Abstract

Introduction

Dupilumab has significantly improved the signs, symptoms and quality of life (QoL) of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) in randomised, controlled clinical trials. However, there is a need to assess the effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in real-world clinical practice. The PROLEAD study was designed to examine the effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in moderate-to-severe AD in a real-world setting in Germany. Here, we present 12-week effectiveness and safety results with dupilumab from PROLEAD.

Methods

PROLEAD is a multicentre, prospective, non-interventional study being conducted at 126 routine care sites across Germany. Adults with moderate-to-severe AD who require systemic therapy were treated with dupilumab as indicated by the Summary of Product Characteristics. Data collected included physician assessments (EASI, BSA, SCORAD, and IGA) and patient-reported outcomes (PROs [POEM, DLQI, EQ-5D-5L, Peak Pruritus NRS and MOS Sleep Scale]).

Results

Of 839 patients assessed for eligibility, 828 were included. The full analysis and safety analysis sets comprised 775 and 818 patients, respectively. The number of patients receiving concomitant therapy decreased from baseline to Week 12. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) percentage change in EASI score from baseline to Week 12 was –67.5% (48.4%) and was comparable across the four body regions. The proportion of patients achieving EASI-75 was 59.4% at Week 12. Mean (SD) Peak Pruritus NRS decreased from 7.4 (2.3) at baseline to 3.4 (2.6) at Week 12. Improvements from baseline to Week 12 were reported in all PROs assessed. No new safety signals were observed.

Discussion

Improvements in efficacy outcomes and adverse event rates in a real-world setting were more favourable than in phase 3 clinical trials.

Conclusions

The 12-week findings of PROLEAD demonstrate that treatment with dupilumab is effective and well tolerated, with rapid onset of action in signs, symptoms and QoL in patients with moderate-to-severe AD in the real world.

Trial Registration Number

DUPILL08907; NIS-Nr. 433.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Biologic, Dupilumab, Real-world evidence

Key Summary Points

| Dupilumab has significantly improved the signs, symptoms and quality of life in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in randomised clinical trials |

| PROLEAD was designed to describe the real-world effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis |

| The present analysis reports the 12-week effectiveness and safety results of treatment with dupilumab in PROLEAD |

| The 12-week findings demonstrate that treatment with dupilumab is effective and well tolerated, with a rapid onset of action in improving signs, symptoms and quality of life |

| The rates of adverse events reported in a real-world setting were lower compared with the rates of adverse events reported in previous phase 3 clinical trials |

Introduction

Moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic type 2 inflammatory disease characterised by impairment of the epidermal barrier and immune dysregulation. Patients with AD experience high disease burden with frequent flares and intense itch, resulting in poor quality of life (QoL) [1–3]. Patients with uncontrolled AD frequently report anxiety, depression and sleep disorders, with significantly greater impairment of work and activity compared with patients without AD [4].

Prior to 2017, patients with moderate-to-severe AD not responding to topical therapies were treated with conventional systemic regimens such as immunosuppressants. The treatment landscape has since evolved, with approved therapies now including biologics and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. The major difference in the two treatment classes is that biologics represent a targeted approach, whereas JAK inhibitors act more broadly on multiple signalling cascades and are considered immunosuppressants [5–10].

Dupilumab (Dupixent®) is the first and only available biologic that inhibits type 2 inflammation via dual inhibition of both interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 signalling, which are key drivers of type 2 inflammation in AD and other type 2 inflammatory diseases [2, 5]. Dupilumab is licensed by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD in adults and adolescents (≥ 12 years) as well as for the treatment of severe AD in children aged 6–11 years who are candidates for systemic therapy [5]. Two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies, LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2, investigated the efficacy and safety of dupilumab monotherapy in adults with moderate-to-severe AD. In a pooled analysis of these two 16-week studies with identical design, dupilumab significantly improved signs, symptoms and QoL compared with placebo and showed a favourable safety profile [11]. In a phase 3 randomised, controlled clinical study (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS), combination therapy with dupilumab and topical corticosteroids (TCS) showed improvements in signs of moderate-to-severe AD [12].

There is a need to investigate the effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe AD in daily practice. PROLEAD is the largest prospective, non-interventional study (NIS) of adults with moderate-to-severe AD in Europe, and the objective is to investigate the effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in a real-world setting as well as the transition of patients from prior AD therapy to dupilumab in routine clinical practice in Germany. The baseline characteristics of patients in PROLEAD have been published previously [13]. Here, we report 12-week effectiveness and safety results.

Methods

Study Design

The PROLEAD study design has been published previously [13]. In brief, PROLEAD was a multicentre, prospective NIS with a 2-year observation period being conducted in 126 sites across Germany. The present analysis reports data from baseline, Week 4, and Week 12.

The transition period from prior therapy to dupilumab was assessed retrospectively, and concomitant treatments were assessed at baseline and thereafter. Measures of the effectiveness and safety of dupilumab were assessed prospectively.

Participants

Adult patients aged ≥ 18 years with moderate-to-severe AD who had not previously received dupilumab were included. Dupilumab was administered in accordance with the Summary of Product Characteristics [5]. All patients provided written informed consent.

Data Collection and Assessments

Collected data included: patient demographics; concomitant treatment and dosage; physician- and patient-reported outcome (PROs); measures of disease severity and disease burden; and safety.

Routine clinical documentation records included medical charts, physician assessments (Eczema Area and Severity Index [EASI; 0–72] [14], SCORing Atopic Dermatitis [SCORAD; 0–103] and Investigator’s Global Assessment [IGA; 0–4]) [15], patient-completed questionnaires (Patient Oriented Eczema Measure [POEM; 0–28] [16], Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI; 0–30]) [17], five-level EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire [EQ-5D-5L; 0–1] [18], Peak Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale [NRS; 0–10] [19], Medical Outcomes Study [MOS] Sleep Scale [0–100] [20], and specific questions relating to past physician visits and financial burden), hospital discharge files, prescription drug files, and doctors’ letters.

Last prior AD treatment before baseline was defined as the last prior AD treatment ending within 1 year of baseline data collection; if ≥ 2 prior AD treatments were given in parallel, each was regarded as the last prior AD treatment. If patients received more than one class of drug/TCS, the drug with the highest strength/TCS class was recorded and used in statistical analyses. The strength of topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) was considered to be between TCS class 2 and 3, as described by Cury Martins et al. [21].

Clinically meaningful response was assessed, as previously defined, as patients achieving EASI-50, ≥ 3 point improvement in peak pruritus NRS from baseline, or ≥ 4 point improvement in DLQI at Month 3 [22]. Disease severity was stratified according to EASI score: moderate AD was defined as a baseline EASI score between 7.1 and 21.0 and severe AD as a baseline EASI score > 21.0 and/or systemic AD therapy at last prior visit before baseline [23].

Statistical Analyses

This analysis was based on the final data cut-off date of 1 October, 2021, and represents the full analysis set (FAS) for all effectiveness endpoints and the safety analysis set (SAS) for all safety outcomes until Week 12. The FAS comprised all patients with signed informed consent who met the selection criteria, had a baseline assessment of efficacy endpoints and at least one recorded evaluation of one optional efficacy examination after baseline, and received at least one approved dose of dupilumab during the study. All patients with informed consent who received at least one approved dose of dupilumab were included in the SAS.

Due to the non-interventional nature of this study, no hypothesis was predefined, and no formal statistical power calculation was performed.

A sample size of 750 patients was sufficient for a 95% confidence interval of 46.4–53.6%, assuming an estimated response rate of 50% (e.g., for EASI-75, ≥ 75% improvement of the EASI score from baseline), and to detect rare adverse events (AEs) with high likelihood. Descriptive statistics are presented for all data, and the number of non-missing data, means, standard deviations (SD), medians, and interquartile ranges were used as sample statistics. Generally, missing values were not considered for calculation of percentages without using an imputation method. Data are presented as observed, except for concomitant treatment at Weeks 4 and 12. For missing visits, the concomitant treatment at last visit was carried forward, excepting oral corticosteroids.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Lübeck, Germany, and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the guidelines for Good Epidemiological Practice, and all local regulatory guidelines.

Results

Participants

Patients were included in PROLEAD between 13 April, 2018, and 30 September, 2020. Of 839 patients assessed for eligibility, 828 were included in the study. Baseline data were available for 817 patients who received the approved dosage of dupilumab at baseline. Overall, 775 and 818 patients were included in the FAS and SAS, respectively. Baseline characteristics and demographics of these patients have been published previously [13]. Numbers of patients at Weeks 4 and 12 were 677 and 662, respectively.

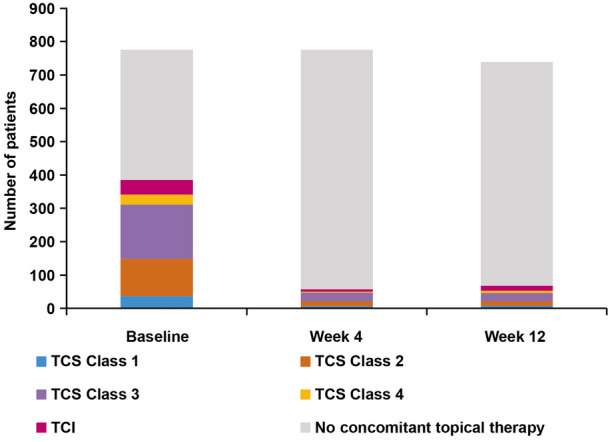

Concomitant Treatment

Concomitant topical therapy use over time is presented in Fig. 1. The number of patients receiving TCS and TCI decreased from baseline to Week 12, with noticeable reductions by Week 4. Decreases in the use of all classes of TCS and TCI were observed.

Fig. 1.

Concomitant topical anti-inflammatory therapy use at baseline, Week 4, and Week 12 (N = 775), TCS/TCI class of highest potency per patient shown. Data are as observed for baseline and last observation carried forward at Weeks 4 and 12. TCS topical corticosteroids, TCI topical calcineurin inhibitors

Concomitant UV therapy was received by ten (1.3%) patients at baseline, three (0.4%) at Week 4, and three (0.4%) at Week 12. Concomitant systemic therapy use is shown in Table 1. Oral corticosteroids were used by 12 patients (1.5%) at baseline in addition to dupilumab, decreasing to 3 patients (0.4%) at Week 12. Ciclosporin A and azathioprine were used, respectively, by five patients (0.6%) and one patient at baseline in addition to dupilumab, both decreasing to zero patients at Week 12. Antihistamines were used by 112 patients (14.5%) at baseline, 16 patients (2.1%) at Week 4 and 21 patients (2.7%) at Week 12.

Table 1.

Patients receiving concomitant systemic therapy (n = 775)

| Concomitant systemic therapy, n (%) | Baseline | Week 4 | Week 12 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral corticosteroids | 12 (1.5) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) |

| Ciclosporin A | 5 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 0 |

| Methotrexate | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Azathioprine | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antihistamines | 112 (14.5) | 16 (2.1) | 21 (2.7) |

Physician-Assessed Outcomes

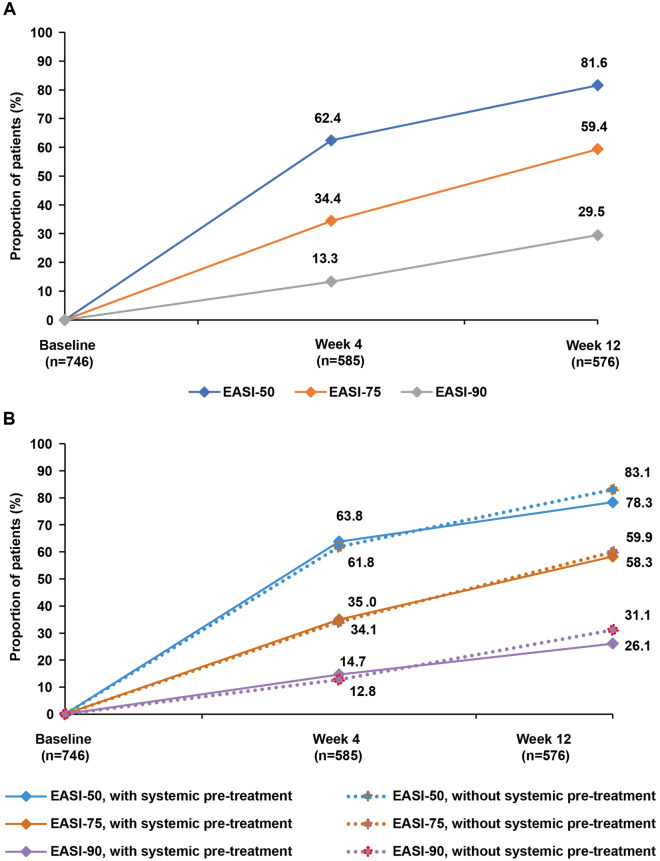

Mean (SD) EASI score decreased from 23.1 (14.5) at baseline to 6.1 (7.5) at Week 12. Mean (SD) percentage change in EASI score from baseline to Weeks 4 (n = 585) and 12 (n = 576) was − 52.5% (42.1%) and –67.5% (48.4%), respectively. Mean percentage change in EASI score from baseline to Week 12 was comparable across all body regions (head/neck: − 55.7%; torso: − 66.7%; upper extremities: − 63.4%; lower extremities: − 69.8%). Proportion of patients achieving EASI-50, EASI-75, and EASI-90 was 62.4%, 34.4%, and 13.3% at Week 4 and 81.6%, 59.4%, and 29.5% at Week 12, respectively (Fig. 2A). No differences in EASI-50, EASI-75, or EASI-90 response rates were observed based on systematic therapy usage prior to initiating dupilumab (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of patients achieving EASI-50, -75, and -90 (a), with or without systemic pre-treatment (b), at baseline, Week 4, and Week 12 (as observed analysis). EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index

From baseline to Week 12, mean (SD) body surface area (BSA) affected decreased from 44.3% (25.8) to 16.1% (18.9), and mean (SD) SCORAD score decreased from 63.3 (16.2) to 29.8 (15.5) (Table 2). Mean (SD) SCORAD sleeplessness score at baseline (n = 772), Week 4 (n = 670), and Week 12 (n = 653) was 5.5 (3.1), 2.6 (2.6), and 1.8 (2.4), respectively. Mean (SD) SCORAD pruritus score at baseline (n = 772), Week 4 (n = 670), and Week 12 (n = 654) was 7.2 (2.3), 3.8 (2.5), and 2.9 (2.3), respectively.

Table 2.

Physician- and patient-reported outcomes at baseline, Week 4, and Week 12

| Timepoint | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician-assessed scores | ||||||

| EASI | Baseline | 23.1 | 14.5 | 20.6 | 12.0–31.2 | 746 |

| Week 4 | 9.9 | 9.0 | 7.2 | 3.4–14.4 | 589 | |

| Week 12 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 3.6 | 1.5–7.5 | 584 | |

| BSA | Baseline | 44.3 | 25.8 | 40.0 | 23.0–63.0 | 772 |

| Week 4 | 25.0 | 22.8 | 18.0 | 8.0–36.0 | 670 | |

| Week 12 | 16.1 | 18.9 | 10.0 | 4.0–20.5 | 655 | |

| SCORAD | Baseline | 63.3 | 16.2 | 64.1 | 25.3–74.5 | 772 |

| Week 4 | 37.5 | 16.5 | 35.7 | 25.9–48.4 | 656 | |

| Week 12 | 29.8 | 15.5 | 27.5 | 19.0–39.5 | 632 | |

| IGA | Baseline | 3.3 | 0.7 | 3.0 | 3.0–4.0 | 773 |

| Week 4 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 2.0–3.0 | 674 | |

| Week 12 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 2.0–4.0 | 659 | |

| Patient-reported outcomes | ||||||

| POEM | Baseline | 20.3 | 6.2 | 21.0 | 16.0–25.0 | 754 |

| Week 4 | 10.7 | 6.4 | 10.0 | 5.0–15.0 | 660 | |

| Week 12 | 8.4 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 4.0–12.0 | 631 | |

| Peak Pruritus NRS | Baseline | 7.4 | 2.3 | 8.0 | 6.0–9.0 | 760 |

| Week 4 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 2.0–6.0 | 658 | |

| Week 12 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 627 | |

| DLQI | Baseline | 13.9 | 7.1 | 13.0 | 8.0–19.0 | 766 |

| Week 4 | 6.8 | 5.7 | 5.0 | 2.0–9.0 | 667 | |

| Week 12 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 3.0 | 1.0–7.0 | 634 | |

| MOS Sleep Index II | Baseline | 48.0 | 19.4 | 47.4 | 33.9–62.8 | 768 |

| Week 4 | 32.7 | 17.0 | 30.0 | 20.6–42.8 | 666 | |

| Week 12 | 29.0 | 17.3 | 26.7 | 16.1–37.5 | 634 | |

| EQ-5D | Baseline | 0.82 | 0.18 | 0.89 | 0.78–0.91 | 758 |

| Week 4 | 0.90 | 0.13 | 0.91 | 0.89–1.00 | 661 | |

| Week 12 | 0.91 | 0.14 | 0.91 | 0.91–1.00 | 628 | |

BSA body surface area, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EQ-5D EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, IQR interquartile range, MOS Medical Outcomes Study, NRS Numerical Rating Scale, POEM Patient Oriented Eczema Measure, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SD standard deviation

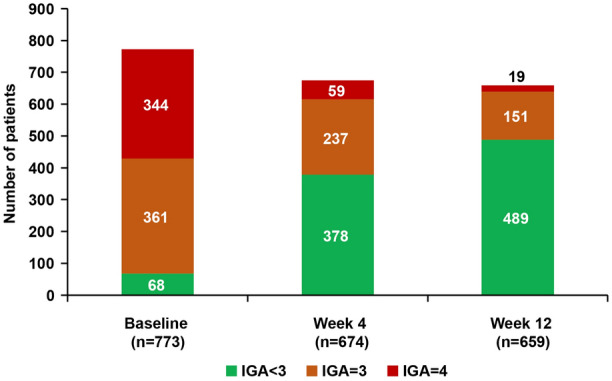

Mean (SD) IGA score decreased from 3.3 (0.7) at baseline to 1.9 (0.9) at Week 12 (Table 2). Mean categorical IGA score at baseline, Week 4, and Week 12 is presented in Fig. 3. Proportions of patients achieving IGA 0/1 with a reduction of ≥ 2 points from baseline were 15.3% and 33.0% at Weeks 4 and 12, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Categorical IGA score at baseline, Week 4, and Week 12 (as observed analysis). IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Mean (SD) POEM score decreased from 20.3 (6.2) at baseline to 8.4 (6.0) at Week 12. Mean (SD) peak pruritus NRS score decreased from 7.4 (2.3) to 3.4 (2.6). Mean (SD) change from baseline in peak pruritus NRS score was − 38.4% (42.1%) and − 49.4% (52.0%) for Weeks 4 and 12, respectively (Table 2). Respective proportions of patients achieving ≥ 3- and ≥ 4-point improvements from baseline in peak pruritus NRS score were 52.4% and 40.4% at Week 4 (n = 649) and 65.8% and 57.0% at Week 12 (n = 619).

From baseline to Week 12, mean (SD) DLQI score decreased from 13.9 (7.1) to 4.8 (4.9) and mean (SD) Sleep Index II score decreased from 48.0 (19.4) to 29.0 (17.3). Mean (SD) EQ-5D Index score increased from 0.82 (0.18) at baseline to 0.91 (0.14) at Week 12.

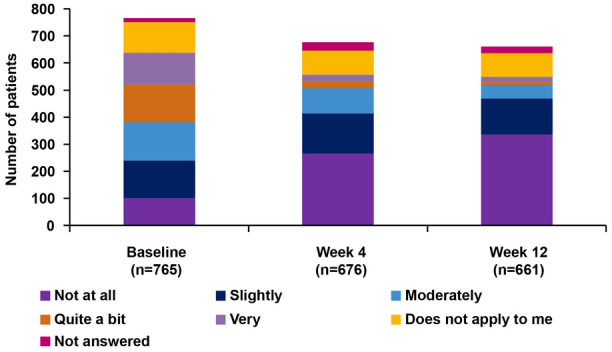

Burden and Severity of Disease

Responding to the question, “To what extent does your AD hamper you currently in practising your profession/in your studies/in everyday school life?”, the number of patients who answered “very”, “quite a bit”, or “moderately” decreased from 397 (51.2%) at baseline to 142 (21.0%) and 79 (11.9%) at Weeks 4 and 12, respectively (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Patient questionnaire: effort and burden due to AD at baseline, Week 4 and Week 12 (as observed analysis). Original question: “To what extent does your AD hamper you currently in practising your profession/in your studies/in everyday school life?” AD atopic dermatitis

Respectively, 209 (27.0%) and 497 (64.1%) patients presented with moderate AD and severe AD at baseline. Regarding the proportion of patients achieving EASI-75, patients with moderate AD (50.0%) benefited to a similar extent as those with severe AD (56.4%) at Week 12. This result was also evident in the mean percent change from baseline at Week 12 in EASI, peak pruritus NRS and DLQI (data not shown).

Clinically Meaningful Response

In total, 87.0% (n = 589/677) and 93.4% (n = 618/662) of patients achieved a clinically meaningful response [22] at Weeks 4 and 12, respectively. Similar clinically meaningful response rates were observed between patients with moderate AD (Week 4: 87.7%; Week 12: 94.8%) and severe AD (Week 4: 86.8%; Week 12: 94.2%) according to baseline EASI score.

Safety

Overall, 57 (7%) patients discontinued treatment within the first 12 weeks of study. Most common reasons for discontinuation were loss of contact (n = 11) and AEs (n = 9).

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported by 193 patients (23.6%, 17.88 patients per 100 patient-years (/100 PY) and serious TEAEs by 18 patients (2.2%, 1.67/100 PY). Drug-related TEAEs were reported in 113 (13.8%) patients. Most common TEAEs occurring in > 1% of patients were conjunctivitis (n = 61, 7.5%), nasopharyngitis (n = 14, 1.7%) and headache (n = 14, 1.7%). The most common drug-related TEAE was conjunctivitis (n = 54, 6.6%, 5.00/100PY) (Table 3). No injection-site reactions were reported.

Table 3.

Safety assessments (N = 818): number and proportion of patients with treatment emergent adverse events (TEAE) and TEAE occurring in > 1% of total patients

| Adverse events, patients with ≥ 1 event, n (%) | Number of patients with ≥ 1 event per 100 patient years | |

|---|---|---|

| TEAE | 193 (23.6) | 17.88 |

| Serious TEAE | 18 (2.2) | 1.67 |

| Drug-related TEAE | 113 (13.8) | 10.47 |

| TEAE by MedDRA system organ class and preferred term (> 1% of total patients), n (%) | ||

| General disorders and administration site conditions | ||

| Fatigue | 9 (1.1) | 0.83 |

| Infections and infestations | ||

| Nasopharyngitis | 14 (1.7) | 1.30 |

| Oral herpes | 10 (1.2) | 0.93 |

| Eye disorders | ||

| Conjunctivitisa | 61 (7.5) | 5.65 |

| Nervous system disorders | ||

| Headache | 14 (1.7) | 1.30 |

| Most common drug-related TEAE by MedDRA system organ class and preferred term (> 1% of patients), n (%) | ||

| Eye disorders | ||

| Conjunctivitis | 54 (6.6) | 5.00 |

TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

aConjunctivitis includes allergic conjunctivitis, bacterial conjunctivitis, viral conjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis and conjunctivitis

Discussion

PROLEAD is the largest study in Europe designed to investigate the use, effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe AD receiving treatment as part of routine dermatological clinical practice in Germany. In contrast to randomised controlled studies, applying strict eligibility criteria, PROLEAD collects real-world data from AD patients in clinics and medical practices.

We observed that although baseline concomitant topical therapy use was relatively low, treatment with dupilumab led to a further decrease in the use of these therapies. Treatment guidelines [24] advise topical anti-inflammatory therapies should be administered with dupilumab to achieve optimal AD management; in contrast, the Summary of Product Characteristics states dupilumab can be used with or without topical anti-inflammatory therapies [5]. In cases where patients respond sufficiently with dupilumab, there is reduced need for treatment with topical therapies, and dupilumab-associated improvement in AD symptoms is likely to explain the decrease in topical therapy use in this study. Although treatment with dupilumab has been recommended to overlap with prior systemic treatments by Ludwig et al. and de Wijs et al., we discovered that in a real-life setting, most patients do not receive the recommended treatment overlap of two systemic therapies for AD [25, 26]. Furthermore, patients receiving dupilumab also received antihistamines, which are minimally effective in the management of AD-related itch [27]; however, frequency of patients receiving antihistamines decreased over time with dupilumab treatment.

Improvements in physician-assessed outcomes in PROLEAD were broadly comparable with those of a pooled analysis of the phase 3 randomised LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2 dupilumab monotherapy trials; this pooled analysis was used for comparison as most patients in PROLEAD did not receive topical anti-inflammatory treatment [11]. However, proportion of patients achieving EASI-50, EASI-75 and EASI-90 was higher or comparable in PROLEAD at Week 12 (81.6%, 59.4% and 29.5%, respectively) than in LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2 at Week 16 (67.0%, 47.7% and 32.8%, respectively). Similar results were observed when comparing data from PROLEAD with those from dupilumab-treated patients (n = 105) in the TREATgermany registry, a non-interventional, multicentre, patient cohort study [28]. Proportion of patients achieving EASI-50, EASI-75 and EASI-90 in TREATgermany was 77.1%, 57.1% and 25.7%, respectively, at Week 12. The findings of PROLEAD were also comparable with real-world data from the BIOREP registry [29]. A similar improvement in mean percentage change in EASI scores was observed across the four body regions in PROLEAD as was reported in the post-hoc analysis of LIBERTY AD CHRONOS, a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled 1-year trial of dupilumab in combination with TCS in patients with moderate-to-severe AD [12]. Prior systemic AD treatment did not impact treatment response to dupilumab in PROLEAD and this was also evident in the CHRONOS post-hoc analysis [30].

Differing results seen in PROLEAD and LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2 may be explained by differing trial designs. There was no washout period in PROLEAD, and assessment timepoints were at baseline, Week 4 and Week 12 compared with baseline and Week 16 in LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2; moreover, patients receiving concomitant topical anti-inflammatory treatment in LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2 were excluded, unlike in PROLEAD. Therefore, comparison of the results must be made with caution. However, the confirmatory results in EASI responder rates obtained in PROLEAD and TREATgermany demonstrate that, in a real-world setting, dupilumab is effective in the treatment of signs of AD at an earlier timepoint (Week 12) than in the phase 3 trials (Week 16).

In terms of PROs, mean (SD) POEM score in PROLEAD at Week 12 (8.4 [6.0] vs. 20.3 [6.2] at baseline) was consistent with observations from patients treated with dupilumab monotherapy in TREATgermany at Week 12 (8.8 [5.9] vs. 19.3 [6.4] at baseline) and from patients treated with dupilumab monotherapy in LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2 at Week 16 (9.3 [6.3] vs. a median of 21.0 at baseline). The same was true for mean peak pruritus NRS score at Week 12 in PROLEAD (3.4 [2.6] vs. 7.4 [2.3] at baseline) and TREATgermany (2.7 [2.1] vs. 6.4 [2.2] at baseline) and Week 16 in LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2 (3.8 [2.2] vs. a median of 7.7 at baseline) [11, 28]. In addition, mean (SD) DLQI score in PROLEAD at Week 12 (4.8 [4.9] vs. 13.9 [7.1] at baseline) was consistent with observations in TREATgermany (4.4 [5.2] vs. 12.4 [6.7] at baseline), in LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 AND 2 at Week 16 (5.3 [5.3] vs. a median of 14.0 at baseline) and in the RELIEVE-AD study (4.8 [5.5] vs. 14.4 [7.3] at baseline), a prospective, longitudinal cohort survey (n = 596) designed to characterise patient experience with dupilumab in clinical practice [11, 28, 31]. Thus, patients treated with dupilumab in the real-world show a rapid response in symptoms and QoL in AD, which is confirmed by this large study. It is also important to note these improvements are achieved earlier in the real-world than in the phase 3 clinical trials. Patients in PROLEAD also experienced clinically meaningful improvement in sleep quality, as measured by the MOS-Sleep Index II (a change of ≥ 5.1 is regarded as a minimal clinically important difference), and improvements were also observed in QoL as measured on the EQ-5D-5L Index. Furthermore, a clinically meaningful response rate of 93.4% was achieved in PROLEAD, which was higher than that reported in CHRONOS, in which patients were treated with concomitant TCS [30].

As demonstrated by PROs data, burden of disease rapidly decreased over time following dupilumab treatment. Dupilumab treatment effects were comparable for patients with either moderate or severe AD at baseline with respect to EASI-75, mean percentage change in EASI and peak pruritus NRS and DLQI. Nevertheless, more patients with severe AD were treated with dupilumab in real-world clinical practice, even though patients with moderate AD benefit to the same extent. Of note, guidelines do not yet recommend systemic treatment options such as dupilumab for moderate AD.

Safety results were consistent with the known safety profile of dupilumab, except for lack of injection-site reactions, suggesting that in real-world use of dupilumab this AE does not play a role compared with the phase 3 trials (injection site reactions were reported in 57 patients [12.3%] in LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and 2). Numbers of TEAEs and serious TEAEs per 100 patient-years were lower in PROLEAD (Table 3) than in LIBERTY AD CHRONOS (TEAEs, 322.43/100 PY; serious TEAEs, 3.40/100 PY) and the phase 3 open-label extension (OLE) study (TEAEs, 167.50/100 PY; serious TEAEs, 5.20/ 100 PY), although these data are from longer follow-up periods than reported here [32]. The low rates of discontinuation of dupilumab treatment during the first 12 weeks, and drug-related TEAEs, reflect the good tolerability of dupilumab, with no new safety signals reported. Rate of patients with drug-related TEAEs of conjunctivitis per 100 patient-years in this study (Table 3) is generally comparable with those reported in CHRONOS (5.21/ 100 PY) and the OLE study (4.94/100 PY). Nevertheless, the rate of dupilumab-induced conjunctivitis is relatively low, and we see fewer safety signals in the real-world compared with the phase 3 trials [32].

The strengths of PROLEAD include utilising the same PROs assessed in clinical trials, enabling comparisons between real-world evidence of NIS and randomised clinical trials. Furthermore, patients with AD encounter limited access to clinical studies due to restrictive eligibility criteria. PROLEAD reflects the reality of AD patients in everyday healthcare provision, as patients treated by office-based dermatologists and specialised dermatology centres were included. The study visit schedule in PROLEAD also provides a more accurate representation of assessment timepoints, as PROLEAD was designed around routine clinical care. This analysis focussed on the effectiveness and safety of dupilumab during the first 12 weeks of treatment, a timepoint that is frequently considered for evaluating the effectiveness on signs, symptoms and quality of life, in addition to safety, in patients with AD. Limitations of PROLEAD include the lack of a comparator arm and blinding and potential susceptibility to statistical bias due to use of PROs, which can be influenced by other factors. Moreover, as previously mentioned, the present study reports only the 12-week results of PROLEAD; however, further publications are planned to report the long-term effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in this trial.

Conclusion

Treatment with dupilumab was effective and well tolerated in patients with moderate-to-severe AD, with a rapid onset of action in improving signs, symptoms and QoL. Thus, treatment with dupilumab meets the major needs of patients with AD in routine care as identified in large-scale studies [33] and thus contributes towards goal-oriented and patient-centred AD management. Treatment benefit of dupilumab was independent of pre-treatment with systemic therapy and disease severity. Dupilumab represents a suitable treatment option for patients with moderate or severe AD, irrespective of prior systemic treatment history.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the Rapid Service fee for this manuscript was funded by Sanofi.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors thank the participants included in this study. The authors also acknowledge Shaun Hall, MSc, of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio company, for medical writing support, funded by Sanofi.

Author Contributions

Matthias Augustin, Andrea Bauer, Konstantin Ertner, Ralph von Kiedrowski, Florian Schenck and Diamant Thaçi contributed to the conduct of this study as investigators and to the interpretation of the data. Mike Bastian, Anja Fait and Sophie Möller contributed to the conduct of the study, the analysis and interpretation of the data. Matthias Augustin and Diamant Thaçi contributed to the design of the study. All authors were involved in manuscript development, review and revision, and have read and approved the final version to be submitted. All authors satisfy the criteria for authorship as established by the ICMJE.

Disclosures

Matthias Augustin has served as consultant and/or paid speaker for and/or has received research grants and/or honoraria for consulting and/or scientific lectures and/or participated in clinical trials sponsored by companies that manufacture drugs used for the treatment of atopic dermatitis including AbbVie, Almirall, Beiersdorf, Galderma, LEO Lilly, Pfizer and Sanofi; Andrea Bauer is or recently was a speaker and/or advisor for, and/or has received research funding from Novartis, Genentec, Leo Pharma, Sanofi, Regeneron, Shire, Takeda, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Abbvie, Celldex, Lilly, Pharvaris, Almirall, L’Oreal and Biofrontera; Konstantin Ertner has fee activity and financial relationships with Abbvie GmbH & Co, Almirall Hermal GmbH, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Celgene GmbH, Janssen-Cilag GmbH, Galderma Laboratorium GmbG, UCB Pharma GmbH, and intangible conflicts of interest and/or memberships with Regionales Netzwek Psoriasis Nordbayern e.V. (2. Vorsitzender des regionalen Psoriasis Netzwek Nordbayern e.V.), Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft (DDG), Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft e.V. in der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dermatologische Onkologie (ADO), Deutsche Dermatologische Akademie (DDA), Deutsche Sexually Transmitted Disease Gesellschaft (DSTDG) and Berufsverband der Deutschen Dermatologen e.V. (BVDD); Ralph von Kiedrowski and his service company CMS3 GmbH provide consulting services, registry research, activities as an investigator in interventional and non-interventional studies, other services and scientific lectures for the following companies: AbbVie, ALK Scherax, Almirall Hermal, Amgen, Beiersdorf Dermo Medical, Biofrontera, Biogen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, DermaPharm, Foamix, Gilead, Hexal, Janssen-Cilag, LEO Pharma, Lilly Pharma, Meda/Mylan/Viatris, Medac, Menlo, MSD, Novartis Pharma, Dr. R. Pfleger, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, Stallergens, Stiefel GSK, Tigercut and UCB Pharma; Florian Schenck is an investigator in sponsored clinical trials and has received payments as a speaker or consultant from the following companies: Novartis Pharma GmbH, Janssen-Cilag GmbH, LeoPharma GmbH, AbbVie Deutschland GmbH&Co. KG, Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Almirall Hermal GmbH, Celgene GmbH, Hexal AG, UCB Pharma GmbH; Jutta Ramaker-Brunke has no conflicts of interest to disclose; Sophie Möller, Anja Fait and Mike Bastian are employees of Sanofi and may hold stock and/or stock options in the company; Diamant Thaçi is or has been a consultant, advisory board member, and/or investigator for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Beiersdorf, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Essex, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Galderma, Janssen-Cilag, LEO Pharma, MorphoSys, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Samsung, Sandoz, Sanofi, Sun Pharma and UCB.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Lübeck, Germany, and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the guidelines for Good Epidemiological Practice and all local regulatory guidelines.

Data Availability

Qualified researchers may request access to patient-level data and related documents. Patient-level data will be anonymized, and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of trial participants. Further details on Sanofi’s data sharing criteria, eligible studies and process for requesting access can be found at https://vivli.org/. A direct contact can be the corresponding author.

Prior Publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00149-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buzney CD, Gottlieb AB, Rosmarin D. Asthma and atopic dermatitis: a review of targeted inhibition of interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 as therapy for atopic disease. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Bruin-Weller M, Gadkari A, Auziere S, et al. The patient-reported disease burden in adults with atopic dermatitis: a cross-sectional study in Europe and Canada. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1026–1036. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckert L, Gupta S, Gadkari A, Mahajan P, Gelfand JM. Burden of illness in adults with atopic dermatitis: analysis of National Health and Wellness Survey data from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanofi. Dupixent® summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/dupixent-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 16 Mar 2022.

- 6.Lilly E. Olumiant® summary of product characteristics. 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/olumiant-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2022.

- 7.Limited LL. Adtralza® summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/adtralza-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2022.

- 8.AbbVie. Rinvoq® summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/rinvoq-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2022.

- 9.Pfizer. Cibinqo® summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/cibinqo-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar 2022.

- 10.Schwartz DM, Kanno Y, Villarino A, Ward M, Gadina M, O'Shea JJ. JAK inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for immune and inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:843–862. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Deleuran M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab monotherapy in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a pooled analysis of two phase 3 randomized trials (LIBERTY AD SOLO 1 and LIBERTY AD SOLO 2) J Dermatol Sci. 2019;94:266–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Simpson EL, Chen Z, Zhang A, Shumel B. Dupilumab with topical corticosteroids provides rapid and sustained improvement in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis across anatomic regions over 52 weeks. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022;12:223–231. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00638-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thaçi D, Bauer A, von Kiedrowski R, et al. Dupilumab treatment of atopic dermatitis in routine clinical care: baseline characteristics of patients in the PROLEAD prospective, observational study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2022;12:2145–2160. doi: 10.1007/s13555-022-00791-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M. The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. EASI Evaluator Group. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10:11–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Consensus Report of the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis Severity Scoring of Atopic Dermatitis: the SCORAD index. Consensus Report of the European Task Force on atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 1993;186:23–31. doi: 10.1159/000247298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charman CR, Venn AJ, Williams HC. The patient-oriented eczema measure: development and initial validation of a new tool for measuring atopic eczema severity from the patients' perspective. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1513–1519. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yosipovitch G, Reaney M, Mastey V, et al. Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale: psychometric validation and responder definition for assessing itch in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:761–769. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yarlas A, White MK, St Pierre DG, Bjorner JB. The development and validation of a revised version of the Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (MOS Sleep-R) J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5:40. doi: 10.1186/s41687-021-00311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cury Martins J, Martins C, Aoki V, Gois AFT, Ishii HA, da Silva EMK. Topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009864.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Bruin-Weller M, Biedermann T, Bissonnette R, et al. Treat-to-target in atopic dermatitis: an international consensus on a set of core decision points for systemic therapies. Acta Derm Venereol. 2021;101:adv00402. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leshem YA, Hajar T, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL. What the Eczema Area and Severity Index score tells us about the severity of atopic dermatitis: an interpretability study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:1353–1357. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werfel T, Heratizadeh A, Aberer W, et al. Update “systemic treatment of atopic dermatitis” of the S2k-guideline on atopic dermatitis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:151–168. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludwig CM, Krase JM, Price KN, Lio PA, Shi VY. A practical guide for transitioning from classical immunosuppressants to dupilumab in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:503–506. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1682498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Wijs LEM, Thyssen JP, Vestergaard C. An approach for the transition from systemic immunosuppressants to dupilumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:e221–e223. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang TB, Kim BS. Pruritus in allergy and immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abraham S, Haufe E, Harder I, et al. Implementation of dupilumab in routine care of atopic eczema: results from the German national registry TREATgermany. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:382–384. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kojanova M, Tanczosova M, Strosova D, BIOREP Study Group et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: real-world data from the Czech Republic BIOREP registry. J Dermatol Treat. 2022;33:2578–2586. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2043545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffiths C, de Bruin-Weller M, Deleuran M, et al. Dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and prior use of systemic non-steroidal immunosuppressants: analysis of four phase 3 trials. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021;11:1357–1372. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00558-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strober B, Mallya UG, Yang M, et al. Treatment outcomes associated with dupilumab use in patients with atopic dermatitis: 1-year results from the RELIEVE-AD study. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:142–150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.4778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck LA, Deleuran M, Bissonnette R, et al. Dupilumab provides acceptable safety and sustained efficacy for up to 4 years in an open-label study of adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:393–408. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00685-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Augustin M, Langenbruch A, Blome C, et al. Characterizing treatment-related patient needs in atopic eczema: insights for personalized goal orientation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:142–152. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to patient-level data and related documents. Patient-level data will be anonymized, and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of trial participants. Further details on Sanofi’s data sharing criteria, eligible studies and process for requesting access can be found at https://vivli.org/. A direct contact can be the corresponding author.