Abstract

The functionality of HMA3 is a key determinant controlling Cd accumulation in the shoots and grains of plants. Wild relatives of modern crop plants can serve as sources of valuable genetic variation for various traits. Here, resequencing of HMA3 homoeologous genes from Aegilops tauschii (the donor of the wheat D genome) was carried out to identify natural variation at both the nucleotide and polypeptide levels. HMA3 homoeologs are highly conserved, and 10 haplotypes were revealed based on 19 single nucleotide polymorphisms (eight induced single amino acid residue substitutions, including 2 altered amino acids in transmembrane domains) in 80 widely distributed Ae. tauschii accessions. The results provide genetic resources for low/no Cd concentration wheat improvement.

Introduction

The low cadmium (Cd) concentration trait in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L., AABBDD, 2n = 6x = 42) grains is important in terms of food safety because bread wheat is a crucial source of calories, accounting for 20% of calories for human consumption and feeding more than 35% of the world’s population [1]. Cadmium can accumulate in the human body over time as a result of the ingestion of food containing Cd, leading to a risk of chronic toxicity with excessive intake [2]. Furthermore, Cd is not phytotoxic at the low concentrations that are of concern for human health [3]. Therefore, reducing Cd accumulation in wheat grains is essential for food safety and human health issue.

The tonoplast transporter HMA3 (P1B-type of heavy metal ATPases 3) plays an important role in the transport and homeostasis of metals in plants [4]. Loss of function of HMA3 leads to decreased Cd sequestration in the roots but greatly increased translocation of Cd from roots to shoots in Arabidopsis thaliana and rice [5–8]. In contrast, overexpression of OsHMA3 increases Cd sequestration in the roots and Cd tolerance, and markedly decreases Cd translocation to the shoots and Cd concentration in the grains (decreased Cd concentration by 94–98%) [9, 10]. Overexpression of rice OsHMA3 in wheat also greatly decreases Cd translocation from the roots to the shoots and Cd accumulation in wheat grains [11]. Recently, TdHMA3-B1 (Cdu-B1) was identified as a QTL located on the long arm of chromosome 5B that explains >80% of the phenotypic variation in grain Cd concentration in tetraploid durum wheat (T. durum, AABB, 2n = 4x = 28) [12–16]. Cd associated SNP markers on 5AL were identified in a region homoeologous to the TdHMA3-B1 locus on 5BL in durum wheat, which explained 12%-19% of variation in grain Cd concentration depending on the environment in bread wheat [17]. A 17-bp duplication in the first exon that creates two alternative alleles, TdHMA3-B1a (the functional allele being able to transport Cd into the vacuoles with low grain Cd) and TdHMA3-B1b (the nonfunctional allele being inactive with high grain Cd), in durum wheat [16]. In addition, the high-cadmium allele is widespread in durum wheat cultivars but undetected in wild emmer accessions, the frequency of the high-cadmium allele are increased from domesticated emmer accessions to modern durum wheat [16]. These studies indicate that the functionality of HMA3 is a key determinant controlling Cd accumulation in the shoots and grains of plants and that wild relatives of modern crop plants can serve as sources of valuable genetic diversity to develop low/no Cd concentration cultivars.

Aegilops tauschii (DD, 2n = 2x = 14), a wild relative of wheat, is the D genome progenitor of hexaploid wheat [18–21]. It has been shown to be an effective medium for transferring valuable genetic variation from Ae. tauschii to common wheat [22–24]. The addition of the D genome changed wheat from tetraploid to hexaploid. Indeed, hexaploid wheat became a major food crop worldwide only after the addition of the D genome [25]. It can be seen that their ability to spread widely may be related to the great adaptability brought by the D genome, which also explains why they have many agronomic valuable characteristics, including tolerance to drought [26], salt [27], low phosphorus [28] and extreme environments. Besides that, The Cd-tolerant Ae. tauschii accessions were indentified by Genome-wide association analysis, which may be used as germplasm resources of wheat breeding for no or low Cd content [29]. Here, we report a survey of the natural variation in potential Ae. tauschii germplasm for HMA3 homoeologous sequences across a diverse geographical distribution and provide genetic resources for low/no Cd concentration wheat improvement.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

The Ae. tauschii germplasm panel consisted of 80 accessions (Table 1). The materials were planted at the Wenjiang Experimental Station of Sichuan Agricultural University in Chengdu, China. All materials were stored at the Triticeae Research Institute, Sichuan Agricultural University.

Table 1. Information on Ae. tauschii samples used in this study.

| Lines | Origin | Latitude | Longitude | Sublineage | Taxon | Haplotype | GenBank Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI603241 | Azerbaijan | 40.53 | 48.92 | 2W | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| CIae28 | Iran | 37.98 | 45.02 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| AS68 | Iran | NA | NA | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| IG48556 | Tajikistan | 39.47 | 67.83 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| PI554315 | Turkey | 38.42 | 43.30 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| PI554309 | Turkey | 38.46 | 42.45 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| PI554312 | Turkey | 38.42 | 43.30 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| PI560753 | Turkey | 37.48 | 43.53 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| PI603220 | Western Asia | NA | NA | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| CIae71 | NA | NA | NA | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| AS84 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| PI499263 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| KU2615 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| DV148 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| AE251 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| KU2082 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D1 | OL739674 |

| DV288 | Afghanistan | 37.23 | 70.29 | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| DV306 | Azerbaijan | 40.58 | 48.73 | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| PI603240 | Azerbaijan | 40.63 | 48.62 | 2W | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| CIae15 | Iran | 35.76 | 52.78 | 2W | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| PI603226 | Iran | 36.58 | 53.50 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| PI603250 | Iran | 36.67 | 53.58 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| PI554311 | Turkey | 38.42 | 43.30 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| IG123880 | Uzbekistan | 41.24 | 71.65 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| CIae72 | NA | NA | NA | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| DV634 | NA | NA | NA | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| AL370 | Iran | 38.24 | 48.28 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| KU2078 | Iran | 36.85 | 54.53 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| AE1602 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| AE425 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| KU2161 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D10 | OL739683 |

| DV140 | Afghanistan | 32.38 | 67.30 | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D2 | OL739675 |

| PI431601 | Azerbaijan | 40.50 | 47.00 | 2W | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D2 | OL739675 |

| PI486273 | Turkey | 40.15 | 43.37 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D2 | OL739675 |

| PI511365 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D2 | OL739675 |

| PI560534 | Turkey | 37.58 | 43.73 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D3 | OL739676 |

| PI486271 | Turkey | 38.92 | 43.60 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D3 | OL739676 |

| PI220642 | Afghanistan | 35.72 | 64.90 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| PI511367 | Afghanistan | 34.53 | 69.18 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| DV189 | Afghanistan | 35.11 | 63.43 | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| DV169 | Afghanistan | 35.99 | 64.87 | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| DV185 | Afghanistan | 35.74 | 63.73 | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| DV327 | Armenia/Georgia | 41.76 | 44.76 | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| DV328 | Georgia | 42.02 | 44.31 | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| CIae14 | Iran | 36.80 | 55.10 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| IG47234 | Pakistan | 30.50 | 67.00 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| AL7/79 | Turkmenistan | 39.21 | 62.25 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| IG48544 | Uzbekistan | 40.08 | 67.58 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| IG48570 | Uzbekistan | 40.88 | 71.10 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| IG47232 | Pakistan | 30.38 | 67.00 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| IG46670 | Pakistan | 29.93 | 66.62 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| IG48567 | Uzbekistan | 40.57 | 71.70 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| DV326 | Armenia/Georgia | 41.76 | 44.76 | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| AE964 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| AE841 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D4 | OL739677 |

| CIae12 | Iran | 36.70 | 55.12 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D5 | OL739678 |

| PI560756 | Turkey | 37.70 | 43.97 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D5 | OL739678 |

| KU2094 | Iran | 36.59 | 52.09 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D5 | OL739678 |

| AL8/78 | Armenia | 40.30 | 44.66 | 2W | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D6 | OL739679 |

| DV2917 | Azerbaijan | 38.97 | 48.34 | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D6 | OL739679 |

| CIae8 | Iran | 36.67 | 53.40 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D6 | OL739679 |

| PI542277 | Turkey | NA | NA | 2W | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D6 | OL739679 |

| PI486267 | Turkey | 37.27 | 44.55 | 2W | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D6 | OL739679 |

| PI574469 | India | NA | NA | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D6 | OL739679 |

| AE224 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D6 | OL739679 |

| KU2126 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D6 | OL739679 |

| DV331 | Afghanistan | 34.59 | 68.95 | NA | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D7 | OL739680 |

| PI428564 | Azerbaijan | 40.50 | 47.00 | 2W | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D7 | OL739680 |

| PI603242 | Turkmenistan | 38.48 | 56.30 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D7 | OL739680 |

| PI554317 | Turkey | 38.42 | 43.30 | 1W | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D7 | OL739680 |

| PI603230 | Azerbaijan | 40.50 | 47.00 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D8 | OL739681 |

| PI603253 | Iran | 36.88 | 50.69 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D8 | OL739681 |

| PI511381 | Iran | 36.67 | 53.58 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D8 | OL739681 |

| DV198 | Iran | 36.82 | 54.29 | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D8 | OL739681 |

| K901/75 | NA | NA | NA | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D8 | OL739681 |

| AS2406 | Iran | NA | NA | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D8 | OL739681 |

| AE430 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D8 | OL739681 |

| AE1548 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D8 | OL739681 |

| PI317394 | Afghanistan | 34.95 | 63.22 | 1E | ssp. tauschii | Hap-D9 | OL739682 |

| PI349037 | Azerbaijan | 40.50 | 47.00 | 2E | ssp. strangulata | Hap-D9 | OL739682 |

Accessions prefixed with either PI and CIae were provided by the USDA-ARS, those with KU by the Japanese National BioResource Project (NBRP), those with IG by the International Center for Agricultural Research in Ardid Areas (ICARDA), those with TA by Kansas State University, those with either K, AL and RL by UC Davis, and those with AS by Sichuan Agricultural University Triticeae Research Institute. Genotype (Sublineage) were previously published [30].

PCR primer design, amplification and amplicon sequencing

Genomic DNA from plant materials was extracted from young leaves using a plant genomic DNA kit (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd.). The PCR primers were designed according to the sequences of TaHMA3-D1 (KF683298.1) and its homologous sequence in the EnsemblPlants database (http://plants.ensembl.org/Aegilops_tauschii/Info/Index) using DNAMAN version 6.0 (Lynnon Biosoft, Quebec, Canada) software. The HMA3-D1 sequence of Ae. tauschii was amplified as two separate overlapping fragments using the primers TaHMA3-1 F (5’-TTGCTTGCAGCTTGTAGCTC-3’) and TaHMA3-1 R (5’-CATGTCGACGCTGAACTCCC-3’) for fragment 1 (1706-bp amplicon) and primers TaHMA3-2 F (5’-AGAGCAAGTCCAAGACGCAG-3’) and TaHMA3-2 R (5’-AGTCTCCTTTGTATTTTGCGCC-3’) for fragment 2 (1992-bp amplicon). PCR amplification was performed using a PTC-200 Thermocycler (MJ Research, Watertown, MA, USA). Each PCR was performed in a volume of 50 μL containing 200 ng of template DNA, 200 μmol/L of each dNTP, 100 μmol/L of each primer, 5.0 μL of 10 ×PCR buffer, 1 U ExTaq DNA polymerase with high fidelity (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), and double-distilled (dd) H2O. The cycling conditions for fragment 1 amplification were initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, annealing at 58°C for 40 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The cycling conditions for fragment 2 were initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, annealing at 61°C for 40 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified products were separated on a 1.0% agarose gel in 1×TAE buffer (0.04 mol/L Tris base, 0.02 mol/L acetic acid, and 1.0 mmol/L EDTA) followed by staining with ethidium bromide. The PCR products were sequenced directly by Qingke (Chengdu, China).

Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignments at both the nucleotide and predicted polypeptide levels were performed using DNAMAN v6.0 software (Lynnon Biosoft, Quebec, Canada). The transmembrane domains were predicted using TOPCONS (https://topcons.net/pred/result/rst_yGKZeW/). Phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the neighbor-joining method using MEGA v11 software [31]. Bootstrap analysis was based on 1,000 replicates.

Results and discussion

Results

Ae. tauschii HMA3-D1: Nucleotide sequence polymorphism

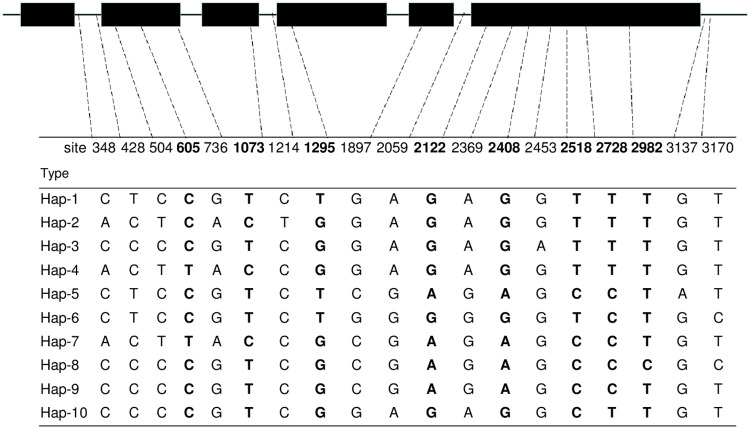

The full set of wheat HMA3 homoeologous sequences from 80 Ae. tauschii accessions was deposited in GenBank with accession numbers OL739674 to OL739683 and revealed 10 haplotypes (Table 1). All homoeologs comprised six exons and five introns, compared with TaHMA3-D1 (KF683298.1). The most common haplotype (Hap-4) was present in 18 accessions of ssp. tauschii, followed by Hap-1 (16 accessions) and Hap-10 (15 accessions). Both Hap-6 and Hap-8 were present in 8 accessions. Hap-2 and Hap-7 were each present in 4 accessions. Hap-3 and Hap-9 were present in 2 accessions. Finally, Hap-5 was present in 3 accessions. Exon variation involved thirteen single nucleotides, and eight of these thirteen polymorphisms induced an altered peptide sequence; the variation in the intron and downstream regions involved 4 single nucleotide substitutions and 2 polymorphisms, respectively (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Haplotype variation of HMA3-D1 in the 80 accessions of Ae. tauschii.

Exons are depicted as a black box. Exonic polymorphisms generating a changed peptide are indicated in bold.

In terms of geographical distribution (Table 1), most haplotypes were found in Turkey (8 haplotypes including Hap-1 to -3, -5 to -7, and -10) and Azerbaijan (8 haplotypes including Hap-1 to -2, -6 to -10), followed by Iran (6 haplotypes including Hap-1, -4 to -6, -8 and -10) and Afghanistan (5 haplotypes including Hap-2, -4, -7, -9 and -10). It is interesting that Turkey and Azerbaijan cover 9 of the ten haplotypes, except the most common haplotype (Hap-4).

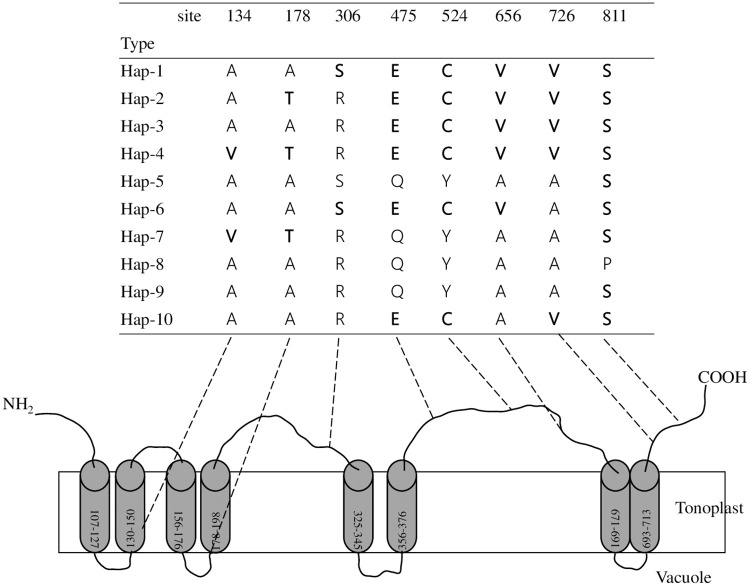

Ae. tauschii HMA3-D1: Peptide sequence polymorphism

At the polypeptide sequence level, the 10 haplotypes from Ae. tauschii collapsed into ten distinct polypeptides. Polypeptide sequence alignment of HMA3 homoeologs is shown in Fig 2. The predicted protein of TaHMA3-D1 (AIA57682.1) in CS was indistinguishable from Hap-8. Their structural organization shared conserved transmembrane domains (TM1 to 8, boxed in Fig 2). Two of the eight altered amino acids were found in transmembrane domains. One was different from that of bread wheat, tetraploid wheat, barley, rice, maize, and A. thaliana at position 134, from A to V, in TM2, which was present in Hap-4 and -7 of Ae. tauschii, while the other was an A to T change at position 178 in TM4 in Hap-2, -4 and -7 (Fig 2). The remaining 6 altered peptide sequences were at position 306, from R to S, in Hap-1 and -6; position 475, from Q to E, and position 524, from Y to C, in Hap-1 to -4, -6 and -10; position 656, from A to V, in Hap-1 to -4 and -6; position 726, from A to V, in Hap-1 to -4 and -10; and position 811, from P to S, in Hap-1 to -10, except for Hap-9 (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Polypeptide sequences of HMA3-D1 in the 80 accessions of Ae. tauschii.

Polymorphisms generating a changed peptide are indicated in bold compared with Hap-8 (TaHMA3-D1). Transmembrane domains were predicted by TOPCONS.

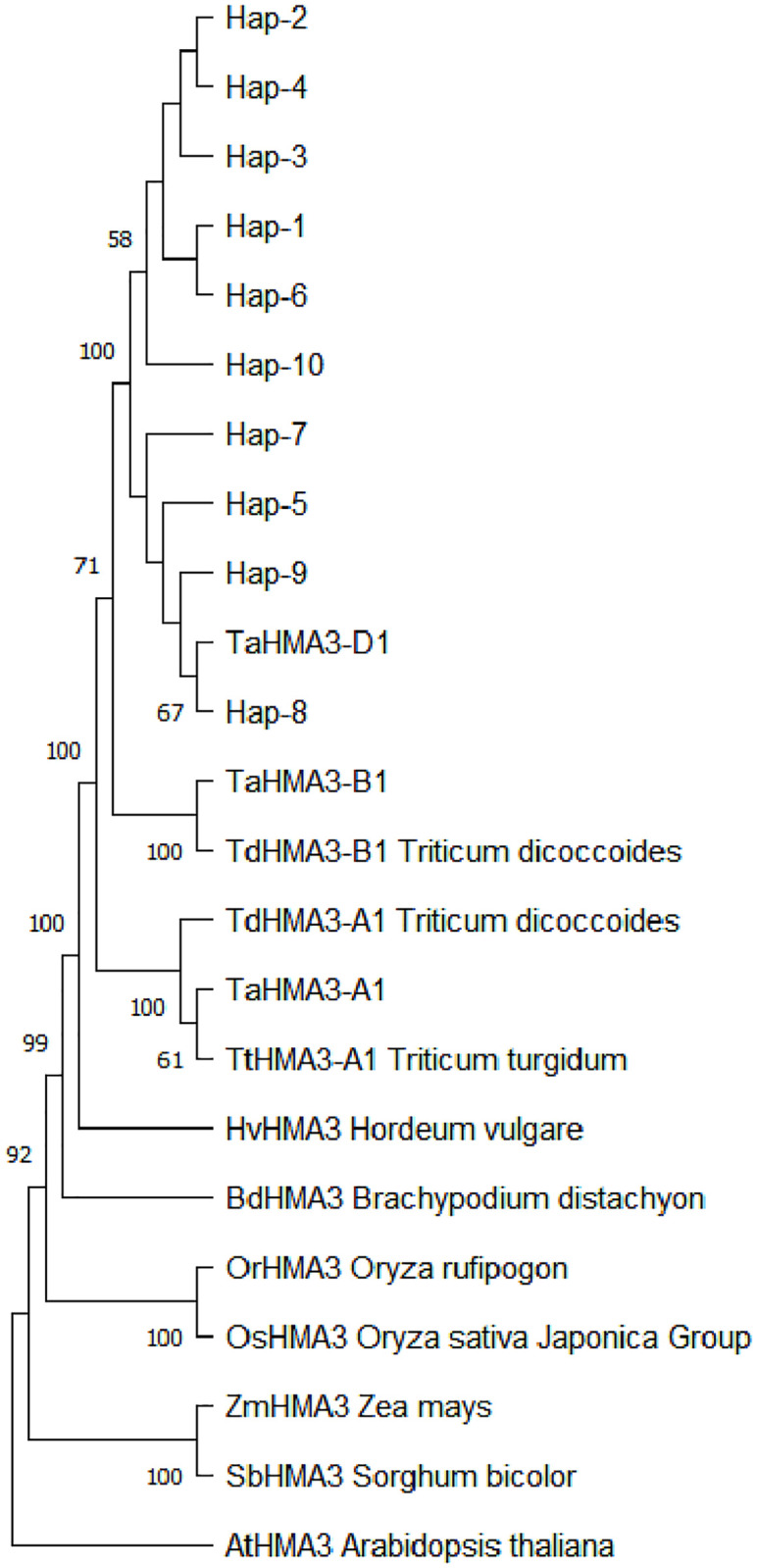

HMA3-D1 homoeolog phylogeny

The phylogeny of the protein sequences of wheat HMA3 homoeologs is shown in Fig 3. Each of the three homoeologs from Ae. tauschii and Triticum formed a distinct clade. The homoeologs from the B and D genome clades appeared to be more closely related to one another than to the homoeologs from the A genome clade. Within the homoeologs from the D genome clade, two subgroups were recognizable: one comprised the Ae. tauschii sequences Hap-1 to -4, -6 and -10, and the other comprised the D genome sequences present in Ae. tauschii Hap-5, -7 to -9 and T. aestivum. The cluster of cereal sequences, including Ae. tauschii, Triticum, Hordeum, Brachypodium, Oryza, Zea and Sorghum, showed that they were phylogenetically closely related to one another. The HMA3 homologous sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana (AT4G30120) as the outgroup.

Fig 3. Phylogeny of A. thaliana, Brachypodium, rice, maize, barley, bread wheat cv. ‘Chinese Spring’, tetraploid wheat and Ae. tauschii HMA3 homoeologs obtained using the neighbor-joining method.

Only bootstrap values (%) >50%, as calculated from 1,000 replicates, are shown.

Discussion

Previous studies showed that OsHMA3 from a low Cd-accumulating cultivar limits the translocation of Cd from the roots to the above ground tissues by selectively sequestrating Cd into the root vacuoles [5, 32]. Allelic variations in the coding sequences of this gene were responsible for the loss of function, such as a mutation at the 80th amino acid (R80H) [5], a mutation at the 380th amino acid in TM6 from Ser to Arg [7], a 153-bp (51-aa) deletion [6], and 14-aa deletion [8]. A strong association between the BrHMA3 haplotypes and the Cd translocation phenotypes was also found, and variation in the BrHMA3 coding sequence is a key determinant of Cd translocation to and accumulation in the leaves of B. rapa [33]. In durum wheat, the TdHMA3-B1 (Cdu-B1) gene explained approximately 80% of the variation in grain Cd concentration [14–16]. The 17-bp duplication was responsible for the loss of function [16]. The Cd-associated SNPs identified in bread wheat are in a region of 5AL that is homoeologous to the region of Cdu-B1 in durum [17].

The diverse Ae. tauschii offers a valuable gene pool for Cd tolerance [29]. Here, 80 resequenced HMA3 homoeologs of Ae. tauschii were widely distributed and structured into six exons, and their sequences were highly homologous with one another (Fig 1). The sequence variation between them was concentrated more in the exonic than in intronic DNA (Fig 1). Ten haplotypes were revealed by these sequences and collapsed into ten distinct polypeptides (Fig 2). The structural organization of the HMA3 homoeologs shared conserved transmembrane domains (TM1 to 8), where 6 of the eight altered amino acids were involved in the interval between transmembrane domains, and the remaining 2 were prospectively involved in TM1 and TM4. Furthermore, variation in the BrHMA3 coding sequence is a key determinant of Cd translocation to and accumulation in the leaves of B. rapa [32]. Mutation at the 80th amino acid (R80H) in front of TM1 [5] and mutation in the 380th amino acid in TM6 from Ser to Arg [6] altered OsHMA3 function (S1 Fig). Moreover, the bread wheat cultivars JiMai22 and HeNong6425 and the US wheat cultivar Fielder showed 3–7 times higher Cd translocation than the rice cv. Nipponbare. Overexpression of rice OsHMA3 in wheat greatly decreases the Cd accumulation in grains [11]. Therefore, the altered peptide sequence revealed from Ae. tauschii has potential value for low/no Cd concentration wheat breeding.

Ae. tauschii has been taxonomically subdivided on the basis of its morphology into ssp. tauschii and ssp. strangulata [34–36]. It is widely accepted that ssp. strangulata is the source of the D genome in wheat [37–44]. Within the homoeologs from the D genome clade, two subgroups were recognizable: one comprised the Ae. tauschii sequences Hap-1 to -4, -6 and -10, and the other comprised the D genome sequences present in Ae. tauschii Hap-5, -7 to -9 and T. aestivum (Fig 3). The most common haplotype Hap-4, which has 7 altered amino acids compared to TaHAM3-D1 from CS, was present only in ssp. tauschii (S1 Fig). Effective introduction and utilization of genetic resources present in Ae. tauschii, especially ssp. tauschii possessing high sequence variations, are a pressing need in wheat breeding and improvement.

Supporting information

Variations compared to TaHMA3-D1 are indicated. Transmembrane domains (TM1-8) predicted by TOPCONS are shown in boxes.

(RTF)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yaxi Liu (Sichuan Agricultural University) for providing Ae. tauschii lines.

Data Availability

All sequences are available from the GenBank database (accession number(s) OL739674 to OL739683).

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2022ZDZX0014) and the Key Research and Development Program of Sichuan Province (2021YFYZ0002), China. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Brenchley R, Spannagl M, Pfeifer M, Barker G, Amore R, Allen A, et al. Analysis of the bread wheat genome using whole-genome shotgun sequencing. Nature. 2012;491(7426):705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature11650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant CA, Clarke JM, Duguid S, Chaney RL. Selection and breeding of plant cultivars to minimize cadmium accumulation. Sci Total Environ. 2008;390: 301–310. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.10.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaney RL. Health risks associated with toxic metals in municipal sludge. In: Bitton G, Damro BL, Davidson GT, Davidson JM, editors. Sludge health risks of land application. Ann Arbor, MI, USA: Ann Arbor Science Publisher; 1980. p.59–83. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams LE, Mills RF. P1B-ATPases-an ancient family of transition metal pumps with diverse functions in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ueno D, Yamaji N, Kono I, Huang CF, Ando T, Yano M, et al. Gene limiting cadmium accumulation in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:16500–16505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005396107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyadate H, Adachi S, Hiraizumi A, Tezuka K, Nakazawa N, Kawamoto T, et al. OsHMA3, A P1B-type of ATPase affects root-to-shoot cadmium translocation in rice by mediating efflux into vacuoles. New Phytol. 2011;189(1):190–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan J, Wang P, Wang P, Yang M, Lian X, Tang Z, et al. A loss-of-function allele of OsHMA3 associated with high cadmium accumulation in shoots and grain of Japonica rice cultivars. Plant Cell Environ. 2016;39:1941–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sui F, Zhao D, Zhu H, Gong Y, Tang Z, Huang XY, et al. Map-based cloning of a new total loss-offunction allele of OsHMA3 causes high cadmium accumulation in rice grain. J Exp Bot. 2019;70:2857–2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasaki A, Yamaji N, Ma J. Overexpression of OsHMA3 enhances Cd tolerance and expression of Zn transporter genes in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2014;65, 6013–6021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu C, Zhang L, Tang Z, Huang X, Ma J, Zhao F. Producing cadmium-free Indica rice by overexpressing OsHMA3. Environ Int. 2019;126:619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Gao C, Chen C, Zhang W, Huang X, Zhao F. Overexpression of rice OsHMA3 in wheat greatly decreases cadmium accumulation in wheat grains. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54(16):10100–10108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penner GA, Bezte LJ, Leisle D, Clarke J. Identification of RAPD markers linked to a gene governing cadmium uptake in durum wheat. Genome. 1995;38:543–547. doi: 10.1139/g95-070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knox RE, Pozniak CJ, Clarke FR, Clarke JM, Houshmand S, Singh AK. Chromosomal location of the cadmium uptake gene (Cdu1) in durum wheat. Genome. 2009;52:741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiebe K, Harris NS, Faris JD, Clarke JM, Knox RE, Taylor GJ, et al. Targeted mapping of Cdu1, a major locus regulating grain cadmium concentration in durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. var durum). Theor Appl Genet. 2010;121:1047–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiebe K, Pozniak C, Harris N, MacLachlan PR, Clarke J, Sharpe A, et al. Molecular characterization of Cdu-B1, a major locus responsible for cadmium concentration in durum wheat grain. Genome. 2012;55:709. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maccaferri M, Harris NS, Twardziok SO, Pasam RK, Gundlach H, Spannagl M, et al. Durum wheat genome highlights past domestication signatures and future improvement targets. Nat Genet. 2019;51:885–895. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0381-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guttieri MJ, Baenziger SP, Frels K, Carver B, Arnall B, Wang S, et al. Prospects for selecting wheat with increased zinc and decreased cadmium concentration in grain. Crop Sci. 2015;(55): 1712–1728. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kihara H. Discovery of the DD-analyser, one of the ancestors of Triticum vulgare. Biol agric Hortic. 1944;19:889–890. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFadden ES, Sears ER. The artificial synthesis of Triticum spelta. Rec Genet Soc Am. 1944;13:26–27. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFadden ES, Sears ER. The origin of Triticum spelta and its free-threshing hexaploid relatives. J Hered. 1946;37:81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen C, Yang J, Yuan Z, Ning S, Zhang L, Hao M, et al. Biosystematics of Triticeae: Volume I. Triticum-Aegilops complex. China Agriculture Press and Springer Nature Singapore; 2020.

- 22.Li A, Liu D, Yang W, Kishii M, Mao L. Synthetic Hexaploid Wheat: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. Engineering. 2018;4:552–558. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao M, Zhang L, Zhao L, Dai S, Li A, Yang W, et al. A breeding strategy targeting the secondary gene pool of bread wheat: introgression from a synthetic hexaploid wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 2019;132:2285–2294. doi: 10.1007/s00122-019-03354-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hao M, Zhang L, Zhao L, Dai S, Li A, Yang W, et al. The resurgence of introgression breeding, as exemplified in wheat improvement. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:252. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu G, Zhang L, Chuan X, Jia J, Zhang Q, Dong C, et al. Mapping of the heading date gene HdAey2280 in Aegilops tauschii. J Integr Agric. 2016;15(12): 2719–2725. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molnár I, Gáspár L, Sárvári É, Sándor D, Borbála Hoffmann, Márta M, et al. Physiological and morphological responses to water stress in Aegilops biuncialis and Triticum aestivum genotypes with differing tolerance to drought. Funct Plant Biol. 2004;31(12): 1149–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colmer T, Flowers T, Munns R. Use of wild relatives to improve salt tolerance in wheat. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(5): 1059–1078. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L, Liu K, Mao S, Li Z, Lu Y, Wang J, et al. Large-scale screening for Aegilops tauschii tolerant genotypes to phosphorus deficiency at seedling stage. Euphytica. 2015;204(3): 571–586. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin P, Wang L, Liu K, Mao S, Li Z, Gao S, et al. Genomewide association study of Aegilops tauschii traits under seedling-stage cadmium stress. Crop J. 2015;3(5): 405–415. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Luo M, Chen Z, You FM, Wei Y, Zheng Y, et al. Aegilops tauschii single nucleotide polymorphisms shed light on the origins of wheat D‐genome genetic diversity and pinpoint the geographic origin of hexaploid wheat. New phytol. 2013;198(3):925–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA 11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;(7):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ueno D, Koyama E, Yamaji N, Ma JF. Physiological, genetic, and molecular characterization of a high-Cd-accumulating rice cultivar, Jarjan. J Exp Bot. 2011; 62:2265–2272. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang L, Wu J, Tang Z, Huang X, Wang X, Salt DE, et al. Variation in the BrHMA3 coding region controls natural variation in cadmium accumulation in Brassica rapa vegetables. J Exp Bot. 2019;70 (20):5865–5878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eig A. Monographish-kritische Ubersicht der Gattung Aegilops. In: Fedde F, editor. Repertorium specierum novarum regni vegetabilis. Dahlem bei Berlin, Germany: Verlag des Repertoriums; 1929. p. 1–228.

- 35.Kihara H, Tanaka M. Morphological and physiological variation among Aegilops squarossa strains collected in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran. Preslia. 1958; 30: 24–251. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hammer K. Zur Taxonomie und Nomenklatur der Gattung Aegilops L. Feddes Repertorium. 1980;91:225–58. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nishikawa K. Alpha-amylase isozymes and phylogeny of hexaploid wheat. In: Sears ER, Sears LMS, editors. 4th International Wheat Genetics Symposium. Columbia, MO, USA: Missouri Agr. Exp. Sta; 1973.p. 851–855.

- 38.Nakai Y. Isozyme variation in Aegilops and Triticum, IV. The origin of the common wheats revealed from the study on esterase isozymes in synthesized hexaploid wheats. J Genet. 1979;54:175–189. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaaska V. Electrophoretic survey of seedling esterases in wheats in relation to their phylogeny. Theor Appl Genet. 1980;56:273–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00282570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishikawa K, Furuta Y, Wada T. Genetic studies on alpha-amylase isozymes in wheat. III. Intraspecific variation in Aegilops squarrosa and birthplace of hexaploid wheat. J Genet. 1980;55: 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lagudah ES, Appels R, Brown ADH. The molecular-genetic analysis of Triticum tauschii, the D genome donor to hexaploid wheat. Genome. 1991;36:913–918. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lubbers EL, Gill KS, Cox TS, Gill BS. Variation of molecular markers among geographically diverse accessions of Triticum tauschii. Genome. 1991;34:354–361. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dvorak J, Luo M, Yang Z, Zhang H. The structure of Aegilops tauschii genepool and the evolution of hexaploid wheat. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;97:657–670. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dvorak J, Deal K, Luo M, You F, Borstel K, Dehghani H. The origin of spelt and free-threshing hexaploid wheat. J Hered. 2012;103:426–441. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esr152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Variations compared to TaHMA3-D1 are indicated. Transmembrane domains (TM1-8) predicted by TOPCONS are shown in boxes.

(RTF)

Data Availability Statement

All sequences are available from the GenBank database (accession number(s) OL739674 to OL739683).