Abstract

Zn2V2O7 phosphor was made using a sol-gel technique and then annealed at temperatures ranging from 700 to 850 °C. The x-ray diffraction (XRD) results revealed that Zn2V2O7 exhibits a single monoclinic phase. The width at half-maximum of the (022) XRD peak shrank overall resulting in improved crystallinity of the Zn2V2O7 phosphors with higher annealing temperatures. Because of the good crystallinity of Zn2V2O7, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) indicates that grain size increases as the annealing temperature rises. When the temperature was raised from 35 °C to 500 °C, TGA findings revealed a total weight loss of approximately 65%. The photoluminescence emission spectra of annealed Zn2V2O7 powders revealed a wide green-yellowish emission in the range of 400 nm–800 nm. As the annealing temperature was raised, the crystallinity improved, resulting in an increase in PL intensity. The peak of the PL emission shifts from green to yellow emission.

Keywords: Vanadate, Annealing, Crystallinity, Thermogravimetric, Photoluminescence

1. Introduction

As a substitute for incandescent and fluorescent lamps, the light-emitting diode (LED) has recently increased in several applications because of its high efficiency, extended lifespan, low power need, and other factors [1,2]. The first generation of w-LEDs that uses phosphors is created by combining a blue LED chip with a yellow-emitting phosphor, usually yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG: Ce3+) [3]. However, the quality of the current w-LEDs is significantly impacted by a low color-rendering index (Ra < 80) and highly correlated color temperature caused by a lack of red emission [4]. Researchers have been looking at using vanadium oxide-based materials to replace the yellow light-emitting YAG: Ce3+ in recent years due to their structural, magnetic, and optical properties. When the vanadate center is activated, it emits a wide luminescence in the visible range. Vanadate group (VO4)3- in which four oxygen ions in a tetrahedral (Td) symmetry is linked to a central ion, is known as an efficient luminescent center [5,6]. Zn2V2O7 has lately gained notice as a vanadium oxide material with a yellow-green self-activation. Zn2V2O7 is especially intriguing because it crystallizes at a low temperature, which is ideal for conserving energy and lowering manufacturing costs [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. The possible applications of Zn2V2O7 are, as a catalyst in the heterogeneous oxidation process [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]], photocatalytic for solar water splitting applications [16,19], and as an electrochemical supercapacitor and hydrogen storage material [13]. It's also said to be an excellent material for phosphors and white illumination diodes [14]. This has prompted a great deal of curiosity in chemistry, chemical engineering, physics, and material science over the years. Zn2V2O7 has two crystal structures: low- and high-temperature phases. Zn2V2O7 melts at around 880 °C and has a reversible first-order phase transition at 610 °C [12]. It's worth noting that the low-temperature phase α-Zn2V2O7 mostly has a -thortveitite structure (monoclinic, C2/c) that includes the VO4 units [[13], [14], [15], [16], [17]]. The Zn ions have 6 coordination in the thortveitite-like phase, but some proportion of the cations lower their coordination to five oxygen atoms in both of the low-temperature phases [[16], [17], [18]]. Because the node oxygen atoms in these phases are not all bound to the same number of cations, they are ideal for studying environmental effects on bond lengths. This would automatically influence the corresponding luminescence property of the material.

It is well known that the synthesis process affects the properties of materials. The solid-state method [19,20], hydrothermal approach [21], combustion method [[22], [23], [24]], and microwave method [25] have all been employed to synthesize Zn2V2O7. The structural characteristics of BiVO4 annealed at different temperatures synthesized by the sol-gel technique were reported by Pookmanee et al. [17]. The annealing temperature has been shown to increase emission intensity. Chen et al. [26] reported employing hydrothermal synthesis to make Zn2V2O7 nanoflakes. Other researchers used the solid-state reaction technique to make Zn2V2O7 and discovered agglomerated particles [14]. S. D. Abraham [25] used a microwave-assisted combustion route to synthesize spherical hollow Zn2V2O7 nanospheres. However, no significant work of Zn2V2O7 synthesized using the sol-gel method has been documented so far. The sol-gel process has several benefits over other methods, including a quick reactive time, a low annealing temperature, and a low cost, all of which are promising for industrial manufacturing. Furthermore, the post-annealing process is one of the most important aspects of establishing the structure and qualities of the film. The production of Zn2V2O7 via the sol-gel method is described in this work. The material properties of Zn2V2O7 such as morphology, structure, and size can be altered via the sol-gel method by adjusting parameters such as solvents, pH, growth temperature, precursor concentration, and the duration of the reaction. Short annealing time, lower processing temperature, and good control of particle size and shape distinguish the sol-gel approach from other methods. The impact of different annealing temperatures close to the melting point of Zn2V2O7 on structural and luminescent properties was explored. This work is a continuation of our previous one on the production of yellow Zn2V2O7 phosphors with enhanced efficiency, at low cost, and with no environmental hazards using a solution combustion process [24]. As we have previously reported, in contrast to other findings [27], it was found that the XRD structure obtained was a single phase at higher synthesis temperatures and the best luminescence intensity, in this case, was obtained for samples synthesized at 850 °C.

2. Experimental procedure

High-purity (Aldrich make, 99.99%) raw materials, zinc nitrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O), ammonium metavanadate (NH4VO3), and citric acid (C6H8O7), were used to prepare Zn2V2O7 phosphors by sol-gel process. The materials were weighed in stoichiometric ratios and were all dissolved in 10 ml of deionized water. The resulting, yellow-colored solution was heated to 80 °C while being stirred. Under magnetic stirring, the solution transformed from yellow to black, green, and eventually blue ink gel. It was possible to see the final green gel solution. The green gel was then dried for 6 h at 100 °C and annealed for 2 h at 700–850 °C. The crystalline structure, phase purity, and particle sizes of the produced phosphors were explored using a powder X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bucker D8 Advance) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.1541 nm). A Shimadzu SSX-550 SEM equipped with an electron dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) was used to analyze the morphology and chemical content of the samples. The thermogravimetric analysis was carried out using a PerkinElmer TGA7 thermogravimetric analyzer with a flow rate of 20 ml min−1 in a nitrogen atmosphere. Under a nitrogen environment, thermal calorimetry was performed with a PerkinElmer Pyris-1 differential scanning calorimeter (20 ml min−1). On a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Model: LS 55) with a built-in 150 W xenon lamp as the excitation source, the photoluminescence (PL) measurements were carried out at room temperature. A 325 nm laser was used to stimulate each sample after it had been placed into a circular holder.

3. Results and discussion

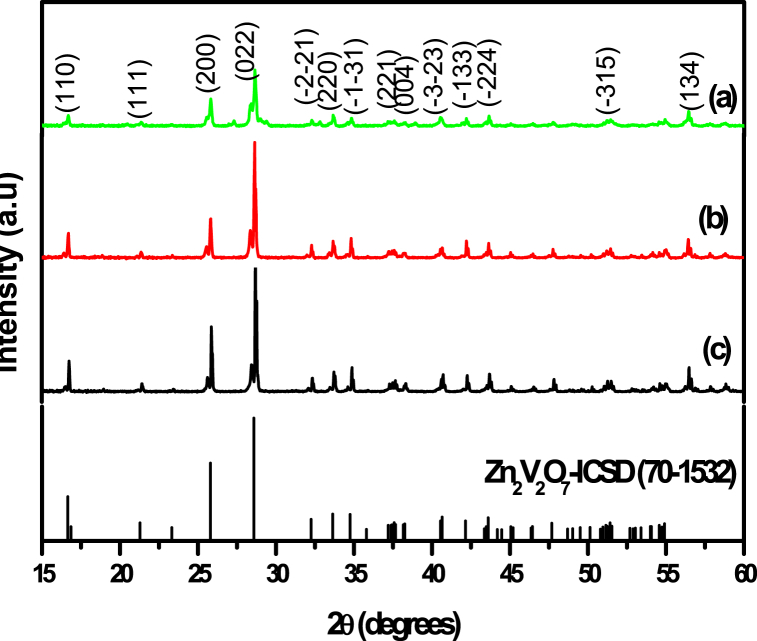

To investigate the thermal and structural behaviour of Zn2V2O7 phosphor, TGA and DSC were utilized. Fig. 1 (a) and (b) show the TGA and DSC findings of Zn2V2O7 phosphors that contain (Zn(NO3)2, NH4VO3, and C6H8O7) which are the row constituents. In a temperature range of 30–110 °C, the measurements indicate an endothermic peak in the DSC curve, which corresponds to the initial weight loss. TGA results reveal total decomposition at 500 °C through three steps. Zn2V2O7 phosphor product displayed slight weight loss (up to 7 wt%) till 110 °C and a second loss till 300 °C (of 45 wt%) and a third loss between 300 and 500 °C (13 wt%) and kept constant weight till 700 °C. The elimination of water is responsible for the initial endothermic weight loss from 110 to 160 °C. The breakdown of Zn2V2O7 into its constituents causes (oxides of Zn and V) the second weight loss from 160 to 350 °C. From 300 to 500 °C, there is an endothermic process occurs causing weight loss of 13 wt%. When the temperature is elevated from 300 to 500 °C, TGA shows a total weight loss of approximately 65 wt%. Above 500 °C, no substantial weight loss has been observed. Crystallization of Zn2V2O7 is responsible for the stable residue that can withstand temperatures up to 700 °C. As a result, the thermal treatment for the investigated samples was carried out at temperatures exceeding 500 °C. Fig. 2 shows the x-ray diffraction pattern of Zn2V2O7 powders reheated for 2 h at 700–850 °C. All the diffraction patterns were well indexed as monoclinic Zn2V2O7 structures (ICSD 70–1532). There were no peaks of any additional phases or contaminants found. In Fig. 2, all diffraction peaks of the Zn2V2O7 monoclinic structure are present and are sharp even at the lowest annealing temperature of 700 °C, insinuating that the material had crystallized completely. The peaks are all indexed to the corresponding miller indices. The peak intensities increased significantly while the line width of the diffraction peaks of the samples decreased as the annealed temperature rose from 700 °C to 850 °C, i.e., the crystallinity of the phosphors has been steadily improving. Moreover, the (022) peak's intensity is substantially larger than the others, indicating that Zn2V2O7 has a strong preference for crystallization orientation, with the (022) crystal plane being its preferred plane. At greater annealing temperatures, the samples become extremely crystalline. From the XRD data analysis, structural parameters such as the lattice constant (a), inter-planar spacing (d), the crystallite size (D), dislocation density (δ), and microstrain (ε) were computed. The crystalline quality of Zn2V2O7 crystallites was measured using the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the (022) peak. According to Scherrer's Equation (1), full width at half maximum (FWHM) is inversely related to crystallite size Ds:

| (1) |

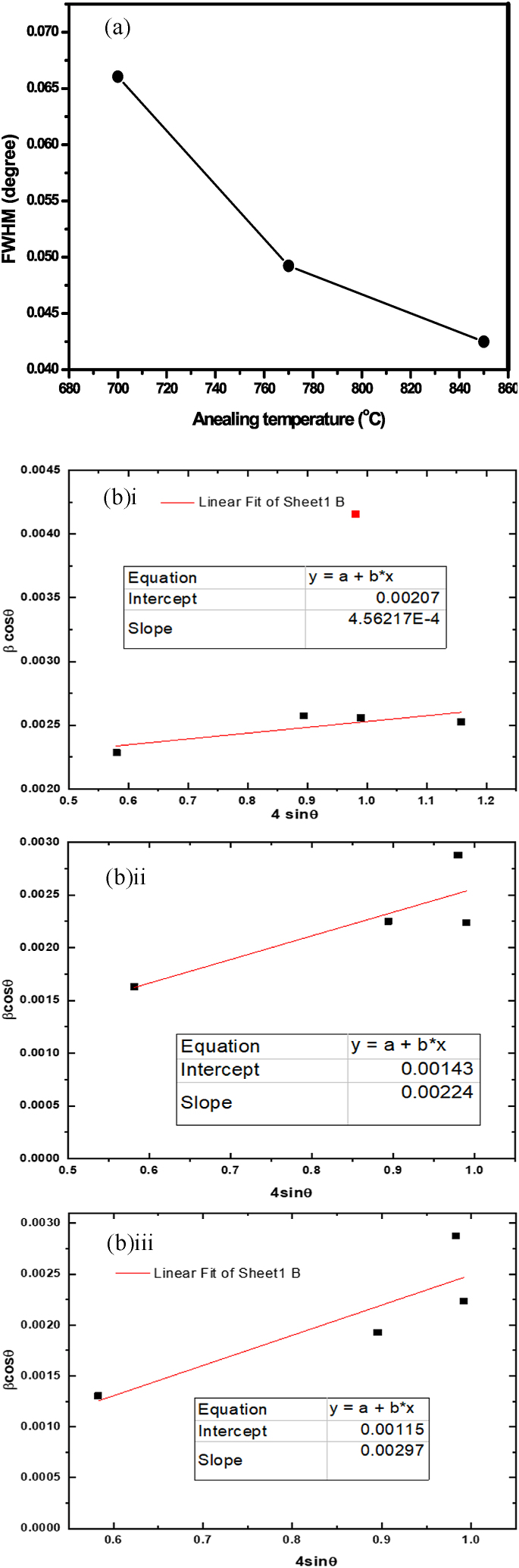

where Ds is the size of the particle, K is known as the Scherer's constant (K = 0.94), λ is the X-ray wavelength (1.541 nm), β is full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak, and θβ is the angle of diffraction. As the annealed temperature went from 700 to 850 °C, the FWHM reduced from 0.066° to 0.042°, as illustrated in Fig. 3a and Table 1. The average particle size of the Zn2V2O7 phosphors is clearly affected by the annealing temperature. Particle size was estimated to rise from 54 nm (61 nm) at 700 °C to 76 nm (82 nm) at 850 °C, according to Scherrer's formula (W–H analysis). The estimated average lattice parameters of Zn2V2O7 phosphors were a = 7.429, b = 8.834, and c = 10.09, which are similar to earlier studies' findings that the lattice parameters are temperature dependent [28]. Equation (2) was used to derive the lattice constant and inter-planar spacing for the major peak at (022):

| (2) |

where λ is the wavelength of the X-ray radiation, β represents the full width at half maximum (FWHM), θ is the angle of diffraction, and ε represents the microstrain that existed in the samples. Peak broadening occurs in prepared phosphors not only as a result of crystallite size but also as a result of existing strain. Strain and crystallite size effects are not related to peak broadening, and they can be separated using W–H (Fig. 3b). W–H analysis is an integral breadth method in which the peak width as a function of 2θ is used to determine size-induced and strain-induced broadenings. The slope and y-intercept of the fitted line are used to compute strain and crystallite size respectively, as shown in Fig. 3b. The results match those predicted by the Scherrer formula but are slightly larger due to strain effects. The dislocation density for the sample can be calculated from Eq. (3):

| (3) |

Fig. 1.

(a) TGA and (b) DSC curves of the as-prepared Zn2V2O7 powder produced by the sol-gel method.

Fig. 2.

Room temperature X-ray diffraction patterns of Zn2V2O7 powders annealed at (a) 700 (b) 770 and (c) 850 °C for 2 h.

Figure 3a.

(a) Full width at half maximum (FWHM) values of the (022) XRD peak dependence on the annealing temperature, and (b) a plot of β cos θ against Sin θ of Zn2V2O7 powders annealed at (i) 700 (ii) 770 and (iiiii) 850 °C for 2 h.

Table 1.

Value of calculated structural parameters.

| Annealing temperature (°C) | 700 | 770 | 850 |

|---|---|---|---|

| FWHM (°) | 0.066 | 0.055 | 0.042 |

| DS (nm) | 54 | 70 | 76 |

| DW-H (nm) | 61 | 79 | 82 |

| Strain (ε × 10−4) | 4.56 | 22.4 | 29.7 |

| Dislocation Density (δ × 10−4) | 3.43 | 1.60 | 1.48 |

Table 1 lists the structural characteristics, including crystallite size, dislocation density, and microstrain. The peak broadening of the XRD patterns is what causes the existence of microstrain and dislocation density. The main difference between the two methods is that the Scherrer formula follows a 1/cosθ dependency, whereas the W–H equation follows a tanθ dependency. The microstrain in the sample was also determined using the formula [29] and the diffraction peaks' full width at half maximum (FWHM).

Both the "ε" and "δ" were clearly shown to vary with annealing temperatures. The increase in dislocation density indicated that the prepared Zn2V2O7 phosphors had more surface and lattice defects. Since it has a significant impact on several characteristics of the prepared Zn2V2O7 materials', the dislocation density is also of great importance. In this work, a little strain reduction is stimulated by the annealing temperatures. This phenomenon may happen for a number of causes, such as lattice variation and an increase in crystallite size with annealing temperature. Fig. 4 shows SEM images of Zn2V2O7 samples annealed at (a) 700 °C, (b) 770 °C, and (c) 850 °C. The surfaces of all the Zn2V2O7 samples are extremely smooth. As can be seen from Fig. 4(a) the image of samples prepared at lower temperatures shows the large irregular particles superposed on a smoother surface composed of smaller primary smaller particles of size 0.5–1 μM. The image displays scattered particles at a low temperature of 700 °C. As the temperature was increased to 770 °C (Fig. 4(b)) the microstructure has a mixture of irregular shapes and a few hexagonal shape particles with straight edges. The size of primary smaller particles increases to 1–2 μM. The particles agglomerated slightly as the temperature is raised. By increasing the temperature further (Fig. 4(c)), the original shape of the particles was destroyed at the higher temperature of 850 °C, which might be due to the melting of the particles as seen in Fig. 4(c). The particle size of Zn2V2O7 became larger, culminating in spherical aggregation [30]. A high degree of particle size homogeneity suggests that more annealing is required to get a uniform particle size. The particle size of Zn2V2O7 grew as the annealing temperature increased, indicating that the samples crystallized, as revealed by XRD measurements. Fig. 5 shows the elemental composition of Zn2V2O7 powders generated by the sol-gel technique. The EDS analysis proves the presence of a single phase of Zn2V2O7 powder that consists of zinc (Zn), vanadium (V), and oxygen (O) only.

Fig. 4.

SEM images of Zn2V2O7 phosphor powders produced by sol-gel method and annealed at (a) 700 (b) 770 and (c) 850 °C for 2 h.

Fig. 5.

EDS spectra Zn2V2O7 powder produced by sol-gel.

Fig. 6(a) shows the PL emission spectra of Zn2V2O7 annealed at various temperatures. The broadband from 400 nm to 800 nm, which consists of the two peaks seen in Fig. 6(b), is indicated by the deconvoluted peak of the most intense spectra. The transitions from the 3T2 and 3T1 states to the 1A1 ground state of V5+ ions were seen in the broad yellow-to-green emission band of Zn2V2O7 [31]. When the strongest PL peak at 558 nm is deconvoluted, emissions at 526 and 590 nm are revealed. With increasing annealing temperature, the emission bands of the samples shift towards longer wavelengths. The rise in particle sizes of Zn2V2O7, as revealed in XRD results [32], is linked to this. According to Luwang et al. [33], the shifting of the peak towards a longer or shorter wavelength could be due to an increase in covalent bonding during annealing. Because of a slightly poor crystallinity relative to others, the sample annealed at low temperature has a low emission intensity. The luminescence intensity increases as the annealing temperature rises. Because the crystallinity improved with the annealing temperature, the emission intensity rose. Fig. 6(c) depicts the PL peak intensity of the emission spectra as a function of annealing temperature ranging from 700 to 850 °C. With increasing annealing temperature, the PL peak intensity grew steadily. As shown by XRD measurements, the crystallinity of Zn2V2O7 was improved with annealing temperature. Fig. 7 is a chromaticity diagram from the Commission Internationale de l'Elcairage (CIE). Table 2 summarizes the determined CIE color coordinates for all annealed samples. The CIE coordinate is seen around the green and yellow regions in the Zn2V2O7 samples. When annealed from 700 to 850 °C, the emission color of annealed samples altered from yellow with chromaticity coordinates of x = 0.417 and y = 0.469 to green with coordinates of x = 0.354 and y = 0.501. The sample that was annealed at 770 °C provided the best yellow color.

Fig. 6.

(a) Photoluminescence emission spectra of Zn2V2O7 powder annealed at 700, 770, and 850 °C for 2 h (b) PL emission spectra of Zn2V2O7 annealed at 850 °C fitted with two deconvoluted Gaussian curves. (c): The dependence of PL emission intensity on the annealing temperature.

Fig. 7.

CIE chromaticity diagram and chromaticity coordinates (x, y) of emission from Zn2V2O7 phosphors annealed at 700, 750, and 850 .

Table 2.

CIE chromaticity color coordinates in Zn2V2O7 annealed at different temperatures.

| CIE chromaticity coordinates |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample No. | Sample | x | y |

| 1 | Zn2V2O7-700 °C | 0.373 | 0.464 |

| 2 | Zn2V2O7-770 °C | 0.417 | 0.469 |

| 3 | Zn2V2O7-850 °C | 0.354 | 0.501 |

4. Conclusion

With zinc nitrate and ammonium metavanadate as precursors, the green-yellow emitting Zn2V2O7 phosphor was effectively produced by the sol-gel technique. After 2 h of annealing at 700–850 °C temperatures, a single-phase monoclinic structure of Zn2V2O7 was formed. According to the findings, the annealing temperature affects the structure and morphology. Particle aggregation increased as particle size increased from 54 nm (61 nm) at 700 °C to 76 nm (82 nm) at 850 °C, according to Scherrer's formula (W–H analysis). The crystallization of Zn2V2O7 phosphor causes a total weight loss of approximately 65 wt% when the temperature is elevated from 30 to 500 °C, according to TGA measurement. Beyond 500 °C, no significant weight loss has been seen. The photoluminescence emission spectra of Zn2V2O7 after annealing at various temperatures were studied. The PL emissions due to the transitions of electrons from the 3T2 and 3T1 states to the 1A1 ground state of V5+ ions were observed to slightly shift from broad yellow to green emission with an increase in temperature. The spectral positions of the excitation and emissions bands would fluctuate, which is expected given that the crystal field splitting differs significantly depending on the host material. Based on the emission spectra of annealed Zn2V2O7 samples the CIE coordinates for Zn2V2O7 phosphor could be turned from yellow with coordinates (0.417, 0.469) to green with coordinates (0.354, 0.501).

Author contribution statement

Francis Birhanu Dejene: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, Walter Sisulu University (FNS WSU Research Seed Funding 2022) and CSIR National Laser Centre (LHIN500 task ALC-R008).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Dr. Kewele Emily Foka (deceased) for the preparation and characterization of the samples. The author would like to thank Prof LF Koao for his comments during manuscript preparation and the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions and careful reading of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Debelo N.G., Dejene F.B., Roro K.T. Pulsed laser deposited KY3F10: Ho3+ thin films: influence of target to substrate distance. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2017;190:62–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onani M.O., Dejene F.B. Photo-luminescent properties of a green or red-emitting Tb3+ or Eu3+ doped calcium magnesium silicate phosphors. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 2014;439:137–140. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan T.S., Liu R.S., Baginskiy I. Synthesis, crystal structure, and luminescence properties of a novel green-yellow emitting phosphor LiZn1−xPO4:Mnx for light emitting diodes. Chem. Mater. 2008;20:1215. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy A.A., Das S., Ahmad S., Babu S., Ferreira J.M.F., Prakash G.V. Influence of the annealing temperatures on the photoluminescence of KCaBO3:Eu3+phosphor. RSC Adv. 2012;2:8768. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y., Yu Y.M., Tsuboi T., Seo H.J. Novel yellow-emitting phosphors of Ca5M4(VO4)6 (M=Mg, Zn) with isolated VO4 tetrahedra. Opt Express. 2012;20:4360–4368. doi: 10.1364/OE.20.004360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukhtar S., Zou C., Gau W. Zn3(VO4) 2 prepared by magnetron sputtering: microstructure and optical property. Appl. Nanosci. 2013;3:535–542. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y.Q., Delsing A.C.A., With G.D., Hintzen H.T. Luminescence properties of Eu2+-activated alkaline-earth silicon-oxynitride MSi2O2-δN2+2/3δ (M = Ca, Sr, Ba): a promising class of novel LED conversion phosphors. Chem. Mater. 2005;17:3242. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang M.S., Guo S.P., Li Y., Cai L.Z., Zou J.P., Xu G., Zhou W.W., Zheng F.K., Guo G.C. A direct white-light-emitting Metal−Organic framework with tunable yellow-to-white photoluminescence by variation of excitation light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131 doi: 10.1021/ja903947b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das S., Reddy A.A., Babu S.S., Prakash G.V. Controllable white light emission from Dy3+–Eu3++ co-doped KCaBO3 phosphor. J. Mater. Sci. 2011;46:7770. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pookmanee P., Kojinok S., Phanichiphant S. Bismuth vanadate (BiVO4) powder prepared by the sol-gel method. J. Met. Mater. Miner. 2012;22:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang L.L.Y., Wang F.Y. Li-(Mg,Zn,Ni) Vanadate's. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1988;71:689–693. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan Y., Yu Y., Wu D., Yang Y., Cao Y. Vanadate (Sr10V6O25, NI3V2O8, Zn2V2O7) Heterostructured photocatalysts with enhanced photocatalytic activity for photoreduction of CO2 INTO CH4. Nanoscale. 2016;8:949–958. doi: 10.1039/c5nr05332c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butt F.K., Tahir M., Cao C., Idrees F., Ahmed R., Khan W.S., et al. Synthesis of novel ZnV2O4 hierarchical nanospheres and their applications as electrochemical supercapacitor and hydrogen storage material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6:13635e41. doi: 10.1021/am503136h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuang S.P., Meng Y., Liu J., Wu Z.C., Zhao L.S. A new self-activated yellow-emitting phosphor Zn2V2O7 for white. LED Optik. 2013;124:5517–5519. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercurio-Levand D., Frit B. Thermoelectric properties and phase transition of (ZnxCu2-x)V2O7. Comp. Rend. Acad. Sci. (Paris) Ser. C. 1973;277:1101–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopal R., Calvo C. Crystal structure of a- Zn2V2O7. Can. J. Chem. 1973;51:1004–1009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zavalij P.Y., Zhang F., Whittingham M.S. The zinc–vanadium–oxygen–water system: hydrothermal synthesis and characterization. Solid State Sci. 2002;4:591–597. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson B.E., Calvo C. The crystal structure and phase transformation of α-Cu2P2O7. Acta Crystallogr. 1967;22:665. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luitel H.N., Watari T. Color tunable persistent luminescence in M2MgSi2O7:Eu2+, Dy3+ (M=Ca,Sr,Ba) phosphor with controlled microstructure. J. Appl. Chem. Sci. Int. 2016;7(2):76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grandhe B.K., Ramaprabhu S., Buddhudu S., Sivaiah K., Bandi V.R., Jang K. Spectral characterization of novel LiZnVO4 phosphor. Opt Commun. 2012;285:1194–1198. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang M., Shi Y., Jiang G. 3D hierarchical Zn3(OH)2V2O7· 2H2O and Zn3(VO4)2 microspheres: synthesis, characterization and photoluminescence. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012;47:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chellappa J., Abraham S.D., Biju Bennie R., Theodore David S. Microwave assisted synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity of Zn2V2O7 nanospheres. Chem. Sci. Trans. 2014;3(4):1488–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammed R.M., Harraz F.A., Mkhalid I.A. Hydrothermal synthesis of size-controllable Yttrium Orthovanadate (YVO4) nanoparticles and its application in photocatalytic degradation of direct blue dye. J. Alloys Compd. 2012;532:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foka K.E., Dejene B.F., Koao L.F., Swart H.C. Structural and luminescence properties of self-yellow emitting undoped and (Ca, Ba, Sr)-doped Zn2V2O7 phosphors synthesized by combustion method. Phy B Condens. Mater. 2018;535:245. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abraham S.D., T David S., Bennie R.B., Joel C., Seethalakshimi M., Adinaveen T. Microwave assisted synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic activity of Zn2V2O7 nanospheres. Chem. Sci. Trans. 2014;3(4):1488–1496. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Z., Huang W., Lu D., Zhao R., Chen H. Synthesis of calcium phosphate fluoride hybrid hollow spheres. Mater. Lett. 2013;107:35–38. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuang S.P., Meng Y., Lui J., Wu Z.C., Zhao L.S. A new self-activated yellow-emitting phosphor Zn2V2O7 for white LED. Optik. 2013;124:5517–5519. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiyagarajan P., Kottaisamy M., Ramachandra Rao M.S. Improved luminescence of Zn2SiO4:Mn green phosphor prepared by gel combustion synthesis of ZnO: Mn–SiO2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007;154:H297–H303. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson G.H., hall W.H. X-ray broadening from field aluminum and wolfram. Acta Metall. 1953;1:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashemi Amiri S.E., Vaezi M.R., Esmaielzadeh Kandjani A. A comparison between hydrothermally prepared Co3O4 via H2O2 assisted and calcination methods. J. Ceram. Process. Res. 2011;12:327–331. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X., Xia Z., Yi M., Wu X., Xin H. Rare-earth free self-activated and rare-earth activated Ca2NaZn2V3O12 vanadate phosphors and their color-tunable luminescence properties. J. Phys. Chem. Solid. 2013;74:1439–1443. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shayestehad S.F., Ahmad A., Zgahj D.I. Effect of doping and annealing on the physical properties of ZnO: Mg nanoparticles. J. Phys. 2013;81:319–330. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luwang M.N., Ningthoujam R.S., Srivastava S.K., Vatsa R.K. Preparation of white light-emitting YVO4: Ln3+and silica-coated YVO4:Ln3+ (Ln3+= Eu3+, Dy3+, Tm3+) nanoparticles by CTAB/n-butanol/hexane/water microemulsion route: energy transfer and site symmetry studies. J. Mater. Chem. 2011;21:5326–5337. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.