Labia minora elongation (LME) is a form of female genital mutilation (FGM) that involves the elongation of the inner lips of the female external genitalia or labia minora with the use of herbs (i.e., Solanum aculeastrum, Dunal, Bidens pilosa L.), oils, crèmes (i.e., cow-cheese), and other instruments until the intended length is achieved which can range from 2 to 8 cm.1 Unlike other types of FGM, LME is a prolonged process that takes months to years of physical and mental suffering. However, less emphasis has been given to the suffering related to this practice than other forms of FGM.

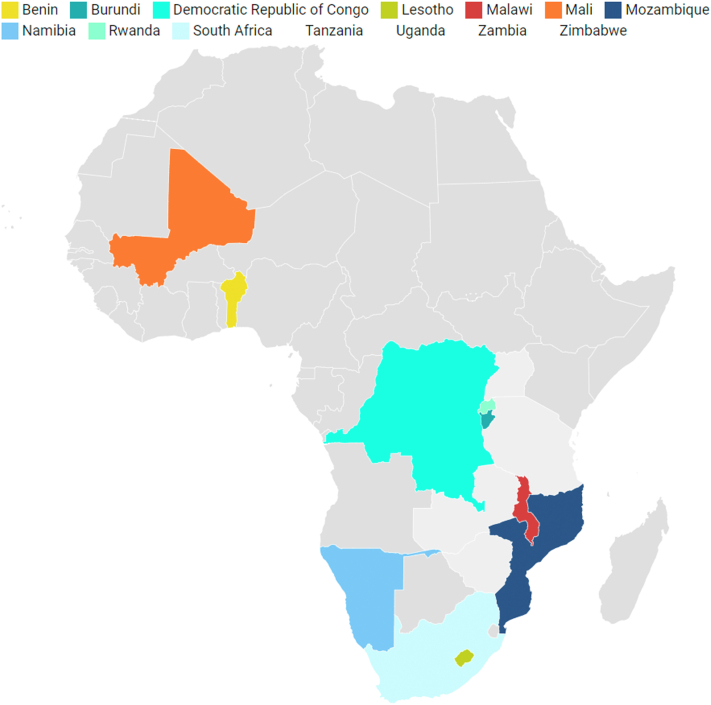

Similar to FGM, the practice of LME is common to a varying degree across Africa. It has been documented in east and southern African countries (Fig. 1). Young girls aged 8–14 years may be initiated/involved in LME to prepare for womanhood, marriage and increase their partners’ sexual pleasure.1,2 LME is classified as a lower type of FGM than circumcision types of FGM. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies LME as a type IV FGM - which encompasses all harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes (e.g., pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterisation).3 LME is classified as FGM because it is a social convention associated with social pressure on young girls to modify their genitalia, creating permanent genital changes.3

Fig. 1.

Map of Africa showing countries where labia minora elongation is practiced.

Commonly, the knowledge of the motivators, procedures, and substances used for LME is expected to be transmitted to the new generation (young girls) by their relatives (mainly aunts, elder sisters, mothers, and grandparents) around the onset of menstruation, when they are considered ready to be guided into womanhood.2 Verbal instruction, illustration, and demonstrations on other girls are often used to guide young girls about engaging in self-pulling/stretching of the labia minora daily until the intended length is achieved.1,4 Notably, this procedure is associated with physical, sexual, and psychosocial problems, including pain, swelling, irritation, or itchiness due to caustic herbs use, pain during urination, and fear of being stigmatised if the intended length is not achieved.1

Despite the pressure from the public, parents, peers, and spouses on women/girls to be involved in LMEs, less attention has been given to this form of FGM. Campaigns and advocacy activities are actively directed against other forms of FGM, thus, neglecting LME.5 We recommend more emphasis on this practice given that it may still be widely practiced more than any other form of FGM by some African girls and women. With globalisation of practices and immigration, LME is practiced by African people in the diaspora and may influence other individuals in their host countries.6 The health professionals in the host countries might be unfamiliar with the physical and psychosocial consequences of LME, thereby ignoring the condition.6 Therefore, educating health workers globally about LME, its consequences and their management is needed to reduce the health burden and mitigate against discrimination, marginalisation and a feeling of neglect by girls and women affected by LME within the health system.

Families and communities must be educated and sensitised about the physical and mental health consequences of LME on young girls. Educational resources against LME should be simple to comprehend, culturally sensitive, and widely available using locally viable technology. It may also be helpful to develop peer education sessions that integrate the perspectives of young girls with lived experience. The education should also target other members of the society, especially men since some of the motives for the practice are to increase sexual pleasure of partners. Multi-pronged efforts to throw more light into the myths and beliefs around this practice are needed. Educational initiatives on LME can be mainstreamed with existing reproductive health programs that are successful, acceptable, less stigmatised, and well established in Africa for other sexual health issues on menstrual health, hygiene, HIV prevention, and contraception.7 Also, a “safe space” (physical or online) commonly used for violence/abuse,8 should be made available for young girls and women to discuss their experiences and seek professional support and assistance to deal with the psychosocial and health challenges associated with LME.

In addition to the measures highlighted above, strong laws, regulations, policies, and monitoring strategies should be put in place to stem the acceptance of the practice of FGM, especially LME. A multi-sectorial approach involving policy makers, affected individuals, cultural leaders, NGOs, and families is needed to find a systematic approach to handle LME. Notably, aspects regarding its mental and sexual health, educational, and psychosocial ramifications should be studied to improve the level of evidence for interventions against this practice.

Contributors

Mark Mohan Kaggwa - Conceptualsation of the idea, literature review and searches, figures, study design, writing the original draft and subsequent revision. Gary Andrew Chaimowitz - Revision of the manuscript, supervision of the writing process, validation, visualisation, and made final edits before submission. Andrew Toyin Olagunju - Conceptualisation, literature review, visualisation, revision and editing, and supervision.

Declaration of interests

We declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pérez G.M., Tomas Aznar C., Bagnol B. Labia minora elongation and its implications on the health of women: a systematic review. Int J Sex Health. 2014;26(3):155–171. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilber A.M., Kenter E., Redmond S., et al. Vaginal practices as women's agency in sub-Saharan Africa: a synthesis of meaning and motivation through meta-ethnography. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(9):1311–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2008. Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation: An Interagency Statement-OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koster M., Price L.L. Rwandan female genital modification: elongation of the labia minora and the use of local botanical species. Cult Health Sex. 2008;10(2):191–204. doi: 10.1080/13691050701775076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tammary E., Manasi K. Mental and sexual health outcomes associated with FGM/C in Africa: a systematic narrative synthesis. eClinicalMedicine. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallo P.G., Bertoletti A., Zanotti I., Catania L. In: Genital Autonomy: Protecting Personal Choice. Denniston G.C., Hodges F.M., Milos M.F., editors. Springer Netherlands; Dordrecht: 2010. The first survey on genital stretching in Italy; pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desrosiers A., Betancourt T., Kergoat Y., Servilli C., Say L., Kobeissi L. A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people in humanitarian and lower-and-middle-income country settings. BMC Publ Health. 2020;20(1):666. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08818-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stark L., Robinson M.V., Seff I., Gillespie A., Colarelli J., Landis D. The effectiveness of women and girls safe spaces: a systematic review of evidence to address violence against women and girls in humanitarian contexts. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2021;23(4):1249–1261. doi: 10.1177/1524838021991306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]