Graphical abstract

Keywords: Peanut protein isolate, High methoxyl pectin, Ultrasound, Emulsion, Droplet breakup model

Highlights

-

•

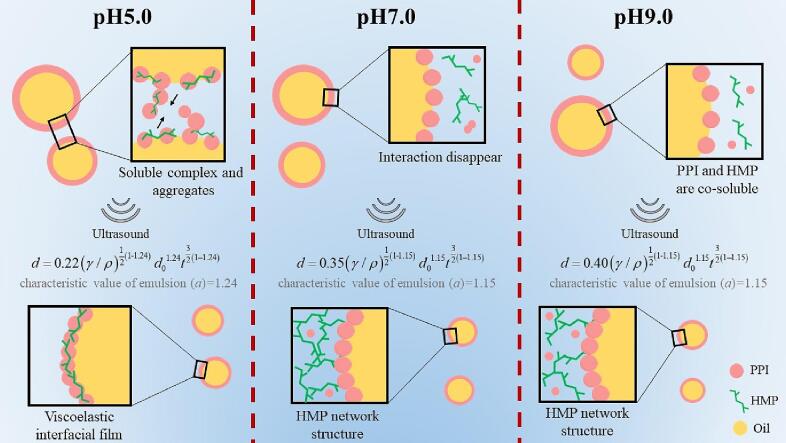

The occurrence state of PPI-HMP was different at pH 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0.

-

•

Droplet breakup model under ultrasound was employed to analyse emulsion properties.

-

•

Characteristics of emulsions stabilised by PPI-HMP at pH 7.0 and 9.0 differed from that at pH 5.0.

-

•

Formation mechanisms of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsion under ultrasound were different.

Abstract

The effect of pH on the occurrence states of peanut protein isolate (PPI) and high methoxyl pectin (HMP), and droplet breakup model of the emulsions under ultrasound were studied. Particle size distribution and scanning electron microscopy results showed that PPI-HMP existed a soluble complex at pH 5.0, had no interaction at pH 7.0, and was co-soluble at pH 9.0. Droplet breakup model results revealed that the characteristics of emulsion stabilised by PPI-HMP treated at pH 5.0 was different from that at pH 7.0 and 9.0. The average diameter of the droplet well satisfied the model. According to rheological properties, interface tension, and microstructure, the formation mechanism and characteristics of emulsion stabilised by PPI-HMP treated at pH 5.0 was different from that at pH 7.0 and pH 9.0. The research provided a reference for constructing emulsions using pH-shifted PPI-HMP under ultrasound.

1. Introduction

Emulsions are commonly used in the food processing industry, since they not only provide a special taste to food but can also be used to deliver and encapsulate biologically active ingredients [1]. To meet the growing demand of healthy products for vegan consumers, many recent studies have focused on the use of natural plant proteins, including soybean [2], pea [3], peanut [4], perilla [5], and others, to construct emulsions. Peanut protein isolate (PPI), extracted from the defatted peanut meal, is a highly digestible natural nutrient resource, which is especially rich in essential amino acids [6]. However, during commercial production, globulin in peanut protein is highly susceptible to denaturation, due to which PPI cannot adsorb quickly enough onto the oil–water interface to form a stable emulsion [7]. Some previous studies demonstrated that combining plant proteins with polysaccharides could be an effective approach to improve their solubility and interfacial adsorption capacity [8], [9]. High methoxyl pectin (HMP) is an economical and easily available plant polysaccharide that can be extracted from fruits, such as apples and citrus fruits. As a food thickener, gelling agent, and texture improver, HMP can enhance viscosity of the continuous phase and prevent the formation of an emulsified layer [10]. Therefore, polysaccharides were added to construct a stable emulsion of PPI.

Protein-polysaccharide complexes can be constructed either covalently [11] or non-covalently [12]. Owing to low energy consumption and simple operation, the use of non-covalent PPI-polysaccharide complexes to construct stable emulsions has emerged as a notable method in the past few years [13], [14]. Due to non-covalent interactions, proteins and polysaccharides may exist in the system as insoluble complexes, soluble complexes, and co-soluble complexes, in a pH-dependent manner [15]. Griffin et al. [16] pointed out that protein and polysaccharide could form soluble complex at low pH (acid environment), and the soluble complex could inhibit coalescence of oil droplets. Meanwhile, biopolymers repelled each other in the emulsion and existed independently due to the extremely strong electrostatic repulsion at high pH (alkaline environments). The various states of occurrence of the two biopolymers exhibit different behaviours during emulsion construction, thereby affecting the flocculation rate of oil droplets and resulting in different emulsion properties [17].

As a clean and efficient energy source, ultrasound plays an important role in emulsification, homogenisation, and encapsulation [18]. Costa et al. [19] reported that the ultrasonic emulsification process could significantly reduce the droplet diameter of an emulsion, thereby favouring the interaction between droplets, eventually increasing the apparent viscosity and prolonging the shelf life of the emulsion. Moreover, the process of droplet breakup under ultrasound provides important information about the characteristics of emulsions. Some studies have attempted to build an appropriate model to predict the droplet size of various emulsions and correlate the same with emulsion stability. Lefebvre et al. [20] predicted the diameter and polydispersity index of a low-energy self-emulsification system, composed of the surfactant (Kolliphor® HS 15) and a cosurfactant (Span® 80), using mixing experiments. Siva et al. [21] used mathematical analysis to obtain a model that could predict the average size of cellulose nanocrystals-based emulsion droplets under ultrasound treatment. Further, the model parameters (characteristic value of an emulsion system and overall droplet breakage parameter) could reflect the emulsion properties to some extent. However, such studies have mainly focused on small molecule emulsifiers such as Span 80, Tween 80, and cellulose nanocrystals; there has been no report on the prediction of the dynamic breakup process in biomacromolecule emulsion droplets under ultrasound. Consequently, investigating the breakup model of natural macromolecule emulsion droplets would provide a new method for exploring the characteristics of emulsions under ultrasound. Further, ultrasound treatment can affect the behaviour of proteins and polysaccharides in emulsion systems [22], [23] and alter the protein-polysaccharide interactions [24], which further suggested that PPI-HMP existing in different states lead to different model parameters.

In the present study, the occurrence states of PPI-HMP under different pH conditions were determined first. Thereafter, a droplet breakup models of the emulsion droplets under various ultrasound treatment conditions was constructed. Finally, rheological properties, surface tension, and microstructure of the emulsion were explored to clarify its characteristics. Thus, the present study aimed to build a droplet breakup model and comprehensively analyse the formation mechanism of pH-shifted PPI-HMP based emulsion under ultrasound from a relatively new perspective.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Defatted peanut flour (51.23% protein content) was obtained from Changshou Co. Ltd. (Shandong Province, Qingdao, China), and HMP (galacturonic acid content ≥ 74.0%, degree of esterification 55%–65%, CAS number: 9000–69-5) was obtained from Macklin Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Soybean oil was purchased from a local supermarket (Zhengzhou, Henan Province, China). Nile red, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), and calcofluor white were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other reagents used were of analytical grade and were ordered from Tianjin Tianli Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China).

2.2. Preparation of PPI

PPI was prepared according to the method described by Feng et al. [25], with some modifications. Defatted peanut flour was mixed with double-distilled water in a ratio of 1:10 (w:v), and the pH of the mixture was adjusted to 9.0 with 1 M NaOH. The dispersion was slowly stirred using an R30 electric stirrer (FLUKO Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 150 rpm for 2 h to ensure sufficient dissolution. The mixture was centrifuged at 4000×g for 15 min, and the supernatant was collected. pH of the supernatant was adjusted to 4.5 with 1 M HCl, allowed to stand for 1 h, and then centrifuged at 4000×g for 15 min. The precipitate was then washed twice with double-distilled water. The clean precipitate was subsequently mixed with double-distilled water and pre-frozen at − 20 °C overnight, followed by freeze-drying. All operations were performed at room temperature (25 °C) unless noted otherwise. The protein content of PPI was 82.70%, as measured using the Kjeldahl method. The ash, moisture, and fat content were 0.92%, 1.89%, and 1.31%, respectively.

2.3. Preparation and particle size distribution measurement of PPI-HMP mixtures

PPI (2.0 g) and HMP (0.25 g) were dispersed in 50 mL double-distilled water, resulting in their respective contents being 4.0% and 0.5% (w/v). After stirring for 12 h, the pH of mixtures was adjusted to pH 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0 and 9.0 respectively. The mixtures were hydrated for another 2 h. Sodium azide (0.02%, w/v) was added to the dispersion to inhibit the growth of microorganisms.

Particle size (z-average diameter) distribution of the PPI-HMP mixtures was measured according to the method of Lv et al. [26], with minor modifications. The diameter distribution of PPI-HMP mixtures at different pH was determined using a BeNano 90 Zeta nanoparticle size and zeta potential analyser (Dandong Bettersize Co., Ltd. Dandong, Liaoning Province, China.). To prevent multiple scattering effects, all samples were diluted 100-fold with double-distilled water. Refractive indices of the samples and the dispersant (water) were set to 1.590 and 1.330, respectively. All samples were prepared at 25 °C and equilibrated for 60 s before each test.

2.4. Scanning electron microscopy

Freeze-dried powder of PPI-HMP mixture was placed on one surface of a conductive double-sided adhesive tape, and coated with gold. A Quanta 250 FEG scanning electron microscope (FEI Co. Ltd. Hillsboro, OR, USA) (SEM) scanned, at an accelerating voltage of 3.0 kV, to capture the microstructure images.

2.5. Preparation of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions

Soy bean oil (12 mL) was added to the PPI-HMP dispersion (described in section 2.3, 48 mL). A high-speed shear homogeniser machine was used to produce coarse emulsions at 13,000 rpm for 1 min (FM 200, FLUKO Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). According to our previous research, using a JY92-IIDN ultrasound generator homogeniser (Scientz Biotechnology Inc., Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China) with a 6-mm diameter titanium probe, to further homogenise the coarse emulsion, samples were subjected to ultrasonic waves with a power density of 6.0 W/cm3 for 4, 8, and 10 min, with both on and off time set at 2 s. The operation temperature was maintained at 20 °C using a circulation tank (DC-2006, Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China) with condensate.

2.6. Establishment of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions droplet breakup model

To gain insight into the PPI-HMP stabilised emulsion droplet degradation process under ultrasound, a narrow range of ultrasound time (0–360 s) and power density (3.0–7.5 W/cm3) was adopted to treat emulsions, followed by the measurement of droplet diameter. Particle size (z-average diameter) of the PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions was determined according to the method described in section 2.3.

Fitting of the emulsion droplet degradation model was based on the three equations described by Siva et al. [21]. Eq. (1) shows the relationship between the initial droplet size (shear homogenisation only) and the ultrasound-treated droplet diameter.

| (1) |

where d and d0 represent the average droplet diameter of the emulsion homogenised by ultrasound and the initial droplet size, respectively (nm), γ is the ultrasound power density (W/cm3), and t is the ultrasound time (s).

The mean droplet diameter from Eq. (1) was used for linear fitting to obtain the slopes and intercepts of the different emulsion systems; ɑ represents the characteristic value of the emulsion, and b was substituted into Eq. (2) to obtain φ, which is the overall droplet-breakage parameter.

| (2) |

Once the required parameters were calculated, Eq. (3) was used to predict the size of the emulsion droplets under different ultrasound homogenisation conditions:

| (3) |

where ρ is the density of emulsion (g/cm3).

2.7. Properties of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions

2.7.1. Rheological properties

Apparent viscosity, storage modulus (G′), and loss modulus (G′′) of the PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions were characterised using a Discover HR 10 rheometer (TA Instruments Co., Ltd., Newcastle, SD, USA), as described in a previous report [27]. Freshly prepared emulsions were dispersed on a parallel plate with a dropper, and low-density silicone oil was used to prevent evaporation. Diameter of the parallel-plate geometry probe was 40 mm, and the plate gap was 0.5 mm. All analyses were performed in the linear viscoelastic region with a strain of 1%. Apparent viscosity was measured at shear rates from 0.1 to 1000 s−1. G′ and G′′ were recorded with a frequency sweep ranging from 0.1 to 10 Hz, and the frequency dependence curves of G' and G'' were collected for further research. The retention time was fixed at 60 s and balanced for 3 min prior to each test. All the tests were performed at room temperature (25 °C).

2.7.2. Surface tension

Surface tension of the different emulsion samples was tested using an OCA20 surface tester (DataPhysics Instruments Co., Ltd., Germany). A high-precision syringe was used to place an emulsion droplet with a volume of 3.0 μL, and at the same time, an image of the droplet was recorded by a digital camera immediately. The droplet profile was solved numerically and fitted to the Laplace-Young equation to determine interfacial tension.

2.7.3. Microstructure

Droplet changes in PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions under ultrasound, and both the occurrence state and adsorption of PPI-HMP under different conditions, were observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (FV 3000, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan), as reported previously [28]. Proteins, oil, and pectin in a 1 mL emulsion were separately stained with 25 μL of 1.0 mg/mL fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), 20 μL of 1.0 mg/mL Nile red, and 20 μL of calcofluor white, respectively, and incubated in the dark for 30 min. The excitation wavelengths of FITC, Nile red, and calcofluor white were 470, 560, and 360 nm, and the emission wavelengths were 525, 630, and 460 nm, respectively.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicates, and the results are expressed as the average value ± standard deviation. Image plotting was performed using Origin 2021 (OriginLab Co., Ltd., Northampton, MA, USA), and SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analysis of the samples. Significant differences between the means (P < 0.05) were tested using Duncan's multiple range test.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The occurrence state of PPI-HMP

3.1.1. Particle size distribution of PPI-HMP mixture

Molecular interactions in the PPI-HMP mixture systems were explored by intensity-weighted particle size distribution. The particle size-light intensity distributions of PPI, HMP, and PPI-HMP mixtures, at different pH, are shown in Fig. 1. PPI exhibited a bimodal distribution; the minor peak at 400 nm was consistent with the diameter of natural PPI (470 nm) [29]. The main peak appeared around 2,000–11,000 nm, and was contributed by the acid precipitation process at pH 4.5 during the preparation of PPI, which produced large-sized aggregates owing to the zero net charge of PPI [30]. HMP had a maximum peak at 800 nm and a smaller peak at 12,000 nm, corresponding to monomer molecules and aggregates, respectively. Previous studies showed that the tendency of HMP to self-assemble in solution resulted in the appearance of two peaks with large differences in diameter [15].

Fig. 1.

Particle diameter of PPI, HMP and PPI-HMP mixtures at different pH.

The PPI-HMP particle size distribution was significantly different at each pH. In an alkaline environment (pH > 7), both PPI and HMP carried a large amount of negative charge. In the negatively charged environment, far from the isoelectric point (pH 4.5), the structure of PPI stretched and the surface charge increased, thus causing PPI and HMP to completely dissolve in the system, independent of each other. This co-solubilisation phenomenon was particularly pronounced at pH 9.0, wherein, the PPI-HMP mixture had a wider particle size distribution of 50–2,000 nm, mainly concentrating around 700 nm. Compared to that of PPI and HMP, the particle size distribution of PPI-HMP mixture at pH 9.0 shifted to a smaller diameter. This was attributed to the electrostatic repulsion from the side chain in alkaline environment, which triggered the dissociation and stretching of protein [31]. At pH 8.0, the decrease in negative charge caused a decrease in co-solubility, and consequently, the diameter distribution had a slight right shift.

Under neutral condition (pH 7.0), average diameter distribution of the PPI-HMP mixture increased compared to that of alkaline samples, with the main peak appearing at 1,700 nm and minor peaks emerging at 150 nm and 12,000 nm, respectively. As reported by Vinayahan et al. [15], the phenomenon, similar to the superposition of raw material peaks, implied the disappearance of interaction between PPI and HMP. The main reason for this peculiar change was that the dissociation constant of the acidic group of pectin was affected, resulting in the destruction and disappearance of the interaction between PPI and HMP [32].

Under acidic conditions, the number of peaks of all samples gradually decreased. Disappearance of the peak at 10,000 nm and the normalised trend of peaks at pH 6.0 suggested that PPI and HMP had begun to interact. At pH 5.0, the average diameter of PPI-HMP mixture showed a unimodal distribution and shift left, to 500–1,100 nm. When the pH was slightly higher than the pI (4.5), as reported by Vinayahan et al. [15], owing to the inhomogeneous charge distribution on the protein surface, PPI could form complexes with HMP through weak electrostatic attractions, and the mixture presented a single peak distribution with small size. Therefore, at pH 5.0, PPI-HMP soluble complex was considered to form in large scale. However, when the pH was low (pH 4.0), PPI-HMP existed in the form of an insoluble complex owing to the low solubility of PPI, and this caused a right shift in the particle size distribution of PPI-HMP mixture to greater than 3,000 nm.

3.1.2. PPI-HMP mixture microstructure

PPI-HMP existed as a soluble complex at pH 5.0, with no interaction at pH 7.0, and was co-soluble at pH 9.0 (section 3.1.1), and these findings were validated with SEM of samples (Fig. 2). Morphologies of PPI-HMP mixtures were visually different under the three pH conditions mentioned above, and all were quite divergent from the original PPI and HMP morphologies. At pH 5.0, as indicated by the yellow arrows, spherical rough bumps, similar to PPI, appeared on the particle surface, indicating the formation of PPI-HMP soluble complex. The particle surface became smooth and porous, and the rough structure of PPI disappeared at pH 7.0. This was because, under negatively charged environment, the original spherical shape of PPI was destroyed by structure extension, and the PPI no longer formed soluble complexes with HMP via electrostatic attraction.

Fig. 2.

SEM of PPI, HMP and PPI-HMP mixtures at different pH.

Smooth thin-layer structure of the protein and the thread-like structure of pectin were observed at pH 9.0. The conformation of PPI was further stretched, and its solubility was enhanced [33], resulting in PPI and HMP being co-soluble in the system and not interacting with each other. The differences in morphologies verified that the states of occurrence of PPI-HMP at pH 5.0 (soluble complex), 7.0 (no interaction), and 9.0 (co-soluble) were completely dissimilar, and so could be their emulsion properties.

3.2. Model of emulsion droplet breakup under ultrasound

The emulsion droplet breakup process under ultrasound treatment could be completed within a few minutes [34], [35]. To obtain a suitable model that could describe the dynamic process of droplet breakup and clarify the characteristics of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions under ultrasound treatment, all emulsions were homogenised by ultrasound within a tight variation range, and droplet diameters of the PPI-HMP emulsions were collected thereafter (Table 1).

Table 1.

Average droplet diameter (nm) of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions under ultrasound treatment.

| pH | Ultrasound time/s | Ultrasound power density/(W/cm3) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.0 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 7.5 | ||

| pH5.0 | 0 | 3,774 ± 154A | |||

| 30 | 1,600 ± 38Ba | 1,480 ± 60Ba | 1,374 ± 129Ba | 1,293 ± 70Ba | |

| 60 | 1,384 ± 88BCa | 1,041 ± 115Cb | 930 ± 81Cb | 907 ± 50Cb | |

| 120 | 939 ± 116 Da | 708 ± 36 Da | 656 ± 15Ca | 675 ± 87 Da | |

| 240 | 1,104 ± 95CDa | 645 ± 7Db | 662 ± 40Cb | 643 ± 52Db | |

| 360 | 925 ± 121 Da | 622 ± 16Db | 684 ± 50Cab | 516 ± 25Db | |

| pH7.0 | 0 | 2,571 ± 136A | |||

| 30 | 1,260 ± 36BCb | 1,099 ± 76Bc | 1,358 ± 44Bb | 1,612 ± 132Ba | |

| 60 | 1,090 ± 10Ca | 872 ± 73Cb | 1,142 ± 76Ca | 1,162 ± 79Ca | |

| 120 | 1,737 ± 63Ba | 857 ± 22Cb | 789 ± 34BDb | 800 ± 13Db | |

| 240 | 1,084 ± 53Ca | 811 ± 31Cb | 862 ± 30Db | 806 ± 13Db | |

| 360 | 962 ± 78Ca | 821 ± 50Cb | 714 ± 5Ec | 632 ± 29Ec | |

| pH9.0 | 0 | 1,976 ± 287A | |||

| 30 | 1,505 ± 99Ba | 1,185 ± 13Bb | 868 ± 54Bc | 914 ± 16Bd | |

| 60 | 1,045 ± 71Ca | 867 ± 66Cab | 732 ± 65BCb | 808 ± 46BCab | |

| 120 | 987 ± 127CDa | 746 ± 81CDa | 661 ± 80BCa | 685 ± 26CDa | |

| 240 | 750 ± 71CDa | 785 ± 66CDa | 606 ± 3Ca | 620 ± 38DEa | |

| 360 | 691 ± 42 Da | 645 ± 31 Da | 613 ± 52Ca | 519 ± 50Ea | |

Different uppercase and lowercase letters indicate significant (P<0.05) differences in means in the same column or row, respectively.

As shown in Table 1, According to the changes in droplet diameter and effective reduction of the droplet size, the degree of droplet breakup decreased with increasing ultrasound time and power density. The size data from Table 1 was substituted in Eq. (1), for linear fitting, to obtain the slope and intercept of the relevant linear equation (Fig. 3). Regression goodness (R2) of the linear fit for all the systems was greater than 0.97, indicating that there was a certain operational relationship between d and d0 under ultrasound. The relevant parameters a and b (calculated using Eq. (2)) are listed in Table 2. After substituting the parameters listed in Table 2 into Eq. (3), three non-linear surface equations were obtained, and the goodness of fit was R2pH5.0 = 0.78, R2pH5=7.0 = 0.78, and R2pH9.0 = 0.73, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Linear correlation of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions.

Table 2.

Relative parameters of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions.

| pH5.0 | pH7.0 | pH9.0 |

|---|---|---|

| a = 1.24 | a = 1.15 | a = 1.15 |

| b = −1.53 | b = −1.04 | b = −0.91 |

| φ = 0.22 | φ = 0.35 | φ = 0.40 |

| ρ = 0.89 g/cm3 | ρ = 0.91 g/cm3 | ρ = 0.93 g/cm3 |

The relative parameters a and b (calculated using Eq. (2)) are listed in Table 2. Siva et al. [21] mentioned that the value of a is used to distinguish the characteristic value of emulsion systems, and φ reflects the breaking potential of the droplets. The values of a were 1.15, 1.15, and 1.24 at pH 9.0, pH 7.0, and pH 5.0, respectively. According to the analysis, emulsions composed of PPI-HMP mixtures at pH 7.0 and 9.0 belonged to the same fluid type. This could be due to the fact that PPI-HMP formed soluble complexes through regional positive plaques at pH 5.0, whereas at pH 7.0 and 9.0, the electrostatic interaction between PPI and HMP disappeared. The difference in molecular interaction led to different emulsion formation and characteristics with ultrasound treatment, resulting in a variety of emulsion systems. The value of φ at pH 5.0 (0.22) was smaller than that at pH 7.0 (0.35) and pH 9.0 (0.40), which meant the decrease of droplet breakup potential. Intermolecular aggregation is one of the factors affecting droplet diameter growth. As the pH decreased from 9.0 to 5.0, the hydration layer of the PPI was gradually removed, which led to the increase of droplet size of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions with aggregation of PPI. Therefore, the breaking potential of the droplets under an ultrasound field was greater at pH 5.0.

3.3. Rheological properties of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsion

3.3.1. Apparent viscosity

Apparent viscosity is a key indicator of emulsion stability [36]. Fig. 4 presents the apparent viscosity of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions with ultrasonic homogenisation at pH 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0. All samples exhibited shear thinning behaviour when the shear rate increased from 0.1 to 1,000 s−1. In addition to disrupting the entanglement and flocculation between sterically hindered macromolecules, a high shear rate deforms the oil droplets, thereby reducing the apparent viscosity [3]. At pH 5.0, 7.0 and 9.0, the PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions showed the highest viscosity values after ultrasound treatments of 4, 8, and 10 min, respectively. According to Stoke’s law, with increase in apparent viscosity, both floating rate of the droplets and Brownian motion rate of colloidal particles slowed down, effectively suppressing the aggregation and flocculation caused by emulsion droplet collisions [27], [37]. However, after excessive ultrasonic homogenisation (more than 4 min at pH 5.0, and 10 min at pH 7.0), the apparent viscosity decreased, revealing that long-term ultrasound treatment was detrimental to the stabilisation of emulsions. This was consistent with the findings of Yue et al. [23] on the changes in viscosity of emulsions across different ultrasound durations.

Fig. 4.

Apparent viscosity of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions.

3.3.2. Storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′)

G′ and G′′ of different emulsions are shown in Fig. 5. At pH 5.0, both G′ and G′′ of the PPI-HMP coarse emulsion were greater than those of the ultrasound-treated emulsions. For the coarse emulsion, G′ was slightly higher than G′′ within 0.7 Hz. Aggregation and cross-linking of PPI or PPI-HMP complex might occur near the pI, which would provide a certain rigidity to the system and result in this phenomenon. However, owing to the disruption of aggregation, G′ and G′′ intersected with an increase in frequency. Appearance of the intersection point indicated local or global collapse of the internal structure of the system, which eventually led to a phase transition. All emulsions prepared by ultrasound exhibited typical liquid properties (G′′>G′) when pH of the PPI-HMP mixture was 5.0 (Fig. 5). Disappearance of G′ in ultrasound-treated samples could be caused by the reduction in particle size of emulsion components (such as PPI, HMP, and PPI-HMP complex), or the destruction of elastic aggregates [38], [39].

Fig. 5.

Storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′) of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions.

Interestingly, variations in the modulus of emulsions at pH 7.0 and 9.0 were completely different from those at pH 5.0, which confirmed the characteristics of emulsion system in section 3.2. Compared to those of the ultrasound samples, the moduli (both G′ and G′′) of the coarse emulsions were lower at pH 7.0 and 9.0. Moreover, G′′ of the coarse emulsions at pH 7.0 and 9.0 was significantly larger than G′, which suggested that the emulsions underwent viscous deformation. After ultrasound treatment, the G′ and G′′ values of all samples were distinctly improved, and G′ was larger than G′′ when the frequency was within a certain range. Meanwhile, frequency corresponding to the intersection points were positively correlated with the ultrasound time. This could be attributed to formation of the HMP network structure. Some studies reported that ultrasound treatment could affect the side chain structure of pectin [40], and promote the swelling of pectin molecular chains [41]. The above results showed that at pH 7.0 and 9.0, the improvement in emulsion stability after ultrasound treatment could be related to the increase of system viscoelasticity, thus making the emulsion resistant to destabilisation.

3.4. Surface tension of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions

Surface tension is created by the contraction of thin gas–liquid layers under gravity. In the surface layer, distribution of molecules is sparse, and distance between the molecules is larger than that in the liquid; therefore, there would be a gravitational effect between molecules. Some researchers reported that surface tension could be microscopically represented by intermolecular interactions and thermal effects, and macroscopically defined as 'the force acting along the interface' [42]. Thus, fluctuation of surface tension reflects the change of intermolecular interactions in the emulsion system. The surface tension of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions at different pH is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Surface tension of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions.

The surface tension of the coarse emulsions was 53.14, 51.99, and 52.98 mN/m at pH 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0, respectively. Under optimal ultrasound treatment, surface tension of the PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions presented the highest value, with P < 0.05 (56.31, 52.92, and 53.46 mN/m for pH 5.0, pH 7.0, and pH 9.0, respectively). Increase in surface tension indicated enhanced interactions between molecules in the emulsion system. This implied that besides breaking oil droplets, ultrasound could also effectively promote the interaction between macromolecules. According to the above results, this interaction could be the electrostatic attraction of PPI-HMP, or molecular assembly of HMP. Therefore, both viscosity and stability of the emulsions increased.

Surface tension decreased for emulsions subjected to prolonged ultrasound treatment at pH 5.0 and 7.0. This behaviour was associated with the disruption of intermolecular interactions [43]. Compared to that at pH 7.0 and 9.0, surface tension of all the PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions was greater at pH 5.0. This was due to the effective formation of PPI-HMP soluble complex at pH 5.0, which strengthened the molecular interactions. The change in surface tension confirms the driving effect of ultrasound homogenisation on biological macromolecules in emulsions.

3.5. Microstructure of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions

Microstructures of all emulsions are shown in Fig. 7. Compared to that in coarse emulsions, size of the oil droplets (red) of in ultrasound-treated emulsions significantly reduced, and the distribution tended to be more uniform. The collapse of bubbles caused by the cavitation effect of ultrasonic waves could generate strong physical forces that disintegrate large emulsion droplet into smaller ones [44]. The staining areas of PPI (green) and HMP (blue) completely overlapped in all emulsion images at pH 5.0, indicating that PPI-HMP existed as complexes in the emulsion system. After ultrasound treatment, the PPI-HMP complexes were no longer agglomerated but were evenly distributed around the oil droplet. After 4 min of ultrasound treatment, the average diameter of the droplets was the lowest, distribution was the most uniform, and oil droplets were the most evenly surrounded by PPI-HMP soluble complex. An appropriate ultrasound duration is known to be conducive to the large-scale breakup of emulsion droplets and the formation of protein-polysaccharide complexes [45]. However, when the ultrasound duration was over 4 min, it destabilised the emulsion by triggering macromolecular aggregation, resulting in a clear tendency of droplets to grow and aggregate via cross-linking of the PPI-HMP complexes. Similar results were reported by Albano et al. [46]. Therefore, ultrasound treatment was considered to maintain PPI-HMP emulsion stability by promoting the formation and adsorption of PPI-HMP soluble complex at pH 5.0.

Fig. 7.

CLSM images of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions. Oil, PPI and HMP were dyed as red, green, and bule, respectively.

At pH 7.0 and 9.0, the green protein signal was evenly spread throughout the background. This indicated that PPI was dissolved in the dispersed medium, whereas HMP was dispersed in the aqueous phase or aggregated into blocks. The unique network structure of HMP provided a certain elasticity to the emulsions. Under the optimal ultrasound duration (8 min for pH 7.0, and 10 min for pH 9.0), the droplets were uniformly distributed with a small average diameter. Same as the samples at pH 5.0, excessive ultrasound treatment made the droplets larger; this could be ascribed to the fact that the protein structure was disrupted, hence affecting molecular motion and resulting in aggregation of droplets [47].

3.6. Formation mechanism of PPI-HMP stabilised emulsion

Formation mechanisms of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsion under ultrasound treatments are summarised in Fig. 8. At pH 5.0, PPI and HMP formed a soluble complex through electrostatic attraction, and ultrasound promoted the formation of the complex and drove its distribution at the oil–water interface, finally causing the viscoelasticity PPI-HMP interface film to wrap oil droplets. At pH 7.0, the negatively charged environment caused the PPI-HMP complex to dissociate into monomers. As amphiphilic biomacromolecules, proteins are the dominant components of interfacial adsorption. Besides affecting the protein structure and dispersion, ultrasound treatment also contributed to the formation of the HMP network structure at the same time. The HMP network structure trapped oil droplets and limited their displacement, thereby improving emulsion stability. At pH 9.0, the oil–water interface adsorption mode was similar to that at pH 7.0. Further increase in the amount of charge not only enhanced the dissolution of PPI and HMP but also suppressed the self-aggregation phenomenon by strong electrostatic repulsion. Consequently, PPI and HMP existed independently in the system in a co-soluble form, and the assisting effect of ultrasound on HMP network formation was weakened. The droplet diameters in the emulsions did not decrease continuously with the input of ultrasound energy; rather, they had a certain function relationship with the initial droplet size, ultrasound time, and power density: The function parameters were affected by the emulsion formation mechanism. At pH 5.0, the formation of PPI-HMP soluble complex dominated emulsion stability, and a was 1.24; at pH 7.0 and 9.0, the change in the ultrasonic effects changed a to 1.15. The difference in a reflected that the formation and characteristics of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions were different.

Fig. 8.

The formation mechanism of pH-shifted PPI-HMP stabilised emulsions under ultrasound.

4. Conclusions

Diameter distribution and SEM results of PPI-HMP complexes revealed the state of occurrence of PPI-HMP at pH 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0 to be soluble complex, no-interaction, and co-soluble, respectively. According to the droplet breakup model, the characteristic value of emulsion (a) stabilised by PPI-HMP treated at pH 5.0, pH 7.0, and pH 9.0 was 1.24, 1.15 and 1.15, respectively. In addition, breaking potential of emulsion droplets (φ) increased from 0.22 to 0.40. Rheological properties suggested that the emulsions stabilised by PPI-HMP treated at pH 5.0 showed typical liquid characteristics under ultrasound treatment, whereas that exhibited viscoelasticity in the initial range of frequencies at pH 7.0 and 9.0. Apparent viscosity and surface tension of all emulsions reached the highest values after optimal ultrasound time, which would be conducive to improve the emulsion stabilisation. CLSM images confirmed that ultrasound could facilitate the formation and adsorption of PPI-HMP soluble complex at pH 5.0, whereas it worked on promoting the formation of HMP network structure at pH 7.0 and 9.0. This study could provide a reference for constructing emulsions using pH-shifted PPI-HMP under ultrasound treatment, and predicting their droplet diameter therefrom.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20270, 2021); Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (222300420424, 2022); National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD2101403); Young-aged Backbone Teacher Funds of Henan Province of China (2020GGJS083, 2020); Doctoral Scientific Research Start-up Foundation from Henan University of Animal Husbandry and Economy (2022HNUAHEDF010, 2022); Foundation of Henan Educational Committee (23B550007, 2022).

References

- 1.Wang S.N., Yang J.J., Shao G.Q., Qu D.N., Zhao H.K., Zhu L.J., Yang L.N., Li R.R., Li J., Liu H., Zhu D.S. Dilatational rheological and nuclear magnetic resonance characterization of oil-water interface: impact of pH on interaction of soy protein isolated and soy hull polysaccharides. Food Hydrocolloid. 2020;99 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.105366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y.Q., Fan B., Tong L.T., Lu C., Li S.Y., Sun J., Liu L.Y., Wang F.Z. High internal phase emulsions stabilized solely by soy protein isolate. J. Food Eng. 2022;318 doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2021.110905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun C., Fu J.J., Tan Z.F., Zhang G.Y., Xu X.B., Song L. Improved thermal and oxidation stabilities of pickering high internal phase emulsions stabilized using glycated pea protein isolate with glycation extent. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022;162 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2022.113465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun X.Y., Zhang W., Zhang L.F., Tian S.J., Chen F.S. Molecular and emulsifying properties of arachin and conarachin of peanut protein isolate from ultrasound-assisted extraction. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020;132 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao Q.L., Xie T.T., Hong X., Zhou Y.L., Fan L.P., Liu Y.F., Li J.W. Modification of functional properties of perilla protein isolate by high-intensity ultrasonic treatment and the stability of o/w emulsion. Food Chem. 2022;368 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Togias A., Cooper S.F., Acebal M.L., Assa'ad A., Baker J.R., Beck L.A., Block J., Byrd-Bredbenner C., Chan E.S., Eichenfield L.F., Fleischer D.M., Fuchs G.J., Furuta G.T., Greenhawt M.J., Gupta R.S., Habich M., Jones S.M., Keaton K., Muraro A., Plaut M., Rosenwasser L.J., Rotrosen D., Sampson H.A., Schneider L.C., Sicherer S.H., Sidbury R., Spergel J., Stukus D.R., Venter C., Boyce J.A. Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: Report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–sponsored expert panel. World Allergy Organ. J. 2017;10:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s40413-016-0137-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao G.L., Liu Y., Zhao M.M., Ren J.Y., Yang B. Enzymatic hydrolysis and their effects on conformational and functional properties of peanut protein isolate. Food Chem. 2011;127:1438–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.01.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lan Y., Chen B.C., Rao J.J. Pea protein isolate–high methoxyl pectin soluble complexes for improving pea protein functionality: Effect of pH, biopolymer ratio and concentrations. Food Hydrocolloid. 2018;80:245–253. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X.F., Vries R.D. Interfacial stabilization using complexes of plant proteins and polysaccharides. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018;21:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2018.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouyer E., Mekhloufi G., Rosilio V., Grossiord J.L., Agnely F. Proteins, polysaccharides, and their complexes used as stabilizers for emulsions: alternatives to synthetic surfactants in the pharmaceutical field? Int. J. Pharm. 2012;436:359–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasran M., Cui S.W., Goff H.D. Covalent attachment of fenugreek gum to soy whey protein isolate through natural Maillard reaction for improved emulsion stability. Food Hydrocolloid. 2013;30:552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.08.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpentier J., Conforto E., Chaigneau C., Vendeville J.E., Maugard T. Complex coacervation of pea protein isolate and tragacanth gum: comparative study with commercial polysaccharides. Innovative Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2012;69 doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2021.102641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li C., Huang X.J., Peng Q., Shan Y.Y., Xue F. Physicochemical properties of peanut protein isolate-glucomannan conjugates prepared by ultrasonic treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014;21:1722–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang L.J., Hu Y.Q., Yin S.W., Yang X.Q., Lai F.R., Wang S.Q. Fabrication and characterization of antioxidant Pickering emulsions stabilized by zein/chitosan complex particles (ZCP) J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2015;63:2514–2524. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vinayahan T., Williams P.A., Phillips G.O. Electrostatic interaction and complex formation between gum Arabic and bovine serum albumin. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:3367–3374. doi: 10.1021/bm100486p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffin K., Khouryieh H. Influence of electrostatic interactions on the formation and stability of multilayer fish oil-in-water emulsions stabilized by whey protein-xanthan-locust bean complexes. J. Food Eng. 2020;227 doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.109893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felix M., Romero A., Guerrero A. Viscoelastic properties, microstructure and stability of high-oleic O/W emulsions stabilised by crayfish protein concentrate and xanthan gum. Food Hydrocolloid. 2017;64:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.10.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akhtar G., Masoodi F.A. Structuring functional mayonnaise incorporated with Himalayan walnut oil Pickering emulsions by ultrasound assisted emulsification. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022;86 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa A.L.R., Gomes A., Cunha R.L. One-step ultrasound producing O/W emulsions stabilized by chitosan particles. Food Res. Int. 2018;107:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefebvre G., Riou J., Bastiat G., Roger E., Frombach K., Gimel J.C., Saulnier P., Calvignac B. Spontaneous nano-emulsification: Process optimization and modeling for the prediction of the nanoemulsion’s size and polydispersity. Int. J. Pharm. 2017;534:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siva S.P., Kow K.W., Chan C.H., Tang S.Y., Ho Y.K. Prediction of droplet sizes for oil-in-water emulsion systems assisted by ultrasound cavitation: transient scaling law based on dynamic breakup potential. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;55:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu H.T., Zhang J.N., Wang H., Chen Q., Kong B.H. High-intensity ultrasound improves the physical stability of myofibrillar protein emulsion at low ionic strength by destroying and suppressing myosin molecular assembly. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;74 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yue M., Huang M.Y., Zhu Z.S., Huang T.R., Huang M. Effect of ultrasound assisted emulsification in the production of Pickering emulsion formulated with chitosan self-assembled particles: stability, macro, and micro rheological properties. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022;154 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma X.B., Yan T.Y., Hou F.R., Chen W.J., Miao S., Liu D.H. Formation of soy protein isolate (SPI)-citrus pectin (CP) electrostatic complexes under a high-intensity ultrasonic field: Linking the enhanced emulsifying properties to physicochemical and structural properties. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;59 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feng H.Y., Jin H., Gao Y., Yan S.Q., Zhang Y., Zhao Q.S., Xu J. Effects of freeze-thaw cycles on the structure and emulsifying properties of peanut protein isolates. Food Chem. 2020;330 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lv D.Y., Zhang L.F., Chen F.S., Yin L.J., Zhu T.W., Jie Y.L. Wheat bran arabinoxylan and bovine serum albumin conjugates: enzymatic synthesis, characterization, and applications in O/W emulsions. Food Res. Int. 2022;158 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yi J., Gan C., Wen Z., Fan Y.T., Wu X.L. Development of pea protein and high methoxyl pectin colloidal particles stabilized high internal phase pickering emulsions for β-carotene protection and delivery. Food Hydrocolloid. 2021;113 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuyama S., Kazuhiro M., Nakauma M., Funami T., Nambu Y., Matsumiya K., Matsumura Y. Stabilization of whey protein isolate-based emulsions via complexation with xanthan gum under acidic conditions. Food Hydrocolloid. 2021;111 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Q.T., Tu Z.C., Xiao H., Wang H., Huang X.Q., Liu G.X., Liu C.M., Shi Y., Fan L.L., Lin D.R. Influence of ultrasonic treatment on the structure and emulsifying properties of peanut protein isolate. Food Bioprod. Process. 2014;92:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2013.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verfaillie D., Janssen F., Royena G.V., Wouters A.G.B. A systematic study of the impact of the isoelectric precipitation process on the physical properties and protein composition of soy protein isolates. Food Res. Int. 2023;163 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ngui S.P., Nyobe C.E., Bassogog C.B.B., Tang E.N., Minka S.R., Mune Mune M.A. Influence of pH and temperature on the physicochemical and functional properties of Bambara bean protein isolate. Heliyon. 2021;7:e07824. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X.Y., Fang Y.P., Al-Assaf S., Phillips G.O., Yao X.L., Zhang Y.F., Zhao M., Zhang K., Jiang F. Complexation of bovine serum albumin and sugar beet pectin: Structural transitions and phase diagram. LANGMUIR. 2012;28:10164–10176. doi: 10.1021/la302063u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y.J., Zhou X., Zhong J.Z., Tan L.H., Liu C.M. Effect of pH on emulsification performance of a new functional protein from jackfruit seeds. Food Hydrocolloid. 2019;93:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.02.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azarikia F., Abbasi S. Efficacy of whey protein–tragacanth on stabilization of oil-in-water emulsions: comparison of mixed and layer by layer methods. Food Hydrocolloid. 2016;59:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.11.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vélez-Erazo E.M., Consoli L., Hubinger M.D. Spray drying of mono-and double-layer emulsions of PUFA-rich vegetable oil homogenized by ultrasound. Drying Technol. 2020;39:1–14. doi: 10.1080/07373937.2020.1728305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Q., Wang Z.G., Dai C.X., Wang Y.J., Chen W.Y., Ju X.R., Yuan J., He R. Physical stability and microstructure of rapeseed protein isolate/gum Arabic stabilized emulsions at alkaline pH. Food Hydrocolloid. 2019;88:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang Y.R., Ghosh S. Stability and rheology of canola protein isolate-stabilized concentrated oil-in-water emulsions. Food Hydrocolloid. 2021;113 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106399. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren X.F., Hou T., Liang Q.F., Zhang X., Hu D., Xu B.G., Chen X.X., Chalamaiah M., Ma H. Effects of frequency ultrasound on the properties of zein-chitosan complex coacervation for resveratrol encapsulation. Food Chem. 2019;279:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang N., Zhou X.N., Wang W.N., Wang L.Q., Jiang L.Z., Liu T.Y., Yu D.Y. Effect of high intensity ultrasound on the structure and solubility of soy protein isolate-pectin complex. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;80 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan J.K., Wang C., Qiu W.Y., Chen T.T., Yang Y., Wang W.H., Zhang H.N. Ultrasonic treatment at different pH values affects the macromolecular, structural, and rheological characteristics of citrus pectin. Food Chem. 2021;341 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen D.D., Liu M., Chen S., Guo P., Huang X.Y., Lian M.T., Cao Y., Qi C., Sun R.Q. Effects of ultrasonic dispersion in dilute polysaccharide solution. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014;131:40973. doi: 10.1002/app.40973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchand A., Weijs J.H., Snoeijer J.H., Andreotti B. Why is surface tension a force parallel to the interface? Am. J. Phys. 2011;79:999–1008. doi: 10.1119/1.3619866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J., Li B., Geng P., Song A.X., Wu J.Y. Ultrasonic degradation kinetics and rheological profiles of a food polysaccharide (konjac glucomannan) in water. Food Hydrocolloid. 2017;70:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou L., Zhang J., Xing L.J., Zhang W.G. Applications and effects of ultrasound assisted emulsification in the production of food emulsions: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;110:493–512. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y.X., Liang Q.F., Liu X.Q., Raza H., Ma H., Ren X.F. Treatment with ultrasound improves the encapsulation efficiency of resveratrol in zein-gum Arabic complex coacervates. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022;153 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albano K.M., Nicoletti V.R. Ultrasound impact on whey protein concentrate-pectin complexes and in the o/w emulsions with low oil soybean content stabilization. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;41:562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.10.018. https://10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiong Y., Li Q.R., Miao S., Zhang Y., Zheng B.D., Zhang L.T. Effect of ultrasound on physicochemical properties of emulsion stabilized by fish myofibrillar protein and xanthan gum. Food Sci. Emerg. 2019;54:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2019.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]