravenous 20% lipophilic emulsion (IVLE) should be easily available to any provider performing UGNBs and a simple protocol readily available for dosing.Specific guidelines in terms of the storage of IVLE and dosing in cases of LAST, should be in place prior to performing this procedure.

Compartment Syndrome

The ability of UGNBs to mask the signs and symptoms of a developing compartment syndrome is debated in the literature 52, 53, 54, 55, 56. Unfortunately, there is no clear evidence to determine which patients could progress to elevated compartment pressures, forcing caution to be used when performing UGNBs in patients with specific injury patterns that are associated with developing compartment syndrome (e.g., high-energy tibia fractures). We recommend discussing with the appropriate consultants prior to performing an UGNB in patients with high-energy mechanism injuries (i.e., tibial shaft fractures, forearm fractures, etc.), or if there is clinical concern for a developing compartment syndrome. For all nerve blocks, a clear interdepartmental/multidisciplinary policy in regard to injury patterns that require consultation before UGNBs will allow for optimal patient selection.

Conclusion

Acute pain is one of the most frequently encountered complaints in the Emergency Department and it is best addressed through the utilization of a multimodal pathway. Targeted UGNBs should be considered a critical component of a true multimodal approach. UGNBs offer the benefit of minimizing, or avoiding side effects of parenteral medications and procedural sedation. In addition to ACEP’s recent Position Statement on UGNB, these guidelines should assist emergency providers in establishing a protocol for safely incorporating UGNB into the management of their patients with acute pain or prior to performing a procedure.

Statement of Ethics Approval/Consent

As this piece represents a consensus guideline, patient approval/consent was not obtained.

Disclosures

Andrew Goldsmith holds a grant from Massachusetts Life Sciences, has received consulting fees from Phillips, Exo, and Bain Capital, and has received honoraria from Indian Health Services. Arun Nagdev holds stock options in Exo Inc., and is a salaried employee of Exo Inc.

References

- Mccaig L F, Burt C W. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2005. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2003 Emergency Department Summary. [Google Scholar]

- Todd K H, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, Crandall C S, Fosnocht D E, Homel P, Tanabe P, Group Pemi Study. Pain in the emergency department: Results of the pain and emergency medicine initiative (PEMI) multicenter study. J Pain. 2007;8(6):460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin S A, Burton J H, Gerardo C J, Hatten B W, Mace S E, Silvers S M, Fesmire F M. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(2):247–58.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman B W, Dym A A, Davitt M, Holden L, Solorzano C, Esses D, Bijur P E, Gallagher E J. Naproxen with cyclobenzaprine, oxycodone/acetaminophen, or placebo for treating acute low back pain: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1572–1580. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A K, Bijur P E, Esses D, Barnaby D P, Baer J. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661–1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd K H. A Review of Current and Emerging Approaches to Pain Management in the Emergency Department. Pain Ther. 2017;6:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s40122-017-0090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amini R, Kartchner J Z, Nagdev A, Adhikari S. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks in emergency medicine practice. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2016;35(4):731–736. doi: 10.7863/ultra.15.05095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Thom S, Haber B, Sarani N, Ottenhoff J, Jackson B, Rance L, Ehrman R. Regional Anesthesia in the Emergency Department: an Overview of Common Nerve Block Techniques and Recent Literature. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2022;10:54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Riddell M, Ospina M, Holroyd-Leduc J M. Use of femoral nerve blocks to manage hip fracture pain among older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review. CJEM. 2016;18(4):245–252. doi: 10.1017/cem.2015.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritcey B, Pageau P, Woo M Y, Perry J J. Regional nerve blocks for hip and femoral neck fractures in the emergency department: a systematic review. CJEM. 2016;18(1):37–47. doi: 10.1017/cem.2015.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamid K, Elhawary H, Turner J P. The use of the erector spinae plane block to decrease pain and opioid consumption in the emergency department: a literature review. J Emerg Med. 2020;58(4):603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant E, Dixon B, Luftig J, Mantuani D, Herring A. Ultrasound-guided serratus plane block for ED rib fracture pain control. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;35(1):197.e3–197.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring A A, Stone M B, Nagdev A D. Ultrasound-guided abdominal wall nerve blocks in the ED. Am J of Emerg Med. 2012;30(5):759–764. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clattenburg E, Herring A, Hahn C, Johnson B, Nagdev A. ED ultrasound-guided posterior tibial nerve blocks for calcaneal fracture analgesia. Am J of Emerg Med. 2016;34(6):1183.e1–1183.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons C, Herring A A. Ultrasound-guided axillary nerve block for ED incision and drainage of deltoid abscess. Am J of Emerg Med. 2017;35(7):1032.e3–1032.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selame L A, Mcfadden K, Duggan N M, Goldsmith A J, Shokoohi H. Ultrasound-guided transgluteal sciatic nerve block for gluteal procedural analgesia. J of Emerg Med. 2021;60(4):512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe T A, Shokoohi H, Liteplo A, Goldsmith A. A novel application of ultrasound-guided interscalene anesthesia for proximal humeral fractures. J of Emerg Med. 2020;59(2):265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith A J, Liteplo A, Hayes B D, Duggan N, Huang C, Shokoohi H. Ultrasound-guided transgluteal sciatic nerve analgesia for refractory back pain in the ED. Am J of Emerg Med. 2020;38(9):1792–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettner S C, Willschke H, Marhofer P. Does regional anaesthesia really improve outcome? Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(Sup1):S190–S195. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin F L, Haran J P, Liebmann O. A comparison of ultrasound-guided three-in-one femoral nerve block versus parenteral opioids alone for analgesia in emergency department patients with hip fractures: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(6):584–591. doi: 10.1111/acem.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physicians American College of Emergency. American College of Emergency Physicians. ACEP Policy Statement: Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blocks Position Statement. https://www.acep.org/patient-care/policy-statements/ultrasound-guided-nerve-blocks/ 2021

- Surgeons American College of. Best Practices Guidelines for Acute Pain Management in Trauma Patients. 2020

- Pasero C L, Mccaffery M. Reluctance to order opioids in elders. Am J Nurs. 1997;97:20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roback M G, Wathen J E, Bajaj L, Bothner J P. Adverse events associated with procedural sedation and analgesia in a pediatric emergency department: a comparison of common parenteral drugs. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(6):508–513. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison R S, Dickman E, Hwang U, Akhtar S, Ferguson T, Huang J, Jeng C L, Nelson B P, Rosenblatt M A, Silverstein J H, Strayer R J, Torrillo T M, Todd K H. Regional Nerve Blocks Improve Pain and Functional Outcomes in Hip Fracture: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2433–2439. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouzopoulos G, Vasiliadis G, Lasanianos N, Nikolaras G, Morakis E, Kaminaris M. Fascia iliaca block prophylaxis for hip fracture patients at risk for delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Orthopaed Traumatol. 2009;10(3):127–133. doi: 10.1007/s10195-009-0062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaivas M, Adhikari S, Lander L. A prospective comparison of procedural sedation and ultrasound-guided interscalene nerve block for shoulder reduction in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(9):922–927. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezel O, Kaldirim U, Bilgic S, Deniz S, Eyi Y E, Ozyurek S, Durusu M, Tezel N. A comparison of suprascapular nerve block and procedural sedation analgesia in shoulder dislocation reduction. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(6):549–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S S, Ngeow J, John R S. Evidence basis for ultrasound-guided block characteristics: onset, quality, and duration. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(Sup2):S26–S35. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181d266f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapral S, Greher M, Huber G, Willschke H, Kettner S, Kdolsky R, Marhofer P. Ultrasonographic guidance improves the success rate of interscalene brachial plexus blockade. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33(3):253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal J M, Brull R, Chan V W, Grant S A, Horn J L, Liu S S, Mccartney C J, Narouze S N, Perlas A, Salinas F V, Sites B D, Tsui B C. The ASRA evidence-based medicine assessment of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia and pain medicine: Executive summary. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2010;35(Sup2):S1–S9. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181d22fe0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhoi S, Chandra A, Galwankar S. Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks in the emergency department. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3(1):82–88. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.58655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhofer P, Schrögendorfer K, Koinig H, Kapral S, Weinstabl C, Mayer N. Ultrasonographic guidance improves sensory block and onset time of three-in-one blocks. Anesth Analg. 1997;85(4):854–857. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S R, Chouinard P, Arcand G, Harris P, Ruel M, Boudreault D, Girard F. Ultrasound guidance speeds execution and improves the quality of supraclavicular block. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1518–1523. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000086730.09173.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams M S, Aziz M F, Fu R F, Horn J L. Ultrasound guidance compared with electrical neurostimulation for peripheral nerve block: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102(3):408–417. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhofer P, Schrögendorfer K, Wallner T, Koinig H, Mayer N, Kapral S. Ultrasonographic guidance reduces the amount of local anesthetic for 3-in-1 blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23(6):584–588. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(98)90086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anesthesiologists American Society of. Standards for Basic Anesthetic Monitoring. 2020

- Pehora C, Pearson A M, Kaushal A, Crawford M W, Johnston B, Group Cochrane Anaesthesia. Dexamethasone as an adjuvant to peripheral nerve block. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. . 2017;11:CD011770. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011770.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht E, Kern C, Kirkham K R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of perineural dexamethasone for peripheral nerve blocks. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(1):71–83. doi: 10.1111/anae.12823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alakkad H, Naeeni A, Chan V W, Abbas S, Oh J, Ami N, Ng J, Gardam M, Brull R. Infection related to ultrasound-guided single-injection peripheral nerve blockade: a decade of experience at Toronto western hospital. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40(1):82–84. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disinfection of ultrasound transducers used for percutaneous procedures: intersocietal position statement. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40(5):895–897. doi: 10.1002/jum.15653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound Guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-Care and Clinical Ultrasound Guidelines in Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(5):e27–e54. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.08.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for the use of transesophageal echocardiography (Tee) in the ed for cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(3):442–445. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebmann O, Price D, Mills C, Gardner R, Wang R, Wilson S, Gray A. Feasibility of forearm ultrasonography-guided nerve blocks of the radial, ulnar, and median nerves for hand procedures in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2006;48(5):558–562. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sites B D, Chan V W, Neal J M, Weller R, Grau T, Koscielniak-Nielsen Z J, Ivani G. The american society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine and the european society of regional anaesthesia and pain therapy joint committee recommendations for education and training in ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia: Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2010;35(Suppl 1):S74–S80. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181d34ff5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACGME ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education In Anesthesiology. ACGME-approved focused revision: June 13, 2020. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education In Anesthesiology. ACGME-approved focused revision. 2020

- Nagdev A, Dreyfuss A, Martin D, Mantuani D. Principles of safety for ultrasound-guided single injection blocks in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(6):1160–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodworth G, Maniker R B, Spofford C M, Ivie R, Lunden N I, Machi A T, Elkassabany N M, Gritsenko K, Kukreja P, Vlassakov K, Tedore T, Schroeder K, Missair A, Herrick M, Shepler J, Wilson E H, Horn J L, Barrington M. Anesthesia residency training in regional anesthesiology and acute pain medicine: a competency-based model curriculum. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2020;45(8):660–667. doi: 10.1136/rapm-2020-101480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodworth G E, Carney P A, Cohen J M, Kopp S L, Vokach-Brodsky L E, Horn J L, Missair A, Banks S E, Dieckmann N F, Maniker R B. Development and validation of an assessment of regional anesthesia ultrasound interpretation skills. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2015;40(4):306–314. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal J M, Barrington M J, Brull R, Hadzic A, Hebl J R, Horlocker T T, Huntoon M A, Kopp S L, Rathmell J P, Watson J C. The second ASRA Practice Advisory on neurologic complications associated with regional anesthesia and pain medicine: executive summary. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40:401–430. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal J M, Barrington M J, Fettiplace M R, Gitman M, Memtsoudis S G, Mörwald E E, Rubin D S, Weinberg G. The Third American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Practice Advisory on local anesthetic systemic toxicity: executive summary. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;43:113–123. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadsden J. Chapter 2. Local Anesthetics: Clinical Pharmacology and Rational Selection. In: Hadzic A, editor. Hadzic's Peripheral Nerve Blocks and Anatomy for Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia, 2nd. McGraw Hill; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Marhofer P, Halm J, Feigl G C, Schepers T, Hollmann M W. Regional Anesthesia and Compartment Syndrome. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2021;133(5):1348–1352. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran A A, Lee D, Fassihi S C, Smith E, Lee R, Siram G. A systematic review of the effect of regional anesthesia on diagnosis and management of acute compartment syndrome in long bone fractures. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020;46(6):1281–1290. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrie A, Sharma J, Mason M, Eng H Cruz. Regional Anesthesia Did Not Delay Diagnosis of Compartment Syndrome: A Case Report of Anterior Compartment Syndrome in the Thigh Not Masked by an Adductor Canal Catheter. Am J Case Rep. 2017;18:444–447. doi: 10.12659/ajcr.902708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganeshan R M, Mamoowala N, Ward M, Sochart D. Acute compartment syndrome risk in fracture fixation with regional blocks. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015210499. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]