Abstract

SETTING:

Kerala State, India, implemented decentralising reforms of healthcare institutions 25 years ago through transfer of administrative control and a sizeable share of the financial allocation.

OBJECTIVE:

To describe the main impacts of decentralisation in Kerala on local policy formulation, programme implementation and service delivery for sustainable health systems.

DESIGN:

This was part of a broader qualitative study on decentralisation and health in Kerala. We conducted 25 in-depth interviews and reviewed 31 government orders or policy documents, five related transcripts and five thematic reports from the main study.

RESULTS:

Liaising between health system and local governments has improved over time. A shift from welfare-centric projects to infrastructure, human resources and services was evident. Considerable heterogeneity existed due to varying degrees of involvement, capacity, resources and needs of the community. State-level discourse and recent augmentation efforts for moving towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) strongly uphold the role of local governments in planning, financing and implementation.

CONCLUSION:

The 25-year history of decentralised healthcare administration in Kerala indicates both successes and failures. Central support without disempowering the local governments can be a viable option to allow flexible decision-making consistent with broader system goals.

Keywords: local governments, health systems, qualitative study, SDG3, central augmentation, Kerala, India

Abstract

CONTEXTE :

L’État du Kerala, en Inde, a mis en œuvre des réformes de décentralisation des établissements de santé il y a 25 ans, en transférant le contrôle administratif et une part importante de l’allocation financière.

OBJECTIF :

Décrire les principaux impacts de la décentralisation au Kerala sur la formulation de politiques locales, la mise en œuvre de programmes et la prestation de services pour des systèmes de santé durables.

MÉTHODE :

Cette étude faisait partie d’une étude qualitative plus vaste sur la décentralisation et la santé au Kerala. Nous avons mené 25 entretiens approfondis et examiné 31 décrets ou documents de politique du gouvernement, cinq transcriptions connexes et cinq rapports thématiques de l’étude principale.

RÉSULTATS :

La liaison entre le système de santé et les gouvernements locaux s’est améliorée au fil du temps. Une réorientation des projets centrés sur le bien-être vers les infrastructures, les ressources humaines et les services était évidente. Une hétérogénéité considérable existe en raison des différents degrés d’implication, de capacité, de ressources et de besoins de la communauté. Le discours au niveau de l’État et les récents efforts d’augmentation en vue d’atteindre les objectifs de développement durable (SDG) de l’ONU soutiennent fortement le rôle des gouvernements locaux dans la planification, le financement et la mise en œuvre.

CONCLUSION :

Les 25 ans d’histoire de l’administration décentralisée des soins de santé au Kerala révèlent à la fois des réussites et des échecs. Un soutien central sans déresponsabiliser les gouvernements locaux peut être une option viable pour permettre une prise de décision flexible et cohérente avec les objectifs plus larges du système.

For several decades, Kerala State in India had attracted attention as a potential model for sustainable development, characterised by rapid improvement in infant and maternal mortality levels and better distribution of public goods by the late 1970s.1,2 However, deterioration of public sector health institutions and expanding privatisation of healthcare from the late 1980s onwards followed.3,4 In this context, the government implemented a series of reforms along with a popular movement called the ‘People’s Campaign for Decentralised Planning’5 – a unique exercise of decentralised administration, participatory planning and collaboration between sectors that impact on sustainable development. The government in 1996 decided to allocate 35–40% of the annual budget to local governments (LGs) with a framework for allocating a major share for social sectors.1 However, the initial enthusiasm of the grama sabhas (village forums for people’s participation in planning) waned after the first few years.6 The benefits to healthcare were limited, although generally positive.7 Nevertheless, this approach has sustained for over 25 years and survived several changes of government.

Globally, attention to the governance dimension of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including the role of LGs, is increasing.8,9 The SDG3 to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages” requires a primary healthcare approach encompassing equitable provisioning of promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative services.10 SDG3 requires collective action through a life course approach in order to address social determinants of health, and empower families and communities.11 This sentiment is reflected in Kerala’s recent efforts to provide comprehensive healthcare in which LGs “are perfectly positioned to act as coordinator and involve other departments, organisations”, while being “quintessential” in addressing the social determinants of health.12 In the present study, we sought to describe main impacts of decentralisation in Kerala on local policy formulation, programme implementation and service delivery in order to facilitate establishment of sustainable health systems.

METHODS

Design

In this qualitative study, we used document reviews, in-depth interviews (IDIs), secondary reviews of selected transcripts and reports from another ongoing study on decentralisation and health in Kerala, and reviews of field notes from visits to five primary-level health centres in four districts of the state.

Study setting

We engaged with key departments and stakeholders in the public sector relevant to the decentralised health-care system in Kerala.

Participant selection

Participant selection was iterative, covering politicians from different political regimes, senior bureaucrats from various sectors (local self-government, rural development, finance, health), and participants from the health system and LGs functioning at state level and local level. Five transcripts from the broader study were also selected as the narratives were relevant to our objective. A summary of IDIs conducted, and transcripts obtained is given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of in-depth interviews conducted and transcripts obtained

| Profile of the participant | Primary interview (I01–I25) | Review of available transcript (T1–T5) |

|---|---|---|

| Senior politicians | 2 | 1 |

| Senior bureaucratic level | 2 | 2 |

| Senior Programme Manager level | 11 | 1 |

| Peripheral implementation officers | 7 | 1 |

| Local government representatives | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 25 | 5 |

I = interview; T = transcript.

Document review

Documents from a period of 2012–2021 with key words ‘health system-Kerala’, ‘decentralisation and health’, ‘local self-government’ at the relevant Government websites of Kerala state were included. We also included recent initiatives such as ‘Aardram’, and ‘Nava Kerala mission’ as search terms.12 Documents were also obtained based on the leads from the interviewees. A total of 89 documents were shortlisted and 31 government orders were included initially, and 13 specific documents added later to facilitate explanation of themes emerging during the analysis (Supplementary Data).

Data collection and analysis

The interviews aimed at eliciting broad descriptions around decentralisation and health in Kerala, with probes into processes and key actors. We used the concept of principled engagement, a facet of collaborative governance used by Emerson et al., to identify contributions of the decentralised governance spaces, structures and processes to healthcare in the state.13 Principled engagement indicates a set of interactive processes driven by relevant stakeholders, comprising of discovery and definition of a need or issue leading on to deliberation and determination on actions to be taken.

Ethical concerns

Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethics committee of Health Action by People, Thiruvananthapuram, India (IEC No EC1/P02/Aug/2021/HAP). Informed recorded consent was obtained electronically at the start of each interview. Necessary steps were taken for removal of all identifiers from transcripts.

RESULTS

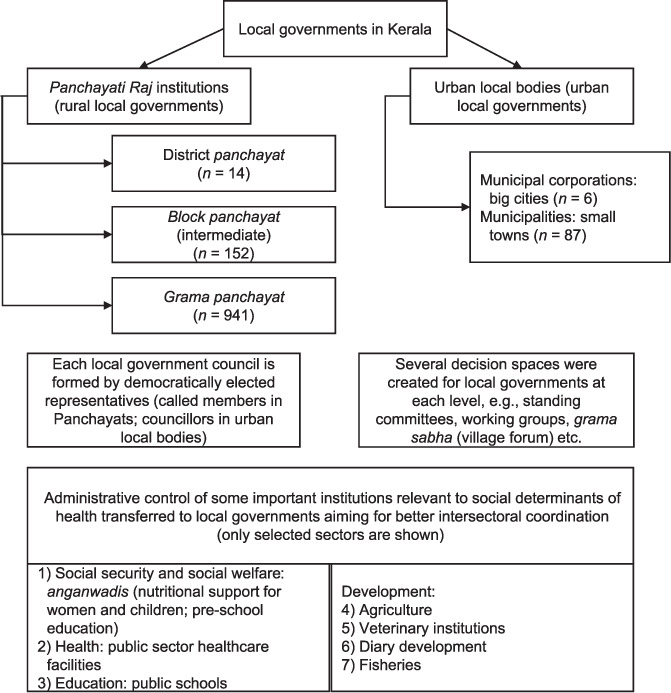

India’s 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendment Acts, 1992, gave constitutional status to LGs ‘in letter and spirit’. In India’s quasi-federal structure, states can formulate laws for functions where they have legislative power, and Kerala State drafted the Kerala Panchayati Raj Act, 1994, and the Kerala Municipalities Act, 1994, for rural and urban areas, respectively. Following the fiscal transfer of 35–40% of the State’s planning funds (kept aside for productive purposes) to LGs in 1996, amendments to the State Acts in 1999 led to the distribution of several functions, including government health centres and hospitals, among the urban LGs and the three tiers of the rural LGs. The ownership of the assets was not transferred but the responsibility of running the institutions were. The State government retained some power for formulating guidelines, monitoring, performance audit and other actions if warranted, with the need of approval from the State Legislature for major actions. The financial resource base of the LGs included funds received from the central Government of India, funds received from the State Government, own revenue generation in taxes and other sources such as licensing fees and loans, special development funds and other sources. Figure 1 shows the structure of the LG institutions in Kerala comprising tiered institutions governing multiple sectors supported through participatory spaces.

FIGURE 1.

Local government system in Kerala.

We report our results under three main themes: 1) challenges due to transition and resolutions in the health sector and LGs; 2) principled engagement, driven by positive sentiment and good practices; and 3) the balancing of local autonomy with state and national priorities and global goals. Sources of quotes are cited alphanumerically with numbers indicating serial number of the respective source, and alphabets indicating type of data source – T indicates transcripts from main study, I indicates in-depth interview, and L, A, R, and P indicate legislative and administrative, audit (financial), re-engineering (health institutions), and pandemic-related documents respectively (Supplementary Data).

Health sector and local governments: challenges due to transition and resolutions

The percentage of planning fund devolution was 1.9% in 1995–1996, 9.8% in 1996–1997 and 26.2% in 1997–1998. This process was rapid, with limited preparation or capacity-building; hence, often referred to as the ‘big bang’ approach. Roles of various stakeholders were not clear at first. We came across several orders (see Supplementary Data) where the State government had to step in to make role clarifications. The interview participants also dwelt considerably on these early challenges. Doctors and professional medical associations were repeatedly mentioned as being resistant to the transfer of administrative control of health institutions to LGs.

…the (health department) was completely opposed and for very specific reasons…established systems and hierarchies got upset. (Transcript 2)

However, one senior health professional pointed out that many of the champions of decentralisation were health department physicians and that there was an initial learning curve.

…at individual level it was not like that, many of them tried to utilise the opportunity, there were institutions that tried to do that in the beginning years itself…(but) we were not having clarity on what exactly is needed in the health sector as we have now. (Transcript 4)

Initially, many LGs resorted to one-time camps to utilise funds in a hurry before the end of the budget year. Financial audit reports from the first decade indicated low ability for fund utilisation (Audit 4), non-availability, or non-utilisation of technical help in project preparations, and resource wastage attributed to poor financial planning (Audit 3), and implementation, e.g., purchase of equipment without creating infrastructure, or obtaining required licenses (Audit 1) (Supplementary Data)

…the objective of providing employment to women in paramedical field and extension of laboratory services at affordable costs to rural population remained illusory (Audit Report 2003). (Audit 1)

The interviews indicated that later, technical collaboration improved, e.g., professional medical associations were working in tandem with LGs in some specific areas such as biomedical waste management and a scheme for equipment procurement, renting or maintenance for low cost.

Principled engagement driven by positive sentiment and good practices

Initial patterns of principled engagement focused primarily on welfare-centric projects. By the end of the first decade of decentralisation, a community-based participatory venture on primary palliative home care had been identified as best practice. This was institutionalised into a policy for all LGs in the state in 2008. The programme went on to obtain national approval and international recognition. A decentralised community-based rehabilitation (CBR) for developmental disorders, the BUDS (not an acronym) institutions, also emerged as a unique network of such institutions across the state.

Later, other aspects of healthcare delivery too received attention, as reflected in the Aardram mission, with increasing principled engagement in infrastructure, essential medicines, laboratory services, control of non-communicable diseases, and preventive and promotive services, alongside locally relevant interventions such as a traditional tribal shelter model home for expecting mothers. The Arogyakeralam Puraskaram (Arogyakeralam Award -Arogyakeralam is the name of the state unit of the National Health Mission unit of India), initiated in 2012, brought in a spirit of competitiveness and display of health achievements for LGs and learnings for the health department.

Possibly, in panchayats, increasing interest in health must be a consequence of the Arogya(keralam) puraskaram concept. (Transcript 3)

These are bringing visibility to good practices and helping to identify the gaps in the practices. (Transcript 4)

Balancing state and national priorities and global goals with local autonomy

LGs figured extensively in local actions for emerging concepts like UHC and SDG. Among two UHC projects in Kerala piloted in 2012, one involved LGs of three primary health centres (PHCs) in Thiruvananthapuram District for the planning, implementation and monitoring of services of the PHCs. This experience informed state-level experts on expanding the role of LGs in primary healthcare, which gained traction after 2016. When a new government came to power in Kerala in 2016, they unveiled the ‘Nava Kerala Karma Padhadhi’ (action plan for a new Kerala) in line with the SDGs. The state put in place 22 groups, comprising multiple stakeholders from across sectors, different levels of governance and civil society representatives for deliberations on the localisation of SDGs. A health sector-specific action, the ‘Aardram Mission’, was announced in February 2017, and aimed at many improvements, including re-engineering infrastructure, human resources and service provision at primary healthcare institutions in line with local needs and global goals. The templates provided by the Aardram mission were largely centrally driven. Several new services such as the SWAAS (Step wise approach to airway syndromes) programme for chronic obstructive airway disease and asthma were technocratically driven by health professionals.

Some study participants mentioned how the initial processes had the LGs in the forefront, but later there were attempts suggestive of elite capture, where a few persons in power would take decisions pertaining to the provision of public services instead of the LGs.

…every day, I quake at the thought of what next, what is it we are going to do to sabotage local autonomy, local decision making. (Transcript 2)

On the other hand, some participants justified the centrally driven approach, mentioning a mismatch between LG demands and population health needs relevant to Kerala such as addressing the social determinants of health.

…most vocal demand was … starting in-patient treatment (while out-patient services) would be running in inadequate space or without adequate facilities… Most of the public health programmes and health sector interventions are designed keeping in mind the nation as a frame. (Transcript 4)

A focus on local planning was also cited as lacking in foresight and insufficiently rapid to achieve the SDGs.

Today planning is very project oriented and beneficiary oriented … we could look at sustainable developmental goals and target of the goals and actually strive towards interventions that would result in the realisation of the goals which would be a multisectoral, multi-convergent … (Transcript 2)

The document review also reflected the lack of a broader perspective or long-term vision in LG health projects.

The guidelines further stipulated that every (local government unit) shall prepare a 5-year plan document comprising a shelf of projects. Audit noticed that … plan documents containing shelf of projects were not prepared. Due to non-preparation of the shelf of projects, various projects formulated in annual plan may not reflect felt needs at grassroots level visualised in Development Vision Document (Audit report 2015). (Audit 9)

Table 2 shows the codes and quotes illustrating principled engagement along with state support, and the need for the same due to heterogeneity of LGs. However, as shown in Figure 2, LG experiences and opinions were extensively considered at several stages in the processes. Proposals on upgrading each health centre had to be deliberated by the stakeholders at the respective LG level and in the participatory spaces of each LG. LGs were also provided with the authorisation to recruit human resources, something that was not permitted in the first two decades of decentralisation. Also, LGs continued to play important roles in all state-driven health interventions such as responding to emergencies like recent natural disasters, the Nipah virus outbreak and the COVID-19 pandemic in the state. Table 3 gives the main LG initiatives for COVID-19 control and response in Kerala.

TABLE 2.

Codes and indicative quotes on tenets of principled engagement

| Code | Quote |

|---|---|

| Trust and shared understanding–horizontal | I3 (LG elected representative): Being a representative of the people, it is very important to gain trust of the people. If they trust you, they will cooperate with your programmes… We all are one team; not different. That understanding of togetherness among hospital staff and elected representatives made this happen. |

| Trust and shared understanding–vertical | I19 (senior health official): To listen to them (LG representative) properly and get their feedback...and accurately and at the same time without diluting the key parameters and also by providing support to solve their problems. That was the kind of pattern that was followed in the district level and meetings. |

| Advocating LG support | I24 (senior administrative official): Only when we convinced the panchayat that this is a politically saleable agenda, they started looking at it. |

| LGs leverage/harness resources for health locally | I5 (LG elected representative): The <LG name> Administrative Committee has set aside INR2,758,685 for the development of the hospital. I18 (senior health official): Earlier if we ask the (State) Planning Board how much is spent for our health, then they said it’s about nearly 2%. Now we can’t tell like this, because (LGs) had spent crores.* |

*1 crore = 10 million.

I = interview; LG = local government.

FIGURE 2.

Engagement of local governments in state-level decision-making in line with global and national goals.

TABLE 3.

Summary of COVID-19 response from LGs in Kerala

| Date | Summary of content of order/guideline/report |

|---|---|

| 30 January 2020 | First of three cases imported from China, all three recovered by 20 February 2020 |

| 09 March 2020 | New wave of cases |

| 11 March 2020 | State health department directive to various departments (including local government) to take immediate action to control the spread of COVID-19 |

| Orders pertaining to COVID-19 response by local government units | |

| 14 March 2020 | Instructions regarding the measures to be taken by the local government bodies for prevention of COVID-19 in the state |

| 20 March 2020 | Detailed list of activities and responsibilities to be undertaken by local government bodies – awareness generation, ‘break the chain’ – social distancing, environmental hygiene, activities related to home isolation; harnessing all relevant committees; ensuring essential supplies; listing available facilities and resources for prevention and control measures; vulnerable groups; templates for data collection, etc. |

| 25 March 2020 | Further instructions pertaining to primary health centres (PHCs) – urgently meeting medicine requirements, recruitment of contract staff, travel PHC staff during lockdown, uninterrupted medicine for patients with chronic conditions, mental health support, disinfection, youth volunteer mobilisation for food material/medicine distribution |

| 26 March 2020 | Formation of community kitchens under the auspices of Kudumbashree units (women’s self-help groups for poverty alleviation) in collaboration with local administration |

| Kerala Development Report 2021 | |

| 30 June 2020 | 1374 community kitchens |

| 9.5 million food parcels (over 8.2 million were given free for needy, especially migrant workers, the elderly, palliative care patients, stranded persons, people in quarantine, destitute persons, etc.) 86,470 person-days of cleaning and disinfection activities Local governments also supported accommodation, and other essential support to internal migrant workers and helped greatly in setting up COVID-19 First-Line Treatment Centres (CFLTC) – 1,437 CFLTCs and 1,20,832 beds had been set up | |

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative study, we explored notable contributions involving principled engagement of LGs to improvements in the health system in Kerala, India. Success of principled engagement in collaborative governance needed legitimacy, resources and institutional arrangements. Initial ascribable contributions were welfare-centric, focused on palliative care and rehabilitation. After such possibly emotionally driven welfare-centric investment decisions, LGs seem to have moved to investments for health system improvement, focusing on more comprehensive patient-friendly service provision. The established community-based palliative and rehabilitative efforts and emerging attempts at expanding preventive, promotive and curative services indicate the contributions of the decentralised approach in Kerala for SDG3 – health and wellbeing for all.

Governable decision spaces, with potential for popular participation

Kerala’s experiences with decentralisation are comparable to experiences in other low- and middle-income settings. The Philippines had attempted extensive decentralisation of health systems about 30 years ago and faced several challenges due to fragmentation of the pre-existing system without local capacity for improvement, limited community participation, local elite capture and the relative failure of capacity-building measures.14 However, wherever there was a widening of decentralised decision space, the impact of decentralisation was deemed positive. Our findings suggest a moderate decision space according to the framework used by Kigume and Maluka in Tanzania.15 The utility of the decision space was evident in the Aardram health centre re-engineering activity, as well as the COVID-19 response in the state. The Kerala approach has attempted to widen local decision-making spaces without too much fragmentation that may affect the health system. The transfer of control to Human Resources for Health is partial in Kerala. But platforms like the Hospital Management Committee (health system side – the system to be governed), and the Health Working Group and Health Standing Committee (LG side – the governing system) suggest opportunities for sufficient interaction to facilitate governability, as explained by Kooiman.16

Central augmentation and multi-level and multi-sectoral coordination

Unevenness is another characteristic of decentralised systems, particularly where localisation of SDGs has been attempted, as in Uganda, Mozambique, Kenya and South Africa.17 In Kerala, state efforts to enable accreditation of health centres with the National Quality Assurance Standards (NQAS) was a step towards the standardising of services to bring reasonable uniformity.18 This indicates some role for centralised functioning and leadership, but was accepted by LGs probably because decisions had local-level political utility. This could be termed central augmentation rather than re-centralisation, as the power and flexibility of LGs are not compromised. Also, in many SDG initiatives in other regions, there were gaps in explicit linkages of health SDGs with non-health SDGs.19 Decentralised models like the Kerala model may help overcome this. As recommended by Guha and Chakrabarti, vertical and horizontal intergovernmental relationships, bureaucratic environment, people’s participation, harmonisation of interests, ability of LGs to create and harness own revenues are important for the achievement of SDGs through decentralisation.20 Localisation of developmental goals in local government plans is better for integrating economic, social and environmental dimensions than localisation in programmes within different development sectors, given that sectors usually exist within ‘silos’.21 Also, the currency of localisation is trust.22 The decentralisation approach in Kerala may help build trust and faith in the health system through its participatory approaches while aiming for alignment with the SDGs.23

Limitations

We were unable to delineate empirical evidence of benefits in terms of health outcomes as these are influenced by multiple demographic, epidemiological, political and economic factors with system-wide effects. A recent systematic review on decentralisation and health system performance and outcomes reported similar issues across most studies on decentralisation and health.24

Our findings are limited to qualitative stakeholder perspectives alone, and we did not match the reported initiatives against actual or perceived community needs, or quantitative trends reflecting sociopolitical context or economic value. However, decentralisation remains a complex process, and we feel that our findings may help to inform elements, principles and methods of future research in this area. Risks like policy capture or replacement of one form of paternalism with another will always be present in decentralised systems, and ultimately, sustainability will depend on societal values, institutions and procedural fairness.25 Further analysis is required in these directions, especially from low- and middle-income regions such as Kerala.

CONCLUSION

We tried to qualitatively describe successful processes with principled engagement for collaborative governance in the decentralised health system in Kerala. Beneficiaries are yet to emerge as change makers in the planning process, but spaces and processes that were created have survived for over two decades, with good performance in some places and specific domains. Foregrounding of specific programmes, such as community-owned palliative and rehabilitative care have happened, and are now being scaled up beyond the state. The ability of better-off regions to deliver better-quality services, and thus create heterogeneity is a risk associated with decentralisation. Decentralisation happens to be a messy process in general in many low- and middle-income countries. Localisation of SDGs can be expected to be uneven, partly because of different needs, resources and capacities of local stake-holders. In such situations, providing sufficient central support without disempowering local decision-making players and processes may be the way forward.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The manuscript was prepared from one of the sub-themes of the project Local Government and Health in Kerala, implemented by Health Action by People, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. The authors thank Health Systems Transformation Platform for supporting this research and the Local Self Government Department of the Government of Kerala for granting permission to undertake the study. The funders had no role in data collection and analysis or preparation of the manuscript. RA was independently supported by Health Action by People, Thiruvananthapuram, India, through a separate project.

Funding Statement

The authors thank Sir Ratan Tata Trust for its financial contribution which made this research possible.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Veron R. The “new” Kerala model: lessons for sustainable development. World Development. 2001;29(4):601–617. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franke RW, Chasin BH. Kerala State, India: radical reform as development. Int J Health Serv. 1992;22(1):139–156. doi: 10.2190/HMXD-PNQF-2X2L-C8TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mencher JP. The lessons and non-lessons of Kerala: agricultural labourers and poverty. Economic and political weekly. 1980;15(41–43):1781–1802. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kutty VR. Historical analysis of the development of healthcare facilities in Kerala State, India. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15(1):103–109. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elamon J, Franke RW, Ekbal B. Decentralization of health services: the Kerala People’s Campaign. Int J Health Serv. 2004;34(4):681–708. doi: 10.2190/4L9M-8K7N-G6AC-WEHN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Platteau JP, Abraham A. Participatory development: where culture creeps in. In: Rao V, Walton M, editors. Culture and public action. Stanford, CA, USA: Stanford University Press; 2004. pp. 210–233. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varatharajan D, Thankappan R, Jayapalan S. Assessing the performance of primary health centres under decentralized government in Kerala, India. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(1):41–51. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) A vision for primary healthcare in the 21st century: towards universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Immler NL, Sakkers H. The UN Sustainable Development Goals going local: learning from localising human rights. Int J Hum Rights. 2022;26(2):262–284. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuruvilla S, et al. A life-course approach to health: synergy with sustainable development goals. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96(1):42–50. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.198358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Towards a global action plan for healthy lives and well-being for all: uniting to accelerate progress towards the health-related SDGs. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health Mission Aardram. Thiruvananthapuram, India: Government of Kerala; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emerson K, Nabatchi T, Balogh S. An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J Public Adm Res Theory. 2012;22(1):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liwanag HJ, Wyss K. What conditions enable decentralization to improve the health system? Qualitative analysis of perspectives on decision space after 25 years of devolution in the Philippines. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kigume R, Maluka S. Decentralisation and health services delivery in 4 districts in Tanzania: how and why does the use of decision space vary across districts. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2019;8(2):90–100. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kooiman J. Exploring the concept of governability. J Comp Pol Anal Res Pract. 2008;10(2):171–190. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy PS. Localising the sustainable development goals (SDGs): the role of local government in context. Afr J Public Affairs. 2016;9(2):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Health Mission National Quality Assurance Standards (NQAS) Thiruvananthapuram, India: Government of Kerala; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddiqi S, et al. Global strategies and local implementation of health and health-related SDGs:lessons from consultation in countries across five regions. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(9):e002859. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guha J, Chakrabarti B. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through decentralisation and the role of local governments: a systematic review. Commonwealth J Local Governance. 2019;22:6855. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton S, Pencheon D, Squires N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and their implementation: a national global framework for health, development and equity needs a systems approach at every level. Br Med Bull. 2017;124(1):81–90. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldx031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider H, et al. The governance of local health systems in the era of Sustainable Development Goals: reflections on collaborative action to address complex health needs in four country contexts. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(3):e001645. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nambiar D, et al. Monitoring Universal Health Coverage reforms in primary healthcare facilities: creating a framework, selecting and field-testing indicators in Kerala, India. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0236169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0236169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dwicaksono A, Fox AM. Does decentralization improve health system performance and outcomes in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review of evidence from quantitative studies. Milbank Q. 2018;96(2):323–368. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landwehr C, Klinnert D. Value congruence in healthcare priority setting:social values, institutions and decisions in three countries. Health Econ Policy Law. 2015;10(2):113–132. doi: 10.1017/S1744133114000437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]