Abstract

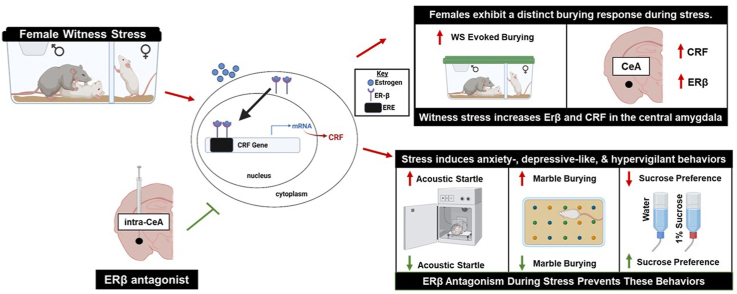

While over 95% of the population has reported experiencing extreme stress or trauma, females of reproductive age develop stress-induced neuropsychiatric disorders at twice the rate of males. This suggests that ovarian hormones may facilitate neural processes that increase stress susceptibility and underlie the heightened rates of these disorders, like depression and anxiety, that result from stress exposure in females. However, there is contradicting evidence in the literature regarding estrogen's role in stress-related behavioral outcomes. Estrogen signaling through estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) has been traditionally thought of as anxiolytic, but recent studies suggest estrogen exhibits distinct effects in the context of stress. Furthermore, ERβ is found abundantly in many stress-sensitive brain loci, including the central amygdala (CeA), in which transcription of the vital stress hormone, corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), can be regulated by an estrogen response element. Therefore, these experiments sought to identify the role of CeA ERβ activity during stress on behavioral outcomes in naturally cycling, adult, female Sprague-Dawley rats. Rats were exposed to an ethological model of vicarious social stress, witness stress (WS), in which they experienced the sensory and psychological aspects of an aggressive social defeat encounter between two males. Following WS, rats exhibited stress-induced anxiety-like behaviors in the marble burying taskand brain analysis revealed increased ERβ and CRF specifically within the CeA following exposure to stress cues. Subsequent experiments were designed to target this receptor in the CeA using microinjections of the ERβ antagonist, PHTPP, prior to each stress session. During WS, estrogen signaling through ERβ was responsible for the behavioral sensitization to repeated social stress. Sucrose preference, acoustic startle, and marble burying tasks determined that blocking ERβ in the CeA during WS prevented the development of depressive-, anxiety-like, and hypervigilant behaviors. Additionally, brain analysis revealed a long-term decrease of intra-CeA CRF expression in PHTPP-treated rats. These experiments indicate that ERβ signaling in the CeA, likely through its effects on CRF, contributes to the development of negative valence behaviors that result from exposure to repeated social stress in female rats.

Keywords: Estrogen receptor beta, Social stress, Anxiety, Central amygdala, Corticotropin releasing factor

Abbreviations: CeA, central amygdala; CRF, corticotropin releasing factor; WS, witness stress; ERβ, estrogen receptor beta; PHTPP, 4-[2-Phenyl-5: 7-bis (trifluoromethyl) pyrazolo [1,5-a] pyrimidine-3- yl] phenol; CORT, corticosterone; HPA, hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CON, control handing; SPT, sucrose preference testing; ASR, acoustic startle responding; EPM, elevated plus maze; dB, decibels; MB, marble burying; BCA, bicinchoninic acid; LC, locus coeruleus

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Social stress increases anxiety-, hypervigilant, and depressive-like behaviors.

-

•

Repeated witness stress increases ERβ and CRF in the CeA of females.

-

•

Intra-CeA ERβ antagonism blocks the development of hypervigilance.

-

•

ERβ antagonism leads to persistent reductions in CeA CRF expression.

-

•

Stress-related estrogen may represent a target for stress susceptibility in women.

1. Introduction

Social stressors are one of the most commonly experienced and highly impactful forms of stress in the clinical population. Exposure to these stressors is a risk factor for the development of many neuropsychiatric and physical health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease (Pêgo et al., 2010). As a leading cause of disability, such stress-related conditions pose a significant burden on both the patient and society. While the overall incidence of mental health disorders is around 30%, females exhibit over twice the rate of neuropsychiatric conditions, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder, when compared to males, possibly due to increased exposure and vulnerability to stress (Sandanger et al., 2004). Importantly, this incidence is not correlated with differences in demographic factors such as marital status, employment, or number of children (Klose and Jacobi, 2004; Steel et al., 2014). Therefore, neurobiological factors inherent to females may underlie this increased prevalence of mental health disorders following stress exposure.

Despite a large body of literature suggesting that, in healthy patients, estrogen mediates protective effects under non-stressful conditions, recent advances in the field have established estrogen as a factor that may promote susceptibility to the consequences of stress (Finnell et al., 2018; Hokenson et al., 2021; Morgan and Pfaff, 2001; Morgan et al., 2004). Higher levels of circulating estrogen increase physiological and neuroendocrine responses to stress (Lund et al., 2006) and, in post-menopausal women without circulating estrogen, injections of estrogen lead to a heightened response to laboratory administered social stressors (Newhouse et al., 2010). Stress sensitization in the presence of estrogen is also replicated in preclinical models. Elevated levels of estrogen in rodent models promotes an exaggerated release of stress hormones including corticotropin releasing factor (CRF), a critical regulator of the stress response, and amplifies neuronal activation of brain regions responsible for the production of these hormones (Babb et al., 2013; Handa et al., 1994; Lund et al., 2006; Viau et al., 2005; Zuloaga et al., 2020). Importantly, the CRF gene contains an estrogen response element which allows nuclear estrogen receptor (ER) activation to modulate CRF transcription (Ni and Nicholson, 2006; Vamvakopoulos and Chrousos, 1993). Thus, estrogen may promote stress susceptibility in females through its direct actions on CRF (Heck and Handa, 2019; Zuloaga et al., 2020).

Due to these known interactions with CRF, estrogen signaling within specific stress-sensitive brain regions may be instrumental in exacerbating stress sensitivity in females. The central amygdala (CeA) is one such region that contains a prominent CRF network that is activated in response to stress (Herringa et al., 2004; Kalin et al., 2004; Pomrenze et al., 2019). This region is also critically involved in regulating behaviors related to hypervigilance, including the acoustic startle response (Liang et al., 1992) and long-term negative responses to stress cues (Weera et al., 2021). Further, the CeA extends dense CRF projections to the locus coeruleus (LC), a brain region known to integrate multiple aspects of the stress response and is responsible for the emergence of hypervigilant behaviors (Howard et al., 2008; Valentino and Van Bockstaele, 2008). Importantly, estrogen is also able to modulate cellular activity of the CeA by signaling through ER-beta (ERβ), the predominant ER subtype in this region (Osterlund et al., 1998; Shughrue and Merchenthaler, 2001). While ERβ has traditionally been shown to be anxiolytic (Lund et al., 2005), this effect is only exhibited in behavioral tasks among naïve rats without a history of stress (Le Moëne et al., 2019). The dichotomous role of ERβ activity is revealed in rats that are exposed to stress prior to testing on measures of anxiety-like behaviors, suggesting that ERβ may, instead, have anxiogenic effects in the context of stress (Jasnow et al., 2006; Lynch et al., 2014). Therefore, these experiments sought to identify a specific role for intra-CeA ERβ in the negative behavioral responses to social stress that have been observed in female rats. Previous experiments in our lab using the witness stress model in females have determined that cycling ovarian hormones are required for behavioral susceptibility to social stress (Finnell et al., 2018), thus, these studies were designed to explore the neuronal mechanisms responsible for the estrogen-mediated behavioral responses to stress. Specifically, these studies determined 1) how expression of ERβ and CRF are altered in the CeA following social stress exposure in females and 2) if pharmacological blockade of ERβ during stress prevents the development of hypervigilant behavioral responses to repeated social stress.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental design

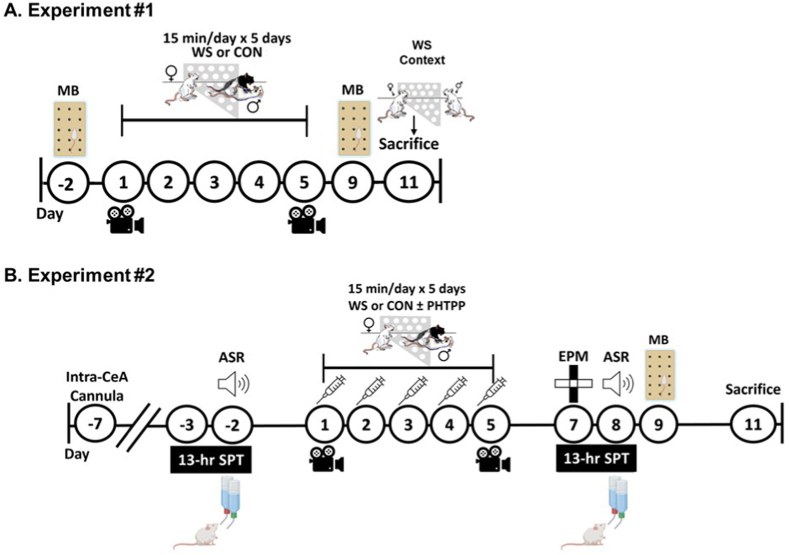

Two main experiments were completed under the hypothesis that, during stress exposure, estrogen signals through ERβ to promote CRF expression (as outlined in Fig. S1C), leading to heightened stress responsivity in females. Rats in Experiment #1 (Fig. 1A, n = 6/treatment group) were tested on a baseline marble burying task to establish pre-stress levels of hypervigilant behaviors prior to exposure to five days of witness stress (WS) or control handling (CON). Subsequently, marble burying tests were completed post-stress to determine the impact of social stress on this index of hypervigilant behavior, and finally, tissue collection occurred following exposure to the WS/CON context to serve as a stress cue (methods fully described in Section 2.6.6). Rats in Experiment #2 (Fig. 1B, n = 12–15/treatment group) were implanted with indwelling bilateral microinjection cannulas into the CeA and received injections of the selective ERβ antagonist, PHTPP, or vehicle 1 h prior to each of the five daily WS/CON exposures (15 min/day for 5 consecutive days). Rats underwent pre- and/or post-stress behavioral assays, as described in the timeline in Fig. 1B, including sucrose preference, acoustic startle, marble burying, and elevated plus maze, followed by tissue collection at rest.

Fig. 1.

Experimental Timelines. Two separate experiments were completed to determine the role of CeA ERβ signaling in the development of hypervigilant behavioral responses to repeated social stress in females. A) Rats in Experiment #1 were first assessed in a marble burying test (MB) to establish baseline levels of anxiety-like behavior, then were exposed to five consecutive days of WS or CON (15 min/day). Sessions were recorded and behaviors were assessed on days #1 (D1) and #5 (D5). WS/CON rats underwent a post-WS/CON MB test to determine how exposure to repeated WS affects measures of hypervigilant and anxiety-like behaviors. Six days after the final WS/CON exposure, rats were re-exposed to the context in which they originally experienced either WS (but in the absence of the resident) or CON for 15 min. Brains were collected 30 min after the start of WS/CON context exposure. B) For Experiment #2, all rats were implanted with indwelling bilateral cannulas into the CeA. Following surgical recovery, a pre-stress testing regimen commenced to assess baseline sucrose preference (SPT) and acoustic startle response (ASR). Subsequently, rats were exposed to five consecutive days of WS/CON (15 min/day) with local microinjection of either vehicle or the ERβ antagonist, PHTPP, into the CeA 1 h prior to each WS/CON session. Post-WS/CON behavioral testing consisted of the elevated plus maze (EPM), SPT, ASR, and MB, each separated by 24 h, to determine if ERβ blockade, through PHTPP, prevented the development of hypervigilant, anxiety-like, and reward motivated behaviors. Tissue was collected at rest two days following the final behavioral test. CeA: Central Amygdala; ERβ: estrogen receptor beta.

2.2. Animals

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (8–9 weeks and ∼150 g on arrival, witnesses and controls; Charles River, Raleigh, NC), male Sprague-Dawley rats (∼250 g on arrival, intruders; Charles River, Raleigh, NC), and male Long-Evans retired breeders (600–800 g, residents; Envigo, Dublin, VA) were all housed individually in standard polycarbonate cages and maintained on a 12:12 light:dark cycle with lights on at 0700 h and ad libitum access to standard rat chow and water, except during behavioral testing. Additionally, female rats that experienced control conditions were housed in an adjacent room from the stressed females and male rats but maintained the same environment and care. Further, all rats were maintained in individual housing conditions for the duration of these studies. These experiments were approved by the University of South Carolina's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and maintained adherence to the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.3. CeA cannulation surgery

Rats in Experiment #2 were implanted with indwelling bilateral cannulas (26 ga., P1 Technologies, Roanoke, VA) aimed to terminate directly dorsal to the CeA (in mm from bregma and the surface of the dura, A/P: 2.3; M/L: ±4.1, D/V: 6.5). Post-operative analgesic injections (Flunazine, 0.25 mg/kg, s.c.) were given on the day of and day following surgery, along with nutritional supplementation (Bacon Softies, Bio-Serv, Flemington, NJ), and rats were given at least 7 days of recovery prior to the start of pre-stress testing.

2.4. Witness stress/control handling

Females from both Experiment #1 and Experiment #2 were exposed to 15 min of either WS or CON each day for five consecutive days. Witness Stress: During each WS session, the female witness was placed behind a clear, perforated, acrylic partition in a protected region (10 × 5 cm) of a resident's home cage. Immediately after placement of the witness, a male intruder was placed into the side of the cage with the resident and social defeat commenced. This paradigm allows the witness to observe auditory, olfactory, and visual cues without physical aspects of social defeat (Finnell et al., 2018; Pate et al., 2023). Matched witness-intruder pairs for all five WS sessions were exposed to a novel resident each day to prevent habituation. Prior to experimentation, residents were screened for appropriate levels of aggression and those that either did not respond to an intruder or caused physical injury to intruders were excluded. Controls: We have previously shown that placing naïve females behind a partition in a novel cage in the presence of a male intruder, but in the absence of the resident/social defeat, does not induce a burying response and produces comparable behavioral effects to daily handling in females (Finnell et al., 2018). Further, in this study, a subset of rats were subjected to similar conditions to replicate these results. Females were placed behind the partition in a novel empty cage and burying behavior was measured (Fig. S3). The burying response measured in the control condition (handled and returned to home cage) was comparable to burying in females placed behind a partition in a novel cage (Fig. S3). These results confirmed that transfer to a novel cage behind a partition does not induce a burying response. Therefore, control rats for Experiments #1 & 2 were briefly handled daily then returned to their home cage (CON).

2.5. Drug information

One hour prior to each WS/CON exposure, females in Experiment #2 received either vehicle (10% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO], Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) in saline, or the potent and selective ERβ antagonist, 4-[2-Phenyl-5,7-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolol[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]phenol (PHTPP, 10 μM dissolved in 10% DMSO, TOCRIS, Minneapolis, MN), microinjected bilaterally into the CeA (0.5 μL over 1 min with a 1-min wait post-infusion) (Compton et al., 2004). This dose was chosen based on a dose response pilot in which 0, 1, 3 and 10 μM of PHTPP were administered prior to WS. It was determined that 10 μM was the only dose that effectively reduced WS-evoked CRF expression in the CeA compared to vehicle (Fig. S1A) and, thus, was the dose used for all further experiments.

2.6. Behavioral assays

2.6.1. Behavior during WS/CON

WS/CON sessions were video-recorded on the first (D1) and last (D5) day of exposure, and behaviors including rearing, freezing, and stress-evoked burying (Finnell et al., 2018; Pate et al., 2023) were manually quantified retrospectively by an experimenter blinded to treatment groups using ANY-maze (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL). Scores were validated by a second blinded experimenter. Briefly, behaviors were defined by the following criteria: stress-evoked burying was rapid, non-exploratory digging or pushing of the bedding; freezing was complete immobility with the exception of respiratory movements and vocalizations; and rearing was upward extension of the rat's body while simultaneously raising both forepaws from the bedding with or without the hindlimbs extended, in the absence of grooming, eating, or drinking. Importantly, the burying exhibited during stress is a spontaneous and rapid burying of the cage bedding and is a distinct phenomenon separate from the behaviors observed during the marble burying paradigm where the burying of a discrete object is measured. Analyses included the latency to the first occurrence of each behavior as well as the total duration of each behavior throughout the 15-min session.

2.6.2. Sucrose preference test (SPT)

To assess the role for intra-CeA ERβ on WS-induced reductions in reward seeking, rats in Experiment #2 underwent a two-bottle choice SPT performed three days pre-as well as three days post-WS/CON exposure. The SPT paradigm utilized in previously published experiments (Finnell et al., 2018) was completed with minor modifications: Phase 1 - for the first 24 h, rats were acclimated to the presence of two bottles in their home cage filled with standard drinking water; Phase 2 - rats had free access to two standard bottles filled with 1% sucrose in standard drinking water for the next 24 h; Phase 3 - rats were water deprived for 10 h prior to the start of the dark cycle (1900 h), when two bottles, one with standard drinking water and one with 1% sucrose, were placed in the cage overnight for 13 h. The location of the bottles was switched at 2000 h to rule out the potential for side bias. Total liquid consumption was measured by subtracting bottle weights at the end of the 13 h from weights at the start of the test. Percent sucrose preference was calculated as follows:

Rats were excluded if they exhibited sucrose aversion indicated by a sucrose preference below 60% in the pre-stress SPT (CON + VEH, n = 1; CON + PHTPP, n = 2). Data are presented as the change in percent sucrose preference from pre-to post-stress to determine how stress specifically alters this measure of reward seeking.

2.6.3. Acoustic startle response (ASR)

ASR testing utilized the automated SR-LAB Startle Response System (San Diego Instruments San Diego, CA). Briefly, this system consists of a sound-attenuating isolation cabinet which contains an acrylic enclosure placed over an accelerometer. Females in Experiment #2 were tested three days prior to and three days following WS/CON exposure to determine how WS specifically alters the hypervigilant startle response. While this testing occurred the day following SPT, rats maintained access to water for the 16 h preceding the start of ASR and, therefore, were not tested under water deprived conditions. Each session lasted for approximately 30 min beginning with an initial 5-min habituation period of exposure to a constant 65-dB tone (background), followed by 30 total trials that included 10 trials each of 95, 105, and 115 dB tones played in 50-ms bursts. Tones were presented in a pseudorandom order with inter-trial intervals that varied between 35 and 45 s. This task elicits an unconditioned startle reflex that has previously been established as a translational method of measuring hypervigilance (Koch and Schnitzler, 1997; Poli and Angrilli, 2015). Since our ongoing experiments indicate that WS impacts startle at the 105 dB level (unpublished) in accordance with the current literature (Börchers et al., 2022), data were analyzed at 105 dBs as the change in startle velocity (V Max) from pre-to post-WS/CON testing.

2.6.4. Elevated plus maze test (EPM)

Rats in Experiment #2 were tested on the EPM two days following the end of stress. On the day of testing, rats were transported to the testing room at least 30 min prior to the start for environmental habituation. The maze was placed 52 cm above the ground and consisted of five total zones: a 10 × 10 cm central square (center zone) that connected two opposing 50 × 10 cm extensions enclosed by 40 cm-tall side walls (closed arms) and an additional two opposing 50 × 10 cm extensions without side walls (open arms). Each rat was placed into the center zone facing an open arm, and the session was video recorded to track location of the animal for the duration of the 5-min session. Videos were automatically scored using ANY-maze to determine the total time spent in each section of the apparatus and the total distance traveled. This technique provides a measure of general anxiety-like and risk averse behavior based on rodents’ inherent aversion to the unfamiliar open spaces (i.e., the open arms) and the efficacy of anxiolytics to reduce this aversion (Kraeuter et al., 2019).

2.6.5. Marble burying test (MB)

Rats in both experiments were tested in the marble burying paradigm, a behavioral task used to assess general anxiety-like and hypervigilant behavior in rodents based on defensive burying of a neutral object (Dixit et al., 2020). The testing chamber consisted of a novel, clean, standard rat cage with Teklad sani-chip bedding (5 cm-deep, leveled), the same bedding used for all rat's home cages (Envigo, Dublin, VA). Fifteen glass marbles (1.5 cm in diameter) were arranged in 3 × 5 rows evenly distributed across the bedding (Fig. 3A). Rats were placed into the cage such that the marbles were not disturbed, and behaviors were video recorded for 15 min. Upon completion, rats were carefully removed so as not to disturb final marble location, and the number of marbles buried was recorded. A marble was counted as buried if ¾ or more of the marble was covered in bedding. To confirm the covering of a buried marble as intentional, videos were reviewed by a researcher blinded to the treatment conditions. Durations of marble burying and marble interaction (defined as any physical manipulation of the marble excluding burying) during the 15-min testing period were manually quantified using ANY-maze. Rats in Experiment #1 underwent a pre- and post-stress test while rats from Experiment #2 underwent only post-stress MB testing. Thus, MB data from Experiment #1 are presented as change from pre-stress and as a repeated measure while MB data from Experiment #2 represent only behavior during the single MB test conducted following WS exposure.

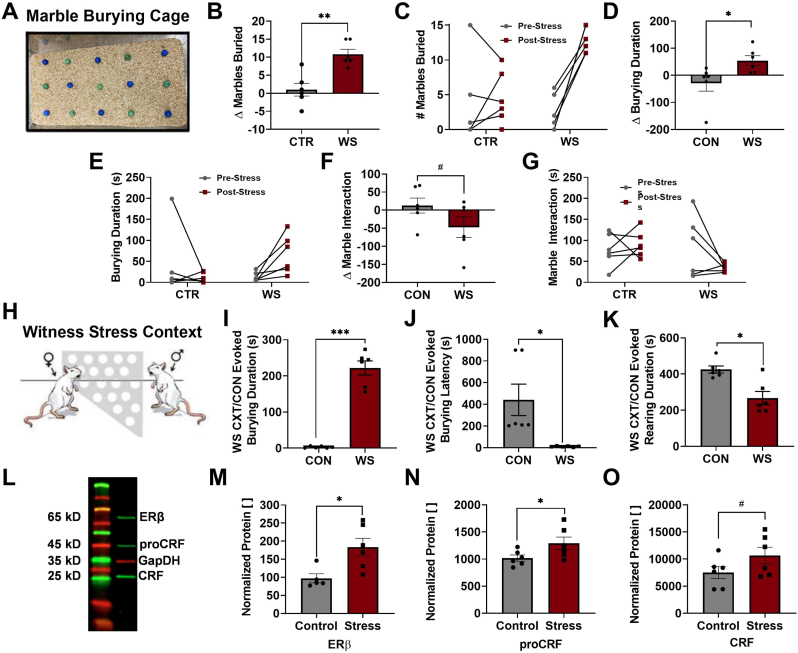

Fig. 3.

Exposure to social stress increases indices of anxiety-like and hypervigilant behaviors and induces neuronal alterations in the CeA. When compared with pre-stress behaviors in the MB test (apparatus pictured, A), WS-exposed rats increased the number of marbles buried (B), which was confirmed by analyzing repeated measures between D1 and D5 (C), as well as the overall time spent burying (D) that was also significantly affected by stress when analyzing these data to include repeated measures (E). This was accompanied by a decrease in the amount of time spent interacting with the marbles (F), and this significant difference was also reflected in analysis of repeated measures (G). Further, when exposed to the context and environment in which they originally experienced WS or CON (H), WS rats exhibited a significantly heightened amount of time spent spontaneously burying the cage bedding (I) along with a decreased latency to begin burying (J) when compared to CON CXT. The enhanced burying response during WS CXT was also accompanied by a reduction in rearing exhibited in WS rats when compared to CON (K). Brain tissue was collected 30 min after the start of WS/CON CXT exposure and processed using Western blot analysis for ERβ and CRF normalized to GapDH (L). Within the CeA, WS rats displayed augmented expression of ERβ (M), the CRF precursor proCRF (N), and the mature CRF protein (O) (n = 6/group with the exception statistical of outliers, #p < 0.07, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0001, unpaired t-tests). CeA: central amygdala; MB: marble burying; WS: witness stress; CXT: context; CON: control; ERβ: estrogen receptor beta; CRF: corticotropin releasing factor.

2.6.6. Witness stress context exposure

On the day of tissue collection, rats from Experiment #1 were exposed to the context in which they originally experienced WS/CON to allow for quantification of stress cue-evoked changes in behavior and neural alterations. Females with a history of WS were placed behind a partition in a soiled resident's home cage with their paired male intruder on the opposite side in the absence of the resident. The resident's cage used for context exposure was from the same rat that was used as a resident on the final day of stress for each witness. Females with a history of CON were briefly handled then returned to their home cages. Context exposure sessions were video recorded for 15 min and behaviors were assessed identically to WS/CON as described above (Section 2.6.1).

2.7. Tissue collection

Brains were collected 30 min after the start of WS/CON context exposure for rats in Experiment #1. For rats in Experiment #2, brains were collected under resting home cage conditions two days after the final behavioral test. Rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane vapor prior to decapitation. Brains were dissected into anterior and posterior sections, flash-frozen in isopentane chilled on dry ice, and stored at −80 °C. Anterior sections were sliced coronally, and 1 × 1 mm (diameter x depth) bilateral punches of the CeA were taken using a tissue biopsy punch (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) prior to storage at −80 °C until processing. Histological assessment verified accuracy of punch placement at 10X magnification (Fig. S1B). Brain slices from female rats in Experiment #2 were also assessed to confirm cannula placement within the CeA (Fig. S4). Additionally, a separate rat was injected with Hoechst dye (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) into the CeA to ensure drug spread was limited to the CeA. The spread of the dye was measured at a total area of 153976 pixels2 while the entire area of the CeA was established as 388980 pixels2, further reinforcing that drug spread was limited to approximately half of the total area of the CeA bilaterally.

2.8. Brain tissue processing

CeA punches were homogenized and assessed for protein concentration using a Pierce Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) per manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, each sample was mixed with 100 μL of zirconium oxide beads (Next Advance, Inc., Troy, NY) and 200 μL of lab-made lysis buffer consisting of 137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 1% Igepal, 10% glycerol, and 1X Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific, #87786). Samples then underwent mechanical disruption in a Bullet Blender (Next Advance Inc, Averill Park, NY) for 3 min on speed 8 at 4 °C followed by centrifugation at 1400 rcf for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting homogenate for each sample was stored at −80° and a 12 μL aliquot was mixed in a 1:4 dilution with phosphate buffered sodium azide for BCA analysis. 25 μL of each sample or 25 μL of each albumin standard was pipetted in duplicate onto a 96-well plate. Working reagent was added at a volume of 200 μL to each well, and the plate was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min before reading at 562 nm on a Synergy plate reader (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Using the resulting protein concentration, homogenates containing 20 μg of protein were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C.

2.8.1. Western blotting

Western blots were completed using CeA homogenates in the manner previously described (Finnell et al., 2018; Pate et al., 2023). Briefly, each sample was mixed at a 1:6 ratio with a solution of β-mercaptoethanol and 6X sample buffer, heated at 75 °C for 5 min, and then loaded into mini-protean gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Gels were submerged in 1X running buffer solution (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in electrophoresis chambers for 1 h at 135 V. Proteins were then transferred from the gels onto PVDF membranes in 1X transfer buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in transfer chambers for 90 min at 100 V. Membranes were then submerged in blocking buffer at room temperature for 1 h (1:1 ratio of 1X PBS: Fluorescent Blocking Buffer, Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA). After blocking, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C in the following primary antibodies diluted in a solution of blocking buffer with 0.2% Tween-20: mouse anti-GapDH (1:1000, Santa Cruz #sc-365062), rabbit anti-ERβ (1:250, Thermo Fisher #PA1-310B), and rabbit anti-CRF (1:2500, Abcam #ab-184238). The next day, membranes underwent three 10-min washes in 1X TBS with 10% Tween-20 and were incubated in LI-Cor fluorescent secondary antibodies (IR-Dye anti-rabbit 800 nm, LI-Cor #926–32213; IR-Dye anti-mouse 680 nm, LI-Cor #962–68072) diluted 1:20,000 in a solution of blocking buffer with 0.2% Tween-20 and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 1 h. Membranes were washed in TBS with 10% Tween-20 (3 × 10 min), imaged on a LI-Cor Odyssey scanner (LI-Cor Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE), quantified using LI-Cor Image Studios Software, and normalized to GapDH protein levels. Importantly, the GapDH protein levels used for normalization did not differ between treatment groups (Table S1).

2.9. Statistical analysis

The data included in Experiment #1 were analyzed using unpaired t-tests to compare WS and CON rats, while the dose response data included in the supplement were analyzed via One-way ANOVA. All behavioral and molecular statistical analyses for Experiment #2 were performed via Two-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analyses. Behavioral testing that was completed prior to and following stress exposure were additionally analyzed using a Three-way repeated measures ANOVA. Main effects of stress, PHTPP, and stress x PHTPP interactions are provided in the main text results section while post-hoc analyses are indicated by symbols on figures and denoted in figure legends. Outliers were identified and removed if they were more than two standard deviations from the group mean. The datapoints that were identified as outliers are highlighted in the corresponding results section and define the number, treatment, and endpoint from which they were removed. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) with an α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment #1

3.1.1. Witness stress increases acute and protracted anxiety-like behaviors in females

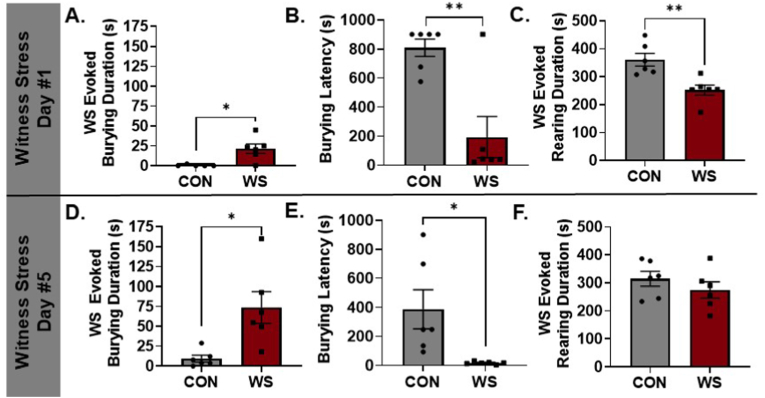

Experiment #1 first confirmed that WS evoked stress-related hypervigilant behaviors similar to our previous findings (Finnell et al., 2018; Pate et al., 2023). WS-exposed rats exhibited a higher duration of spontaneous anxiety-like burying of the cage bedding (Fig. 2A, D1 bury duration: t10 = 2.368, p = 0.0394) and a shorter latency to start burying when compared to CON rats on D1 (Fig. 2B, D1 bury latency: t10 = 4.005, p = 0.0025). This behavior was paralleled by a decrease in exploratory rearing behavior in WS rats on D1 (Fig. 2C, t10 = 3.728, p = 0.0039) with no effect on freezing (WS 0.84 ± 0.805, CON 2.83 ± 1.52, t9 = 1.165, p = 0.2741, data not shown). The hypervigilant burying response continued on D5 with increased burying duration (Fig. 2D, t10 = 3.185, p = 0.0102) and decreased burying latency (Fig. 2E, t10 = 2.737, p = 0.0210) when comparing WS to CON rats. There were no differences observed in rearing (Fig. 2F, t10 = 1.011, p = 0.3357) or freezing duration on D5 (WS 2.8 ± 2.466, CON 3.617 ± 1.837, t10 = 0.2656, p = 0.796, data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Anxiety-like burying is increased while exploratory rearing is reduced in female rats exposed to WS. On D1, rats exhibited a spontaneous stress-evoked burying response during WS (A), a decreased latency to begin burying (B), and a reduction in exploratory rearing behavior (C) as compared to CON rats. These anxiety-like behavioral effects were also evident following repeated WS exposure as measured on D5, with WS rats exhibiting a heightened burying response (D) and decreased burying latency (E). On D5, there were no longer reductions in rearing for WS rats compared to CON (F) (n = 6/group, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005). WS: Witness Stress; D1: Day 1; D5: Day 5; CON: control.

Four days following WS/CON exposure, rats were challenged with a marble burying task. WS rats exclusively exhibited increases in anxiety-like behavior during MB (apparatus depicted in Fig. 3A). Behaviors including burying, freezing, rearing, and marble interaction were quantified from both the pre- and post-stress tests and compared to achieve a final value reflecting the difference in behavior following stress. Females exposed to WS exhibited an increased number of marbles buried (Fig. 3B, t10 = 4.385, p = 0.0014) and duration of burying throughout the 15-min task (Fig. 3D, t10 = 2.363, p = 0.0397) when compared to CON rats. These data were also analyzed with a repeated measures ANOVA which confirmed that there was a significant interaction between stress and session (pre- vs post-stress) for the number of marbles buried (Fig. 3C, F1,10 = 16.76, p = 0.0022), where WS rats demonstrated differences in the number of marbles buried from before to after stress (p = 0.0002), but CON rats did not (p = 0.803). The same effects were observed when analyzed with repeated measures, with a stress x session interaction established for burying duration (Fig. 3E, F1,10 = 5.584, p = 0.0397). Additionally, rats with a history of WS exhibited a trend towards decreased time spent interacting with the marbles (Fig. 3F, t10 = 1.692, p = 0.0608), an exploratory rather than anxiety-like behavior, while CON rats increased their marble interaction. There were no further significant differences revealed by repeated measures analysis (Fig. 3G, F1,10 = 2.862, p = 0.1216). Additional behaviors, including freezing (WS 2.633 ± 2.804, CON 16.33 ± 6.295, t10 = 1.988, p = 0.0749) and rearing (WS 126.9 ± 48.54, CON 36.93 ± 46.33, t10 = 1.34, p = 0.2098), were not different between WS/CON groups (data not shown).

3.1.2. Exposure to stress cues augments anxiety-like behaviors in females with a history of witness stress

The day following MB testing, rats were exposed to their respective WS/CON context (Fig. 3H) for 15 min to mimic the context of the prior week's stress or control conditions. When compared to CON rats, which were handled and returned to their home cage for video recording, rats previously exposed to WS exhibited significantly increased levels of burying (Fig. 3I, t10 = 11.23, p < 0.0001) along with a decreased latency to start burying (Fig. 3J, t10 = 2.996, p = 0.0141) in response to the context in which they previously experienced WS. Further, WS rats exhibited a decrease in rearing behavior (Fig. 3K, t10 = 3.785, p = 0.0036) when compared to CON.

3.1.3. WS context exposure increases ERβ and CRF in the central amygdala

Brain tissue was collected 15 min following the end of WS/CON context exposure and brains were prepared for Western blot analysis using antibodies for ERβ and CRF. The CRF antibody yields a separate band for the CRF precursor pro-CRF (45 kD) and the mature CRF protein (25 kD; Fig. 3L). WS rats exhibited an increase in ERβ (Fig. 3M, t9 = 2.928, p = 0.0168) as well as proCRF (Fig. 3N, t10 = 2.113, p = 0.0304) with a trend towards increased CRF (Fig. 3O, t10 = 1.648, p = 0.0652) in the CeA in response to the WS context.

3.2. Experiment #2

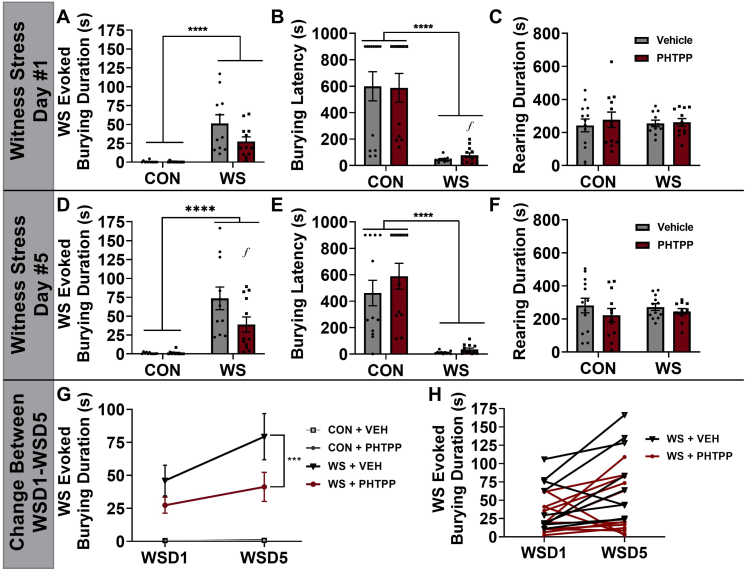

3.2.1. WS-evoked burying is attenuated by Intra-CeA ERβ antagonism during repeated WS exposure

Similar to previous findings in our lab and in accordance with Experiment #1, WS was shown to promote spontaneous stress-evoked burying on D1 (Fig. 4A, main effect of stress: F1,41 = 37.52, p < 0.0001) with a shorter latency to begin burying on D1 (Fig. 4B, main effect of stress: F1,42 = 41.71, p < 0.0001). Additionally, there were no significant main effects observed regarding rearing (Fig. 4C, stress effect, F1,44 = 0.0022, p = 0.9624, drug effect, F1,44 = 0.3217, p = 0.5735) or freezing on D1 (stress effect, F1,46 = 1.957, p = 0.1685, drug effect, F1,46 = 0.07395, p = 0.7869, data not shown). On D5 of WS exposure, stressed females exhibited an increase in burying compared with CON (Fig. 4D, main effect of stress, F1,41 = 36.71, p < 0.0001). Additionally, while PHTPP had no effect on the burying response upon the initial WS exposure (D1 post hoc, WS + VEH vs. WS + PHTPP, p = 0.0514), ERβ blockade significantly reduced WS-evoked burying on D5 following repeated WS exposure (Day #5 post hoc, WS + VEH vs. WS + PHTPP, p = 0.0095). Further, WS rats exhibited a shorter latency to begin burying on D5 (Fig. 4E, main effect of stress: F1,44 = 48.56, p < 0.0001) with no effects on rearing (Fig. 4F, stress effect, F1,44 = 0.0339, p = 0.8548, drug effect, F1,44 = 1.557, p = 0.2187) or freezing (stress effect, F1,44 = 0.1455, p = 0.7052, drug effect, F1,44 = 0.00281, p = 0.958, data not shown). These data were also compared between D1 and D5 to be analyzed with a repeated measures ANOVA. When comparing burying behavior between the groups on D1 and D5 (Fig. 4G), there was a significant time x stress (F1,38 = 7.969, p = 0.0075) and stress x drug interaction (F1,38 = 4.187, p = 0.0477). The data from the two stress groups, WS + VEH and WS + PHTPP, were separated from controls and compared to further analyze the effect of PHTPP on burying between D1 and D5 (Fig. 4H). These repeated measures analyses revealed a significant drug effect (F1,76 = 3.281, p = 0.0016) and significant post hoc comparisons between WS + VEH and WS + PHTPP groups (F1,38 = 4.133, p = 0.0491). The following statistical outliers were removed: burying duration, CON + VEH, n = 1, CON + PHTPP, n = 1, WS + VEH, n = 1; burying latency, WS + VEH, n = 1, WS + PHTPP, n = 1; rearing duration, WS + PHTPP, n = 1.

Fig. 4.

Blocking ERβ in the CeA reduces the sensitization to increased spontaneous WS-evoked burying during repeated WS exposure. Spontaneous burying behavior was increased among WS rats compared to CON during day #1 (D1) exposure to WS/CON, and this acute response was unaffected by pre-treatment with the ERβ antagonist PHTPP (A). Burying also presented significantly quicker in WS rats with a longer latency to begin burying observed in the WS rats treated with PHTPP (B). There were no group differences observed in rearing behavior (C). However, on the fifth day of WS exposure, PHTPP attenuates the WS-evoked burying response (D), along with an overall stress effect on latency to begin burying (E) and no significant differences between the groups with regards to rearing behavior (F). When directly comparing the burying behavior between D1 and D5, there was a interaction between treatment and time, with WS + VEH rats increasing burying from D1 to D5 which this behavioral response was prevented with PHTPP treatment (G, H) (n = 12–13/group with the exception of statistical outliers, ʄp < 0.05 WS + VEH vs. WS + PHTPP, *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001). ERβ: estrogen receptor beta; CeA: central amygdala; WS: witness stress; D1: day 1; CON: control.

3.2.2. WS and PHTPP differentially regulate behavioral outcomes

Following WS/CON, rats were tested on a variety of behavioral paradigms to determine the impact of WS ± intra-CeA ERβ antagonism on the behavioral adaptations that occur in response to repeated stress. A generalized change in anxiety-like behavior was assessed with the EPM. A history of repeated WS exposure did not alter the percentage of time spent in the open arms (Fig. 5A; main effect of stress: F1,36 = 2.523, p = 0.121) or the total distance traveled (Fig. 5B, stress effect, F1,35 = 0.04819, p = 0.8275, drug effect, F1,35 = 0.2297, p = 0.6347). Additionally, the percentage of time spent in the closed arms or center zone was not affected by stress (closed arms: F1,35 = 1.228, p = 0.2753; center: F1,35 = 1.087, p = 0.3044) nor PHTPP (closed arms: F1,35 = 0.3156, p = 0.5778; center: F1,35 = 0.4888, p = 0.4891, data not shown).

Fig. 5.

A history of WS and ERβ antagonism in the CeA differentially affect hypervigilant, anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors. There were no significant effects of WS on behavior in the EPM, with no differences in the percentage of time spent in the open arms or (A) in general motor behaviors as evidenced by overall distance traveled (B). Further, behavior on the EPM was not regulated by pharmacological blockade of ERβ during WS exposure, as evidenced by a lack of effect induced by PHTPP. Repeated WS produced a persistent increases in anxiety-like behavior evidenced by the hypervigilant phenotype indicated by an enhanced acoustic startle response. Startle velocity was increased in WS rats and blocking ERβ with PHTPP during each WS session prevented the development of heightened ASR following stress (C). Further, a history of repeated WS exposure resulted in a significant decrease in the percent of sucrose preferred in the post-stress test but this reduction in reward seeking/depressive-like behaviors was prevented by PHTPP (D). Behaviors were not altered in the single post-stress marble burying task, with no group differences in the number of marbles buried (E) or the duration of burying (F). Brains were collected under resting conditions 48 h after the final behavioral task and CeA tissue was prepared for Western blot analysis. PHTPP caused a a significant long-term reduction in resting levels of CRF (G) with no effects on resting levels of proCRF (H). There was also a compensatory increase in ERβ at rest in both control and WS rats (I) that were treated with PHTPP. (n = 12–13/group with the exception of statistical outliers, + main effect of drug, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.0005, ****p < 0.0001). WS: witness stress; ERβ: estrogen receptor beta; CeA: central amygdala; EPM: elevated plus maze; ASR: acoustic startle response; MB: marble burying; CRF: corticotropin releasing factor.

When the innate startle response was tested using ASR, a history of repeated WS exposure resulted in an enhanced startle amplitude at 105 dB, and this exaggerated startle response was diminished in WS rats that were treated with PHTPP (Fig. 5C; stress x drug interaction: F1,40 = 9.237, p = 0.0042). Specifically, there was a significant increase in startle amplitude in the WS rats which was blunted by PHTPP treatment during WS (WS + VEH vs. WS + PHTPP, p = 0.0242). Using a Three-way repeated measures ANOVA, it was determined that there was a significant trend towards an interaction between time, stress, and drug treatment (F1,40 = 4.002, p = 0.0523, data not shown). The following statistical outliers were removed from analysis: CON + VEH, n = 1, CON + PHTPP, n = 1, WS + VEH, n = 1, WS + PHTPP, n = 1.

In the subsequent testing to assess reward seeking behaviors, sucrose preference was reduced following WS which was prevented with PHTPP treatment during WS exposure (Fig. 5D, WS + VEH vs. WS + PHTPP, p = 0.0465). Further, a three-way repeated measures ANOVA on the sucrose preference values before and after stress also revealed significant time x stress (F1,30 = 4.505, p = 0.0422), time x drug (F1,30 = 5.863, p = 0.0217), and stress x drug (F1,30 = 4.637, p = 0.0395) interactions with significant post-hoc comparisons between pre-versus post-stress SPT for WS + VEH (F1,30 = 3.102, p = 0.0042) and significant post-stress differences between CON + VEH vs. WS + VEH (F1,60 = 2.706, p = 0.0089) and WS + VEH vs. WS + PHTPP (F1,60 = 3.016, p = 0.0038, data not shown).

Finally, rats in Experiment #2 were exposed to a single post-stress session of marble burying. Due to the fact that comparisons were not able to be made between a pre- and post-stress task, these results vary from those we determined for Experiment #1. There was no effect of stress or drug treatment on the number of marbles buried (Fig. 5E, stress effect, F1,32 = 0.1475, p = 0.7035, drug effect, F1,32 = 2.448, p = 0.1275). When analyzing the amount of time spent burying throughout this task, there was a significant drug effect (F1,31 = 5.149, p = 0.0304) with a trend towards differences between WS + VEH- and WS + PHTPP-treated rats (Fig. 5F, p = 0.0615). There were no effects of stress or drug on additional behaviors recorded during this task including marble interaction (stress effect: F1,31 = 0.0868, p = 0.7703; drug effect: F1,31 = 2.039, p = 0.1633, data not shown). It is important to emphasize that these data represent behaviors from a single post-stress task, rather than a within-subjects change from pre-stress baseline which may contribute to the difference from the robust results seen in the pre-to post-stress comparisons in Experiment #1. The following statistical outliers were removed from analysis: marbles buried, WS + PHTPP, n = 1; burying duration, CON + PHTPP, n = 1, marble interaction, CON + PHTPP, n = 1, WS + PHTPP, n = 1.

3.2.3. PHTPP induces long-term alterations in CeA CRF and ERβ

Tissue from Experiment #2 was collected under resting conditions two days following the final behavioral assay. Brain samples were analyzed using Western blot to determine protein expression of ERβ and CRF. There was a significant drug effect of previous PHTPP treatment on long-term resting ERβ protein expression in the CeA (Fig. 5G, F1,39 = 10.11, p = 0.0029) with PHTPP-treated rats exhibiting higher levels of ERβ when compared to vehicle, independent of stress history. Additionally, PHTPP treatment led to decreases in CRF protein expression in the CeA for both WS and CON groups (Fig. 5I, main effect of drug, F1,39 = 18.76, p < 0.0001) with no significant change in proCRF (Fig. 5H, stress x drug interaction, F1,49 = 0.8941, p = 0.349). Full western blot images are provided in the Supplement (Figs. S2A and S2B).

4. Discussion

These studies show for the first time that ERβ signaling in the CeA increases sensitivity to social stress in females and further strengthens the hypothesis that estrogen plays a dichotomous role in regulating behavior in the context of stress. Overall, these data demonstrate that WS increases hypervigilant and negative valence behaviors that were accompanied by increases in intra-CeA ERβ and CRF protein expression. Importantly, these studies went on to prove that stress-evoked negative valence was regulated by intra-CeA ERβ, as pharmacological blockade of ERβ in the CeA prevented these effects. These studies build on previous work investigating the role of estrogen signaling on stress-related outcomes in females and highlight a novel target for the treatment of stress-induced neuropsychiatric disorders. The increased prevalence of such stress-related conditions among women in their reproductive years is well documented (Barth et al., 2015; Bezerra et al., 2021) and, while we cannot rule out contributing roles of other ovarian hormones such as progesterone, accumulating evidence from both clinical (Hlavacova et al., 2008; Newhouse et al., 2010) and preclinical (Figueiredo et al., 2007; Flores et al., 2020; Hokenson et al., 2021; Kokane and Perrotti, 2020; Shansky et al., 2004) studies demonstrate that, in the context of stress, estrogen signaling in the brain plays a critical role in this heightened susceptibility.

Estrogen is known to directly increase the expression of CRF mRNA and heighten behavioral responses to stressful stimuli (Jasnow et al., 2006). Importantly, the CRF gene contains an estrogen response element which allows nuclear estrogen receptor activation to modulate CRF transcription (Ni and Nicholson, 2006; Vamvakopoulos and Chrousos, 1993). Using the same WS model as utilized for these studies, we previously reported a stress-evoked increase in CeA CRF among intact but not ovariectomized female rats (Finnell et al., 2018). Furthermore, this sensitized CRF response was accompanied by increased hypervigilant behavioral responses in natural cycling, but not ovariectomized, females. While this evidence highlights the contribution of estrogen-mediated effects on CRF in the increased stress susceptibility observed in females, there is a pressing need to determine the specific neural mechanisms underlying this phenomenon. It is reasonable, then, to consider estrogen signaling through ERβ within the CeA resulting in increased CRF expression as a promising mechanism by which estrogen facilitates this enhanced stress response among females. Our findings support this hypothesis as the first to identify a regulatory role for intra-CeA ERβ in the development of negative valence and hypervigilant phenotypes that emerge among naturally cycling females as a consequence of repeated social stress exposure.

While Experiment #1 determined that exposure to the WS CXT increased both pro-CRF and CRF in rats with a history of WS, Experiment #2 showed that under resting conditions at this protracted timeline, WS rats did not demonstrate changes in CRF. However, PHTPP treated rats exhibited decreased levels of CRF regardless of stress history. These data suggest that exposure to stress-related cues induces de-novo production of CRF from its precursor, while, in the long term, a history of ERβ blockade prevents the accumulation of CRF. Together, these results suggest that beyond the expected stress evoked increase in CRF production signaling in the CeA, baseline levels of CRF in the CeA may be maintained by ERβ signaling. Further, given the robust impact that ERβ blockade had on CeA CRF levels, it is important to consider the impact of this pharmacological manipulation on CeA-CRF projection regions that are known to directly regulate these behaviors. Importantly, CRF-projecting neurons from the CeA are a major source of stress-induced activation of the noradrenergic LC (Curtis et al., 1997, 2002), which is responsible for initiating the hypervigilant burying behavior assessed in our studies (Howard et al., 2008). In fact, stress- or CRF-evoked hypervigilant burying is dependent upon intact LC-norepinephrine (NE) signaling. Therefore, decreased stress-induced CRF expression achieved in the PHTPP-treated rats is likely to reduce LC-NE activity and could explain their blunted WS-evoked burying response (Finnell et al., 2018). Unfortunately, the protracted time point of euthanasia in these experiments does not allow for the analysis of this hypothesis within our current dataset. Future studies exploring this avenue will include dynamic methods of analysis, like in vivo electrophysiology, to better understand the impact of CeA ERβ antagonism on LC-NE signaling and behavior.

These studies determined that estrogen signaling through ERβ plays a role in the behavioral sensitization to stress that occurs during repeating exposure to social stressors. Specifically, PHTPP did not induce a significant effect on the burying response during stress on the initial stress exposure, but significantly decreased this behavior on the final day of stress. It is also important to note that while intra-CeA ERβ appears to mediate many stress-induced behaviors, EPM was unaffected by stress and intra-CeA PHTPP treatment. As such, it is important to highlight the sex differences in anxiety-like behaviors that have been observed when utilizing traditional models of measuring anxiety-like behaviors. It has recently been established that adult female rats do not exhibit anxiety-like phenotypes on the EPM when compared to males (Börchers et al., 2022), and this may underlie the lack of stress-induced alterations observed in these studies. Further, there is major involvement of other brain regions in the regulation of EPM-specific behaviors, including the medial amygdala (Troakes and Ingram, 2009) and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Butler et al., 2016; Callahan et al., 2013) and, thus, sole modulation of ERβ in the CeA would be insufficient to alter these behaviors. Further, while the focus of these experiments was on the alterations in ERβ in stressed females, there are sex differences in ERβ expression within the amygdala that may lead to sex differences if these experiments were replicated in males. Females exhibit higher levels of ERβ receptor expression within the amygdala when compared to males (Milner et al., 2010; Weiser et al., 2008; Zuloaga et al., 2014) which may lead to increased CRF release in response to stress. Further experiments directly comparing ERβ and CRF expression followings stress between males and females would be required to determine the presence of sex differences.

An additional unexpected finding was that, in the long-term, treatment with PHTPP for five consecutive days resulted in a compensatory increase in ERβ expression within the CeA regardless of stress exposure. While PHTPP is established as a potent and selective antagonist of ERβ (Compton et al., 2004), there is a lack of research examining neuronal adaptations that occur in response to repeated pharmacological blockade of ERβ. Importantly, these are the first results to show that five days of intra-CeA PHTPP administration leads to compensatory increases in receptor expression. While the timescale of ERβ alterations following chronic PHTPP treatment are unclear, one major limitation comes from the fact that there may be increased ERβ during the behavioral testing post-stress. Despite this compensatory increase, ERβ antagonism during stress exposure was still effective at preventing the stress-induced behavioral alterations previously observed. Additionally, PHTPP treatment did not alter any behaviors when administered to controls, demonstrating that an upregulation of ERβ within the CeA alone is not sufficient to facilitate changes in these behavioral tasks. Further, regardless of our data indicating that drug spread should be confined to the CeA, we cannot definitively rule out the possibility that PHTPP may have spread to the other amygdala regions that are in close proximity to the CeA including the lateral and basolateral subregions. However, these findings support the hypothesis that estrogen signaling via ERβ within the CeA during stress exposure is critical for the hypervigilant and anhedonic behavioral responses observed following repeated stress. In parallel, we established that exposure to the WS context in rats with a history of WS increases CRF in the CeA while we show for the first time that ERβ signaling serves to regulate long lasting resting/basal CRF expression levels at 6 days following treatment. Although there is a lack of a stress effect in resting CRF levels at the protracted timeline in Experiment #2, stress-cue evoked CRF levels were heightened, indicating that prior WS exposure sensitizes stress-evoked CRF.

Overall, these experiments have established that WS exposure increases intra-CeA CRF expression and promotes the development of negative valence and hypervigilant behaviors across multiple behavioral paradigms. Further, despite the compensatory elevation in CeA ERβ, local PHTPP treatment during WS exposure was effective in attenuating the stress-induced neuronal and behavioral alterations identified in these experiments. These data highlight the critical role for CeA ERβ signaling during stress exposure since, regardless of resting ERβ levels following stress, blocking ERβ with PHTPP during WS prevents the development of hypervigilant behaviors. Future studies examining the downstream neural correlates involved in these behavioral responses and impacted by ERβ signaling, including the LC-NE system, will further establish these pathways as viable targets for the treatment and prevention of stress-induced neuropsychiatric disorders in females.

5. Conclusions

These experiments are the first to demonstrate that repeated exposure to witness stress results in an increase of ERβ and CRF expression within the CeA and, further, that pharmacological blockade of intra-CeA ERβ during each stress exposure prevents the emergence of behavioral deficits indicative of negative valence phenotypes as measured by marble burying, acoustic startle, and sucrose preference.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 MH113892) and Veterans Health Administration (I21 BX002664 and BX001374).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cora E. Smiley: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Brittany S. Pate: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing – review & editing. Samantha J. Bouknight: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Megan J. Francis: Investigation. Alexandria V. Nowicki: Investigation. Evelynn N. Harrington: Investigation. Susan K. Wood: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Declarations of competing interest

None.

Handling Editor: John Cryan

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2023.100531.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Babb J.A., Masini C.V., Day H.E.W., Campeau S. Sex differences in activated corticotropin-releasing factor neurons within stress-related neurocircuitry and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis hormones following restraint in rats. Neuroscience. 2013;234:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth C., Villringer A., Sacher J. Sex hormones affect neurotransmitters and shape the adult female brain during hormonal transition periods. Front. Neurosci. 2015;9 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra H.S., Alves R.M., Nunes A.D.D., Barbosa I.R. Prevalence and associated factors of common mental disorders in women: a systematic review. Publ. Health Rev. 2021;42 doi: 10.3389/phrs.2021.1604234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börchers S., Krieger J.-P., Asker M., Maric I., Skibicka K.P. Commonly-used rodent tests of anxiety-like behavior lack predictive validity for human sex differences. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2022;141 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler R., Oliver E., Sharko A., Parilla-Carrero J., Kf K., JR F., Ma W. Activation of corticotropin releasing factor-containing neurons in the rat central amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis following exposure to two different anxiogenic stressors. Behav. Brain Res. 2016;304 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan L., Tschetter K., Ronan P. Inhibition of corticotropin releasing factor expression in the central nucleus of the amygdala attenuates stress-induced behavioral and endocrine responses. Front. Neurosci. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton D.R., Sheng S., Carlson K.E., Rebacz N.A., Lee I.Y., Katzenellenbogen B.S., Katzenellenbogen J.A. Pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines: estrogen receptor ligands possessing estrogen receptor beta antagonist activity. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47(24):5872–5893. doi: 10.1021/jm049631k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis A., Bello N., Connolly K., Valentino R. Corticotropin-releasing factor neurones of the central nucleus of the amygdala mediate locus coeruleus activation by cardiovascular stress. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14(8) doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis A., Lechner S., Pavcovich L., Valentino R. Activation of the locus coeruleus noradrenergic system by intracoerulear microinfusion of corticotropin-releasing factor: effects on discharge rate, cortical norepinephrine levels and cortical electroencephalographic activity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 1997;281(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9103494 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit P., Sahu R., Mishra D. Marble-burying behavior test as a murine model of compulsive-like behavior. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2020;102 doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2020.106676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo H.F., Ulrich-Lai Y.M., Choi D.C., Herman J.P. Estrogen potentiates adrenocortical responses to stress in female rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;292(4):E1173–E1182. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00102.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnell, Muniz B.L., Padi A.R., Lombard C.M., Moffitt C.M., Wood C.S.…Wood S.K. Essential role of ovarian hormones in susceptibility to the consequences of witnessing social defeat in female rats. Biol. Psychiatr. 2018;84(5):372–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores R., Cruz B., Uribe K., Correa V., Arreguin M., Carcoba L.…O'Dell L. Estradiol promotes and progesterone reduces anxiety-like behavior produced by nicotine withdrawal in female rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa R.J., Burgess L.H., Kerr J.E., O'Keefe J.A. Gonadal steroid hormone receptors and sex differences in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal Axis. Horm. Behav. 1994;28(4):464–476. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck A.L., Handa R.J. Sex differences in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis' response to stress: an important role for gonadal hormones. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(1):45–58. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herringa R.J., Nanda S.A., Hsu D.T., Roseboom P.H., Kalin N.H. The effects of acute stress on the regulation of central and basolateral amygdala CRF-binding protein gene expression. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;131(1–2):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavacova N., Wawruch M., Tisonova J., Jezova D. Neuroendocrine activation during combined mental and physical stress in women depends on trait anxiety and the phase of the menstrual cycle. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1148 doi: 10.1196/annals.1410.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hokenson R.E., Short A.K., Chen Y., Pham A.L., Adams E.T., Bolton J.L.…Baram T.Z. Unexpected role of physiological estrogen in acute stress-induced memory deficits. J. Neurosci. : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2021;41(4):648–662. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.2146-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard O., Carr G., Hill T., Valentino R., Lucki I. Differential blockade of CRF-evoked behaviors by depletion of norepinephrine and serotonin in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199(4) doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1179-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasnow A.M., Schulkin J., Pfaff D.W. Estrogen facilitates fear conditioning and increases corticotropin-releasing hormone mRNA expression in the central amygdala in female mice. Horm. Behav. 2006;49(2):197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin N.H., Shelton S.E., Davidson R.J. The role of the central nucleus of the amygdala in mediating fear and anxiety in the primate. J. Neurosci. : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24(24):5506–5515. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0292-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose M., Jacobi F. Can gender differences in the prevalence of mental disorders be explained by sociodemographic factors? Arch Womens Ment Health. 2004;7(2):133–148. doi: 10.1007/s00737-004-0047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M., Schnitzler H.U. The acoustic startle response in rats--circuits mediating evocation, inhibition and potentiation. Behav. Brain Res. 1997;89(1–2):35–49. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)02296-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokane S., Perrotti L. Sex differences and the role of estradiol in mesolimbic reward circuits and vulnerability to cocaine and opiate addiction. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2020;14 doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2020.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraeuter A., Guest P., Sarnyai Z. The elevated plus maze test for measuring anxiety-like behavior in rodents. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;1916 doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8994-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Moëne O., Stavarache M., Ogawa S., S M., Ågmo A. Estrogen receptors α and β in the central amygdala and the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus: sociosexual behaviors, fear and arousal in female rats during emotionally challenging events. Behav. Brain Res. 2019;367 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K.C., Melia K.R., Campeau S., Falls W.A., Miserendino M.J., Davis M. Lesions of the central nucleus of the amygdala, but not the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, block the excitatory effects of corticotropin-releasing factor on the acoustic startle reflex. J. Neurosci. : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1992;12(6):2313–2320. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.12-06-02313.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund T.D., Hinds L.R., Handa R.J. The androgen 5alpha-dihydrotestosterone and its metabolite 5alpha-androstan-3beta, 17beta-diol inhibit the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal response to stress by acting through estrogen receptor beta-expressing neurons in the hypothalamus. J. Neurosci. : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26(5):1448–1456. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.3777-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund T.D., Rovis T., Chung W.C.J., Handa R.J. Novel actions of estrogen receptor-β on anxiety-related behaviors. Endocrinology. 2005;146(2):797–807. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch J.F., Dejanovic D., Winiecki P., Mulvany J., Ortiz S., Riccio D.C., Jasnow A.M. Activation of ERβ modulates fear generalization through an effect on memory retrieval. Horm. Behav. 2014;66(2):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner T.A., Thompson L.I., Wang G., Kievits J.A., Martin E., Zhou P.…Waters E.M. Distribution of estrogen receptor β containing cells in the brains of bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice. Brain Res. 2010;1351:74–96. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M.A., Pfaff D.W. Effects of estrogen on activity and fear-related behaviors in mice. Horm. Behav. 2001;40(4):472–482. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M.A., Schulkin J., Pfaff D.W. Estrogens and non-reproductive behaviors related to activity and fear. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2004;28(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse P.A., Dumas J., Wilkins H., Coderre E., Sites C.K., Naylor M.…Young S.N. Estrogen treatment impairs cognitive performance after psychosocial stress and monoamine depletion in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(4):860–873. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181e15df4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni X., Nicholson R. Steroid hormone mediated regulation of corticotropin-releasing hormone gene expression. Front. Biosci. : J. Vis. Literacy. 2006;11 doi: 10.2741/2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund M., Kuiper G., Gustafsson J., Hurd Y. Differential distribution and regulation of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNA within the female rat brain. Brain research. Molecular brain research. 1998;54(1) doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00351-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate B.S., Bouknight S.J., Harrington E.N., Mott S.E., Augenblick L.M., Smiley C.E.…Wood S.K. Site-specific knockdown of microglia in the locus coeruleus regulates hypervigilant responses to social stress in female rats. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2023.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pêgo J.M., Sousa J.C., Almeida O.F.X., Sousa N. In: Behavioral Neurobiology of Anxiety and its Treatment. Stein M.B., Steckler T., editors. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2010. Stress and the neuroendocrinology of anxiety disorders; pp. 97–118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poli E., Angrilli A. Greater general startle reflex is associated with greater anxiety levels: a correlational study on 111 young women. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015;9:10. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomrenze M.B., Tovar-Diaz J., Blasio A., Maiya R., Giovanetti S.M., Lei K.…Messing R.O. A corticotropin releasing factor network in the extended amygdala for anxiety. J. Neurosci. : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2019;39(6):1030–1043. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2143-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandanger I., Nygård J., Sørensen T., Moum T. Is women's mental health more susceptible than men's to the influence of surrounding stress? Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2004;39(3) doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shansky R.M., Glavis-Bloom C., Lerman D., McRae P., Benson C., Miller K.…Arnsten A.F. Estrogen mediates sex differences in stress-induced prefrontal cortex dysfunction. Mol. Psychiatr. 2004;9(5):531–538. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue P., Merchenthaler I. Distribution of estrogen receptor beta immunoreactivity in the rat central nervous system. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;436(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11413547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel Z., Marnane C., Iranpour C., Chey T., Jackson J.W., Patel V., Silove D. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476–493. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troakes C., Ingram C.D. Anxiety behaviour of the male rat on the elevated plus maze: associated regional increase in c-fos mRNA expression and modulation by early maternal separation. Stress. 2009;12(4):362–369. doi: 10.1080/10253890802506391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino R.J., Van Bockstaele E. Convergent regulation of locus coeruleus activity as an adaptive response to stress. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;583(2–3):194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vamvakopoulos N.C., Chrousos G.P. Evidence of direct estrogenic regulation of human corticotropin-releasing hormone gene expression. Potential implications for the sexual dimophism of the stress response and immune/inflammatory reaction. J. Clin. Investig. 1993;92(4):1896–1902. doi: 10.1172/JCI116782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viau V., Bingham B., Davis J., Lee P., Wong M. Gender and puberty interact on the stress-induced activation of parvocellular neurosecretory neurons and corticotropin-releasing hormone messenger ribonucleic acid expression in the rat. Endocrinology. 2005;146(1):137–146. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weera M.M., Shackett R.S., Kramer H.M., Middleton J.W., Gilpin N.W. Central amygdala projections to lateral hypothalamus mediate avoidance behavior in rats. J. Neurosci. : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2021;41(1):61–72. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0236-20.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser M.J., Foradori C.D., Handa R.J. Estrogen receptor beta in the brain: from form to function. Brain Res. Rev. 2008;57(2):309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuloaga D.G., Heck A.L., De Guzman R.M., Handa R.J. Roles for androgens in mediating the sex differences of neuroendocrine and behavioral stress responses. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020;11(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00319-2. 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuloaga D.G., Zuloaga K.L., Hinds L.R., Carbone D.L., Handa R.J. Estrogen receptor β expression in the mouse forebrain: age and sex differences. J. Comp. Neurol. 2014;522(2):358–371. doi: 10.1002/cne.23400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.