Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, adolescents relied on social technology for social connection. Although some research suggests small, negative effects for quantity of social technology use on adolescent mental health, the quality of the interaction may be more important. We conducted a daily diary study in a risk-enriched sample of girls under COVID-19 lockdown to investigate associations between daily social technology use, peer closeness, and emotional health. For 10 days, 93 girls (ages 12–17) completed an online daily diary (88% compliance) assessing positive affect, symptoms of anxiety and depression, peer closeness, and daily time texting, video-chatting and using social media. Multilevel fixed effects models with Bayesian estimation were conducted. At the within-person level, more daily time texting or video-chatting with peers was associated with feeling closer to peers that day, which was associated with more positive affect and fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms that day. At the between-person level, more time video-chatting with peers across the 10 days was indirectly associated with higher average positive affect during lockdown and less depression seven-months later, via higher mean closeness with peers. Social media use was not associated with emotional health at the within- or between-person levels. Messaging and video-chatting technologies are important tools for maintaining peer connectedness during social isolation, with beneficial effects on emotional health.

Keywords: COVID-19, Depression, Anxiety, Daily diary, Emotion, Adolescents

In the spring of 2020, teens all over the world were asked to “lock down” in their homes to curtail the spread of the emerging COVID-19 pandemic. This lockdown resulted in dramatic reductions in time spent in person with peers, and increased reliance on digital interaction, leading to concerns about how these changes might influence emotional health (Bhatia, 2020; Loades et al., 2020). This concern was amplified by considerable debate about the effects of social technology use (i.e. social media, texting, video-chatting) on adolescents’ emotional health (e.g., Cauberghe et al., 2021; Charmaraman et al., 2022; Jensen et al., 2019; Massing-Schaffer et al., 2022; Riehm et al., 2019). Specifically, prior research suggests both positive and negative effects of social technology use on teen emotional health, which need to be investigated further with more nuanced approaches (Heffer et al., 2019; Ivie et al., 2020; Odgers & Jensen, 2020; Seabrook et al., 2016; Valkenburg et al., 2022). The sudden, dramatic, and near-universal shift toward reliance on social technology use for peer interaction during the COVID-19 lockdown created a “naturalistic experiment,” and offered a unique opportunity to better understand the mechanisms through which social technology use may be related to day-to-day emotional functioning in teens.

Importantly, symptoms of anxiety and depression have been increasing over the past decade in adolescents (Kalb et al., 2019; Mojtabai et al., 2016), and further increased during the spring of 2020 (Breaux et al., 2021; Lorenzo et al., 2021), especially in girls (Hawes et al., 2021; Magson et al., 2021; Silk et al., 2022). Although many factors, including fears about the virus or related financial strain, likely contributed to this rise in symptoms during the early stage of the pandemic, the most prominent concern reported by adolescents across sociodemographic groups was the dramatic reduction in live social interaction with peers (Cost et al., 2022; Magson et al., 2021; Silk et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2021). Indeed, most adolescent girls felt much lonelier than usual during lockdown (Hinkelman, 2020; Wronski, 2020). Social isolation and loneliness may be particularly detrimental for adolescents, as peer relationships play an important role in adolescent social development, and social connectedness is a key factor in emotional health (Loades et al., 2020; Orben et al., 2020), particularly for girls (Rudolph, 2002). Interestingly, though, not all teens reported more anxiety or depression during lockdown. Although internalizing symptoms rose on average, studies also revealed significant variability in adjustment during the lockdown, with some teens faring as well as or even better than before the pandemic (Cost et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2021), suggesting that some teens were able to find productive ways to adjust to or counteract potential social isolation.

Social technology may have functioned as a lifeline for many adolescents by mitigating the potential effects of social isolation on emotional heath and facilitating opportunities to feel close with peers and maintain social connections in the absence of live social experiences (Magson et al., 2021; Orben et al., 2020). Social technologies are digital platforms that facilitate communication and connection with others. As one such technology, social media is a digital platform that contains interactive user-generated content and enables users to engage in private and public connections with others (e.g., Instagram, Snapchat, Tik Tok; Nesi et al., 2018). Other social technologies that teens frequently use for digital interaction include text messaging and other messaging apps (e.g., GroupMe, WhatsApp), social gaming apps (e.g., Among Us), and video-chatting apps (e.g., FaceTime; Rideout et al., 2022). Despite design differences in these apps, social technologies are often used interchangeably (e.g., teens use messaging and video-chat features on social media platforms) and serve similar social functions (Rideout & Robb, 2018). They are also widely used, with teens spending about six hours per day online, texting, and using social media prior to the pandemic (Twenge et al., 2019) and higher use among girls than boys (Rideout & Robb, 2018). Most teens relied heavily on social technology to stay connected with peers during the pandemic (Ellis et al., 2020).

As previously noted, social technology has been found to have both positive and negative effects on mental health (Heffer et al., 2019; Ivie et al., 2020; Odgers & Jensen, 2020; Seabrook et al., 2016; Valkenburg et al., 2022). Social technologies may have positive effects on emotional health through enhanced social support and connectedness (Baker & Algorta, 2016; Best et al., 2014; Gilmour et al., 2020; Massing-Schaffer et al., 2022), potentially compensating for lost in-person experiences with peers. Yet, social technology (particularly social media) is also a common source of interpersonal stress (e.g., social comparison, rejection; Clark et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2020; Nesi & Prinstein, 2015; Riehm et al., 2019) and may have negative effects on emotional health (Alonzo et al., 2021; Cauberghe et al., 2021; Riehm et al., 2019; Rutter et al., 2021; Tao & Fisher, 2022), particularly for girls(McAllister et al., 2021; Nishida et al., 2019).

Although some have argued that the rise in social technology use may help account for increasing mental health problems in teens, empirical reports have been conflicting, with more recent data pointing to both positive and negative effects of social technology use on teen emotional health that need to be investigated using more detailed and nuanced approaches (Heffer et al., 2019; Ivie et al., 2020; Odgers & Jensen, 2020; Seabrook et al., 2016; Valkenburg et al., 2022).

Thus, while social technology, especially social media, can have negative impacts on emotional health, it may also promote connectedness, which could be particularly beneficial during a period of decreased in-person social connectedness, such as the lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic. The goal of the present study was to examine in greater detail and nuance the associations between daily social technology use, closeness with peers, and same-day emotional health (e.g., positive affect, depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms) during initial COVID-19 stay-at-home orders in a risk-enriched sample of adolescent girls. We employed a person-centered, longitudinal daily diary design, which is needed to clarify the temporal sequence of associations between social technology use and emotional health (Heffer et al., 2019; Ivie et al., 2020; Valkenburg et al., 2022). Examining social experience at the within-person level facilitates identification of how specific types of social experiences directly impact day-to-day variations in mood and symptomatology above and beyond examinations of a person’s average mood. This approach is essential given that these factors are near-term dynamic processes that change day-to-day within a person. This approach meaningfully extends most prior research on social technology and emotional health, which often relies on correlational designs, adult samples, and retrospective self-report of social media use or total screen time (Odgers & Jensen, 2020).

Given mixed findings from the extant literature and the methodology of current study (i.e., within-person design, social technology as the primary form of communication during the lockdown), our hypotheses are driven by theory linking social isolation and emotional health (Loades et al., 2020; Orben et al., 2020). Specifically, we hypothesized that greater texting, video-chatting, and social media use (e.g., TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook) on a given day would predict lower levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms as well as higher positive affect that same day, which would be accounted for by greater feelings of closeness with peers. We expected similar findings at the between-person level, when averaging across days. Finally, we examined whether these same patterns would be maintained longitudinally (i.e., at a seven-month follow-up assessment). We focused on a risk-enriched sample because understanding the effects of social technology on emotional health may be especially important among youth at high risk for emotional health problems who went into the pandemic with pre-existing risk factors for developing affective disorders (e.g., a shy or fearful temperament).

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 93 girls aged 12–17 (Mage=15.06, SDage=1.19; see Table 1 for additional demographic information) recruited from a larger longitudinal study on the development of internalizing disorders. The larger longitudinal study comprised a sample enriched for anxiety and depression by oversampling for adolescent girls (aged 11–13) with high levels of shy and/or fearful temperament. Specifically, we recruited approximately two-thirds of the sample (63%) with > 1 SD on the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire-Revised Version (EATQ-R; Ellis & Rothbart, 2001) while the remaining girls scored within the normal range on this temperament scale and were considered low risk. Girls were excluded from the larger study if they met criteria for current or past anxiety (except specific phobia), depressive, psychotic, or autism spectrum disorder based on their report on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS; Kaufman et al., 1997), which was administered at the beginning of the study.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Variables | M (SD) or Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic Variables | |

| Age | 15.06 (1.19) |

| Race | |

|

White, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic |

64 (68.8%) 3 (3.2%) |

|

Black, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic |

16 (17.2%) 1 (1.1%) |

|

Asian, non-Hispanic Asian, Hispanic |

2 (2.2%) 0 (0.0%) |

|

Biracial, non-Hispanic Biracial, Hispanic |

8 (8.6%) 3 (3.2%) |

|

Other, non-Hispanic Other, Hispanic |

3 (3.2%) 0 (0.0%) |

| Approximate Family Total Income | $107,859.15 ($60,554.41) |

| Current SCARED | 18.20 (12.66) |

| Pre-Pandemic Average SCARED | 14.44 (9.14) |

| Current MFQ | 12.53 (9.05) |

| Pre-Pandemic Average MFQ | 9.20 (6.73) |

| COVID-19 Health and Financial Impacts | |

| Know Anyone Who Tested Positive | 21 (22.6%) |

| Self-Quarantined Due to Exposure | 6 (6.5%) |

| Parental Job or Income Loss | 7 (7.5%) |

| Halted Activities Since the Pandemic | |

| In-Person Contact with Family Inside the Home | 6 (6.5%) |

| In-Person Contact with Family Who Live Outside the Home | 63 (67.7%) |

| In-Person Contact with Friends Indoors | 73 (78.5%) |

| In-Person Contact with Friends Outdoors | 63 (67.7%) |

| Family Travel | 87 (93.5%) |

| Family Activities in Outdoor Spaces (e.g., Beaches, Parks) | 57 (61.3%) |

| Family Activities in Public Spaces (e.g., Museums, Theaters) | 82 (88.2%) |

| Going to Restaurants or Stores | 53 (57.0% |

| Indoor Exercise and/or Recreational Sports | 51 (54.8%) |

| In-Person Events in the Community | 78 (83.9%) |

| In-Person Religious Services | 68 (73.1%) |

Note. SCARED = Screen for Childhood Anxiety Related Disorders; MFQ = Mood and Feelings Questionnaire

All participants in the larger study who consented to be contacted about future studies (N = 113) were invited to participate in a COVID-19 follow-up assessment in April/May 2020, which ranged from 16 to 52 months (median = 32 months) from the baseline assessment and was approximately one month after the first COVID-19 case was identified in the local area. During this time, the families in our study were under governor-issued stay-at-home orders and could not leave their homes except for essential life-sustaining purposes. Participants were also to practice “social distancing” measures limiting social interactions outside of the household and all in-person schooling was closed in the local and surrounding counties, with instructional activities either suspended or continuing in an online-only format. Participants who had moved outside of the study’s metropolitan region (n = 2) were required to be under similar stay-at-home orders to be included. Interested participants (N = 93) provided online consent/assent in accordance with the University of Pittsburgh’s Human Research Protection Office. Girls subsequently completed a daily diary survey for 10 consecutive days. An online link to the survey was texted and emailed to participants at 7 PM each evening. Participants completed an average of 88% of daily diaries.

Finally, girls completed an additional follow-up COVID-19 assessment in November/December 2020, seven months after the lockdown period, during which they self-reported on depressive and anxiety symptoms. This assessment schedule was designed to assess girls’ emotional health upon settling into the school year and (new) normal routine. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ; Angold et al., 1995) that contains 33 items assessing depressive symptoms over the past two weeks on a three-point Likert scale (0 = not true, 1 = sometimes, 2 = true). MFQ items were summed to create a total score, where a higher score reflects more greater symptoms (range 0 to 66). Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Screen for Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1997) that contained 41 items assessing anxiety symptoms over the past week on a three-point Likert scale (0 = not true/hardly ever true, 1 = somewhat true/sometimes true, 2 = very true/often true). SCARED items were summed to create a total score where a higher score reflects greater symptoms (range 0 to 82). Both the MFQ and SCARED demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current study (αs = 0.95 and 0.94, respectively). All study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board.

Daily Diary Items

Participants rated their mood each day on a 0-100 sliding scale for five positive emotions (happy, joyful, interested, excited, hopeful), which were averaged to create an index of daily positive affect (ωwithin−person = 0.77, ωbetween−person = 0.92). Participants also reported on daily depressive symptoms using six items from the PHQ-9 (Allgaier et al., 2012) assessing anhedonia, sad mood, fatigue, guilt, trouble concentrating, and psychomotor agitation/retardation (ωwithin−person = 0.68, ωbetween−person = 0.90). Anxious symptoms were assessed using seven items adapted from the GAD-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006) which probes worry, nervousness, fear, restlessness, and irritability (ωwithin−person = 0.73, ωbetween−person = 0.95). To capture the nuance of day-to-day fluctuations in symptoms, participants rated the extent to which they experienced each depressive or anxious symptom that day on a 0-100 sliding scale. PHQ-9 and GAD-7 items were each averaged to create total scores for depressive and anxiety symptoms for each daily diary entry, where a higher score reflects more symptomology. Girls were also asked to estimate how much time they spent that day video chatting with friends outside of school, using apps such as Facetime, Zoom, and House Party), texting with friends, and using social media platforms such as TikTok, Snapchat, and Instagram (see Table 2). They were also asked to use a 0 to 100 point scale to rate how close or connected their felt with their peers, using the question, “How close/connected did you feel to your friends/peers today?”

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations between observed variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | |||||||||||||

| 2. Video-chatting | -0.18 | – | ||||||||||||

| 3. Texting | 0.08 | 0.41 + | – | |||||||||||

| 4. Social media | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.59 + | – | ||||||||||

| 5. Close/Connected | 0.01 | 0.27 ** | 0.22 * | 0.22 * | – | |||||||||

| 6. Positive Affect | 0.03 | -0.13 | -0.06 | 0.01 | 0.48 + | – | ||||||||

| 8. GAD7 | -0.11 | -0.07 | -0.14 | -0.05 | − 0.28 ** | -0.16 | – | |||||||

| 9. PHQ9 | -0.07 | -0.11 | − 0.23 * | -0.13 | − 0.37 + | − 0.29 ** | 0.82 + | – | ||||||

| 10. SCARED Baseline | 0.05 | 0.01 | -0.10 | 0.01 | -0.20 | -0.02 | 0.43 + | 0.38 + | – | |||||

| 11. MFQ Baseline | 0.12 | 0.08 | -0.03 | -0.05 | − 0.35 + | -0.14 | 0.46 + | 0.53 + | 0.68 + | – | ||||

| 12. SCARED Daily Diary | 0.02 | -0.08 | -0.07 | -0.07 | − 0.22 * | -0.07 | 0.50 + | 0.39 + | 0.85 + | 0.57 + | – | |||

| 13. MFQ Daily Diary | 0.05 | -0.13 | -0.09 | -0.03 | − 0.37 + | − 0.24 * | 0.67 + | 0.70 + | 0.57 + | 0.69 + | 0.68 + | – | ||

| 14. SCARED 7 m Follow-up | -0.01 | -0.10 | -0.13 | -0.04 | − 0.25 * | -0.04 | 0.46 + | 0.38 + | 0.82 + | 0.60 + | 0.82 + | 0.59 + | – | |

| 15. MFQ 7 m Follow-up | 0.04 | -0.17 | -0.18 | -0.20 | − 0.50 + | − 0.27 * | 0.56 + | 0.50 + | 0.48 + | 0.67 + | 0.52 + | 0.58 + | 0.56 + | – |

| Mean | 15.06 | 1.85 | 3.37 | 3.80 | 52.40 | 43.35 | 11.23 | 9.82 | 18.20 | 12.53 | 15.59 | 10.56 | 17.66 | 12.21 |

| SD | 1.21 | 0.83 | 1.33 | 1.59 | 20.31 | 19.55 | 12.16 | 9.79 | 12.66 | 9.05 | 12.16 | 8.71 | 12.98 | 11.78 |

Note.* = < 0.05, ** = < 0.01, + = < 0.001. GAD7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006). PHQ9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Allgaier et al., 2012). SCARED = Screen for Childhood Anxiety and Related Disorders (Birmaher et al., 1997). MFQ = Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (Angold et al., 1995)

Analytic Plan

To examine within- and between-person effects of day-to-day social technology use on emotional health during the pandemic lockdown and in subsequent months, we conducted multilevel fixed effects models using Bayesian estimation with default (i.e., noninformative) priors in Mplus v8.7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) with three dependent variables (daily positive affect, anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms) estimated simultaneously. Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) estimation is robust for use with nonnormal data and small sample sizes (Biesanz et al., 2010; Ozechowski, 2014; Price, 2012) and provides more stable parameter estimates than maximum-likelihood methods (Ozechowski, 2014). Exact p-values for two-tailed significance testing are not provided in Bayesian MCMC modeling. Rather, estimates of credibility intervals (CI) for each parameter are used to determine statistical significance. A parameter is statistically significant for α = 0.05 when the 95% CI does not include 0. Median values from observed data were used to estimate variable priors in Mplus. The default convergence criterion in Mplus, in which potential scale reduction factor (PSR) values close to 1 indicate convergence, was used to determine model convergence. The model was set to complete 10,000 iterations, and the final PSR value was 1.001, indicating satisfactory convergence.

Models were automatically decomposed into within- and between-person variance using latent mean centering. Thus, within-person effects can be interpreted as within-person changes on a daily basis relative to one’s own average levels, and between-person effects are interpreted as associations averaged across time relative to the sample means. At the within-person level, our model statistically controlled for trends over days (person-mean centered) and weekday (vs. weekend) cycles on all dependent variables. At the between-person level, our model controlled for the influence of between-person differences in Pre-Diary Anxiety and Depression symptoms (grand-mean centered) on all dependent variables. Participant age and race were also initially included in the model at the between-person level; however, because these variables were not significant predictors in the models, their inclusion led to poorer model fit, and their inclusion did not substantively change the model results, they were not included in the final model. Indirect effects were calculated based on the product of a and b paths with the “model constraint” command.

Results

Descriptive statistics, including mean social technology use, and intercorrelations between observed variables can be found in Table 2. On average, participants reported spending 1.85 h video-chatting, 3.37 h texting, and 3.80 h on social media (e.g., TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook) daily.

Within-Person Effects

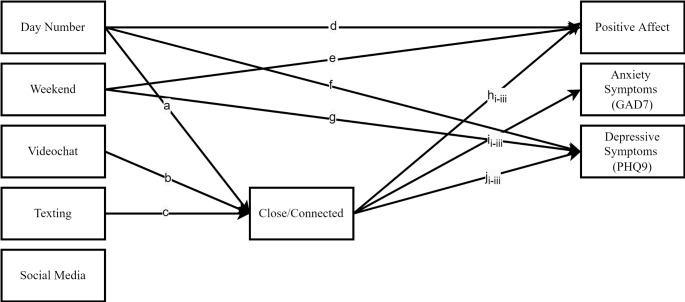

Significant direct and indirect within-person pathways of peer connectedness and social technology use on daily emotional health are presented in Fig. 1. At the within-person level, there were direct effects of time (i.e., day) on positive affect (Est. = − 0.08, SD = 0.02, p < .01), depression (Est. =-0.03, SD = 0.01, p < .05), and closeness (Est. =0.09, SD = 0.03, p < .01), such that as the days progressed, participants reported less positive affect, less depressive symptoms, and more closeness with peers. Similarly, there were direct effects of assessment timing (weekend vs. weekday) on positive affect (Est. = 0.23, SD = 0.11, p < .05) and depressive symptoms (Est. = − 0.14, SD = 0.07, p < .05), such that participants reported more positive affect and less depressive symptoms on weekends compared to weekdays. There were direct effects of closeness on positive affect (Est. =0.17, SD = 0.03, p < .01), anxiety symptoms (Est. =-0.05, SD = 0.02, p < .01), and depressive symptoms (Est. =-0.06, SD = 0.02, p < .01). Specifically, on days when participants reported feeling closer with their peers relative to their usual feelings of closeness to peers, they reported more daily within-person increases in positive affect relative to their own average levels than usual, as well as lower levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms than usual (i.e., relative to their mean levels). Finally, there were direct effects of daily texting (Est. =0.49, SD = 0.09, p < .01) and video-chatting, (Est. =0.53, SD = 0.09, p < .01) on feeling close with peers. On days when participants reported more time texting or video-chatting than their usual levels, they reported greater feelings of closeness with their peers.

Fig. 1.

Significant within-person pathways

a = direct within-person effect of day number on feeling close/connected (Est.=0.09, SD = 0.03, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.14); b = direct within-person effect of video-chatting on feeling close/connected (Est. = 0.53, SD = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.36, 0.70); c = direct within-person effect of texting on feeling close/connected (Est. =0.49, SD = 0.09, 95% CI: 0.31, 0.67); d = direct within-person effect of day number on positive affect (Est. = − 0.08, SD = 0.02, 95% CI: − 0.11, − 0.04); e = direct within-person effect of assessment timing (weekend) on positive affect (Est.= 0.23, SD = 0.11, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.44); f = direct within-person effect of day number on depressive symptoms (Est. = − 0.03, SD = 0.01, 95% CI: − 0.05, − 0.00); g = direct within-person effect of assessment timing (weekend) on depressive symptoms (Est. =-0.14, SD = 0.07, 95% CI: − 0.28, − 0.01); hi = direct within-person effect of feeling close/connected on positive affect (Est. =0.17, SD = 0.03, 95% CI: 0.13, 0.23); hii = indirect within-person effect of video-chatting on positive affect via closeness/connectedness (Est. =0.09, SD = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.06, 0.14); hiii = indirect within-person effect of texting on positive affect via closeness/connectedness (Est. =0.09, SD = 0.02, 95% CI: 0.05, 0.13); ii = direct within-person effect of feeling close/connected on anxiety symptoms (Est. = − 0.05, SD = 0.02, 95% CI: − 0.08, − 0.02); iii = indirect within-person effect of video-chatting on anxiety symptoms via closeness/connectedness (Est. = − 0.03, SD = 0.01, 95% CI: − 0.05, − 0.01); iiii = indirect within-person effect of texting on anxiety symptoms via closeness/connectedness (Est. = − 0.02, SD = 0.01, 95% CI: − 0.05, − 0.01); ji = direct within-person effect of feeling close/connected on depressive symptoms (Est. = − 0.06, SD = 0.02, 95% CI: − 0.09, − 0.02); jii = indirect within-person effect of video-chatting on depressive symptoms via closeness/connectedness (Est. =0.03, SD = 0.01, 95% CI: − 0.05, − 0.01); jiii = indirect within-person effect of texting on depressive symptoms via closeness/connectedness (Est. = − 0.03, SD = 0.01, 95% CI: − 0.05, − 0.01).

In addition to these direct effects, several significant indirect pathways emerged at the within-person level. First, a higher level of texting with peers relative to one’s own mean was indirectly related to relatively high positive affect that same day, (Est. =0.09, SD = 0.02, p < .01), relatively low levels of anxiety (Est. = − 0.02, SD = 0.01, p < .01), and relatively low depressive symptoms, (Est. = − 0.03, SD = 0.01, p < .01) through an increased feeling of closeness with peers on the same day. The same pattern of results emerged for video-chatting. More time spent video-chatting with peers relative to one’s own mean was indirectly associated with relatively high positive affect that same day, (Est. =0.09, SD = 0.02, p < .01), relatively low levels of anxiety, (Est. = − 0.03, SD = 0.01, p < .01), and relatively low depressive symptoms, (Est. =0.03, SD = 0.01, p < .01) via increased feelings of closeness with peers that day. Daily social media use was not associated with any of the outcomes.

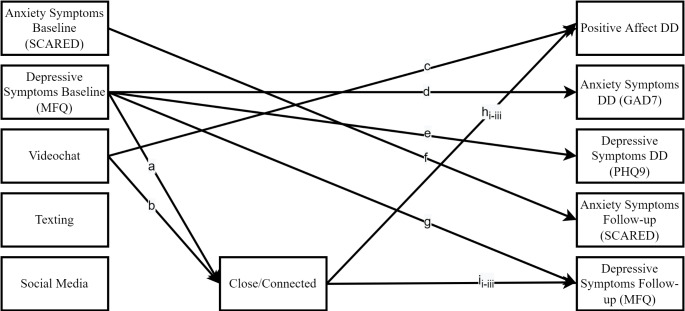

Between-Person Effects

Significant direct and indirect between-person pathways of peer connectedness and social technology use on daily emotional health are presented in Fig. 2. At the between-person level, there was a direct effect of feeling close with peers on participants’ average level of positive affect during the lockdown period, (Est. =0.67, SD = 0.13, p < .01), as well as their report of depressive symptoms seven months later (Est. = − 0.16, SD = 0.07, p < .05). To this end, participants who reported feeling closer with their peers, on average, reported more positive affect, on average, during lockdown and fewer symptoms of depression at a seven-month follow-up assessment. There was also a direct effect of average level of video-chatting on overall levels of positive affect during the lockdown period, (Est. =-0.77, SD = 0.35, p < .05), with participants who reported more time video-chatting overall reporting more positive affect, on average. Finally, there were direct effects of baseline depressive symptoms (Est. = − 0.94, SD = 0.29, p < .01), and overall time spent video-chatting, (Est. =0.76, SD = 0.34, p < .05), on closeness with peers. Participants who reported more baseline depressive symptoms reported less closeness with their peers, and participants who reported more time video-chatting reported feeling closer with peers.

Fig. 2.

Significant between-person pathways

a = direct between-person effect of baseline depressive symptoms on feeling close/connected (Est. = − 0.94, SD = 0.29, 95% CI: -1.51, − 0.37); b = direct between-person effect of video-chatting on feeling close/connected (Est. =0.76, SD = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.09, 1.43); c = direct between-person effect of average level of video-chatting on average level of positive affect (Est. = − 0.77, SD = 0.35, 95% CI: -1.48, − 0.10); d = direct between-person effect of average baseline depressive symptoms on daily diary anxiety symptoms (Est. = 0.39, SD = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.78); e = direct between-person effect of average baseline depressive symptoms on daily diary depressive symptoms (Est. = 0.48, SD = 0.15, 95% CI: 0.18, 0.79); f = direct between-person effect of average baseline anxiety symptoms on follow-up anxiety symptoms (Est. = 0.81, SD = 0.10, 95% CI: 0.62, 0.99); g = direct between-person effect of baseline depressive symptoms on follow-up depressive symptoms (Est. = 0.68, SD = 0.16, 95% CI: 0.36, 1.00); hi = direct between-person effect of average level of feeling close/connected on average level of positive affect (Est. = 0.67, SD = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.41, 0.93); hii = indirect between-person effect of baseline depression on positive affect via closeness/connectedness (Est. = − 0.61, SD = 0.24, 95% CI: -1.13, − 0.21); hiii = indirect between-person effect of video-chatting on positive affect via closeness/connectedness (Est. =0.49, SD = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.06, 1.06); ii = direct between-person effect of feeling close/connected on follow-up depressive symptoms (Est. = − 0.16, SD = 0.07, 95% CI: − 0.29, − 0.03); iii = indirect between-person effect of baseline depressive symptoms on follow-up depressive symptoms via closeness/connectedness (Est. =0.14, SD = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.02, 0.33); iiii = indirect between-person effect of video-chatting on follow-up depressive symptoms via closeness/connectedness (Est. = − 0.11, SD = 0.08, 95% CI: − 0.30, − 0.003).

Again, several significant indirect effects emerged from the between-person model. First, higher baseline depressive symptoms were associated with less positive affect during lockdown (Est. = − 0.61, SD = 0.24, p < .01) and more depressive symptoms longitudinally (Est. =0.14, SD = 0.08, p < .05), via less closeness with peers. Additionally, more time video-chatting was associated with more positive affect during lockdown (Est. =0.49, SD = 0.26, p < .05), and fewer depressive symptoms longitudinally (Est. = − 0.11, SD = 0.08, p < .05), through more overall closeness with peers. Again, daily social media use was not associated with any of the outcomes.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to help clarify the nature of the relation between social technology and adolescents’ emotional health by examining associations between daily social technology use, peer closeness, and emotional health at both the within- and between-person levels. At the within-person level, more daily time texting or video-chatting with peers was associated with feeling closer to peers that day, which in turn, was associated with more positive affect, less depression, and less anxiety on the same day. At the between-person level, more time video-chatting with peers across the 10 days was indirectly associated with higher average positive affect during lockdown and less depression seven-months later, via higher mean closeness with peers. Daily social media use was not associated with emotional health at the within- or between-person levels.

Results from the current study extend findings from a pre-pandemic study examining same-day and longitudinal mental health effects of adolescents’ digital technology (Jensen et al., 2019) by focusing specifically on social technologies. Jensen and colleagues found that, although adolescents’ technology use was not generally related to same-day or prospective mental health symptoms, adolescents who sent more text messages on average also reported fewer symptoms of depression (Jensen et al., 2019). The current findings replicate and extend this link between texting and depressive symptoms, and suggest that messaging and video-chatting technologies are important tools for maintaining a sense of connectedness with peers during periods of social isolation, with beneficial effects on both positive and negative emotions. Adolescents have commonly cited a lack of in-person interactions with friends as a negative impact of the COVID-19 lockdown (Cost et al., 2022; Magson et al., 2021; Silk et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2021). This change in peer interactions has been linked to lower daily positive affect (Silk et al., 2022), and during the pandemic, adolescent girls reported feeling lonelier than usual (Hinkelman, 2020; Wronski, 2020). Nonetheless, despite concerns accompanying growing use, our findings suggest social technologies, like texting and video-chatting, may offer safe ways to mitigate negative impacts of social isolation, particularly for girls, and may promote positive emotional functioning when in-person interactions are limited. To this end, current findings also align with extant research demonstrating positive effects of social technology on perceived social support and well-being (Baker & Algorta, 2016; Best et al., 2014). Finally, and consistent with mixed findings in the pre-pandemic literature, our findings also suggest that social media use does not have systematic detrimental or beneficial effects on same-day emotions or emotional health longitudinally.

Critically, our findings were specific to social technologies that are inherently interactive (i.e., texting and video-chatting). No meaningful associations between daily social media use and emotional health emerged. Echoing prior research (Beyens et al., 2020; Orben et al., 2020; Valkenburg et al., 2022), the current pattern of results also highlights the importance of evaluating the specific nature of adolescents’ social technology use. Such specificity may be particularly important in research focused on social media as there is substantial heterogeneity in how social media is used, and the type of use may differentially affect emotional health (Beyens et al., 2020; Frison & Eggermont, 2016; Thorisdottir et al., 2019). For example, a large pre-pandemic study found that, overall, active social media use was associated with fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescents, and linked passive use with higher levels of depression and anxiety, particularly among girls (Thorisdottir et al., 2019). Active social media use typically involves engaging with others by creating, liking, or commenting on posts, and messaging with others. Conversely, passive users observe others, scrolling through posts without engaging or interacting with others. Thus, results from Thorisdottir et al. (2019) are consistent with findings from the current study and suggest important differences in how more interactive (versus passive) social technology use relates to emotional health. Although the current study differentiates between inherently interactive social technology (i.e., texting and messaging) and social media use, it does not disentangle active and passive social media use, which may explain why no significant associations involving social media use emerged.

In addition to evaluating the nature of social technology use, our findings underscore the importance of considering the quality of the social technology interaction, and how such interactions affect adolescents’ sense of connectedness with peers. Indeed, social support is important in reducing risk for psychopathology in youth (Lyell et al., 2020), and greater perceived peer support pre-pandemic has been linked with fewer internalizing problems during the pandemic (Bernasco et al., 2021; Lyell et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018). Feeling close or connected with others may increase one’s sense of social support. Conversely, individuals who lack social support or feel disconnected from others report heightened loneliness, which is associated with myriad negative outcomes (for a review, see Wang et al., 2018). Relatedly, and aligning with current findings, adolescent girls who actively use social media perceive increased social support, which, in turn, is linked to decreased depressive symptoms (Frison & Eggermont, 2016). Moreover, and partially supporting our findings, another study found that virtual time with friends (but not social media use) was associated with less loneliness among adolescents, though both virtual time with friends and social media use were linked to increased depression (Ellis et al., 2020). Differences in the findings from Ellis et al. (2020) and the current study may be attributable to methodological differences in the two studies. Specifically, the former involved a between-person design involving a single survey to obtain adolescents’ retrospective reports of their social media use, virtual time with friends, and emotional health over a long period of time, whereas the present study took a within-person in vivo repeated daily assessment approach.

Strengths of the current study include examining the role of social technology in adolescents’ feelings of connectedness to peers, and in turn, their emotional health at a time when adolescents’ in-person experiences with friends were dramatically limited (i.e., during the COVID-19 lockdown), and the use of ecologically-valid methods to examine same-day predictors of fluctuations in emotional health. Nonetheless, it will be important to evaluate whether findings are unique to periods of social isolation and stress or can be translated to the return to normal day-to-day functioning. In the current study, social technology use was only assessed during the lockdown period (and not before or after), which limits our ability to test generalizability. Moreover, the daily diary assessment period during the lockdown period was relatively short (10-day).

At the outset, we also want to note that girls’ social technology use, closeness with peers, and same-day emotional health were all assessed at the same timepoint, which limits our ability to make causal inferences. Statistically, the current study examined indirect effects of social technology use on emotional health through closeness with peers; however, conceptually, it is also possible that girls were more likely to use social technology on days when they feel closer with their peers. At the between-person level, emotional health was assessed seven-months after social technology use and peer closeness; however, at the within-person level, it is also possible that girls were more likely to use social technology and/or feel closer with peers on days when they experienced better emotional health (more positive affect, fewer depressive/anxiety symptoms).

Several additional limitations merit discussion. First, we were unable to assess potential differences in passive versus active social media use on adolescents’ emotional health. Although we assessed multiple types of social technology use (i.e., texting, video-chatting, and social media), we did not collect data on the specific nature of adolescents’ social media use (i.e., active versus passive), which prevents a more nuanced examination of this particular type of social technology. Second, one possible explanation for the current pattern of results is that the use of more interactive social technologies (i.e., texting, video-chatting) may serve as an index of friendships or peer networks. As such, more texting and video-chatting may actually be indicative of stronger friendships or peer networks, that, if maintained during the pandemic lockdown, contributed to better emotional health, through peer closeness. In turn, less texting and video-chatting may be the result of fewer/weaker social connections. Thus, it may be the presence of (or support from) a social network more generally (rather than social technology use) that contributes to social connectedness and emotional health. Supporting this possibility, more passive social technologies, like social media, are not necessarily dependent upon strong friendships and therefore, are less likely to be indices of friendships/peer networks, which could explain the lack of significant effects related to social media use in the current study. Nonetheless, in the current study, we did not assess girls’ friendships, and are therefore unable to test this hypothesis. Thus, although from the current results we glean that interactive social technologies can have beneficial effects on girls’ emotional health through peer closeness, it remains unclear whether these positive effects are dependent upon the presence of positive peer relationships. Third, data were self-reported by girls at the end of each day, and therefore, susceptible to bias. It is possible that girls did not accurately report their daily social technology use. Youth experiencing symptoms of anxiety and/or depression may also be more biased in reporting on social technology use. Future research in this area may be strengthened through the use of objective measures of social technology use (i.e., passive sensing) that account for any bias in self-report.

We also note several limitations related to our sample. First, our study involved a risk-enriched sample of adolescent girls. Thus, it is also unclear if findings would generalize to boys. Second, our sample comprised of few socioeconomically disadvantaged families, and participants did not report much financial stress related to the pandemic; findings, therefore, may not generalize to youth who faced more financial challenges due to unemployment, etc. during the lockdown. All youth in the current study had access to technologies that enabled them to interact with their peers. Finally, two thirds of the participants in our sample identified as White, non-Hispanic. The pandemic has disproportionately impacted youth and families from minoritized communities (Tai et al., 2021). It is possible, therefore, that our results may not generalize to more diverse populations.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that interactive social technologies, like texting and video-chatting, can function as vehicles for social connection with peers during periods of social isolation. These technologies may have same-day emotional health benefits that have the potential to be sustained for months to come. Moreover, while youth may not derive the benefits from social media that they derive from messaging and video-chatting technologies, social media use on average does not appear to be detrimental to adolescents’ emotional health. Thus, interactive social technologies appear to offer safe ways to promote positive emotional functioning when in-person interactions are limited. This type of nuanced investigation evaluating both within- and between-person effects of distinct social technologies on emotional health during the pandemic is needed to clarify a rapidly growing, yet mixed body of literature. Parents may want to consider this information in developing family guidelines for healthy social technology use during and following the pandemic.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing or conflicts of interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures were reviewed and approved by Binghamton University’s Institutional Review Board prior to recruitment and data collection.

Informed Consent and Assent

All participants were fully informed about the process and purpose of the study. Written consent/assent was obtained.

Footnotes

Kiera M. James and Jennifer S. Silk contributed equally to this work.

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under grant R01 MH103241 awarded to J.S. Silk and C.D. Ladouceur. K.M James is supported by a National Research Service Award (F32MH127880) from the National Institute of Mental Health. S.L. Sequeira is supported by a Graduate Research Fellowship Program award (1,747,452) from the National Science Foundation. The authors thank Kayley Morrow, Marcie Walker, Elisa Borrero, and Marcus Min for their help in conducting assessments and data management and the participants of the study for their time and willingness to provide data. The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allgaier AK, Pietsch K, Frühe B, Sigl-Glöckner J, Schulte-Körne G. Screening for depression in adolescents: validity of the patient health questionnaire in pediatric care. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29(10):906–913. doi: 10.1002/da.21971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo R, Hussain J, Stranges S, Anderson KK. Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: a systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2021;56:101414. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1995;5(4):237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, Algorta GP. The relationship between online social networking and depression: a systematic review of quantitative studies. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking. 2016;19(11):638–648. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernasco EL, Nelemans SA, Graaff J, Branje S. Friend support and internalizing symptoms in early adolescence during COVID-19. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2021;31(3):692–702. doi: 10.1111/jora.12662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best P, Manktelow R, Taylor B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: a systematic narrative review. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;41:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beyens I, Pouwels JL, van Driel II, Keijsers L, Valkenburg PM. The effect of social media on well-being differs from adolescent to adolescent. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):10763. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67727-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia R. Editorial: Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2020;33(6):568–570. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesanz JC, Falk CF, Savalei V. Assessing mediational models: testing and interval estimation for indirect effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2010;45(4):661–701. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2010.498292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, Neer SM. The screen for child anxiety related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(4):545–553. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaux R, Dvorsky MR, Marsh NP, Green CD, Cash AR, Shroff DM, Buchen N, Langberg JM, Becker SP. Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: protective role of emotion regulation abilities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2021;62(9):1132–1139. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauberghe V, van Wesenbeeck I, de Jans S, Hudders L, Ponnet K. How adolescents use social media to cope with feelings of loneliness and anxiety during COVID-19 lockdown. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking. 2021;24(4):250–257. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaraman, L., Lynch, A. D., Richer, A. M., & Zhai, E. (2022). Examining early adolescent positive and negative social technology behaviors and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technology, Mind, and Behavior, 3(1). 10.1037/tmb0000062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Clark JL, Algoe SB, Green MC. Social network sites and well-being: the role of social connection. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2018;27(1):32–37. doi: 10.1177/0963721417730833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, Birken CS, Charach A, Monga S, Kelley E, Nicolson R, Maguire JL, Burton CL, Schachar RJ, Arnold PD, Korczak DJ. Mostly worse, occasionally better: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of canadian children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2022;31(4):671–684. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, L., & Rothbart, M. (2001). Revision of the early adolescent temperament questionnaire.

- Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM. Physically isolated but socially connected: psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences Du Comportement. 2020;52(3):177–187. doi: 10.1037/cbs0000215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frison E, Eggermont S. Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review. 2016;34(2):153–171. doi: 10.1177/0894439314567449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour J, Machin T, Brownlow C, Jeffries C. Facebook-based social support and health: a systematic review. Psychology of Popular Media. 2020;9(3):328–346. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes, M. T., Szenczy, A. K., Klein, D. N., Hajcak, G., & Nelson, B. D. (2021). Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine, 1–9. 10.1017/S0033291720005358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heffer, T., Good, M., Daly, O., MacDonell, E., & Willoughby, T. (2019). The longitudinal association between social-media use and depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults: An empirical reply to Twenge et al. (2018). Clinical Psychological Science, 7(3), 462–470. 10.1177/2167702618812727

- Hinkelman, L. (2020). Research brief: Findings from 1,273 u.S. Girls on school technology, relationships & stress since covid-19. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/597249b6d7bdcec54c7fdd10/t/5ef647de701c53068afb3c31/1593198563282/ROX+Research+Brief_Findings+from+1%2C273+US+Girls+on+School%2 C+Technology%2 C+Relationships+%26+Stress+Since+COVID-19.pdf

- Ivie EJ, Pettitt A, Moses LJ, Allen NB. A meta-analysis of the association between adolescent social media use and depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;275:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M, George MJ, Russell MR, Odgers CL. Young adolescents’ digital technology use and mental health symptoms: little evidence of longitudinal or daily linkages. Clinical Psychological Science. 2019;7(6):1416–1433. doi: 10.1177/2167702619859336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan ND. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalb, L. G., Stapp, E. K., Ballard, E. D., Holingue, C., Keefer, A., & Riley, A. (2019). Trends in psychiatric emergency department visits among youth and young adults in the us. Pediatrics, 143(4). 10.1542/peds.2018-2192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee HY, Jamieson JP, Reis HT, Beevers CG, Josephs RA, Mullarkey MC, O’Brien JM, Yeager DS. Getting fewer “likes” than others on social media elicits emotional distress among victimized adolescents. Child Development. 2020;91(6):2141–2159. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, Reynolds S, Shafran R, Brigden A, Linney C, McManus MN, Borwick C, Crawley E. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of covid-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218–1239e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo NE, Zeytinoglu S, Morales S, Listokin J, Almas AN, Degnan KA, Henderson H, Chronis-Tuscano A, Fox NA. Transactional associations between parent and late adolescent internalizing symptoms during the covid-19 pandemic: the moderating role of avoidant coping. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2021;50(3):459–469. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01374-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyell KM, Coyle S, Malecki CK, Santuzzi AM. Parent and peer social support compensation and internalizing problems in adolescence. Journal of School Psychology. 2020;83:25–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2021;50(1):44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massing-Schaffer M, Nesi J, Telzer EH, Lindquist KA, Prinstein MJ. Adolescent peer experiences and prospective suicidal ideation: the protective role of online-only friendships. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2022;51(1):49–60. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2020.1750019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister C, Hisler GC, Blake AB, Twenge JM, Farley E, Hamilton JL. Associations between adolescent depression and self-harm behaviors and screen media use in a nationally representative time-diary study. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2021;49(12):1623–1634. doi: 10.1007/s10802-021-00832-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., & Han, B. (2016). National trends in the prevalence and treatment of depression in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics, 138(6). 10.1542/peds.2016-1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide. Eighth).

- Nesi J, Choukas-Bradley S, Prinstein MJ. Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: part 1—A theoretical framework and application to dyadic peer relationships. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2018;21(3):267–294. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0261-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J, Prinstein MJ. Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43(8):1427–1438. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Tamura H, Sakakibara H. The association of smartphone use and depression in japanese adolescents. Psychiatry Research. 2019;273:523–527. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers CL, Jensen MR. Annual research review: adolescent mental health in the digital age: facts, fears, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2020;61(3):336–348. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orben A, Tomova L, Blakemore SJ. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2020;4(8):634–640. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozechowski TJ. Empirical Bayes MCMC estimation for modeling treatment processes, mechanisms of change, and clinical outcomes in small samples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(5):854–867. doi: 10.1037/a0035889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price LR. Small sample properties of bayesian multivariate autoregressive time series models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2012;19(1):51–64. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2012.634712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout, V., Peebles, A., Mann, S., & Robb, M. B. (2022). The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens, 2021.

- Rideout, V., & Robb, M. (2018). Social media, social life: Teens reveal their experiences. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/2018_cs_socialmediasociallife_fullreport-final-release_2_lowres.pdf.

- Riehm KE, Feder KA, Tormohlen KN, Crum RM, Young AS, Green KM, Pacek LR, la Flair LN, Mojtabai R. Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(12):1266. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30(4):3–13. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter LA, Thompson HM, Howard J, Riley TN, de Jesús-Romero R, Lorenzo-Luaces L. Social media use, physical activity, and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: cross-sectional analysis. JMIR Mental Health. 2021;8(9):e26134. doi: 10.2196/26134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seabrook EM, Kern ML, Rickard NS. Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review. JMIR Mental Health. 2016;3(4):e50. doi: 10.2196/mental.5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Scott LN, Hutchinson EA, Lu C, Sequeira SL, McKone KMP, Do QB, Ladouceur CD. Storm clouds and silver linings: day-to-day life in COVID-19 lockdown and emotional health in adolescent girls. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2022;47(1):37–48. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, Sia IG, Wieland ML. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021;72(4):703–706. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S, Xiang M, Cheung T, Xiang YT. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: the importance of parent-child discussion. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;279:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X, Fisher CB. Exposure to social media racial discrimination and mental health among adolescents of color. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2022;51(1):30–44. doi: 10.1007/s10964-021-01514-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorisdottir IE, Sigurvinsdottir R, Asgeirsdottir BB, Allegrante JP, Sigfusdottir ID. Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking. 2019;22(8):535–542. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Martin GN, Spitzberg BH. Trends in U.S. adolescents’ media use, 1976–2016: the rise of digital media, the decline of TV, and the (near) demise of print. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. 2019;8(4):329–345. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Meier A, Beyens I. Social media use and its impact on adolescent mental health: an umbrella review of the evidence. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2022;44:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Mann F, Lloyd-Evans B, Ma R, Johnson S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. Bmc Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wronski, L. (2020). Common sense media/surveymonkey poll: Coronavirus and teenagers. https://www.surveymonkey.com/curiosity/common-sense-media-coronavirus/